Introduction

There is a worldwide increase in the incidence of

colorectal cancer and diverticulosis on the left side of the colon.

Hartmann's procedure (HP) is a surgery used to reduce the risk of

postoperative complications in patients undergoing surgery for

left-sided colonic benign disease, patients with colorectal cancer

who have oncologic emergencies, and those with poor general

condition (frail or older adults) (1-3).

Although HP remains an important surgical option, the achievement

of stoma reversal is significantly lower than that of stoma closure

after primary anastomosis (4). A

permanent stoma significantly impairs patient quality of life and

increases medical costs. Furthermore, previous studies have

demonstrated that the achievement of stoma reversal is

significantly different between benign and malignant diseases

(5,6). The reason for this may be that the

long-term course after stoma reversal varies depending on the

underlying disease conditions.

Colostomy reversal after HP is considered a

challenging surgery with a high risk of anastomotic complications

and mortality (7,8). However, even in successful reversal

cases in which the patient is stoma-free, several complications,

such as cancer recurrence or death, can occur during follow-up,

particularly in case of malignant diseases. Only a few studies have

examined the long-term outcomes after reversal (9,10).

To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated long-term

outcomes after reversal in benign and malignant diseases.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to compare the

achievement of stoma reversal and examine the long-term outcomes

after reversal between benign and malignant disease groups in a

cohort from a single institution.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient

population

This retrospective observational study was conducted

at the Hakodate Municipal Hospital (Hakodate, Japan). The study and

manuscript adheres to the STROBE guidelines for observational

studies. Patients who underwent HP for any disease between January

2005 and December 2021 in our hospital were included. HP was

defined as the removal of a damaged colonic segment with the

abandonment of the sutured distal colon stump and creation of an

end colostomy in the upstream colonic segment (3). We excluded patients who underwent HP

for gynecological or recurrent malignant diseases (because there

were no cases of colostomy reversal) and died during

hospitalization after HP. The patients were classified into benign

and malignant disease groups according to the disease for which HP

was indicated. In our department, both colorectal and general

surgeons performed HP, and indications for colostomy reversal after

HP were good patient condition and no major pelvic complications

after HP (such as dehiscence of the rectal stump). The following

situations were also considered in cases of malignant disease: no

disease recurrence for at least 6 months from HP after adjuvant

chemotherapy in patients who underwent curative cancer surgery, and

no disease for which systemic treatment was being received in

patients with distant metastasis. After HP, patients with malignant

disease were regularly followed up for treatment or examination.

Conversely, patients with benign disease were followed up by

irregular visits alone for various reasons (including visit for any

other disease and visit by emergency) or were contacted during the

anorectal function survey.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was the difference in

stoma-reversal rate between benign and malignant diseases. The

secondary endpoints were predictive factors for the achievement of

stoma reversal and stoma-free survival (SFS) and anorectal function

after reversal in patients with benign and malignant diseases.

Data collection and assessments

Data on patient characteristics collected from the

medical records included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American

Society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASA-PS), Charlson

comorbidity index (CCI), indication for HP, type of surgery for HP,

surgical approach for HP, adjacent organ resection during HP,

length of residual stump, postoperative complications

(intra-abdominal abscess and dehiscence of residual stump), and

discharge location. Surgical outcomes of stoma reversal included

the surgical approach, anastomotic method, and diverting loop

ileostomy. Data on postoperative complications and mortality rates

were also collected. The calculation of CCI has been previously

reported (11). The CCI cut-off

values for predicting stoma reversal were determined based on the

receiver operating characteristic curves in the benign disease and

malignant disease groups separately. The CCI was classified into

low and high scores according to the cut-off values (4 and 6 points

in benign and malignant diseases, respectively). Residual stumps

were classified as located above the sacral promontory, between the

sacral promontory and peritoneal reflection, and below the

peritoneal reflection. Postoperative complications were assessed

using the Clavien-Dindo classification (12). The observational period was

calculated from HP or stoma reversal to the last follow-up date.

The SFS rate was measured based on the time from reversal.

Anorectal function was evaluated before HP (pre-HP)

and after reversal (post-reversal) using the low anterior resection

syndrome (LARS) score, a categorical scoring system. The patients'

LARS scores were graded into three categories: No LARS (LARS score

<20), minor LARS (LARS score between 21 and 29) and major LARS

(LARS score >20). The survey targeted patients who were alive in

September 2022. Pre-HP function was retraced and assessed at the

time of the survey.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are summarized as frequencies

and percentages. Continuous variables are summarized as mean ±

standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Between-group

comparisons were performed using Welch's t-test for continuous

variables or Mann-Whitney U test for categorical variables. In

addition, Fisher's exact test was used to compare the frequencies

of categorical variables. Comparisons of two measurements between

pre-HP and post-reversal functions from the same patient were

performed using Wilcoxon signed rank test. Comparisons between the

three groups were performed using Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test. The

cumulative stoma-reversal rate was estimated and compared between

the groups using the Gray test. Predictive factors for stoma

reversal were analyzed using univariate and multivariate analyses

with the Fine-Gray regression model. Variables with P<0.05 in

the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate analysis

as covariates. The SFS was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method

and compared between the groups using the log-rank test. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (version 1.61;

Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan),

a graphical user interface for R (version 4.2.2; The R Foundation

for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and a modified version

of R Commander (version 2.8-0) designed to add statistical

functions frequently used in biostatistics (13).

Results

Patient flow and characteristics

between the benign and malignant disease groups

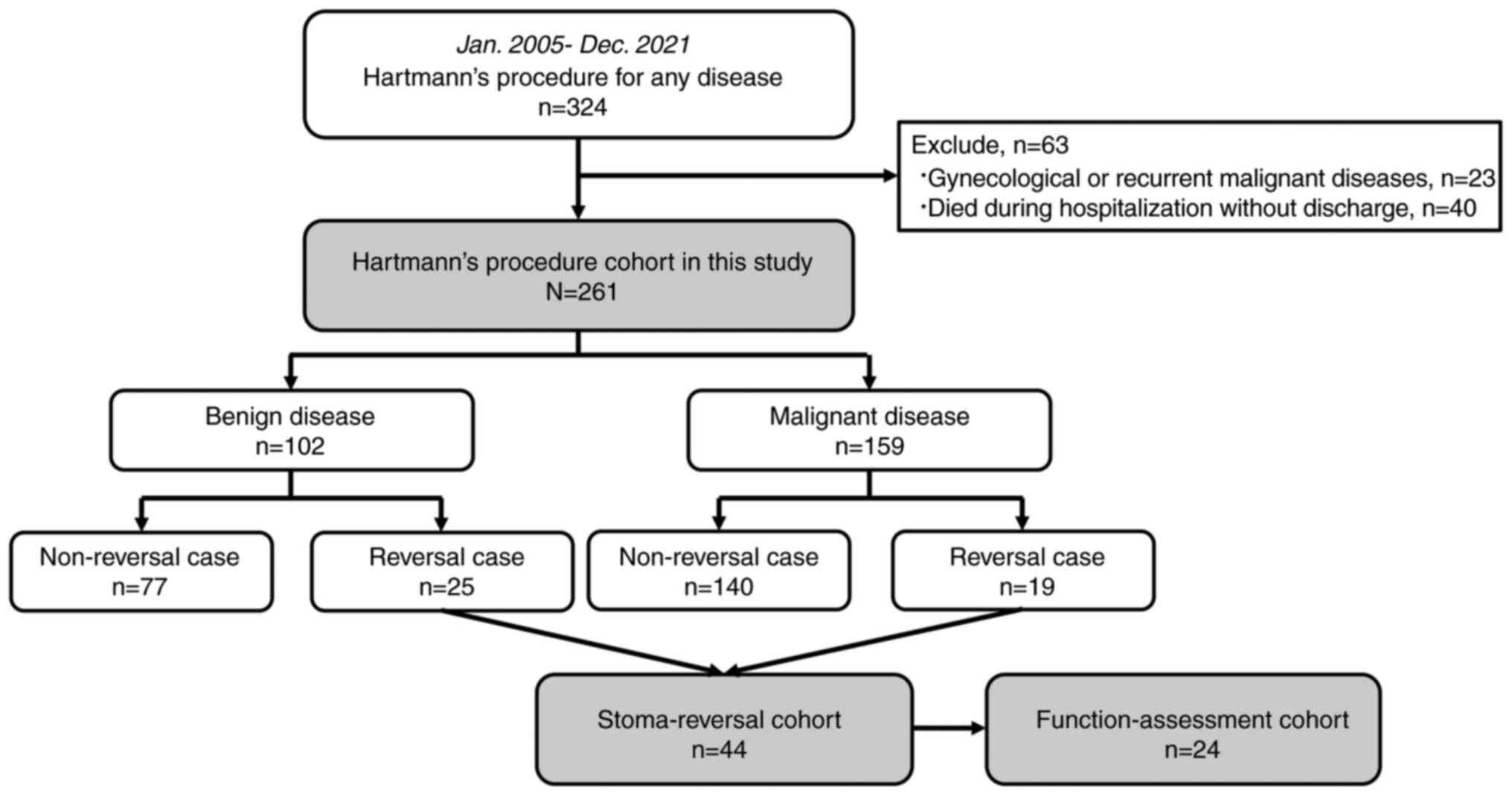

A total of 324 patients who underwent HP for any

disease between January 2005 and December 2021 were eligible for

the study. However, 23 patients who underwent HP for gynecological

or recurrent malignant diseases and 40 who died during

hospitalization were excluded. Eventually, 261 patients were

included in this study. Among these, 102 and 159 patients were

included in the benign disease and malignant disease groups,

respectively. The stoma reversal was performed in 44 patients

(16.9%). Among them, 24 (77.4%) of the 31 survivors in September

2022 underwent assessments of anorectal function. The patient

flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. The

characteristics of the 261 patients are presented in Table I. There were significant

differences in sex, ASA-PS, type of surgery for HP, surgical

approach for HP, adjacent organs resection during HP, length of the

residual stump, and discharge location between the benign and

malignant disease groups.

| Table IComparison of patient characteristics

between the benign and malignant disease groups. |

Table I

Comparison of patient characteristics

between the benign and malignant disease groups.

| Characteristic | Hartmann's procedure

cohort (n=261) | Benign disease

(n=102) | Malignant disease

(n=159) | P-value (benign

disease vs. malignant disease) |

|---|

| Mean age, years

(SD) | 72.9 (12.3) | 74.0 (13.3) | 72.2 (11.6) | 0.249 |

| Sex, n (%) | | | | 0.043 |

|

Male | 141 (54.0) | 47 (46.1) | 94 (59.1) | |

|

Female | 120 (46.0) | 55 (53.9) | 65 (40.9) | |

| Mean BMI,

kg/m2 (SD) | 21.2 (4.0) | 21.4 (4.3) | 21.1 (3.7) | 0.580 |

| No data for BMI, n

(%) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| ASA-PS, n (%) | | | | <0.001 |

|

ASA-I | 10 (3.8) | 3 (2.9) | 7 (4.4) | |

|

ASA-II | 84 (32.2) | 14 (13.7) | 70 (44.0) | |

|

ASA-III | 131 (50.2) | 62 (60.8) | 69 (43.4) | |

|

ASA-IV | 32 (12.3) | 19 (18.6) | 13 (8.2) | |

|

ASA-V | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | |

|

No data | 3 (1.2) | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Median Charlson

comorbidity indexa

(IQR) | 7 (5-9) | 5 (4-6) | 8 (6-10) | <0.001 |

|

Low score, n

(%)b | 81 (31.0) | 34 (33.3) | 47 (29.6) | 0.584 |

|

High score,

n (%)c | 180 (69.0) | 68 (66.7) | 112 (70.4) | |

| Type of surgery for

HP, n (%) | | | | <0.001 |

|

Elective | 118 (45.2) | 10 (9.8) | 108 (67.9) | |

|

Urgent | 143 (54.8) | 92 (90.2) | 51 (32.1) | |

| Surgical approach

for HP, n (%) | | | | 0.024 |

|

Open | 144 (55.2) | 63 (61.8) | 81 (50.9) | |

|

Laparoscopic | 99 (37.9) | 29 (28.4) | 70 (44.0) | |

|

Conversion | 18 (6.9) | 10 (9.8) | 8 (5.0) | |

| Adjacent organs

resection during HP, n (%) | 65 (24.9) | 6 (5.9) | 59 (37.1) | <0.001 |

| Length of residual

stump, n (%) | | | | <0.001 |

|

Above sacral

promontory | 26 (10.0) | 18 (17.6) | 8 (5.0) | |

|

Between

sacral promontory and peritoneal reflection | 203 (77.8) | 79 (77.5) | 124 (78.0) | |

|

Below

peritoneal reflection | 32 (12.3) | 5 (4.9) | 27 (17.0) | |

| Postoperative

complication, n (%) | | | | |

|

Intra-abdominal

abscess | 20 (7.7) | 11 (10.8) | 9 (5.7) | 0.154 |

|

Dehiscense | 8 (3.1) | 2 (2.0) | 6 (3.8) | 0.488 |

| Discharge location,

n (%) | | | | <0.001 |

|

Home | 144 (55.2) | 39 (38.2) | 105 (66.0) | |

|

Different

hospital | 109 (41.8) | 59 (57.8) | 50 (31.4) | |

|

Others | 8 (3.1) | 4 (3.9) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Mean follow-up from

HP, months (SD) | 40.8 [40.1] | 45.8 [45.4] | 37.7 [36.0] | 0.130 |

Predictive factors for stoma reversal

and cumulative stoma-reversal rate between the benign and malignant

disease groups

The results of univariate and multivariate analyses

of the predictive factors for stoma reversal are summarized in

Table II. CCI, indication for HP,

type of surgery for HP, and discharge location were independent

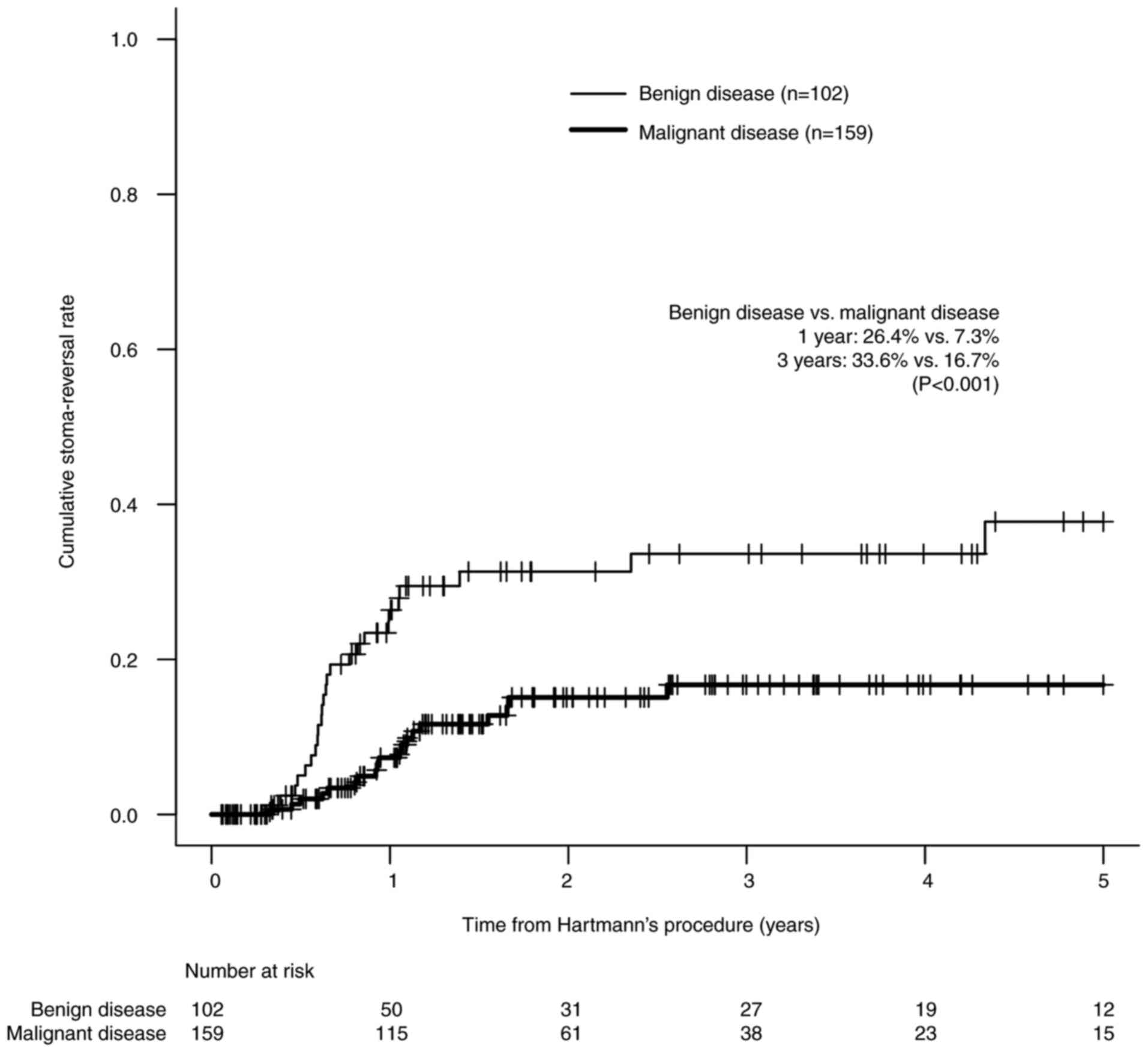

predictive factors for stoma reversal. Fig. 2 shows that the cumulative

stoma-reversal rate in the malignant disease group was

significantly lower than that in the benign disease group (26.4%

vs. 7.3% at 1 year after HP and 33.6% vs. 16.7% at 3 years after

HP, P<0.001 by the Gray test). The indications for HP,

stoma-reversal rate, and time-to-reversal are shown in Table III. The most common indications

for HP were diverticular disease and colorectal cancer with

obstruction in patients with benign and malignant diseases,

respectively. The mean time-to-reversal for benign and malignant

diseases were 11.0 and 12.6 months, respectively (P=0.526). Among

159 patients with malignant diseases, very few patients with

distant metastasis underwent stoma reversal compared to those

without distant metastasis (4.5% vs. 17.2%, P=0.023). External

causes had a high reversal rate (57.1%) regardless of the primary

cause.

| Table IIPredictive factors associated with

stoma reversal in univariate and multivariate analyses. |

Table II

Predictive factors associated with

stoma reversal in univariate and multivariate analyses.

| | Univariate | Multivariate |

|---|

| Variable | n (%) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age | | | | | |

|

<70

years | 93 (35.6) | 1.615

(0.893-2.922) | 0.110 | | |

|

>70

years | 168 (64.4) | Reference | | | |

| Sex | | | | | |

|

Male | 141 (54.0) | 1.244

(0.688-2.251) | 0.470 | | |

|

Female | 120 (46.0) | Reference | | | |

| BMI | | | | | |

|

BMI >21

kg/m2 | 132 (50.6) | 1.088

(0.605-1.957) | 0.780 | | |

|

BMI <21

kg/m2 and no data | 129 (49.4) | Reference | | | |

| ASA-PS | | | | | |

|

ASA

>III | 164 (62.8) | 1.034

(0.564-1.895) | 0.910 | | |

|

ASA-I or II

and no data | 97 (37.2) | Reference | | | |

| Charlson

comorbidity index | | | | | |

|

Low

score | 81 (31.0) | 6.131

(3.117-12.06) | <0.001 | 3.684

(1.720-7.888) | <0.001 |

|

High

score | 180 (69.0) | Reference | | Reference | |

| Indication for

HP | | | | | |

|

Malignant

disease | 159 (60.9) | 0.363

(0.201-0.656) | <0.001 | 0.523

(0.278-0.983) | 0.044 |

|

Benign

disease | 102 (39.1) | Reference | | Reference | |

| Type of surgery for

HP | | | | | |

|

Urgent | 143 (54.8) | 5.755

(2.588-12.79) | <0.001 | 4.121

(1.602-10.60) | 0.003 |

|

Elective | 118 (45.2) | Reference | | Reference | |

| Surgical approach

for HP | | | | | |

|

Laparoscopic | 99 (37.9) | 0.470

(0.237-0.933) | 0.031 | 1.113

(0.500-2.478) | 0.790 |

|

Open and

conversion | 162 (62.1) | Reference | | Reference | |

| Adjacent organs

resection during HP | | | | | |

|

Yes | 65 (24.9) | 0.638

(0.304-1.343) | 0.240 | | |

|

No | 196 (75.1) | Reference | | | |

| Length of residual

stump | | | | | |

|

Below

peritoneal reflection | 32 (12.3) | 0.634

(0.220-1.830) | 0.400 | | |

|

Above

peritoneal reflection | 229 (87.7) | Reference | | | |

| Postoperative

complicationa | | | | | |

|

Yes | 23 (8.8) | 0.719

(0.235-2.202) | 0.560 | | |

|

No | 238 (91.2) | Reference | | | |

| Discharge

location | | | | | |

|

Home | 144 (55.2) | 4.280

(1.823-10.05) | <0.001 | 4.454

(1.859-10.67) | <0.001 |

|

Different

hospital and others | 117 (44.8) | Reference | | Reference | |

| Table IIIStoma-reversal rates and intervals

depending on indication for Hartmann's procedure. |

Table III

Stoma-reversal rates and intervals

depending on indication for Hartmann's procedure.

| Indication for

Hartmann's procedure | n (%) | Reversal rate n

(%) | Mean

time-to-reversal, months (SD) |

|---|

| Benign disease | 102(100) | 25/102 (24.5) | 11.0 (9.9) |

|

Diverticular

disease | 45 (44.1) | 12/45 (26.7) | 11.8 (13.2) |

|

Stercoral

perforation | 16 (15.7) | 2/16 (12.5) | 8.9 (4.3) |

|

Bowel

ischemia | 14 (13.7) | 3/14 (21.4) | 9.5 (2.6) |

|

Others | 17 (16.7) | 2/17 (11.8) | 17.8 (14.7) |

|

External

causes (trauma, iatrogenic perforation, operative

complication) | 10 (9.8) | 6/10 (60.0) | 8.6 (2.4) |

| Malignant

disease | 159(100) | 19/159 (11.9) | 12.6 (6.3) |

|

Colorectal

cancer with obstruction | 58 (36.5) | 9/58 (15.5) | 11.1 (4.7) |

|

Colorectal

cancer with perforation | 53 (33.3) | 8/53 (15.1) | 13.3 (8.3) |

|

Others | 44 (27.7) | 0/44 (0) | NA |

|

External

causes (operative complication) | 4 (2.5) | 2/4 (50.0) | 16.3 (3.2) |

| Status of malignant

disease | | | |

|

Absence of

distant metastasis | 93 (58.5) | 16/93 (17.2) | 12.5 (6.9) |

|

Presence of

distant metastasis | 66 (41.5) | 3/66 (4.5) | 12.8 (1.5) |

Surgical outcomes of stoma reversal

and stoma-free survival after reversal

The surgical outcomes in the 44 patients who

underwent stoma reversal are shown in Table IV. The laparoscopic approach was

the most common surgical approach in the benign disease group, and

open surgery the most common strategy in the malignant disease

group. The length of the residual stump, anastomotic method,

diverting stoma, postoperative complication grade, mortality rate,

and duration of postoperative follow-up were not significantly

different between the benign and malignant disease groups. One

patient with diverting loop ileostomy during reversal underwent

ileostomy closure approximately 4 months after colostomy reversal.

Owing to anastomotic complications on day 1 after reversal, one of

the 25 patients with benign disease underwent stoma recreation

(second Hartmann's operation). However, the patient's stoma was not

reversed. Among the 19 patients with malignant disease, 1 underwent

stoma recreation (ileostomy) because of anastomotic complications

on day 7 after reversal, and the stoma was closed approximately 3

years after the recreation. Three patients underwent stoma

recreation owing to cancer recurrence in the pelvis (transverse

colostomy for peritoneal recurrence in one patient with stage III

cancer with a 7.9-month interval to reversal, a second Hartmann's

operation for local recurrence in a patient with stage II cancer

with an 11.3-month interval, and Mile's operation for local

recurrence in a patient with stage IV cancer with an interval of 10

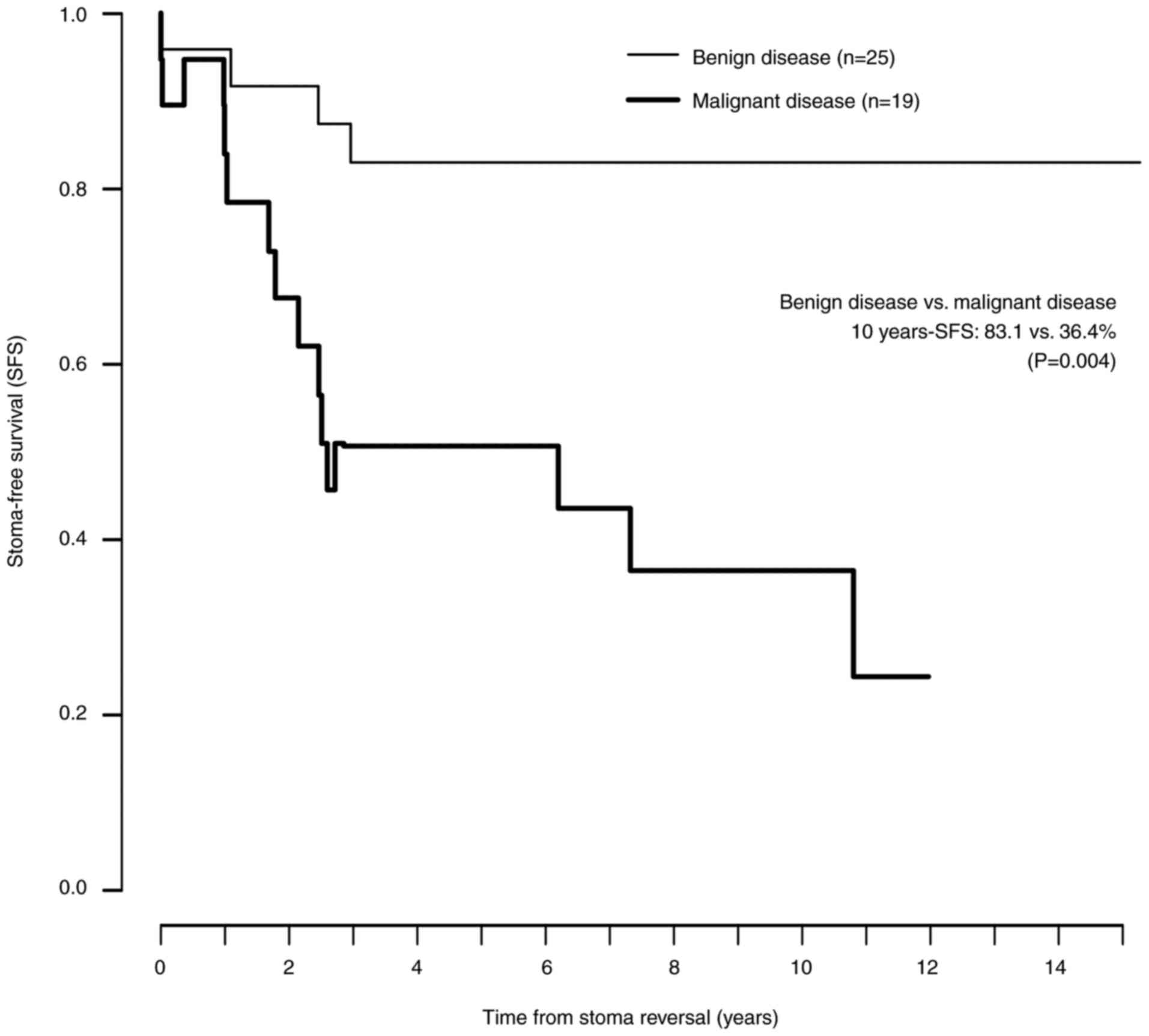

months). Their stomas became permanent. Fig. 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for

SFS after reversal in the benign and malignant disease groups. The

SFS was significantly decreased in the malignant disease group with

time elapsing from reversal, compared with the benign disease group

(benign disease vs. malignant disease using the log-rank test,

1-year SFS: 96.0% vs. 83.9%, P=0.214; 3-year SFS: 83.1% vs. 50.6%,

P=0.036; 5-year SFS: 83.1% vs. 50.6%, P=0.036, 10-year SFS: 83.1%

vs. 36.4%, P=0.004).

| Table IVSurgical outcomes of stoma

reversal. |

Table IV

Surgical outcomes of stoma

reversal.

| Variable | Stoma-reversal

cohort (n=44) | Benign disease

(n=25) | Malignant disease

(n=19) | P-value (benign

disease vs. malignant disease) |

|---|

| Surgical approach

for stoma reversal, n (%) | | | | 0.034 |

|

Open | 17 (38.6) | 6 (24.0) | 11 (57.9) | |

|

Laparoscopic | 25 (56.8) | 18 (72.0) | 7 (36.8) | |

|

Conversion | 2 (4.6) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Length of residual

stump, n (%) | | | | 0.116 |

|

Above sacral

promontory | 13 (29.6) | 10 (40.0) | 3 (15.8) | |

|

Between

sacral promontory and peritoneal reflection | 27 (61.4) | 12 (48.0) | 15 (78.9) | |

|

Below

peritoneal reflection | 4 (9.1) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (5.3) | |

| Anastomotic method,

n (%) | | | | 0.766 |

|

Circular

stapler | 34 (77.3) | 19 (76.0) | 15 (78.9) | |

|

Linear

stapler | 4 (9.1) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (5.3) | |

|

Hand-sewn | 3 (6.8) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (5.3) | |

|

No data | 3 (6.8) | 1 (4.0) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Diverting loop

ileostomy, n (%) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.432 |

| Postoperative

complication (<30 days), n (%) | | | | |

|

All

grade | 13 (29.5) | 7 (28.0) | 6 (31.6) | >0.999 |

|

Major

complication (CD>III) | 9 (20.5) | 4 (16.0) | 5 (26.3) | 0.467 |

|

Anastomotic

complication | 3 (6.8) | 2 (8.0) | 1 (5.3) | >0.999 |

| 30-day mortality, n

(%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Mean follow-up from

stoma reversal, months (SD) | 74.0 (46.4) | 81.2 (45.1) | 64.5 (47.7) | 0.247 |

Assessments of anorectal function

The post-reversal LARS scores of the 24 patients

were significantly worse than their pre-HP scores (P=0.017).

Post-reversal minor LARS occurred in four patients (16.7%), and

post-reversal major LARS in four patients (16.7%). The

post-reversal LARS scores and the occurrence of post-reversal LARS

were not significantly different between the benign and malignant

disease groups. Subsequent analysis based on the length of the

residual stump revealed that post-reversal LARS scores were

significantly lower when the residual stump was short by

Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test (P=0.023). Residual stumps below the

peritoneal reflection were associated with major LARS. The results

of anorectal function are summarized in Table V.

| Table VAssessments of anorectal

function. |

Table V

Assessments of anorectal

function.

| | Indication for

Hartmann's procedure | Length of residual

stump |

|---|

| Variable | Function-assessment

cohort (n=24) | Benign disease

(n=17) | Malignant disease

(n=7) | P-value (benign

disease vs. malignant disease) | Above sacral

promontory (n=5) | Between sacral

promontory and peritoneal reflection (n=17) | Below peritoneal

reflection (n=2) | P-value (among

three groups according to length of residual stump) |

|---|

| Median LARS score

(IQR) | | | | | | | | |

|

Pre-HP | 6 (0-14) | 7 (5-14) | 5 (0-16.5) | 0.747a | 5 (0-5) | 9 (0-20) | 9.5

(7.25-11.75) | 0.403b |

|

Post-reversal | 11 (6.5-26.75) | 11 (7-20) | 23 (5.5-27.5) | 0.725a | 5 (5-7) | 11 (9-26) | 37.5

(36.75-38.25) | 0.023b |

|

P-value

(pre-HP vs. post-reversal) | 0.017c | 0.120c | 0.059c | |

>0.999c | 0.066c | 0.500c | |

| Post-reversal | | | | 0.118d | | | | 0.043d |

| LARS, n (%) | | | | | | | | |

|

No LARS | 16 (66.7) | 13 (76.5) | 3 (42.9) | | 5(100) | 11 (64.7) | 0 (0) | |

|

Minor

LARS | 4 (16.7) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (42.9) | | 0 (0) | 4 (23.5) | 0 (0) | |

|

Major

LARS | 4 (16.7) | 3 (17.6) | 1 (14.3) | | 0 (0) | 2 (11.8) | 2(100) | |

Discussion

This study revealed that malignant disease was an

independent significant predictive factor for stoma reversal in the

multivariate analysis. Moreover, the cumulative stoma-reversal rate

was lower for malignant than for benign disease, although After

reversal, SFS was significantly reduced in the malignant disease

group compared to benign disease group as the time from reversal

elapsed. The was comparable in terms of functional outcomes between

the groups.

The HP remains an important surgical option due to

the increasing incidence of colorectal cancer and diverticulosis of

the left colon worldwide and in Asian countries, respectively

(14). The rate of stoma closure

was reported to be lower after HP than after primary anastomosis

(4). In particular, the stoma

closure rate after HP was different between benign and malignant

diseases (5,6). Our findings showed that the

cumulative stoma-reversal rate was significantly different between

benign and malignant diseases. Additionally, among malignant

diseases, advanced cancers with distant metastasis have

significantly lower rates of stoma reversal. This may be because

the timing of stoma reversal is missed owing to ongoing treatment

for distant metastasis after HP.

Furthermore, our findings demonstrated that low CCI,

urgent surgery, and home discharge were independently associated

with a higher stoma-reversal rate. The CCI score reflects the age

and comorbidities of the individual and represents their background

(11). Royo-Aznar et al

(5) reported that patients with a

low CCI had a higher rate of stoma reversal. In this study, the

achievement of stoma reversal was not significantly associated with

ASA-PS at the time of HP while it was significantly associated with

CCI. If patients with severe systemic disease at the time of HP

(high ASA-PS) recovered, had a low CCI, and were discharged home,

they had a good chance of reversal. Urgent surgery meant that HP

had to be performed and it was a lifesaving procedure. In such

cases, the patient has a good chance of reversal if they recover.

Our data could help surgeons provide accurate information for

patients and their families about the prospect of colostomy closure

or a permanent stoma prior to obtaining informed consent.

The colostomy reversal after HP is a difficult

surgery with a high risk of anastomotic complications and mortality

(7,8). However, with the introduction of

minimally invasive techniques (14-18),

the incidence of complications after reversal has lowered (19-22).

Therefore, the indications of colostomy reversal after HP can now

be expanded. Although there are many reports on short-term outcomes

after reversal (22,23), only a few studies have examined its

long-term outcomes (9,10). We speculate that the long-term

follow-up of patients after reversal may result in the

identification of complications such as cancer recurrence in

patients with malignant disease and anorectal disorders. These

issues require further investigation.

Because patients with malignant disease undergoing

HP often have colorectal obstruction or perforation, subsequent

disease recurrence may occur even if the reversal is successful

(24,25). In this study, stoma recreation was

required in three cases of cancer recurrence in the pelvis. For

malignant diseases, an appropriate indication for colostomy

reversal, such as setting an adequate interval between surgeries,

may avoid unnecessary challenging surgery. As mentioned earlier, in

our center, colostomy reversal after HP is indicated when there is

no disease recurrence for at least 6 months post-HP and after

adjuvant chemotherapy in patients who underwent curative cancer

surgery, and there is no disease progression in patients with

distant metastasis controlled by systemic therapy. Although there

was no significant difference, the interval from HP to reversal in

the 3 patients who underwent stoma recreation owing to cancer

recurrence was shorter than that in the remaining 16 patients in

the malignant disease group (9.6 months vs. 13.1 months, P=0.090).

A previous study reported the time-to-reversal of 282 days (9.3

months) for malignant disease (6).

Determining the appropriate interval for reversal could be the

object of future research. Additionally, it is important to obtain

informed consent before stoma reversal in patients with malignant

disease owing to the risk of recurrence.

Few studies have examined anorectal function after

reversal. In their study of 64 patients with colostomy reversal,

Van Hoof et al (10)

reported that 15.6 and 17.2% of patients had minor LARS and major

LARS, respectively. Caille et al (9) stated that among 21 patients who

underwent reversal after HP due to failure of the previous

anastomosis, 33.3% reported minor LARS and 23.8% reported major

LARS. In our study, 16.7% of 24 patients reported minor LARS and

16.7% reported major LARS. This result is comparable to those shown

in previous studies. Furthermore, the present study revealed no

significant differences in anorectal function between those with

benign and malignant diseases. However, a short residual rectal

stump could be associated with poor function. Although there were

only two patients with residual stumps below the peritoneal

reflection, they experienced major LARS. Interestingly, a previous

study demonstrated that the length of the rectal stump did not

differ significantly among patients with no, minor, and major LARS

(10). Further studies will be

required to investigate the association between anorectal function

and the length of residual stump. Based on our finding of

predictive factors for stoma reversal, we suggest that

interventions such as pelvic floor muscle exercises should be

considered before reversal for patients with a high likelihood of

reversal and a short residual stump.

This study had some limitations. First, we

retrospectively collected data from the surgical database and

medical records in a single center. Second, the number of

participants was small and the rate of stoma reversal was low to

examine each variable related to the outcomes. Multicenter studies

with large samples and minimal bias are required for more reliable

statistical analyses. Third, due to the retrospective nature of

this study, it was difficult to obtain data on whether patients

desired stoma reversal. Some patients may have been satisfied with

a permanent stoma and therefore did not seek reversal, which could

have resulted in an underestimation of the stoma reversal rate.

Fourth, both colorectal and general surgeons performed HP, and

stoma reversal decisions were primarily based on patient condition

rather than surgeon specialty. However, colorectal surgeons

predominantly treated malignant diseases, and their surgical

strategies may have influenced the observed trends. Fifth, the time

between stoma reversal and the survey for post-reversal anorectal

function varied from case to case, which may have influenced the

functional results. Sixth, because pre-HP anorectal function was

retraced and assessed at the time of the survey, the actual

function may not have been accurately represented. Further

prospective studies are required to overcome these limitations.

Seventh, follow-up methods differed between benign and malignant

diseases. In particular, patients with benign diseases were not

followed up regularly. This may underestimate the stoma-reversal

rate in patients with benign diseases. However, because the

follow-up period for benign diseases was relatively long and there

was no significant difference in the follow-up period, we believe

that this impact was not so large. The reason for this is that our

hospital is located in the southern area of Hokkaido, which has few

healthcare resources, and patients have few opportunities to visit

other medical institutions.

In conclusion, our findings indicated that the

stoma-reversal rate and SFS after reversal could be worse in

patients with malignant disease than in those with benign disease,

although anorectal function after reversal was not significantly

different. The postoperative long-term course of HP may vary

between patients according to the indication for HP. Enforcement of

HPs should be carefully considered, taking these circumstances into

account.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Yohei

Kawasaki, Ph.D. (Institute for Assistance of Academic and

Education) for the advice on statistical analysis.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the Japanese Society for

the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant no. 23K19492).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KIm, HK, AS, KS, KIt, TF, KIc, TO, DY, YT, MU, MK

and KN conceptualized and designed the study. KIm and HK confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. KIm wrote the manuscript and

performed the statistical analyses. KIm, HK, AS, KS, KIt, TF, KIc,

TO, DY, YT, MU, MK and KN performed the operations and collected

clinicopathological data. KN supervised the study. KIm, HK, AS, KS,

KIt, TF, KIc, TO, DY, YT, MU, MK and KN interpreted the results and

wrote the report. All authors read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Human Research

Ethics Committee of Hakodate Municipal Hospital (Hakodate, Japan;

approval nos. 2021-84 and 2022-228). Furthermore, the study was

conducted in accordance with the tenets of the 1964 Declaration of

Helsinki and its later amendments. All patients gave their consent

through the opt-out method.

Patient consent for publication

All patients gave their consent through the opt-out

method.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Authors' information

ORCID IDs: KEN IMAIZUMI, 0000-0002-7751-6270; AYA

SATO, 0000-0002-4231-2315; KENTARO SATO, 0000-0002-1765-7477;

KENTARO ICHIMURA, 0000-0002-2838-4240.

References

|

1

|

Albarran SA, Simoens Ch, Van De Winkel N,

da Costa PM and Thill V: Restoration of digestive continuity after

Hartmann's procedure: ASA score is a predictive factor for risk of

postoperative complications. Acta Chir Belg. 109:714–719.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Moro-Valdezate D, Royo-Aznar A,

Martín-Arévalo J, Pla-Martí V, García-Botello S, León-Espinoza C,

Fernández-Moreno MC, Espín-Basany E and Espí-Macías A: Outcomes of

Hartmann's procedure and subsequent intestinal restoration. Which

patients are most likely to undergo reversal? Am J Surg.

218:918–927. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Christou N, Rivaille T, Maulat C, Taibi A,

Fredon F, Bouvier S, Fabre A, Derbal S, Durand-Fontanier S, Valleix

D, et al: Identification of risk factors for morbidity and

mortality after Hartmann's reversal surgery-a retrospective study

from two French centers. Sci Rep. 10(3643)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Edomskis PP, Hoek VT, Stark PW, Lambrichts

DPV, Draaisma WA, Consten ECJ, Bemelman WA and Lange JF: LADIES

trial collaborators. Hartmann's procedure versus sigmoidectomy with

primary anastomosis for perforated diverticulitis with purulent or

fecal peritonitis: Three-year follow-up of a randomised controlled

trial. Int J Surg. 98(106221)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Royo-Aznar A, Moro-Valdezate D,

Martín-Arévalo J, Pla-Martí V, García-Botello S, Espín-Basany E and

Espí-Macías A: Reversal of Hartmann's procedure: A single-centre

experience of 533 consecutive cases. Colorectal Dis. 20:631–638.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Katsura M, Fukuma S, Chida K, Saegusa Y,

Kanda S, Kawasaki K, Tsuzuki Y and Ie M: Which factors influence

the decision to perform Hartmann's reversal in various causative

disease situations? A retrospective cohort study between 2006 and

2021. Colorectal Dis. 25:305–314. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Banerjee S, Leather AJ, Rennie JA, Samano

N, Gonzalez JG and Papagrigoriadis S: Feasibility and morbidity of

reversal of Hartmann's. Colorectal Dis. 7:454–459. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Toro A, Ardiri A, Mannino M, Politi A, Di

Stefano A, Aftab Z, Abdelaal A, Arcerito MC, Cavallaro A, Cavallaro

M, et al: Laparoscopic reversal of Hartmann's procedure: State of

the art 20 years after the first reported case. Gastroent Res

Pract. 2014(530140)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Caille C, Collard M, Moszkowicz D, Prost À

la Denise J, Maggiori L and Panis Y: Reversal of Hartmann's

procedure in patients following failed colorectal or coloanal

anastomosis: An analysis of 45 consecutive cases. Colorectal Dis.

22:203–211. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Van Hoof S, Sels T, Patteet E, Hendrickx

T, Van den Broeck S, Hubens G and Komen N: Functional outcome after

Hartmann's reversal surgery using LARS, COREFO & QoL scores. Am

J Surg. 225:341–346. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL and

MacKenzie CR: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in

longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis.

40:373–383. 1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Dindo D, Demartines N and Clavien PA:

Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with

evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey.

Ann Surg. 240:205–213. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kanda Y: Investigation of the freely

available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 48:452–458. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Oh HK, Han EC, Ha HK, Choe EK, Moon SH,

Ryoo SB, Jeong SY and Park KJ: Surgical management of colonic

diverticular disease: Discrepancy between right- and left-sided

diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 20:10115–10120. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Trépanier JS, Arroyave MC, Bravo R,

Jiménez-Toscano M, DeLacy FB, Fernandez-Hevia M and Lacy AM:

Transanal Hartmann's colostomy reversal assisted by laparoscopy:

Outcomes of the first 10 patients. Surg Endosc. 31:4981–4987.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Giuliani G, Formisano G, Milone M, Salaj

A, Salvischiani L and Bianchi PP: Full robotic Hartmann's reversal:

Technical aspects and preliminary experience. Colorectal Dis.

22:1734–1740. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

van Loon YT, Clermonts SHEM, Wasowicz DK

and Zimmerman DDE: Reversal of left-sided colostomy utilizing

single-port laparoscopy: Single-center consolidation of a new

technique. Surg Endosc. 34:332–338. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Sato K, Kasajima H, Yamana D, Imaizumi K

and Nakanishi K: Technique of the Single-port laparoscopic

Hartmann's reversal via the colostomy Site-A video vignette.

Colorectal Dis. 25:1050–1051. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Siddiqui MR, Sajid MS and Baig MK: Open vs

laparoscopic approach for reversal of Hartmann's procedure: A

systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 12:733–741. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

van de Wall BJ, Draaisma WA, Schouten ES,

Broeders IA and Consten EC: Conventional and laparoscopic reversal

of the Hartmann procedure: A review of literature. J Gastrointest

Surg. 14:743–752. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Ng DC, Guarino S, Yau SL, Fok BK, Cheung

HY, Li MK and Tang CN: Laparoscopic reversal of Hartmann's

procedure: Safety and feasibility. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf).

1:149–152. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Horesh N, Lessing Y, Rudnicki Y, Kent I,

Kammar H, Ben-Yaacov A, Dreznik Y, Avital S, Mavor E, Wasserberg N,

et al: Comparison between laparoscopic and open Hartmann's

reversal: Results of a Decade-long multicenter retrospective study.

Surg Endosc. 32:4780–4787. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Pei KY, Davis KA and Zhang Y: Assessing

trends in laparoscopic colostomy reversal and evaluating outcomes

when compared to open procedures. Surg Endosc. 32:695–701.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Chen HS and Sheen-Chen SM: Obstruction and

perforation in colorectal adenocarcinoma: An analysis of prognosis

and current trends. Surgery. 127:370–376. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ogawa K, Miyamoto Y, Harada K, Eto K,

Sawayama H and Iwagam S: Evaluation of clinical outcomes with

propensity-score matching for colorectal cancer presenting as an

oncologic emergency. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 6:523–530.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|