Introduction

According to 2022 cancer statistics, among 36

tumors, the global incidence and mortality rates of liver cancer

rank sixth and fourth, respectively (1). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the

primary histological subtype of primary liver cancer, accounting

for 75-85% of cases (2,3). Due to the lack of individualized

diagnostic markers, HCC is often diagnosed late, which is the main

reason for its poor prognosis (4). The treatment bottlenecks of HCC

mainly include tumor heterogeneity, drug resistance and

optimization of multidisciplinary comprehensive treatment and

biomarker indicators are essential to guide treatment selection

(5). Mitochondria, as essential

organelles in eukaryotic cells, play a central role in energy

metabolism, maintaining redox balance and regulating cell

apoptosis. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations, electron transport

chain defects, oxidative stress, mitochondrial autophagy and other

types of mitochondrial dysfunction are closely related to the

occurrence of tumors (6). In

addition, strategies that target mitochondria serve an important

role in tumor treatment (7).

Kynurenine (Kyn) 3-monooxygenase (KMO) is one of the

three rate-limiting enzymes [indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO),

tryptophan (Try)-2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) and KMO] of the Try-Kyn

pathway and is located on the outer membrane of mitochondria

(8,9). However, studies regarding the role

of KMO in mitochondrial structural and function are insufficient.

Maddison et al (10)

reported that deficiency in the KMO ortholog (cinnabar) in

Drosophila triggered morphological elongation and a

reduction in respiratory capacity in mitochondria. At present, it

is widely known that mitochondrial dynamics are involved in a range

of diseases, including cancer (11). Dysregulated mitochondrial dynamics

can promote cancer development by affecting tumor cell

proliferation, metastasis, drug resistance and the tumor

microenvironment, which highlights the potential of targeting

mitochondrial dynamics as a promising anticancer strategy (11).

KMO has a dual effect on tumor progression in

various types of cancer, influencing tumor occurrence, development

and immune escape. KMO is highly expressed in breast cancer and

colon cancer and is associated with poor prognosis, whereas its

expression is downregulated in clear cell and chromophobe cell

renal cell carcinoma, as well as in endometrial carcinoma and

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (12-16). These studies suggest the

complexity of the function of KMO in tumors and the research on KMO

in tumor progression is in its infancy (17). As research on Try metabolism in

tumors advances, targeting key enzymes such as IDO1 and TDO to

disrupt immunosuppressive signaling has emerged as a promising

strategy. However, the inconsistent outcomes of IDO1 inhibitors in

advanced trials underscore the necessity for further investigation

into Try metabolism within cancer contexts (18). In HCC, Jin et al (19) reported that KMO expression was

higher in cancer tissues than in adjacent tissues and its

expression in liver cancer cells promoted the malignant progression

of tumor cells. However, Shi et al (20) revealed that KMO and the Kyn

derivative 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA), also the downstream

product of KMO, may inhibit tumor formation by inducing cell

apoptosis via activating the transcription factor Yin Yang 1 (YY1).

Notably, there is a lack of research on whether KMO located on the

mitochondria promotes the progression of HCC by affecting

mitochondrial homeostasis and whether the effect of KMO-induced

mitochondrial disorder is related to Try metabolism.

The present study systematically investigated the

role of KMO-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in the malignant

progression of HCC using public data, clinical samples and HCC cell

lines. The differential expression of genes related to

mitochondria, including KMO, were initially screened across

multiple public HCC datasets. Subsequently, the expression of KMO

was validated in clinical samples of HCC. Furthermore, by

interfering with KMO expression in HCC cells, changes in

mitochondrial mass and function were observed. The current study

also explored the impact of KMO-mediated downstream

3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) on mitochondrial mass and

function, aiming to clarify the potential mechanisms underlying

KMO-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in HCC and to provide new

strategies for HCC treatment.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

A total of 31 pairs of tissue specimens, including

tumor and adjacent tissues (distance from tumor edge >1 cm),

from 31 patients with pathologically confirmed HCC were collected

from the Department of Oncology and Vascular Intervention, First

Hospital of Shanxi Medical University between January 2021 and

December 2022. The patients (29 men and 2 women) ranged in age from

50-78 years. The clinicopathological features of these patients

with HCC is shown in Table SI.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First

Hospital of Shanxi Medical University (approval number:

2021SLL086). All patients provided written informed consent. All

research was conducted in strict accordance with the Helsinki

Declaration and relevant institutional and national

regulations.

Public database

The HCC-related GSE101728, GSE45050, GSE84598 and

GSE121248 datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term=) were used for

screening of shared differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The

Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC)

dataset containing the clinical information and mRNA expression

data of 371 HCC patients and 50 normal controls was downloaded from

the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The somatic mutation

profiles of HCC patients were obtained from the University of

California, Santa Cruz (UCSC Xena Browser, https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/). HCC related

single cell sequencing dataset GSE202642 came from the GEO

database.

DEGs screening

DEGs from the HCC-related GSE101728, GSE45050,

GSE84598 and GSE121248 datasets were screened using the GEO 2R

analysis tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/). The 'limma'

R package (version 3.52.0; https://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/limma/)was used to

normalize the TCGA-LIHC dataset and identify DEGs. Thresholds were

set as P<0.05 and |logFC|>1.

Mitochondrial-related DEGs (MRDEGs)

identification

The list of mitochondrial-related genes was obtained

from MitoCarta3.0 (https://www.broadinstitute.org/mitocarta/mitocarta30-inventory-mammalianmitochondrialproteins-and-pathways),

which includes 1,136 human mitochondrial-related genes.

Mitochondrial-related genes were intersected with the DEGs from the

four HCC-related GEO datasets to obtain MRDEGs.

Analysis of single cell sequencing

data

The GSE202642 dataset comprising seven HCC samples

and 4 adjacent non-tumor samples was analyzed, it contained a total

of 115,732 cells and 36,601 genes. The 'Seurat' R package (version

4.3.0; https://github.com/satijalab/seurat) was used to

process single cell sequencing data as follows: i) 'DoubletFinder'

was applied to remove doublets; ii) the 'PercentageFeatureSet'

function calculated mitochondria and red blood cells content per

cell. Quality control was performed using the criteria: i) Detected

genes per cell >500; ii) detected genes per cell <6,000; iii)

mitochondrial genes <20; iv) red blood cells <1.

'NormalizeData' and 'ScaleData' functions were then used to

normalize and scale the data. 'RunPCA' function performed linear

dimensionality reduction with dim=20. 'FindClusters' function

clustered cells with resolution=0.9. 'RunTSNE' function performed

tSNE dimensionality reduction. 'FindAllMarkers' function identified

DEGs in each cell cluster. The 'SingleR' R package (version 2.0.0;

https://github.com/SingleR-inc/SingleR) was used to

identify and annotate cell types. KMO expression levels in normal

and HCC samples were compared across different cell types.

Survival analysis

Overall Survival analysis of genes in HCC patients

was performed using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter online tool

(http://kmplot.com/analysis/).

Weighted gene co-expression network

analysis (WGCNA)

WGCNA was constructed using the DEGs matrix of 340

HCC samples via the 'WGCNA' R package (version 1.71; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=WGCNA). Sample

clustering was performed using the 'hcluster' function to identify

and remove outliers. The optimal soft threshold power β for network

construction was determined using the 'pickSoftThreshold' function.

The adjacency degree matrix was transformed into a topological

overlap matrix (TOM) using 'TOMsimilarity'. Gene expression

similarity was then calculated and the minimum value of module

genes was set to 30 genes. According to the similarity, genes were

divided into different co-expression modules and the module

allocation diagram under gene tree diagram was drawn by

DynamicTreeCut. HCC samples were divided into high and low KMO

expression groups based on the median value of KMO expression.

Correlation analysis was performed between gene co-expression

module and KMO expression status. Pearson's correlation coefficient

and P-value were calculated using the 'cor' function. The

co-expression module with the largest correlation coefficient

P<0.05 was regarded as the key functional module and the genes

within this module were considered KMO-co-expressed hub genes.

Gene enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis were performed using

clusterProfiler (version 4.8.0; https://yulab-smu.top/contribution-knowledge-mining/)

and ggplot2 (version 3.4.1; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggplot2) packages

in R.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) and

correlation analysis

To investigate the relationship between KMO and Try

metabolic pathway genes, Try metabolic pathway genes were

downloaded from the GSEA official website (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) and

analyzed using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/). The PPI network was

visualized using Cytoscape 3.9.0 software (https://cytoscape.org/). The hub genes related to KMO

were captured using CytoHubba of Cytoscape. Correlation heatmaps

and lollipop plots were generated using the online SRplot tool

(http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/SRplot) (21).

Cell culture and KMO expression cell

model

The HCC cell lines MHCC-97H and HCCLM3 (Cell

Resource Center, Institute of Basic Medicine, Chinese Academy of

Medical Sciences) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS

at 37°C with 5% CO2.

KMO-overexpressing lentivirus were constructed by

Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd. using the 3rd lentiviral, LV5

(EF-1a/GFP&Puro). 293T cells (Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of

Sciences) was selected to package the lentivirus using shuttle

plasmid H6370 and packaging plasmid (pGag/Pol, pRev, pVSV-G). The

lentivirus titer of 293T cells after 72 h of infection with the

collected lentivirus stock solution was 9×108 TU/ml.

Multiplicity of infection (MOI) was calculated according to virus

titer and the optimal MOI (1 number/cell) was determined for HCC

cell infection by pre-experiment. For lentiviral overexpression,

cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 5×104 cells/well.

When confluence reached 40-60%, cells were infected with

KMO-overexpressing lentivirus at 1×105 TU/ml. After 24

h, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium. Upon reaching

70-80% confluence, positive cells were screened using 1

µg/ml puromycin concentration (the optimal concentration

determined by puromycin concentration gradient experiment), and 0.5

µg/ml was the maintenance concentration of cultured cells.

For short interfering (si)RNA knockdown, siRNA targeting KMO

(5′-GGA GCC TAT TCA ACT GTC A-3′, 5′-GCG AGC ACA TGT CAA CTC A-3′

and 5′-CCA AGG TAT TCC CAT GAG A-3′) and control siRNA was designed

and synthesized by Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. Cells were seeded in

6-well plates at 3×105 cells per well and transfected at

70-80% confluence using Lipo8000 reagent (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) with the screened siRNA sequence (5′-CCA AGG TAT TCC

CAT GAG A-3′) having the highest knockdown efficiency and a control

siRNA. Overexpression and knockdown efficiencies were assessed

using qPCR and western blotting. KMO stably overexpressing cell

lines and transiently transfected KMO-knockdown cells (harvested at

48 h) were used for subsequent studies.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured in confocal dishes (1,000

cells/dish) for 24 h, then stained with Mito-tracker at 37°C for 25

min in the dark. After washing with ice-cold PBS, cells were fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37°C for 1 h, permeabilized with 0.2%

TritonX-100 for 10 min, after TBST wash buffer (0.05% Tween 20)

washing 3 times (5 min/time), cells were blocked with 2% BSA

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 10 min.

Cells were incubated with 1:100 diluted KMO or NR4A1 primary

antibody (cat no. 10698-1-AP and 12235-1-AP, Proteintech Group,

Inc.) overnight at 4°C, followed by fluorescent secondary antibody

(1:200; cat no. SA00013-2; Proteintech Group, Inc.) at room

temperature for 1 h. After DAPI staining (1:200) at room

temperature for 15 min, cells were imaged at a magnification of

×100.

Immunohistochemical staining

Paraffin-embedded sections (thickness: 5 µm)

were dewaxed, cleaned with PBS and treated with 3%

H2O2 to block endogenous peroxidase at room

temperature for 10 min. Antigen retrieval was performed using

sodium citrate buffer, followed by PBS washing. Sections were

blocked with 5% BSA at 37°C for 30 min, then incubated with 1:100

diluted KMO primary antibody (cat no. 10698-1-AP, Proteintech

Group, Inc.) overnight at 4°C. After washing, sections were

incubated with 1:1,000 diluted HRP-conjugated secondary antibody

(cat no. KIT-5010; Maxim Biomedical, Inc.) for 30 min at room

temperature. DAB staining was performed for 1 min, followed by

hematoxylin counterstaining for 5 min. Sections were dehydrated,

mounted and imaged using a light microscope. The staining intensity

(SI) and percentage of positive cells (PP) were used to calculate

the IHC score (22). SI was

graded as follows: 0 for negative, 1 for low positive, 2 for

moderate positive, and 3 for high positive. PP was classified into

four categories: 0 (0-9% positive cells), 1 (10-25%), 2 (26-50%), 3

(50-75%), and 4 (76-100%). The final immunohistochemical score (IS)

was derived by multiplying SI and PP (IS=SI x PP). Quantitative

analysis was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.53a,

National Institutes of Health).

mRNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissue samples or

cultured cells using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Inc.). RNA was

reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix

Reverse Transcription Kit (Takara Bio, Inc.). The target gene

expression was quantified by two-step qPCR using TB

Green® Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Bio, Inc.) with the

procedure: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, 1 cycle; denatured

at 95°C for 5 sec, annealed at 60°C and extended for 30 sec, 40

cycles. All operations of RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR

were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Relative expression levels were calculated using the

2−ΔΔCq method according to previous study (23). Primer sequences are listed in

Table I. Each sample was analyzed

in triplicate in three independent experiments.

| Table IPrimer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I

Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Primers (5′ to

3′) |

|---|

| KMO | Forward:

CACTGTGTACTGCTGGGAGA |

| Reverse:

ATCGCGTGATCATCTGGGAT |

| β-actin | Forward:

ACTCTTCCAGCCTTCCTTCC |

| Reverse:

TCTCCTTCTGCATCCTGTCG |

| KYNU | Forward:

TGCTGAGTTCATGGCCAAAC |

| Reverse:

AGTGATCCTGTTCAGTGGGG |

| ND1 | Forward:

CCCTAAAACCCGCCACATCT |

| Reverse:

GAGCGATGGTGAGAGCTAAGGT |

| HGB | Forward:

GTGCACCTGACTCCTGAGGAGA |

| Reverse:

CCTTGATACCAACCTGCCCAG |

| MT-ATP6 | Forward:

ACAGTGATTATAGGCTTTCGCTCTAAG |

| Reverse:

ATTGGTTGAATGAGTAGGCTGATGG |

| MT-CO1 | Forward:

GCAGGAACAGGTTGAACAGTCTAC |

| Reverse:

TAGGTGTAAGGAGAAGATGGTTAGGTC |

| SOX4 | Forward:

GCAAGATCATGGAGCAGTCG |

| Reverse:

CCGGACTTCACCTTCTTCCT |

| HMGA1 | Forward:

GTAGGGAGTCAGAAGGAGCC |

| Reverse:

CCTCCTCTTCCTCCTTCTCC |

| NR4A1 | Forward:

AGAAGATCCCTGGCTTTGCT |

| Reverse:

CAGGGACATCGACAAGCAAG |

| FOXO1 | Forward:

CCGAGCTGCCAAGAAGAAAG |

| Reverse:

ATGCACATCCCCTTCTCCAA |

Protein extraction and western

blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology), incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at

12,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and

protein concentration was measured using a BCA kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) at 562 nm.

Equal amounts of protein (≥20 µg) were

separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to the PVDF

membrane at 100 V for 1 h. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat

milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with

1:500 diluted KMO (cat no. 10698-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or

1:10,000 diluted β-Actin (cat no. 66009-1-Ig; Proteintech Group,

Inc.) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing, membranes

were incubated with 1:10,000 diluted horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (cat no. SA00001-2;

Proteintech Group, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the

chemiluminescent substrate (1:1 ratio of solutions A and B) was

added to the PVDF membrane for imaging after washing. Relative

protein expression was calculated using ImageJ software (version

1.53a, National Institutes of Health).

CCK-8 assay

Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay

kit (MeilunBio Co., Ltd.). Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at

3,000 cells per well. Upon cells reaching the logarithmic growth

phase, siRNA transfected experiment was performed. For the 3-HAA

group, the medium was replaced with one containing 100 µM

3-HAA (24). CCK-8 reagent was

added at 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post-transfection and incubated at

37°C for 2 h. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a

multifunctional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay instrument.

EdU staining experiment

Cell proliferation was assessed using the EdU assay

kit (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.). Cells were seeded in a 96-well

plate at 3,000 cells per well and treated as described. After 24 h,

cells were transferred to confocal dishes. After 48 h, 200

µl of 50 µM EdU was added and incubated at 37°C for 2

h in the dark. Cells were then treated sequentially with glycine (2

mg/ml, room temperature, 5 min), Triton X-100 (0.5%, room

temperature, 10 min), Apollo (30 min, room temperature, in the

dark) and Hoechst 33342 staining for 30 min (room temperature, in

the dark).

Clonal formation assay

Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at 500 cells per

well. When visible colonies appeared after 10-14 days, cells were

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, then

stained with 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 30 min.

Colonies were defined as cell clusters containing ≥50 cells. Plates

were rinsed, inverted and colonies were photographed and

counted.

Scratch and transwell tests

The HCC cell lines MHCC-97H and HCCLM3 were cultured

for 24 h to 80% confluence, then scratched with a 200 µl

pipette tip. For siKMO groups, cells were transfected with siKMO

RNA or siControl RNA (20 nM) and cultured at 37°C. After 6 h of

transfection, the complete medium was replaced and the culture

medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 1% FBS after 24 h

of transfection. For KMO overexpression groups, the cells with

stable overexpression of KMO and the EV control group were directly

scratched after 24 h of culture and then cultured in 1% FBS medium.

The wound closure was imaged at 0 and 48 h after scratch and ImageJ

software (version 1.53a, National Institutes of Health) was used to

quantify the migration distance. For other cells to be tested by

Transwell, transfection was performed followed by 24 h of culture.

A 24-well plate was prepared with 700 µl of complete medium

per well. 200 µl of serum-starved cell suspension (KMO

knockdown, KMO overexpression, or corresponding control cells) was

added to each well and cultured for 48 h. Non-migrated cells on the

upper layer of the chamber membrane were removed with a cotton swab

and cells on the lower surface were fixed with methanol at room

temperature for 10 min, then stained with crystal violet at room

temperature for 20 min and counted under a light microscope.

Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis

Following the instructions for the Annexin V-FITC

apoptosis detection kit (Bestbio Technology Co., Ltd.), cells were

washed twice with pre-cooled PBS to obtain cell pellets, then

re-suspended in binding buffer. Cells were stained with 5 µl

Annexin V-FITC at 4°C for 15 min, followed by 10 µl

propidium iodide dye for 10 min at 4°C in the dark. Samples were

immediately detected using flow cytometry (FACSCelesta; BD

Biosciences). And the apoptotic rate of HCC cells (the sum of the

percentages of early + late apoptotic cells) was analyzed using

FlowJo 7.6 software (BD Biosciences).

MitoTracker staining

Mitochondrial biogenesis was detected by using

MitoTracker staining method. Cells were seeded in confocal dishes

at 1,000 cells/dish. At 48 h after siKMO transfection or 100

µM 3-HAA treatment, cells were stained with MitoTracker (200

nM) for 25 min at 37°C in the dark. After washing twice with DMEM,

cells were imaged by confocal microscopy at a magnification of

×100. The total mitochondrial fluorescence intensity was quantified

using ImageJ (version 1.53a, National Institutes of Health).

High performance liquid chromatography

(HPLC) combined with mass spectrometry (MS)

Targeted Try metabolism analysis was performed by

Shanghai Zhongke New Life Biotechnology Co. Ltd.

Sample preparation

Cells were harvested, washed three times with PBS

and scraped with 1 ml precooled methanol/acetonitrile/water (2:2:1,

v/v). Samples were collected, labeled, sealed and stored at -80°C

until analysis.

Chromatographic conditions

Samples were analyzed on an Agilent 1290 UHPLC

system (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) with a 4°C autosampler and

column oven at 40°C. Mobile phases: A (20 mM ammonium formate +

0.2% formic acid in water), B (0.2% formic acid in methanol). Flow

rate: 400 µl/min; injection volume: 5 µl. Gradient

elution: 0-2 min, 10% B; 2-9 min, 10 to 100% B; 9-11 min, 100% B;

11-11.5 min, 100 to 10% B; 11.5-14 min, 10% B.

Mass spectrometry conditions

Analysis was performed on a 5500 QTRAP mass

spectrometer (SCIEX) used in positive/ negative ion mode. Source

temp: 450°C; Gas1/Gas2: 45; CUR: 40; ISVF: ±4,500 V. Multiple

reaction monitoring was used for detection.

MtDNA copy number detection

Cells were seeded in a 6-well plate at a density of

approximately 3×105 cells per well. For KMO knockdown

groups, after 24 h of culture, the cells were transfected with

siKMO small interfering RNA or siControl RNA using

Lipo8000® transfection reagent (Beyotime Biotechnology).

For the siKMO + 3-HAA treated groups, upon reaching 70-80%

confluence, the medium was changed to 2 ml culture medium

containing 100 µM 3-HAA or an equivalent volume of DMSO

(control). The cells were then transfected with siKMO small

interfering RNA. At 48 h after transfection, cell DNA was extracted

using a DNA extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to

the manufacturer's protocol. For KMO overexpression groups, DNA was

extracted after 48 h of culture. mtDNA copy number was detected by

qPCR using primers specific for the mitochondrial gene ND1 and HGB

was used as reference gene.

Cellular ATP level measurement

Cells were lysed using ATP detection lysate, then

centrifuged at 12,000 × g, for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was

collected as the test sample. An ATP standard curve was generated

by diluting the ATP standard solution (10 µM) to

concentrations ranging from 0.01-10 µM. The ATP detection

working solution was prepared at a 1:9 ratio of reagent to diluent.

Working solution (100 µl) was added to 96-well black plate

and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Subsequently, 20

µl of sample or standard was added to each well, mixed and

the relative light unit value was measured after 2 sec. ATP

concentration was calculated using the standard curve.

Intercellular reactive oxygen species

(ROS) level detection

Cells were collected in a 5 ml centrifuge tube. The

ROS fluorescent probe (Bestbio Technology Co., Ltd.),

2,7-dichlorofluorescein acetate DCFH-DA, was prepared at a final

concentration of 10 µM (diluted 1:1,000 in serum-free DMEM).

500 µl of the DCFH-DA working solution was added to each

tube and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 min in the dark.

The unbound DCFH-DA probe was removed by washing with serum-free

medium. Cells were re-suspended in DMEM and then analyzed by flow

cytometry (FACSCelesta, BD Biosciences) with excitation at 488 nm

(25). The results were analyzed

using FlowJo 7.6 software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version

4.2.2, http://www.R-project.org/), GraphPad

Prism (version 8.0; Dotmatics) and SPSS (version 25; IBM Corp.).

All experiments were performed three times independently. The data

were presented as the mean ± SD. The unpaired Student's t-test was

employed for comparisons between two groups with normally

distributed continuous variables, while Mann-Whitney U test was

used for non-normally distributed data. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's

post hoc test was used for comparisons among three groups.

Correlations between continuous variables were assessed using

Spearman's rank correlation analysis. Categorical variables were

compared between groups using the χ2 test. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Downregulation of KMO expression is

related to the poor prognosis in HCC

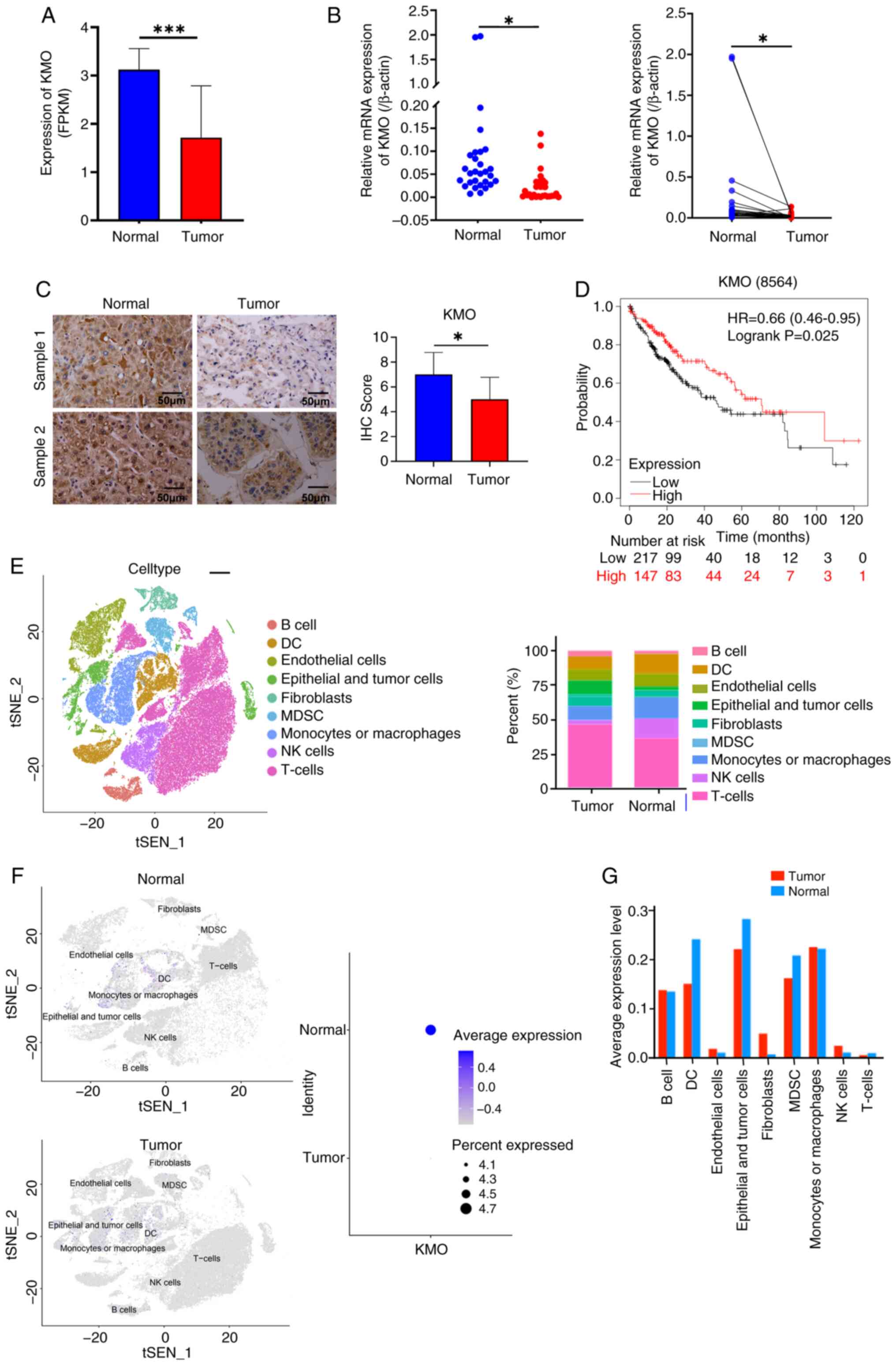

Analysis of GSE101728, GSE45050, GSE84598 and

GSE121248 datasets identified 31 upregulated and 109 downregulated

genes commonly associated with HCC (Fig. S1A-C). Intersection with

mitochondrial-related genes yielded one upregulated and 14

downregulated MRDEGs (Fig. S1D).

Notably, KMO expression was consistently downregulated across all

four datasets (LogFC ranging from -2.094 to -3.453; Fig. S1E). The finding was validated in

TCGA data which demonstrated significantly lower KMO expression in

HCC patients compared to normal individuals (Fig. 1A). qPCR and immunohistochemical

results both showed that compared with matched adjacent normal

tissues, the expression of KMO in HCC tumor tissues decreased

(Fig. 1B and C). The present

study grouped HCC tumor samples from TCGA database according to KMO

median expression value, including 183 samples in KMO high

expression group and 182 samples in KMO low expression group.

Association analysis between KMO and clinicopathological features

of HCC patients in TCGA database are shown in Table II. The results showed that KMO

expression was related to Grade, T stage and tumor stage.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated that the overall

survival time of HCC patients with low KMO expression was

significantly shorter than those with high expression (Fig. 1D).

| Table IIRelationship between KMO expression

level and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with HCC

in TCGA. |

Table II

Relationship between KMO expression

level and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with HCC

in TCGA.

| Variable | KMO Expression

| P-value |

|---|

| Low (n=182) | High (n=183) |

|---|

| Age | | | 0.716 |

| ≤60 | 88 | 85 | |

| >60 | 94 | 98 | |

| Sex | | | 0.765 |

| Male | 124 | 122 | |

| Female | 58 | 61 | |

| Child Pugh

classification grade | | | 0.252 |

| Grade A | 100 | 116 | |

| Grade B and C | 13 | 9 | |

| N/A | 69 | 58 | |

| Grade | | | <0.001 |

| Grade1-2 | 97 | 133 | |

| Grade3-4 | 82 | 48 | |

| N/A | 3 | 2 | |

| M | | | 0.937 |

| M0 | 138 | 125 | |

| M1 | 1 | 2 | |

| MX | 43 | 56 | |

| N | | | 1.000 |

| N0 | 124 | 125 | |

| N1 | 2 | 2 | |

| NX | 56 | 56 | |

| T | | | 0.004 |

| T1-2 | 123 | 148 | |

| T3-4 | 57 | 34 | |

| TX | 2 | 1 | |

| Stage | | | 0.004 |

| Stage I-II | 113 | 142 | |

| Stage III-IV | 54 | 33 | |

| N/A | 15 | 8 | |

| Survival

status | | | 0.559 |

| Alive | 114 | 120 | |

| Dead | 68 | 63 | |

The present study also analyzed the KMO expression

within the HCC tumor microenvironment using single cell sequencing

data. Analysis of 85,168 cells (28,998 genes) identified 10 cell

types. Compared with normal tissues, HCC samples exhibited

increased proportions of T cells, fibroblasts, epithelial and tumor

cells, with decreases in endothelial cells, dendritic cell (DC),

myeloid suppressor cell (MDSC) and natural killer cells (Fig. 1E). The expression of KMO in HCC

was lower in HCC compared with that in normal (Fig. 1F) and was specifically reduced in

DC, epithelial and tumor cells and MDSC (Fig. 1G), suggesting KMO may play

important roles in these cells.

Downregulation of KMO in HCC cells

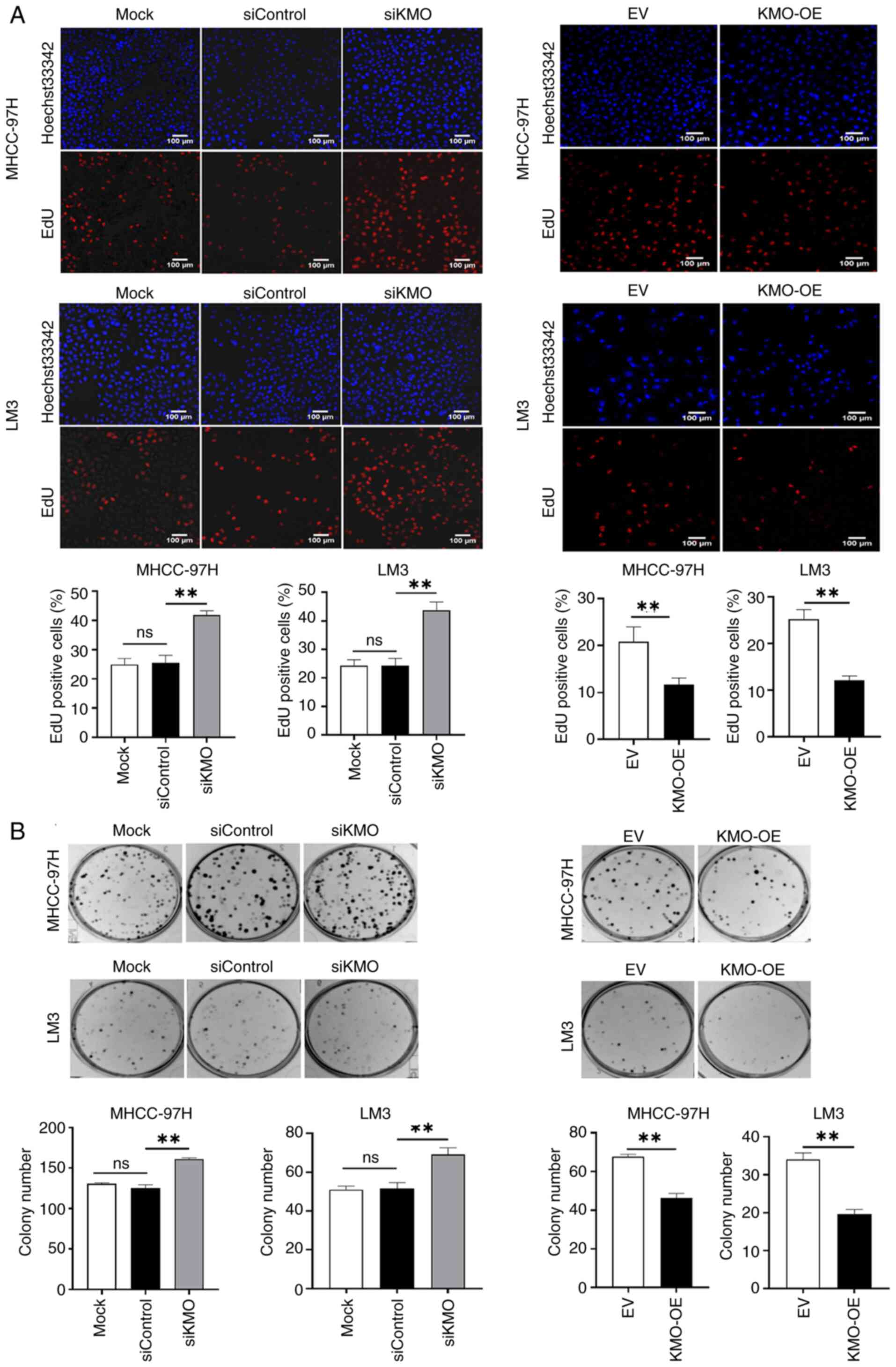

promotes malignant progression of tumor

Using KMO knockdown and overexpression HCC cell

models (Fig. S2), the present

study evaluated the role of KMO in tumor progression. The CCK-8

test, EdU assay and colony formation experiment revealed that,

compared with siControl group, the cell viability, cell

proliferation and cell clone formation in siKMO group were

increased significantly. Conversely, compared with empty vector

(EV) control group, the cell viability, cell proliferation and cell

clone formation in KMO-OE group were significantly decreased

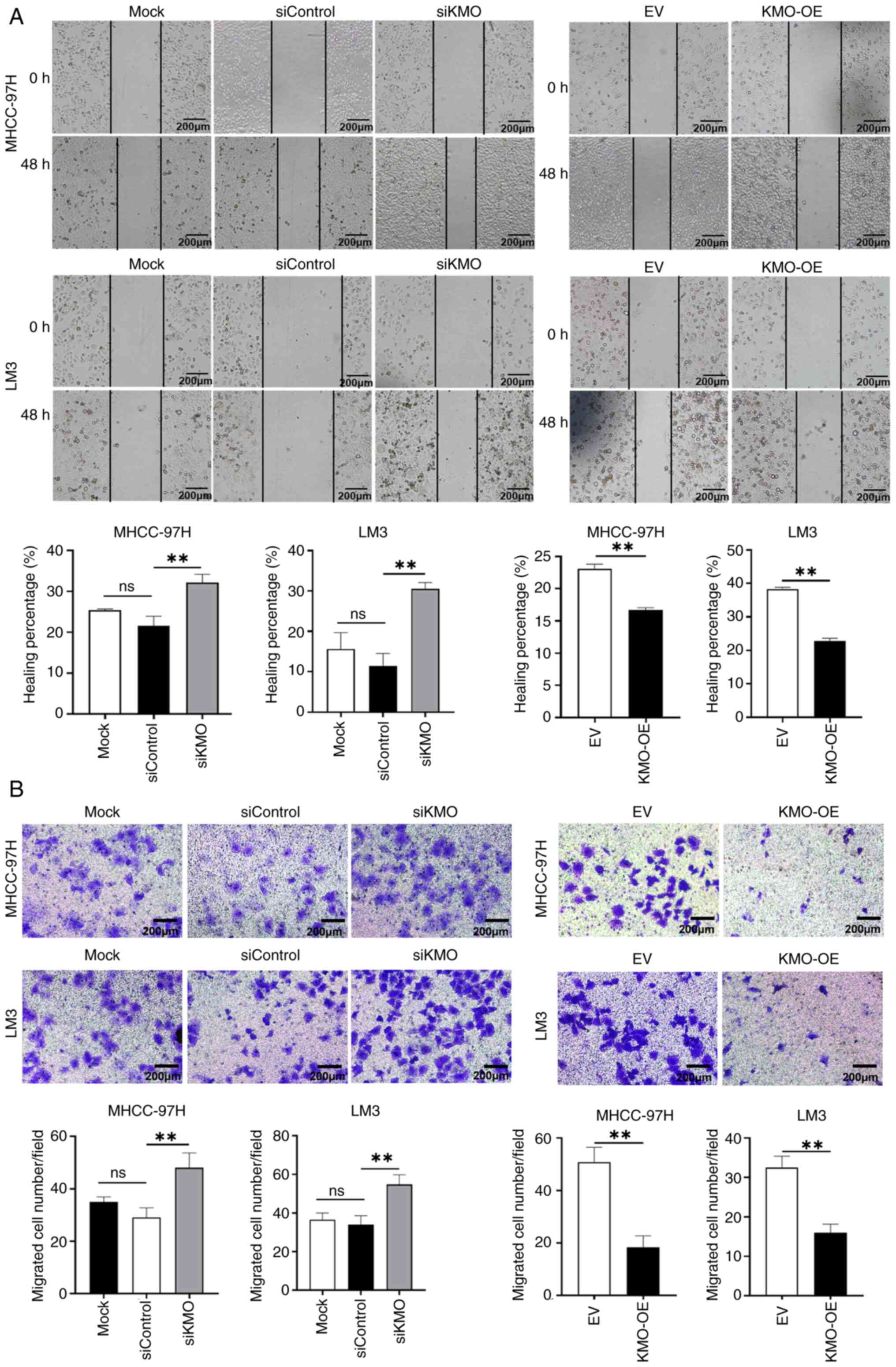

(Fig. 2). The scratch and

Transwell assays demonstrated that cell migration ability in siKMO

group were increased significantly, whereas the opposite effect was

observed in KMO-OE group (Fig.

3). Flow cytometry analysis of cell apoptosis indicated that

the apoptosis rate was increased in KMO-OE group compared with that

in EV control group (Fig.

S3).

Collectively, these results suggested that

downregulation of KMO in HCC cells is associated with enhanced

malignant progression.

KMO may localize to mitochondria and is

associated with Try-kyn metabolism

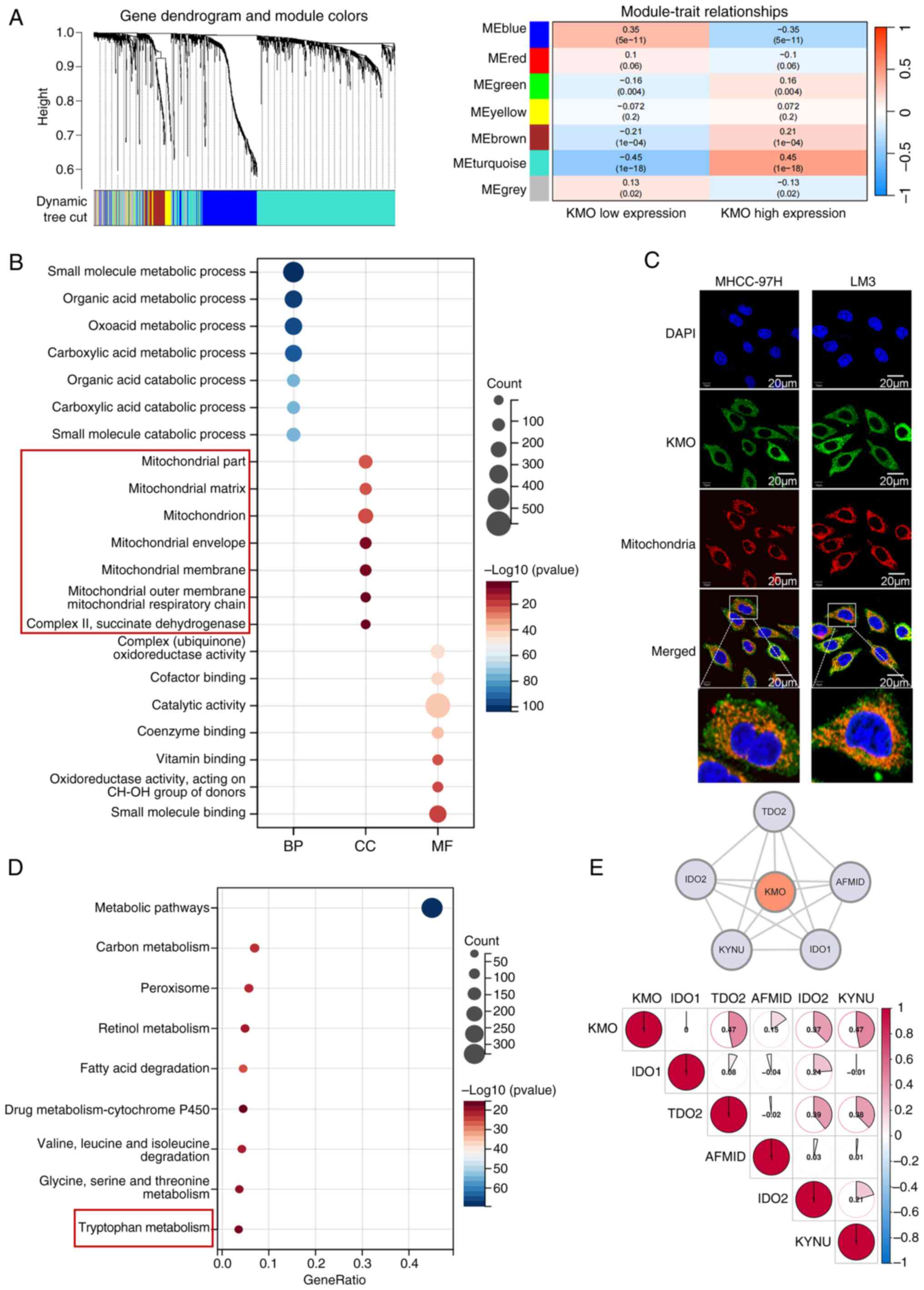

WGCNA showed MEturquoise module was correlated with

KMO expression with a biggest correlation coefficient (0.45) and

designating it as a key gene module that may be co-expressed with

KMO (Fig. 4A). A total of 1,433

genes in MEturquoise module were extracted for gene function

enrichment analysis. GO enrichment analysis showed in biological

processing, KMO co-expressed related genes participated in

metabolic related pathways; in terms of cell components, KMO

co-expression related genes are closely related to mitochondria; In

terms of molecular function, KMO co-expression related genes may

affect oxidoreductase activity, cofactor and coenzyme binding

(Fig. 4B). These findings suggest

KMO's potential role in many metabolic processes and its close

association with mitochondrial structure and function, which was

further supported by immunofluorescence experiments confirming the

co-localization of KMO with mitochondria in HCC cells (Fig. 4C). KEGG enrichment results

indicated that KMO co-expression related genes were related to Try

metabolism (Fig. 4D). A PPI

network constructed by six key genes of Try metabolic pathway from

GSEA official website showed that KMO had direct interaction with

IDO1, TDO2, IDO2, arylformamidase (AFMID), TDO2 and kynureninase

(KYNU) with the correlation coefficients were 0, 0.47, 0.15, 0.37

and 0.47 respectively (Fig. 4E).

These results suggest that KMO may reside in mitochondria and

functionally interacts with other genes to influence the Try

metabolic pathway.

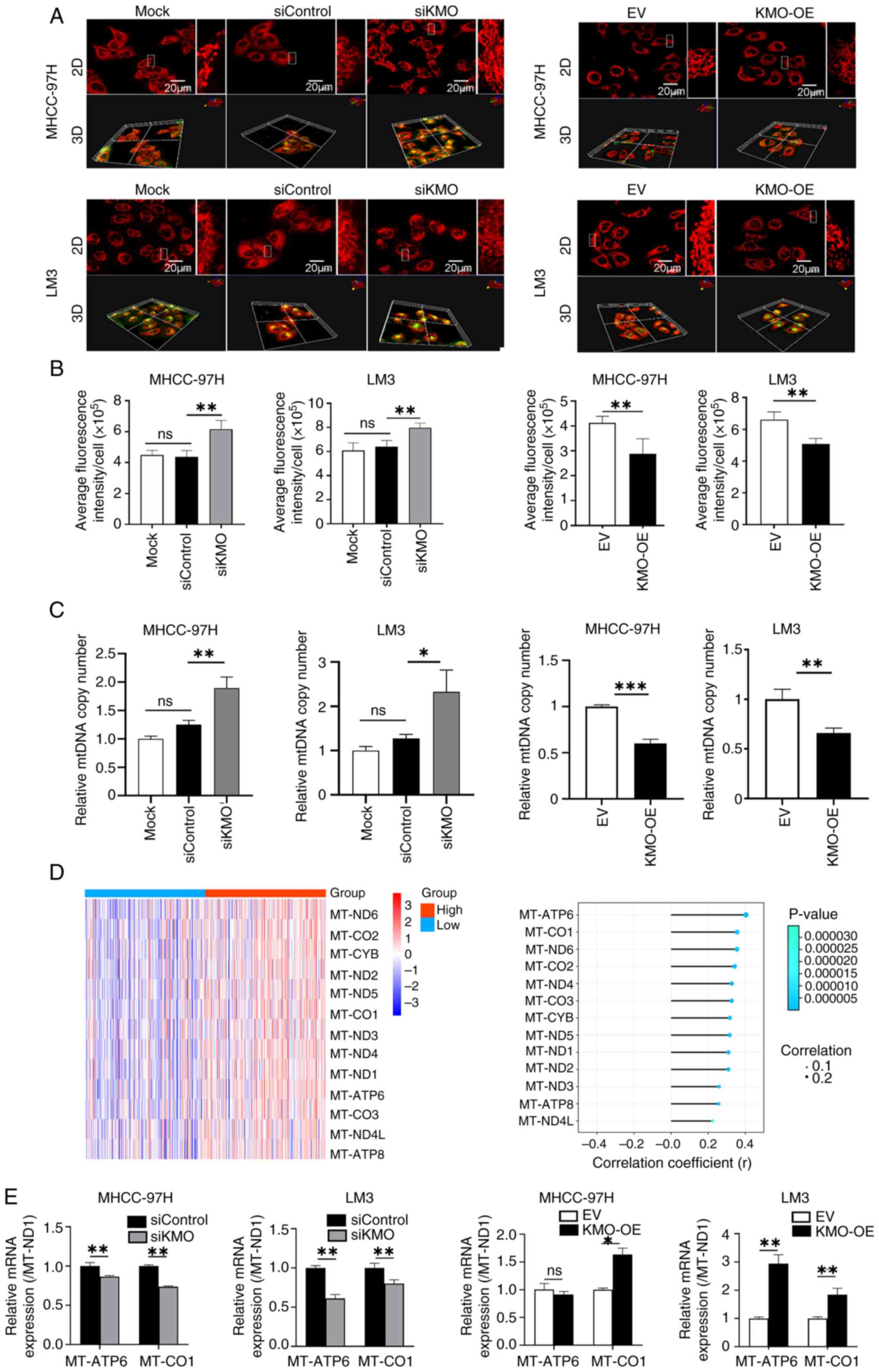

KMO downregulation increases

mitochondrial mass

Mitochondrial dysfunction is closely related to

mitochondrial metabolic disorder and the occurrence and progression

of HCC. Mito-Tracker staining was used to detect mitochondrial

biogenesis and the 3D image statistical results showed that in

MHCC-97H cells and LM3 cells, the mitochondrial mass in siKMO group

was increased compared with that in siControl group. Conversely,

KMO overexpression reduced mitochondrial mass relative to the EV

control group (Fig. 5A and B).

The present study detected the copy number of mtDNA coding gene ND1

to further verify whether KMO is related to mitochondrial

biogenesis. The results showed that compared with siControl group,

the ND1 copy number in siKMO group was increased significantly.

Compared with EV group, ND1 copy number in KMO-OE group was

decreased (Fig. 5C).

In addition, analysis of transcriptomic data

revealed that all 13 genes encoded by the mitochondrial genome were

upregulated in high-KMO expression patient samples and were

positively correlated with KMO expression (Fig. 5D). Then the expression of two

genes with the strongest correlation with KMO, MT-ATP6 and MT-CO1

was validated by using qPCR in KMO knockdown and overexpression HCC

cells (Fig. 5E).

These results indicated that the downregulation of

KMO in HCC cells promoted mitochondrial biogenesis. The

uncoordinated changes in mitochondrial DNA copy number and

mitochondrial gene expression suggested that KMO dysregulation can

lead to imbalances in mitochondrial mass and function.

KMO downregulation promotes HCC cells

proliferation and mitochondrial alterations by reducing 3-HAA

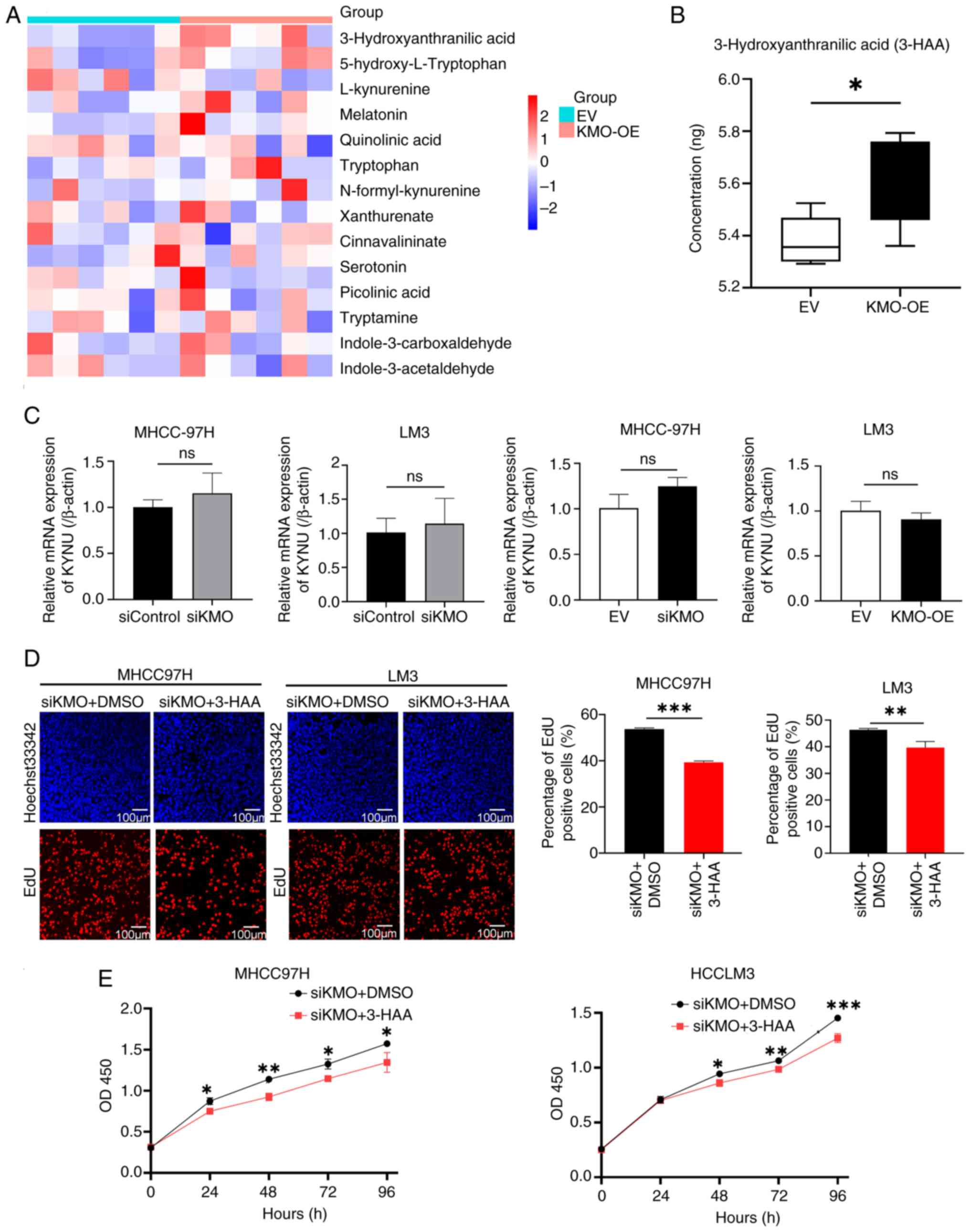

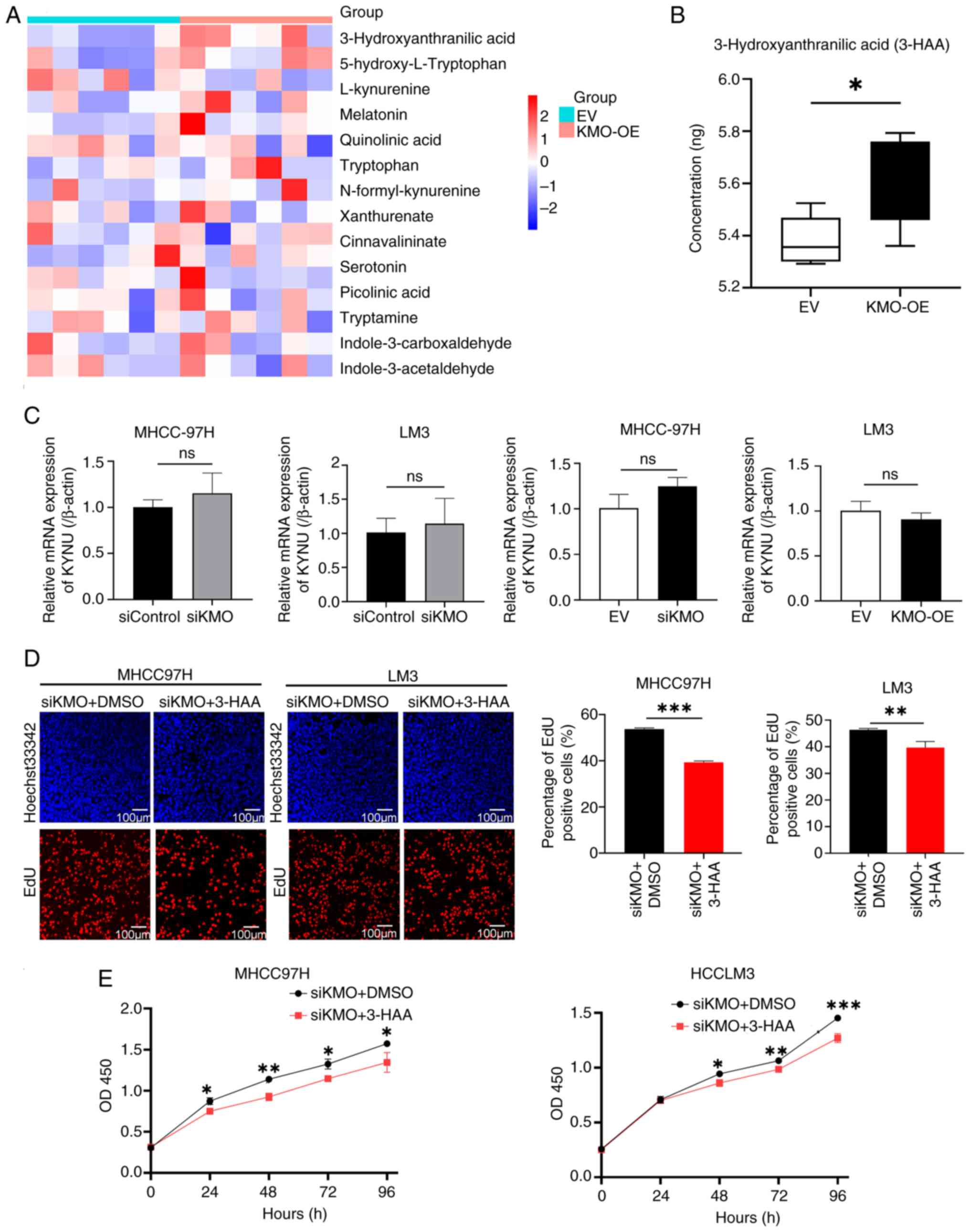

production

In order to investigate how KMO influences Try

metabolism, HPLC-MS methods were used to test the content of Try

metabolites in HCC LM3 cells overexpressing KMO. Fig. S4 showed the total ion flow mass

spectrometry of HCC cells. Among the total 16 metabolites detected,

3-HAA was the only one significantly elevated in HCC cells

overexpressing KMO (Figs. S5 and 6A

and B). Next, the expression of kynureninase (KYNU), the enzyme

immediately downstream of KMO that catalyzes the conversion of

3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) to 3-HAA was detected. No statistical

significance was found in siKMO or KMO-OE group compared with their

control groups (Fig. 6C),

suggesting the changes in 3-HAA levels was directly mediated by KMO

and independent of KYNU.

| Figure 6Downregulation of KMO induced the

decrease of 3-HAA level promotes HCC cells proliferation. (A)

Heatmap showed tryptophan metabolites levels in KMO overexpression

and control HCC cell groups. (B) Comparison of 3-HAA levels between

KMO overexpression group and control group. (C) mRNA expression of

KYNU in KMO knockdown and overexpression HCC cells by using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. (D) Effect of 3-HAA on cell

proliferation in KMO knockdown HCC cells by using EdU detection.

EdU labeled newly proliferated cells (red) and Hoechst33342 labeled

cell nucleus (blue). Positive cells rate (red/blue) were counted

and compared between KMO-knockdown cells treated with DMSO

(control) and KMO-knockdown cells treated with 3-HAA groups. Scale

bar, 100 µm. (E) Effect of 3-HAA on cell viability in KMO

knockdown HCC cells by using CCK8 test on 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h.

The cell proliferation rates of KMO knockdown cells treated with

3-HAA or DMSO at the same time were compared. Final working

concentration of 3-HAA: 100 µM. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, P>0.05.

KMO, kynurenine 3-monooxygenase; 3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid;

KYNU, kynureninase. |

The present study further explored whether KMO

downregulation induced cell proliferation is caused by 3-HAA. In

siKMO HCC cells, 3-HAA can reverse the increased cell proliferation

and vitality caused by KMO knockdown (Fig. 6D and E).

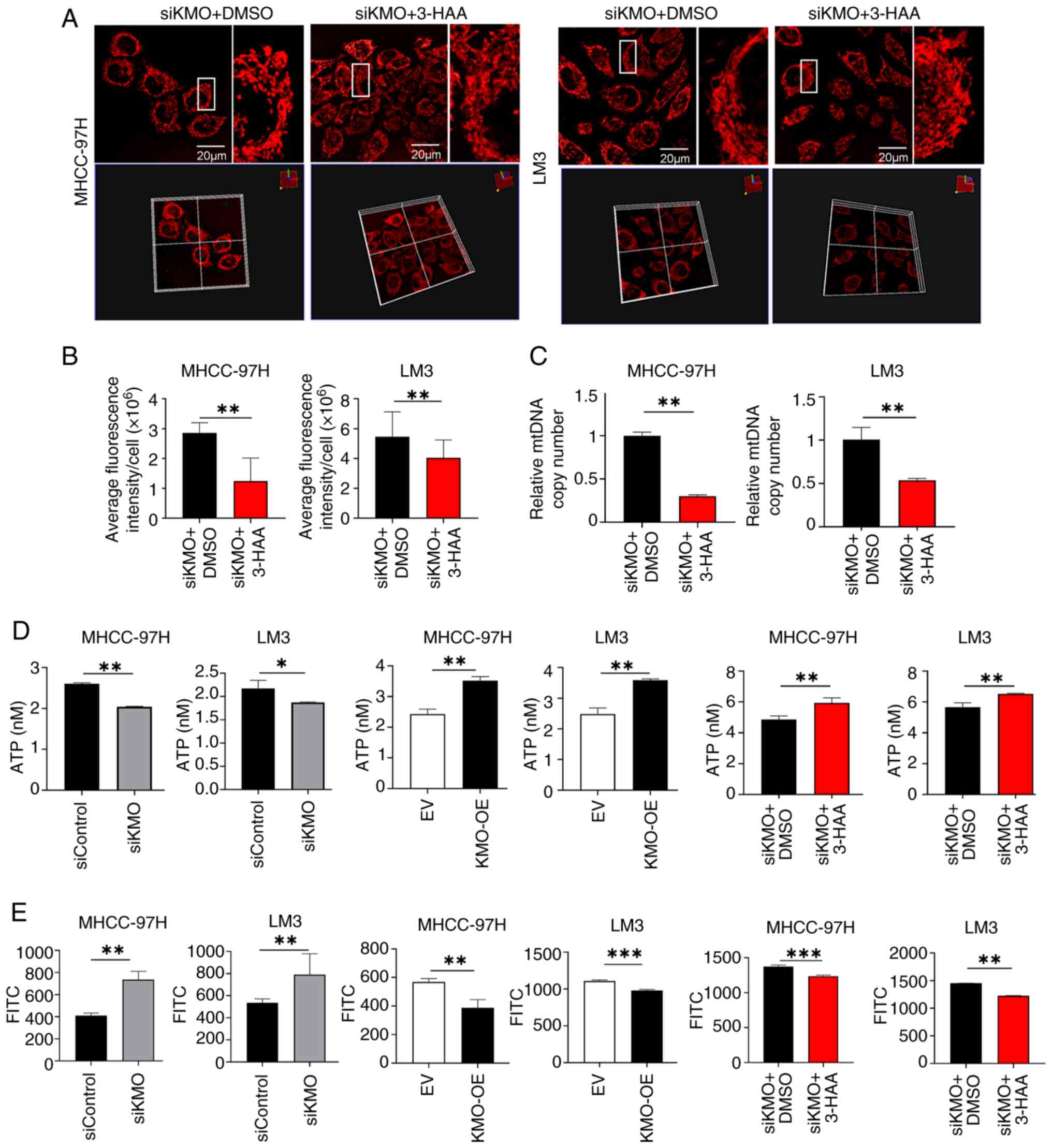

Similarly, it was investigated whether the

mitochondrial changes induced by KMO are mediated by 3-HAA. As

shown in Fig. 7A and B, in both

MHCC97H and LM3 cells, after treatment with 3-HAA in siKMO cells

for 48 h, the mitochondrial mass was decreased compared with the

control group. The mtDNA copy number was significantly reduced in

siKMO cells treated with 3-HAA compared to those treated with DMSO

(Fig. 7C). ATP content in siKMO

HCC cells was lower than that in control cells, while in KMO-OE HCC

cells was higher. And 3-HAA can up regulate the ATP content

decreased by KMO knockdown (Fig.

7D). ROS generation showed an opposite trend to ATP production

and 3-HAA inhibited the ROS generation upregulated by KMO knockdown

(Fig. 7E)

These results indicate that downregulation of KMO in

HCC reduces the production of its downstream metabolite 3-HAA,

thereby promoting HCC progression and inducing alterations in

mitochondrial mass and function.

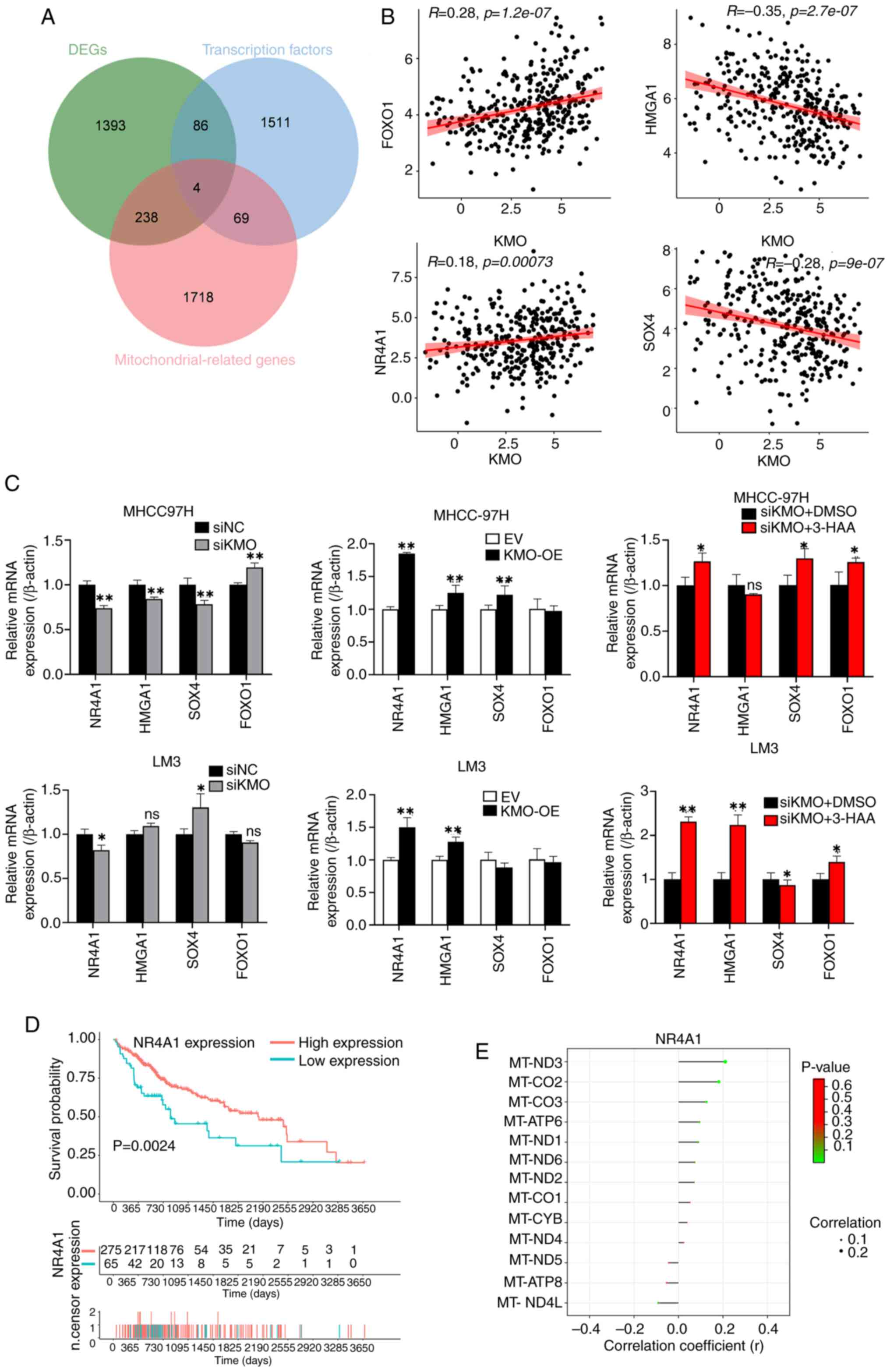

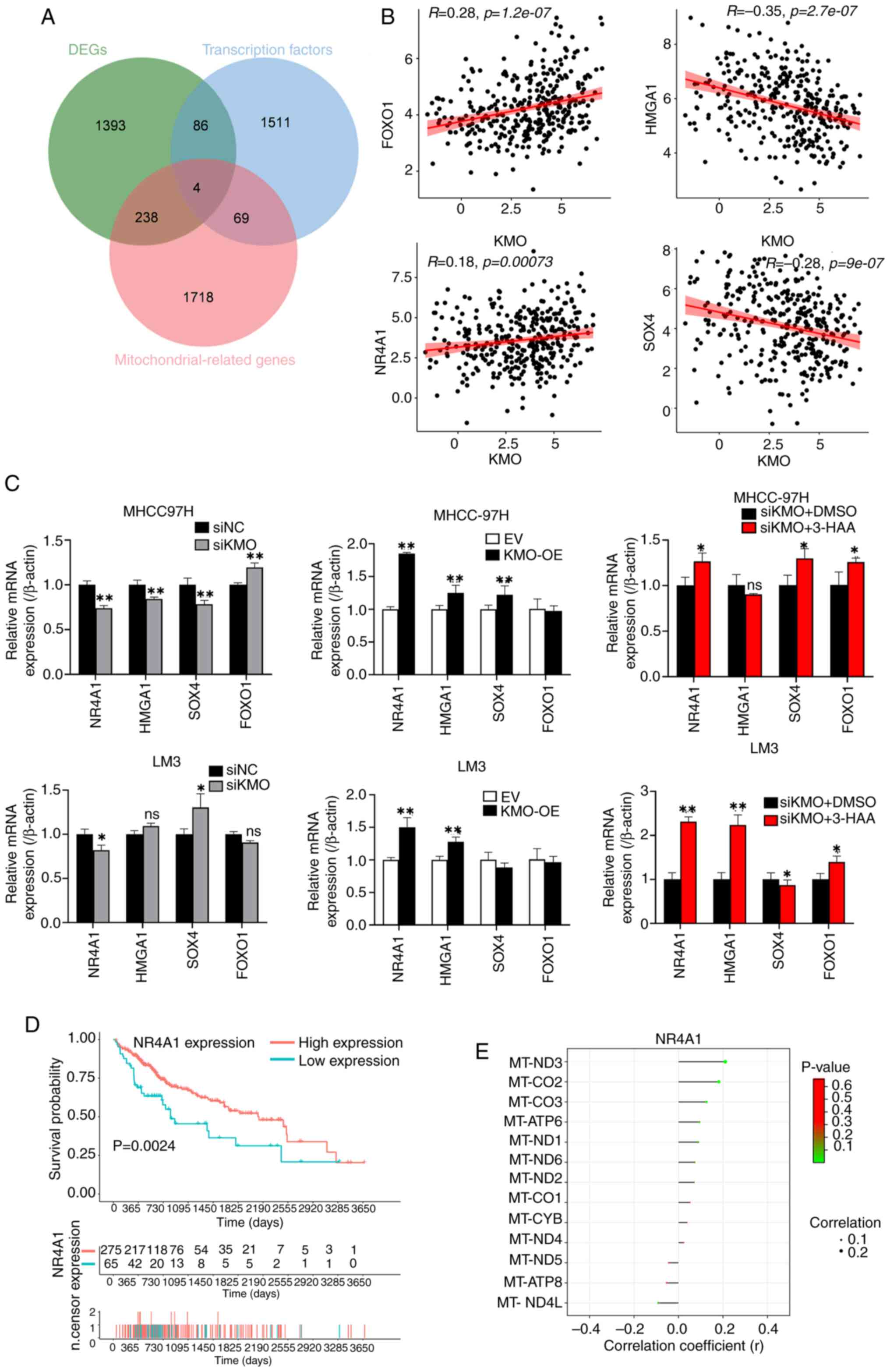

KMO downregulation reduces the expression

of nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member 1 (NR4A1) and

promotes its mitochondria translocation in a 3-HAA-dependent

manner

To investigate the mechanisms underlying the

mitochondrial alterations induced by KMO downregulation, the

present study screened mitochondrial transcription factors

associated with KMO expression. A total of 1,670 transcription

factor genes downloaded from GTRD website (http://gtrd.biouml.org), were intersected with 2,030

mitochondrial-related genes and 1,721 DEGs between KMO high and low

groups (26). A total of four KMO

related mitochondrial transcription factors were obtained (Fig. 8A). In these four transcription

factors, the expression of KMO was positively correlated with the

expression of FOXO1 and NR4A1, while negatively correlated with the

expression of HMGA1 and SOX4 (Fig.

8B). After qPCR verification, only NR4A1 expression was

consistent with the data analysis: It positively correlated with

KMO expression in HCC cells and 3-HAA treatment rescued in the

downregulation of NR4A1 expression caused by KMO knockdown

(Fig. 8C). Low NR4A1 expression

was associated with poor prognosis in HCC patients (Fig. 8D). Similar to KMO, NR4A1

expression was positively correlated with the expression of ten

mitochondrial genome-encoded genes (Fig. 8E).

| Figure 8Downregulation of KMO promotes the

decrease of NR4A1 in HCC cells. (A) Venn diagram among KMO related

DEGs, transcription factors and mitochondrial related genes. The

overlapped four genes are the screened mitochondrial related

transcription factors from KMO related DEGs. (B) Correlation

analysis between KMO and four mitochondrial related transcription

factors screened using TCGA database. (C) mRNA expression of four

mitochondrial related transcription factors in KMO-knockdown,

overexpression and 3-HAA treated KMO-knockdown HCC cells and the

corresponding controls. (D) Survival analysis of NR4A1 in HCC

patients in TCGA database. (E) The correlation analysis between

NR4A1 and mitochondrial DNA-encoded genes in HCC. Final working

concentration of 3-HAA: 100 µM. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ns: P>0.05. KMO, kynurenine

3-monooxygenase; NR4A1, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member

1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; DEGs, differentially expressed

genes; TCGA, the Cancer Genome Atlas; 3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic

acid. |

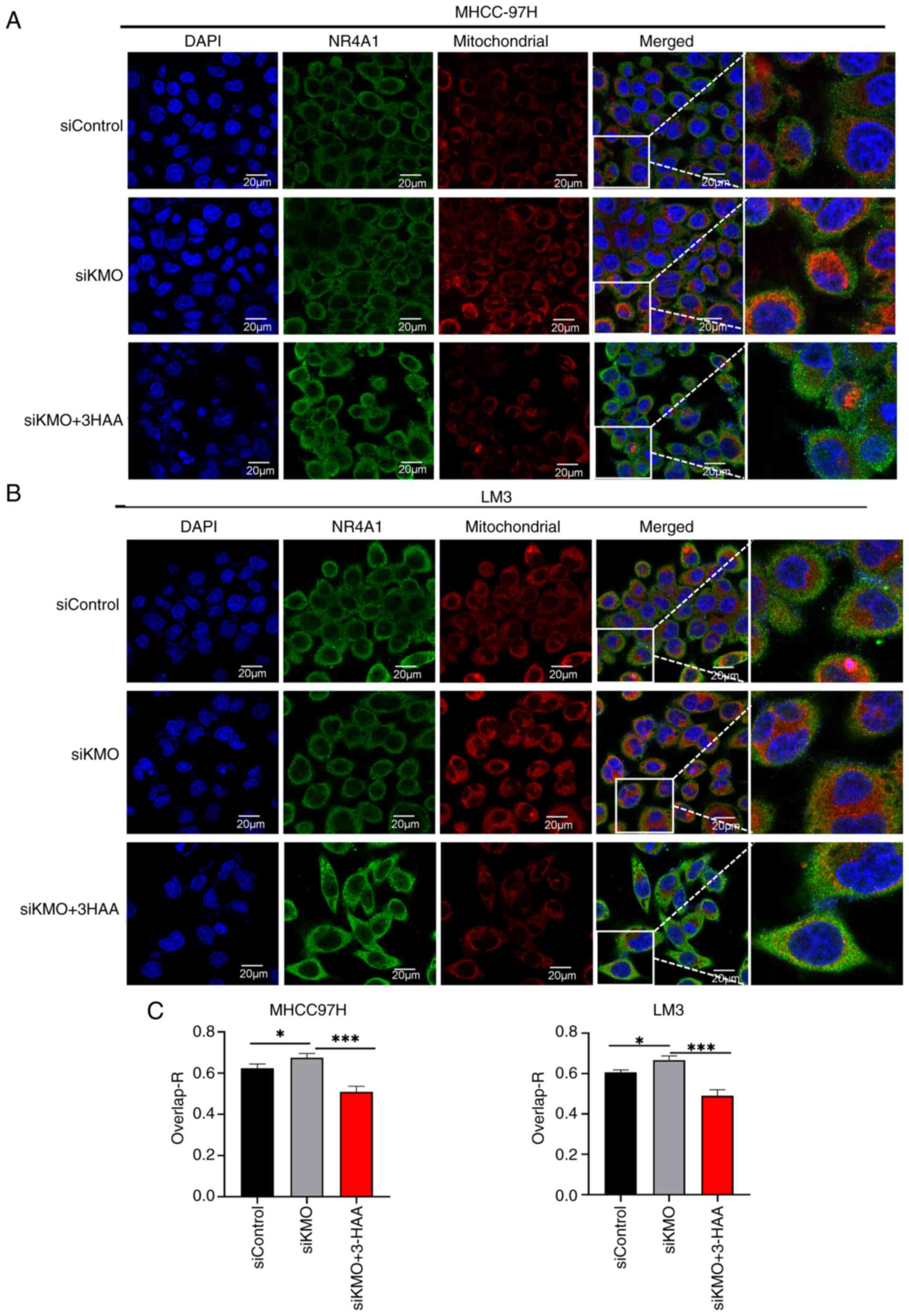

Since NR4A1 is a mitochondria-associated

transcription factor, the present study was interested in finding

out the subcellular localization of NR4A1. After immunofluorescence

staining, it was observed that KMO expression in HCC cells was

distributed in both nucleus and cytoplasm. Combined with

fluorescent staining of mitochondrial Mito-Tracker, NR4A1 showed

increased expression in mitochondria in KMO knockdown HCC cells,

whereas NR4A1 expression in mitochondria was reduced after

overexpression of KMO. 3-HAA reversed the mitochondrial

translocation of NR4A1 induced by KMO knockdown (Fig. 9).

These results illustrated that downregulation of KMO

in HCC cells can lead to reduced NR4A1 expression and promotes its

mitochondrial translocation, both of which are mediated by

3-HAA.

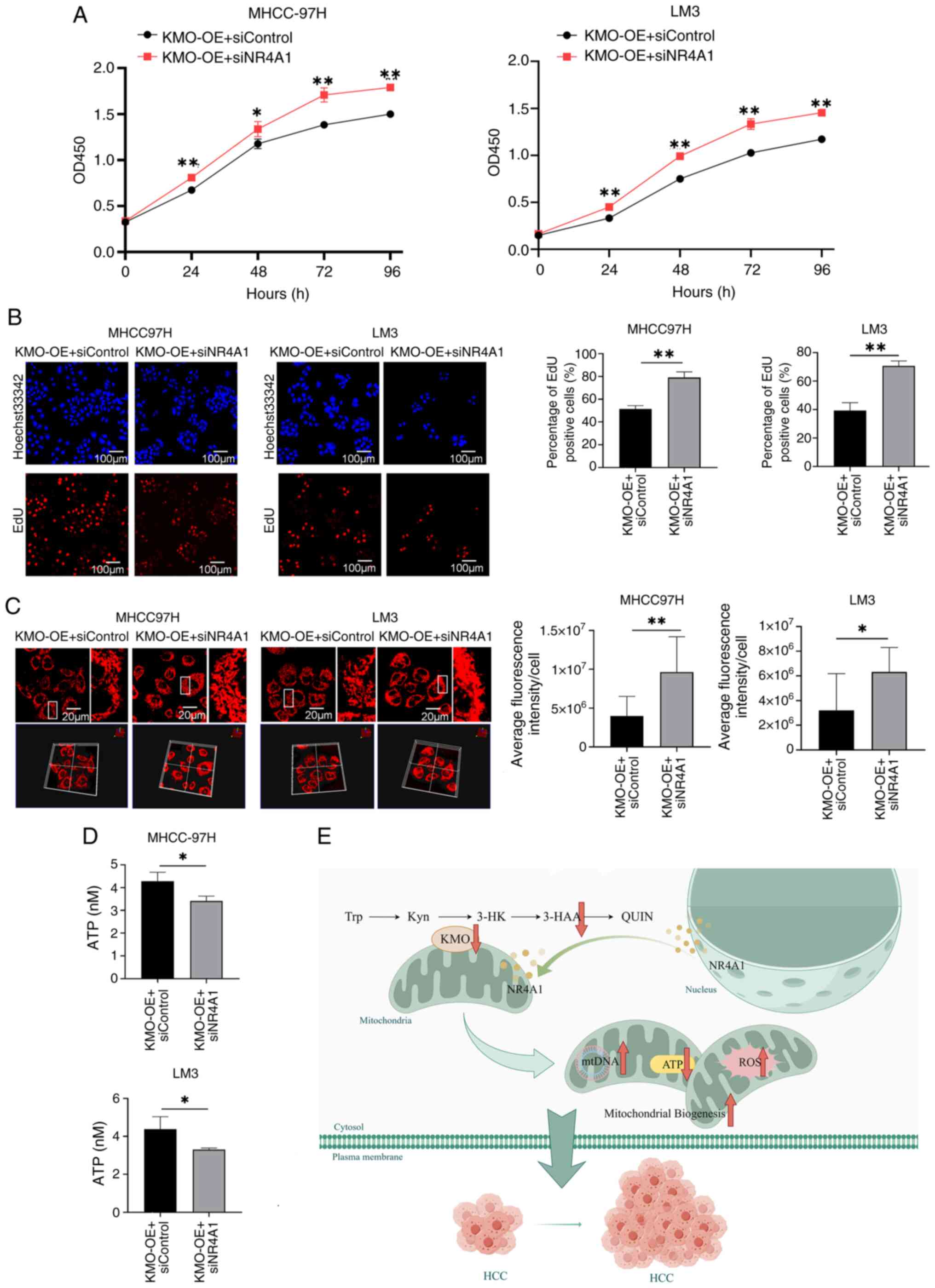

The decrease of NR4A1 induced by

downregulation of KMO promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and

malignant growth of HCC cells

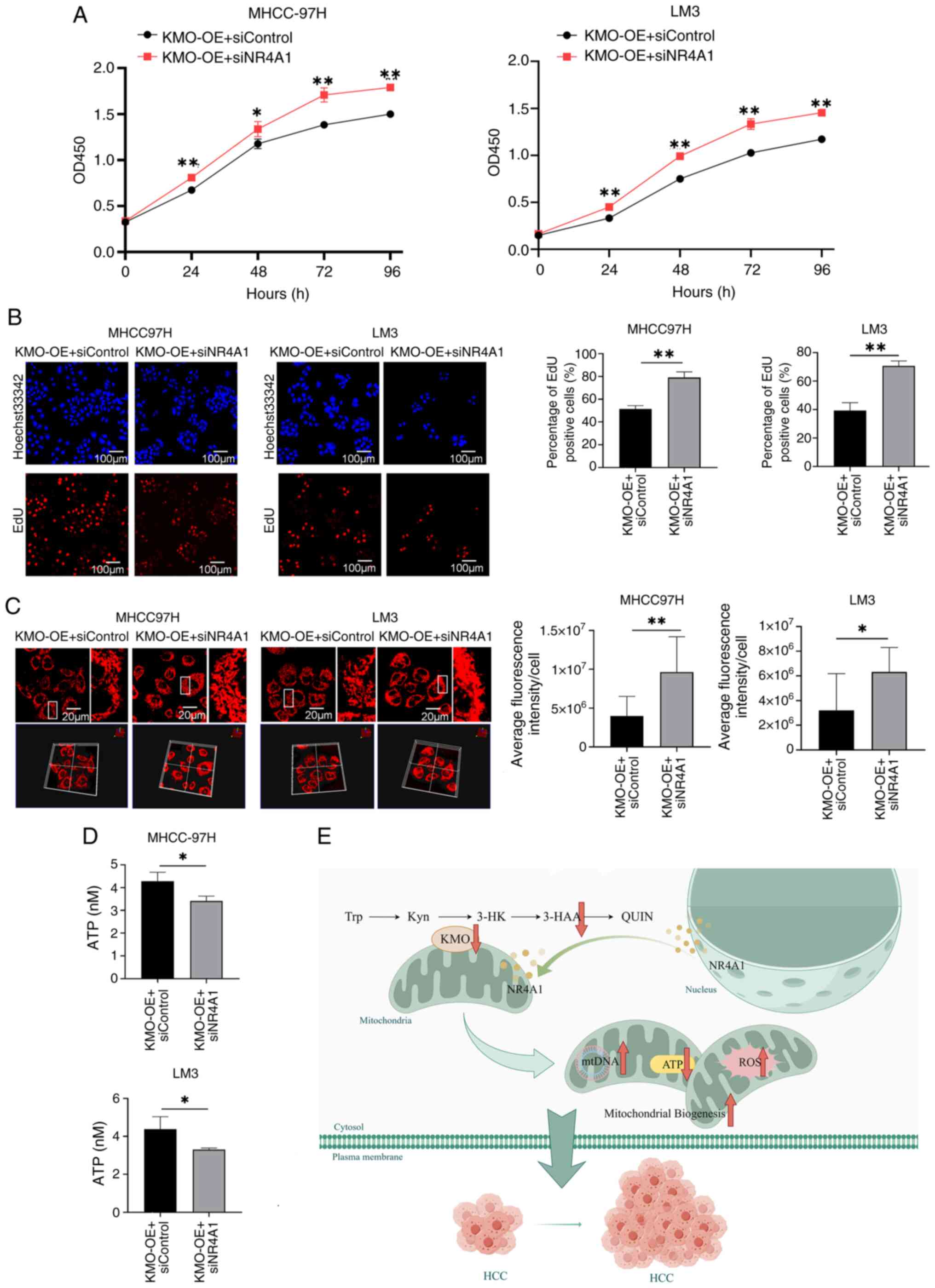

In KMO overexpressed HCC cells, the expression of

NR4A1 was knocked down to investigate the effect of KMO-mediated

NR4A1 on HCC cell growth and mitochondrial mass and function. CCK8

and EdU results showed that silencing of NR4A1 enhanced cell

viability and proliferation in HCC cells overexpressing KMO

(Fig. 10A and B). NR4A1

knockdown increased mitochondrial mass in HCC cells overexpressing

KMO compared with siControl cells (Fig. 10C). Additionally, ATP production

also decreased by NR4A1 knockdown in KMO overexpressed HCC cells

(Fig. 10D). These results

indicated that NR4A1 inhibition promotes mitochondrial biogenesis

and the malignant growth of HCC cells.

| Figure 10KMO affects cell growth,

mitochondrial quality and ATP production through NR4A1. (A) Effect

of NR4A1 downregulation on cell viability in KMO overexpression HCC

cells was observed by using CCK8 test on 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h.

The cell viability rates between KMO overexpression cells

transfected with siKMO and transfected with siControl were

compared. (B) Effect of NR4A1 downregulation on cell proliferation

in KMO overexpression HCC cells was observed by using EdU test. EdU

labeled newly proliferated cells (red) and Hoechst33342 labeled

cell nucleus (blue). Scale bar, 100 µm. Positive cells rate

(red/blue) were counted and compared between KMO overexpression

cells and KMO overexpression cells with NR4A1 knockdown. (C) Effect

of NR4A1 downregulation on mitochondrial mass in KMO overexpression

HCC cells was observed by using confocal microscopy after

MitoTracker staining. The parts in white box were magnified. Scale

bar, 20 µm. Mitochondrial mass was analyzed by using the

value of average fluorescence intensity per cell. (D) Effect of

NR4A1 downregulation on ATP production in KMO overexpression HCC

cells. (E) The mechanism of KMO downregulation promoting tumor

growth in HCC: KMO downregulation reduced 3-HAA levels, which

suppressed expression of the transcription factor NR4A1 and drove

its mitochondrial translocation, thereby disrupting mitochondrial

homeostasis and promoting the proliferation of HCC cells.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. KMO, kynurenine

3-monooxygenase; NR4A1, nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member

1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; 3-HAA, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid;

ROS, reactive oxygen species; 3-HK, 3-hydroxykynurenine QUIN,

quinolinic acid; Try, tryptophan; Kyn, kynurenine. |

Discussion

Abnormalities in Try metabolism, as well as

mitochondrial structure and function, are involved in the

development of HCC. As a key enzyme in the Try metabolic pathway,

KMO co-localizes with mitochondria. However, to the best of the

authors' knowledge, the effects of KMO on mitochondrial mass and

function in HCC have not yet been reported. The present study

identified that KMO expression was downregulated in HCC patients

through multiple public datasets and further validated this finding

in tissue samples. Furthermore, KMO downregulation in HCC cells was

shown to promote tumor cell proliferation and migration. The

co-localization of KMO and mitochondria was determined in HCC cells

and the downregulation of KMO promoted mitochondrial biogenesis.

Mechanistically, low expression of KMO in HCC cells reduced 3-HAA

levels, which suppressed expression of the transcription factor

NR4A1 and drove its mitochondrial translocation, thereby disrupting

mitochondrial homeostasis and promoting the proliferation of HCC

cells (Fig. 10E).

Try metabolism through the Kyn pathway serves an

immunosuppressive role in liver cancer (27). However, the distinction between

the immunomodulatory effects of Try itself and the effects of

downstream products of Try metabolism remains unclear (28). KMO is involved in Try metabolism

through the Kyn pathway, which exists mainly in the liver and ~95%

of Try is oxidatively degraded via this pathway (29). In the current study, multiple

datasets and experiments validated that KMO expression was reduced

in HCC and was associated with a poor prognosis in patients with

HCC. In HCC cells with KMO knockdown and overexpression, it was

also verified that reduction of KMO promoted the malignant

progression of HCC tumor cells. These results are consistent with

the findings of Shi et al (20). A possible theory is that the

downregulation of KMO disrupts the Kyn pathway and induces the

accumulation of Kyn, which suppresses immune cell populations and

increases tumor growth (30).

Notably, it may also promote tumor progression by affecting the

generation of downstream products of the Kyn pathway. In addition,

the results of single-cell sequencing data analysis revealed that

KMO expression was downregulated in DC, epithelial and tumor cells

and MDSC from HCC tissue, suggesting that KMO expression in DC,

epithelial and tumor cells and MDSC has an antitumor effect and

requires further study.

KMO has previously been reported to be localized on

the outer mitochondrial membrane of pig liver (9). A previous study found that

inhibition of KMO can effectively inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis

and ferroptosis by regulating mitochondrial fission and fusion

(31). Chen et al

(32) demonstrated that KMO, as a

key gene for mitochondrial dysfunction, has important diagnostic

value for intracranial aneurysms. Downregulation of KMO expression

has also been found to enhance mitochondrial fusion and inhibit

mitophagy in ischemic stroke (33). These studies have revealed that

KMO can be involved in disease development by affecting

mitochondrial structure or function. The present study confirmed

the co-localization of KMO with mitochondria in HCC cells.

Furthermore, GO enrichment analyses of KMO co-expressed genes

showed that these genes were related to mitochondrial structural

components and in HCC cells, the expression of KMO affected the

mitochondrial mass, mitochondrial biogenesis and expression of

mitochondrial encoded genes. In particular, the opposability of

mitochondrial mass to mitochondrial encoded gene expression points

to a state of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Try is initially metabolized by IDO1, IDO2 and TDO

to produce Kyn. One of the three Kyn metabolic pathways includes

the catalysis of Kyn by KMO to form 3-HK, which is subsequently

converted to 3-HAA by KYNU. 3-HAA is further metabolized by

3-hydroxyl amino acid oxygenase to generate quinolinic acid (QUIN).

QUIN serves as a substrate for the production of nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide, which is involved in a variety of important

physiological processes, such as intracellular energy metabolism,

DNA repair and signal transduction (34). Notably, KMO expression has the

potential to influence its downstream metabolites. Since KMO

expression was downregulated in HCC, the current study chose HCC

cells overexpressing KMO to detect Try metabolites. The results

showed that only 3-HAA was increased in HCC cells overexpressing

KMO compared with that in the control cells, whereas 3-HK, a direct

metabolite of KMO, was not detected. The reason for this phenomenon

may be that KYNU has a strong metabolizing ability for 3-HK, while

both silencing and overexpression of KMO did not affect KYNU

expression. It may be assumed that upregulated KMO mainly enhanced

3-HAA levels. It has previously been reported that the Kyn

derivative 3-HAA is lower in HCC cells and exogenous 3-HAA induces

the apoptosis of HCC cells by binding the transcription factor YY1

(24). In a mouse model of HCC,

3-HAA treatment has been reported to inhibit HCC growth by

regulating the function of macrophages (35). Gan et al (36,37) also demonstrated that 3-HAA may

sensitize HCC cells to sorafenib by reducing AKT phosphorylation,

promoting apoptosis and suppressing tumor cell stemness. In

conclusion, 3-HAA could inhibit HCC progression through multiple

mechanisms, including the induction of apoptosis and reduction of

stemness, indicating that it may serve as a promising therapeutic

target for HCC.

The present study also observed that 3-HAA could

reverse the malignant phenotype of HCC cells caused by KMO

downregulation. In addition, 3-HAA-treated cancer cells exhibited a

reversal of the changes in mitochondrial mass, mitochondrial

biogenesis, ATP and ROS production caused by KMO. The possible

mechanisms underlying how 3-HAA could ameliorate HCC were

elaborated from a new perspective in the present study. It has

previously been reported that M2 macrophage-secreted KYNU and 3-HAA

may upregulate the expression of superoxide dismutase 2 to decrease

mitochondrial ROS in endometrial cancer. Although this previous

study concluded that high KYNU and 3-HAA promote endometrial cancer

progression, it also provides valuable evidence for the association

between 3-HAA and mitochondria (38). Ruan et al (39) reported that bronchopulmonary

dysplasia (BPD) was associated with markedly reduced 3-HAA levels

and exhibited typical ferroptosis-associated changes, such as

mitochondrial pyknosis and loss of cristae, whereas 3-HAA treatment

could attenuate these mitochondrial abnormalities in type Ⅱ

alveolar epithelial cells, suggesting 3-HAA as a potential target

for treating BPD.

To further clarify the regulatory mechanism by which

KMO downregulation mediates the reduction of 3-HAA affecting

mitochondrial function, the present study explored the

mitochondria-related transcription factors that may be affected by

KMO expression. As a result, NR4A1 was revealed to be positively

correlated with KMO expression in HCC cells. NR4A1, also known as

Nur77, affects tumorigenesis and tumor progression via various

cellular processes, such as proliferation, endoplasmic reticulum

stress, apoptosis and autophagy (40,41). Based on the cancer type and stage,

NR4A1 can exhibit both pro-tumorigenic and tumor-suppressive

effects via transcription-dependent and transcription-independent

manners (41). In liver cancer,

the low expression of NR4A1 can promote HCC progression by

increasing glycolysis, inhibiting apoptosis or regulating β-catenin

expression (42-44). In the current study, downregulated

NR4A1 was associated with poor survival in patients with HCC and

NR4A1 was also shown to be positively related to the expression of

the majority of mtDNA encoded genes, such as MT-ATP6 and MT-ND1,

thus suggesting that low expression of NR4A1 in HCC also affects

mitochondrial function. It has been reported that NR4A1 promotes

apoptosis in HCC cells when its cytoplasmic expression is increased

(44). NR4A1 translocated to the

mitochondria can promote the transformation of the anti-apoptotic

protein Bcl-2 into a pro-apoptotic state, interfere with

mitochondrial division and fusion, inhibit mitochondrial autophagy

and lead to irreversible mitochondrial damage and cell apoptosis

(45). In a model of myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury, NR4A1 has been shown to be elevated

and may promote mitochondrial fission by regulating mitochondrial

fission 1 protein (46).

Furthermore, the synergistic effect of NR4A1 and YY1 on macrophages

can increase the abundance and activity of mitochondria (47). However, in Parkinson's disease

research, it has been reported that NR4A1, which shuttles from the

nucleus to the mitochondria, can inhibit apoptosis by stabilizing

the presenilin-associated mitochondrial like protein (PARL)-Bcl-2

complex, thereby overexpression of NR4A1 can restore PARL-mediated

anti-apoptotic signaling for therapeutic purposes (48). In the present study, the

subcellular localization of NR4A1 was assessed in siKMO HCC cells

to determine the effect of KMO on NR4A1 translocation.

Unexpectedly, compared with in the control cells, although the

expression of NR4A1 was reduced, co-localization with mitochondria

was increased in siKMO HCC cells. The reasons for this phenomenon

are likely to be complex: Total NR4A1 expression was reduced after

KMO interference; however, mitochondrial mass was increased, which

possibly enhanced shuttling of NR4A1 from the nucleus to the

mitochondria. When siKMO HCC cells were treated with 3-HAA, the

expression of NR4A1 was increased and co-localization with the

mitochondria was decreased, implying that KMO may regulate the

expression and translocation of NR4A1 induced by 3-HAA. NR4A1

exerts an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation in the nucleus

and its reduction and mitochondrial translocation will promote HCC

cell proliferation; however, whether NR4A1 promotes apoptosis or

inhibits apoptosis in the mitochondria requires an improved

experimental design for verification. It may play a role in

promoting apoptosis; however, due to the reduction in NR4A1,

although mitochondrial co-localization is enhanced, the overall

effect on HCC cell proliferation may be more notable than the

effect on apoptosis. In addition, the pro-apoptotic function of

mitochondrial NR4A1 may be abrogated due to its critically low

overall expression level. The subsequent cellular experiments in

the present study also demonstrated that in HCC cells

overexpressing KMO, downregulation of NR4A1 expression promoted

tumor cell proliferation, increased mitochondrial mass and

decreased ATP. These findings indicated the importance of KMO,

3-HAA and NR4A1 in liver carcinogenesis; however, further studies

are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanism using a broader

panel of HCC cell lines and rescue experiments.

By employing a multi-faceted approach, the rigor and

validity of the current conclusions were strengthened. The cellular

mechanistic studies complemented those of public large-scale human

HCC transcriptomics datasets (TCGA and GEO datasets), enhancing the

clinical relevance of the study. The present data showed that in

patients with HCC and in HCC cell models, the lack of KMO may lead

to the progression of HCC. Therefore, targeting KMO and related

molecules, as well as the associated signaling pathways, may be a

promising therapeutic strategy for HCC. The feasible strategies

include but are not limited to: i) Based on the bulk mRNA

sequencing data of the adult population, the drug sensitivity in

the KMO low and high expression groups could be predicted and

patients with HCC may choose more precision treatment drugs

according to KMO expression; ii) KMO downstream metabolites, such

as 3-HAA, as small molecule compounds, have not yet become approved

therapeutic drugs, but 3-HAA is a potential candidate drug that is

currently undergoing extensive research; iii) concurrent inhibition

of the upstream enzyme IDO1/TDO and enhancement of the downstream

enzyme KMO in Try metabolism could exert a synergistic effect,

leading to a more potent reversal of immunosuppression through the

reduction of Kyn buildup.

The present study focused on investigating the

influence of the key enzyme in Try metabolism, KMO, on disordered

mitochondria in the development of HCC. Despite yielding valuable

insights, several limitations remain. Firstly, the study was

conducted at the cellular level based on publicly available

datasets and lacked experimental validation at the animal level.

Second, the mechanism of NR4A1 translocation induced by KMO or

3-HAA requires further exploration. Third, further experiments need

to be designed and performed to investigate the differential

functions of NR4A1 in the nucleus and mitochondria of HCC cells and

animal models. Fourth, the method for detecting mitochondrial

morphology in this study was relatively limited, it is necessary to

employ a variety of further detection methods to determine the

changes of mitochondrial morphology and structure. Finally, it will

be necessary to assess the mechanism underlying the effects of KMO

downregulation on increased mitochondrial mass and dysfunction in

the future.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that low

KMO expression in HCC may affect mitochondrial mass and function by

reducing the level of the Try metabolite 3-HAA and downregulating

the expression of NR4A1 and promoting its mitochondrial

translocation, which in turn could promote the progression of HCC.

KMO agonists are expected to achieve two goals simultaneously in

alleviating HCC: Restoring the Try metabolic pathway and enhancing

NR4A1 expression. The present findings provide new insights into

the treatment of HCC, potentially targeting the mitochondria and

the Try-Kyn pathway.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The GEO datasets are available for download from the

National Center for Biotechnology Information online Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE101728,

GSE45050, GSE84598 and GSE121248). TCGA-LIHC data was downloaded

from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/; TCGA-LIHC) and

relative phenotype and survival data are from University of

California Santa Cruz (UCSC) [https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/, TCGA Liver Cancer

(LIHC)]. Cell annotation lists are available online at Cell Marker

2.0 (http://117.50.127.228/CellMarker/). R and other

custom scripts for analyzing the data may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

ML, HW and JZ designed the experiments, acquired

and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. XZ and YH

completed the data analysis and cell experiments. LN, LG and FL

collected the HCC tissue samples, completed the tissue experiments,

and interpreted the data. GZ, FJ and LL analyzed, checked the data,

and edited the manuscript. ML and JZ confirmed the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the ethics

committee of the First Hospital of Shanxi Medical University

(approval number: 2021SLL086). All patients understood and signed

the informed consent. All patients consent for publication.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

KMO

|

kynurenine 3-monooxygenase

|

|

3-HAA

|

3-hydroxyanthranilic acid

|

|

NR4A1

|

nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A

member 1

|

|

Try

|

tryptophan

|

|

Kyn

|

kynurenine

|

|

TDO

|

tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase

|

|

mtDNA

|

mitochondrial DNA

|

|

GEO

|

gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

MRDEGs

|

mitochondrial related DEGs

|

|

TCGA

|

the Cancer Genome Atlas

|

|

LIHC

|

liver hepatocellular carcinoma.

WGCNA, weighted gene co-expression network analysis

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

PPI

|

protein-protein interaction

|

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81902513), Applied Basic Research

Project of Shanxi Province (grant no. 202303021211114, grant no.

20210302123319, grant no. 20210302124376 and grant no.

202103021224228), Science Research Start-up fund for doctor of

Shanxi Medical University (grant nos. XD1808 and BS03201603) and

Shanxi Province Higher Education 'Billion Project' Science and

Technology Guidance Project (grant no. BYJL047).

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rumgay H, Ferlay J, de Martel C, Georges

D, Ibrahim AS, Zheng R, Wei W, Lemmens VEPP and Soerjomataram I:

Global, regional and national burden of primary liver cancer by

subtype. Eur J Cancer. 161:108–118. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

de Martel C, Georges D, Bray F, Ferlay J

and Clifford GM: Global burden of cancer attributable to infections

in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob Health.

8:e180–e90. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Marques HP, Gomes da Silva S, De Martin E,

Agopian VG and Martins PN: Emerging biomarkers in HCC patients:

Current status. Int J Surg. 82S:70–76. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R

and Saborowski A: Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 400:1345–1362.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Luo Y, Ma J and Lu W: The significance of

mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 21:55982020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu BH, Xu CZ, Liu Y, Lu ZL, Fu TL, Li GR,

Deng Y, Luo GQ, Ding S, Li N and Geng Q: Mitochondrial quality

control in human health and disease. Mil Med Res.

11:322024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Swaih AM, Breda C, Sathyasaikumar KV,

Allcock N, Collier MEW, Mason RP, Feasby A, Herrera F, Outeiro TF,

Schwarcz R, et al: Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase interacts with

huntingtin at the outer mitochondrial membrane. Biomedicines.

10:22942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Uemura T and Hirai K: L-kynurenine

3-monooxygenase from mitochondrial outer membrane of pig liver:

Purification, some properties and monoclonal antibodies directed to

the enzyme. J Biochem. 123:253–262. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Maddison DC, Alfonso-Nunez M, Swaih AM,

Breda C, Campesan S, Allcock N, Straatman-Iwanowska A, Kyriacou CP

and Giorgini F: A novel role for kynurenine 3-monooxygenase in

mitochondrial dynamics. PLoS Genet. 16:e10091292020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen W, Zhao H and Li Y: Mitochondrial

dynamics in health and disease: Mechanisms and potential targets.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 8:3332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Huang TT, Tseng LM, Chen JL, Chu PY, Lee

CH, Huang CT, Wang WL, Lau KY, Tseng MF, Chang YY, et al:

Kynurenine 3-monooxygenase upregulates pluripotent genes through

β-catenin and promotes triple-negative breast cancer progression.

EBioMedicine. 54:1027172020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Liu CY, Huang TT, Chen JL, Chu PY, Lee CH,

Lee HC, Lee YH, Chang YY, Yang SH, Jiang JK, et al: Significance of

kynurenine 3-monooxygenase expression in colorectal cancer. Front

Oncol. 11:6203612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hornigold N, Dunn KR, Craven RA, Zougman

A, Trainor S, Shreeve R, Brown J, Sewell H, Shires M, Knowles M, et

al: Dysregulation at multiple points of the kynurenine pathway is a

ubiquitous feature of renal cancer: Implications for tumour immune

evasion. Br J Cancer. 123:137–147. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liang H, Cheung LW, Li J, Ju Z, Yu S,

Stemke-Hale K, Dogruluk T, Lu Y, Liu X, Gu C, et al: Whole-exome

sequencing combined with functional genomics reveals novel

candidate driver cancer genes in endometrial cancer. Genome Res.

22:2120–2129. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen N, Zong Y, Yang C, Li L, Yi Y, Zhao

J, Zhao X, Xie X, Sun X, Li N and Jiang L: KMO-driven metabolic

reconfiguration and its impact on immune cell infiltration in

nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A new avenue for immunotherapy. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 74:752025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Park SY and Nam JS: Kynurenine pathway

enzyme KMO in cancer progression: A tip of the Iceberg.

EBioMedicine. 55:1027622020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yan J, Chen D, Ye Z, Zhu X, Li X, Jiao H,

Duan M, Zhang C, Cheng J, Xu L, et al: Molecular mechanisms and

therapeutic significance of tryptophan metabolism and signaling in

cancer. Mol Cancer. 23:2412024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jin H, Zhang Y, You H, Tao X, Wang C, Jin

G, Wang N, Ruan H, Gu D, Huo X, et al: Prognostic significance of

kynurenine 3-monooxygenase and effects on proliferation, migration

and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep.

5:104662015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Shi Z, Gan G, Gao X, Chen F and Mi J:

Kynurenine catabolic enzyme KMO regulates HCC growth. Clin Transl

Med. 12:e6972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tang D, Chen M, Huang X, Zhang G, Zeng L,

Zhang G, Wu S and Wang Y: SRplot: A free online platform for data

visualization and graphing. PLoS One. 18:e02942362023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wu J, Ru NY, Zhang Y, Li Y, Wei D, Ren Z,

Huang XF, Chen ZN and Bian H: HAb18G/CD147 promotes

epithelial-mesenchymal transition through TGF-β signaling and is

transcriptionally regulated by Slug. Oncogene. 30:4410–4427. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Shi Z, Gan G, Xu X, Zhang J, Yuan Y, Bi B,

Gao X, Xu P, Zeng W, Li J, et al: Kynurenine derivative 3-HAA is an

agonist ligand for transcription factor YY1. J Hematol Oncol.

14:1532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kong Q, Liang Q, Tan Y, Luo X, Ling Y, Li

X, Cai Y and Chen H: Induction of ferroptosis by SIRT1 knockdown

alleviates cytarabine resistance in acute myeloid leukemia by

activating the HMGB1/ACSL4 pathway. Int J Oncol. 66:22025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhang X, Wu H, Niu J, Hu Y, Zhang W, Chang

J, Li L, Zhu J, Zhang C and Liu M: A novel mitochondria-related

gene signature in esophageal carcinoma: Prognostic, immune and

therapeutic features. Funct Integr Genomics. 23:1092023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Trezeguet V, Fatrouni H and Merched AJ:

Immuno-metabolic modulation of liver oncogenesis by the tryptophan

metabolism. Cells. 10:34692021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fiore A and Murray PJ: Tryptophan and

indole metabolism in immune regulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 70:7–14.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Cervenka I, Agudelo LZ and Ruas JL:

Kynurenines: Tryptophan's metabolites in exercise, inflammation and

mental health. Science. 357:eaaf97942017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Krishnamurthy S, Gilot D, Ahn SB, Lam V,

Shin JS, Guillemin GJ and Heng B: Involvement of kynurenine pathway

in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 13:51802021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lai Q, Wu L, Dong S, Zhu X, Fan Z, Kou J,

Liu F, Yu B and Li F: Inhibition of KMO ameliorates myocardial

ischemia injury via maintaining mitochondrial fusion and fission

balance. Int J Biol Sci. 19:3077–3098. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Chen B, Xie K, Zhang J, Yang L, Zhou H,

Zhang L and Peng R: Comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial

dysfunction and necroptosis in intracranial aneurysms from the

perspective of predictive, preventative and personalized medicine.

Apoptosis. 28:1452–1468. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang Y, Bai Y, Cai Y, Zhang Y, Shen L, Xi

W, Zhou Z, Xu L, Liu X, Han B and Yao H: Circular RNA SCMH1

suppresses KMO expression to inhibit mitophagy and promote

functional recovery following stroke. Theranostics. 14:7292–7308.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu ZQ, Ciudad MT and McGaha TL: New

insights into tryptophan metabolism in cancer. Trends Cancer.

11:629–641. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Xue C, Gu X, Zheng Q, Shi Q, Yuan X, Chu

Q, Jia J, Su Y, Bao Z, Lu J and Li L: Effects of 3-HAA on HCC by

regulating the heterogeneous macrophages-A scRNA-Seq analysis. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 10:e22070742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gan G, Shi Z, Shangguan C, Zhang J, Yuan

Y, Chen L, Liu W, Li B, Meng S, Xiong W and Mi J: The kynurenine

derivative 3-HAA sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib

by upregulating phosphatases. Theranostics. 11:6006–6018. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Gan G, Shi Z, Liu D, Zhang S, Zhu H, Wang

Y and Mi J: 3-hydroxyanthranic acid increases the sensitivity of

hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib by decreasing tumor cell

stemness. Cell Death Discov. 7:1732021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pan X, Wang W, Wang Y, Gu J and Ma X: M2

macrophage-secreted KYNU promotes stemness remodeling and malignant

behavior in endometrial cancer via the SOD2-mtROS-ERO1alpha-UPR(ER)

axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 44:1932025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ruan Q, Peng Y, Yi X, Yang J, Ai Q, Liu X,

He Y and Shi Y: The tryptophan metabolite 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid

alleviates hyperoxia-induced bronchopulmonary dysplasia via

inhibiting ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 82:1035792025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lee SO, Li X, Khan S and Safe S: Targeting

NR4A1 (TR3) in cancer cells and tumors. Expert Opin Ther Targets.

15:195–206. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Wang Y, Li N, Guan W and Wang D:

Controversy and multiple roles of the solitary nucleus receptor

Nur77 in disease and physiology. FASEB J. 39:e704682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chen QT, Zhang ZY, Huang QL, Chen HZ, Hong

WB, Lin T, Zhao WX, Wang XM, Ju CY, Wu LZ, et al: HK1 from hepatic

stellate cell-derived extracellular vesicles promotes progression

of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Metab. 4:1306–1321. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bian XL, Chen HZ, Yang PB, Li YP, Zhang

FN, Zhang JY, Wang WJ, Zhao WX, Zhang S, Chen QT, et al: Nur77

suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma via switching glucose

metabolism toward gluconeogenesis through attenuating

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase sumoylation. Nat Commun.

8:144202017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yang H, Nie Y, Li Y and Wan YJ: ERK1/2

deactivation enhances cytoplasmic Nur77 expression level and

improves the apoptotic effect of fenretinide in human liver cancer

cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 81:910–916. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Fu R, Ling D, Zhang Q, Jiang A and Pang H:

Harnessing Nur77's mitochondrial apoptotic pathway: A promising

therapeutic strategy for targeted disease intervention. Biomed

Pharmacother. 187:1180912025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ye H, Lin J, Zhang H, Wang J, Fu Y, Zeng

Z, Zheng J, Tao J and Qiu J: Nuclear receptor 4A1 regulates

mitochondrial homeostasis in cardiac post-ischemic injury by

controlling mitochondrial fission 1 protein-mediated fragmentation

and parkin-dependent mitophagy. Int J Biol Sci. 21:400–414. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Koenis DS, Evers-van Gogh IJA, van Loenen

PB, Zwart W, Kalkhoven E and de Vries CJM: Nuclear receptor Nur77

and Yin-Yang 1 synergistically increase mitochondrial abundance and

activity in macrophages. FEBS Lett. 598:1715–1729. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|