1. Introduction

Non-invasive fluid biopsies in in vitro

fertilization (IVF) aim to address several critical clinical gaps

that limit the efficacy and safety of current reproductive

diagnostic methods (1,2). Traditional invasive techniques, such as

embryo biopsy for genetic testing, carry risks of damaging embryos

and causing patient discomfort, and are typically limited to

single-time sampling, which restricts the ability to monitor

dynamic changes throughout assisted reproductive technology (ART)

cycles (3,4). These methods also rely heavily on

subjective morphological assessments for embryo selection, which

may not accurately predict embryo viability or genetic competence

(5,6). Additionally, invasive genetic testing

can be affected by maternal DNA contamination and require

specialized laboratory resources, rendering it less accessible and

potentially less reliable (7,8). There

is also a lack of standardized protocols, leading to variability in

results (9,10), and valuable biological materials such

as granulosa and cumulus cells are often discarded, despite

containing crucial molecular information (11). By enabling the repeated, low-risk

sampling of accessible body fluids and providing objective

molecular biomarkers, non-invasive fluid biopsies provide a

promising solution to improve embryo selection, enhance genetic

testing accuracy, and support more personalized and sustainable

reproductive therapies in IVF (10).

Current invasive methods in IVF, such as embryo

biopsy for preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), present a number

of limitations and risks (12).

These procedures can potentially harm the embryo, reduce its

viability and lead to lower implantation and pregnancy rates

(13). Additionally, invasive

sampling is uncomfortable for patients and is typically restricted

to a single time point, which limits the ability to monitor dynamic

changes throughout the ART cycle. The reliance on subjective

morphological assessments for embryo selection further compounds

the issue, as these visual evaluations may not accurately reflect

the embryo's genetic competence or developmental potential

(14). Invasive genetic testing also

faces challenges, such as maternal DNA contamination and the need

for specialized laboratory resources, rendering it less accessible

and at times, less reliable (7).

Non-invasive fluid biopsy alternatives, by contrast, enable the

repeated, low-risk sampling of accessible body fluids, such as

follicular fluid, embryo culture media and uterine secretions

(9,15). These approaches provide objective

molecular biomarkers, such as cell-free nucleic acids,

extracellular vesicles and microRNAs (miRNAs/miRs), that can more

accurately predict embryo quality and viability (10,16). By

minimizing harm to embryos and patients, and providing more

reliable, accessible and dynamic diagnostic information,

non-invasive fluid biopsies have the potential to overcome the

major limitations of current invasive methods and revolutionize

fertility diagnostics and therapeutic decision-making in IVF

(17,18).

The present review summarizes recent findings on key

biomolecular components found in accessible body fluids, such as

follicular fluid, embryo culture medium, uterine secretions and

saliva, namely cell-free nucleic acids, extracellular vesicles and

miRNAs.

2. About non-invasive fluid biopsy samples

and related molecules

Non-invasive fluid biopsies play a crucial role in

medical diagnosis and monitoring, providing advantages, such as the

ease of collection, reduced patient discomfort and the potential

for repeated sampling. Various body fluids, including urine,

saliva, interstitial fluid and nasal secretions, have been explored

for their biomarker content to aid in the non-invasive detection of

various diseases (19-21).

These biomarkers include circulating tumor cells and trophoblastic

cells, as well as more numerous, cell-free nucleic acids (cfNAs)

such cell-free DNA (cfDNA), cell-free RNA (cfRNA) and circulating

miRNAs. Furthermore, cfNAs not only circulate in isolation, but can

also associate with protective protein complexes or be encapsulated

in extracellular vesicles (EVs) (22).

cfNAs, including cfDNA and cfRNA originate from

cultured cells, non-malignant somatic tissues, tumors, embryos, or

fetuses and are released when cells undergo necrosis or apoptosis

(23). cfNAs can be characterized by

their length, physical size, surface molecules, electrical charge

and density. cfDNA can also be detected in the blastocellular fluid

of human embryos and the IVF culture medium used, allowing minimal

and non-invasive genetic testing, respectively (24). In fact, the presence of mitochondrial

DNA (mtDNA) in the culture medium of the embryo has been associated

with embryo lysis caused by apoptosis or necrosis. Stigliani et

al (25) found a strong

association between mtDNA levels in the culture medium and human

embryo fragmentation, which suggests that higher mtDNA

concentrations indicate cellular distress and apoptosis in embryos.

Furthermore, another study highlighted that the amount of DNA

present in the culture medium is negatively associated with the

competence of human embryos and clinical pregnancy outcomes,

implying that the release of mtDNA may reflect the underlying

embryonic competence (26).

3. Extracellular vesicles and their usage as

non-invasive fluid samples

EVs are crucial mediators of intercellular

communication, facilitating the exchange of biological signals

among both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. These vesicles, which

include exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies, vary in

composition and size, ranging from 30 to 1,000 nm, and contain a

variety of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids (27). These vesicles function as carriers of

biomarkers and play essential roles in tissue regeneration,

rendering them potential targets for therapeutic interventions in

various diseases (28).

The implantation of the embryo is a critical step

for a successful pregnancy and requires a complex interaction

between the embryo and the endometrium. In a previous study

investigating the involvement of EVs in embryo implantation and

endometrial diseases, EVs were isolated from uterine fluid,

cultured endometrial, epithelial/stromal and trophectodermal cells

(2s). Endometrial, epithelial and stromal/decidual cell-derived EVs

are covered by trophoblast cells, which regulate several gene

sequences involved in adhesion, invasion and migration. Conversely,

embryo-derived EVs are internalized by epithelial and immune cells

of the endometrium for the biosensing and immunomodulation required

for successful implantation. EVs have also been shown to play a

role in infertility, recurrent implantation failure, endometriosis,

endometritis and endometrial cancer (29). Further research will pave the way for

the use of EVs as non-invasive ‘liquid biopsy’ tools for assessing

endometrial health.

Ng et al (30)

analyzed a panel of 227 endometrial exosomal miRNAs and

demonstrated that a number of their target genes regulate key

pathways involved in implantation. Exosomal miRNAs not only

regulate key pathways, such as the VEGF pathway, Toll-like receptor

pathway and Jak-STAT pathway, but also adhere to extracellular

matrix-receptor interactions and junctions. Vilella et al

(31) demonstrated that hsa-miR-30d

derived from the endometrial exosome, when taken up by

trophoblasts, increased the gene expression of integrin subunit

alpha 7, integrin subunit beta-3 and cadherin 5 required for

blastocyst implantation. Greening et al (32) further demonstrated that endometrial

EVs increased their adhesiveness through the focal adhesion kinase

signaling pathway when internalized by the trophectoderm.

4. Non-invasive fluid samples and

preimplantation genetic testing

The use of PGT has expanded significantly in recent

years, driven by advances made in genetic testing technologies and

an increased understanding of genetic disorders. Major reproductive

societies endorse PGT for various indications, including aneuploidy

screening, HLA matching and the prevention of genetic diseases

(33). The most common indication

for PGT remains aneuploidy screening, particularly for couples with

an advanced maternal age or those experiencing recurrent

implantation failure (34). Despite

its benefits, traditional PGT methods continue to face challenges,

including the potential for damage to embryos and the need for

specialized laboratory resources (1). While non-invasive PGT provides the

potential to reduce embryo harm and patient risk, its current

limitations, particularly maternal contamination, a low cfDNA

yield, diagnostic variability, the lack of standardization and

biological uncertainties, need to be critically addressed through

further research and protocol optimization before it can reliably

replace invasive methods in clinical IVF practice (2-4,35).

Kuznyetsov et al (7) demonstrated that combining spent embryo

culture media and blastocoel fluid enhanced the quantity and

quality of cfDNA available for aneuploidy testing, potentially

improving the accuracy of genetic assessments. This approach

minimizes the risks associated with invasive biopsies, while still

providing valuable genetic information.

Moreover, Brouillet et al (8) conducted a systematic review, indicating

that cfDNA in spent embryo culture medium could serve as a viable

alternative to embryo biopsy for PGT, highlighting its potential to

streamline the testing process and reduce costs. The analysis of

EVs and miRNAs in non-invasive samples has also shown that they

hold promise as additional biomarkers for embryo health and

viability (36).

The integration of non-invasive testing could lead

to higher implantation rates, reduced miscarriage rates and

improved overall outcomes for couples undergoing IVF. Furthermore,

advancements in next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics are

expected to enhance the accuracy and reliability of non-invasive

genetic testing methods, rendering them more accessible to a

broader range of patients (33).

Follicular fluid

Embryo selection procedures in IVF aim to identify

high-quality embryos with the highest implantation potential. cfDNA

of apoptotic granulosa cells is present in follicular fluid, which

influences follicle maturation and oocyte growth in vivo.

This biomarker can be used to sample the developmental competence

of the contained oocyte during the oocyte retrieval phase of IVF

treatment. Low levels of cfDNA in follicular fluid are

significantly associated with a low embryo fragmentation rate and

are indicative of high-quality embryos (37). Furthermore, extracellular mtDNA is

actively released by granulosa cells into the follicular fluid in

response to mitotic failure, and a low mtDNA content is associated

with high oocyte developmental ability, and this allows for the

determination of the viability of the embryo (38).

Cumulus-oocyte complex (COC) and

granulosa cells

The COC is involved in several key processes,

including oocyte growth, metabolic regulation and cellular adhesion

to the oocyte membrane. It also facilitates intercellular

communication between the cumulus cells and the oocyte, which is

essential for oocyte maturation and successful fertilization.

Additionally, the COC is necessary for the expansion of the cumulus

oophorous and plays a role in the spatial distribution of granulosa

cells within the follicle (39). The

complex also regulates gap junctions and cytoskeletal changes and

influences polar body displacement after treatments to remove

cumulus-corona cells in preparation for assisted reproductive

methods (40). The COC is a dynamic

structure that undergoes changes during in vitro culture,

influenced by various factors, such as biological (e.g.,

age-related) and external (e.g., co-enzyme Q10 supplementation)

conditions (41).

In cases of mitochondrial malfunction, it has been

shown that cumulus cells surrounding the oocyte during development

can increase the levels of cf-mtDNA in IVF culture media (42). Researchers are investigating the

effects of mitochondrial dysfunction to predict the developmental

competence and implantation potential of embryos, as well as to

better understand embryo quality (43-45).

Since the expression of specific genes in cumulus cells is linked

to embryo potential and pregnancy outcomes, cumulus cell gene

expression is a reliable indicator of oocyte quality (24).

Granulosa cells are involved in various

ovary-related diseases, including polycystic ovary syndrome

(46). The interaction between

granulosa cells and theca cells is crucial for early progesterone

synthesis (47). Granulosa cells

express specific biomarkers and receptors, such as aromatase and

thyroid hormone receptors, highlighting their functional importance

(48). Despite their physiological

importance, granulosa cells and associated structures, such as the

corona cumulus, are often discarded as waste during IVF treatments.

However, their potential alternative applications or effects as

waste have not been extensively investigated. Culture media

enriched with various components used in IVF treatments support the

growth and maturation of these cells and the oocyte (49). Further research into the potential

use or analysis of these excreted components could enhance the

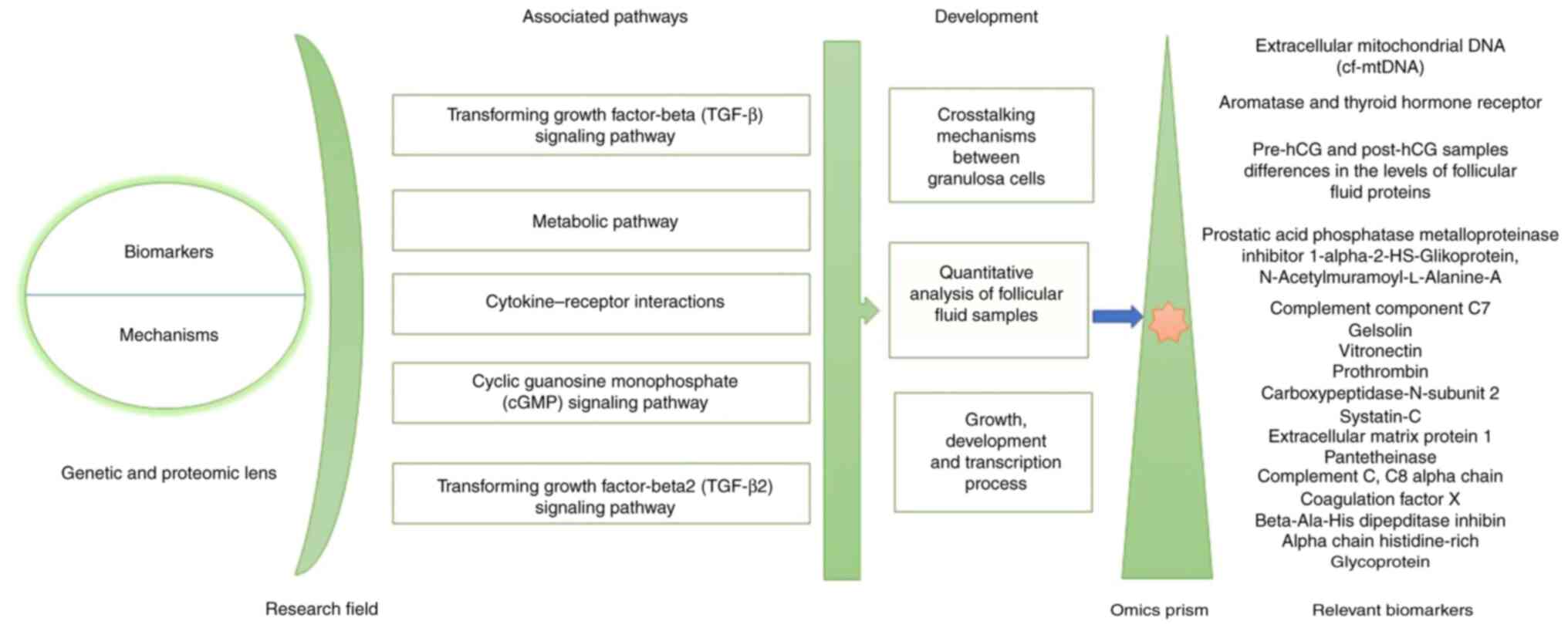

understanding of reproductive biology. A summary of genetic,

epigenetic and proteomic influences on granulosa cells in

follicular fluid and their associated pathways according to

developmental mechanisms and transcription process with relevant

biomarkers is provided below and is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Genetic research on granulosa cells in

follicular fluid

The transcription information from granulosa cells,

which are the somatic cells most adjacent to the oocyte, may mirror

the developmental competence of the associated oocyte. Therefore,

comparing the follicular fluid microenvironment and granulosa cell

gene expression, particularly in patients with a poor ovarian

response treated with various ovarian stimulation methods is

critical for understanding the effects of different treatments on

follicular physiology (5).

At present, exogenous gonadotropin (Gn) is used as a

required drug for ovarian stimulation in ART by affecting the way

granulosa cells, follicular fluid and oocytes interact, which in

turn promotes follicular growth. In the study by Liu et al

(50), the transcriptome of the

granulosa cell was analyzed to determine whether Gn stimulation may

potentially cause meiotic mistakes in human oocytes following

natural and Gn stimulation cycles.

Proteomic research on granulosa cells

in follicular fluid

To gain a better understanding of the

intrafollicular environment during oocyte maturation, Zamah et

al (51) performed a proteomic

analysis of follicular fluid from anonymous oocyte donors

undergoing IVF oocyte retrieval. As a result, a total of 742

follicular fluid proteins were identified in healthy ovum donors,

which included 413 previously unnotified ones. These mentioned

proteins belong to various functional groups, such as insulin

growth factors and its binding protein families, immunity, growth

factors, anti-apoptotic proteins, receptor signaling and matrix

metalloprotease-associated proteins. Moreover, a quantitative

analysis of follicular fluid samples among the women with matched

ages and between the pre-hCG and post-hCG samples indicated the

vital differences in the levels of 17 follicular fluid proteins,

which play a role in inflammation, cell adhesion and protease

inhibition processes (Fig. 1)

(51).

The study by Al-Saleh et al (52) examined the differences in hormone and

cytokine levels between the follicular fluids of the mild ovarian

stimulation and conventional groups. As a result, the follicle

stimulating hormone, prolactin and progesterone levels in the

follicular fluid were significantly lower in the mild ovarian

stimulation group compared to the conventional one (52). Furthermore, the cytokine

concentrations in the mild group were significantly higher in

TGF-β2 and lower in growth differentiation factor-9 (GDF-9), while

the bone morphogenic protein-15 (BMP-15) levels were comparable

(Fig. 1) (33).

Oxidative stress research on granulosa

cells in follicular fluid

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide

anion, hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide, are produced during

mitochondrial electron transport for energy production, and are

essential for controlling follicular growth, oocyte maturation,

ovulation, fertilization, embryo implantation and fetal development

(53). A surge in luteinizing

hormone and neovascularization within the follicle during ovulation

provides essential stimulation for follicular rupture and oocyte

maturation, which in response stimulates the production of ROS

(54).

When there is an imbalance between oxidation and the

antioxidant system, ROS can oxidatively damage DNA, proteins and

lipids either directly or indirectly and it can lead to gene

mutations, protein denaturation and lipid peroxidation (55). Al-Saleh et al (52) indicated that oxidative stress

biomarkers, including 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine, total antioxidant

capacity and malondialdehyde may be useful tools for assessing

clinical features in patients undergoing IVF due to their

association with reproductive hormones and pregnancy outcomes in

ART. As aforementioned, follicular development and oocyte

maturation are strongly influenced by the interaction between the

oxidative, antioxidative system and metabolic products within a

follicular fluid. Furthermore, this fluid is appropriate for

determining the levels of oxidative stress in the follicular milieu

and, as a result, the developmental potential of oocytes as it is

simple and non-invasive to acquire (56). The complex role of oxidative stress,

which may have undetermined advantageous functions in some

circumstances, may help to elucidate the mechanisms through which

oxidative stress can improve oocyte quality and result in normal

fertility if the level of ROS in the cell is at an appropriate

level (57).

6. Research on the cumulus-oocyte complex in

follicular fluid

Genetic research on the COC in

follicular fluid

Cumulus cells (CCs) from follicles with varying

diameters exhibit variations in gene expression related to

metabolic processes, cell differentiation, and adhesion, according

to one study's genetic ontology analysis. Additionally, research

has discovered genetic biomarkers expressed in CCs that can predict

the developmental competence of oocytes and provide a non-invasive

manner to evaluate the quality of oocytes (58). Gene expression in CCs has been linked

to embryonic development and pregnancy, suggesting a fundamental

role of cumulus cell pathways (PAP1, RAS and ErbB pathways) in

these processes (59).

In the study conducted by Su et al (60), oocytes were shown to regulate

metabolic activities in CCs by upregulating the expression of

certain genes that encode amino acid transporters and enzymes

essential for oocyte-deficient metabolic processes. CC-associated

genes, such as hyaluronan synthase homolog,

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2) and TNF-stimulated

gene 6 (Tnfsg6) have been shown to be abundant in CCs, which has

implications for cumulus growth and subsequent embryonic

development (61). Ligand-encoding

genes with specific expression in oocytes or CC have been linked to

biological functions, possibly linked to the coordinated formation

of transzonal projections from CC that reach the oocyte membrane

(62). The expression of

expansion-associated genes, such as Ptgs2 or cyclooxygenase-2,

TNF-alpha-induced protein 6 (Tnfaip6) and hyaluronan synthase 2

(Has2) in CCs is essential for the synthesis and stabilization of

the extracellular matrix by CCs, and is crucial for cumulus

expansion and ovulation (Tables I

and II) (61). Furthermore, the downregulation of the

Wnt signaling pathway in dysmature CCs was identified as a marker

for assessing oocyte quality, demonstrating the importance of gene

expression in CC as an indicator of embryonic development (Tables I and II) (63).

| Table IOverview of key non-invasive

biomarkers relevant to IVF, listing their biological sources and

summarizing their clinical implications. |

Table I

Overview of key non-invasive

biomarkers relevant to IVF, listing their biological sources and

summarizing their clinical implications.

| Biomarker | Source | Clinical

implications |

|---|

| Cell-free DNA

(cfDNA) | Follicular fluid,

embryo culture media | Indicates oocyte

and embryo quality, apoptosis, and developmental competence;

non-invasive genetic testing; lower levels linked to higher

pregnancy rates. |

| Cell-free

mitochondrial DNA (cf-mtDNA) | Follicular fluid,

embryo culture media | Associated with

cellular distress, apoptosis, and embryo fragmentation; lower

levels linked to higher embryo viability. |

| Extracellular

vesicles (EVs) | Uterine fluid,

embryo culture media, endometrial secretions | Mediate

intercellular communication; contain proteins, lipids, and nucleic

acids; biomarkers for implantation, endometrial health, and embryo

viability. |

| MicroRNAs (miRNAs,

sncRNAs) | Follicular fluid,

embryo culture media, endometrial exosomes | Regulate gene

expression related to implantation and embryo development;

non-invasive markers for embryo health and implantation

potential. |

| Proteins (PTX3,

TNFAIP6, BMP15, GDF9, MMPs, VEGF, FSH, LH, hCG) | Follicular fluid,

cumulus cells, embryo culture media | Involved in cumulus

expansion, oocyte maturation, embryo development, and ovarian

response; markers for oocyte and embryo quality. |

| Oxidative stress

markers (MDA, 8-OHdG, AOPP, TAC, SOD, GPx, GST, thiol groups) | Follicular fluid,

cumulus cells | Reflect oxidative

stress status; associated with reproductive hormones, embryo

quality, and IVF outcomes. |

| Metabolites

(glucose, lactate, glycerophosphocholine, androsterone sulfate,

elaidic carnitine) | Follicular fluid,

embryo culture media | Indicate metabolic

activity, ovarian response, and predict clinical outcomes

(pregnancy, miscarriage, live birth rates). |

| Gene expression

profiles | Granulosa cells,

cumulus cells, uterine fluid | Predict oocyte and

embryo quality, endometrial receptivity, and pregnancy outcomes;

used for personalized embryo selection. |

| Immunologic

markers | Follicular fluid,

blood, endometrial tissue | Indicate immune

status, inflammation, and endometrial receptivity; potential

predictors of implantation success. |

| Antioxidant enzymes

(glutathione peroxidase, catalase, SOD) | Follicular fluid,

cumulus cells | High levels are

linked to better oocyte and embryo quality; protect against

oxidative damage. |

| Time-lapse

Imaging/morphokinetic parameters | Embryo culture

media (image analysis) | Non-invasive

assessment of embryo developmental kinetics and morphology;

associated with live birth rates. |

| Transcriptomic

biomarkers | Uterine fluid,

endometrial secretions | Predict endometrial

receptivity and window of implantation; guide timing of embryo

transfer. |

| Seminal plasma

biomarkers (cfDNA, proteins, metabolites) | Semen | Non-invasive

assessment of male fertility, sperm retrieval potential, and ART

outcomes. |

| Table IICumulus-oocyte complex in genetics,

proteomics and oxidative stress research. |

Table II

Cumulus-oocyte complex in genetics,

proteomics and oxidative stress research.

| A, Genetic research

on the COC in follicular fluid |

|---|

| Key genes | Functional

roles | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Hyaluronan synthase

homolog prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, TNF-stimulated gene

6 (Hsh, Ptgs2 and Tnfsg6) | Genes affecting

cumulus growth and subsequent embryonic development | (61,63) |

| Prostaglandin

synthase-2 or cyclooxygenase-2, tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced

protein and hyaluronan synthase 2 (Ptgs2, Tnfaip6 and Has2) | Cumulus expansion

and ovulation | (61) |

| Hyaluronan synthase

2, prostaglandin synthase-2 or cyclooxygenase-2, and gremlin1

(Has2, Ptgs2 and Grem1) | Oocyte and embryo

quality | (6) |

| B, Proteomic

research on the COC in follicular fluid |

| Structural

proteins | Roles in the

cumulus matrix | (Refs.) |

| Pentraxin 3, tumor

necrosis factor-induced protein 6, bone morphogenetic protein 15

and growth differentiation factor 9 (Ptx3, Tnfip6, Bmp15 and

Gdf9) | Organization and

function of the cumulus matrix | (65) |

| PTX3 and

TNFIP6 | Key components of

the cumulus matrix required for cumulus expansion and in

vivo fertilization | (65) |

| Inter-Α-trypsin

inhibitor (Iαi or ITI), tumor necrosis factor-induced protein-6

(TSG6 Or TNFIP6) and pentraxin 3 (PTX3 Or TSG14) | Proteins required

for the formation and stability of the COC matrix | (66) |

| Protein levels of

phospho-H2AX, breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1),

ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM), meiotic recombination 11

homolog A (MRE11) and radiation repair gene (RAD51) | Significantly

increased in aging CCs, suggesting that these proteins are involved

in the aging process | (67) |

| C, Oxidative stress

research on the COC in follicular fluid |

| Oxidative stress

biomarkers | Impact for oocyte

development | (Refs.) |

| Malondialdehyde

(MDA), 8-Oxo-2'-Deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), Advanced Oxidation Protein

Products (AOPP), Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC), Superoxide

Dismutase (SOD), Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx), Glutathione

S-transferase (GST), Thiol Groups | Fragmented DNA,

poorer embryological development, and increased miscarriage

rates | (69) |

The expression of certain genes in CCs has been

identified as potential markers for oocyte and subsequent embryo

quality. The study by Uyar et al (6) demonstrated that the expression levels

of genes in CCs are related to oocyte maturation, fertilization and

embryo quality. In particular, the expression of Has2, Ptgs2 or

cyclooxygenase-2 and gremlin1 in CCs was shown to be associated

with oocyte and embryo quality (Tables

I and II) (6). Akino et al (63) used next-generation sequencing to

analyze gene expression in immature CCs, revealing the

downregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway as a marker for

determining oocyte quality. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated

that the expression of certain genes in CCs is associated with

embryonic developmental competence, suggesting their potential as

markers for oocyte quality (Tables I

and II) (64).

Proteomic research on the COC in

follicular fluid

Several proteins essential for the organization and

function of the cumulus matrix have been identified, including

pentraxin 3 (PTX3), TNF-induced protein 6 (TNFAIP6), BMP15 and

GDF9. Following the pre-ovulatory luteinizing hormone, these

proteins play a role in cumulus expansion, oocyte-cumulus cell

contact and cumulus cell function control (65). Furthermore, proteins secreted by CCs

have been shown to form ligand-receptor pairs that transmit

paracrine signaling between the oocyte and CCs, demonstrating the

complex communication and regulatory networks between these two

components (62). PTX3 and TNFIP6

were identified as key components of the cumulus matrix required

for cumulus expansion and IVF (Tables

I and II) (65). Inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, TNFAIP6 and

PTX3 were identified as proteins required for the formation and

stability of the COC matrix (Tables

I and II) (66). Protein levels of phospho-H2AX, breast

cancer susceptibility gene 1, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated,

meiotic recombination 11 homolog A and radiation repair gene were

previously significantly increased in aging CCs, suggesting that

these proteins are involved in the aging process (Tables I and II) (67).

Oxidative stress research on the COC

in follicular fluid

The presence of CCs during IVF has been shown to

protect the oocyte against oxidative stress, thus improving initial

division and subsequent development. The exposure of oocytes to

hydrogen peroxide has been shown to result in oocyte death and the

blockade of the first division, highlighting the protective role of

CCs against oxidative stress during fertilization (68). Moreover, oxidative stress has been

associated with fragmented DNA, poorer embryological development

and increased miscarriage rates (Table

I and II) (69).

7. Conclusion and future perspectives

The advent of non-invasive fluid biopsies has

transformed the landscape of medical diagnostics and reproductive

health, providing a more patient-friendly alternative to

traditional biopsy methods. By leveraging biomarkers, such as EVs,

circulating tumor cells and cfNAs, researchers have expanded the

potential for early disease detection, prognostic evaluation, and

personalized therapeutic strategies. These innovations have been

particularly impactful in oncology, where liquid biopsies offer a

means to detect tumor-derived genetic material and monitor

treatment responses in real time. Additionally, in reproductive

medicine, the ability to analyze cfDNA and cfRNA from embryo

culture media has opened new avenues for non-invasive PGT, reducing

the need for embryo biopsies and mitigating potential risks to

embryo viability.

Despite these advancements, several challenges

remain to be addressed before non-invasive fluid biopsies can

become routine in clinical practice. The sensitivity and

specificity of these methods vary across different conditions,

necessitating the further refinement of isolation and detection

techniques. Standardization remains a critical issue, as

differences in sample collection, processing and analytical

methodologies can lead to inconsistent results. Moreover, the low

concentration of biomarkers in some fluids, such as ctDNA in

early-stage cancer, poses a significant limitation, requiring

improvements in enrichment and amplification technologies to

enhance detection accuracy.

In reproductive health, while non-invasive methods

such as the analysis of cfDNA in embryo culture media shows

promise, their clinical utility remains under debate. The presence

of maternal contamination, the accuracy of chromosomal assessments

and the reproducibility of findings across different patient

populations warrant further investigation. Additionally, the

clinical application of EVs as biomarkers in fertility and

pregnancy-related complications is an emerging field that requires

extensive validation through large-scale studies.

Looking ahead, future research is required to focus

on integrating multi-omics approaches, combining genomics,

transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, to develop more

comprehensive and reliable diagnostic tools.

In conclusion, non-invasive fluid biopsies hold

immense potential to revolutionize disease diagnosis, treatment

monitoring and reproductive medicine. While significant progress

has been made, continued advancements in technology,

standardization and clinical validation are essential for these

approaches to become fully integrated into mainstream medical

practice. With ongoing innovation, non-invasive sampling techniques

could ultimately lead to a paradigm shift in personalized medicine,

offering safer, more efficient and widely applicable diagnostic

solutions for a range of medical conditions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ÇÖ conceived the study. SAÖ, NÖK, DK and ÇÖ

performed the literature review and the analysis of data from the

literature. The manuscript was drafted by SAÖ, NÖK, DK and ÇÖ and

was critically reviewed by all authors. All authors have read and

agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Yang S, Xu B, Zhuang Y, Zhang Q, Li J and

Fu X: Current research status and clinical applications of

noninvasive preimplantation genetic testing: A review. Medicine.

10(e39964)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Volovsky M, Scott RT Jr and Seli E:

Non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: Is the

promise real? Hum Reprod. 39:1899–1908. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tsai NC, Chang YC, Su YR, Lin YC, Weng PL,

Cheng YH, Li YL and Lan KC: Validation of non-invasive

preimplantation genetic screening using a routine IVF laboratory

workflow. Biomedicines. 10(1386)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Chow JFC, Lam KKW, Cheng HHY, Lai SF,

Yeung WSB and Ng EHY: Optimizing non-invasive preimplantation

genetic testing: Investigating culture conditions, sample

collection, and IVF treatment for improved non-invasive PGT-A

results. J Assist Reprod Genet. 41:465–472. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Adriaenssens T, Wathlet S, Segers I,

Verheyen G, De Vos A, Van Der Elst J, Coucke W, Devroey P and Smitz

J: Cumulus cell gene expression is associated with oocyte

developmental quality and influenced by patient and treatment

characteristics. Hum Reprod. 25:1259–1270. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Uyar A, Torrealday S and Seli E: Cumulus

and granulosa cell markers of oocyte and embryo quality. Fertile

Steril. 99:979–997. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kuznyetsov V, Madjunkova S, Abramov R,

Antes R, Ibarrientos Z, Motamedi G, Zaman A, Kuznyetsova I and

Librach CL: Minimally invasive cell-free human embryo aneuploidy

testing (miPGT-A) utilizing combined spent embryo culture medium

and blastocoel fluid-towards development of a clinical essay. Sci

Rep. 10(7244)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Brouillet S, Martinez G, Coutton C and

Hamamah S: Is cell-free DNA in spent embryo culture medium an

alternative to embryo biopsy for preimplantation genetic testing? A

systematic review. Reprod Biomed Online. 40:779–796.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Alizadegan A, Dianat-Moghadam H, Shadman

N, Nouri M, Hamdi K, Ghasemzadeh A, Akbarzadeh M, Sarvarian P,

Mehdizadeh A, Dolati S and Yousefi M: Application of cell free DNA

in ART. Placenta. 24:18–24. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Abreu C, Thomas V, Knaggs P, Bunkheila A,

Cruz A, Teixeira SR, Alpuim P, Francis LW, Gebril A, Ibrahim A, et

al: Non-invasive molecular assessment of human embryo development

and implantation potential. Biosens Bioelectron.

157(112144)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Massoud G, Spann M, Vaught KC, Das S, Dow

M, Cochran R, Baker V, Segars J and Singh B: Biomarkers assessing

the role of cumulus cells on IVF outcomes: A systematic review. J

Assist Reprod Genet. 41:253–275. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Aoyama N and Kato M: Trophectoderm biopsy

for preimplantation genetic test and technical tips: A review.

Reprod Med Biol. 19:222–231. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Scott Jr RS, Upham K, Forman E, Zhao T and

Treff NR: Cleavage-stage biopsy significantly impairs human

embryonic implantation potential while blastocyst biopsy does not:

A randomized and paired clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 100:624–630.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yang H, DeWan AT, Desai MM and Vermund SH:

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: Challenges in

clinical practice. Hum Genomics. 16(69)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bellassai N, Biricik A, Surdo M, Bianchi

V, D'Agata R, Breveglieri G, Gambari R, Spinella F and Spoto G:

Non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing: Cell-free DNA

detection in embryo culture media using a plasmonic biosensor. Anal

Chem. 97:19241–19248. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Battaglia R, Caponnetto A, Ferrara C,

Fazzio A, Barbagallo C, Stella M, Barbagallo D, Ragusa M, Vento ME,

Borzì P, et al: Up-regulated microRNAs in blastocoel fluid of human

implanted embryos could control circuits of pluripotency and be

related to embryo competence. J Assist Reprod Genet. 42:1635–1649.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Xing X, Wu S, Xu H, Ma Y, Bao N, Gao M,

Han X, Gao S, Zhang S, Zhao X, et al: Non-invasive prediction of

human embryonic ploidy using artificial intelligence: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine.

24(102897)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ersoy Z, Ozdemirkan ZA, Zeyneloglu P,

Cekmen N, Torgay A, Kayhan Z and Haberal M: Pulse contour cardiac

output system monitoring in pediatric patients undergoing

orthotopic liver transplantation. Int J Innov Res Med Sci.

7(11)2022.

|

|

19

|

Njoku K, Chiasserini D, Jones ER, Barr CE,

O'Flynn H, Whetton AD and Crosbie EJ: Urinary biomarkers and their

potential for the non-invasive detection of endometrial cancer.

Front Oncol. 10(559016)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Tran BQ, Miller PR, Taylor RM, Boyd G,

Mach PM, Rosenzweig CN, Baca JT, Polsky R and Glaros T: Proteomic

characterization of dermal interstitial fluid extracted using a

novel microneedle-assisted technique. J Proteome Res. 17:479–485.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Woźniak M, Paluszkiewicz C and Kwiatek WM:

Saliva as a non-invasive material for early diagnosis. Acta Biochim

Pol. 66:383–388. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zeng H, He B, Yi C and Peng J: Liquid

biopsies: DNA methylation analyses in circulating cell-free DNA. J

Genet Genomics. 45:185–192. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DSB and Pantel K:

Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev

Cancer. 11:426–437. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Assou S, Aït-Ahmed O, El Messaoudi S,

Thierry AR and Hamamah S: Non-invasive pre-implantation genetic

diagnosis of X-linked disorders. Med Hypotheses. 83:506–508.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Stigliani S, Anserini P, Venturini PL and

Scaruffi P: Mitochondrial DNA content in embryo culture medium is

significantly associated with human embryo fragmentation. Hum

Reprod. 28:2652–2660. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Caamaño D, Cabezas J, Aguilera C, Martinez

I, Wong YS, Sagredo DS, Ibañez B, Rodriguez S, Castro FO and

Rodriguez-Alvarez L: DNA content in embryonic extracellular

vesicles is independent of the apoptotic rate in bovine embryos

produced in vitro. Animals (Basel). 14(1041)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang WL, Liu Y, Jiang J, Tang YJ, Tang YL

and Liang XH: Extracellular vesicle long non-coding RNA-mediated

crosstalk in the tumor microenvironment: Tiny molecules, huge

roles. Cancer Sci. 111:2726–2735. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Birjandi AA and Sharpe P: Potential of

extracellular space for tissue regeneration in dentistry. Front

Physiol. 13(1034603)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Mishra A, Ashary N, Sharma R and Modi D:

Extracellular vesicles in embryo implantation and disorders of the

endometrium. Am J Reprod Immunol. 85(e13360)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ng YH, Rome S, Jalabert A, Forterre A,

Singh H, Hincks CL and Salamonsen LA: Endometrial

exosomes/microvesicles in the uterine microenvironment: A new

paradigm for embryo-endometrial cross talk at implantation. PLoS

One. 8(e0058502)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Vilella F, Moreno-Moya JM, Balaguer N,

Grasso A, Herrero M, Martínez S, Marcilla A and Simón C:

Hsa-miR-30d, secreted by the human endometrium, is taken up by the

pre-implantation embryo and might modify its transcriptome.

Development. 142:3210–3221. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Greening DW, Nguyen HPT, Elgass K, Simpson

RJ and Salamonsen LA: Human endometrial exosomes contain

hormone-specific cargo modulating trophoblast adhesive capacity:

Insights into endometrial-embryo interactions. Biol Reprod.

94(38)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Bedrick BS, Tipping AD, Nickel KB, Riley

JK, Jain T and Jungheim ES: State-mandated insurance coverage and

preimplantation genetic testing in the United States. Obstet

Gynecol. 139:500–508. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Snoek R, Stokman MF, Lichtenbelt KD, van

Tilborg TC, Simcox CE, Paulussen ADC, Dreesen JCMF, van Reekum F,

Lely AT, Knoers NVAM, et al: Preimplantation genetic testing for

monogenic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 15:1279–1286.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

de Albornoz EC, Arroyo JAD, Iriarte YF,

Vendrell X, Vidal VM and Roig MC: Non invasive preimplantation

testing for aneuploidies in assisted reproduction: A SWOT Analysis.

Reprod Sci. 32:1–14. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hawke DC, Watson AJ and Betts DH:

Extracellular vesicles, microRNA and the preimplantation embryo:

Non-invasive clues of embryo well-being. Reprod Biomed Online.

42:39–54. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Scalici E, Traver S, Molinari N, Mullet T,

Monforte M, Vintejoux E and Hamamah S: Cell-free DNA in human

follicular fluid as a biomarker of embryo quality. Hum Reprod.

29:2661–2669. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Stigliani S, Persico L, Lagazio C,

Anserini P, Venturini PL and Scaruffi P: Mitochondrial DNA in day 3

embryo culture medium is a novel, non-invasive biomarker of

blastocyst potential and implantation outcome. Mol Hum Reprod.

20:1238–1246. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Dompe C, Kulus M, Stefańska K, Kranc W,

Chermuła B, Bryl R, Pieńkowski W, Nawrocki MJ, Petitte JN, Stelmach

B, et al: Human granulosa cells-stemness properties, molecular

cross-talk and follicular angiogenesis. Cells.

10(1396)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Nakano R, Radaelli MRM, Fujihara LS,

Yoshinaga F, Nakano E and Almodin CG: Efficacy of a modified

transvaginal ultrasound-guided fresh embryo transfer procedure.

JBRA Assist Reprod. 26:78–83. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ben-Meir A, Kim K, McQuaid R, Esfandiari

N, Bentov Y, Casper RF and Jurisicova A: Co-enzyme Q10

supplementation rescues cumulus cells dysfunction in a maternal

aging model. Antioxidants (Basel). 8(58)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Kansaku K, Munakata Y, Itami N, Shirasuna

K, Kuwayama T and Iwata H: Mitochondrial dysfunction in

cumulus-oocyte complexes increases cell-free mitochondrial DNA. J

Reprod Dev. 64:261–266. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Lukaszuk K and Podolak A: Does

trophectoderm mitochondrial DNA content affect embryo developmental

and implantation potential? Int J Mol Sci. 23(5976)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Hashimoto S and Morimoto Y: Mitochondrial

function of human embryo: Decline in their quality with maternal

aging. Reprod Med Biol. 21(e12491)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Van Blerkom J: Mitochondrial function in

the human oocyte and embryo and their role in developmental

competence. Mitochondrion. 11:797–813. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Guo H, Li T and Sun X: LncRNA HOTAIRM1,

miR-433-5p and PIK3CD function as a ceRNA network to exacerbate the

development of PCOS. J Ovarian Res. 14(19)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Tajima K, Orisaka M, Yata H, Goto K,

Hosokawa K and Kotsuji F: Role of granulosa and theca cell

interactions in ovarian follicular maturation. Microsc Res Tech.

69:450–458. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Kato N, Uchigasaki S, Fukase M and Kurose

A: Expression of P450 aromatase in granulosa cell tumors and

sertoli-stromal cell tumors of the ovary: Which cells are

responsible for estrogenesis? Int J Gynecol Pathol. 35:41–47.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Sciorio R and Rinaudo R: Culture

conditions in the IVF laboratory: State of the ART and possible new

directions. J Assist Reprod Genet. 40:2591–2607. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Liu X, Mai H, Chen P, Zhang Z, Wu T, Chen

J, Sun P, Zhou C, Liang X and Huang R: Comparative analyses in

transcriptome of human granulosa cells and follicular fluid

micro-environment between poor ovarian responders with conventional

controlled. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 20(54)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Zamah AM, Hassis ME, Albertolle ME and

Williams KE: Proteomic analysis of human follicular fluid from

fertile women. Clin Proteomics. 12(5)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Al-Saleh I, Coskun S, Al-Rouqi R,

Al-Rajudi T, Eltabache C, Abduljabbar M and Al-Hassan S: Oxidative

stress and DNA damage status in couples undergoing in vitro

fertilization treatment. Reprod Fertil. 2:117–139. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Reiter RJ, Sharma R, Romero A, Manucha W,

Tan DX, de Campos Zuccari DAP and Chuffa LGA: Aging-related ovarian

failure and infertility: Melatonin to the rescue. Antioxidants

(Basel). 12(695)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Tamura H, Jozaki M, Tanabe M, Shirafuta Y,

Mihara Y, Shinagawa M, Tamura I, Maekawa R, Sato S, Taketani T, et

al: Importance of melatonin in assisted reproductive technology and

ovarian aging. Int J Mol Sci. 21(1135)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Drejza MA, Rylewicz K, Majcherek E,

Gross-Tyrkin K, Mizgier M, Plagens-Rotman K, Wójcik M,

Panecka-Mysza K, Pisarska-Krawczyk M, Kędzia W and

Jarząbek-Bielecka G: Markers of oxidative stress in obstetrics and

Gynaecology-a systematic literature review. Antioxidants (Basel).

11(1477)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Huang J, Feng Q, Zou L, Liu Y, Bao M, Xia

W and Zhu C: Humanin exerts a protective effect against

D-galactose-induced primary ovarian insufficiency in mice.

Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 48(103330)2025.

|

|

57

|

Dong L, Teh DBL, Kennedy BK and Huang Z:

Unraveling female reproductive senescence to enhance healthy

longevity. Cell Res. 33:11–29. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Wigglesworth K, Lee KB, Emori C, Sugiura K

and Eppig JJ: Transcriptomic diversification of developing cumulus

and mural granulosa cells in mouse ovarian follicles. Biol Reprod.

92(23)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Demiray SB, Goker ENT, Tavmergen E, Yilmaz

O, Calimlioglu N, Soykam HO, Oktem G and Sezerman U: Differential

gene expression analysis of human cumulus cells. Clin Exp Reprod

Med. 46:76–86. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Su YQ, Sugiura K and Eppig JJ: Mouse

oocyte control of granulosa cell development and function:

Paracrine regulation of cumulus cell metabolism. Semin Reprod Med.

27:32–42. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Hsieh M, Lee D, Panigone S, Horner K, Chen

R, Theologis A, Lee DC, Threadgill DW and Conti M: Luteinizing

hormone-dependent activation of the epidermal growth factor network

is essential for ovulation. Mol Cell Biol. 27:1914–1924.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Biase FH and Kimble KM: Functional

signaling and gene regulatory networks between the oocyte and the

surrounding cumulus cells. BMC Genomics. 19(351)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Akino R, Matsui D, Kawahara-Miki R, Amita

M, Tatsumi K, Ishida E, Kang W, Takada S, Miyado K and Sekizawea A:

Next-generation sequencing reveals downregulation of the Wnt

signaling pathway in human dysmature cumulus cells as a hallmark

for evaluating oocyte. Reprod Med. 1:205–215. 2020.

|

|

64

|

Vigone G, Merico V, Prigione A, Mulas F,

Sacchi L, Gabetta M, Bellazzi R, Redi CA, Mazzini G, Adjaye J, et

al: Transcriptome based identification of mouse cumulus cell

markers that predict the developmental competence of their enclosed

antral oocytes. BMC Genomics. 14(380)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Salustri A, Garlanda C, Hirsch E, De

Acetis M, Maccagno A, Bottazi B, Doni A, Bastone A, Mantovani G,

Peccoz PB, et al: PTX3 plays a key role in the organization of the

cumulus oophorus extracellular matrix and in in vivo fertilization.

Development. 131:1577–1586. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Scarchilli L, Camaioni A, Bottazzi B,

Negri V, Doni A, Deban L, Bastone A, Salvatori G, Mantovani A,

Siracusa G and Salustri A: PTX3 Interacts with Inter-α-trypsin

Inhibitor: IMPLICATIONS FOR HYALURONAN ORGANIZATION AND CUMULUS

OOPHORUS EXPANSION. J Biol Chem. 12(41)2007.

|

|

67

|

Sun XL, Jiang H, Han DX, Fu Y, Liu JB, Gao

Y, Hu SM, Yuan B and Zhang JB: The activated DNA double-strand

break repair pathway in cumulus cells from aging patients may be

used as a convincing predictor of poor outcomes after in vitro

fertilization-embryo transfer treatment. PLoS One.

13(e0204524)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Fatehi AN, Roelen BAJ, Colenbrander B,

Schoevers EJ, Gadella BM, Bevers MM and van den Hurk R: Presence of

cumulus cells during in vitro fertilization protects the bovine

oocyte against oxidative stress and improves first cleavage but

does not affect further. Zygote. 13:177–185. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Chua SC, Yovich SJ, Hinchliffe PM and

Yovich JL: How well do semen analysis parameters correlate with

sperm DNA fragmentation? A retrospective study from 2567 semen

samples analyzed by the. J Pers Med. 13(518)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|