Introduction

Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) are able to

extensively self renew and possess a multilineage differentiation

potential (1–3). In addition, MSCs exert a supportive

function through paracrine effects (4–6).

Therefore, these cells have a wide application in cell-based

therapies and tissue engineering. Over the last decade, MSCs

derived from alternative and easily accessible sources have

received increasing attention. MSCs can be isolated from a large

variety of fetal tissues, extraembryonic tissues and organs and a

variety of tissues from children and adults (7).

Human umbilical cord-derived MSCs (HUMSCs) can be

isolated and expanded easily in vitro without ethical

concerns. Therefore, they have received interest as a promising

candidate for several potential clinical applications (8) and several studies have demonstrated

that HUMSCs exhibit this potential (9). HUMSCs may possess a capacity for

autologous and allogenic transplantation due to their

immunoprivileged properties (10).

They are able to effectively suppress mitogen-induced T-cell

proliferation (11) and low levels

of rejection have been observed in animal transplantation studies

(12,13).

HUMSCs and dental pulp-derived stem cells (DPSCs)

offer available sources of autologous cells without ethical

controversy. Human DPSCs were initially reported by Gronthos et

al in 2000 and were observed to share a similar morphology and

in vitro differentiation potential with bone marrow MSCs

(14). DPSCs also possess

immunoregulatory properties and are capable of inducing activated

T-cell apoptosis in vitro and alleviating

inflammatory-related tissue injury (15). Impacted adult wisdom teeth and

naturally-exfoliated deciduous teeth do not ordinarily serve a

function in adults. Therefore, DPSCs can be obtained without

adverse effects on health.

HUMSCs are also amenable to genetic modification.

Kermani et al (16)

transfected HUMSCs with a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-reporter

gene and established a stable cell line. There have been no reports

on the genetic modification of DPSCs to date, to the best of our

knowledge. Survivin (SVV), a 16.5 kDa protein, is a member of the

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis family and exhibits broadly

cytoprotective properties (17).

In the present study, SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs were

investigated.

The potential clinical application of HUMSCs and

DPSCs remains to be elucidated. In the present study, the

differentiation, SVV-modified effects and molecular basis of the

heterogeneity between HUMSCs and DPSCs were investigated in

vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Preparation of HUMSCs and DPSCs

HUMSCs were isolated, as previously described, with

certain modifications (18). The

human umbilical cords were obtained from babies delivered at

full-term following institutional review board approval. A segment

of umbilical cord, cut to ~7 cm in length was obtained. This

segment was placed immediately into 25 ml complete medium,

comprising Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 (Gibco

Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (FBS; Gibco Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA),

100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco Life

Technologies). The tubes were stored on ice for dissection within 4

h. The umbilical cord segment was washed three times with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) without calcium and magnesium

(HyClone, Shanghai, China) and dissected longitudinally using an

aseptic technique. The umbilical vein and the umbilical arteries

were removed and the umbilical cord segment was cut into a 0.5–1

mm3 tissue block and incubated in 3 ml 0.2% collagenase

type II (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h at 37°C. A

five-fold volume of complete medium was added and the supernatant

was filtered using a 70-μm filter following free settling for 20

min. The cells were collected following centrifugation at 500 × g

for 5 min and plated in plastic culture flasks at a concentration

of 5×103/cm2. After 3 days, the non-adherent

cells were removed by washing three times with PBS. The medium was

changed every 2–3 days.

The human DPSCs were isolated as follows: Two adult

wisdom teeth from one patient aged between 18 and 30 years old,

which were extracted for clinical purposes at Tonji Hospital, Tonji

University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China), were collected and

the crown and root were separated. The dental pulp was isolated and

digested in 0.3% collagenase type I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at

37°C. The DPSCs were cultured in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM;

HyClone) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in 5%

CO2.

The HUMSCs and DPSCs were identified according to

the expression of antigens using flow cytometry with a Human

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Functional Identification kit (BD

Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of

Tonji Hospital, Tonji University School of Medicine (Shanghai,

China). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or

their families.

Differentiation characterization

The adipogenic, osteogenic and chondrogenic

differentiation potentials of the HUMSCs and DPSCs were determined

by incubating the cells in differentiation media using a Human

Mesenchymal Stem Cell Functional Identification kit (R&D

Systems, Inc, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Adipogenic differentiation

The HUMSCs and DPSCs were seeded onto 12 mm cover

slips at a density of 3.7×104 cells/well in the α-MEM

basal medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100

μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine. Theells were cultured in

an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. At 100% confluence, the

medium was replaced with the adipogenic differentiation medium

containing hydrocortisone, isobutylmethylxanthine, indomethacin in

95% ethanol and α minimum essential medium basal medium. (R&D

Systems, Inc). The medium was replaced every 3 days. After 2 weeks,

the cells on the cover slips were washed with PBS twice and fixed

with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology, Beijing, China) for 20 min at room temperature. The

cells were then washed with PBS and stained for 30 min using oil

red O (Sigma-Aldrich). Following washing twice with PBS, images of

cells were captured under a phase contrast microscope (IX71,

Olympus Corp., Tokyo Japan).

Osteogenic differentiation

In order to induce osteogenic differentiation,

7.4×103 HUMSCs and DPSCs per well were cultured for 3

weeks in α-MEM basal medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml

penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco Life

Technologies). At 50–70% confluency, the medium was replaced with

the osteogenic differentiation medium (R&D Systems, Inc), which

was replaced every 3 days. The cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed with PBS and stained using

alizarin red S (Sigma-Aldrich). Images of the cells were then

captured under a phase contrast microscope (IX71; Olympus

Corp.).

Chondrogenic differentiation

In order to induce chondrogenic differentiation,

2.5×105 cells were centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at

room temperature and resuspended in DMEM/F-12 basal medium

supplemented with 0.5 ml 100X ITS supplement (R&D Systems,

Inc), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 mM

L-glutamine. The cells were then centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min,

resuspended in chondrogenic differentiation medium (R&D

Systems, Inc) and centrifuged again. The resulting pellets were

incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 weeks and the medium

was replaced every 3 days. The pellets were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature and then

frozen and sectioned using standard cryosectioning methods. The

sections were stained using polyclonal goat anti-human aggrecan

antibody (1:10; #962644) and NorthernLights

557-fluorochrome-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody

(1:200; #NL001; R&D Systems, Inc) and images were captured

under a fluorescence microscope.

Lentiviral vectors and MSC

transduction

The MSCs were transduced with a pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen1

vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) containing an inserted

full length cDNA of SVV. Vectors without this insertion were used

as a control. The volume of lentivirus used for each transduction

was determined by titration as the volume required to generate

90–95% ZsGreen1-positive MSCs after 3 days.

Measurement of the levels of SVV in the

cell culture supernatant

The transduced MSCs were plated in six-well plates

(5,000 cells/cm2) overnight at 37°C in 5%

CO2. The medium was then replaced with 2 ml/well

DMEM/F12 for the HUMSCs and α-MEM for the DPSCs, followed by

incubation for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The supernatants

were collected in order to confirm overexpression and secretion of

SVV using a human enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit

according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Abcam, Cambridge, MA,

USA). The cell number was determined for normalization.

Western blotting

To detect the overexpression of SVV in the HUMSCs

and DPSCs, the proteins in the transduced cells were extracted

using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer supplemented with

1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The proteins were loaded onto 12%

SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to polyvinyline difluoride membranes

(EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Following blocking with 5%

defatted milk [defatted milk powder (Quechao, Beijing, China) in

tris-buffered saline supplemented with Tween20] for 1 h, the

membranes were incubated with survivin (FL-142) rabbit polyclonal

antibody raised against amino acids 1-142 of human survivin (1:100;

sc-10811; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA)

overnight at 4°C.

DPSC transplantation

As been previous studies have examined the survival

and differentiation of umbilical cord-derived MSCs in vivo

(19), the current study focused

on the properties of the DPSCs in vivo.

All experimental procedures involving animals were

conducted under the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee

of Tongji University (Shanghai, China). Female C57BL/6 mice were

housed at 22°C and 65% humidity with a 12 h light/dark cycle and

access to food and water ad libitum.

The mice were randomly assigned to one of the

following three groups: Control mice injected with PBS (n=6); mice

transplanted with DPSCs (n=6) and mice transplanted with

SVV-modified DPSCs (n=6). The adult 8-week-old mice were

anesthetized using 0.5% pentobarbital sodium (Sigma-Aldrich). The

heads of the mice were shaved and cleaned and the mice were then

positioned in the stereotaxic apparatus, with anesthesia maintained

during surgery. A midline incision was made on the scalp and the

skin was retracted to expose the bregma. Burr holes (0.5 mm) were

then placed directly over the striatum (coordinates:

anterior/posterior, +0.5 mm; medial/lateral, +2.0 mm from the

bregma). The control and SVV-modified DPSCs were resuspended at a

density of 100,000 cells/μl in PBS. The cells were transplanted

(−3.5 mm ventral to the skull surface) into the control and

SVV-modified DPSCs at a constant rate of 0.5 μl/min in a total

injection volume of 2 μl/mouse using a 10-μl Hamilton microsyringe

(Dalian Replete Scientific Instrument Co. Ltd, Dalian, Liaoning,

China). The syringe was left in place for 3 mins and then

retracted. The wound was closed and the mice were placed on heat

insulation pads (Kent Scientific Corporation, Torrington, CT, USA)

until conscious.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry was performed in order to

examine the survival and differentiation of the control and

SVV-modified DPSCs in the brains of the mice. Following cell

transplantation, the mice were anesthetized for either 4 or 14 days

using pentobarbital sodium and perfused transcardially with 0.1 M

PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4)

to fix the tissues. The brains were removed promptly, post-fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C and then transferred to 30%

sucrose in 0.1 M PBS for 2 days at 4°C. Coronal sections (20 μm)

were then cut and mounted on positively-charged microscope slides

(Ruihoge, Nanjing, China). For immunohistochemical analysis, the

tissue was blocked using 10% normal goat serum (CST, Boston, MA,

USA) in PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X (Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at

room temperature. The tissues were then cultured with primary

antibodies against rabbit SVV (1:100; sc-10811; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), rabbit anti-human/mouse/rat neuronal nuclei

(NeuN; 1:500; 1:500; Abcam) and rabbit anti-cat/dog/mouse/rat/sheep

glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:500; Nr.z 0334; Dako North

America, Inc. Carpinteria, CA, USA) at 4°C overnight. All

antibodies were polyclonal. The following day, the tissues were

rinsed three times in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and

incubated with conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit

AlexaFluor594; 1:500; A-11037; Invitrogen Life Technologies) for 1

h at room temperature. Subsequently, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

(1:1,000; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to label the positions of the

cell nuclei. Images of the fluorescent labels were captured using a

Nikon fluorescent microscope (Eclipse Ti-S; Nikon Corporation,

Tokyo, Japan) at ×20 magnification. All the images were analyzed

using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD,

USA). Briefly, images of the transplanted cells were captured from

five sections of each animal and the average intensity of the

labels in each group was analyzed.

RNA sequencing and analysis

In order to compare the gene expression profile

between the control and the SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs, RNA

isolation was performed on the cells using TRIzol®

reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and the total RNA was then

digested with DNase I (Invitrogen Life Technologies) to ensure that

the samples were not contaminated with genomic DNA. Duplicate

experiments were performed for each sample. Library preparation and

paired end sequencing (101 bp length) were performed using an

Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Short

reads were aligned to the reference human genome (Homo

sapiens GRCh37) using TopHat (20). The gene annotations were from the

Ensembl database, packaged using iGenome (Illumina). The sequence

reads were used to calculate the overall gene expression in terms

of the reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM).

The differentially expressed transcripts were screened using the

cufflinks procedure (21).

Abundant genes

Genes with an RPKM value >100 and levels of gene

expression ≥2-fold higher than the control groups were identified

in the HUMSCs, DPSCs and SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs and

functional enrichment analyses were performed using the Gene

Ontology database (http://www.geneontology.org/GO.downloads.annotations.shtml).

and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway database

(http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html).

Genes associated with stem cell

differentiation

A total of five genes associated with stem cell

differentiation, with RPKM values >5 in the control and

SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs, were selected based on the Gene

Ontology database.

Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction

genes

A total of eight genes associated with

cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, with RPKM values >5 in

the control and SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs, were selected based

on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway

database.

Data presentation and statistical

analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of

the mean (error bars). All significant differences were evaluated

using Student’s t-test or analysis of variance. Statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL,

USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Phenotypic characterization of isolated

HUMSCs and DPSCs

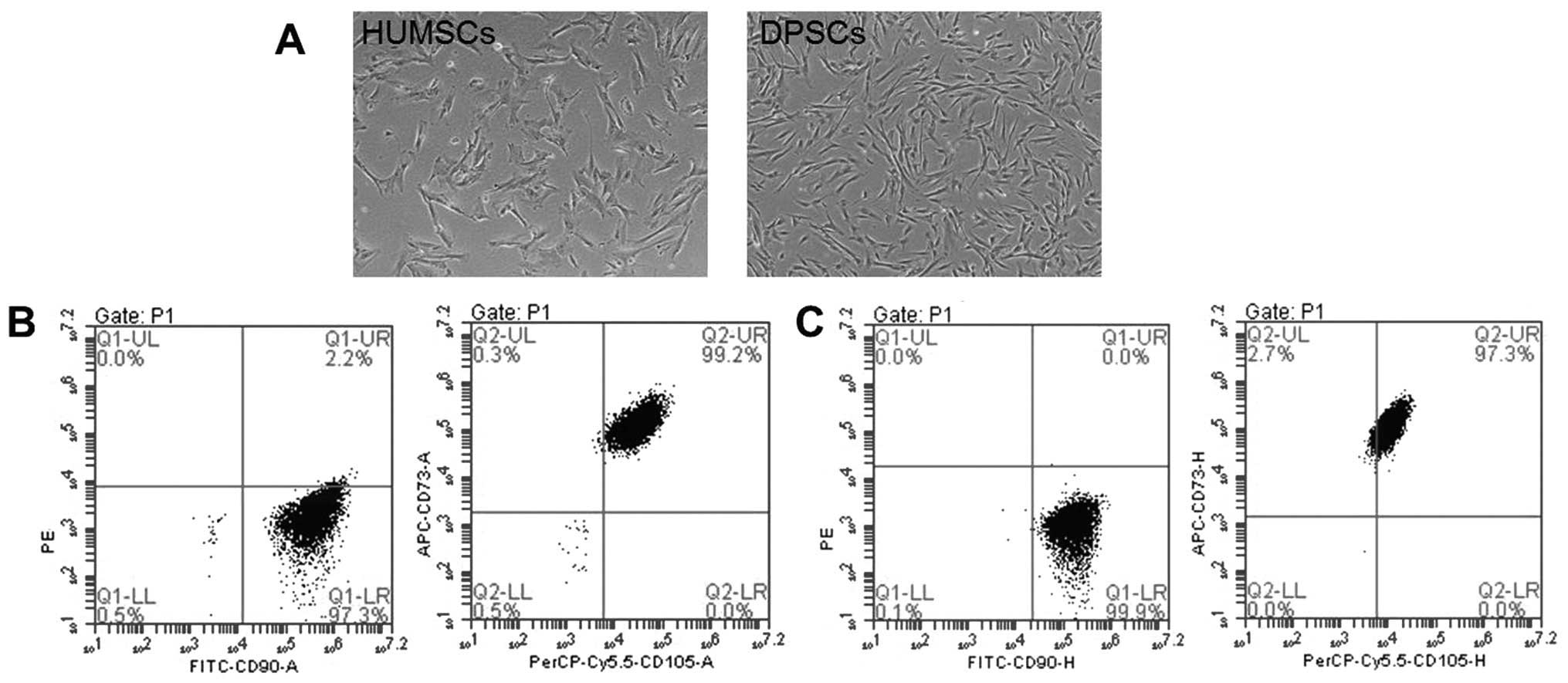

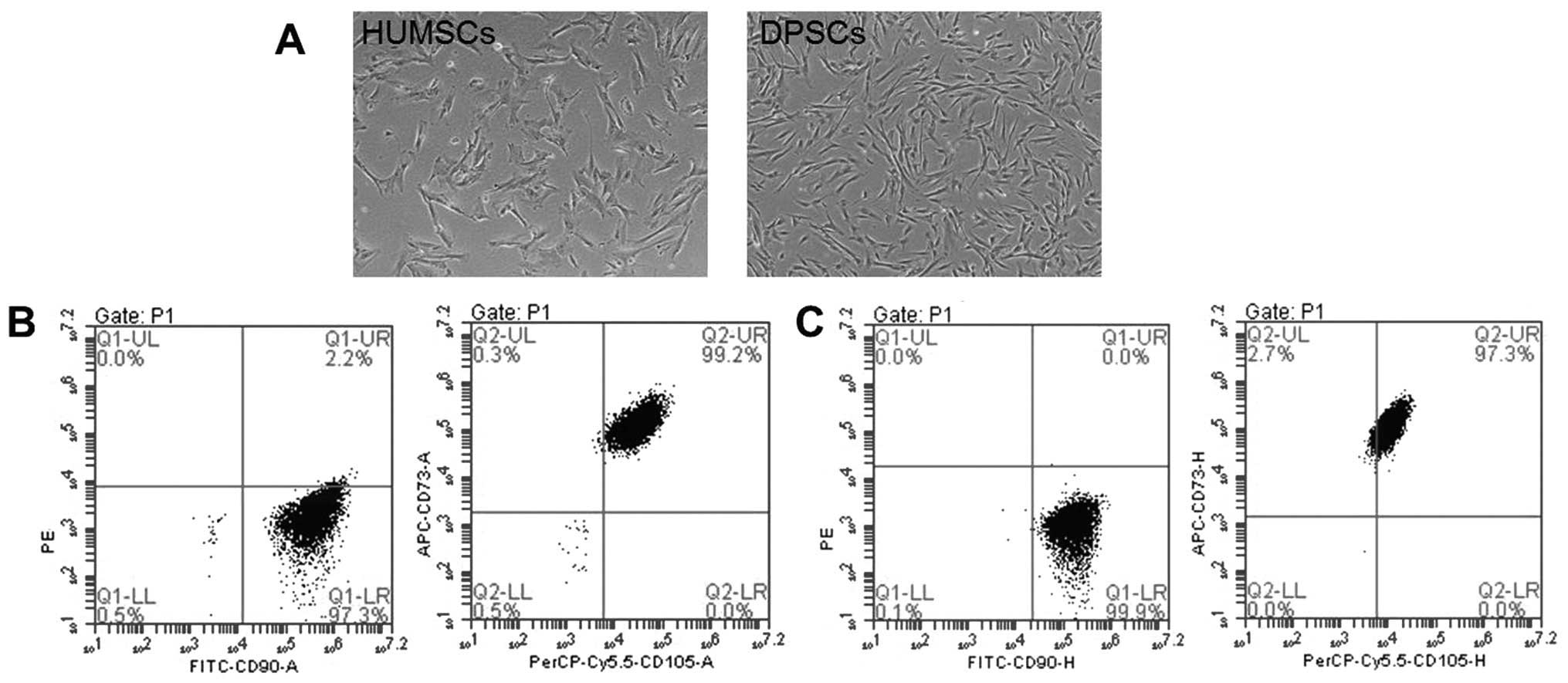

The shapes of the DPSCs were more similar to those

of fibroblasts compared with the HUMSCs (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometric analysis

revealed that the HUMSCs and DPSCs expressed a set of cluster of

differentiation (CD) MSC markers (CD90, CD73 and CD105), however,

they did not express endothelial/hematopoietic markers (CD34, CD45,

CD11b or CD14, CD19 or CD79α or HLA-DR; Fig. 1B and C).

| Figure 1Phenotypic characterization of HUMSCs

and DPSCs. (A) Passage 5 DPSCs were more similar to fibroblasts

than the HUMSCs. Scale bar: 500 μm. (B) 96.5% of the HUMSCs were

positive for CD73, CD90 and CD105, but negative for CD34, CD45,

CD11b or CD14, CD19, CD79α and HLA-DR. (C) 99.2% of the DPSCs were

positive for CD73, CD90 and CD105, but negative for CD34, CD45,

CD11b or CD14, CD19, CD79α and HLA-DR. HUMSCs, human umbilical

cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells; DPSCs, dental pulp-derived

stem cells; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; CD, cluster of

differentiation. |

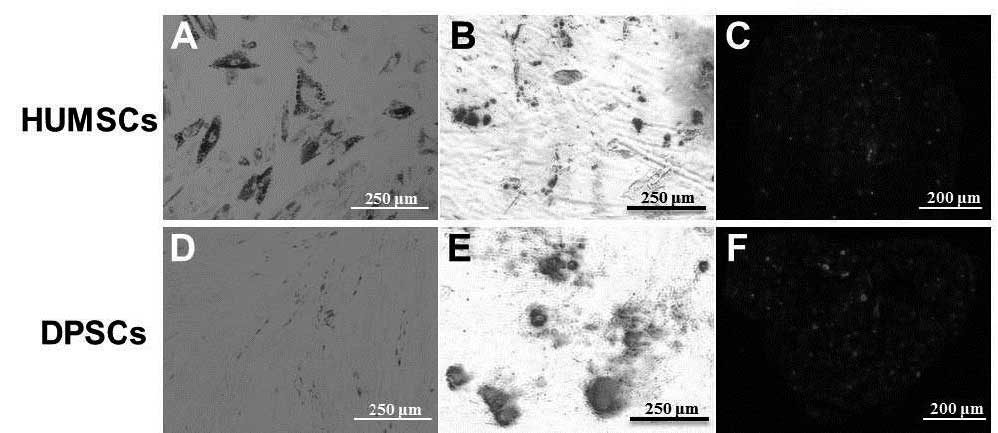

Identification of differentiation

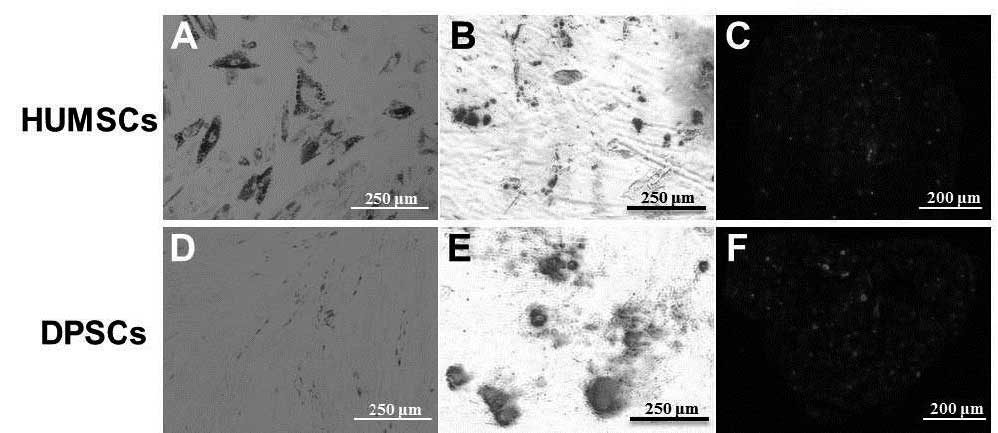

Following induction with adipogenic differentiation

medium for 2 weeks, lipid droplets, stained using oil red O, were

observed in the HUMSCs (Fig. 2A),

but not the DPSCs (Fig. 2D). For

osteogenic differentiation, the cells were cultured for 3 weeks in

osteogenic media. Calcium precipitation, determined by alizarin red

S staining, was observed in the HUMSCs and the DPSCs (Fig. 2B and E). The chondrogenic

differentiation capacity of the HUMSCs and DPSCs were evaluated by

examining the expression of aggrecan, a chondrogenic marker.

Following culture with the HUMSCs and DPSCs in chondrogenic

differentiation medium for 3 weeks, the cells exhibited increased

expression of aggrecan (Fig. 2C and

F).

| Figure 2Adipogenic, osteogenic and

chondrogenic differentiation of the (A-C) HUMSCs and (D-F) DPSCs,

respectively. Lipid droplets, stained using oil red O, were present

in the (A) HUMSCs, but not the (D) DPSCs (Scale bar: 250 μm).

Osteogenic differentiation in the (B) HUMSCs and (E) DPSCs was

detected using alizarin red S staining of calcium precipitation

(Scale bar, 250 μm). Aggrecan, a chondrogenic marker, was highly

expressed in the (C) HUMSCs and (F) DPSCs (Scale bar, 200 μm).

HUMSCs, human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells; DPSCs,

dental pulp-derived stem cells. |

Efficiency of MSC transduction with

lentiviral vectors containing SVV

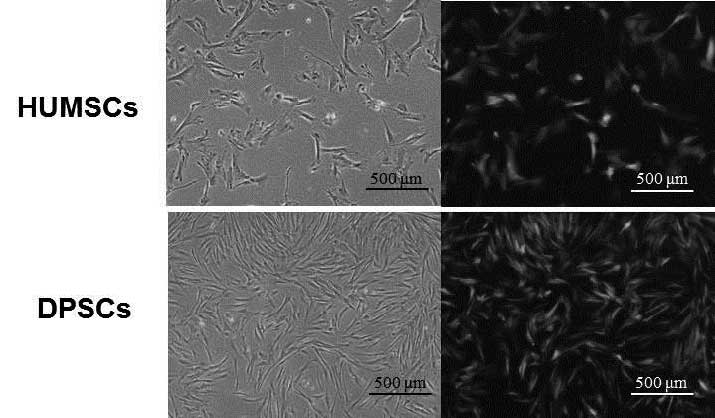

Following infection with the SVV recombinant

lentivirus, overexpression of GFP was observed in the HUMSCs and

DPSCs (Fig. 3). The efficiency of

gene transduction was >90%.

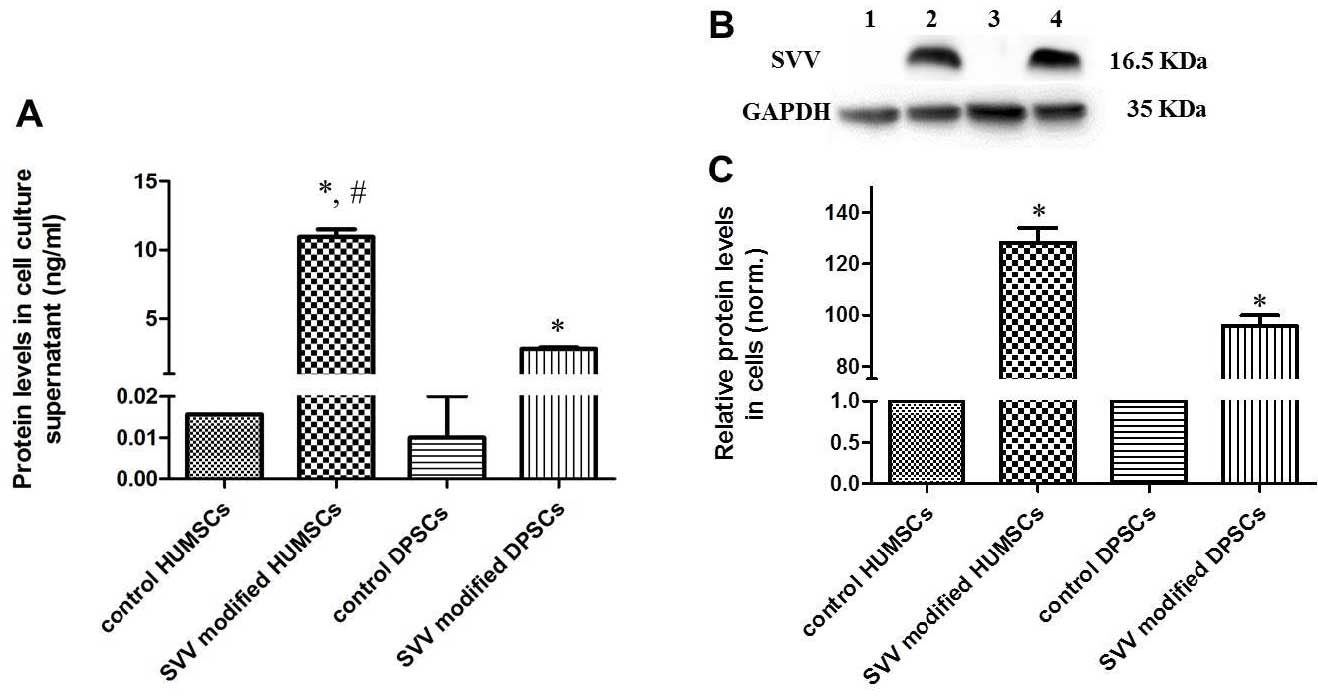

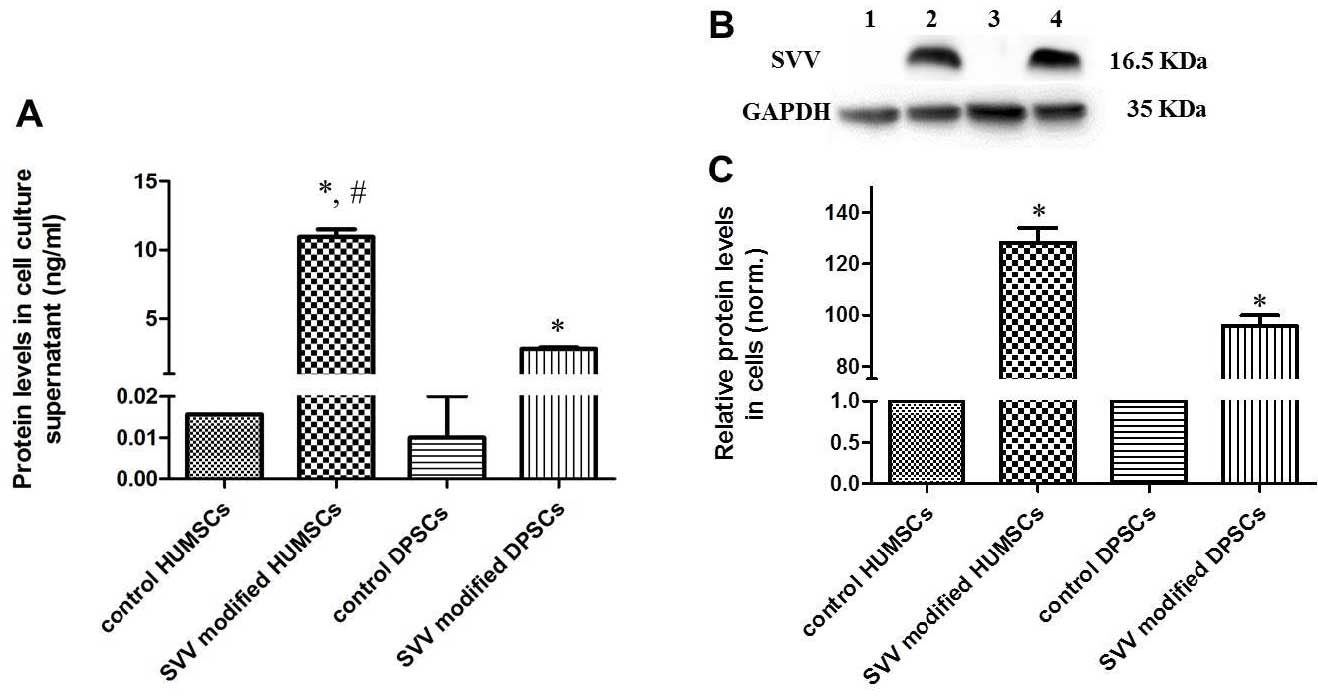

Protein expression of SVV

The protein expression levels of SVV were determined

by ELISA and western blotting. The protein levels of SVV were

significantly increased in the cell culture supernatant of the

SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs compared with levels in the control

groups (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the

secretion of SVV in the modified HUMSCs was significantly higher

compared with that observed in the modified DPSCs. The western

blotting revealed that modified HUMSCs and DPSCs exhibited a

significant increase in the expression of SVV (Fig. 4B and C).

| Figure 4Protein levels of SVV are

significantly increased in the SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs. (A)

Protein levels of SVV were measured in the cell culture supernatant

using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (B) Representative

western blot analysis of the control, SVV-modified HUMSCs and

DPSCs. The level of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Lanes:

1, HUMSCs; 2, SVV-modified HUMSCs; 3, DPSCs; 4, SVV-modified DPSCs.

(C) Quantitative analysis revealed that the modified HUMSCs and

DPSCs had a significantly higher expression of SVV.

(*P<0.05, compared with the control and

#P<0.05, compared with the SVV-modified DPSCs.

HUMSCs, human umbilical cord-derived mesechymal stem cells; DPSCs,

dental pulp-derived stem cells; SVV, survivin. |

Control and SVV-modified DPSCs survive

following intrastriatal transplantation

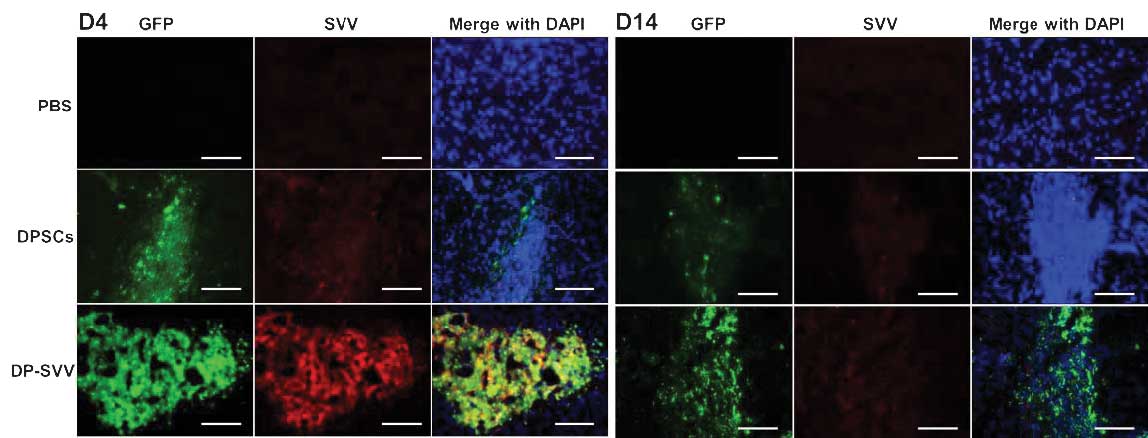

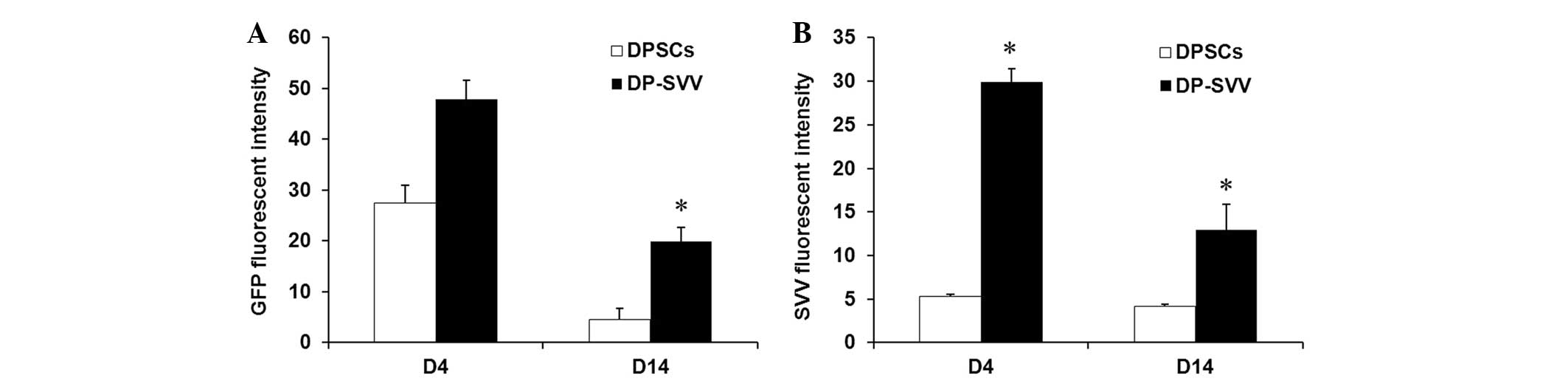

In the present study, the survival and the

expression of SVV in the control and SVV-modified DPSCs were

investigated in vivo. The results demonstrated that the GFP

signal, expressed by the inserted pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen1 vector, was

marked in the control and SVV-modified cell lines 4 days after

transplantation, however, it had weakened by day 14 (Fig. 5). In addition, the GFP signal in

SVV-modified DPSCs was more marked compared with that in the

control cells (Fig. 6). These

results suggested that SVV promoted the survival of the DPSCs in

vivo. The expression of SVV in the transplanted SVV-modified

DPSCs was higher than that in the control DPSCs on day 4. However,

the expression of SVV in the transplanted DPSCs decreased 14 days

after transplantation.

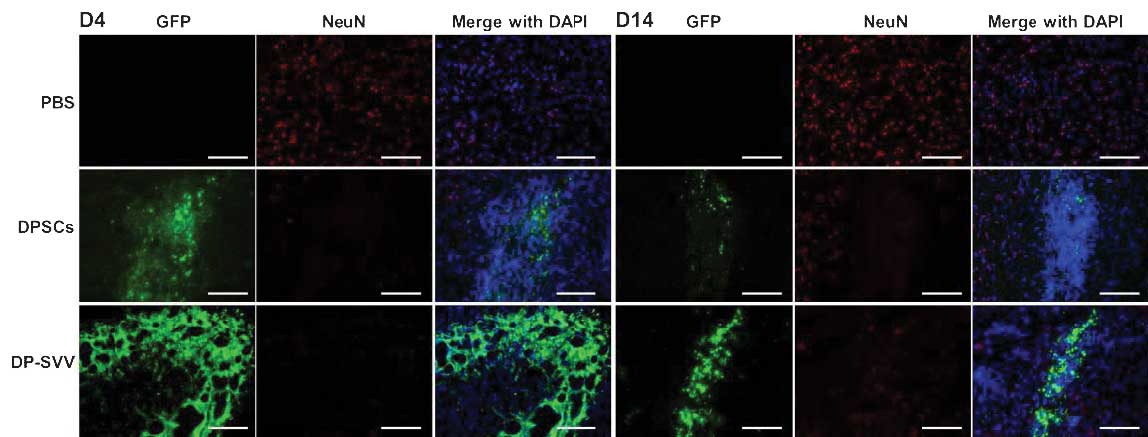

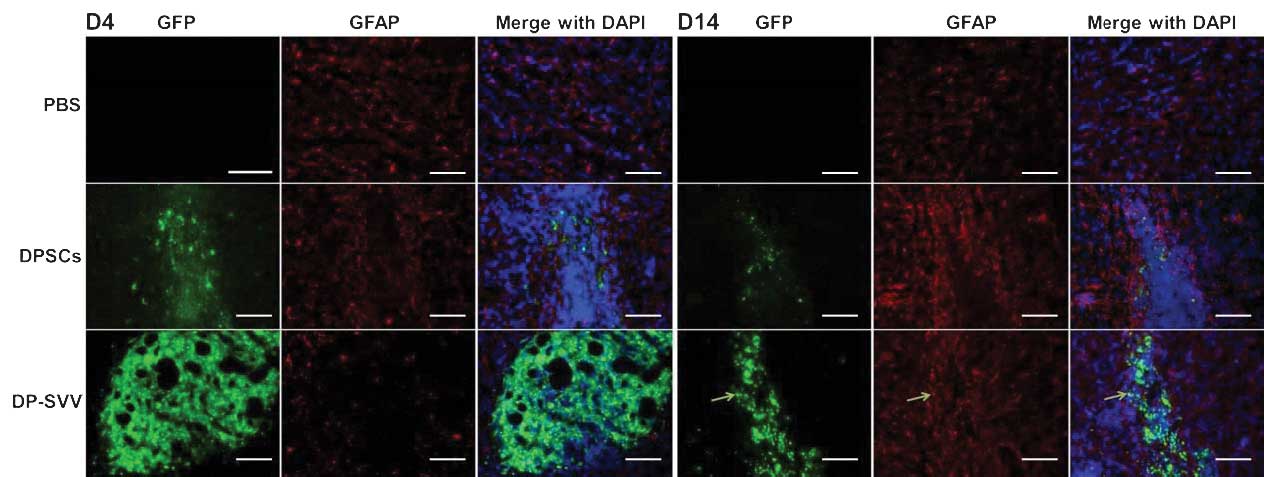

In addition, the present study examined the

differentiation capacity of the control and SVV-modified DPSCs

in vivo. Neither NeuN (a marker for neurons) nor glial

fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; a marker for astrocytes) were

detected in the control or SVV-modified DPSCs 4 days after

transplantation (Figs. 7 and

8). However, 14 days after

transplantation, a few GFP-labeled cells coexpressed GFAP (Fig. 8), but not NeuN (Fig. 7) in the striatum.

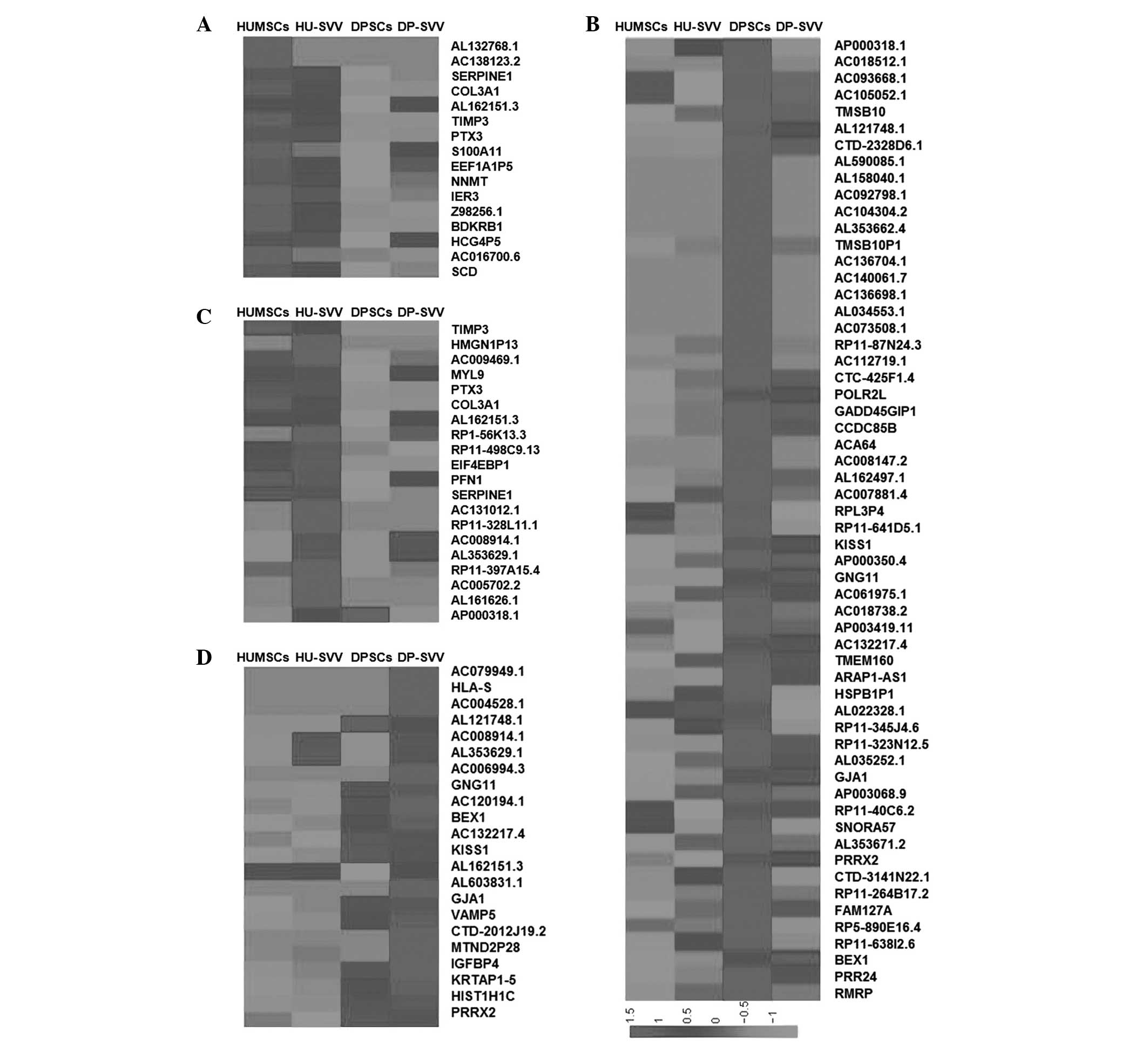

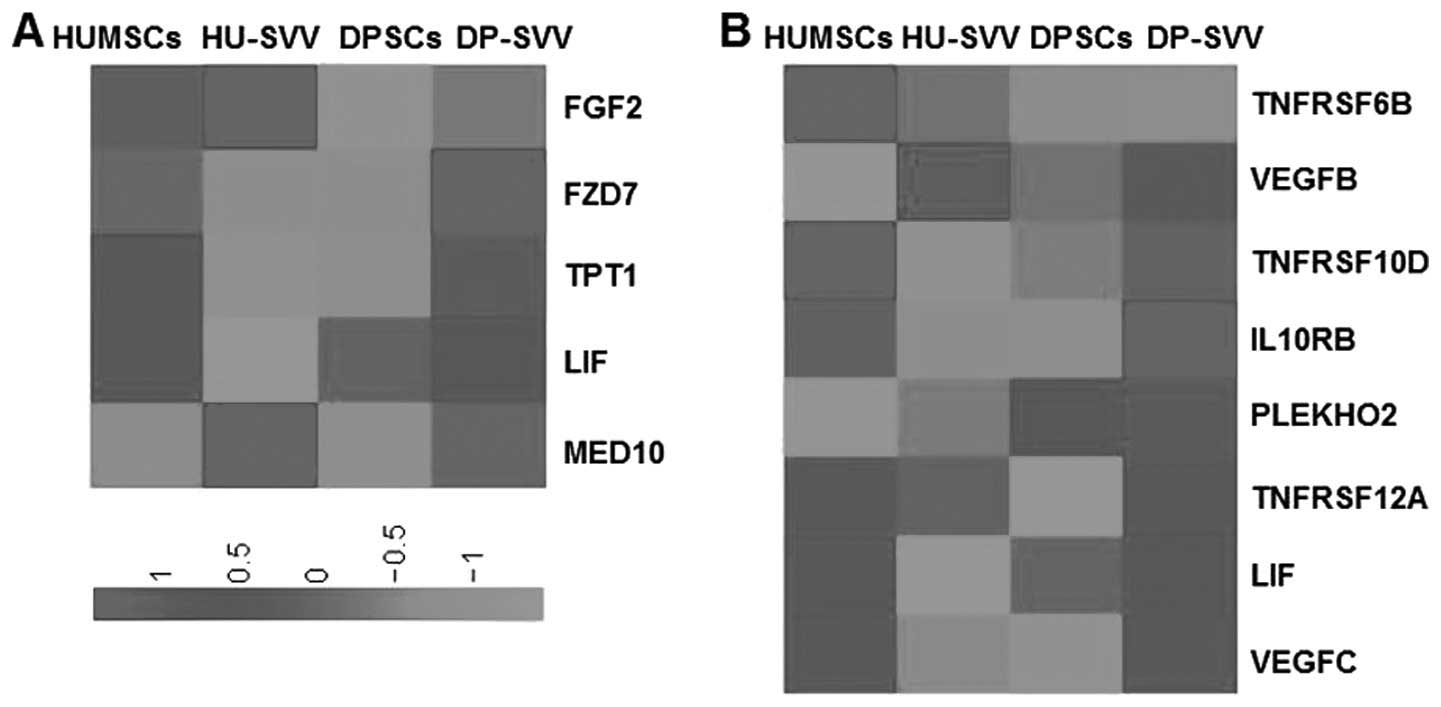

Gene expression data analysis

The heat map of the abundant gene set is shown in

Fig. 9. The genes with RPKM values

>100 were analyzed with respect to each MSC group. A total of

16, 20, 58 and 22 genes were identified with RPKM values >100

and gene expression levels ≥2-fold higher in the HUMSCs,

SVV-modified HUMSCs, DPSCs and SVV-modified DPSCs, respectively,

compared with the control (Fig.

9). The most significant biological processes were

‘inflammatory response’, ‘vascular transport’, ‘platelet

activation’ and ‘vascular transport’ for the HUMSCs, DPSCs,

SVV-modified HUMSCs and SVV-modified DPSCs, respectively. The most

significant pathways were ‘complement and coagulation cascades’,

‘hypoxia-inducible factor-1 signaling pathway’, ‘RNA polymerase’

and ‘SNARE interactions in vesicular transport’ for the HUMSCs,

DPSCs, SVV-modified HUMSCs and SVV-modified DPSCs,

respectively.

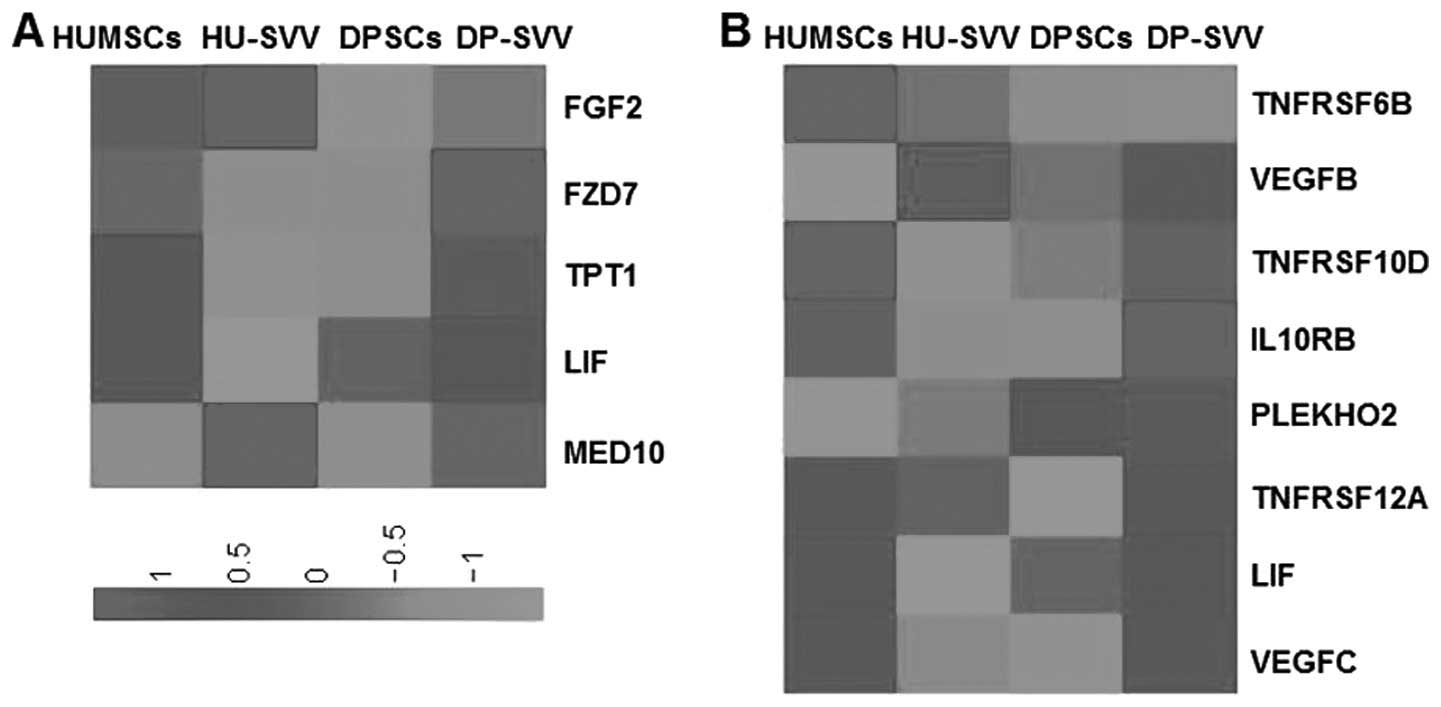

The expression of genes associated with biological

activities among the groups was analyzed in order to clarify the

molecular basis of the heterogeneity. Since MSCs possess

multilineage differentiation potential, genes associated with stem

cell differentiation were analyzed in the control and the

SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs. A total of 128 genes were identified

as associated with stem cell differentiation in the four cell lines

and genes with RPKM values >5 were selected. Analysis

demonstrated higher expression levels of the FGF2 and MED10 stem

cell differentiation genes in the SVV-modified HUMSCs, compared

with the HUMSCs, DPSCs and SVV-modified DPSCs (Fig. 10A) and increased expression of

FZD7 in the SVV-modified DPSCs compared with HUMSCs, HU-SVV and

DPSCs. MSCs exhibit anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory

properties (22). Therefore, a

comparative analysis of genes associated with cytokine-cytokine

receptor interactions in the control and SVV-modified HUMSCs and

DPSCs was also performed. A total of 196 genes associated with

cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions were identified, from which

genes with RPKM values >5 were selected. Clustering highlighted

a group of genes with increased expression in the HUMSCs compared

with HU-SVV, DPSCs and DP-SVV, including tumor necrosis factor

receptor superfamily (TNFRSF)6B, TNFRSF10D, LIF and vascular

endothelial growth factor C (VEGFC; Fig. 10B). Clustering also highlighted a

group of inflammatory-associated genes, the expression levels of

which were highest in the SVV-modified DPSCs, including IL10RB,

PLEKHO2, TNFRSF12A and VEGFC.

| Figure 10Heat map of genes associated with stem

cell differentiation and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction.

(A) Genes associated with stem cell differentiation with RPKM

values >5 were compared through RPKM value analysis in the

HUMSCs, HU-SVV, DPSCs and DP-SVV cells. (B) Genes associated wirth

cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions with RPKM values >5 in

the four cell lines. RPKM, reads per kilobase of exon per million

mapped reads; HUMSCs, human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem

cells; DPSCs, dental pulp-derived stem cells; SVV, survivin;

HU-SVV, SVV-modified HUMScs; DP-SVV, SVV-modified DPSCs; TNFRSF,

tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily; VEGF, vascular

endothelial growth factor. |

Discussion

MSCs may be isolated from a variety of sources,

including bone marrow, umbilical cord, adipose tissue and dental

pulp, and they may be used in several cell-based therapies and

tissue engineering approaches. It is important to select the type

of MSCs that are the most promising candidates for specific

clinical applications. In the present study, the appearance of the

DPSCs were more elongated compared with the HUMSCs. The surface

antigens, CD90, CD73 and CD105, were used for the identification of

HUMSCs and DPSCs, as these markers are indicated by the

International Society for Cellular Therapy as positive markers for

human MSCs (23). These MSCs lack

expression of surface markers of endothelial or hematopoietic

origin, including CD34, CD45, CD11b or CD14, CD19 or CD79α and

HLA-DR.

In the present study, lipid droplets were observed

in the HUMSCs rather than the DPSCs following the induction of

adipogenic differentiation. Osteogenic differentiation was observed

through calcium precipitation in the HUMSCs and DPSCs. The

chondrogenic differentiation capacity of the HUMSCs and DPSCs was

also evaluated by examining the expression level of aggrecan, which

was marked in the two cell lines. These results indicated that the

HUMSCs were more likely to differentiate into adipocytes compared

with the DPSCs and that the two cell types are able to

differentiate into osteoblasts and chondroblasts. These findings

are consistent with those of Mangano et al (14) and Gronthos et al (24), which demonstrated that DPSCs can be

induced to differentiate into osteoblasts, but not adipocytes.

Following transduction of the HUMSCs and DPSCs with

a lentiviral vector, containing the full-length cDNA of survivin

insertion, the expression of GFP indicated that the efficiency of

gene transduction was >90%. The protein expression of SVV in the

HUMSCs and DPSCs was compared using an ELISA assay and western

blotting. The protein levels of SVV significantly increased in the

SVV-modified HUMSCs and DPSCs compared with the controls. However,

the expression of SVV in the cell culture supernatant was

significantly higher in the SVV-modified HUMSCs compared with the

SVV-modified DPSCs. Therefore, modified HUMSCs secreted more SVV

protein compared with the modified DPSCs.

SVV is an important protein for cell death

resistance and has been reported to modulate stem cell

proliferation (25). As MSCs

promote tissue repair by stimulating and modulating tissue-specific

cells (4), SVV may enhance these

stimulating and modulating effects of MSCs. A previous study on the

differentiation of umbilical cord-derived MSCs in vivo

(19), observed no neuronal or

glial differentiation in the transplanted umbilical cord-derived

MSCs. Therefore, the present study focused on the survival and

differentiation of DPSCs in vivo. The results confirmed that

SVV promoted the survival and astrocyte differentiation of the

DPSCs in vivo.

The RNA sequencing analyses provided novel insight

into the variable biological properties among the four groups.

Higher levels of the expression of FGF2, which is involved in the

development of the limb and nervous system, were observed in the

SVV-modified HUMSCs and FZD7, which encodes receptors for Wnt

signaling proteins, in the SVV-modified DPSCs. Genetic analyses

elucidates the MSC-mediated anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory

properties of the different groups. The expression of IL10RB, an

anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory gene, was higher in the

SVV-modified DPSCs than in the DPSCs, HUMSCs and SVV-modified

HUMSCs. The expression levels of the TNFRSF6B and TNFRSF10D

anti-inflammatory genes were higher in the HUMSCs than in DPSCs or

SVV-modified DPSCs and HUMSCs. Therefore, HUMSCs express higher

levels of anti-inflammatory, immunoregulatory and stem cell

differentiation-associated genes than DPSCs.

In conclusion, the source of MSCs and their

subsequent modification can be selected according to the difference

in differentiation, the effect of genetic modification and the

molecular basis of the HUMSCs and DPSCs. However, further

investigation is required in order to decide which cell line is

most suitable for a specific clinical application.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Program

of Shanghai Subject Chief Scientist (grant no. 2012XD1404400), the

State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China

(grant no. 81330030), the Excellent Academic Leaders of Shanghai

Health Field (grant no. XBR2013094), the National Science

Foundation for Post-doctoral Scientists of China (grant no.

2012M520933), the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau Youth Projects

(grant no. 20124y147) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the

Central Universities (grant no. 2012KJ016).

References

|

1

|

Choong PF, Mok PL, Cheong SK, Leong CF and

Then KY: Generating neuron-like cells from BM-derived mesenchymal

stromal cells in vitro. Cytotherapy. 9:170–183. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal

RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S and

Marshak DR: Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem

cells. Science. 284:143–147. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xu R, Jiang X, Guo Z, Chen J, Zou Y, Ke Y,

Zhang S, Li Z, Cai Y, Du M, Qin L, Tang Y and Zeng Y: Functional

analysis of neuron-like cells differentiated from neural stem cells

derived from bone marrow stroma cells in vitro. Cell Mol Neurobiol.

28:545–558. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cui X, Chen L, Ren Y, Ji Y, Liu W, Liu J,

Yan Q, Cheng L and Sun YE: Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem

cells in spinal cord injury repair strategies. Biosci Trends.

7:202–208. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kode JA, Mukherjee S, Joglekar MV and

Hardikar AA: Mesenchymal stem cells: immunobiology and role in

immunomodulation and tissue regeneration. Cytotherapy. 11:377–391.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

da Meirelles LS, Fontes AM, Covas DT and

Caplan AI: Mechanisms involved in the therapeutic properties of

mesenchymal stem cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 20:419–427.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Davies OG, Smith AJ, Cooper PR, Shelton RM

and Scheven BA: The effects of cryopreservation on cells isolated

from adipose, bone marrow and dental pulp tissues. Cryobiology.

69:342–347. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Bakhshi T, Zabriskie RC, Bodie S, Kidd S,

Ramin S, Paganessi LA, Gregory SA, Fung HC and Christopherson KW

II: Mesenchymal stem cells from the Wharton’s jelly of umbilical

cord segments provide stromal support for the maintenance of cord

blood hematopoietic stem cells during long-term ex vivo culture.

Transfusion. 48:2638–2644. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Moretti P, Hatlapatka T, Marten D,

Lavrentieva A, Majore I, Hass R and Kasper C: Mesenchymal stromal

cells derived from human umbilical cord tissues: primitive cells

with potential for clinical and tissue engineering applications.

Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 123:29–54. 2010.

|

|

10

|

Lisianyĭ MI: Mesenchymal stem cells and

their immunological properties. Fiziol Zh. 59:126–134. 2013.(In

Ukranian).

|

|

11

|

Yoo KH, Jang IK, Lee MW, Kim HE, Yang MS,

Eom Y, Lee JE, Kim YJ, Yang SK, Jung HL, et al: Comparison of

immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from

adult human tissues. Cell Immunol. 259:150–156. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yang CC, Shih YH, Ko MH, Hsu SY, Cheng H

and Fu YS: Transplantation of human umbilical mesenchymal stem

cells from Wharton’s jelly after complete transection of the rat

spinal cord. PLoS One. 3:e33362008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ma H, Wu Y, Xu Y, Sun L and Zhang X: Human

umbilical mesenchymal stem cells attenuate the progression of focal

segmental glomerulosclerosis. Am J Med Sci. 346:486–493. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG

and Shi S: Postnatal human dental pulp stemcells (DPSCs) in vitro

and in vivo. Proc Natl Acadm Sci USA. 97:13625–13630. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zhao Y, Wang L, Jin Y and Shi S: Fas

ligand regulates the immunomodulatory properties of dental pulp

stem cells. J Dent Res. 91:948–954. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kermani AJ, Fathi F and Mowla SJ:

Characterization and genetic manipulation of human umbilical cord

vein mesenchymal stem cells: potential application in cell-based

gene therapy. Rejuvenation Res. 11:379–386. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bhowmick R and Girotti AW: Cytoprotective

signaling associated with nitric oxide upregulation in tumor cells

subjected to photodynamic therapy-like oxidative stress. Free Radic

Biol Med. 57:39–48. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

18

|

Kikuchi-Taura A, Taguchi A, Kanda T, Inoue

T, Kasahara Y, Hirose H, Sato I, Matsuyama T, Nakagomi T, Yamahara

K, et al: Human umbilical cord provides a significant source of

unexpanded mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy. 14:441–450.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fink KD, Rossignol J, Crane AT, Davis KK,

Bombard MC, Bavar AM, Clerc S, Lowrance SA, Song C, Lescaudron L

and Dunbar GL: Transplantation of umbilical cord-derived

mesenchymal stem cells into the striata of R6/2 mice: behavioral

and neuropathological analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 4:1302013.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

20

|

Trapnell C, Pachter L and Salzberg SL:

TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics.

25:1105–1111. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G,

Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL and Pachter L:

Differential geneand transcript expressionanalysis of RNA-seq

experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 7:562–578. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Baron F and Storb R: Mesenchymal stromal

cells: a new tool against graft-versus-host disease? Biol Blood

Marrow Transplant. 18:822–840. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

23

|

Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I,

Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A,

Prockop DJ and Horwitz E: Minimal criteria for defining multipotent

mesenchymal stromal cells. The international society for cellular

therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 8:315–317. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mangano C, De Rosa A, Desiderio V,

d’Aquino R, Piattelli A, De Francesco F, Tirino V, Mangano F and

Papaccio G: The osteoblastic differentiation of dental pulp stem

cells and bone formation on different titanium surface textures.

Biomaterials. 31:3543–3551. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fukuda S, Foster RG, Porter SB and Pelus

LM: The antiapoptosis protein survivin is associated with cell

cycle entry of normal cord blood CD34(+) cells and modulates cell

cycle and proliferation of mouse hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Blood. 100:2463–2471. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|