Introduction

Due to the rapid development of stem cell

transplantation in preclinical research and clinical trials over

the last decade, stem cell replacement therapies have become modern

therapeutic approaches (1).

Similar to bone-marrow stromal cells, adipose-derived stem cells

(ADSCs) have the ability to differentiate into various types of

cell lineage, including adipogenic, osteogenic, myogenic and

chondrogenic cells (2,3). In addition, the yield of mesenchymal

stem cells (MSCs) from adipose tissue is 100–500 fold that from

bone marrow (4). The unique

biology of autologous ADSCs, including being easily expanded,

immune-privileged and capable of long-term transgene expression

following multiple stages of differentiation, demonstrates their

potential as a gene delivery vehicle (5–7).

The endothelial differentiation of ADSCs serves an

essential role in vascular development, function and disease

(8). Numerous peptide growth

factors promote angiogenesis by promoting differentiation, and

enhancing endothelial cell proliferation, migration and capillary

network stability (9).

The knockdown of microRNA-126 (miR-126) in zebrafish

in vivo resulted in the loss of vascular integrity and

hemorrhage during embryonic development, and targeted deletion of

miR-126 in mice caused delayed angiogenic sprouting, widespread

hemorrhaging and partial embryonic lethality (10–12).

These vascular abnormalities may be attributed to diminished

angiogenic growth factor signaling, resulting in reduced

endothelial cell differentiation, growth, sprouting and adhesion

(13–16). This evidence indicates that miR-126

may be involved in multiple aspects of fundamental biological

processes, including angiogenesis. However, the role of miR-126 in

mediating the differentiation of ADSCs to endothelial cells has not

been demonstrated.

The present study focused on the association between

miR-126 and the endothelial differentiation of ADSCs.

Materials and methods

Cell growth curve and endothelial

differentiation of ADSCs

ADSCs were purchased from the American Type Culture

Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in α-Minimum Essential

Medium (α-MEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Equal

numbers (2×104) of passage (p)1, 3, 6 and 8 cells were

plated and cultured. Cells images were obtained at ×100

magnification using a phase-contrast inverted light microscope.

Cells were harvested each day for 8 days. The total number of cells

was counted in each plate using a hemocytometer. The cell growth

curve was drawn by plotting the mean cell number of each plate

against the culture time. For endothelial differentiation, ADSCs

were cultured in Endothelial Cell Growth Medium-2 (EGM-2; Lonza,

Basel, Switzerland). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

(HUVECs; CRL-1730; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured

in F-12K medium (30–2004; American Type Culture Collection) with

10% fetal bovine serum (30–2020; American Type Culture Collection),

0.05 mg/ml ECGS (no. 354006, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ,

USA) and 0.1 mg/ml heparin (#H3393; Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany).

Transfection

The hsa-miR-126-3p inhibitor (CGC AUU AUU ACU CAC

GGU ACGA), hsa-miR-126-3p mimic (5–3′, UCG UAC CGU GAG UAA UAA

UGCG; 3–5′, AGC AUG GCA CUC AUU AUU ACGC;), and their negative

controls (NCs) (mimic NC, 5–3′, UCA CAA CCU CCU AGA AAG AGU AGA;

3–5′, AGU GUU GGA GGA UCU UUC UCA UCU; inhibitor NC, UCU ACU CUU

UCU AGG AGG UUG UGA; all Biomics Biotechnologies, Nantong, China)

were diluted to a final concentration of 50 nM with RNase-free

H2O. ADSCs were transfected respectively with these

oligonucleotides using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), following the manufacturer's protocol. At

each time point (days 1–8), cells were harvested for further

analysis. The efficiency of transfection was determined using

aCy3-short interfering RNA (Cy3-siRNA) transfection control

(Biomics Biotechnologies). The inhibition and overexpression

efficiencies were determined by comparing with the NCs.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were uninduced in α-MEM or induced in EGM-2

for 7–14 days, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), blocked with

10% normal goat serum (50062Z; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for

10 min at room temperature and incubated with one of three primary

antibodies: Rabbit anti-human cluster of differentiation (CD)31

(1:50; 11265-AP), von Willebrand factor (vWF) (1:50; 11778-1-AP) or

endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (1:50; 20116-1-AP) (all

from Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) at 4°C overnight.

Following incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate

(FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (CW0114S, 1:100; CWBiotech,

Beijing, China) for 3 h at room temperature, the cells were

counterstained by incubation with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA).

Images were obtained at magnification ×200 using a phase contrast

fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA and miRNA were isolated using a miRNeasy

Mini kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). Synthesis of

complementary DNA from mRNA and miRNA was performed using a

PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) or a

miRcute miRNA First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Tiangen Biotech Co.,

Ltd., Beijing, China), respectively. RT-qPCR analysis of mRNA and

miRNA was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara

Bio, Inc.) or a miRcute miRNA qPCR Detection kit (SYBR Green)

(Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.), respectively. Amplification data was

recorded using an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The PCR analysis of

miR-126 consisted of 38 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1

min, following an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 10 min. The

expression level of miR-126 was normalized to U6 small nuclear RNA,

and the expression levels of CD31, vWF and eNOS mRNA were

normalized to GAPDH. The primers used are presented in Table I. The results were subjected to

melting curve analysis, and the data were analyzed using the

2−ΔΔCq method (17).

| Table I.Primers used in the present study. |

Table I.

Primers used in the present study.

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|

| CD31 | F,

TGTATTTCAAGACCTCTGTGCACTT |

|

| R,

TTAGCCTGAGGAATTGCTGTGTT |

| vWF | F,

TAAGTCTGAAGTAGAGGTGG |

|

| R,

AGAGCAGCAGGAGCACTGGT |

| eNOS | F,

CAGTGTCCAACATGCTGCTGGAAATTG |

|

| R,

TAAAGGAGGTCTTCTTCCTGGTGATGCC |

| GAPDH | F,

ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC |

|

| R,

TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA |

| miR-126-3p |

RT,CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAGCGCATTAT |

|

| F,

ACACTCCAGCTGGGTCGTACCGTGAGTA |

|

| R,

CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGT |

| U6 | RT,

CAAAATATGGAACGCTTC |

|

| F,

GTGCTCGCTTCGGCAGC |

|

| R,

CAAAATATGGAACGCTTC |

Western blot analysis

Confluent cells were removed by scraping, lysed in

mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with the protease inhibitor phenylmethylsulfonyl

fluoride, and quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay. Proteins

(20 µg/lane) were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred

onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Following blocking in 5%

non-fat dried milk and TBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 2 h, the

blots were incubated with a rabbit anti-human CD31 (1:500;

11265-AP), vWF (1:500; 11778-1-AP) or eNOS (1:500; 20116-1-AP) (all

from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd., Cambridge, MA, USA) overnight at

4°C. GAPDH (1:3,000; sc-47724; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.,

Dallas, TX, USA) was used as an internal control. Subsequent to

washing with TBST, the blots were incubated with HRP-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit IgG (CW0103S, 1:2,000; CWBiotech) at room

temperature for 1 h and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence

(GE Health care Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Image band area

and density were estimated using Quantity One 4.6.2 (Bio-Rad

Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated three times

independently. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way

analysis of variance test and SPSS software (version 19.0; IBM

SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

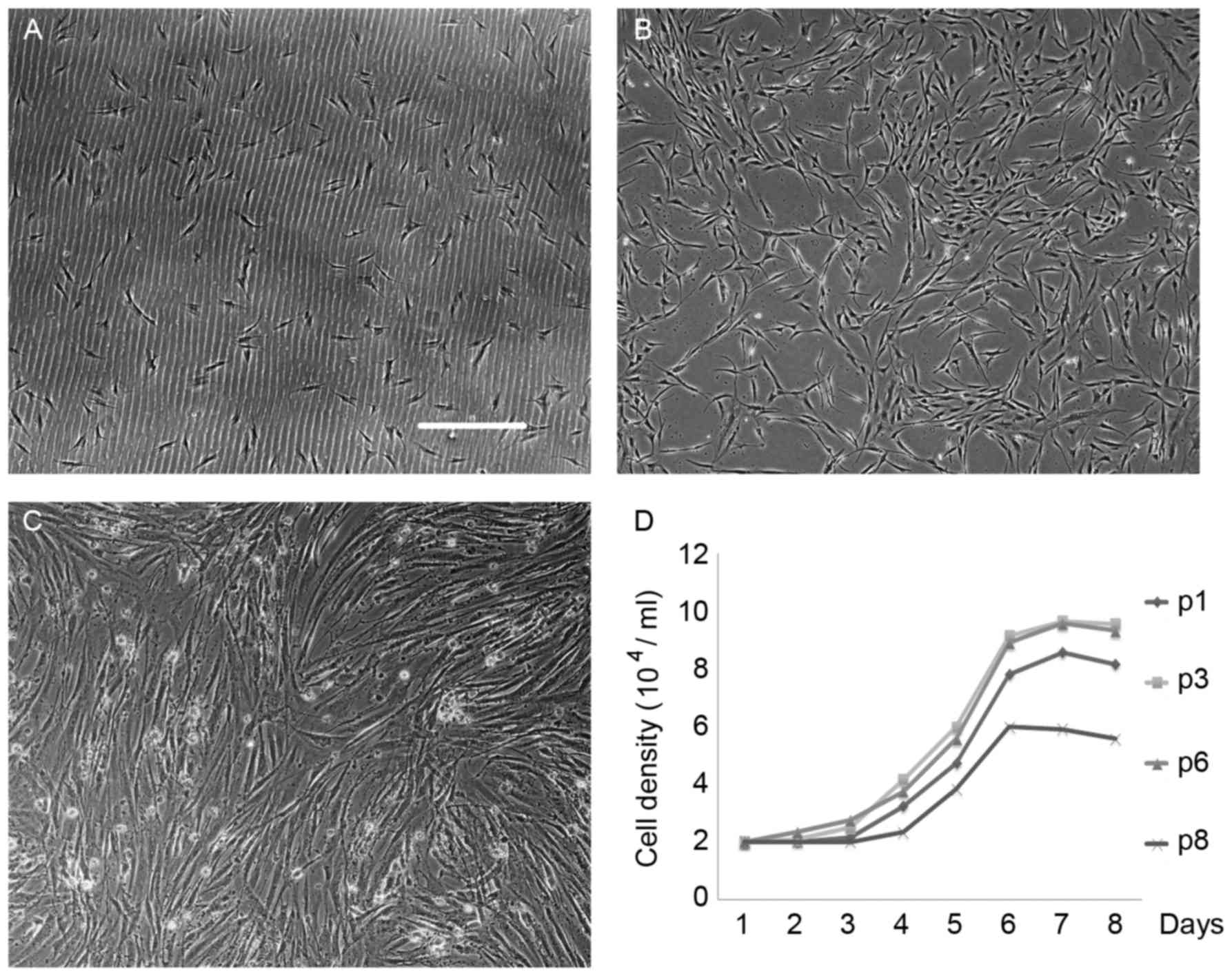

Morphological features of cultured

ADSCs

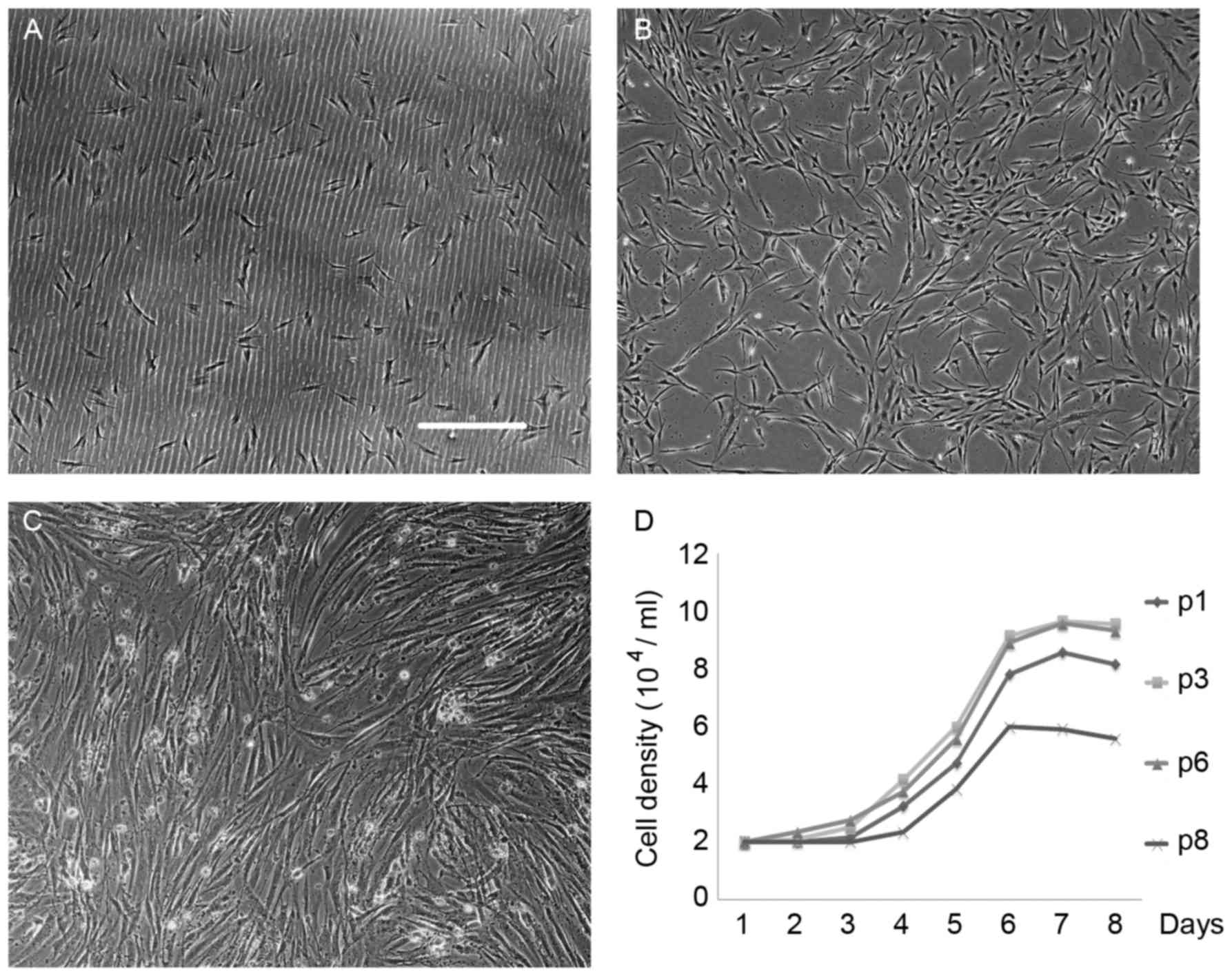

The ADSCs attached to the culture dish surface

exhibited a typical fibroblast-like morphology. The cells were

maintained in culture with no sign of senescence or differentiation

following repeated subculturing to p6 (Fig. 1A-C). In order to investigate

whether passages affect cell growth, the number of cells was

recorded every day for 8 days and compared with the cell growth

curve of p1, 3, 6 and 8. Following an initial lag or stationary

period (day 1), the cells expanded rapidly in a logarithmic manner

until a plateau was reached (day 6). However, the ADSCs exhibited

markedly more rapid growth at p3 and 6 (Fig. 1D).

| Figure 1.Biological characteristics of ADSCs.

(A) The majority of cells were adherent and appeared round in

morphology 24 h following passage. Magnification, ×100; scale bar,

200 µm. (B) After 3 days, the adherent cells in complete medium

became active, proliferated quickly, formed processes, and expanded

to generate small and large colonies. (C) 6 days later, the cells

reached 80% confluence. Cells that attached to the culture dish

surface exhibited a typical fibroblast-like morphology. (D) The

growth of ADSCs was slow and limited to the first 24 h.

Representative growth curves of ADSCs in their logarithmic phase

after day 3 are presented. A marked inhibition of cell growth was

observed in both p1and 8 compared with p3 and 6. Growth curves of

p3 were similar to the p6. Cells grown at p3 and 6 exhibited

increased growth rates, shorter lag-phase periods and higher cell

concentrations, compared with p1 and 8 (each point represents the

number of cells against time). ADSCs, adipose-derived stem cells;

p, passage. |

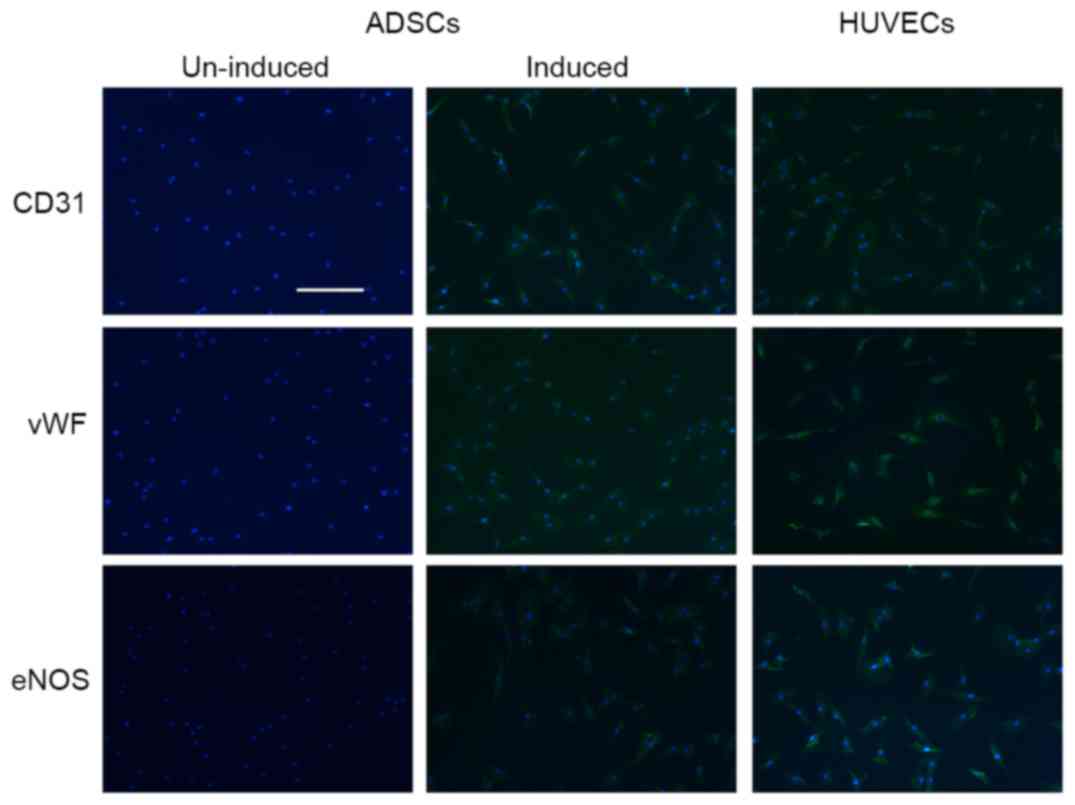

Endothelial phenotype during

endothelial differentiation in ADSCs

ADSCs were subjected to incubation in EGM-2 to

stimulate endothelial differentiation. When cultured in medium with

endothelial cell growth supplement, ADSCs expressed

endothelial-specific markers, including CD31, vWF and eNOS

(Fig. 2). These endothelial

markers were rapidly upregulated during differentiation and

remained elevated 14 days post-differentiation (data not

shown).

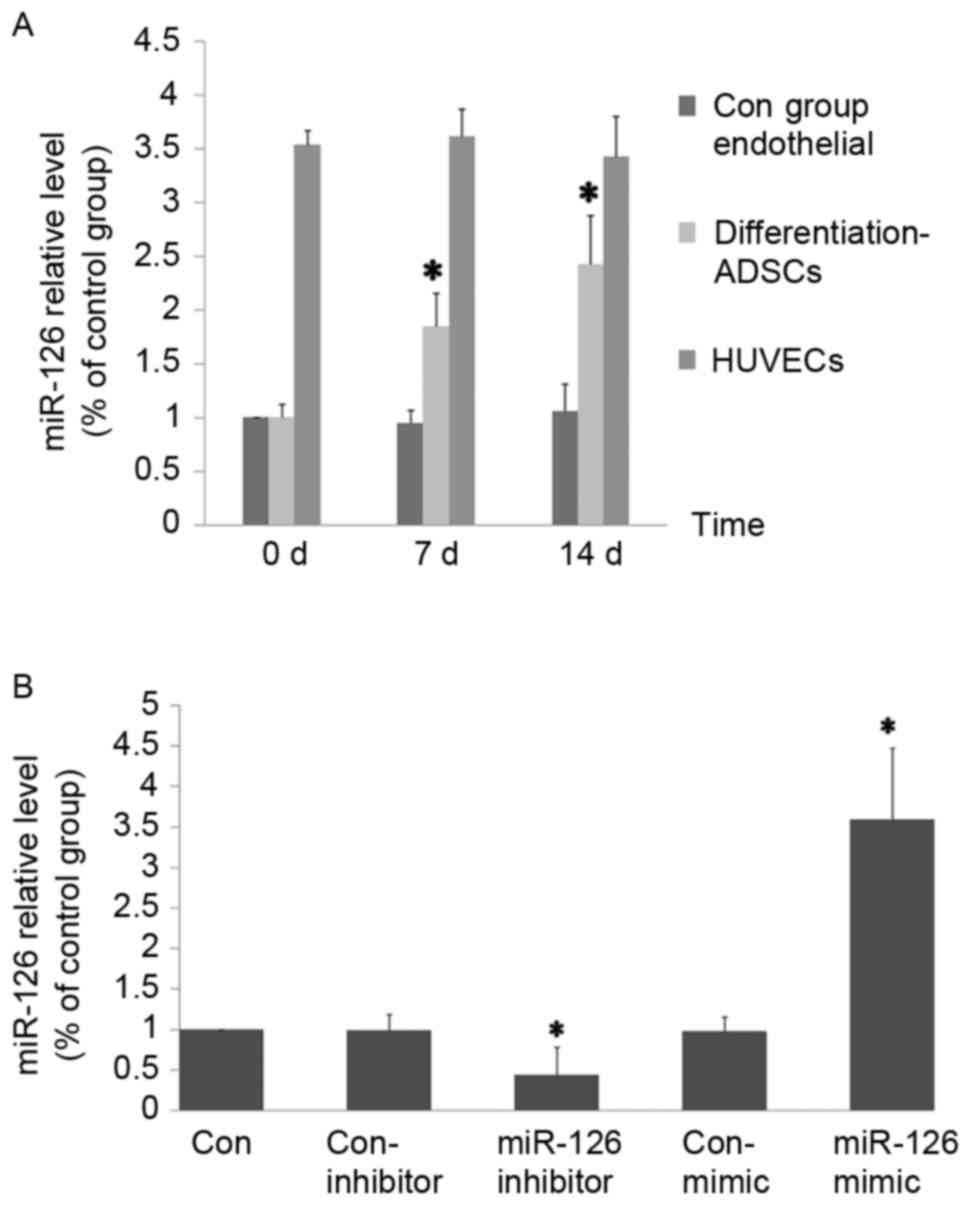

Differential expression of miR-126

during endothelial differentiation of ADSCs

The non-induced and endothelial-induced ADSCs were

harvested on days 0, 7 and 14, and analyzed for miR-126 level using

RT-qPCR analysis, to determine the expression of miR-126 at the

different stages of endothelial differentiation. It was identified

that the expression of miR-126 was enriched in HUVECs and markedly

increased during the endothelial differentiation of ADSCs in a

time-dependent manner (Fig.

3A).

Transfection of ADSCs

In order to study the effect of miR-126 in the

endothelial differentiation of ADSCs, a miR-126 overexpression and

inhibition model was established. After 24 h, transfection

efficiency was detected by Cy3-siRNA transfection control

(siR-Rib). Following transfection with miR-126 mimic or inhibitor

for 3 days, the expression of miR-126 was detected to assess the

efficiency of overexpression and inhibition (Fig. 3B).

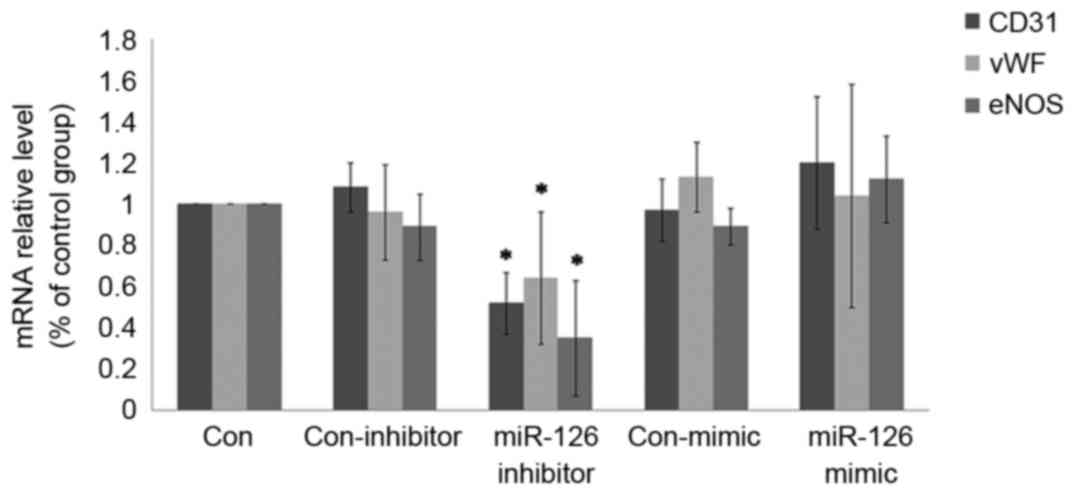

miR-126 modulates the endothelial

phenotype of ADSCs

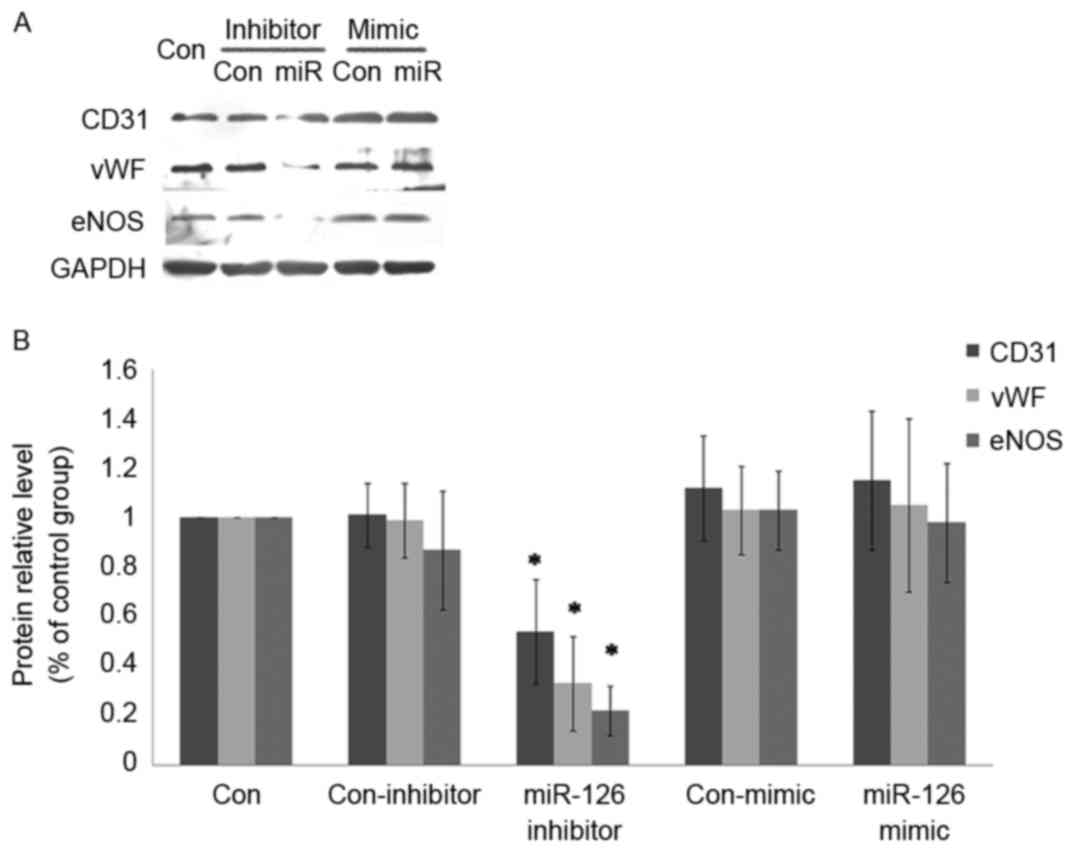

The expression of CD31, vWF and eNOS largely

mirrored that of endothelial markers during endothelialization. The

expression of these markers was decreased by miR-126 inhibitor

transfection during endothelial differentiation at the mRNA

(Fig. 4) and protein level

(Fig. 5). In addition, ADSCs with

miR-126 overexpression were generated through transfection of a

miR-126 mimic. It was identified that the expression of endothelial

markers was not notably affected by miR-126 overexpression.

Discussion

ADSCs may be easily harvested from lipoaspirate and

the extraction maybe less invasive and less expensive compared with

extraction from bone marrow. Additionally, ADSCs have a

significantly shorter doubling time when expanded in vitro

(18). In the present study, ADSCs

of p3-6were used for the experiments and it was observed that the

majority of the cells exhibited typical fibroblastoid morphology,

expressed MSC surface markers, and demonstrated the capability for

multipotency (data not shown). These intrinsic characteristics and

advantages make ADSCs an ideal stem cell source for the present

study and future cell-based tissue engineering and therapies

(19,20).

In the present study, expression analyses revealed

an abundant level of miR-126 in HUVECs and identified miR-126 as

one of the miRs known to be specifically expressed in the

endothelial cell lineage. Expression of miR-126 gradually increased

during ADSC endothelial differentiation, and expression was marked

when endothelial markers were expressed. Endothelial

differentiation markers (CD31, vWF and eNOS) were used to evaluate

the differentiation capability of ADSCs. The results of the present

study suggest that miR-126 may be involved in the directional

differentiation of ADSCs into vascular endothelial cells, and may

promote the progress of the differentiation.

Due to the high expression of miR-126 in HUVECs, and

the increased expression during the endothelial differentiation of

ADSCs, the potential role of this miR in the regulation of

differentiation towards the endothelial lineage was investigated.

In order to confirm the role of miR-126 in the endothelial

differentiation of ADSCs, down- and up-regulation of miR-126

expression was achieved through transfection withmiR-126 inhibitor

and mimic, respectively. As a result of miR-126 inhibition in ADSCs

undergoing the endothelial differentiation, diminished mRNA

expression of endothelial cell markers was observed. These results

demonstrated that the downregulation of miR-126 may exhibit a

negative effect on endothelial differentiation. By contrast, the

overexpression of miR-126 did not improve the expression levels of

endothelial markers. The results of the present study suggest that

while miR-126 is enriched in vascular endothelial cells, and is

essential to endothelial differentiation, it is not sufficient to

promote the differentiation of ADSCs towards an endothelial

phenotype.

Previous research has demonstrated that miR-126

serves an essential role in stem cell differentiation (21) and angiogenesis. However, the

mechanism remains unknown and there is a lack of consistency

between studies. It is difficult to connect the physiological

functions of miR-126 in vasculature to its functions in tumor. It

has been established that angiogenesis represents one of the key

features in the pathogenesis of cancer (22), but little is known about the role

of miR-126 in tumor neoangiogenesis. The present study suggests

that miR-126 may have a supportive role in the progression of

cancer, which maybe mediated by the promotion of blood vessel

growth. By contrast, it was reported that the downregulation of

miR-126 increased the activity of vascular endothelial growth

factor-A in lung and breast cancer (23–25).

miR-126 is regarded as a putative tumor suppressor due to its

potential role in anti-angiogenesis in cancer (26). Consequently, miR-126 may function

differently in stromal cells compared with tumor cells. The effect

and mechanism of miR-126 on angiogenesis in different cells or

tissue requires further research, to compare the effects of miR-126

in tumor cells with the functions of miR-126 in tumor vasculature

and the surrounding vessels of the tumor periphery.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by a grant from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

81200443).

References

|

1

|

Trounson A and McDonald C: Stem Cell

Therapies in Clinical Trials: Progress and Challenges. Cell Stem

Cell. 17:11–22. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yang Y, Chen XH, Li FG, Chen YX, Gu LQ,

Zhu JK and Li P: In vitro induction of human adipose-derived stem

cells into lymphatic endothelial-like cells. Cell Reprogram.

17:69–76. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hu F, Wang X, Liang G, Lv L, Zhu Y, Sun B

and Xiao Z: Effects of epidermal growth factor and basic fibroblast

growth factor on the proliferation and osteogenic and neural

differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells. Cell Reprogram.

15:224–232. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

De Ugarte DA, Morizono K, Elbarbary A,

Alfonso Z, Zuk PA, Zhu M, Dragoo JL, Ashjian P, Thomas B, Benhaim

P, et al: Comparison of multi-lineage cells from human adipose

tissue and bone marrow. Cells Tissues Organs. 174:101–109. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ikegame Y, Yamashita K, Hayashi S, Mizuno

H, Tawada M, You F, Yamada K, Tanaka Y, Egashira Y, Nakashima S, et

al: Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue and

bone marrow for ischemic stroke therapy. Cytotherapy. 13:675–685.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Locke M, Feisst V and Dunbar PR: Concise

review: Human adipose-derived stem cells: Separating promise from

clinical need. Stem Cells. 29:404–411. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Khan WS, Adesida AB, Tew SR, Longo UG and

Hardingham TE: Fat pad-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a

potential source for cell-based adipose tissue repair strategies.

Cell Prolif. 45:111–120. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fraser JK, Wulur I, Alfonso Z and Hedrick

MH: Fat tissue: An underappreciated source of stem cells for

biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 24:150–154. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Park IS, Rhie JW and Kim SH: A novel

three-dimensional adipose-derived stem cell cluster for vascular

regeneration in ischemic tissue. Cytotherapy. 16:508–522. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, Yu S, Yeh

RF, Wythe JD, Ivey KN, Bruneau BG, Stainier DY and Srivastava D:

miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev

Cell. 15:272–284. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X,

McAnally J, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R and Olson EN: The

endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity

and angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 15:261–271. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kuhnert F, Mancuso MR, Hampton J,

Stankunas K, Asano T, Chen CZ and Kuo CJ: Attribution of vascular

phenotypes of the murine Egfl7 locus to the microRNA miR-126.

Development. 135:3989–3993. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sasahira T, Kurihara M, Bhawal UK, Ueda N,

Shimomoto T, Yamamoto K, Kirita T and Kuniyasu H: Downregulation of

miR-126 induces angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis by activation of

VEGF-A in oral cancer. Br J Cancer. 107:700–706. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nowak WN, Florczyk U, Józkowicz A and

Dulak J: Role of microRNA in endothelial cells-regulation of

differentiation and angiogenesis. Postepy Biochem. 59:405–414.

2013.(In Polish). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yan T, Liu Y, Cui K, Hu B, Wang F and Zou

L: MicroRNA-126 regulates EPCs function: Implications for a role of

miR-126 in preeclampsia. J Cell Biochem. 114:2148–2159. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Meister J and Schmidt MH: miR-126 and

miR-126*: New players in cancer. ScientificWorldJournal.

10:2090–2100. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ikegame Y, Yamashita K, Hayashi S, Mizuno

H, Tawada M, You F, Yamada K, Tanaka Y, Egashira Y, Nakashima S, et

al: Comparison of mesenchymal stem cells from adiposetissue and

bonemarrow for ischemicstroke therapy. Cytotherapy. 13:675–685.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nakagami H, Maeda K, Morishita R, Iguchi

S, Nishikawa T, Takami Y, Kikuchi Y, Saito Y, Tamai K, Ogihara T

and Kaneda Y: Novel autologous cell therapy in ischemic limb

disease through growth factor secretion by cultured adipose

tissue-derived stromal cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

25:2542–2547. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Su SJ, Yeh YT, Su SH, Chang KL, Shyu HW,

Chen KM and Yeh H: Biochanin a promotes osteogenic but inhibits

adipogenic differentiation: Evidence with primary adipose-derived

stem cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013:8460392013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wu Z, Yin H, Liu T, Yan W, Li Z, Chen J,

Chen H, Wang T, Jiang Z, Zhou W and Xiao J: MiR-126-5p regulates

osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in giant cell tumor

through inhibition of MMP-13. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

443:944–949. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

El-Kenawi AE and El-Remessy AB:

Angiogenesis inhibitors in cancer therapy: Mechanistic perspective

on classification and treatment rationales. Br J Pharmacol.

170:712–729. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu B, Peng XC, Zheng XL, Wang J and Qin

YW: MiR-126 restoration down-regulate VEGF and inhibit the growth

of lung cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Lung Cancer.

66:169–175. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhu X, Li H, Long L, Hui L, Chen H, Wang

X, Shen H and Xu W: miR-126 enhances the sensitivity of non-small

cell lung cancer cells to anticancer agents by targeting vascular

endothelial growth factor A. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai).

44:519–526. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhu N, Zhang D, Xie H, Zhou Z, Chen H, Hu

T, Bai Y, Shen Y, Yuan W, Jing Q and Qin Y: Endothelial-specific

intron-derived miR-126 is down-regulated in human breast cancer and

targets both VEGFA and PIK3R2. Mol Cell Biochem. 351:157–164. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Feng R, Chen X, Yu Y, Su L, Yu B, Li J,

Cai Q, Yan M, Liu B and Zhu Z: miR-126 functions as a tumour

suppressor in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 298:50–63. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|