At the end of 2019, a novel coronavirus disease

(COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus

2 (SARS-CoV-2) spread rapidly around the globe, causing an

unprecedented impact on the public health. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to

the genus β-coronavirus, a single-stranded positive RNA virus with

a genome length of ~30 kb (1). Among

the structural proteins encoded by its genome, the spike protein

consists of the S1 (S protein 1) and S2 (S protein 2) subunits, and

binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the surface of

the host cells via a receptor-binding domain (RBD), mediating viral

invasion and triggering infection. The process relies on the

activation of S protein cleavage by host proteases, namely

transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) (2). The highly transmissible nature of the

virus allows for widespread dissemination through droplets, contact

and aerosolization, resulting in progression from asymptomatic

infection to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome

and multi-organ failure with heterogeneous clinical presentations

(3,4). Elderly patients with comorbid diseases

have significantly higher rates of severe illness and mortality,

highlighting the key role of host genetic background and viral

interactions in the process of the disease (5). The long-term consequences of viral

infections are gradually becoming apparent, with ~10-30% of

recovered patients experiencing persistent fatigue, cognitive

impairment and multi-system functional abnormalities; this

phenomenon has been defined as long COVID (6).

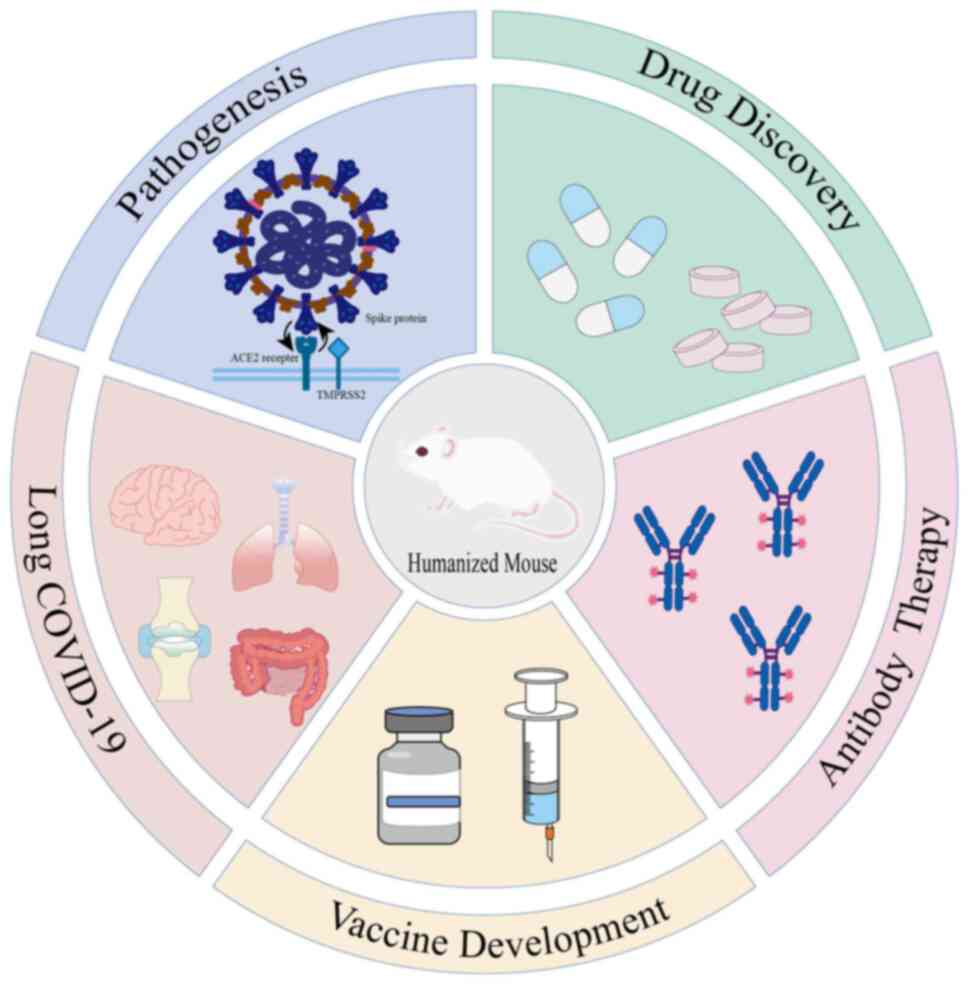

In order to reveal the viral pathogenesis and

develop intervention strategies, it has become imperative to

establish animal models that can mimic human pathological

characteristics. The mouse, as the most convenient laboratory

mammal, is an ideal candidate due to its well-characterized genetic

background and short reproductive cycle. While studies have

identified alternative transmembrane proteins, such as CD147 and

CD26 that may facilitate viral entry, ACE2 remains the primary

gateway for SARS-CoV-2 to enter host cells (7). However, a natural species barrier

exists: The mouse ACE2 (mACE2) receptor differs from human ACE2

(hACE2) at key amino acid residues, rendering mice naturally

insensitive to SARS-CoV-2(8). This

biological bottleneck has driven researchers to develop humanized

mouse models through genetic engineering and immune reconstitution

techniques. These models introduce human genes, cells, or tissues

into immunodeficient mice to overcome species restrictions and

replicate human infection characteristics. Numerous studies

(9-13)

have demonstrated the utility of humanized mouse models in COVID-19

research, including applications in viral pathogenesis, antiviral

drug discovery and vaccine development. The present review aimed to

systematically document the construction strategies of receptor

humanization, immune system humanization and composite humanization

models. We highlight their translational value in elucidating

virus-host interactions, developing broad-spectrum antiviral

therapies, optimizing antibody-based treatments and investigating

the pathophysiology of long COVID (Fig.

1).

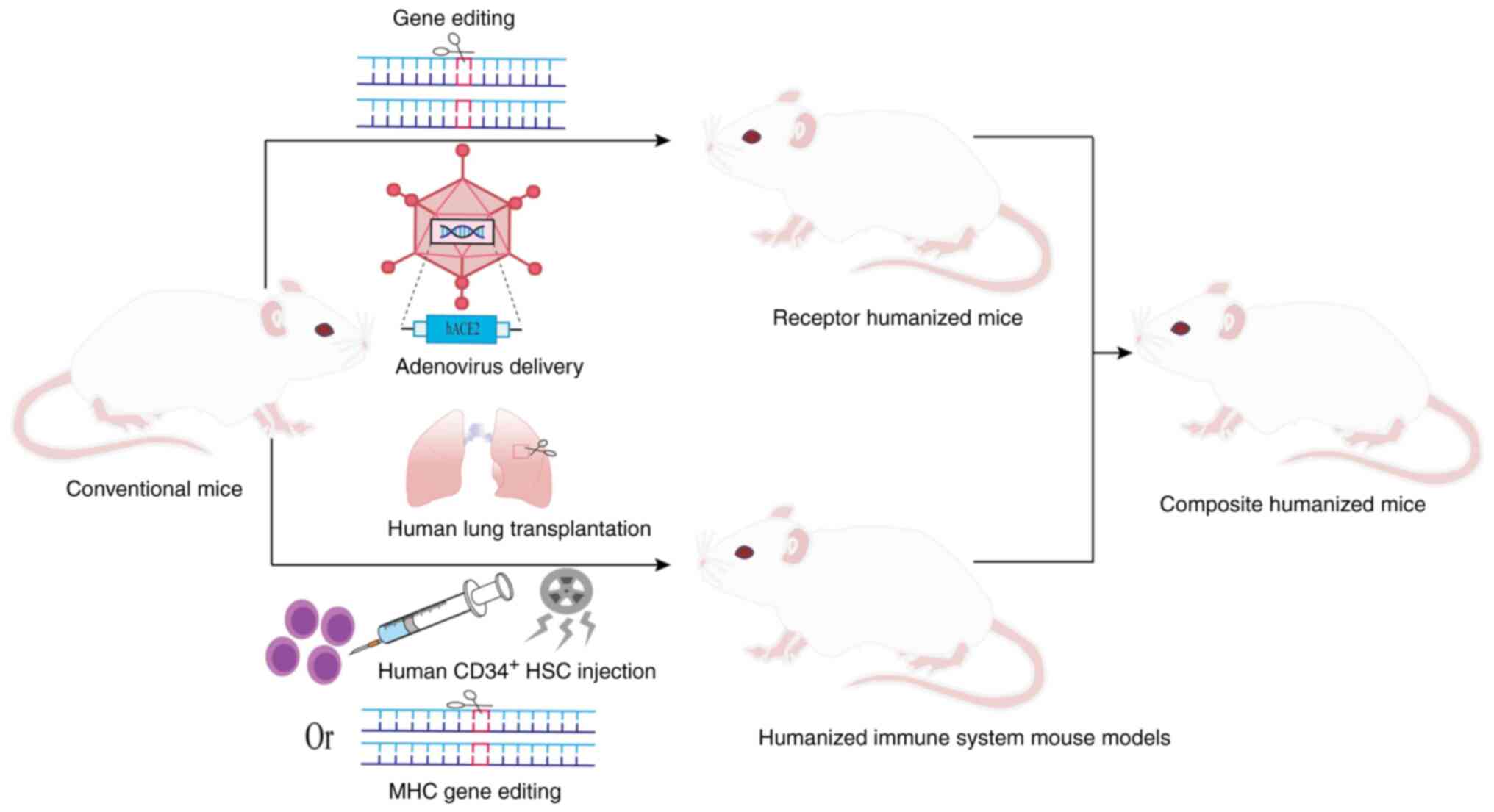

To overcome the species barrier and simulate human

SARS-CoV-2 infection, a variety of humanization strategies have

been employed (Fig. 2), as described

below.

Receptor humanized mouse models were constructed to

systematically mimic the functional properties of human receptors.

K18 (cytokeratin 18)-hACE2 transgenic mice expressing hACE2 under

the K18 promoter are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2(14). In the hACE2 mouse model created by

Snouwaert et al (15) using

homologous substitution, mouse promoter-driven ACE2 was highly

expressed in airway club cells, whereas human promoter-driven ACE2

was expressed in alveolar type II cells. Ge et al (16) developed a fully humanized ACE2 mouse

model that achieves tissue distribution and expression levels

closer to those of human ACE2, thereby avoiding the expression

abnormalities caused by heterologous promoters. Using clustered

regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 to

introduce a single amino acid substitution (H353K) in the

mouse ACE2 gene, the mACE2H353K mouse model was

successfully constructed (17,18). The

application of complementary embryonic stem cell and tetraploid

techniques has greatly accelerated model construction (19). hACE2-knock-in (KI) mice constructed

by knocking hACE2 into mice via CRISPR-Cas technology have been

used to study the mechanisms of pulmonary-intestinal dual

infections and intestinal flora disruption and the pathology of tau

protein in long COVID (20,21). Similarly, the generation of

hACE2-KI-NOD/SCID gamma (NSG) mice by replacing mACE2 with hACE2 in

NSG-immunodeficient mice significantly enhances their viral

susceptibility (22). Furthermore,

using hACE2 and/or hTMPRSS2 KI mice, researchers have found that

Delta strains utilize membrane fusion for host entry, whereas

Omicron strains employ endocytic pathways (23).

The use of conditional regulation systems enables

the spatiotemporal control of receptor expression. Beyond

hACE2-floxed (flanked by loxP sites) mice constructed by Cre

recombinase-mediated knockout (24),

an inducible bi-gene system was developed to tandemly connect hACE2

with green fluorescent protein downstream of the floxed STOP

cassette, achieve spatiotemporal specific expression by

tamoxifen-induced Ubi-Cre (ubiquitin promoter-driven Cre

recombinase) (25). This research

was extended to non-ACE2 receptors and synergistic mechanisms

through the humanized dendritic cell (hDC)-specific intercellular

adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin (SIGN) mouse model

constructed by replacing mouse CD209a with human DC-SIGN (26), as well as through a humanized

transferrin receptor (hTfR) mouse model (27) and a humanized model of the CD147

receptor (28). Among them, the

severity of pulmonary fibrosis in the hCD147 mouse model exceeds

that of the conventional hACE2 model. A summary of the general

information on receptor-based construction of humanized mouse

models is presented in Table I.

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is known

as the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system in humans and is

crucial for adaptive immunity. In the humanized mouse models of the

immune system, a DRAGA mouse model was constructed by the

post-irradiation infusion of HLA-matched umbilical cord

blood-derived CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and

combined with transgenic technology to stably express HLA in the

thymus (29,30). This design not only avoids

graft-vs.-host disease but also promotes immunoglobulin class

switching in human B cells, enabling long-term stable immune system

reconstitution. Humanized HLA transgenic mice mimic human T-cell

epitope presentation and post-vaccination immune responses, which

avoid the severe pathological manifestations caused by the high

susceptibility of traditional hACE2 transgenic mice (31,32).

Furthermore, the humanized mouse model of the localized lung was

constructed by transplanting human lung tissues into

immunodeficient mice. In the SCID-hu model, transplanted human

fetal lung tissues developed mature bronchioles, alveolar sacs, and

vascular systems, and expressed the key receptor ACE2, providing

target cells for SARS-CoV-2 infection (33). Similarly, the NSG-L model

demonstrated efficient viral replication in grafts through the

subcutaneous implantation of human lung tissue (34).

The construction of composite humanized mouse models

can more comprehensively and accurately simulate human infection

and immune response to SARS-CoV-2 than a single humanized mouse.

The MISTRG6 model supports the development of human myeloid and

lymphoid lineage cells by replacing the corresponding mouse genes

with human homologs. This model further achieves the dual

humanization of the immune system and receptor expression by

combining adeno-associated virus delivery of hACE2 to the lung

(35-37).

Similarly, the respiratory tract and immune system humanization in

immunodeficient mice is achieved by the adenoviral delivery of the

hACE2 gene to the lung of NIKO mice, combined with CD34+

HSCs transplantation (38). The

HHD-DR1 model combines immune system and receptor humanization by

knocking out mouse MHC molecules, introducing human MHC alleles,

and driving hACE2 expression in the lung and brain (39). Additionally, the Alpha variant was

found to be more infectious than the earlier virus 614D in the

TKO-BLT-L mouse model constructed by transplanting bone marrow,

liver, thymus and autologous lung tissue grafts (40). The HNFL mouse model constructed by

combining human lung tissues with myeloid-enhanced immune system

revealed the central role of myeloid immune cells in protecting

lung tissues from SARS-CoV-2 infection (41). It is recommended that constructing

single-, dual- and triple-gene composite models through precise

knock-in of human ACE2, TMPRSS2 and Fcγ genes can meet the

requirements for co-expression of multiple receptors (42).

In summary, the humanized mouse models constructed

by various strategies lay an important foundation for the study of

the pathogenic mechanism of SARS-CoV-2, the discovery of

anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs and the development of vaccines.

The humanized mouse model has greatly enhanced the

understanding of the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and provides a key

basis for targeted therapy and for predicting the progression of

the disease. Ye et al (43)

demonstrated that, in hACE2 mice, that the virus targets

non-neuronal olfactory epithelial cells, causing structural damage,

immune cell infiltration and the downregulation of olfactory

receptor genes, mirroring the transient anosmia of patients with

COVID-19. A previous study using the K18-hACE2 model revealed that

SARS-CoV-2 induces non-classical NLR family pyrin domain containing

3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation via caspase-11, promoting the

release of IL-1β/IL-18 and aggravating lung inflammation and

mortality (9). In hACE2 mice, the

RBD binding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to ACE2 on mast cells

triggers aggregation, degranulation, histamine and protease

release, causing tracheobronchial and lung inflammation (44,45).

Sefik et al (37) further

demonstrated that, in MISTRG6-hACE2 mice, infected macrophages

activated the NLRP3 inflammasome following viral uptake via CD16

and ACE2, driving chronic lung fibrosis. Additionally, neutrophils

combat infection via phagocytosis, cytotoxic mediators and

neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). In K18-hACE2 mice, NETs trap

SARS-CoV-2 particles; however, their excessive release damages

tissue, highlighting the dual role of NETs (46). Notably, host factors play a key role

in viral pathogenesis. Chuang et al (47) found that, in hACE2-KI mice, spike

protein enhances viral susceptibility by activating ACE2

phosphorylation, inhibiting its degradation and promoting exosomal

ACE2 propagation. The SARS-CoV-2 virulence factor, open reading

frame (ORF)8 enhances pathogenicity by modulating host immune

dynamics, including early interferon enhancement and late

inflammatory suppression. Its deletion has been shown to reduce the

mortality of K18-hACE2 mice by 40% (48). These models not only clarify the

pathogenic mechanisms of COVID-19, but also provide a basis for

immunomodulation strategies, such as inflammasome inhibition.

The interplay between the age, sex and genetic

background of the host, and viral virulence significantly

influences the disease course of COVID-19. For example, aged hACE2

mice infected with SARS-CoV-2 exhibit high mortality rates due to

suppressed early inflammatory responses in lung endothelial cells.

Additionally, the mortality rate in middle-aged male mice following

high-dose infection (80%) far exceeds that in females (40%),

reflecting the age and sex-related risk profiles observed in human

cases of COVID-19 (49,50). Conversely, Haoyu et al

(51) demonstrated that hACE2 mice

with premature aging exhibit only mild pathology post-infection,

indicating that progeria itself is not a direct risk factor for

severe COVID-19. Furthermore, Snouwaert et al (15) identified tissue-specific and

sex-specific differences in ACE2 expression in hACE2 mice.

García-Ayllón et al (52)

observed that the reduction in full-length ACE2 and the increase in

truncated forms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in K18-hACE2 mice

closely resembled the ACE2 dynamics during the acute phase of

infection in humans. The expression levels and isoform dynamics of

ACE2 provide further insight into the molecular basis of host

susceptibility.

Inhibitors targeting key enzymes of viral

replication exhibit significant promise. The small-molecule

compound 172 can target the 3-chymotrypsin-like protease variant of

SARS-CoV-2 and inhibit its dimerization to block viral replication.

Chan et al (60) found that

compound 172 significantly reduced the viral load in K18-hACE2 mice

and demonstrated broad-spectrum antiviral activity against various

SARS-CoV-2 variants and human coronaviruses. Additionally,

SARS-CoV-2 infection upregulates the host cathepsin L (CTSL), which

facilitates viral entry by cleaving S protein. Zhao et al

(10) observed that amantadine, a

CTSL inhibitor, significantly reduced viral load and alleviated

pathological lung damage in hACE2 mice, highlighting the potential

of CTSL as a therapeutic target. Moreover, the SARS-CoV-2 spike

protein induces metabolic reprogramming in hACE2 mouse hepatocytes.

Mercado-Gómez et al (61)

found that metformin reduced the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and

attenuated metabolic disorders by modulating ACE2 expression and

metabolic pathways, providing a novel therapeutic approach for

patients with metabolic liver disease and COVID-19. Given the high

mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2, developing drugs targeting host

factors is essential to prevent resistance. Frasson et al

(62) identified multiple SARS-CoV-2

variants co-dependent on host genes involved in oxidative stress

and mitochondrial function-related pathways. The antioxidant

N-acetylcysteine significantly reduced variant infection in

hACE2 mice by inhibiting reactive oxygen species production

required for early viral replication (62). Notably, Deshpande et al

(63) found that SARS-CoV-2

infection may alter the pharmacokinetics of metabolic enzymes and

transport proteins in hACE2 mice. This underscores the need for a

systematic assessment of drug-host interactions and optimization of

clinical drug safety.

The interaction of RBD with host cell ACE2 receptors

is critical for SARS-CoV-2 invasion. Clinical antibodies mostly

neutralize the virus by blocking this interaction, and some of

these also enhance the antiviral capacity through Fc-mediated

effector functions, such as the clearance of infected cells and the

activation of immune responses (72). For example, monoclonal antibody (mAb)

ch2H2 and h11B11 both target the host ACE2 receptor to block viral

binding. These antibodies exhibit broad-spectrum neutralization in

the K18-hACE2 mouse model and are effective against various

mutants, including the Omicron variant (11,73).

Conversely, the 17T2 mAb targets a conserved region within the

receptor-binding motif of the spike protein, maintaining

pan-neutralizing activity against Omicron subvariants (BA.5, XBB)

and demonstrating preventive and therapeutic efficacy in K18-hACE2

mice (74). Another notable mAb,

NT-193, exhibits broad neutralizing activity against

SARS-associated coronaviruses by targeting a conserved RBD site in

the heavy chain and blocking ACE2 binding in the light chain

(75). However, the efficacy of mAbs

may be compromised by viral variation. Polyclonal antibodies

(PAbs), which target multiple epitopes, may provide greater

efficacy against mutant strains compared to mAbs. Vanhove et

al (76) demonstrated that the

polyclonal antibody, XAV-19, targeted multiple epitopes without

inducing drug-resistant mutations. This antibody significantly

reduced viral load in hACE2 mouse lung tissues, highlighting the

potential advantages of PAbs in mitigating the impact of viral

evolution (76).

Antibodies that simultaneously target multiple

antigens with a single molecule provide advantages over traditional

mAb cocktails. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 spike-targeting

bispecific T-cell engager (S-BiTE) blocks viral entry and activates

T-cell-mediated clearance of infected cells. Li et al

(80) demonstrated that, in hACE2

mice, the viral load was significantly lower in the S-BiTE

treatment group compared to the neutralizing antibody-only group,

with comparable effects on the original strain and the Delta

variant. Additionally, it was previously demonstrated that both

bispecific humanized heavy chain antibodies and the IgG-VHH

bispecific antibody, SYZJ001, exhibited protective efficacy in

prophylactic and therapeutic experiments in hACE2 mice (81,82).

Furthermore, Titong et al (83) found that intranasal prophylaxis with

the tri-specific antibody, ABS-VIR-001, prevented infection and

mortality in hACE2 mice, with a 50-fold reduction in viral load

post-treatment. These findings highlight the potential of

multi-specific antibodies in enhancing therapeutic efficacy and

reducing the risk of viral escape.

Humanized mice mimic the human immune response and

are used in vaccine development to assess immunogenicity, safety

and to explore new formulations and vaccination strategies. Turan

et al (12) found that

K18-hACE2 mice vaccinated with the inactivated OZG-38.61.3 vaccine

had significantly lower mean viral loads in the high-dose group

compared to unvaccinated infected controls, without observing

significant toxicity, providing crucial evidence for clinical

translation. Tai et al (87)

demonstrated that an mRNA vaccine encapsulated in lipid

nanoparticles induced a potent CD8+ T-cell response in

humanized HLA transgenic mice. Freitag et al (88) investigated adenoviral vector 5

vaccines (Ad5-RBD and Ad5-S) and found that intranasal vaccination

in humanized HLA mice elicited mucosal IgA/IgG-neutralizing

antibodies and cytotoxic T-cell responses, providing effective

protection against the Beta variant. Compared to intramuscular

injection, intranasal administration avoids systemic viral vector

dissemination, enhancing safety and presenting a viable alternative

or supplement to existing vaccines. Gu et al (89) validated the Ad5 vector-based vaccine

in the hACE2 mouse model, demonstrating no adverse effects on

myocardial function even at high doses. This confirms its cardiac

safety and provides an experimental basis for vaccinating high-risk

cardiovascular patients (89).

Additionally, García-Arriaza et al (90) demonstrated that the modified vaccinia

virus Ankara (MVA) vector vaccine, MVA-S, exhibited potent

immunogenicity and complete protective efficacy in hACE2 mice. A

single dose prevented lethal infection, while two doses cleared the

pulmonary virus, supporting its clinical translation (90). These findings highlight the potential

of various vaccine platforms in combating SARS-CoV-2 and its

variants.

While mRNA and viral vector vaccines have

significantly advanced prevention strategies for COVID-19, their

long-term safety, particularly in vulnerable populations such as

children, pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals, and

their cross-protective efficacy against emerging mutants, remain

areas for improvement. Recombinant subunit vaccines provide a

promising alternative due to their established safety and

tolerability. For instance, Baiya-Vax-2, a recombinant plant-based

SARS-CoV-2 RBD vaccine, induced high levels of neutralizing

antibodies in K18-hACE2 mice, and two doses of the vaccine

significantly lowered viral loads and prevented severe disease

(91). The immunogenicity of the

vaccine can be further enhanced by targeting strategies. Marlin

et al (92) found that

subunit vaccines targeting the viral antigen CD40-expressing

antigen-presenting cells (αCD40.RBD) induced specific T-cell and

B-cell responses in immune-system-humanized mice and established a

persistent immune memory.

Vaccines have been effective in preventing COVID-19;

however, concerns regarding vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory

disease (VAERD) persist. Although the vaccine reduces viral load

and mortality in hACE2 mice, it may trigger VAERD due to Th2/Th17

immune bias, manifested by pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration and

IL-17-mediated systemic inflammation, which underscores the need

for balanced immune responses and avoidance of the risk of Th2/Th17

pathology in vaccine development (93). T-cell epitopes are essential in

immunity, with CD4+ T-cells regulating immune responses

and CD8+ T-cells eliminating infected cells. Humanized

MHC transgenic mouse models can generate specific cellular immune

responses after inoculation with inactivated viruses, enabling

rapid screening of T cell epitopes and accelerating vaccine design

(94). Beyond conventional vaccine

targets, regions of the virus not typically covered by existing

vaccines are gaining attention as potential breakthroughs. The

study by Weingarten-Gabbay et al (95) found that nonclassical ORF epitopes

induced a more potent IFN-γ+ T-cell response associated

with early viral protein expression and were more immunogenic than

classical epitopes in immune-system-humanized mice. This suggests

that non-classical epitopes may provide novel targets for vaccine

design (95). Targeting highly

conserved B-cell epitopes in spike protein or conserved T-cell

epitopes in multiple coronaviruses induces potent neutralizing

antibodies and cross-reactive T-cell responses in humanized mice.

This approach markedly reduces viral load and attenuates lung

inflammation (31,96). These findings highlight the central

value of conserved epitopes in overcoming viral mutations and

cross-species transmission, laying the groundwork for the

development of a pan-coronavirus vaccine.

In summary, humanized mouse models not only provide

an essential preclinical platform for refining current vaccines,

but also represent a critical technology for addressing future

coronavirus outbreaks.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has transitioned into

a phase of normalized prevention and control, the potential risk of

SARS-CoV-2-induced long COVID remains a key concern. Long COVID is

defined as a multisystem syndrome with symptoms persisting for ≥12

weeks post-infection, characterized by pulmonary fibrosis,

cognitive impairment, and multiorgan dysfunction (13). The heterogeneous clinical

presentation of long COVID is linked to multifactorial pathogenic

mechanisms, including persistent viral residues, autoimmune

abnormalities, and chronic inflammatory cascades (97). Lung fibrosis is a hallmark of long

COVID. Cui et al (98)

simulated long COVID lung fibrosis in a humanized mouse model and

found that chronic immune activation drove fibroblast

differentiation and extracellular matrix deposition, leading to

irreversible lung injury. Additionally, Heath et al

(99) discovered that the SARS-CoV-2

spike protein disrupts the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

(RAAS), exacerbating coagulation abnormalities and inhibiting

fibrinolysis in hACE2-KI mice. This disruption leads to

thromboembolic cerebrovascular complications and cognitive

impairment (99). Similarly, the

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was found to exacerbate cerebrovascular

oxidative stress and inflammation through the activation of

RAAS-damaging pathways, resulting in vascular thinning and

deteriorated cognitive function in diabetic hACE2 mice (100). These studies, leveraging humanized

mouse models, have unveiled the pathological mechanisms of long

COVID and provided a foundation for clinical interventions

targeting immunomodulation and RAAS pathways.

Humanized mouse models have revealed that long-term

residual SARS-CoV-2 RNA is associated with skeletal system

abnormalities. Using K18-hACE2 mice, Haudenschild et al

(101) found that the spike protein

increased the risk of fractures by triggering osteoclast

activation, bone loss and the thinning of the growth plate. This

occurs either through direct binding to skeletal cell ACE2

receptors or indirectly through inflammatory hypoxia (101). Notably, SARS-CoV-2 can also infect

the gastrointestinal tract and disrupt intestinal flora-host

interactions. Research using the hACE2 mouse model has demonstrated

that viral infection triggers intestinal barrier damage and flora

disruption, characterized by a reduction in the amounts of

beneficial bacteria and the proliferation of opportunistic

pathogens. This leads to abnormally high flora diversity even in

mild infections. Among these changes, the persistent reduction of

the mucosal immune-critical bacterium Akkermansia

muciniphila has been shown to be significantly associated with

fatigue and gastrointestinal symptoms in long COVID (20,102).

The study by Edwinson et al (103) using colony-humanized mice, further

demonstrated that the gut flora reduces the risk of viral

infections by inhibiting ACE2 expression. The regulation of ACE2 by

healthy flora is stable, providing a theoretical basis for

colony-targeted intervention strategies such as probiotic

modulation (103). These findings

indicate that the sequelae of COVID-19 not only involve the

respiratory and cardiovascular systems, but that interactions

between the skeletal, intestinal and immune systems may also lead

to long-term health issues, underscoring the need for comprehensive

management of the long-term effects of the virus.

Although the present review systematically

summarizes the key applications of humanized mouse models using in

the research into SARS-CoV-2, certain limitations remain. Firstly,

due to the uncertainty of ongoing virus evolution, the strategies

for model construction (e.g., reliance on hACE2) and validation

(e.g., a particular antibody or vaccine) are often based on ‘then

known’ viral characteristics. The predictive value of the original

highly specialized model may be reduced or even invalidated when a

mutant strain with an altered invasion pathway emerges. Secondly,

as regards the models themselves, even with the most advanced

construction strategies, humanized mice struggle to fully replicate

the complexity of the human immune system (38). On the one hand, these models are

typically established on immunodeficient backgrounds, making it

difficult to reproduce the complete immune network and interactions

within the tissue microenvironment. On the other hand, the majority

of models focus on reconstructing specific receptors or

single-organ functions, failing to accurately reflect the systemic

dynamic responses and multi-organ coordination mechanisms triggered

by the virus (17,40). Simultaneously, fundamental

differences exist between humans and mice in basic physiological

structures, metabolic rates, and lifespan, resulting in significant

shortcomings, particularly in simulating chronic pathological

processes, such as ‘long COVID’. Additionally, the present review

primarily relied on published literature and may not incorporate

the latest preprints or ongoing research findings in a timely

manner. In summary, while humanized mice provide a crucial platform

for SARS-CoV-2 research, careful evaluation of their

representativeness and applicability is essential when translating

findings to clinical settings.

Humanized mouse models have been pivotal in

uncovering SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity and driving intervention

strategies since the epidemic's onset. Through gene editing,

receptor optimization and other technologies, researchers have

constructed receptor humanized, immune humanized and composite

humanized models to systematically simulate the infection

characteristics and pathological process of COVID-19. Receptor

humanization models have not only revealed the ACE2-dependent

mechanism of viral invasion, but have also led to the discovery of

the roles of novel co-receptors, such as CD147, TfR and DC-SIGN,

which laid the foundation for multi-target drug design. In addition

to breaking the species barrier by modifying viral receptors, the

reconstruction of the human immune lineage can more comprehensively

mimic the host immune response to COVID-19. Immune humanization

models recapitulated the human-specific T/B cell response and the

abnormal activation of myeloid lineage cells, and elucidated the

roles of immune imbalance in long-term sequelae. By integrating

human receptors and the immune system, the composite humanization

model recapitulates the complex phenotypes of long-term viral

retention, pulmonary fibrosis and neurodegeneration at the animal

level, which provides important clues to analyze the mechanism of

long COVID. These models validate the effectiveness of

broad-spectrum antiviral strategies targeting ACE2, and they also

accelerate the clinical translation of antibody cocktails,

bispecific antibodies and mucosal vaccines.

Although significant progress has been made in the

development of humanized mouse models, numerous challenges persist.

Discrepancies in the spatial and temporal expression patterns of

receptors compared to real human tissues can impact mechanistic

accuracy. A novel live-virus-free mouse model has been developed,

which obviates the need for viral adaptation or humanization. By

administering GU-enriched ribooligonucleotides (mimicking the

Delta/Omicron variant) via an oropharyngeal drip in combination

with low-dose bleomycin-induced lung injury, this model

successfully replicates key COVID-19 pathological features

(104). Existing models

predominantly focus on the acute infection phase, providing limited

insight into long-term COVID-19 mechanisms, such as viral latency

and reactivation or multi-organ interactions. Moreover, the low

replication of the Omicron variant in some models reveals

insufficient simulation of receptor-protease co-evolution. Further

research is required to focus on developing modular rapid-response

systems to keep pace with viral mutations.

The future development direction can break through

from the following aspects, for model technology innovation, the

integration of organoid and bioengineering models significantly

improves the accuracy of pathology simulation. The humanized lung

organoid-immunity chimeric model breaks through the bottleneck in

the study of latent viral infections and trans-organ transmission

by synchronously reconstructing the lung tissues and immune

microenvironment (105). The

two-dimensional air-liquid interface system constructed based on

fetal lung bud-tip organoids accurately reproduced the specific

infection of alveolar type II epithelium by SARS-CoV-2 and the

interferon response mechanism (106). Bioengineered lung models

dynamically simulate early COVID-19 infection characteristics by

incorporating pathogen stimulation modules, with standardized

construction systems supporting personalized medicine and

large-scale drug development (107). Dynamic monitoring technologies

combining in vivo imaging and single-cell sequencing enable

the real-time analysis of infection processes. The

68Ga-NOTA-PEP4 PET imaging agent dynamically tracks

changes in hACE2 expression (108),

while radiolabeled pseudoviruses combined with SPECT/CT and PET

imaging allow for the visualization of viral dynamics from invasion

to clearance (109). For model

optimization, the construction of a lung-intestinal-brain

multi-tissue chimera model combined with an inducible viral latent

system can systematically simulate the trans-organ damage mechanism

of long COVID. Notably, the novel finding that the intestinal flora

influences ACE2 expression through metabolic regulation suggests

that the flora-immunity co-humanization model may become a critical

breakthrough for revealing individualized susceptibility

differences.

Not applicable.

Funding: The present study was supported by grants from the

National Key Research and Development Project (grant no.

2023YFC2605603), the Program for Innovative Research Team (in

Science and Technology) in University of Henan Province (grant no.

25IRTSTHN038) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant no. 82273696).

Not applicable.

HY conceptualized the study. XF, YW, YL, JL and FL

performed the literature search. XF wrote the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H,

Wang W, Song H, Huang B, Zhu N, et al: Genomic characterisation and

epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus

origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 395:565–574. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S,

Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH,

Nitsche A, et al: SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2

and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell.

181:271–280.e8. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu

Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, et al: Clinical features of patients

infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet.

395:497–506. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rai P, Kumar BK, Deekshit VK and

Karunasagar I and Karunasagar I: Detection technologies and recent

developments in the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. Appl Microbiol

Biotechnol. 105:441–455. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sursal T, Gandhi CD, Clare K, Feldstein E,

Frid I, Kefina M, Galluzzo D, Kamal H, Nuoman R, Amuluru K, et al:

Significant mortality associated with COVID-19 and comorbid

cerebrovascular disease: A quantitative systematic review. Cardiol

Rev. 31:199–206. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Scholkmann F and May CA: COVID-19,

post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS, ‘long COVID’) and post-COVID-19

vaccination syndrome (PCVS, ‘post-COVIDvac-syndrome’): Similarities

and differences. Pathol Res Pract. 246(154497)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Radzikowska U, Ding M, Tan G, Zhakparov D,

Peng Y, Wawrzyniak P, Wang M, Li S, Morita H, Altunbulakli C, et

al: Distribution of ACE2, CD147, CD26, and other SARS-CoV-2

associated molecules in tissues and immune cells in health and in

asthma, COPD, obesity, hypertension, and COVID-19 risk factors.

Allergy. 75:2829–2845. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Adams LE, Dinnon III KH, Hou YJ, Sheahan

TP, Heise MT and Baric RS: Critical ACE2 determinants of SARS-CoV-2

and group 2B coronavirus infection and replication. mBio.

12:e03149–20. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Rodrigues TS, Caetano CCS, de Sá KSG,

Almeida L, Becerra A, Gonçalves AV, Lopes LS, Oliveira S,

Mascarenhas DPA, Batah SS, et al: CASP4/11 contributes to NLRP3

activation and COVID-19 exacerbation. J Infect Dis. 227:1364–1375.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhao MM, Yang WL, Yang FY, Zhang L, Huang

WJ, Hou W, Fan CF, Jin RH, Feng YM, Wang YC and Yang JK: Cathepsin

L plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans and humanized

mice and is a promising target for new drug development. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 6(134)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Du Y, Shi R, Zhang Y, Duan X, Li L, Zhang

J, Wang F, Zhang R, Shen H, Wang Y, et al: A broadly neutralizing

humanized ACE2-targeting antibody against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat

Commun. 12(5000)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Turan RD, Tastan C, Dilek Kancagi D,

Yurtsever B, Sir Karakus G, Ozer S, Abanuz S, Cakirsoy D,

Tumentemur G, Demir S, et al: Gamma-irradiated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine

candidate, OZG-38.61.3, confers protection from SARS-CoV-2

challenge in human ACEII-transgenic mice. Sci Rep.

11(15799)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Perumal R, Shunmugam L, Naidoo K, Abdool

Karim SS, Wilkins D, Garzino-Demo A, Brechot C, Parthasarathy S,

Vahlne A and Nikolich JŽ: Long COVID: A review and proposed

visualization of the complexity of long COVID. Front Immunol.

14(1117464)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yinda CK, Port JR, Bushmaker T, Offei

Owusu I, Purushotham JN, Avanzato VA, Fischer RJ, Schulz JE,

Holbrook MG, Hebner MJ, et al: K18-hACE2 mice develop respiratory

disease resembling severe COVID-19. PLoS Pathog.

17(e1009195)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Snouwaert JN, Jania LA, Nguyen T, Martinez

DR, Schäfer A, Catanzaro NJ, Gully KL, Baric RS, Heise M, Ferris

MT, et al: Human ACE2 expression, a major tropism determinant for

SARS-CoV-2, is regulated by upstream and intragenic elements. PLoS

Pathog. 19(e1011168)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ge C, Salem AR, Elsharkawy A, Natekar J,

Guglani A, Doja J, Ogala O, Wang G, Griffin SH, Slivano OJ, et al:

Development and characterization of a fully humanized ACE2 mouse

model. BMC Biol. 23(194)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Song IW, Washington M, Leynes C, Hsu J,

Rayavara K, Bae Y, Haelterman N, Chen Y, Jiang MM, Drelich A, et

al: Generation of a humanized mAce2 and a conditional hACE2 mouse

models permissive to SARS-COV-2 infection. Mamm Genome. 35:113–121.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li K, Verma A, Li P, Ortiz ME, Hawkins GM,

Schnicker NJ, Szachowicz PJ, Pezzulo AA, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Kicmal

T, et al: Adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE2H353K mice

reveals new spike residues that drive mouse infection. J Virol.

98(e0151023)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu FL, Wu K, Sun J, Duan Z, Quan X, Kuang

J, Chu S, Pang W, Gao H, Xu L, et al: Rapid generation of ACE2

humanized inbred mouse model for COVID-19 with tetraploid

complementation. Natl Sci Rev. 8(nwaa285)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang Y, Ma Y, Sun W, Zhou X, Wang R, Xie

P, Dai L, Gao Y and Li J: Exploring gut-lung axis crosstalk in

SARS-CoV-2 infection: Insights from a hACE2 mouse model. J Med

Virol. 96(e29336)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Choi CY, Gadhave K, Villano J, Pekosz A,

Mao X and Jia H: Generation and characterization of a humanized

ACE2 mouse model to study long-term impacts of SARS-CoV-2

infection. J Med Virol. 96(e29349)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ma MT, Jiang Q, Chen CH, Badeti S, Wang X,

Zeng C, Evans D, Bodnar B, Marras SAE, Tyagi S, et al: S309-CAR-NK

cells bind the Omicron variants in vitro and reduce SARS-CoV-2

viral loads in humanized ACE2-NSG mice. J Virol.

98(e0003824)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Verma SK, Ana-Sosa-Batiz F, Timis J,

Shafee N, Maule E, Pinto PBA, Conner C, Valentine KM, Cowley DO,

Miller R, et al: Influence of Th1 versus Th2 immune bias on viral,

pathological, and immunological dynamics in SARS-CoV-2

variant-infected human ACE2 knock-in mice. EBioMedicine.

108(105361)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Tang AT, Buchholz DW, Szigety KM, Imbiakha

B, Gao S, Frankfurter M, Wang M, Yang J, Hewins P, Mericko-Ishizuka

P, et al: Cell-autonomous requirement for ACE2 across organs in

lethal mouse SARS-CoV-2 infection. PLoS Biol.

21(e3001989)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bruter AV, Korshunova DS, Kubekina MV,

Sergiev PV, Kalinina AA, Ilchuk LA, Silaeva YY, Korshunov EN,

Soldatov VO and Deykin AV: Novel transgenic mice with Cre-dependent

co-expression of GFP and human ACE2: A safe tool for study of

COVID-19 pathogenesis. Transgenic Res. 30:289–301. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

26

|

Tu Y, Fang Y, Zheng R, Lu D, Yang X, Zhang

L, Li D, Sun Y, Yu W, Luo D and Wang H: A murine model of DC-SIGN

humanization exhibits increased susceptibility against SARS-CoV-2.

Microbes Infect. 26(105344)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Liao Z, Wang C, Tang X, Yang M, Duan Z,

Liu L, Lu S, Ma L, Cheng R, Wang G, et al: Human transferrin

receptor can mediate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

121(e2317026121)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Wu J, Chen L, Qin C, Huo F, Liang X, Yang

X, Zhang K, Lin P, Liu J, Feng Z, et al: CD147 contributes to

SARS-CoV-2-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Signal Transduct Target

Ther. 7(382)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Brumeanu TD, Vir P, Karim AF, Kar S,

Benetiene D, Lok M, Greenhouse J, Putmon-Taylor T, Kitajewski C,

Chung KK, et al: Human-immune-system (HIS) humanized mouse model

(DRAGA: HLA-A2.HLA-DR4.Rag1KO.IL-2RγcKO.NOD) for COVID-19. Hum

Vaccin Immunother. 18(2048622)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Brumeanu TD, Vir P, Karim AF, Kar S,

Benetiene D, Lok M, Greenhouse J, Putmon-Taylor T, Kitajewski C,

Chung KK, et al: A Human-Immune-System (HIS) humanized mouse model

(DRAGA: HLA-A2. HLA-DR4. Rag1 KO.IL-2Rγc KO. NOD) for COVID-19.

bioRxiv [Preprint]: 2020.08.19.251249, 2021.

|

|

31

|

Prakash S, Srivastava R, Coulon PG,

Dhanushkodi NR, Chentoufi AA, Tifrea DF, Edwards RA, Figueroa CJ,

Schubl SD, Hsieh L, et al: Genome-wide asymptomatic B-Cell, CD4

+ and CD8 + T-cell epitopes, that are highly

conserved between human and animal coronaviruses, identified from

SARS-CoV-2 as immune targets for pre-emptive pan-coronavirus

vaccines. bioRxiv [Preprint]: 2020.09.27.316018, 2020.

|

|

32

|

Li S, Han X, Hu R, Sun K, Li M, Wang Y,

Zhao G, Li M, Fan H and Yin Q: Transcriptomic profiling reveals

SARS-CoV-2-infected humanized MHC mice recapitulate human post

vaccination immune responses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

15(1634577)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Fu W, Wang W, Yuan L, Lin Y, Huang X, Chen

R, Cai M, Liu C, Chen L, Zhou M, et al: A SCID mouse-human lung

xenograft model of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Theranostics.

11:6607–6615. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Sun R, Zhao Z, Fu C, Wang Y, Guo Z, Zhang

C, Liu L, Zhang C, Shu C, He J, et al: Humanized mice for

investigating SARS-CoV-2 lung infection and associated human immune

responses. Eur J Immunol. 52:1640–1647. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Sefik E, Israelow B, Zhao J, Qu R, Song E,

Mirza H, Kaffe E, Halene S, Meffre E, Kluger Y, et al: A humanized

mouse model of chronic COVID-19 to evaluate disease mechanisms and

treatment options. Res Sq [Preprint]: rs.3.rs-279341, 2021.

|

|

36

|

Sefik E, Israelow B, Mirza H, Zhao J, Qu

R, Kaffe E, Song E, Halene S, Meffre E, Kluger Y, et al: A

humanized mouse model of chronic COVID-19. Nat Biotechnol.

40:906–920. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sefik E, Qu R, Junqueira C, Kaffe E, Mirza

H, Zhao J, Brewer JR, Han A, Steach HR, Israelow B, et al:

Inflammasome activation in infected macrophages drives COVID-19

pathology. Nature. 606:585–593. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Yong KSM, Anderson DE, Zheng AKE, Liu M,

Tan SY, Tan WWS, Chen Q and Wang LF: Comparison of infection and

human immune responses of two SARS-CoV-2 strains in a humanized

hACE2 NIKO mouse model. Sci Rep. 13(12484)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Le Chevalier F, Authié P, Chardenoux S,

Bourgine M, Vesin B, Cussigh D, Sassier Y, Fert I, Noirat A,

Nemirov K, et al: Mice humanized for MHC and hACE2 with high

permissiveness to SARS-CoV-2 omicron replication. Microbes Infect.

25(105142)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Di Y, Lew J, Goncin U, Radomska A, Rout

SS, Gray BET, Machtaler S, Falzarano D and Lavender KJ: SARS-CoV-2

variant-specific infectivity and immune profiles Are detectable in

a humanized lung mouse model. Viruses. 14(2272)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Kenney DJ, O'Connell AK, Turcinovic J,

Montanaro P, Hekman RM, Tamura T, Berneshawi AR, Cafiero TR, Al

Abdullatif S, Blum B, et al: Humanized mice reveal a

macrophage-enriched gene signature defining human lung tissue

protection during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep.

39(110714)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Jarnagin K, Alvarez O, Shresta S and Webb

DR: Animal models for SARS-Cov2/Covid19 research-A commentary.

Biochem Pharmacol. 188(114543)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ye Q, Zhou J, He Q, Li RT, Yang G, Zhang

Y, Wu SJ, Chen Q, Shi JH, Zhang RR, et al: SARS-CoV-2 infection in

the mouse olfactory system. Cell Discov. 7(49)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Cao JB, Zhu ST, Huang XS, Wang XY, Wu ML,

Li X, Liu FL, Chen L, Zheng YT and Wang JH: Mast cell

degranulation-triggered by SARS-CoV-2 induces tracheal-bronchial

epithelial inflammation and injury. Virol Sin. 39:309–318.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wu ML, Liu FL, Sun J, Li X, He XY, Zheng

HY, Zhou YH, Yan Q, Chen L, Yu GY, et al: SARS-CoV-2-triggered mast

cell rapid degranulation induces alveolar epithelial inflammation

and lung injury. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

6(428)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Dos Ramos Almeida CJL, Veras FP, Paiva IM,

Schneider AH, da Costa Silva J, Gomes GF, Costa VF, Silva BMS,

Caetite DB, Silva CMS, et al: Neutrophil virucidal activity against

SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Infect

Dis. 229:1352–1365. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Chuang HC, Hsueh CH, Hsu PM, Huang RH,

Tsai CY, Chung NH, Chow YH and Tan TH: SARS-CoV-2 spike protein

enhances MAP4K3/GLK-induced ACE2 stability in COVID-19. EMBO Mol

Med. 14(e15904)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Bello-Perez M, Hurtado-Tamayo J, Mykytyn

AZ, Lamers MM, Requena-Platek R, Schipper D, Muñoz-Santos D,

Ripoll-Gómez J, Esteban A, Sánchez-Cordón PJ, et al: SARS-CoV-2

ORF8 accessory protein is a virulence factor. mBio.

14(e0045123)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Park U, Lee JH, Kim U, Jeon K, Kim Y, Kim

H, Kang JI, Park MY, Park SH, Cha JS, et al: A humanized ACE2 mouse

model recapitulating age- and sex-dependent immunopathogenesis of

COVID-19. J Med Virol. 96(e29915)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Subramaniam S, Kenney D, Jayaraman A,

O'Connell AK, Walachowski S, Montanaro P, Reinhardt C, Colucci G,

Crossland NA, Douam F and Bosmann M: Aging is associated with an

insufficient early inflammatory response of lung endothelial cells

in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Immunol. 15(1397990)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Haoyu W, Meiqin L, Jiaoyang S, Guangliang

H, Haofeng L, Pan C, Xiongzhi Q, Kaixin W, Mingli H, Xuejie Y, et

al: Premature aging effects on COVID-19 pathogenesis: New insights

from mouse models. Sci Rep. 14(19703)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

García-Ayllón MS, Moreno-Pérez O,

García-Arriaza J, Ramos-Rincón JM, Cortés-Gómez M, Brinkmalm G,

Andrés M, León-Ramírez JM, Boix V, Gil J, et al: Plasma ACE2

species are differentially altered in COVID-19 patients. FASEB J.

35(e21745)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Lu T, Zhang C, Li Z, Wei Y, Sadewasser A,

Yan Y, Sun L, Li J, Wen Y, Lai S, et al: Human

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-specific antisense oligonucleotides

reduce infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

154:1044–1059. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Ikemura N, Taminishi S, Inaba T, Arimori

T, Motooka D, Katoh K, Kirita Y, Higuchi Y, Li S, Suzuki T, et al:

An engineered ACE2 decoy neutralizes the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant

and confers protection against infection in vivo. Sci Transl Med.

14(eabn7737)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Zhang L, Dutta S, Xiong S, Chan M, Chan

KK, Fan TM, Bailey KL, Lindeblad M, Cooper LM, Rong L, et al:

Engineered ACE2 decoy mitigates lung injury and death induced by

SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Chem Biol. 18:342–351. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Zhang L, Dutta S, Xiong S, Chan M, Chan

KK, Fan TM, Bailey KL, Lindeblad M, Cooper LM, Rong L, et al:

Engineered high-affinity ACE2 peptide mitigates ARDS and death

induced by multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants. bioRxiv [Preprint]:

2021.12.21.473668, 2021.

|

|

57

|

Hwang J, Kim BK, Moon S, Park W, Kim KW,

Yoon JH, Oh H, Jung S, Park Y, Kim S, et al: Conversion of host

cell receptor into virus destructor by immunodisc to neutralize

diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants. Adv Healthc Mater.

13(e2302803)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Dong W, Wang J, Tian L, Zhang J, Mead H,

Jaramillo SA, Li A, Zumwalt RE, Whelan SPJ, Settles EW, et al: FXa

cleaves the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and blocks cell entry to

protect against infection with inferior effects in B.1.1.7 variant.

bioRxiv [Preprint]: 2021.06.07.447437, 2021.

|

|

59

|

Yu F, Liu X, Ou H, Li X, Liu R, Lv X, Xiao

S, Hu M, Liang T, Chen T, et al: The histamine receptor H1 acts as

an alternative receptor for SARS-CoV-2. mBio.

15(e0108824)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Chan CC, Guo Q, Chan JF, Tang K, Cai JP,

Chik KK, Huang Y, Dai M, Qin B, Ong CP, et al: Identification of

novel small-molecule inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 by chemical genetics.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 14:4028–4044. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Mercado-Gómez M, Prieto-Fernández E,

Goikoetxea-Usandizaga N, Vila-Vecilla L, Azkargorta M, Bravo M,

Serrano-Maciá M, Egia-Mendikute L, Rodríguez-Agudo R,

Lachiondo-Ortega S, et al: The spike of SARS-CoV-2 promotes

metabolic rewiring in hepatocytes. Commun Biol.

5(827)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Frasson I, Diamante L, Zangrossi M,

Carbognin E, Pietà AD, Penna A, Rosato A, Verin R, Torrigiani F,

Salata C, et al: Identification of druggable host dependency

factors shared by multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. J Mol

Cell Biol. 16(mjae004)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Deshpande K, Lange KR, Stone WB, Yohn C,

Schlesinger N, Kagan L, Auguste AJ, Firestein BL and Brunetti L:

The influence of SARS-CoV-2 infection on expression of

drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in a hACE2 murine model.

Pharmacol Res Perspect. 11(e01071)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Mazzarella L, Santoro F, Ravasio R,

Fumagalli V, Massa PE, Rodighiero S, Gavilán E, Romanenghi M, Duso

BA, Bonetti E, et al: Inhibition of the lysine demethylase LSD1

modulates the balance between inflammatory and antiviral responses

against coronaviruses. Sci Signal. 16(eade0326)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Xiong S, Zhang L, Richner JM, Class J,

Rehman J and Malik AB: Interleukin-1RA mitigates SARS-CoV-2-induced

inflammatory lung vascular leakage and mortality in humanized

K18-hACE-2 mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 41:2773–2785.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Botella-Asunción P, Rivero-Buceta EM,

Vidaurre-Agut C, Lama R, Rey-Campos M, Moreno A, Mendoza L,

Mingo-Casas P, Escribano-Romero E, Gutierrez-Adan A, et al: AG5 is

a potent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and immune regulator that

preserves innate immunity. Biomed Pharmacother.

169(115882)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Weiss CM, Liu H, Ball EE, Hoover AR, Wong

TS, Wong CF, Lam S, Hode T, Keel MK, Levenson RM, et al:

N-dihydrogalactochitosan reduces mortality in a lethal mouse model

of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One. 18(e0289139)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Yeung ST, Premeaux TA, Du L, Niki T,

Pillai SK, Khanna KM and Ndhlovu LC: Galectin-9 protects

humanized-ACE2 immunocompetent mice from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Front Immunol. 13(1011185)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Meier M, Becker S, Levine E, DuFresne O,

Foster K, Moore J, Burnett FN, Hermanns VC, Heath SP, Abdelsaid M

and Coucha M: Timing matters in the use of renin-angiotensin system

modulators and COVID-related cognitive and cerebrovascular

dysfunction. PLoS One. 19(e0304135)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Silva-Santos Y, Pagni RL, Gamon THM, de

Azevedo MSP, Bielavsky M, Darido MLG, de Oliveira DBL, de Souza EE,

Wrenger C, Durigon EL, et al: Lisinopril increases lung ACE2 levels

and SARS-CoV-2 viral load and decreases inflammation but not

disease severity in experimental COVID-19. Front Pharmacol.

15(1414406)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

da Silva-Santos Y, Pagni RL, Gamon THM, de

Azevedo MSP, Darido MLG, de Oliveira DBL, Durigon EL, Luvizotto

MCR, Ackerman HC, Marinho CRF, et al: Angiotensin-converting enzyme

inhibition and/or angiotensin receptor blockade modulate cytokine

profiles and improve clinical outcomes in experimental COVID-19

infection. Int J Mol Sci. 26(7663)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Corti D, Purcell LA, Snell G and Veesler

D: Tackling COVID-19 with neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. Cell.

184:3086–3108. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Sun CP, Chiu CW, Wu PY, Tsung SI, Lee IJ,

Hu CW, Hsu MF, Kuo TJ, Lan YH, Chen LY, et al: Development of

AAV-delivered broadly neutralizing anti-human ACE2 antibodies

against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Mol Ther. 31:3322–3336.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

de Campos-Mata L, Trinité B, Modrego A,

Tejedor Vaquero S, Pradenas E, Pons-Grífols A, Rodrigo Melero N,

Carlero D, Marfil S, Santiago C, et al: A monoclonal antibody

targeting a large surface of the receptor binding motif shows

pan-neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 activity. Nat Commun.

15(1051)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Onodera T, Kita S, Adachi Y, Moriyama S,

Sato A, Nomura T, Sakakibara S, Inoue T, Tadokoro T, Anraku Y, et

al: A SARS-CoV-2 antibody broadly neutralizes SARS-related

coronaviruses and variants by coordinated recognition of a

virus-vulnerable site. Immunity. 54:2385–2398.e10. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Vanhove B, Marot S, So RT, Gaborit B,

Evanno G, Malet I, Lafrogne G, Mevel E, Ciron C, Royer PJ, et al:

XAV-19, a swine glyco-humanized polyclonal antibody against

SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain, targets multiple epitopes

and broadly neutralizes variants. Front Immunol.

12(761250)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Fu D, Zhang G, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Hu H, Shen

S, Wu J, Li B, Li X, Fang Y, et al: Structural basis for SARS-CoV-2

neutralizing antibodies with novel binding epitopes. PLoS Biol.

19(e3001209)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Hansen J, Baum A, Pascal KE, Russo V,

Giordano S, Wloga E, Fulton BO, Yan Y, Koon K, Patel K, et al:

Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a

SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 369:1010–1014.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Wang F, Li L, Dou Y, Shi R, Duan X, Liu H,

Zhang J, Liu D, Wu J, He Y, et al: Etesevimab in combination with

JS026 neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Emerg Microbes

Infect. 11:548–551. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Li F, Xu W, Zhang X, Wang W, Su S, Han P,

Wang H, Xu Y, Li M, Fan L, et al: A spike-targeting bispecific T

cell engager strategy provides dual layer protection against

SARS-CoV-2 infection in vivo. Commun Biol. 6(592)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Casasnovas JM, Margolles Y, Noriega MA,

Guzmán M, Arranz R, Melero R, Casanova M, Corbera JA,

Jiménez-de-Oya N, Gastaminza P, et al: Nanobodies protecting from

lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection target receptor binding epitopes

preserved in virus variants other than omicron. Front Immunol.

13(863831)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Chi H, Wang L, Liu C, Cheng X, Zheng H, Lv

L, Tan Y, Zhang N, Zhao S, Wu M, et al: An engineered IgG-VHH

bispecific antibody against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants. Small

Methods. 6(e2200932)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Titong A, Gallolu Kankanamalage S, Dong J,

Huang B, Spadoni N, Wang B, Wright M, Pham KLJ, Le AH and Liu Y:

First-in-class trispecific VHH-Fc based antibody with potent

prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 and

variants. Sci Rep. 12(4163)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Yang Z, Wang Y, Jin Y, Zhu Y, Wu Y, Li C,

Kong Y, Song W, Tian X, Zhan W, et al: A non-ACE2 competing human

single-domain antibody confers broad neutralization against

SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

6(378)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Luo S, Zhang J, Kreutzberger AJB, Eaton A,

Edwards RJ, Jing C, Dai HQ, Sempowski GD, Cronin K, Parks R, et al:

An antibody from single human VH-rearranging mouse

neutralizes all SARS-CoV-2 variants through BA.5 by inhibiting

membrane fusion. Sci Immunol. 7(eadd5446)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Geng J, Chen L, Yuan Y, Wang K, Wang Y,

Qin C, Wu G, Chen R, Zhang Z, Wei D, et al: CD147 antibody

specifically and effectively inhibits infection and cytokine storm

of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants delta, alpha, beta, and gamma.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6(347)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Tai W, Feng S, Chai B, Lu S, Zhao G, Chen

D, Yu W, Ren L, Shi H, Lu J, et al: An mRNA-based T-cell-inducing

antigen strengthens COVID-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Nat Commun. 14(2962)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Freitag TL, Fagerlund R, Karam NL,

Leppänen VM, Ugurlu H, Kant R, Mäkinen P, Tawfek A, Jha SK,

Strandin T, et al: Intranasal administration of adenoviral vaccines

expressing SARS-CoV-2 spike protein improves vaccine immunity in

mouse models. Vaccine. 41:3233–3246. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Gu S, Chen Z, Meng X, Liu G, Xu H, Huang

L, Wu L, Gong J, Chen D, Xue B, et al: Spike-based adenovirus

vectored COVID-19 vaccine does not aggravate heart damage after

ischemic injury in mice. Commun Biol. 5(902)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

García-Arriaza J, Garaigorta U, Pérez P,

Lázaro-Frías A, Zamora C, Gastaminza P, Del Fresno C, Casasnovas

JM, Sorzano CÓ S, Sancho D and Esteban M: COVID-19 vaccine

candidates based on modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing the

SARS-CoV-2 spike induce robust T- and B-cell immune responses and

full efficacy in mice. J Virol. 95:e02260–20. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Phoolcharoen W, Shanmugaraj B,

Khorattanakulchai N, Sunyakumthorn P, Pichyangkul S, Taepavarapruk

P, Praserthsee W, Malaivijitnond S, Manopwisedjaroen S,

Thitithanyanont A, et al: Preclinical evaluation of immunogenicity,

efficacy and safety of a recombinant plant-based SARS-CoV-2 RBD

vaccine formulated with 3M-052-Alum adjuvant. Vaccine.

41:2781–2792. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Marlin R, Godot V, Cardinaud S, Galhaut M,

Coleon S, Zurawski S, Dereuddre-Bosquet N, Cavarelli M, Gallouët

AS, Maisonnasse P, et al: Targeting SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding

domain to cells expressing CD40 improves protection to infection in

convalescent macaques. Nat Commun. 12(5215)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Zhang T, Magazine N, McGee MC, Carossino

M, Veggiani G, Kousoulas KG, August A and Huang W: Th2 and

Th17-associated immunopathology following SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough

infection in Spike-vaccinated ACE2-humanized mice. J Med Virol.

96(e29408)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Zhang J, Fang F, Zhang Y, Han X, Wang Y,

Yin Q, Sun K, Zhou H, Qin H, Zhao D, et al: Humanized major

histocompatibility complex transgenic mouse model can play a potent

role in SARS-CoV-2 human leukocyte antigen-restricted T cell

epitope screening. Vaccines (Basel). 13(416)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Weingarten-Gabbay S, Klaeger S, Sarkizova

S, Pearlman LR, Chen DY, Gallagher KME, Bauer MR, Taylor HB, Dunn

WA, Tarr C, et al: Profiling SARS-CoV-2 HLA-I peptidome reveals T

cell epitopes from out-of-frame ORFs. Cell. 184:3962–3980.e17.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Zayou L, Prakash S, Vahed H, Dhanushkodi

NR, Quadiri A, Belmouden A, Lemkhente Z, Chentoufi A, Gil D, Ulmer

JB and BenMohamed L: Dynamics of spike-specific neutralizing

antibodies across five-year emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern

reveal conserved epitopes that protect against severe COVID-19.

Front Immunol. 16(1503954)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Klein J, Wood J, Jaycox JR, Dhodapkar RM,

Lu P, Gehlhausen JR, Tabachnikova A, Greene K, Tabacof L, Malik AA,

et al: Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through

immune profiling. Nature. 623:139–148. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Cui L, Fang Z, De Souza CM, Lerbs T, Guan

Y, Li I, Charu V, Chen SY, Weissman I and Wernig G: Innate immune

cell activation causes lung fibrosis in a humanized model of long

COVID. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 120(e2217199120)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Heath SP, Hermanns VC, Coucha M and

Abdelsaid M: SARS-CoV-2 spike protein exacerbates thromboembolic

cerebrovascular complications in humanized ACE2 mouse model. Transl

Stroke Res. 16:1214–1228. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Burnett FN, Coucha M, Bolduc DR, Hermanns

VC, Heath SP, Abdelghani M, Macias-Moriarity LZ and Abdelsaid M:

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein intensifies cerebrovascular complications

in diabetic hACE2 Mice through RAAS and TLR signaling activation.

Int J Mol Sci. 24(16394)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Haudenschild AK, Christiansen BA, Orr S,

Ball EE, Weiss CM, Liu H, Fyhrie DP, Yik JHN, Coffey LL and

Haudenschild DR: Acute bone loss following SARS-CoV-2 infection in

mice. J Orthop Res. 41:1945–1952. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Upadhyay V, Suryawanshi RK, Tasoff P,

McCavitt-Malvido M, Kumar RG, Murray VW, Noecker C, Bisanz JE,

Hswen Y, Ha CWY, et al: Mild SARS-CoV-2 infection results in

long-lasting microbiota instability. mBio.

14(e0088923)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Edwinson A, Yang L, Chen J and Grover M:

Colonic expression of Ace2, the SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor, is

suppressed by commensal human microbiota. Gut Microbes.

13(1984105)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Zhu H, Sharma AK, Aguilar K, Boghani F,

Sarcan S, George M, Ramesh J, Van Der Eerden J, Panda CS, Lopez A,

et al: Simple virus-free mouse models of COVID-19 pathologies and

oral therapeutic intervention. iScience. 27(109191)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Pujhari S and Rasgon JL: Mice with

humanized-lungs and immune system-an idealized model for COVID-19

and other respiratory illness. Virulence. 11:486–488.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Lamers MM, van der Vaart J, Knoops K,

Riesebosch S, Breugem TI, Mykytyn AZ, Beumer J, Schipper D,

Bezstarosti K, Koopman CD, et al: An organoid-derived

bronchioalveolar model for SARS-CoV-2 infection of human alveolar

type II-like cells. EMBO J. 40(e105912)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Ahmadipour M, Prado JC, Hakak-Zargar B,

Mahmood MQ and Rogers IM: Using ex vivo bioengineered lungs to

model pathologies and screening therapeutics: A proof-of-concept

study. Biotechnol Bioeng. 121:3020–3033. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Parker MFL, Blecha J, Rosenberg O, Ohliger

M, Flavell RR and Wilson DM: Cyclic 68Ga-labeled

peptides for specific detection of human angiotensin-converting

enzyme 2. J Nucl Med. 62:1631–1637. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Li D, Xiong L, Pan G, Wang T, Li R, Zhu L,

Tong Q, Yang Q, Peng Y, Zuo C, et al: Molecular imaging on

ACE2-dependent transocular infection of coronavirus. J Med Virol.

94:4878–4889. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|