Introduction

Recently, breast cancer incidence has increased and

total mastectomy was common surgical method for breast cancer

patients (1). In total mastectomy,

it is generally common to place drains. Although early drain

removal can reduce the length of hospital stay, a meta-analysis

pointed out that the frequency of adverse events (AE) such as

seroma increases due to the early removal of drains (2). The meta-analysis indicates that AE

increase when the drain is removed early, in practice, each

facility decides on its own criteria for removal. Particularly,

removing the drain at 30-50 ml/d is a relatively common criterion

in view of the benefits and disadvantages (3-7).

However, it is undeniable that we aim for fewer complications and

early discharge. Therefore, ensuring a reliable improvement in

surgical techniques becomes one of the key factors.

Recent advancements in surgical devices have

facilitated the sealing of blood vessels and reduced the burden of

the surgeon. In Japan, under the health insurance system, energy

devices (EDs) can be employed in axillary dissection. This is based

on positive evidence on the use of devices such as the Harmonic

Focus® and LigaSure Exact Dissector®

(8,9). Using EDs to dissect mammary fat

tissue from the pectoralis major muscle during total mastectomy may

help reduce surgical complications, including seroma formation.

Dissection of the pectoralis fascia in total mastectomy involves a

wide area of the posterior wall of the mammary gland, which making

it likely to benefit from the use of ED. In this study, we aimed to

evaluate the amount of drainage and seroma incidence in patients

undergoing total mastectomy with pectoralis fascia dissection using

EDs.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a single-center, observational study, with

an exposure group comprising 41 consecutive patients with breast

cancer who underwent total mastectomy using an ED (Harmonic Focus

or LigaSure Exact) to separate breast fat tissue from the

pectoralis major muscle between January 1, 2020 and December 31,

2024. It is well known that breast cancer occurs predominantly in

women, while cases in men are rare. Therefore, all eligible cases

in this study are female. The historical control group comprised

117 consecutive patients who underwent total mastectomy for breast

cancer in Sapporo Medical University Hospital (Sapporo, Japan)

between January and December 2019, and conventional electrocautery

during chest wall dissection. A suction drain (5 mm SB VAC,

Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted in all cases. The

suction drain was removed when the daily drainage volume was

approximately <40 ml.

The surgical procedure for total mastectomy is

described below. Electrocautery was conventionally used for skin

flap dissection in both groups. In both groups, using an ED,

axillary dissection was performed from the lateral chest wall to

axillary levels I and II. In the exposure group, an ED was used for

all pectoralis fascia dissection procedures, separating breast

tissue from the pectoralis major muscle, whereas electrocautery was

used in the control group (Fig.

1). Four breast specialists with >10 years of experience

performed the surgeries.

The study outcomes were as follows: primary outcome,

total amount until drain removal; secondary outcomes, daily

drainage fluid output [postoperative days (POD) 1-10], operative

time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, and frequency of AEs

requiring intervention.

This study adhered to the ethical tenets of The

Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Principles for Medical

Research Involving Human Subjects. It was approved by the Clinical

Trial Center of Sapporo Medical University (approval number

352-93), and registered with UMIN-CTR (UMIN000056764). The need for

informed consent was waived owing to the observational nature of

this study. An opt-out consent process was used, with disclosures

made on the university website (https://web.sapmed.ac.jp/byoin/rinshokenkyu/koukai/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP17 (SAS

Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The unpaired Student s t-test

was used to compare the total amount of drain fluid, daily drainage

fluid output (postoperative days 1-10), operative time, blood loss,

and length of hospital stay between the ED and control groups. The

χ2 test or Fisher s exact test was used to analyze

cT stage (as a sequential variable) and the following nominal

variables: cN status (negative or negative), body mass index (BMI;

cutoff 25 kg/m2), prior chemotherapy, subtype, breast

surgery procedure (total mastectomy only), axillary surgery

procedure [axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) vs. sentinel lymph

node biopsy (SLNB)], and reconstructive surgery (presence or

absence). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Among these clinicopathological factors,

BMI, prior chemotherapy, and axillary surgery were treated as

covariates, and propensity score matching (PSM) was used to adjust

for these three factors. To identify independent factors associated

with AEs requiring intervention, a univariate analysis was

performed.

Results

Adjusting data using propensity score

matching

Patient characteristics and history for both groups

are listed in Table IA and B. As

shown in Table IA, key

characteristics included significantly higher BMI in the ED group

compared to the control group (P=0.0155), a higher proportion of

patients with prior preoperative chemotherapy (P=0.0001), and a

greater number of patients who had received ALND (P=0.0004). PSM

was performed using three parameters as covariates: BMI, presence

or absence of preoperative chemotherapy, and axillary surgery (ALND

vs. SLNB). The adjusted patient characteristics and history

post-PSM are summarized in Table

IB.

| Table IPatient characteristics before and

after PSM. |

Table I

Patient characteristics before and

after PSM.

| A, Before PSM |

|---|

| Characteristic | Total (%) | ED (%) | Control (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Sample size | 158 | 41 | 117 | - |

| Age, years | | | | 0.5120 |

|

<50 | 48 (30.4) | 12 (29.3) | 36 (30.8) | |

|

≥50 | 110 (69.6) | 29 (70.7) | 81 (69.2) | |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | | | | 0.0155 |

|

<25 | 113 (71.5) | 23 (56.1) | 90 (76.9) | |

|

≥25 | 45 (28.5) | 18 (43.9) | 27 (23.1) | |

| cT | | | | 0.6034 |

|

0-1 | 71 (44.9) | 17 (41.5) | 54 (46.2) | |

|

≥2 | 87 (55,1) | 24 (58.3) | 63 (53.8) | |

| cN | | | | 0.1803 |

|

0 | 56 (35.4) | 11 (26.8) | 45 (38.5) | |

|

≥1 | 102 (64.5) | 30 (73.2) | 72 (61.5) | |

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy | | | | 0.0001 |

|

Yes | 31 (19.6) | 17 (41.5) | 14 (12.0) | |

|

No | 127 (80.4) | 24 (58.5) | 103 (88.0) | |

| Axillary surgery | | | | 0.0004 |

|

SLNB | 105(66.5) | 18 (43.9) | 87 (74.4) | |

|

ALND | 53(33.5) | 23 (56.1) | 30 (25.6) | |

| Reconstruction | | | | >0.9999 |

|

Yes | 8 (5.1) | 2 (4.9) | 6 (5.1) | |

|

No | 150 (94.9) | 39 (95.1) | 111 (94.9) | |

| ER/HER2 status | | | | 0.1039 |

|

ER+/HER2- | 93 (58.9) | 27 (65.9) | 66 (56.4) | |

|

ER+/HER2+ | 17 (10.7) | 5 (12.2) | 12 (10.3) | |

|

ER-/HER2- | 14 (8.9) | 5 (12.2) | 9 (7.7) | |

|

ER-/HER2+ | 22 (13.9) | 1 (2.4) | 21 (17.9) | |

|

DCIS | 12 (7.6) | 3 (7.3) | 9 (7.7) | |

| LigaSure Exact

Dissector | | 24 (58.5) | | - |

| Harmonic Focus | | 17 (41.5) | | - |

| B, After PSM |

|

Characteristics | Total (%) | ED (%) | Control (%) | P-value |

| Sample size | 76 | 38 | 38 | - |

| Age, years | | | | 0.1687 |

|

<50 | 17 (22.4) | 11 (28.9) | 6 (15.8) | |

|

≥50 | 59 (77.6) | 27 (71.1) | 32 (84.2) | |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | | | | 0.8154 |

|

<25 | 45 (59.2) | 22 (57.9) | 23 (60.5) | |

|

≥25 | 31 (40.8) | 16 (42.1) | 15 (39.5) | |

| cT | | | | 0.1536 |

|

0-1 | 28 (36.8) | 17 (44.7) | 11 (29.0) | |

|

≥2 | 48 (63.2) | 21 (55.3) | 27 (71.0) | |

| cN | | | | 0.7975 |

|

0 | 21 (27.6) | 11 (28.9) | 10 (26.3) | |

|

≥1 | 55 (72.6) | 27 (7.1) | 28 (73.3) | |

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy | | | | 0.8106 |

|

Yes | 27 (35.6) | 14 (56.8) | 13 (34.2) | |

|

No | 49 (63.4) | 24 (63.2) | 25 (65.8) | |

| Axillary

surgery | | | | 0.6445 |

|

SLNB | 34 (44.7) | 18 (47.4) | 16 (42.1) | |

|

ALND | 42 (55.3) | 20 (52.6) | 22 (57.9) | |

| Reconstruction | | | | 0.4933 |

|

Yes | 2 (2.6) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | |

|

No | 74 (97.4) | 36 (94.7) | 38(100) | |

| ER/HER2 status | | | | 0.0391 |

|

ER+/HER2- | 43 (56.6) | 24 (64.3) | 19 (50.0) | |

|

ER+/HER2+ | 7 (9.2) | 5 (13.2) | 2 (5.3) | |

|

ER-/HER2- | 10 (13.1) | 5 (13.2) | 5 (13.1) | |

|

ER-/HER2+ | 11 (14.5) | 1 (2.6) | 10 (26.3) | |

|

DCIS | 3 (6.6) | 3 (7.6) | 2 (5.3) | |

| LigaSure Exact

Dissector | | 23 (60.5) | | - |

| Harmonic Focus | | 15 (39.5) | | - |

Surgical outcomes

As displayed in Table

II the mean total amount of drainage was 610 ml in the device

group and 812 ml in the control group, indicating a numerical

decrease without a statistically significant difference (P=0.1778).

No significant delay in operation time was observed with the use of

ED post-PSM [ED vs. control (mean ± standard deviation); 105±42 vs.

117±35 min; P=0.1960]. Moreover, no significant difference was

observed in the amount of bleeding (20±30 vs. 23±21 ml; P=0.6202),

POD of drain removal (7.3±2.7 vs. 7.9±3.3; P=0.3649), and length of

hospital stay (11.4±3.3 vs. 11.0±5.6 days; P=0.6737) post-PSM.

| Table IISurgical outcome. |

Table II

Surgical outcome.

| A, Surgical outcome

(before PSM) |

|---|

| Variable | Total | ED | Control | P-value |

|---|

| Sample size | 158 | 41 | 117 | - |

| Operation time,

min | 109±39 | 104±41 | 111±39 | 0.3619 |

| Estimated blood

loss, ml | 24±28 | 19±29 | 26±28 | 0.1557 |

| Total amount of

drainage, ml | 570±513 | 610±398 | 556±548 | 0.5137 |

| Post operation day

of drain removal, days | 6.7±2.3 | 6.8±2.4 | 6.7±2.3 | 0.8390 |

| Duration of

hospital stay, days | 10.8±3.8 | 11.3±3.2 | 10.6±4.0 | 0.2303 |

| All adverse events

incidence, n (%) | | | | 0.0957 |

|

Presence of

adverse events | 47 (29.7) | 8 (19.5) | 39 (33.3) | |

|

Absence of

adverse events | 111 (70.3) | 33 (80.5) | 78 (66.7) | |

| Adverse events

requiring intervention, n (%) | | | | 0.0675 |

|

Presence of

adverse events | 40 (25.3) | 6 (14.6) | 34 (29.1) | |

|

Absence of

adverse events | 118 (74.7) | 35 (85.4) | 83 (70.9) | |

| B, Details and

breakdown of AEs (before PSM) |

| Variable | Total | ED | Control | P-value |

| Sample size | 40 | 6 | 34 | |

| AEs | | | | >0.9999 |

|

Seroma, n

(%) | 32 | 6(100) | 26 (76.5) | |

|

Skin

necrosis, n (%) | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (5.9) | |

|

Hematoma, n

(%) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

|

Surgical

site infection, n (%) | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

|

Seroma +

infection, n (%) | 4 | 0 (0) | 4 (11.8) | |

|

Hematoma +

infection, n (%) | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| C, Surgical outcome

(after PSM) |

| Variable | Total | ED | Control | P-value |

| Sample size | 76 | 38 | 38 | - |

| Operation time,

min | 111±39 | 105±42 | 117±35 | 0.1960 |

| Estimated blood

loss, ml | 21±26 | 20±30 | 23±21 | 0.6202 |

| Total amount of

drainage, ml | 650±75 | 610±407 | 812±818 | 0.1778 |

| Post operation day

of drain removal, days | 7.1±2.4 | 6.8±2.4 | 7.5±2.3 | 0.1599 |

| Duration of

hospital stay, days | 11.6±4.6 | 11.4±3.3 | 11.9±5.6 | 0.6737 |

| All adverse events

incidence, n (%) | | | | 0.0805 |

|

Presence of

adverse events | 23 (30.3) | 8 (21.1) | 15 (39.5) | |

|

Absence of

adverse events | 53 (69.7) | 30 (78.9) | 23 (60.5) | |

| Adverse events

requiring intervention, n (%) | | | | 0.0372 |

|

Presence of

adverse events | 20 (26.3) | 6 (15.8) | 14 (36.8) | |

|

Absence of

adverse events | 56 (73.7) | 32 (84.2) | 24 (63.2) | |

| D, Details and

breakdown of AEs (after PSM) |

| | Total (%) | ED (%) | Control (%) | P-value |

| Sample size | 20 | 6 | 14 | |

| AEs | | | | >0.9999 |

|

Seroma, n

(%) | 17 (85.0) | 6(100) | 11 (78.6) | |

|

Skin

necrosis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

|

Hematoma, n

(%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

|

Surgical

site infection, n (%) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | |

|

Seroma +

infection, n (%) | 2 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 2 (14.3) | |

|

Hematoma +

infection, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

ED may reduce adverse events requiring

intervention and seroma incidence

The ED group had a significantly lower frequency of

AEs requiring intervention than the control group post-PSM [6/38

vs. 14/38 (15.4 vs. 36.8%); P=0.0372; Table II], although no difference was

observed between the two groups regarding all AE. Most AEs were

caused by seroma, with a smaller proportion attributed to

infection. In univariate analysis, the risk of AEs requiring

intervention was found to be reduced by the use of ED after PSM,

and there were no other confounding factors [OR 0.32, 95% CI

(0.10-0.93), P=0.0351; Table

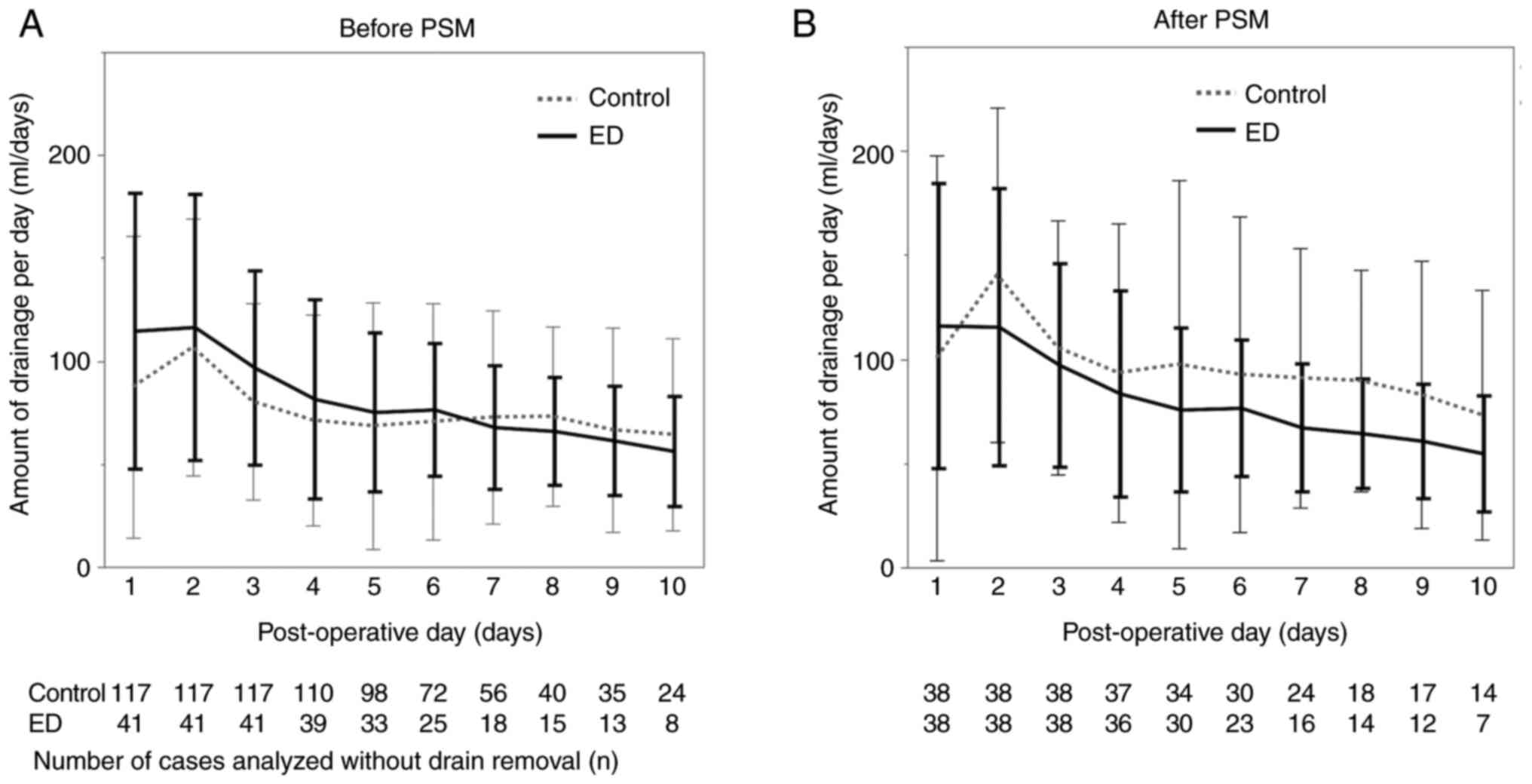

III]. Notably, the graph showing the average daily drainage

volume from POD 1 to POD 10 revealed a general downward trend in

drainage volume in the ED group after PSM. The drainage volume in

the ED group was markedly lower on POD 8 post-PSM (Fig. 2A and B).

| Table IIIUnivariate analysis for AE requiring

interventions. |

Table III

Univariate analysis for AE requiring

interventions.

| A, Before PSM |

|---|

| Variable | Factor | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | ≥50 vs. <50 | 2.51 | 1.07-6.63 | 0.0335 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | ≥25 vs. <25 | 1.09 | 0.51-2.29 | 0.8133 |

| cT | ≥2 vs. 0-1 | 1.14 | 0.56-2.38 | 0.7196 |

| cN | ≥1 vs. 0 | 0.89 | 0.42-1.90 | 0.7536 |

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy | Yes vs. no | 1.27 | 0.51-2.97 | 0.5998 |

| Axillary

surgery | ALND vs. SLNB | 1.26 | 0.59-2.65 | 0.5421 |

| ED/Control | With device vs.

without device | 0.42 | 0.15-1.02 | 0.0570 |

| B, After PSM |

| Variable | Factor | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age, years | ≥50 vs. <50 | 3.29 | 0.81-22.28 | 0.1001 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | ≥25 vs. <25 | 0.96 | 0.33-2.67 | 0.9333 |

| cT | ≥2 vs. 0-1 | 1.51 | 0.52-4.80 | 0.4554 |

| cN | ≥1 vs. 0 | 1.74 | 0.54-6.77 | 0.3633 |

| Neoadjuvant

chemotherapy | Yes vs. no | 1.72 | 0.60-4.93 | 0.3072 |

| Axillary

surgery | ALND vs. SLNB | 1.73 | 0.61-5.21 | 0.3042 |

| ED/Control | With device vs.

without device | 0.32 | 0.10-0.93 | 0.0351 |

The postoperative day of drain removal

correlates with the length of hospital stay

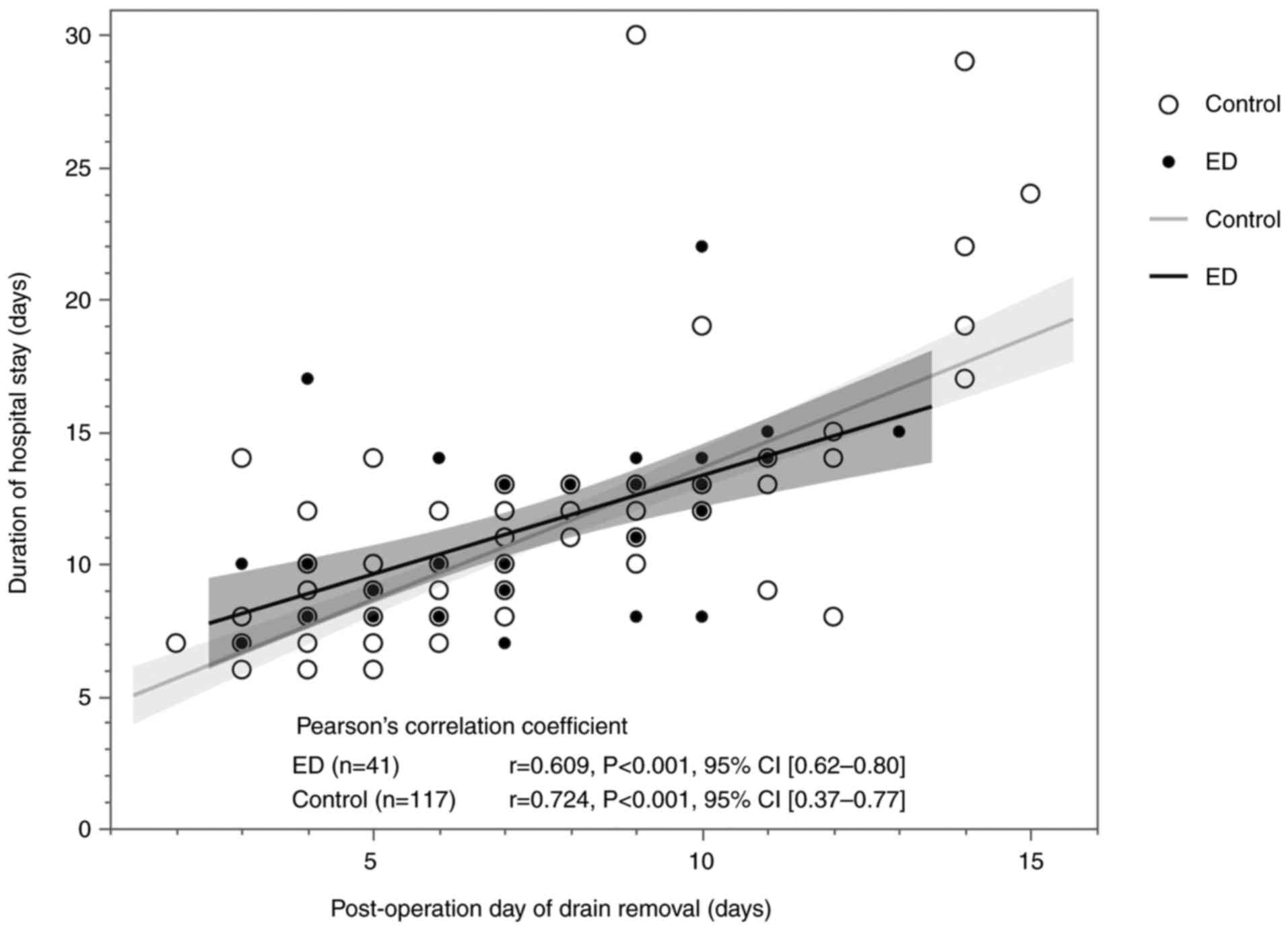

In this study, the Pearson s correlation

coefficient between the drain removal date and length of hospital

stay for the 158 cases analyzed was 0.701, indicating a positive

correlation between the two [95% CI (0.61-0.77)]. When divided into

the ED group (41 cases) and the control group (117 cases), the

respective coefficients were 0.609 and 0.724, with 95% CIs

(0.62-0.80) and (0.37-0.77). Both showed linear and positive

correlations (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study examined whether incorporating a simple

procedure to seal the pectoralis fascia using an ED could reduce

the amount of drainage and frequency of seroma formation. This

technique is considered straightforward as it involves exposing the

pectoralis muscle during fascia resection and sealing the

microscopic lymphatic vessels within the fascia. Two types of EDs

were used in this study. The first was the LigaSure Exact Dissector

(Covidien Japan, Tokyo, Japan), a radiofrequency ablation device

that coagulates tissue using Joule heat and separates it with an

integrated knife. A randomized controlled study indicated that

using this ED could reduce the time until drain removal and amount

of drainage (8). The second was

Harmonic Focus (Harmonic, Ethicon Inc., Johnson & Johnson,

Tokyo, Japan), an ultrasonic coagulation and dissection device that

uses friction heat engendered by ultrasonic vibrations of the

blade. A meta-analysis reported that its use reduces operating

time, bleeding volume, drainage volume, and hospital stay (9). Both devices are covered by health

insurance in Japan and are widely used in clinical practice.

Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis observed no significant

differences in complications between the two EDs (10), confirming their comparability.

The pectoralis major muscle is the largest muscle

covering the chest wall (11). In

Asians, who are generally smaller than Westerners, the average

width of the pectoralis major muscle was 11.6 cm (12). The extent to which the mammary

gland tissue is separated from the pectoralis major muscle during

total mastectomy depends on the patient s physique; however,

it tends to be extensive. Moreover, lymphatic vessels that

penetrate the pectoralis fascia are not as major a drainage route

as those flowing to the axilla or parasternal region, although

their existence has been documented (13). Therefore, sealing the pectoralis

major fascia may help reduce lymphatic fluid accumulation in the

dead space created during surgery. Overall, numerically the ED

group tended to have lower drainage volumes than the control group,

and a markedly difference was likely detected only on POD 8. On the

other hand, in the ED group, the timing of drains removal was

numerically earlier than the control group. A reduction in drainage

volume after the 8th postoperative day may allow for earlier drain

removal. Therefore, it is suggested that the discharge is possibly

showing a slight decrease, and indirectly leading to anticipated

improvements in clinical course. It is also expected to potentially

contribute to the reduction in length of stay discussed later.

In this study, AE incidence was significantly

reduced in the ED group compared with the control group. Notably,

seroma was the most common AE requiring postoperative intervention

(14,15). Furthermore, surgical site

infections and hematomas were not observed, and ED use may

potentially reduce their frequency. As for seroma, which are the

most common adverse events. With the increasing frequency of breast

cancer surgeries, ED use may help minimize AEs. This study

suggested that extensive sealing due to ED potentially reduces

exudate and decreases seroma formation. Moreover, no disadvantages

were observed in terms of intraoperative blood loss. In addition,

although breast surgeons accustomed to dissecting with

electrocautery may be concerned about the additional time when

using ED, the overall duration of surgery was not extended. Since

ED is a simple technique that can reduce seroma incidence without

any significant disadvantages, such as an increased operative time,

it has potential to reduce patient discomfort, follow-up visits,

and events requiring intervention for complications, while also

alleviate the workload of surgeons.

The precise mechanism by which energy devices reduce

seroma formation remains unclear, but it has been suggested that

they suppress lymphatic fluid retention by sealing vessels. Sealing

integrity of the ED in vessels up to 7 mm approximates the burst

strength of ligation and clips, resists dislodgement, and is

unaffected by proximal thrombus (16,17).

Further investigation of the mechanism is necessary.

Most healthcare organizations allow patients to be

discharged only after drain removal, making the length of hospital

stay closely tied to the duration of drain use (2). Some reports recommend that patients

can be discharged with the drain in places with appropriate support

or that they are seen monitored as outpatients after discharge

(6,18-20).

At our hospital, patients are typically discharged the day after

drain removal. Earlier drain removal was positively correlated with

a shorter hospital stay in this study, and suggests that earlier

drain removal due to the use of ED may reduce the length of

hospital stay, potentially improving healthcare system efficiency

and cost-effectiveness. However, it is also argued that discharge

often occurs due to non-clinical reasons such as social factors

rather than the patient s clinical course. Discharge protocols

vary across studies, contributing to significant heterogeneity

(2).

This study has some limitations. First, this was an

observational study conducted at a single institution with a small

number of patients. And the use of historical controls might have

introduced bias due to time differences. However, precisely because

it is a single-center study, usage and techniques are performed

according to consistent methods. The surgeries were performed by a

well-trained board-certified breast surgeon and the procedures

themselves have not changed significantly. Despite the small sample

size, a clear trend was observed, suggesting that minor adjustments

in surgical technique may help prevent seroma formation. Future

research should involve prospective observational studies across

multiple institutions. Based on the foundational data from this

study, we aim to conduct a multicenter study comparing the use of

ED across various sites, including the axilla and anterior

pectoralis major muscle. Second, the primary focus of this study

was on surgical outcomes rather than oncological outcomes,

necessitating future studies for a more comprehensive

understanding. Nevertheless, definitive oncological resection was

achieved in all patients, with no pathologically positive margins.

Additionally, compared with non-removal, resection of the

pectoralis major fascia remains essential as it significantly

lowers the recurrence rate in the chest wall (3).

In conclusion, this study suggests that using an ED

during pectoralis fascia dissection in total mastectomy may reduce

the AEs incidence requiring the intervention and the incidence of

seroma. This relatively simple procedure has the potential to

enhance the quality of breast surgery. Therefore, further

investigation into the applications of EDs is justified.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

HS conceived and planned the present study in

detail. YK, KS, AN and AW extracted the entirety of patient data,

performed the data acquisition and inputted the data into the data

platform. NN, SU, DK, TN and TM performed analysis and

interpretation of the patient data with HS. Additionally, DK and TN

revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual

content. TM provided overall supervision and gave final approval

for the publishable version. HS and TN confirm the authenticity of

all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study adhered to ethical tenets of The

Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Principles for Medical Research

Involving Human Subjects, was approved by the Clinical Trial Center

of Sapporo Medical University (approval number 352-93) and is

registered with UMIN-CTR (UMIN000056764). An opt-out consent

process was used, and disclosures were made on the

University s website (https://web.sapmed.ac.jp/byoin/rinshokenkyu/koukai/).

Patient consent for publication

An opt-out consent process was used, and disclosures

were made on the University s website (https://web.sapmed.ac.jp/byoin/rinshokenkyu/koukai/).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhang-Petersen C, Sowden M, Chen J, Burns

J and Sprague BL: Changes to the US preventive services task force

screening guidelines and incidence of breast cancer. JAMA Netw

Open. 7(e2452688)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Shima H, Kutomi G, Sato K, Kuga Y, Wada A,

Satomi F, Uno S, Nisikawa N, Kameshima H, Ohmura T, et al: An

optimal timing for removing a drain after breast surgery: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 267:267–273.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Dalberg K, Johansson H, Signomklao T,

Rutqvist LE, Bergkvist L, Frisell J, Liljegren G, Ambre T and

Sandelin K: A randomized study of axillary drainage and pectoral

fascia preservation after mastectomy for breast cancer. Eur J Surg

Oncol. 30:602–609. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ackroyd R and Reed MWR: A prospective

randomized trial of the management of suction drains following

breast cancer surgery with axillary clearance. The Breast.

6:271–274. 1997.

|

|

5

|

Gupta R, Pate K, Varshney S, Goddard J and

Royle GT: A comparison of 5-day and 8-day drainage following

mastectomy and axillary clearance. Eur J Surg Oncol. 27:26–30.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Peeters MJ, Kluit AB, Merkus JW and

Breslau PJ: Short versus long-term postoperative drainage of the

axilla after axillary lymph node dissection. A prospective

randomized study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 93:271–275.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Seenivasagam RK, Gupta V and Singh G:

Prevention of seroma formation after axillary dissection-a

comparative randomized clinical trial of three methods. Breast J.

19:478–484. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Seki T, Hayashida T, Takahashi M, Jinno H

and Kitagawa Y: A randomized controlled study comparing a vessel

sealing system with the conventional technique in axillary lymph

node dissection for primary breast cancer. Springerplus.

5(1004)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Cheng H, Clymer JW, Ferko NC, Patel L,

Soleas IM, Cameron CG and Hinoul P: A systematic review and

meta-analysis of Harmonic technology compared with conventional

techniques in mastectomy and breast-conserving surgery with

lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press).

8:125–140. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Alharran AM, Alenezi YY, Hammoud SM,

Alshammari B, Alrashidi M, Alyaqout FB, Almarri A, Alharran YM,

Alazemi MH, Allafi F and Al*Sadder KA: Efficacy of ligasure versus

harmonic devices in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 16(e57478)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gruber RP, Kahn RA, Lash H, Maser MR,

Apfelberg DB and Laub DR: Breast reconstruction following

mastectomy: A comparison of submuscular and subcutaneous

techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 67:312–317. 1981.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Baek WY, Byun IH, Kim YS, Jung BK, Yun IS

and Roh TS: Variance of the pectoralis major in relation to the

inframammary fold and the pectoralis minor and its application to

breast surgery. Clin Anat. 30:357–361. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cieśla1 S, Wichtowski M, Poźniak-Balicka R

and Murawa D: The surgical anatomy of the mammary gland:

Vascularization, innervation, lymphatic drainage, the structure of

the axillary fossa (part 2.). J Oncol. 71:62–69. 2021.

|

|

14

|

He XD, Guo ZH, Tian JH, Yang KH and Xie

XD: Whether drainage should be used after surgery for breast

cancer? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med

Oncol. 28 (Suppl 1):S22–S30. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Droeser RA, Frey DM, Oertli D, Kopelman D,

Peeters MJ, Giuliano AE, Dalberg K, Kallam R and Nordmann A:

Volume-controlled vs no/short-term drainage after axillary lymph

node dissection in breast cancer surgery: A meta-analysis. Breast.

18:109–114. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kennedy JS, Stranahan PL, Taylor KD and

Chandler JG: High-burst-strength, feedback-controlled bipolar

vessel sealing. Surg Endosc. 12:876–878. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Timm RW, Asher RM, Tellio KR, Welling AL,

Clymer JW and Amaral JF: Sealing vessels up to 7 mm in diameter

solely with ultrasonic technology. Med Devices (Auckl). 7:263–271.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Parikh HK, Badwe RA, Ash CM, Hamed H,

Freitas R Jr, Chaudary MA and Fentiman IS: Early drain removal

following modified radical mastectomy: a randomized trial. J Surg

Oncol. 51:266–269. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kopelman D, Klemm O, Bahous H, Klein R,

Krausz M and Hashmonai M: Postoperative suction drainage of the

axilla: For how long? Prospective randomised trial. Eur J Surg.

165:117–120. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Clegg-Lamptey JN, Dakubo JC and Hodasi WM:

Comparison of four-day and ten-day post-mastectomy passive drainage

in Accra, Ghana. East Afr Med J. 84:561–565. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|