Introduction

Gliomas are among the most common and aggressive

primary brain tumors, with glioblastoma (GBM) being the most

malignant subtype (1). Despite

advancements in surgical and therapeutic interventions, GBM

prognosis remains poor, with a median survival of ~15 months

(2). Low-grade gliomas (LGGs)

progress more slowly but often transforme into higher-grade tumors.

The heterogeneity and molecular complexity of gliomas pose

significant challenges to effective treatment and prognosis

(3,4).

Aging is a well-recognized risk factor for numerous

cancers, including gliomas. Aging induces cellular and molecular

changes that create a favorable environment for tumor development

and progression (5). One of the

most critical changes is genomic instability, accompanied by

significant epigenetic alterations, such as aberrant DNA

methylation and histone modifications, which dysregulate gene

expression and promote malignancy (6,7).

The tumor microenvironment (TME) also undergoes

remodeling with aging, involving changes in the extracellular

matrix (ECM), blood vessels and immune cell infiltration, which

collectively enhance tumor growth and metastasis (8). In gliomas, these aging-related

changes are particularly relevant. Dysregulation of pathways such

as the p53 tumor suppressor and PI3K/AKT/mTOR, crucial for cell

cycle regulation and survival, is common in gliomas and is

exacerbated by aging (9).

Moreover, mutations in IDH1 and IDH2, more prevalent in younger

patients and associated with improved outcomes, highlight the

complex interplay between aging and glioma biology (3,10).

The specific role of aging-related genes in glioma

prognosis and their utility in prognostic models remain

underexplored. In the present study, an aging-related risk score

model that effectively predicts glioma patient prognosis,

immunotherapy efficacy, and chemotherapy sensitivity, was

developed. However, as the current findings are based on

bioinformatics analysis, further experimental validation is

required to confirm the model's clinical relevance.

Materials and methods

The present study utilized data from The Cancer

Genome Atlas (TCGA) (TCGA-GBM and TCGA-LGG; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) and the Chinese Glioma

Genome Atlas (CGGA) (CGGA-mRNAseq_693; http://www.cgga.org.cn/) to analyze gene expression

differences between LGGs and GBM. Gene expression profiles and

corresponding clinical information were downloaded from these

databases. The data acquisition and preprocessing steps are as

follows:

Data acquisition and

preprocessing

Glioma RNA sequencing and clinical data were

obtained from the TCGA website (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov). Glioma expression data

and clinical information were downloaded from the CGGA website

(http://www.cgga.org.cn/). Samples with missing or

incomplete clinical information were excluded. The gene expression

data were normalized and background-corrected via the ‘limma’ (v

3.58.1) package in R.

Differential gene expression

analysis

To identify genes differentially expressed between

LGG and GBM, TCGA and CGGA expression data were normalized and

log2-transformed using the ‘limma’ package in R. |LogFC|>1 was

selected and P<0.05 was adjusted to capture biologically

meaningful differences while minimizing false positives, consistent

with widely accepted thresholds in transcriptome studies.

Senescence-related gene screening

A total of 279 senescence-related genes were

downloaded from the Human Aging Genomic Resources (HAGR) database

and used Venn diagrams to identify the overlap between these

senescence-related genes and the differentially expressed genes

(DEGs) from the TCGA and CGGA datasets.

Risk score model construction and

validation

From the DEGs, 29 senescence-related genes were

selected to construct a risk score model. Univariate Cox regression

analysis (P<0.001) identified significant genes, followed by

LASSO regression to narrow the selection to 12 genes. Multivariate

Cox regression finalized 8 genes for the model. The risk score

formula was defined as: risk score=Σ (gene expression x gene

coefficient), stratifying patients into high-risk and low-risk

groups.

The model's performance was assessed using

Kaplan-Meier (K-M) survival and receiver operating characteristic

(ROC) curve analyses in TCGA and CGGA datasets. R packages

‘survival’ (v3.2.1) and ‘survminer’ (v3.3.3) were utilized, with

P<0.05 considered significant. Area Under Curve (AUC) values

>0.9 indicated excellent performance, >0.8 favorable

performance, and >0.7 useful discrimination.

Construction and validation of the

nomogram

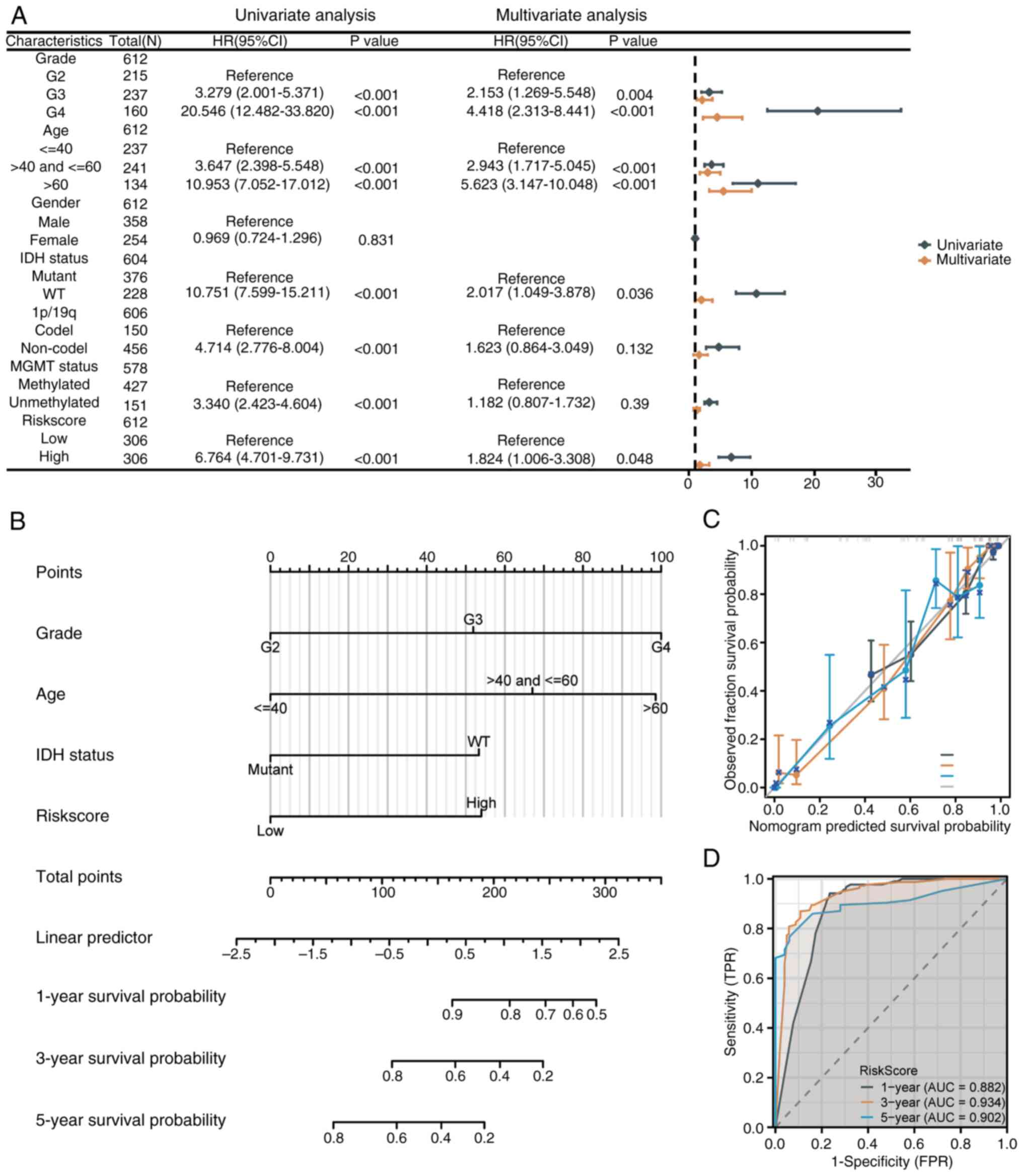

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were performed to identify potential prognostic factors for overall

survival (OS) in patients with glioma. A nomogram was constructed

to predict the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS probabilities. Calibration

plots and ROC curves were used to evaluate the nomogram's

performance. All analyses were performed via the ‘survival

(v3.2.1)’, ‘ggplot2 (v3.3.3)’, and ‘rms (v6.2.0)’ R packages, with

P<0.05 considered significant.

Functional enrichment analysis and

gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

Using the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) (score ≥0.4, max 50

interactors), 110 genes interacting with the 8 senescence risk

score genes were identified. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses were

performed using the ‘ggplot2’ (v 3.5.2) and ‘clusterProfiler’ (v

4.10.1) R packages.

GSVA, an unsupervised method, evaluated gene set

enrichment based on mRNA expression data. Gene sets from the

Molecular Signatures Database (v7.0) (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) were used to

assess functional differences between high- and low-risk groups.

Heatmaps were visualized with the ‘ComplexHeatmap’ R package.

Immune microenvironment

assessment

The CIBERSORT algorithm estimated differences in

immune cell infiltration between high- and low-risk groups, while

the ESTIMATE method assessed relationships between the risk score,

stromal score, immune score, ESTIMATE score, and tumor purity.

CIBERSORT results were analyzed using weighted gene co-expression

network analysis (WGCNA). The ‘pickSoftThreshold’ function

calculated soft threshold power, and the adjacency matrix was

converted into a topological overlap matrix for hierarchical

clustering. Co-expressed gene modules were identified using dynamic

tree-cutting, and key module genes underwent GO and KEGG enrichment

analyses.

Drug sensitivity analysis

Drug sensitivity in high- and low-risk groups was

assessed using data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer

(www.cancerrxgene.org) database, combined

with gene expression data. Pearson correlation analysis evaluated

the relationship between gene expression and drug response.

scRNA-seq data processing and

analysis

Raw 10X scRNA-seq data from GSE162631(11) were downloaded from Gene Expression

Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and processed as

follows: i) data were converted into a Seurat object using the

‘Seurat’ R package (12,13); ii) quality control was performed by

excluding cells with <200 or >5,000 detected genes and those

with >15% mitochondrial content; iii) the ‘FindVariableFeatures’

function identified the top 2,000 highly variable genes; iv)

principal component analysis (PCA) and UMAP were applied for

dimensionality reduction and clustering (14); v) the ‘FindMarkers’ function

identified marker genes for each cluster (fold change >1); vi)

clusters were annotated using the ‘SingleR’ package to define cell

types (15); and vii) M1

macrophages were identified via markers NOS2 and CD80, while M2

macrophages were marked by CD163, MRC1, IL10, IL6 and ARG1. DEGs

between M1 and M2 macrophages were identified using the

‘FindMarkers’ function.

Cell lines and reverse

transcription-quantitative (RT-qPCR)

Human astrocytes (HA; cat. no. 1800; ScienCell

Research Laboratories), U251 GBM cells (CVCL_0021; Cell Bank of the

Chinese Academy of Sciences), and U87 MG GBM of unknown origin

(CVCL_0022; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured

following the suppliers' protocols. Cell line authentication was

not additionally performed in the present study, which represents a

limitation.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol™ Reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Reverse transcription

was performed with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. qPCR was

performed using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on an ABI 7500

Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The thermal cycling program consisted of an initial

denaturation at 95˚C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for

15 s and 60˚C for 1 min, with a final melt-curve stage to verify

amplification specificity. Primer sequences are provided in

Table SII. GAPDH was used as the

internal control, and relative expression levels were calculated

using the 2-ΔΔCq method (16).

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted via R

software (version 4.0.5; https://www.r-project.org/). P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Screening of DEGs and model

construction

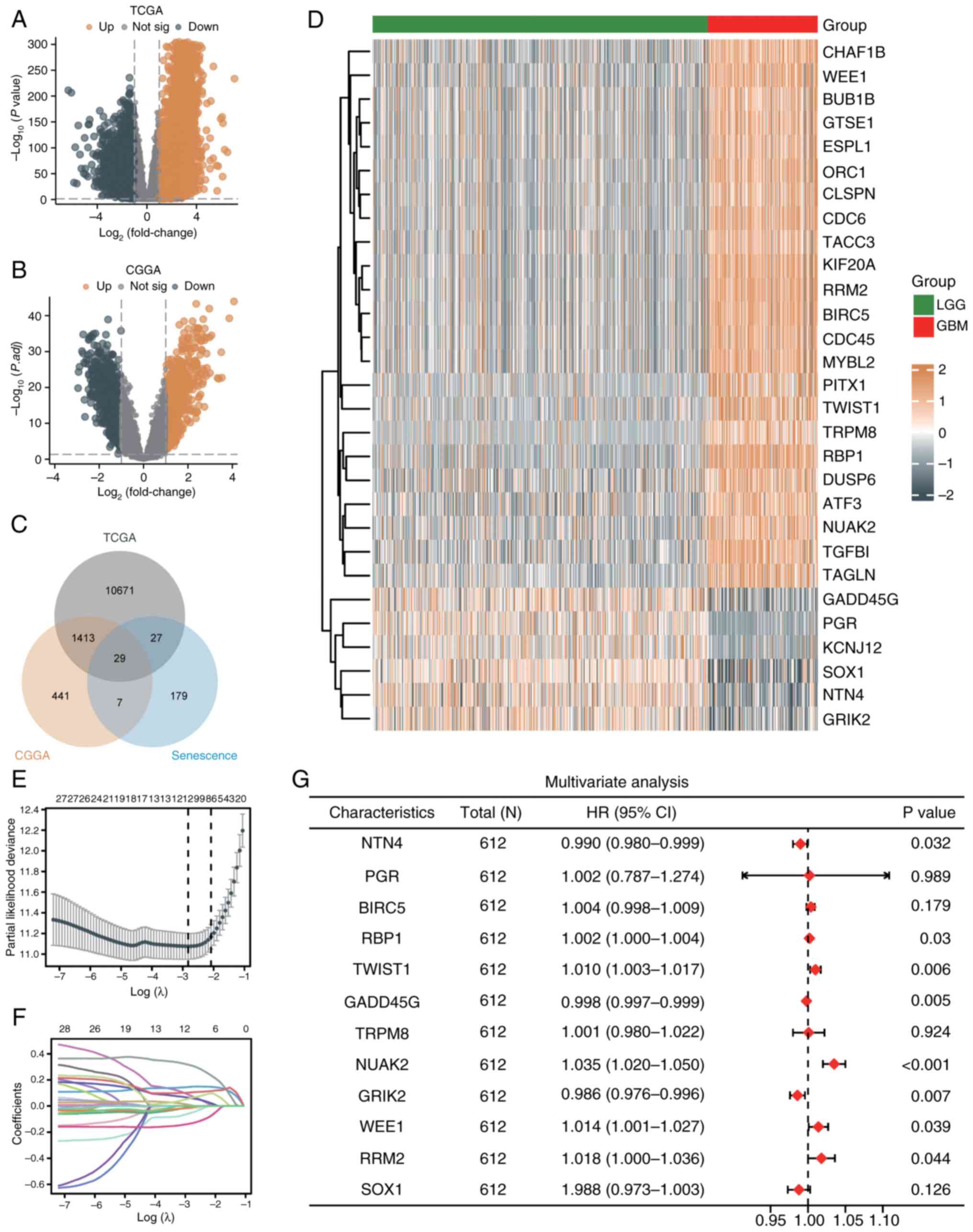

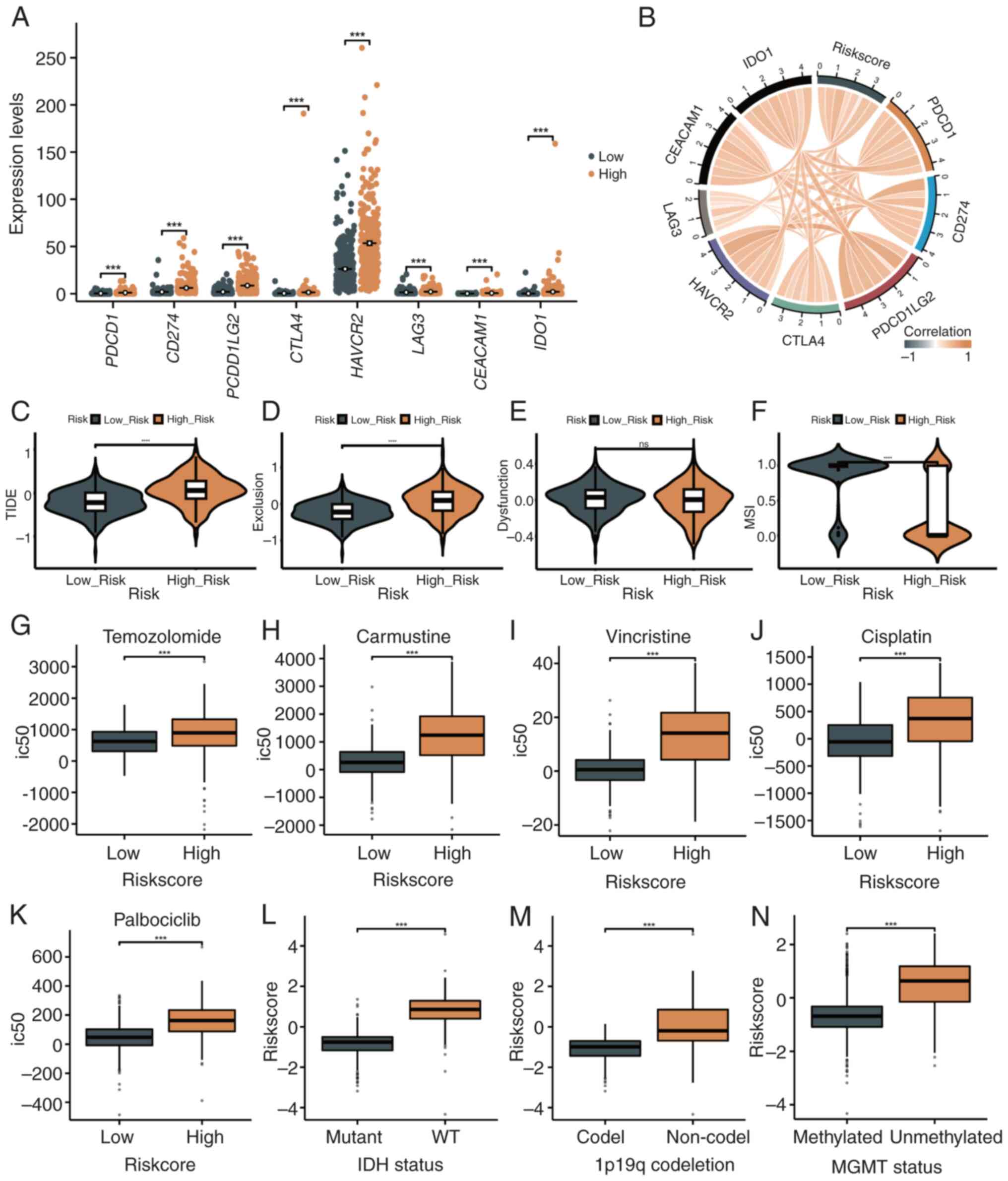

In the TCGA dataset, 12,178 DEGs were identified

(7,604 upregulated, 4,574 downregulated) (|LogFC|>1, adjusted

P<0.05) (Fig. 1A), while 1,890

DEGs were identified in the CGGA dataset (930 upregulated, 960

downregulated) (Fig. 1B). A total

of 279 senescence-related genes were obtained from the HAGR. By

intersecting DEGs from TCGA and CGGA with these genes, 29

overlapping genes were identified (Fig. 1C).

| Figure 1Screening of DEGs and model

construction. (A) Volcano plot of significantly upregulated (red)

and downregulated (blue) genes in the TCGA dataset (|LogFC|>1,

adjusted P<0.05). (B) Volcano plot of DEGs in the CGGA dataset

(|LogFC|>1, adjusted P<0.05). (C) Venn diagram showing 29

shared senescence-related genes from TCGA and CGGA datasets. (D)

Heatmap of hierarchical clustering of 29 genes, separating LGG and

GBM samples. (E) Partial likelihood deviance plot from LASSO

regression identifying 12 genes at the optimal lambda. (F)

Coefficient profiles of 12 genes across lambda values in LASSO

analysis. (G) Forest plot from multivariate Cox regression of 8

genes significantly associated with prognosis, displaying HRs and

P-values. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; TCGA, The Cancer

Genome Atlas; CGGA, Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas; LGG, low-grade

glioma; GBM, glioblastoma; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence

interval. |

To evaluate the prognostic potential of these genes,

univariate Cox regression was used (Table SI). Hierarchical clustering

separated samples into GBM-dominated (23 upregulated genes) and

LGG-dominated (6 downregulated genes) groups (Fig. 1D). Using LASSO regression, 12 genes

were selected by minimizing partial likelihood deviance (Fig. 1E), with the coefficient paths shown

in Fig. 1F. Multivariate Cox

regression further identified 8 of these genes as independently

prognostic (Fig. 1G). Based on

these 8 genes, a risk score model was constructed.

Evaluation of the prognostic

predictive ability of the risk score model

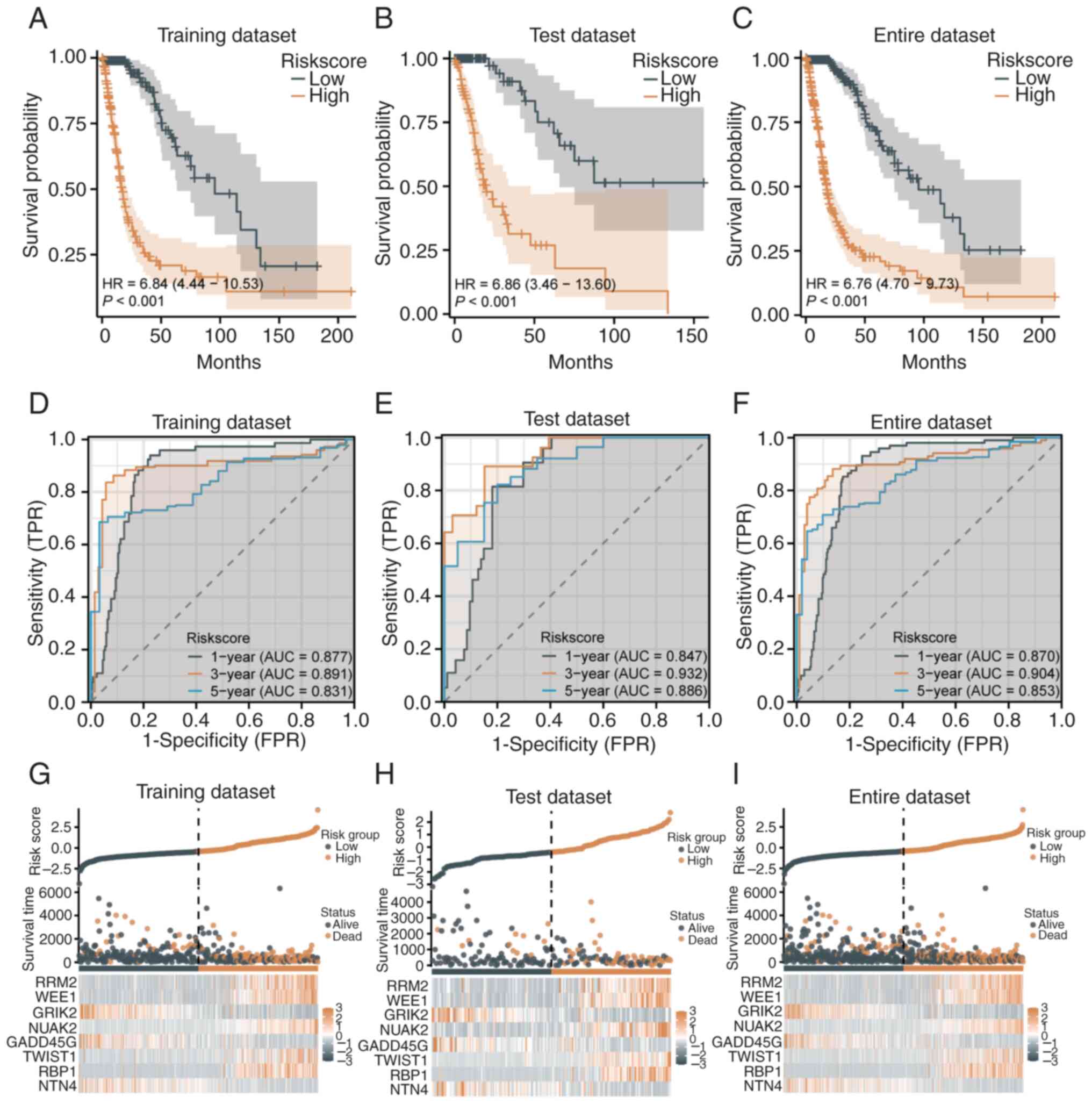

The prognostic predictive ability of the 8-gene risk

score model was further evaluated in the TCGA dataset. K-M analysis

demonstrated that high-risk patients had significantly lower

survival rates compared with low-risk patients in the training set

(HR=6.84, 95% CI=4.44-10.53, P<0.001; median survival: 16.6 vs.

95.5 months; Fig. 2A), test set

(HR=6.86, 95% CI=3.46-13.60, P<0.001; 11.9 vs. 50.5 months,

Fig. 2B), and the entire dataset

(HR=6.676, 95% CI=4.70-9.73, P<0.001; 17.7 vs. 95.5 months,

Fig. 2C). ROC curves confirmed

strong model performance, with AUC values of 0.877, 0.891 and 0.831

for 1-, 3- and 5-year predictions in the training set (Fig. 2D), 0.847, 0.932 and 0.886 in the

test set (Fig. 2E), and 0.870,

0.904 and 0.853 in the entire dataset (Fig. 2F). These results indicated high

sensitivity and specificity in predicting patient survival at

various time points. Risk score distribution and survival analysis

revealed clear stratification between high- and low-risk groups.

High-risk patients, primarily distributed on the right side, showed

shorter survival times and higher mortality in the training

(Fig. 2G) and test sets (Fig. 2H). Similar trends in the entire

dataset validated the model's generalizability and effectiveness

(Fig. 2I).

Validation of the risk score model in

the CGGA dataset

The prognostic performance of the senescence-related

risk score model was validated in the CGGA dataset. K-M analysis

showed significantly lower survival rates in the high-risk group

compared with the low-risk group (HR=3.72, 95% CI=3.00-4.60,

P<0.001; 15.6 vs. 94.4 months) (Fig. 3A). The median survival time was

notably shorter in the high-risk group, confirming the model's

effectiveness. ROC analysis demonstrated AUC values of 0.750, 0.788

and 0.785 for 1-, 3- and 5-year prognoses, respectively, indicating

favorable sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 3B). The risk score distribution

revealed a clear survival time distinction, with early-stage deaths

more frequent in the high-risk group, while the low-risk group

showed longer survival (Fig. 3C).

A heatmap highlighted differential expression of the 8 key genes,

with ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit (RRM2) and WEE1

upregulated in the high-risk group and glutamate ionotropic

receptor kainate type subunit 2 (GRIK2) and growth arrest and DNA

damage inducible gamma (GADD45G) downregulated (Fig. 3C).

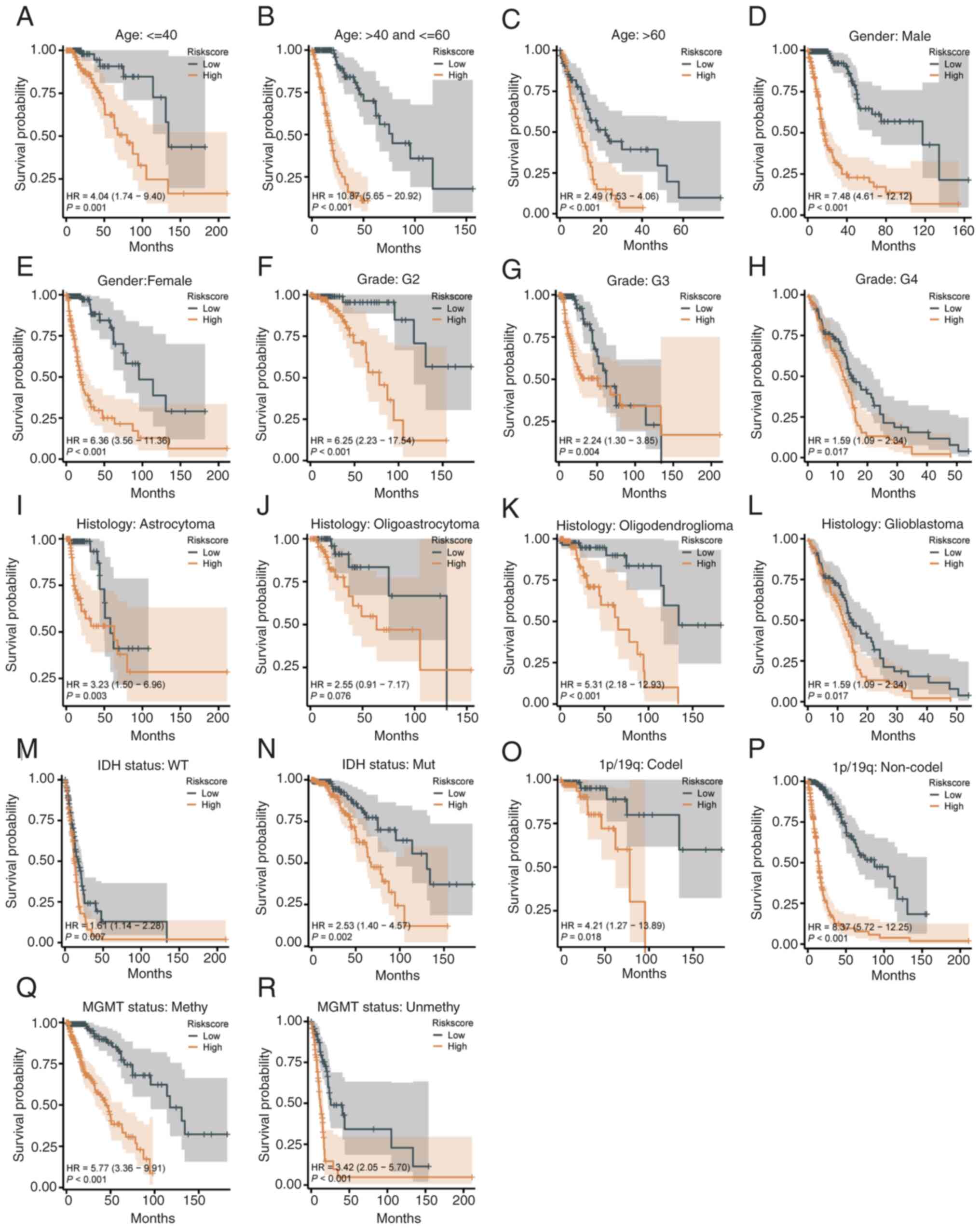

Prognostic ability of the risk score

model in different clinical and molecular subgroups

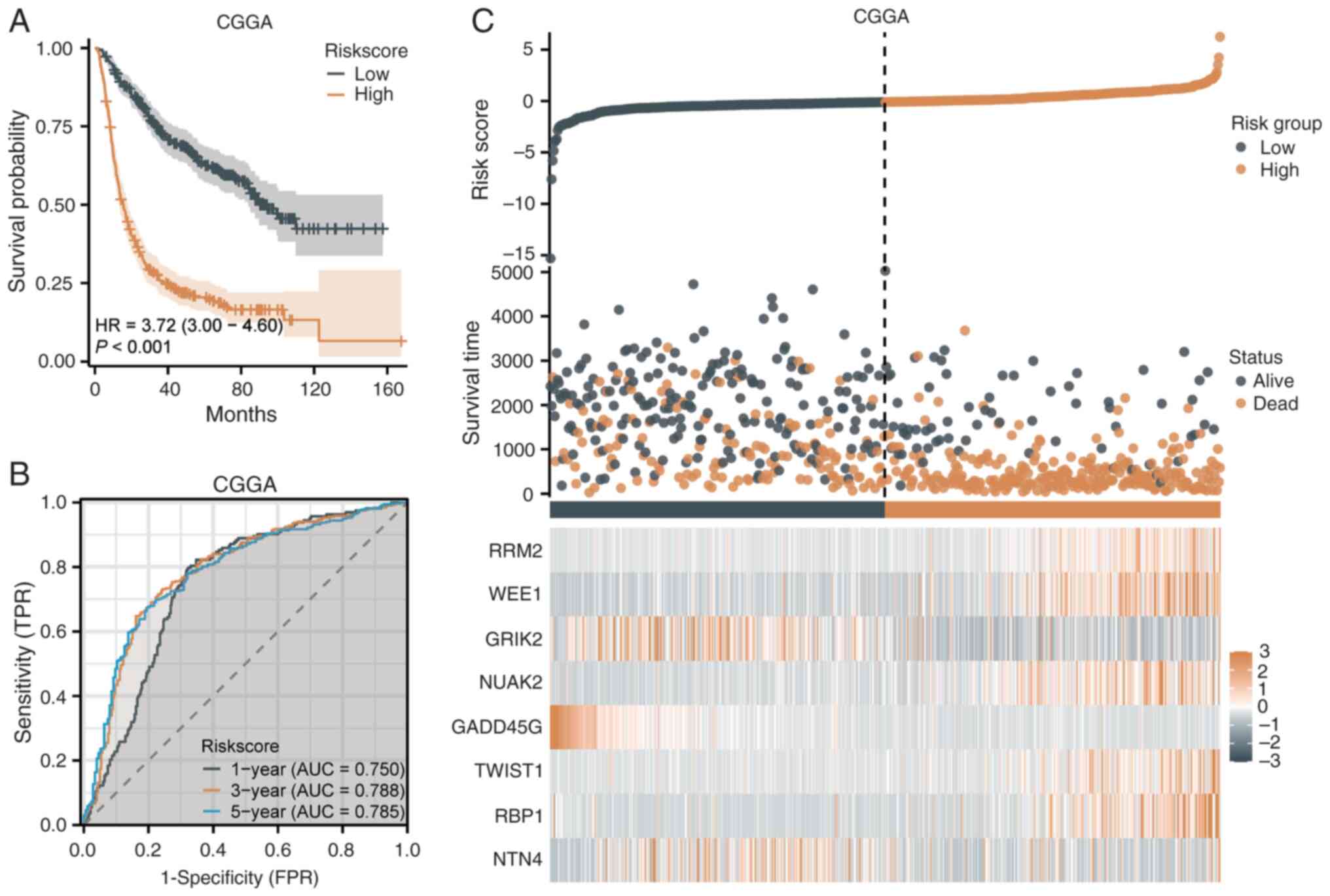

The prognostic predictive ability of the

senescence-related risk score model was assessed across clinical

and molecular subgroups (Fig.

4A-R).

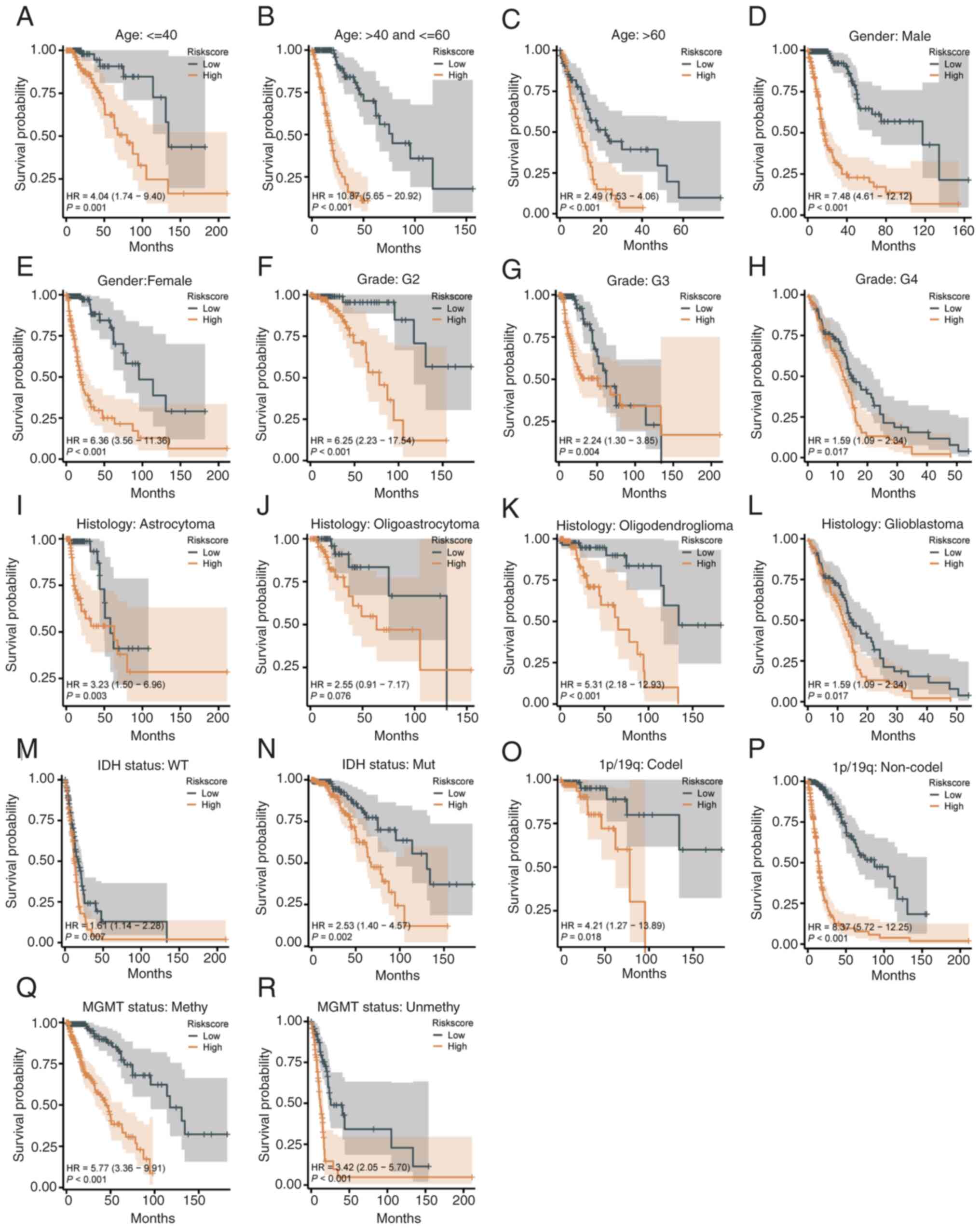

| Figure 4Prognostic ability of the risk score

model in clinical and molecular subgroups. (A-C) Kaplan-Meier

curves for age groups under 40 years (A), 40-60 years (B), and over

60 years (C), showing worse survival in high-risk patients. (D and

E) Survival stratification by sex, with high-risk groups having

worse outcomes for both males and females. (F-H) Stratification by

tumor grade (G2-G4), where high-risk patients consistently had

shorter survival. (I-L) Stratification by histological type,

showing significant differences for astrocytoma (I),

oligoastrocytoma (K) and glioblastoma (L), but not for

oligodendroglioma (J). (M and N) (M and N) Kaplan-Meier curves for

IDH wild-type (M) and IDH-mutant (N) patients, revealing worse

survival in the high-risk group. (O and P) Stratification by 1p/19q

status, with significant differences in patients with (O) and

without (P) codeletion. (Q and R) Stratification by the MGMT

methylation status, with worse survival in the high-risk group for

both methylated (Q) and unmethylated (R) patients. |

Age stratification. The model demonstrated

strong discriminatory power across all age groups. Low-risk

patients had significantly improved survival compared with

high-risk patients, with HR values of 4.04 (95% CI=1.74-9.40,

P<0.001) for all ages (Fig.

4A), 10.19 (95% CI=5.65-20.92, P<0.001) for ages 40-60

(Fig. 4B), and 2.41 (95%

CI=1.23-4.70, P=0.010) for patients over 60 (Fig. 4C). Regarding sex stratification,

both male and female low-risk patients exhibited significantly

improved survival than high-risk patients (P<0.001, Fig. 4D and E).

Tumor grade stratification. High-risk

patients had consistently shorter survival across tumor grades G2

to G4 (Fig. 4F-H).

Histological type stratification. Low-risk

patients with astrocytoma, oligoastrocytoma and GBM had improved

survival compared with high-risk patients (Fig. 4I, K and L).

For oligodendroglioma, the model showed limited discriminatory

ability, with a non-significant difference (HR=2.55, 95%

CI=0.91-7.17, P=0.076; Fig.

4J).

Molecular characteristic stratification. IDH

status: High-risk patients had worse survival in both IDH wild-type

(HR=6.77, 95% CI=3.35-13.67, P<0.001, Fig. 4M) and IDH-mutant groups (HR=2.53,

95% CI=1.40-4.56, P=0.002, Fig.

4N).

1p/19q status. Low-risk patients with 1p/19q

codeletion showed improved survival (HR=4.21, 95% CI=1.27-13.89,

P=0.018, Fig. 4O), while high-risk

patients without codeletion had significantly poorer outcomes

(HR=3.62; 95% CI=1.52-7.25; P<0.001; Fig. 4P).

MGMT methylation status. Low-risk patients

with MGMT methylation had improved survival (HR=5.77, 95%

CI=3.36-9.91, P<0.001; Fig.

4Q), with significant differences also observed in unmethylated

patients (HR=4.32, 95% CI=2.05-9.10, P<0.001; Fig. 4R).

Construction and evaluation of the

nomogram

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses

were performed, incorporating the senescence-related risk score and

clinicopathological factors (Fig.

5A). Multivariate analysis identified tumor grade, age, IDH

status and risk score as independent prognostic factors. G3

(HR=2.153, P=0.004) and G4 (HR=4.418, P<0.001) grades, along

with ages 40-60 (HR=2.943, P<0.001) and over 60 (HR=5.623,

P<0.001), were associated with poorer survival. IDH wild-type

(HR=2.017, P=0.036) and high-risk scores (HR=1.824, P=0.048) also

indicated increased mortality. A prognostic nomogram was developed

to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probabilities (Fig. 5B). G4 grade and age over 60

contributed the highest points, with total scores mapped to

survival probabilities. The nomogram was validated using the

C-index (0.853, P<2x10-16), calibration plots and ROC

curves. Calibration plots closely matched the diagonal line

(Fig. 5C). ROC curves showed AUCs

of 0.882, 0.934 and 0.902 for 1-, 3- and 5-year predictions,

confirming excellent accuracy (Fig.

5D).

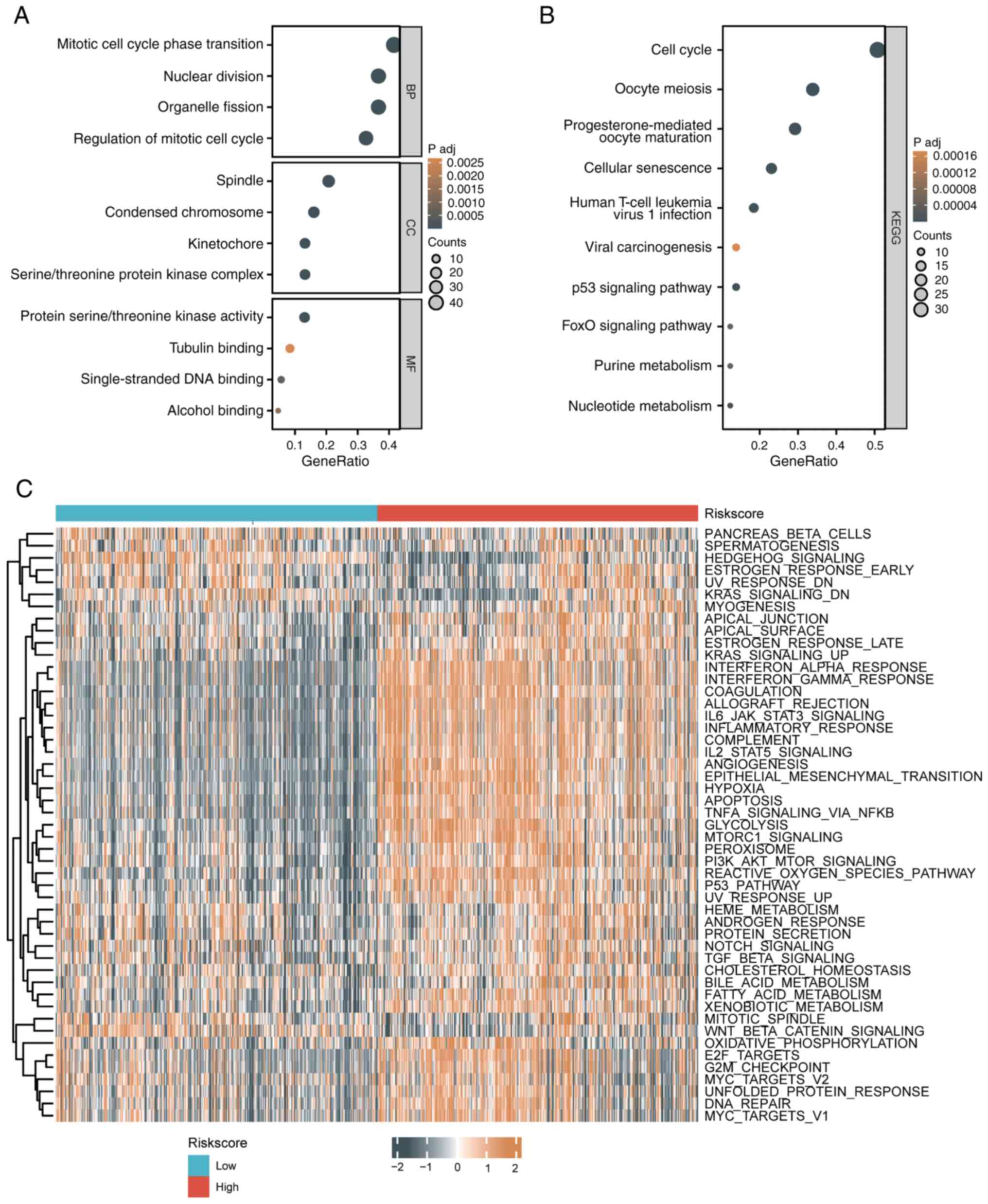

Biological function differences

between patients with high-risk and low-risk glioma

Using the STRING database, 110 genes interacting

with the 8 senescence-related risk score genes were identified

(threshold: score ≥0.4, interactors ≤50). GO analysis revealed

enrichment in processes like mitotic cell cycle transition, nuclear

division, spindle assembly and DNA binding, while KEGG analysis

highlighted pathways such as the cell cycle, senescence, p53

signaling and FoxO signaling (Fig.

6A and B). GSVA showed that

high-risk groups had upregulated pathways, including KRAS

signaling, MYC targets, G2M checkpoint, and glycolysis, whereas

low-risk groups exhibited upregulation in pathways like oxidative

phosphorylation, DNA repair and apical junctions, reflecting

differences in cell cycle, metabolism and immune responses

(Fig. 6C).

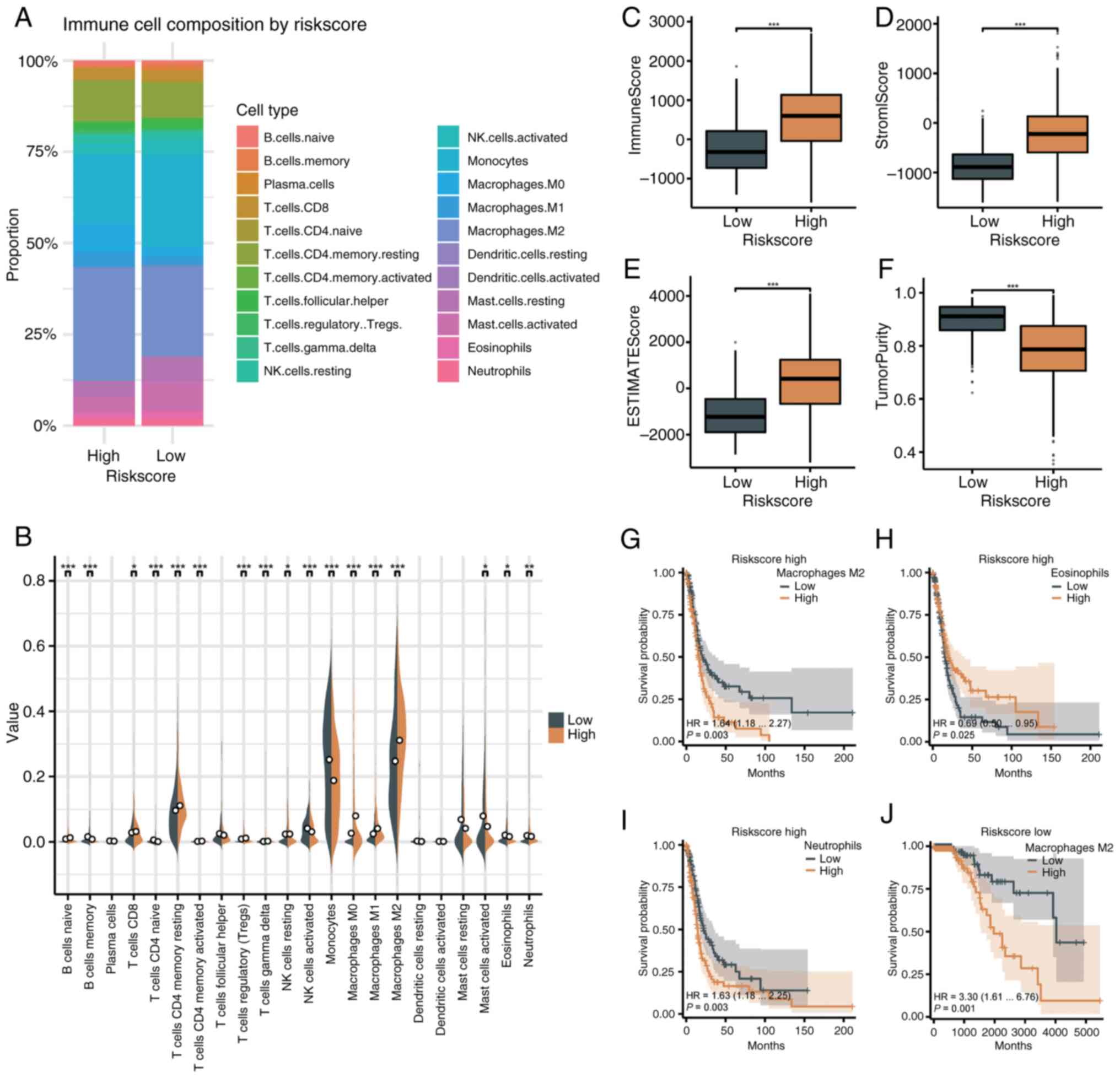

Evaluation of the immune

microenvironment in patients with high-risk and low-risk

glioma

The senescence-related risk score was analyzed with

the immune microenvironment using CIBERSORT. In the high-risk

group, M2 macrophages (31.11%) and monocytes (18.79%) were most

abundant, while monocytes (25.19%) and M2 macrophages (24.72%)

dominated in the low-risk group (Fig.

7A). High-risk tumors showed greater infiltration of immune

cells, including naïve B cells, CD8+ T cells, memory

CD4+ T cells, Tregs, gamma delta T cells, and

macrophages (M0, M1 and M2). Low-risk tumors had higher levels of

memory B cells, naïve CD4+ T cells, activated natural

killer (NK) cells, monocytes, mast cells, eosinophils and

neutrophils (Fig. 7B). Immune,

stromal and ESTIMATE scores were higher in the high-risk group

(P<0.001), while tumor purity was lower (P<0.001) (Fig. 7C-F). Greater infiltration of M2

macrophages and neutrophils in high-risk patients correlated with

worse survival (P=0.003), while higher eosinophil levels indicated

improved survival (P=0.025). In low-risk patients, M2 macrophage

infiltration was linked to poorer survival (P=0.001) (Fig. 7G-J).

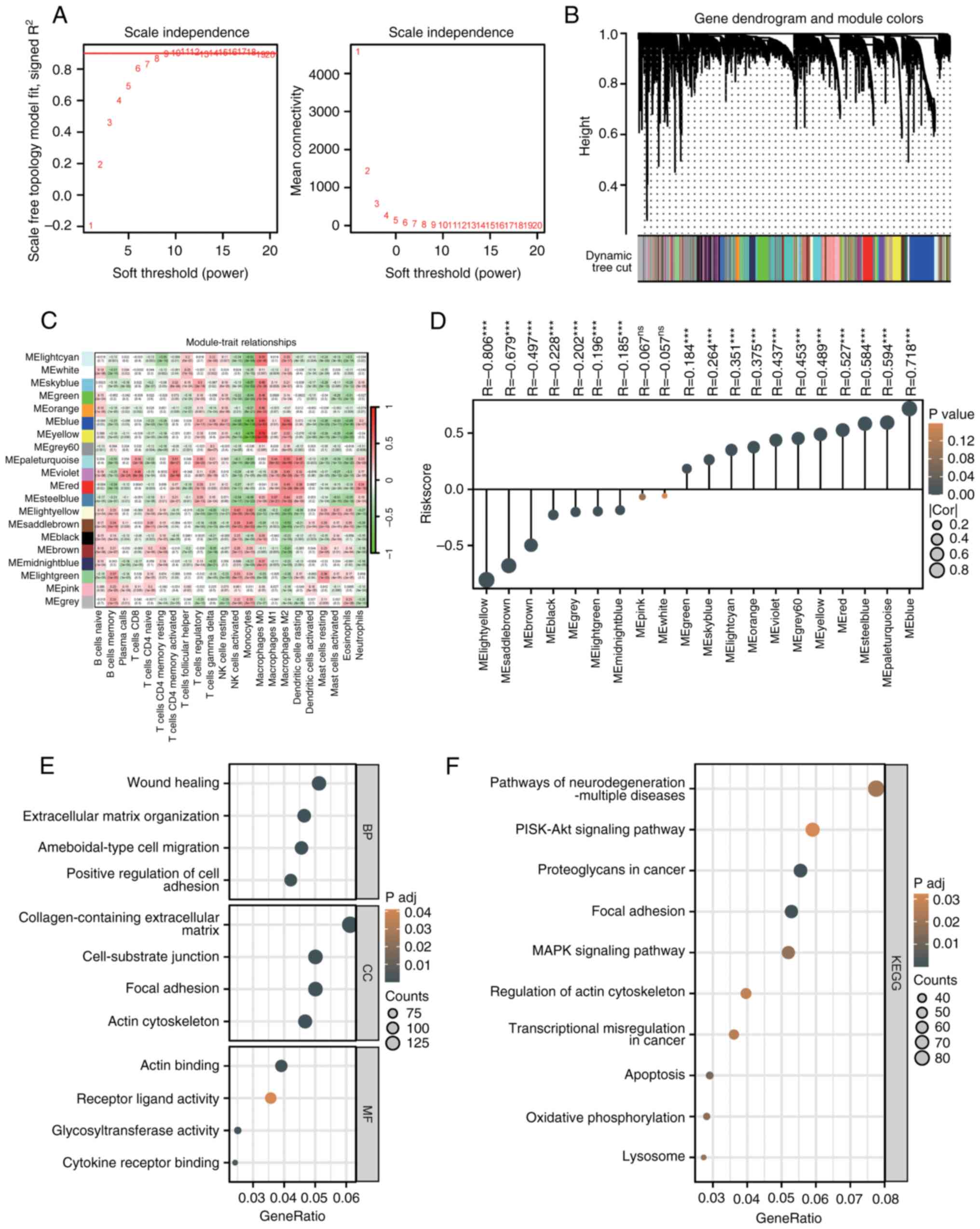

WGCNA analysis of CIBERSORT results

and functional enrichment analysis

WGCNA was performed on CIBERSORT results to identify

gene modules associated with immune cell infiltration. At a soft

threshold of 12, the R² value stabilized near 1, indicating

scale-free topology with sparse yet moderate connectivity (Fig. 8A). The gene dendrogram identified

20 co-expression modules (Fig.

8B), and correlation analysis revealed functional roles of

specific modules in the immune microenvironment (Fig. 8C). The MEblue module was positively

correlated with immunosuppressive cells (M2 macrophages, Tregs) and

negatively correlated with antitumor cells (activated NK cells),

suggesting its role in promoting an immunosuppressive

environment.

A strong positive correlation was observed between

the risk score and the MEblue module (R=0.718, P<0.001, Fig. 8D). Functional enrichment analysis

of MEblue genes revealed GO terms related to ECM organization, cell

adhesion and actin binding (Fig.

8E). KEGG analysis highlighted enrichment in PI3K-Akt

signaling, proteoglycans in cancer, focal adhesion and MAPK

signaling pathways (Fig. 8F).

Association of the risk score with

immune checkpoint molecules, immunotherapy and chemotherapy

sensitivity

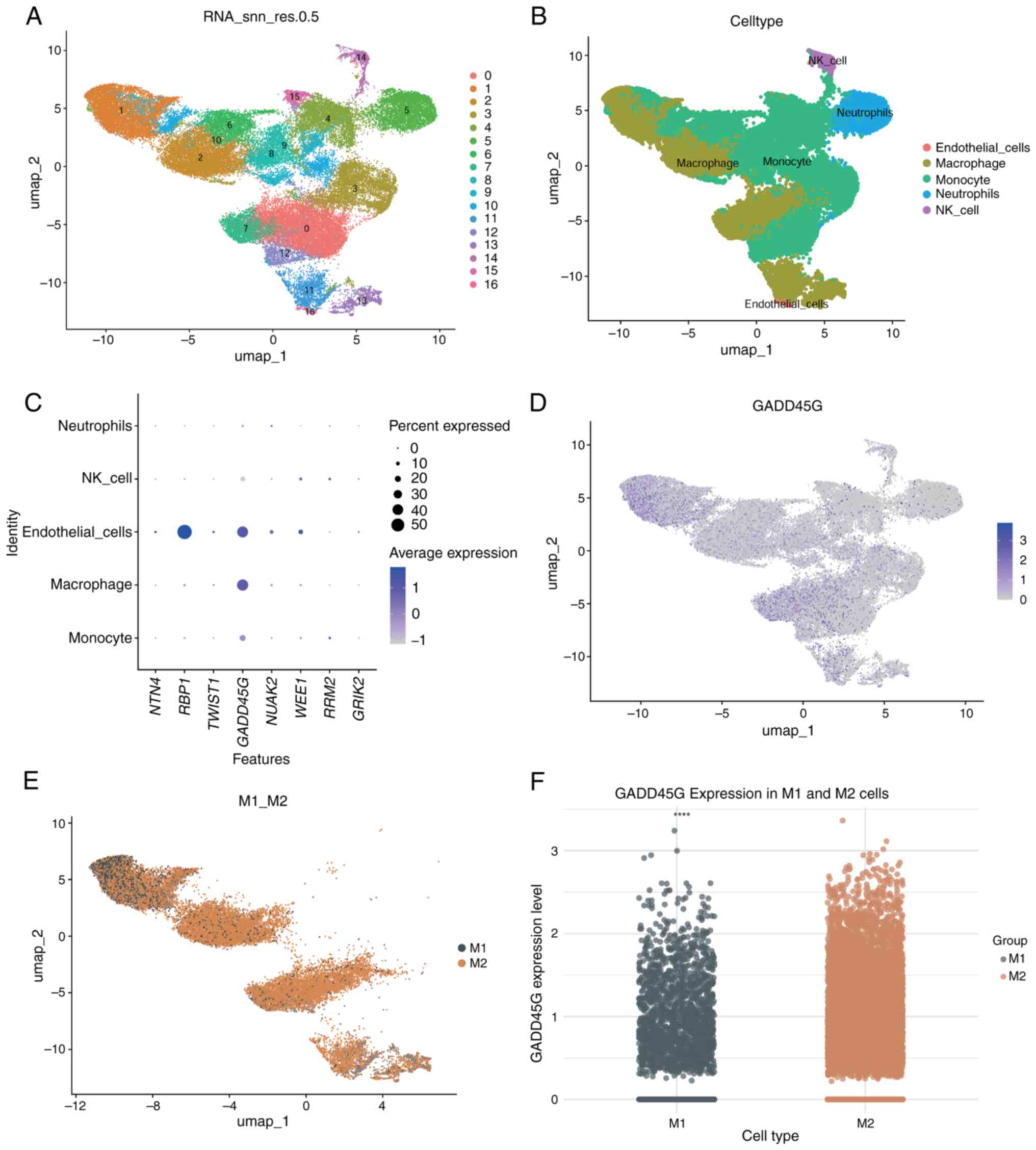

Immune checkpoint gene expression and its

association with immune evasion, suppression and the immune

microenvironment were analyzed in patients with glioma. Immune

checkpoint genes, including PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1), PDCD1LG2

(PD-L2), CTLA4, HAVCR2 (TIM-3), LAG3, CEACAM1 and IDO1, were

significantly upregulated in high-risk patients compared with

low-risk patients (P<0.001, Fig.

9A). The risk score demonstrated a strong positive correlation

with these molecules (P<0.05, Fig.

9B).

Using the TIDE algorithm, high-risk patients

exhibited higher immune evasion and exclusion scores (P<0.001,

Fig. 9C and D), while dysfunction scores did not

differ significantly (P>0.05, Fig.

9E). Higher microsatellite instability scores were observed in

the high-risk group (P<0.001, Fig.

9F).

Chemotherapy sensitivity analysis revealed reduced

sensitivity in high-risk patients to temozolomide, carmustine,

vincristine, cisplatin and palbociclib, as indicated by higher

IC50 values (P<0.001, Fig. 9G-K). High-risk patients with

wild-type IDH, 1p/19q non-codeletion, and unmethylated MGMT had

significantly higher risk scores (P<0.001, Fig. 9L-N), explaining their lower drug

sensitivity or resistance.

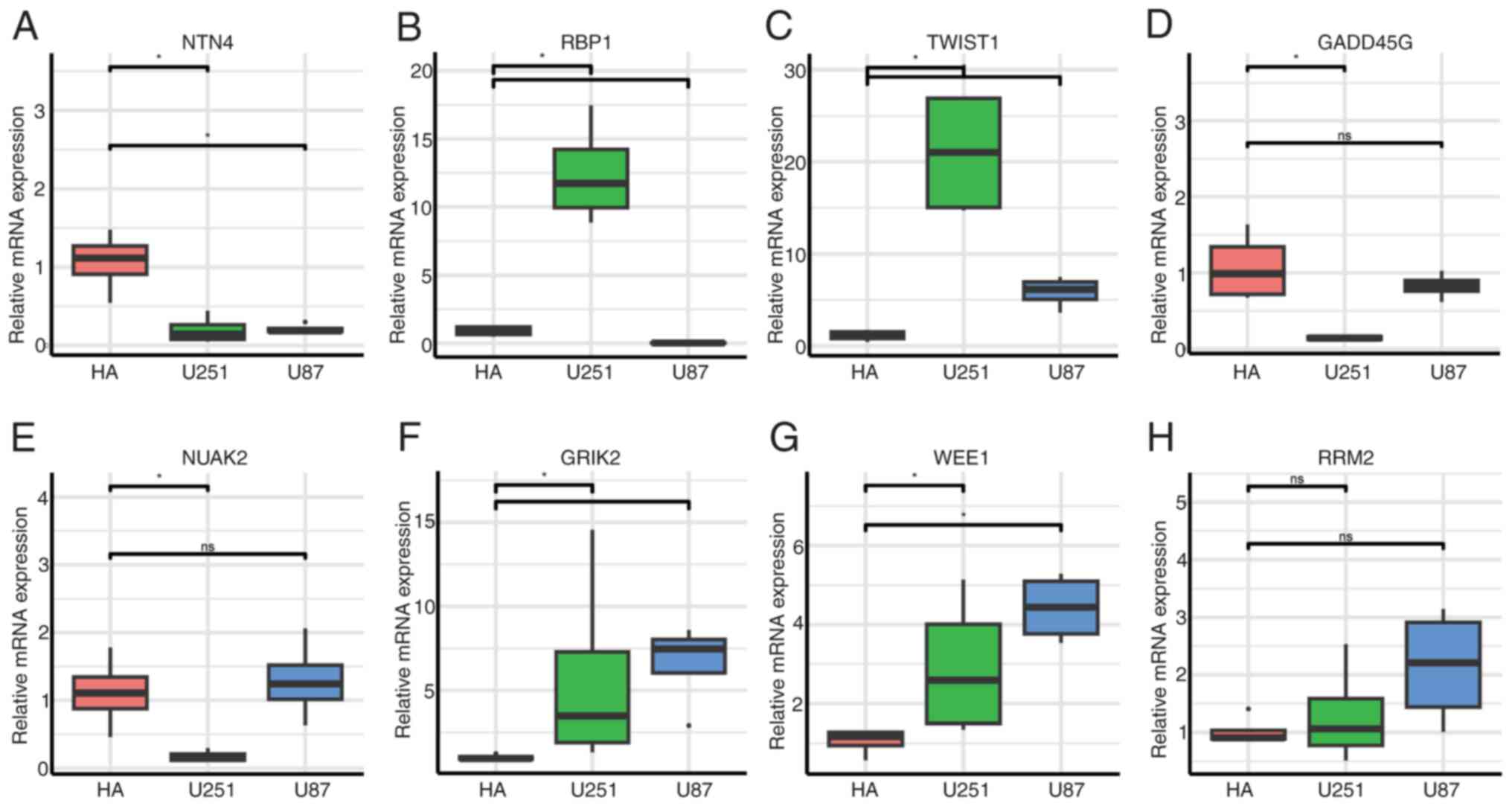

Single-cell differential expression

analysis of GADD45G in M1 and M2 macrophages

Single-cell analysis was performed on four GBM

samples from GSE162631. After filtering cells with mitochondrial

gene expression >15%, 55,757 high-quality cells were retained

(Fig. S1A). The

‘FindVariableFeatures’ function identified the top 2,000 most

variable genes (Fig. S1B).

Dimensionality reduction using PCA and UMAP resulted in 17 cell

clusters (Fig. 10A), which were

annotated with ‘SingleR’ to identify subpopulations, including

monocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, neutrophils and NK cells

(Fig. 10B). Expression analysis

of the eight model genes showed retinol-binding protein 1(RBP1) was

highly expressed in endothelial cells, while GADD45G was expressed

in both macrophages and endothelial cells (Fig. 10C). UMAP further confirmed

GADD45G's predominant expression in macrophages (Fig. 10D). M1 and M2 macrophages were

manually annotated (Fig. 10E),

and differential expression analysis revealed significantly higher

GADD45G expression in M2 macrophages compared with M1 macrophages

(Fig. 10F).

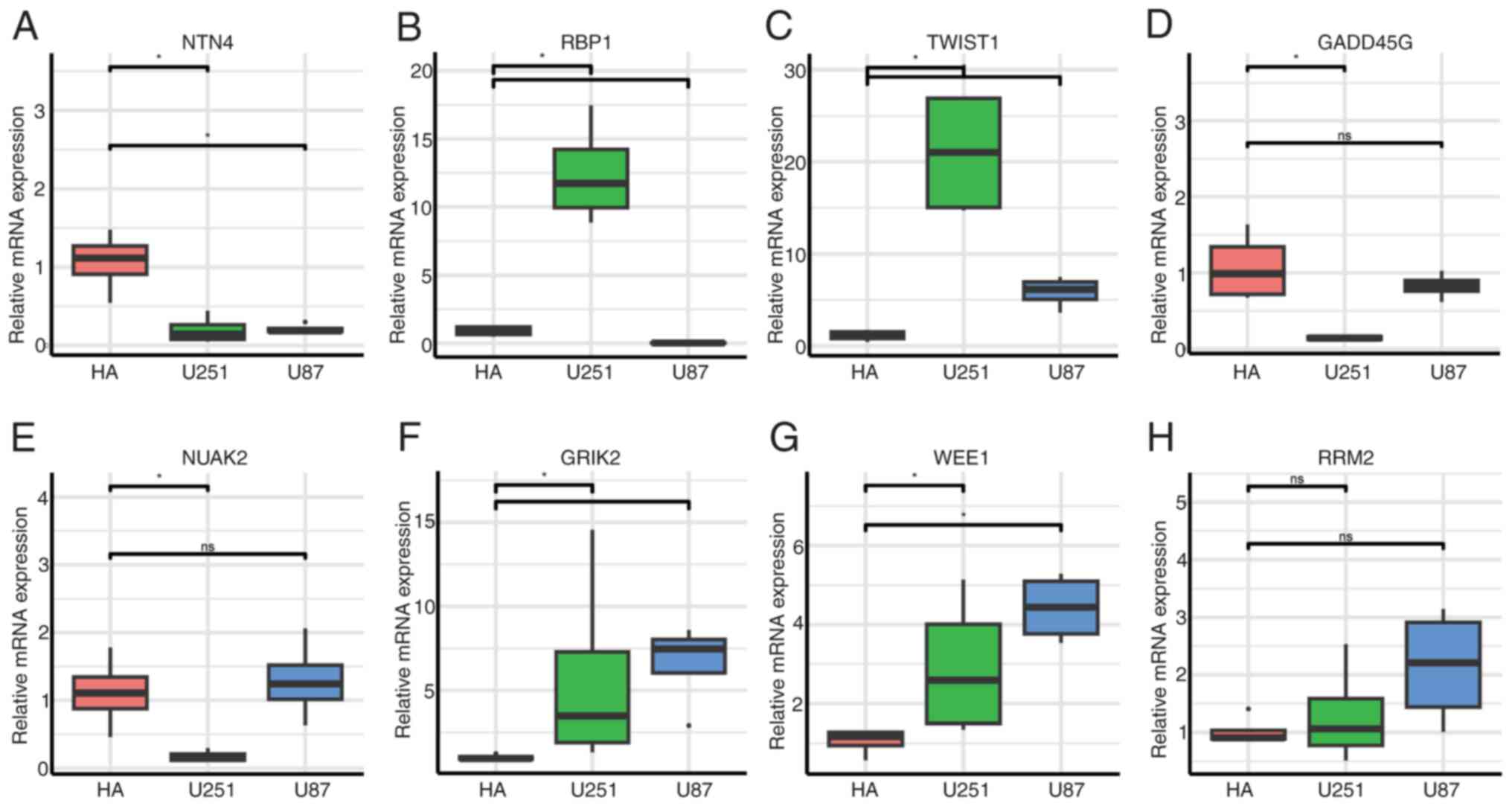

Validation of 8-gene expression by

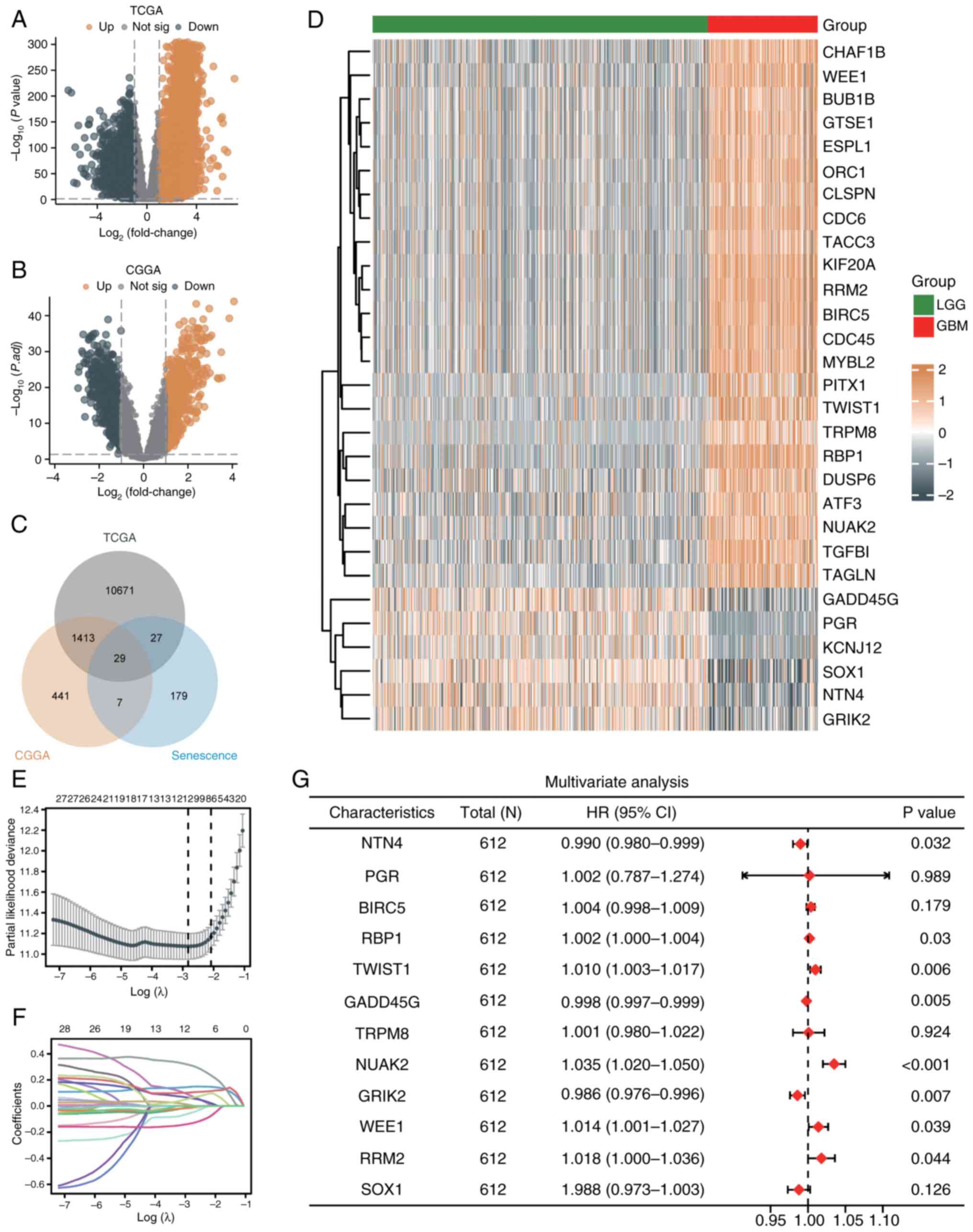

RT-qPCR in normal and GBM cells

RT-qPCR was performed to validate the expression of

eight genes [netrin-4 (NTN4), RBP1, Twist Family BHLH Transcription

Factor 1 (TWIST1), GADD45G, NUAK2, GRIK2, WEE1 and RRM2] in normal

astrocytes (HA) and GBM cell lines (U251 and U87).

Regarding NTN4, significantly higher expression was

observed in HA compared with U251 and U87 (Fig. 11A; P<0.05). RBP1 was

significantly elevated in U251 compared with HA (P<0.05;

Fig. 11B). TWIST1 was strongly

upregulated in U251 and U87 compared with HA (P<0.05; Fig. 11C). GADD45G demonstrated higher

expression in HA compared with U251, but differences between HA and

U87 were not significant (Fig.

11D). NUAK2 was increased in HA compared with U251 (P<0.05),

while no significant difference was observed between HA and U87

(Fig. 11E). GRIK2 exhibited

significantly higher expression in U251 and U87 compared with HA

(P<0.05; (Fig. 11F). WEE1

revealed increased expression in both U251 and U87 compared with HA

(P<0.05; (Fig. 11G). Regarding

RRM2, no significant differences were observed across HA, U251 and

U87 groups (Fig. 11H).

| Figure 11RT-qPCR validation of 8-gene

expression in normal astrocytes (HA) and glioblastoma cell lines

(U251 and U87). (A-H) RT-qPCR analysis of eight genes: (A) NTN4,

(B) RBP1, (C) TWIST1, (D) GADD45G, (E) NUAK2, (F) GRIK2, (G) WEE1

and (H) RRM2. *P<0.05. RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; NTN4, netrin-4; RBP1,

retinol-binding protein 1; TWIST1, Twist Family BHLH Transcription

Factor 1; GADD45G, growth arrest and DNA damage inducible gamma;

RRM2, ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit; GRIK2, glutamate

ionotropic receptor kainate type subunit 2; ns, not

significant. |

Discussion

Aging-related genes play critical roles in tumors by

regulating the cell cycle, DNA repair, metabolism and immune

evasion (6,17). In the present study, 29

aging-related genes critical to GBM progression were identified and

an eight-gene risk score model was developed with strong prognostic

and discriminative performance in the TCGA and CGGA datasets,

demonstrating its broad applicability and reliability. Unlike prior

prognostic signatures based on senescence or immune-related genes,

our model integrates aging-related genes curated from HAGR with

multi-cohort transcriptomic validation, scRNA-seq profiling and

RT-qPCR assays and extends to immune microenvironment and drug

resistance analyses. These genes participate in diverse biological

processes relevant to glioma. NTN4 is associated with poor

prognosis, likely due to its role in ECM regulation and tumor

invasion (18); RBP1 may affect

tumor differentiation and survival via the retinoic acid signaling

pathway (19); TWIST1 plays a

pivotal role in cancer progression, primarily by driving

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which in turn enhances the

invasive and metastatic potential of tumor cells (20,21);

Accumulating evidence suggests that GADD45G proteins participate in

the regulation of tumor progression, including that of gliomas,

particularly under conditions of oncogenic stress (22-24);

NUAK2 is involved in neural tube development, and its aberrant

expression is strongly associated with tumor progression and poor

patient prognosis, including in GBM (25-27);

GRIK2 has been reported to participate in the development of

gastric (28,29); however, its potential involvement

in glioma has not yet been clearly elucidated; WEE1, a key cell

cycle regulator, has shown therapeutic potential in GBM clinical

trials (30); and RRM2 has been

reported to facilitate the proliferation, migration and invasive

behavior of human GBM cells, while simultaneously suppressing

apoptosis (31). Collectively,

these genes converge on pathways of cell cycle regulation, DNA

damage response, invasion and metabolic adaptation, consistent with

their reported functions in glioma biology. Their integration into

a unified signature highlights their combined prognostic value.

The risk score model showed strong predictive power

across clinical and molecular subgroups, demonstrating its utility

in both overall and subgroup prognosis. High-risk patients with

wild-type IDH and 1p/19q non-codeletion had significantly lower

survival rates, consistent with these molecular features being key

glioma prognostic factors. IDH mutations are linked to improved

prognosis and treatment response, while 1p/19q codeletion enhances

sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (10). To improve clinical applicability,

the risk score model was integrated with clinicopathological

features to construct a nomogram, which exhibited high predictive

accuracy and consistency. This validates the model's utility in

providing valuable prognostic insights across diverse molecular

subtypes and clinical contexts.

GO and KEGG analyses highlighted key biological

functions and pathways related to the risk score model, including

the cell cycle, DNA repair and metabolism. WEE1, a critical

regulator of cell cycle checkpoints, prevents damaged cells from

entering mitosis (32). KEGG

analysis linked the model genes to pathways such as the cell cycle,

cellular senescence, p53 signaling and FoxO signaling, which are

central to tumorigenesis and progression. For instance, p53

suppresses glioma by regulating the cell cycle and inducing

apoptosis (33,34). Cellular senescence, triggered by

DNA damage, telomere shortening, or oncogenic stress, plays a dual

role in glioma by suppressing tumor formation while potentially

promoting progression via proinflammatory factor secretion

(35).

GSVA showed significant upregulation of

cancer-related pathways, including KRAS signaling, MYC targets and

E2F targets, in the high-risk group. KRAS drives sustained

proliferation and survival via the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways,

contributing to poor prognosis and therapy resistance in GBM

(36,37). MYC overexpression promotes

malignant transformation and high proliferative capacity, with

MYC-regulated genes playing critical roles in cancer progression

(38,39). In the low-risk group, pathways

related to oxidative phosphorylation, DNA repair, tight junctions

and interferon responses were upregulated. Enhanced oxidative

phosphorylation, indicating a reliance on mitochondrial energy

production, is linked to reduced tumor proliferation and improved

prognosis (40). Upregulated DNA

repair-related genes promote genomic stability, reduce

carcinogenesis risk, and improve chemotherapy response (41,42).

The TME plays a vital role in tumor growth,

metastasis and treatment response, consisting of immune cells,

fibroblasts, vascular cells and stromal components (43). In the high-risk group, elevated

infiltration of M2 macrophages, an immunosuppressive subtype linked

to poor prognosis, was observed. M2 macrophages promote glioma

growth and immune evasion by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines

and stimulating angiogenesis (44). Regulatory T cells (Tregs), also

abundant in this group, suppress antitumor responses by inhibiting

effector T-cell and NK cell activity via cytokines like IL-10 and

TGF-β (45). High-risk patients

exhibited significantly higher immune, stromal and ESTIMATE scores

(P<0.001), indicating a greater abundance of nontumor components

such as fibroblasts and stromal cells, which promote tumor

expansion and invasion by secreting growth factors and

matrix-degrading enzymes (46).

These components, along with immunosuppressive cells, create

barriers that reduce the effectiveness of chemotherapy and

radiotherapy, potentially explaining the poorer therapeutic

responses in patients with high-risk GBM.

WGCNA analysis of CIBERSORT results identified the

MEblue module as positively correlated with immunosuppressive cells

(M2 macrophages and Tregs) and negatively correlated with antitumor

immune cells (activated NK cells), suggesting an association in

immune evasion and tumor progression. GO and KEGG analyses showed

that MEblue genes regulate ECM organization and cell adhesion,

which are known to support the immunosuppressive tumor environment.

ECM remodeling, a key step in cancer progression, involves proteins

and enzymes like collagen, matrix metalloproteinases, and integrins

(47). In gliomas, ECM remodeling

promotes tumor invasion and metastasis through cell-matrix

interactions and focal adhesions. Integrins bind ECM components,

such as fibronectin, and activate downstream pathways, including

PI3K-Akt and MAPK, which regulate cell proliferation, survival and

migration, driving GBM progression (48,49).

In the high-risk group, key immune checkpoint genes,

including PDCD1 (PD-1), CD274 (PD-L1) and PDCD1LG2 (PD-L2), were

significantly upregulated, consistent with an immunosuppressive

state. PD-1 binding to PD-L1 or PD-L2 reduces T-cell proliferation

and cytotoxicity, allowing tumor cells to evade immune surveillance

(50). High CTLA-4 expression

further supports immune evasion by inhibiting T-cell activation

through competitive binding to B7 molecules (51). The high-risk group also exhibited

significantly higher TIDE scores (P<0.001), consistent with

stronger immune evasion potential and poorer responses to immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Elevated immune exclusion scores in this

group were associated with reduced T-cell infiltration and

cytotoxic activity through physical and chemical barriers, aligning

with findings of increased immune and stromal components in the

high-risk group.

The glioma immune microenvironment is not static but

evolves with tumor stage, progression and recurrence. GBM generally

exhibits higher levels of M2 macrophages and exhausted T cells than

LGG, and recurrent tumors often show stromal fibrosis and stronger

immunosuppressive signaling (52-54).

In the present study, the computational analysis could not capture

these stage-specific dynamics, which should be addressed in future

studies using longitudinal sampling, spatial transcriptomics and

multiplex immunohistochemistry.

Drug sensitivity analysis showed that high-risk

patients were less responsive to chemotherapeutic agents, including

temozolomide, carmustine, vincristine, cisplatin and palbociclib,

compared with low-risk patients. In the present study, GSVA and

KEGG enrichment analyses indicated that the high-risk group was

enriched in PI3K/AKT/mTOR, E2F target, and KRAS signaling pathways,

which are known to promote tumor survival, inhibit apoptosis, and

drive therapeutic resistance in glioma (37,55,56).

Key genes in our signature, including RRM2 and WEE1, regulate DNA

synthesis and G2/M checkpoint control, respectively, mechanisms

that facilitate DNA repair and contribute to resistance to

temozolomide and radiotherapy (57,58).

Furthermore, immune deconvolution revealed that the high-risk

subgroup exhibited increased infiltration of M2 macrophages and

Tregs, which secrete immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and

TGF-β, thereby limiting antitumor immunity and drug efficacy

(59). These changes are

consistent with the immunosuppressive remodeling and stromal

fibrosis observed in advanced gliomas (60). By contrast, the low-risk group was

enriched for IDH mutation, 1p/19q codeletion, and MGMT promoter

methylation, well-established molecular features associated with

improved chemosensitivity and prognosis (61-63).

Taken together, these findings suggest that the diminished drug

sensitivity in the high-risk group results from the combined

effects of cell-cycle dysregulation (RRM2 and WEE1),

PI3K/AKT-mediated survival signaling, and an immunosuppressive TME,

consistent with previous mechanistic studies in glioma biology.

In summary, the present study highlights the

critical role of aging-related genes in glioma and introduces a

gene expression-based risk score model for predicting patient

survival. These findings offer new insights and potential targets

for personalized treatment and prognosis. However, this study has

several limitations. Functional validation experiments (for

example, knockdown/overexpression assays and in vivo models)

were not performed, and drug sensitivity and immune analyses relied

on computational inference without experimental confirmation. The

scRNA-seq dataset was relatively small, and the RT-qPCR validation

was conducted only in established glioma cell lines (U87, U251 and

HA). Although these models are widely used and provide preliminary

support for the expression patterns of the signature genes, they do

not fully recapitulate the molecular heterogeneity and TME

interactions observed in patient tissues. Long-term cultured cell

lines may acquire genetic drift and altered signaling pathways,

potentially affecting gene expression and treatment response.

Therefore, future studies should include validation using

patient-derived glioma tissues, organoid cultures, or xenograft

models to better reflect the in vivo tumor context and

confirm clinical relevance. In addition, grade-specific analyses

for LGG and GBM were not conducted. These limitations warrant

further validation in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Data processing and identification of

variable genes. (A) Cells with >15% mitochondrial gene

expression were filtered, leaving 55,757 high-quality cells. (B)

The top 2,000 most variable genes identified via the

‘FindVariableFeatures’ function.

Each gene was evaluated for its

association with overall survival in 698 patients with glioma.

Sequences of primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

at the following URL: (portal.gdc.cancer.gov) (https://www.cgga.org.cn/download.jsp).

Authors' contributions

QZ conceptualized the study, and wrote, reviewed and

edited the manuscript. ZL developed methodology and wrote the

original draft. LZ and PL performed data visualization. XLi and

XLiang conducted formal analysis. TW, JY and QY curated data. QZ

and ZL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von

Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD,

Kleihues P and Ellison DW: The 2016 world health organization

classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary.

Acta Neuropathol. 131:803–820. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia

A, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS: CBTRUS Statistical report:

Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in

the United States in 2011-2015. Neuro Oncol. 20 (Suppl 4):iv1–iv86.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R,

Rasheed BA, Yuan W, Kos I, Batinic-Haberle I, Jones S, Riggins GJ,

et al: IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med.

360:765–773. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wen PY and Kesari S: Malignant gliomas in

adults. N Engl J Med. 359:492–507. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Campisi J: Aging, cellular senescence, and

cancer. Annu Rev Physiol. 75:685–705. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L,

Serrano M and Kroemer G: The hallmarks of aging. Cell.

153:1194–1217. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

De Carvalho DD, You JS and Jones PA: DNA

methylation and cellular reprogramming. Trends Cell Biol.

20:609–617. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Hinshaw DC and Shevde LA: The tumor

microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res.

79:4557–4566. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hoxhaj G and Manning BD: The PI3K-AKT

network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer

metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:74–88. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Weller M, van den Bent M, Preusser M, Le

Rhun E, Tonn JC, Minniti G, Bendszus M, Balana C, Chinot O, Dirven

L, et al: EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse

gliomas of adulthood. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:170–186.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Xie Y, He L, Lugano R, Zhang Y, Cao H, He

Q, Chao M, Liu B, Cao Q, Wang J, et al: Key molecular alterations

in endothelial cells in human glioblastoma uncovered through

single-cell RNA sequencing. JCI Insight. 6(e150861)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J,

Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck

EM, et al: Highly parallel Genome-wide expression profiling of

individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 161:1202–1214.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Habicht J, Mooneyham A, Shetty M, Zhang X,

Shridhar V, Winterhoff B, Zhang Y, Cepela J, Starr T, Lou E and

Bazzaro M: UNC-45A is preferentially expressed in epithelial cells

and binds to and co-localizes with interphase MTs. Cancer Biol

Ther. 20:1304–1313. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Becht E, McInnes L, Healy J, Dutertre CA,

Kwok IWH, Ng LG, Ginhoux F and Newell EW: Dimensionality reduction

for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat Biotechnol: Dec 3,

2018 (Epub ahead of print) doi: 10.1038/nbt.4314.

|

|

15

|

Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V,

Hsu A, Chak S, Naikawadi RP, Wolters PJ, Abate AR, et al:

Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a

transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 20:163–172.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ and van

Deursen JM: Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease:

From mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med. 21:1424–1435. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li L, Huang Y, Gao Y, Shi T, Xu Y, Li H,

Hyytiäinen M, Keski-Oja J, Jiang Q, Hu Y and Du Z: EGF/EGFR

upregulates and cooperates with Netrin-4 to protect glioblastoma

cells from DNA damage-induced senescence. BMC Cancer.

18(1215)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Guo Z, Zhao Y, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Wang R, Liu

W, Zhang C and Yang X: Cellular retinol-binding protein 1: A

therapeutic and diagnostic tumor marker. Mol Biol Rep.

50:1885–1894. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yang J, Mani SA, Donaher JL, Ramaswamy S,

Itzykson RA, Come C, Savagner P, Gitelman I, Richardson A and

Weinberg RA: Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an

essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 117:927–939.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yu X, He T, Tong Z, Liao L, Huang S,

Fakhouri WD, Edwards DP and Xu J: Molecular mechanisms of

TWIST1-regulated transcription in EMT and cancer metastasis. EMBO

Rep. 24(e56902)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hollander MC, Sheikh MS, Bulavin DV,

Lundgren K, Augeri-Henmueller L, Shehee R, Molinaro TA, Kim KE,

Tolosa E, Ashwell JD, et al: Genomic instability in

Gadd45a-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 23:176–184. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Qiu W, David D, Zhou B, Chu PG, Zhang B,

Wu M, Xiao J, Han T, Zhu Z, Wang T, et al: Down-regulation of

growth arrest DNA damage-inducible gene 45beta expression is

associated with human hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol.

162:1961–1974. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang W, Huper G, Guo Y, Murphy SK, Olson

JA Jr and Marks JR: Analysis of methylation-sensitive transcriptome

identifies GADD45a as a frequently methylated gene in breast

cancer. Oncogene. 24:2705–2714. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Li Y, Song X, Liu L and Yue L: NUAK2

silencing inhibits the proliferation, migration and

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of cervical cancer cells via

upregulating CYFIP2. Mol Med Rep. 24(817)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Namiki T, Yaguchi T, Nakamura K, Valencia

JC, Coelho SG, Yin L, Kawaguchi M, Vieira WD, Kaneko Y, Tanemura A,

et al: NUAK2 amplification coupled with PTEN deficiency promotes

melanoma development via CDK activation. Cancer Res. 75:2708–2715.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tang L, Tong SJ, Zhan Z, Wang Q, Tian Y

and Chen F: Expression of NUAK2 in gastric cancer tissue and its

effects on the proliferation of gastric cancer cells. Exp Ther Med.

13:676–680. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Wang R, Su D, Liu Y, Huang H, Qiu J, Cao

Z, Yang G, Chen H, Luo W, Tao J, et al: The NF-kappaB/NUAK2

signaling axis regulates pancreatic cancer progression by targeting

SMAD2/3. iScience. 27(109406)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wu CS, Lu YJ, Li HP, Hsueh C, Lu CY, Leu

YW, Liu HP, Lin KH, Hui-Ming Huang T and Chang YS: Glutamate

receptor, ionotropic, kainate 2 silencing by DNA hypermethylation

possesses tumor suppressor function in gastric cancer. Int J

Cancer. 126:2542–2552. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Sanai N, Li J, Boerner J, Stark K, Wu J,

Kim S, Derogatis A, Mehta S, Dhruv HD, Heilbrun LK, et al: Phase 0

Trial of AZD1775 in First-recurrence glioblastoma patients. Clin

Cancer Res. 24:3820–3828. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Li C, Zheng J, Chen S, Huang B, Li G, Feng

Z, Wang J and Xu S: RRM2 promotes the progression of human

glioblastoma. J Cell Physiol. 233:6759–6767. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Aarts M, Sharpe R, Garcia-Murillas I,

Gevensleben H, Hurd MS, Shumway SD, Toniatti C, Ashworth A and

Turner NC: Forced mitotic entry of S-phase cells as a therapeutic

strategy induced by inhibition of WEE1. Cancer Discov. 2:524–539.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Xiao Y, Li M, Ma T, Ning H and Liu L:

AMG232 inhibits angiogenesis in glioma through the p53-RBM4-VEGFR2

pathway. J Cell Sci. 136(jcs260270)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhao Y, Chen Y, Wei L, Ran J, Wang K, Zhu

S and Liu Q: p53 inhibits the Urea cycle and represses polyamine

biosynthesis in glioma cell lines. Metab Brain Dis. 38:1143–1153.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Herranz N and Gil J: Mechanisms and

functions of cellular senescence. J Clin Invest. 128:1238–1246.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Ryan MB and Corcoran RB: Therapeutic

strategies to target RAS-mutant cancers. Nat Rev Clin Oncol.

15:709–720. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zuchegna C, Leone S, Romano A, Porcellini

A and Messina S: KRAS is a molecular determinant of platinum

responsiveness in glioblastoma. BMC Cancer. 24(77)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Chen Z, Yan X, Miao C, Liu L, Liu S, Xia

Y, Fang W, Zheng D and Luo Q: Targeting MYH9 represses

USP14-mediated NAP1L1 deubiquitination and cell proliferation in

glioma. Cancer Cell Int. 23(220)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Stine ZE, Walton ZE, Altman BJ, Hsieh AL

and Dang CV: MYC, Metabolism, and Cancer. Cancer Discov.

5:1024–1039. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Qiu X, Li Y and Zhang Z: Crosstalk between

oxidative phosphorylation and immune escape in cancer: A new

concept of therapeutic targets selection. Cell Oncol (Dordr).

46:847–865. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ashton TM, McKenna WG, Kunz-Schughart LA

and Higgins GS: Oxidative phosphorylation as an emerging target in

cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 24:2482–2490. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kuo CL, Ponneri Babuharisankar A, Lin YC,

Lien HW, Lo YK, Chou HY, Tangeda V, Cheng LC, Cheng AN and Lee AY:

Mitochondrial oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment and

cancer immunoescape: Foe or friend? J Biomed Sci.

29(74)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Mun JY, Leem SH, Lee JH and Kim HS: Dual

relationship between stromal cells and immune cells in the tumor

microenvironment. Front Immunol. 13(864739)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Deng Y, Chen Q, Wan C, Sun Y, Huang F, Hu

Y and Yang K: Microglia and macrophage metabolism: A regulator of

cerebral gliomas. Cell Biosci. 14(49)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Li C, Jiang P, Wei S, Xu X and Wang J:

Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: New mechanisms,

potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol Cancer.

19(116)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Feng B, Wu J, Shen B, Jiang F and Feng J:

Cancer-associated fibroblasts and resistance to anticancer

therapies: Status, mechanisms, and countermeasures. Cancer Cell

Int. 22(166)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Borst R, Meyaard L and Pascoal Ramos MI:

Understanding the matrix: Collagen modifications in tumors and

their implications for immunotherapy. J Transl Med.

22(382)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wei R, Zhou J, Bui B and Liu X: Glioma

actively Orchestrate a self-advantageous extracellular matrix to

promote recurrence and progression. BMC Cancer.

24(974)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Ellert-Miklaszewska A, Poleszak K,

Pasierbinska M and Kaminska B: Integrin signaling in glioma

pathogenesis: From biology to therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

21(888)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Wu M, Huang Q, Xie Y, Wu X, Ma H, Zhang Y

and Xia Y: Improvement of the anticancer efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1

blockade via combination therapy and PD-L1 regulation. J Hematol

Oncol. 15(24)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Pulanco MC, Madsen AT, Tanwar A, Corrigan

DT and Zang X: Recent advancements in the B7/CD28 immune checkpoint

families: New biology and clinical therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol

Immunol. 20:694–713. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Vidyarthi A, Agnihotri T, Khan N, Singh S,

Tewari MK, Radotra BD, Chatterjee D and Agrewala JN: Predominance

of M2 Macrophages in gliomas leads to the suppression of local and

systemic immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 68:1995–2004.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Ravi VM, Neidert N, Will P, Joseph K,

Maier JP, Kückelhaus J, Vollmer L, Goeldner JM, Behringer SP,

Scherer F, et al: T-cell dysfunction in the glioblastoma

microenvironment is mediated by myeloid cells releasing

interleukin-10. Nat Commun. 13(925)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Puviindran BJ, Wallace S, Ayasoufi K,

Lerner E and Fecci PE: Within and beyond the tumor: Mechanisms of

glioblastoma-induced immunosuppression. Neurooncol Adv. 7 (Suppl

4):iv4–iv18. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Zajac A, Sumorek-Wiadro J, Langner E,

Wertel I, Maciejczyk A, Pawlikowska-Pawlęga B, Pawelec J, Wasiak M,

Hułas-Stasiak M, Bądziul D, et al: Involvement of PI3K pathway in

glioma cell resistance to temozolomide treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

22(5155)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Meng J, Qian W, Yang Z, Gong L, Xu D,

Huang H, Jiang X, Pu Z, Yin Y and Zou J: p53/E2F7 axis promotes

temozolomide chemoresistance in glioblastoma multiforme. BMC

Cancer. 24(317)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Perrault EN, Shireman JM, Ali ES, Lin P,

Preddy I, Park C, Budhiraja S, Baisiwala S, Dixit K, James CD, et

al: Ribonucleotide reductase regulatory subunit M2 drives

glioblastoma TMZ resistance through modulation of dNTP production.

Sci Adv. 9(eade7236)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Pokorny JL, Calligaris D, Gupta SK,

Iyekegbe DO Jr, Mueller D, Bakken KK, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA,

Evans DL, Lou Z, et al: The efficacy of the wee1 inhibitor MK-1775

combined with temozolomide is limited by heterogeneous distribution

across the Blood-brain barrier in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res.

21:1916–1924. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Hussain SF, Yang D, Suki D, Aldape K,

Grimm E and Heimberger AB: The role of human glioma-infiltrating

microglia/macrophages in mediating antitumor immune responses.

Neuro Oncol. 8:261–279. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Quail DF and Joyce JA: The

microenvironmental landscape of brain tumors. Cancer Cell.

31:326–341. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Deng R, Qin J, Wang L, Li H, Wen N, Qin K,

Dong J, Wu J, Zhu D and Sun X: Energy metabolism-related GLUD1

contributes to favorable clinical outcomes of IDH-mutant glioma.

BMC Neurol. 24(344)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Familiari P, Lapolla P, Picotti V,

Palmieri M, Pesce A, Carosi G, Relucenti M, Nottola S, Gianno F,

Minasi S, et al: Role of 1p/19q codeletion in diffuse Low-grade

glioma tumour prognosis. Anticancer Res. 43:2659–2670.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Mansouri A, Hachem LD, Mansouri S, Nassiri

F, Laperriere NJ, Xia D, Lindeman NI, Wen PY, Chakravarti A, Mehta

MP, et al: MGMT promoter methylation status testing to guide

therapy for glioblastoma: Refining the approach based on emerging

evidence and current challenges. Neuro Oncol. 21:167–178.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|