Introduction

Transplantation of autogenous or allogenous

chondrocytes has been used to repair defective cartilage. However,

the limited sources for a sufficient number of chondrocytes

restricts the development and clinical application of

chondrocyte-based therapies (1).

Therefore, finding an effective method to collect ‘target cells’ is

crucial.

Increasing evidence has shown that an extract

harvested from one type of differentiated somatic cell is capable

of altering another cell phenotype in vitro, a method of

reprogramming that has developed in recent years (2–5).

This method was first introduced by Hakelien et al (2). Those authors found that 293T cells

permeabilized with streptolysin O (SLO) exposed to a T-cell extract

were capable of adopting T cell-specific properties, such as

expressing T cell-specific receptors and assembling the

interleukin-2 receptor. Supported by a number of studies, use of

this method suggests that altering cell fate using cell extract is

feasible and effective, and may be applied to multiple cell

types.

The most common cells used as ‘donor cells’, which

receive another cell extract and differentiate into ‘target cells’,

are fibroblasts and adult stem cells, as they can be harvested

easily and exhibit marked proliferative capacity. Compared with

fibroblasts, adult stem cells have a broad prospect of application

as a result of their potential of multi-directional differentiation

into cells including adipocytes, osteoblasts and chondrocytes in

response to lineage-specific induction factors (6,7).

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs), widely used

in regenerative medicine, have also been successfully induced into

chondrocytes by the induction of growth factors (8,9),

co-culturing with chondrocytes (10,11)

or low-intensity ultrasound (12).

The aim of this study was to observe whether

chondrocyte extract induced the differentiation of BM-MSCs into

chondrocytes in a monolayer culture. Moreover, we investigated

whether the maintenance time of phenotypic alteration could be

prolonged and whether cells were able to produce cartilage-specific

extracellular matrix (ECM) components when cultured at a high

density.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal procedures in this study were approved by

Shanghai Jiaotong University Medical Center, Institutional Animal

Care and Use Committee. The animals were maintained in a specific

pathogen-free environment. The surgical procedures were performed

under aseptic conditions.

BM-MSC preparation

Swine bone marrow was obtained from the posterior

superior iliac crest of newborn pigs. Briefly, after washing twice

in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY,

USA) to remove red cell fragments, cells were resuspended in

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) with low glucose

plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and plated in 100

mm2 culture dishes at a density of 2.0×105

cells/cm2 at 37°C with 5% CO2. Non-adherent

cells were removed by medium change after 5 days. The adherent

cells were collected when >80% confluence was achieved and then

subcultured. BM-MSCs at passage 2 were used for subsequent

experiments.

Chondrocyte isolation and culture

The swine articular cartilage was cut into 2×2 mm

slices and washed twice with PBS. After being digested with 0.25%

trypsin plus 0.02% EDTA at 37°C for 30 min, the cartilage slices

were further digested with 0.1% collagenase II in serum-free DMEM

at 37°C for 12–16 h. Chondrocytes were then harvested, counted and

seeded into culture dishes at a cell density of

2.5×104/cm2 for the culture and subculture in

DMEM with high glucose and 10% FBS. Chondrocytes at passage 1 were

used in this study.

Chondrocyte extract

After being harvested, chondrocytes at passage 1

were washed in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hank’s

balanced salt solution (HBSS, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) twice and

cell lysis buffer (100 mM HEPES, pH 8.2, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM

MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol and protease inhibitors),

sedimented at 1,000 rpm, resuspended in 0.8 ml cold cell lysis

buffer and incubated for 50 min on ice. Cells were sonicated on ice

in 200 μl aliquots using a sonicator fitted with a 3-mm diameter

probe until the cells and nuclei were lysed, as judged by

microscopy. The lysate was sedimented at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at

4°C to pellet the coarse material. The supernatant was aliquoted,

frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The protein

concentration of the extract was determined by the Bradford assay.

In this study, the chondrocyte extract contained 10–15 mg/ml

protein.

Streptolysin O-mediated permeabilization

and cell extract treatment

BM-MSCs were washed in cold PBS and in cold HBSS.

Cells were resuspended in SLO solution at a concentration of 100

cells/μl with a SLO concentration of 230 ng/ml. Samples were

incubated in an H2O bath for 50 min at 37°C with

occasional agitation. Cells were then collected by sedimentation at

1,800 rpm for 5 min at 37°C. A permeabilization efficiency of

>60% was obtained, as assessed by monitoring the uptake of

propidium iodide (PI).

Following permeabilization, cells were resuspended

at 1000 cells/μl in 100 μl cell extract containing an ATP-

regenerating system and 1 mmol/l of each NTP. Cells were cultured

for 1 h at 37°C with occasional agitation. To reseal the cells,

cell suspension with cell extract was diluted with DMEM containing

2 mM CaCl2 and cultured for 2 h at 37°C. The supernatant

was discarded, fresh DMEM containing no CaCl2 was added

and cells were cultured until use. According to the different

treatments, there were 4 groups: SLO treatment(+) cell extract(+)

group; SLO treatment(−) cell extract(+) group; SLO treatment(−)

cell extract(−) group; and chondrocyte group, which was regarded as

a positive control.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed on the

seventh day. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15

min. The fixed specimens were washed and incubated with primary

anti-collagen type II (COL II) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted in 0.5% bovine serum

albumin (BSA) at 4°C overnight and then washed and incubated with

secondary antibody for 30 min at 37°C. DAPI was used as a nuclear

counterstain. Images were captured on a NIKON microscope using IPP

software.

Transcription analysis

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

(RT-PCR) was performed on the seventh day using the primers: COL

II: forward (5′-3′): GATGGGCAGAGGTATAATGAT and reverse (5′-3′):

CTTTTTCACCTTTGTCACCAC (product size, 322 bp); aggrecan: forward

(5′-3′): ATGACTCTGGGATCTATCGCT and reverse (5′-3′):

CGTAGGTCTCATTGGTGTCA-3 (product size, 352 bp); GADPH: forward

(5′-3′): ACATCAAGGAGAAGCTCTGCTACG and reverse (5′-3′):

GAGGGGCGATGATCTTGATCTTCA (product size, 366 bp). The reactions were

performed in a T3 thermocycler (Biometra, Goettingen, Germany). The

amplified products were separated on 1.5% agarose gels and

visualized by ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich).

Chondrogenic differentiation of

treated-BM-MSCs in micromass culture

Based on the results obtained above, micromass

culture was performed. Briefly, reversibly permeabilized BM-MSCs

with added cell extract were collected by resuspension at a density

of 2.0×107 cells/ml in the growth medium. The cell

suspension was then spotted in 15 μl drops into dishes. The cells

were incubated for 2 h at 37°C to allow attachment and then

maintained in the complete medium until day 14. The specimens were

then embedded in paraffin and cut into 10 μm sections. The sections

were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and toluidine

blue to reveal the histological structure and chondroitin sulfate

deposition, which is a substance in cartilage matrix, respectively.

The expression of COL II was detected using mouse anti-pig

monoclonal antibody (1:100 in 0.5% BSA, Santa Cruz Biotechnology),

followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse

antibody (1:500 in PBS, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and color

development with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB, Santa

Cruz Biotechnology).

Results

Reversible permeabilization of

BM-MSCs

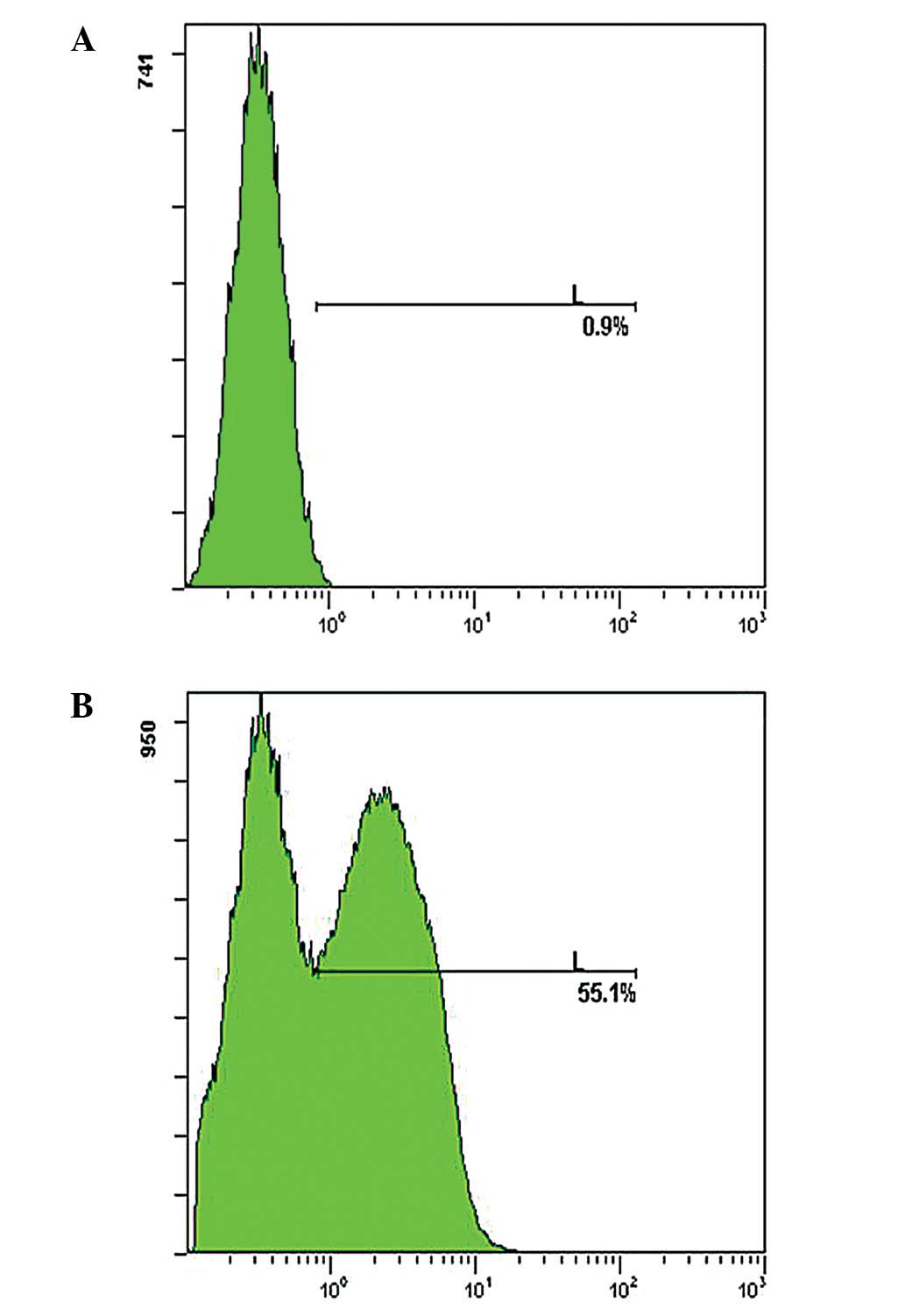

In this study, BM-MSCs were treated with various

concentrations of SLO (230, 300 and 400 ng/ml, respectively) and

the proliferative ability of cells was detected. Results showed

that an enhanced SLO concentration slightly increased

permeabilization, however, a marked decrease was observed in the

proliferative ability of cells (data not shown). SLO (230 ng/ml)

was used, as a permeabilization efficiency of >55% was obtained

and it was proven to be least detrimental (Fig. 1).

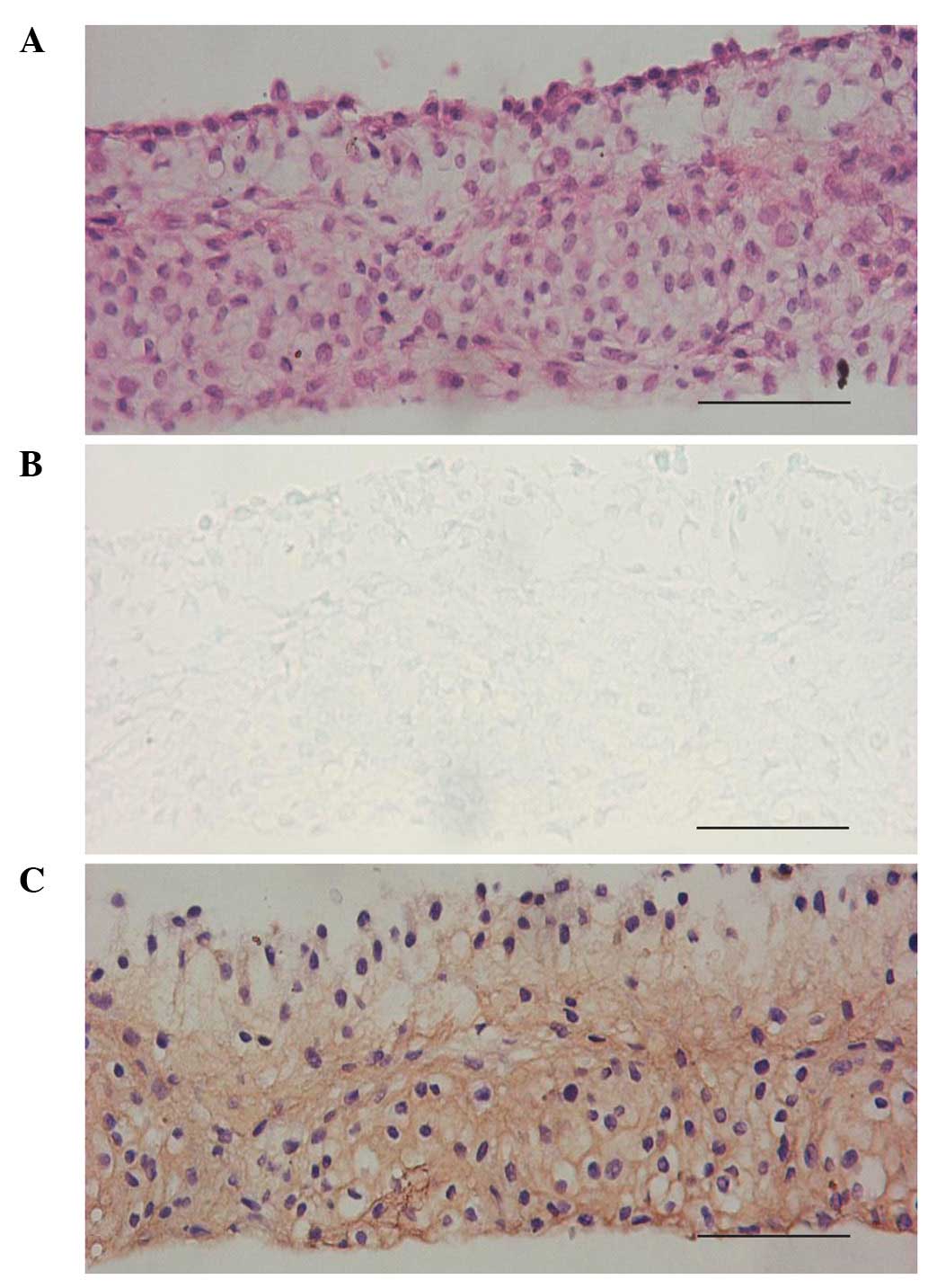

Exposure of BM-MSCs to the chondrocyte

extract leads to the induction of chondrocyte-specific genes and

protein

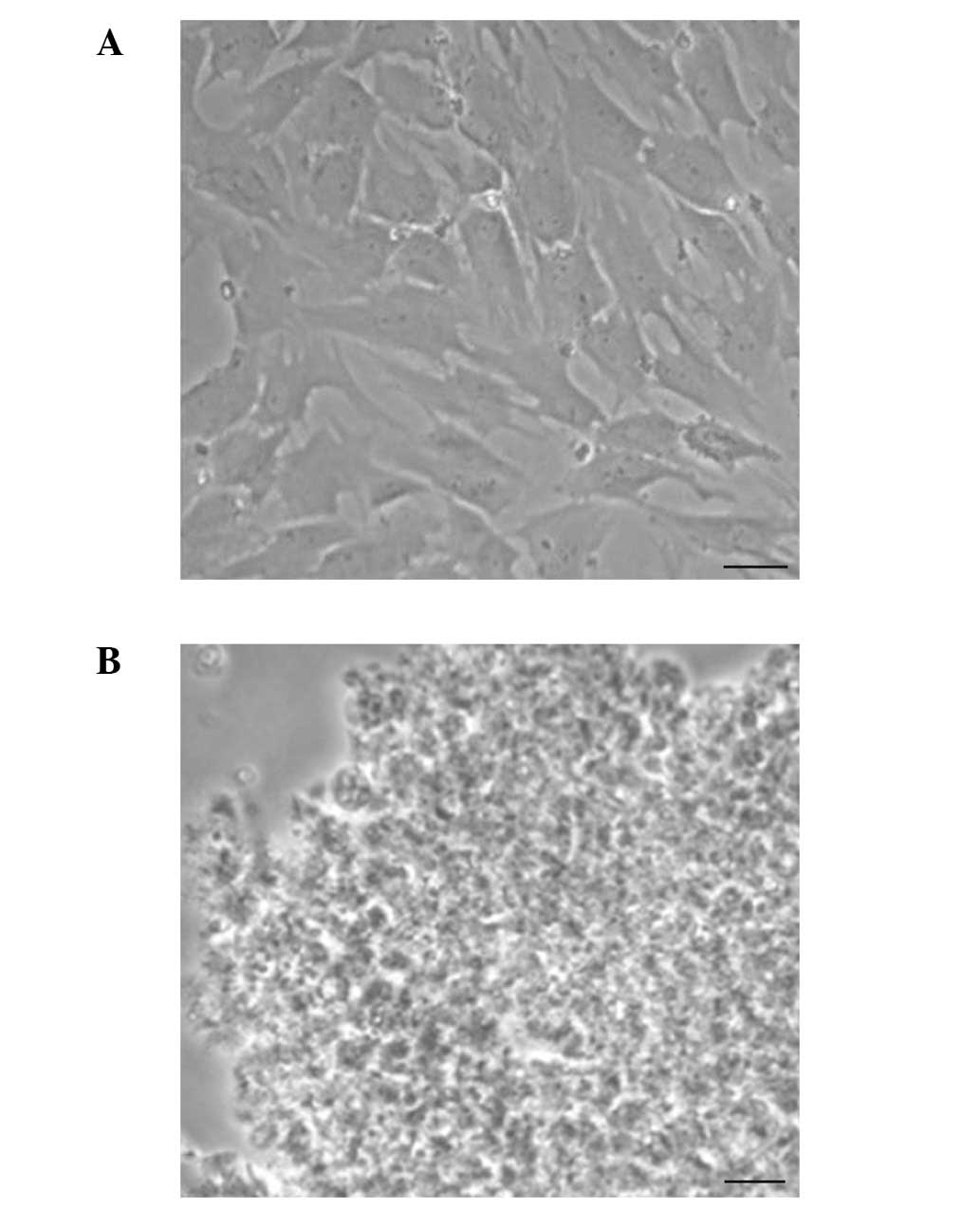

Chondrocytes were sonicated and observed under a

microscope, which revealed that there was no cell and nucleus

structure (Fig. 2). Consistent

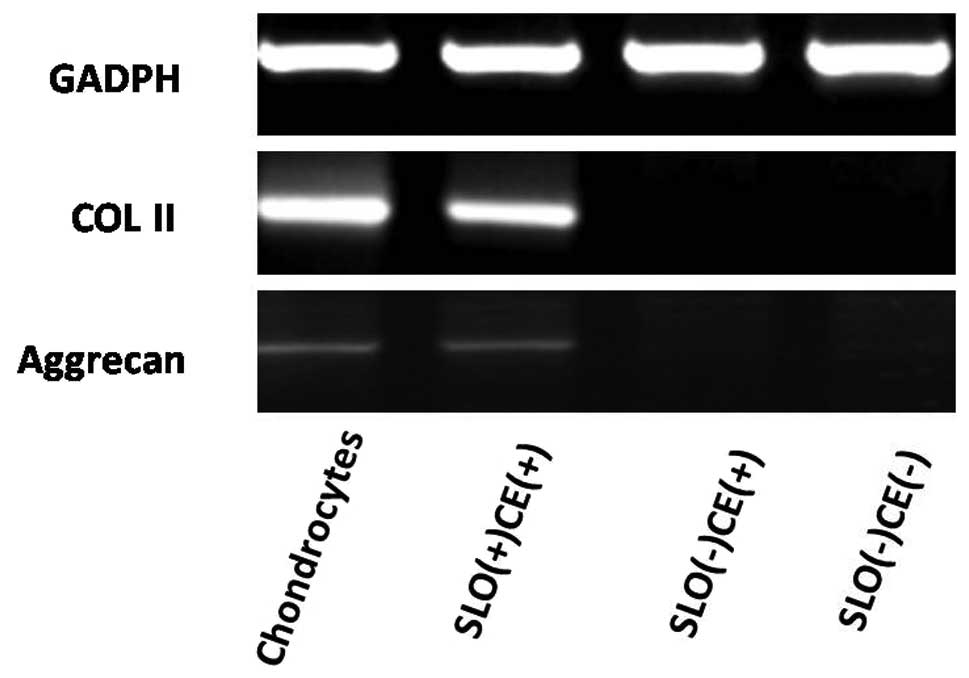

with the uptake of PI, following exposure of BM-MSCs to the

chondrocyte extract in an ATP-regeneration 7 days later, cells

treated with SLO-expressed chondrocyte-specific genes such as COL

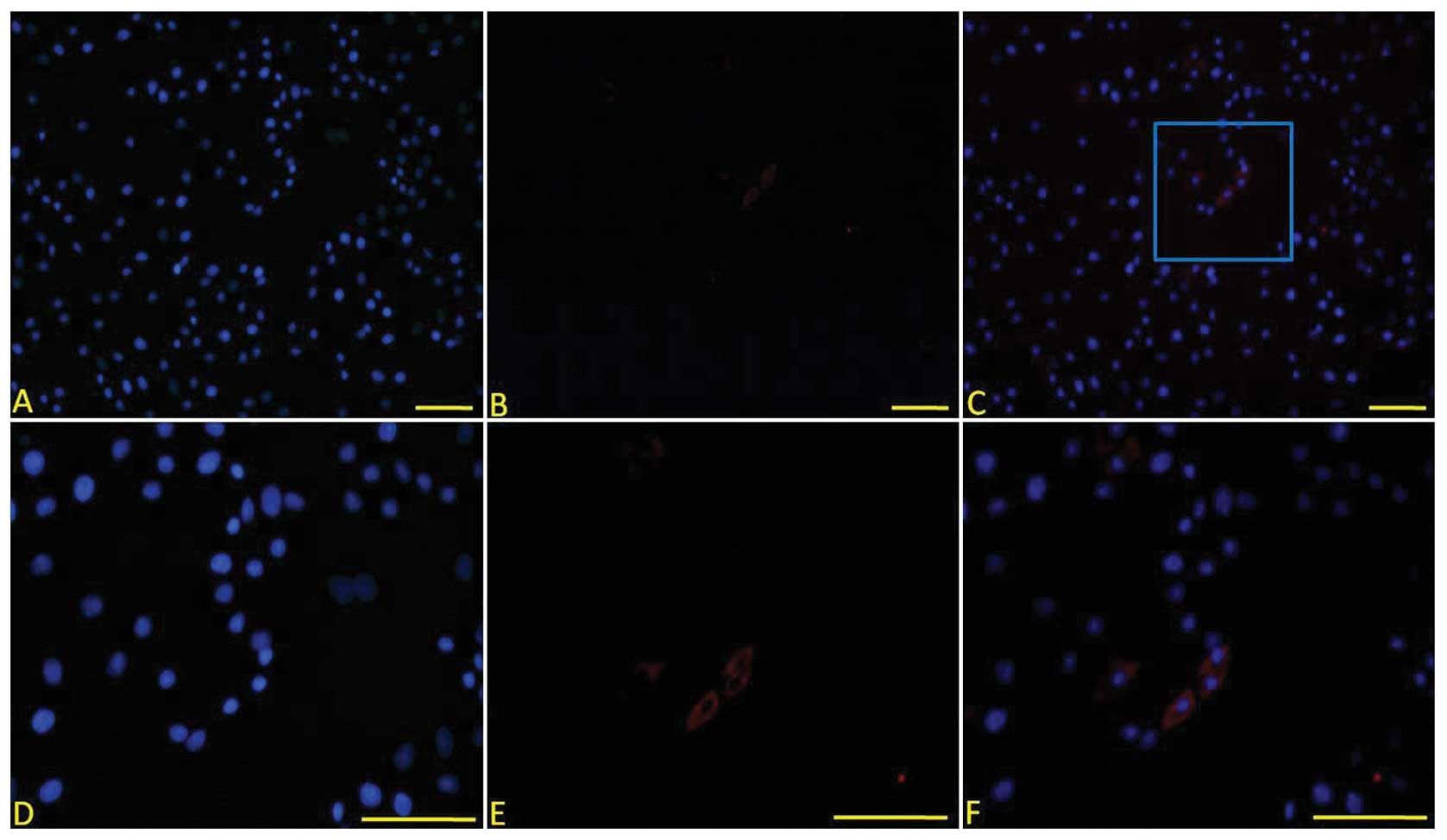

II and aggrecan on the seventh day (Fig. 3). The immunofluorescent staining

revealed that reprogrammed BM-MSCs were positive for COL II

(Fig. 4); whereas, no changes were

observed in intact (non-permeabilized) BM-MSCs. However, at 14

days, there was no relevant expression.

| Figure 4COL II expression in the cells 7 days

after cell treatment. COL II was positive in the cells treated with

SLO and the cell extract. (A) DAPI staining, (B) anti-COL II

immunofluorescent staining, (C) merged image of A and B revealed

that some cells expressed COL II, (D) high magnification of DAPI

staining of positive cells in the blue frame in (C), (E) high

magnification of anti-COL II immunofluorescent staining of positive

cells in the blue frame in (C) and (F) merged image of (D) and (E)

(original magnification: A–C, ×100, D–E, ×200). COL II, type II

collagen, SLO, streptolysin O. |

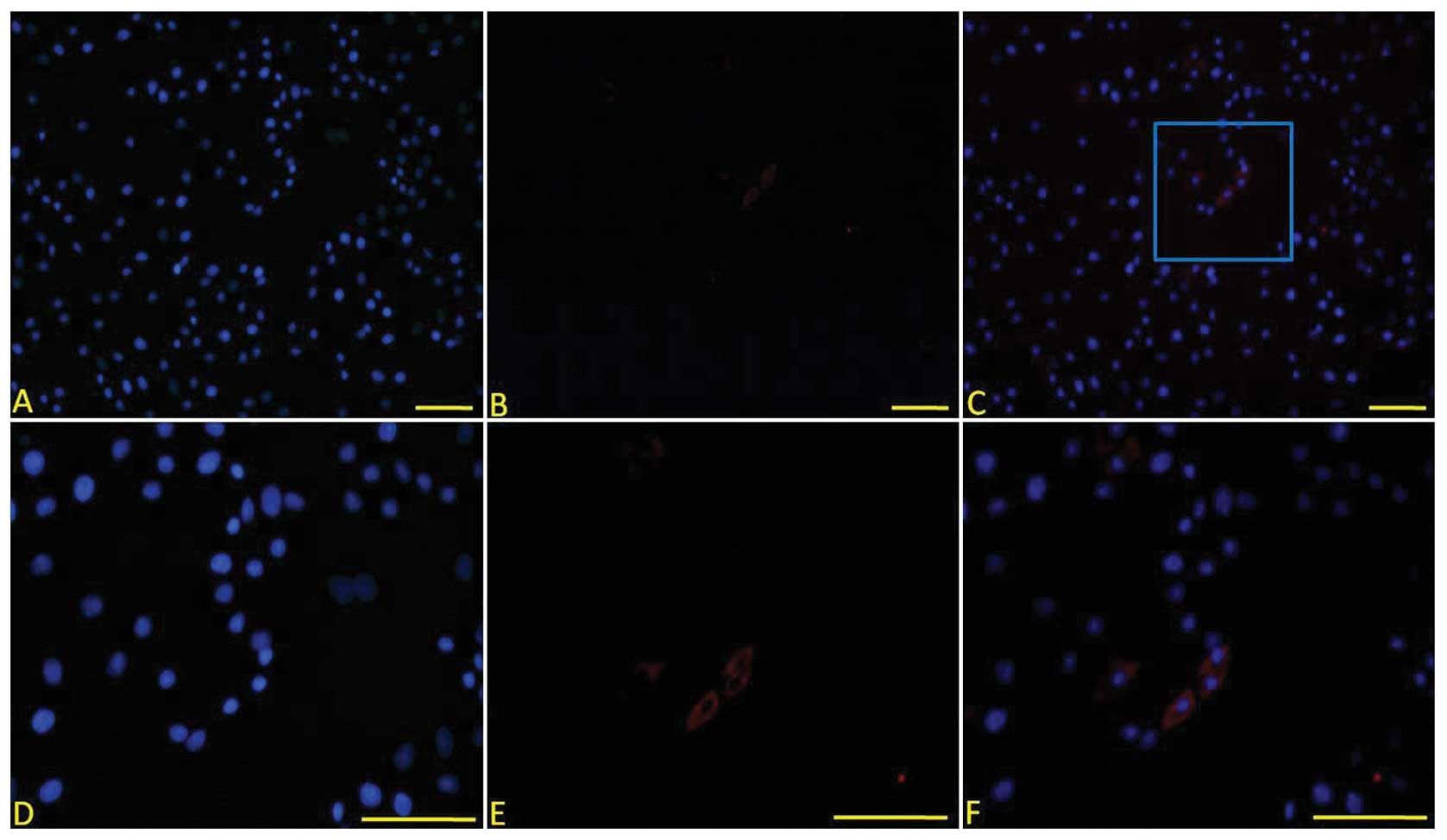

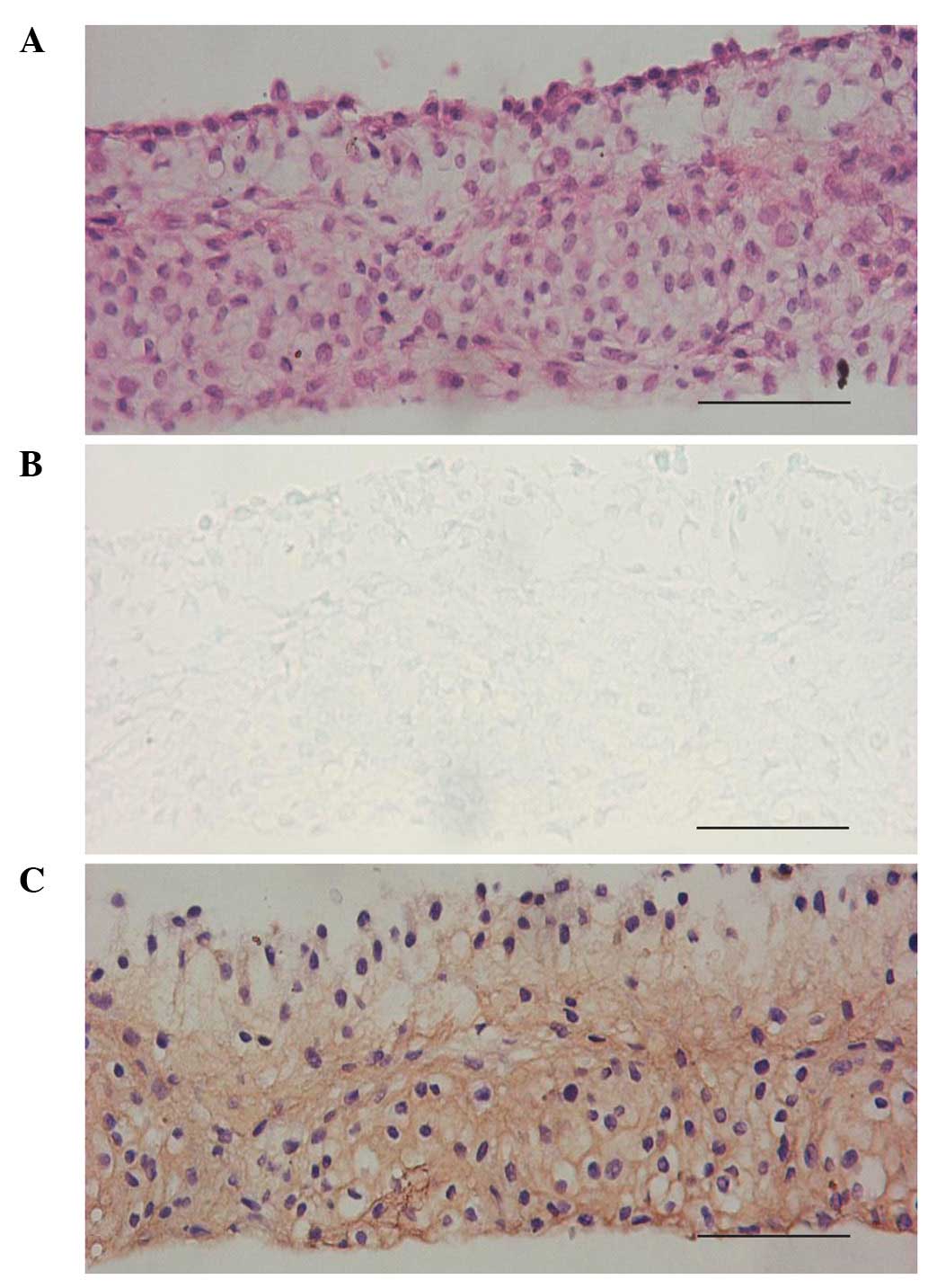

Maintenance of the chondrogenic phenotype

of reprogrammed BM-MSCs in micromass culture

Previous investigations have demonstrated that a

high density culture manner, such as micromass or pellet culture,

is essential for the chondrogenic differentiation of BM-MSCs. Using

monolayer culture, examinations could not detect relevant

chondrocyte-specific expression 14 days after cell treatment. Thus,

to maintain the chondrogenic differentiation of reprogrammed

BM-MSCs, micromass culture was used in this study. When the

induction time was extended to 14 days, the cells in the cell mass

formed a lacunae structure with chondrocyte-like cells located

inside secreting chondroitin sulfate. The expression of COL II was

also observed in the cell mass (Fig.

5).

| Figure 5Histological morphology of

chondrogenically transdifferentiated BM-MSCs cultured in micromass

in the presence of SLO and chondrocyte extract simultaneously on

the 14th day. (A) H&E staining showed that certain cells in the

micromass formed lacunae structure, (B) toluidine blue staining

indicated that certain cells secreted chondroitin sulfate, (C)

anti-COL II immunohistochemical staining was positive in the cell

mass (original magnification, ×200). BM-MSCs, bone marrow-derived

mesenchymal stem cells, SLO, streptolysin O, COL II, type II

collagen, H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. |

Discussion

Cell extract-based systems for reprogramming cell

fate have been developed with the aim of eliciting somatic cell

transdifferentiation or dedifferentiation. Previous studies have

demonstrated that cell extracts harvested from embryonic stem cells

(ESCs) (13) or somatic cells

(3) are capable of inducing

nuclear de-/transdifferentiation of ‘donor cells’. The current

study provided permeabilized BM-MSCs with the chondrocyte extract

and observed changes in the gene and protein expression following

cell culture. A high-density culture method was also found to

prolong the maintenance time of the phenotype change of

reprogrammed cells.

The main component of the cell extract was thought

to be protein, as heat-treated (95°C, 5 min) extracts were not able

to induce any changes (3,5). In this study, the cell extract was

obtained using cell lysis and ultrasonic homogenization. By this

method, the protein molecular weight varies within a wide range. To

enable the cell extract to enter ‘donor cells’ effectively, BM-MSCs

were treated with SLO as described previously (2,3).

Following the binding of SLO to membranes, toxin monomers diffuse

laterally in the bilayer and oligomerize to form homotypic

aggregates that represent large transmembrane pores whose diameters

may reach 35 nm, allowing molecules <100 kDa to enter the cell

cytosol (14–16). In the presence of Ca2+,

the permeabilized cells were resealed for subsequent culture. This

finding was consistent with other authors who reported that

resealing was temperature-independent and even occurred eat 4°C

(14).

Findings of previous studies have shown that a rapid

gene change may be induced over a 1–8 h culture (17) and that these genes would

consistently persist up to days 7–10 (3,18).

In our study, no gene alteration was evident on day 3. However, 7

days later, a clear expression of COL II and aggrecan, the two main

chondrogenic gene markers, was demonstrated by RT-PCR analysis in

the group of permeabilized BM-MSCs in the presence of the cell

extract. Consistent with gene change, COL II protein expression was

also positive in this group. These results suggested that exposure

to the chondrocyte extract initiated a series of changes driving

BM-MSCs cultured in a monolayer towards chondrocyte-like cells 7

days after treatment. No changes were observed in intact

(non-permeabilized) BM-MSCs incubated in chondrocyte extract. These

results are consistent with those of Taranger et al

(19) and Bru et al

(17), but not with those by

Hansis et al (20).

However, no changes were detected on day 14. In addition to this

finding, the percentage of permeabilized cells in this study was

over 55% and was discrepant with COL II-positive cells. There are

various reasons for this finding: i) A low concentration of cell

extract leads to incomplete transdifferentiation; ii) preferential

growth of BM-MSCs inhibits the proliferation of successfully

reprogrammed BM-MSCs; iii) the culturing method makes the

chondrogenic microenvironment deficient and iv) the changes were

transient and could not be detected at the 14th day.

Considering the fact that chondroadherin interaction

with cells may be crucial for maintaining the adult chondrocyte

phenotype and cartilage homeostasis, cell-cell contact may be

responsible for the reprogramming (21). Fourteen days after micromass

culture, the cells presented a crumb structure. H&E staining

showed cells in the crumb presenting lacunae structure with

chondroitin sulfate and were COL II-positive. This suggests that

cytokines secreted by BM-MSC-converted chondrocytes are likely to

constantly induce BM-MSCs towards chondrocytes.

The main regulatory component involved in the cell

extract was believed to initiate a transcriptional program specific

for the alteration (3). Hakelien

et al (2) observed the

import of transcription factors into 293T nuclei in their study. At

the same time, demethylation of the target cell-specific gene

promoter and histone acetylation were also observed (3,5,13,17).

Cell reprogramming is of interest for the

development of novel cellular therapeutics and is potentially

useful for producing isogenic replacement cells for the treatment

of a wide variety of diseases. The incomplete transcriptional and

epigenetic reprogramming may not lead the cells harvested in this

manner to be totally the same as the ‘target’ cells, but own some

of the desired functions of the ‘target’ cells. To a certain

degree, it is sufficient for cell programming to exhibit the

necessary therapeutic properties without complete alteration of

genes, protein and functions. For example, rat fibroblasts

reversibly permeabilized with SLO and exposed to extract of an

insulin-producing β cell line were capable of secreting insulin on

day 5 (3). For diabetes care, it

is sufficient to harvest cells able to secrete insulin.

Since only this alteration is detectable, it

indicates a limitation of our study. Thus, the relevant mechanism

involved in this process and the methods of increasing efficiency

and the maintenance time of reprogramming should be

investigated.

In conclusion, this study has shown that reversibly

permeabilized BM-MSCs were differentiated into chondrocytes when

they were co-cultured with the chondrocyte extract. SLO plays a key

role, but not dependently, in the reprogramming process and it sets

the stage for the further action of more essential components in

the cell extract. Nevertheless, culturing cells with a high-density

protocol is likely to prolong the phenotypic changes of

differentiated cells. The method used in this study provides tissue

engineering with a novel way of obtaining seeding cells.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (Nos. 30900308 and 81071580).

References

|

1

|

Wong CC, Chiu LH, Lai WF, et al:

Phenotypic re-expression of near quiescent chondrocytes: The

effects of type II collagen and growth factors. J Biomater Appl.

25:75–95. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hakelien AM, Landsverk HB, Robl JM,

Skalhegg BS and Collas P: Reprogramming fibroblasts to express

T-cell functions using cell extracts. Nat Biotechnol. 20:460–466.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hakelien AM, Gaustad KG and Collas P:

Transient alteration of cell fate using a nuclear and cytoplasmic

extract of an insulinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

316:834–841. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gaustad KG, Boquest AC, Anderson BE,

Gerdes AM and Collas P: Differentiation of human adipose tissue

stem cells using extracts of rat cardiomyocytes. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 314:420–427. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Miyamoto K, Furusawa T, Ohnuki M, et al:

Reprogramming events of mammalian somatic cells induced by

Xenopus laevis egg extracts. Mol Reprod Dev. 74:1268–1277.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wu Y, Chen L, Scott PG and Tredget EE:

Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through

differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 25:2648–2659. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li H, Zan T, Li Y, et al: Transplantation

of adipose-derived stem cells promotes formation of prefabricated

flap in a rat model. Tohoku J Exp Med. 222:131–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al:

Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells.

Science. 284:143–147. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Indrawattana N, Chen G, Tadokoro M, et al:

Growth factor combination for chondrogenic induction from human

mesenchymal stem cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 320:914–919.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Thompson AD, Betz MW, Yoon DM and Fisher

JP: Osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells induced

by coculture with chondrocytes encapsulated in three-dimensional

matrices. Tissue Eng Part A. 15:1181–1190. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Liu X, Sun H, Yan D, et al: In vivo

ectopic chondrogenesis of BMSCs directed by mature chondrocytes.

Biomaterials. 31:9406–9414. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lee HJ, Choi BH, Min BH, Son YS and Park

SR: Low-intensity ultrasound stimulation enhances chondrogenic

differentiation in alginate culture of mesenchymal stem cells.

Artif Organs. 30:707–715. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rajasingh J, Lambers E, Hamada H, et al:

Cell-free embryonic stem cell extract-mediated derivation of

multipotent stem cells from NIH3T3 fibroblasts for functional and

anatomical ischemic tissue repair. Circ Res. 102:e107–e117. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Walev I, Bhakdi SC, Hofmann F, et al:

Delivery of proteins into living cells by reversible membrane

permeabilization with streptolysin-O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

98:3185–3190. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Palmer M, Vulicevic I, Saweljew P, Valeva

A, Kehoe M and Bhakdi S: Streptolysin O: a proposed model of

allosteric interaction between a pore-forming protein and its

target lipid bilayer. Biochemistry. 37:2378–2383. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Palmer M, Harris R, Freytag C, Kehoe M,

Tranum-Jensen J and Bhakdi S: Assembly mechanism of the oligomeric

streptolysin O pore: the early membrane lesion is lined by a free

edge of the lipid membrane and is extended gradually during

oligomerization. EMBO J. 17:1598–1605. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Bru T, Clarke C, McGrew MJ, Sang HM,

Wilmut I and Blow JJ: Rapid induction of pluripotency genes after

exposure of human somatic cells to mouse ES cell extracts. Exp Cell

Res. 314:2634–2642. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Miyamoto K, Tsukiyama T, Yang Y, et al:

Cell-free extracts from mammalian oocytes partially induce nuclear

reprogramming in somatic cells. Biol Reprod. 80:935–943. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Taranger CK, Noer A, Sorensen AL, Hakelien

AM, Boquest AC and Collas P: Induction of dedifferentiation,

genomewide transcriptional programming, and epigenetic

reprogramming by extracts of carcinoma and embryonic stem cells.

Mol Biol Cell. 16:5719–5735. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hansis C, Barreto G, Maltry N and Niehrs

C: Nuclear reprogramming of human somatic cells by Xenopus

egg extract requires BRG1. Curr Biol. 14:1475–1480. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yin S, Cen L, Wang C, et al: Chondrogenic

transdifferentiation of human dermal fibroblasts stimulated with

cartilage-derived morphogenetic protein 1. Tissue Eng Part A.

16:1633–1643. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|