Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant cancer of

plasma cells, which represent ~13% of all hematological

malignancies (1), with >80% of

patients with MM developing myeloma bone disease (MBD). MBD is

characterized by severe bone pain, vertebral compression fractures

and pathological fractures, which are caused by osteoclastic bone

resorption and impaired osteoblastic bone formation induced by the

interaction between myeloma cells and the bone marrow

microenvironment. However, the molecular mechanism by which MM

leads to the development of MBD remains to be elucidated.

Genes that are expressed at high levels in the bone

marrow of patients with MM have been identified (2), one of which is macrophage inhibitory

cytokine-1 (MIC-1). MIC-1 belongs to the human transforming growth

factor β superfamily. Also known as growth differentiation

factor-15, placental bone morphogenetic protein, prostate-derived

factor and NSAID-activated gene-1 (3–6),

MIC-1 has multiple functions. In a previous in vitro study,

MIC-1 was shown to inhibit the activation of macrophages (7). MIC-1 may be an important factor in

the development of several types of tumor, including MM (8). In patients with MM, MIC-1 is

expressed at high levels in the mesenchymal stem cells of the bone

marrow, and high levels of MIC-1 in the patients' serum predicts a

poor prognosis (2). MIC-1 may be

involved in osteoclastogenesis; in patients with prostate cancer

with bone metastases, MIC-1 has been found to induce the maturation

of osteoclasts (9). However,

whether MIC-1 is involved in the development of MBD in patients

with MM remains to be elucidated. In present study, in order to

evaluate the effect of target inhibition of MIC-1 in RPMI-8226

cells on osteoclastic differentiation of peripheral blood

mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) and the mechanisms by which MIC-1

contributes to the maturation of osteoclasts, a lentiviral RNAi

system directed toward the MIC-1 gene was designed and constructed

in RPMI-8226 cells. A co-culture system was used in the present

study to determine the role of MIC-1 on osteoclastic

differentiation. The results from the present study offered a

potential strategy for the treatment of MBD in patients with

MM.

Materials and methods

Preparation of the lentiviral vector

bearing MIC-1 short hairpin (sh)RNA

To understand the potential effect of MIC-1 in

RPMI-8226 cells, an MIC-1 shRNA was designed to specifically knock

down the gene expression of MIC-1. The MIC-1 shRNA was designed by

Genechem (Shanghai, China), based on the MIC-1 cDNA sequence

(GenBank accession no. AF019770.1; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/AF019770.1). A

control shRNA encoding a nonspecific shRNA was used as a negative

control. The MIC-1 shRNA and negative control shRNA were

synthesized by Genechem (Shanghai, China). The synthesized

oligonucleotides were designed, synthesized and inserted into a

GV115 vector (GeneChem) to construct a lentiviral vector, according

to the manufacturer's protocol, to generate lentiviral transfer

plasmids: Lv-shRNA, bearing MIC-1 shRNA, and Lv-NC, bearing control

shRNA as a negative control. The control shRNA had no significant

homology to any human gene sequence. The lentiviral vectors were

prepared by transfecting the Lv-shRNA or Lv-NC with packaging

plasmids into 293T cells, as described previously (10).

Cell culture and lentiviral

transduction

The RPMI-8226 cells (Wuhan University, Wuhan, China)

were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 3 days, the RPMI-8226 cells

were transduced with the lentiviral vectors at a multiplicity of

infection of 15 in the presence of 2 µg/ml polybrene

(Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Following incubation at 37°C

for 8 h, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS), and the mRNA and protein levels of MIC-1 in the cells were

measured using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (RT-qPCR) and Western blot analyses, respectively, to

evaluate the viral infection efficiency.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The RNA (4

µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Thermoscript RT-PCR

System reagent (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according

to the manufacturer's protocol, prior for use in qPCR. The qPCR was

performed on an Applied Biosystems PRISM 7300 sequence detection

system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using a

SYBR Green PCR master mix (DRR041A; Takara Bio, Inc., Tokyo,

Japan). A total volume of 20μl, containing 2μl cDNA, 10μl SYBR

Premix Ex Taq, 0.4μl Forward Primer, 0.4μl Reverse Primer, 0.4μl

ROX Reference Dye II and 6.8μl dH2O, was used in the q-PCR

reaction. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The

quantification cycle (Cq) value of each sample was normalized to an

endogenous control, GAPDH. The 2−ΔΔCq method was used to

relatively quantify the mRNA levels of MIC-1 (11). The primer (Genechem) sequences for

human MIC-1 were: Sense 5′-GTTGCGGAAACGCTACGA−3′ and antisense

5′-AACAGAGCCCGGTGAAGG-3′. Primers for the control (GAPDH) were:

Sense 5′-TGACTTCAACAGCGACACCCA-3′ and antisense

5′-CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAA-3′. The qPCR program was as follows: 45

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 45 sec,

followed by 72°C for 10 min.

Isolation and culture of PBMNCs

The PBMNCs were isolated, as described previously

(10) from the peripheral blood of

healthy donors, who had provided written informed consent. The

present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian

Medical University. A total of 10 ml human blood was obtaubed from

peripheral blood samples, and was mixed with 10 ml lymphocyte

separation medium (Hao Yang Biological Manufacture Co. Ltd.,

Tianjin, China) in a centrifuge tube. The mixture was centrifuged

at 2,000 × g at room temperature for 20 mins. Following washing

with PBS once and α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM) twice, the

nucleated cells were grown in α-MEM supplemented with 10% (v/v)

fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 ng/ml macrophage-colony-stimulating

factor (M-CSF; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA) and 100 ng/ml

receptor activator of nuclear factor-кB ligand (RANKL; Peprotech)

at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified air. The medium was replaced every 3

days.

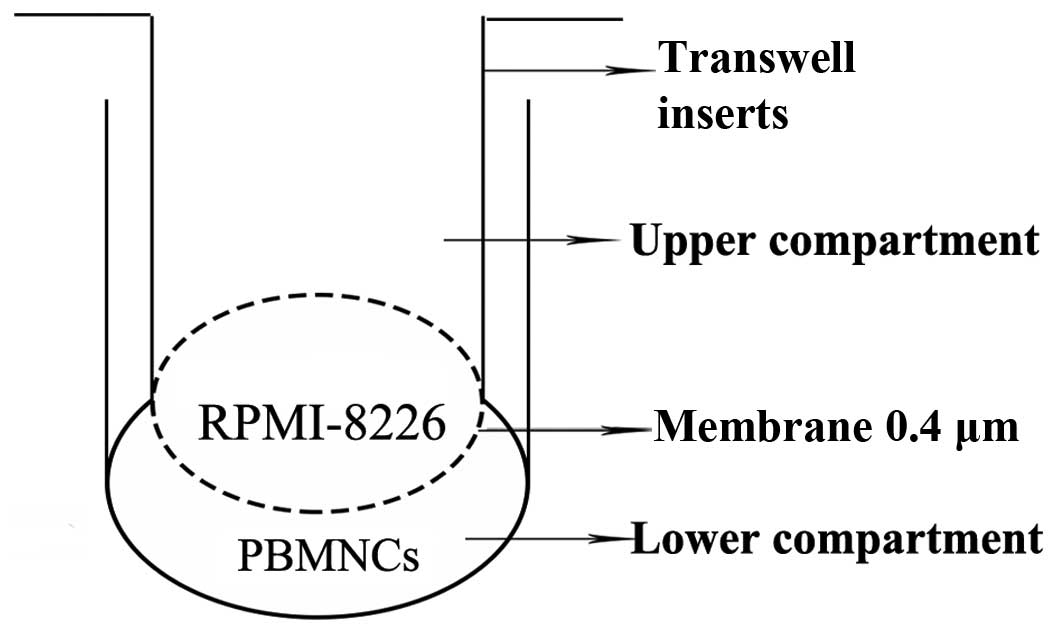

Co-culture system

To investigate the potential effect of MIC-1 on the

differentiation capacity of the PBMNCs, a Transwell insert system

(Corning, Inc., New York, NY, USA) was used (Fig. 1) to co-culture the PBMNCs

(1×106 cells/well) and the RPMI-8226 cells

(2×103 cells/well) transduced with Lv-shRNA or Lv-NC.

The PBMNCs were seeded into the lower compartment following

placement of a cover glass and dentine slides on the bottom. The

cells were cultured in α-MEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) containing 10% FBS, 50 ng/ml M-CSF and 100 ng/ml RANKL. After

12 h of culture at 37°C in 5% CO2, the non-adherent

cells in the culture were removed by gently washing with fresh

medium; the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with Lv-shRNA or Lv-NC were

cultured in the upper compartment. RPMI-8226 cells without viral

transduction were also used as a control.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

(TRAP) staining and resorption pit formation assay

The PBMNCs (1×106 cells/well), which were

cultured on cover glasses and dentine slides for 14 or 21 days,

were stained using a leukocyte acid phosphatase kit

(Sigma-Aldrich), and the cells were then counterstained with

hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich), as previously described (10). A mature osteoclast was identified

as a cell with at least three TRAP-positive nuclei. To determine

the number of mature osteoclasts in each group, 10 randomly

selected fields from the three cultures in each group were examined

under a microscope (BX43; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For the

resorption pit assay, the cells on dentine slices were stained with

toluidine blue and then scanned under a microscope (BX43; Olympus).

Osteoclastic bone resorption was measured, based on the area of

resorption pits per field from three cultures in each group.

Western blot analysis

The PBMNCs were harvested after co-culture for 14

days for protein analysis. The protein extracts from these cells

were separated by 6–15% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and then

transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) membranes. Following blocking

with Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween (TBST) containing 5%

non-fat milk at 4°C overnight, the membranes were incubated with

the following antibodies diluted in TBST for 2 h at 4°C: Rabbit

anti-RANKL (cat no. sc-9073; 1:2,000), rabbit anti–GAPDH (cat no.

sc-25778; 1:2,000), rabbit anti-c-fos (cat no. sc-52, 1:2,000),

rabbit anti-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (c-JNK; cat no. sc-572;

1:2,000), rabbit anti-p-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (p-c-JNK; cat no.

sc-135642; 1:2,000), rabbit anti-P-38 (cat no. sc-535; 1:2,000),

rabbit anti-p-P-38 (cat no. sc-101759; 1:2,000), rabbit anti-c-jun

(cat no. sc-44; 1:2,000), rabbit anti-p-c-jun (cat no. sc-7980-R;

1:2,000), all purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa

Cruz, CA, USA), and rabbit anti-extracellular signal-regulated

kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2; cat no. 4695; 1:2,000; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) or rabbit anti- p-Erk1/2 (cat

no. 4376; 1:2,000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

Following washing three times with TBST (pH 7.5), the membranes

were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit secondary antibody (cat no. bs-0295G; 1:1,000; Beijing

Biosynthesis Biotechnology, Beijing, China) for 1 h at room

temperature. The membranes were washed three times with TBST (pH

7.5). The resulting protein bands were visualized using an enhanced

chemiluminescence reagent kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0

software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data are expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance and

Student-Newman-Keuls analysis were used to evaluate the statistical

significance of differences among the groups. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

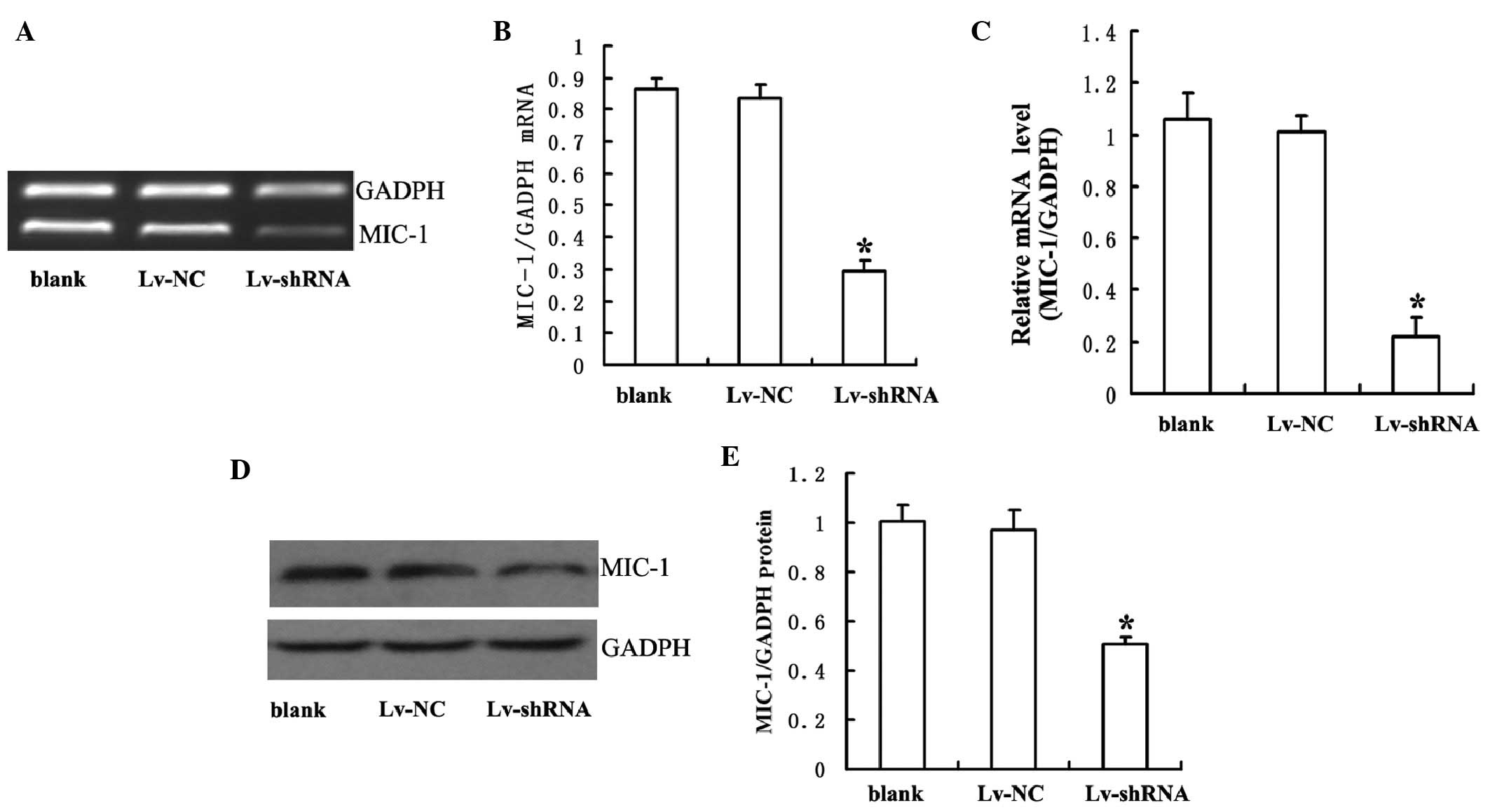

Expression of MIC-1 in RPMI-8226

cells

To determine whether MIC-1 shRNA successfully

knocked down the gene expression of MIC-1, the present study

prepared lentiviral vectors bearing either MIC-1 shRNA (Lv-shRNA)

or non-specific sequence (Lv-NC). Following transduction with

Lv-shRNA or Lv-NC for 14 days, the RPMI-8226 cells were harvested

and the expression levels of MIC-1 in these cells were analyzed

using RT-qPCR and Western blot analyses. As shown in Fig. 2, the mRNA and protein levels of

MIC-1 were significantly lower in the cells transduced with

Lv-shRNA, compared with those in the cells transduced with Lv-NC or

those without viral tranduction.

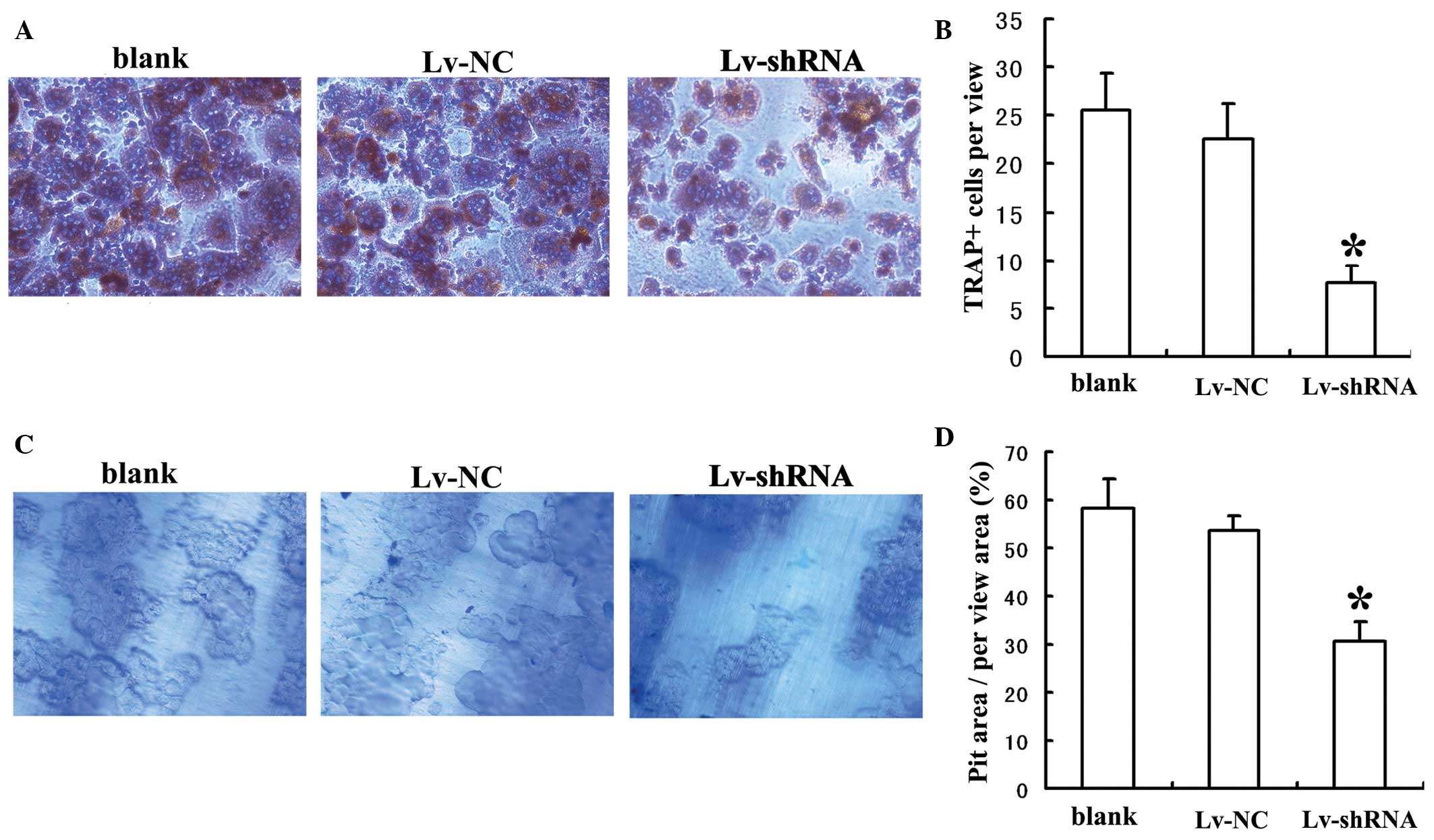

MIC-1 is essential for the

osteoclastic differentiation of PBMNCs

To investigate the role of MIC-1 in the osteoclastic

differentiation of PBMNCs, the PBMNCs were stained for TRAP

following co-culture with RPMI-8226 cells for 14 days. The number

of TRAP(+) cells was significantly lower when the PBMNCs were

co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with Lv-shRNA,

compared with when they were co-cultured with RPMI-8226 cells

transduced with Lv-NC or without viral transduction (Fig. 3A and B). To investigate the role of

MIC-1 in bone resorption by differentiated PBMNCs, the PBMNCs were

stained with toluidine blue following co-culture with RPMI-8226

cells for 14 days. The percentage of pit area within a randomly

selected area was significantly lower when the PBMNCs were

co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with Lv-shRNA,

compared with those co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced

with Lv-NC or without viral transduction (Fig. 3C and D). Taken together, these

results suggested that MIC-1 was required for the osteoclastic

differentiation and bone resorption activities of PBMNCs.

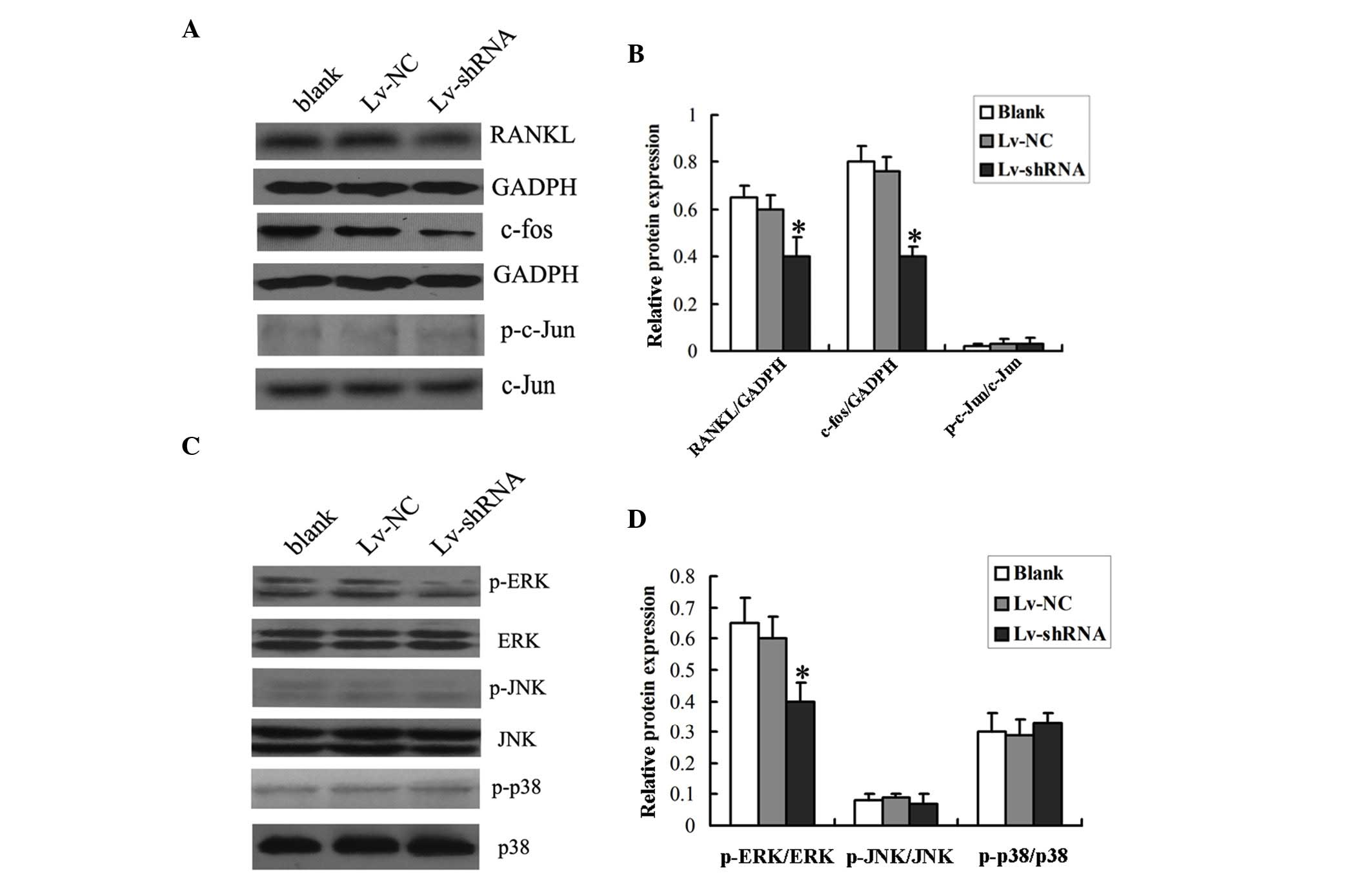

To confirm the role of MIC-1 in the osteoclastic

differentiation of PBMNCs, the present study examined whether the

expression of the osteoclast-specific gene, RANKL, was altered by

the decreased expression of MIC-1. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, the protein level of RANKL

in the PBMNCs was significantly lower when the cells were

co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with Lv-shRNA,

compared with those co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced

with Lv-NC or without viral transduction.

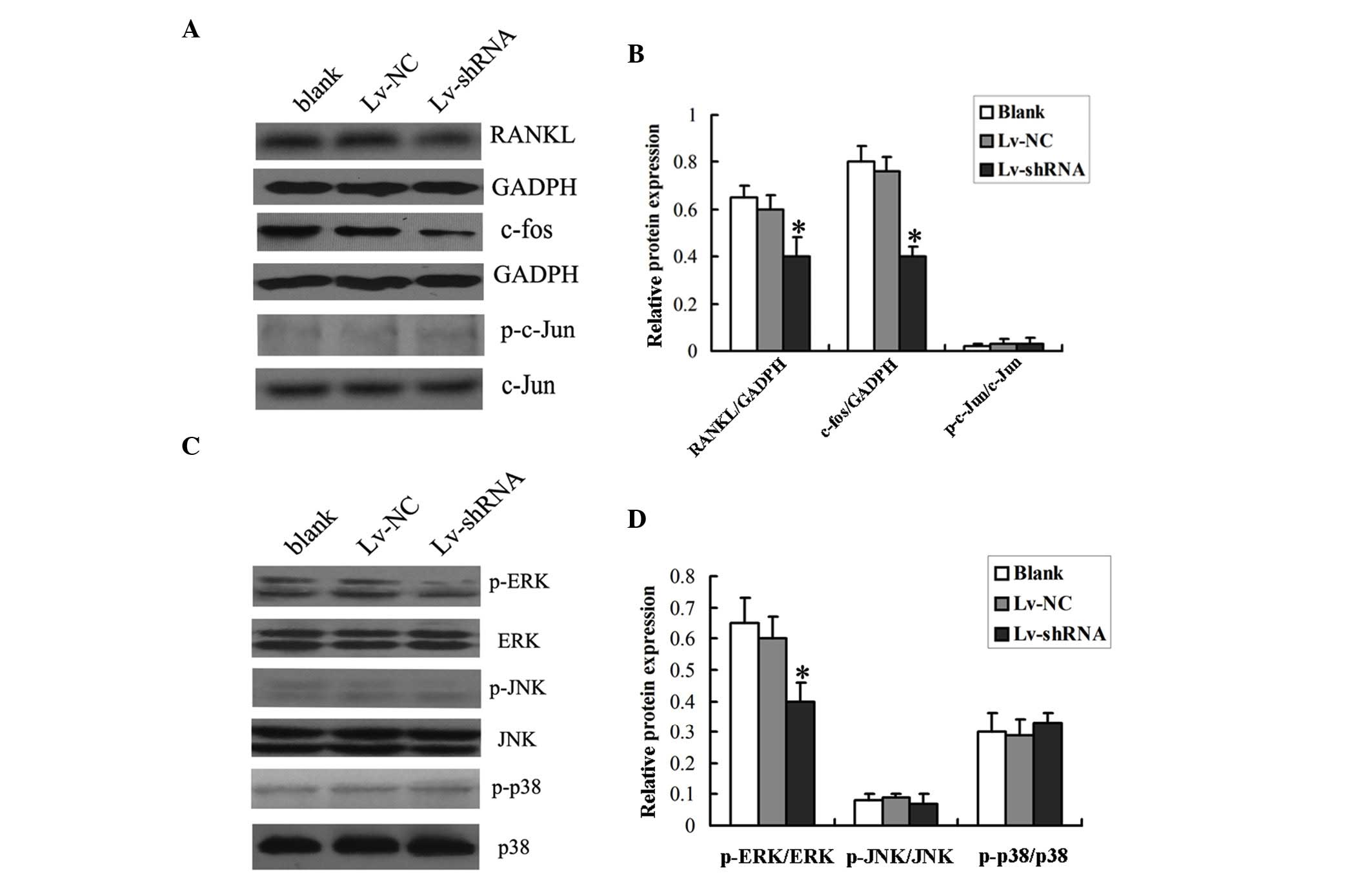

| Figure 4.Expression of RANKL and the

phosphorylation status of the Erk1/2 signaling pathway in PBMNCs.

PBMNCs were co-cultured with RPMI-8226 cells infected with Lv-shRNA

or Lv-NC for 14 days prior to harvesting for the analysis of the

expression levels of (A) RANKL and c-fos, and the phosphorylation

status of c-jun. GADPH was used as internal control. (B)

Densitometric analysis of the western blot was performed. (C) The

phosphorylation status of Erk1/2, p-38 and c-JNK was determined by

western blotting. (D) Densitometric analysis of the western blot

was performed. The data are expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation (*P<0.05 vs. Lv-NC group or Blank group). Blank, cells

without viral transduction; PBMNCs, peripheral blood mononuclear

cells; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control; RANKL,

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand; p-ERK,

phosphorylated-extracellular signal-regulated kinase; t-ERK, total

ERK; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase. |

Subsequently, the present study investigated which

signaling pathway was activated by RANKL by analyzing the

phosphorylation status of the ERK1/2, c-JNK and p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) proteins using Western blot

analysis. It was found that the protein levels of phosphorylated

Erk1/2, but not those of c-JNK or p38, were significantly lower in

the PBMNCs co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with

Lv-shRNA, compared with those co-cultured with RPMI-8226 cells

transduced with Lv-NC or without viral transduction (Fig. 4C and D), indicating that the

MCI-1-induced increase in RANKL may activate the Erk1/2

pathway.

The present study then investigated whether c-fos

and c-jun, important downstream molecules of ERK1/2, were involved

in the differentiation of osteoclasts by analyzing the

phosphorylation status of c-fos and c-jun using Western blot

analysis. It was found that the protein levels of total c-fos were

markedly reduced in the PBMNCs co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells

transduced with Lv-shRNA, compared with those co-cultured with the

RPMI-8226 cells transduced with Lv-NC or without viral

transduction. However, no changes were observed in the protein

levels of total c-jun or phosphorylated c-jun in the PBMNCs

co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with either

Lv-shRNA or Lv-NC (Fig. 4C and D).

Taken together, these results suggested that MIC-1 regulated the

osteoclastic differentiation and bone resorption activities of the

PBMNCs via the Erk1/2 signaling pathway.

Discussion

In the present study, the role of MIC-1 in the

osteoclastic differentiation of PBMNCs was examined. A co-culture

system was used, in which PBMNCs co-cultured with RPMI-8226 cells

were induced to differentiate into osteoclasts and to resorb bone.

To knock down the expression of MIC-1 in the RPMI-8226 cells, a

lentiviral vector was used to deliver the MIC-1 shRNA to the

RPMI-8226 cells. It was found that MIC-1 shRNA efficiently

decreased the expression of MIC-1 in the RPMI-8226 cells (Fig. 2). The present study then

demonstrated that reduced expression of MIC-1 inhibited the

osteoclastic differentiation of PBMNCs (Fig. 3). Finally, it was shown that the

expression of the osteoclast-specific gene, RANKL, and the levels

of dephosphorylated Erk1/2 were decreased in those PBMNCs, which

were co-cultured with the RPMI-8226 cells transduced with Lv-shRNA

(Fig. 4A and C). These results led

to the conclusion that MIC-1 promoted osteoclastic differentiation

of PBMNCs through inhibition of the RANKL-Erk1/2 signaling

pathway.

Patients with MM often develop MBD with osteoclastic

differentiation, induced by cytokines and other soluble factors in

the bone marrow (12). In the bone

marrow of patients with MM, MIC-1 is expressed at high levels

(2). It has been suggested that

MIC-1 may be involved in the regulation of osteoclastogenesis

(13,14). The results of the study

demonstrated that MIC-1 was required in order for RPMI-8226 to

induce osteoclastic differentiation of the PBMNCs (Figs. 3 and 4), supporting the role of MCI-1 in the

development of MBD in patients with MM.

The osteoclast-specific marker gene, RANKL, is

involved in MCI-1 stimulated osteoclastic differentiation. Binding

to its receptor RANK, RANKL stimulates the osteoclastic

differentiation of monocyte macrophages and the maturation of

osteoclasts (15). In

RANKL-deficient mice, severe osteopetrosis and a defect in tooth

eruption have been observed (16).

In patients with MM, RANKL has been shown to be involved

osteoclastic differentiation (17–19).

In the present study, it was shown that the expression of RANKL in

the PBMNCs was reduced when the expression of MIC-1 in the

co-cultured RPMI-8226 cells was knocked down (Fig. 4). RANKL binds to RANK and activates

several MAPK signaling pathways (20), including the Erk1/2, JNK and P-38

pathways (21). The present study

demonstrated that reduced expression of MIC-1 in the RPMI-8226

cells appeared to decrease the phosphorylation of Erk1/2, but not

JNK or P-38, indicating the involvement of the Erk1/2 pathway in

MIC-1-induced osteoclastic differentiation of PBMNCs (22,23).

Consistent with this observation, the expression levels of c-fos

and c-jun, downstream molecules of the Erk1/2 signaling pathway in

PBMNCs, were also decreased when the expression of MCI-1 in the

co-cultured RPMI-8226 cells was reduced.

In conclusion, the present study found that MIC-1

was involved in the development of MBD in patients with MM by

promoting the osteoclastic differentiation of PBMNCs by activating

the RANKL-Erk1/2 signaling pathway. Thus, MIC-1 may offer potential

as a target gene in the development of strategies to treat MM.

References

|

1

|

Kyle RA and Rajkumar SV: Criteria for

diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of

multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 23:3–9. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Corre J, Mahtouk K, Attal M, Gadelorge M,

Huynh A, Fleury-Cappellesso S, Danho C, Laharrague P, Klein B, Rème

T and Bourin P: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells are abnormal in

multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 21:1079–1088. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hromas R, Hufford M, Sutton J, Xu D, Li Y

and Lu L: PLAB, a novel placental bone morphogenetic protein.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1354:40–44. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Paralkar VM, Vail AL, Grasser WA, Brown

TA, Xu H, Vukicevic S, Ke HZ, Qi H, Owen TA and Thompson DD:

Cloning and characterization of a novel member of the transforming

growth factor-beta/bone morphogenetic protein family. J Biol Chem.

273:13760–13767. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Böttner M, Suter-Crazzolara C, Schober A

and Unsicker K: Expression of a novel member of the TGF-beta

superfamily, growth/differentiation factor-15/macrophage-inhibiting

cytokine-1 (GDF-15/MIC-1) in adult rat tissues. Cell Tissue Res.

297:103–110. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Baek SJ, Horowitz JM and Eling TE:

Molecular cloning and characterization of human nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drug-activated gene promoter. Basal transcription

is mediated by Sp1 and Sp3. J Biol Chem. 276:33384–33392. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Bootcov MR, Bauskin AR, Valenzuela SM,

Moore AG, Bansal M, He XY, Zhang HP, Donnellan M, Mahler S, Pryor

K, et al: Mic-1, a novel macrophage inhibitory cytokine, is a

divergent member of the TGF-beta superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 94:11514–11519. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tarkun P, Atesoglu E Birtas, Mehtap O,

Musul MM and Hacihanefioglu A: Serum growth differentiation factor

15 levels in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Acta

Haematol. 131:173–178. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wakchoure S, Swain TM, Hentunen TA,

Bauskin AR, Brown DA, Breit SN, Vuopala KS, Harris KW and Selander

KS: Expression of macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 in prostate

cancer bone metastases induces osteoclast activation and weight

loss. Prostate. 69:652–661. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zeng Z, Zhang C and Chen J:

Lentivirus-mediated RNA interference of DC-STAMP expression

inhibits the fusion and resorptive activity of human osteoclasts. J

Bone Miner Metab. 31:409–416. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Roodman GD: Pathogenesis of myeloma bone

disease. Leukemia. 23:435–441. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Khosla S: Minireview: The OPG/RANKL/RANK

system. Endocrinology. 142:5050–5055. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sung B, Prasad S, Yadav VR, Gupta SC,

Reuter S, Yamamoto N, Murakami A and Aggarwal BB: RANKL signaling

and osteoclastogenesis is negatively regulated by cardamonin. PLoS

One. 8:e641182013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ,

Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S,

et al: Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates

osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 93:165–176. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL,

Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G,

Itie A, et al: OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis,

lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature.

397:315–323. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Schramek D, Leibbrandt A, Sigl V, Kenner

L, Pospisilik JA, Lee HJ, Hanada R, Joshi PA, Aliprantis A,

Glimcher L, et al: Osteoclast differentiation factor RANKL controls

development of progestin-driven mammary cancer. Nature. 468:98–102.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sung B, Oyajobi B and Aggarwal BB:

Plumbagin inhibits osteoclastogenesis and reduces human breast

cancer-induced osteolytic bone metastasis in mice through

suppression of RANKL signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 11:350–359. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ai LS, Sun CY, Zhang L, Zhou SC, Chu ZB,

Qin Y, Wang YD, Zeng W, Yan H, Guo T, et al: Inhibition of BDNF in

multiple myeloma blocks osteoclastogenesis via down-regulated

stroma-derived RANKL expression both in vitro and in vivo. PLoS

One. 7:e462872012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wada T, Nakashima T, Hiroshi N and

Penninger JM: RANKL-RANK signaling in osteoclastogenesis and bone

disease. Trends Mol Med. 12:17–25. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Huang P, Han J and Hui L: MAPK signaling

in inflammation-associated cancer development. Protein Cell.

1:218–226. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhang W and Liu HT: MAPK signal pathways

in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell

Res. 12:9–18. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Feng X: RANKing intracellular signaling in

osteoclasts. IUBMB Life. 57:389–395. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|