Introduction

The standard of care for advanced non-small cell

lung cancer (NSCLC) is systemic therapy. Although cytotoxic agents

conferred an improved survival for NSCLC patients with a good

performance status (PS) (1), the

effectiveness was limited. In this context, molecular targeted

therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been

developed to improve the prognosis of patients with NSCLC. The

effectiveness of ICIs for advanced NSCLC depends on tumor

programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. It has been shown

that the survival benefit of ICI monotherapy for pre-treated

non-squamous NSCLC (2) and

chemoimmunotherapy for untreated NSCLC (3) was greater in those with higher PD-L1

expression levels. Thus, tumor PD-L1 expression is considered an

indicator of the efficacy of ICI therapy for NSCLC (2).

Alternatively, thyroid transcription factor-1

(TTF-1) expression may be another biomarker for the prognosis of

NSCLC. TTF-1 is a transcription factor essential for the

development and differentiation of the lung and thyroid. In animal

models, its inactivation results in severe malformations (4). Gene amplification of TTF-1 has been

demonstrated to promote tumorigenesis in terminal respiratory unit

(TRU)-type lung adenocarcinomas (5). Conversely, the loss of TTF-1

transcriptional activity due to inactivating mutations, such as

frameshift or nonsense mutations, or promoter methylation has been

implicated in the pathogenesis of invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas

(6) and non-TRU-type lung

adenocarcinomas (7). Moreover,

studies employing genetically engineered mouse models have

demonstrated the inactivation of TTF-1 promotes the development of

mucinous adenocarcinomas and induces a phenotypic shift toward

gastric lineage differentiation (8,9).

Given these dual roles of TTF-1 in tumorigenesis,

its protein expression has been investigated as a prognostic marker

in NSCLC. It is reported that TTF-1 expression is associated with

survival after surgery (10),

targeted therapy (11), cytotoxic

agents (12), and ICI therapy

(13-17).

However, multiple antibodies for TTF-1, including 8G7G3/1, SP141,

and SPT24, are available, and the optimal antibody for the

evaluation of TTF-1 expression is undetermined. Furthermore,

opposite findings have been reported concerning the association

between TTF-1 expression and survival after the initiation of the

ICI therapy (12,18,19).

Thus far, the relationship between TTF-1 expression and the

therapeutic efficacy of ICIs in NSCLC remains unclear, with

existing studies yielding inconsistent or inconclusive results.

Immunohistochemistry for TTF-1 and napsin A using a

cocktail antibody (ADC Cocktail antibody, code: KT-17004,

prediluted, Pathology Institute, Toyama, Japan) is employed in

clinical practice in Japan. Herein, we analyzed the association

between TTF-1 expression assessed using a cocktail antibody and

survival after ICI therapy.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

We retrospectively analyzed the data of patients

with NSCLC. Inclusion criteria were specified as follows: i)

Patients who were diagnosed as having non-squamous NSCLC between

January 2019 and December 2023 at Toyama University Hospital

(Toyama, Japan); ii) patients with inoperable diseases, including

advanced, locally advanced, and recurrent NSCLC; iii) patients who

received first-line treatment with ICI monotherapy or

chemoimmunotherapy (hereafter, ICI therapy); and iv) patients for

whom the data regarding TTF-1 expression were evaluated using a

cocktail antibody (TTF-1/napsin A). Exclusion criteria were

specified as follows: i) Patients with NSCLC showing EGFR mutations

and ALK rearrangements; ii) patients with adenosquamous cell

carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, or neuroendocrine carcinoma; and

iii) patients for whom important data were unavailable, including

PS or PD-L1 expression.

This study was conducted in accordance with The

Declaration of Helsinki and the Guideline of Ministry of Health,

Labor and Welfare and was approved by the Ethics Committee,

University of Toyama (approval no. R2020067). Because this study is

retrospective and noninvasive, written informed consent was not

required.

Clinical information

Clinical information was collected from medical

charts at the initiation of the treatment with ICI therapy,

including age, PS, smoking history, disease stage, tumor PD-L1

expression, TTF-1 expression, driver mutation, and treatment

history. PD-L1 expression testing was performed by a commercial

laboratory (BML INC., Tokyo, Japan) and evaluated using the 22C3

antibody. The expression of TTF-1 was evaluated using a cocktail

antibody (code: KT-17004, clone; SPT24/TMU-Ad02, prediluted,

Pathology Institute, Toyama, Japan). We performed

deparaffinization, antigen retrieval treatment, and endogenous

peroxidase blocking using a VENTANA BenchMark ULTRA system (F.

Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd. Basel, Switzerland) according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

The endpoints of the present study were

progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) from the

initiation of ICI therapy. PFS was calculated from the initiation

of ICI therapy to the date of RECIST progressive disease, clinical

progression, or death, whichever occurred first, and censored on

the day when none of these events was noted. OS was calculated from

the initiation of ICI therapy to the date of death and censored on

the day of the last visit without death. Kaplan-Meier curve of PFS

and OS was drawn, and the median (95% confidence interval, CI) was

estimated. PFS and OS were compared using the log-rank test.

Multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox progression

hazard model to analyze the association between TTF-1 expression

and survival, adjusting for potential prognostic factors such as

PS, histology, PD-L1 expression, driver mutation, and chemotherapy.

Fisher's exact test or Wilcoxon's rank sum test were used to

compare patient characteristics. All statistical analyses were

performed using JMP version 17.0.0 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2019 and December 2023, 218 patients

with advanced or recurrent NSCLC received first-line treatment with

ICI therapy. After excluding 79 patients with EGFR gene mutations

or ALK fusion gene positivity, 65 patients with squamous cell

carcinoma/adenosquamous carcinoma/sarcomatoid

carcinoma/neuroendocrine carcinoma, 20 patients with unknown

TTF-1/napsin A status, 4 patients with unknown PD-L1 status, and 1

patient with unknown PS, 49 patients were included in the

analysis.

The patient characteristics are summarized in

Table I. Among the 49 patients, 14

were negative for TTF-1, and 35 were positive. A higher proportion

of cases in the TTF-1-negative group exhibited PD-L1 TPS < 50%

than in the positive group. Among the patients with driver gene

mutations, there was 1 case of KRAS G12A, 4 cases of KRAS G12C, 1

case of KRAS G12D, 3 cases of KRAS G12V, and 1 case of MET exon 14

skipping mutation. The representative images of positive and

negative TTF-1 staining are shown in Fig. S1.

| Table ICharacteristics of patients with

negative and positive TTF-1 expression. |

Table I

Characteristics of patients with

negative and positive TTF-1 expression.

| | TTF-1 | |

|---|

| Characteristic | Negative | Positive | P-value |

|---|

| Median age, years

(range) | 72 (60-85) | 73 (46-89) | 0.894 |

| Sex, n (%) | | | |

|

Male | 11 (78.6%) | 26 (74.3%) | >0.999 |

|

Female | 3 (21.4%) | 9 (25.7%) | |

| PS, n (%) | | | |

|

0-1 | 11 (78.6%) | 29 (82.9%) | 0.702 |

|

≥2 | 3 (21.4%) | 6 (17.1%) | |

| Smoking history, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 12 (85.7%) | 32 (91.4%) | 0.616 |

|

No | 2 (14.3%) | 3 (8.6%) | |

| Histology, n (%) | | | |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 9 (64.3%) | 33 (94.3%) | 0.015 |

|

Other | 5 (35.7%) | 2 (5.7%) | |

| Driver mutation, n

(%) | | | |

|

Positive | 3 (21.4%) | 7 (20.0%) | >0.999 |

|

Negative/unknown | 11 (78.6%) | 28 (80.0%) | |

| PD-L1 TPS, n (%) | | | |

|

<50% | 12 (85.7%) | 16 (45.7%) | 0.013 |

|

≥50% | 2 (14.3%) | 19 (54.3%) | |

| Stage, n (%) | | | |

|

3B | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.802 |

|

4A | 4 (28.6%) | 9 (25.7%) | |

|

4B | 5 (35.7%) | 16 (45.7%) | |

|

Recurrence | 5 (35.7%) | 9 (25.7%) | |

| ILD, n (%) | | | |

|

Yes | 2 (14.3%) | 2 (5.7%) | 0.568 |

|

No | 12 (85.7%) | 33 (94.3%) | |

| Liver metastases, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 1 (7.1%) | 2 (5.7%) | >0.999 |

|

No | 13 (92.9%) | 33 (94.3%) | |

| Brain metastases, n

(%) | | | |

|

Yes | 2 (14.3%) | 9 (25.7%) | 0.475 |

|

No | 12 (85.7%) | 26 (74.3%) | |

| NLR, n (%) | | | |

|

<5 | 6 (42.9%) | 24 (68.6%) | 0.116 |

|

≥5 | 8 (57.1%) | 11 (31.4%) | |

| LDH, n (%) | | | |

|

<200

U/l | 5 (35.7%) | 21 (60.0%) | 0.205 |

|

≥200

U/l | 9 (64.3%) | 14 (40.0%) | |

| CRP, n (%) | | | |

|

<1.0

mg/dl | 7 (50.0%) | 23 (65.7%) | 0.346 |

|

≥1.0

mg/dl | 7 (50.0%) | 12 (34.3%) | |

| Treatment, n

(%) | | | |

|

Chemotherapy

+ ICI | 10 (71.4%) | 17 (48.6%) | 0.207 |

|

ICI | 4 (28.6%) | 18 (51.4%) | |

Survival time

Tables II and

III show the results of a

multivariate analysis adjusted for PS, histology, PD-L1 expression,

presence of genetic abnormalities, and the use of chemotherapy. The

relationship was examined between TTF-1 expression and both PFS and

OS. TTF-1 positivity was significantly associated with a decreased

risk of disease progression, independent of these factors; however,

no significant association was observed with a decreased risk of

death.

| Table IICox proportional hazard model for the

risk of progression. |

Table II

Cox proportional hazard model for the

risk of progression.

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| PS | | | |

|

0-1 | 0.83 | 0.27-2.50 | 0.735 |

|

≥2 | 1.00 | | |

| Histology | | | |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 1.27 | 0.43-3.76 | 0.666 |

|

Other | 1.00 | | |

| PD-L1 TPS | | | |

|

≥50% | 1.28 | 0.47-3.47 | 0.633 |

|

<50% | 1.00 | | |

| Driver

mutation | | | |

|

Positive | 0.82 | 0.32-2.14 | 0.692 |

|

Negative/unknown | 1.00 | | |

| TTF-1 | | | |

|

Positive | 0.18 | 0.06-0.54 | 0.002 |

|

Negative | 1.00 | | |

| Treatment | | | |

|

Chemotherapy

+ ICI | 1.34 | 0.53-3.43 | 0.537 |

|

ICI | 1.00 | | |

| Table IIICox proportional hazard model for the

risk of death. |

Table III

Cox proportional hazard model for the

risk of death.

| Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| PS | | | |

|

0-1 | 0.61 | 0.16-2.41 | 0.485 |

|

≥2 | 1.00 | | |

| Histology | | | |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 0.29 | 0.08-1.11 | 0.070 |

|

Other | 1.00 | | |

| PD-L1 TPS | | | |

|

≥50% | 1.15 | 0.36-3.65 | 0.818 |

|

<50% | 1.00 | | |

| Driver

mutation | | | |

|

Positive | 1.10 | 0.30-3.98 | 0.884 |

|

Negative/unknown | 1.00 | | |

| TTF-1 | | | |

|

Positive | 0.67 | 0.15-2.97 | 0.601 |

|

Negative | 1.00 | | |

| Treatment | | | |

|

Chemotherapy

+ ICI | 0.81 | 0.29-2.29 | 0.694 |

|

ICI | 1.00 | | |

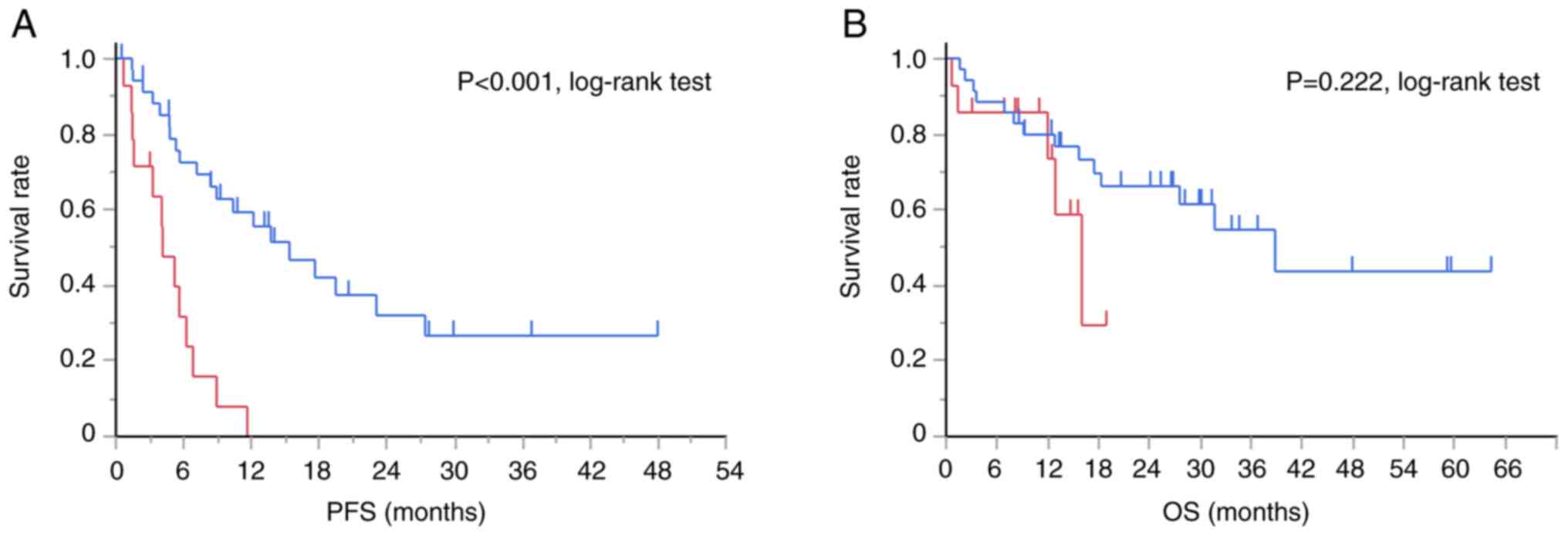

Fig. 1 presents the

Kaplan-Meier curves for PFS and OS in the TTF-1-positive and

-negative groups. The TTF-1-positive group demonstrated

significantly longer PFS (median PFS, 15.4 months vs. 4.1 months,

P<0.001, log-rank test) than the negative group, but not

significantly longer OS (median OS, 38.8 months vs. 16.0 months).

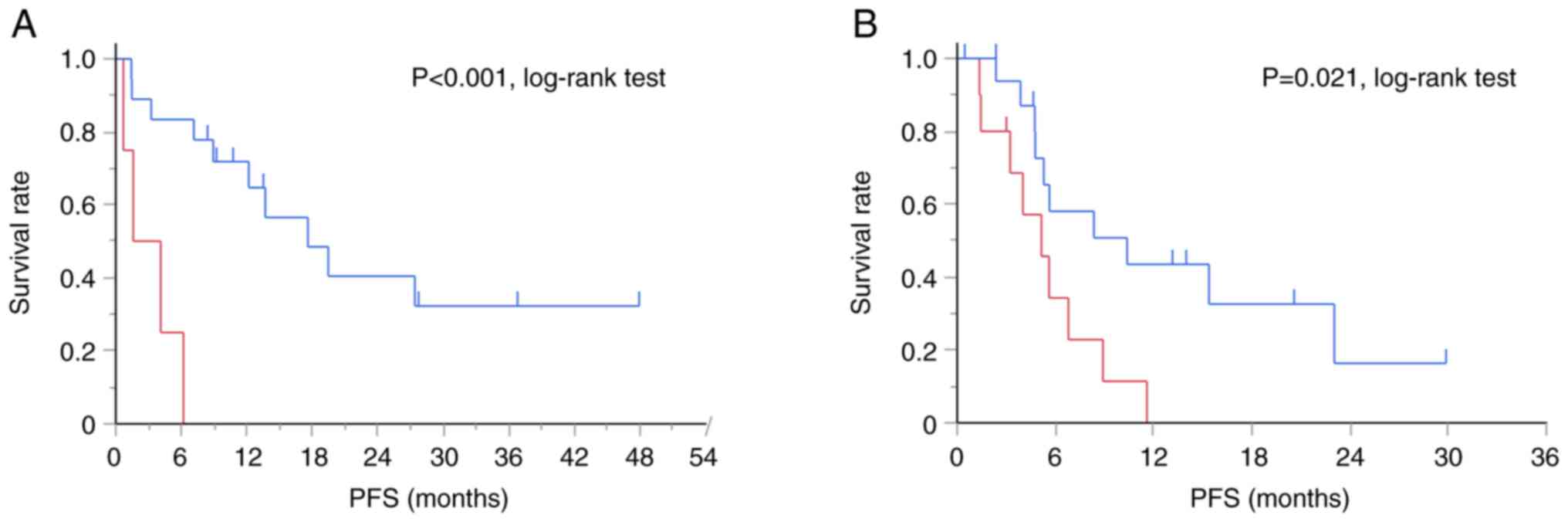

When patients were stratified by chemotherapy use, the

TTF-1-positive group exhibited significantly longer PFS than the

negative group in both the ICI monotherapy group (median PFS, 17.6

months vs. 2.9 months, P<0.001, log-rank test) and

chemoimmunotherapy group (median PFS, 10.4 months vs. 5.2 months,

P=0.021, log-rank test) (Fig.

2).

Discussion

TTF-1 is associated with the survival of NSCLC

patients as a prognostic factor. Recently, the relationship between

TTF-1 expression and survival after the initiation of ICI therapy

has garnered increasing interest, particularly in optimizing

treatment strategies for the poor prognostic population

characterized by negative TTF-1 expression (18). However, there are inconsistent

reports concerning the association between TTF-1 expression and

survival. TTF-1 has previously been analyzed using anti-TTF-1

antibody clone 8G7G3/1, SPT24, and SP141 (12,13,15,17-19).

The anti-TTF-1 antibody clone SPT24 is more sensitive but less

specific than 8G7G3/1(20). The

present study suggests that TTF-1 expression evaluated using a

cocktail antibody using SPT24/TMU-Ad02 antibody is associated with

PFS after ICI therapy.

TTF-1 is expressed on type II pulmonary epithelial

cells and club cells, contributing to lung development and the

homeostasis of surfactant protein. TTF-1 induces the expression of

myosin-binding protein H, which results in decreased cancer

invasion and metastasis (5).

Furthermore, several studies have proposed that TTF-1 may also

exert tumor-suppressive functions by maintaining alveolar

epithelial lineage identity and preventing dedifferentiation. The

loss of TTF-1 activity has been implicated in the development of

invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma and other non-TRU-type

adenocarcinomas (6,7). Thus, the favorable prognosis in

patients with TTF-1-positive tumors observed in our study could be

partially attributable to its tumor-suppressive function.

Conversely, in TTF-1-negative lung adenocarcinoma,

the inactivating mutation of kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

(KEAP1) is enriched (21), which

results in the overexpression of nuclear factor-like 2 (Nrf2), a

master regulator of the antioxidant response. Nrf2 is associated

with poor prognosis in several cancers, including lung cancer

(21). Furthermore, the proportion

of PD-L1 positive tumors may be lower in TTF-1-negative NSCLC

(14,15), which was observed in the present

study. Tumor PD-L1 expression is induced either by oncogene

signaling or interferon γ secreted by T lymphocytes (22). Thus, it is hypothesized that

T-lymphocyte infiltration is deterred or the function is suppressed

in TTF-1-negative non-squamous NSCLC.

There is insufficient information on the association

between napsin A expression and clinical outcomes after ICI

therapy. Napsin A is an aspartic proteinase expressed on alveolar

type 2 cells, contributing to surfactant protein synthase.

Immunohistochemistry of napsin A is considered comparable to that

of TTF-1 for diagnosing primary lung adenocarcinoma, and dual

staining is likely the most beneficial (23,24).

Although it is difficult to explain the biological or immunological

significance of napsin A expression in relation to ICI therapy for

NSCLC, the selection of TTF-1/napsin A-negative non-squamous NSCLC

may result in the identification of more poorly differentiated

tumors.

The present study has several limitations. First,

the sample size was small, which may not sufficiently represent

NSCLC patients. Second, given the retrospective nature of the

study, the imbalance in patient backgrounds may have affected the

analysis, although multivariate analysis was performed to adjust

the potential prognostic factors.

In summary, we observed an association between TTF-1

expression, as evaluated using a cocktail antibody, and the

effectiveness of ICI therapy. Further accumulation of data

regarding TTF-1 evaluation methodologies and their association with

the prognosis of NSCLC patients is necessary.

Supplementary Material

Representative images of TTF-1

staining. (A) Hematoxylin-eosin staining findings of a

TTF-1-positive tumor. (B) TTF-1 staining findings of a

TTF-1-positive tumor. (C) Hematoxylin-eosin staining findings of a

TTF-1 negative tumor. (D) TTF-1 staining findings of a TTF-1

negative tumor. TTF-1-positivity was detected in normal alveolar

cells.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NM and MI designed the study and wrote the original

draft of the manuscript. NM, MI, DF, MH, NT, ZS, KTo, SO, SI, TM

and RH contributed to the acquisition of data. KTa and KH

contributed to the immunohistochemistry. NM and MI confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with The

Declaration of Helsinki and the Guideline of Ministry of Health,

Labor and Welfare and was approved by the Ethics Committee,

University of Toyama (approval no. R2020067). Because this study is

retrospective and noninvasive, written informed consent was not

required.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or

non-financial interests to disclose.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, AI tools were

used to improve the readability and language of the manuscript, and

subsequently, the authors revised and edited the content produced

by the AI tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the

ultimate content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Socinski MA: Cytotoxic chemotherapy in

advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A review of standard treatment

paradigms. Clin Cancer Res. 10:4210s–4214s. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR,

Steins M, Ready NE, Chow LQ, Vokes EE, Felip E, Holgado E, et al:

Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell

lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:1627–1639. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Garassino MC, Gadgeel S, Speranza G, Felip

E, Esteban E, Dómine M, Hochmair MJ, Powell SF, Bischoff HG, Peled

N, et al: Pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed and platinum in nonsquamous

non-small-cell lung cancer: 5-Year outcomes from the phase 3

KEYNOTE-189 study. J Clin Oncol. 41:1992–1998. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Minoo P, Su G, Drum H, Bringas P and

Kimura S: Defects in tracheoesophageal and lung morphogenesis in

Nkx2.1(-/-) mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 209:60–71. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hosono Y, Yamaguchi T, Mizutani E,

Yanagisawa K, Arima C, Tomida S, Shimada Y, Hiraoka M, Kato S,

Yokoi K, et al: MYBPH, a transcriptional target of TTF-1, inhibits

ROCK1, and reduces cell motility and metastasis. EMBO J.

31:481–493. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hwang DH, Sholl LM, Rojas-Rudilla V, Hall

DL, Shivdasani P, Garcia EP, MacConaill LE, Vivero M, Hornick JL,

Kuo FC, et al: KRAS and NKX2-1 mutations in invasive mucinous

adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Thorac Oncol. 11:496–503.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Matsubara D, Soda M, Yoshimoto T, Amano Y,

Sakuma Y, Yamato A, Ueno T, Kojima S, Shibano T, Hosono Y, et al:

Inactivating mutations and hypermethylation of the NKX2-1/TTF-1

gene in non-terminal respiratory unit-type lung adenocarcinomas.

Cancer Sci. 108:1888–1896. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Maeda Y, Tsuchiya T, Hao H, Tompkins DH,

Xu Y, Mucenski ML, Du L, Keiser AR, Fukazawa T, Naomoto Y, et al:

Kras(G12D) and Nkx2-1 haploinsufficiency induce mucinous

adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Invest. 122:4388–4400.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Snyder EL, Watanabe H, Magendantz M,

Hoersch S, Chen TA, Wang DG, Crowley D, Whittaker CA, Meyerson M,

Kimura S and Jacks T: Nkx2-1 represses a latent gastric

differentiation program in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Cell.

50:185–199. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Barletta JA, Perner S, Iafrate AJ, Yeap

BY, Weir BA, Johnson LA, Johnson BE, Meyerson M, Rubin MA, Travis

WD, et al: Clinical significance of TTF-1 protein expression and

TTF-1 gene amplification in lung adenocarcinoma. J Cell Mol Med.

13:1977–1986. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chung KP, Huang YT, Chang YL, Yu CJ, Yang

CH, Chang YC, Shih JY and Yang PC: Clinical significance of thyroid

transcription factor-1 in advanced lung adenocarcinoma under

epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor

treatment. Chest. 141:420–428. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Nishioka N, Hata T, Yamada T, Goto Y,

Amano A, Negi Y, Watanabe S, Furuya N, Oba T, Ikoma T, et al:

Impact of TTF-1 expression on the prognostic prediction of patients

with non-small cell lung cancer with PD-L1 expression levels of 1%

to 49%, treated with chemotherapy vs chemoimmunotherapy: A

multicenter, retrospective study. Cancer Res Treat. 57:412–421.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ibusuki R, Yoneshima Y, Hashisako M,

Matsuo N, Harada T, Tsuchiya-Kawano Y, Kishimoto J, Ota K,

Shiraishi Y, Iwama E, et al: Association of thyroid transcription

factor-1 (TTF-1) expression with efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors

plus pemetrexed and platinum chemotherapy in advanced non-squamous

non-small cell lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 11:2208–2215.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Nakahama K, Kaneda H, Osawa M, Izumi M,

Yoshimoto N, Sugimoto A, Nagamine H, Ogawa K, Matsumoto Y, Sawa K,

et al: Association of thyroid transcription factor-1 with the

efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced

lung adenocarcinoma. Thorac Cancer. 13:2309–2317. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Katayama Y, Yamada T, Morimoto K, Fujii H,

Morita S, Tanimura K, Takeda T, Okada A, Shiotsu S, Chihara Y, et

al: TTF-1 expression and clinical outcomes of combined

chemoimmunotherapy in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: A

prospective observational study. JTO Clin Res Rep.

4(100494)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Terashima Y, Matsumoto M, Iida H,

Takashima S, Fukuizumi A, Takeuchi S, Miyanaga A, Terasaki Y,

Kasahara K and Seike M: Predictive impact of diffuse positivity for

TTF-1 expression in patients treated with platinum-doublet

chemotherapy plus immune checkpoint inhibitors for advanced

nonsquamous NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 4(100578)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Uhlenbruch M and Krüger S: Effect of TTF-1

expression on progression free survival of immunotherapy and

chemo-/immunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J

Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 150(394)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Iso H, Hisakane K, Mikami E, Suzuki T,

Matsuki S, Atsumi K, Nagata K, Seike M and Hirose T: Thyroid

transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) expression and the efficacy of

combination therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors and cytotoxic

chemotherapy in non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Transl

Lung Cancer Res. 12:1850–1861. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Nishioka N, Kawachi H, Yamada T, Tamiya M,

Negi Y, Goto Y, Nakao A, Shiotsu S, Tanimura K, Takeda T, et al:

Unraveling the influence of TTF-1 expression on immunotherapy

outcomes in PD-L1-high non-squamous NSCLC: A retrospective

multicenter study. Front Immunol. 15(1399889)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Vidarsdottir H, Tran L, Nodin B, Jirström

K, Planck M, Mattsson JSM, Botling J, Micke P, Jönsson P and

Brunnström H: Comparison of three different TTF-1 clones in

resected primary lung cancer and epithelial pulmonary metastases.

Am J Clin Pathol. 150:533–544. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Cardnell RJG, Behrens C, Diao L, Fan Y,

Tang X, Tong P, Minna JD, Mills GB, Heymach JV, Wistuba II, et al:

An integrated molecular analysis of lung adenocarcinomas identifies

potential therapeutic targets among TTF1-negative tumors, including

DNA repair proteins and Nrf2. Clin Cancer Res. 21:3480–3491.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Prelaj A, Tay R, Ferrara R, Chaput N,

Besse B and Califano R: Predictive biomarkers of response for

immune checkpoint inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J

Cancer. 106:144–159. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Turner BM, Cagle PT, Sainz IM, Fukuoka J,

Shen SS and Jagirdar J: Napsin A, a new marker for lung

adenocarcinoma, is complementary and more sensitive and specific

than thyroid transcription factor 1 in the differential diagnosis

of primary pulmonary carcinoma: Evaluation of 1674 cases by tissue

microarray. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 136:163–171. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

El Hag M, Schmidt L, Roh M and Michael CW:

Utility of TTF-1 and Napsin-A in the work-up of malignant

effusions. Diagn Cytopathol. 44:299–304. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|