Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC), one of the most prevalent

malignancies of the female reproductive system worldwide, is

primarily driven by persistent infection with high-risk human

papillomavirus (HPV) (1). It is

noteworthy that increasing evidence indicates that a subset of CC

progresses through HPV-independent mechanisms, a process

intricately linked to dynamic changes in the tumor microenvironment

(TME) and complex intercellular communication (2,3).

Currently, CC continues to pose important challenges in terms of

drug resistance, precise diagnosis and effective treatment.

Previous studies have shown that tumor heterogeneity and genomic

instability can lead to resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy

(4,5). Meanwhile, the infiltration of

immunosuppressive cells, impaired T-cell function and upregulation

of immune checkpoint molecules within the CC microenvironment

collectively promote tumor immune evasion, thereby limiting the

efficacy of immunotherapy (6,7).

Furthermore, beyond anti-angiogenic agents, there remains a lack of

effective targeted treatment strategies for metastatic or recurrent

CC in clinical practice (8).

However, current screening strategies and biomarker research for CC

remain predominantly focused on HPV testing and cytological

abnormalities. Although these methods can, to certain extent,

predict disease progression and monitor treatment response, they

exhibit notable limitations in accurately identifying precancerous

lesions, addressing HPV-independent carcinogenic mechanisms, and

monitoring treatment response and recurrence in patients with

advanced-stage disease. Therefore, developing reliable biomarkers

that can reflect TME alterations and disease evolution, and

building more effective treatment strategies based on such

biomarkers, has become a critical issue that urgently needs to be

addressed in the clinical management of CC.

Extracellular vesicles (EV) have emerged as

promising tools in liquid biopsy and tumor mechanism research due

to their ability to carry various bioactive molecules such as

nucleic acids, proteins and metabolites (9). As a class of endogenous

nanoparticles, EVs possess inherent characteristics, including low

immunogenicity, high stability, and an exceptional ability to cross

biological barriers, that make them ideal, universal platforms for

cancer research and clinical application, far beyond a single

cancer type (10). This broad

utility is particularly evidenced in the field of biomarker

discovery, where EV-based analyses have demonstrated significant

diagnostic and prognostic value across a spectrum of malignancies,

including breast, pancreatic and lung cancers (11,12).

EVs are widely present in multiple biological fluids such as blood,

saliva and urine (13-15).

Among these, plasma holds particular value in EV research due to

its easy accessibility, abundant availability, and capacity to

rapidly and systematically reflect the body's pathophysiological

status. EVs in plasma originate from tissues and organs throughout

the body, including tumor tissues from different anatomical sites,

enabling them to comprehensively reflect the body's tumor burden

and heterogeneity (16,17). Building upon this universal

potential of plasma EVs, their role in CC was investigated. During

the development and progression of CC, plasma EVs are specifically

regulated by the pathological state of CC cells, and their

molecular composition carries disease-specific biological

information (18). Therefore,

analyzing the specific molecular characteristics of plasma EVs in

the context of CC not only provides new perspectives for

understanding the biological mechanisms of the disease, but also

offers powerful tools for developing non-invasive diagnostic

strategies.

At the molecular mechanism level, transcriptomics

microRNA (miRNA or miR) sequencing has become a widely used

approach for investigating cellular phenotypes and functions by

deciphering upstream regulatory networks of gene expression

(19,20). Specifically, miRNAs carried by EVs

are not only protected from degradation but also functionally

contribute to investigating the cause of disease, thus classifying

cancer subtypes or acting as carriers targeting different target

cells (12). They play important

roles in a variety of cancer types and inflammatory diseases,

including CC (21). However,

transcriptomic analyses alone often fail to capture the

multidimensional regulatory complexity of the disease due to

inherent limitations in resolution and functional annotation. To

overcome these limitations, proteomics offers a complementary and

indispensable layer of information. As a downstream executor of

gene expression, proteomic analysis provides detailed insights into

post-translational modifications and functional protein interaction

networks (22). This downstream

perspective is critical for revealing the functional molecular

mechanisms of diseases, identifying new biomarkers, and advancing

personalized medicine. Building on the strengths of both fields, an

integrated multi-omics strategy has emerged as a powerful paradigm.

Indeed, previous studies have shown that integrating

transcriptomics and corresponding proteomics data from EV samples

cannot only reveal the association between genes and proteins, and

explore the potential mechanisms of molecular networks, but also

significantly enhance the identification of potential biomarkers

for disease diagnosis (23,24).

Consequently, monitoring circulating EV-derived miRNAs and proteins

in body fluids offers a promising strategy for accurate,

non-invasive and rapid disease diagnosis. Therefore, it was

hypothesized that concurrently monitoring EV-derived miRNAs and

proteins in plasma could provide a more accurate, non-invasive and

comprehensive strategy for understanding CC pathogenesis and

identifying diagnostic signatures.

In the present study, the aforementioned integrated

multi-omics approach was employed to systematically reveal the

molecular features and regulatory networks of plasma EV in CC

progression. Combined analysis of EV miRNA transcriptomics and

proteomics identified 22 differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs) and

49 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs). These molecules were

co-enriched in core pathways implicated in CC, including HPV

infection, p53 signaling, PI3K-Akt pathway and

complement/coagulation cascades. Notably, through multi-omics

integration, the Homo sapiens (hsa)-miR-1-3p-LRP1 axis was

identified and experimentally validated as a potential key

regulatory target in CC. The present findings not only provide

biological evidence supporting the use of plasma EVs as disease

biomarkers, but also reveal novel signature molecules involved in

CC onset and progression, thereby outlining a viable pathway for

EV-mediated liquid biopsy and the development of targeted

therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

All participants were recruited from the Department

of Gynecology, Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital (Qinghai,

China). The cohort included 3 female patients with CC and 3 female

healthy controls (HCs). The ages of the patients with CC were 44,

47 and 69 years (median: 53 years; range: 44-69 years), while the

HCs were 58, 61, and 61 years old (median: 61 years; range: 58-61

years). This sample size aligns with standard practices for

exploratory analysis using omics technologies and meets the

requirements for methodological reproducibility (25,26).

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of

Qinghai University Affiliated Hospital (approval no. P-SL-202157)

in compliance with ethical standards, and written informed consent

was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. CC

diagnoses were pathologically confirmed according to the

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)

staging system (2018) (27).

Venous blood samples were collected immediately after admission.

Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 4˚C and 1,000 x g for 15

min (cat. no. HT165; Cence; https://www.xiangyilxj.com/) and stored at -80˚C until

further analysis.

EV preparation

EV were isolated from 2 ml plasma using a

standardized ultracentrifugation (UC) protocol (28). Briefly, plasma samples were diluted

10-fold with PBS (cat. no. G4202; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.) to a final volume of 20 ml. Sequential centrifugation steps

were then performed at 2,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C to eliminate

cellular debris and at 10,000 x g for 20 min at 4˚C to pellet

larger apoptotic bodies, and filtered through a 0.22-µm pore-size

membrane filter (cat. no. SLGP033R; MilliporeSigma) to remove large

particulate contaminants. The supernatant was subsequently

ultracentrifuged at 120,000 x g for 120 min at 4˚C (cat. no. OPTIMA

L100XP; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) to obtain purified EV pellets, which

were resuspended in 400 µl sterile PBS and stored at -80˚C until

further analysis.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

(NTA)

NTA was performed using a NanoSight NS300 system

(Malvern Panalytical, Ltd.) equipped with a 488-nm laser and a

high-sensitivity sCMOS (scientific complementary

metal-oxide-semiconductor) camera, according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The samples were then diluted with PBS to achieve an

optimal concentration for accurate particle counting and sizing,

resulting in a final concentration of 30-50 particles per frame.

The particles per frame value was 30-60, with a camera detection

threshold of 15 and an automated injection flow rate of 30

µl/min.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

analysis

After fixation with an equal volume of 4%

paraformaldehyde (cat. no. BL539A; Biosharp Life Sciences) at 4˚C

for 30 min, the EV suspension was deposited onto

Formvar/carbon-coated copper grids (cat. no. BZ11032b; Henan

Zhongjingkeyi Technology Co., Ltd.) and allowed to adsorb for 30

min at room temperature (RT). The grids were then washed twice with

PBS, followed by post-fixation with 1% glutaraldehyde for 5 min.

After two washes with ultrapure water, the samples were negatively

stained with 2% uranyl acetate (cat. no. GZ02625, Tianjin Ruixin

Technology Co., Ltd.) at RT for 40 sec. Morphological observation

was ultimately performed using a Talos L120C G2 TEM (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) operated at 120 kV.

Western blot (WB) analysis

Purified EVs were quantified using a the

Bicinchoninic Acid Assay Kit (BCA; cat. no. P0011; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Deformed EV proteins (loaded with 20 µg of protein

per lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE using the One-Step PAGE

Gel Rapid Preparation Kit (cat. no. PG212; Shanghai Epizyme

Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd.; Ipsen Pharma) and

transferred to a PVDF membrane (cat. no. ISEQ00010;

MilliporeSigma). Membranes were blocked with 5% (w/v) non-fat milk

(cat. no. 232100; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) in PBS containing 0.1%

Tween-20 (cat. no. 30189380; Shanghai HUSHI, Ltd.) for 1 h at RT

and subsequently incubated overnight at 4˚C with the following

primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer: Anti-Alix (1:1,000;

cat. no. 18269; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-Flotillin-1

(1:1,000; cat. no. 610820; BD Biosciences) and anti-CD63 (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab68418; Abcam). After five washes with PBS, membranes

were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:3,000; cat. no. 7074; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) for 1 h at RT. Protein bands were

visualized using a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Clinx Science

Instruments, Co., Ltd.) with an enhanced chemiluminescence

substrate (cat. no. WBKLS0500; MilliporeSigma).

miRNA sequencing and bioinformatic

analysis

Total RNA was extracted from purified EV using

RNAiso for miRNA reagent (cat. no. 9753A, Takara Bio, Inc.), a

specialized reagent designed for the simultaneous isolation of both

large and small RNAs. RNA concentration and purity were assessed

using a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (cat. no. 840-317400;

NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Briefly, EV

samples were thoroughly mixed with 140 µl chloroform (cat. no.

C2432; MilliporeSigma) and centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 15 min at

4˚C. The aqueous phase was collected and combined with 1.5 vol

absolute ethanol. The mixture was transferred to RNeasy

purification columns (cat. no. 74104; Qiagen GmbH) for RNA

purification. Small RNA libraries were constructed from 1 µg of

total RNA per sample. Subsequently, 4 µl miRNA was subjected to 18

cycles of microamplification using the SMARTer® Starfish Total

RNA-seq Kit (cat. no. 634413; Takara Bio, Inc.), and the amplified

products were purified with AMPure XP beads (cat. no. A63881;

Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Libraries were then constructed from 1 ng

complementary DNA (cDNA) using the Transpose DNA Library Prep Kit

for Illumina, Inc. (cat. no. K0012; LifeInt) with 14 amplification

cycles. The final libraries were quality-controlled on an Agilent

2100 Bioanalyzer (cat. no. G2939A; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) to

ensure a peak distribution between 140-160 bp, corresponding to

miRNA inserts, and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform

(Illumina, Inc.), generating paired-end 150-bp reads from six

samples.

For bioinformatic analysis, raw sequencing data were

processed with Trim Galore (v0.6.7; The Babraham Institute) to

remove adapter sequences and low-quality reads (Phred quality score

<30). High-quality reads were aligned to the human reference

genome GRCh38/hg38 using Bowtie2 (v2.4.5). miRNA expression

quantification was performed with miRDeep2 (v2.0.1.3) to calculate

read counts, and miRNAs with null expression in ≥50% of samples

were filtered out. DEMs were identified using DESeq2 (v1.32.0) with

thresholds of fold-change (FC) >1.2 and adjusted P<0.05.

miRNA target genes were predicted based on the miRTarBase database

(v9.0; https://mirtarbase.cuhk.edu.cn/~miRTarBase/miRTarBase_2022/php/index.php).

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

(KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted using

ClusterProfiler (v4.2.2) (29),

which is available from Bioconductor (https://bioconductor.org/packages/clusterProfiler/). A

significance threshold of P<0.05 was applied. The results were

visualized with ggplot2 (v3.3.5).

Proteomic profiling and bioinformatic

analysis

EV samples were thawed at -80˚C and lysed on ice

with 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail using ultrasonication.

The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C to

remove cellular debris, and the supernatant was transferred to

fresh microcentrifuge tubes. Protein concentration was quantified

using a BCA assay kit (cat. no. P0011; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). For each sample, 50 µg EV protein was adjusted to

100 µl with lysis buffer. Proteins were reduced with 5 mM

dithiothreitol (cat. no. 43815; MilliporeSigma) at 56˚C for 30 min,

followed by alkylation with 11 mM iodoacetamide (cat. no. I1149;

MilliporeSigma) in the dark at RT for 15 min. Urea concentration

was diluted to <2 M using tetraethylammonium bromide. Sequential

tryptic digestion was performed with trypsin. Peptides were

reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid (FA: cat. no. 94318;

MilliporeSigma) and separated on an EASY-nLC 1200 UHPLC system

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The mobile phases consisted of

0.1% FA + 2% acetonitrile (ACN; phase A) and 0.1% FA + 90% ACN

(phase B). The gradient program was: 0-68 min (6-23% B), 68-82 min

(23-32% B), 82-86 min (32-80% B) and 86-90 min (80% B) at a flow

rate of 500 nl/min. Peptides were ionized via a nano-electrospray

ionization source and analyzed on an Orbitrap Exploris™ 480 mass

spectrometer. The ion source voltage was set to 2.3 kV. FAIMS

compensation voltages were configured at 45 and -65 V.

High-resolution Orbitrap detection was applied for both precursor

(400-1,200 m/z; 60,000 resolution) and fragment ions (fixed start

at 110 m/z; 15,000 resolution), with TurboTMT disabled.

Data-dependent acquisition mode was used to select the top 25 most

intense precursors per cycle for fragmentation (AGC target 100%,

signal threshold 5x104 ions/sec). Raw data were

processed through Proteome Discoverer (v2.4.1.15) against the

UniProt human proteome database (Homo_SP_20201214.fasta; 20,395

sequences). Screening thresholds for differential proteins were as

follows: FC>1.5 and P<0.05. Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

networks were analyzed using the STRING database (v11.5; https://cn.string-db.org/; confidence level >0.9)

and visualized using Cytoscape (v3.10.3). Functional enrichment

analysis was conducted using ClusterProfiler (v4.2.2), and the

results were visualized with ggplot2 (v3.3.5). Tissue localization

of EV proteins was inferred by mapping expression profiles to

immunohistochemical data from the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org).

Integrative analysis of DEMs and

proteomics

The co-expression associations between DEMs and DEPs

were evaluated using Spearman's correlation coefficient, and were

visualized via heatmaps (v1.0.12). By integrating KEGG pathway

annotations of DEM target genes and DEPs, pathways significantly

enriched in both omics datasets were identified. Overlapping

pathways were illustrated using Venn diagrams (v1.6.20), available

on CRAN (https://cran.r-project.org/package=VennDiagram)

(30). Functional prioritization

of shared pathways was performed based on enrichment factor and

gene/protein coverage. From the miRNA-protein co-expression

network, highly dense functional modules were extracted using the

MCODE plugin (Cytoscape, v2.0.0; https://apps.cytoscape.org/apps/mcode). Core

regulatory hubs were identified via the Degree algorithm in the

CytoHubba plugin (Cytoscape, v0.1), which were defined as molecules

with the highest topological centrality.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Following plasma EV extraction from the HC and CC

groups, total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer's

protocol of TRIzol™ reagent (cat. no. 15596026; Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The key steps included lysing the sample

in TRIzol™, followed by 5-min incubation at RT, addition of

chloroform (cat. no. C2432; MilliporeSigma), centrifugation to

separate the phases, collection of the aqueous phase, precipitation

of RNA with isopropanol (cat. no. 34863; MilliporeSigma), two

washes with 75% ethanol, air-drying and resuspension of the RNA

pellet in DEPC-treated water. RNA concentration and purity were

assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. For RT, LRP1 mRNA was

transcribed using the PrimeScript™ RT Kit (cat. no. RR047; Takara

Bio, Inc.) with 1 µg total RNA as a template, and the product was

diluted 5-fold for later use. To ensure specific detection of

mature hsa-miR-1-3p, a targeted stem-loop RT primer was used for

RT. qPCR was then performed using the SYBR Green Premix (cat. no.

AG11701; Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd.), which

was selected for its cost-effectiveness and compatibility with

simultaneous detection of both miRNA and mRNA targets, with a

reaction volume of 20 µl, including 2 µl diluted cDNA, 0.8 µl

forward and reverse primers (10 µM), 10 µl pre-mixed SYBR Green

Premix, and 6.4 µl ddH2O. The program was set to 95˚C

pre-denaturation for 1 min, followed by 45 cycles of 94˚C for 20

sec and 58˚C for 30 sec. Melting curve analysis was systematically

performed to verify amplification specificity (LineGene 9600 Plus;

Hangzhou Bioer Co., Ltd.). All samples were analyzed in triplicate

wells with blank controls, and relative expression levels were

calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (31). The internal references were GAPDH

(for LRP1) and U6 (for miR-1-3p). The primer sequences are shown in

Table I.

| Table IPrimer sequences. |

Table I

Primer sequences.

| Primer | Sequence

(5'-3') | Note |

|---|

| hsa-miR-1-3p | F:

TGGAATGTAAAGAAGTATGTAT | Targets the mature

miR-1-3p sequence |

| | R:

GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT | Universal reverse

primer |

| LRP1 | F:

CTATCGACGCCCCTAAGACTT | |

| | R:

CATCGCTGGGCCTTACTCT | |

| GAPDH |

TGTGGGCATCAATGGATTTGG | |

| |

ACACCATGTATTCCGGGTCAAT | |

Statistical analysis

Graphical and statistical analyses were performed

using the ggplot2 package (v3.3.5), GraphPad Prism (v8.0.12;

GraphPad; Dotmatics) and Cytoscape software (v3.10.2). Data from

three independent experiments are presented as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical comparisons between the HC and CC groups

were performed using an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results and Discussion

EV isolation and characterization from

plasma samples

The present study included a total of 6 plasma

samples, comprising 3 patients with CC and 3 HCs. CC diagnosis was

confirmed according to the 2018 FIGO staging criteria (32), supplemented by imaging, molecular

pathology, and histopathological biopsy results. The overall

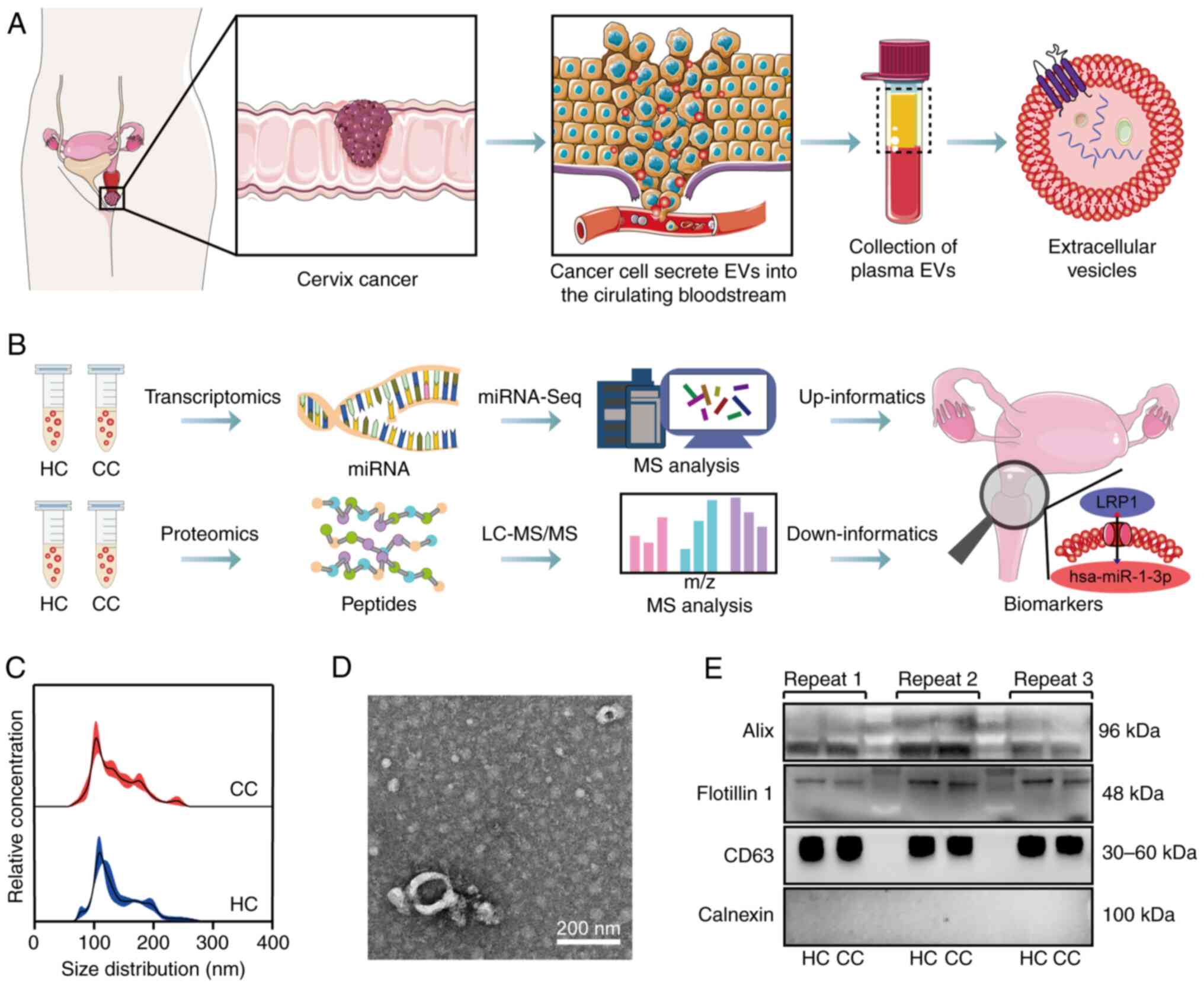

experimental workflow is revealed in Fig. 1A, while the analytical pipeline for

miRNA transcriptomics, proteomics and multi-omics integration is

outlined in Fig. 1B. EVs were

isolated from plasma using UC. NTA showed EV sizes predominantly

ranging from 50-200 nm, with peak sizes of 105 nm (CC) and 111 nm

(HC) (Fig. 1C). No significant

intergroup differences were observed in particle size distribution

or concentration (~1.5x1010 particles/ml). TEM imaging

demonstrated EV exhibiting typical cup-shaped or biconcave discoid

morphology (Fig. 1D). Following

the MISEV2018 guidelines (33), WB

analysis confirmed EV' purity, demonstrating consistent expression

of positive markers (Alix, Flotillin-1 and CD63) and absence of

calnexin contamination (20 µg protein load; Fig. 1E). Semi-quantitative analysis

showed stable marker expression without significant differences

between the HC and CC groups (Fig.

S1A-C).

Differential expression and functional

implications of EV-derived miRNAs in CC

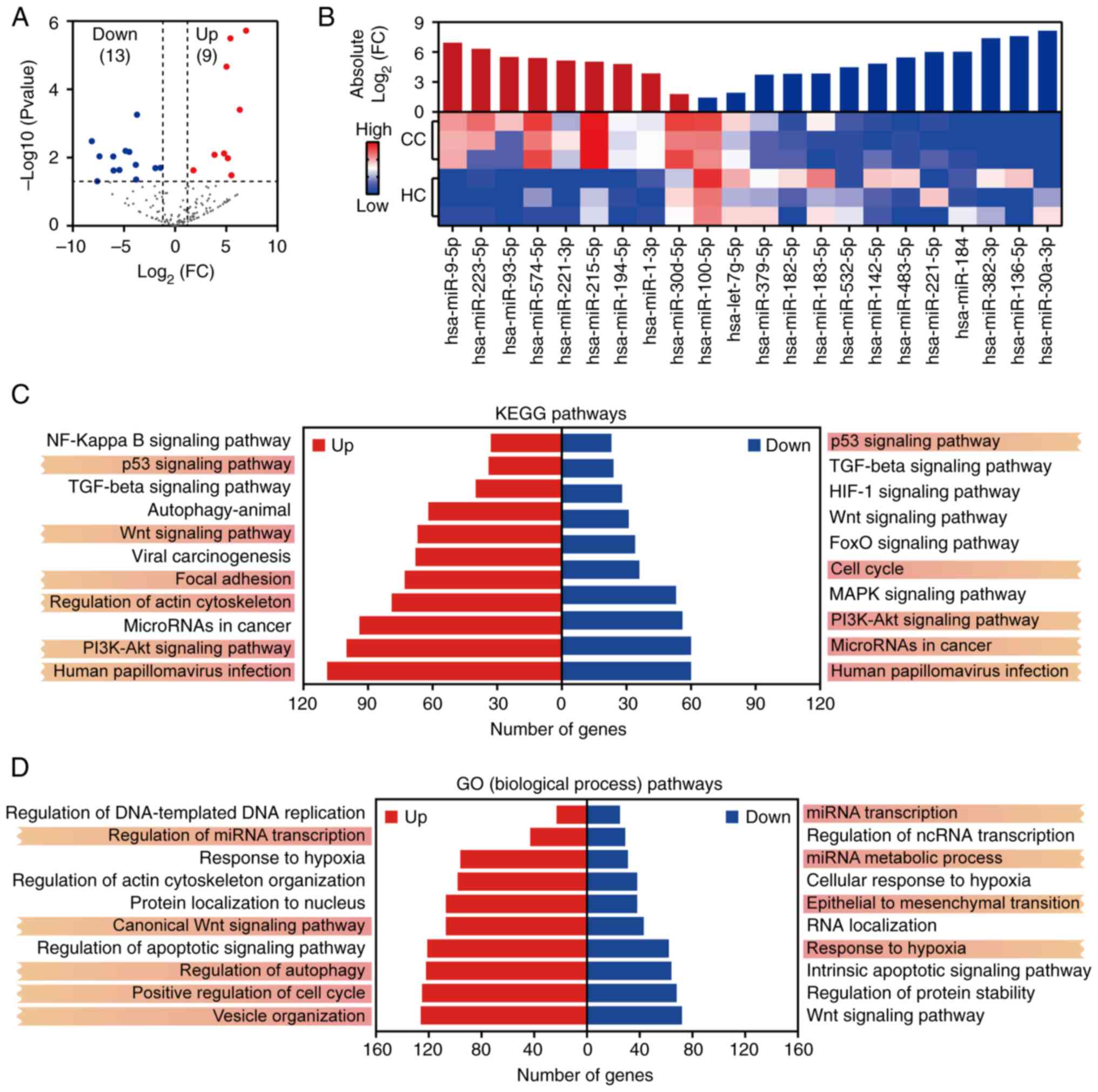

miRNA sequencing identified 2,656 miRNAs, with 22

DEMs (9 upregulated and 13 downregulated in CC) using DESeq2 (FC

>1.2, P<0.05; Fig. 2A).

Hierarchical clustering showed distinct disease-specific expression

profiles (Fig. 2B). To further

investigate the biological functions of these DEMs, their target

genes were predicted using the miRTarBase database. These predicted

targets were then subjected to KEGG and GO enrichment analyses.

KEGG analysis showed that DEM targets were significantly enriched

in several key cancer-related pathways, including the p53 signaling

pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, Wnt signaling pathway, focal

adhesion and HPV infection (Fig.

2C). These pathways are critically involved in HPV-associated

oncogenesis, immune evasion mechanisms, chemoresistance and TME

signaling (34,35). GO enrichment analysis further

revealed that these miRNAs were involved in biological processes

such as regulation of miRNA transcription, canonical Wnt signaling

pathway, vesicle organization, regulation of autophagy and positive

regulation of the cell cycle (Fig.

2D). Collectively, these findings suggest that EV-derived

miRNAs may contribute to CC progression through multiple functional

modules, including HPV-induced cell cycle dysregulation,

EV-mediated tumor-stroma communication and stress response

regulation (36,37).

Specific miRNA-pathway interactions were further

investigated. The target genes of miR-221-3p and miR-182-5p were

significantly enriched in HPV infection and PI3K-Akt signaling,

while hsa-miR-30a-3p and hsa-miR-194-5p were enriched in p53

signaling. This suggests that EV-derived miRNAs may synergize with

viral oncoproteins to remodel oncogenic signaling networks and

promote chemoresistance. For example, miR-30a-3p may enhance

chemoresistance by inhibiting downstream targets of p53(38). This indicates that EV miRNAs may

act as amplifiers of HPV oncogenesis and promote tumor

heterogeneity through intercellular communication; thus, targeting

these miRNAs may reverse chemoresistance. Furthermore, the

enrichment of DEM target genes in positive regulation of the cell

cycle, vesicle organization, miRNA transcription and regulation of

actin cytoskeleton organization pathways likely contributes to CC

proliferation and invasion. Specifically, hsa-miR-221-3p and

hsa-miR-30d-5p both target CASP3, a key regulator of apoptosis and

tumor cytotoxicity (39), which

may influence apoptotic processes. Additionally, hsa-miR-221-3p may

affect transcription factor activity (40). hsa-miR-9-5p and hsa-miR-93-5p were

associated with miRNA transcription, suggesting their potential

involvement in epigenetic feedback loops that drive tumor

heterogeneity (41,42).

Proteomic profiling of EV reveals

immune, metabolic and coagulation signatures in CC

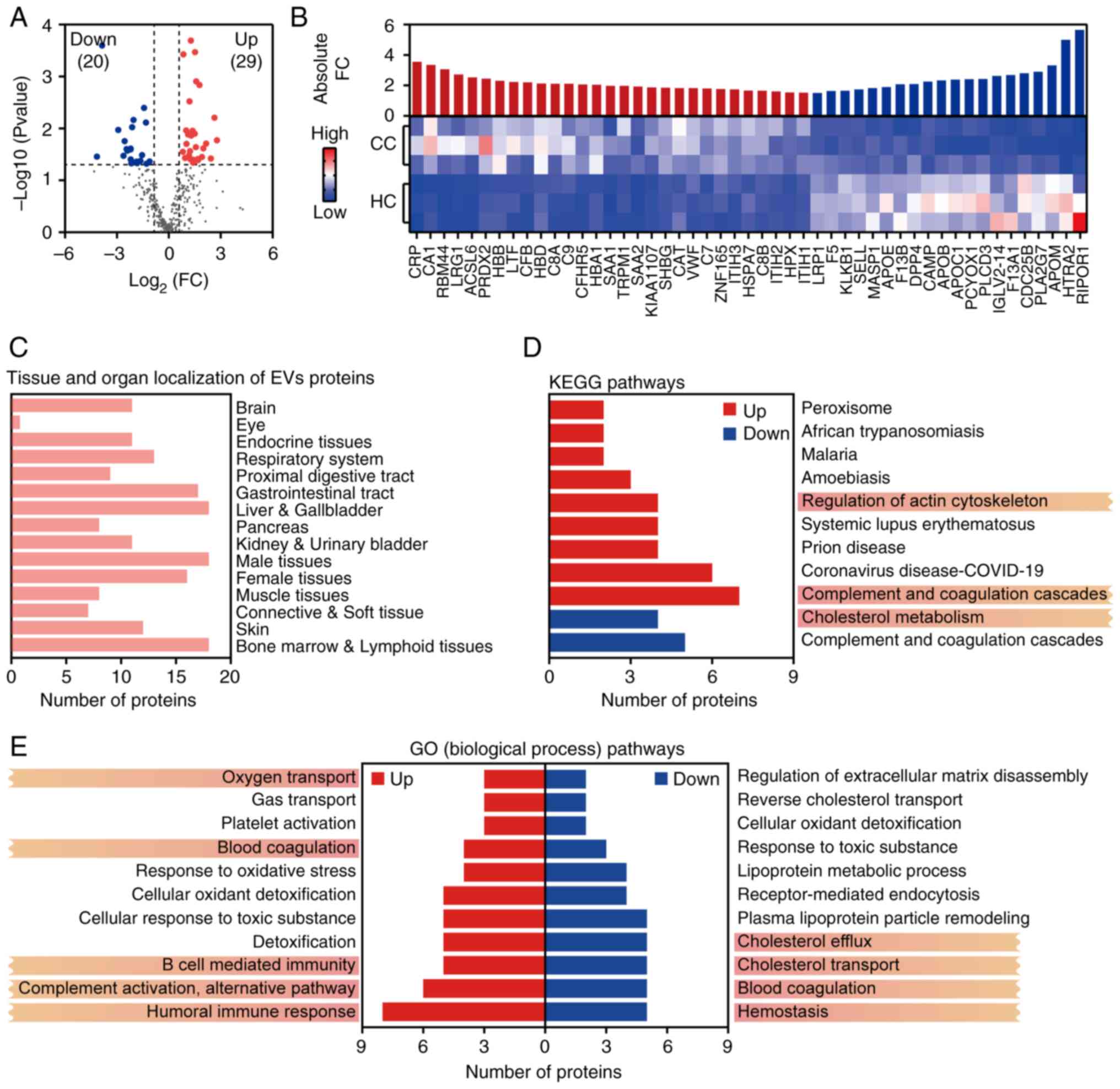

Proteomic analysis identified 363 EV-associated

proteins, with 49 DEPs (29 upregulated and 20 downregulated) using

limma (FC >1.5, P<0.05; Fig.

3A). Hierarchical clustering revealed disease-specific protein

signatures (Fig. 3B). Tissue

origin analysis indicated that DEPs were primarily derived from the

liver, gallbladder, female reproductive organs and gastrointestinal

tract (Fig. 3C). This

tissue-specific distribution highlights EVs as promising biomarkers

for reflecting pathophysiological alterations, particularly in

reproductive and digestive system-related malignancies. To explore

the functional roles of these DEPs, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

were conducted. KEGG pathway analysis showed significant enrichment

of DEPs in the complement and coagulation cascades, regulation of

actin cytoskeleton, and cholesterol metabolism pathways (Fig. 3D). GO enrichment further identified

DEP involvement in complement activation, the alternative

complement pathway, blood coagulation and lipopolysaccharide

(LPS)-mediated signaling (Fig.

3E). These pathways may collectively drive CC progression by

modulating immunosuppressive TMEs, thus enhancing cell motility and

invasion, and facilitating HPV genome integration.

Previous studies have shown that HPV-infection tumor

cells can escape immune escape by inhibiting the activity of

natural killer and T cells (43).

The present findings further support this mechanism, as multiple

complement-related proteins (including C5, C7, C8A/B, C9 and CFB)

were significantly upregulated in CC-EV and enriched in the

alternative complement activation pathway (44,45).

These observations align with previous research suggesting that EV

contribute to immunosuppressive environments via complement system

modulation (46). Additionally,

inflammatory mediators such as CRP and SAA1/2 were highly expressed

and mapped to pathways related to LPS signaling and acute

inflammatory responses (47,48).

These proteins may contribute to an inflammatory microenvironment

that supports persistent HPV infection and tumor progression. EVs

also carry elevated levels of antioxidant enzymes, including

catalase and peroxiredoxin-2, which are known to neutralize

reactive oxygen species and maintain redox balance, thereby

preserving tumor cell viability under oxidative stress (49,50).

Lipid metabolism-related proteins, such as APOE, APOB and APOC1,

were significantly enriched in the cholesterol metabolism pathway,

while pattern recognition receptors such as TLR4 were involved in

activating the NF-κB pathway. For example, overexpression of APOE

in EVs may enhance CC cell invasion via the PI3K-Akt signaling

pathway (51). This suggests that

EV act as molecular hubs integrating metabolic reprogramming and

inflammatory signaling to support a tumor-permissive

microenvironment and sustain malignant transformation. In the

current study, aberrant expression of F5, F13A1 and F13B was

observed. These coagulation factors, which are involved in pathways

such as blood coagulation and platelet activation, may be

associated with CC angiogenesis and metastasis. Collectively, these

specific protein signatures offer promising targets for EV-based

liquid biopsy, and may provide new avenues for mechanistic studies

and therapeutic intervention in CC.

Integrated multi-omics analysis

reveals a key miRNA-protein regulatory axis in CC-EV

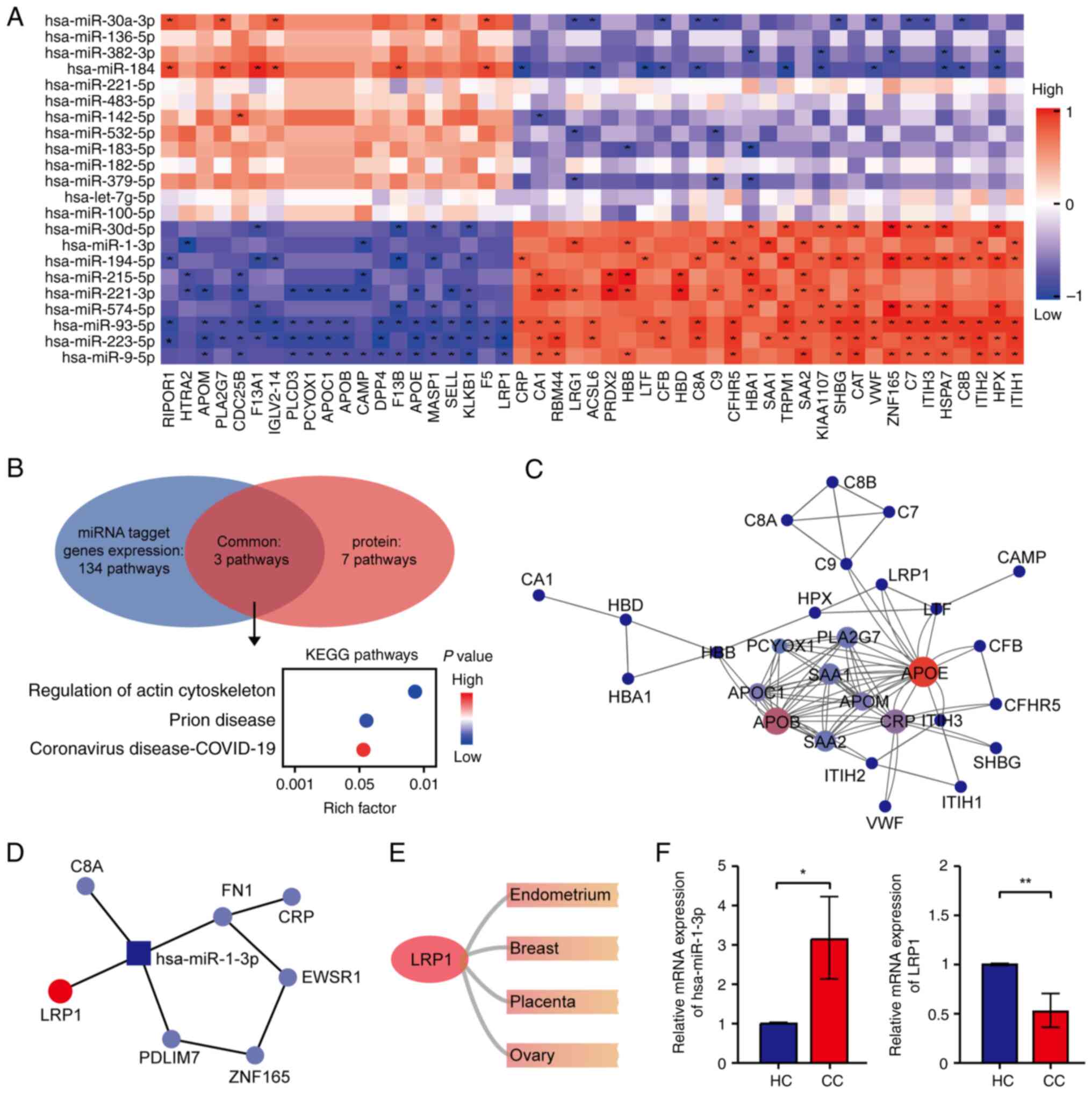

To systematically dissect the molecular regulatory

network mediated by EV in CC, an integrative analysis combining

EV-derived miRNA expression profiles and proteomic data was

performed. This multidimensional approach aimed to identify key

regulatory axes and diagnostic biomarkers. Spearman correlation

analysis revealed significant positive and negative associations

between DEMs and DEPs, suggesting that EV-contained miRNAs may

regulate downstream protein expression via direct targeting

(Fig. 4A). Pathway enrichment

analysis of co-expressed DEMs and DEPs demonstrated convergence in

three major biological pathways, namely regulation of the actin

cytoskeleton, prion disease and coronavirus disease-19 (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that

dysregulated EV-derived miRNAs may modulate cytoskeletal

remodeling, influence viral or misfolded protein handling, and

shape inflammatory responses within the TME. Notably, targeting of

the actin cytoskeleton regulator LRP1 by EV miRNAs suggests a

mechanistic link to enhanced CC cell motility and invasiveness

(52,53).

To further investigate protein-level regulatory

hubs, PPI network analysis identified APOE, CRP and APOB, which are

lipid metabolism-related proteins, as central nodes among DEPs

(Fig. 4C), thus highlighting lipid

metabolic reprogramming as a major driver of CC-associated EV

signaling. Cross-referencing this network with miRNA-protein

interactions revealed that hsa-miR-1-3p was the only miRNA directly

connected to multiple hub proteins, including LRP1, FN1, C8A and

PDLIM7 (Fig. 4D). Notably,

tissue-specific expression analysis showed that LRP1 was highly

expressed in female reproductive tissues, including the

endometrium, ovary and breast (Fig.

4E), thus underscoring its relevance in gynecological

malignancies. Previous research has shown that hsa-miR-1-3p

promotes non-small cell lung cancer progression by participating in

mechanosensitive mitotic processes (54), while activation of LRP1

fucosylation suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and

metastasis in CC (55). In the

present study, hsa-miR-1-3p was significantly upregulated in EV

from patients with CC, whereas LRP1 was significantly downregulated

(Fig. 4F), suggesting that this

miRNA may inhibit LRP1 expression to drive CC pathogenesis. These

findings indicate that elevated hsa-miR-1-3p in EV may inhibit

LRP1-mediated inflammatory chemotaxis, increase oxidative stress

within the TME, and activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling to promote

EMT. Such a mechanism aligns with previously described roles of

EV-carried miRNAs in tumor metastasis, and highlights the

hsa-miR-1-3p-LRP1 axis as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic

target (56). In summary, this

integrative multi-omics analysis uncovered a key EV-derived

miRNA-protein regulatory circuit in CC, providing novel insights

into disease progression and supporting the clinical utility of

hsa-miR-1-3p and LRP1 as candidate biomarkers for EV-based liquid

biopsy in CC.

Through integrated analysis of miRNA transcriptomics

and proteomics from plasma EV of HCs and patients with CC, the

present study unveiled a complex molecular regulatory network

during CC progression, which not only confirmed the potential of EV

as disease biomarkers, but, more importantly, revealed that

upregulated hsa-miR-1-3p in CC may participate in disease

progression by suppressing LRP1 expression.

The current study has demonstrated that

plasma-derived EV from patients with CC undergo marked alterations

in both miRNA and protein composition. The identified DEMs and

their predicted target genes were significantly enriched in

classical CC-related pathways such as p53 and PI3K-Akt (57,58).

Notably, through multi-omics integration analysis of plasma EV, it

was identified that activity changes in these pathways could be

carried and transmitted by EV. For instance, miR-221-3p and

miR-182-5p may simultaneously affect both HPV infection and the

PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, indicating that EV miRNAs may serve as

‘regulatory nodes’ coordinating the cross-talk between different

carcinogenic pathways, thereby amplifying the oncogenic effects of

HPV viral oncoproteins (59-62).

At the protein level, the present study revealed significant

enrichment of complement and coagulation cascades, suggesting that

tumor-derived EV may shape an immunosuppressive TME by modulating

the innate immune and coagulation systems, thus promoting immune

escape and angiogenesis (63,64).

Meanwhile, the dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism-related

proteins (such as APOE and APOB) coexists with the upregulation of

inflammatory mediators (such as CRP and SAA1/2), revealing a

vicious cycle where metabolic reprogramming and chronic

inflammation mutually promote each other in CC, with EVs serving as

important carriers for transmitting these signals (65,66).

Importantly, the current study found that EV-derived hsa-miR-1-3p

may suppress LRP1 expression, disrupt cytoskeletal stability and

subsequently activate pro-invasive signaling pathways such as

Wnt/β-catenin, ultimately accelerating CC metastasis. The present

research strategy connecting upstream regulatory molecules with

downstream functional proteins was able to construct a complete

signaling cascade from cause to effect, providing a new explanatory

framework for understanding the molecular mechanisms of CC.

In summary, the present study has systematically

delineated the molecular landscape of plasma EVs in CC through an

integrated multi-omics strategy and has proposed for the first time

that hsa-miR-1-3p-LRP1 is a key regulatory axis involved in disease

progression. This finding not only deepens the current

understanding of CC molecular mechanisms, but also lays a solid

theoretical foundation for developing EV-based non-invasive

diagnostic biomarkers and targeted therapeutic strategies.

Despite the aforementioned findings, the present

study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample

size makes it difficult to accurately evaluate the dynamic changes

of the hsa-miR-1-3p-LRP1 axis during CC initiation and progression,

requiring validation through longitudinal studies in larger

cohorts. Second, the current study primarily provides correlative

evidence at the bioinformatics level; whether hsa-miR-1-3p directly

targets, and regulates LRP1 and its specific biological functions

need verification through functional experiments such as luciferase

reporter assays or gene knockdown/overexpression. Furthermore, the

mechanism of this regulatory axis in HPV-independent carcinogenesis

remains to be further explored through future in vitro and

in vivo models, which would be crucial for elucidating its

specific value in different CC subtypes.

Supplementary Material

Western blot analysis of EVs marker

proteins. (A-C) Expression of (A) Alix (~96 kDa), (B) Flotillin-1

(~48 kDa) and (C) CD63 (~30-60 kDa) in plasma-derived EVs from HC

and CC. Left panels show representative western blot bands; right

panels display semi-quantitative analysis results based on band

intensity (n=3; ns: no significant difference). EVs, extracellular

vesicles; CC, cervical cancer; HC, healthy controls.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the 2024 Qinghai

Provincial Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project Qinghui

Health Office [grant no. (2024) 23].

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE310070 or

at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE310070;

and in the PRIDE Archive under accession number PXD071100 or at the

following URL: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/archive/projects/PXD071100.

Authors' contributions

LQ and RY designed the present study and contributed

to the writing of the manuscript. TB, WL and XL collected clinical

samples performed, clinical analysis and contributed to

interpretation of data. YY and WZ were responsible for data

analysis and interpretation, manuscript revision, response to

reviewers' comments, and finalization of the manuscript. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. LQ

and RY confirm the authenticity of all raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with

the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval (approval no.

P-SL-202157) was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Qinghai

University Hospital (Xining, China). All participants received

written and verbal information about the study, including the right

to voluntary participation and withdrawal. Written and verbal

informed consent was obtained by all participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Perkins RB, Wentzensen N, Guido RS and

Schiffman M: Cervical cancer screening: A review. JAMA.

330:547–558. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Yuan Y, Cai X, Shen F and Ma F: HPV

post-infection microenvironment and cervical cancer. Cancer Lett.

497:243–254. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

De la Fuente-Hernandez MA,

Alanis-Manriquez EC, Ferat-Osorio E, Rodriguez-Gonzalez A,

Arriaga-Pizano L, Vazquez-Santillan K, Melendez-Zajgla J,

Fragoso-Ontiveros V, Alvarez-Gomez RM and Maldonado Lagunas V:

Molecular changes in adipocyte-derived stem cells during their

interplay with cervical cancer cells. Cell Oncol (Dordr).

45:85–101. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bower JJ, Vance LD, Psioda M, Smith-Roe

SL, Simpson DA, Ibrahim JG, Hoadley KA, Perou CM and Kaufmann WK:

Patterns of cell cycle checkpoint deregulation associated with

intrinsic molecular subtypes of human breast cancer cells. NPJ

Breast Cancer. 3(9)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Liu Z, Lu Q, Zhang Z, Feng Q and Wang X:

TMPRSS2 is a tumor suppressor and its downregulation promotes

antitumor immunity and immunotherapy response in lung

adenocarcinoma. Respir Res. 25(238)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kandathil SA, Peter Truta I, Kadletz-Wanke

L, Heiduschka G, Stoiber S, Kenner L, Herrmann H, Huskic H and

Brkic FF: Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio might serve as a prognostic

marker in young patients with tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J

Pers Med. 14(159)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhang Y, Zhang Q, Han X, Han L, Wang T, Hu

J, Li L, Ding Z, Shi X and Qian X: SLAMF8, a potential new immune

checkpoint molecule, is associated with the prognosis of colorectal

cancer. Transl Oncol. 31(101654)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Garcia J, Hurwitz HI, Sandler AB, Miles D,

Coleman RL, Deurloo R and Chinot OL: Bevacizumab (Avastin®) in

cancer treatment: A review of 15 years of clinical experience and

future outlook. Cancer Treat Rev. 86(102017)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Pegtel DM and Gould SJ: Exosomes. Annu Rev

Biochem. 88:487–514. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Quan J, Liu Q, Li P, Yang Z, Zhang Y, Zhao

F and Zhu G: Mesenchymal stem cell exosome therapy: Current

research status in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and

the possibility of reversing normal brain aging. Stem Cell Res

Ther. 16(76)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jahan S, Mukherjee S, Ali S, Bhardwaj U,

Choudhary RK, Balakrishnan S, Naseem A, Mir SA, Banawas S,

Alaidarous M, et al: Pioneer role of extracellular vesicles as

modulators of cancer initiation in progression, drug therapy, and

vaccine prospects. Cells. 11(490)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee Y, Ni J, Beretov J, Wasinger VC,

Graham P and Li Y: Recent advances of small extracellular vesicle

biomarkers in breast cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Mol Cancer.

22(33)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Fang SB, Zhou ZR, Peng YQ, Liu XQ, He BX,

Chen DH, Chen D and Fu QL: Plasma EVs display antigen-presenting

characteristics in patients with allergic rhinitis and promote

differentiation of Th2 cells. Front Immunol.

12(710372)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Woo HK, Park J, Ku JY, Lee CH, Sunkara V,

Ha HK and Cho YK: Urine-based liquid biopsy: Non-invasive and

sensitive AR-V7 detection in urinary EVs from patients with

prostate cancer. Lab Chip. 19:87–97. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hu L, Zhang T, Ma H, Pan Y, Wang S, Liu X,

Dai X, Zheng Y, Lee LP and Liu F: Discovering the secret of

diseases by incorporated tear exosomes analysis via rapid-isolation

system: iTEARS. ACS Nano. 16:11720–11732. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Casanova-Salas I, Aguilar D,

Cordoba-Terreros S, Agundez L, Brandariz J, Herranz N, Mas A,

Gonzalez M, Morales-Barrera R, Sierra A, et al: Circulating tumor

extracellular vesicles to monitor metastatic prostate cancer

genomics and transcriptomic evolution. Cancer Cell.

42:1301–1312.e7. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lucien F, Gustafson D, Lenassi M, Li B,

Teske JJ, Boilard E, von Hohenberg KC, Falcón-Perez JM, Gualerzi A,

Reale A, et al: MIBlood-EV: Minimal information to enhance the

quality and reproducibility of blood extracellular vesicle

research. J Extracell Vesicles. 12(e12385)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Thippabhotla S, Zhong C and He M: 3D cell

culture stimulates the secretion of in vivo like extracellular

vesicles. Sci Rep. 9(13012)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li Y, Zhao J, Yu S, Wang Z, He X, Su Y,

Guo T, Sheng H, Chen J, Zheng Q, et al: Extracellular vesicles long

RNA sequencing reveals abundant mRNA, circRNA, and lncRNA in human

blood as potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis. Clin Chem.

65:798–808. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Garcia-Martin R, Wang G, Brandão BB,

Zanotto TM, Shah S, Kumar Patel S, Schilling B and Kahn CR:

MicroRNA sequence codes for small extracellular vesicle release and

cellular retention. Nature. 601:446–451. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hasanzadeh M, Movahedi M, Rejali M, Maleki

F, Moetamani-Ahmadi M, Seifi S, Hosseini Z, Khazaei M, Amerizadeh

F, Ferns GA, et al: The potential prognostic and therapeutic

application of tissue and circulating microRNAs in cervical cancer.

J Cell Physiol. 234:1289–1294. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hoshino A, Kim HS, Bojmar L, Gyan KE,

Cioffi M, Hernandez J, Zambirinis CP, Rodrigues G, Molina H,

Heissel S, et al: extracellular vesicle and particle biomarkers

define multiple human cancers. Cell. 182:1044–1061.e18.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Blaser MC, Buffolo F, Halu A, Turner ME,

Schlotter F, Higashi H, Pantano L, Clift CL, Saddic LA, Atkins SK,

et al: Multiomics of tissue extracellular vesicles identifies

unique modulators of atherosclerosis and calcific aortic valve

stenosis. Circulation. 148:661–678. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yuan X, Sun L, Jeske R, Nkosi D, York SB,

Liu Y, Grant SC, Meckes DG Jr and Li Y: Engineering extracellular

vesicles by three-dimensional dynamic culture of human mesenchymal

stem cells. J Extracell Vesicles. 11(e12235)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang H, Deng B, Jiang Y, et al: Proteomic

analysis of cerebrospinal fluid exosomes derived from cerebral

palsy children. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research.

27:903–908. 2023.(In Chinese). https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/xdkf202306016.

|

|

26

|

Sheng J and Zhang WY: Identification of

biomarkers for cervical cancer in peripheral blood lymphocytes

using oligonucleotide microarrays. Chin Med J (Engl).

123:1000–1005. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Saleh M, Virarkar M, Javadi S, Elsherif

SB, de Castro Faria S and Bhosale P: Cervical cancer: 2018 revised

international federation of gynecology and obstetrics staging

system and the role of imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 214:1182–1195.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Tian Y, Gong M, Hu Y, Liu H, Zhang W,

Zhang M, Hu X, Aubert D, Zhu S, Wu L and Yan X: Quality and

efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation

methods by nano-flow cytometry. J Extracell Vesicles.

9(1697028)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wu T, Hu E, Xu S, Chen M, Guo P, Dai Z,

Feng T, Zhou L, Tang W, Zhan L, et al: clusterProfiler 4.0: A

universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation

(Camb). 2(100141)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chen H and Boutros PC: VennDiagram: A

package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler

diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics. 12(35)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Salib MY, Russell JHB, Stewart VR,

Sudderuddin SA, Barwick TD, Rockall AG and Bharwani N: 2018 FIGO

staging classification for cervical cancer: Added benefits of

imaging. Radiographics. 40:1807–1822. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ,

Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F,

Atkin-Smith GK, et al: Minimal information for studies of

extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of

the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of

the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles.

7(1535750)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Aguayo F, Perez-Dominguez F, Osorio JC,

Oliva C and Calaf GM: PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in HPV-driven

head and neck carcinogenesis: Therapeutic implications. Biology

(Basel). 12(672)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sacconi A, Muti P, Pulito C, Urbani G,

Allegretti M, Pellini R, Mehterov N, Ben-David U, Strano S, Bossi P

and Blandino G: Immunosignatures associated with TP53 status and

co-mutations classify prognostically head and neck cancer patients.

Mol Cancer. 22(192)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Khokhar M, Kartha P, Hassan S and Pandey

RK: Decoding dysregulated genes, molecular pathways and microRNAs

involved in cervical cancer. J Gene Med. 26(e3713)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Cao MX, Zhang WL, Yu XH, Wu JS, Qiao XW,

Huang MC, Wang K, Wu JB, Tang YJ, Jiang J, et al: Retraction Note:

Interplay between cancer cells and M2 macrophages is necessary for

miR-550a-3-5p down-regulation-mediated HPV-positive OSCC

progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40(310)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Park D, Kim H, Kim Y and Jeoung D: miR-30a

Regulates the expression of CAGE and p53 and regulates the response

to anti-cancer drugs. Mol Cells. 39:299–309. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Bhat AA, Thapa R, Afzal O, Agrawal N,

Almalki WH, Kazmi I, Alzarea SI, Altamimi ASA, Prasher P, Singh SK,

et al: The pyroptotic role of Caspase-3/GSDME signalling pathway

among various cancer: A Review. Int J Biol Macromol. 242 (Pt

2)(124832)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Shao X, Zheng Y, Huang Y, Li G, Zou W and

Shi L: Hsa-miR-221-3p promotes proliferation and migration in

HER2-positive breast cancer cells by targeting LASS2 and MBD2.

Histol Histopathol. 37:1099–1112. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kania EE, Carvajal-Moreno J, Hernandez VA,

English A, Papa JL, Shkolnikov N, Ozer HG, Yilmaz AS, Yalowich JC

and Elton TS: hsa-miR-9-3p and hsa-miR-9-5p as post-transcriptional

modulators of DNA topoisomerase IIα in human leukemia K562 cells

with acquired resistance to etoposide. Mol Pharmacol. 97:159–170.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Schoen C, Glennon JC, Abghari S, Bloemen

M, Aschrafi A, Carels CEL and Von den Hoff JW: Differential

microRNA expression in cultured palatal fibroblasts from infants

with cleft palate and controls. Eur J Orthod. 40:90–96.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Li M, Song J, Wang L, Wang Q, Huang Q and

Mo D: Natural killer cell-related prognosis signature predicts

immune response in colon cancer patients. Front Pharmacol.

14(1253169)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

West EE, Kolev M and Kemper C: Complement

and the regulation of T cell responses. Annu Rev Immunol.

36:309–338. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Afshar-Kharghan V: The role of the

complement system in cancer. J Clin Invest. 127:780–789.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Loh JT, Zhang B, Teo JKH, Lai RC, Choo

ABH, Lam KP and Lim SK: Mechanism for the attenuation of neutrophil

and complement hyperactivity by MSC exosomes. Cytotherapy.

24:711–719. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Shiels MS, Katki HA, Hildesheim A,

Pfeiffer RM, Engels EA, Williams M, Kemp TJ, Caporaso NE, Pinto LA

and Chaturvedi AK: Circulating inflammation markers, risk of lung

cancer, and utility for risk stratification. J Natl Cancer Inst.

107(djv199)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Zhang W, Yin Y, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Wang W,

Wang X, Ge Y, Liu B and Yao L: Relationship between vaginal and

oral microbiome in patients of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

and cervical cancer. J Transl Med. 22(396)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Nadif R, Mintz M, Jedlicka A, Bertrand JP,

Kleeberger SR and Kauffmann F: Association of CAT polymorphisms

with catalase activity and exposure to environmental oxidative

stimuli. Free Radic Res. 39:1345–1350. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Chen P, Zhong X, Song Y, Zhong W, Wang S,

Wang J, Huang P, Niu Y, Yang W, Ding Z, et al: Triptolide induces

apoptosis and cytoprotective autophagy by ROS accumulation via

directly targeting peroxiredoxin 2 in gastric cancer cells. Cancer

Lett. 587(216622)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Wan S, He QY, Yang Y, Liu F, Zhang X, Guo

X, Niu H, Wang Y, Liu YX, Ye WL, et al: SPARC Stabilizes ApoE to

Induce cholesterol-dependent invasion and sorafenib resistance in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 84:1872–1888. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Garcia-Arcos I, Park SS, Mai M,

Alvarez-Buve R, Chow L, Cai H, Baumlin-Schmid N, Agudelo CW,

Martinez J, Kim MD, et al: LRP1 loss in airway epithelium

exacerbates smoke-induced oxidative damage and airway remodeling. J

Lipid Res. 63(100185)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Shen S, Zhang S, Liu P, Wang J and Du H:

Potential role of microRNAs in the treatment and diagnosis of

cervical cancer. Cancer Genet. 248-249:25–30. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Song Y, Wang Z, He L, Sun F, Zhang B and

Wang F: Dysregulation of pseudogenes/lncRNA-Hsa-miR-1-3p-PAICS

pathway promotes the development of NSCLC. J Oncol.

2022(4714931)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

He L, Guo Z, Wang W, Tian S and Lin R:

FUT2 inhibits the EMT and metastasis of colorectal cancer by

increasing LRP1 fucosylation. Cell Commun Signal.

21(63)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Yang Y, Mao F, Guo L, Shi J, Wu M, Cheng S

and Guo W: Tumor cells derived-extracellular vesicles transfer

miR-3129 to promote hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by

targeting TXNIP. Dig Liver Dis. 53:474–485. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Wei W and Liu C: Prognostic and predictive

roles of microRNA-411 and its target STK17A in evaluating

radiotherapy efficacy and their effects on cell migration and

invasion via the p53 signaling pathway in cervical cancer. Mol Med

Rep. 21:267–281. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Fu K, Zhang L, Liu R, Shi Q, Li X and Wang

M: MiR-125 inhibited cervical cancer progression by regulating VEGF

and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. World J Surg Oncol.

18(115)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Yi Y, Liu Y, Wu W, Wu K and Zhang W: The

role of miR-106p-5p in cervical cancer: From expression to

molecular mechanism. Cell Death Discov. 4(36)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Weiss BG, Anczykowski MZ, Ihler F,

Bertlich M, Spiegel JL, Haubner F, Canis M, Küffer S, Hess J, Unger

K, et al: MicroRNA-182-5p and microRNA-205-5p as potential

biomarkers for prognostic stratification of p16-positive

oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 33:331–347.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Babion I, Miok V, Jaspers A, Huseinovic A,

Steenbergen RDM, van Wieringen WN and Wilting SM: Identification of

deregulated pathways, key regulators, and novel miRNA-mRNA

interactions in HPV-mediated transformation. Cancers (Basel).

12(700)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Cui G, Wang L and Huang W: Circular RNA

HIPK3 regulates human lens epithelial cell dysfunction by targeting

the miR-221-3p/PI3K/AKT pathway in age-related cataract. Exp Eye

Res. 198(108128)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Becker A, Thakur BK, Weiss JM, Kim HS,

Peinado H and Lyden D: Extracellular vesicles in cancer:

Cell-to-cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell. 30:836–848.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Dobrolecki LE, Airhart SD, Alferez DG,

Aparicio S, Behbod F, Bentires-Alj M, Brisken C, Bult CJ, Cai S,

Clarke RB, et al: Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models in basic

and translational breast cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

35:547–573. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Vendrov AE, Lozhkin A, Hayami T, Levin J,

Silveira Fernandes Chamon J, Abdel-Latif A, Runge MS and Madamanchi

NR: Mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic reprogramming induce

macrophage pro-inflammatory phenotype switch and atherosclerosis

progression in aging. Front Immunol. 15(1410832)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Sarwar MS, Cheng D, Peter RM, Shannar A,

Chou P, Wang L, Wu R, Sargsyan D, Goedken M, Wang Y, et al:

Metabolic rewiring and epigenetic reprogramming in leptin

receptor-deficient db/db diabetic nephropathy mice. Eur J

Pharmacol. 953(175866)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|