Introduction

While the majority of human neurons are generated

prenatally, substantial neuronal growth, remodeling and

differentiation continue during the first 2 years of life (1-3).

Postnatal neurogenesis in humans is largely confined to the

subventricular zone; however, protracted neuronal migration occurs,

notably within the cerebral cortex and cerebellum, which are

regions crucial for learning and motor coordination (4). In preterm infants, premature exposure

to the extrauterine environment disrupts the typical trajectory of

neuronal maturation. This disruption affects all stages of neuronal

development, increasing the risk of long-term neurodevelopmental

and behavioral disorders. Individual resilience to these risks

varies and may be enhanced by early interventions (5,6).

Regardless of gestational age at birth, neonatal

hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) represents a severe

complication. HIE is a form of brain injury resulting from

perinatal oxygen deprivation and reduced cerebral blood flow. It is

a leading cause of neonatal brain damage, with an estimated

incidence of 2-3 per 1,000 live births in developed countries

(7-9). At

the molecular level, HIE initiates a cascade of cellular events,

including energy failure, glutamate excitotoxicity, calcium

overload and oxidative stress, collectively contributing to

neuronal injury. Secondary inflammation and apoptosis further

exacerbate this damage, highlighting the complex pathophysiology of

HIE (10).

Among the various strategies evaluated to mitigate

perinatal brain injury, including erythropoietin, stem cell

therapies and melatonin, therapeutic hypothermia has exhibited the

most consistent clinical efficacy. Cooling the body to 32-34˚C

decelerates the metabolic processes and attenuates key pathological

mechanisms, such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

Consequently, therapeutic hypothermia is widely considered the

standard of care for infants with moderate to severe HIE,

significantly reducing mortality (11-13).

Furthermore, hypothermia has been shown to improve

neurodevelopmental outcomes (14-16).

While previous research has primarily focused on the

effects of hypothermia on mature neurons exposed to hypoxia, its

effects on neurons at various stages of maturation, including those

not directly affected by oxygen deprivation, are less well

understood. Given that the neonatal brain, particularly in preterm

infants, contains a substantial population of immature neural

cells, the response of these cells to both hypothermic and

hyperthermic conditions represents a critical area of

investigation. The present study investigated the effects of

temperature modulation (hypothermia and hyperthermia) on neurons at

different stages of maturation. Using a well-established neural

stem cell model at various differentiation stages, previously

validated in several publications (17-19),

the present study examined the differential responses of immature

and mature neurons to short-term hypothermia. The findings

presented herein provide novel insight into how neural cells at

different developmental stages respond to environmental stressors,

with implications for optimizing therapeutic strategies for

neonatal brain injury.

Materials and methods

Isolation and differentiation of

neural stem cells

The neural stem cells used in the present study were

obtained from the bank of the Laboratory for Stem Cells (School of

Medicine, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia). No additional

animals were sacrificed for the purposes of the present study.

Isolation procedure, performed in the Laboratory for Stem Cells and

described in some of the authors' previous publications (17-19),

included 14.5-day-old C57/BL6 albino mouse embryos. They were

obtained by mating 3-4-month-old animals. After confirming

pregnancy, on day 14, the animals were sacrificed by cervical

dislocation. After opening the abdominal cavity and isolating

embryos from the uterine wall, embryos were first separated from

the amniotic layer and their telencephalic wall was then cut into

small sections prior to exposure to the digestive enzymes. Cells

were grown in proliferation medium which contained 1% N2

(17502-048, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 1% Pen/Strep

(penicillin/streptomycin, 5,000 U/ml; 15070063, Gibco, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 2% B27 (17502, Gibco, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), 20 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF; PMG8041,

Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast

growth factor (bFGF; PMG0035, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and 5 mM HEPES (H0887, MilliporeSigma). After a sufficient

number of cells was obtained, which was usually in the range of 2-5

million, their differentiation was achieved in the plates covered

with 50 µg/ml poly-D-lysin (PDL; P6407, MilliporeSigma) and 10

µg/ml laminin (L2020, MilliporeSigma). Differentiation medium,

which induced the differentiation of immature cells into neurons,

was comprised of 1% N2, 1% Pen/Strep, 1% FBS (15070063, Gibco,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 2% B27+ (A3582801, Gibco, Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 5 mM HEPES. The use of these cells was

already described and validated in previous publications (17-19).

After obtaining neural stem cells by the enzymatic

dissection of the neutrospheres, cells attached on coated

coverslips were grown in an incubator up to 14 days. Of note, five

different groups of each maturity stage were formed, which

corresponded to following temperatures: 32, 30 and 28˚C (three

groups of hypothermia), 39˚C (hyperthermia, and the control group

(37˚C). These temperatures were selected on the basis of clinical

experience with applied hypothermia protocols (12-16).

The temperature of 39˚C was selected as an average hyperthermic

value in pathological conditions. After being exposed to the

specific temperature for 48 h, the cells were prepared for staining

and immunocytochemistry. In this manner, there were three groups of

cells with various levels of maturity [day 2, early progenitors

(exposed to different temperatures from day 0 to 2); day 7, mid

progenitors (exposed to different temperatures from day 5 to 7);

and day 14, late progenitors (exposed to different temperatures

from day 12 till day 14)].

Cell counting

After plating the cells at a density of 50,000 cells

per well, four wells were used for counting, with three different

fields of view counted in each well. Thus, a total of 12 counts

were made for each condition tested. Prior to counting, the cells

were examined using the LIVE/DEAD Viability/Cytotoxicity kit

(L3224, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), which enabled the

recognition of living cells only.

Immunocytochemistry

To follow up on cell differentiation and analyze the

cells using immunocytochemistry, the cells were grown on coverslips

and fixed in 4% PFA (Merck KGaA). Fixation at 4˚C lasted for 10

min. Permeabilization of the cell membranes was performed using

0.2% Triton (Merck KGaA) in PBS for 15 min. Subsequently, the cells

were washed with PBS. Blocking was performed with 3% goat serum in

PBS at room temperature for 2 h. The primary antibodies used were

anti-Nestin (1:100; cat. no. MAB353, Merck KGaA) and

anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 (Map2; 1:5,000; cat. no.

ab5392, Abcam). After the primary antibodies had attached to their

antigens, the cells were washed with PBS. The secondary antibodies

were then added and the cells were incubated at room temperature

with the secondary antibody for 1 h. The secondary antibody used

were the following: goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor™ 488

(1:1,000; cat. no. A11001, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and goat

anti-chicken IgG (H+L), Alexa Fluor™ 546 (1:1,000; cat. no. A11040,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For the counterstain procedure,

1:20,000 DAPI (Roche 10236276001, Merck KGaA) at room temperature

was used.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the

commercial QIAshredder (79656, Qiagen, Inc.) and the RNeasy Mini

kit (74104, Qiagen, Inc.). The RNA concentration was quantified

using a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The concentration of RNA for all samples was

adjusted to 25 ng/µl. The conversion from RNA to cDNA was

accomplished utilizing a high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (4387406,

Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). qPCR was then

performed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays for three genes of

interest: Neural cell adhesion molecule 1 (Ncam1; Mm01149710_m1,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), integrin beta-1 (Itgb1;

Mm01253230_m1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and cadherin-2

(Cdh2; Mm01162497_m1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). As

housekeeping genes, β-actin (Mm02619580_g1, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1

(Hprt1; Mm03024075_m1, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were used.

The relative quantification was performed using the

2-ΔΔCq method (20).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in R Studio

version 1.4.1717 (Posit PBC). Comparisons between groups were made

using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's Honest Significant

Difference (HSD) post hoc test. A value of P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

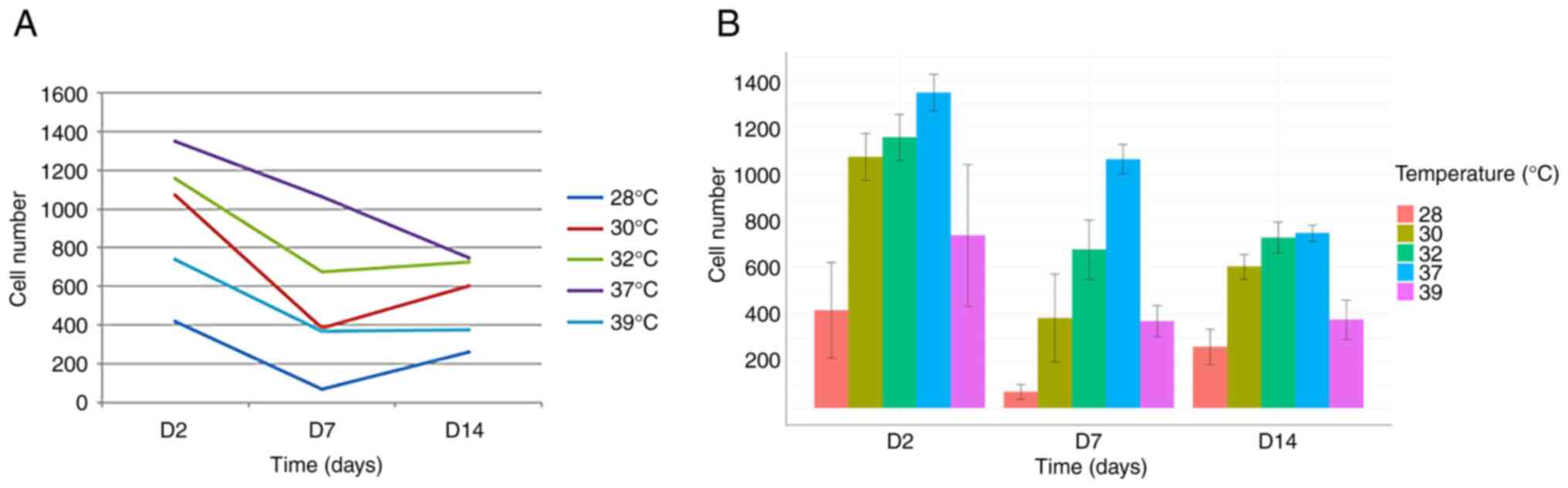

Short-term exposure to hypothermia has

more detrimental effects on early- and mid-stage than on late-stage

neural precursors

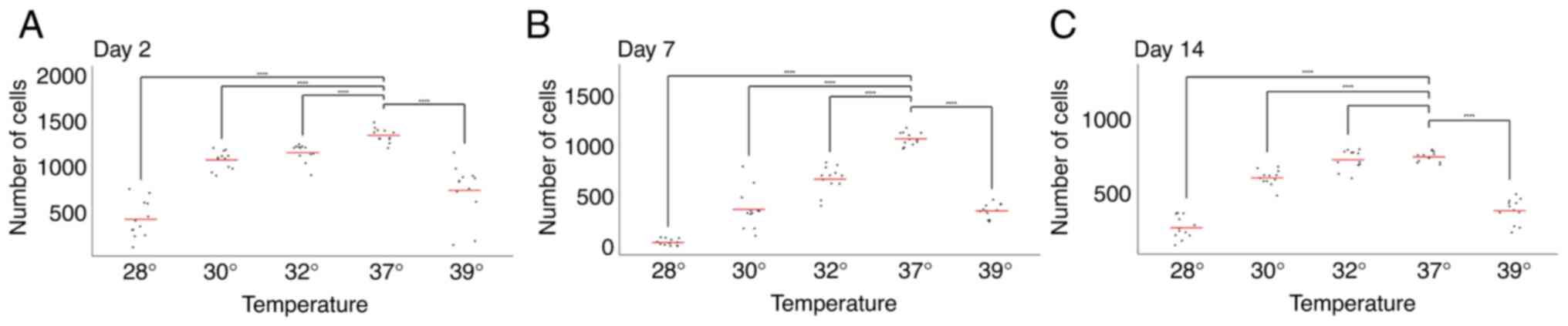

To investigate the effects of neuronal precursor

maturation stage and temperature on cell numbers, the cells were

exposed to various temperatures for 48 h on days 0, 5 and 12 of

maturation. Cell counts were then performed on days 2, 7 and 14.

This allowed for the comparison of the effects of temperature

exposure at different maturation stages on cell number.

The comparison of cell numbers at a physiological

temperature (37˚C) revealed a decline in cell numbers between days

2, 7 and 14, consistent with previous observations by our group

(17-19)

(Figs. 1 and 2).

The analysis of the day 7 time point revealed an

accelerated rate of decline in cell numbers following exposure to

both hypothermia (at all temperatures tested) and hyperthermia.

This suggests that cells exposed to temperature changes between

days 5 and 7 responded negatively, resulting in a more pronounced

reduction in cell numbers compared to days 2 and 14 (Figs. 1 and 2).

Conversely, and notably, the opposite effect was

observed on day 14. Under all three hypothermic conditions (32, 30

and 28˚C), cell numbers on day 14 exceeded those on day 7 (Figs. 1 and 2). This strongly suggests a beneficial

effect of hypothermia on cell numbers when applied between days 12

and 14. Furthermore, no significant difference in cell number was

observed on day 14 between cells grown at 37˚C and those exposed to

32˚C (Fig. 2).

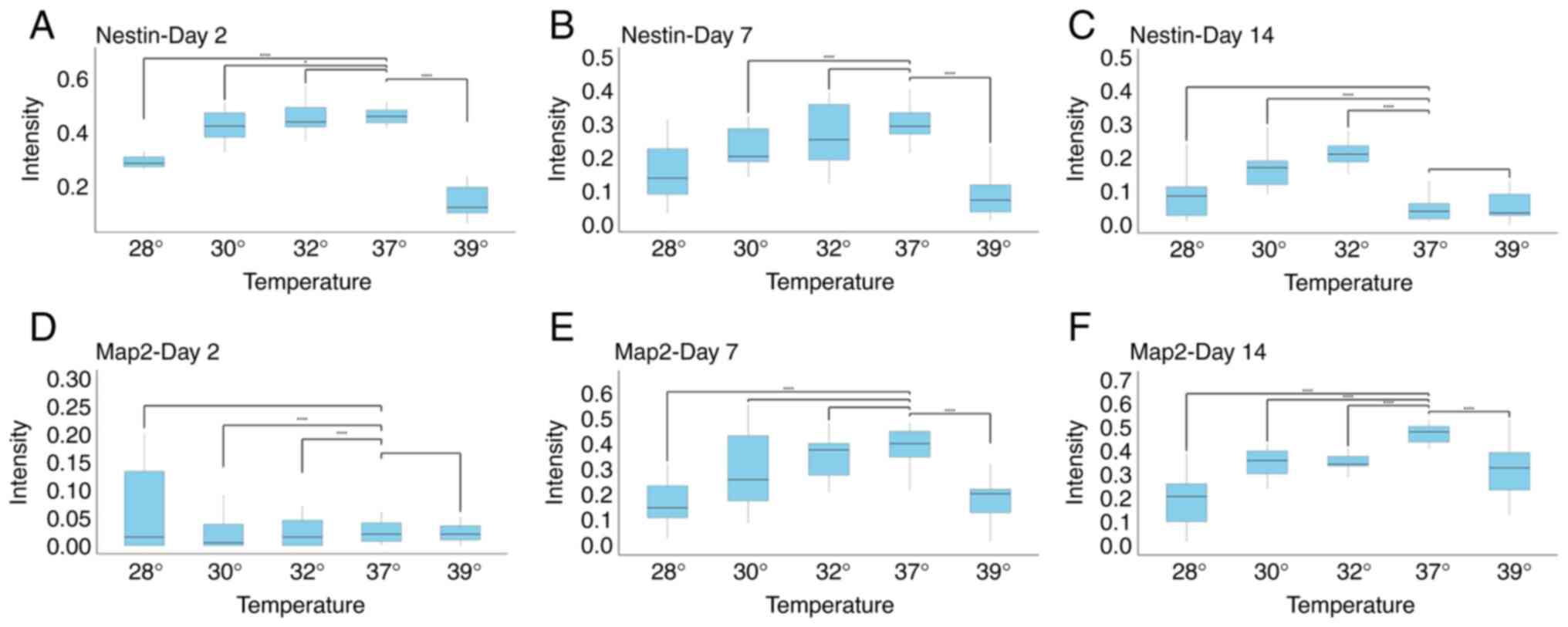

The expression of Nestin and Map2,

markers of differentiation of neurons, is dependent on the

temperature and maturity of cells following exposure to

hypothermia

To investigate whether changes in temperature

influence the expression of markers of neural precursors maturity,

the expression levels of Nestin and Map2 were analyzed. As was

expected, neural precursors at day 2, and to a lesser extent, at

day7, expressed Nestin, while this marker was almost completely

absent on day 14 (Figs. 3 and

4). When early precursors were

exposed to hypothermia, the expression of Nestin was not markedly

altered, apart from the condition of the extreme change of

temperature to 28˚C. However, given that the majority of cells at

28˚C were either dead or exhibiting signs of cell death, this

finding probably reflects a severe impairment in cell metabolism.

Notably, hyperthermia also caused a marked decrease in the

expression of Nestin. A similar finding was observed on day 7,

where all changes in temperatures decreased the expression of

Nestin. On the other hand, the opposite and surprising finding was

observed on day 14. While cells at D14 normally no longer expressed

Nestin, decreasing the temperature to 32˚C and to a lesser extent,

to 30˚C, markedly increased Nestin expression (Figs. 3 and 4).

The analysis of Map2 expression revealed the

following: As was expected, Map2 expression was not detected in the

earliest stage of neural precursors, and temperature changes did

not affect this. At day 7, decreasing the temperature to 32˚C did

not influence Map2 expression. A reduction in Map2 levels was

observed only at more extreme temperatures, consistent with the

findings obtained for Nestin expression. At day 14, both decreases

and increases in temperature reduced Map2 expression. Notably, even

a decrease to 32˚C reduced Map2 levels, coinciding with a marked

increase in Nestin expression at the same differentiation stage

(Figs. 3 and 4).

A comparison of all three stages of neuronal

maturity revealed that at days 2 and 7, either no significant

changes were observed, or a decrease in marker expression was

observed, generally being associated with extreme temperature

changes, and thus likely representing non-specific effects. At day

14, however, a temperature of 32˚C decreased Map2 levels, but

increased Nestin levels, suggesting a form of dedifferentiation

(Figs. 3 and 4). This coincides with the observation that

cell numbers at day 14 did not significantly differ between 37˚ and

32˚C (Fig. 2).

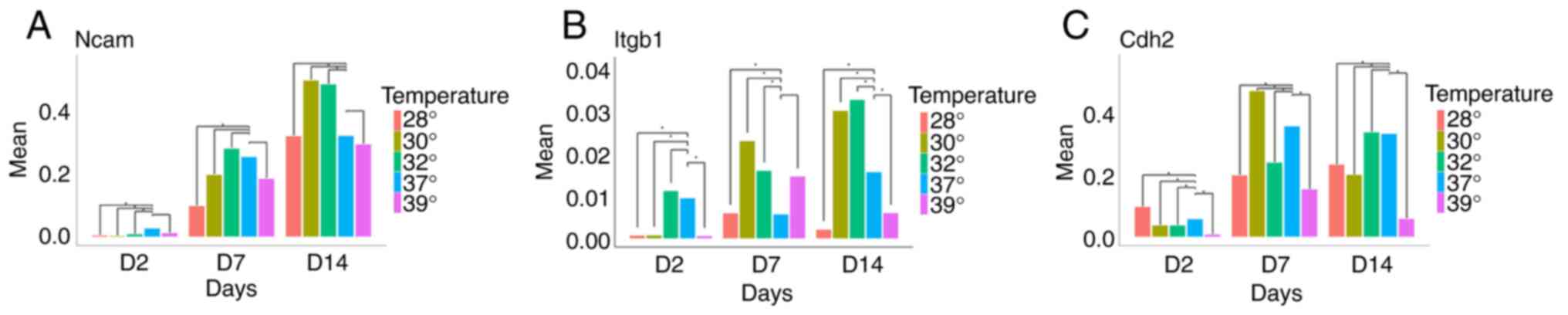

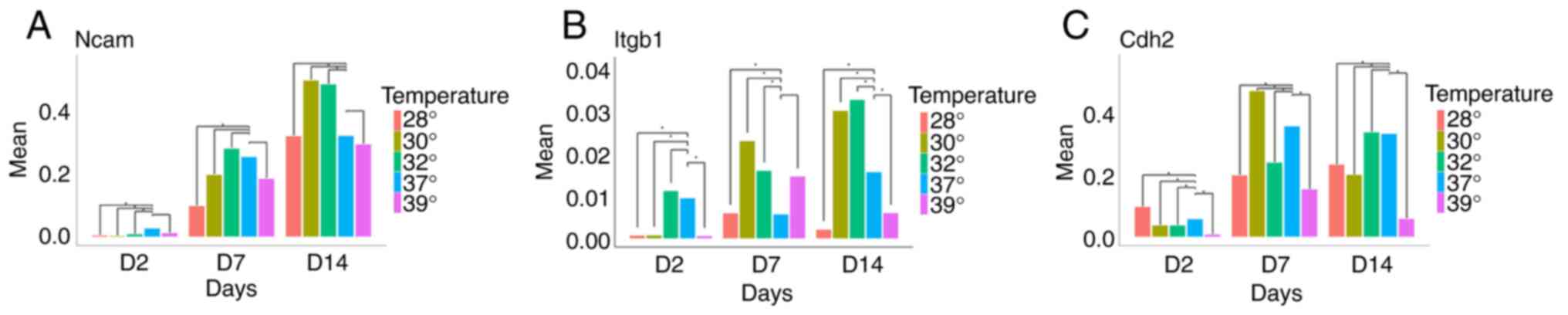

Hypothermia increases the expression

of genes linked to neuronal plasticity and migration

Having observed that temperature changes influence

both cell survival and the expression of genes associated with the

differentiation stage, the present study then investigated the

effects of hypothermia and hyperthermia on the expression of genes

related to migration, differentiation, plasticity and regeneration.

While Ncam1 was barely detectable in early progenitors, cells at

days 7 and 14 strongly expressed this gene. Of note, although

temperature changes did not significantly alter Ncam1 expression at

day 7, mild hypothermia (32 and 30˚C) significantly increased Ncam1

expression at day 14 (Fig. 5A).

| Figure 5Expression of (A) Ncam1, (B) Itgb1

and (C) Cdh2 at days 2, 7 and 14, in five different temperature

conditions. (A) When compared to normothermia, it noteworthy that

an increase in Ncam expression was observed following exposure to

mild hypothermia on day 14. (B) A similar finding, including on day

7 as well, was found for Itgb1. (C) Cdh2 expression exhibited a

different pattern, with an increase in its expression observed only

on day 7 when the cells were exposed to 30˚C.

*P<0.01. Ncam, Neural cell adhesion molecule 1;

Itgb1, integrin beta-1; Cdh2, cadherin-2. |

Another gene examined was Itgb1. It was found that

temperatures of 32 and 30˚C increased Itgb1 expression at both days

7 and 14, whereas more extreme hypothermia (28˚C) and hyperthermia

reduced its expression (Fig.

5B).

The analysis of Cdh2 expression revealed a

significant increase only at day 7 when cells were cultured at

30˚C. In all other conditions, a decrease in Cdh2 expression was

observed (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

Therapeutic hypothermia represents a promising

intervention for mitigating neonatal brain injury resulting from

HIE. By reducing the core body temperature of infants to 32-34˚C

for 24 to 72 h, hypothermia decreases metabolic demand and

attenuates secondary injury cascades, including inflammation and

apoptosis (21). Clinical trials

have demonstrated improved survival rates and a reduced risk of

severe neurodevelopmental disabilities in term and late preterm

infants. However, its efficacy is time-dependent, with maximal

benefits observed when initiated within 6 h of birth. Current

guidelines recommend hypothermia as the standard of care for

moderate to severe HIE in term and near-term infants; however, its

use in mild HIE, preterm infants and resource-limited settings

remains a subject of ongoing investigation (22). From a molecular and

pathophysiological perspective, hypothermia has been shown to

inhibit excitotoxicity by reducing glutamate release, thereby

preventing excessive calcium influx and subsequent cell death

(21). It also downregulates

inflammatory pathways, suppressing the release of pro-inflammatory

cytokines implicated in cell damage and apoptosis. Regarding

apoptosis, or programmed cell death, hypothermia attenuates caspase

activation, the enzymatic process responsible for apoptosis

(23).

However, the neonatal nervous system, particularly

in preterm infants, comprises a heterogeneous population of cells

at various stages of maturation. It is therefore plausible that not

all cell types are equally susceptible to hypoxic injury.

Furthermore, some preterm infants may not experience hypoxia at

all, yet hypothermia may be considered a prophylactic intervention

to enhance survival prospects. Consequently, the present study

investigated the effects of temperature modulation on normoxic

cells at different developmental stages. To the best of our

knowledge, data regarding the impact of temperature changes on such

a broad spectrum of cell types are limited. Therefore, the present

study compared the responses of cells at three distinct

differentiation stages, unexposed to hypoxic insults, to

temperature variations. Notably, deviations from the physiological

temperature of 37˚C generally reduced cell numbers. However, the

experimental design used herein yielded a key observation: While

early- and mid-stage neural precursors exhibited negative responses

to both hypothermia and hyperthermia, a distinct benefit was

observed at day 14. Under all hypothermic conditions tested, the

number of viable cells at day 14 exceeded that at day 7.

Furthermore, no significant difference in viable cell numbers was

detected between cells cultured at 37 and 32˚C at day 14. This

indicates that only at day 14, and only with mild hypothermia

(32˚C), were detrimental effects on neural precursors absent. This

finding was further investigated by examining the expression of

Nestin, a marker of immature cells, and Map2, a marker of mature or

nearly mature neurons. Again, late-stage neural precursors

displayed a unique response: Mild hypothermia reduced Map2

expression, while simultaneously increasing Nestin expression. This

increase in Nestin expression was the sole increase observed in

this aspect of the study. Nestin, an intermediate filament protein,

is predominantly expressed in stem and progenitor cells during

development, particularly within the central nervous system, muscle

and other tissues. It is a widely accepted marker for neural stem

cells (NSCs) and other multipotent stem cells (24). An elevated expression of Nestin is

also observed in reactive astrocytes and other glial cells

following central nervous system injury, such as stroke or

traumatic brain injury. Notably, Nestin-expressing neurons have

been identified in both rats and humans, suggesting that even

mature neurons can, under certain conditions, express this protein

(25). Moreover, there is evidence

to indicate that increasing the expression of Nestin in both

neurons and astrocytes contributes to the improved survival of

neural tissue affected by pathological condition (26).

Map2 is a protein localized to dendrites and

interacts with microtubules, the primary structural filaments of

neurons. An increased expression of Map2 in neural precursors is a

key indicator of terminal differentiation. Consequently, it has

been demonstrated that Map2 inhibition is associated with a reduced

rate of differentiation and the maintenance of mitotic capacity

(27). The expression of Map2 is

known to be modulated by various external factors (28). Moreover, decreased expression of Map2

has been reported in certain pathological conditions (29). The dichotomy regarding the effects of

hypothermia on Map2 expression centers on whether a reduced

expression of Map2 signals neuroprotection or impaired neuronal

maturation. On the one hand, hypothermia has been shown to

attenuate the injury-induced loss of Map2, suggesting the

preservation of late-stage neural precursors and contributing to

neuroprotection after trauma (30).

On the other hand, Map2 is critical for dendritic outgrowth,

microtubule stabilization and synaptic plasticity; thus, its loss

or reduced expression can reflect impaired maturation and

pathological dendritic morphology, as observed in various

neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders (29). Thus, while the decreased expression

of Map2 under hypothermia may indicate preserved neuronal

integrity, a decrease in Map2 expression more broadly could also

signify disrupted neuronal development and function. This dual

interpretation highlights the complexity of Map2 as both a marker

and mediator of neuronal health, where context and timing of

expression changes are key to understanding its role.

Given the findings of the present study suggesting

that mild hypothermia may postpone the terminal differentiation of

neurons and enhance their regenerative potential, the present study

investigated the expression of three genes implicated in these

processes. Ncam1, widely expressed in neural tissue, is involved in

neural stem cell adhesion, migration and differentiation. It plays

a crucial role in neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity (31). Generally, Ncam1 upregulation promotes

cell adhesion, neural plasticity and migration (32-34).

The finding of the present study that mild hypothermia increases

Ncam1 expression at day 14 is consistent with the observed increase

in Nestin expression and a decrease in Map2 expression, as these

changes collectively suggest reduced terminal differentiation and

an enhanced capacity for regenerative processes. Itgb1 is a

molecule involved in guiding neurons to their appropriate locations

during brain development. Furthermore, it participates in neuronal

adhesion and migration (35-37).

Very similar to Ncam1, the finding of the present study that mild

hypothermia increases Itgb1 expression at days 7 and 14 is

consistent with the observed increase in Nestin expression and a

decrease in Map2 expression. All these changes collectively suggest

reduced terminal differentiation and an enhanced capacity for

regenerative processes. Cdh2 is a cell adhesion molecule highly

expressed in neural tissues. It plays a crucial role in maintaining

the neural stem cell niche and influencing NSC differentiation,

migration, and synapse formation (38). Unlike Ncam1 and Itgb1, hypothermia

did not exert a consistent effect on Cdh2 expression; some

temperatures increased and others decreased its expression.

Clearly, additional mechanisms are involved in this molecular

pathway, and further investigations are required to elucidate these

complex interactions.

Regardless of that, it was clearly demonstrated that

Ncam1 and Itgb1 play crucial roles in neural stem cell migration

and neurite extension. When upregulated, these molecules enhance

cellular mobility and neurite formation, while their downregulation

produces opposite effects. The mechanistic elements of these

phenomena are well-described (39).

In addition, it has been reported that hypothermia leads to an

enhanced neurite extension in mouse brain slice cultures, which is

mediated by a surge in TNF-α levels (40). Moreover, a previous in vivo

study on rat spinal cord injury found that hypothermia plus NSC

transplantation tended to promote graft migration: The combined

therapy may promote migration of the transplanted cells at the

injury site (41).

While it is known that the use of mice as an animal

model and mouse cells are still often used in neuroscience, certain

possible limitations of the present study should be mentioned.

Mouse NSCs are widely used as models of human neural tissue due to

broad genetic and cellular similarities; however, critical

species-specific differences can limit their translational

relevance (42). Moreover,

comparative transcriptomic research has found that a number of

orthologous genes exhibit divergent expression or splicing patterns

in mouse vs. human neural cells (43). Developmental timelines also markedly

differ: Human neurodevelopment is far more prolonged and complex

than that in mice; thus, equivalent developmental stages do not

align. In other words, the results of the present study are very

useful; however, for further progress, more advanced, human brain

organoid models, for example, such as the ones previously reported

(44) should be used.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the Croatian Ministry

of Science, Education and Youth as part of a project entitled

‘Development of personalized tests for biological brain age and

early detection of dementia-BrainClock’ (grant reference no.

NPOO.C3.2.R3-I1.04.0089). The study was additionally supported by

the Croatian Science Foundation, project DevDown, under the project

no. IP-2022-10-4656.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LDM and DM were involved in the conceptualization of

the study and in the writing of the manuscript. LDM and EEP were

involved in the study methodology. LDM, EEP, AEH and DM were

involved in data validation, formal analysis and data

investigation, as well as in the writing, reviewing and editing of

the manuscript. DM provided resources (all chemicals, kits, plastic

and other expendables). DM also supervised the study, and was

involved in project administration and funding acquisition. LDM and

DM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The neural stem cells used in the present study were

obtained from the bank of the Laboratory for Stem Cells (School of

Medicine, University of Zagreb). No additional animals were

sacrificed for the purposes of the present study. The procedure by

which cells were obtained and used was approved by the Ethical

Board of the School of Medicine (approval no.

380-59-10106-17-100/27).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gilmore JH, Knickmeyer RC and Gao W:

Imaging structural and functional brain development in early

childhood. Nat Rev Neurosci. 19:123–137. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Mrzljak L, Uylings HB, Van Eden CG and

Judás M: Neuronal development in human pre-frontal cortex in

prenatal and postnatal stages. Prog Brain Res. 85:185–222.

1990.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Landing BH, Shankle WR, Hara J, Brannock J

and Fallon JH: The development of structure and function in the

postnatal human cerebral cortex from birth to 72 months: Changes in

thickness of layers II and III correlate to the onset of new

age-specific behaviors. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med. 21:321–342.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sanai N, Nguyen T, Ihrie RA, Mirzadeh Z,

Tsai HH, Wong M, Gupta N, Berger MS, Huang E, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et

al: Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their

decline during infancy. Nature. 478:382–386. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

La Rosa C, Parolisi R and Bonfanti L:

Brain structural plasticity: From adult neurogenesis to immature

neurons. Front Neurosci. 14(75)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tierney AL and Nelson CA: Brain

development and the role of experience in the early years. Zero

Three. 30:9–13. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Russ JB, Simmons R and Glass HC: Neonatal

encephalopathy: Beyond hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. NeoReviews.

22:e148–e162. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J,

Scott S, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Li M, et al:

Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: An

updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000.

Lancet. 379:2151–2161. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Gopagondanahalli KR, Li J, Fahey MC, Hunt

RW, Jenkin G, Miller SL and Malhotra A: Preterm hypoxic-ischemic

encephalopathy. Front Pediatr. 4(114)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sanchez RM, Koh S, Rio C, Wang C, Lamperti

ED, Sharma D, Corfas G and Jensen FE: Decreased glutamate receptor

2 expression and enhanced epileptogenesis in immature rat

hippocampus after perinatal hypoxia-induced seizures. J Neurosci.

21:8154–8163. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Babbo CCR, Mellet J, van Rensburg J,

Pillay S, Horn AR, Nakwa FL, Velaphi SC, Kali GTJ, Coetzee M,

Masemola MYK, et al: Neonatal encephalopathy due to suspected

hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy: Pathophysiology, current, and

emerging treatments. World J Pediatr. 20:1105–1114. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Rutherford M, Ramenghi LA, Edwards AD,

Brocklehurst P, Halliday H, Levene M, Strohm B, Thoresen M,

Whitelaw A and Azzopardi D: Assessment of brain tissue injury after

moderate hypothermia in neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic

encephalopathy: A nested substudy of a randomised controlled trial.

Lancet Neurol. 9:39–45. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhou T, Mo J, Xu W, Hu Q, Liu H, Fu Y and

Jiang J: Mild hypothermia alleviates oxygen-glucose

deprivation/reperfusion-induced apoptosis by inhibiting ROS

generation, improving mitochondrial dysfunction and regulating DNA

damage repair pathway in PC12 cells. Apoptosis. 28:447–457.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA,

Tyson JE, McDonald SA, Donovan EF, Fanaroff AA, Poole WK, Wright

LL, Higgins RD, et al: Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with

hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 353:1574–1584.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Azzopardi D, Strohm B, Marlow N,

Brocklehurst P, Deierl A, Eddama O, Goodwin J, Halliday HL,

Juszczak E, Kapellou O, et al: Effects of hypothermia for perinatal

asphyxia on childhood outcomes. N Engl J Med. 371:140–149.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Jacobs SE, Berg M, Hunt R, Tarnow-Mordi

WO, Inder TE and Davis PG: Cooling for newborns with hypoxic

ischaemic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

31(CD003311)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Isaković J, Slatković F, Jagečić D,

Petrović DJ and Mitrečić D: Pulsating extremely low-frequency

electromagnetic fields influence differentiation of mouse neural

stem cells towards astrocyte-like phenotypes: In vitro pilot study.

Int J Mol Sci. 25(4038)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Petrović DJ, Jagečić D, Krasić J, Sinčić N

and Mitrečić D: Effect of fetal bovine serum or basic fibroblast

growth factor on cell survival and the proliferation of neural stem

cells: The influence of homocysteine treatment. Int J Mol Sci.

24(14161)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jagečić D, Petrović DJ, Šimunić I,

Isaković J and Mitrečić D: The oxygen and glucose deprivation of

immature cells of the nervous system exerts distinct effects on

mitochondria, mitophagy, and autophagy, depending on the cells'

differentiation stage. Brain Sci. 13(910)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Cornette L: Therapeutic hypothermia in

neonatal asphyxia. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 4:133–139.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lemyre B and Chau V: Hypothermia for

newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Paediatr Child

Health. 23:285–291. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In English,

French).

|

|

23

|

Shankaran S: Therapeutic hypothermia for

neonatal encephalopathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 14:608–619.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wang J, Huang Y, Cai J, Ke Q, Xiao J,

Huang W, Li H, Qiu Y, Wang Y, Zhang B, et al: A

nestin-cyclin-dependent kinase 5-dynamin-related protein 1 axis

regulates neural stem/progenitor cell stemness via a metabolic

shift. Stem Cells. 36:589–601. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hendrickson ML, Rao AJ, Demerdash ON and

Kalil RE: Expression of nestin by neural cells in the adult rat and

human brain. PLoS One. 6(e18535)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Mizuno Y, Takeuchi T, Takatama M and

Okamoto K: Expression of nestin in Purkinje cells in patients with

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurosci Lett. 352:109–112.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Dinsmore JH and Solomon F: Inhibition of

MAP2 expression affects both morphological and cell division

phenotypes of neuronal differentiation. Cell. 64:817–826.

1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Johnson GV and Jope RS: The role of

microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) in neuronal growth,

plasticity, and degeneration. J Neurosci Res. 33:505–512.

1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

DeGiosio RA, Grubisha MJ, MacDonald ML,

McKinney BC, Camacho CJ and Sweet RA: More than a marker: Potential

pathogenic functions of MAP2. Front Mol Neurosci.

15(974890)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Taft WC, Yang K, Dixon CE, Clifton GL and

Hayes RL: Hypothermia attenuates the loss of hippocampal

microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2) following traumatic brain

injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 13:796–802. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Amoureux MC, Cunningham BA, Edelman GM and

Crossin KL: N-CAM binding inhibits the proliferation of hippocampal

progenitor cells and promotes their differentiation to a neuronal

phenotype. J Neurosci. 20:3631–3640. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wu JQ, Habegger L, Noisa P, Szekely A, Qiu

C, Hutchison S, Raha D, Egholm M, Lin H, Weissman S, et al: Dynamic

transcriptomes during neural differentiation of human embryonic

stem cells revealed by short, long, and paired-end sequencing. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:5254–5259. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wang C, Wang X, Wang W, Chen Y, Chen H,

Wang W, Ye T, Dong J, Sun C, Li X, et al: Single-cell RNA

sequencing analysis of human embryos from the late Carnegie to

fetal development. Cell Biosci. 14(118)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Huang R, Yuan DJ, Li S, Liang XS, Gao Y,

Lan XY, Qin HM, Ma YF, Xu GY, Schachner M, et al: NCAM regulates

temporal specification of neural progenitor cells via profilin2

during corticogenesis. J Cell Biol. 219(e201902164)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Blaess S, Graus-Porta D, Belvindrah R,

Radakovits R, Pons S, Littlewood-Evans A, Senften M, Guo H, Li Y,

Miner JH, et al: Beta1-integrins are critical for cerebellar

granule cell precursor proliferation. J Neurosci. 24:3402–3412.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Belvindrah R, Hankel S, Walker J, Patton

BL and Müller U: Beta1 integrins control the formation of cell

chains in the adult rostral migratory stream. J Neurosci.

27:2704–2717. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Fujioka T, Kaneko N, Ajioka I, Nakaguchi

K, Omata T, Ohba H, Fässler R, García-Verdugo JM, Sekiguchi K,

Matsukawa N and Sawamoto K: β1 integrin signaling promotes neuronal

migration along vascular scaffolds in the post-stroke brain.

EBioMedicine. 16:195–203. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Alimperti S and Andreadis ST: CDH2 and

CDH11 act as regulators of stem cell fate decisions. Stem Cell Res.

14:270–282. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kolkova K, Novitskaya V, Pedersen N,

Berezin V and Bock E: Neural cell adhesion molecule-stimulated

neurite outgrowth depends on activation of protein kinase C and the

Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Neurosci.

15:2238–2246. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Schmitt KR, Boato F, Diestel A, Hechler D,

Kruglov A, Berger F and Hendrix S: Hypothermia-induced neurite

outgrowth is mediated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Brain Pathol.

20:771–779. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang D and Zhang J: Effects of hypothermia

combined with neural stem cell transplantation on recovery of

neurological function in rats with spinal cord injury. Mol Med Rep.

11:1759–1767. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Radoszkiewicz K, Jezierska-Woźniak K,

Waśniewski T and Sarnowska A: Understanding intra- and

inter-species variability in neural stem cells' biology is key to

their successful cryopreservation, culture, and propagation. Cells.

12:488–499. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Breschi A, Gingeras TR and Guigó R:

Comparative transcriptomics in human and mouse. Nat Rev Genet.

18:425–440. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Murray A, Gough G, Cindrić A, Vučković F,

Koschut D, Borelli V, Petrović DJ, Bekavac A, Plećaš A, Hribljan V,

et al: Dose imbalance of DYRK1A kinase causes systemic progeroid

status in Down syndrome by increasing the un-repaired DNA damage

and reducing LaminB1 levels. EBioMedicine.

2023(104692)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

![(A and B) Immunohistochemical staining

of neural stem cells in three stages of differentiation: Days 1, 7

and 14, exposed to a normal temperature (37˚C; indicated by ‘N’)

and to hypothermia (32˚C; indicated by ‘H’). The panels on the left

represent DAPI, while those in the middle represent (A) Nestin and

(B) Map2. The panels on the right represent the merged image. It is

visible that on day 1, Nestin is strongly expressed in both

normothermic and hypothermic conditions. On day 7, the Nestin

signal is weaker, but hypothermia does not influence it in any

notable manner. The most notable finding can be seen on day 14

[compare D14N and D14H in (A)]: While in normal conditions Nestin

was almost completely absent, hypothermia re-established the

expression of Nestin. The opposite is visible with the expression

of Map2, which is reduced in hypothermia on day 14 [compare D14N

and D14H in (B)]. Scale bars, 100 µm.](/article_images/mi/5/5/mi-05-05-00252-g02.jpg)