Introduction

Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF) is a

clinically significant angiogenic agent used for its potent

function in angiogenesis in the treatment of numerous ischemic

diseases, including coronary heart disease as well as chronic wound

and diabetic lower limb ischemias (1,2).

However, VEGF has restricted clinical application due to its short

half-life and the potential side effects of an overdose, which

include edema, inflammation, hemorrhage, hypotension and hemangioma

(3–5). Therefore, the identification or

design of a novel endothelial cell-specific proangiogenic factor

with fewer side effects is required.

A previous study generated a chimeric VEGF called

VEGF192 (according to the nomenclature of VEGF) from the fusion of

the VEGF183 (132–158, KDRARQENKSVRGK GKGQKRKRKKSR) peptide to the

COOH-terminus of the plasmin-resistant VEGF165 (6). The peptide corresponded to the amino

acid sequence 132–158 of VEGF183 following the cleavage signal

sequence and contained the plasmin and matrix metalloproteinase

(MMP) cleavage sites, as well as extracellular matrix (ECM) binding

sequences (7). The study reported

that the VEGF192 chimeric proteins demonstrated a stronger affinity

for the ECM in a hypoxic environment, enabling them to be cleaved

by MMPs and plasmin, and therefore retain their mitogenic activity

for endothelial cells. In addition, it was reported that VEGF192

reduced vascular permeability and had an increased half-life in

vivo compared to that of VEGF165 (6). Furthermore, Tammela et al

reported that modifying VEGF isoforms through the addition of novel

domains may result in ‘designer’ VEGFs with different bioactivities

from those of the parent molecules (8,9).

In the majority of cases mutant or cleaved VEGFs

demonstrate altered angiogenic activities and vascular patterning

than those of the parental molecules (9). Keskitalo et al (10)generated a chimeric VEGF/VEGF-C silk

domain fusion protein, which resulted in a chimeric VEGF-CAC

protein that significantly enhanced capillary formation compared to

that of the VEGF parent molecules (10). In addition, Tammela et al

(8) constructed a chimeric protein

composed of VEGF-C/VEGF heparin-binding domain fusion proteins,

which was reported to stimulate distinct structural changes to

lymphatic vessels. Zheng et al (11) designed a chimeric VEGF-E

(NZ7)/placental growth factor fusion protein that was shown to be

capable of promoting angiogenesis via VEGFR-2 without significant

enhancement of vascular permeability and inflammation. Lee et

al (12) suggested that

matrix-bound or non-tethered VEGF provided different signaling and

vascular patterning activities compared to those of the parent

molecules. The present study hypothesized that due to the enhanced

binding affinity of VEGF192 to ECM, it may induce differential

vascular patterning compared with that of VEGF165.

The aim of the present study was to explore the

biological effects of VEGF192 in vivo. Murine breast cancer

EMT-6 cells were manipulated to stably overexpress VEGF165 or

VEGF192. These cells were then inoculated intradermally into BALB/c

mice in order to monitor the formation of vascular patterning in

the skin proximal to tumors.

Materials and methods

Experimental procedures were approved by and all

animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the current

regulations and standards of the Animal Ethics Study Committee of

Xinxiang Medical University (Xinxiang, China).

Cell lines and animals

The EMT-6 murine breast cancer cell line was

purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA,

USA) and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM;

HyClone™; Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin and

100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Female

BALB/c mice (Experimental Animal Center of Henan Province,

Zhengzhou, China), aged six to eight weeks, were used for all

experiments. Female BALB/c mice were raised in a specific

pathogen-free environment throughout the experiment with a constant

room temperature of 20–25°C and constant humidity of 35–40% with a

12-h light-dark cycle and were given free access to food and

water.

Constructs

The full-length recombinant human VEGF165 was

provided by Dr Liu Jingjing (minigene lab of China Pharmaceutical

University, Nanjing, China). The VEGF165 mutant resistant to

plasmin proteolysis was generated as described by Lauer et

al (13). Construction of

VEGF192 was performed using polymerase chain reaction

(PCR)-mediated mutagenesis as previously described (7).

The novel VEGF192 and VEGF165 constructs, harboring

their native kozak sequence, were inserted into the mammalian

expression vector pcDNA3.1plus (Invitrogen Life Technologies,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) and further characterized using DNA sequencing

(GENEWIZ, Inc., Suzhou, China).

Stable gene transfection

Endotoxin-free plasmids pcDNA3.1plus-VEGF165,

pcDNA3.1plus-VEGF192 and the control vector pcDNA3.1plus were

extracted using the E.Z.N.A.™ endo-free plasmid midi kit (Omega

Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. Stable transfections of EMT-6 cells were performed

using the Lipofectamine™ 2000 reagent according to manufacturer’s

instructions (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Parental cells were

also transfected using the pcDNA 3.1plus vector (control plasmid).

Transfected cells were incubated in complete growth medium

containing 600 μg/ml G418 antibiotics (Sangon Biotech) for 1–2

weeks.

Stably transfected individual clones were generated

using serial dilutions of G418. G418-resistant clones to be

screened in complete medium plus 600 μg/ml G418, and then stable

transfected individual clones were generated by limited dilutions

maintained in complete growth medium containing 300 μg/ml of

G418.

ELISA screening test for stable clones

overexpressing VEGF isoforms

Levels of human VEGF were quantified in conditioned

medium, prepared as follows: Cells were plated in triplicate at a

density of 2.5×105 cells per well and incubated

overnight in 24-well plates. Cells were then incubated for 48 h in

fresh serum-free medium containing 100 μg/ml heparin (Sangon

Biotech) in order to release cell-associated VEGF. Conditioned

medium was then collected and cellular debris removed using

centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 40°C. A Human VEGF ELISA

kit (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China) was

used to measure human VEGF protein levels in conditioned medium

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was

measured in duplicate.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

quantitative PCR (RT-semi-qPCR)

Confluent EMT-6 cells were cultured in DMEM-10% FBS.

RNA was isolated using TRIzol® reagent according to the

manufacturer’s instructions (Sangon Biotech). Reverse transcription

of 1 μg total RNA was performed using 200 U Superscript II RNase H

reverse transcriptase with oligo deoxy-thymine (dT; Takara Bio,

Inc., Dalian, China).

In order to further semi-quantify the human VEGF

gene in the screened clones, RT-semi-qPCR was performed using the

following primers: Human VEGF forward (NM_001171622.1),

5′-CTTGCTGCTCTACCTCCACC-3′ and VEGF reverse,

5′-GCCTCGGCTTGTCACATCT-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-AGCGAGACCCCACTAACA-3′

and GAPDH reverse, 5′-ATGAGCCCTTCCACAATG-3′. GAPDH was used as the

control.

The complementary DNA (cDNA) samples were mixed with

the above-mentioned primers and amplified using the following

cycling profile: 95°C for 5 min, 26 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec, then

either 57°C for 30 sec (VEGF) or 55°C for 30 sec (GAPDH), followed

by 72°C for 30 sec. The PCR products were visualized using

electrophoresis with 1.5% agarose containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium

bromide solution.

In vivo assay for tumor-adjacent

angiogenesis

A total of 24 eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were

divided randomly into three groups (n=8), anesthetized by

intraperitoneal injection of 3.6% chloral hydrate solution (0.2 ml)

(Sangon Biotech), then shaved on both flanks. Each group was

injected intradermally with a single cell suspension

(2.5×105 cells in 0.1 ml DMEM) of EMT-6 cell clones

overexpressing VEGF192 (V192-N3), EMT-6 cell clones overexpressing

VEGF165 (V165-N6) or the parental cells which carried the

pcDNA3.1plus vector (cV). Each mouse received two injections of

tumor cells on each flank. When the tumors reached similar volumes

[28±3 mm3, based on the formula: Tumor volume

(mm3)=length × width2 ×0.52], the mice were

sacrificed. The inner surface of their abdominal wall skins, which

covered the implant sites, was removed and spread onto filter

paper. Images of the newly formed blood vessels growing into the

injected tumor area were captured using a Canon SX50 HS (Zhuhai,

China) camera and were used for analysis.

In vivo tumorigenesis

A total of 24 eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were

divided randomly into three groups (n=8). Then 100 μl single cell

suspension (1×107 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium; HyClone,

Beijing, China), of either V192-N3, V192-N4 or V165-N6 EMT-6 cells

as well as cV was injected subcutaneously into the flank of mice in

the respective groups. N4 is a clone which has a capacity to

express more VEGF protein (~200 pg/ml) than that of clone N3

(~100pg/ml VEGF), which was used to determine the effect of the

VEGF192 expression level on the proliferation of EMT-6. When tumors

became palpable, tumor sizes were measured every two days using

calipers. Tumor volumes were calculated using the following

formula: Tumor volume (cm3)=length × width ×0.52.

Histological and immunohistochemical

analysis

Intradermal tumors (6–8 mm diameter; ~28

mm3) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Zhongshan

Bio-tech, Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), dehydrated and

paraffin-embedded, then cut into 5-μm sections. Sections were

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H.E.) (Zhongshan Bio-tech, Co.,

Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. H.E. sections

were examined by tumor histologist, Professor Su Ning from the

School of Medicine of Southeast University (Nanjing, China). For

immunohistochemical analysis, the sections were deparaffinized and

rehydrated into phosphate-buffered saline. Antigen retrieval was

performed using citrate buffer (pH 6.5) for 30 min at 92–98°C. The

sections were stained in order to identify endothelial cells using

the following antibodies: Rabbit anti-mouse CD31 monoclonal

antibody (Sino Biological, Inc., Beijing, China); followed by goat

anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G antibody (Zhongshan Bio-tech, Co.,

Ltd.). Antibody binding was visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine

(Zhongshan Bio-tech, Co., Ltd.) and signal amplification was

achieved via the avidin-biotin complex (Zhongshan Bio-tech, Co.,

Ltd.). Staining was then quantified according to the Chalkley

method (14).

Measurement of microvessel density

Tumor vascularization was assessed using the

Chalkley method. Areas of highest vascular density (‘hot spots’)

were identified at low magnification in the whole sections

(magnification, ×100). Magnification was then increased (x200) and

a point-counting grid was applied to each hot spot, a minimum of

three hot spots were counted in each representative tumor zone. The

most representative tumor zones were studied in each case. Results

of vessel density were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

(SD) of vessel number per mm2.

Wound healing

Confluent cell cultures were grown on 24-well plates

in DMEM-10% FBS. Wounds were generated with the tip of a

micropipette (~100 μm), and cells were maintained in serum-free

DMEM for 48 h. Following 24 h, cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet (Sangon Biotech).

Images of three fields of vision were captured and analyzed for

each well at ×100 magnification. Each experiment was performed in

triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. One-way

analysis of variance was performed to test for differences between

groups. Individual group comparisons were performed using the

unpaired Tukey’s post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference between values.

Results

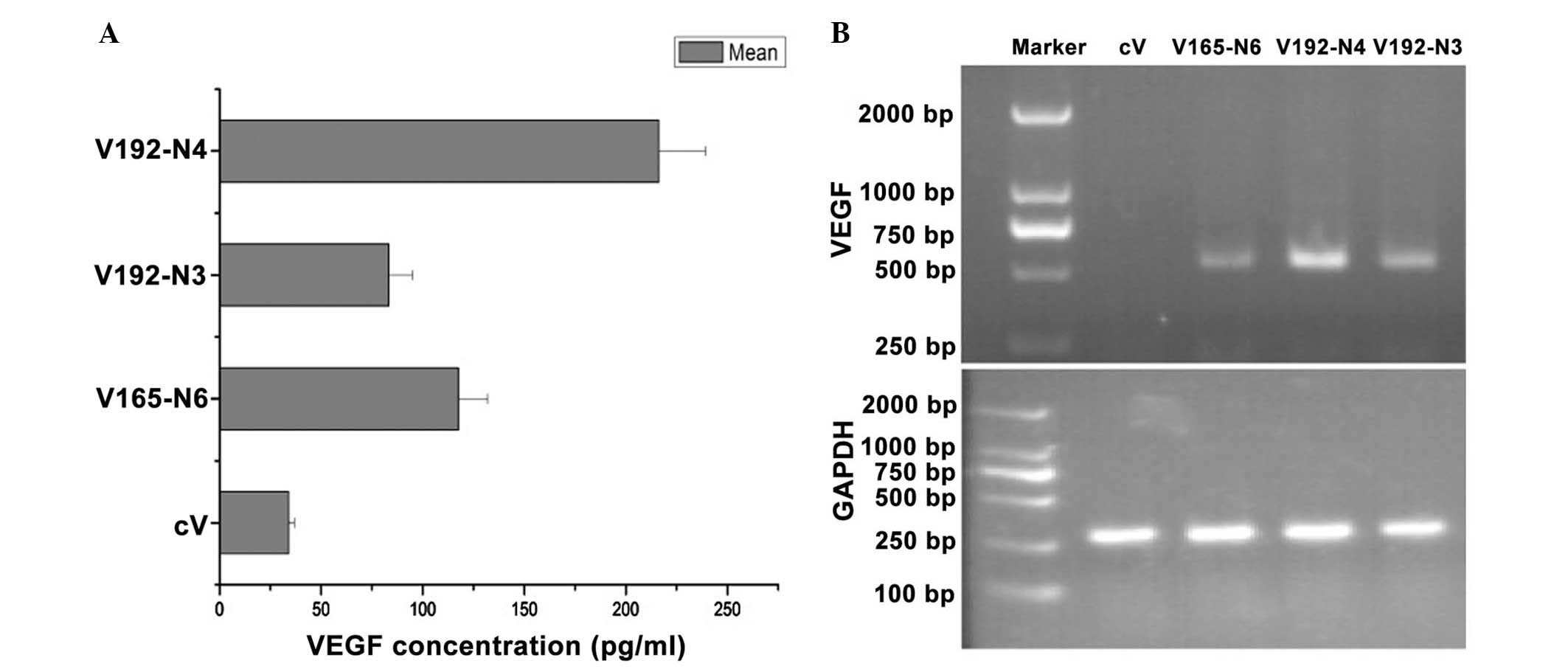

Overexpression of VEGF165 and VEGF192 in

stably transfected EMT-6 cells

EMT-6 cells were stably transfected with either cDNA

of VEGF165, VEGF192 or a control vector generating EMT-6 cell

clones V165, V192 and cV, respectively, in order to compare their

effects on the vascular pattern formation and angiogenic activity

in vivo. Nine clones stably overexpressing VEGF192 and

eleven clones stably overexpressing VEGF165 were obtained. ELISA

was used to screen the 100 μg/ml heparin-treated conditioned media

from the G418-resistant clones, which were further confirmed using

RT-semi-qPCR (Fig. 1).

Among the VEGF-expressing cells, clones V192-N3 and

V165-N6 produced comparable quantities of VEGF (Fig. 1A). These cells were then used in

the subsequent angiogenesis and tumorigenesis assays in

vivo. V192-N4, which produced a higher level of VEGF192 than

V192-N3, was also used to investigate the effects of increased

expression of VEGF192 on EMT-6 tumor growth. cV cells were used as

a control.

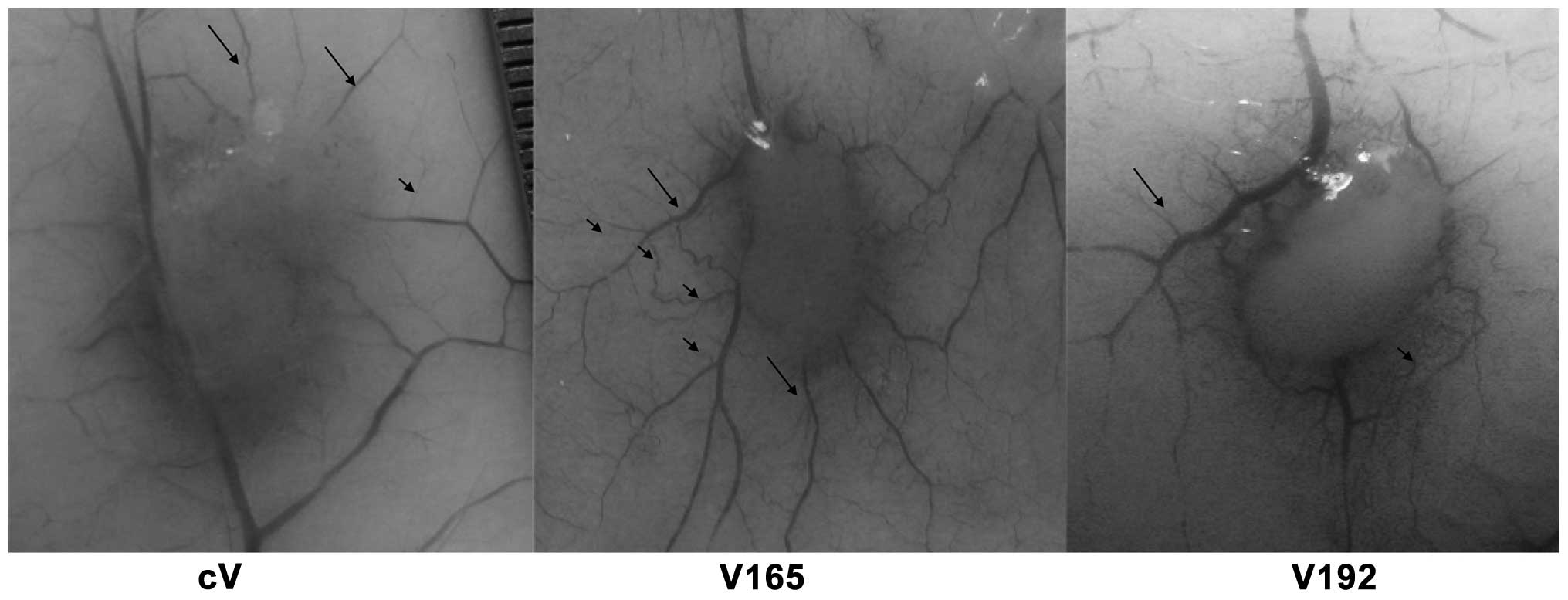

VEGF192 induces a distinct vascular

patterning in the skin adjacent to the tumor

EMT-6 clone cells V192-N3, V165-N6 and cV were each

inoculated intradermally to inspect and compare the vascular

pattern characteristics and angiogenic activities of VEGF192 and

VEGF165 in vivo. When the tumors reached a certain volume

(~28±3 mm3), the mice were sacrificed and the inner

surface of their abdominal wall skins, which covered the implant

sites, was removed and spread onto filter paper. Images were then

captured for analysis. As shown in Fig. 2, the cV-forming tumors were poorly

vascularized. The average number of second and third-type vessels

surrounding cV-induced tumors were 8±2 and 16±4, respectively

(Table I). However, the tumors

formed by V165-N6 and V192-N3 induced a significantly different

vascular patterning, as shown in Fig.

2. Highly vascularized tumors were induced by V165-N6,

demonstrating a tree-like normal branching; values of second and

third-type vessels surrounding V165 were 7±2 and 45±6 mm,

respectively (Table I). Regular

vascular patterning surrounded the tumor; however, the capillaries

spread further around the tumor, with an average secondary vessel

length of 9±2 mm, compared with the corresponding cV vessels of 5±2

mm. By contrast, the vascular patterning induced by V192-N3 was

dense, irregular and disorganized; capillaries were only observed

adjacent to the tumor, with a shorter average secondary vessel

length of 3±1 mm (Table I).

| Table IAverage number and length of the

secondary and tertiary level vessels. |

Table I

Average number and length of the

secondary and tertiary level vessels.

| Variable | cV | V165 | V192 |

|---|

| Number of secondary

vessels (n) | 8±2 | 7±2 | 16±3 |

| Number of tertiary

level vessels (n) | 16±4 | 45±6 | 37±6 |

| Length of secondary

vessels (mm) | 5±2 | 9±2 | 3±1 |

| Length of tertiary

level vessels (mm) | 3±1 | 2±0.5 | 1±0.5 |

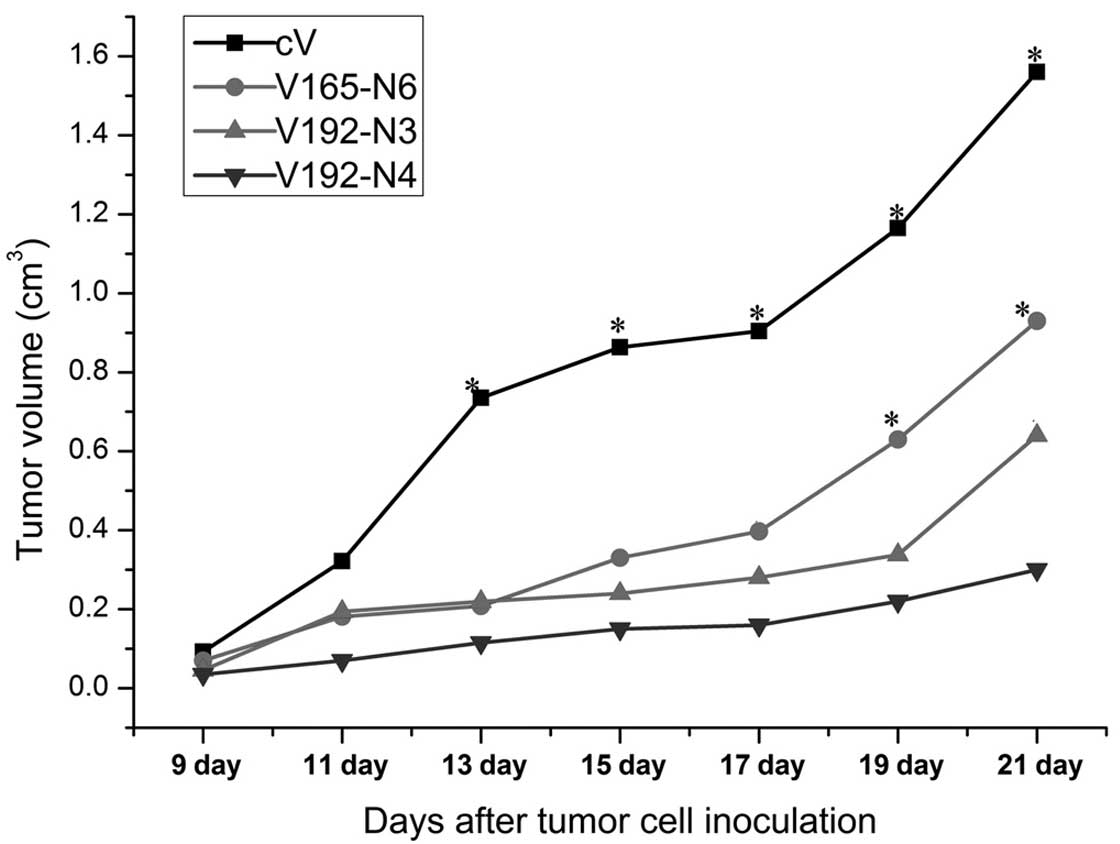

VEGF192 overexpression slows tumor growth

in vivo

The effects of VEGF192 or VEGF165 overexpression on

tumor growth were investigated using subcutaneous transplantations

of V192-N3, V192-N4, V165-N6 or cV EMT-6 clones into mice. As shown

in Fig. 3, each VEGF transfectant

demonstrated significant inhibition of tumor growth rates compared

to those of the cV control group from day 13 onwards. Furthermore,

from day 19 following inoculation the V165 tumor-forming group

demonstrated significantly higher tumor growth rates compared to

those of the two V192 groups. In addition, the V192-N4 group

appeared to have a slower growth rate compared with that of the

V192-N3 group; however, the difference was not statistically

significant. Overall the results indicated that the overexpression

of VEGF192 correlated with the strong inhibition of tumor

growth.

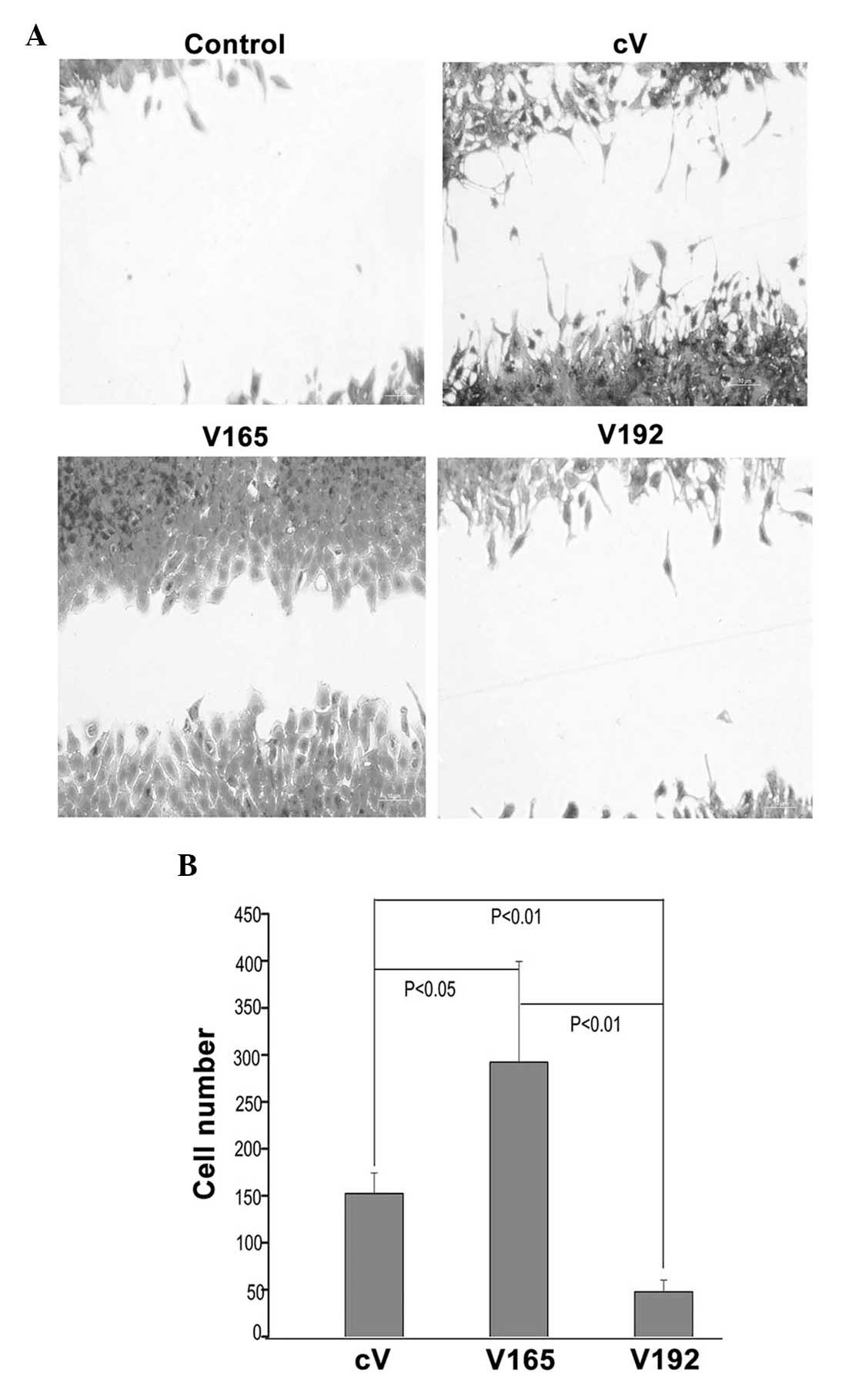

VEGF192 overexpression significantly

inhibits migration

Wound healing assays were used investigate the

effects of VEGF192 or VEGF165 overexpression on the migratory

capacity of EMT 6 cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, VEGF192-overexpressing cells

showed reduced migration compared to that of the

VEGF165-overexpressing and control cells. The number of

VEGF192-overexpressing EMT-6 cells migrating into the wound area

was significantly decreased compared to that of

VEGF165-overexpressing cells and control cells (P<0.05)

(Fig. 4B). This therefore

indicated that the overexpression of VEGF192 inhibited EMT-6 cell

migration.

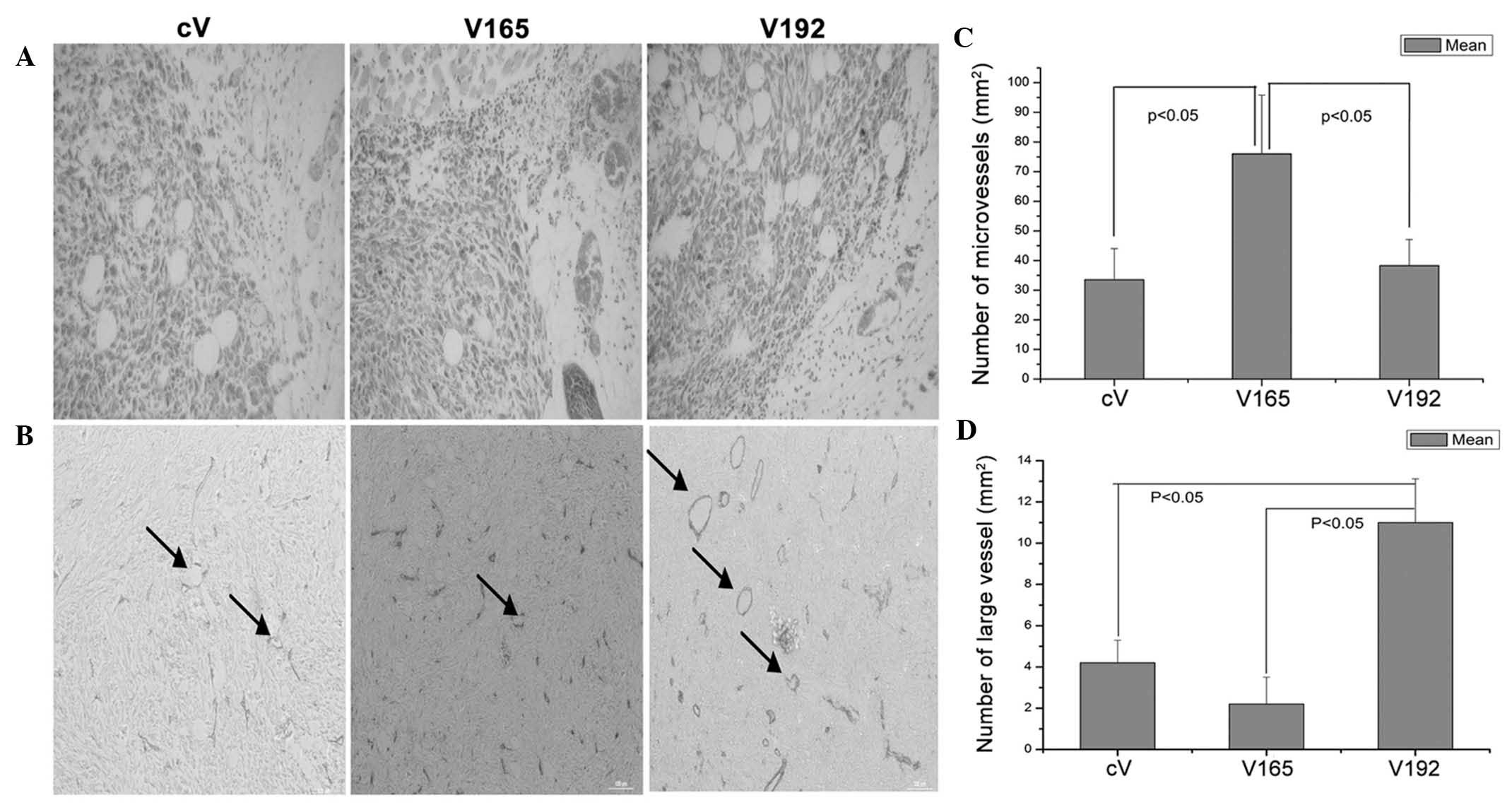

Immunohistochemical analysis of

microvessel density

As shown in Fig.

5A, there were no obvious areas of necrosis observed in the

histological sections from the cV and V165 cell tumors; however,

there was marked necrosis in sections from the V192 cell tumor. In

addition, areas of hemorrhage were observed in the V165 and V192

cell tumors.

VEGF165 and VEGF192-transfected clones producing

identical quantities of VEGF (V165-N6 and V193-N3) were selected

for immunohistochemical analysis of angiogenesis in vivo.

Mouse anti-CD31 monoclonal antibodies were used to assess the

microvessel density of allograft tumors. The results showed that

VEGF165-overexpressing tumors were significantly more vascularized

compared with the V192-overexpressing and cV tumors (Fig. 5B and C). Furthermore, no

significant difference was observed between the vascular densities

of the VEGF192-overexpressing tumors and those of the cV tumors;

however, the former exhibited a significantly enlarged vascular

caliber, with an increased total number of vessels >10 μm in

diameter, compared with that of the cV and V165-overexpressing

tumors (P<0.05) (Fig. 5B and

D).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the

effect of VEGF192 on angiogenesis and vascular patterning through

generating EMT-6 murine breast cancer clones which stably

overexpressed VEGF192 and VEGF165. Grunstein et al (15)utilized tumor cells which

overexpressed an individual isoform of VEGF-A and expressed low

levels of endogenous VEGF in order to investigate their effects on

tumor angiogenesis. The study reported marked differences in tumor

vascularization; however, endogenous VEGF was not eliminated from

the invading stroma (15). The

results of the present study demonstrated that the overexpression

of VEGF192 in EMT-6 tumor cells resulted in increased microvessel

density, distinct vascular patterning and a significantly reduced

tumor growth rate compared with those of VEGF165-overexpressing

tumors.

Previous studies have reported that the vasculature

in the adjacent areas to VEGF-overexpressing tumors may also

undergo structural alterations (12,16).

The VEGF gene produces several isoforms (primarily VEGF121, VEGF165

and VEGF189) through the process of gene splicing. VEGF isoforms

commonly differ due to the presence or absence of exons 6a and 7;

these two exons were reported to determine the diffusible or

sequestered (ECM-bound) states of VEGF proteins (17). Numerous studies have confirmed that

VEGF isoforms have different roles in vasculogenesis; these studies

included evidence from specific VEGF isoform knock-out experiments

in mice (18–20). In addition, it was reported that

normal VEGF concentration gradients were necessary for regular

vascular pattern formation (21);

for example, VEGF120/120 mouse embryos, engineered to express a

unique isoform of VEGF-A that lacks ECM (heparin)-binding domains,

showed significantly decreased capillary branching (18). Conversely, VEGF189 with an

ECM-binding domain was reported to provide stimulatory cues that

guided endothelial cell-sprouting for the initiation of vascular

branch formation (22). The

present study hypothesized that VEGF192 may have a higher affinity

for ECM compared with that of VEGF165 and therefore may be cleaved

by plasmin to release active VEGF isoforms (7). However, it was found that the formed

VEGF concentration gradient of VEGF192 was as effective as that of

VEGF165. Conversely, VEGF165 was found to have an intermediate

affinity for the ECM, with half the VEGF molecules in soluble form,

and could therefore form a VEGF concentration gradient. This may

therefore explain the difference between the highly-branched, dense

and disorganized vascular patterning in tumors of V192-transfected

cells and the normal branched, tree-like vascular patterning due to

V165-overexpression.

The results of the present study demonstrated that

the growth rates of V192-overexpressing tumors were slower than

those of V165-overexpressing tumors. A possible explanation for

this may be that due to the strong affinity to the ECM V192 was not

able to be completely cleaved by MMP or plasmin to form an

effective VEGF concentration gradient in vivo, which

resulted in a lower vascular density (Fig. 5B). Conversely, the growth rate of

specific VEGF isoform-overexpressing tumors in vivo was

previously found to be correlated with angiogenic activity as well

as the receptor expression profile of the tumor cells (23). Three receptors, namely VEGF

receptor (VEGFR) 1, VEGFR2 and neuropilin 1 (NRP1) have been

reported to bind VEGF. The expression of these receptors was

previously thought to be limited to endothelial cells; however,

they have also been reported to be expressed in certain cancer

cells (24,25). Furthermore, VEGF has been suggested

to be involved in the initiation of cancer cell migration and

proliferation (23). Therefore, it

may be inferred that the decreased V192 growth rate in the present

study was possibly due to the ineffective binding of V192 to NRP1

on EMT-6 cells (NRP1 and VEGFR1 expression were detected in EMT-6

cells using RT-semi-qPCR, data not shown). Hervé et al

(26) demonstrated that the

interaction of VEGF189 with NRP1 stimulated the proliferation of

MDA-MB-231 cells.

The peptide VEGF183 (132–158) contains MMP and

plasmin cleavage sites, in addition to the ECM-binding sequence

(core sequence, ‘KRKRKKSR’). Previous studies have confirmed the

interference of the ‘KRKRKKSR’ sequence with interactions of other

heparin-binding growth factors and their receptors (27). In VEGF189, exon 8 is located at the

C-terminus; therefore, the ‘KRKRKKSR’ sequence is not exposed to

the C-terminus, preventing direct interference with the VEGF

receptors. It is possible that this may be the mechanism by which

VEGF189 stimulated the dose-dependent migration of breast cancer

cells and proliferation of endothelial cells (26,28).

However, VEGF192 was not protected by VEGF exon 8, which may have

resulted in the interference of the ‘KRKRKKSR’ sequence with the

binding of V192 with the corresponding VEGF receptors. This may

therefore explain how VEGF192 overexpression could decrease the

growth rate and inhibit the migration of EMT-6 cells.

The microvessel density in tumors of cells

transfected with V192 was found to be decreased compared to that of

tumors of cells transfected with V165; however, the microvessel

caliber in tumors of cells transfected with V192 was significantly

increased compared with that of tumors of cells transfected with

V165 or cV. This phenomenon could not be explained and further

research is required for this to be elucidated. Previous studies

have demonstrated that the anchorage of different VEGFs to the ECM

may convey differential signaling responses to endothelial cells

(29). This therefore indicated

that the induced dilation of intratumoral vessels may have resulted

from the higher affinity of VEGF189 for the ECM (25).

In conclusion, the results of the present study

suggested that one of the functions of the exon 8 in VEGF-A was to

prevent the ‘KRKRKKSR’ sequence from interfering with the

interactions between heparin-binding growth factors and their

respective receptors. It has therefore been suggested that the

fusion of exon 8 to the C-terminus of VEGF192 may be beneficial for

its angiogenic activities. In addition, the present study confirmed

certain suspected characteristics of VEGF192, including the

stronger affinity for the ECM, a longer half-life and release via

plasmin-cleavage. However, it is now suggested that VEGF192 may be

more beneficial for use in the field of tissue engineering with

heparinized materials. Of note, VEGF192 provided a novel insight

into VEGF design and indirect evidence for the function of exon 8

of VEGF-A.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Basic

Science and Frontier Technology Planning Project of Henan Province,

Educational Commission of Henan Province and Scientific Research

Fund of Xinxiang Medical University (nos. 142300410027, 12B320021

and 2013ZD110, respectively).

References

|

1

|

Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers

H, Van Oosterom AT and De Bruijn EA: Vascular endothelial growth

factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 56:549–580. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Carmeliet P: Angiogenesis in life, disease

and medicine. Nature. 438:932–936. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lee RJ, Springer ML, Blanco-Bose WE, Shaw

R, Ursell PC and Blau HM: VEGF gene delivery to myocardium:

deleterious effects of unregulated expression. Circulation.

102:898–901. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hariawala MD, Horowitz JR, Esakof D, et

al: VEGF improves myocardial blood flow but produces EDRF-mediated

hypotension in porcine hearts. J Surg Res. 63:77–82. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Simons M: Angiogenesis: where do we stand

now? Circulation. 111:1556–1566. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Huiyong Z, Yong L, Yunxiao S, Wuling Z,

Jingjing L and Taiming L: Generation of a chimeric

plasmin-resistant VEGF165/VEGF183 (132–158) protein and its

comparative activity. Protein Pept Lett. 20:947–954. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Robinson CJ and Stringer SE: The splice

variants of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and their

receptors. J Cell Sci. 114(Pt 5): 853–865. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tammela T, He Y, Lyytikkä J, et al:

Distinct architecture of lymphatic vessels induced by chimeric

vascular endothelial growth factor-C/vascular endothelial growth

factor heparin-binding domain fusion proteins. Circ Res.

100:1468–1475. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Simons M: Silky, sticky chimeras-designer

VEGFs display their wares. Circ Res. 100:1402–1404. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Keskitalo S, Tammela T, Lyytikkä J, et al:

Enhanced capillary formation stimulated by a chimeric vascular

endothelial growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-C silk

domain fusion protein. Circ Res. 100:1460–1467. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zheng Y, Watanabe M, Kuraishi T, Hattori

S, Kai C and Shibuya M: Chimeric VEGF-ENZ7/PlGF specifically

binding to VEGFR-2 accelerates skin wound healing via enhancement

of neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 27:503–511.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D

and Iruela-Arispe ML: Processing of VEGF-A by matrix

metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular

patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 169:681–691. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lauer G, Sollberg S, Cole M, Krieg T and

Eming SA: Generation of a novel proteolysis resistant vascular

endothelial growth factor165 variant by a site-directed mutation at

the plasmin sensitive cleavage site. FEBS Lett. 531:309–313. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Suhonen KA, Anttila MA, Sillanpää SM,

Hämäläinen KM, Saarikoski SV, Juhola M and Kosma VM: Quantification

of angiogenesis by the Chalkley method and its prognostic

significance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer.

43:1300–1307. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Grunstein J, Masbad JJ, Hickey R, Giordano

F and Johnson RS: Isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor

act in a coordinate fashion to recruit and expand tumor

vasculature. Mol Cell Biol. 20:7282–7291. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mineur P, Colige AC, Deroanne CF, et al:

Newly identified biologically active and proteolysis-resistant

VEGF-A isoform VEGF111 is induced by genotoxic agents. J Cell Biol.

179:1261–1273. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ferrara N: Vascular endothelial growth

factor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 29:789–791. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Carmeliet P, Ng YS, Nuyens D, et al:

Impaired myocardial angiogenesis and ischemic cardiomyopathy in

mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms

VEGF164 and VEGF188. Nat Med. 5:495–502. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ruhrberg C, Gerhardt H, Golding M, et al:

Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding

VEGF-A control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev.

16:2684–2698. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Maes C, Stockmans I, Moermans K, et al:

Soluble VEGF isoforms are essential for establishing epiphyseal

vascularization and regulating chondrocyte development and

survival. J Clin Invest. 113:188–199. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ferrara N: Binding to the extracellular

matrix and proteolytic processing: two key mechanisms regulating

vascular endothelial growth factor action. Mol Biol Cell.

21:687–690. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stalmans I, Ng YS, Rohan R, et al:

Arteriolar and venular patterning in retinas of mice selectively

expressing VEGF isoforms. J Clin Invest. 109:327–336. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Schoeffner DJ, Matheny SL, Akahane T, et

al: VEGF contributes to mammary tumor growth in transgenic mice

through paracrine and autocrine mechanisms. Lab Invest. 85:608–623.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Soker S, Takashima S, Miao HQ, Neufeld G

and Klagsbrun M: Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor

cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial

growth factor. Cell. 92:735–745. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mercurio AM, Lipscomb EA and Bachelder RE:

Non-angiogenic functions of VEGF in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland

Biol Neoplasia. 10:283–290. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Hervé MA, Buteau-Lozano H, Vassy R, et al:

Overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor 189 in breast

cancer cells leads to delayed tumor uptake with dilated

intratumoral vessels. Am J Pathol. 172:167–178. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

27

|

Jia H, Jezequel S, Löhr M, et al: Peptides

encoded by exon 6 of VEGF inhibit endothelial cell biological

responses and angiogenesis induced by VEGF. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 283:164–173. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hervé MA, Buteau-Lozano H, Mourah S, Calvo

F and Perrot-Applanat M: VEGF189 stimulates endothelial cells

proliferation and migration in vitro and up-regulates the

expression of Flk-1/KDR mRNA. Exp Cell Res. 309:24–31. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chen TT, Luque A, Lee S, Anderson SM,

Segura T and Iruela-Arispe ML: Anchorage of VEGF to the

extracellular matrix conveys differential signaling responses to

endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 188:595–609. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|