Introduction

Chronic disease, including inflammatory bowel

disease (IBD) is associated with significant costs. Although a

number of studies have evaluated the costs of care (including

medication, hospitalisation and surgery ambulatory visits) in the

high-income regions, the data are relatively limited in the lower-

and middle-income countries (LMICs) (1). The care of patients with IBD in LMICs

has certain additional caveats; the use of advanced therapies

including biologicals and small molecules is limited by a lack of

access, availability and comfort with their use (2,3). There

may also be an additional role of risk of infections, including

tuberculosis and the higher uptake of complementary and alternative

medication that may reduce the compliance with standard therapies,

resulting in increased flares (4).

The treatment paradigm for ulcerative colitis (UC),

a chronic relapsing-remitting disease, continues to evolve and the

data for a top-down approach for UC are limited, as are those

against Crohn's disease (5).

Therefore, standard therapies, including 5-aminosalicylates and

thiopurines remain the major tools in the treatment of UC,

particularly in LMICs (6). IBD,

including UC results in not only in a physical, mental and social

burden, but is also associated with a marked financial burden to

patients, as well as their caregivers (7). Any flare of the disease increases this

burden. The need for rescue therapy in the form of advanced

therapies (anti-TNF agents, anti-integrins, anti-IL-12/23 and small

molecules) or surgery increases both the short-, as well as

long-term financial burden. However, the selection of therapy in

numerous regions of the globe is dictated by cost considerations,

and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) compounds and thiopurines are

often used as a first-line therapy; surgery appears fairly early in

the treatment paradigm. It is unclear whether the cost of flares is

substantially higher than ongoing therapy during periods of

remission in LMICs (8). The present

study aimed to analyse the monthly cost of care of patients with UC

in remission during their regular follow-up and compare this to the

expenses born during an episode of acute exacerbation, in order to

estimate the costs of such episodes of flares. Cost-of-illness

analysis for patients with UC in remission, as well as for those

with acute exacerbations was performed; this included direct costs

(medical and non-medical), as well as indirect costs during

out-patient department (OPD) visits and in-patient admissions.

Patients and methods

Study setting

The present study was a prospective observational,

cross-sectional, single-centre study conducted between January,

2022 to June, 2024; the study included 25 patients with UC who were

in remission [simple clinical colitis activity index (SCCAI) score

<3] and 51 patients with UC who presented with flares and

required hospitalisation for acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC)

at the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research

(PGIMER) in Chandigarh, India. The present study was approved by

the Institute Ethics Committee of the Post Graduate Institute of

Medical Education and Research (INT/IEC/2022/000488). A written

informed consent/assent was obtained from all subjects or their

legal guardians.

Study population. UC cases in

remission

UC cases in remission were managed in the OPD.

Patients were deemed to be in disease remission with both i) a

SCCAI score <3 with a stable bowel frequency over the past 6

months; and ii) a normal faecal calprotectin level (<100 mcg/g)

(4). The evaluation of patients

included an investigation of clinical history and an examination,

periodic biochemical testing, faecal calprotectin level assessment

and an unprepared sigmoidoscopic examination. Any treatment

modification was determined as per the disease activity during OPD

visits. The total duration for OPD follow-up for UC cases in

remission was 6 months.

Patients with flares requiring

hospitalisation. Those patients who had severe flares requiring

hospital admission were included and the majority of these were

patients had ASUC. Patients who were admitted for non-flare

conditions, such as intercurrent infection were excluded. The

evaluation of cases with flares included an investigation of

clinical history and an examination, biochemical testing, stool

analysis for routine examination, faecal calprotectin level

assessment, Clostridioides difficile toxin assay and

unprepared sigmoidoscopic examination. Standard treatment for ASUC

was with intravenous steroid and venous thromboprophylaxis, and

5-aminosalicylate optimisation was performed, followed by a

response assessment using the Oxford criteria and those deemed to

be non-responsive were offered second-line therapy (intravenous

cyclosporine or intravenous infliximab or colectomy) (9).

Cost estimation

The data on expenses were categorised as direct

medical, direct non-medical and indirect costs, which were summated

as total expenditures. The cost of treatment was defined as

follows: i) Direct medical costs: These included the cost of drugs,

as well as any investigations, including the cost of surgery if

required. The cost of drugs was calculated by taking the average

cost of five commonly used drug brands used for treatment which

were available locally, while the cost of investigations included

the standard cost of tests, as fixed by the institution. ii) Direct

non-medical costs: These included the cost of stay and travel. The

cost of stay included the cost of in-hospital admission, as well as

the per-day-cost of admission during the admitted period for

patients, as well as the stay of lodging for 1 patient attendant.

Travelling costs included standard railway ticket costs for sleeper

class, as fixed by the government railway agency (IRCTC) from

Chandigarh to the nearest railway station of the hometown of the

patient. iii) Indirect costs: These included total job earnings

lost during the treatment period. These included daily wages lost

for patients, as well as the attendant of each patient.

Statistical analysis

All descriptive and inferential statistics were

generated using SPSS software version 23 (IBM Corp.). Cost data are

expressed as the average per capita monthly cost in Indian rupees

(INR). Wherever appropriate, data in percentages and numbers are

presented. The Chi-squared test was used to analyse the differences

between categorical data. Fisher's exact test was used if the

expected frequency was ≤5 in any cell. An independent samples

t-test or the Mann Whitney U test were used to compare continuous

variables depending on the normality of the distribution (as per

the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). A value of P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patients enrolled and patient

characteristics

The present study enrolled 25 patients with UC in

remission and 51 patients with ASUC.

UC cases in remission. Among the 25 patients

with UC in remission, 12 (48%) were male and the median age of the

patients was 35 years (range, 22-60 years). The majority of the

patients were in socioeconomic upper lower class (n=12) and lower

middle class (n=8), as per the modified Kuppuswamy socieoeconomic

scale (10). All the patients were

in clinical remission for varying periods of time (3-96 months;

mean, 19±24 months). E3 disease was the most common (10 patients,

40%) and no patient had any extraintestinal manifestations. The

majority of the patients were on a combination of 5-ASA with

thiopurine (16 patients, 64%) while the remainder were controlled

on 5-ASA compounds alone (Table

I).

| Table IDemographic and clinical features of

patients with UC in remission vs. those with flares (with

ASUC). |

Table I

Demographic and clinical features of

patients with UC in remission vs. those with flares (with

ASUC).

| Baseline clinical

characteristics | Patients with UC in

remission (n=25) | Patients with ASUC

(n=51) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, median; (range)

years | 35 (22-60) | 51 (16-65) | 0.521 |

| Male/female | 12 (48%)/13

(52%) | 27 (53%)/24

(47%) | 0.684 |

| SCCAI score; median

(range) | 0 (0-2) | 11 (6-14) | <0.001 |

| Disease free

period | 19±24 months | NA | |

| Extent of

diseasea | | | |

|

E1(Y/N) | 3 (12%)/22 (88%) | 1 (2%)/50 (98%) | 0.101 |

|

E2

(Y/N) | 8 (32%)/17 (68%) | 8 (16%)/43 (84%) | 0.112 |

|

E3

(Y/N) | 10 (40%)/15

(60%) | 21 (41%)/30

(59%) | 0.934 |

|

Unknown

(Y/N) | 4 (16%)/21 (84%) | 21 (41%)/30

(59%) | 0.038 |

|

Extraintestinal

manifestations (Y/N) | 0 (0%)/25 (100%) | 11 (22%)/40

(78%) | 0.013 |

|

Musculoskeletal | - | 7 (14%) | |

|

Ankylosing

spondylitis | - | 1 (2%) | |

|

Aphthous

ulcer | - | 1 (2%) | |

|

Pyoderma

gangrenosum | - | 1 (2%) | |

|

Uveitis | - | 1 (2%) | |

| Current

therapya | | | |

|

None

(Y/N) | 0 (0%)/25 (100%) | 12 (24%)/39

(76%) | 0.007 |

|

5-ASA only

(Y/N) | 9 (36%)/16 (64%) | 31 (61%)/20

(39%) | 0.042 |

|

5-ASA with

thiopurine (Y/N) | 16 (64%)/9 (36%) | 8 (16%)/43 (84%) | <0.001 |

|

Advanced

therapy (Y/N) | 0 (0%)/25 (100%) | 0 (0%)/51 (100%) | - |

| Management | | | |

|

Medical

only | 25 (100%) | 44 (86%) | 0.050 |

|

Surgical

intervention | - | 7 (14%) | |

| Outcome | | | |

|

Recovered on

medical therapy alone Y/N | 25 (100%)/0(0%) | 44 (86%)/7 (14%) | 0.050 |

|

Underwent

surgery and recovered | - | 4 (8%) | |

|

Underwent

surgery but did not survive | - | 3 (6%) | |

| Duration of hospital

stay; median (range) days | NA | 8 (2-46) | |

|

<4

days | - | 2 (4%) | |

|

4-5

days | - | 44 (86%) | |

|

>15

days | - | 5 (10%) | |

Patients with flares. Among the 51 patients

with ASUC included in the present study, 27 (53%) patients were

male and the median age of the patients was 38 years (range, 16-65

years). The majority of the patients belonged to class II (upper

lower) of the modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale. The majority

of the patient had extensive colitis (E3) (21 patients, 41%),

whereas extra-intestinal manifestations (EIM) were observed in 11

(22%) patients, the most common being musculoskeletal

manifestations (7 patients, 14%) (Table

I). Of note, 31 (61%) of the patients were on 5-ASA compounds

before the episode of flares, while 8 (16%) patients were on a

combination of 5-ASA and azathioprine, and remainder of the

patients were not on any form of therapy or had terminated

treatment. While the condition of the majority of the treated

patients improved with medical management (86%), 14% of the

patients (7/51 patients) required surgery.

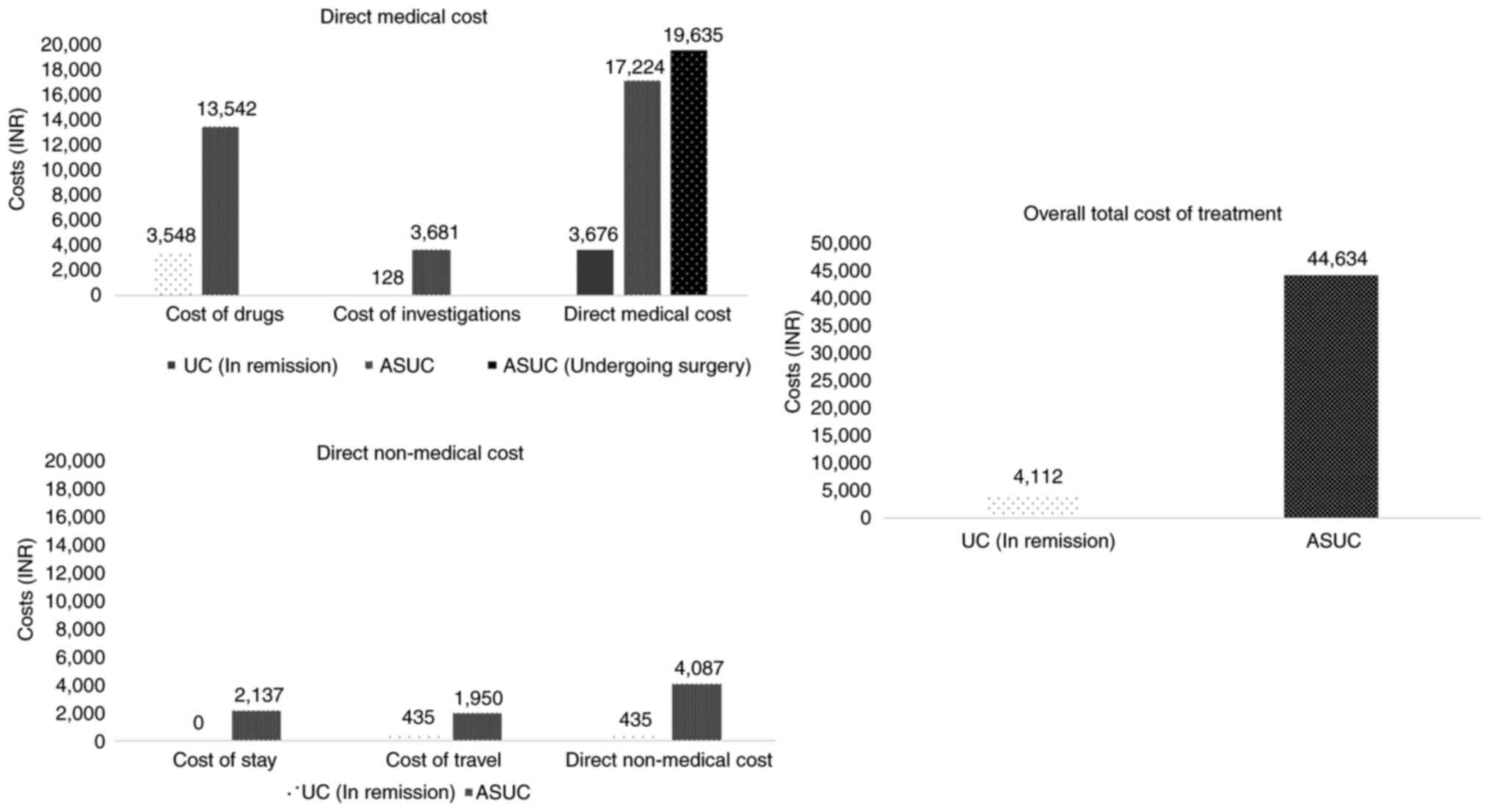

Cost analysis. UC cases in

remission

Cost analysis of the patients with UC in remission

revealed the average monthly expense due to direct medical costs to

be 3,676/- INR, which included the cost of drugs (3,548/- INR), as

well as investigations (128/- INR). The average direct non-medical

cost was 435/- INR, which included only the travelling cost (435/-

INR), as none of the patients in remission incurred additional

expenses on accommodation during their OPD visits (Fig. 1). The average additional indirect

cost incurred by the patients due to lost job earnings during the

treatment period was negligible, as the majority of the patients

could adjust their leave periods for planned hospital visits and

did not lose any daily wages. Overall, the total per capita average

monthly cost of treatment for patients with UC in remission in a

tertiary government setup was calculated to be 4,112/- INR

(Table II).

| Table IICost of care for patients with UC in

remission compared to patients with ASUC. |

Table II

Cost of care for patients with UC in

remission compared to patients with ASUC.

| Cost-of-illness | Patients with UC in

remission (n=25) | Patients with ASUC

(n=51) |

|---|

| Direct medical

cost | 3,676/- (89.40%) | 20,038/-

(44.89%) |

| Cost of drugs | 3,548/- (86.28%) | 16,357/-

(36.65%) |

| Cost of

investigations | 128/- (3.12%) | 3,681/- (8.24%) |

| Direct non-medical

cost | 435/- (10.58%) | 4,087/- (9.16%) |

| Cost of stay | 0/- (0%) | 2,137/- (4.79%) |

| Cost of travel | 435/- (10.58%) | 1,950/- (4.37%) |

| Indirect cost | 1/- (0.02%) | 20,509/-

(45.95%) |

| Total cost | 4,112/- | 44,634/- |

Patients with flares. For the management of

an episode of ASUC, the average direct medical cost was 20,038/-

INR, which included the cost of medical and surgical management

(16,357/- INR), as well as cost of investigations (3,681/- INR). An

additional per patient cost of 20,500/- INR incurred among patients

undergoing surgery for the management of cases of ASUC. The average

direct non-medical cost was 4,087/- INR, including the cost of stay

during hospitalisation (2,137/- INR) and travelling costs (1,950/-

INR). The average additional indirect costs incurred by the

patients and their attendants due to lost job earnings during the

treatment period was 20,509/- INR. Overall, the total per capita

average cost of treatment for an episode of ASUC in a tertiary

government setup was calculated to be 44,634/- INR (Table II). There was a significant

difference (P<0.001) in the total cost of therapy among those

who were managed conservatively with medical therapy alone vs.

those who underwent surgical management. The total cost of therapy

for the medically managed cases (n=44/51 patients, 86%) was

estimated to be 19,615/- INR (15,150.5-27,034.5 INR), while the

cost for those managed with surgical resection (n=7/51 patients,

14%) was 1,62,705/- INR (78,296-2,03,663 INR) (Table III).

| Table IIIDuration of hospital stay and

cost-of-treatment among patients with ASUC (n=51) managed medically

vs. surgically. |

Table III

Duration of hospital stay and

cost-of-treatment among patients with ASUC (n=51) managed medically

vs. surgically.

| Hospital

stay/costs | Patients with ASUC

managed medically (n=44) | Patients with ASUC

managed surgically (n=7) | P-value |

|---|

| Duration of

hospital stay, days (IQR) | 7 (5.5-10.5) | 14 (10.5-26) | 0.030 |

| Cost of treatment

(IQR) | 19,615/-

(15,150.50-27,034.50) | 162,705/-

(78,296-203,663) | <0.001 |

The majority of the patients were admitted for 4-15

days in the hospital (86%), while those who underwent surgery had a

significantly longer hospitalisation period (P=0.030). The median

duration of patient admission was 8 days (IQR, 6-11 days). The

median duration of hospital stays for patients managed with

surgical resection (n=7/51 patients, 14%) was 14 days (IQR,

10.5-26), which was significantly longer (P=0.030) than the median

duration of hospital stays for the patients who were managed only

medical therapy alone (n=44/51 patients, 86%; median days of

hospital stay, 7 days; IQR, 5.5-10.5) (Table III).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the cost of

managing patients with UC during flares is almost 11-fold the cost

of managing patients with UC in remission, which highlights the

importance of stringent disease control not only to decrease

overall patient morbidity and improve quality of life, but also to

lessen the overall financial burden. The cost of flares increases

further if there is a need for surgical treatment. For patients

with UC in remission, the direct medical cost (mostly contributed

by the cost of drug) was responsible for almost 90% of the total

cost of care, while the direct non-medical cost due to stay and

travel during patient OPD follow-up was almost 10%; the indirect

cost was negligible. In patients with acute flares with ASUC, the

direct non-medical cost was ~10%. However, the direct medical cost

due to drugs, surgery and investigations and the indirect cost due

to the loss of wages almost equally contributed (~45% each) to the

cost of illness.

Previous studies from Asia highlight similar trends

of cost-of-illness in patients with UC. Kamat et al

(11) computed the annual median

cost of patients with UC in remission and relapse in southern India

to be 43,140/- and 52,436.5/- INR, roughly translating into monthly

cost of 3,595/- and 4,370/- INR, respectively. Direct costs of UC

management were 84% compared to almost 100% observed in the

patients with UC in remission in the present study (9). The recent study from Iran by Pakdin

et al (12) estimated the

mean annual costs for patients with UC to be US$ 1,077/- (~7,514/-

INR per month). In direct medical costs, the cost of medication

contributed to the majority of expenses (32%), while overall

indirect costs due to both short-term and long-term disability

contributed to major costs per patient (58%) among UC cases

(12). The high financial impact

resulting from short-term disability due to the temporary

absenteeism of patients with ASUC and their caregivers was also a

major determinant of cost-of-illness in the present study

(45.95%).

The annual health care costs for patients with UC in

remission in India are still lower than those estimated in western

countries. The cost analysis of European IBD Inception cohort's 10

years follow-up evaluation revealed the annual per patient

expenditure for patients with UC to be €1524/- (~11,878/- INR per

month); among which the most costly contributions were due to

medical and surgical hospitalisation (45%) (13). In the USA, the mean annual cost per

patient with UC was calculated to be US$ 5,066/- (~35,343/- INR per

month) (14). However, in the

present study, none of the included subjects among the UC with

remission group were maintained on newer advanced therapies, which

could have underestimated the financial impact of maintenance

therapy.

Flares of IBD negatively affect the quality of life

of patients with UC. The severity of the flares has a direct

bearing on the financial burden inflicted by the disease. Bassi

(15), in a study conducted in the

UK, demonstrated that when compared with quiescent cases of IBD,

disease relapse was associated with a 2-3-fold increase in costs

for non-hospitalised cases and a 20-fold increase in costs for

hospitalised cases (15). In the

present study as well, disease flares increased the cost of care of

treatment by 11-fold and highlighted role of hospitalisation in

major direct cost of care. The cost of flare requiring

hospitalisation was estimated in a recent systematic review and

meta-analysis across various continents for patients with UC

(16). This ranges from US$ 187/-

(~15,655/- INR) in Asia to US$ 3,874/- (~324,326/- INR) in the USA.

In Europe, the mean cost of in-hospital care is US$ 1,236/-

(~103,476/- INR) compared to 44,634/- INR in the present study

(16).

The presents study demonstrated that the maximum

financial burden in the care of patients with UC during periods of

exacerbation was due to the lost productivity and absenteeism of

patients and their caregivers, which translates into an indirect

cost of care. Studies from western countries have highlighted

similar results; for patients with UC belonging to the working-age

population, the indirect cost burden may be greater than the direct

cost burden to the patient (17,18).

These findings highlight the need for the financial security system

to tide over the state of acute financial crises during the period

of hospitalisation for patients with acute UC flares. Other than

stringent measures to control disease activity, social awareness of

the disease and the collective effort of society to support for

patients with IBD is required; this also emphasizes the need for

health insurance, IBD patient support groups and financial support

schemes for patients with IBD. Country-specific costs of medication

differ and the inclusion of specific drugs in government or private

insurance schemes empowers patients with their right to

healthcare.

The are some limitations to the present study which

should be mentioned. There is a possibility of a selection bias due

to the inclusion of only a government tertiary referral centre in

north India; this may have led to the underestimation of the costs

due to the disproportionate representation of different social

classes when compared to a private setup. Furthermore, none of the

patients in remission was on advanced therapy or had undergone

surgery in the past, which thus limits cost analysis to these

subsets of patients. The costs of travel were standardised as per

the distance from the hospital for public transport and could have

underestimated the actual costs if the patients used private

transport for their comfort and ease. In addition, the study may

not have addressed the issues and costs to the caregivers who

participate in the care of patients with flares.

However, the findings of the present study may prove

helpful to treating physicians and may aid in the identification of

the cost of managing flares. The findings presented herein are also

a reminder that the cost of flares is not only limited to morbidity

and mortality, but is also financial. To be on continuous treatment

with maintenance therapy is also a financially prudent choice. It

should also be noted that a large number of patients with flares

were not on therapy, having terminated therapy with the improvement

of symptoms.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

VS, VSR, UD and ANP developed the study protocol. VS

and ANP conceptualised the study. AIY, VSR and PP were involved in

data collection. AIY was involved in data analysis. AIY, VS and AP

were involved in data interpretation. VS and UD provided resources

(stationary and data collection tools). AIY and VS were involved in

the writing of the manuscript. VSR, VS and AP confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the institutional

Ethics Committee of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education

and Research, Chandigarh, India (INT/IEC/2022/000488) and written

informed consent was obtained from participants/legal guardians

prior to inclusion.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Burisch J, Claytor J, Hernandez I, Hou JK

and Kaplan GG: The cost of inflammatory bowel disease care: How to

make it sustainable. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 23:386–395.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Aswani-Omprakash T, Sharma V, Bishu S,

Balasubramaniam M, Bhatia S, Nandi N, Shah ND, Deepak P and

Sebastian S: Addressing unmet needs from a new frontier of IBD: The

South Asian IBD Alliance. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 6:884–885.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Balasubramaniam M, Nandi N,

Aswani-Omprakash T, Sebastian S, Sharma V and Deepak P: South Asian

Ibd Alliance Board Of Directors. Identifying care challenges as

opportunities for research and education in inflammatory bowel

disease in South Asia. Gastroenterology. 163:1145–1150.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rana VS, Mahajan G, Patil AN, Singh AK,

Jearth V, Sekar A, Singh H, Saroch A, Dutta U and Sharma V: Factors

contributing to flares of ulcerative colitis in North India-a

case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 23(336)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Noor NM, Lee JC, Bond S, Dowling F,

Brezina B, Patel KV, Ahmad T, Banim PJ, Berrill JW, Cooney R, et

al: A biomarker-stratified comparison of top-down versus

accelerated step-up treatment strategies for patients with newly

diagnosed Crohn's disease (PROFILE): A multicentre, open-label

randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

9:415–427. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Bayoumy AB, Mulder CJJ, Ansari AR, Barclay

ML, Florin T, Kiszka-Kanowitz M, Derijks L, Sharma V and de Boer

NKH: Uphill battle: Innovation of thiopurine therapy in global

inflammatory bowel disease care. Indian J Gastroenterol. 43:36–47.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pal P, Banerjee R, Vijayalaxmi P, Reddy DN

and Tandan M: Depression and active disease are the major risk

factors for fatigue and sleep disturbance in inflammatory bowel

disease with consequent poor quality of life: Analysis of the

interplay between psychosocial factors from the developing world.

Indian J Gastroenterol. 43:226–236. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sharma V, Shukla J, Suri V, Jena A,

Mukerjee A, Mandavdhare HS, Bhalla A and Dutta U: Cost concerns,

not the guidelines, drive clinical care of IBD during COVID

pandemic in a resource limited setting. Expert Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 15:465–466. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Travis SP, Farrant JM, Ricketts C, Nolan

DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MG and Jewell DP: Predicting outcome

in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 38:905–910. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ain SN, Khan ZA and Gilani MA: Revised

kuppuswamy scale for 2021 based on new consumer price index and use

of conversion factors. Indian J Public Health. 65:418–421.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kamat N, Ganesh Pai C, Surulivel Rajan M

and Kamath A: Cost of illness in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig

Dis Sci. 62:2318–2326. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Pakdin M, Zarei L, Bagheri Lankarani K and

Ghahramani S: The cost of illness analysis of inflammatory bowel

disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 23(21)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Odes S, Vardi H, Friger M, Wolters F,

Russel MG, Riis L, Munkholm P, Politi P, Tsianos E, Clofent J, et

al: Cost analysis and cost determinants in a european inflammatory

bowel disease inception cohort with 10 years of follow-up

evaluation. Gastroenterology. 131:719–728. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ,

Ollendorf DA, Sandler RS, Galanko JA and Finkelstein JA: Direct

health care costs of crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US

children and adults. Gastroenterology. 135:1907–1913.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bassi A, Dodd S, Williamson P and Bodger

K: Cost of illness of inflammatory bowel disease in the UK: A

single centre retrospective study. Gut. 53:1471–1478.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Van Linschoten RCA, Visser E, Niehot CD,

Van Der Woude CJ, Hazelzet JA, Van Noord D and West RL: Systematic

review: Societal cost of illness of inflammatory bowel disease is

increasing due to biologics and varies between continents. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther. 54:234–248. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Cohen RD, Yu AP, Wu EQ, Xie J, Mulani PM

and Chao J: Systematic review: The costs of ulcerative colitis in

Western countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 31:693–707.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Khalili H, Everhov ÅH, Halfvarson J,

Ludvigsson JF, Askling J, Myrelid P, Söderling J, Olen O and

Neovius M: SWIBREG Group. Healthcare use, work loss and total costs

in incident and prevalent Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis:

Results from a nationwide study in Sweden. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

52:655–668. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|