Introduction

Globally, bladder cancer is ranked as the tenth most

frequently diagnosed cancer and is the thirteenth leading cause of

cancer-related mortalities (1,2).

According to 2024 global cancer statistics, the number of new

bladder cancer cases is estimated to have exceeded 600,000

worldwide. The age-standardized incidence rate is ~6.0 cases per

100,000 individuals, showing a slow upward trend. In the same year,

the number of bladder cancer-related deaths is projected to be

~220,000, with a mortality rate maintained at ~2.0 per 100,000

individuals. In recent years, with advancements in diagnostic

technologies and optimization of treatment regimens, the survival

rate of patients with bladder cancer has significantly improved in

some regions with high levels of development (1). The survival rate of bladder cancer

still requires improvement through early detection or targeted

anticancer therapy (3,4). Therefore, early diagnostic biomarkers

and the development of novel therapeutic targets for bladder cancer

remain a focus of our research.

Human plasma proteins exhibit great potential in

disease diagnosis and treatment monitoring, with several successes

achieved over the decades (5,6).

Previous studies have identified various proteins such as membrane

proteins, α-2-macroglobulin, and SPP1 protein, as being associated

with bladder cancer risk (7-9).

However, research on bladder cancer still faces limitations. In

particular, the investigation into proteins associated with the

development and progression of bladder cancer has not been

comprehensively carried out.

Large-scale proteomic investigations have led to the

identification of over 18,000 protein quantitative trait loci

(pQTL) that cover upwards of 4,800 proteins. Genetic variations

related to the levels of multiple plasma proteins have been

identified in previous pQTL studies (10-14).

These research efforts provide valuable data resources for

elucidating the causal role of plasma proteins in the risk of

bladder cancer through Mendelian randomization (MR). MR has been

widely used in studying the pathogenesis and developing preventive

strategies for various cancers, effectively distinguishing the

effects of genetic factors from environmental factors, and aiding

researchers identify potential disease biomarkers and therapeutic

targets (15,16).

In the present study, a proteome-wide MR analysis

was conducted by integrating human plasma proteomics and genomics

data to systematically identify biomarkers associated with bladder

cancer risk. Prognostic models were constructed based on the

identified genes and further validated. Single-cell expression

analysis was performed to detect their expression in bladder cancer

tissues. Finally, druggability evaluation was conducted to explore

their potential as therapeutic targets for bladder cancer.

Materials and methods

Data acquisition

The pQTL data were obtained from the UK Biobank

Pharma Proteomics Project (UKB-PPP) database (http://ukb-ppp.gwas.eu/), with baseline cohort data

selected for this analysis, describing pQTLs from 34,557

participants of European ancestry (17). Outcome data were primarily derived

from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) involving populations

of European ancestry. Summary statistics for the training set were

sourced from the FinnGen biobank database

(finngen_R10_C3_BLADDER_EXALLC), including 2,193 cases and 314,193

controls, while validation set data were retrieved from the EBI

database (ID no. GCST90041858), comprising 762 cases and 455,586

controls. Additionally, RNA-seq data from 431 specimens (19 normal

and 412 tumor samples) were collected from the TCGA database

(https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/), and

bladder cancer-related single-cell data were downloaded from the

GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession no.

GSE129845(18), including 3

samples.

PQTL MR analysis

The UKB-PPP characterized the plasma proteomics

features of UKB participants. GWAS-based proteomics studies

(17) were used to extract

relevant causal relationships in pQTLs from the outcome summary

data, by selecting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

associated with each gene at a genome-wide significance threshold

(P<10-6) as potential instrumental variables (IVs).

While the genome-wide significance threshold is typically set at

P<1x10-8, relaxing it to P<1x10-6 is

considered acceptable in specific scenarios, such as candidate gene

association analysis or fine-mapping analyses including sensitivity

analysis focused on specific loci. When the research objective is

exploratory analysis (rather than strict causal inference), this

threshold increases the number of IVs and avoids missing potential

associations. The LD between SNPs was calculated, retaining only

SNPs with R2<0.001 (clumping window size=10,000 kb), and weak

instruments with F>10 were excluded. Notably, four statistical

methods were used to assess the reliability of causal

relationships: Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW) (19), MR Egger (20), Weighted Median (21), and Weighted Mode (22). If only one SNP was present in the

causal relationship, the Wald ratio method was used. The

reliability of the identified causal relationships was verified

using leave-one-out analysis.

Colocalization analysis

The coloc method (23) was used with expression quantitative

trait locus (eQTL) summary data and bladder cancer GWAS data for

colocalization analysis. The posterior probability was calculated

for the 100-kilobase region around the index SNP. In coloc results,

H3 represents the posterior probability that two traits (gene

expression and bladder cancer) are associated but have different

causal variants; H4 represents the posterior probability that two

traits are associated and share a single causal variant. SNP.PP.H4

>0.95 was used as the colocalization threshold.

GSEA enrichment analysis

GSEA (24) is a

method that utilizes predefined gene sets. It ranks genes according

to the differential expression levels between two sample classes

and then determines whether these predefined gene sets are over,

represented at either the top or bottom of the ranking. In the

present study, GSEA was employed to contrast the signaling pathways

in the high-expression and low-expression groups. This was

performed to investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying key

genes in the 2 patient groups. The number of permutations was

configured as 1,000 and the permutation type was designated as

phenotype.

Tumor mutation burden (TMB) and

microsatellite instability (MSI) data analysis

TMB is characterized as the cumulative count of

somatic gene coding inaccuracies, including base substitutions,

insertions, or deletions, identified per million bases. In the

present research, the determination of TMB for each tumor sample

involved calculating the mutation frequency and the number of

mutations relative to the exome length. Specifically, TMB was used

by dividing the number of non-synonymous mutation sites by the

total length of the protein-coding region (25).

Nomogram model construction

A nomogram was developed through regression

analysis, incorporating gene expression levels and clinical

symptoms. This nomogram visually represents the relationships

between variables within the prediction model by means of scaled

lines plotted on a single plane. A multivariate regression model

was constructed and the contribution of each influencing factor to

the outcome variable (regression coefficient) was used to assign

scores to each level of each influencing factor. The scores were

summed to obtain a total score, from which the predicted value was

calculated.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Using the largest pharmacogenomics database (GDSC;

https://www.cancerrxgene.org/), the R

package ‘pRRophetic’ (26) was

used to predict chemotherapy sensitivity for each tumor sample.

Regression methods were used to obtain IC50 estimates

for each specific chemotherapy drug treatment, and 10-fold

cross-validation was performed on the GDSC training set to verify

regression and prediction accuracy. All parameters were set to

default values, including the removal of batch effects with

‘combat’ and averaging of replicated gene expression values.

Single-cell analysis

First, the Seurat package (27) was employed to read the expression

profiles. Genes with low expression were filtered out based on the

criteria: nFeature_RNA >50 and percent.mt <15. Subsequently,

the data underwent normalization and scaling, followed by

processing using principal component analysis (PCA). The ElbowPlot

function was used to ascertain the optimal number of principal

components. To visualize the positions of each cluster,

t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (28) analysis was carried out. Annotation

of the clusters was performed using the celldex package (29), enabling the identification of cell

types that are significantly associated with the occurrence of the

disease. Each subunit of single cells was annotated using the R

package SingleR (30).

Disease gene co-expression

network

Disease-related genes were obtained from the

GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/). Genes with high relevance

scores were selected, and a correlation analysis was conducted to

explore the co-expression network between key genes and

disease-related genes. The Pearson correlation method was used for

the statistical analysis.

Cell culture

The immortalized cells of human ureteral epithelium

(SV-HUC-1), and human bladder cancer cell lines (T24, 5637, UMUC3,

J82) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection

(ATCC). SV-HUC-1 cells were cultured in F-12K medium (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). T24, 5637, UMUC3, and J82 cells were

cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; Corning, Inc.). The cells were incubated in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37˚C. Regular

observation of the structural state of the cells during cell

culture and regular checks for mycoplasma contamination were

performed.

Reverse transcription quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) was utilized to extract RNA from cells and

tissues. Subsequently, complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was

carried out with a reverse transcription system (FastKing One Step

RT-PCR kit; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.), following the

manufacturer's instructions precisely. RT-qPCR was performed in

triplicate using the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix

(TransStart® Top Green qPCR SuperMix; TransGen Biotech

Co., Ltd.) on 96-well optical plates according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: Pre-denaturation at 95˚C for 3 min, denaturation at 95˚C

for 30 sec, annealing extension at 60˚C for 30 sec, deformation and

annealing extension for 40 cycles. The dissolution curve was

increased by 0.5˚C every 2 cycles to 95˚C. The results were

normalized to the endogenous control, β-actin. The primers used are

listed in Table SI. The

2-ΔΔCq method was used for quantification (31).

Statistical analysis

Reliable MR analysis is based on three assumptions:

i) Relevance assumption (instrumental variables are closely related

to the exposure but not directly related to the outcome); ii)

independence assumption (instrumental variables are not related to

confounding factors); and iii) exclusion restriction assumption

(instrumental variables only affect the outcome through the

exposure; when IVs can affect the outcome through other pathways,

pleiotropy is present). All analyses were conducted using R

language (version 4.0). Continuous variables were compared using

paired and unpaired Student's t-test, or one-way ANOVA

(single-factor analysis) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test for

multiple-group comparisons. Data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation (SD) from three independent biological

replicates. All statistical tests were two-sided. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

pQTL MR analysis in the training

set

The outcome ID finngen_R10_C3_BLADDER_EXALLC,

related to bladder cancer, was obtained from summary statistics of

316,386 samples (2,193 cases and 314,193 controls). Using the

extract_instruments and extract_outcome_data functions, 342 pairs

of gene-outcome causal relationships were extracted (Table SII). Further MR analysis

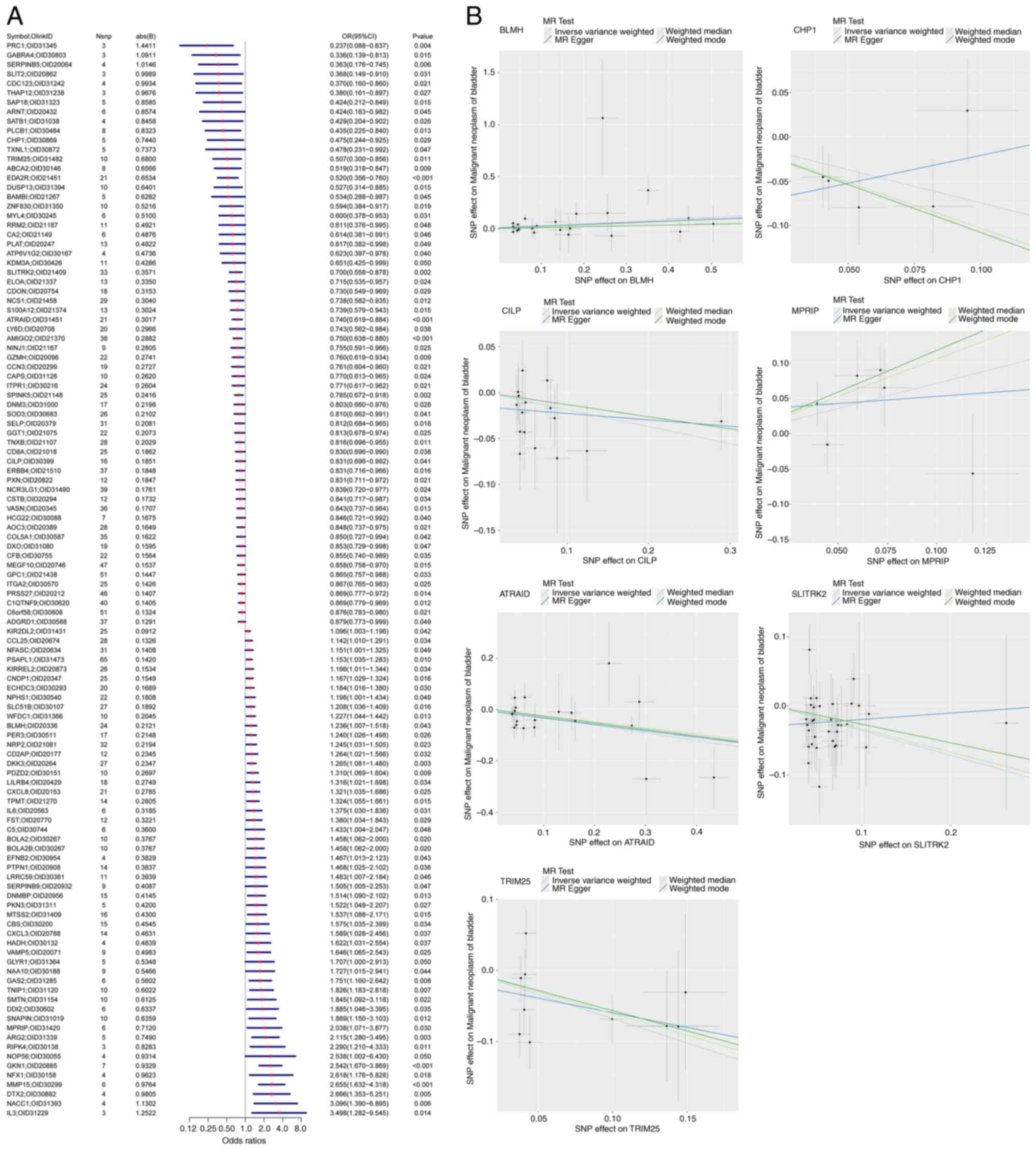

identified 114 gene-pQTL-positive causal relationships (Fig. 1A; IVW, P<0.05). Sensitivity

analysis was performed on the causal relationships of the 114 genes

to verify their reliability. The results indicated that the removal

of any SNP did not significantly affect the overall error lines,

suggesting that the 114 causal relationships were robust.

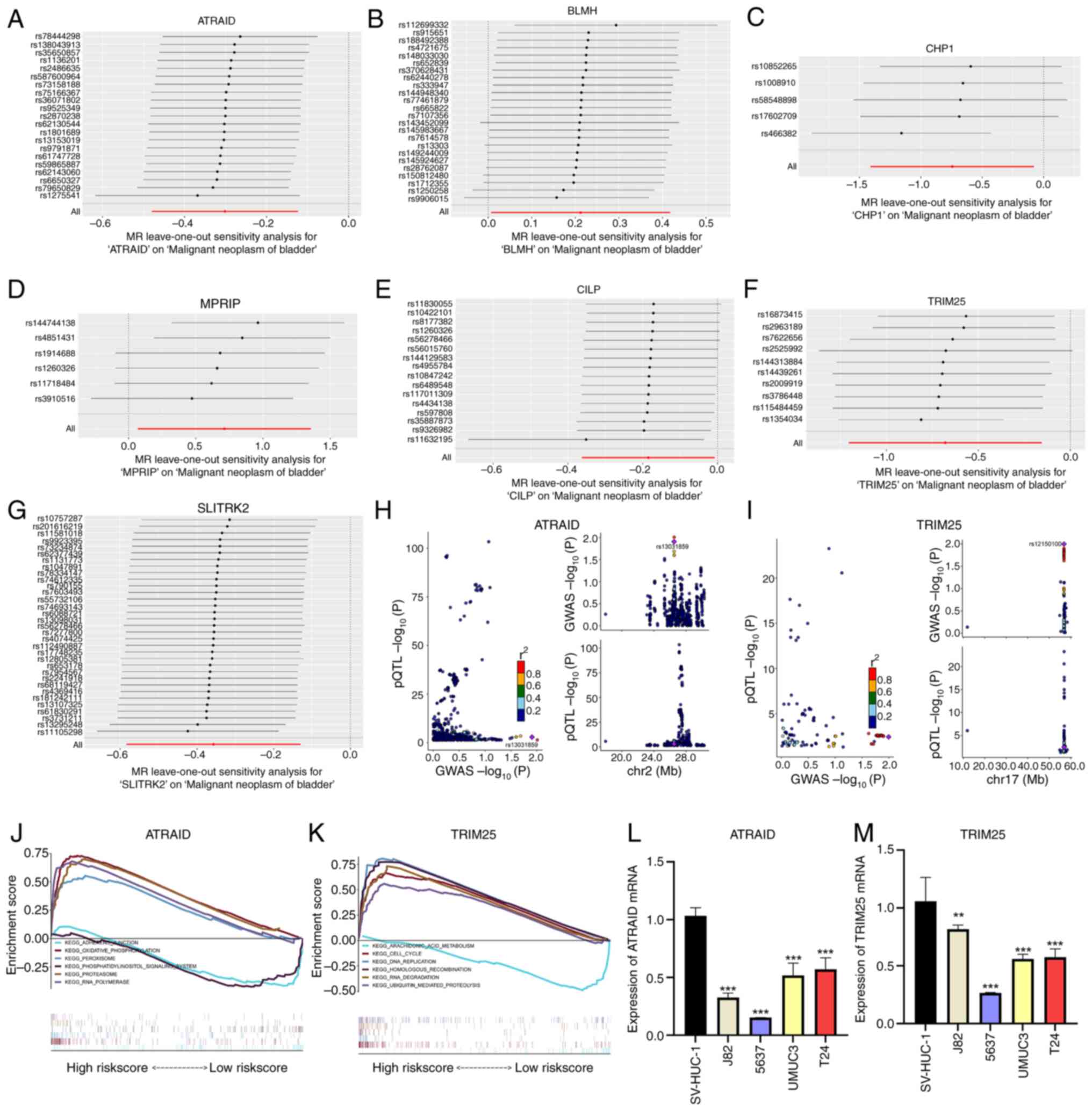

pQTL MR analysis

To further identify key genes among the 114 pQTL

genes associated with bladder cancer, the outcome ID GCST90041858

was obtained from the summary statistics of 456,348 samples related

to bladder cancer (762 cases and 455,586 controls). Using the

extract_instruments and extract_outcome_data functions, 22 pairs of

gene-outcome causal relationships were extracted (Table SIII). Further MR analysis

identified seven gene-pQTL-positive causal relationships (Fig. 1B; P<0.05), corresponding to the

genes all-trans retinoic acid-induced differentiation factor

(ATRAID), bleomycin hydrolase (BLMH), calcineurin B homologous

protein 1 (CHP1), cartilage intermediate layer protein (CILP),

myosin phosphatase Rho-interacting protein (MPRIP), SLIT and

NTRK-like family member 2 (SLITRK2), and tripartite motif

containing 25 (TRIM25). The genes ATRAID, BLMH, MPRIP, and TRIM25

were potentially associated with a low risk of bladder cancer. The

genes CHP1, CILP, and SLITRK2 were potentially associated with a

high risk of bladder cancer. Sensitivity analysis was performed on

the causal relationships of the seven genes to verify their

reliability. The results indicated that the removal of any SNP did

not significantly affect the overall error lines, suggesting that

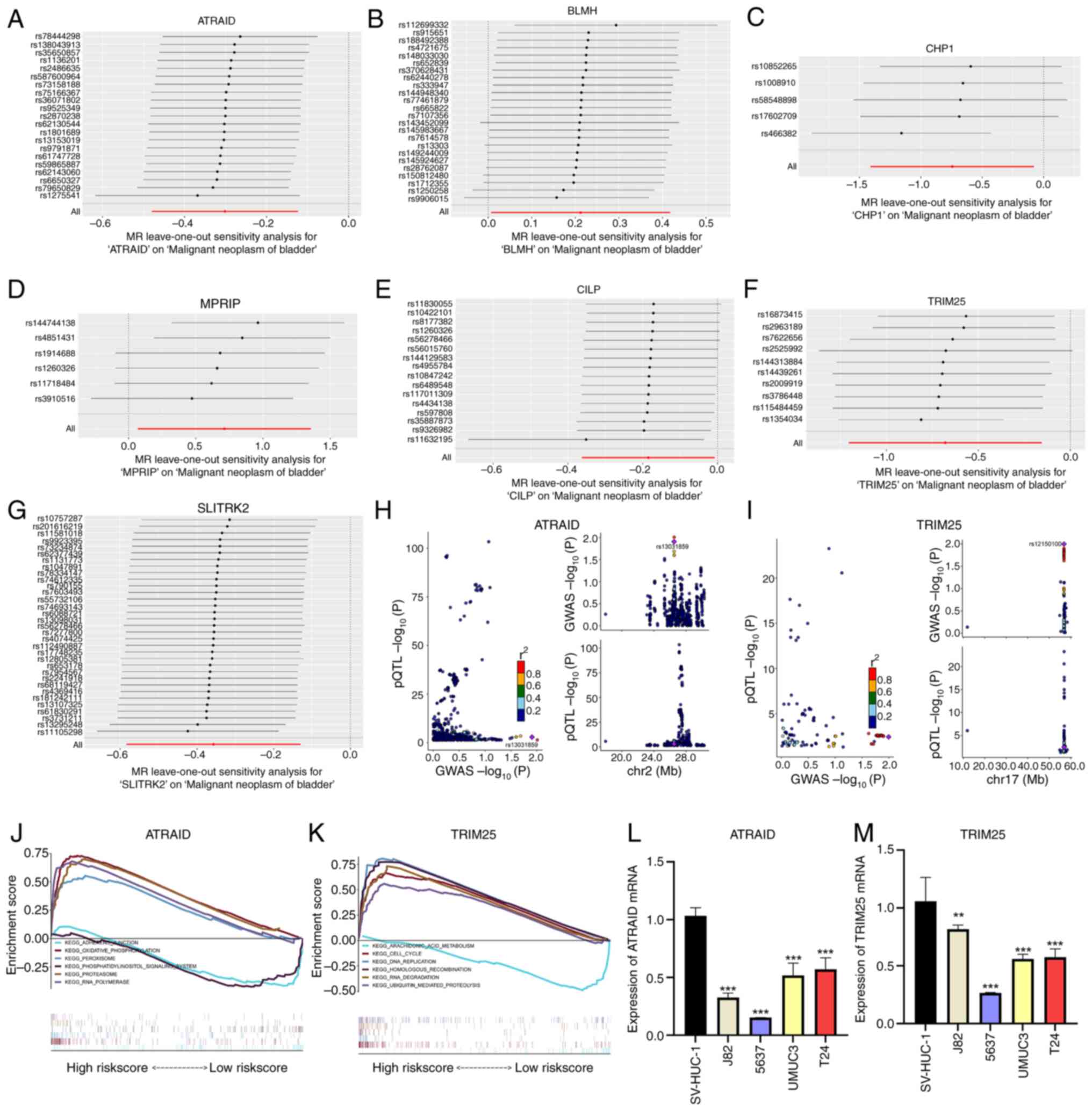

the seven causal relationships were robust (Fig. 2A-G). Additionally, colocalization

analysis at the pQTL-GWAS level identified two genes with

colocalization SNP.PP.H4 >0.95 (Fig. 2H and I), specifically ATRAID and TRIM25.

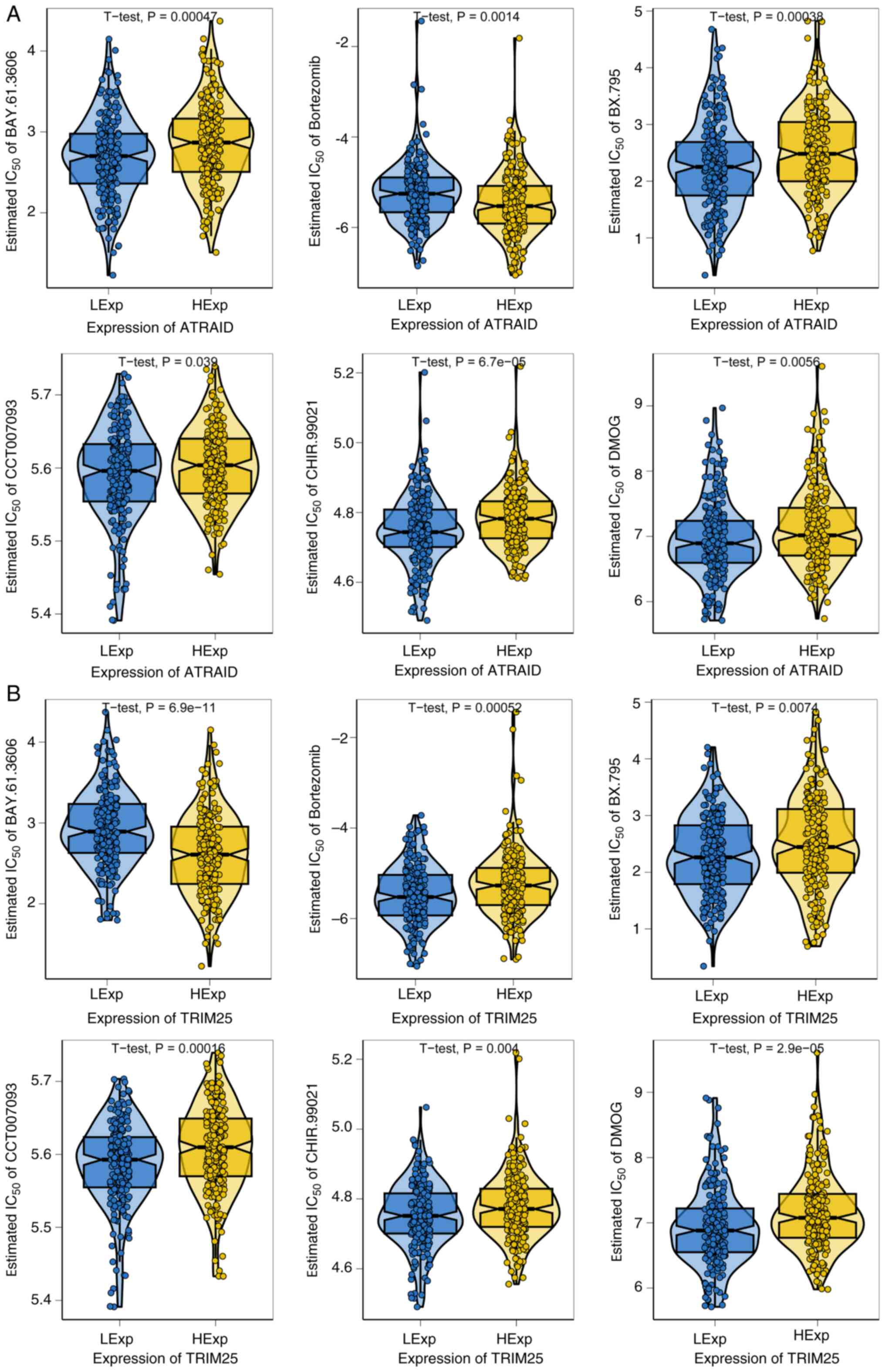

| Figure 2Key gene screening and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR validation. (A-G) Forest plots of

leave-one-out analysis for SNPs corresponding to the seven genes.

(H and I) Associations between SNPs of ATRAID and TRIM25 with the

disease, where each point indicates a statistically significant

SNP-disease association. The x-axis represents the P-value of GWAS,

and the y-axis represents the P-value of the pQTL analysis. (J and

K) KEGG signaling pathways involving ATRAID and TRIM25, including

genes involved in pathway regulation. (L and M) mRNA expression

levels of ATRAID and TRIM25 in bladder cancer cell lines.

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. SNP, single

nucleotide polymorphism; ATRAID, all-trans retinoic acid-induced

differentiation factor; TRIM25, tripartite motif containing 25;

GWAS, genome-wide association studies; pQTL, protein quantitative

trait loci; KEGG, Kyoto, Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. |

Exploration of specific signaling

mechanisms related to key genes

The specific signaling pathways involved with these

two key genes and their impact on disease progression-related

signaling pathways were explored. GSEA results indicated that

ATRAID was enriched in ‘ADHERENS_JUNCTION’,

‘OXIDATIVE_PHOSPHORYLATION’, and ‘PEROXISOME’ signaling pathways

(Fig. 2J). TRIM25 was enriched in

‘ARACHIDONIC_ACID_METABOLISM’, ‘CELL_CYCLE’, and ‘DNA_REPLICATION’

signaling pathways (Fig. 2K). GSEA

was further used to analyze the impact of these key genes on

signaling pathways. RT-qPCR was performed to investigate the mRNA

expression of ATRAID and TRIM25 in bladder cancer cell lines. The

results of RT-qPCR, based on bladder cancer cell lines,

demonstrated that the mRNA expression levels of ATRAID and TRIM25

were lower in tumor cell lines than in SV-HUC-1 cells (Fig. 2L and M).

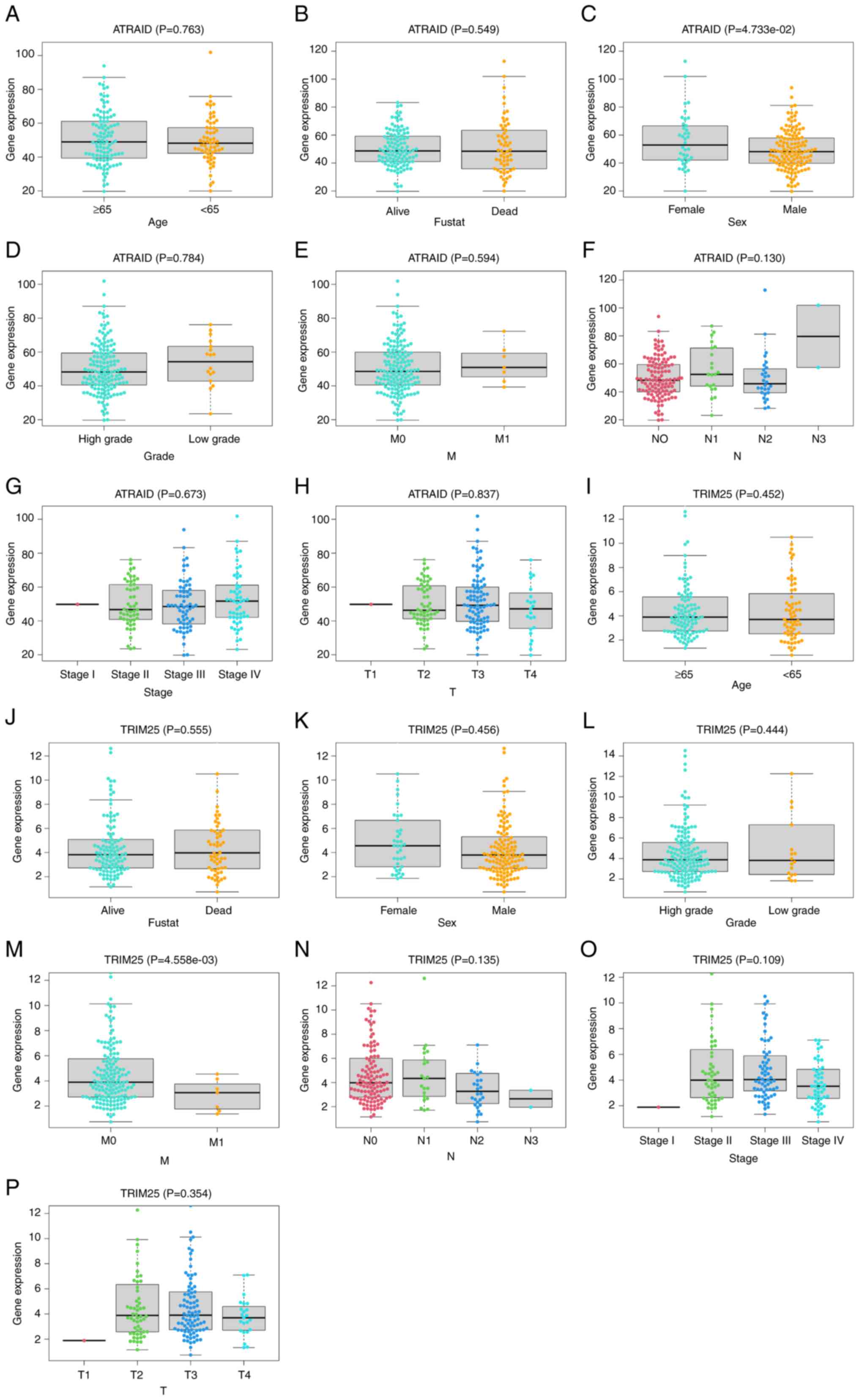

Clinical predictive value of key

genes

The relationship between key gene expression and

clinical symptoms was analyzed. The analysis revealed a significant

difference between ATRAID and the sex of patients (Fig. 3A-H), and a significant difference

between TRIM25 and the M stage of patients (Fig. 3I-P). These findings may provide

guidance and support for disease diagnosis and treatment, drug

development, and disease mechanism research.

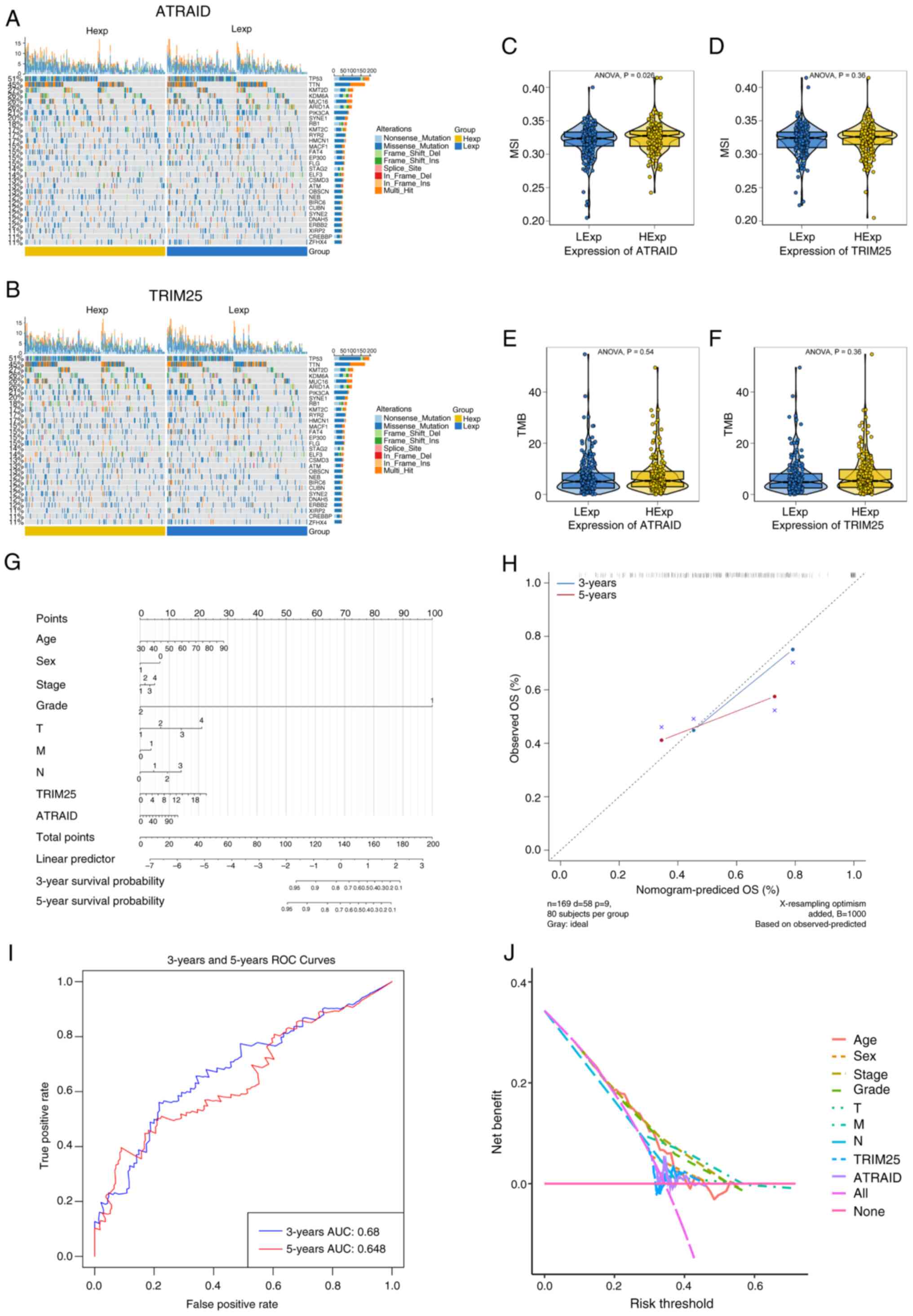

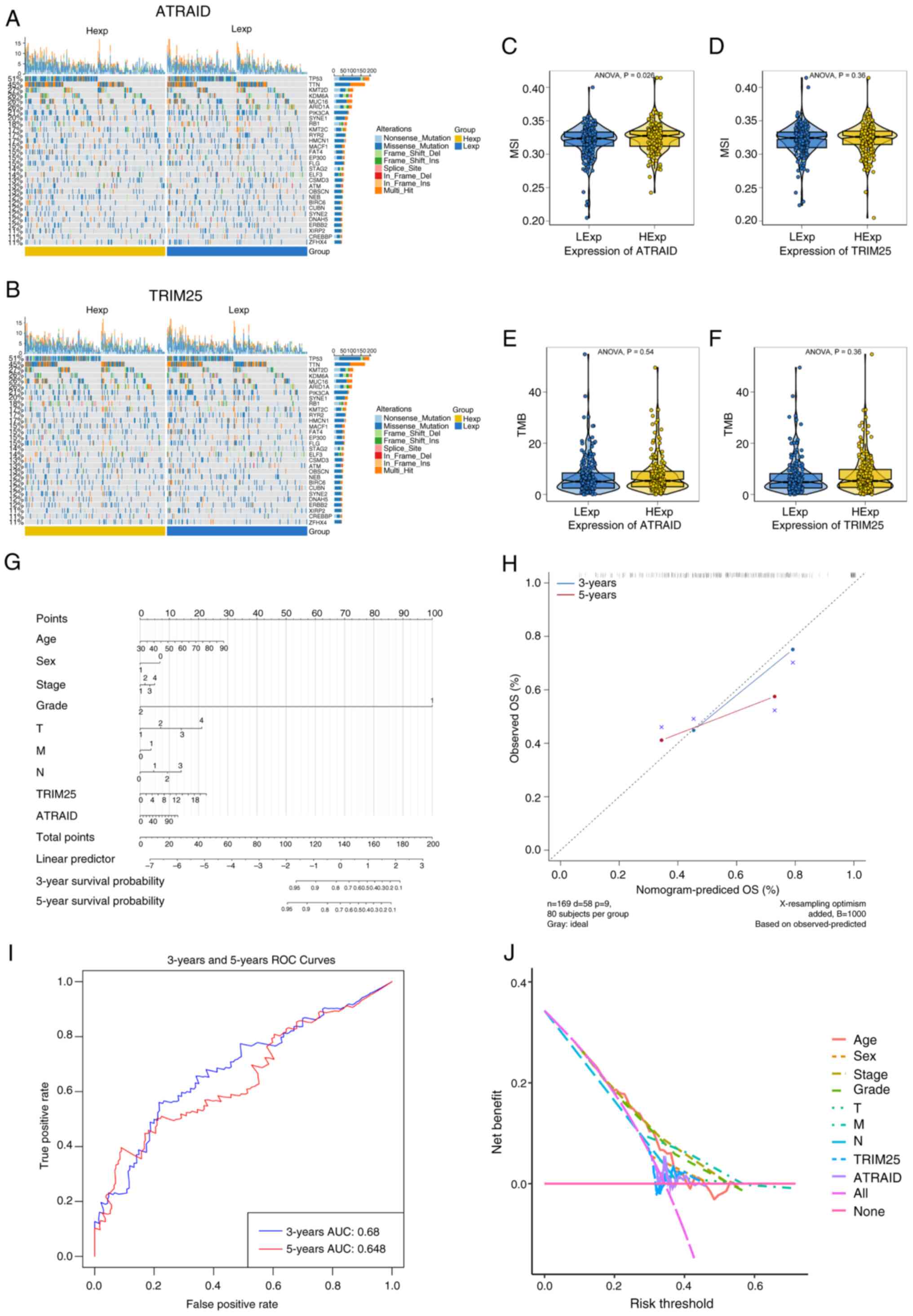

Mutation profile and differences in

TMB/MSI of key genes

Processed SNP-related data for bladder cancer were

downloaded and the top 30 genes were selected with high mutation

frequency for display, comparing the differences in mutated genes

between the two groups of patients. Using the R package

ComplexHeatmap, a mutation landscape map was plotted. The results

revealed that there was a significant difference in the mutation

frequency of AT-rich interaction domain 1 (ARID1A) between patients

with high and low ATRAID expression (P=0.005), with a higher

mutation proportion of ARID1A in the high-expression group

(Fig. 4A). Similarly, significant

differences in mutation frequencies of ARID1A (P=0.036),

microtubule-actin crosslinking factor 1 (MACF1; P=0.010), spectrin

repeat containing nuclear envelope protein 2 (SYNE2; P=0.026), and

CREB binding lysine acetyltransferase (CREBBP; P<0.001) were

also observed between subgroups based on TRIM25 expression. The

high TRIM25-expression group had a higher mutation proportion of

ARID1A, MACF1, SYNE2, and CREBBP compared with the low

TRIM25-expression group (Fig. 4B).

The relationship between the two key genes and common

immunotherapy-related tumor markers were further explored,

revealing the relationship between TMB and MSI in the high- and

low-expression groups of key genes (Fig. 4C-F). The results indicated a

statistically significant relationship between ATRAID and MSI

(Fig. 4C).

| Figure 4Mutational landscape of key genes,

differences in TMB/MSI, and construction of the Nomogram model. (A

and B) SNP-related data of bladder cancer, showing the top 30 genes

with high mutation frequencies in 2 patient groups. (C-F)

Differences in MSI and TMB between ATRAID and TRIM25. (G) Column

chart of the key gene model. (H) Prediction analysis of OS for 3

and 5 years. (I and J) ROC curve and decision curve analysis. TMB,

tumor mutation burden; MSI, microsatellite instability; SNP, single

nucleotide polymorphism; ATRAID, all-trans retinoic acid-induced

differentiation factor; TRIM25, tripartite motif containing 25; OS,

overall survival; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; LExp; low

expression; HExp, high expression; AUC, area under the curve. |

Nomogram model construction

The expression levels of key genes were used to

present the results of the regression analysis in the form of a

nomogram. The regression analysis results indicated that various

indicators of bladder cancer, along with the distribution of key

gene expression, contributed to different extents in the overall

scoring process (Fig. 4G). A

predictive analysis for the 3 and 5-year overall survival (OS)

periods was also conducted. The results indicated that the

predicted OS closely matched the observed OS, demonstrating the

good predictive performance of the nomogram model. In the

calibration curve, the data points in blue (3-year) and red

(5-year) are both closely distributed along the diagonal line,

indicating that the predicted OS aligns well with the observed OS

(Fig. 4H). In the receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the area under the curve

(AUC) for the 3-year OS prediction was 0.68, and the AUC for the

5-year OS prediction was 0.648. Although these AUC values were not

particularly high, they indicate that the model has a certain

ability to distinguish between the 3 and 5-year survival outcomes

of patients (Fig. 4I). In the

decision curve, the purple line representing the integration of key

genes and clinical indicators (‘All’) exhibited a higher net

benefit than lines incorporating only partial factors or no factors

(Fig. 4J). These findings suggest

that the nomogram model constructed by combining the clinical

indicators and key gene expression levels (corresponding to the

‘All’ curve) can provide greater net benefits to patients accross

appropriate risk thresholds in real-world clinical

decision-making.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Early-stage bladder cancer is effectively treated

with surgery combined with chemotherapy (32). The present study used drug

sensitivity data from the GDSC database and the R package

‘pRRophetic’ to predict the chemotherapy sensitivity of each tumor

sample, and further explored the sensitivity to common chemotherapy

drugs. The results indicated that the two key genes, ATRAID and

TRIM25, were significantly associated with sensitivity to

BAY.61.3606, bortezomib, BX.795, CCT007093, CHIR.99021, and DMOG.

High ATRAID expression was associated with increased resistance of

bladder cancer cells to BAY.61.3606, BX.795, CCT007093, CHIR.99021,

and DMOG (higher IC50 values indicate a need for higher

drug concentrations to inhibit 50% of cells), while enhancing

sensitivity to bortezomib (Fig.

5A). Conversely, high TRIM25 expression led to increased

resistance to bortezomib, BX.795, CCT007093, CHIR.99021, and DMOG,

but enhanced sensitivity to BAY.61.3606 (Fig. 5B).

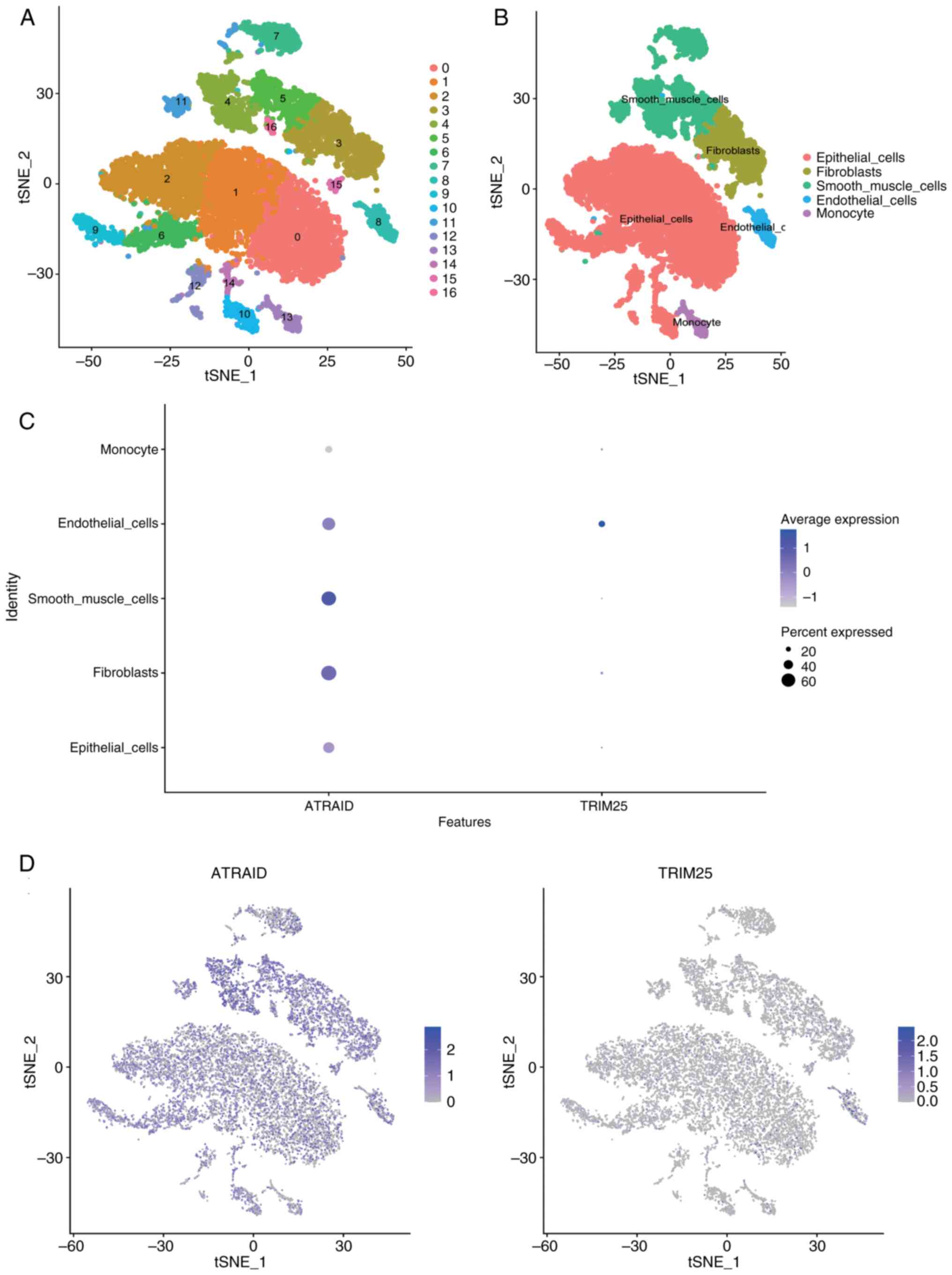

Expression of key genes at the

single-cell level

The analysis of the present study included

expression profiles from three bladder cancer-related tissue

samples. Using the FindClusters function from the Seurat package,

17 subtypes were identified (Fig.

6A). The R package SingleR was used to annotate each subtype,

identifying 17 clusters into five cell types: Epithelial_cells,

Fibroblasts, Smooth_muscle_cells, Endothelial_cells, and Monocytes

(Fig. 6B). The expression of the

two key genes in cell subtypes was analyzed and the results using

bubble plots and scatter plots are displayed (Fig. 6C and D). The findings revealed that ATRAID and

TRIM25 were expressed in multiple cell types, but their expression

was more widespread or higher in certain cells (such as epithelial

cells and fibroblasts). Multiple key genes were found to be

co-expressed with tumor genes. Co-expression relationships

(including both positive and negative co-expression) reflect the

correlation trends in expression levels between genes. When two

genes exhibit positive co-expression, their expression levels tend

to change in the same direction across samples.

Apoptosis-associated transcript in bladder cancer (AATBC) exhibited

a negative co-expression association with both the ATRAID and

TRIM25 genes (Fig. S1A and

B). Fibroblast growth factor

receptor 3 (FGFR3) was positively co-expressed with ATRAID and

negatively co-expressed with TRIM25 (Fig. S1C and D). Hras proto-oncogene, GTPase (HRAS)

was positively co-expressed with both ATRAID and TRIM25 (Figs. S1E and S2A). RB transcriptional corepressor 1

(RB1) was positively co-expressed with ATRAID and negatively

expressed with TRIM25 (Fig. S2B

and C). Tumor ptotein 53 (TP53)

was positively co-expressed with ATRAID and negatively expressed

with TRIM25 (Fig. S2D and

E). Positive co-expression

between two genes may indicate their involvement in the same

biological process or signaling pathway, achieving functional

coordination through synergistic expression. Alternatively, one

gene may act as an upstream regulatory factor for the other. By

contrast, negative co-expression of two genes, may reflect opposing

roles in biological processes, an antagonistic relationship within

a shared pathway, or mutual inhibitory regulation.

Discussion

In the present study, seven plasma proteins were

detected and the gene expression levels of these proteins were

found to be significantly associated with the risk of bladder

cancer. Among them, the genes ATRAID and TRIM25 had a probability

>0.95 of affecting the same phenotype in both pQTL and GWAS

data, suggesting a high likelihood that these two genes are

involved in the same biological pathway. The present study

identified novel biomarkers for bladder cancer, which may provide

new insights into the genetics and pathogenesis of bladder

cancer.

ATRAID, also known as APR3, is a gene associated

with apoptosis (33,34). Located on human chromosome 2p22.3,

it can affect the cell cycle by altering cyclin D1 expression,

thereby influencing malignant tumor occurrence and growth, and

promoting cell differentiation (35). In the present study, its potential

as a diagnostic marker for bladder cancer was identified,

suggesting a suppressive role in the development of bladder cancer.

However, previous studies have found increased expression of ATRAID

in ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, and lung adenocarcinoma,

suggesting an oncogenic role (35-37),

although no studies, to the best of the authors' knowledge, have

yet been conducted on ATRAID in bladder cancer. Pathway enrichment

analysis of ATRAID in the present study revealed significant

enrichment in adhesion function and oxidative stress. Li et

al (33) similarly found that

upregulation of APR3 expression in ARPE-19 cells significantly

increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and

altered mitochondrial morphology, promoting cell oxidative stress

by affecting mitochondrial function. ATRAID may also exert its

effects in bladder cancer through similar oxidative stress

pathways.

In the analysis of the relationship between ATRAID

and clinical characteristics, it was determined that the expression

of ATRAID was lower in male patients than in female patients. It

was speculated that this difference may be related to sex

chromosome-associated genes regulating ATRAID, and it is also

possible that sex hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and

testosterone may affect the expression of ATRAID. These findings

suggest a potential direction for future research. In immune

infiltration analysis, high expression of ATRAID was significantly

positively associated with MSI status, indicating its important

role in MSI tumors and possibly serving as a novel therapeutic

target.

TRIM25 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase confirmed to be an

RNA-binding protein (RBP) through its spry domain, and it plays a

crucial role in gene regulation, controlling cell proliferation,

and cancer cell migration (38-40).

The regulation of TRIM25 in tumors is largely through regulation of

the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which can regulate apoptosis of

tumors through the IRE1-JNK signal, upregulating the unfolded

protein response and ER-associated degradation pathways (41,42).

TRIM25 has been shown to play a role in the development of colon

cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, endometrial cancer, gastric

cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, ovarian

cancer, and renal cancer (43-53).

Although several studies have explored the role of TRIM25 in

bladder cancer, research on its role in this cancer type remains

limited and requires further investigation (54-56).

Pathway enrichment analysis of TRIM25 in the present study showed

significant enrichment in ‘ARACHIDONIC_ACID_METABOLISM’,

‘CELL_CYCLE’, and ‘DNA_REPLICATION’ pathways. The enrichment of

TRIM25 in the cell cycle pathway indicated its potential role in

regulating cell cycle progression.

In the analysis of the relationship between TRIM25

and clinical characteristics, it was found that the expression of

TRIM25 was lower in patients with distant metastases than in those

without, which may indicate that the expression of TRIM25 is

related to the occurrence of tumor metastasis, possibly exerting an

inhibitory effect in the invasion and metastasis process of bladder

cancer cells.

By combining ATRAID and TRIM25 with patient clinical

data, bladder cancer 3 and 5-year survival prediction models were

constructed, with model AUCs of 0.68 and 0.648, respectively. The 3

and 5-year prognostic models constructed in the present study

demonstrated relatively high predictive accuracy, which can assist

clinicians in predicting the prognosis of individual patients. For

patients predicted to have a shorter survival time, more aggressive

treatment options can be considered, while for those predicted with

a longer predicted survival, more conservative treatment strategies

can be selected.

Drug sensitivity analysis of ATRAID and TRIM25

revealed that high expression of ATRAID was associated with

increased resistance of bladder cancer cells to BAY.61.3606,

BX.795, CCT007093, CHIR.99021, and DMOG (higher IC50

values indicate higher drug concentrations required to inhibit 50%

of cells), while enhancing sensitivity to bortezomib. Conversely,

high expression of TRIM25 led to increased resistance to

bortezomib, BX.795, CCT007093, CHIR.99021, and DMOG, but enhanced

sensitivity to BAY.61.3606. From the perspective of drug

sensitivity, these findings suggest that the expression levels of

ATRAID and TRIM25 may serve as drug response prediction indicators

(patients with high expression may exhibit poorer efficacy to these

drugs). This implies that the expression levels of these two genes

may influence the response of tumor cells to these drugs, and the

drugs may regulate bladder cancer by affecting signaling pathways

associated with ATRAID and TRIM25. Further investigation of these

associations could improve our understanding of tumor drug response

mechanisms and provide novel insights and strategies for

personalized therapy.

ATRAID was mainly expressed in ‘Fibroblasts’ and

‘Smooth_muscle_cells’, indicating that ATRAID may play an important

role in tumor stromal remodeling or microenvironment regulation.

TRIM25 was mainly expressed in ‘Endothelial_cells’, indicating that

TRIM25 may play an important role in encoding vascular growth

factors and regulating vascular maturation and stability.

In the present study, the association between plasma

protein biomarkers and bladder cancer risk was comprehensively

explored. A two-stage screening MR design was employed, which is

characterized by a large sample size and a minimal likelihood of

reverse causation and confounding bias. The consistency of multiple

rigorous analysis results confirms the robustness of the findings

of the present study. By screening ATRAID and TRIM25, a predictive

model was constructed to effectively predict the 3 and 5-year

survival rates. The small sample size in the single-cell analysis

of bladder cancer may fail to accurately reflect cellular

heterogeneity, which is also one of the limitations of the present

study. In addition, only qPCR was used to verify the RNA expression

levels of the two genes, ATRAID and TRIM25. Verification at the

protein level using western blotting and immunohistochemistry has

yet to be carried out. Similarly, the functional verification of

the ATRAID and TRIM25 genes in bladder cancer and the exploration

of the mechanisms by which these two genes participate in the

occurrence and development of bladder cancer have not been

performed. Subsequently, bladder cancer cell lines with knockdown

and overexpression of the ATRAID and TRIM25 genes will be

constructed for functional exploration. Furthermore, the specific

mechanisms affected by these two genes will be investigated,

particularly in the direction of bladder cancer drug resistance. In

addition, an in-depth research on their mechanisms will be

conducted, so as to provide valuable insights for future studies on

drug resistance in bladder cancer. In the present study, ATRAID and

TRIM25 were identified as biomarkers associated with bladder cancer

risk. These findings not only provide novel perspectives on the

causes of bladder cancer, but also offer potential targets for the

development of innovative biomarkers and therapeutic drugs against

bladder cancer.

Supplementary Material

Co-expression with disease genes.

(A-E) Co-expression analysis of disease-related genes with ATRAID

and TRIM25 in single-cell data, including the correlation of

co-expressed genes. ATRAID, all-trans retinoic acid-induced

differentiation factor; TRIM25, tripartite motif containing 25;

AATBC, apoptosis-associated transcript in bladder cancer; FGFR3,

fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; HRAS, Hras proto-oncogene,

GTPase; t-SNE, t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding.

Co-expression with disease genes.

(A-E) Co-expression analysis of disease-related genes with ATRAID

and TRIM25 in single-cell data, including the correlation of

co-expressed genes. ATRAID, all-trans retinoic acid-induced

differentiation factor; TRIM25, tripartite motif containing 25;

HRAS, Hras proto-oncogene, GTPase; RB1, RB transcriptional

corepressor 1; TP53, tumor protein 53; t-SNE, t-distributed

Stochastic Neighbor Embedding.

Primer sequences.

Mendelian randomization analysis of

342 gene-outcome causal relationships in the training set of

pQTL.

Mendelian randomization analysis of 22

gene-outcome causal relationships in the validation set of

pQTL.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Central

Government Guiding Local Funds for Science and Technology

Development (grant no. 236Z7710G), and the Peking University First

Hospital-Miyun Hospital Joint Program (grant no.

2023-study029-001).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WG, YL, ZF, ZG, YaG, XJ, YJ and YuG conceptualized

and designed the present study. WG, YL, ZF, ZG, YaG, XJ, YJ and YuG

provided administrative support. WG, YL and ZF conducted the

collation of public data. WG, YL and ZF collected and assembled the

data of the present study. WG, YL and ZF analyzed and interpretated

the data. WG and YuG confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors assisted with the writing of the present study, and

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was carried out in compliance with

the Declaration of Helsinki (revised in 2013). Additionally, the

present study was approved (approval no. 2023-029-001) by the

Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital-Miyun Hospital

(Beijing, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang Y, Rumgay H, Li M, Yu H, Pan H and

Ni J: The global landscape of bladder cancer incidence and

mortality in 2020 and projections to 2040. J Glob Health.

13(04109)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Peng M, Chu X, Peng Y, Li D, Zhang Z, Wang

W, Zhou X, Xiao D and Yang X: Targeted therapies in bladder cancer:

Signaling pathways, applications, and challenges. MedComm (2020).

4(e455)2023.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Thomas J and Sonpavde G: Molecularly

targeted therapy towards genetic alterations in advanced bladder

cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14(1795)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Anderson NL and Anderson NG: The human

plasma proteome: History, character, and diagnostic prospects. Mol

Cell Proteomics. 1:845–867. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Suhre K, McCarthy MI and Schwenk JM:

Genetics meets proteomics: Perspectives for large population-based

studies. Nat Rev Genet. 22:19–37. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Roslan A, Sulaiman N, Mohd Ghani KA and

Nurdin A: Cancer-associated membrane protein as targeted therapy

for bladder cancer. Pharmaceutics. 14(2218)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sarafidis M, Lambrou GI, Zoumpourlis V and

Koutsouris D: An integrated bioinformatics analysis towards the

identification of diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive key

biomarkers for urinary bladder cancer. Cancers (Basel).

14(3358)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kojima T, Kawai K, Miyazaki J and

Nishiyama H: Biomarkers for precision medicine in bladder cancer.

Int J Clin Oncol. 22:207–213. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Pietzner M, Wheeler E, Carrasco-Zanini J,

Cortes A, Koprulu M, Wörheide MA, Oerton E, Cook J, Stewart ID,

Kerrison ND, et al: Mapping the proteo-genomic convergence of human

diseases. Science. 374(eabj1541)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ferkingstad E, Sulem P, Atlason BA,

Sveinbjornsson G, Magnusson MI, Styrmisdottir EL, Gunnarsdottir K,

Helgason A, Oddsson A, Halldorsson BV, et al: Large-scale

integration of the plasma proteome with genetics and disease. Nat

Genet. 53:1712–1721. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhang J, Dutta D, Köttgen A, Tin A,

Schlosser P, Grams ME and Harvey B: CKDGen Consortium. Yu B,

Boerwinkle E, et al: Plasma proteome analyses in individuals of

European and African ancestry identify cis-pQTLs and models for

proteome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 54:593–602.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey

D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Burgess S, Jiang T, Paige E, Surendran

P, et al: Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature.

558:73–79. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Suhre K, Arnold M, Bhagwat AM, Cotton RJ,

Engelke R, Raffler J, Sarwath H, Thareja G, Wahl A, DeLisle RK, et

al: Connecting genetic risk to disease end points through the human

blood plasma proteome. Nat Commun. 8(14357)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Davies NM, Holmes MV and Davey Smith G:

Reading mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and

checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 362(k601)2018.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Xin J, Gu D, Chen S, Ben S, Li H, Zhang Z,

Du M and Wang M: SUMMER: A Mendelian randomization interactive

server to systematically evaluate the causal effects of risk

factors and circulating biomarkers on pan-cancer survival. Nucleic

Acids Res. 51 (D1):D1160–D1167. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sun BB, Chiou J, Traylor M, Benner C, Hsu

YH, Richardson TG, Surendran P, Mahajan A, Robins C,

Vasquez-Grinnell SG, et al: Plasma proteomic associations with

genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature. 622:329–338.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Yu Z, Liao J, Chen Y, Zou C, Zhang H,

Cheng J, Liu D, Li T, Zhang Q, Li J, et al: Single-cell

transcriptomic map of the human and mouse bladders. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 30:2159–2176. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Burgess S, Butterworth A and Thompson SG:

Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants

using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 37:658–665. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bowden J, Davey Smith G and Burgess S:

Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: Effect estimation

and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol.

44:512–525. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC and

Burgess S: Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with

some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet

Epidemiol. 40:304–314. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G and Bowden J:

Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the

zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol. 46:1985–1998.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE,

Franke L, Hingorani AD, Wallace C and Plagnol V: Bayesian test for

colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using

summary statistics. PLoS Genet. 10(e1004383)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK,

Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub

TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP: Gene set enrichment analysis: A

knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression

profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:15545–15550. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bonneville R, Krook MA, Kautto EA, Miya J,

Wing MR, Chen HZ, Reeser JW, Yu L and Roychowdhury S: Landscape of

microsatellite instability across 39 cancer types. JCO Precis

Oncol. 2017(PO.17.00073)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Geeleher P, Cox N and Huang RS:

pRRophetic: An R package for prediction of clinical

chemotherapeutic response from tumor gene expression levels. PLoS

One. 9(e107468)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM

III, Zheng S, Butler A, Lee MJ, Wilk AJ, Darby C, Zager M, et al:

Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell.

184:3573–3587.e29. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Cieslak MC, Castelfranco AM, Roncalli V,

Lenz PH and Hartline DK: t-Distributed stochastic neighbor

embedding (t-SNE): A tool for eco-physiological transcriptomic

analysis. Mar Genomics. 51(100723)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhang Q, Yu B, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Yang S,

Chen Y and Wu H: Combination of single-cell and bulk RNA seq

reveals the immune infiltration landscape and targeted therapeutic

drugs in spinal cord injury. Front Immunol.

14(1068359)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V,

Hsu A, Chak S, Naikawadi RP, Wolters PJ, Abate AR, et al:

Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a

transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat. Immunol. 20:163–172.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wang W, Lu Z, Wang M, Liu Z, Wu B, Yang C,

Huan H and Gong P: The cuproptosis-related signature associated

with the tumor environment and prognosis of patients with glioma.

Front Immunol. 13(998236)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Li Y, Zou X, Gao J, Cao K, Feng Z and Liu

J: APR3 modulates oxidative stress and mitochondrial function in

ARPE-19 cells. FASEB J: fj201800001RR, 2018 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

34

|

Zhu F, Yan W, Zhao ZL, Chai YB, Lu F, Wang

Q, Peng WD, Yang AG and Wang CJ: Improved PCR-based subtractive

hybridization strategy for cloning differentially expressed genes.

Biotechniques. 29:310–313. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang Y, Li Q, Huang W, Zhang J, Han Z,

Wei H, Cui J, Wang Y and Yan W: Increased expression of

apoptosis-related protein 3 is highly associated with tumorigenesis

and progression of cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol.

44:388–393. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zhang P, Zhou C, Jing Q, Gao Y, Yang L, Li

Y, Du J, Tong X and Wang Y: Role of APR3 in cancer: Apoptosis,

autophagy, oxidative stress, and cancer therapy. Apoptosis.

28:1520–1533. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Cao HL, Gu MQ, Sun Z and Chen ZJ:

miR-144-3p contributes to the development of thyroid tumors through

the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 12:9845–9855.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kwon SC, Yi H, Eichelbaum K, Föhr S,

Fischer B, You KT, Castello A, Krijgsveld J, Hentze MW and Kim VN:

The RNA-binding protein repertoire of embryonic stem cells. Nat

Struct Mol Biol. 20:1122–1130. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Choudhury NR, Heikel G, Trubitsyna M,

Kubik P, Nowak JS, Webb S, Granneman S, Spanos C, Rappsilber J,

Castello A and Michlewski G: RNA-binding activity of TRIM25 is

mediated by its PRY/SPRY domain and is required for ubiquitination.

BMC Biol. 15(105)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Heikel G, Choudhury NR and Michlewski G:

The role of Trim25 in development, disease and RNA metabolism.

Biochem Soc Trans. 44:1045–1050. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Liu Y, Tao S, Liao L, Li Y, Li H, Li Z,

Lin L, Wan X, Yang X and Chen L: TRIM25 promotes the cell survival

and growth of hepatocellular carcinoma through targeting Keap1-Nrf2

pathway. Nat Commun. 11(348)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Rahimi-Tesiye M, Zaersabet M, Salehiyeh S

and Jafari SZ: The role of TRIM25 in the occurrence and development

of cancers and inflammatory diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev

Cancer. 1878(188954)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Shu XS, Zhao Y, Sun Y, Zhong L, Cheng Y,

Zhang Y, Ning K, Tao Q, Wang Y and Ying Y: The epigenetic modifier

PBRM1 restricts the basal activity of the innate immune system by

repressing retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like receptor signalling

and is a potential prognostic biomarker for colon cancer. J Pathol.

244:36–48. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Li YH, Zhong M, Zang HL and Tian XF: The

E3 ligase for metastasis associated 1 protein, TRIM25, is targeted

by microRNA-873 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Cell Res.

368:37–41. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wang J, Yin G, Bian H, Yang J, Zhou P, Yan

K, Liu C, Chen P, Zhu J, Li Z and Xue T: LncRNA XIST upregulates

TRIM25 via negatively regulating miR-192 in hepatitis B

virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med.

27(41)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Dai H, Zhao S, Xu L, Chen A and Dai S:

Expression of Efp, VEGF and bFGF in normal, hyperplastic and

malignant endometrial tissue. Oncol Rep. 23:795–799.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Dai H, Zhang P, Zhao S, Zhang J and Wang

B: Regulation of the vascular endothelial growth factor and growth

by estrogen and antiestrogens through Efp in Ishikawa endometrial

carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 21:395–401. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yang KS, Xu CQ and Lv J: Identification

and validation of the prognostic value of cyclic GMP-AMP

synthase-stimulator of interferon (cGAS-STING) related genes in

gastric cancer. Bioengineered. 12:1238–1250. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wang S, Kollipara RK, Humphries CG, Ma SH,

Hutchinson R, Li R, Siddiqui J, Tomlins SA, Raj GV and Kittler R:

The ubiquitin ligase TRIM25 targets ERG for degradation in prostate

cancer. Oncotarget. 7:64921–64931. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Qin X, Chen S, Qiu Z, Zhang Y and Qiu F:

Proteomic analysis of ubiquitination-associated proteins in a

cisplatin-resistant human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Int J Mol

Med. 29:791–800. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Walsh LA, Alvarez MJ, Sabio EY, Reyngold

M, Makarov V, Mukherjee S, Lee KW, Desrichard A, Turcan Ş, Dalin

MG, et al: An integrated systems biology approach identifies TRIM25

as a key determinant of breast cancer metastasis. Cell Rep.

20:1623–1640. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Li F, Sun Q, Liu K, Zhang L, Lin N, You K,

Liu M, Kon N, Tian F, Mao Z, et al: OTUD5 cooperates with TRIM25 in

transcriptional regulation and tumor progression via

deubiquitination activity. Nat Commun. 11(4184)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhenilo S, Deyev I, Litvinova E, Zhigalova

N, Kaplun D, Sokolov A, Mazur A and Prokhortchouk E: DeSUMOylation

switches Kaiso from activator to repressor upon hyperosmotic

stress. Cell Death Differ. 25:1938–1951. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Tang H, Li X, Jiang L and Liu Z, Chen L,

Chen J, Deng M, Zhou F, Zheng X and Liu Z: RITA1 drives the growth

of bladder cancer cells by recruiting TRIM25 to facilitate the

proteasomal degradation of RBPJ. Cancer Sci. 113:3071–3084.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Li W, Shen Y, Yang C, Ye F, Liang Y, Cheng

Z, Ou Y, Chen W, Chen Z, Zou L, et al: Identification of a novel

ferroptosis-inducing micropeptide in bladder cancer. Cancer Lett.

582(216515)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Eberhardt W, Nasrullah U and Pfeilschifter

J: TRIM25: A global player of cell death pathways and promising

target of tumor-sensitizing therapies. Cells. 14(65)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|