Introduction

Cancer cachexia, a syndrome characterized by severe

weight loss and muscle depletion, is of significant concern in

patients with advanced cancer. Its incidence rate ranges from

50-80%, and markedly affects mortality, accounting for up to 20% of

cancer-related deaths (1,2). In Japan, the European Palliative Care

Research Collaborative criteria and European Society for Medical

Oncology criteria are used in cancer cachexia management as no

specific guidelines exist for this condition in the country

(3,4).

Cancer cachexia is a complex syndrome involving

various factors, including skeletal muscle loss, activation of

inflammatory cytokines, metabolic disturbances due to insulin

resistance, and increased catabolism of hyperlipidemia (5,6).

Cancer cachexia progression may result in irreversible

malnutrition, significantly reducing the activities of daily living

and quality of life, leading to worse prognosis. As metabolic

disorders progress, effective nutrient utilization is impaired;

hence, multidisciplinary interventions, such as nutritional

therapy, exercise, and pharmacotherapy are essential from the early

stages of cancer cachexia (6,7).

Promising pharmacological approaches for cachexia management

include ghrelin agonists, beta-blockers, beta-adrenergic agonists,

androgen receptor agonists, and antimyostatin peptides (8). However, their clinical application in

cancer cachexia management remains limited, and their use is

associated with potential adverse effects, necessitating cautious

application.

Anamorelin, the first oral small-molecule

ghrelin-like agent worldwide, became available in Japan in 2021 and

was anticipated to alleviate cancer cachexia-related weight loss

and anorexia (9). Ghrelin, a

growth hormone secretagogue primarily secreted in the stomach, acts

on appetite-promoting neurons in the hypothalamus and indirectly

stimulates muscle protein synthesis by stimulating the secretion of

the growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 in the liver

(10-12).

Additionally, ghrelin is believed to counteract cancer cachexia

through multiple mechanisms, including its anti-inflammatory

effects and inhibition of muscle atrophy (13,14).

Anamorelin is indicated for cancer cachexia management in patients

with non-small cell lung, gastric, pancreatic, and colorectal

cancers. Notably, its use necessitates caution owing to potential

adverse events, including fatal arrhythmias and hyperglycemia

(15).

Considering that anamorelin is a Japan-specific

medicine, real-world data on its use remain limited. Furthermore,

although early intervention is recommended for cancer cachexia,

research on the optimal timing of anamorelin administration is

scarce, highlighting the need for further investigation. Therefore,

the aim of this retrospective study was to investigate the use of

anamorelin in cancer cachexia treatment and examine the

relationship between treatment duration and patient survival.

Patients and methods

Study design and end point

This retrospective study included patients who were

prescribed anamorelin between August 2021 and January 2024 at the

Saitama Cancer Center, Japan. Eligible patients had unresectable,

advanced, or recurrent non-small cell lung, gastric, pancreatic, or

colorectal cancers with cachexia, defined by >5% weight loss and

anorexia within 6 months, along with at least two of the following

symptoms: i) fatigue or malaise; ii) muscle weakness; and iii) one

or more of the following conditions: C-reactive protein (CRP) level

>5 mg/l, hemoglobin level <12 g/dl, and serum albumin level

<3.2 g/dl. The inclusion criteria align with the clinical

indications for prescribing anamorelin. Inclusion criteria were

retrospectively assessed using electronic medical records,

including documented weight loss percentages, clinical notes on

anorexia, and laboratory test results for cachexia-related symptoms

(e.g., CRP, hemoglobin, and serum albumin levels). This review

ensured consistent application of the eligibility criteria.

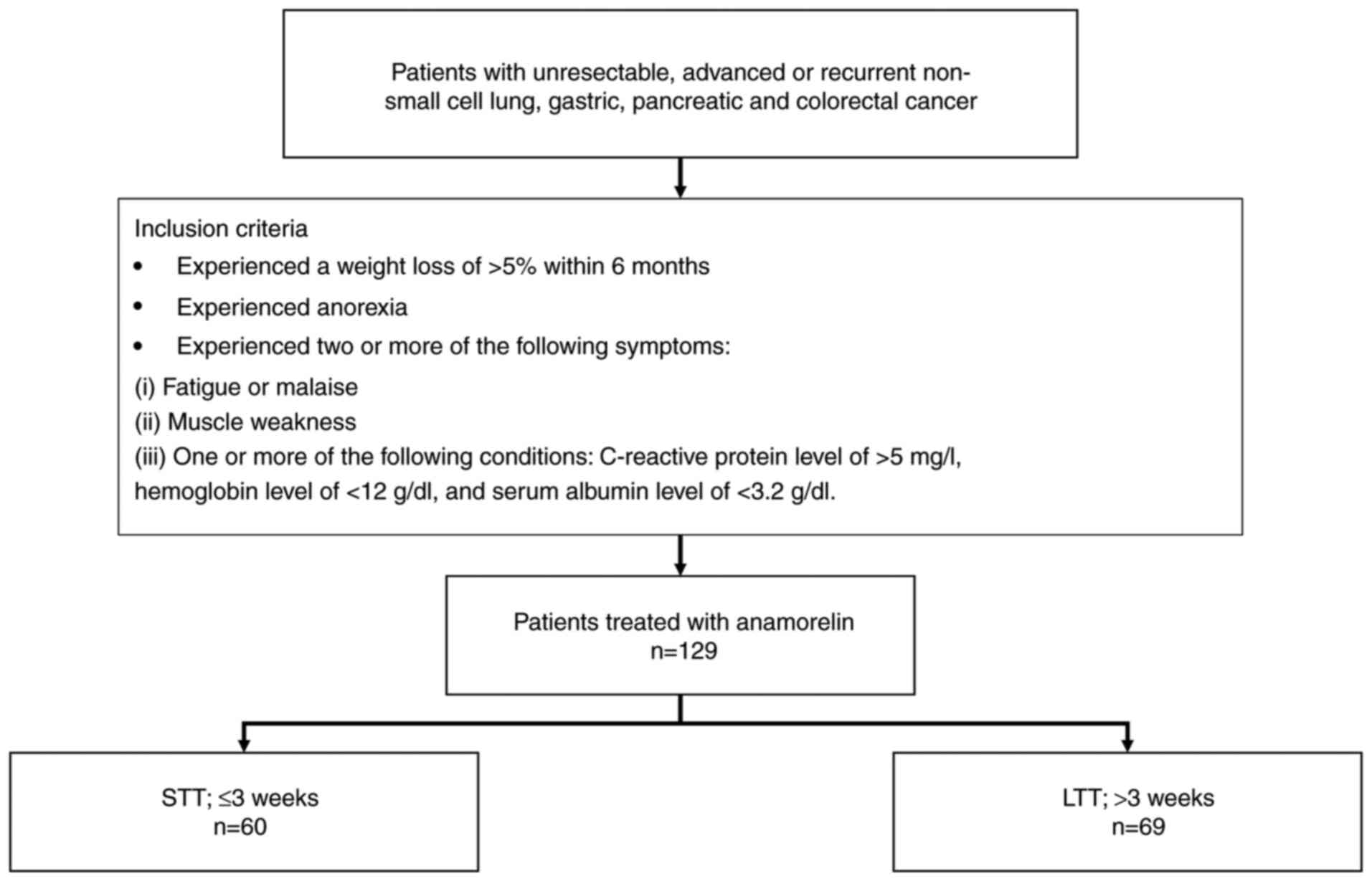

Fig. 1 depicts the study

flowchart. Because the anamorelin package insert states that its

efficacy is determined in the third week of administration,

patients were classified into two groups: short-term treatment

(STT; discontinuation within 3 weeks) and long-term treatment (LTT;

>3 weeks). The primary endpoint was to evaluate the effect of

treatment duration on the survival of patients with cancer

cachexia. The secondary endpoint was to investigate the time from

diagnosis to treatment initiation for each type of cancer and the

duration of anamorelin administration.

Data extraction

The following baseline patient characteristics at

the initiation of anamorelin treatment were extracted from the

patient medical records: age; sex; primary cancer site; Eastern

Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) score;

albumin, CRP, and hemoglobin levels; Glasgow Prognostic Score

(GPS); date of diagnosis of stage IV, inoperable advanced, or

recurrent cancer; history of surgery for gastric cancer; reason for

discontinuation of anamorelin; start and end dates of anamorelin

treatment; reason for completion of anamorelin treatment; and date

of death or last hospital visit. The ECOG PS 0-2 classification,

which was previously used as a selection criterion in national and

international phase III trials, was used as the standard in this

study (16). The GPS was

calculated using the following formula: CRP level <10 mg/l and

albumin level ≥3.5 g/dl, GPS=0; CRP level >10 mg/l, GPS=1; and

CRP level >10 mg/l and albumin level <3.5 g/dl,

GPS=2(17).

Reasons for discontinuation of anamorelin were

categorized as treatment ineffectiveness, difficulty in medication

intake, psychological burden of medicine intake, death, and other

reasons. Treatment ineffectiveness was determined clinically,

primarily on weight changes and patient-reported symptoms, such as

persistent anorexia, despite continued treatment. Difficulty in

medication intake was identified from medical records describing

swallowing difficulties (dysphagia), nausea, or a general decline

in physical condition hindering oral intake. The psychological

burden of taking the medicine was assessed through medical records

of patient-reported concerns, including reluctance to take oral

medication owing to anxiety or subjective distress related to

medication intake.

Statistical analysis

The Fisher's exact test was used to compare nominal

variables, whereas the Mann-Whitney U test was used to

compare continuous variables. Outliers were defined as values

exceeding the third quartile by more than 1.5 times the

interquartile range. Overall survival curves were generated using

the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences in the curves were

compared using a log-rank test. Patients were censored if they met

one of the following criteria: i) overall survival of >365 days

or ii) data not traceable owing to other reasons, including

hospital transfer. Statistical analyses were performed using EZR

ver. 1.66(18), with a P-value of

<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 129 patients were included in this study,

with 60 and 69 patients in the STT and LTT groups, respectively

(Table I). Compared with the LTT

group, the STT group had significantly more patients with gastric

cancer (P=0.013) or an albumin level of <3.5 g/dl (P=0.044). In

contrast, the LTT group had a significantly higher number of older

patients (P=0.021) and those with an ECOG PS of 0-2 (P=0.008) than

the STT group. No significant differences were observed between the

two groups with respect to other patient characteristics. A

comparison of the number of patients who underwent surgery for

gastric cancer showed no significant differences between the groups

(STT group: 23.1% vs. LTT group: 20.0%, P=1.0). The most common

reason for termination of anamorelin treatment in both groups was

treatment ineffectiveness (STT group, 33.3%; LTT group, 21.7%). In

the STT group alone, the reasons for termination were difficulty in

medication intake (23.3%) and the psychological burden of

medication intake (11.7%), while in the LTT group, the reasons were

death (13.0%) and the psychological medication intake (10.1%).

Among patients in the STT group who discontinued owing to

difficulty in medication intake, the primary factors were

dysphagia, nausea, and general deterioration in physical condition.

Importantly, no discontinuations were attributed to side effects of

anamorelin.

| Table ICharacteristics of the study

patients. |

Table I

Characteristics of the study

patients.

| Characteristics | STT group (n=60) | LTT group (n=69) | P-value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range)a | 71 (36-84) | 73 (50-90) | 0.021 |

| Male, n

(%)b | 40 (66.7) | 52 (75.4) | 0.331 |

| Primary cancer, n

(%)b | | | |

|

Gastric

cancer | 26 (43.3) | 15 (21.7) | 0.013 |

|

Colorectal

cancer | 5 (8.3) | 6 (8.7) | >0.999 |

|

Pancreatic

cancer | 14 (23.3) | 22 (31.9) | 0.328 |

|

NSCLC | 15 (25.0) | 26 (37.7) | 0.134 |

| ECOG PS score, n

(%)b | | | |

|

0-2 | 39 (65.0) | 59 (85.5) | 0.008 |

|

3-4 | 21 (35.0) | 10 (14.5) | 0.008 |

| Median serum albumin

level, g/dl (range)a | 3.1 (2.0-4.7) | 3.4 (1.5-4.8) | 0.095 |

| Serum albumin level

<3.5 g/dl, n (%)b | 43 (71.7) | 36 (52.2) | 0.044 |

| Median C-reactive

protein level, mg/l (range)a | 20.7 (0.1-305.2) | 14.7 (0-257.9) | 0.227 |

| C-reactive protein

level, n (%)b | | | |

|

>10

mg/l | 39 (65.0) | 39 (58.0) | 0.468 |

|

>5

mg/l | 46 (76.7) | 45 (65.2) | 0.242 |

| Median hemoglobin

level, g/dl (range)a | 11.0 (7.2-15.2) | 10.4 (7.7-15.7) | 0.404 |

| Hemoglobin level

<12.0 g/dl, n (%)b | 41 (68.3) | 52 (75.4) | 0.326 |

| Glasgow prognostic

scorec, n

(%)b | | | |

|

0 | 21 (35.0) | 29 (42.0) | 0.468 |

|

1 | 8 (13.3) | 14 (20.3) | 0.350 |

|

2 | 31 (51.7) | 25 (36.2) | 0.109 |

| Median time from

diagnosis to treatment initiation, days (range)a | 279 (0-2486) | 193 (0-3122) | 0.286 |

| Median administration

period, days (range)a | 9.5 (0-19) | 44.5 (21-444) | <0.0001 |

Timing of anamorelin initiation and

duration of treatment

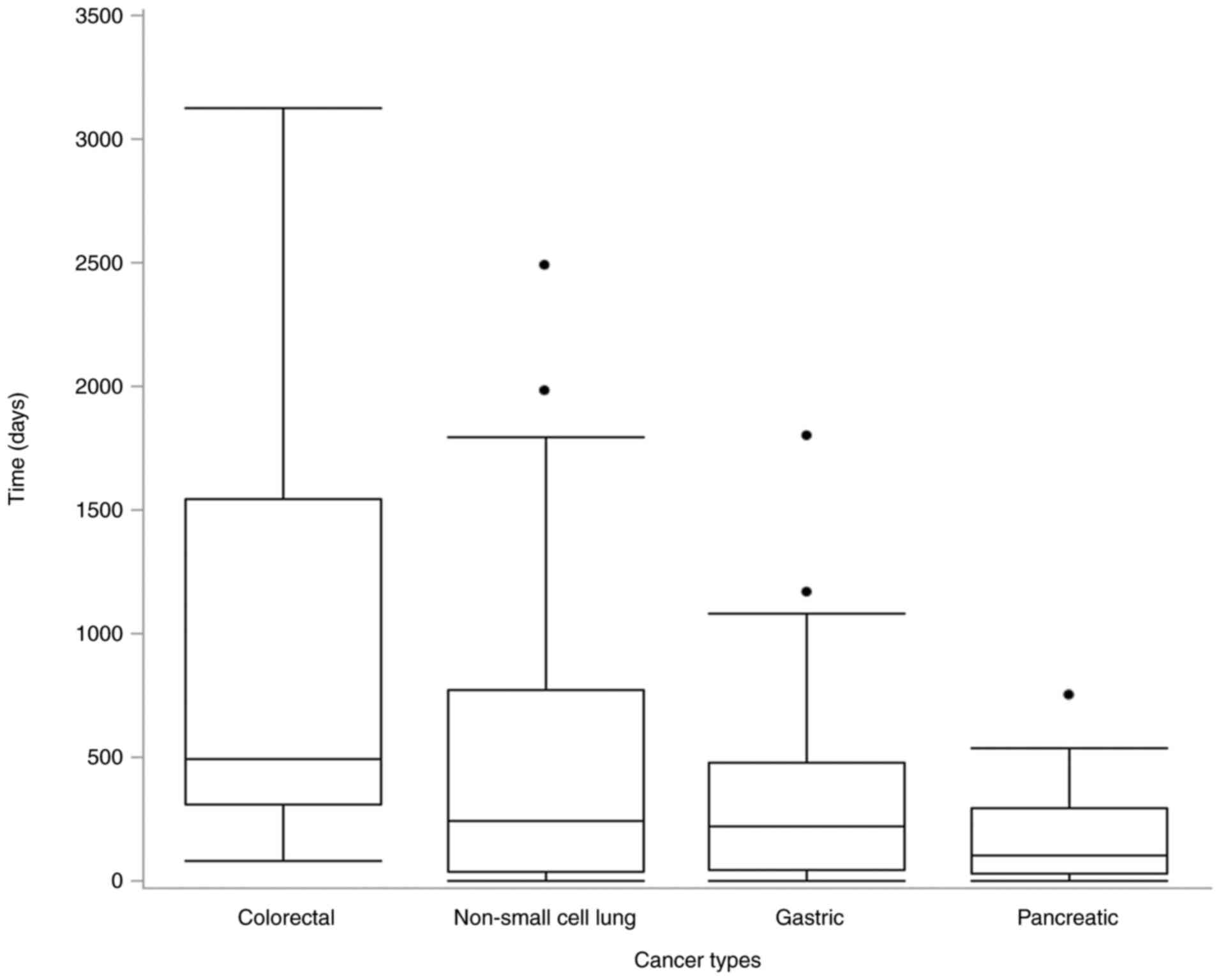

Fig. 2 shows the

time between diagnosis and anamorelin treatment initiation. The

median time from the date of diagnosis to the start of anamorelin

treatment was the longest among patients with colorectal cancer

(489 days), followed by those with non-small cell lung cancer (244

days), gastric cancer (222 days), and pancreatic cancer (99 days).

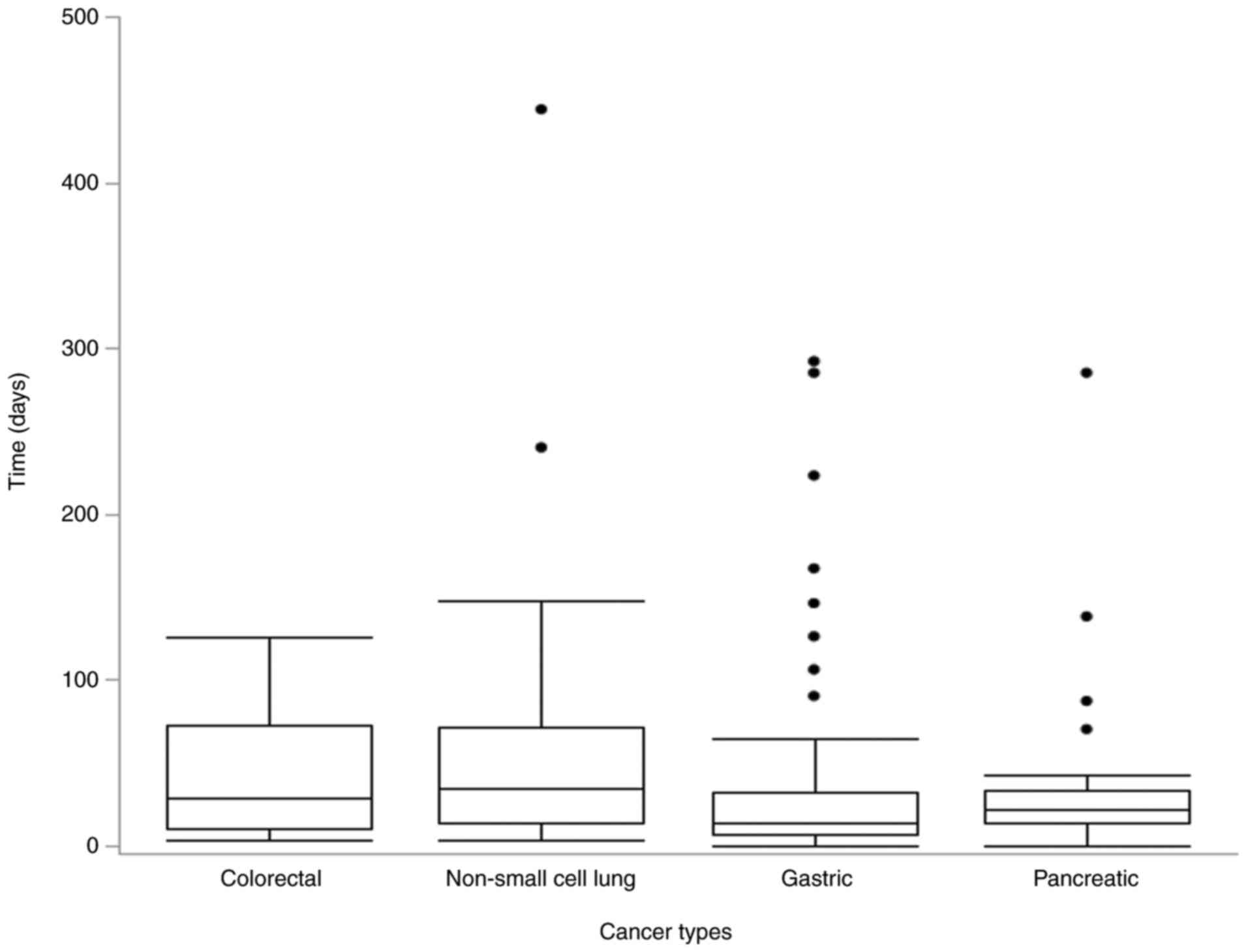

The anamorelin treatment period is shown in Fig. 3. The median duration of anamorelin

treatment was the longest for lung cancer (34 days), followed by

that for colon cancer (28 days), pancreatic cancer (22 days), and

gastric cancer (14 days). Three cases with non-small cell lung

cancer (treatment durations: 240, 444, and 773 days), eight with

stomach cancer (treatment durations: 90, 106, 126, 146, 167, 223,

285, and 292 days), and four with pancreatic cancer (treatment

durations: 70, 87, 138, and 285 days) were analyzed as

outliers.

Period from anamorelin treatment

initiation to death or last hospital visit

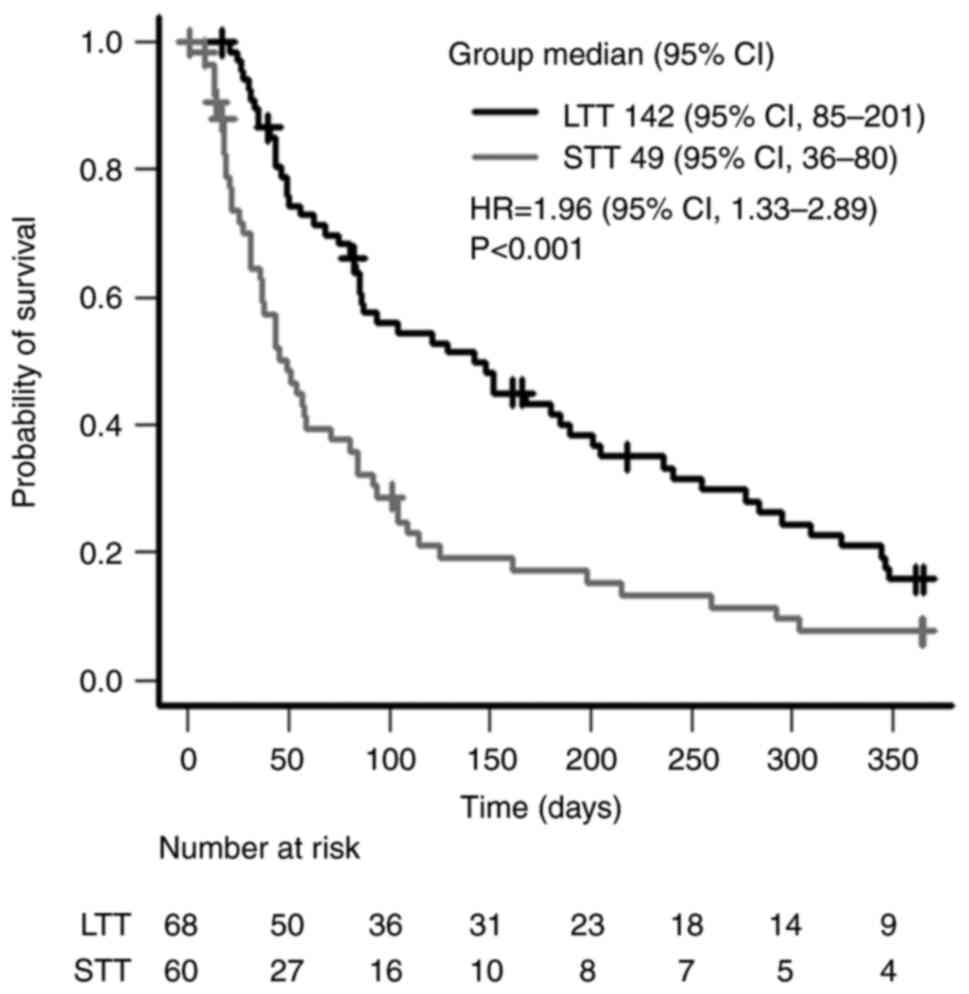

The overall survival rate from the start of

anamorelin treatment to death or last hospital visit is shown in

Fig. 4. The median survival

durations were 49 days [95% confidence interval (CI), 36-80] and

142 days (95% CI, 85-201) in the STT and LTT groups, respectively,

with the duration in the LTT group being significantly longer

(P<0.001). The data of a patient in the LTT group were excluded

from the analysis as the treatment end date was unknown.

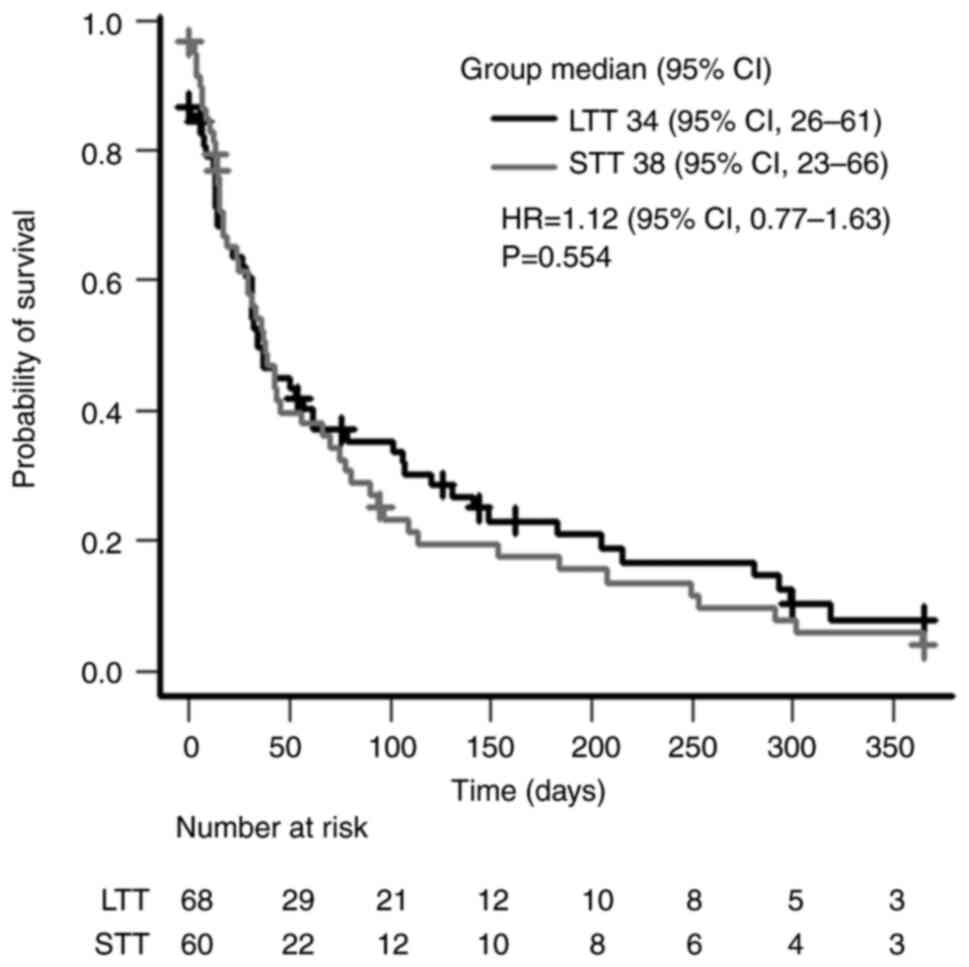

Survival after completion of

anamorelin treatment

The overall survival rate was defined as the number

of days from the day after the last day of anamorelin treatment to

the day of death or last hospital visit (Fig. 5). The median survival durations

were 38 days (95% CI, 23-66 days) and 34 days (95% CI, 26-61 days)

in the STT and LTT groups, respectively (P=0.554). The data of a

patient in the LTT group were excluded from the analysis as the

treatment end date was unknown.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, the use of anamorelin

in managing cancer cachexia was examined, focusing on patient

characteristics and survival during and after treatment. Age,

gastric cancer, hypoalbuminemia, and ECOG PS score were identified

as patient factors affecting treatment duration. While patients in

the LTT group had significantly longer survival duration during

treatment than those in the STT group, post-discontinuation

survival did not differ significantly among groups, regardless of

treatment duration. These findings suggested that anamorelin

treatment duration can be a predictor of survival during

treatment.

In this study, anamorelin was administered long term

to patients with an ECOG PS score of 0-2. Our findings align with

those of studies examining the efficacy of anamorelin in patients

with pancreatic cancer with a poor ECOG PS score and studies

investigating factors associated with the early discontinuation of

anamorelin (19,20). This result suggests that patients

with good ECOG PS scores may tolerate long-term anamorelin

treatment. In this study, the LTT group had a higher number of

older patients, possibly owing to the role of anamorelin in

increasing sensitivity to ghrelin, which declines with age and may

activate relevant signaling pathways. Blood ghrelin levels

generally decrease with age; however, the relationship between

ghrelin and aging remains unclear, as existing studies have yielded

conflicting results, warranting further investigation (21). Regarding cancer type, the STT group

had a higher number of patients with gastric cancer. Ghrelin is a

peptide hormone produced and secreted mainly in the gastric body.

Total gastrectomy reduces blood ghrelin levels by 10-30% and distal

gastrectomy decreases these levels by 50-70% (22). In the present study, the surgical

history of patients with gastric cancer was compared between the

two groups; however, no effect of surgery on treatment duration was

observed. This result suggests that factors beyond gastric

preservation may have affected the duration of anamorelin

treatment; however, further studies with a larger sample size are

warranted to validate this. In addition, hypoalbuminemia was more

common in the STT group, suggesting its potential as a predictive

factor for treatment duration. Given that hypoalbuminemia is

associated with reduced survival rate of patients with gastric

cancer, it may contribute to considerably shorter treatment

duration observed in this patient population (23). Further investigation into the

interplay between cancer type and hypoalbuminemia using larger

cohorts is warranted.

The median treatment duration tended to be shorter

for non-small cell lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric

cancers, in that order. The results, except that of gastric cancer,

were similar to those of the interim analysis of the post-marketing

survey for anamorelin. Notably, the median treatment duration for

gastric cancer was 14 days shorter in this study than the 29 days

reported in the post-marketing survey (24). In addition, gastric cancer was

associated with a high frequency of abnormal values compared with

other cancer types, suggesting that additional factors may

influence the duration of anamorelin administration in this

context. Further detailed studies are warranted to investigate

this.

Survival during anamorelin treatment was

significantly shorter in the STT group than in the LTT group.

Similar results were reported in a study involving a small number

of cases (20). In this study, the

reason for treatment discontinuation was also investigated,

revealing that more patients in the STT group discontinued

treatment because of medication intake difficulty. Therefore, it is

recommended that anamorelin be prescribed to patients with a good

ECOG PS score who can tolerate prolonged treatment. We found that

the median survival duration after the completion of anamorelin

treatment was approximately 1 month, regardless of the treatment

duration. To the best of our knowledge, this is a novel finding.

The predicted survival time for refractory cachexia is generally

considered to be less than 3 months (3). However, this period has been

established by experts as an empirical guideline and is not based

on real-world data. Moreover, our study is the first to report

survival after the discontinuation of anamorelin for cachexia.

Based on our findings, determining whether anamorelin can be

effective against refractory cachexia or whether the predicted

survival period has been overestimated remains a subject for future

research.

This study had several limitations. First, this was

a single-center, retrospective, observational study conducted among

Japanese patients, which may limit the generalizability and

validity of its findings to a broader population. Second,

limitations inherent to retrospective studies, such as selection

and reporting bias cannot be ruled out. Third, the observed

prolonged survival in the LTT group may have been influenced by

immortal time bias, which is an inherent limitation of the study

design. Although time-dependent analyses or sensitivity analyses

could potentially address this issue, such approaches were not

feasible in the present study owing to the retrospective nature of

the data and limitations in the dataset structure. Specifically,

making multiple assumptions regarding variable selection and the

handling of missing data was difficult. Furthermore, prior studies

have provided limited evidence regarding causal relationships in

this context. Therefore, we decided not to perform sensitivity

analyses, as they were unlikely to improve the robustness or

reliability of our findings. We acknowledge this as a

methodological limitation, and future studies should consider more

refined analytical strategies to minimize the impact of immortal

time bias. Fourth, patient characteristics and prognosis differ

according to cancer type. Therefore, a cancer type-specific

analysis would have been preferable. However, in this study,

stratified analysis was challenging owing to statistical

limitations owing to the limited number of patients with each

cancer type. Additionally, although factors such as patient age,

presence of gastric cancer, PS, and serum albumin levels may

independently affect survival, considering the scope of the study,

adjustments using propensity score matching or subgroup analysis

were not feasible owing to the small sample size. Fifth, prognostic

factors such as exercise therapy, nutritional support, and

chemotherapy were not examined in this study. Hence, future studies

addressing these limitations are warranted. Sixth, the

applicability of our findings may be influenced by cultural,

healthcare, and demographic differences. Variations in dietary

habits, patient preferences, and perceptions of appetite loss could

affect treatment adherence and efficacy. Differences in healthcare

systems, including access to supportive care and nutritional

interventions, may also impact real-world outcomes. Additionally,

racial differences in drug metabolism and cachexia progression

could influence treatment response. Finally, anamorelin is

currently approved only in Japan, making it a drug unique to the

Japanese healthcare system. Its clinical use remains geographically

limited, and its applicability to other healthcare settings is

unclear. Given these limitations, further studies are warranted to

evaluate its effectiveness in diverse patient populations and

different healthcare environments.

Notably, anamorelin is only approved in Japan,

limiting its clinical applicability to other healthcare settings.

To the best of our knowledge, no single-center study with a larger

number of patients has been conducted, making our findings an

important source of clinical information. Nevertheless, further

investigation through a larger multicenter prospective study is

warranted.

In conclusion, the study findings indicated that

older patients with better ECOG PS scores exhibited a longer

treatment duration, whereas those with gastric cancer and

hypoalbuminemia had a shorter treatment duration. In addition, the

duration of anamorelin treatment was reflected in the survival of

patients; however, the main novel finding of this study was that

the survival time after treatment discontinuation remained

approximately one month, regardless of the length of treatment.

Considering the limited information on the efficacy and safety of

anamorelin, future multicenter prospective studies with relatively

larger sample sizes are warranted.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MoS was the principal investigator. MiS, DT, TA, KT,

TN and MoS planned the study protocol and performed data

collection. MH, MiS and MoS performed data analysis. MiS and MoS

wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MiS, MO and MoS supervised

the study, contributed to the interpretation of data and approved

the final draft. All authors commented on the previous versions of

the manuscript. TA, KT, TN and MO confirmed the authenticity of the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board (IRB) of Saitama Cancer Center (IRB no. 1398; Ina,

Japan), and all procedures were performed in accordance with The

Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for informed consent was

waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interest.

References

|

1

|

Gullett N, Rossi P, Kucuk O and Johnstone

PAS: Cancer-induced cachexia: A guide for the oncologist. J Soc

Integr Oncol. 7:155–169. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Argilés JM, Busquets S, Stemmler B and

López-Soriano FJ: Cancer cachexia: Understanding the molecular

basis. Nat Rev Cancer. 14:754–762. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I,

Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, Jatoi A, Loprinzi C, MacDonald N,

Mantovani G, et al: Definition and classification of cancer

cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 12:489–495.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Arends J, Strasser F, Gonella S, Solheim

TS, Madeddu C, Ravasco P, Buonaccorso L, De Van Der Schueren MA,

Baldwin C, Chasen M, et al: Cancer cachexia in adult patients: ESMO

clinical practice guidelines*. ESMO Open. 6(100092)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Argilés JM, Moore-Carrasco R, Busquets S

and López-Soriano FJ: Catabolic mediators as targets for cancer

cachexia. Drug Discov Today. 8:838–844. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Argilés JM, Busquets S and López-Soriano

FJ: Cytokines as mediators and targets for cancer cachexia. Cancer

Treat Res. 130:199–217. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine:

Clinical guidelines for infusion therapy in advanced cancer

patients. KANEHARA & Co., Ltd., Tokyo, 2013.

|

|

8

|

Argilés JM, Busquets S and López-Soriano

FJ: Cancer cachexia, a clinical challenge. Curr Opin Oncol.

31:286–290. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Nakanishi Y, Higuchi J, Honda N and Komura

N: Pharmacological profile and clinical efficacy of anamorelin HCl

(ADLUMIZ®Tablets), the first orally available drug for

cancer cachexia with ghrelin-like action in Japan. Nihon Yakurigaku

Zasshi. 156:370–381. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M,

Matsuo H and Kangawa K: Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing

acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 402:656–660. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chen HY, Trumbauer ME, Chen AS, Weingarth

DT, Adams JR, Frazier EG, Shen Z, Marsh DJ, Feighner SD, Guan XM,

et al: Orexigenic action of peripheral ghrelin is mediated by

neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein. Endocrinology.

145:2607–2612. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Velloso CP: Regulation of muscle mass by

growth hormone and IGF-I. Br J Pharmacol. 154:557–568.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Li WG, Gavrila D, Liu X, Wang L,

Gunnlaugsson S, Stoll LL, McCormick ML, Sigmund CD, Tang C and

Weintraub NL: Ghrelin inhibits proinflammatory responses and

nuclear factor-kappaB activation in human endothelial cells.

Circulation. 109:2221–2226. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Chen JA, Splenser A, Guillory B, Luo J,

Mendiratta M, Belinova B, Halder T, Zhang G, Li YP and Garcia JM:

Ghrelin prevents tumour- and cisplatin-induced muscle wasting:

Characterization of multiple mechanisms involved. J Cachexia

Sarcopenia Muscle. 6:132–143. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Wakabayashi H, Arai H and Inui A:

Anamorelin in Japanese patients with cancer cachexia: An update.

Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 17:162–167. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Naito T, Uchino J, Kojima T, Matano Y,

Minato K, Tanaka K, Mizukami T, Atagi S, Higashiguchi T, Muro K, et

al: A multicenter, open-label, single-arm study of anamorelin

(ONO-7643) in patients with cancer cachexia and low body mass

index. Cancer. 128:2025–2035. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

de Paula Pantano N, Paiva BSR, Hui D and

Paiva CE: Validation of the modified Glasgow prognostic score in

advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care. J Pain Symptom

Manage. 51:270–277. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Takeda T, Sasaki T, Okamoto T, Fukuda K,

Hirai T, Yamada M, Nakagawa H, Mie T, Furukawa T, Kasuga A, et al:

Efficacy of amamorelin in advanced pancreatic cancer patients with

a poor performance status. Intern Med. 64:351–358. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Tsukiyama I, Iwata T, Takeuchi T, Kato RI,

Sakuma M, Tsukiyama S, Kato M, Ikeda Y, Ohashi W, Kubo A, et al:

Factors associated with early discontinuation of anamorelin in

patients with cancer-associated cachexia. Support Care Cancer.

31(621)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yin Y and Zhang W: The role of ghrelin in

senescence: A mini-review. Gerontology. 62:155–162. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Takiguchi S, Takata A, Murakami K,

Miyazaki Y, Yanagimoto Y, Kurokawa Y, Takahashi T, Mori M and Doki

Y: Clinical application of ghrelin administration for gastric

cancer patients undergoing gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 17:200–205.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ouyang X, Dang Y, Zhang F and Huang Q: Low

serum albumin correlates with poor survival in gastric cancer

patients. Clin Lab. 64:239–245. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Takayama K, Kojima A, Honda C, Nakayama M,

Kanemata S, Endo T and Muro K: Real-world safety and effectiveness

of anamorelin for cancer cachexia: Interim analysis of

post-marketing surveillance in Japan. Cancer Med.

13(e7170)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|