Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable hematologic

malignancy characterized by clonal expansion and accumulation of

plasma cells in the bone marrow (1,2).

It is associated with the production of abnormal antibodies,

referred to as monoclonal proteins or M proteins (3). Also known as plasma cell myeloma or

simply myeloma, MM accounts for ~1% of all types of cancer and 15%

of hematologic malignancies, with an incidence that increases with

age and is higher in men than in women (4-7).

Despite remarkable progress in its treatment, MM remains largely

incurable, posing significant challenges because of its complex

pathogenesis, frequent diagnostic delays caused by nonspecific

symptoms and the almost inevitable development of treatment

resistance (8,9).

The treatment paradigm for MM has undergone a

profound transformation, moving from conventional chemotherapy to a

multi-agent, mechanism-based approach. Foundational regimens

combining proteasome inhibitors (such as bortezomib and

carfilzomib), immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs; such as lenalidomide

and pomalidomide) and corticosteroids formed the first major wave

of therapeutic progress (10-17). More recently, immunotherapies,

including monoclonal antibodies (such as daratumumab targeting

CD38) and T-cell redirecting agents such as bispecific antibodies

and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy have further

improved patient outcomes (18-21). Despite these advances, relapse and

drug resistance remains a nearly universal challenge, highlighting

the remarkable adaptability of MM cells and the urgent need for

strategies that target the molecular basis of resistance (22-24).

These challenges are further compounded by the

disease's complexity. Diagnosis is often delayed because of

nonspecific initial symptoms (such as fatigue, bone pain and

anemia) (4,25-27) and its pathogenesis involves a

multifaceted interplay of genetic, epigenetic and bone marrow

microenvironment factors that promote myeloma cell survival and

drug resistance (1,4,28-30). The incomplete understanding of

these resistance mechanisms limits the development of curative

therapies for relapsed/refractory MM (18,20,31-33). Therefore, gaining deeper insights

into MM biology from new perspectives is critical for improving

patient outcomes.

Epitranscriptomics, the study of

post-transcriptional RNA modifications, has emerged as a crucial

layer of gene regulation (34-36). More than 170 chemical

modifications have been identified and these alterations profoundly

influence RNA metabolism, including stability, splicing and

translation (37,38). Among them, N6-methyladenosine

(m6A), the most abundant internal mRNA modification, has

garnered significant attention for its roles in normal biology and

cancer pathogenesis (39,40). Growing evidence implicates

dysregulated m6A modification in solid tumors and

hematological malignancies, including MM, where it influences

disease pathogenesis, therapeutic response and drug resistance

(41-43).

Eligible records included original research

articles, preclinical studies and clinical or translational reports

that examined i) m6A regulators or

m6A-dependent mechanisms in MM models or patient

samples, or ii) pharmacological or genetic modulation of

m6A pathways with potential therapeutic relevance.

Studies from other malignancies were included selectively when they

provided key mechanistic insight or information on inhibitor

development/chemical tractability and such evidence is explicitly

identified as non-MM where discussed. Studies were excluded if they

were i) published in non-English languages, ii) conference

abstracts without accompanying full-text primary data, iii)

retracted publications, or iv) not directly relevant to the core

focus on RNA modification biology in MM.

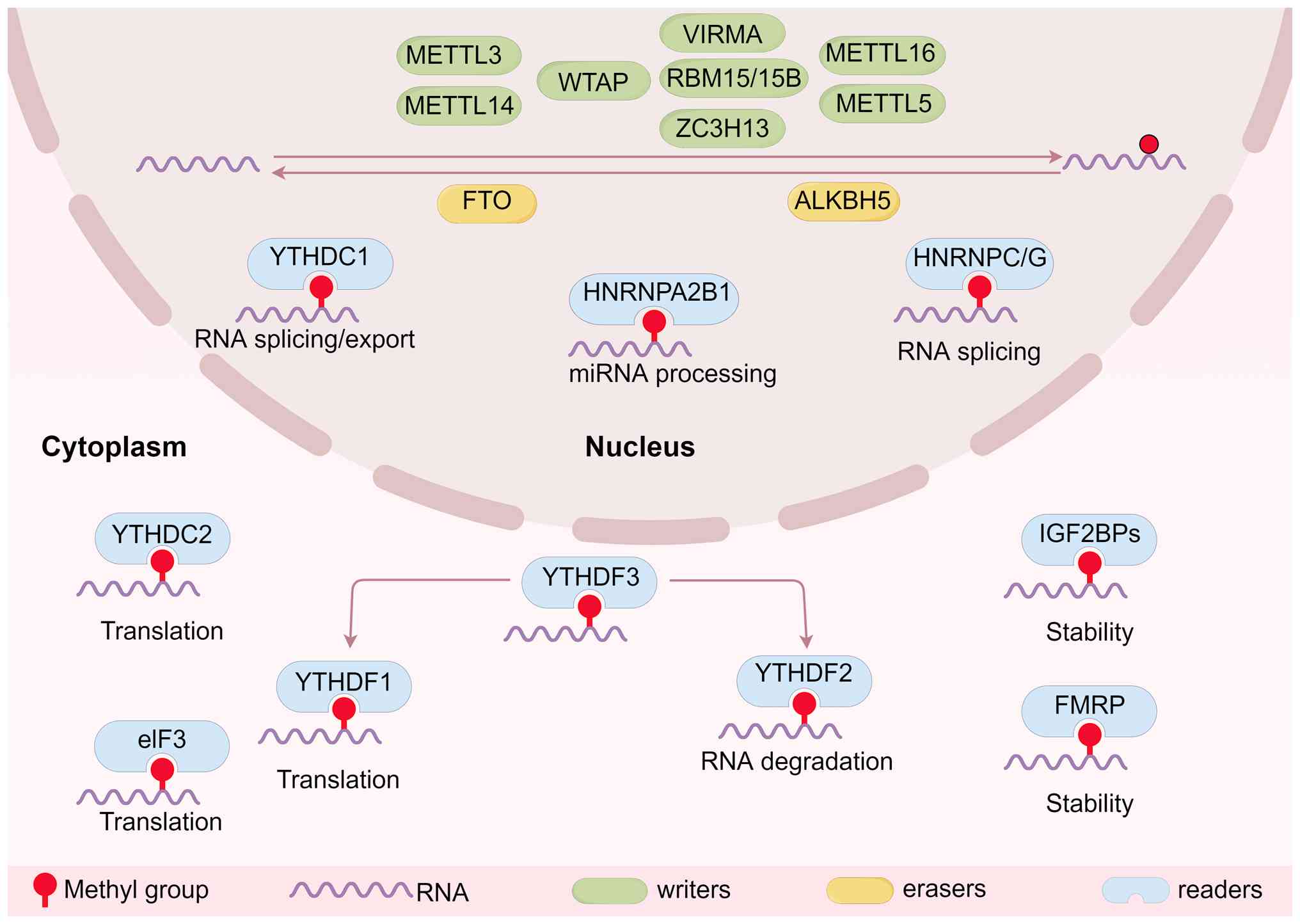

Traditionally, epigenetic regulation has focused on

DNA methylation and histone modifications as key determinants of

gene expression (44-46). The emergence of epitranscriptomics

has now revealed reversible chemical modifications on RNA as a

critical additional layer of gene regulation (47,48). Among known RNA modifications,

m6A is the most prevalent internal modification on

eukaryotic mRNA (49). The

presence of m6A on a transcript serves as a direct

binding platform for specific reader proteins, which markedly

influence the RNA's fate by regulating its splicing, stability,

export and translation (40,50,51). Another key mechanism of action

involves the ability of m6A to function as an

'm6A switch', in which the modification alters the RNA's

secondary structure to reveal binding sites for proteins that would

otherwise be inaccessible (52,53). This allows for rapid,

post-transcriptional fine-tuning of gene expression in response to

cellular signals, a process frequently dysregulated in cancer.

Additionally, heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs), such as heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein C/G (hnRNPC/G) and heterogeneous nuclear

ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (hnRNPA2B1), recognize m6A

modifications and influence miRNA processing and splicing events by

facilitating the recruitment of splicing factors and modulating

alternative splicing patterns (63,64). Eukaryotic initiation factor 3 can

bind to m6A sites, particularly near the 5' untranslated

region (UTR) of mRNAs, to directly promote translation initiation

in a cap-independent manner, enhancing the translation of specific

transcripts under certain conditions (65). Fragile X mental retardation

protein is another recognized m6A reader that plays a

role in neuronal mRNA localization and stability, thereby

influencing synaptic function and plasticity (66). This regulatory capacity of

m6A modification, which spans mRNA splicing,

localization, stability and translation efficiency, allows cells to

finely tune gene expression in response to developmental cues and

environmental stresses.

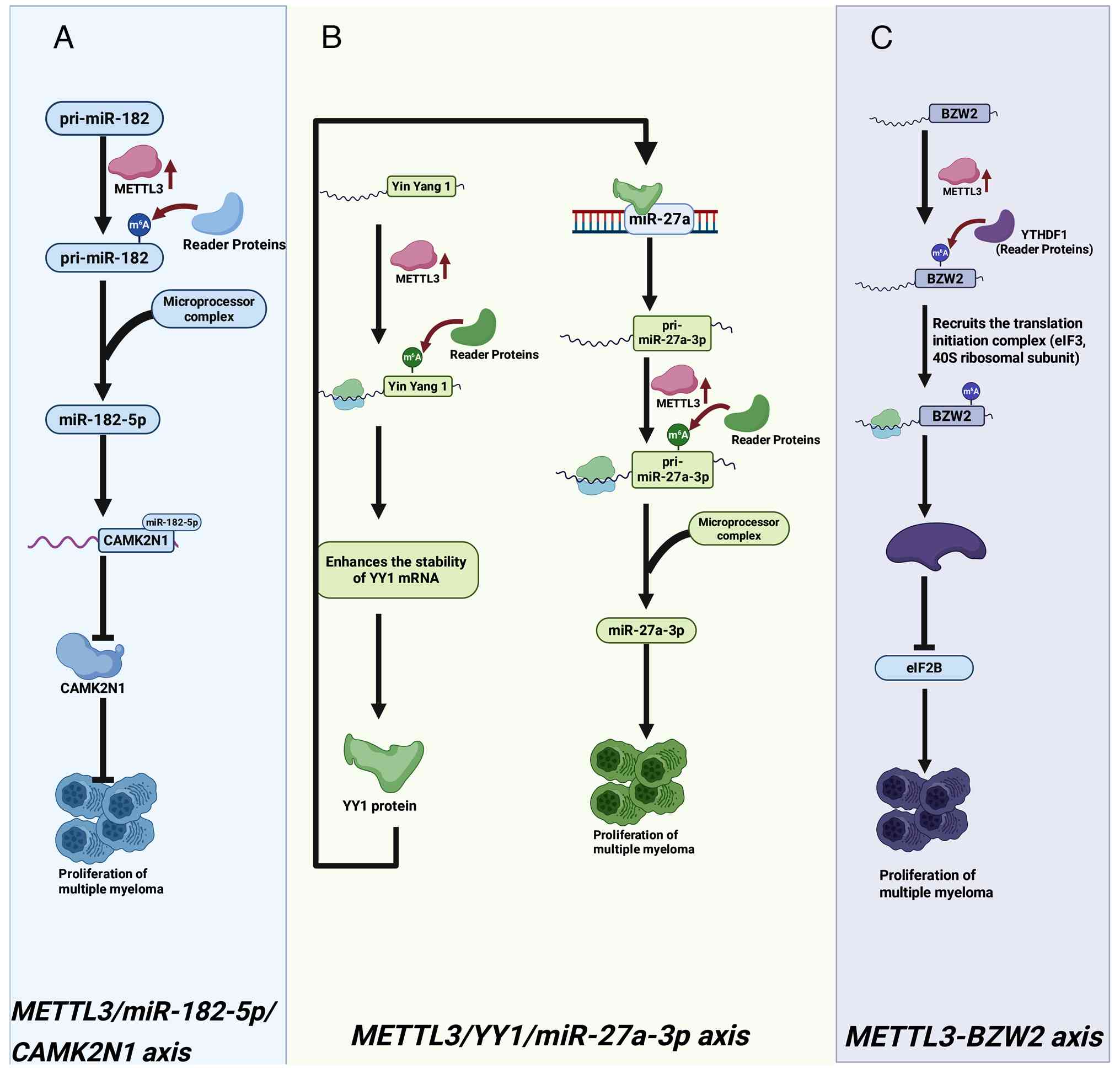

Other writers also contribute to MM pathogenesis in

pre-clinical contexts. For example, METTL5 has been shown to drive

MM progression by enhancing the translation of selenoproteins such

as selenophosphate synthetase 2 (SEPHS2), which is critical

for mitigating oxidative stress (121). The accessory writer protein

VIRMA (KIAA1429) is overexpressed in MM and experimental evidence

suggests it promotes tumorigenesis by enhancing m6A

modification and expression of the oncogene forkhead box M1

(FOXM1) via the reader YTHDF1 (122). Beyond regulating oncogene

expression, VIRMA has been linked to suppression of ferroptosis to

promote MM cell survival (123).

Mechanistically, VIRMA is stabilized by the lncRNA FEZF1-AS1

and, in turn, enhances m6A-dependent translation of OTU

deubiquitinase, ubiquitin aldehyde binding 1 (OTUB1). OTUB1

then deubiquitinates and stabilizes the ferroptosis defense protein

solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), protecting MM cells.

The core writer complex component WTAP also appears to function as

a critical oncogene. A recent study identified WTAP as

overexpressed in MM patients and associated with poor survival

(124). Mechanistically, this

study reported that WTAP installs m6A modifications on

microtubule-associated protein 6 domain containing 1 mRNA, thereby

regulating the Hippo signaling pathway to drive MM cell

proliferation. Notably, the writer complex can be regulated

post-translationally; research indicates protein arginine

methyltransferase 1 methylates and stabilizes WTAP, which in turn

enhances m6A modification of NADH:ubiquinone

oxidoreductase core subunit S6 mRNA, boosting its expression and

activating oxidative phosphorylation to promote tumorigenesis

(125).

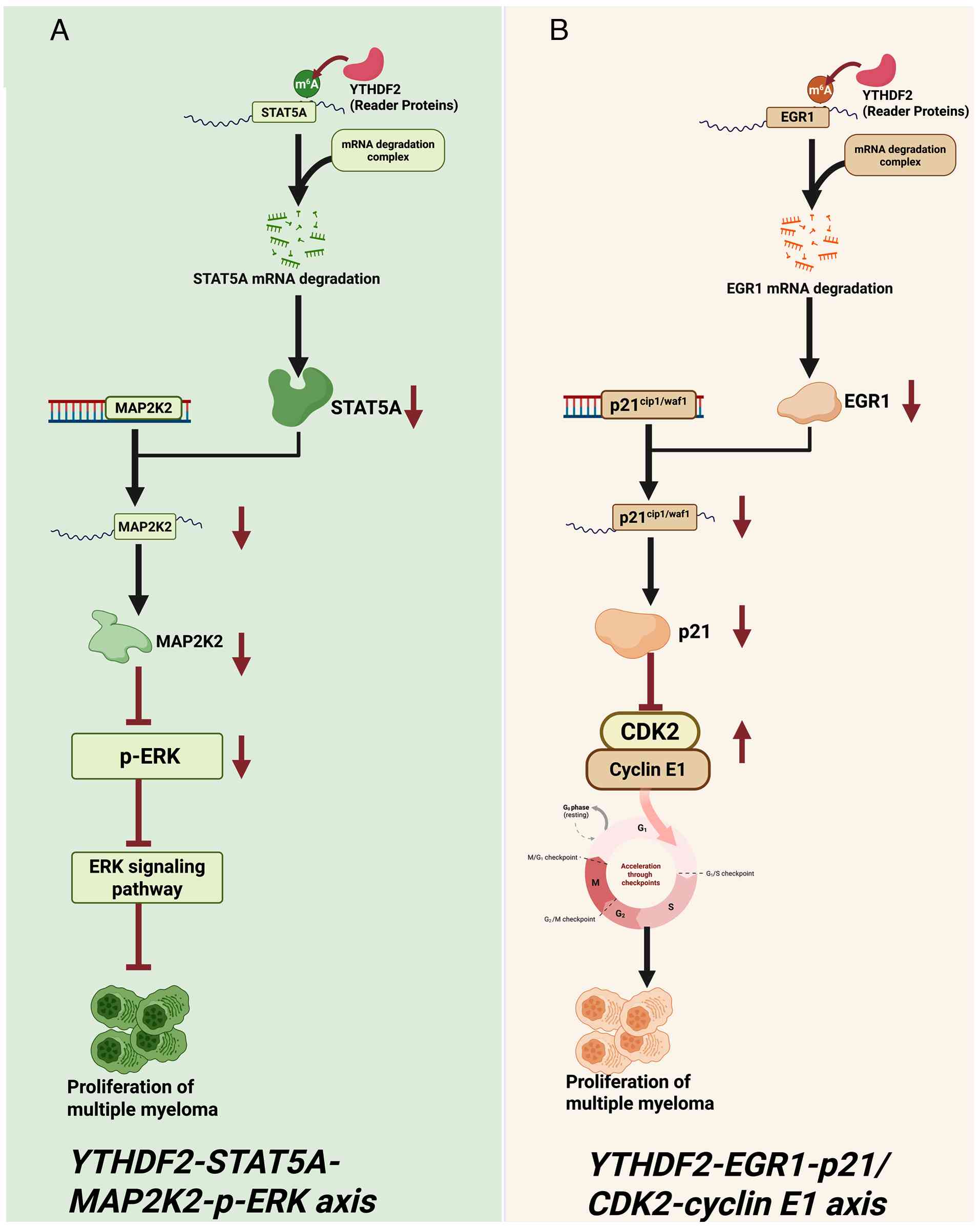

The oncogenic role of readers extends to

genetically defined MM subgroups. IGF2BP1 is markedly overexpressed

in patients with chromosome 1q gain, where it predicts an inferior

clinical outcome (128).

Mechanistically, IGF2BP1 directly binds to m6A sites

within the cell division cycle 5-Like (CDC5L) mRNA,

enhancing its stability and translation. The functional dependency

of this axis was confirmed by the fact that genetic or

pharmacological inhibition of IGF2BP1 suppressed the pro-tumor

effects, revealing the IGF2BP1-CDC5L axis as a vulnerability in

this high-risk population (128).

The other major eraser, FTO, exerts its oncogenic

role by establishing a hypomethylated transcriptome (138). FTO is upregulated in MM and

promotes tumor growth and metastasis. It specifically demethylates

heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) mRNA, shielding it from

YTHDF2-mediated decay and thus augmenting the heat shock response,

a critical survival pathway under proteotoxic stress (139). Importantly, FTO activity is

metabolically coupled. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2), which

generates the essential FTO cofactor α-ketoglutarate, is highly

expressed in progressive MM. IDH2 depletion increased global

m6A levels and impaired growth, mechanistically through

suppressing FTO-mediated hypomethylation and stabilization of Wnt

family member 7B mRNA, which activates pro-tumorigenic Wnt

signaling (140,141). The translational promise of

targeting m6A erasers is underscored by the finding that

FTO inhibition synergizes with the frontline therapeutic drug

bortezomib to suppress myeloma growth in vivo, presenting a

compelling combinatorial strategy (139).

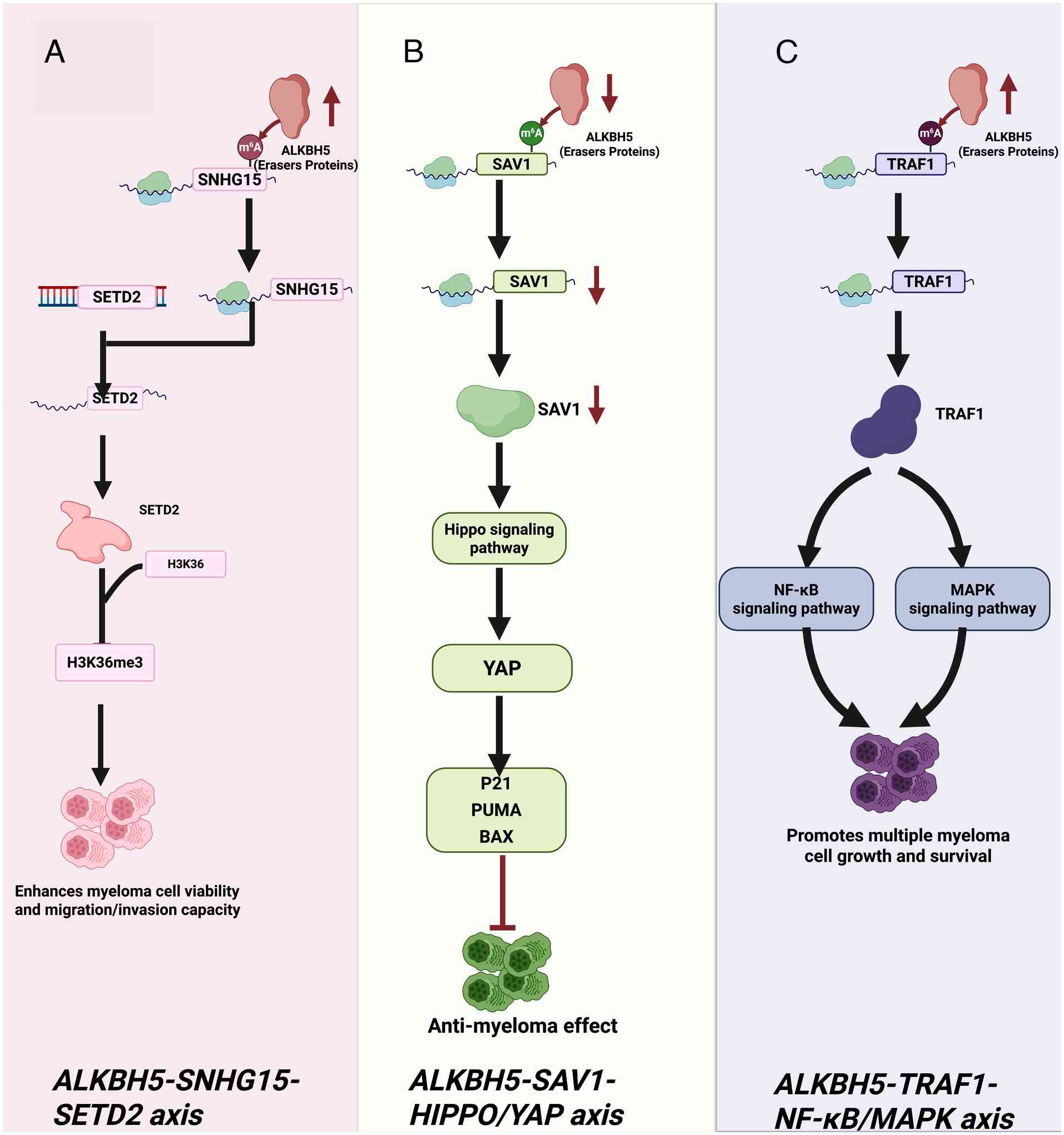

Taken together, the ALKBH5-SNHG15-SETD2,

ALKBH5-SAV1-YAP and ALKBH5-TRAF1 axes, along with FTO-mediated

regulation of HSF1 and Wnt signaling, represent important emerging

mechanistic insights. However, the current evidence for these

oncogenic roles of m6A erasers is predominantly derived

from in vitro and mouse xenograft models. Their overarching

significance, interdependence and clinical relevance as therapeutic

targets in primary MM require independent replication and further

validation in patient cohorts.

Collectively, these findings from recent

pre-clinical and bioinformatic studies illuminate an expanding

epitranscriptomic network in MM. While m6A remains the

most extensively characterized, the reported contributions of

ac4C and m5C underscore the broader

regulatory potential of RNA modifications. Targeting these pathways

represents a promising but early-stage frontier for developing

novel therapeutic strategies aimed at overcoming drug resistance

and improving patient outcomes.

The development of treatment resistance, a major

driver of relapse and mortality in MM, is thought to be closely

linked to dynamic adaptations in the epitranscriptome, particularly

m6A modification, which may coordinate both

cell-intrinsic survival pathways and extrinsic communication with

the bone marrow niche (147-150). Beyond directly regulating

oncogenic transcripts, m6A-mediated mechanisms are

implicated in drug resistance by reshaping the chromatin landscape

through crosstalk with other epigenetic modifiers and by modulating

the expression of drug efflux pumps and metabolic enzymes, thereby

reducing intracellular drug exposure and therapeutic efficacy

(83,151-153). A comprehensive dissection of

these epitranscriptomic pathways is therefore a current research

priority to develop strategies to overcome resistance and prevent

disease progression.

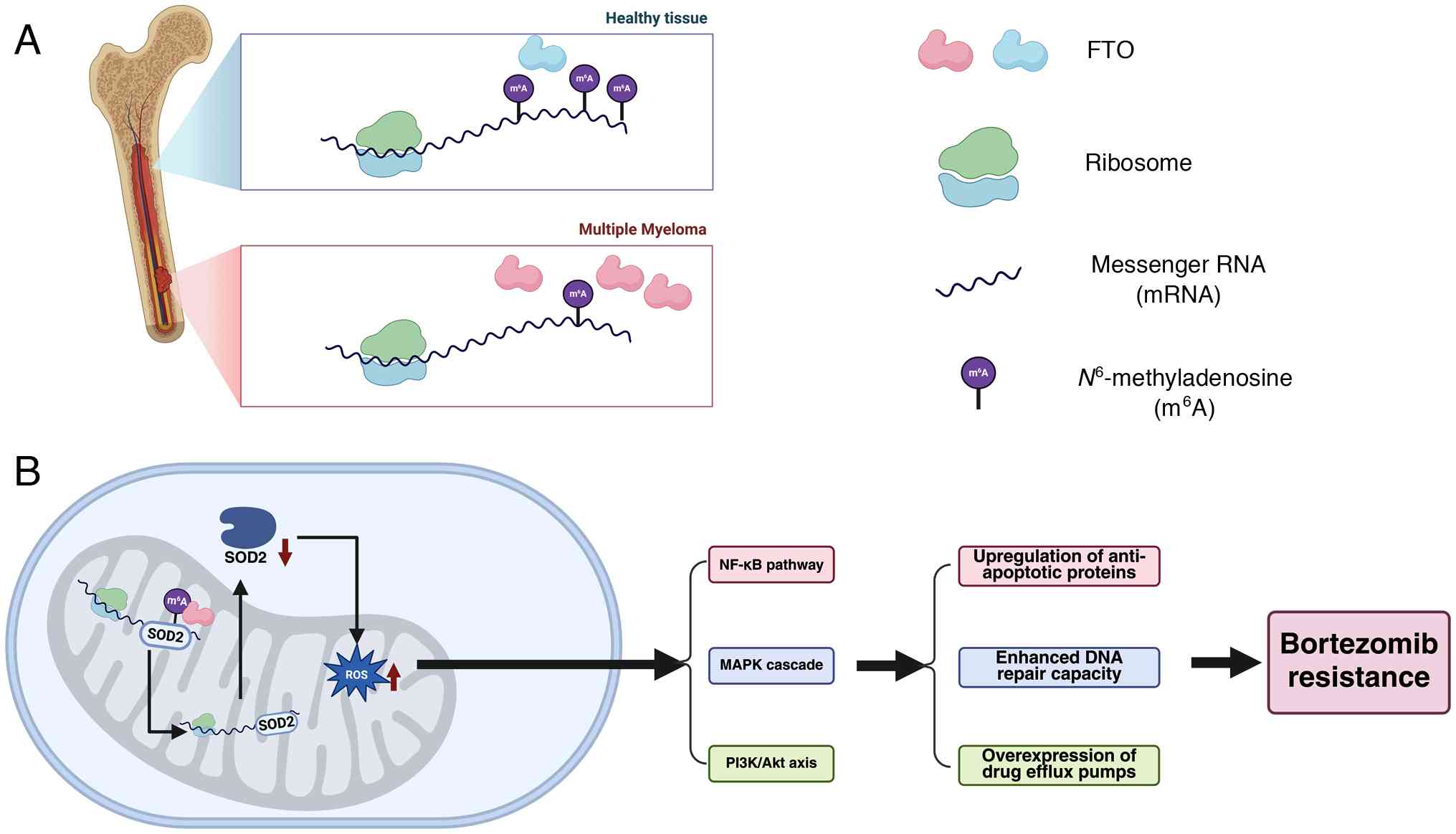

Notably, the regulation of oxidative stress in MM

reveals a complex picture. On one hand, METTL5 upregulates SEPHS2

expression, thereby enhances antioxidant defense (121). By contrast, FTO reduces SOD2

expression, diminishing antioxidant defense yet being reported to

contribute to bortezomib resistance (155). This paradox may be explained by

the dual role of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which at optimal

levels can drive pro-tumorigenic signaling (161,162). Thus, cancer cells may manipulate

different antioxidant pathways to maintain ROS within a

survival-favorable range. Future studies are warranted to validate

this effect and to determine how redox homeostasis can be

therapeutically targeted (163,164).

ALKBH5 has also been implicated in resistance to

targeted therapies. A recent study demonstrated that ALKBH5

overexpression attenuates the efficacy of the histone deacetylase

inhibitor romidepsin by reducing m6A methylation on

FOXM1 mRNA, thereby stabilizing it (165). Conversely, romidepsin treatment

or ALKBH5 knockout increases FOXM1 m6A

modification, accelerating its decay and synergistically enhancing

apoptosis (165). This positions

ALKBH5 as a key modulator of drug response in pre-clinical

models.

This concept extends to predicting response to

combination therapies. In a cohort of patients relapsing after

bortezomib-based regimens, a high m6A risk score (with

an Area Under the Curve of 0.9) was associated with non-response to

salvage therapy with daratumumab, carfilzomib, lenalidomide and

dexamethasone (DARA-KRD) (113).

Although mechanisms such as FTO-SOD2 have been demonstrated to

mediate resistance in preclinical models, these findings are

primarily based on single studies or limited cohorts. The

prevalence of these pathways in patient populations, particularly

among those with different types of resistance and their

interactions with classical resistance mechanisms remain

insufficiently elucidated and warrant validation in large-scale,

prospective clinical cohorts.

The bone marrow adipocyte niche has emerged as a

proposed source of exosome-mediated transfer of chemoresistance, a

process suggested to be governed by epitranscriptomic regulation.

Adipocyte-derived exosomes are reported to enrich MM cells with the

lncRNAs LOC606724 and SNHG1, which inhibit apoptosis

(171). Furthermore, the

methyltransferase METTL7A, whose activity is potentiated by EZH2 in

these models, promotes the m6A modification of these

lncRNAs, thereby enhancing their packaging into exosomes. Upon

delivery to MM cells, these m6A-modified lncRNAs drive

c-Myc expression (171).

This paradigm highlights a potential mechanism of niche-induced

drug resistance that warrants further investigation.

FTO is another high-priority target. MM-specific

evidence shows that FTO is upregulated in patients and promotes

bortezomib resistance through mechanisms including the disruption

of the oxidative stress modulator SOD2 (Fig. 5) (155). The chemical tractability of FTO

is supported by several inhibitors (such as FB23-2, CS1/CS2), which

have demonstrated anti-tumor effects in leukemia models (173,176-178). The potential for integration is

highly compelling. Synthetic small-molecule inhibitors like FB23-2

can selectively block FTO activity, leading to enhanced decay of

oncogenic transcripts such as MYC. Accordingly, FTO inhibition

warrants MM-specific validation as a resensitization strategy,

including testing in acquired bortezomib-resistant models and in

combination regimens with proteasome inhibitors.

The eraser ALKBH5 also presents a viable target.

Its MM-specific validation is underscored by its role in driving

tumorigenesis and mediating resistance to agents such as the

histone deacetylase inhibitor romidepsin by stabilizing FOXM1 mRNA

(165). However, available

ALKBH5 inhibitors (such as IOX1) are generally considered tool

compounds and improved potency/selectivity and MM-specific

pharmacological validation will be required. Modulating ALKBH5 may

still be attractive for combination strategies if on-target

activity and tolerability can be established (194).

Collectively, the inhibitors for METTL3 and FTO

possess the strongest immediate translational rationale. However,

it is critical to note that the current assessment of their

efficacy largely draws on research from other hematologic

malignancies such as AML. Specific pharmacodynamic data in MM,

optimal combination regimens and potential resistance mechanisms

await elucidation through future systematic preclinical studies

dedicated to MM.

Beyond small molecules, genetic and targeted

protein degradation technologies offer alternative paths for

precise and potent modulation of the m6A machinery

(Table II) (199-209). CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of

METTL3 or ALKBH5 has proven effective in impairing cancer

progression in various models, though in vivo delivery to MM

cells in the bone marrow remains a challenge (194,210). More sophisticated epigenetic

editing tools, such as dCas13b-ALKBH5 fusion systems, enable

site-specific m6A demethylation without altering the DNA

sequence, offering the potential to reversibly silence specific

driver genes such as IRF4 while sparing normal hematopoiesis

(208,211).

Proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represent

a groundbreaking modality to achieve complete and selective

degradation of target proteins. PROTACs such as WD6305, which

recruit E3 ubiquitin ligases to degrade METTL3, have demonstrated

potent anti-leukemic effects in vivo (199,212,213). This strategy could be

particularly effective against MM cells that rely on METTL3 for

survival, potentially overcoming resistance mechanisms that arise

with catalytic inhibitors. Similarly, antisense oligonucleotides

(ASOs) designed to silence METTL3 mRNA expression provide

high specificity and could mitigate off-target effects associated

with small molecules (214).

These next-generation approaches are poised to

address the issues of tumor heterogeneity and acquired resistance

that often plague conventional therapies. The future clinical

application of these modalities will hinge on overcoming the

critical challenge of delivery, efficiently and specifically

targeting MM cells within the bone marrow niche. Advances in lipid

nanoparticles, viral vectors, or cell-specific targeting moieties

will be essential to unlock the full potential of genetic and

degradation-based epitranscriptomic therapy for MM.

Notably, for targets such as ALKBH5 and YTHDF2, the

rationale for targeted therapies primarily relies on genetic

approaches (such as knockdown/knockout experiments) and the

efficacy of tool compounds in non-MM models. Conclusive evidence of

'chemical tractability', such as highly selective and potent lead

compounds, remains lacking in the context of MM. Furthermore,

direct single-cell epitranscriptomic mapping of m6A

marks (rather than regulator expression) in MM subtypes remains

limited, representing a key technical and conceptual gap.

The burgeoning field of epitranscriptomics has

fundamentally expanded our understanding of gene regulation in

cancer. The present review consolidated compelling evidence that

the m6A modification machinery is an active regulatory

layer linked to key aspects of MM pathogenesis, progression and

therapy resistance. Through the dysregulated activity of writers,

erasers and readers, m6A modifications fine-tune the

expression of oncogenic networks, remodel the bone marrow

microenvironment and confer resilience to current therapies,

positioning the epitranscriptome as a rich source of novel

prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic vulnerabilities.

Major gaps remain regarding heterogeneity and

clinical translation. MM is a heterogeneous disease characterized

by varying molecular subtypes [such as hyperdiploid, t(11;14) and t(4;14)]

(215,216), yet subtype-resolved

m6A mapping is still limited. Addressing this will

require advanced approaches such as single-cell profiling and

high-resolution mapping (217,218). In parallel, translation must

account for the essential roles of m6A regulators in

normal hematopoiesis and immunity, which raises the risk of

on-target toxicity and underscores the need for selective

inhibitors/degraders, biomarker-guided patient selection and dosing

or delivery strategies that maximize the therapeutic window.

Not applicable.

YM and MM performed study conception and design. YM

and SH wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. MM, DB, YG, NB

and WH reviewed and edited the manuscript. MM and WH conducted

proofreading and further revisions. YM contributed to the

acquisition of funds. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82460714), Natural

Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (grant no.

2024D01E17), Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Tianchi Talent

Introduction Plan ('TianChi Excellent Award for Young Doctoral

Talents'), the Xinjiang Medical University National Young Talent

Cultivation Program (grant no. XYD2024GR05) and the Undergraduate

Innovation Training Program of Xinjiang Medical University (project

no. X202410760050).

|

1

|

de Jong MME, Kellermayer Z, Papazian N,

Tahri S, Hofste Op Bruinink D, Hoogenboezem R, Sanders MA, van de

Woestijne PC, Bos PK, Khandanpour C, et al: The multiple myeloma

microenvironment is defined by an inflammatory stromal cell

landscape. Nat Immunol. 22:769–780. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ramberger E, Sapozhnikova V, Ng YLD,

Dolnik A, Ziehm M, Popp O, Sträng E, Kull M, Grünschläger F, Krüger

J, et al: The proteogenomic landscape of multiple myeloma reveals

insights into disease biology and therapeutic opportunities. Nat

Cancer. 5:1267–1284. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Guan L, Su W, Zhong J and Qiu L: M-protein

detection by mass spectrometry for minimal residual disease in

multiple myeloma. Clin Chim Acta. 552:1176232024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kumar SK, Rajkumar V, Kyle RA, van Duin M,

Sonneveld P, Mateos MV, Gay F and Anderson KC: Multiple myeloma.

Nat Rev Dis Prim. 3:170462017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mikhael J, Bhutani M and Cole CE: Multiple

myeloma for the primary care provider: A practical review to

promote earlier diagnosis among diverse populations. Am J Med.

136:33–41. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Rajkumar SV: Multiple myeloma: 2022 update

on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. Am J Hematol.

97:10862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Huang J, Chan SC, Lok V, Zhang L,

Lucero-Prisno DE III, Xu W, Zheng ZJ, Elcarte E, Withers M, Wong

MCS, et al: The epidemiological landscape of multiple myeloma: A

global cancer registry estimate of disease burden, risk factors,

and temporal trends. Lancet Haematol. 9:e670–e677. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Das S, Juliana N, Yazit NAA, Azmani S and

Abu IF: Multiple myeloma: Challenges encountered and future options

for better treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 23:16492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mohty M, Facon T, Malard F and Harousseau

JL: A roadmap towards improving outcomes in multiple myeloma. Blood

Cancer J. 14:1352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hu S, Xu J, Cui W, Jin H, Wang X and

Maimaitiyiming Y: Post-translational modifications in multiple

myeloma: Mechanisms of drug resistance and therapeutic

opportunities. Biomolecules. 15:7022025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rajkumar SV and Kumar S: Multiple myeloma

current treatment algorithms. Blood Cancer J. 10:942020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

12

|

Bhatt P, Kloock C and Comenzo R:

Relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: A review of available

therapies and clinical scenarios encountered in myeloma relapse.

Curr Oncol. 30:2322–2347. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zeng L, Huang H, Qirong C, Ruan C, Liu Y,

An W, Guo Q and Zhou J: Multiple myeloma patients undergoing

chemotherapy: Which symptom clusters impact quality of life? J Clin

Nurs. 32:7247–7259. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Goodman RS, Johnson DB and Balko JM:

Corticosteroids and cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res.

29:2580–2587. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Luo H, Feng Y, Wang F, Lin Z, Huang J, Li

Q, Wang X, Liu X, Zhai X, Gao Q, et al: Combinations of ivermectin

with proteasome inhibitors induce synergistic lethality in multiple

myeloma. Cancer Lett. 565:2162182023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Minařík J and Ševčíková S:

Immunomodulatory agents for multiple myeloma. Cancers (Basel).

14:57592022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Koniarczyk HL, Ferraro C and Miceli T:

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Semin

Oncol Nurs. 33:265–278. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dima D, Jiang D, Singh DJ, Hasipek M, Shah

HS, Ullah F, Khouri J, Maciejewski JP and Jha BK: Multiple myeloma

therapy: Emerging trends and challenges. Cancers (Basel).

14:40822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sheykhhasan M, Ahmadieh-Yazdi A,

Vicidomini R, Poondla N, Tanzadehpanah H, Dirbaziyan A, Mahaki H,

Manoochehri H, Kalhor N and Dama P: CAR T therapies in multiple

myeloma: Unleashing the future. Cancer Gene Ther. 31:667–686. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Neri P, Leblay N, Lee H, Gulla A, Bahlis

NJ and Anderson KC: Just scratching the surface: novel treatment

approaches for multiple myeloma targeting cell membrane proteins.

Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 21:590–609. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tam T, Smith E, Lozoya E, Heers H and

Andrew Allred P: Roadmap for new practitioners to navigate the

multiple myeloma landscape. Heliyon. 8:e105862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhu Y, Jian X, Chen S, An G, Jiang D, Yang

Q, Zhang J, Hu J, Qiu Y, Feng X, et al: Targeting gut microbial

nitrogen recycling and cellular uptake of ammonium to improve

bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma. Cell Metab.

36:159–175.e8. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Neri P, Barwick BG, Jung D, Patton JC,

Maity R, Tagoug I, Stein CK, Tilmont R, Leblay N, Ahn S, et al:

ETV4-Dependent transcriptional plasticity maintains MYC expression

and results in IMiD resistance in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer

Discov. 5:56–73. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

24

|

Zhang L, Peng X, Ma T, Liu J, Yi Z, Bai J,

Li Y, Li L and Zhang L: Natural killer cells affect the natural

course, drug resistance, and prognosis of multiple myeloma. Front

Cell Dev Biol. 12:13590842024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Malard F, Neri P, Bahlis NJ, Terpos E,

Moukalled N, Hungria VTM, Manier S and Mohty M: Multiple myeloma.

Nat Rev Dis Prim. 10:452024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Negrete-Rodríguez P, Gallardo-Pérez MM,

Lira-Lara O, Melgar-de-la-Paz M, Hamilton-Avilés LE, Ocaña-Ramm G,

Robles-Nasta M, Sánchez-Bonilla D, Olivares-Gazca JC, Mateos MV, et

al: Prevalence and consequences of a delayed diagnosis in multiple

myeloma: A single institution experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma

Leuk. 24:478–483. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yang P, Qu Y, Wang M, Chu B, Chen W, Zheng

Y, Niu T and Qian Z: Pathogenesis and treatment of multiple

myeloma. MedComm (2020). 3:e1462022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Dimopoulos K, Gimsing P and Grønbæk K: The

role of epigenetics in the biology of multiple myeloma. Blood

Cancer J. 4:e2072014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Song H, Feng X, Zhang H, Luo Y, Huang J,

Lin M, Jin J, Ding X, Wu S, Huang H, et al: METTL3 and ALKBH5

oppositely regulate m6A modification of TFEB mRNA, which dictates

the fate of hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated cardiomyocytes.

Autophagy. 15:1419–1437. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu R, Gao Q, Foltz SM, Fowles JS, Yao L,

Wang JT, Cao S, Sun H, Wendl MC, Sethuraman S, et al: Co-evolution

of tumor and immune cells during progression of multiple myeloma.

Nat Commun. 12:25592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Vo JN, Wu YM, Mishler J, Hall S, Mannan R,

Wang L, Ning Y, Zhou J, Hopkins AC, Estill JC, et al: The genetic

heterogeneity and drug resistance mechanisms of relapsed refractory

multiple myeloma. Nat Commun. 13:37502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Xu L, Wen C, Xia J, Zhang H, Liang Y and

Xu X: Targeted immunotherapy: Harnessing the immune system to

battle multiple myeloma. Cell Death Discov. 10:552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Skerget S, Penaherrera D, Chari A,

Jagannath S, Siegel DS, Vij R, Orloff G, Jakubowiak A, Niesvizky R,

Liles D, et al: Comprehensive molecular profiling of multiple

myeloma identifies refined copy number and expression subtypes. Nat

Genet. 56:1878–1889. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Rosselló-Tortella M, Ferrer G and Esteller

M: Epitranscriptomics in hematopoiesis and hematologic

malignancies. Blood Cancer Discov. 1:26–31. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Frye M, Jaffrey SR, Pan T, Rechavi G and

Suzuki T: RNA modifications: What have we learned and where are we

headed? Nat Rev Genet. 17:365–372. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yang C, Han H and Lin S: RNA

epitranscriptomics: A promising new avenue for cancer therapy. Mol

Ther. 30:2–3. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Yang L, Tang L, Min Q, Tian H, Li L, Zhao

Y, Wu X, Li M, Du F, Chen Y, et al: Emerging role of RNA

modification and long noncoding RNA interaction in cancer. Cancer

Gene Ther. 31:816–830. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pham CT, Rangan L and Schlenner S: RNA

modifications-a regulatory dimension yet to be deciphered in

immunity. Genes Immun. 24:281–282. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Xue C, Chu Q, Zheng Q, Jiang S, Bao Z, Su

Y, Lu J and Li L: Role of main RNA modifications in cancer:

N6-methyladenosine, 5-methylcytosine, and pseudouridine. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7:1422022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Deng X, Qing Y, Horne D, Huang H and Chen

J: The roles and implications of RNA m6A modification in cancer.

Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:507–526. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cui L, Ma R, Cai J, Guo C, Chen Z, Yao L,

Wang Y, Fan R, Wang X and Shi Y: RNA modifications: importance in

immune cell biology and related diseases. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 7:3342022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yao L, Yin H, Hong M, Wang Y, Yu T, Teng

Y, Li T and Wu Q: RNA methylation in hematological malignancies and

its interactions with other epigenetic modifications. Leukemia.

35:1243–1257. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Qing Y, Su R and Chen J: RNA modifications

in hematopoietic malignancies: A new research frontier. Blood.

138:637–648. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chao CT, Kuo FC and Lin SH: Epigenetically

regulated inflammation in vascular senescence and renal progression

of chronic kidney disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 154:305–315. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kan RL, Chen J and Sallam T: Crosstalk

between epitranscriptomic and epigenetic mechanisms in gene

regulation. Trends Genet. 38:182–193. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

46

|

Ye Z, Mayila M, Bu N, Hao W and

Maimaitiyiming Y: Epigenetic and epitranscriptomic landscape of

phthalate toxicity: Implications for human health and disease.

Environ Pollut. 391:1275592026. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M and He C: RNA

modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science.

361:1346–1349. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Qiu L, Jing Q, Li Y and Han J: RNA

modification: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Mol Biomed.

4:252023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Sun H, Li K, Liu C and Yi C: Regulation

and functions of non-m6A mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:714–731. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Martinez De La Cruz B, Darsinou M and

Riccio A: From form to function: m6A methylation links mRNA

structure to metabolism. Adv Biol Regul. 87:1009262023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Deng LJ, Deng WQ, Fan SR, Chen MF, Qi M,

Lyu WY, Qi Q, Tiwari AK, Chen JX, Zhang DM and Chen ZS: m6A

modification: Recent advances, anticancer targeted drug discovery

and beyond. Mol Cancer. 21:522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Su Y, Maimaitiyiming Y, Wang L, Cheng X

and Hsu CH: Modulation of phase separation by RNA: A glimpse on

N6-Methyladenosine modification. Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7864542021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Mendel M, Delaney K, Pandey RR, Chen KM,

Wenda JM, Vågbø CB, Steiner FA, Homolka D and Pillai RS: Splice

site m6A methylation prevents binding of U2AF35 to inhibit RNA

splicing. Cell. 184:3125–3142.e25. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Aufgebauer CJ, Bland KM and Horner SM:

Modifying the antiviral innate immune response by selective

writing, erasing, and reading of m6A on viral and cellular RNA.

Cell Chem Biol. 31:100–109. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lee SY, Kim JJ and Miller KM: Emerging

roles of RNA modifications in genome integrity. Brief Funct

Genomics. 20:106–112. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

56

|

Zaccara S, Ries RJ and Jaffrey SR:

Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 20:608–624. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Esteva-Socias M and Aguilo F: METTL3 as a

master regulator of translation in cancer: Mechanisms and

implications. NAR Cancer. 6:zcae0092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yan X, Liu F, Yan J, Hou M, Sun M, Zhang

D, Gong Z, Dong X, Tang C and Yin P: WTAP-VIRMA counteracts dsDNA

binding of the m(6)A writer METTL3-METTL14 complex and maintains

N(6)-adenosine methylation activity. Cell Discov. 9:1002023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yang Z, Zhang S, Xiong J, Xia T, Zhu R,

Miao M, Li K, Chen W, Zhang L, You Y and You B: The m6A

demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 aggravate the malignant progression of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma by coregulating ARHGAP35. Cell Death

Discov. 10:432024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Zou Z, Sepich-Poore C, Zhou X, Wei J and

He C: The mechanism underlying redundant functions of the YTHDF

proteins. Genome Biol. 24:172023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Xiao W, Adhikari S, Dahal U, Chen YS, Hao

YJ, Sun BF, Sun HY, Li A, Ping XL, Lai WY, et al: Nuclear m(6)A

Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 61:507–519. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Huang H, Weng H, Sun W, Qin X, Shi H, Wu

H, Zhao BS, Mesquita A, Liu C, Yuan CL, et al: Recognition of RNA N

6 -methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and

translation. Nat Cell Biol. 20:285–295. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Alarcón CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X,

Tavazoie S and Tavazoie SF: HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of

m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell. 162:1299–1308.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Xu W, Huang Z, Xiao Y, Li W, Xu M, Zhao Q

and Yi P: HNRNPC promotes estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer

cell cycle by stabilizing WDR77 mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner.

Mol Carcinog. 63:859–873. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Meyer KD, Patil DP, Zhou J, Zinoviev A,

Skabkin MA, Elemento O, Pestova TV, Qian SB and Jaffrey SR: 5' UTR

m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell. 163:999–1010. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Zhang F, Kang Y, Wang M, Li Y, Xu T, Yang

W, Song H, Wu H, Shu Q and Jin P: Fragile X mental retardation

protein modulates the stability of its m6A-marked messenger RNA

targets. Hum Mol Genet. 27:3936–3950. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Mao-Mao, Zhang JJ, Xu YP, Shao MM and Wang

MC: Regulatory effects of natural products on N6-methyladenosine

modification: A novel therapeutic strategy for cancer. Drug Discov

Today. 29:1038752024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Zhu ZM, Huo FC, Zhang J, Shan HJ and Pei

DS: Crosstalk between m6A modification and alternative splicing

during cancer progression. Clin Transl Med. 13:e14602023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Jain S, Koziej L, Poulis P, Kaczmarczyk I,

Gaik M, Rawski M, Ranjan N, Glatt S and Rodnina MV: Modulation of

translational decoding by m6A modification of mRNA. Nat Commun.

14:47842023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Qiao Y, Sun Q, Chen X, He L, Wang D, Su R,

Xue Y, Sun H and Wang H: Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 promotes muscle

stem cell activation/proliferation by regulating mRNA splicing and

nuclear export. Elife. 12:e827032023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Boulias K and Greer EL: Biological roles

of adenine methylation in RNA. Nat Rev Genet. 24:143–160. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wang Y, Li Y, Skuland T, Zhou C, Li A,

Hashim A, Jermstad I, Khan S, Dalen KT, Greggains GD, et al: The

RNA m6A landscape of mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Nat

Struct Mol Biol. 30:703–709. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Wen J, Lv R, Ma H, Shen H, He C, Wang J,

Jiao F, Liu H, Yang P, Tan L, et al: Zc3h13 regulates nuclear RNA

m6A methylation and mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Mol

Cell. 69:1028–1038.e6. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Yoon KJ, Ringeling FR, Vissers C, Jacob F,

Pokrass M, Jimenez-Cyrus D, Su Y, Kim NS, Zhu Y, Zheng L, et al:

Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m6A

methylation. Cell. 171:877–889.e17. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Wang L, Maimaitiyiming Y, Su K and Hsu CH:

RNA m6A Modification: The Mediator Between Cellular Stresses and

Biological Effects. RNA Technologies. 12:353–390. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Xiang Y, Laurent B, Hsu CH, Nachtergaele

S, Lu Z, Sheng W, Xu C, Chen H, Ouyang J, Wang S, et al: RNA m(6)A

methylation regulates the ultraviolet-induced DNA damage response.

Nature. 543:573–576. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Wang L, Zhan G, Maimaitiyiming Y, Su Y,

Lin S, Liu J, Su K, Lin J, Shen S, He W, et al: m6A modification

confers thermal vulnerability to HPV E7 oncotranscripts via reverse

regulation of its reader protein IGF2BP1 upon heat stress. Cell

Rep. 41:1115462022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Engel M, Eggert C, Kaplick PM, Eder M, Röh

S, Tietze L, Namendorf C, Arloth J, Weber P, Rex-Haffner M, et al:

The role of m6A/m-RNA methylation in stress response regulation.

Neuron. 99:389–403.e9. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Chuong NN, Doan PPT, Wang L, Kim JH and

Kim J: Current insights into m6A RNA methylation and its emerging

role in plant circadian clock. Plants (Basel). 12:6242023.

|

|

80

|

Yang Y, Fan X, Mao M, Song X, Wu P, Zhang

Y, Jin Y, Yang Y, Chen LL, Wang Y, et al: Extensive translation of

circular RNAs driven by N 6 -methyladenosine. Cell Res. 27:626–641.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Alarcón CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N

and Tavazoie SF: N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for

processing. Nature. 519:482–485. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Ma JZ, Yang F, Zhou CC, Liu F, Yuan JH,

Wang F, Wang TT, Xu QG, Zhou WP and Sun SH: METTL14 suppresses the

metastatic potential of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulating

N6-methyladenosine-dependent primary MicroRNA processing.

Hepatology. 65:529–543. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Deng S, Zhang J, Su J, Zuo Z, Zeng L, Liu

K, Zheng Y, Huang X, Bai R, Zhuang L, et al: RNA m6A regulates

transcription via DNA demethylation and chromatin accessibility.

Nat Genet. 54:1427–1437. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Höfler S and Duss O: Interconnections

between m6 A RNA modification, RNA structure, and protein-RNA

complex assembly. Life Sci Alliance. 7:e2023022402024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Vaid R, Thombare K, Mendez A,

Burgos-Panadero R, Djos A, Jachimowicz D, Lundberg KI, Bartenhagen

C, Kumar N, Tümmler C, et al: MET TL3 drives telomere targ eting of

TERRA lncRNA through m 6 A-dependent R-loop formation: A

therapeutic target for ALT-positive neuroblastoma. Nucleic Acids

Res. 52:2648–2671. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Lee SY, Lee SH, Kwak MJ, Kim JY, Perren

JO, Miller KM and Kim JJ: Depletion of BRD9-mediated R-loop

accumulation inhibits leukemia cell growth via

transcription-replication conflict. Nucleic Acids Res.

53:gkaf6132025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Verghese M, Wilkinson E and He YY: Role of

RNA modifications in carcinogenesis and carcinogen damage response.

Mol Carcinog. 62:24–37. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

88

|

Yang J, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Yu X and

Shi S: Epigenetic regulation in the tumor microenvironment:

Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 8:2102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Lin S and Kuang M: RNA

modification-mediated mRNA translation regulation in liver cancer:

Mechanisms and clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 21:267–281. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Dong L, Cao Y, Hou Y and Liu G:

N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation: A novel regulator of the

development and function of immune cells. J Cell Physiol.

237:329–345. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Delaunay S, Helm M and Frye M: RNA

modifications in physiology and disease: Towards clinical

applications. Nat Rev Genet. 25:104–122. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Berdasco M and Esteller M: Towards a

druggable epitranscriptome: Compounds that target RNA modifications

in cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 179:2868–2889. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Zheng J, Lu Y, Lin Y, Si S, Guo B, Zhao X

and Cui L: Epitranscriptomic modifications in mesenchymal stem cell

differentiation: Advances, mechanistic insights, and beyond. Cell

Death Differ. 31:9–27. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Delaunay S and Frye M: RNA modifications

regulating cell fate in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 21:552–559. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Shi J, Zhang Q, Yin X, Ye J, Gao S, Chen

C, Yang Y, Wu B, Fu Y, Zhang H, et al: Stabilization of IGF2BP1 by

USP10 promotes breast cancer metastasis via CPT1A in an

m6A-dependent manner. Int J Biol Sci. 19:449–464. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Lv D, Gimple RC, Zhong C, Zhong C, Wu Q,

Yang K, Prager BC, Godugu B, Qiu Z, Zhao L, et al: PDGF signaling

inhibits mitophagy in glioblastoma stem cells through

N6-methyladenosine. Dev Cell. 57:1466–1481.e6. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Feng Y, Yuan P, Guo H, Gu L, Yang Z, Wang

J, Zhu W, Zhang Q, Cao J, Wang L and Jiao Y: METTL3 mediates

epithelial-mesenchymal transition by modulating FOXO1 mRNA

N6-Methyladenosine-Dependent YTHDF2 Binding: A novel mechanism of

radiation-induced lung injury. Adv Sci (Weinh). 10:e22047842023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Geula S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S,

Dominissini D, Mansour AA, Kol N, Salmon-Divon M, Hershkovitz V,

Peer E, Mor N, Manor YS, et al: Stem Cells m6A mRNA methylation

facilitates resolution of naïve pluripotency toward

differentiation. Science. 347:1002–1006. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Chen Y, Peng C, Chen J, Chen D, Yang B, He

B, Hu W, Zhang Y, Liu H, Dai L, et al: WTAP facilitates progression

of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic

silencing of ETS1. Mol Cancer. 18:1272019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zhang S, Zhao BS, Zhou A, Lin K, Zheng S,

Lu Z, Chen Y, Sulman EP, Xie K, Bögler O, et al: m6A demethylase

ALKBH5 maintains tumorigenicity of glioblastoma stem-like cells by

sustaining FOXM1 expression and cell proliferation program. Cancer

Cell. 31:591–606.e6. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Xiao S, Ma S, Sun B, Pu W, Duan S, Han J,

Hong Y, Zhang J, Peng Y, He C, et al: The tumor-intrinsic role of

the m6A reader YTHDF2 in regulating immune evasion. Sci Immunol.

9:eadl21712024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han

D, Ma H, Weng X, Chen K, Shi H and He C: N6-methyladenosine

modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell.

161:1388–1399. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Zeng L, Huang X, Zhang J, Lin D and Zheng

J: Roles and implications of mRNA N6-methyladenosine in cancer.

Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:729–748. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Zhuang H, Yu B, Tao D, Xu X, Xu Y, Wang J,

Jiao Y and Wang L: The role of m6A methylation in therapy

resistance in cancer. Mol Cancer. 22:912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Jin Z, MacPherson K, Liu Z and Vu LP: RNA

modifications in hematological malignancies. Int J Hematol.

117:807–820. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Lv J, Zhang Y, Gao S, Zhang C, Chen Y, Li

W, Yang YG, Zhou Q and Liu F: Endothelial-specific m6A modulates

mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell development via Notch

signaling. Cell Res. 28:249–252. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Li Z, Weng H, Su R, Weng X, Zuo Z, Li C,

Huang H, Nachtergaele S, Dong L, Hu C, et al: FTO plays an

oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N6-Methyladenosine

RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. 31:127–141. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Vu LP, Pickering BF, Cheng Y, Zaccara S,

Nguyen D, Minuesa G, Chou T, Chow A, Saletore Y, MacKay M, et al:

The N 6 -methyl-adenosine (m 6 A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls

myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells.

Nat Med. 23:1369–1376. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, Shi

J, Millán-Zambrano G, Robson SC, Aspris D, Migliori V, Bannister

AJ, Han N, et al: Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia

by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature. 552:126–131. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Zhang N, Shen Y, Li H, Chen Y, Zhang P,

Lou S and Deng J: The m6A reader IGF2BP3 promotes acute myeloid

leukemia progression by enhancing RCC2 stability. Exp Mol Med.

54:194–205. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

111

|

Wilkinson E, Cui YH and He YY:

Context-dependent roles of RNA modifications in stress responses

and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 22:19492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Wang J, Zuo Y, Lv C, Zhou M and Wan Y:

N6-methyladenosine regulators are potential prognostic biomarkers

for multiple myeloma. IUBMB Life. 75:137–148. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

113

|

Deng Y, Zhu H and Peng H: Enhancing

staging in multiple myeloma using an m6A regulatory gene-pairing

model. Clin Exp Med. 25:402025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

114

|

Bao J, Xu T, Wang W, Xu H, Chen X and Xia

R: N6-methyladenosine-induced miR-182-5p promotes multiple myeloma

tumorigenesis by regulating CAMK2N1. Mol Cell Biochem.

479:3077–3089. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Che F, Ye X, Wang Y, Wang X, Ma S, Tan Y,

Mao Y and Luo Z: METTL3 facilitates multiple myeloma tumorigenesis

by enhancing YY1 stability and pri-microRNA-27 maturation in

m6A-dependent manner. Cell Biol Toxicol. 39:2033–2050. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Huang X, Yang Z, Li Y and Long X: m6A

methyltransferase METTL3 facilitates multiple myeloma cell growth

through the m6A modification of BZW2. Ann Hematol. 102:1801–1810.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Lu X, Li Y, Li R, Zhang J, Peng J and

Zhang Y: Regulatory role of the METTL3/MALAT1 axis in multiple

myeloma progression. J Bone Oncol. 53:1006952025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Zhao Y, Zhang E, Lv N, Ma L, Yao S, Yan M,

Zi F, Deng G, Liu X, He J, et al: Metformin and FTY720

synergistically induce apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 48:785–800. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Gao L, Li L, Hu J, Li G, Zhang Y, Dai X,

De Z and Xu F: Metformin inhibits multiple myeloma serum-induced

endothelial cell thrombosis by down-regulating miR-532. Ann Vasc

Surg. 85:347–357.e2. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Chen CJ, Huang JY, Huang JQ, Deng JY,

Shangguan XH, Chen AZ, Chen LT and Wu WH: Metformin attenuates

multiple myeloma cell proliferation and encourages apoptosis by

suppressing METTL3-mediated m6A methylation of THRAP3, RBM25, and

USP4. Cell Cycle. 22:986–1004. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Jiang J, Zhong F, Xiao Z, Yao F, Liu J, Li

M, Zeng H, Qiu Y, Zhang J, Zhang H, et al: METTL5 regulates

SEPHS2-mediated selenoprotein synthesis to promote multiple myeloma

survival and progression. Cell Death Dis. 16:5852025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Wu Y, Luo Y, Yao X, Shi X, Xu Z, Re J, Shi

M, Li M, Liu J, He Y and Du X: KIAA1429 increases FOXM1 expression

through YTHDF1-mediated m6A modification to promote aerobic

glycolysis and tumorigenesis in multiple myeloma. Cell Biol

Toxicol. 40:582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Su Q, Liu W, Wang P and Wang M: Long

non-coding RNA FEZF1-AS1 suppresses ferroptosis in multiple myeloma

cells through KIAA1429-mediated m6A modification. Hum Cell.

38:1782025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

124

|

Xu H, Xu M, Ding J and Bao J: WTAP

promotes the proliferation of multiple myeloma by regulating the

hippo pathway through m(6)A modification of MAP6D1. Leuk Lymphoma.

67:148–163. 2026. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Jia Y, Yu X, Liu R, Shi L, Jin H, Yang D,

Zhang X, Shen Y, Feng Y, Zhang P, et al: PRMT1 methylation of WTAP

promotes multiple myeloma tumorigenesis by activating oxidative

phosphorylation via m6A modification of NDUFS6. Cell Death Dis.

14:5122023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Hua Z, Wei R, Guo M, Lin Z, Yu X, Li X, Gu

C and Yang Y: YTHDF2 promotes multiple myeloma cell proliferation

via STAT5A/MAP2K2/p-ERK axis. Oncogene. 41:1482–1491. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Liu R, Miao J, Jia Y, Kong G, Hong F, Li

F, Zhai M, Zhang R, Liu J, Xu X, et al: N6-methyladenosine reader

YTHDF2 promotes multiple myeloma cell proliferation through

EGR1/p21cip1/waf1/CDK2-Cyclin E1 axis-mediated cell cycle

transition. Oncogene. 42:1607–1619. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Xu J, Wang Y, Ren L, Li P and Liu P:

IGF2BP1 promotes multiple myeloma with chromosome 1q gain via

increasing CDC5L expression in an m6A-dependent manner. Genes Dis.

12:1012142024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

129

|

Bernstein ZS, Kim EB and Raje N: Bone

disease in multiple myeloma: Biologic and clinical implications.

Cells. 11:23082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I,

Gavriatopoulou M and Dimopoulos MA: Pathogenesis of bone disease in

multiple myeloma: From bench to bedside. Blood Cancer J. 8:72018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Liu R, Zhong Y, Chen R, Chu C, Liu G, Zhou

Y, Huang Y, Fang Z and Liu H: m6A reader hnRNPA2B1 drives multiple

myeloma osteolytic bone disease. Theranostics. 12:7760–7774. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

132

|

Jiang F, Tang X, Tang C, Hua Z, Ke M, Wang

C, Zhao J, Gao S, Jurczyszyn A, Janz S, et al: HNRNPA2B1 promotes

multiple myeloma progression by increasing AKT3 expression via

m6A-dependent stabilization of ILF3 mRNA. J Hematol Oncol.

14:542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Guo Y, Jia C, Wang X, Luo K, Chi L, Xu Q,

Gong T and Quan L: HNRNPA2B1 promotes the progression of multiple

myeloma via endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy mediated by

CK2 Kinase. J Proteome Res. 24:5921–5931. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

134

|

Tang J, Li J, Qin S, Xiao Y, Liu J, Chen X

and Zhang Y: Identification and validation of the m6A-binding

protein LRPPRC to promote tumorigenesis in multiple myeloma.

Hematology. 30:25230822025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

135

|

Yao L, Li T, Teng Y, Guo J, Zhang H, Xia L

and Wu Q: ALKHB5-demethylated lncRNA SNHG15 promotes myeloma

tumorigenicity by increasing chromatin accessibility and recruiting

H3K36me3 modifier SETD2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 326:C684–C697.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

136

|

Yu T, Yao L, Yin H, Teng Y, Hong M and Wu

Q: ALKBH5 promotes multiple myeloma tumorigenicity through inducing

m6A-demethylation of SAV1 mRNA and myeloma stem cell phenotype. Int

J Biol Sci. 18:2235–2248. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

137

|

Qu J, Hou Y, Chen Q, Chen J, Li Y, Zhang

E, Gu H, Xu R, Liu Y, Cao W, et al: RNA demethylase ALKBH5 promotes

tumorigenesis in multiple myeloma via TRAF1-mediated activation of

NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene. 41:400–413. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

138

|

Badraldin SQ, Alfarttoosi KH, Sameer HN,

Bishoyi AK, Ganesan S, Shankhyan A, Ray S, Nathiya D, Yaseen A,

Athab ZH and Adil M: Mechanistic role of FTO in cancer

pathogenesis, immune evasion, chemotherapy resistance, and

immunotherapy response. Semin Oncol. 52:1523682025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Xu A, Zhang J, Zuo L, Yan H, Chen L, Zhao

F, Fan F, Xu J, Zhang B, Zhang Y, et al: FTO promotes multiple

myeloma progression by posttranscriptional activation of HSF1 in an

m6A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. Mol Ther. 30:1104–1118. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

140

|

Li JJ, Yu T, Zeng P, Tian J, Liu P, Qiao

S, Wen S, Hu Y, Liu Q, Lu W, et al: Wild-type IDH2 is a therapeutic

target for triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. 15:34452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Song S, Fan G, Li Q, Su Q, Zhang X, Xue X,

Wang Z, Qian C, Jin Z, Li B and Zhuang W: IDH2 contributes to

tumorigenesis and poor prognosis by regulating m6A RNA methylation

in multiple myeloma. Oncogene. 40:5393–5402. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

142

|

Zhang Y, Deng Z, Sun S, Xie S, Jiang M,

Chen B, Gu C and Yang Y: NAT10 acetylates BCL-XL mRNA to promote

the proliferation of multiple myeloma cells through PI3K-AKT

pathway. Front Oncol. 12:9678112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

143

|

Liu H, Zhang X, Lu Q and Zhang H: NAT10

contributes to the progression of multiple myeloma through ac4C

modification of GPR37. Hematology. 30:25557792025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Ren H, Liu C, Wu H, Wang Z, Chen S, Zhang

X, Ren J, Qiu H and Zhou L: m5C Regulator-mediated methylation

modification clusters contribute to the immune microenvironment

regulation of multiple myeloma. Front Genet. 13:9201642022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

145

|

Jiang Y, Sun J, Chen Y, Cheng L, Feng S,

Wang Y and Sun C: NSUN2-mediated RNA m(5)C modification drives

multiple myeloma progression by enhancing the stability of HIP1

mRNA. Sci Rep. 15:278882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

146

|

Fu J, Han X, Gao W, Yu M and Cui X: m1A

regulator-mediated methylation modifications and gene signatures

and their prognostic value in multiple myeloma. Exp Ther Med.

29:182025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

147

|

Cohen YC, Zada M, Wang SY, Bornstein C,

David E, Moshe A, Li B, Shlomi-Loubaton S, Gatt ME, Gur C, et al:

Identification of resistance pathways and therapeutic targets in

relapsed multiple myeloma patients through single-cell sequencing.

Nat Med. 27:491–503. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Ferguson ID, Patiño-Escobar B, Tuomivaara

ST, Lin YT, Nix MA, Leung KK, Kasap C, Ramos E, Nieves Vasquez W,

Talbot A, et al: The surfaceome of multiple myeloma cells suggests

potential immunotherapeutic strategies and protein markers of drug

resistance. Nat Commun. 13:41212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Sun J, Corradini S, Azab F, Shokeen M, Muz

B, Miari KE, Maksimos M, Diedrich C, Asare O, Alhallak K, et al:

IL-10R inhibition reprograms tumor-associated macrophages and

reverses drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Leukemia.

38:2355–2365. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Bird S and Pawlyn C: IMiD resistance in

multiple myeloma: Current understanding of the underpinning biology

and clinical impact. Blood. 142:131–140. 2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

151

|

Tzelepis K, Rausch O and Kouzarides T:

RNA-modifying enzymes and their function in a chromatin context.

Nat Struct Mol Biol. 26:858–862. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

152

|

Chen H, Jia B, Zhang Q and Zhang Y:

Meclofenamic acid restores gefinitib sensitivity by downregulating

breast cancer resistance protein and multidrug resistance protein 7

via FTO/m6A-Demethylation/c-Myc in non-small cell lung cancer.

Front Oncol. 12:8706362022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Yuan J, Guan W, Li X, Wang F, Liu H and Xu

G: RBM15-mediating MDR1 mRNA m6A methylation regulated by the TGF-β

signaling pathway in paclitaxel-resistant ovarian cancer. Int J

Oncol. 63:1122023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

154

|

Liu R, Shen Y, Hu J, Wang X, Wu D, Zhai M,

Bai J and He A: Comprehensive Analysis of m6A RNA methylation

regulators in the prognosis and immune microenvironment of multiple

myeloma. Front Oncol. 11:7319572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

155

|

Wang C, Li L, Li M, Wang W and Jiang Z:

FTO promotes Bortezomib resistance via m6A-dependent

destabilization of SOD2 expression in multiple myeloma. Cancer Gene

Ther. 30:622–628. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

156

|

Prabhu KS, Ahmad F, Kuttikrishnan S, Leo

R, Ali TA, Izadi M, Mateo JM, Alam M, Ahmad A, Al-Shabeeb Akil AS,

et al: Bortezomib exerts its anti-cancer activity through the

regulation of Skp2/p53 axis in non-melanoma skin cancer cells and

C. elegans. Cell Death Discov. 10:2252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

157

|

Sogbein O, Paul P, Umar M, Chaari A,

Batuman V and Upadhyay R: Bortezomib in cancer therapy: Mechanisms,

side effects, and future proteasome inhibitors. Life Sci.

358:1231252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

158

|

Hurt EM, Thomas SB, Peng B and Farrar WL:

Integrated molecular profiling of SOD2 expression in multiple

myeloma. Blood. 109:3953–3962. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

159

|

Hodge DR, Peng B, Pompeia C, Thomas S, Cho

E, Clausen PA, Marquez VE and Farrar WL: Epigenetic silencing of

manganese superoxide dismutase (SOD-2) in KAS 6/1 human multiple

myeloma cells increases cell proliferation. Cancer Biol Ther.

4:585–592. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Song IS, Kim HK, Lee SR, Jeong SH, Kim N,

Ko KS, Rhee BD and Han J: Mitochondrial modulation decreases the

bortezomib-resistance in multiple myeloma cells. Int J Cancer.

133:1357–1367. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

161

|

Jomova K, Alomar SY, Alwasel SH,

Nepovimova E, Kuca K and Valko M: Several lines of antioxidant

defense against oxidative stress: antioxidant enzymes,

nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and

low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch Toxicol. 98:1323–1367.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

162

|

Huang R, Chen H, Liang J, Li Y, Yang J,

Luo C, Tang Y, Ding Y, Liu X, Yuan Q, et al: Dual role of reactive

oxygen species and their application in cancer therapy. J Cancer.

12:5543–5561. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

163

|

Jahankhani K, Taghipour N, Nikoonezhad M,

Behboudi H, Mehdizadeh M, Kadkhoda D, Hajifathali A and Mosaffa N:

Adjuvant therapy with zinc supplementation; anti-inflammatory and

anti-oxidative role in multiple myeloma patients receiving

autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A randomized

controlled clinical trial. Biometals. 37:1609–1627. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

164

|

Yu W, Cao D, Zhou H, Hu Y and Guo T:

PGC-1α is responsible for survival of multiple myeloma cells under

hyperglycemia and chemotherapy. Oncol Rep. 33:2086–2092. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

165

|

Zhang Y, Cao X, Li W, Cui Z, Mao J, Yao R

and Liu L: ALKBH5 reverses romidepsin-mediated anti-multiple

myeloma activity via regulation of m6A modification of FOXM1.

Biochem Pharmacol. 239:1169982025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

166

|

Quan L, Jia C, Guo Y, Chen Y, Wang X, Xu Q

and Zhang Y: HNRNPA2B1-mediated m6A modification of TLR4 mRNA

promotes progression of multiple myeloma. J Transl Med. 20:5372022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

167

|

Giallongo C, Tibullo D, Puglisi F, Barbato

A, Vicario N, Cambria D, Parrinello NL, Romano A, Conticello C,

Forte S, et al: Inhibition of TLR4 signaling affects mitochondrial

fitness and overcomes bortezomib resistance in myeloma plasma

cells. Cancers (Basel). 12:19992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

168

|

Bagratuni T, Sklirou AD, Kastritis E,

Liacos CI, Spilioti C, Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou E, Kanellias N,

Gavriatopoulou M, Terpos E, Trougakos IP and Dimopoulos MA:

Toll-like receptor 4 activation promotes multiple myeloma cell

growth and survival via suppression of the endoplasmic reticulum

stress factor chop. Sci Rep. 9:32452019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

169

|

Jiang S, Gao L, Li J, Zhang F, Zhang Y and

Liu J: N6-methyladenosine-modified circ_0000337 sustains bortezomib

resistance in multiple myeloma by regulating DNA repair. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 12:13832322024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

170

|

Wang G and Wu W, He D, Wang J, Kong H and

Wu W: N6-methyladenosine-mediated upregulation of H19 promotes

resistance to bortezomib by modulating the miR-184/CARM1 axis in

multiple myeloma. Clin Exp Med. 25:1022025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

171

|

Wang Z, He J, Bach DH, Huang YH, Li Z, Liu

H, Lin P and Yang J: Induction of m6A methylation in adipocyte

exosomal LncRNAs mediates myeloma drug resistance. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 41:42022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

172

|

Sun X, Zhou Y, Zhu W and Chen H: Research

progress on N6-methyladenosine and non-coding RNA in multiple

myeloma. Discov Oncol. 16:6152025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

173

|

Huang Y, Xia W, Dong Z and Yang CG:

Chemical inhibitors targeting the oncogenic m6A Modifying Proteins.

Acc Chem Res. 56:3010–3022. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

174

|

He B, Hu Y, Wu Y, Wang C, Gao L, Gong C,

Li Z, Gao N, Yang H, Xiao Y and Yang S: Helicobacter pylori CagA

elevates FTO to induce gastric cancer progression via a

'hit-and-run' paradigm. Cancer Commun (Lond). 45:608–631. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

175

|

Xiao L, Li X, Mu Z, Zhou J, Zhou P, Xie C

and Jiang S: FTO inhibition enhances the antitumor effect of

temozolomide by targeting MYC-miR-155/23a cluster-MXI1 feedback

circuit in glioma. Cancer Res. 80:3945–3958. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

176

|

Xu Y, Zhou J, Li L, Yang W, Zhang Z, Zhang

K, Ma K, Xie H, Zhang Z, Cai L, et al: FTO-mediated autophagy

promotes progression of clear cell renal cell carcinoma via

regulating SIK2 mRNA stability. Int J Biol Sci. 18:5943–5962. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

177

|

Jiang L, Liang R, Luo Q, Chen Z and Song

G: Targeting FTO suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting

ERBB3 and TUBB4A expression. Biochem Pharmacol. 226:1163752024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

178

|

Zhang J, Li G, Wu R, Shi L, Tian C, Jiang

H, Che H, Jiang Y, Jin Z, Yu R, et al: The m6A RNA demethylase FTO

promotes radioresistance and stemness maintenance of glioma stem

cells. Cell Signal. 132:1117822025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

179

|

Yang Q and Al-Hendy A: The functional role

and regulatory mechanism of FTO m6A RNA demethylase in human

uterine leiomyosarcoma. Int J Mol Sci. 24:79572023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

180

|

Su R, Dong L, Li Y, Gao M, Han L,

Wunderlich M, Deng X, Li H, Huang Y, Gao L, et al: Targeting FTO

suppresses cancer stem cell maintenance and immune evasion. Cancer

Cell. 38:79–96.e11. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

181

|

Huff S, Kummetha IR, Zhang L, Wang L, Bray

W, Yin J, Kelley V, Wang Y and Rana TM: Rational design and

optimization of m6A-RNA Demethylase FTO inhibitors as anticancer

agents. J Med Chem. 65:10920–10937. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

182

|

Peng S, Xiao W, Ju D, Sun B, Hou N, Liu Q,

Wang Y, Zhao H, Gao C, Zhang S, et al: Identification of entacapone

as a chemical inhibitor of FTO mediating metabolic regulation

through FOXO1. Sci Transl Med. 11:eaau71162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

183

|

Ramedani F, Jafari SM, Saghaeian Jazi M,

Mohammadi Z and Asadi J: Anti-cancer effect of entacaponeon

esophageal cancer cells via apoptosis induction and cell cycle

modulation. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 6:e17592023.

|

|

184

|

Yankova E, Blackaby W, Albertella M, Rak

J, De Braekeleer E, Tsagkogeorga G, Pilka ES, Aspris D, Leggate D,

Hendrick AG, et al: Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a

strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 593:597–601. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

185

|

Sun Y, Shen W, Hu S, Lyu Q, Wang Q, Wei T,

Zhu W and Zhang J: METTL3 promotes chemoresistance in small cell

lung cancer by inducing mitophagy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.

42:652023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

186

|

Jin X, Lv Y, Bie F, Duan J, Ma C, Dai M,

Chen J, Lu L, Xu S, Zhou J, et al: METTL3 confers oxaliplatin

resistance through the activation of G6PD-enhanced pentose

phosphate pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Differ.

32:466–479. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

187

|

Hao S, Sun H, Sun H, Zhang B, Ji K, Liu P,

Nie F and Han W: STM2457 Inhibits the invasion and metastasis of

pancreatic cancer by down-regulating BRAF-Activated Noncoding RNA

N6-Methyladenosine modification. Curr Issues Mol Biol.

45:8852–8863. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

188

|

Tang H, Zhang R and Zhang A:

Small-molecule inhibitors targeting RNA m(6)A modifiers for cancer

therapeutics : Latest advances and future perspectives. J Med Chem.

68:18114–18142. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

189

|

Du Y, Yuan Y, Xu L, Zhao F, Wang W, Xu Y

and Tian X: Discovery of METTL3 small molecule inhibitors by

virtual screening of natural products. Front Pharmacol.

13:8781352022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

190

|

Dolbois A, Bedi RK, Bochenkova E, Müller

A, Moroz-Omori EV, Huang D and Caflisch A:

1,4,9-Triazaspiro[5.5]undecan-2-one derivatives as potent and

selective METTL3 Inhibitors. J Med Chem. 64:127382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

191

|

Li J and Gregory RI: Mining for METTL3

inhibitors to suppress cancer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 28:460–462.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

192

|

Malacrida A, Di Domizio A, Bentivegna A,

Cislaghi G, Messuti E, Tabano SM, Giussani C, Zuliani V, Rivara M

and Nicolini G: MV1035 overcomes temozolomide resistance in

patient-derived glioblastoma stem cell lines. Biology (Basel).

11:702022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

193

|

Li N, Kang Y, Wang L, Huff S, Tang R, Hui

H, Agrawal K, Gonzalez GM, Wang Y, Patel SP and Rana TM: ALKBH5

regulates anti-PD-1 therapy response by modulating lactate and

suppressive immune cell accumulation in tumor microenvironment.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117:20159–20170. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

194

|

Tang W, Xu N, Zhou J, He Z, Lenahan C,

Wang C, Ji H, Liu B, Zou Y, Zeng H and Guo H: ALKBH5 promotes

PD-L1-mediated immune escape through m6A modification of ZDHHC3 in

glioma. Cell Death Discov. 8:4972022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

195

|

Schott A, Simon T, Müller S, Rausch A,