Introduction

The incidence of cancer-associated thromboembolism

(CAT) depends on the type of cancer and is relatively high in

gynecological cancers (1,2). CAT complications are associated with

worse prognosis in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC)

(3,4). The prevalence of pretreatment CAT in

patients with EOC ranges from 10.4 to 26.4%, and many cases are

asymptomatic (4-6).

As untreated CAT can lead to life-threatening conditions, early

detection and treatment are essential for the comprehensive care of

patients with EOC.

D-dimer testing has been recommended as a

cost-effective and rapid screening tool for CAT in EOC (7,8);

however, D-dimer levels reflect a variety of conditions, including

inflammation caused by cancer cells and cancer treatments such as

surgery and chemotherapy (9-11).

In addition, cancer cells and EOC treatment may create an

environment for recurrent inflammation, where the level of

inflammation is influenced by the histological subtype and

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage

(12-14).

This condition can affect the effectiveness of D-dimer as a

screening method (15,16).

Clear cell carcinoma (CCC) and high-grade serous

carcinoma (HGSC) are two histological subtypes of ovarian cancer

that exhibit several differences in biological and clinical

characteristics. CCC is more common in Asia than in Western

countries, often detected in earlier stages, and has a

platinum-resistant nature (17).

In contrast, HGSC is the most common histological type, frequently

discovered at an advanced stage, and is sensitive to platinum

(18). Although HGSC is often

complicated with CAT, CCC exhibits the highest complication rate

among all histological subtypes (3-6).

In CCC, CAT formation is caused by hypercoagulation due to

overexpression of tissue factor (TF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6)

(19,20). CAT formation in HGSC is naturally

related to hypercoagulation, but it may also be associated with

dehydration and inflammation due to massive ascites and

malnutrition because HGSC is usually discovered at a more advanced

stage than CCC (21). Thus, the

tumor microenvironment and status of patients with CCC differ from

those of patients with HGSC.

Considering these distinct characteristics, the

diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers for CAT may differ between

histolo-gical subtypes such as CCC and HGSC. However, this

possibility has not been systematically evaluated. If D-dimer does

not prove effective as a biomarker for CAT, a screening test for

CAT detection is required. Therefore, we aimed to examine the

effectiveness of CAT screening in patients with CCC compared with

HGSC to develop a new system for CAT detection.

Materials and methods

Patients and blood samples

Patients diagnosed with CCC or HGSC who underwent

primary surgery at our hospital between January 2009 and December

2023 were identified. Clinical data were retrospectively collected

from medical records. Patients with acute infections at the initial

visit were excluded because of strong inflammatory responses.

Additionally, patients with a history of thrombosis or

anticoagulation therapy at the initial visit, those with other

cancers, and those without medical records were excluded. This

study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Defense

Medical College, Tokorozawa, Japan (No4933). Written informed

consent for all participation was obtained before the

treatment.

To identify the risk factors for CAT in CCC and

HGSC, the following variables were assessed: age at diagnosis, body

mass index, cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, the

World Health Organization Performance Status Scale (22), and 2014 FIGO (23). Additional factors included the

histological type diagnosed according to the 2020 WHO Health

Organization criteria (24), tumor

size measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) before primary

treatment, and the presence of ascites, which was assessed

intraoperatively or through preoperative percutaneous abdominal

puncture. Cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities included

previous or concurrent ischemic stroke, peripheral arterial

disease, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus,

and hyperlipidemia.

Peripheral blood samples were obtained during the

initial visit. Data on white blood cell differential counts and

platelet, hemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), albumin, D-dimer,

fibrinogen, and carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA 125) levels were

retrospectively obtained from medical records. D-dimer was measured

using a latex coagulation reaction by sensitization with an

anti-D-dimer mouse monoclonal antibody, and turbidity was assessed

using a spectrophotometer (CN-6500; SYSMEX, Hyogo, Japan). The

cutoff value for D-dimer was set at 1.0 µg/l. In addition, we

calculated the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), defined as the

absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count,

and the platelet-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), defined as the absolute

platelet count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count, as

biomarkers of inflammation (25).

CAT evaluation protocol

In our study, CAT was defined as CAT that developed

before primary treatment. CAT was classified as venous

thromboembolisms, including pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein

thrombosis (DVT). All patients underwent computed tomography before

the primary treatment to detect CAT. If patients had symptoms

suggestive of CAT, such as lower extremity edema, chest pain, and

dyspnea, we performed additional examinations, including

ultrasonography, MRI, and angiography.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using JMP

Pro 14 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Chi-square

tests and Fisher's exact tests were used to compare clinical and

pathological characteristics between patients with and without CAT.

In addition, the incidence and risk factors for CAT in patients

with CCC and HGSC were examined. Univariate and multivariate

analyses were performed using logistic regression analysis.

Serologic and hematologic biomarkers were compared using the Mann

Whitney U test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were

used to predict CAT development. The Youden index (sensitivity +

specificity-1) was calculated, and the cutoff value corresponding

to the highest Youden index was used as the optimal cutoff value.

Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics

In total, we analyzed the data of 79 patients with

CCC and 123 with HGSC. Of them, 20 patients with CCC (25.3%) and 15

with HGSC (12.2%) developed CAT (P=0.022). The CCC group included 6

patients (7.6%) with DVT, 6 (7.6%) with PE, and 8 (10.1%) with PE

and DVT, whereas the HGSC group included 8 patients (6.5%) with DVT

and 7 (5.7%) with PE.

Table I presents

the clinical characteristics of patients with and without CAT. In

the CCC group, patients with CAT were diagnosed at a more advanced

FIGO stage (P=0.004) and had larger tumors (P=0.030) and massive

ascites (P=0.013). However, no significant differences in CAT

complications were observed in the HGSC group. Table II summarizes the univariate and

multivariate analyses of risk factors for CAT in the CCC group.

Univariate analysis identified advanced stage [odds ratio (OR)

4.40, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.51 12.8, P=0.007], larger

tumor size (OR 4.46, 95% CI 1.18 16.9, P=0.028), and increased

ascites volume (OR 14.5, 95% CI 1.51 139.0, P=0.020) as significant

risk factors for CAT. Multivariate analysis confirmed that an

advanced disease stage (OR 3.28, 95% CI 1.04 10.3, P=0.042) was an

independent risk factor for CAT. Risk factors for CAT in the HGSC

group could not be determined.

| Table ICharacteristics of patients with CCC

and HGSC with or without CAT. |

Table I

Characteristics of patients with CCC

and HGSC with or without CAT.

| | Patients with

CCC | Patients with

HGSC |

|---|

| Variables | CAT (+), n (%)

(n=20) | CAT (-), n (%)

(n=59) | P-value | CAT (+), n (%)

(n=15) | CAT (-), n (%)

(n=108) | P-value |

|---|

| Age at diagnosis,

years | | | 0.588 | | | 0.584 |

|

≥65 | 13 (65.0) | 42 (71.2) | | 5 (33.3) | 46 (42.6) | |

|

<65 | 7 (35.0) | 17 (28.8) | | 10 (66.6) | 62 (57.4) | |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | | | 0.999 | | | 0.739 |

|

≥25 | 3 (15.0) | 9 (15.3) | | 4 (26.7) | 23 (21.3) | |

|

<25 | 17 (85.0) | 50 (84.7) | | 11 (73.3) | 85 (78.7) | |

| Cardiovascular risk

factors and comorbidities | | | 0.490 | | | 0.720 |

|

Yes | 3 (15.0) | 7 (11.9) | | 3 (20.0) | 18 (16.7) | |

|

No | 17 (85.0) | 52 (88.1) | | 12 (80.0) | 90 (83.3) | |

| FIGO stage | | | 0.004 | | | 0.054 |

|

I | 8 (40.0) | 44 (74.6) | | 3 (20.0) | 18 (16.7) | |

|

II | 2 (10.0) | 7 (11.9) | | 7 (46.7) | 73 (67.6) | |

|

III | 9 (45.0) | 8 (13.5) | | 3 (20.0) | 9 (8.3) | |

|

IV | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | | 2 (13.3) | 8 (7.4) | |

| Tumor size, cm | | | 0.030 | | | 0.342 |

|

≥10 | 17 (85.0) | 33 (55.9) | | 5 (33.3) | 24 (22.2) | |

|

<10 | 3 (15.0) | 26 (44.1) | | 10 (66.7) | 84 (77.8) | |

| Ascites, ml | | | 0.013 | | | 0.382 |

|

≥1,000 | 4 (20.0) | 1 (1.7) | | 9 (60.0) | 61 (56.5) | |

|

<1,000 | 16 (80.0) | 58 (98.3) | | 6 (40.0) | 47 (43.5) | |

| Table IIUnivariate and multivariate analysis

for the incidence of cancer-associated thromboembolism in clear

cell carcinoma. |

Table II

Univariate and multivariate analysis

for the incidence of cancer-associated thromboembolism in clear

cell carcinoma.

| | Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age at diagnosis

(≥65 vs. <65 years) | 1.33 | 0.45-3.91 | 0.588 | | | |

| Body mass index

(≥25 vs. <25 kg/m2) | 0.98 | 0.24-4.05 | >0.999 | | | |

| Cardiovascular risk

factors and comorbidities (yes vs. no) | 1.31 | 0.30-5.64 | 0.716 | | | |

| FIGO stage (II-IV

vs. I) | 4.40 | 1.51-12.76 | 0.007 | 3.28 | 1.04-10.32 | 0.042 |

| Tumor size (≥10 vs.

<10 cm) | 4.46 | 1.18-16.88 | 0.028 | 3.22 | 0.80-12.87 | 0.098 |

| Ascites (≥1,000 vs.

<1,000 ml) | 14.48 | 1.51-139.02 | 0.020 | 6.61 | 0.63-70.01 | 0.116 |

Biomarker analysis

Comparison of serological and hematological

biomarkers between patients with and without CAT is presented in

Table III. In the CCC group,

significant differences were observed in NLR, PLR, hemoglobin,

albumin, CRP, D-dimer, CA125, and CA19-9 levels. Conversely, in the

HGSC group, only D-dimer levels were significantly different.

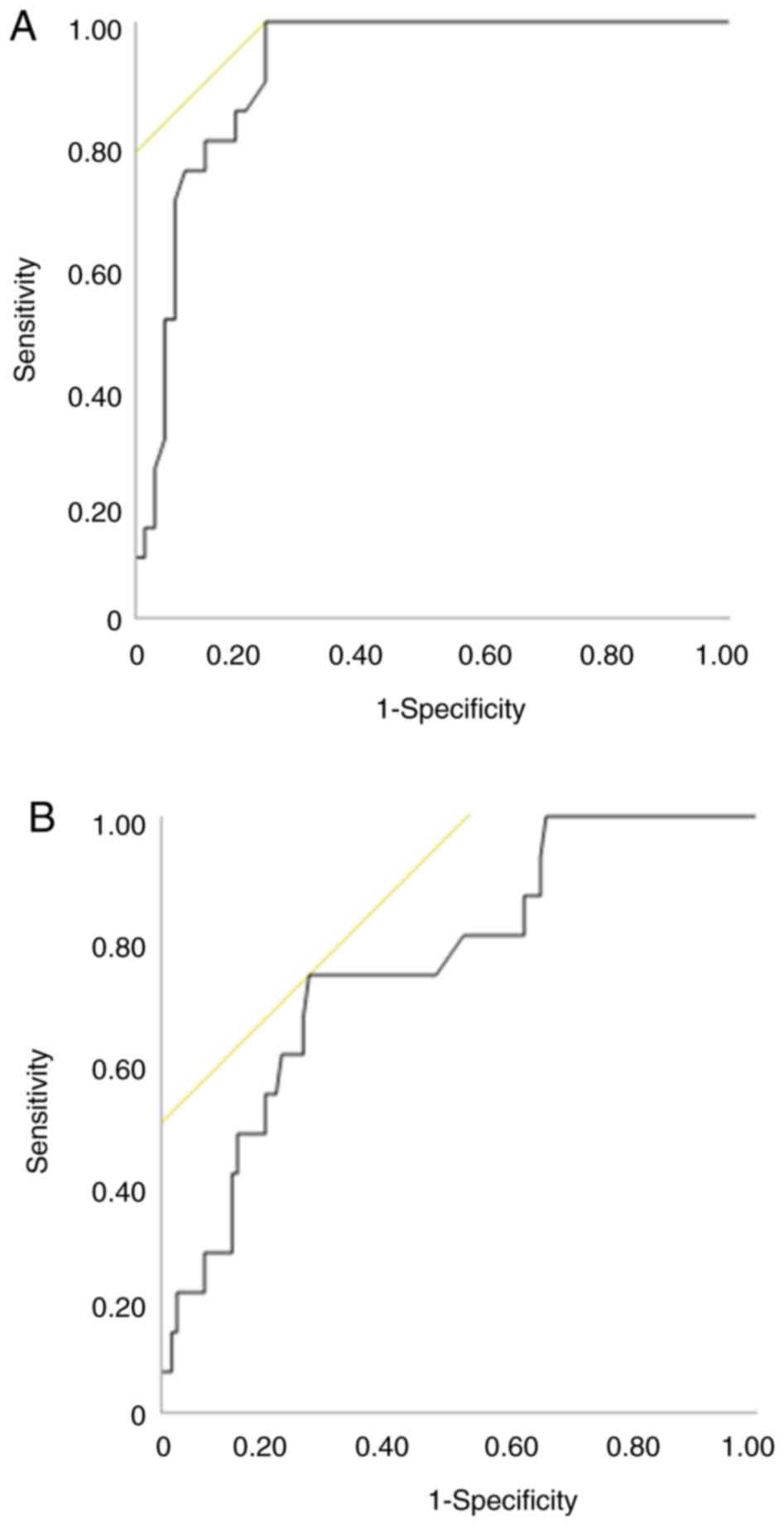

D-dimer had the highest area under the curve (AUC) (0.92,

P<0.001) in the CCC group and highest AUC (0.75, P=0.002) in the

HGSC group; the AUC in the HGSC group was lower than that in the

CCC group (Fig. 1). The cutoff

value of D-dimer as a predictor of CAT was 1.5 µg/ml in CCC and 5.8

µg/ml in HGSC.

| Table IIIComparison of serologic and

hematologic biomarkers in patients with CCC and HGSC before primary

treatment. |

Table III

Comparison of serologic and

hematologic biomarkers in patients with CCC and HGSC before primary

treatment.

| | CCC | HGSC |

|---|

| Variable | CAT (+) (n=20) | CAT (-) (n=59) | P-value | AUC | CAT (+) (n=15) | CAT (-)

(n=108) | P-value | AUC |

|---|

| Neutrophil count,

109/l | 5.21

(3.05-27.28) | 4.82

(1.56-8.28) | 0.120 | 0.62 | 4.55

(1.69-12.11) | 5.41

(1.94-13.41) | 0.120 | 0.62 |

| Lymphocyte count,

109/l | 1.21

(0.49-2.20) | 1.47

(0.73-3.03) | 0.111 | 0.62 | 1.21

(0.42-1.92) | 1.25

(0.37-4.27) | 0.444 | 0.56 |

| NLR | 3.89

(2.37-25.77) | 3.15

(1.02-7.09) | 0.005 | 0.71 | 3.62

(1.13-22.73) | 4.18

(1.22-24.73) | 0.716 | 0.47 |

| Platelet count,

109/l | 32.65

(22.70-69.80) | 27.6

(10.50-57.50) | 0.099 | 0.62 | 28.70

(10.10-61.30) | 32.60

(16.00-69.20) | 0.152 | 0.61 |

| PLR | 281.50

(116.06-659.48) | 182.6

(74.12-576.51) | 0.015 | 0.68 | 202.02

(78.84-1293.89) | 265.48

(61.33-1217.98) | 0.599 | 0.46 |

| Hemoglobin,

g/l | 10.70

(8.20-13.70) | 12.30

(6.80-14.40) | 0.008 | 0.70 | 12.40

(7.50-15.30) | 12.70

(8.70-16.70) | 0.948 | 0.49 |

| Albumin, g/l | 3.50

(2.10-4.70) | 4.00

(2.60-5.10) | 0.002 | 0.73 | 3.30

(2.00-4.40) | 3.10

(2.00-4.90) | 0.278 | 0.59 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 2.25

(0.30-19.70) | 0.30

(0.30-8.70) | 0.004 | 0.71 | 1.70

(0.30-11.50) | 1.50

(0.14-27.10) | 0.651 | 0.54 |

| D-dimer, µg/l | 8.35

(1.60-28.10) | 0.70

(0.10-25.30) | <0.001 | 0.91 | 8.00

(2.00-27.50) | 3.50

(0.10-27.30) | 0.002 | 0.75 |

| Fibrinogen,

mg/dl | 454.50

(163.00-719.00) | 372.50 (174.00-847.

00) | 0.725 | 0.53 | 368.00

(217.00-744.00) | 412.00

(196.00-2,565.00) | 0.749 | 0.53 |

| CA125, U/ml | 400.30

(13.00-1,423.00) | 44.10

(5.40-2,206.00) | <0.001 | 0.80 | 1,367.10

(5.20-32,547.00) | 592.20

(6.60-15,665.00) | 0.243 | 0.59 |

Diagnostic performance of D-dimer

Tables IV and

V show the sensitivity,

specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative

predictive value (NPV) of D-dimer in predicting CAT in the CCC and

HGSC groups. the AUC for predicting CAT was 0.75 in HGSC group, and

according to the cutoff values corresponding to the highest Youden

index, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 73.3, 75.0,

28.9, and 95.3%, respectively. In contrast, the AUC, sensitivity,

specificity, PPV, and NPV for predicting CAT in the CCC group were

0.91, 100, 83.0, 50.0, and 100%, respectively. The combination of

FIGO stage I and D-dimer ≥1.5 µg/l improved the predictive ability

to an AUC of 0.97 in the CCC group.

| Table IVDiagnostic performance of D-dimer

cutoffs and FIGO stage for detecting cancer-associated

thromboembolism in clear cell carcinoma before treatment. |

Table IV

Diagnostic performance of D-dimer

cutoffs and FIGO stage for detecting cancer-associated

thromboembolism in clear cell carcinoma before treatment.

| Marker

combination | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % | AUC |

|---|

| D-dimer (1.00

µg/ml)a | 100.0 | 61.0 | 46.5 | 100.0 | 0.91 |

| D-dimer (1.50

µg/ml)b | 100.0 | 78.0 | 60.6 | 100.0 | 0.91 |

|

Plus FIGO

stage I | 100.0 | 88.6 | 61.5 | 100.0 | 0.97 |

|

Plus FIGO

stage II-IV | 100.0 | 60.0 | 66.7 | 100.0 | 0.81 |

| Table VDiagnostic performance of D-dimer

cutoffs for detecting cancer-associated thromboembolism in

high-grade serous carcinoma before treatment. |

Table V

Diagnostic performance of D-dimer

cutoffs for detecting cancer-associated thromboembolism in

high-grade serous carcinoma before treatment.

| Marker | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | PPV, % | NPV, % | AUC |

|---|

| D-dimer (1.00

µg/ml)a | 100.0 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 100.0 | 0.75 |

| D-dimer (5.80

µg/ml)b | 73.3 | 75.0 | 28.9 | 95.3 | 0.75 |

Discussion

Our study showed that CCC was more frequently

complicated by CAT. Advanced stage was the only risk factor

identified for CAT in the CCC group, whereas no significant risk

factors were found in the HGSC group. Furthermore, D-dimer showed

the highest AUC for detecting CAT in both the CCC and HGSC groups,

with the CCC group having a higher AUC than the HGSC group.

Additionally, a model combining D-dimer levels and early-stage

disease exhibited improved sensitivity and specificity for

detecting CAT.

Our results indicated that CAT incidence before

treatment in patients with CCC and those with HGSC fell within the

range reported in previous studies, ranging from 13.4 to 33.1% in

CCC (3,4,6,26)

and 11.8 to 24.0% in HGSC (5,6,26).

Patients with EOC and CAT do not usually present with symptoms

(5), which were consistent with

the findings of our study. Therefore, imaging studies such as CT

angiography or ultrasound sonography are necessary for thrombosis

screening.

Some risk factors for CAT have been reported,

including age, massive ascites, FIGO stage, and cardiovascular

disease (4,6,26,27).

Our analysis revealed that advanced FIGO stage was an independent

risk factor for CAT formation in the CCC group. In contrast, no

significant risk factors were identified in the HGSC group.

Therefore, particular attention is needed for patients with CCC

experiencing risk factors and for all patients with HGSC.

Although we attempted to identify new biomarkers,

the D-dimer test remained the most useful tool for detecting CAT in

both the CCC and HGSC groups, consistent with previous findings

(4,15,16).

Notably, the D-dimer test was more effective in detecting CAT in

patients with CCC than in those with HGSC. We assumed that these

results were due to the different characteristics of CCC and HGSC.

Overexpression of TF and IL-6 plays a pivotal role in CAT

development in CCC (14,19,27).

TF, Factor III, initiates the extrinsic coagulation pathway by

binding to Factor VIIa and Factor Xa, leading to thrombin

generation. Meanwhile, IL-6 is a proinflammatory cytokine that

promotes coagulation by increasing TF expression and fibrinogen

synthesis (28). In HGSC, while

these factors also contribute to CAT, CAT is strongly associated

with ascites, tumor pressure on the veins, and dehydration

(6). Our reports suggest that a

strategy for detecting CAT can be established according to the

histological subtypes. The constructed predictive model, combining

disease stage and D-dimer levels, may be useful for detecting CAT

in CCC.

The limitations of our study included the

retrospective design, single-institution analysis, and small sample

size. Further studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to

confirm the clinical significance of the association between CCC

and CAT.

In conclusion, advanced stage is an independent risk

factor for the development of CAT in CCC. D-dimer is an excellent

screening tool for CAT in CCC, in particular when combined with

FIGO stage; however, it is less reliable in HGSC, suggesting a need

for histology-specific screening strategies. Further studies are

required for preoperative diagnosis using imaging, tumor markers,

and molecular biological methods for early detection of CAT.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TI, MM and MT contributed to the conception and

design of the study. Material preparation, and data collection and

analysis were carried out by TI, NK, JS and TH. TI, MM, RT, SN, JS,

TH, YO, KK, HS, KO, YH and MT contributed to the interpretation of

the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TI. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of the National Defense Medical College, Tokorozawa,

Saitama, Japan on January 20, 2024 (confirmation no. 4933). All

patient records and information were completely anonymized prior to

analysis to prevent the disclosure of their identities. Before the

treatment, written informed consent was obtained from all patients

with ovarian cancer who underwent surgery.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gerotziafas GT, Taher A, Abdel-Razeq H,

AboElnazar E, Spyropoulos AC, El Shemmari S, Larsen AK and Elalamy

I: COMPASS-CAT Working Group. A predictive score for thrombosis

associated with breast, colorectal, lung, or ovarian cancer: The

prospective compass-cancer-associated thrombosis study. Oncologist.

22:1222–1231. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chandra A, Pius C, Nabeel M, Nair M,

Vishwanatha JK, Ahmad S and Basha R: Ovarian cancer: Current status

and strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med.

8:7018–7031. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Matsuura Y, Robertson G, Marsden DE, Kim

SN, Gebski V and Hacker NF: Thromboembolic complications in

patients with clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol.

104:406–410. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhang W, Liu X, Cheng H, Yang Z and Zhang

G: Risk factors and treatment of venous thromboembolism in

perioperative patients with ovarian cancer in China. Medicine

(Baltimore). 97(e11754)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Satoh T, Oki A, Uno K, Sakurai M, Ochi H,

Okada S, Minami R, Matsumoto K, Tanaka YO, Tsunoda H, et al: High

incidence of silent venous thromboembolism before treatment in

ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 97:1053–1057. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tasaka N, Minaguchi T, Hosokawa Y, Takao

W, Itagaki H, Nishida K, Akiyama A, Shikama A, Ochi H and Satoh T:

Prevalence of venous thromboembolism at pretreatment screening and

associated risk factors in 2086 patients with gynecological cancer.

J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 46:765–773. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kawaguchi R, Furukawa N and Kobayashi H:

Cut-off value of D-dimer for prediction of deep venous thrombosis

before treatment in ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 23:98–102.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Bakhru A: Effect of ovarian tumor

characteristics on venous thromboembolic risk. J Gynecol Oncol.

24:52–58. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tang N, Pan Y, Xu C and Li D:

Characteristics of emergency patients with markedly elevated

D-dimer levels. Sci Rep. 10(7784)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Beer JH, Haeberli A, Vogt A, Woodtli K,

Henkel E, Furrer T and Fey MF: Coagulation markers predict survival

in cancer patients. Thromb Haemost. 88:745–749. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Shorr AF, Thomas SJ, Alkins SA,

Fitzpatrick TM and Ling GS: D-dimer correlates with proinflammatory

cytokine levels and outcomes in critically ill patients. Chest.

121:1262–1268. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Farolfi A, Petrone M, Scarpi E, Gallà V,

Greco F, Casanova C, Longo L, Cormio G, Orditura M, Bologna A, et

al: Inflammatory indexes as prognostic and predictive factors in

ovarian cancer treated with chemotherapy alone or together with

bevacizumab. A multicenter, retrospective analysis by the MITO

group (MITO 24). Target Oncol. 13:469–479. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Shi J, Huo R, Li N, Li H, Zhai T, Li H,

Shen B, Ye J, Fu R and Di W: CYR61, a potential biomarker of tumor

inflammatory response in epithelial ovarian cancer microenvironment

of tumor progress. BMC Cancer. 19(1140)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wang Y, Zong X, Mitra S, Mitra AK, Matei D

and Nephew KP: IL-6 mediates platinum-induced enrichment of ovarian

cancer stem cells. JCI Insight. 3(e122360)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Shim H, Lee YJ, Kim JH, Lim MC, Lee DE,

Park SY and Kong SY: Preoperative laboratory parameters associated

with deep vein thrombosis in patients with ovarian cancer:

Retrospective analysis of 3,147 patients in a single institute. J

Gynecol Oncol. 35(e38)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wu J, Fu Z, Liu G, Xu P, Xu J and Jia X:

Clinical significance of plasma D-dimer in ovarian cancer: A

meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 96(e7062)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Takano M, Goto T, Kato M, Sasaki N,

Miyamoto M and Furuya K: Short response duration even in responders

to chemotherapy using conventional cytotoxic agents in recurrent or

refractory clear cell carcinomas of the ovary. Int J Clin Oncol.

18:556–557. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Rauh-Hain JA, Melamed A, Wright A, Gockley

A, Clemmer JT, Schorge JO, Del Carmen MG and Keating NL: Overall

survival following neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs primary

cytoreductive surgery in women with epithelial ovarian cancer:

Analysis of the national cancer database. JAMA Oncol. 3:76–82.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Matsuo K, Hasegawa K, Yoshino K, Murakami

R, Hisamatsu T, Stone RL, Previs RA, Hansen JM, Ikeda Y, Miyara A,

et al: Venous thromboembolism, interleukin-6 and survival outcomes

in patients with advanced ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Eur J

Cancer. 51:1978–1988. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Sakurai M, Matsumoto K, Gosho M, Sakata A,

Hosokawa Y, Tenjimbayashi Y, Katoh T, Shikama A, Komiya H,

Michikami H, et al: Expression of tissue factor in epithelial

ovarian carcinoma is involved in the development of venous

thromboembolism. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 27:37–43. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Gunderson CC, Thomas ED, Slaughter KN,

Farrell R, Ding K, Farris RE, Lauer JK, Perry LJ, McMeekin DS and

Moore KN: The survival detriment of venous thromboembolism with

epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 134:73–77.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Prat J: FIGO Committee on Gynecologic

Oncology. FIGO's staging classification for cancer of the ovary,

fallopian tube, and peritoneum: Abridged republication. J Gynecol

Oncol. 26:87–89. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

World Health Organization Classification

of Tumours Editorial Board: WHO classification of tumours 5th

edition female genital tumours. International Agency for Research

on Cancer, Lyon, pp34-167, 2020.

|

|

25

|

Kuplay H, Erdoğan SB, Bastopcu M,

Arslanhan G, Baykan DB and Orhan G: The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio

and the platelet-lymphocyte ratio correlate with thrombus burden in

deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord.

8:360–364. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liang S, Tang W, Ye S, Xiang L, Wu X and

Yang H: Incidence and risk factors of preoperative venous

thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism in patients with ovarian

cancer. Thromb Res. 190:129–134. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Claussen C, Rausch AV, Lezius S,

Amirkhosravi A, Davila M, Francis JL, Hisada YM, Mackman N,

Bokemeyer C, Schmalfeldt B, et al: Microvesicle-associated tissue

factor procoagulant activity for the preoperative diagnosis of

ovarian cancer. Thromb Res. 141:39–48. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Kerr R, Stirling D and Ludlam CA:

Interleukin 6 and haemostasis. Br J Haematol. 115:3–12.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|