The endothelium lines the interior of blood vessels

and functions as a barrier to maintain the movement of fluids,

nutrients and immune cells between the bloodstream and surrounding

tissues (1,2). It is involved in homeostasis, vascular

contraction and cell growth regulation (3). Compromised endothelial function leads

to vasoconstriction, thrombosis and increased permeability; which

in turn contributes to the development of cardiovascular, metabolic

and inflammatory lung disease (4,5).

In the lung, the endothelium maintains the blood-air

barrier required for gas exchange and controls the vascular tone

through the release of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors.

Furthermore, it modulates immune responses by adhesion molecule and

cytokine regulation. In the eye, the endothelium forms the

blood-retinal barrier, and regulates fluid and solute transport

between the aqueous humor and the corneal stroma. Damage to corneal

endothelial cells may lead to impaired fluid regulation, corneal

clouding, vision loss and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy

(6-9).

The dysfunctional endothelium becomes pro-thrombotic

by releasing von Willebrand factor, which contributes to thrombosis

and vascular disease (17,18). Under normal physiological conditions,

endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) produces NO from

L-arginine in the presence of tetrahydrobiopterin. NO is often

decreased due to an increase in the levels of oxidative stress

(19,20). This disruption in the electron

transport process of the enzyme leads to the generation of

superoxide (21,22). NO maintains vascular homeostasis,

promotes vasodilation, inhibits platelet aggregation and reduces

inflammation (23). Inflammatory

cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) activate nuclear factor

kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) (24) and triggers inflammation, which in

severe cases may lead to endothelial apoptosis or necrosis

(25).

Inflammation is a complex biological mechanism which

involves immune cells, blood vessels, and molecular mediators

(e.g., microRNAs, adipokines and inflammasomes); to eliminate cell

injury, remove necrotic cells, and initiate tissue repair (26). Acute inflammation is an immediate,

adaptive response with limited specificity caused by noxious

stimuli (e.g., infection and tissue damage) and protects against

infection (27,28). Chronic inflammation has been

associated with cancer, diabetes, neurodegenerative disease,

pulmonary and autoimmune disease (29,30). It

can potentially damage healthy cells, tissues and organs; since it

promotes fibrosis, vascular damage, and immune dysregulation

(31). Growth hormone (GH)-releasing

hormone (GHRH), which regulates the release of GH from the anterior

pituitary gland, promotes inflammation (32).

Targeted pharmacological interventions are required

to restore endothelial function in cardiovascular, renal, metabolic

and respiratory disorders (33).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, β blockers,

dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel blockers, anti-oxidative

agents (e.g., vitamins C and E, and N-acetylcysteine),

phosphodiesterase inhibitors, statins, angiotensin, bradykinin and

eNOS transcription enhancer exhibit strong potential to ameliorate

endothelial dysfunction (24).

Emerging evidence suggests that growth

hormone-releasing hormone antagonists (GHRHAnts), synthetic

somatostatin analogues (SSAs) and never in mitosis A-related kinase

2 inhibition may enhance endothelial function in in vitro

and in vivo models of lung endothelial injury (34-37).

They can inhibit the the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and

counteract endothelial hyper-permeability (38). Furthermore, SSAs downregulate VEGF

(39) and modulate tight junctions

(40,41).

GH, also known as somatotropin, is secreted by

somatotropic cells which are located in the anterior lobe of the

pituitary gland (42). This peptide

hormone is involved in growth and metabolic regulation, affecting

various physiological systems (e.g., neural, reproductive, immune,

cardiovascular and pulmonary) (32).

The GH level increases throughout childhood, reaching their peak

during adolescence, stimulating the development of bone and

cartilage (43). Following puberty,

GH continues to maintain body composition, fat balance, muscle,

bone tissue, insulin and blood sugar levels (44).

GH stimulates lipolysis, protein synthesis, free

fatty acid and glycerol levels, which contribute to decrease fat

body mass (48). It also contributes

to insulin resistance, particularly in type 1 diabetes (49). Furthermore, GH regulates fluid

homeostasis by activating the renin-angiotensin system and

stimulating distal renal tubular reabsorption, which leads to

sodium and fluid retention (50).

The multifaceted actions of GH highlight its indispensable role in

health (51).

GHD is a condition characterized by inadequate

secretion of GH from the anterior pituitary gland. In children, GHD

manifests as short stature and growth failure, often accompanied by

midface hypoplasia and increased truncal adiposity (54). Severe GHD may be apparent early in

life with a significant reduction in height velocity (43) and can be congenital or acquired due

to brain tumor, head trauma, or radiation therapy. Isolated GHD

(IGHD) is linked to gene mutations [e.g., GH1 and GHRH receptor

(GHRHR) gene] (55). IGHD type II is

an autosomal dominant disorder, caused by GH1 mutations that affect

the splicing of exon 3(56). This

leads to the production of an abnormal GH (17.5 kDa) isoform, which

disrupts hormone trafficking (57).

In adults, GHD results from structural pituitary or

hypothalamic disorder or cranial irradiation (58). Adult-onset GHD is associated with a

cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including increased

adiposity (particularly visceral fat), reduced muscle strength,

impaired psychological well-being, insulin resistance, adverse

lipid profiles and reduced bone mineral density (59). Patients may experience depression,

difficulty concentrating, memory issues and anxiety or emotional

distress. GH replacement therapy has been shown to reverse a number

of these biological changes, improving body composition and overall

health status (60).

Gigantism is characterized by abnormally high linear

growth due to excessive GH and IGF-1 levels prior to the epiphyseal

growth plates fuse during childhood (61). In the majority of cases, gigantism is

caused by a benign (non-cancerous) pituitary tumor, known as an

adenoma, that hyper-secretes GH (62). Genetic mutations are also associated

with the formation of pituitary tumors, leading to gigantism

(63). Excessive hypothalamic GHRH

levels may activate mutations in hypothalamic GHRH-neurons

(64). The symptoms of gigantism

include accelerated growth velocity, tall stature, enlarged hands

and feet, soft-tissue thickening, prognathism (protruding jaw),

coarse facial features, muscle weakness, cardiovascular issues,

joint issues and headaches (65).

In the event that excessive GH secretion occurs

following epiphyseal closure, the condition is referred to as

acromegaly, which presents with similar features to gigantism but

without increased linear growth. When the body produces excessive

GH levels due to a non-cancerous tumor in the pituitary gland, it

can lead to acromegaly (61). This

hormone imbalance causes bones and tissues to grow to a greater

extent than usual and has been associated with high blood pressure,

diabetes and heart disease (66).

Excessive GH secretion increases the risk of

developing colon, thyroid, gastric, breast, and urinary tract

cancers (67). Specific genetic

polymorphisms within the GH/IGF-1 pathway may increase

susceptibility to malignancies (e.g., breast cancer) (68). Conversely, GH and IGF-1 deficits are

associated with a diminished incidence of tumor promotion (69), associated to IGF-1/IGF-1R (70). IGF-1 promotes cell proliferation,

differentiation and growth (71).

GHRHAnts were developed by Dr A.V. Schally

(1926-2024) (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1977) to

suppress malignancies (72,73); however, they have the potential to be

used in a broader variety of disorders (74,75).

These synthetic peptides reduce pituitary GH release and hepatic

IGF-1 levels, and act directly on peripheral tissues by blocking

both GHRHR and its splice variant SV1 (72,76-79).

The activation of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)/protein

kinase A (PKA) response element-binding protein signaling pathway

leads to GH gene transcription and downstream IGF-1 production.

GHRHAnts modulate key cellular processes involved in inflammation,

oxidative stress, fibrosis and barrier integrity (80).

In peripheral tissues, GHRHAnts exert their

protective effects by suppressing the activation of NF-κB (76) and inhibiting mitogen-activated

protein kinases (MAPKs), such as ERK1/2 and p38 (81,82).

Moreover, GHRHAnts suppress JAK/STAT signaling, particularly STAT3

activation, which is implicated in cytokine-driven inflammation and

fibrosis (83). Those peptides can

also mitigate ER stress through the induction of the unfolded

protein response (UPR) (84),

promote antioxidant defenses, and preserve barrier integrity

(85).

GHRHAnts prevent angiogenesis by reducing matrix

metalloproteinases (MMPs; MMP-2 and MMP-9) (97) and VEGF, which are vital for tumor

invasion and metastasis (98).

Moreover, they exhibit minimal systemic toxicity and do not

significantly suppress basal GH or IGF-1 levels at therapeutic

doses (73). It has been suggested

that GHRHAnts may serve as promising candidates for the treatment

of cancer, either as monotherapy or in combination with

chemotherapy, targeted agents, or immunotherapy, due to their

capacity to target multiple tumor-promoting pathways (99).

Barrier integrity is essential for maintaining

homeostasis in the alveolar-capillary barrier (100), which is involved in the

pathogenesis of complex disorders, such as ALI and ARDS (101). Those are severe and

life-threatening pulmonary disorders characterized by uncontrolled

pulmonary inflammation, increased vascular permeability,

alveolar-capillary barrier disruption and impaired gas exchange

(102). These conditions are

frequently caused by infections, sepsis, trauma, or inhalation of

toxic substances. Despite advances in supportive care,

pharmacological options for ALI/ARDS remain limited. Recent

research suggests that GHRHAnts protect against ALI and sepsis by

simultaneously modulating key inflammatory processes and supporting

the preservation of lung barrier integrity (103). MIA-602 has been demonstrated to

exert protective effects in various ALI experimental models,

including lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced endotoxemia and

bleomycin-induced lung damage (104). GHRHAnts maintain vascular integrity

by enhancing junctional stability and reducing pulmonary edema

(105). Treatment with GHRHAnts has

been shown to result in enhanced arterial oxygenation, lung injury

amelioration and improved survival rates in animal experiments

(103).

Pulmonary fibrosis is a progressive life-threatening

condition, which is characterized by the deposition of excessive

extracellular matrix and alveolar architecture destruction, which

result in loss of lung function (106). The chronic activation of

fibroblasts and myofibroblasts is stimulated by profibrotic

cytokines, such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (107). Experimental evidence demonstrates

that GHRHAnts exert anti-fibrotic effects (108). GHRHAnts (e.g., MIA-602 and MIA-690)

have demonstrated a marked ability to inhibit key fibrotic

processes by suppressing TGF-β1 signaling, preventing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and decreasing fibroblast

proliferation and differentiation into myofibroblasts (72,109,110).

These peptides can also counteract the expression of profibrotic

markers such as α-smooth muscle actin, fibronectin, type I

collagen, and they can limit the deposition of collagen in lung

tissue (76). In a previous study

using a bleomycin-induced mouse model of lung fibrosis, GHRHAnts

were shown to ameliorate fibrosis, improve lung compliance and

preserve alveolar architecture (108).

The BBB is a highly selective and specialized

structure that regulates the exchange of molecules between the

bloodstream and the central nervous system (111). The disruption of this barrier can

lead to neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative disorders,

including multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, ischemic

stroke and Alzheimer's disease (112). The increased permeability of the

BBB permits the entry of immune cells, cytokines and other harmful

substances into the brain, triggering chronic inflammation,

impairing neuronal function and exacerbating vascular damage

(113).

There is experimental evidence to indicate that

GHRHAnts can protect BBB integrity and reduce neuroinflammatory

damage (114). In models of central

nervous system injury, these peptides reduce the expression of

inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α), suppress microglial

and astrocyte activation, and block NF-κB (32). GHRHAnts stabilize the BBB and protect

paracellular barrier integrity by maintaining tight junction

protein (such as occludin and claudin-5) expression (115).

SST, also known as GH-inhibiting hormone, exerts

potent regulatory effects throughout the body (116). It functions as a neurotransmitter

in the central nervous system (117), and exerts effects, at least

partially, via the GH/IGF-1 axis (118). SST, which is affected by glucose,

inhibits GH and thyroid-stimulating hormone secretion (119).

SSAs inhibit the production of GH and serotonin,

which are used in managing GH-related disorders. Excessive GH

secretion from pituitary adenomas leads to elevated levels of

IGF-1(120). SSAs bind to SST

receptors (SSTRs) on the surface of tumors in acromegaly and

gigantism to inhibit the release of GH and reduce IGF-1 production

(121).

Neuroendocrine tumors and GH-dependent cancers

express SSTRs and respond to octreotide, which exerts

anti-proliferative effects through receptor-mediated apoptosis, the

inhibition of angiogenesis and the suppression of GH (126). It has been demonstrated that

octreotide preserves endothelial barrier function, reduces reactive

oxygen species (ROS) generation, and attenuates inflammatory

responses in a murine model of LPS-induced ALI (34).

Octreotide may exert protective effects on vascular

endothelial cells through the activation of the UPR and enhances

the expression of ER chaperone proteins (e.g., binding

immunoglobulin protein and glucose-regulated protein 94), leading

to the stabilization of cytoskeletal components (127). When activating transcription factor

6 (ATF6) is pharmacologically inhibited, the beneficial effects of

octreotide on endothelial permeability, ROS generation and improved

cytoskeletal organization are virtually diminished (128). These findings suggest that

octreotide confers protective effects on the vascular endothelium

and may be useful towards inflammation-related vascular

disorders.

Lanreotide is a long-acting SSA that exerts

pharmacological effects by binding predominantly to SSTR2 and

SSTR5(129), which are

overexpressed in GH-secreting pituitary adenomas. Lanreotide has

emerged as a valuable non-surgical therapy in acromegaly or in

patients with residual disease following pituitary surgery

(130) and may provide improved

visual symptoms due to decreased tumor mass (131). The long half-life of lanreotide

(23-30 days) and subcutaneous depot formulation offer convenient

dosing, rendering it suitable for chronic conditions requiring

long-term management (132).

Recent research suggests that lanreotide exerts

protective effects against LPS-induced endothelial dysfunction both

in vitro and in vivo. LPS typically induces

endothelial hyperpermeability, leading to increased vascular

leakage (133). Lanreotide reduces

ROS generation in endothelial cells exposed to LPS, highlighting

its role in mitigating oxidative stress. Furthermore, this

FDA-approved analog ameliorated lung inflammatory disease (134).

Pasireotide, a second-generation SST analog, is

distinguished by its high affinity for multiple SSRT subtypes

(SSTR1-5) (135,136), and it is used in patients resistant

to first-generation SSA (octreotide or lanreotide) (137,138).

Pasireotide has been approved for use in patients with active

acromegaly and Cushing's disease (139). Safety assessments reveal that

pasireotide is generally well tolerated. The most frequently

observed adverse event is hyperglycemia, a known effect of SSAs due

to reduced insulin secretion; this can be managed with standard

antidiabetic therapies. The tumor expression of SSTRs and dopamine

receptors may predict the responsiveness to pasireotide in

corticotropinomas (140).

Recent research suggests that pasireotide exerts

potent protective effects on endothelial barrier integrity

(35) and ALI, since it mitigates

LPS-induced inflammation by preserving barrier function, reducing

cytotoxicity, reinforcing antioxidant defenses, and dampening

inflammatory responses. Mechanistically, pasireotide attenuates

MAPK and JAK/STAT inflammatory signaling. These antioxidative and

anti-inflammatory actions may synergistically stabilize endothelial

junctions and suppress tissue injury (34,35,134,141).

SSAs are available in both short-acting and

long-acting formulations. Octreotide is available in subcutaneous

and intramuscular forms (122),

while lanreotide is delivered via deep subcutaneous injection

(132). Pasireotide is administered

either subcutaneously or as a long-acting depot injection (142,143)

to modulate GH-related abnormalities (144).

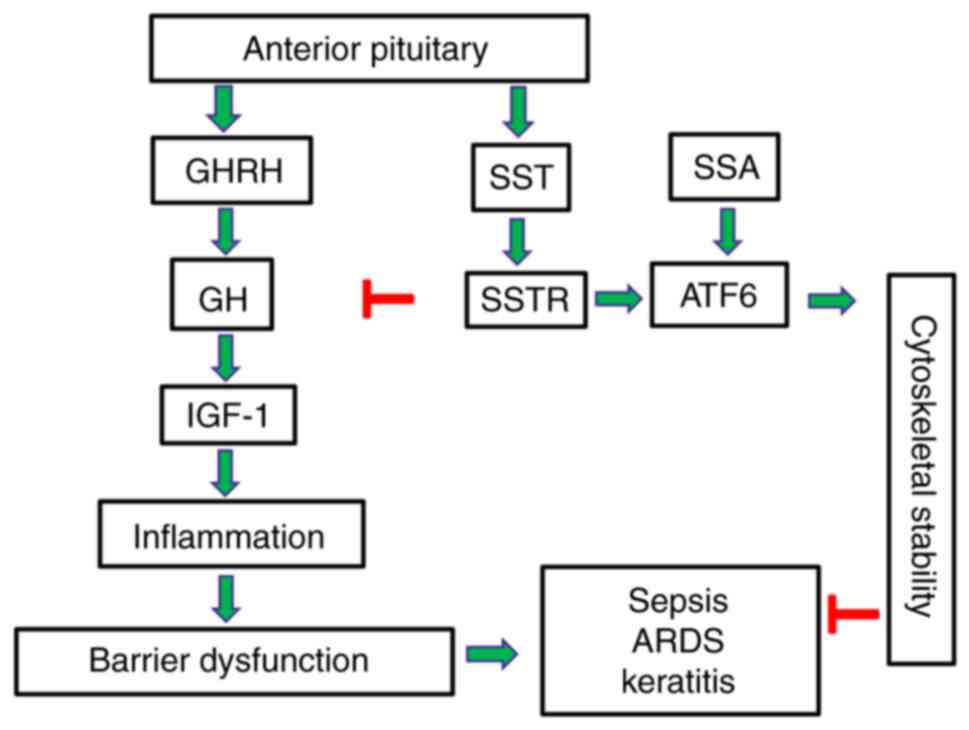

Targeted GH modulation presents an exciting

therapeutic intervention to alleviate human disease, and the

development of synthetic analogs to achieve normal GH levels has

been proven to be an effective strategy for the treatment of

cancers and acromegaly in clinical practice (Table I). Recent preclinical studies suggest

that SSAs and GHRHAnts counteract disorders related to endothelial

barrier dysfunction utilizing ATF6 (127,128).

Based on this information, experimental models of targeted ATF6

modulation will be developed to assist in designing GH-related

pharmacotherapies. Those advanced approaches will be able to

utilize the beneficial properties of UPR activation to

strategically ameliorate endothelial-dependent disorders which may

affect the brain, lungs and eyes (Fig.

1).

Not applicable.

Funding: The present study was supported by the National

Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National

Institutes of Health under Award no. R03AI176433; and an

Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute

of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health

under Award Number P20 GM103424-21.

Not applicable.

SF, MMRS and MS were involved in the writing and

preparation of the original draft of the manuscript. NB was

involved in the conceptualization and supervision of the study, in

the reviewing and editing of the manuscript, in funding acquisition

and in project administration. All authors have read and approved

the final manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Hennigs JK, Matuszcak C, Trepel M and

Körbelin J: Vascular endothelial cells: Heterogeneity and targeting

approaches. Cells. 10(2712)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Saravi B, Goebel U, Hassenzahl LO, Jung C,

David S, Feldheiser A, Stopfkuchen-Evans M and Wollborn J:

Capillary leak and endothelial permeability in critically ill

patients: A current overview. Intensive Care Med Exp.

11(96)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rubanyi GM: The role of endothelium in

cardiovascular homeostasis and diseases. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 22

(Suppl 4):S1–S14. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN and Bobryshev

YV: Endothelial barrier and its abnormalities in cardiovascular

disease. Front Physiol. 6(365)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kopaliani I, Elsaid B, Speier S and

Deussen A: Immune and metabolic mechanisms of endothelial

dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 25(13337)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Vassiliou AG, Kotanidou A, Dimopoulou I

and Orfanos SE: Endothelial damage in acute respiratory distress

syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 21(8793)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Cunha-Vaz J, Bernardes R and Lobo C:

Blood-retinal barrier. Eur J Ophthalmol. 21 (Suppl 6):S3–S9.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Goncalves A and Antonetti DA: Transgenic

animal models to explore and modulate the blood brain and blood

retinal barriers of the CNS. Fluids Barriers CNS.

19(86)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liu X, Zheng T, Zhao C, Zhang Y, Liu H,

Wang L and Liu P: Genetic mutations and molecular mechanisms of

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy. Eye Vis (Lond).

8(24)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang X and He B: Endothelial dysfunction:

Molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. MedComm (2020).

5(e651)2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Siasos G, Gouliopoulos N, Moschos MM,

Oikonomou E, Kollia C, Konsola T, Athanasiou D, Siasou G, Mourouzis

K, Zisimos K, et al: Role of endothelial dysfunction and arterial

stiffness in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes

Care. 38:e9–e10. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Steyers CM III and Miller FJ Jr:

Endothelial dysfunction in chronic inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol

Sci. 15:11324–11349. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Poredos P, Poredos AV and Gregoric I:

Endothelial dysfunction and its clinical implications. Angiology.

72:604–615. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sarelius IH and Glading AJ: Control of

vascular permeability by adhesion molecules. Tissue Barriers.

3(e985954)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Aghajanian A, Wittchen ES, Allingham MJ,

Garrett TA and Burridge K: Endothelial cell junctions and the

regulation of vascular permeability and leukocyte transmigration. J

Thromb Haemost. 6:1453–1460. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Peng Z, Shu B, Zhang Y and Wang M:

Endothelial response to pathophysiological stress. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 39:e233–e243. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Goshua G, Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Chang CH,

Zhang H, Bahel P, Baluha A, Bar N, Bona RD, Burns AJ, et al:

Endotheliopathy in COVID-19-associated coagulopathy: Evidence from

a single-centre, cross-sectional study. Lancet Haematol.

7:e575–e582. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

van Hinsbergh VW: Endothelium-role in

regulation of coagulation and inflammation. Semin Immunopathol.

34:93–106. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Xu S, Ilyas I, Little PJ, Li H, Kamato D,

Zheng X, Luo S, Li Z, Liu P, Han J, et al: Endothelial dysfunction

in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases and beyond: from

mechanism to pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev. 73:924–967.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Shaito A, Aramouni K, Assaf R, Parenti A,

Orekhov A, Yazbi AE, Pintus G and Eid AH: Oxidative stress-induced

endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 27(105)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Janaszak-Jasiecka A, Płoska A, Wierońska

JM, Dobrucki LW and Kalinowski L: Endothelial dysfunction due to

eNOS uncoupling: molecular mechanisms as potential therapeutic

targets. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 28(21)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Alp NJ and Channon KM: Regulation of

endothelial nitric oxide synthase by tetrahydrobiopterin in

vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 24:413–420.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Jin RC and Loscalzo J: Vascular nitric

oxide: Formation and function. J Blood Med. 2010:147–162.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Su JB: Vascular endothelial dysfunction

and pharmacological treatment. World J Cardiol. 7:719–741.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang W, Jiang L, Tong X, He H, Zheng Y

and Xia Z: Sepsis-induced endothelial dysfunction: Permeability and

regulated cell death. J Inflamm Res. 17:9953–9973. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liehn EA and Cabrera-Fuentes HA:

Inflammation between defense and disease: Impact on tissue repair

and chronic sickness. Discoveries (Craiova). 3(e42)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Tripathi S, Sharma Y and Kumar D:

Unveiling the link between chronic inflammation and cancer. Metabol

Open. 25(100347)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chavda VP, Feehan J and Apostolopoulos V:

Inflammation: The cause of all diseases. Cells.

13(1906)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E,

Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C, Ferrucci L, Gilroy DW,

Fasano A, Miller GW, et al: Chronic inflammation in the etiology of

disease across the life span. Nat Med. 25:1822–1832.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng

J, Li Y, Wang X and Zhao L: Inflammatory responses and

inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget.

9:7204–7218. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Castellon X and Bogdanova V: Chronic

inflammatory diseases and endothelial dysfunction. Aging Dis.

7:81–89. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Du L, Ho BM, Zhou L, Yip YWY, He JN, Wei

Y, Tham CC, Chan SO, Schally AV, Pang CP, et al: Growth hormone

releasing hormone signaling promotes Th17 cell differentiation and

autoimmune inflammation. Nat Commun. 14(3298)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Chee YJ, Dalan R and Cheung C: The

interplay between immunity, inflammation and endothelial

dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 26(1708)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Fakir S, Kubra KT and Barabutis N:

Octreotide protects against LPS-induced endothelial cell and lung

injury. Cell Signal. 124(111455)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Fakir S, Sigdel M, Sarker MMR and

Barabutis N: Pasireotide exerts anti-inflammatory effects in the

endothelium. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 39(e70306)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Clemens A, Klevesath MS, Hofmann M, Raulf

F, Henkels M, Amiral J, Seibel MJ, Zimmermann J, Ziegler R, Wahl P

and Nawroth PP: Octreotide (somatostatin analog) treatment reduces

endothelial cell dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Metabolism. 48:1236–1240. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Barabutis N and Akhter MS: Involvement of

NEK2 and NEK9 in LPS-induced endothelial barrier dysfunction.

Microvasc Res. 152(104651)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Karalis K, Mastorakos G, Chrousos GP and

Tolis G: Somatostatin analogues suppress the inflammatory reaction

in vivo. J Clin Invest. 93:2000–2006. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Sall JW, Klisovic DD, O'Dorisio MS and

Katz SE: Somatostatin inhibits IGF-1 mediated induction of VEGF in

human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 79:465–476.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Basivireddy J, Somvanshi RK, Romero IA,

Weksler BB, Couraud PO, Oger J and Kumar U: Somatostatin preserved

blood brain barrier against cytokine induced alterations: Possible

role in multiple sclerosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 86:497–507.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Mentlein R, Eichler O, Forstreuter F and

Held-Feindt J: Somatostatin inhibits the production of vascular

endothelial growth factor in human glioma cells. Int J Cancer.

92:545–550. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ayuk J and Sheppard MC: Growth hormone and

its disorders. Postgrad Med J. 82:24–30. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ranke MB: Short and long-term effects of

growth hormone in children and adolescents with GH deficiency.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12(720419)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Sharma R, Kopchick JJ, Puri V and Sharma

VM: Effect of growth hormone on insulin signaling. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 518(111038)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Pech-Pool S, Berumen LC, Martínez-Moreno

CG, García-Alcocer G, Carranza M, Luna M and Arámburo C:

Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) and somatostatin (SST), but not

growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) nor Ghrelin (GHRL),

regulate expression and release of immune growth hormone (GH) from

chicken bursal B-lymphocyte cultures. Int J Mol Sci.

21(1436)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Dehkhoda F, Lee CMM, Medina J and Brooks

AJ: The growth hormone receptor: Mechanism of receptor activation,

cell signaling, and physiological aspects. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 9(35)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ohlsson C, Mohan S, Sjögren K, Tivesten A,

Isgaard J, Isaksson O, Jansson JO and Svensson J: The role of

liver-derived insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocr Rev. 30:494–535.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Kopchick JJ, Berryman DE, Puri V, Lee KY

and Jorgensen JOL: The effects of growth hormone on adipose tissue:

Old observations, new mechanisms. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 16:135–146.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Kim SH and Park MJ: Effects of growth

hormone on glucose metabolism and insulin resistance in human. Ann

Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 22:145–152. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Hansen TK, Møller J, Thomsen K, Frandsen

E, Dall R, Jørgensen JO and Christiansen JS: Effects of growth

hormone on renal tubular handling of sodium in healthy humans. Am J

Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 281:E1326–E1332. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Ricci Bitti S, Franco M, Albertelli M,

Gatto F, Vera L, Ferone D and Boschetti M: GH replacement in the

elderly: Is it worth it? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12(680579)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Reed ML, Merriam GR and Kargi AY: Adult

growth hormone deficiency-benefits, side effects, and risks of

growth hormone replacement. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

4(64)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kim JH, Chae HW, Chin SO, Ku CR, Park KH,

Lim DJ, Kim KJ, Lim JS, Kim G, Choi YM, et al: Diagnosis and

treatment of growth hormone deficiency: A position statement from

Korean endocrine society and Korean Society of pediatric

endocrinology. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 35:272–287.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Alatzoglou KS, Webb EA, Le Tissier P and

Dattani MT: Isolated growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in childhood

and adolescence: Recent advances. Endocr Rev. 35:376–432.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Mullis PE: Genetics of isolated growth

hormone deficiency. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2:52–62.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Kautsar A, Wit JM and Pulungan A: Isolated

growth hormone deficiency type 2 due to a novel GH1 mutation: A

case report. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 11:426–431.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Alatzoglou KS, Kular D and Dattani MT:

Autosomal dominant growth hormone deficiency (type II). Pediatr

Endocrinol Rev. 12:347–355. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Feldt-Rasmussen U and Klose M: Adult

Growth Hormone Deficiency-Clinical Management. In: Endotext

[Internet]. Feingold KR, Ahmed SF, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A,

Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, et

al (eds). MDText.com, Inc., South Dartmouth, MA, 2000.

|

|

59

|

Murray RD: Adult growth hormone

replacement: Current understanding. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 3:642–649.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Papadogias DS, Makras P, Kaltsas GA and

Monson JP: GH deficiency in adults. Hormones (Athens). 2:217–218.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Bello MO and Garla VV: Gigantism and

Acromegaly. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing,

Treasure Island, FL, 2025.

|

|

62

|

Rhee N, Jeong K, Yang EM and Kim CJ:

Gigantism caused by growth hormone secreting pituitary adenoma. Ann

Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 19:96–99. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Hannah-Shmouni F, Trivellin G and

Stratakis CA: Genetics of gigantism and acromegaly. Growth Horm IGF

Res. 30-31:37–41. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Dieguez C, Lopez M and Casanueva F:

Hypothalamic GHRH. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 26:297–303.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

George MM, Eugster EA and Chernausek SD:

Pituitary Gigantism. In: Endotext [Internet]. Feingold KR, Ahmed

SF, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de

Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, et al (eds). MDText.com,

Inc., South Dartmouth, MA, 2020.

|

|

66

|

Quock TP, Chang E, Das AK, Speller A,

Tarbox MH, Rattana SK, Paulson IE and Broder MS: Clinical and

economic burden among older adults with acromegaly in the United

States. J Comp Eff Res. 14(e250076)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Fernandez CJ, Lakshmi V, Kamrul-Hasan ABM

and Pappachan JM: Factors affecting disease control after pituitary

tumor resection in acromegaly: What is the current evidence? World

J Radiol. 17(106438)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Grimberg A: Mechanisms by which IGF-I may

promote cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2:630–635. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Guevara-Aguirre J, Peña G, Acosta W,

Pazmiño G, Saavedra J, Soto L, Lescano D, Guevara A and Gavilanes

AWD: Cancer in growth hormone excess and growth hormone deficit.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 30(e220402)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Simpson A, Petnga W, Macaulay VM,

Weyer-Czernilofsky U and Bogenrieder T: Insulin-Like growth factor

(IGF) pathway targeting in cancer: Role of the IGF axis and

opportunities for future combination studies. Target Oncol.

12:571–597. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Khan MZ, Zugaza JL and Torres Aleman I:

The signaling landscape of insulin-like growth factor 1. J Biol

Chem. 301(108047)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Villanova T, Gesmundo I, Audrito V, Vitale

N, Silvagno F, Musuraca C, Righi L, Libener R, Riganti C, Bironzo

P, et al: Antagonists of growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH)

inhibit the growth of human malignant pleural mesothelioma. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 116:2226–2231. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Schally AV, Cai R, Zhang X, Sha W and

Wangpaichitr M: The development of growth hormone-releasing hormone

analogs: Therapeutic advances in cancer, regenerative medicine, and

metabolic disorders. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 26:385–396.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Cui T, Jimenez JJ, Block NL, Badiavas EV,

Rodriguez-Menocal L, Vila Granda A, Cai R, Sha W, Zarandi M, Perez

R and Schally AV: Agonistic analogs of growth hormone releasing

hormone (GHRH) promote wound healing by stimulating the

proliferation and survival of human dermal fibroblasts through ERK

and AKT pathways. Oncotarget. 7:52661–52672. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Fakir S and Barabutis N: Protective

activities of growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonists against

toxin-induced endothelial injury. Endocrines. 5:116–123.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Zhang C, Cui T, Cai R, Wangpaichitr M,

Mirsaeidi M, Schally AV and Jackson RM: Growth hormone-releasing

hormone in lung physiology and pulmonary disease. Cells.

9(2331)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Annunziata M, Grande C, Scarlatti F,

Deltetto F, Delpiano E, Camanni M, Ghigo E and Granata R: The

growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) antagonist JV-1-36 inhibits

proliferation and survival of human ectopic endometriotic stromal

cells (ESCs) and the T HESC cell line. Fertil Steril. 94:841–849.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Zarandi M, Cai R, Kovacs M, Popovics P,

Szalontay L, Cui T, Sha W, Jaszberenyi M, Varga J, Zhang X, et al:

Synthesis and structure-activity studies on novel analogs of human

growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) with enhanced inhibitory

activities on tumor growth. Peptides. 89:60–70. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Granata R: Peripheral activities of growth

hormone-releasing hormone. J Endocrinol Invest. 39:721–727.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Siejka A, Lawnicka H, Fakir S and

Barabutis N: Growth hormone-releasing hormone in the immune system.

Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 26:457–466. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Barabutis N, Siejka A, Schally AV, Block

NL, Cai R and Varga JL: Activation of mitogen-activated protein

kinases by a splice variant of GHRH receptor. J Mol Endocrinol.

44:127–134. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Barabutis N, Akhter MS, Kubra KT and

Jackson K: Growth hormone-releasing hormone in endothelial

inflammation. Endocrinology. 164(bqac209)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Siejka A, Schally AV and Barabutis N:

Activation of Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3 pathway by growth hormone-releasing hormone. Cell

Mol Life Sci. 67:959–964. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Fakir S, Kubra KT, Akhter MS, Uddin MA,

Sarker MMR, Siejka A and Barabutis N: Unfolded protein response

modulates the effects of GHRH antagonists in experimental models of

in vivo and in vitro lung injury. Tissue Barriers.

13(2438974)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Kubra KT, Akhter MS, Apperley K and

Barabutis N: Growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonist JV-1-36

suppresses reactive oxygen species generation in A549 lung cancer

cells. Endocrines. 3:813–820. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Granata R, Leone S, Zhang X, Gesmundo I,

Steenblock C, Cai R, Sha W, Ghigo E, Hare JM, Bornstein SR and

Schally AV: Growth hormone-releasing hormone and its analogues in

health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 21:180–195. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Akhter MS and Barabutis N: Suppression of

reactive oxygen species in endothelial cells by an antagonist of

growth hormone-releasing hormone. J Biochem Mol Toxicol.

35(e22879)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Populo H, Nunes B, Sampaio C, Batista R,

Pinto MT, Gaspar TB, Miranda-Alves L, Cai RZ, Zhang XY, Schally AV,

et al: Inhibitory effects of antagonists of growth

hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) in thyroid cancer. Horm Cancer.

8:314–324. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Rick FG, Schally AV, Szalontay L, Block

NL, Szepeshazi K, Nadji M, Zarandi M, Hohla F, Buchholz S and Seitz

S: Antagonists of growth hormone-releasing hormone inhibit growth

of androgen-independent prostate cancer through inactivation of ERK

and Akt kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:1655–1660.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Perez R, Schally AV, Popovics P, Cai R,

Sha W, Rincon R and Rick FG: Antagonistic analogs of growth

hormone-releasing hormone increase the efficacy of treatment of

triple negative breast cancer in nude mice with doxorubicin; A

preclinical study. Oncoscience. 1:665–673. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Recinella L, Chiavaroli A, Veschi S, Di

Valerio V, Lattanzio R, Orlando G, Ferrante C, Gesmundo I, Granata

R, Cai R, et al: Antagonist of growth hormone-releasing hormone

MIA-690 attenuates the progression and inhibits growth of

colorectal cancer in mice. Biomed Pharmacother.

146(112554)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Kineman RD: Antitumorigenic actions of

growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 97:532–534. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Letsch M, Schally AV, Busto R, Bajo AM and

Varga JL: Growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) antagonists

inhibit the proliferation of androgen-dependent and -independent

prostate cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100:1250–1255.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Gao FY, Li XT, Xu K, Wang RT and Guan XX:

c-MYC mediates the crosstalk between breast cancer cells and tumor

microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 21(28)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Wu HM, Schally AV, Cheng JC, Zarandi M,

Varga J and Leung PC: Growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonist

induces apoptosis of human endometrial cancer cells through

PKCδ-mediated activation of p53/p21. Cancer Lett. 298:16–25.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Chu WK, Law KS, Chan SO, Yam JC, Chen LJ,

Zhang H, Cheung HS, Block NL, Schally AV and Pang CP: Antagonists

of growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor induce apoptosis

specifically in retinoblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

113:14396–14401. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Buchholz S, Schally AV, Engel JB, Hohla F,

Heinrich E, Koester F, Varga JL and Halmos G: Potentiation of

mammary cancer inhibition by combination of antagonists of growth

hormone-releasing hormone with docetaxel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

104:1943–1946. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Siejka A, Barabutis N and Schally AV: GHRH

antagonist inhibits focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and decreases

expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human

lung cancer cells in vitro. Peptides. 37:63–68. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Rick FG, Seitz S, Schally AV, Szalontay L,

Krishan A, Datz C, Stadlmayr A, Buchholz S, Block NL and Hohla F:

GHRH antagonist when combined with cytotoxic agents induces S-phase

arrest and additive growth inhibition of human colon cancer. Cell

Cycle. 11:4203–4210. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Yeste J, Illa X, Alvarez M and Villa R:

Engineering and monitoring cellular barrier models. J Biol Eng.

12(18)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Su Y, Lucas R, Fulton DJR and Verin AD:

Mechanisms of pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction in acute

lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Chin Med J

Pulm Crit Care Med. 2:80–87. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Sapru A, Flori H, Quasney MW and Dahmer

MK: Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Group.

Pathobiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Pediatr Crit

Care Med. 16 (5 Suppl 1):S6–S22. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Uddin MA, Akhter MS, Singh SS, Kubra KT,

Schally AV, Jois S and Barabutis N: GHRH antagonists support lung

endothelial barrier function. Tissue Barriers.

7(1669989)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Granato G, Gesmundo I, Pedrolli F, Kasarla

R, Begani L, Banfi D, Bruno S, Lopatina T, Brizzi MF, Cai R, et al:

Growth hormone-releasing hormone antagonist MIA-602 inhibits

inflammation induced by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and bacterial

lipopolysaccharide synergism in macrophages and human peripheral

blood mononuclear cells. Front Immunol. 14(1231363)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Akhter MS, Kubra KT and Barabutis N:

Protective effects of GHRH antagonists against hydrogen

peroxide-induced lung endothelial barrier disruption. Endocrine.

79:587–592. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Wilson MS and Wynn TA: Pulmonary fibrosis:

Pathogenesis, etiology and regulation. Mucosal Immunol. 2:103–121.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Midgley AC, Rogers M, Hallett MB, Clayton

A, Bowen T, Phillips AO and Steadman R: Transforming growth

factor-β1 (TGF-β1)-stimulated fibroblast to myofibroblast

differentiation is mediated by hyaluronan (HA)-facilitated

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and CD44 co-localization in

lipid rafts. J Biol Chem. 288:14824–14838. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Zhang C, Cai R, Lazerson A, Delcroix G,

Wangpaichitr M, Mirsaeidi M, Griswold AJ, Schally AV and Jackson

RM: Growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor antagonist modulates

lung inflammation and fibrosis due to bleomycin. Lung. 197:541–549.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Gesmundo I, Pedrolli F, Vitale N, Bertoldo

A, Orlando G, Banfi D, Granato G, Kasarla R, Balzola F, Deaglio S,

et al: Antagonist of growth hormone-releasing hormone potentiates

the antitumor effect of pemetrexed and cisplatin in pleural

mesothelioma. Int J Mol Sci. 23(11248)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Condor Capcha JM, Robleto E, Saad AG, Cui

T, Wong A, Villano J, Zhong W, Pekosz A, Medina E, Cai R, et al:

Growth hormone-releasing hormone receptor antagonist MIA-602

attenuates cardiopulmonary injury induced by BSL-2 rVSV-SARS-CoV-2

in hACE2 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120(e2308342120)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Dotiwala AK, McCausland C and Samra NS:

Anatomy, Head and Neck: Blood Brain Barrier. In: StatPearls

[Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL, 2025.

|

|

112

|

Takata F, Nakagawa S, Matsumoto J and

Dohgu S: Blood-brain barrier dysfunction amplifies the development

of neuroinflammation: Understanding of cellular events in brain

microvascular endothelial cells for prevention and treatment of BBB

dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci. 15(661838)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Galea I: The blood-brain barrier in

systemic infection and inflammation. Cell Mol Immunol.

18:2489–2501. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Jaeger LB, Banks WA, Varga JL and Schally

AV: Antagonists of growth hormone-releasing hormone cross the

blood-brain barrier: A potential applicability to treatment of

brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102:12495–12500.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Barabutis N: Insights on supporting the

aging brain microvascular endothelium. Aging Brain.

1(100009)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

O'Toole TJ and Sharma S: Physiology,

Somatostatin. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing,

Treasure Island, FL, 2025.

|

|

117

|

Reubi JC and Schonbrunn A: Illuminating

somatostatin analog action at neuroendocrine tumor receptors.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 34:676–688. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Shahid Z, Asuka E and Singh G: Physiology,

Hypothalamus. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing,

Treasure Island, FL, 2025.

|

|

119

|

Olarescu NC, Gunawardane K, Hanson TK,

Møller N and Jørgensen JOL: Normal Physiology of Growth Hormone in

Normal Adults. In: Endotext [Internet]. Feingold KR, Ahmed SF,

Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder

WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, et al (eds). MDText.com, Inc.,

South Dartmouth, MA, 2000.

|

|

120

|

Adigun OO, Nguyen M, Fox TJ and

Anastasopoulou C: Acromegaly. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls

Publishing, Treasure Island, FL, 2023.

|

|

121

|

Liu W, Xie L, He M, Shen M, Zhu J, Yang Y,

Wang M, Hu J, Ye H, Li Y, et al: Expression of somatostatin

receptor 2 in somatotropinoma correlated with the short-term

efficacy of somatostatin analogues. Int J Endocrinol.

2017(9606985)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Debnath D and Cheriyath P: Octreotide. In:

StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL,

2023.

|

|

123

|

Roelfsema F, Biermasz NR, Pereira AM and

Romijn JA: Therapeutic options in the management of acromegaly:

Focus on lanreotide Autogel. Biologics. 2:463–479. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Velija-Asimi Z: The efficacy of octreotide

LAR in acromegalic patients as primary or secondary therapy. Ther

Adv Endocrinol Metab. 3:3–9. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Giustina A, Mazziotti G, Torri V, Spinello

M, Floriani I and Melmed S: Meta-analysis on the effects of

octreotide on tumor mass in acromegaly. PLoS One.

7(e36411)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Ferrante E, Pellegrini C, Bondioni S,

Peverelli E, Locatelli M, Gelmini P, Luciani P, Peri A, Mantovani

G, Bosari S, et al: Octreotide promotes apoptosis in human

somatotroph tumor cells by activating somatostatin receptor type 2.

Endocr Relat Cancer. 13:955–962. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

127

|

Fakir S and Barabutis N: Involvement of

ATF6 in octreotide-induced endothelial barrier enhancement.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17(1604)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

128

|

Fakir S, Sigdel M, Sarker MMR, Folahan JT

and Barabutis N: Ceapin-A7 suppresses the protective effects of

Octreotide in human and bovine lung endothelial cells. Cell Stress

Chaperones. 30:1–8. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

129

|

Zeng Z, Liao Q, Gan S, Li X, Xiong T, Xu

L, Li D, Jiang Y, Chen J, Ye R, et al: Structural insights into the

binding modes of lanreotide and pasireotide with somatostatin

receptor 1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 15:2468–2479. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Li ZQ, Quan Z, Tian HL and Cheng M:

Preoperative lanreotide treatment improves outcome in patients with

acromegaly resulting from invasive pituitary macroadenoma. J Int

Med Res. 40:517–524. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

131

|

Caron PJ, Bevan JS, Petersenn S, Houchard

A, Sert C and Webb SM: PRIMARYS Investigators Group. Effects of

lanreotide Autogel primary therapy on symptoms and quality-of-life

in acromegaly: data from the PRIMARYS study. Pituitary. 19:149–157.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

132

|

Carmichael JD: Lanreotide depot deep

subcutaneous injection: A new method of delivery and its associated

benefits. Patient Prefer Adherence. 6:73–82. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Gross CM, Kellner M, Wang T, Lu Q, Sun X,

Zemskov EA, Noonepalle S, Kangath A, Kumar S, Gonzalez-Garay M, et

al: LPS-induced Acute Lung Injury Involves NF-ĸB-mediated

Downregulation of SOX18. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 58:614–624.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

134

|

Sarker MMR, Fakir S, Kubra KT, Sigdel M,

Siejka A, Stepien H and Barabutis N: Lanreotide protects against

LPS-induced inflammation in endothelial cells and mouse lungs.

Tissue Barriers: Apr 17, 2025 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

135

|

Bolanowski M, Kałużny M, Witek P and

Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska A: Pasireotide-a novel somatostatin

receptor ligand after 20 years of use. Rev Endocr Metab Disord.

23:601–620. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

136

|

Zatelli MC, Piccin D, Vignali C, Tagliati

F, Ambrosio MR, Bondanelli M, Cimino V, Bianchi A, Schmid HA,

Scanarini M, et al: Pasireotide, a multiple somatostatin receptor

subtypes ligand, reduces cell viability in non-functioning

pituitary adenomas by inhibiting vascular endothelial growth factor

secretion. Endocr Relat Cancer. 14:91–102. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

137

|

Olarescu NC, Jørgensen AP, Atai S,

Wiedmann MKH, Dahlberg D, Bollerslev J and Heck A: Pasireotide as

first line medical therapy for selected patients with acromegaly.

Pituitary. 28(48)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Cuevas-Ramos D and Fleseriu M:

Pasireotide: A novel treatment for patients with acromegaly. Drug

Des Devel Ther. 10:227–239. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

139

|

Witek P, Bolanowski M, Krętowski A and

Głowińska A: Pasireotide-induced hyperglycemia in Cushing's disease

and Acromegaly: A clinical perspective and algorithms proposal.

Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 15(1455465)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

140

|

Chinezu L, Gliga MC, Borz MB, Gliga C and

Pascanu IM: Clinical implications of molecular and genetic

biomarkers in Cushing's disease: A literature review. J Clin Med.

14(3000)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

141

|

Fakir S, Sarker MMR, Sigdel M and

Barabutis N: Protective effects of pasireotide in LPS-induced acute

lung injury. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 18(942)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

142

|

Johnsson M, Pedroncelli AM, Hansson A and

Tiberg F: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a pasireotide

subcutaneous depot (CAM4071) and comparison with immediate and

long-acting release pasireotide. Endocrine. 84:1125–1134.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

143

|

Gomes-Porras M, Cárdenas-Salas J and

Álvarez-Escolá C: Somatostatin analogs in clinical practice: A

review. Int J Mol Sci. 21(1682)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

144

|

Aversa LS, Cuboni D, Grottoli S, Ghigo E

and Gasco V: A 2024 update on growth hormone deficiency syndrome in

adults: From guidelines to real life. J Clin Med.

13(6079)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|