1. Introduction

The level of preparedness of the scientific

community for the next pandemic remains a critical concern. The

ways in which the international scientific community can contribute

to minimizing the public health impact of a new pandemic require

careful consideration. The evaluation of the recent coronavirus

disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is indeed crucial (1-6).

Belonging to the broad family of coronaviruses, a well-known family

of viruses to the paediatric population, severe acute respiratory

syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a positive-sense

single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus, emerged as one of the most

dangerous pathogens in human history (2). The simple structure of the virus,

typical of RNA viruses, such as influenza viruses, human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cancer-associated viruses,

hindered the ability of the immune system to identify its invasion

(2,7). In addition, global genetic variations

influenced morbidity and mortality rates related to

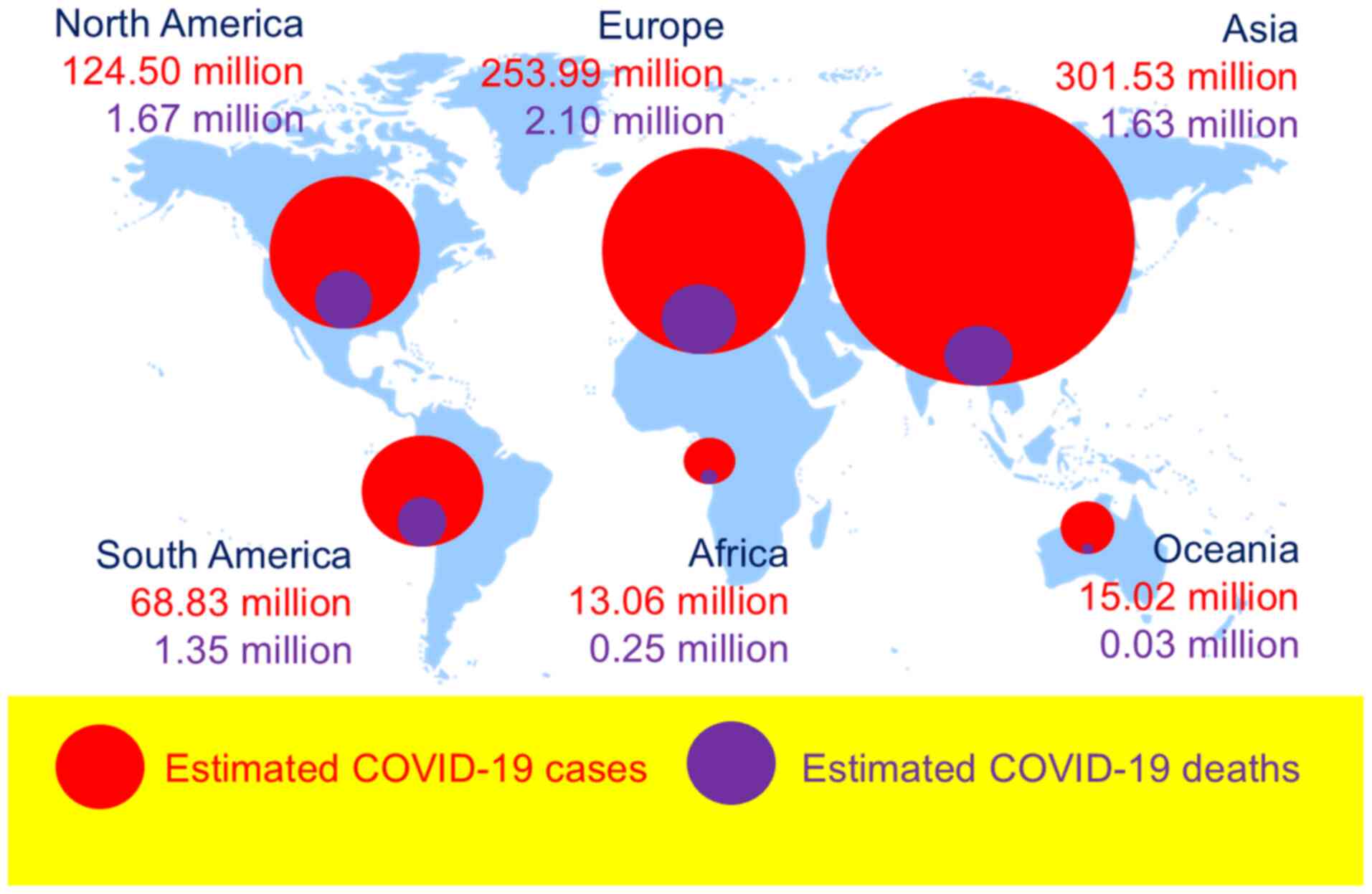

COVID-19(2). The global distribution

of SARS-CoV-2, which since the end of 2019 spread immediately

around the globe, causing an enormous health and economic

catastrophe (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-covid-cases-region

and https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/cumulative-covid-deaths-region)

is presented in Fig. 1.

From the very beginning of the pandemic, there was a

critical need to develop secure, reliable and effective vaccines

and therapeutic agents against SARS-CoV-2 (2,8).

Lockdown and social distancing significantly influenced social and

behavioral aspects of human life. Concurrently, COVID-19 affected

the prevalence of other diseases, including cardiovascular diseases

and cancer, while in tropical and subtropical areas of the world,

COVID-19 lockdown resulted in a significant reduction in the rates

of other infections, such as the Dengue fever (9). The mutations of SARS-CoV-2 resulted in

the continuing emergence of new COVID-19 cases in all age groups,

including children, for several months (7). SARS-CoV-2 infection remains prevalent,

while efforts to fund research on COVID-19 have continued to the

present day. Research has also focused on post-COVID-19 syndrome

and its management (10).

Medical advances and improvements, as well as

management limitations, weaknesses and challenges, encountered

during the COVID-19 pandemic, require an up-to-date evaluation. In

addition to the medical aspects of the pandemic and issues

pertaining to strategic preparedness and response planning

(1-5),

it is also important to systematically analyze non-medical issues,

including politics and science communication. The lessons derived

from this evaluation will help the prioritisation of research and

strategic planning in the event of a future pandemic. Moreover,

this analysis will guide the development of up-to-date educational

programs to be integrated in both undergraduate and postgraduate

medical training, worldwide.

The purpose of the present review article is to

summarize the key messages on the lessons learnt from the recent

COVID-19 pandemic, one of the most critical and disruptive events

of modern times. The main topics on COVID-19 that are discussed

herein are: i) Advances in intensive medicine during the COVID-19

pandemic, focusing on high flow nasal oxygen therapy (HFNOT); ii)

COVID-19 and politics; and iii) COVID-19 and science communication

(Table I).

| Table IKey lessons from the COVID-19

pandemic: The role of intensive care, politics and science

communication. |

Table I

Key lessons from the COVID-19

pandemic: The role of intensive care, politics and science

communication.

| Topic | Main points and

take-home messages (Refs.) |

|---|

| COVID-19 and

intensive care medicine | HFNOT is a

relatively novel technique for delivering warm, humidified oxygen

at high flow rates to patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory

failure, including COVID-19 cases (11-32). |

| | HFNOT is supported

by strong physiological evidence; HFNOT has been shown to improve

oxygenation, reduce the work of breathing and enhance lung function

(12-15). |

| | During the recent

COVID-19 pandemic, HFNOT has been increasingly used in ICU and PICU

patients due to its effectiveness and particularly its tolerability

(27-32). |

| | Meta-analyses on

the use of HFNOT in acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure and

COVID-19 infection have generally shown that HFNOT is more

effective than COT in reducing the need for higher respiratory

support and comparable to NIV (27-30). |

| | HFNOT can be

applied in the early management of hypoxemia and respiratory

distress in children admitted to the PICU (23-26,31,32). |

| COVID-19 and

politics | The COVID-19

pandemic highlighted the deep interactions between science,

society, and politics; the rapid development of vaccines was a

significant scientific achievement, driven by the collaboration of

scientists, governments and international organizations (33-47). |

| | Despite various

international efforts, inequalities in vaccine access underscored

the economic and geopolitical aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic

(41). |

| | Politics played a

crucial role in managing the pandemic, with decisions regarding

lockdowns and vaccination programs often influenced by political

calculations, such as economic stability and social pressure,

rather than solely by scientific data (33-47). |

| | The conflict

between science and politics, as well as misinformation, undermined

public trust and complicated the implementation of necessary

measures (44). |

| | The need for

political focus on the updated training of healthcare professionals

was another key message from the recent COVID-19 pandemic (45-47). |

| COVID-19 and

science communication | During the COVID-19

pandemic, frontline researchers around the globe, along with their

official institutions and scientific societies, had the principal

role in transparently communicating information about SARS-CoV-2 to

the public (50-62). |

| | However, throughout

the pandemic, non-specialist scientists and others also assumed a

key role in public communication, while an unprecedented surge of

information, disinformation and misinfor- mation about SARS-CoV-2

was spread especially via the social media platforms (52-54). |

| | Science

communication on COVID-19 was another example that required

multidisciplinary collaboration with communication experts leading

to the urgent development and usage of innovative communication

strategies (50-62). |

| | The post-COVID-19

pandemic period provides a valuable opportunity to evaluate the

relationship between science communication and society to improve

the preparedness of the international scientific community for the

next pandemic (61,62). |

2. High flow nasal oxygen therapy: Not just

another oxygen delivering modality

During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, intensive care

medicine came to the forefront of the fight against SARS-CoV-2.

Thus far, the learning experience has been intense and has affected

every aspect of this medical specialty, from therapeutic tools to

management strategies and protocols. HFNOT is a relatively novel

method for delivering warm humidified oxygen at high flows to

patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure (11). The interest in HFNOT and its

potential has been further increased during the COVID-19 pandemic,

which imposed significant demands on hospital resources,

necessitating prudent patient prioritization and careful allocation

of respiratory care equipment and intensive care unit (ICU) beds

(12).

The HFNOT system setup is simple: It requires only a

flow generator, an active heated humidifier, a single heated

circuit with a servo-controlled heating wire, and a silicone nasal

cannula (11). HFNOT has emerged as

an effective and well-tolerated respiratory support technique in

various clinical scenarios, although the optimal method for

managing acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure remains under debate.

Physiological studies have demonstrated that HFNOT, apart from

being an effective oxygenator, reduces the work of breathing and

respiratory resistance, increases positive end-expiratory pressure

and end-inspiratory lung volume, washes off anatomic dead space and

improves secretion clearance (12).

A common practice is to start HFNOT with a fraction of inspired

oxygen (FiO2) of 100% and a flow of 60 l/min and then

adjust FiO2 and the flow to achieve an oxygen saturation

(SpO2) >88-90% and an age-appropriate respiratory

rate (RR) (13). A ROX index

(calculated as the SpO2/FiO2 ratio divided by

the RR of the patient) >4.88 at 12 h has a high positive

predictive value (89.4%) in predicting treatment success (14). The only absolute contraindication for

HFNOT is any indication for invasive mechanical ventilation

including shock, respiratory and cardiac arrest, bradycardia,

severe arrhythmias and an impaired level of consciousness. Facial

erythema, skin breakdown and barotrauma may occur in HFNOT users,

although these represent less common complications compared with

non-invasive ventilation (NIV). Overall, HFNOT is better tolerated

than NIV (15).

Prior to the COVID-19 era, Hernández et al

(16,17) demonstrated that HFNOT compared with

conventional oxygen therapy (COT) decreases the risk of

reintubation and post-extubation respiratory failure in ‘low-risk’

ICU patients, while in ‘high-risk’ patients HFNOT was not inferior

to NIV in averting reintubation and post-extubation respiratory

failure. However, neither of these two studies (16,17)

noted any benefit in terms of mortality rates. In a meta-analysis

by Zhu et al (18) that

followed, HFNOT reduced the risk of post-extubation respiratory

failure, improved oxygenation and reduced respiratory rates in

post-extubated ICU patients. Moreover, in another meta-analysis by

Granton et al (19), HFNOT

reduced re-intubation rates compared with COT, but not when

compared with NIV. However, other researchers have failed to

duplicate these findings (20).

Thus, in another meta-analysis by Maitra et al (21) comparing HFNOT with NIV and COT in

patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure, no benefit was

shown for HFNOT in decreasing requirements for higher respiratory

support. Nevertheless, more recently Seow et al (22) reviewed a total of 63 studies

[including 23 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)], which compared

HFNOT with COT and showed that HFNOT decreased the risk for

escalating to NIV or invasive respiratory support. In the

paediatric population, several RCTs have suggested that compared

with COT, HFNOT reduced the rates of intubation and mechanical

ventilation in children with moderate-to-severe bronchiolitis and

hypoxaemic respiratory failure (23-26).

HFNOT is a growing respiratory treatment for children, particularly

for those with respiratory distress, bronchiolitis, or other

respiratory illnesses.

Focusing on acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure in

patients with COVID-19, a meta-analysis of 40 studies including two

RCTs by Arruda et al (27),

suggested that HFNOT reduced the risk of intubation compared with

COT, but showed no additional benefit when compared with NIV. In

another meta-analysis by Li et al (28), again focusing on patients with

COVID-19, HFNOT was demonstrated to reduce the rate of intubation,

28-day mortality and ventilator-free days compared with COT.

However, these results were not reproduced by a recent

meta-analysis by Pisciotta et al (29) involving patients with

COVID-19-induced hypoxaemic respiratory failure, which showed no

benefit in terms of treatment failure for HFNOT compared with NIV

and COT.

Recent guidelines issued by the European Respiratory

Society (ERS) suggest HFNOT over NIV or COT for the management of

acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure. However, although they favor

HFNOT over COT for post-extubated ICU patients with ‘low-’ or

‘moderate-risk’ for re-intubation, they suggest NIV over HFNOT for

‘high-risk’ patients (30). During

the COVID-19 pandemic, HFNC was also widely applied in the early

management of hypoxemia and respiratory distress in children with

COVID-19 requiring paediatric intensive care (31,32).

3. COVID-19 and politics: Challenges,

dilemmas and lessons

Politics was one of the most significant,

non-medical issues of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, which

demonstrated the interactions between science, society and politics

(33). Since the onset of this

unprecedented global health challenge, numerous countries designed

and implemented various and controversial policies against

SARS-CoV-2(34). For example, the

‘zero-COVID-19 policy’, which was adopted by China as well as other

countries, tried strictly to eliminate local transmission of the

virus (35-37).

On the other hand, the ‘Swedish COVID-19 approach’, which did not

enforce strict lockdown measures, was based on voluntary

recommendations and guidelines (38). Concurrently, Latin American countries

appeared to struggle with implementing specific COVID-19 pandemic

policies for their citizens (39).

Politics influenced the development, distribution

and access of vaccines and therapeutic agents against SARS-CoV-2,

as well as public health management and social reaction. The

accomplishment of this task would not have been possible without

the close collaboration between scientists, scientific institutions

and governments. Funding through state resources and support from

international organizations, such as the World Health Organization

(WHO), also played a fundamental role (40).

Although the scientific society responded promptly

by developing and approving novel vaccines and therapeutic agents

against SARS-CoV-2, the global community faced deep inequalities in

their access. For example, the European Union countries, including

Greece, succeeded in achieving timely access to a sufficient amount

of vaccine doses against SARS-CoV-2(2). The European Union prioritized the

introduction of vaccination programs against SARS-CoV-2 as its

principal political strategy against COVID-19 (https://health.ec.europa.eu/vaccination/overview_en).

Developed countries gained privileged access to the first batches

of vaccines, securing deals with pharmaceutical companies long

before their release (41). The

European Union countries responded quickly and prioritized

solidarity in order to provide access to vaccines against

SARS-CoV-2 to all the European citizens (https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/coronavirus-response/coronavirus-european-solidarity-action_en).

Moreover, international efforts, such as the global initiative

COVAX, co-led by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Coalition for

Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the WHO and UNICEF,

sought to ensure equitable distribution of vaccines to developed

and developing countries (41).

However, all these efforts failed to meet their goals adequately.

‘Vaccine nationalism’ prominently affected the allocation of

resources, as numerous governments chose to secure the needs of

their populations neglecting international commitments. ‘Vaccine

diplomacy’, as a political tool for foreign policy and

international influence was also used as leverage to promote

political and economic interests. These inequalities highlighted

the gap between rich and poor countries and raised ethical and

practical issues that may resonate and affect healthcare management

of future crises.

The pandemic exposed the reciprocal relationship

between politics and public health (42-44).

Political leaders worldwide were challenged to make decisions that

directly affected the spread of the virus, healthcare provision and

the public perception of the pandemic. In numerous countries,

decisions to impose lockdowns or lift restrictions were based on

political calculations, such as the need to stabilize the economy

or to respond to social pressure, rather than solely on scientific

data and advice. The conflict between science and politics proved

particularly harmful in cases where politicians downplayed the

threat of the pandemic or spread misinformation, as witnessed in

some countries with strong populist movements. These decisions

undermined public trust in scientific authorities and challenged

the implementation of necessary health measures. In several

countries, political polarization and misinformation about vaccine

safety increased vaccine hesitancy (45).

The need for updated training of healthcare

professionals was another clear message from the recent COVID-19

pandemic (46,47). Political fora are expected to support

the adjustment of medical educational programs to new realities and

organize targeted actions involving the institutions responsible

for providing ongoing medical education. Continuing medical

education is critical as this could promote the value of medical

education in paediatric viral infections as well, including

COVID-19 (48,49). If the next pandemic disproportionally

affects the paediatric population, this effort will play a key role

for the preparedness of the paediatric personnel and healthcare

system of each country.

For the post-COVID-19 era, long-term policies are

required to prepare humanity for future health crises. The

international community must ensure equal access to vaccines and

therapeutic agents, regardless of the economic strength of a

country. Governments need to collaborate with international

organizations and the private sector to create a more resilient

global public health system that can respond quickly and

effectively to new threats and challenges (47). Our experience from the COVID-19

pandemic has taught us that health cannot be separated from

politics and that protecting human life should be the highest

priority, beyond economic or political calculations.

4. COVID-19 and science communication

Science communication-is a highly demanding process,

which deals with complex information, dynamic uncertainty and

diverse audiences, with varying educational levels, cultural

beliefs, attitudes and behaviours, that impact the understanding of

science (50). Effective science

communication is now established as an important tool that provides

accurate scientific knowledge to the public and helps them identify

false information. Ineffective communication, on the other hand,

can be detrimental to both science and society in general.

During the recent COVID-19 pandemic, science

communication demonstrated its critical influence on public health.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic threat, healthcare

professionals strived to translate science and communicate its

ongoing findings in a timely and accessible manner to various

audiences (51). Frontline

researchers, alongside organizations such as the WHO, played the

principal role to transparently communicate their findings and

explain them to the public in a meaningful and understandable way.

There was an unprecedented demand for scientific knowledge; in

fact, the overwhelming requests from journalists for

epidemiological and research updates threatened to shift focus and

resources from viral research to media demands.

However, throughout the pandemic, non-specialist

scientists, academics, journalists, and others played a key role in

the communication of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 advances,

recommendations and challenges. Despite newspapers and press

websites typically being reliable sources, the COVID-19 pandemic

witnessed an unparalleled surge of both accurate and inaccurate

information, largely spread via digital channels and platforms,

such as Twitter/X, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok (52-54).

Official scientific institutions and societies had to address

issues, such as ‘fake news’ and uncertainty, the latter being a

typical characteristic of scientific research, which was however

misinterpreted and perceived as inaccuracy or even unreliability.

Misinformation and disinformation regarding COVID-19 vaccine safety

were strongly related to increased vaccine hesitancy (55-57).

Science communication with the aid of reliable and

accessible official social media platforms was also encouraged

(58). Innovative new communication

strategies were proposed and used, including social media and

podcasts (59). These tools were

more effective at targeting specific audiences, such as adolescents

and the young population. Science communication on COVID-19

pandemic required multidisciplinary scientific collaboration.

Collaboration with visual communicators and design experts produced

digital illustrations and demonstrations of SARS-CoV-2, which

improved the understanding of the virus and health safety measures

and improved vaccine confidence (60).

The post COVID-19 era offers a chance to assess the

social impact of science communication and improve its future

effectiveness. Researchers and scientific institutions need to

design and develop novel communication strategies in order to

respond effectively to future potential crises. Scientists with

communication skills, passion and training should be motivated.

Moreover, scientific societies should create improved links with

the media and ensure that healthcare journalists are well informed

and trained. Despite its devastating health, social, and financial

ramifications, the COVID-19 pandemic presents a genuine opportunity

to improve pandemic preparedness (61,62).

5. Conclusions

Pandemic evaluation and planning perspectives

towards future infectious threats remain challenging. HFNOT, a

non-invasive ventilation modality increasingly used prior to the

COVID-19 era in both ward-based and critical care management of

respiratory failure (11-25),

represents an excellent clinical example of how the COVD-19

pandemic enriched medical knowledge and experience (26-32).

The medical experience gained from the treatment of critically ill

patients with COVID-19, should be further evaluated for the

establishment of state-of-the-art, evidence-based medical

consensuses and protocols. These tools are essential for the

effective and precise management of adults and paediatric patients

and should be integrated in current clinical practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a pivotal moment for

global health and politics (33-47).

The collaboration between science and politics contributed to the

rapid development of vaccines and therapeutic agents against

SARS-CoV-2, however global distribution was uneven due to national

policies and geopolitical tensions. Different political agendas

influenced not only the distribution of vaccines but also the

public perception of their safety and efficacy. Therefore, the

international community must be taught from these errors and work

towards a more equitable and resilient approach to future health

crises. Public health safety necessitates collaboration and

impartiality, prioritizing global solidarity and equality above

national and political agendas. Political decisions focusing on

increasing the financial health resources in primary health care

and advancing secondary and tertiary hospital-based care should be

encouraged. Health policies should also focus on enhancing

specialized as well as continuing medical education (46-49).

Science communication also demonstrated its

potential usefulness and effectiveness during the recent pandemic

(50-62).

This burgeoning scientific discipline should be further developed

and integrated into both undergraduate and postgraduate medical

education. Health professionals must develop effective

communication skills and become adept in providing accurate and

useful information to their patients and the general population, as

well. In the unfortunate event of a future pandemic, effective

science communication will depend on multi-disciplinary

collaboration between clinical and research scientists and

communication experts; this task requires improved digital tools

and innovative strategies to address public misinformation and

disinformation.

The aim of the present review article was to

stimulate further discussion within the international scientific

community on the evaluation of the management of the recent

COVID-19 pandemic. A careful interpretation of the lessons learned

may help promote strategic planning and preparedness, and advance

public health, translational research and future medicine.

Acknowledgements

This article is published in the context of the

‘10th Workshop on Paediatric Virology’, organized on November 9,

2024 by the Institute of Paediatric Virology (IPV, https://www.paediatricvirology.org), which is

based on the island of Euboea in Greece. The authors would like to

thank Professor Anna Kramvis, Professor Emerita of Virology at the

Department of Internal Medicine at the University of the

Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa and Member of the

Academic Advisory Board of the IPV for her valuable comments,

corrections and feedback. The authors would also like to thank Ms.

Aikaterini Kalaitzoglou, Parliamentary Associate, as well as all

members of the Paediatric Virology Study Group (PVSG) and the IPV

for their valuable contribution in the preparation of the

manuscript.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors (INM, MA, AK, CK, AP, SBD, MT, and DAS)

contributed equally to the conception and design of this

manuscript, wrote the original draft, edited and critically revised

the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

World Health Organization: COVID-19

strategic preparedness and response plan: Operational planning

guidelines to support country preparedness and response. Geneva:

World Health Organization, 2020.

|

|

2

|

Zoumpourlis V, Goulielmaki M, Rizos E,

Baliou S and Spandidos DA: The COVID-19 pandemic as a scientific

and social challenge in the 21st century. Mol Med Rep.

22:2035–3048. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Jentsch PC, Anand M and Bauch CT:

Prioritising COVID-19 vaccination in changing social and

epidemiological landscapes: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet

Infect Dis. 21:1097–1106. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

O'Callaghan C, Cloutman-Green E and

Brierley J: Pandemic preparedness: Is the UK ready for a pandemic

that affects children? BMJ. 383(2804)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Qin Z, Sun Y, Zhang J, Zhou L, Chen Y and

Huang C: Lessons from SARS-CoV-2 and its variants (review). Mol Med

Rep. 26(263)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Quinn GA, Connolly R, ÓhAiseadha C, Hynds

P, Bagus P, Brown RB, Cáceres CF, Craig C, Connolly M, Domingo JL,

et al: What lessons can be learned from the management of the

COVID-19 pandemic? Int J Public Health. 70(1607727)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Markiewicz L, Drazkowska K and Sikorski

PJ: Tricks and threats of RNA viruses-towards understanding the

fate of viral RNA. RNA Biol. 18:669–687. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Singh M, Jayant K, Singh D, Bhutani S,

Poddar NK, Chaudhary AA, Khan SU, Adnan M, Siddiqui AJ, Hassan MI,

et al: Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha) for the possible

therapeutics and clinical management of SARS-CoV-2 infection:

Plant-based drug discovery and targeted therapy. Front Cell Infect

Microbiol. 12(933824)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Sharma H, Ilyas A, Chowdhury A, Poddar NK,

Chaudhary AA, Shilbayeh SAR, Ibrahim AA and Khan S: Does COVID-19

lockdowns have impacted on global dengue burden? A special focus to

India. BMC Public Health. 22(1402)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

No authors listed: Post-COVID-19 Condition

Treatment and Management Rapid Scoping Review: Scoping review.

CADTH Health Technology Review. Canadian Agency for Drugs and

Technologies in Health, Ottawa, ON, 2022.

|

|

11

|

Nishimura M: High-flow nasal cannula

oxygen therapy devices. Respir Care. 64:735–742. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Crimi C, Pierucci P, Renda T, Pisani L and

Carlucci A: High-flow nasal cannula and COVID-19: A clinical

review. Respir Care. 67:227–240. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ischaki E, Pantazopoulos I and Zakynthinos

S: Nasal high flow therapy: A novel treatment rather than a more

expensive oxygen device. Eur Respir Rev. 26(170028)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Roca O, Messika J, Caralt B,

García-de-Acilu M, Sztrymf B, Ricard JD and Masclans JR: Predicting

success of high-flow nasal cannula in pneumonia patients with

hypoxemic respiratory failure: The utility of the ROX index. J Crit

Care. 35:200–205. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

D'Cruz RF, Hart N and Kaltsakas G:

High-flow therapy: Physiological effects and clinical applications.

Breathe (Sheff). 16(200224)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, Subira

C, Frutos-Vivar F, Rialp G, Laborda C, Colinas L, Cuena R and

Fernández R: Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs

conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: A

randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 315:1354–1361. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hernández G, Vaquero C, Colinas L, Cuena

R, González P, Canabal A, Sanchez S, Rodriguez ML, Villasclaras A

and Fernández R: Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula

vs noninvasive ventilation on reintubation and postextubation

respiratory failure in high-risk patients: A randomized clinical

trial. JAMA. 316:1565–1574. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhu Y, Yin H, Zhang R, Ye X and Wei J:

High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy versus conventional oxygen

therapy in patients after planned extubation: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 23(180)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Granton D, Chaudhuri D, Wang D, Einav S,

Helviz Y, Mauri T, Mancebo J, Frat JP, Jog S, Hernandez G, et al:

High-flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy

or noninvasive ventilation immediately postextubation: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 48:e1129–1136.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Douglas N, Ng I, Nazeem F, Lee K, Mezzavia

P, Krieser R, Steinfort D, Irving L and Segal R: A randomised

controlled trial comparing high-flow nasal oxygen with standard

management for conscious sedation during bronchoscopy. Anaesthesia.

73:169–176. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Maitra S, Som A, Bhattacharjee S, Arora MK

and Baidya DK: Comparison of high-flow nasal oxygen therapy with

conventional oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation in adult

patients with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: A meta-analysis

and systematic review. J Crit Care. 35:138–144. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Seow D, Khor YH, Khung SW, Smallwood DM,

Ng Y, Pascoe A and Smallwood N: High-flow nasal oxygen therapy

compared with conventional oxygen therapy in hospitalised patients

with respiratory illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

BMJ Open Respir Res. 11(e002342)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kepreotes E, Whitehead B, Attia J,

Oldmeadow C, Collison A, Searles A, Goddard B, Hilton J, Lee M and

Mattes J: High-flow warm humidified oxygen versus standard low-flow

nasal cannula oxygen for moderate bronchiolitis (HFWHO RCT): An

open, phase 4, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 389:930–939.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Franklin D, Babl FE, Schlapbach LJ, Oakley

E, Craig S, Neutze J, Furyk J, Fraser JF, Jones M, Whitty JA, et

al: A randomized trial of high-flow oxygen therapy in infants with

bronchiolitis. N Engl J Med. 378:1121–1131. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kawaguchi A, Yasui Y, deCaen A and Garros

D: The clinical impact of heated humidified high-flow nasal cannula

on pediatric respiratory distress. Pediatr Crit Care Med.

18:112–119. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kwon JW: High-flow nasal cannula oxygen

therapy in children: A clinical review. Clin Exp Pediatr. 63:3–7.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Arruda DG, Kieling GA and Melo-Diaz LL:

Effectiveness of high-flow nasal cannula therapy on clinical

outcomes in adults with COVID-19: A systematic review. Can J Respir

Ther. 59:52–65. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Li Y, Li C, Chang W and Liu L: High-flow

nasal cannula reduces intubation rate in patients with COVID-19

with acute respiratory failure: A meta-analysis and systematic

review. BMJ Open. 13(e067879)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Pisciotta W, Passannante A, Arina P,

Alotaibi K, Ambler G and Arulkumaran N: High-flow nasal oxygen

versus conventional oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation in

COVID-19 respiratory failure: A systematic review and network

meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth.

132:936–944. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Oczkowski S, Ergan B, Bos L, Chatwin M,

Ferrer M, Gregoretti C, Heunks L, Frat JP, Longhini F, Nava S, et

al: ERS clinical practice guidelines: High-flow nasal cannula in

acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 59(2101574)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Loomba RS, Villarreal EG, Farias JS,

Bronicki RA and Flores S: Pediatric intensive care unit admissions

for COVID-19: Insights using state-level data. Int J Pediatr.

2020(9680905)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wu JH, Wang CC, Lu FL, Huang SC and Wu ET:

The applications of high-flow nasal cannulas in pediatric intensive

care units in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 124:15–21.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Albrecht D: Vaccination, politics and

COVID-19 impacts. BMC Public Health. 22(96)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Chung HW, Apio C, Goo T, Heo G, Han K, Kim

T, Kim H, Ko Y, Lee D, Lim J, et al: Effects of government policies

on the spread of COVID-19 worldwide. Sci Rep.

11(20495)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Bai W, Sha S, Cheung T, Su Z, Jackson T

and Xiang YT: Optimizing the dynamic zero-COVID policy in China.

Int J Biol Sci. 18:5314–5316. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Chen JM and Chen YQ: China can prepare to

end its zero-COVID policy. Nat Med. 28:1104–1105. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

The Lancet Regional Health-Western

Pacific. The end of zero-COVID-19 policy is not the end of COVID-19

for China. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 30(100702)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Petridou E: Politics and administration in

times of crisis: Explaining the Swedish response to the COVID-19

crisis. Eur Policy Anal. 6:147–158. 2020.

|

|

39

|

Martinez-Valle A: Public health matters:

Why is Latin America struggling in addressing the pandemic? J

Public Health Policy. 42:27–40. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Emanuel EJ, Luna F, Schaefer GO, Tan KC

and Wolff J: Enhancing the WHO's proposed framework for

distributing COVID-19 vaccines among countries. Am J Public Health.

111:371–373. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Yoo KJ, Mehta A, Mak J, Bishai D, Chansa C

and Patenaude B: COVAX and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines.

Bull World Health Organ. 100:315–328. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Gonsalves G and Yamey G: Political

interference in public health science during the COVID-19. BMJ.

371(M3878)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Fedson DS: COVID-19, host response

treatment, and the need for political leadership. J Publ Health

Policy. 42:6–14. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Greer SL, King EJ, Massard da Fonseca E

and Peralta-Santos A (eds): Coronavirus politics: The comparative

politics and policy of COVID-19. University of Michigan Press,

2021.

|

|

45

|

Lazarus JV, Wyka K, White TM, Picchio CA,

Rabin K, Ratzan SC, Parsons Leigh J, Hu J and El-Mohandes A:

Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data

from 23 countries in 2021. Nat Commun. 13(3801)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Lucey CR and Johnston SC: The

transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA.

324:1033–1034. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Frenk J, Chen LC, Chandran L, Groff EOH,

King R, Meleis A and Fineberg HV: Challenges and opportunities for

educating health professionals after the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet.

400:1539–1556. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mammas IN, Liston M, Koletsi P, Vitoratou

DI, Koutsaftiki C, Papatheodoropoulou A, Kornarou H, Theodoridou M,

Kramvis A, Drysdale SB and Spandidos DA: Insights in paediatric

virology during the COVID-19 era (review). Med Int (Lond).

2(17)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Mammas IN, Drysdale SB, Charalampous C,

Koletsi P, Papatheodoropoulou A, Koutsaftiki C, Sergentanis T,

Merakou K, Kornarou H, Papaioannou G, et al: Navigating paediatric

virology through the COVID-19 era (Review). Int J Mol Med.

52(83)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Fischhoff B and Scheufele DA: The science

of science communication. Introduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 110

(Suppl 3):S14031–S14032. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Amer P: Coronavirus conversations: Science

communication during a pandemic. Nature: May 27, 2020 (Epub ahead

of print).

|

|

52

|

Rubin R: When physicians spread

unscientific information about COVID-19. JAMA. 327:904–906.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Joseph AM, Fernandez V, Kritzman S, Eaddy

I, Cook OM, Lambros S, Jara Silva CE, Arguelles D, Abraham C,

Dorgham N, et al: COVID-19 Misinformation on social media: A

scoping review. Cureus. 14(e24601)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Lurie P, Adams J, Lynas M, Stockert K,

Carlyle RC, Pisani A and Evanega SD: COVID-19 vaccine

misinformation in English-language news media: Retrospective cohort

study. BMJ Open. 12(e058956)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Wilson SL and Wiysonge C: Social media and

vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob Health. 5(e004206)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Schwarzinger M and Luchini S: Addressing

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Is official communication the key?

Lancet Public Health. 6:e353–e354. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Karafilakis E, Van Damme P, Hendrickx G

and Larson HJ: COVID-19 in Europe: New challenges for addressing

vaccine hesitancy. Lancet. 399:699–701. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Heuss SC, Zachlod C and Miller BT:

‘Social’ media? How Swiss hospitals used social media platforms

during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Public

Health. 219:53–60. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Rubin EJ, Baden LR and Morrissey S: Audio

interview: Covid-19 takeaways at podcast 100. N Engl J Med.

386(e11)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Boender TS, Louis-Ferdinand N and Duschek

G: Digital visual communication for public health: Design proposal

for a vaccinated emoji. J Med Internet Res.

24(e35786)2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Davies SC, Audi H and Cuddihy M:

Leveraging data and new digital tools to prepare for the next

pandemic. Lancet. 397:1349–1350. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Sachs JD, Karim SSA, Aknin L, Allen J,

Brosbøl K, Colombo F, Barron GC, Espinosa MF, Gaspar V, Gaviria A,

et al: The lancet commission on lessons for the future from the

COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 400:1244–1280. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|