1. Introduction

The secretion associated Ras related GTPase 1B

(SAR1B) gene is a key regulator of coat protein complex II (COPII)

coat protein complex formation and plays an important role in

maintaining cellular homeostasis by mediating protein secretion,

regulating lipid metabolism, and influencing autophagosome

synthesis. It is established that SAR1B gene defects cause

chylomicron retention disease, a lipid metabolism disorder

(1). In recent years, research has

demonstrated that the SAR1B gene is involved in the regulation of

various biological behaviors of tumor cells, such as participating

in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) of tumor cells,

regulating membrane synthesis and energy metabolism by affecting

lipid metabolism, controlling the secretion of key proteins in the

signaling pathway of tumor cells to influence signaling, and

regulating the tumor development process by affecting the synthesis

of autophagosomes under stress. It has been found that the SAR1B

gene is abnormally expressed in numerous malignant tumors, such as

colorectal cancer (CRC) and lung cancer (LC), and has the potential

to be used as a prognostic marker. The functional basis of

mediating the formation of COPII envelope protein complexes can be

used as a target for novel drug research. However, the specific

mechanism underlying the role of the SAR1B gene in tumor cell

development, migration and invasion has not been systematically

elucidated. Further research is warranted to investigate the

clinical potential of the SAR1B gene and explore the possibility of

using this gene as a therapeutic target for malignant tumors.

2. Structure, origin and physiological

function of the SAR1B gene

Structure and origin of the SAR1B

gene

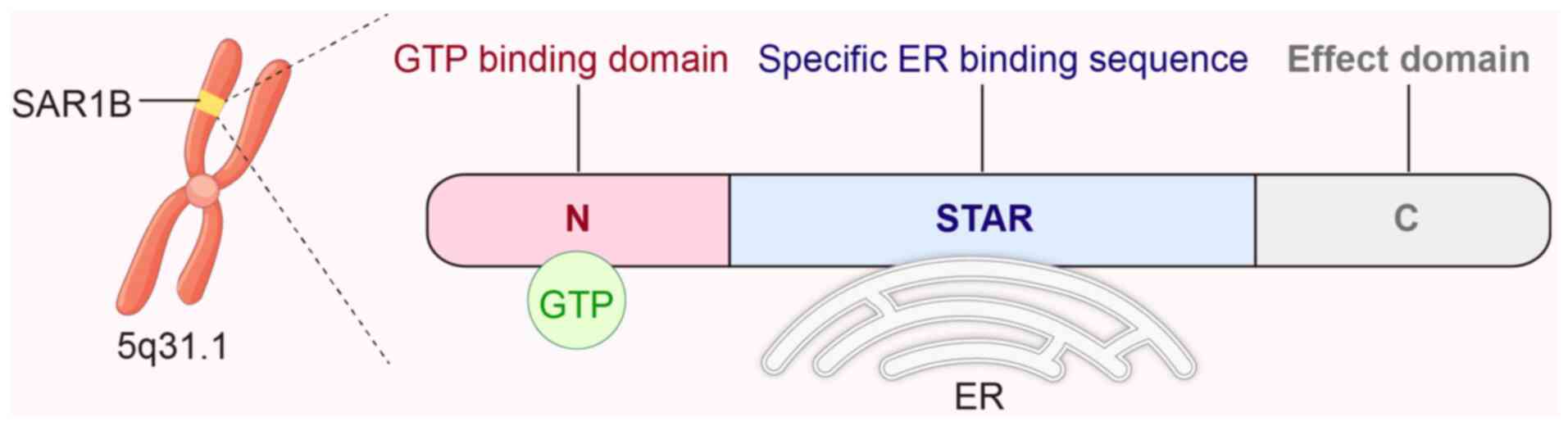

The human SAR1B gene is located on chromosome 5q31.1

and encodes a GTPase protein containing 198 amino acids, a core

component of the COPII complex. It is evolutionarily highly

conserved and widespread in eukaryotes. The SAR1B protein contains

a GTP-binding structural domain (N-terminal) and an effector

structural domain (C-terminal) that contains a unique Sar1-NH2

terminal activation recruitment (STAR) motif composed of nine amino

acids. This evolutionarily conserved cluster of bulky hydrophobic

amino acids facilitates membrane binding and contains specific

sequence information necessary for COPII complex formation

(2) (Fig. 1). SAR1B and its paralogous

homologue SAR1A are jointly involved in the formation of the COPII

complex. SAR1A and SAR1B share up to 89% amino acid sequence

identity and have a similar secondary structure of the N-terminal

amphiphilic α-helix (3). During

COPII vesicle outgrowth, they can compensate for each other's

functional defects.

SAR1B is a member of the ADP-ribosylation factor

(Arf) subfamily of the small GTPase family. The small GTPase

family, also known as the small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase)

superfamily, is a family of proteins that can act as signaling

commanders, play a regulatory role in a variety of physiological

functions of cells, and affect the development, invasion and

migration of tumor cells through various pathways. The rat sarcoma

virus (RAS) oncogene was discovered in 1980; this gene can

stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of cells in human

cancer cells and was classified as a small GTPase (4). Thereafter, the large family of small

G proteins was discovered through continuous and in-depth

exploration and research. According to their structure and

function, these proteins have been subdivided into five subfamilies

(that is, Ras, Rho, Rab, Arf/Sar and Ran) (5). The gene encoding the Ras superfamily

of small GTPases is one of the most frequently mutated or

dysregulated genes in human cancers.

Although these subfamilies have different

physiological functions, they have a common mechanism of action,

namely they can act as ‘molecular switches’. Under the binding

effect of the regulatory factors guanine nucleotide exchange factor

(GEF) and GTPase activating protein (GAP), they can realize the

cycle of activation and inactivation states through

phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycles, and transmit the upstream

information to the downstream effectors through conformational

changes (5). For example, members

of the Ras family can regulate cell proliferation-related pathways

through the activation of plasma membrane-localized GEFs, while

members of the Arf family rely on endoplasmic reticulum

(ER)-localized GEFs (for example, SEC12, an activator of SAR1) to

initiate vesicular transport programs. The mechanism by which SAR1B

of the Arf family initiates protein vesicular transport is

discussed below.

Physiological mechanisms of

SAR1B-mediated COPII complex formation

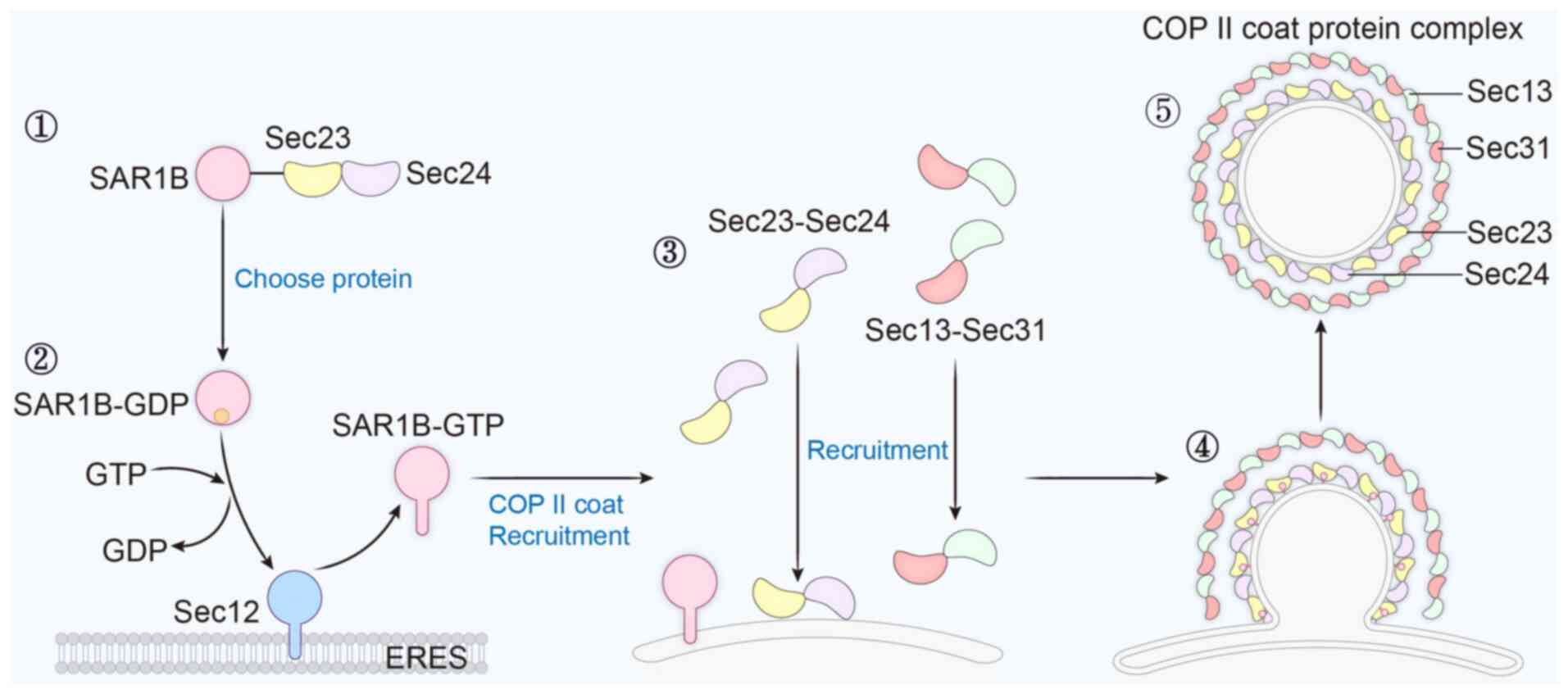

After synthesis, the protein undergoes preliminary

processing and modification in the rough ER and is correctly folded

and assembled to form a protein with a certain spatial structure.

Subsequently, this protein is transported to the Golgi apparatus

via vesicle transport at the exit site of the ER and then

transferred to other organelles or secreted out of the cell from

the Golgi apparatus. Whereas the process of transport from the ER

to the Golgi requires that proteins be concentrated and packaged

into vesicles, SAR1B can initiate vesicle assembly. The vesicles

that package cargo proteins are known as the COPII shell protein

complex and have the functions of selecting, binding, and

concentrating the transported cargo proteins. The COPII shell

protein complex consists of five core proteins (that is, SAR1B and

the shell proteins SEC23, SEC24, SEC13 and SEC31). Among them,

SAR1B is the most important component of the COPII shell protein

complex (6). Initially, the

selection of cargoes transported in the ER is performed by the

SAR1B-SEC23-SEC24 complex. Subsequently, SAR1B is recruited to the

ER exit site by SEC12, which is activated by SEC12 and binds to the

ER membrane to initiate COPII shell assembly. SEC12 is a unique

activator of SAR1B, an integral membrane glycoprotein localized to

the ER that serves as a GEF, and a fragment of which was previously

named as the transcription factor prolactin regulatory element

binding protein. It has been shown that knockdown of SEC12 using

small interfering RNA results in diminished SAR1B activation

signaling at the ER exit (7).

Activated SAR1B sequentially recruits the SEC23-SEC24 complex and

the SEC13-SEC31 complex to complete the assembly of the inner and

outer layers of the COPII coat, respectively (8). SEC23 and SEC31 acting as a GAP to

dephosphorylate SAR1B. After cargo recruitment and concentration in

the ER lumen mediated by SEC24, SAR1B recruits SEC13 and SEC31 to

form the outer coating. Continuous formation of the outer coating

leads to the deformation of the ER membrane, which is highly curved

and subsequently shrinks and breaks off at the neck, ultimately

forming the intact vesicle. Finally, the COPII shell protein

complex carries cargo proteins for transport to the Golgi apparatus

(Fig. 2). Although the process by

which SAR1B initiates the assembly of COPII vesicles is well

understood, the mechanism underlying its role in the process of

membrane outgrowth and rupture remains poorly understood and needs

to be explored (9).

This precise regulation guarantees the accurate

transport of proteins in normal physiological activities and plays

an important role in the transport of proteins and other nutrients

in tumor cells. SAR1B is also able to play a dual role in basal

metabolism and response to stress by receiving different signals

from the cell and regulating the formation of COPII vesicles.

3. SAR1B regulates lipid metabolism in

malignant tumor cells

SAR1B has a higher affinity for the shell protein

SEC23 than SAR1A, leading to its unique ability of lipoprotein

secretion (10). It was found that

SAR1B is typically able to produce larger vesicles than SAR1A and

highly associated with impaired lipid metabolism (3). Lipid metabolism is critical in cancer

cell proliferation, survival and other biochemical processes. Lipid

metabolism disorders have become a hallmark of malignant tumors.

When nutrients (for example, lipids, proteins and nucleic acids)

are enriched, the oncogenic signaling pathway directly enhances

nutrient acquisition and promotes tumor cell proliferation, which

is inextricably linked to the regulatory role of SAR1B in lipid

transport.

Experimental results have shown that SAR1B is

overexpressed in CRC cells. Knocking out SAR1B can inhibit the

proliferation of CRC cells and induce apoptosis in RKO cells. This

suggests that SAR1B may promote the proliferation of CRC cells and

has a certain tumor-inducing effect (11). This may be related to the fact that

SAR1B serves as a hub for lipid metabolism in tumor cells.

In addition, SAR1B can also affects lipid metabolism

in tumor cells by regulating the transport of lipoproteins. SAR1B

regulates lipoprotein delivery in concert with surfeit locus

protein 4 (SURF4), a cargo receptor that is localized in the ER

membrane. Several lipoproteins, including chymotrypsin, very

low-density lipoprotein, and its transformation product low-density

lipoprotein (LDL), transport insoluble lipids within the

apolipoprotein envelope. There is evidence that SURF4 is involved

in the transport of lipoproteins, and knockdown of SURF4 in

hepatocytes drastically reduces plasma total cholesterol and

triglyceride levels (12). LDL is

the main carrier of cholesterol, cholesterol is an important

structural component of cell membranes, malignant tumor cells

proliferate rapidly and require a large amount of cholesterol to

form new cell membranes, and the binding of LDL to its LDL receptor

can deliver cholesterol to tumor cells and provide raw materials

for cell membrane synthesis in rapidly proliferating tumor

cells.

Cholesterol plays a crucial role in maintaining the

integrity and function of cell membranes on the one hand. On the

other hand, when cholesterol is in excess, it can lead to

cytotoxicity. Cholesterol is an amphiphilic sterol molecule;

SREBF1/sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1

(SREBP-1) is a key lipogenic transcription factor and plays a

critical role in maintaining cholesterol homeostasis in tumor cells

(13). The activation of the

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway can induce the transcription of

SREBPs and promote cholesterol uptake and synthesis to meet the

needs of tumor cells (14). It has

been confirmed that the deficiency of SAR1B can lead to a decrease

in the level of SREBP-1, resulting in reduced lipogenesis (15). Therefore, SAR1B can indirectly

regulate cholesterol homeostasis in tumor cells and play different

roles at different stages of tumor progression.

The small intestine is an important site for

transporting dietary fat in the form of lipoproteins. The lipolytic

products generated by the digestion of food are absorbed by small

intestinal epithelial cells. Chylomicrons, triglyceride-rich

lipoproteins, and dietary lipid carriers produced by the processing

of enterocytes will transfer dietary fat into the bloodstream

through the lymphatic system for the body to utilize (15). Genetic defects in SAR1B will

inhibit the transport of chylomicrons within enterocytes from the

ER to the Golgi apparatus. As a result, the lipids and fat-soluble

vitamins absorbed in the form of chylomicrons cannot be released

into the bloodstream, leading to a large amount of lipid

accumulation in enterocytes. It has been shown that knocking out

SAR1B in the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2/15,

which secretes chylomicrons, disrupts lipid homeostasis and leads

to lipid accumulation (10). The

deficiency of SAR1B not only interferes with lipid homeostasis in

enterocytes, but lipid accumulation has also been observed in

SAR1B-deficient livers (12).

Cells with lipid metabolism disorders typically exhibit enhanced

fatty acid synthesis, increased lipid uptake, and inhibited

oxidation. This then gives rise to lipotoxicity, which causes

oxidative stress. Oxidative stress promotes DNA damage in cancer,

further leading to malignancy and carcinogenesis (14), and can trigger a series of

intracellular signaling cascades, exacerbating tumor progression.

Lipid accumulation can also enhance the downstream pro-cancer

signal transduction by forming lipid rafts to enrich growth factor

receptors (such as EGFR and HER2). It can be observed that SAR1B

has a certain anticancer effect in some cases, although the

specific mechanism remains to be explored.

SAR1B also regulates the formation of lipid

droplets. Lipid droplets are intracellular organelles that are

present in numerous types of cells and are generated after budding

from the ER via the COPII vesicle pathway. Lipids stored in lipid

droplets in tumor cells will provide energy support to tumor cells

and are involved in the regulation of cell membrane production and

signaling. In addition, lipid droplets can sequester

chemotherapeutic drugs, reducing the effective concentration of

drugs in tumor cells and making tumor cells resistant to

chemotherapeutic drugs. The core of lipid droplets consists of

triacylglycerol surrounded by phospholipid monolayers and surface

proteins such as perilipin 2 (PLIN2). It has been shown that SAR1B

mutations will result in reduced PLIN2 expression and can lead to

mis-localization of PLIN2, which affects the morphology and

integrity of lipid droplets and their ability to uptake and store

lipids (16).

4. SAR1B responds to stress and regulates

autophagy levels in cells

Unlike the physiological mechanism of SAR1B-mediated

COPII vesicle formation, SAR1B can also regulate the level of

cellular autophagy to maintain cellular homeostasis by forming the

precursor components of autophagosome membranes under stress.

Autophagy is a type of self-protection function during cellular

stress, which is like a ‘cleaner’ of the cell, capable of removing

damaged organelles (for example, mitochondria and ER), misfolded or

aggregated proteins, as well as invasive pathogens. In this way,

SAR1B can ensure the cell's stability in the presence of nutrients.

Consequently, it guarantees cell survival under unfavorable

conditions, such as nutrient deficiency and oxidative stress.

Moreover, autophagy plays a key role in the development of

organisms, immunity, aging, and the onset and progression of a

variety of diseases (for example, neurodegenerative diseases and

cancer) (17). The core of

autophagy is the formation of autophagosomes. Autophagosomes are

double-membrane vesicles produced during autophagy. They

encapsulate aged or damaged organelles, proteins and other

substances, and transport them to lysosomes for degradation. The

resulting macromolecules are then recycled and reused.

Autophagosome membranes are mainly obtained from the ER-Golgi

transport system, and membrane precursors of autophagosomes are

generated by membrane reorganization.

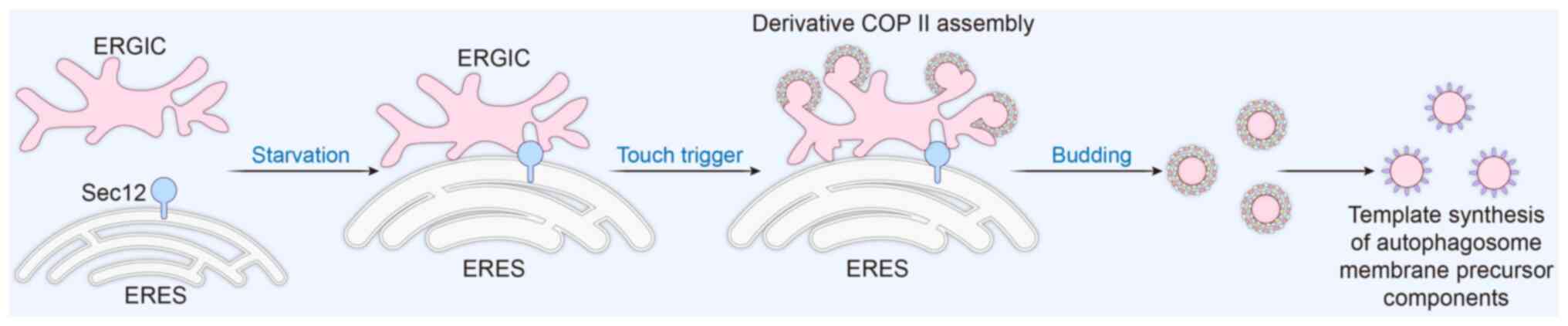

Under stress conditions such as starvation, the ER

will generate two important sites: ER-Golgi intermediate

compartment (ERGIC) and ER exit sites (ERES). Under normal

homeostasis, ERGIC and ERES accomplish vesicular transport of

proteins through SAR1-mediated generation of the COPII shell

protein complex. Sec12 is an activator of COPII vesicle formation.

In stress environments such as starvation, it can trigger the

formation of a special type of COPII vesicle, known as ERGIC-COPII

vesicles or derivative COPII vesicles. The formation and assembly

of derivative COPII vesicles are also regulated by SAR1B. A key

step in autophagosome biogenesis is the lipidation of

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) to generate

the autophagosome membrane, and these derivative vesicles will

serve as the membrane template for LC3 lipidation. The formation of

derivative COPII vesicles is triggered by membrane contact, ER can

form different membrane contacts with different organelles, such as

mitochondria, to realize intercellular information transfer

(18). Derived COPII vesicles are

localized in ERGIC, and SEC12 is localized in ERES.

Starvation-induced ERES enlarges and becomes tightly apposed to

ERGIC and undergoes a membrane contact, which is typically <2 nm

(19). Close membrane contact

enables Sec12 located at the ERES to trans-activate the assembly of

COPII on the ERGIC, triggers the generation of derivative COPII

vesicles here, and further regulates the formation of

autophagosomes (19).

Subsequently, derivative vesicles generated at the ERGIC site can

assume normal protein transport functions or continue to be used to

generate autophagosome membrane precursors. It has been

experimentally demonstrated that both the size and SEC12 of ERGIC

are affected by starvation (20)

(Fig. 3). Meanwhile, experiments

have indicated that the overexpression of the Sar1 mutant protein

leads to the inhibition of autophagosome formation, and knocking

down Sar1 can reduce autophagosome formation (21). In an experiment searching for drugs

against liver cancer drug resistance, knocking down SAR1B in liver

tumor-initiating stem-like cells inhibited the formation of the

autophagy-related gene LC3 II. When SAR1B was re-expressed, the

inhibition of LC3 II formation was relieved, which supports the

involvement of SAR1B in the formation of autophagosomes in tumor

cells (22). Other families of

small G proteins are also involved in this process. Following the

formation of membrane precursors, the lipid composition of

autophagosome membranes and the modification of membrane proteins

are regulated by Rab family small GTPases (23,24).

In addition, after their formation, intact autophagosomes approach

lysosomes through microtubule networks and fuse with them to form

autophagic lysosomes, which begin to degrade autophagosome contents

and remove damaged organelles and aged proteins. The stability of

the fusion process is regulated by Rho family small GTPases through

the regulation of the cytoskeleton and affects the transport of

autophagosomes within the cell, while Ras family small GTPases

promote the expression of autophagy-related genes (25-28).

In states such as viral infection or oxidation, the

intracellular protein structure is damaged. When a large number of

proteins are misfolded or unfolded, they accumulate in the ER and

cannot be transported out normally, causing a dysregulation of the

ER homeostasis, which is termed ER stress (29). The deletion of SAR1B expression

also induces an accumulation of proteins in the ER, which may

result in the saturation of the ER's folding capacity (30). At this point, the body triggers an

adaptive mechanism, that is, unfolded protein response, which

restores ER homeostasis and exerts cytoprotective effects by

attenuating protein translation, increasing the ER folding

capacity, and increasing the ER protein degradation capacity.

Unfolded protein response induces SAR1B expression, thus

accelerating protein transport. However, in case of excessive or

prolonged ER stress, autophagy is induced. Autophagy helps the

cells to remove unfolded proteins and damaged ER, thereby relieving

the ER stress, protecting the cell function, and preventing cell

death (29).

Autophagy has contradictory effects on tumor cells

and tumor progression. Autophagy can inhibit tumors in the early

stages of tumorigenesis and maintain the genomic stability of cells

by removing carcinogens and damaged components from the cells.

Moreover, in the late stage of tumor development, autophagy can

help tumor cells survive in harsh environments such as nutrient

deficiency and hypoxia, provide tumor cells with necessary

nutrients and energy, and promote tumor growth and metastasis

(31). The application of SAR1B to

regulate the autophagy level of tumor cells in different periods is

particularly important and deserves further investigation.

5. SAR1B gene is involved in tumor cell

signaling

SAR1B is involved in regulating the

tumor Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and affects tumor

migration

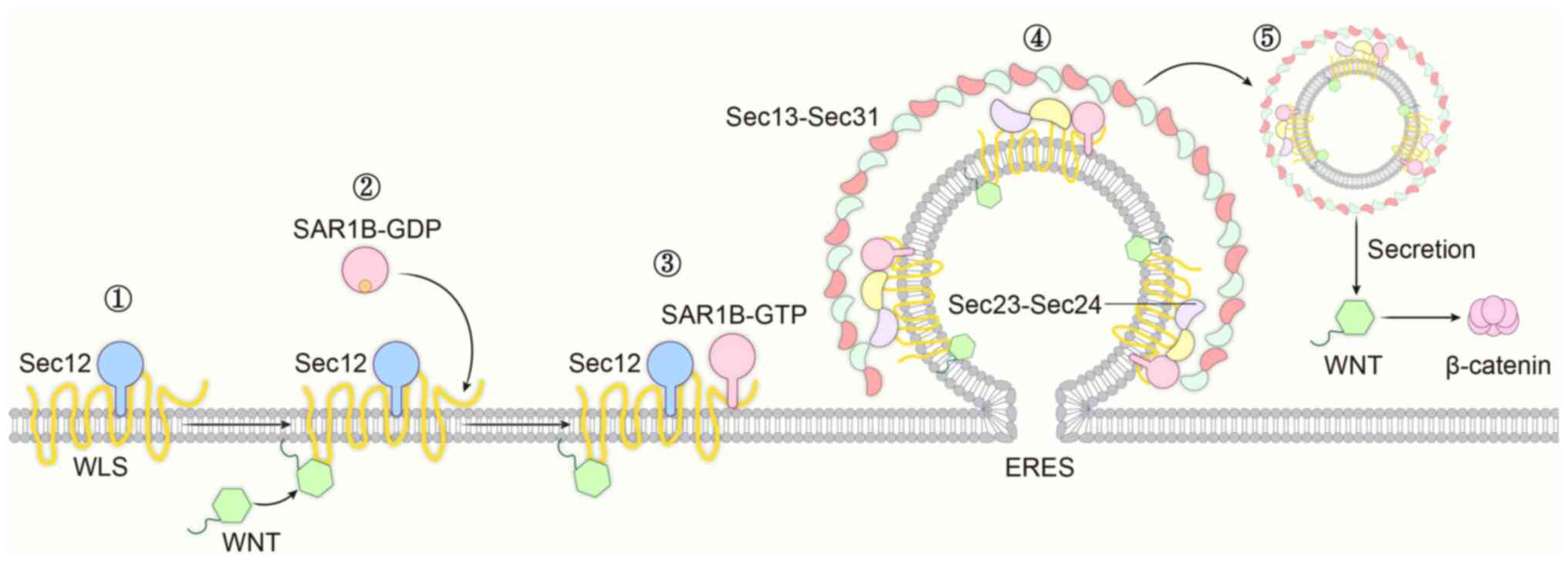

SAR1B is associated with the transduction of several

tumor cell signaling pathways. Among them, SAR1B is involved in Wnt

protein secretion of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Aberrant

activation of this signaling pathway is closely associated with the

development of numerous tumors, and 90% of CRCs show β-catenin

overexpression. Wnt is a secreted glycoprotein that is transported

extracellularly via COPII vesicles to play its role, and it is

essential for embryonic development and morphogenesis of adult

tissues (32). Wnt is secreted

into vesicles to control the output of functional ligands through

the ER mechanism, and Wntless is an important intermediate in this

pathway and a key regulator of Wnt protein secretion; its aberrant

expression level affects Wnt signaling. Wnt ligand secretion

mediator (Wls) enters the ER and binds to SEC12 and SAR1B, thereby

synergistically initiating the assembly of the COPII complex. Wls

is also able to bind to Wnt, facilitating its own interaction with

SEC12 and SAR1B in the ER, while regulating the movement of mature

Wnt vesicles out of the ER to the cell surface to perform their

functions. Although the underlying mechanism remains unclear,

Wnt-Wls binding in the ER may affect Wls-SEC12 binding through a

change in Wls conformation that stabilizes Wls-SEC12 binding or

exposes more SEC12 binding sites (33). When the Wnt molecule is defective

in palmitoylation, this process is compromised, and the output of

functional ligands is limited, potentially leading to the

development of certain diseases (33). Abnormalities of SAR1B in this

process lead to impaired Wnt secretion, while the downstream

β-catenin continues to accumulate and activate downstream target

genes. As a result, the cells gain the ability to proliferate

indefinitely, which is also an important basis for tumorigenesis

(Fig. 4).

The Arf subfamily proteins to which SAR1B belongs,

as well as their GEF and GAP, are aberrantly expressed in different

cancer cell types and human cancers through their involvement in

regulating actin remodeling. In sequencing data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas, the most common Arf genetic alterations are gene

amplification in prostate, breast, squamous lung, esophageal and

ovarian cancers, as well as invasive metastatic potential in

glioblastomas, uveal melanomas, breast, colon, prostate and

laryngeal squamous cell cancers, among others. Deletions of the Arf

GTPase genome in cancer also occur, albeit more rarely (34).

SAR1B and the other members of the Arf subfamily are

also capable of influencing the migration process of tumor cells

through EMT. β-catenin is a key regulator of EMT, a biological

process that causes epithelial cells to lose polarity and

intercellular junctions and acquire mesenchymal cell properties. It

confers the ability to metastasize and invade, and plays an

important role in embryonic development, tissue repair and tumor

metastasis. Most β-catenin is located on the cell membrane of

epithelial cells. Under normal physiological conditions,

intracellular β-catenin is at low levels and binds to E-cadherin

(CDH1) to form a complex that anchors it to the actin cytoskeleton,

enhancing intercellular adhesion and maintaining the integrity and

stability of epithelial tissue. Once this binding is disrupted,

intercellular adhesion is weakened, the polarity and organization

of epithelial cells are affected, and cells are more likely to

detach from epithelial tissues, which is important in the process

of tumor cell invasion and metastasis. In a variety of tumors, such

as breast, colorectal and gastric cancers, the reduced expression

of CDH1 is accompanied by abnormal activation and nuclear

accumulation of β-catenin, which is closely related to tumor

aggressiveness and poor prognosis (35). Experiments have shown that

knockdown of SAR1B in CRC cells enhances the migration and invasion

abilities of CRC cells and simultaneously leads to a significant

reduction in the levels of the epithelial marker CDH1 and an

increase in the mRNA expression of the mesenchymal marker vimentin.

These findings suggested that the cells shifted towards a more

mesenchymal phenotype. Therefore, SAR1B may inhibit the motility

and metastasis of CRC cells by regulating EMT. Meanwhile, the

deficiency of SAR1B can also stimulate EMT and promote cell

motility and Transwell invasion (36). Lower levels of SAR1B mRNA

expression were significantly associated with reduced survival and

advanced disease stage in patients with CRC, patients with high

expression of SAR1B have an improved prognosis, revealing a

potential role for SAR1B in inhibiting CRC progression. SAR1B may

serve as a prognostic biomarker and a potential inhibitor of

metastasis in CRC tumor cells (36). Moreover, experiments have shown

that SAR1A expression levels are elevated in patients with

osteosarcoma, and SAR1A levels increase osteosarcoma lung

metastasis. Furthermore, knocking down SAR1A can reduce the

formation of platelet-like pseudopods in osteosarcoma cells,

inhibit the EMT of osteosarcoma cells, and reduce the ability of

osteosarcoma cells to invade and migrate (37). The function of SAR1A as a

paralogous homolog of SAR1B, to some extent, also reveals the

potential function of SAR1B.

As aforementioned, SAR1B can either promote or

inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells by regulating lipid

metabolism. Meanwhile, experiments have confirmed that SAR1B can

promote the proliferation and inhibit the apoptosis of CRC cells.

Additionally, SAR1B can suppress the migration and invasion of CRC

by regulating EMT. It was found that SAR1B plays different roles at

different stages of CRC development, bringing either positive or

negative impacts on tumor cell activities. It is worth noting that

numerous genes play different regulatory roles in the biological

behavior of tumor cells within the same type of tumor. For example,

Patched 1, a gene encoding a transmembrane protein, inhibits the

proliferation of non-small cell LC (NSCLC) through its encoded

protein. However, it also promotes the migration, invasion and

adhesion of NSCLC cells through its 3'-untranslated region

(38). A similar situation exists

for the SAR1B gene in CRC cells. This interesting phenomenon is

worthy of in-depth consideration and exploration.

SAR1B is involved in the regulation of

the mTOR pathway. SAR1B as a leucine sensor for the mTOR signaling

pathway

SAR1B is involved in the mTOR pathway through two

pathways. The mTOR pathway is a key signaling pathway in cells.

mTOR is a serine/threonine protein kinase that, together with a

variety of regulatory-related proteins, form the mTOR complex 1

(mTORC1), which senses intracellular nutrients (for example, amino

acids and glucose), energy levels, growth factors, and stress

signals and promotes cell proliferation by regulating various

aspects of protein synthesis, ribosome biogenesis and cell cycle

progression (39). The small

GTPase SAR1B plays a key role in the activation, signaling and

functional regulation of the mTOR pathway.

Normally, mTOR helps cells proliferate, as well as

and maintain their function and structure. However, abnormally high

activity of mTOR may lead to excessive cell proliferation, which in

turn may lead to the development of malignant solid tumors (for

example, breast cancer, LC and ovarian cancer) and hematologic

malignancies (for example, leukemia and lymphoma) (40). In addition, abnormalities of mTOR

have been associated with the development of certain neurological

diseases, such as cognitive impairment and Parkinson's disease

(41). Sustained activation of the

mTOR signaling pathway promotes cell proliferation and survival and

inhibits autophagy. In neurological diseases, it leads to abnormal

changes in neurons, interferes with the normal transmission and

processing of neural signals, and thus affects the brain's

information integration and cognitive functions. For example, it

may cause increased neuronal excitability or excessive synaptic

growth. Alternatively, it may result in the failure to clear

unhelpful proteins in the brain through autophagy, leading to their

deposition in the brain and damage to neuronal functions. As an

illustration, the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) in the brain to form

amyloid plaques causes Alzheimer's disease (42). In tumors, the continuous activation

of mTOR is manifested as promoting the proliferation and metastasis

of tumor cells. For instance, the abnormal activation of the

PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway can promote tumor cell

proliferation, survival, metabolic reprogramming and angiogenesis

(43).

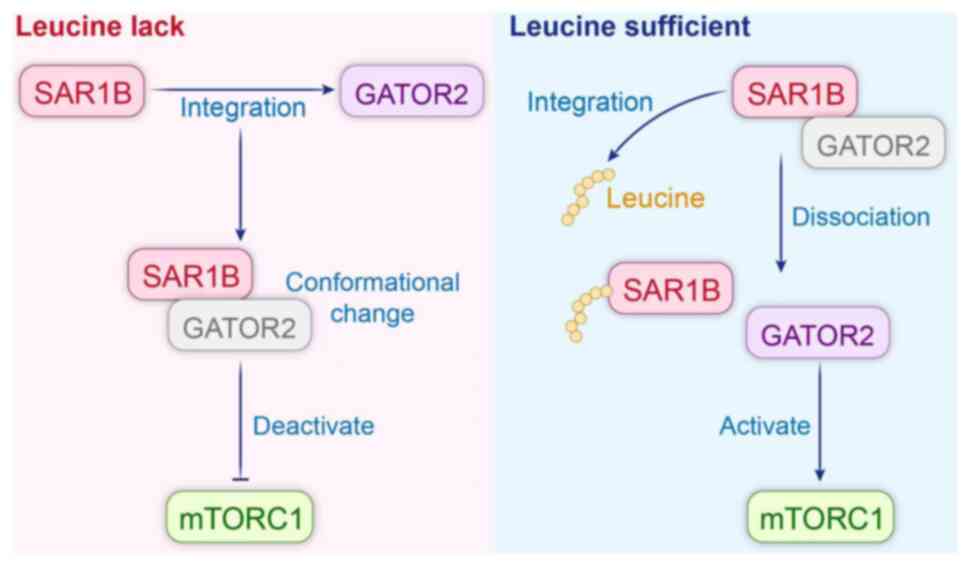

Leucine can act as an upstream regulator of the mTOR

pathway, entering the cell via amino acid transporter carriers on

the cell membrane and regulating the mTORC1 signaling pathway and

subsequent protein synthesis processes (44). SAR1B can act as a leucine sensor to

regulate mTORC1 signaling based on intracellular leucine levels.

GAP activity towards Rags 2 (GATOR2) is an activator of mTORC1;

SAR1B senses the intracellular leucine level through GATOR2 to

regulate mTORC1 signaling. In the absence of leucine, SAR1B binds

to GATOR2 and undergoes a conformational change, losing its

activating function for mTORC1 and, thus, inhibiting mTORC1. Under

leucine-sufficient conditions, SAR1B binds to leucine, undergoes a

conformational change, and dissociates from GATOR2, which acts to

activate mTORC1. Binding status does not affect their function in

mTORC1 regulation (Fig. 5)

(45). Knockdown of SAR1B renders

mTORC1 insensitive to amino acid depletion and specifically affects

the regulation of mTORC1 by leucine, without influencing other

amino acids. Re-expression of SAR1B can restore the sensitivity of

mTORC1 to leucine. The SAR1B mutant fails to bind to GATOR2 and

loses its inhibitory effect on mTORC1 under leucine-deficient

conditions. Therefore, it can be observed that SAR1B is essential

for the inhibition of mTORC1 under leucine-deficient conditions,

and the leucine-sensitive interaction between SAR1B and GATOR2 is

crucial for the regulatory effect of SAR1B on mTORC1(45).

Deficiency of the small GTPase SAR1B is associated

with lung carcinogenesis. In a mouse lung in situ xenograft

tumor model, deficiency of SAR1B and its homologue SAR1A eliminated

leucine sensitivity and failed to inhibit mTORC1 and significantly

promoted the mTORC1-dependent tumor growth. Immunohistochemical

staining revealed higher levels of the anabolic marker pS6 and the

proliferation marker Ki-67 and lower levels of the catabolic marker

light chain 3B in SAR1A- and SAR1B-deficient tumors. Silencing of

SAR1A and SAR1B in cells resulted in sustained activation of

mTORC1, which in turn led to tumorigenesis. Bioinformatics analysis

showed that SAR1B is frequently absent in human lung squamous cell

carcinoma and lung adenocarcinoma, and that patients with cancer

with lower levels of SAR1B expression have a poorer prognosis.

Therefore, SAR1B is most likely a tumor suppressor in LC (45). The mechanism of cancer inhibition

may be related to the modulation of leucine levels by SAR1B, which

affects the mTOR signaling pathway. SAR1B can be used as a

prognostic marker for LC, and compounds selectively targeting

SAR1B-dependent mTORC1 signaling may have potential for use in the

treatment of LC.

SAR1B regulates the formation of autophagosomal

membrane precursors associated with the mTOR pathway. In

addition to the core molecular mechanisms involved in the formation

of autophagosomes and autophagosomal membranes, the complex

signaling cascades that control autophagy are also particularly

important. Among them, the mTOR pathway is the core but not the

only one. mTORC1 regulates anabolism and catabolism to meet the

needs of cell proliferation. In proliferating cells, highly active

mTORC1 promotes the synthesis of biomolecules while inhibiting

autophagy. When mTORC1 is activated, it can phosphorylate and

inhibit autophagy-associated proteins, thereby inhibiting the

formation of autophagosomes and the autophagic process involving

the small GTPase SAR1B. By contrast, when the activity of mTORC1 is

inhibited under nutrient-deficient or stress conditions, the

autophagic process is activated, and cells can degrade and recycle

intracellular proteins and organelles through the formation of

autophagosomes to maintain cell survival and energy (46).

Dysregulation of mTORC1 is associated with

autophagy-deficient diseases. Autophagy requires the involvement of

COPII-derived vesicle transport, and vesicle generation is

regulated by SAR1B. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin can treat cancer

by upregulating autophagy levels. Drugs have been successfully

developed based on the GTP-binding ability of SAR1 and its ability

to mediate vesicle formation to regulate autophagy levels.

CD133+ liver tumor-initiating stem cell-like cells

isolated from mouse and human liver tumors drive early tumor

initiation and recurrence and are chemo-resistant to mTOR

inhibitors, which may lead to drug-resistant epilepsy and

hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. The chemo-sensitizing drug

baicalein (BC), which was developed based on the resistance of

hepatocellular carcinoma cells to mTOR inhibitors, can block mTOR

inhibitor-induced autophagy through competitive inhibition of the

GTP-binding ability of SAR1B GTPase, and thus has a

chemo-sensitizing effect. BC binds and inhibits small GTPases

involved in vesicle transport, and the binding of SAR1B to GTP is

blocked. Without the binding of SAR1B to GTP, vesicles cannot be

generated, the autophagosome membrane cannot be synthesized

normally, and autophagosome generation is reduced, thus inhibiting

the autophagy process. BC-treated tumor tissues show a significant

reduction of active SAR1B. Nanobead pull-down and mass

spectrometry, biochemical binding assay and three-dimensional

computational simulation, as well as activity analysis of BC

binding site showed that the main binding site of BC is the NH

2-terminal motif of SAR1, which is responsible for the activation

of SAR1 as well as involved in its interactions with GEF SEC12,

including GEF-binding and GAP-binding. The BC-mediated

SAR1B-dependent autophagy inhibition was attributed to its

chemo-sensitizing effect; inhibition is the basis of its

chemo-sensitizing effect. Therefore, SAR1B could be a novel target

for anticancer effects in liver tumor-initiating stem cell-like

cells and HCC cells that are resistant to mTORC1 inhibition

(22).

6. Discussion and future perspectives

As a core regulator of COPII vesicle trafficking,

SAR1B plays a role in tumor cell genesis, development,

proliferation, migration, substance metabolism, autophagy level,

signal transduction, and therapeutic resistance by mediating

protein secretion. SAR1B has the potential to be used as a

prognostic marker in lung and CRCs, and it has become a therapeutic

target for drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. SAR1B has

been shown to promote cell proliferation and inhibit tumor cell

metastasis in CRC cells, maintain cellular homeostasis by

regulating autophagy and removing intracellular carcinogens under

normal cellular stress, and help tumor cells regulate autophagy to

ensure their survival under nutrient-deficient conditions and

provide energy support to tumor cells by affecting their lipid

metabolism. Therefore, SAR1B has opposite functions in various

biological behaviors of malignant tumors. Of course, there are

still some thorny issues to be resolved. The mechanism by which

SAR1B promotes the proliferation of tumor cells in CRC, the

mechanism through which SAR1B inhibits the proliferation of LC

cells, the reason why it has completely opposite effects in

different types of tumors, whether SAR1B inhibits mTORC1 and

suppresses cancer proliferation regardless of the presence of

leucine, and if the effect of SAR1B on the mTOR pathway can be

observed in tumor types other than LC, remain unexplored. The

application of the two sides of SAR1B, rational utilization of its

cancer inhibitory function, and identification of therapeutic

targets against its cancer-promoting mechanism have become major

challenges in this field. In addition, whether SAR1B also mediates

the transport of some proteins that are highly relevant to various

biological behaviors of tumor cells remains unknown. Thus, further

investigation is warranted to address these challenges.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81372931 and 82003238) and

Bethune's Advanced Medical Research Fund in China (grant no.

2023-YJ-152-J-005).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

HL was responsible for establishing the framework of

the manuscript. QY undertook the task of literature retrieval,

composed the manuscript, and crafted the accompanying

illustrations. GH, CL and ZL offered professional guidance and were

actively involved in the meticulous revision and refinement of the

article. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Shoulders CC, Stephens DJ and Jones B: The

intracellular transport of chylomicrons requires the small GTPase,

Sar1b. Curr Opin Lipidol. 15:191–197. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Huang M, Weissman JT, Beraud-Dufour S,

Luan P, Wang C, Chen W, Aridor M, Wilson IA and Balch WE: Crystal

structure of Sar1-GDP at 1.7 A resolution and the role of the NH2

terminus in ER export. J Cell Biol. 155:937–948. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Loftus AF, Hsieh VL and Parthasarathy R:

Modulation of membrane rigidity by the human vesicle trafficking

proteins Sar1A and Sar1B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 426:585–589.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Reiner DJ and Lundquist EA: Small GTPases.

WormBook. 2018:1–65. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Takai Y, Sasaki T and Matozaki T: Small

GTP-binding proteins. Physiol Rev. 81:153–208. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Melville D, Gorur A and Schekman R:

Fatty-acid binding protein 5 modulates the SAR1 GTPase cycle and

enhances budding of large COPII cargoes. Mol Biol Cell. 30:387–399.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Maeda M, Arakawa M, Komatsu Y and Saito K:

Small GTPase ActIvitY ANalyzing (SAIYAN) system: A method to detect

GTPase activation in living cells. J Cell Biol.

223(e202403179)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Van der Verren SE and Zanetti G: The small

GTPase Sar1, control centre of COPII trafficking. FEBS Lett.

597:865–882. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tang VT, Xiang J, Chen Z, McCormick J,

Abbineni PS, Chen XW, Hoenerhoff M, Emmer BT, Khoriaty R, Lin JD

and Ginsburg D: Functional overlap between the mammalian Sar1a and

Sar1b paralogs in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

121(e2322164121)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Melville DB, Studer S and Schekman R:

Small sequence variations between two mammalian paralogs of the

small GTPase SAR1 underlie functional differences in coat protein

complex II assembly. J Biol Chem. 295:8401–8412. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lu Y, Zhou SK, Chen R, Jiang LX, Yang LL

and Bi TN: Knockdown of SAR1B suppresses proliferation and induces

apoptosis of RKO colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Lett.

20(186)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wang X, Wang H, Xu B, Huang D, Nie C, Pu

L, Zajac GJM, Yan H, Zhao J, Shi F, et al: Receptor-mediated ER

export of lipoproteins controls lipid homeostasis in mice and

humans. Cell Metab. 33:350–366.e7. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Geng F and Guo D: SREBF1/SREBP-1

concurrently regulates lipid synthesis and lipophagy to maintain

lipid homeostasis and tumor growth. Autophagy. 20:1183–1185.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Deng CF, Zhu N, Zhao TJ, Li HF, Gu J, Liao

DF and Qin L: Involvement of LDL and ox-LDL in cancer development

and its therapeutical potential. Front Oncol.

12(803473)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sané A, Ahmarani L, Delvin E, Auclair N,

Spahis S and Levy E: SAR1B GTPase is necessary to protect

intestinal cells from disorders of lipid homeostasis, oxidative

stress, and inflammation. J Lipid Res. 60:1755–1764.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Makiyama T, Obama T, Watanabe Y and Itabe

H: Sar1 affects the localization of perilipin 2 to lipid droplets.

Int J Mol Sci. 23(6366)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yang Z and Klionsky DJ: Mammalian

autophagy: Core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr

Opin Cell Biol. 22:124–131. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li S, Yan R, Xu J, Zhao S, Ma X, Sun Q,

Zhang M, Li Y, Liu JG, Chen L, et al: A new type of ERGIC-ERES

membrane contact mediated by TMED9 and SEC12 is required for

autophagosome biogenesis. Cell Res. 32:119–138. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li S, Zhang M and Ge L: A new type of

membrane contact in the ER-Golgi system regulates autophagosome

biogenesis. Autophagy. 17:4499–4501. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ge L, Zhang M, Kenny SJ, Liu D, Maeda M,

Saito K, Mathur A, Xu K and Schekman R: Remodeling of ER-exit sites

initiates a membrane supply pathway for autophagosome biogenesis.

EMBO Rep. 18:1586–1603. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zoppino FC, Militello RD, Slavin I,

Alvarez C and Colombo MI: Autophagosome formation depends on the

small GTPase Rab1 and functional ER exit sites. Traffic.

11:1246–1261. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Wu R, Murali R, Kabe Y, French SW, Chiang

YM, Liu S, Sher L, Wang CC, Louie S and Tsukamoto H: Baicalein

targets GTPase-mediated autophagy to eliminate liver

tumor-initiating stem cell-like cells resistant to mTORC1

inhibition. Hepatology. 68:1726–1740. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Morgan NE, Cutrona MB and Simpson JC:

Multitasking Rab proteins in autophagy and membrane trafficking: A

focus on Rab33b. Int J Mol Sci. 20(3916)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yu L, Chen Y and Tooze SA: Autophagy

pathway: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Autophagy. 14:207–215.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Till A, Saito R, Merkurjev D, Liu JJ, Syed

GH, Kolnik M, Siddiqui A, Glas M, Scheffler B, Ideker T, et al:

Evolutionary trends and functional anatomy of the human expanded

autophagy network. Autophagy. 11:1652–1667. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Zhang Y and Li G: A tumor suppressor DLC1:

The functions and signal pathways. J Cell Physiol. 235:4999–5007.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cao W, Li J, Yang K and Cao D: An overview

of autophagy: Mechanism, regulation and research progress. Bull

Cancer. 108:304–322. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang X, Cheng Q, Yin H and Yang G:

Regulation of autophagy and EMT by the interplay between p53 and

RAS during cancer progression (Review). Int J Oncol. 51:18–24.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Qi Z and Chen L: Endoplasmic reticulum

stress and autophagy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1206:167–177.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Caruso ME, Jenna S, Bouchecareilh M,

Baillie DL, Boismenu D, Halawani D, Latterich M and Chevet E:

GTPase-mediated regulation of the unfolded protein response in

Caenorhabditis elegans is dependent on the AAA+ ATPase CDC-48. Mol

Cell Biol. 28:4261–4274. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Schatoff EM, Leach BI and Dow LE: Wnt

signaling and colorectal cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep.

13:101–110. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Sun J, Yu S, Zhang X, Capac C, Aligbe O,

Daudelin T, Bonder EM and Gao N: A Wntless-SEC12 complex on the ER

membrane regulates early Wnt secretory vesicle assembly and mature

ligand export. J Cell Sci. 130:2159–2171. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sztul E, Chen PW, Casanova JE, Cherfils J,

Dacks JB, Lambright DG, Lee FS, Randazzo PA, Santy LC, Schürmann A,

et al: ARF GTPases and their GEFs and GAPs: Concepts and

challenges. Mol Biol Cell. 30:1249–1271. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sun L, Xing J, Zhou X, Song X and Gao S:

Wnt/β-catenin signalling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and

crosslink signalling in colorectal cancer cells. Biomed

Pharmacother. 175(116685)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Huang M and Wang Y: Targeted quantitative

proteomic approach for probing altered protein expression of small

GTPases associated with colorectal cancer metastasis. Anal Chem.

91:6233–6241. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhan F, Deng Q, Chen Z, Xie C, Xiang S,

Qiu S, Tian L, Wu C, Ou Y, Chen J and Xu L: SAR1A regulates the

RhoA/YAP and autophagy signaling pathways to influence osteosarcoma

invasion and metastasis. Cancer Sci. 113:4104–4119. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wan X, Kong Z, Chu K, Yi C, Hu J, Qin R,

Zhao C, Fu F, Wu H, Li Y and Huang Y: Co-expression analysis

revealed PTCH1-3'UTR promoted cell migration and invasion by

activating miR-101-3p/SLC39A6 axis in non-small cell lung cancer:

Implicating the novel function of PTCH1. Oncotarget. 9:4798–4813.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Mossmann D, Park S and Hall MN: mTOR

signalling and cellular metabolism are mutual determinants in

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:744–757. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Fu W and Wu G: Targeting mTOR for

anti-aging and anti-cancer therapy. Molecules.

28(3157)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhu Z, Yang C, Iyaswamy A, Krishnamoorthi

S, Sreenivasmurthy SG, Liu J, Wang Z, Tong BC, Song J, Lu J, et al:

Balancing mTOR signaling and autophagy in the treatment of

Parkinson's disease. Int J Mol Sci. 20(728)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Davoody S, Asgari Taei A, Khodabakhsh P

and Dargahi L: mTOR signaling and Alzheimer's disease: What we know

and where we are? CNS Neurosci Ther. 30(e14463)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Mafi S, Mansoori B, Taeb S, Sadeghi H,

Abbasi R, Cho WC and Rostamzadeh D: mTOR-mediated regulation of

immune responses in cancer and tumor microenvironment. Front

Immunol. 12(774103)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Ananieva EA, Powell JD and Hutson SM:

Leucine metabolism in T cell activation: mTOR signaling and beyond.

Adv Nutr. 7:798S–805S. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Chen J, Ou Y, Luo R, Wang J, Wang D, Guan

J, Li Y, Xia P, Chen PR and Liu Y: SAR1B senses leucine levels to

regulate mTORC1 signalling. Nature. 596:281–284. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Senapati PK, Mahapatra KK, Singh A and

Bhutia SK: mTOR inhibitors in targeting autophagy and

autophagy-associated signaling for cancer cell death and therapy.

Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1880(189342)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|