1. Introduction

Cancer remains one of the leading causes of

morbidity and mortality worldwide, despite notable advances in

diagnostic technologies and therapeutic interventions. Traditional

treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy often cause

damaging side effects, exhibit limited specificity and frequently

lead to therapeutic resistance, thus collectively undermining the

quality of life of patients. For instance, ~40% of patients

undergoing chemotherapy experience severe adverse effects,

including gastrointestinal toxicity and myelosuppression (1,2),

while ~50% of those with advanced solid tumors develop drug

resistance (3,4). These limitations underscore an urgent

need for more precise and effective therapeutic strategies.

Recent advances in molecular biology and

computational analysis have revealed that RNA regulatory networks

play pivotal roles in cancer progression by orchestrating key

biological processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis

and drug resistance (5,6). Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including

microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and

their variants, have emerged as central players in these networks

(7,8). Notably, novel isoforms such as

isomiRs and mechanisms such as the competitive endogenous RNA

(ceRNA) network have introduced new layers of regulatory

complexity, with notable implications for cancer diagnostics and

treatment.

The present review provides a comprehensive and

integrative perspective on RNA regulatory networks in oncology,

with a particular focus on isomiRs and ceRNA interactions. Unlike

previous reviews, this article highlights how multi-omics

profiling, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), and CRISPR-based

functional screening enable high-resolution mapping of RNA

interactions and support their translation into clinical

applications. These tools offer the potential to address persistent

challenges in the field, such as dynamic heterogeneity,

spatiotemporal regulation and the inference of causality within

complex networks (9-11).

By synthesizing recent findings, the present article

highlights emerging molecular mechanisms, clinical relevance and

the translational potential of RNA networks in cancer. In addition,

barriers to their application were also discussed, particularly in

multi-omics integration, and promising technological directions

that may redefine precision oncology in the future were

described.

Recent clinical experiences have underscored the

need to align early clinical signals with mechanistic annotation in

RNA oncology. Durable benefit appears to depend as much on delivery

engineering and proactive mitigation of innate-immune sensing as on

the RNA payload itself. Representative programs using optimized

carriers and tissue-directed delivery (for example, lipid

nanoparticles and ligand conjugates) illustrate how organ/lesion

exposure, endosomal escape, and immune quieting can determine

translational success (12,13).

Specific trial details are summarized in ‘Strategies and

prospects’, and failure modes with practical lessons are discussed

in ‘Existing problems’.

2. Basic composition and mechanism of action

of RNA regulatory networks

Understanding the regulatory interplay among

different RNA species is fundamental to deciphering cellular

homeostasis and disease pathogenesis. In the following section, the

basic functions of mRNA, miRNA and lncRNA were reviewed, the

theoretical basis of the competitive ceRNA network was discussed

and the generation of isomiRs and their unique regulatory roles

were described.

Introduction to the basic functions of

mRNA, miRNA and lncRNA

mRNAs are the key intermediates between DNA and

proteins. They carry genetic information from the nucleus to the

cytoplasm, where they serve as templates for protein synthesis. The

translation of mRNAs into proteins is tightly regulated at multiple

levels, ensuring that proteins are produced in response to the

developmental stage of the cell and environmental cues. Previous

studies have shown that alterations in mRNA expression patterns are

not only reflective of cellular states, but also actively

contribute to the progression of diseases, including cancer

(5,7,11).

In contrast to mRNAs, miRNAs are short,

~22-nucleotide ncRNAs that function predominantly in

post-transcriptional gene regulation. By binding to complementary

sequences in the 3' untranslated regions (3' UTRs) of target mRNAs,

miRNAs mediate mRNA degradation or inhibit translation. This mode

of regulation is highly conserved and enables a single miRNA to

target multiple mRNAs simultaneously, thus orchestrating complex

gene expression networks (14,15).

lncRNAs are a diverse group of transcripts that are

>200 nucleotides in length, and lack protein-coding potential.

Despite their inability to code for proteins, lncRNAs are emerging

as critical regulators of gene expression. They modulate chromatin

structure, influence transcriptional activity and participate in

post-transcriptional regulatory events. Notably, numerous lncRNAs

function as molecular sponges for miRNAs by sequestering them away

from their target mRNAs and thereby modulating downstream signaling

pathways (16,17). Recent advances in single-cell

sequencing have elucidated the cell type-specific expression and

function of lncRNAs, reinforcing their importance in both

physiological and pathological contexts (18).

Collectively, the interplay between mRNAs, miRNAs

and lncRNAs forms the backbone of the RNA regulatory network,

ensuring precise control over gene expression in both normal

cellular processes and in diseases such as cancer.

Theoretical basis of the ceRNA

network

The ceRNA hypothesis, first proposed in 2011, has

fundamentally reshaped the understanding of post-transcriptional

gene regulation. This model posits that RNA molecules containing

shared miRNA response elements (MREs) can compete for binding to

miRNAs, thereby influencing the stability and translational

efficiency of target mRNAs (16).

In essence, RNA transcripts, including mRNAs, lncRNAs and

pseudogene-derived RNAs, can function as ‘molecular sponges’,

sequestering miRNAs and reducing their availability to other

targets, thus indirectly modulating gene expression across a

regulatory network.

Several factors determine the efficacy of ceRNA

interactions. The foremost among these is the relative abundance of

the competing RNAs, whereby highly expressed ceRNAs are more likely

to effectively bind and sequester miRNAs. This concept is

formalized in the ‘miRNA sponge threshold hypothesis’, which posits

that only ceRNAs expressed above a certain quantitative threshold

can exert functional competition. Mathematical models have

substantiated this hypothesis, demonstrating non-linear regulatory

outcomes in response to ceRNA concentration (19).

In addition to transcript abundance, the number and

binding affinity of MREs within each RNA molecule shape ceRNA

regulatory capacity. For instance, transcripts harboring multiple

high-affinity sites for a given miRNA may be more susceptible to

ceRNA-mediated modulation than those with fewer or weaker binding

motifs (17,20). Furthermore, subcellular

localization plays a critical role, as ceRNA interactions are

spatially restricted to cellular compartments where miRNAs and

their targets are co-localized.

Emerging evidence has reinforced the biological

relevance of ceRNA networks, particularly in the context of cancer.

These interactions have been linked to tumor proliferation,

metastasis, immune evasion and therapeutic resistance.

Context-specific ceRNA interactions have been identified in breast,

liver, lung, pancreatic and brain cancers, demonstrating diverse

regulatory roles across tumor types (17,21,22).

A comprehensive overview of these lncRNA-miRNA interactions in

various cancers further underscores their central regulatory role

and translational potential (23).

CeRNA axes discovered in discovery sets have

reproduced prognostic separation in independent patient cohorts,

including proliferation-linked networks in lung adenocarcinoma

(LUAD) and colon cancer (24,25).

Nevertheless, the generalizability of the ceRNA

model across all cancer types remains under debate. Increasing

evidence suggests that ceRNA network robustness is highly

context-dependent, varying substantially between tumor types.

Factors such as tissue-specific RNA expression, tumor subtype

heterogeneity and the tumor microenvironment (TME) can constrain or

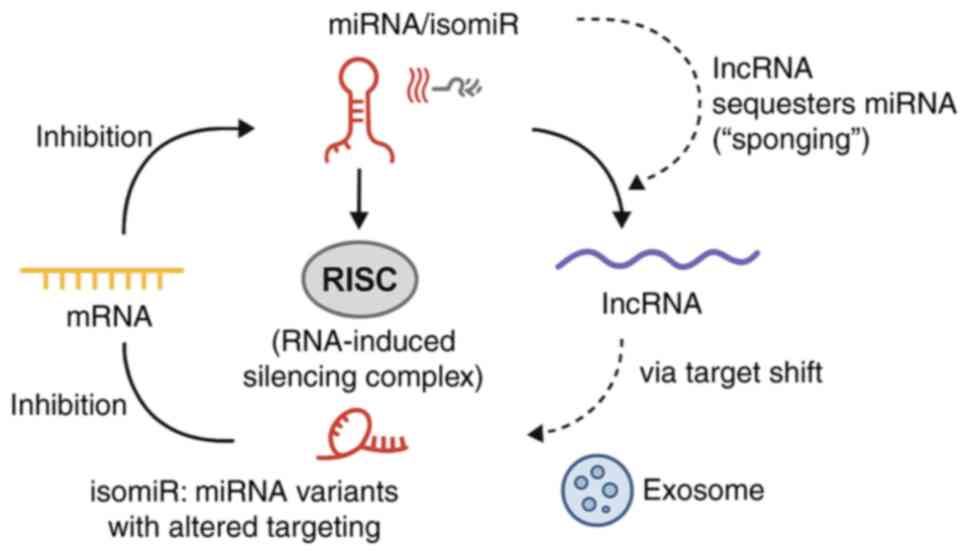

enhance ceRNA-mediated regulation. These foundational interactions

within the RNA regulatory landscape are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Generation of isomiRs and their

regulatory importance

Canonical miRNA loci produce multiple sequence

variants, termed isomiRs, through imprecise cleavage by

Drosha/Dicer and post-transcriptional tailing or trimming (such as

adenylation/uridylation) (17,20,23).

These edits alter the length and sequence at the 5' or 3' ends.

Alterations at the 5' end are particularly consequential because

they shift the seed (nts 2-8), thereby redefining the target

repertoire and potentially rewiring regulatory programs. By

contrast, numerous 3' variants primarily influence Argonaute

loading, stability or binding affinity without altering seed

identity (20).

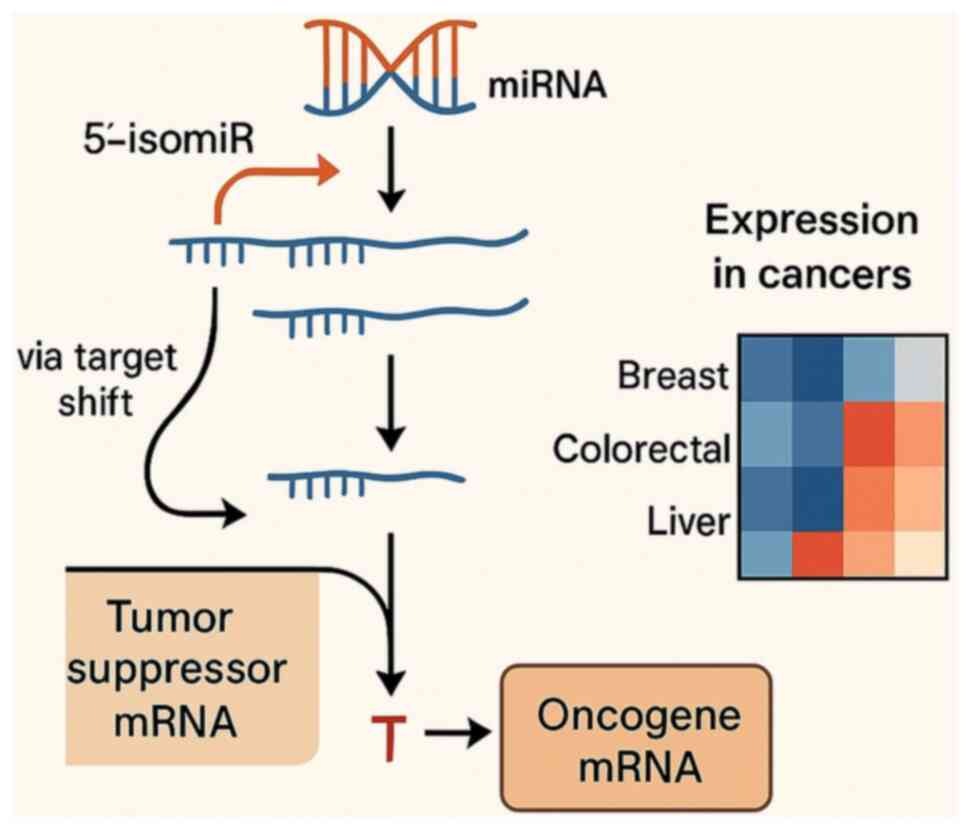

In cancer, isomiRs show context-specific expression

relative to canonical miRNAs and to matched normal tissues,

implicating them in tumor-type-dependent pathway control (17,20).

They may also reshape ceRNA competition by engaging distinct MREs,

modifying post-transcriptional regulation in a manner that depends

on both sequence and tissue context. This principle is illustrated

in Fig. 2, using 5'-isomiRs with

notable tumor-normal differences in three TCGA cohorts, including

breast (BRCA), colorectal (COAD/READ) and liver (LIHC), displayed

as z-scored log2(RPM+1) heatmaps. The cancer-type-specific patterns

oppose a pan-cancer stereotype and instead support selective

deployment of 5'-isomiRs across tumor contexts.

Despite their promise, the functional independence

of numerous isomiRs remains debated. Some 5'-shifted variants

exhibit distinct targetomes and phenotypes, whereas others appear

largely redundant with their canonical counterparts (20,26).

Most evidence to date is correlative or prediction-based. Rigorous

validation such as isoform-resolved CLIP/CLASH, seed-swap

reporters, rescue assays and locus-specific perturbations are still

needed to establish causal mechanisms and to assess biomarker or

therapeutic value at isoform resolution.

3. Role of the RNA regulatory network in

cancer occurrence and progression

RNA regulatory networks play a pivotal role in

tumorigenesis by modulating important cellular processes such as

cell cycle control, proliferation, apoptosis and the TME. The

interplay among various RNA species, including mRNAs, miRNAs,

lncRNAs and other ncRNAs, provides a complex regulatory framework

that influences cancer initiation, progression and therapeutic

response. A comprehensive understanding of these networks not only

elucidates the molecular mechanisms driving cancer but also

highlights potential targets for intervention.

RNA regulatory networks in cell cycle,

proliferation and apoptosis

Dysregulation of the cell cycle and proliferation

pathways is a hallmark of cancer. Under physiological conditions,

cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and their inhibitors

coordinate orderly progression through the cell cycle. Disruptions

in these circuits can lead to uncontrolled cell division. RNA

regulatory networks, particularly those involving ceRNA

interactions, modulate the expression of these critical regulators.

For example, miRNAs targeting cyclin genes (such as CCNA2 and

CCND1) or CDK inhibitors (such as p21 and p27) can alter cell cycle

dynamics, thereby promoting or inhibiting tumor growth (27).

In parallel, these RNA networks also regulate

apoptosis by balancing the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic

factors such as BCL2, BAX and CASP9. Dysregulation of RNA-mediated

controls may tip this balance toward survival, enabling cancer

cells to evade programmed cell death and develop therapeutic

resistance. Certain lncRNAs have been shown to stabilize mRNAs

encoding anti-apoptotic proteins, further contributing to tumor

progression (28).

MiRNA signatures that regulate these circuits (for

example, miR-21 and miR-145) correlate with recurrence and survival

in retrospective/prospective cohorts and in liquid-biopsy studies,

underscoring translational relevance (29,30-33).

Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that isomiRs,

which are functionally diverse miRNA isoforms, can fine-tune RNA

regulatory effects by altering target specificity, thereby

influencing processes such as proliferation and apoptosis in a

context-dependent manner (29).

RNA interactions and regulation of the

TME

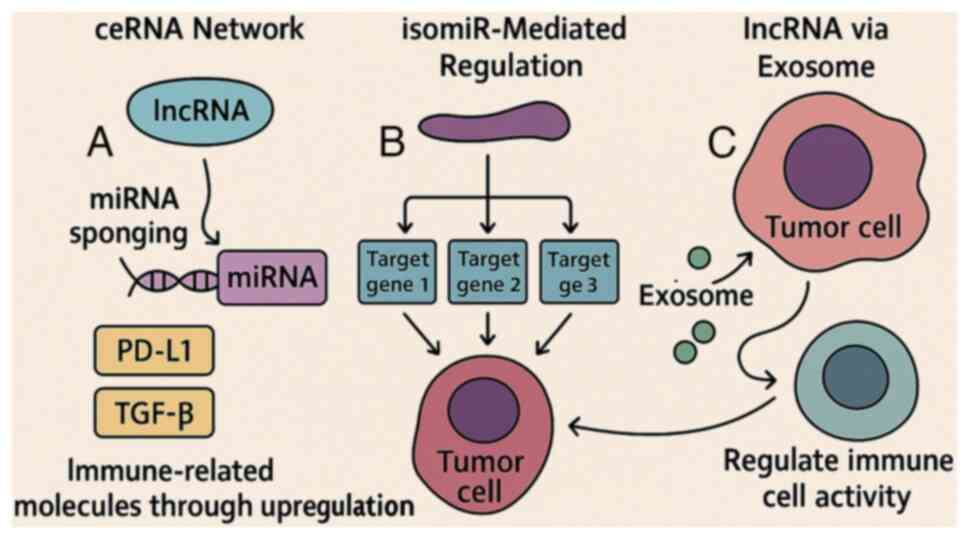

Beyond their roles in intrinsic tumor cell

functions, RNA regulatory networks profoundly influence the TME.

ncRNAs, including miRNAs and lncRNAs, are not only active

intracellularly, but can also be secreted via extracellular

vesicles (such as exosomes) to mediate intercellular communication

with immune cells, fibroblasts and endothelial cells (34,35).

These interactions affect immune infiltration, cytokine production,

angiogenesis and extracellular matrix remodeling, creating a

microenvironment conducive to tumor progression (36).

For instance, some miRNAs suppress T-cell activation

or promote the polarization of macrophages toward an

immunosuppressive M2 phenotype, facilitating immune escape

(28). Similarly, lncRNAs can act

as decoys or scaffolds that sequester transcription factors and

chromatin remodelers involved in immune regulation. This

multilayered regulatory network underscores the potential of

targeting RNA interactions to enhance immunotherapy and overcome

resistance. Ongoing clinical studies are exploring strategies to

disrupt oncogenic RNA circuits or restore tumor-suppressive RNAs to

therapeutically reprogram the TME (37).

These RNA-mediated mechanisms of immune modulation

are schematically summarized in Fig.

3.

Case studies in various cancer

types

LUAD: ceRNA networks in cell cycle regulation and

prognosis. In LUAD, ceRNA networks have been implicated in

regulating cell cycle-related gene expression and tumor

proliferation, with prognostic importance. A representative ceRNA

axis involved the lncRNA VPS9D1-AS1, miR-30a-5p and downstream

targets such as CCNA2, KIF11 and MKI67(24). VPS9D1-AS1 acts as a molecular

sponge for miR-30a-5p, thereby upregulating key mitotic regulators

and proliferation markers. This dysregulation contributes to

unchecked tumor growth. Notably, large-scale bioinformatics

analyses have highlighted these ceRNA circuits as potential

biomarkers for patient stratification and therapeutic

targeting.

Cholangiocarcinoma: SNHG6/miR-101-3p/E2F8

axis. In cholangiocarcinoma, the lncRNA SNHG6 serves as

a ceRNA that sequesters miR-101-3p, leading to derepression of the

transcription factor E2F8, which promotes cell cycle

progression. This ceRNA axis enhances proliferation, migration and

angiogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma cells, supporting its role in

aggressive tumor phenotypes (38).

The SNHG6/miR-101-3p/E2F8 pathway exemplifies the mechanisms

by which ceRNA dysregulation facilitates oncogenic processes

through post-transcriptional control.

Other cancer types: Breast, colorectal and liver

cancer. RNA regulatory networks are also perturbed in other

cancer types. In breast cancer, lncRNAs and miRNAs jointly modulate

the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, contributing to metastasis and

therapy resistance (39-41).

In colorectal cancer, the LCMT1-AS2/miR-454-3p/RPS6KA5 ceRNA

axis functions as a prognostic indicator of poor survival (25). In hepatocellular carcinoma, ncRNAs

orchestrate PI3K/AKT signaling cascades to influence angiogenesis

and immune evasion (42,43).

These case studies underscore the context-specific

architecture and functional diversity of ceRNA networks across

different malignancies (44).

Despite shared mechanisms, such as lncRNA sponging and

miRNA-mediated repression, the biological outcomes are highly

dependent on tumor type, target gene context and network topology.

Understanding these disease-specific ceRNA circuits is important

for developing targeted RNA-based interventions in precision

oncology. These differences in ceRNA network strength, biological

relevance and experimental validation across cancer types are

systematically summarized in Table

I.

| Table IComparative effectiveness of ceRNA

networks across cancer types. |

Table I

Comparative effectiveness of ceRNA

networks across cancer types.

| First author/s,

year | Cancer type | Regulatory

strength | Key influencing

factors | Representative

ceRNA axis | Functional

validation method | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zhang et al,

2014 | Breast cancer | High | High lncRNA and

miRNA abundance |

HOTAIR/miR-331-3p/HER2 | In vitro

knockdown and luciferase reporter assays | (89) |

| Poliseno et

al, 2010 | Glioblastoma | Low | Low miRNA levels,

high heterogeneity |

PTENP1/miR-19b/PTEN | Bioinformatics

analysis, low experimental confirmation | (90) |

| Chen et al,

2021 | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Medium-High | High lncRNA

expression, immune complexity |

LINC00160/miR-132/AKT1 | Animal models and

expression rescue experiments | (91) |

| Xie et al,

2020 | Pancreatic

cancer | Low | Immunosuppressive

tumor microenvironment, scarce lncRNAs |

MALAT1/miR-200c/ZEB1 | Limited functional

studies | (92) |

4. Application of RNA regulatory networks in

cancer diagnosis and prognosis

As the understanding of RNA regulatory networks

improves, their clinical implications in oncology have become

increasingly evident. From identifying prognostic markers to

guiding molecular classification and precision medicine, RNA-based

tools hold promise for improving cancer diagnosis, treatment and

patient outcomes.

Screening of prognostic markers based

on RNA networks

RNA molecules, including mRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs and

circRNAs, have gained traction as diagnostic and prognostic

biomarkers due to their tissue-specific expression patterns,

stability in biofluids and critical regulatory roles in

tumorigenesis (45). In

particular, panels of differentially expressed RNAs have been

correlated with disease stages and patient survival across various

cancer types (30,31). For instance, specific lncRNAs have

been linked to metastasis and recurrence in breast and colorectal

cancers, while unique miRNA signatures have been proposed as early

detection markers for lung and pancreatic cancers (32). Multi-center studies of circulating

RNAs report diagnostic AUCs in the ~0.80-0.90 range for several

malignancies, and tissue lncRNA/miRNA panels track stage,

recurrence and survival (30,31,33,45-47).

Moreover, circulating RNAs, those detectable in

plasma, serum and exosomes, offer a minimally invasive means of

cancer detection and monitoring (33). By quantifying changes in RNA

expression, clinicians can potentially identify high-risk patients,

track tumor progression and evaluate therapeutic response. Despite

these advances, larger, multicenter clinical studies are needed to

validate the robustness, reproducibility and clinical utility of

RNA-based prognostic panels before they can be widely implemented

in routine practice (48).

Role of RNA molecules in molecular

typing and precision medicine

RNA signatures have proven invaluable for the

molecular classification of tumors, which is a key step in

precision medicine. For example, gene expression profiling has led

to the identification of distinct subtypes in breast cancer (such

as luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched and basal-like) and the

stratification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma into molecularly

defined categories (49). These

classifications guide therapeutic decisions, such as the use of

targeted therapies (such as HER2 inhibitors in HER2-enriched breast

cancer) and immunotherapies for tumors harboring specific

expression profiles.

Additionally, RNA-based molecular typing extends

beyond mRNA to include ncRNAs. LncRNAs and miRNAs have emerged as

critical regulators of oncogenic pathways and have been associated

with tumor subtypes, therapeutic resistance and disease outcomes

(46). Integrating RNA signatures

into diagnostic frameworks enables clinicians to tailor treatment

regimens to the unique molecular features of tumors of individual

patients, improving efficacy and minimizing toxicity (47).

Clinical detection technology and its

limitations

Various technologies have been developed to harness

RNA molecules for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. High-throughput

sequencing (RNA-seq) enables comprehensive transcriptome profiling,

allowing detection of novel transcripts and splicing variants

(50). Microarray-based platforms

and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR are widely used for

validating candidate RNA biomarkers due to their ease of use and

cost-effectiveness (51). More

recently, digital droplet PCR (ddPCR) has gained popularity for its

high sensitivity in detecting low-abundance circulating RNAs

(52).

Despite these advances, challenges persist.

Variability in sample collection, RNA extraction and data analysis

can affect the sensitivity and reproducibility of RNA-based

diagnostics. Standardization of protocols and optimization across

pre-analytical steps are important (53). Furthermore, tumor heterogeneity and

the dynamic nature of RNA expression require repeated sampling to

capture the evolving transcriptome. Large, multicenter clinical

studies and robust bioinformatics pipelines are crucial to ensure

the clinical utility of RNA-based tests.

Clinical applications and

translational progress

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting

RNA-based biomarkers and regulatory networks in cancer biology,

their clinical translation remains limited. However, several

RNA-targeted therapeutics have made notable strides. For instance,

Givosiran and Inclisiran, two small interfering RNA (siRNA) drugs

approved by the FDA, have demonstrated the feasibility of RNA-based

therapy in clinical settings, although outside oncology. In the

cancer field, MRX34, a liposomal mimic of the tumor-suppressive

miR-34a, was the first miRNA therapeutic to enter clinical trials,

marking a milestone despite its early termination (54).

In parallel, RNA expression profiling has become a

valuable tool in molecular subtyping and precision medicine. For

example, the PAM50 RNA panel informs hormone and HER2-targeted

therapies in breast cancer based on intrinsic molecular subtypes

(49). However, several

technological barriers still hinder the routine clinical adoption

of RNA-based diagnostics. Although ddPCR offers high sensitivity

for detecting low-abundance RNAs in liquid biopsies, its limited

multiplexing capability and cost pose challenges for large-scale

implementation (52). Similarly,

while RNA sequencing provides comprehensive transcriptomic data,

issues such as batch effects, variable library preparation and

complex data analysis reduce inter-laboratory reproducibility

(51).

To address these challenges, emerging strategies

focus on standardizing workflows, minimizing RNA input requirements

and developing FDA-aligned diagnostic guidelines. These

developments represent a critical transition from bench to bedside,

underscoring the translational promise of RNA regulatory networks

in precision oncology.

5. Strategies and prospects of RNA

regulatory networks in cancer treatment

RNA regulatory networks have become attractive

therapeutic targets in oncology. By modulating miRNAs, lncRNAs and

their downstream effectors, it may be possible to slow tumor

progression, overcome drug resistance and improve outcomes

(55,56).

Therapeutic strategies targeting RNA

networks

miRNA/lncRNA mimics and inhibitors restore

tumor-suppressive functions or block oncogenic ncRNAs, using

synthetic oligonucleotides such as mimics, antagomiRs and ASOs

(57-59).

Modulating ceRNA interactions represents another avenue:

Downregulating oncogenic lncRNAs or other competing RNAs can

liberate tumor-suppressive miRNAs to repress their targets

(60).

Clinical status and delivery

lessons

The liposomal miR-34a mimic MRX34 reached

first-in-human testing but was terminated for immune-related

toxicities, highlighting the need to minimize innate immune

activation and to optimize delivery and preclinical toxicology

(61). By contrast, siRNA agents

have demonstrated that careful carrier design enables

tissue-specific delivery with manageable safety, as illustrated by

patisiran in non-oncology indications (12) and by RNA nanoparticles with

favorable biodistribution and conditional endosomal escape

(13). Oncology-focused programs

span locoregional depots such as siG12D-LODER for KRAS^G12D

pancreatic cancer (62,63), systemically delivered LNP siRNAs

such as DCR-MYC (64,65), and newer platforms exemplified by

the GSTP-targeting NBF-006 evaluated in KRAS-mutant NSCLC (66,67).

Collectively, these data emphasize the centrality of delivery

engineering, target and context selection, and early immune-risk

mitigation, which are elaborated below.

6. Existing problems and limitations

While RNA regulatory networks present promise in

cancer research and treatment, several challenges remain in

understanding their full potential. Data integration, technical

limitations and the need for more refined experimental approaches

hinder the progress in this field. Addressing these issues will be

crucial for optimizing RNA-based therapeutic strategies and

improving the clinical application of RNA regulatory networks in

oncology.

Challenges of data integration and

network construction in existing studies

Integrating high-throughput RNA sequencing data

remains a major challenge due to the complexity of transcriptomic

interactions. RNA molecules, including mRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs and

isomiRs, form intricate, context-dependent networks that vary

across tissue types, disease stages and microenvironments. A single

RNA species may regulate or interact with multiple targets in

diverse ways. However, most current reconstruction methods rely on

statistical correlations rather than causal or directional

relationships, resulting in oversimplified or incomplete network

models (68). While numerous

computational tools have been developed to predict miRNA-lncRNA

interactions, such as correlation-based and

sequence-complementarity methods, these tools often produce

inconsistent outputs and require further experimental validation

(69).

The lack of standardized computational pipelines and

network inference frameworks further impedes data integration and

cross-platform comparability. Although numerous tools have been

developed, few can integrate multi-omics datasets (such as RNA-seq

with ATAC-seq) at the single-cell level to construct cell

type-specific regulatory maps (70). Emerging tools such as IReNA and

pySCENIC attempt to address these issues by incorporating

transcription factor motifs, chromatin accessibility and regulatory

logic into network inference (71). However, robust integration of

large-scale omics data and reproducibility across computational

platforms remain unresolved challenges.

Moreover, scRNA-seq faces limitations in detecting

low-abundance RNAs such as miRNAs and lncRNAs. These datasets are

also prone to batch effects and technical noise, affecting

reproducibility and interpretation. Although multi-omics

integration tools are advancing, fully capturing dynamic RNA

regulatory networks at single-cell resolution remains an ongoing

area of research (10).

Technical and biological problems in

isomiR research

IsomiRs, the variant forms of miRNAs, have garnered

increasing attention for their ability to expand the miRNA

regulatory landscape. However, several technical and biological

challenges hinder their accurate identification and functional

characterization. A major limitation lies in the resolution of

current sequencing technologies, which may fail to detect

low-abundance isomiRs or differentiate between closely related

isoforms, particularly those with 5' seed shifts, which can alter

target specificity (26).

Furthermore, incomplete or inconsistent annotation in public

databases hampers reliable mapping and interpretation (20).

Biologically, the roles of isomiRs in cancer remain

only partially understood. Variants that differ at the 5' end may

possess novel seed sequences, leading to distinct mRNA targeting

and potentially divergent effects on oncogenic signaling pathways

(17). Functional validation of

such isomiRs is still limited, and systematic studies across

different tissues and tumor types are required to determine their

contribution to tumorigenesis, metastasis and therapy resistance.

Advances such as dual-index library construction for reproducible

isomiR sequencing (26), along

with isomiR-specific databases [such as isomiRTar (72) and TIE], are beginning to address

some of these limitations and offer promising platforms for future

isomiR discovery and clinical application.

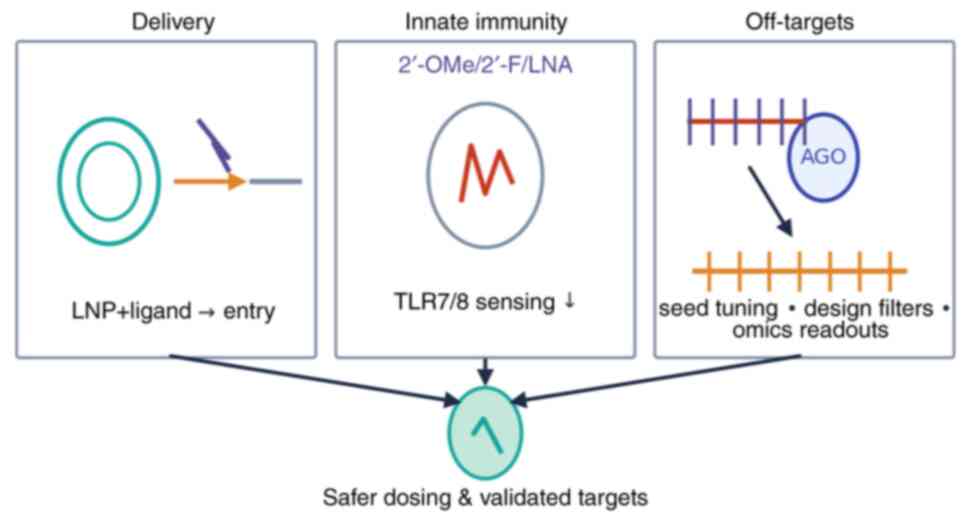

In the present review, three recurrent challenges

that have hampered the clinical success of RNA therapeutics in

oncology (delivery efficiency, innate immune activation, and

off-target effects) were highlighted, and each paired with

evidence-informed mitigation strategies.

Delivery. Effective delivery to tumor tissue

remains a major obstacle. For systemically administered agents, the

composition of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), including the

pKa of ionizable lipids, helper lipids, and PEG-lipids,

critically influences stability, cellular uptake and endosomal

escape (73-75).

Clinical experience demonstrates that rational LNP design can

successfully translate to humans, as exemplified by patisiran,

which achieved robust hepatic gene silencing using an MC3-based LNP

and exhibited a manageable safety profile (12). Tumor selectivity can be further

enhanced through ligand-mediated targeting (for example, GalNAc,

antibodies, or aptamers) or via locoregional depot systems.

Oncology case studies (for example, siG12D-LODER and DCR-MYC) have

been described in Section 5, illustrating how delivery mode, namely

local depot versus systemic LNP, critically shapes tumor exposure

and clinical feasibility (62-65).

Practical strategies to improve delivery include refining ionizable

lipid structures, modulating PEG content, incorporating validated

targeting ligands, utilizing localized administration where

possible, and prioritizing the assessment of tumor exposure and

endosomal escape during early development (68-78).

Innate immune activation. The case of MRX34,

which was discontinued despite evidence of target engagement,

highlights the clinical consequences of uncontrolled innate immune

stimulation, often mediated through endosomal Toll-like receptors

(for example, TLR7/8) (61).

Mitigation approaches incorporate sequence ‘de-immunization’ using

chemically modified nucleotides (such as 2'-OMe, 2'-F, or LNA),

optimized PEGylation strategies, and early in vitro

screening using human whole-blood assays or PBMC cultures to

quantify cytokine release (79,80).

These measures reduce TLR-dependent immune recognition, dampen

excessive cytokine production, and help establish safer starting

doses and premedication regimens for first-in-human trials

(63,79,80).

Off-target effects. siRNA candidates can

induce seed region-mediated off-target silencing via interactions

with 3' UTRs, leading to unintended transcriptome-wide effects

(81). Comprehensive off-target

profiling involves coupling AGO2-centered methods (for example,

HITS-CLIP or PAR-CLIP) with dose-responsive transcriptomics

(RNA-seq) and proteomics. Computational filtering and CRISPR-based

validation help establish causal relationships between observed

effects and off-target binding (82,83).

Design-based solutions include modifying the seed sequence,

introducing chemical modifications that reduce miRNA-like activity,

and selecting guide strands with minimal predicted off-target

potential in relevant cellular models (81-83).

Functional verification of

isomiRs

Demonstrating function requires evidence of seed

dependence, direct target engagement and a measurable cellular

consequence in the relevant context. To establish robust evidence

for isomiR-mediated targeting, a multi-tier framework can be

applied. Initial screening with dual-luciferase reporter assays

comparing wild-type versus seed-mutant 3'UTRs, including canonical

and 5'-shifted isomiRs, provides seed-specific activity, while

seed-reversion rescues confirm specificity (61). Genetic perturbation at the

pri-miRNA locus (CRISPRi/a or base editing) modulates isomiR

production and can be linked to phenotypic outcomes using pooled

single-cell transcriptomics such as Perturb-seq or CROP-seq

(79,80). Direct binding is then established

by AGO-CLIP (HITS-CLIP or PAR-CLIP) (61), and functional repression verified

by dose-responsive RNA-seq and quantitative proteomics (61). At higher resolution, these steps

can be integrated with single-cell multi-omics to assign effects to

specific cell states (68,69,73).

Seed specificity can be assessed by comparing

canonical and 5'-shifted variants in dual-luciferase assays and by

reversing the altered seed (81).

Causality in living cells can be tested via CRISPR-based

perturbation of isomiR production or processing, with single-cell

transcriptomic readouts when cell-state resolution is required.

Physical binding to predicted sites is evaluated with AGO-centered

CLIP (HITS-CLIP or PAR-CLIP), and downstream impact is quantified

under therapeutically relevant exposures using dose-ranged RNA-seq

and quantitative proteomics (82,83).

Implications and new directions for

future cancer treatment strategies

Despite ongoing challenges, RNA-based therapeutics

are advancing rapidly, driven by innovations in molecular design,

delivery systems and target specificity. An increasing number of

therapeutic agents, including miRNA mimics, lncRNA inhibitors and

small molecules that modulate RNA-RNA or RNA-protein interactions,

are under active development. These approaches offer fine-tuned

control over key pathways such as cell proliferation, apoptosis and

immune regulation, particularly in tumors resistant to traditional

treatments (60).

At the same time, progress in RNA drug delivery is

expanding the clinical applicability of these strategies. LNP

formulations, ligand-targeted conjugates and chemically modified

oligonucleotides are being optimized to enhance stability, reduce

off-target effects and achieve tumor-specific accumulation. The

success of RNA-based drugs in non-cancer diseases, such as

Patisiran for transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis, provides valuable

insights for oncology applications.

In the future, RNA therapeutics are hypothesized to

integrate more deeply into combination regimens alongside

immunotherapies, targeted therapies and radiotherapy. Such

synergistic approaches may improve treatment efficacy while

minimizing systemic toxicity. Moreover, advances in biomarker

discovery, particularly RNA-based expression signatures, will

facilitate patient stratification and response monitoring,

supporting a shift toward more personalized cancer care.

Ultimately, the continued refinement of RNA

therapeutics, along with robust clinical validation and regulatory

frameworks, will be important to fully realize their potential in

precision oncology.

Emerging frontiers: Hot topics in RNA

regulatory network research

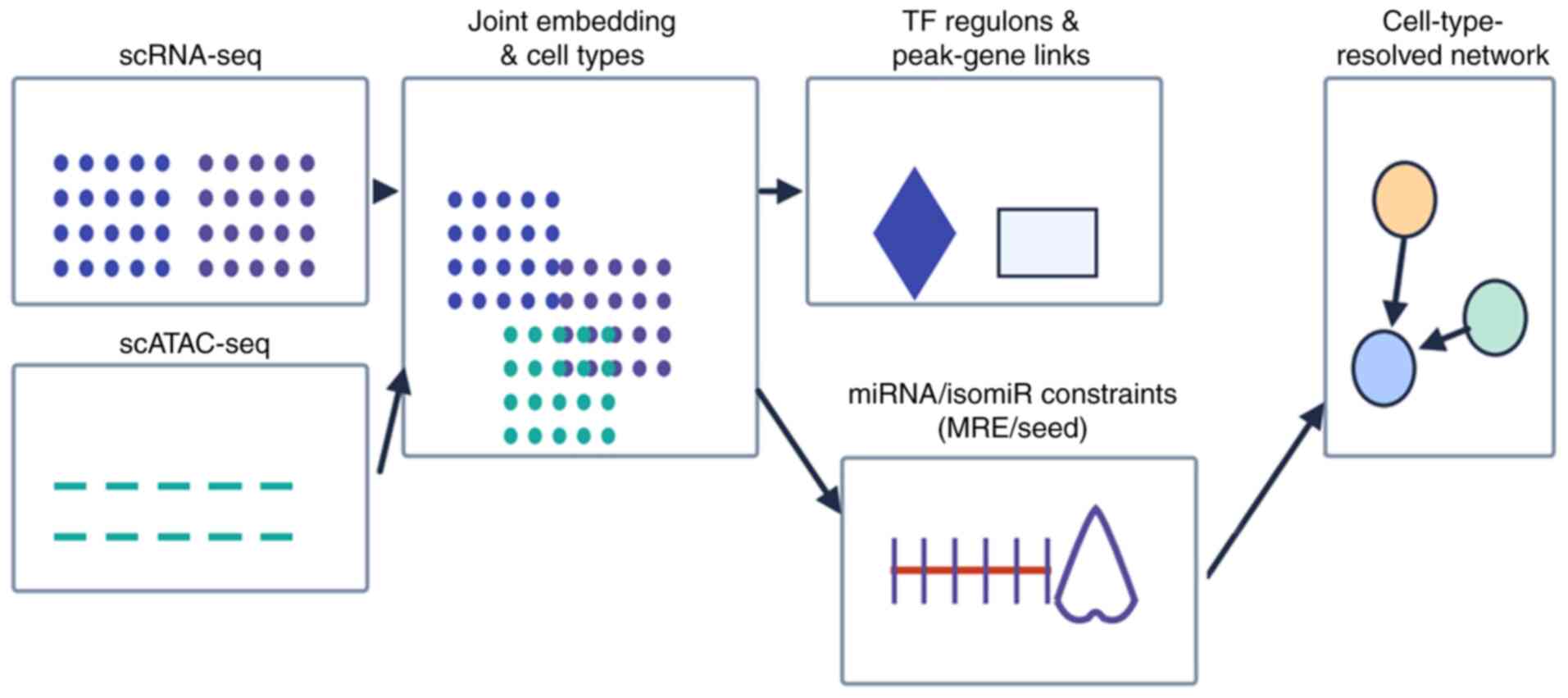

Single-cell multi-omics for high-resolution

regulatory mapping. A compact workflow for single-cell

multi-omics integration [scRNA-seq + single-cell assay for

transposase-accessible chromatin (scATAC-seq) ± spatial] is

provided in Fig. 4, from joint

embedding and TF/peak-gene linking to MRE-constrained edge

inference and cell type-resolved networks.

Concise description of single-cell multi-omics

integration. ScRNA-seq and scATAC-seq datasets were

quality-controlled and batch-corrected to obtain a joint embedding

and a reproducible cell-type map (68,69).

Chromatin peaks are linked to genes by correlating accessibility

with expression within cell types and by motif/footprint analysis

to define transcription-factor regulons with per-cell activity

scores (71). Integrated

regulatory networks are inferred with methods that couple scRNA-seq

and chromatin-accessibility constraints (such as IReNA) (70). Candidate ceRNA/isomiR relationships

are then filtered by the presence of microRNA-response elements

and, where available, orthogonal support from isomiR-target

resources (72). When spatial

transcriptomics are available, edges that co-localize within the

TME are prioritized. Robustness is assessed by stability across

donors/batches and held-out performance (68,73).

Single-cell sequencing technologies, particularly

when integrated with transcriptomic, epigenomic and proteomic

modalities (such as scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq and CITE-seq), are

transforming the current understanding of RNA regulatory networks

in cancer. These tools enable the resolution of cell type-specific

expression profiles and uncover spatial and temporal heterogeneity

in ceRNA and isomiR interactions, especially within the TME

(10,84). Such fine-grained insights are

crucial for identifying rare subpopulations that drive therapy

resistance, metastasis or immune escape.

Previous efforts have also applied single-cell

spatial transcriptomics to validate ceRNA networks in situ,

revealing topological constraints and microenvironmental influences

on RNA-based regulation (16,19,23).

These approaches provide unprecedented opportunities to reconstruct

RNA interaction maps at a cellular resolution.

Emerging multi-omics integration strategies are

moving beyond single-cell approaches to provide robust, pan-cancer

insights into post-transcriptional regulation. Representative cases

illustrate this evolution:

In cholangiocarcinoma, integrated transcriptomic and

proteomic profiling, combining RNA-seq with quantitative mass

spectrometry, has uncovered functional isomiR-mediated networks.

Predictions of isomiR-target interactions were corroborated by

corresponding protein-level changes, highlighting cross-regulatory

RNA crosstalk and prioritizing mechanistically relevant edges for

experimental validation (21).

Pan-cancer integrative frameworks have further

enabled the identification of consensus ceRNA networks across large

cohorts. By aggregating miRNA-lncRNA-mRNA data from multiple tumor

types, these approaches derive robust cross-cancer regulatory

edges, which are subsequently evaluated through dataset stability

tests and survival analysis, offering a reproducible template for

bulk multi-omics synthesis (23,68,69).

Curated multi-omics databases now systematically

consolidate single-cell, spatial and bulk genomic data to enhance

ceRNA inference. These resources support cross-modality validation,

such as confirming co-expression in bulk datasets, spatial

co-localization in tissue maps, and recurrence of edges across

cancer types, enabling more reliable triage of candidate

interactions (10).

Additionally, constraint-guided methods that

incorporate chromatin features, such as motif accessibility,

foot-printing data, and open chromatin states, are increasing the

specificity of regulatory network inference. Although often applied

in single-cell analyses, these priors are equally valuable in bulk

multi-omics integration, where they help reduce false-positive

predictions and refine edges based on functional genomic

constraints (70,71).

CRISPR-based functional validation and network

causality. Traditional studies of RNA networks rely heavily on

correlational analyses, which limit causal inference. CRISPR-based

screening technologies, particularly CRISPR interference and

activation (CRISPRa), now offer a powerful means of interrogating

RNA function. When combined with single-cell transcriptomics (such

as Perturb-seq and CRISPRa-Perturb-seq), these tools allow

high-throughput, context-specific validation of lncRNAs, miRNAs and

ceRNA nodes (9,85). These screens have successfully

identified key regulatory elements that contribute to drug

resistance and tumor progression, enhancing the biological

credibility of proposed networks. As RNA-targeted therapies

continue to develop, such functional genomics approaches will play

a pivotal role in bridging predictive models and therapeutic

translation.

RNA structural biology and non-canonical

regulatory layers. Beyond sequence-level regulation, emerging

evidence points to the importance of RNA secondary and tertiary

structures, especially G-quadruplexes (G4s), in shaping RNA

regulatory landscapes. G4 motifs are highly stable, guanine-rich

structures found in both coding and non-coding regions, where they

influence miRNA binding, splicing and translation (17,86).

These structures can modulate ceRNA stability or alter the

seed-region recognition capacity of isomiRs, introducing novel

dimensions of regulatory control. Structure-based targeting of RNA

is gaining traction as a therapeutic strategy. Molecules that

selectively bind or stabilize RNA G4s have shown antiproliferative

effects in cancer models, offering new possibilities for

intervention (87,88). Future work may focus on

programmable modulation of such structures using CRISPR-guided

systems or synthetic ligands.

These emerging technologies, including single-cell

multi-omics, CRISPR-based functional validation and RNA

structure-focused regulation, are redefining the landscape of RNA

network research. Their integration will unlock novel therapeutic

avenues and deepen the mechanistic understanding of cancer biology

at single-cell and molecular resolutions.

Dynamic heterogeneity in RNA

regulatory networks and its regulatory mechanisms

Recent studies have revealed that cellular

heterogeneity within tumors and their microenvironments influence

the construction and function of RNA regulatory networks (10,20,33).

First, distinct cell types, such as immune cells versus tumor

cells, exhibit fundamentally different RNA network regulatory

mechanisms. Immune cells, which play key roles in antigen

presentation, cytokine secretion and immune modulation, tend to

have ceRNA networks tailored to regulating immune responses. By

contrast, tumor cells often display ceRNA networks that primarily

promote proliferation, evade immune surveillance and drive

metabolic reprogramming. For example, immune cell ceRNA

interactions are closely linked to immune response regulation,

whereas in tumor cells these networks are more frequently involved

in cell cycle and metabolic pathway regulation (37).

Furthermore, there is mounting evidence that ceRNA

networks undergo dynamic remodeling during tumor progression. In

early-stage tumors, ceRNA networks may serve to maintain a balance

between proliferation and apoptosis. However, as tumors advance,

these networks can be restructured to support metastasis, drug

resistance and immune evasion. In LUAD, key ceRNA components have

been observed to undergo notable changes in both expression and

interaction patterns as the disease progresses, indicating a

dynamic adjustment of the network architecture over time (24).

Lastly, integrating time- and space-resolved

expression data is crucial for reconstructing accurate RNA

regulatory maps. Single-cell multi-omics and spatial

transcriptomics technologies now enable researchers to capture RNA

expression dynamics across different tumor regions and time points.

For instance, the LnCeCell 2.0 database leverages such data to

reveal the spatiotemporal specificity of ceRNA interactions among

various cell types, providing powerful tools for dissecting the

complex heterogeneity of tumor tissues (10).

Collectively, these insights underscore the

importance of considering both cellular and temporal heterogeneity

in RNA regulatory network analyses. A deeper understanding of these

dynamic changes not only enriches the knowledge of tumor biology

but also informs the development of personalized therapeutic

strategies based on the spatiotemporal modulation of gene

expression. These considerations are consolidated in Fig. 5, which links the major constraints

to practical mitigation levers and validation readouts.

7. Future prospects and emerging

directions

The rapid evolution of RNA regulatory research is

opening new frontiers in cancer biology and therapy. While marked

progress has been made in identifying the components and functions

of RNA networks, several challenges remain. These include the need

for robust, context-specific functional validation, improved

delivery of RNA-targeted therapeutics and standardization in data

integration across multi-omics platforms.

In the future, a key direction may be the

convergence of mechanistic insight and clinical application.

High-resolution technologies such as single-cell multi-omics and

CRISPR-based screening may continue to play a vital role in

decoding network dynamics and identifying cell-specific

vulnerabilities. However, their full translational potential

depends on the development of clinically viable tools for

manipulating RNA interactions in vivo, including

programmable RNA editors, structure-targeted ligands and

combination therapies that modulate multiple layers of regulation

simultaneously.

Another promising avenue lies in integrating

RNA-based approaches with other therapeutic modalities, such as

immunotherapy and metabolism-targeting drugs. RNA biomarkers and

regulatory signatures may enable more refined patient

stratification and dynamic monitoring of treatment response,

supporting the vision of adaptive, personalized oncology.

Ultimately, the future of RNA regulatory network

research hinges on the ability of researchers to move from

descriptive models to predictive, actionable frameworks. This may

require not only technological innovation but also

interdisciplinary collaboration across molecular biology,

bioinformatics, structural biology and clinical oncology. With

continued progress, RNA networks may shift from being viewed as

passive readouts of gene activity to becoming active therapeutic

blueprints that guide next-generation cancer treatment.

Design implications begin with a biology-driven

approach: Prioritizing clinical evaluation in adjuvant or minimal

residual disease settings, or other immune-permissive contexts, to

maximize therapeutic responsiveness (12,13,79,80).

When monotherapy cytotoxicity is insufficient, intentional

combination strategies, such as pairing RNA-based agents with

checkpoint inhibitors or pathway-sensitizing therapeutics, should

be employed (66,67,79,80).

Emphasis should be placed on target quality and dependency rather

than tumor mutational burden alone, favoring high-quality

neoantigens or functionally validated targets (79,80).

Biomarker plans must be pre-specified, integrating

diagnostic-enrichment-pharmacodynamic (D-E-P) chains and systematic

tissue or ctDNA sampling into the trial's statistical design

(12,13). Furthermore, innate immune sensing

should be de-risked prior to first-in-human studies through

optimized sequence chemistry, formulation, and delivery routes, as

underscored by the clinical experience with MRX34, where

immune-related toxicity led to discontinuation despite evidence of

target engagement (61). By

contrast, previous systemic siRNA programs demonstrate that careful

carrier tuning and chemical modification can markedly improve

uptake and endosomal escape while mitigating immunostimulatory

risks (64,67).

8. Conclusion

RNA regulatory networks offer compelling

opportunities to improve cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment,

yet translation is constrained by challenges in data integration,

context-specific network inference, delivery and the isoform-level

biology of regulators such as isomiRs. New modalities including

single-cell multi-omics and CRISPR-based functional genomics are

enabling causal mapping and more reliable biomarkers and

targets.

Real-world experience points to clear design rules

for RNA therapeutics: Optimize delivery, proactively mitigate

innate immune sensing, and build rigorous, isoform-aware

validation. If these hurdles are addressed through integrated

multi-omics and improved delivery platforms, RNA networks can

realize their potential to transform precision oncology.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Key

Research and Development Program of China (grant no.

2022YFF1301602) and the National Natural Science Foundation of

China (grant nos. 32570497, 32270442, 31872219 and 31370401).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

WR conceived the topic area, conducted literature

searches, evaluated all relevant literature, designed the research

framework, wrote the manuscript, and critically revised the

intellectual content. The author read and approved the final

version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence

tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate

content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Nurgali K, Jagoe RT and Abalo R: Adverse

effects of cancer chemotherapy: Anything new to improve tolerance

and reduce sequelae? Front Pharmacol. 9(245)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Pearce A, Haas M, Viney R, Pearson SA,

Haywood P, Brown C and Ward R: Incidence and severity of

self-reported chemotherapy side effects in routine care: A

prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 12(e0184360)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Vasan N, Baselga J and Hyman DM: A view on

drug resistance in cancer. Nature. 575:299–309. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang X, Zhang H and Chen X: Drug

resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug

Resist. 2:141–160. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Goodall GJ and Wickramasinghe VO: RNA in

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 21:22–36. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhang Y, Tang J, Wang C, Zhang Q, Zeng A

and Song L: Autophagy-related lncRNAs in tumor progression and drug

resistance: A double-edged sword. Genes Dis. 11:367–381.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Anastasiadou E, Jacob LS and Slack FJ:

Non-coding RNA networks in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:5–18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yan H and Bu P: Non-coding RNA in cancer.

Essays Biochem. 65:625–639. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mitra R, Adams C and Eischen C: Decoding

the lncRNAome across diverse cellular stresses reveals core

p53-effector pan-cancer suppressive lncRNAs. Cancer Res Commun.

3:842–859. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Guo Q, Liu Q, He D, Xin M, Dai Y, Sun R,

Li H, Zhang Y, Li J, Kong C, et al: LnCeCell 2.0: An updated

resource for lncRNA-associated ceRNA networks and web tools based

on single-cell and spatial transcriptomics sequencing data. Nucleic

Acids Res. 53:D107–D115. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Slack FJ and Chinnaiyan AM: The role of

non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell. 179:1033–1055. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O'Riordan WD,

Yang CC, Ueda M, Kristen AV, Tournev I, Schmidt HH, Coelho T, Berk

JL, et al: Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary

transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 379:11–21. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Xu C, Haque F, Jasinski DL, Binzel DW, Shu

D and Guo P: Favorable biodistribution, specific targeting and

conditional endosomal escape of RNA nanoparticles in cancer

therapy. Cancer Lett. 414:57–70. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Naeli P, Winter T, Hackett AP, Alboushi L

and Jafarnejad SM: The intricate balance between microRNA-induced

mRNA decay and translational repression. FEBS J. 290:2508–2524.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nejad C, Stunden HJ and Gantier MP: A

guide to miRNAs in inflammation and innate immune responses. FEBS

J. 285:3695–3716. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L and

Pandolfi PP: A ceRNA hypothesis: The Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA

language? Cell. 146:353–358. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Zelli V, Compagnoni C, Capelli R, Corrente

A, Cornice J, Vecchiotti D, Di Padova M, Zazzeroni F, Alesse E and

Tessitore A: Emerging role of isomiRs in cancer: State of the art

and recent advances. Genes (Basel). 12(1447)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Kim GD, Shin SI, Jung SW, An H, Choi SY,

Eun M, Jun CD, Lee S and Park J: Cell type- and age-specific

expression of lncRNAs across kidney cell types. J Am Soc Nephrol.

35:870–885. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Bosia C, Pagnani A and Zecchina R:

Modelling competing endogenous RNA networks. PLoS One.

8(e66609)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wagner V, Meese E and Keller A: The

intricacies of isomiRs: From classification to clinical relevance.

Trends Genet. 40:784–796. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Guo L, Dou Y, Yang Y, Zhang S, Kang Y,

Shen L, Tang L, Zhang Y, Li C, Wang J, et al: Protein profiling

reveals potential isomiR-associated cross-talks among RNAs in

cholangiocarcinoma. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 19:5722–5734.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Drillis G, Goulielmaki M, Spandidos DA,

Aggelaki S and Zoumpourlis V: Non-coding RNAs (miRNAs and lncRNAs)

and their roles in lymphogenesis in all types of lymphomas and

lymphoid malignancies. Oncol Lett. 21(393)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sun B, Liu C, Li H, Zhang L, Luo G, Liang

S and Lü M: Research progress on the interactions between long

non-coding RNAs and microRNAs in human cancer. Oncol Lett.

19:595–605. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yang Y, Zhang S and Guo L:

Characterization of cell cycle-related competing endogenous RNAs

using robust rank aggregation as prognostic biomarker in lung

adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 12(807367)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liang F, Xu Y, Zheng H and Tang W:

Establishing a carcinoembryonic antigen-associated competitive

endogenous RNA network and forecasting an important regulatory axis

in colon adenocarcinoma patients. J Gastrointest Oncol. 15:220–236.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang J, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Zhou J, Li J,

Zhang M, Wen S, Gao X, Zhou N, Li H, et al: Reproducible and high

sample throughput isomiR next-generation sequencing for cancer

diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 42(e15013)2024.

|

|

27

|

Rahmani F, Zandigohar M, Safavi P, Behzadi

M, Ghorbani Z, Payazdan M, Ferns G, Hassanian SM and Avan A: The

interplay between noncoding RNAs and p21 signaling in

gastrointestinal cancer: From tumorigenesis to metastasis. Curr

Pharm Des. 29:766–776. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K,

Guo J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Guo X, et al: Characterization of microRNAs

in serum: A novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and

other diseases. Cell Res. 18:997–1006. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Asangani IA, Rasheed SA, Nikolova DA,

Leupold JH, Colburn NH, Post S and Allgayer H: MicroRNA-21 (miR-21)

post-transcriptionally downregulates tumor suppressor Pdcd4 and

stimulates invasion, intravasation and metastasis in colorectal

cancer. Oncogene. 27:2128–2136. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Yu Z, Rong Z, Sheng J, Luo Z, Zhang J, Li

T, Zhu Z, Fu Z, Qiu Z and Huang C: Aberrant non-coding RNA

expressed in gastric cancer and its diagnostic value. Front Oncol.

11(606764)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ruan Z, Chi D, Wang Q, Jiang J, Quan Q,

Bei J and Peng R: Development and validation of a prognostic model

and gene co-expression networks for breast carcinoma based on

scRNA-seq and bulk-seq data. Ann Transl Med.

10(1333)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Rahman MS, Ghorai S, Panda K, Santiago MJ,

Aggarwal S, Wang T, Rahman I, Chinnapaiyan S and Unwalla HJ: Dr.

Jekyll or Mr. Hyde: The multifaceted roles of miR-145-5p in human

health and disease. Noncoding RNA Res. 11:22–37. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Yuan X, Mao Y and Ou S: Diagnostic

accuracy of circulating exosomal circRNAs in malignancies: A

meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore).

102(e33872)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wang D, Zhang W, Zhang C, Wang L, Chen H

and Xu J: Exosomal non-coding RNAs have a significant effect on

tumor metastasis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 29:16–35. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Natarelli N, Boby A, Aflatooni S, Tran JT,

Diaz MJ, Taneja K and Forouzandeh M: Regulatory miRNAs and lncRNAs

in skin cancer: A narrative review. Life (Basel).

13(1696)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Benedetti A, Turco C, Fontemaggi G and

Fazi F: Non-coding RNAs in the crosstalk between breast cancer

cells and tumor-associated macrophages. Noncoding RNA.

8(16)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhan DT and Xian HC: Exploring the

regulatory role of lncRNA in cancer immunity. Front Oncol.

13(1191913)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang H, Wang L, Tang L, Luo J, Ji H, Zhang

W, Zhou J, Li Q and Miao L: Long noncoding RNA SNHG6 promotes

proliferation and angiogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma cells through

sponging miR-101-3p and activation of E2F8. J Cancer. 11:3002–3012.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Abu-Alghayth MH, Khan FR, Belali TM,

Abalkhail A, Alshaghdali K, Nassar SA, Almoammar NE, Almasoudi HH,

Hessien KBG, Aldossari MS and Binshaya AS: The emerging role of

noncoding RNAs in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway in breast

cancer. Pathol Res Pract. 255(155180)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Golhani V, Ray SK and Mukherjee S: Role of

microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in regulating angiogenesis in

human breast cancer: A molecular medicine perspective. Curr Mol

Med. 22:882–893. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zheng M, Wu L, Xiao RC, Zhou Y, Cai J and

Shen SR: Integrated analysis of coexpression and a tumor-specific

ceRNA network revealed a potential prognostic biomarker in breast

cancer. Transl Cancer Res. 12:949–964. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Hussain MS, Moglad E, Afzal M, Gupta G,

Almalki WH, Kazmi I, Alzarea SI, Kukreti N, Gupta S, Kumar D, et

al: Non-coding RNA mediated regulation of PI3K/Akt pathway in

hepatocellular carcinoma: therapeutic perspectives. Pathol Res

Pract. 258(155303)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Liu J, Xiao S and Chen J: Development of

an inflammation-related lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA network based on

competing endogenous RNA in breast cancer at single-cell

resolution. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10(839876)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhan H, Tu S, Zhang F, Shao A and Lin J:

MicroRNAs and long non-coding RNAs in c-Met-regulated cancers.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 8(145)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Cui J, Chen M, Zhang L, Huang S, Xiao F

and Zou L: Circular RNAs: Biomarkers of cancer. Cancer Innov.

1:197–206. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Panoutsopoulou K, Avgeris M and Scorilas

A: miRNA and long non-coding RNA: molecular function and clinical

value in breast and ovarian cancers. Expert Rev Mol Diagn.

18:963–979. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Zhong X, Li J, Wu X, Wu X, Hu L, Ding B

and Qian L: Identification of N6-methyladenosine-related lncRNAs

for predicting overall survival and clustering of a potentially

novel molecular subtype of breast cancer. Front Oncol.

11(742944)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Helsmoortel H, Everaert C, Lumen N, Ost P

and Vandesompele J: Detecting long non-coding RNA biomarkers in

prostate cancer liquid biopsies: Hype or hope? Noncoding RNA Res.

3:64–74. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Islakoglu YO, Noyan S, Aydos A and

Dedeoglu BG: Meta-microRNA biomarker signatures to classify breast

cancer subtypes. OMICS. 22:709–716. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Lee BI, Oades K, Vo L, Lee J, Landers M,

Wang Y and Monforte J: NGS-based targeted RNA sequencing for

expression analysis of patients with triple-negative breast cancer

using a modulized, 96-gene biomarker panel. J Clin Oncol.

30(56)2012.

|

|

51

|

Narrandes S and Xu W: Gene expression

detection assay for cancer clinical use. J Cancer. 9:2249–2265.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Lange T, Gross T, Jeney Á, Scherzinger J,

Sinkala E, Niemöller C, Zimmermann S, Koltay P, Stetten F, Zengerle

R and Jeney C: Validation of scRNA-seq by scRT-ddPCR using the

example of ErbB2 in MCF7 cells. bioRxiv, 2022.

|

|

53

|

Poel D, Voortman J, Oord R, Gall H and

Verheul H: Standardization and optimization of circulating microRNA

serum profiling in patients with cancer. Cancer Res 75: doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.AM2015-3991,

2015.

|

|

54

|

Ratti M, Lampis A, Ghidini M, Salati M,

Mirchev MB, Valeri N and Hahne JC: MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and long

non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as new tools for cancer therapy: First

steps from bench to bedside. Target Oncol. 15:261–278.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Slaby O, Laga R and Sedlacek O:

Therapeutic targeting of non-coding RNAs in cancer. Biochem J.

474:4219–4251. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Haryana S: Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA)

and microRNA (miRNA) in cancer management. J Med Sci.

48(35)2016.

|

|

57

|

Gambari R, Brognara E, Spandidos D and

Fabbri E: Targeting oncomiRNAs and mimicking tumor suppressor

miRNAs: New trends in the development of miRNA therapeutic

strategies in oncology. Int J Oncol. 49:5–32. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Pierouli K, Papakonstantinou E,

Papageorgiou L, Diakou I, Mitsis T, Dragoumani K, Spandidos DA,

Bacopoulou F, Chrousos GP, Goulielmos G, et al: Long noncoding RNAs

and microRNAs as regulators of stress in cancer. Mol Med Rep.

26(361)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Agami R: Abstract CN01-03: Prospects for

miRNA- and lncRNA-based cancer therapeutics. Mol Cancer Ther.

12(CN01-03-CN01-03)2013.

|

|

60

|

Fu Z, Wang L, Li S, Chen F, Au-Yeung K and

Shi C: MicroRNA as an important target for anticancer drug

development. Front Pharmacol. 12(736323)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hong D, Kang Y, Borad M, Sachdev J, Ejadi

S, Lim H, Brenner A, Park K, Lee J, Kim T, et al: Phase 1 study of

MRX34, a liposomal miR-34a mimic, in patients with advanced solid

tumours. Br J Cancer. 122:1630–1637. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Varghese AM, Ang C, Dimaio CJ, Javle MM,

Gutierrez M, Yarom N, Stemmer SM, Golan T, Geva R, Semenisty V, et

al: A phase II study of siG12D-LODER in combination with

chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer

(PROTACT). J Clin Oncol. 38 (Suppl 15)(TPS4672)2020.

|

|

63

|

ClinicalTrials.gov: A phase 2 study of siG12D LODER

in combination with chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced

pancreatic cancer. Identifier: NCT01676259. Accessed Aug 21,

2025.

|

|

64

|

Tolcher AW, Papadopoulos KP, Patnaik A,

Rasco D, Martinez D, Wood D, Fielman B, Sharma MR, Janisch L, Brown

B, et al: Safety and activity of DCR-MYC, a first-in-class

Dicer-substrate siRNA targeting MYC, in a phase I study in patients

with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 33 (Suppl

15)(11006)2015.

|

|

65

|

ClinicalTrials.gov: Phase Ib/II, multicenter dose

escalation study of DCR-MYC in hepatocellular carcinoma.

Identifier: NCT02314052 (status history/results). Accessed Aug 21,

2025.

|

|

66

|

Bazhenova L, Mamdani H, Chiappori A, Spira

A, Iams W, Tolcher A, Barve M, Gabayan A, Vandross A, Cina C, et

al: First-in-human dose-expansion study of NBF-006, a novel

investigational siRNA targeting GSTP, in patients with KRAS-mutated

non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 84 (Suppl

7)(CT040)2024.

|

|

67

|

Cina C, Majeti B, O'Brien Z, Wang L,

Clamme JP, Adami R, Tsang KY, Harborth J, Ying W and Zabludoff S: A

novel lipid nanoparticle NBF-006 encapsulating glutathione

S-Transferase P. siRNA for the treatment of KRAS-driven non-small

cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 24:7–17. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Cantarella S, Di Nisio E, Carnevali D,

Dieci G and Montanini B: Interpreting and integrating big data in

non-coding RNA research. Emerg Top Life Sci. 3:343–355.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Veneziano D, Marceca GP, Di Bella S,

Nigita G, Distefano R and Croce CM: Investigating miRNA-lncRNA

interactions: Computational tools and resources. Methods Mol Biol.

1970:251–277. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Jiang J, Lyu P, Li J, Huang S, Blackshaw

S, Qian J and Wang J: IReNA: Integrated regulatory network analysis

of single-cell transcriptomes and chromatin accessibility profiles.

iScience. 25(105359)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Kumar N, Mishra B, Athar M and Mukhtar S:

Inference of gene regulatory network from single-cell

transcriptomic data using pySCENIC. Methods Mol Biol. 2328:171–182.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Nersisyan S, Gorbonos A, Makhonin A,

Zhiyanov A, Shkurnikov M and Tonevitsky A: isomiRTar: A

comprehensive portal of pan-cancer 5'-isomiR targeting. PeerJ.

10(e14205)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R and Dong Y: Lipid

nanoparticles for mRNA/RNA delivery: Challenges and opportunities.

Nat Rev Mater. 6:1078–1094. 2021.

|

|

74

|

Jayaraman M, Ansell SM, Mui BL, Tam YK,

Chen J, Du X, Butler D, Eltepu L, Matsuda S, Narayanannair JK, et

al: Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for in vivo

delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 51:8529–8533. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Tam YYC, Chen S and Cullis PR: Advances in

lipid nanoparticles for siRNA delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev.

65:331–339. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Springer AD and Dowdy SF: GalNAc-siRNA

conjugates: Leading the way for delivery to hepatocytes. Nucleic

Acid Ther. 28:109–118. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Debacker AJ, Voutila J, Catley M, Blakey D

and Habib N: Delivery of oligonucleotides to the liver with GalNAc.

Nucleic Acid Ther. 30:364–386. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

McNamara JO II, Andrechek ER, Wang Y,

Viles KD, Rempel RE, Gilboa E, Sullenger BA and Giangrande PH: Cell

type-specific delivery of siRNAs with aptamer-siRNA chimeras. Nat

Biotechnol. 24:1005–1015. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Karikó K, Buckstein M, Ni H and Weissman

D: Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: Impact of

nucleoside modifications. Immunity. 23:165–175. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Coch C, Lück C, Schwickart A, Putschli B,

Renn M, Höller T, Barchet W, Hartmann G and Schlee M: A human in

vitro whole-blood assay to predict therapeutic

oligonucleotide-induced cytokine release. PLoS One.

8(e71057)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Jackson AL, Burchard J, Schelter J, Chau

N, Cleary M, Lim L and Linsley P: Widespread siRNA off-target

transcript silencing mediated by seed region interactions. Nat

Biotechnol. 24:635–637. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A and Darnell RB:

Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature.

460:479–486. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid

M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M Jr, Jungkamp AC,

Munschauer M, et al: Transcriptome-wide identification of

RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell.

141:129–141. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Dai H, Jin QQ, Li L and Chen LN:

Reconstructing gene regulatory networks in single-cell

transcriptomic data analysis. Zool Res. 41:599–604. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Schmidt R, Steinhart Z, Layeghi M, Freimer

J, Bueno R, Nguyen V, Blaeschke F, Ye C and Marson A: CRISPR

activation and interference screens decode stimulation responses in

primary human T cells. Science. 375(eabj4008)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Pandey S, Agarwala P and Maiti S:

Targeting RNA G-quadruplexes for potential therapeutic

applications. Top Curr Chem (Cham). 377:177–206. 2017.

|

|

87

|

Roxo C, Zielińska K and Pasternak A:

Bispecific G-quadruplexes as inhibitors of cancer cells growth.

Biochimie. 214:91–100. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Chuya N and Hiroyuki S: G-quadruplex in

cancer biology and drug discovery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

533:762–773. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Zhang J, Zhang P, Wang L, Piao HL and Ma

L: Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR in carcinogenesis and metastasis.

Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 46:1–5. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Poliseno L, Salmena L, Zhang J, Carver B,