Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is a major threat to

human health, which increases the burden on the heart muscle

(1). It is estimated that >7

million succumbed to heart diseases in 2010 (2). Cardiac hypertrophy is a critical

phenotype that occurs in response to long-term cardiac overload

(3,4), which is frequently coupled with

inflammation, myocardial fibrosis and cell death. The

characteristics of cardiac hypertrophy consist of cell surface

enlargement, increased protein synthesis and alteration of

expression level of associated genes. Therefore, preventing and

reversing myocardial hypertrophy has become the main target of

cardiovascular disease treatment. Accordingly, it is essential to

develop drugs that can protect against myocardial injury.

Actinidia chinensis planch contains

polyphenolic acid. Its main active compound is Actinidia

chinensis planch polysaccharide (ACP) (5). ACP exhibits antibacterial, antiviral

and anti-tumor effects (6,7). However, little is known about the

effects of ACP on cardiomyocytes, and the underlying mechanisms

have not yet been fully elucidated and require further exploration.

In addition, investigating the potential molecular mechanisms will

provide important theoretical and practical significance for the

treatment of IHD. During the progression of IHD, a number of

cellular responses are involved, including gene transcription,

protein translation and cellular signal transduction (8,9). It

has been reported that apoptosis may be the cellular basis for the

pathological progression of cardiac hypertrophy, induced by

repeated ischemic events, to heart failure (4,10,11).

Currently, there are two main pathways associated with apoptosis,

the caspase-dependent and non-caspase-dependent pathways (12). The former includes the death

receptor-mediated extrinsic pathway and the intrinsic mitochondrial

pathway, which is associated with caspase-8 and caspase-9 (4,13).

Apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria associated 1 (AIF) is

associated with non-caspase-dependent pathways. It has been

demonstrated that caspase-3 serves a pivotal role in the majority

of apoptotic processes (14).

Furthermore, it is reported that the hypoxic conditions of

cardiomyocytes could induce cell apoptosis in vitro

(15,16), which mimic the process of ischemia

of myocardial cells in the body. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)

is a lipid kinase and the downstream target is serine/threonine

kinase protein kinase B (AKT), a conserved signal transduction

enzyme. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is critical to regulate

cellular activation, inflammatory responses and apoptosis (17). In addition, the extracellular

signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) signaling pathway serves a key

role in cell proliferation, survival, transformation and apoptosis

(18). It is well known that

ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT can be activated by phosphorylation. The

protective effects of the ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in

cardiomyocytes have been studied extensively (19–21).

In the present study, the protective effect and

mechanisms of ACP on the cardiomyocytes of rats was investigated.

The results of the present study indicated that ACP could protect

against apoptosis induced by hypoxia in cardiomyocytes treated with

Angiotensin II (Ang II). The potential mechanisms may be associated

with inhibiting the activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT. The results

of the present study provide important information for the

theoretical study and clinical treatment of the IHD.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

H9c2 cells were purchased from American Type Culture

Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Purified ACP was acquired from Xian

Tianrui Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Xi'an, China). Ang II used

in this study was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified

Eagle media (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham,

MA, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum

(Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), 100 U/ml penicillin

and 10 µg/ml streptomycin (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian,

China) in a humid atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at

37°C. Hypoxia treatment was used to mimic myocardial ischemia in

the body (22). At ~80%

confluence, H9c2 cells were cultured in serum-free medium overnight

at 37°C and five treatment groups were applied for the subsequent

experiments: i) Normal group, H9c2 cells were cultured with 0.1%

DMSO; ii) model group (MG), H9c2 cells were treated with 1 µM Ang

II for 48 h; iii) hypoxia treatment group (MGH), H9c2 cells were

treated 1 µM Ang II for 48 h, then the cells were incubated at 37°C

in a humidified atmosphere containing 95% N2 and 5%

CO2 for 8 h; iv) ACP pretreatment groups, Ang II-treated

(1 µM, 48 h) H9c2 cells were incubated in the medium containing ACP

at different doses (1.25 and 2.5 mg/ml) for 6 h prior to hypoxia

treatment for 8 h. For the specific activation of ERK1/2 and

PI3K/AKT, according to previous studies (23,24),

the cells were treated with recombinant human epidermal growth

factor (EGF; 100 ng/ml) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I;

100 ng/ml) for 12 h, respectively. Then the cells were subjected to

treatment with ACP and hypoxia.

Cell viability measurement

Cells in a 96-well plate at a density of

1×104 cells per well were serum starved overnight prior

to detection and then maintained as described above. Cell viability

was analyzed by Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech

Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured on a

spectrophotometric plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

Hercules, CA, USA). Each group was repeated in three different

wells.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP)

analysis

Cells in a 96-well plate at a density of

1×104 cell/well were treated as aforementioned. Under

normal conditions, the MMP is high and the JC-1 probe exhibits a

predominantly red fluorescence. The MMP is reduced in an apoptotic

or necrotic state and JC-1 dye fluoresces green. Cells were

incubated with the JC-1 (BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA)

working solution for 20 min at 37°C in the dark. The MMP was

detected using a flow cytometer and CellQuest software version 3.3

(BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) according to the

manufacturer's protocols.

Measurement of apoptosis

Following treatment as described above, H9c2 cells

(2×105/well) in a 6-well plate were stained by Annexin-V

and propidium iodide using the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)

Annexin-V apoptosis detection kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) as described previously (25). Then, flow cytometry was carried out

using a flow cytometer and CellQuest software version 3.3 (BD

Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Leucine incorporation assay

The protein synthesis rate was examined as

previously described (26).

According to the manufacturer's protocols, the incorporation of

3H-Leu [counts per minute CPM)] was measured by liquid

scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Bradford assay

H9c2 cells were treated as aforementioned. Bradford

reagent (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.,

Beijing, China) was added to each sample according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Then the samples were analyzed to

determine their absorbance at 595 nm. A standard curve of bovine

serum albumin (BSA; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used

as a control for all experiments. The protein content was detected

by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining assay

The cells in control, Ang II and ACP+Ang II groups

were prepared on slides for the subsequent experiments. The slides

were blocked by 5% BSA for 30 min at room temperature prior to the

cardiac troponin-T specific monoclonal antibody (cat. no. ab8259;

1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) being added at 4°C, overnight. Then

the slides were incubated with the anti-immunoglobulin G/FITC (cat.

no. ab150117; 1 µg/ml; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) secondary antibody at

room temperature for 1 h; nuclei were stained with DAPI for 15 min

at 37°C. The slides were mounted, a coverslip was added and then

the slides were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Then, 4 fields in each group were

randomly selected for analysis. The cell surface area was analyzed

by Image Pro-Plus software version 6.1 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.,

Rockville, MD, USA).

Total RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted with the TRIzol reagent,

according to the manufacturer's instructions (Life Technologies;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The RNA (2 µg) was reverse

transcribed using oligo (dT) primer (Takara Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.) and the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation,

Madison, WI, USA). The protocol was 65°C for 5 min; 25°C for 10

min; 42°C for 50 min; 70°C for 15 min; and holding at 4°C. The mRNA

expression was quantified using ABI 7500 Real-time PCR system

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and SYBR-Green

method (27,28) SYBR Premix Taq™ II kit (Takara Bio,

Inc., Otsu, Japan) was adopted for the amplification. Relative

expression levels were calculated using the 2−∆∆Cq

method, according to the previous description (29,30).

The amplification cycling conditions were as follows: 10 min at

95°C, then 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C and then a

final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR

were: AIF forward, 5′-CCGGGTAAATGCAGAGCTTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GCTCTGCATTTACCCGGAAG-3′; caspase-3 forward,

5′-AGAGCTGGACTGCGGTATTGAG-3′ and reverse,

5′-GAACCATGACCCGTCCCTTG-3′; caspase-8 forward,

5′-GAGGAAATGGTGAGGGAGCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCTCGAGTTGTCTTGCAGTT-3′;

caspase-9 forward, 5′-CATTGGTTCTGGCAGAGCTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TCAGGTCGTTCTTCACCTCC-3′; GAPDH forward,

5′-GGCACAGTCAAGGCTGAGAATG-3′ and reverse,

5′-ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGTA-3′.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted using the Total

protein extraction kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.). The concentration of proteins was determined by BCA

Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Equivalent amounts (15 µg) of protein

were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.).

For non-specific blocking, 5% non-fat milk was used. The blots were

then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The next

day, the blots were incubated with a horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1

h. Blots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence

Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). The antibodies used were anti-cleaved caspase-3 (cat. no.

9664; 1:1,000), anti-cleaved caspase-8 (cat. no. 9496; 1:1,000),

anti-cleaved caspase-9 (cat. no. 9505; 1:1,000), anti-AIF (cat. no.

5318; 1:1,000), anti-phosphorylated (p)-ERK1/2 (cat. no. 4370;

1:2,000), anti-p-AKT (cat. no. 4060; 1:2,000), anti-p-PIK3 (cat.

no. 4228; 1:1,000), anti-ERK1/2 (cat. no. 4695; 1:1,000), anti-AKT

(cat. no. 4685; 1:1,000), anti-PIK3 (cat. no. 3358; 1:1,000) and

anti-GAPDH (cat. no. 5174; 1:1,000), all of which were from Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (cat. no. sc-2004;

1:5,000) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., (Dallas, TX,

USA). Signals were visualized using BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The density of the

protein band was quantified with Quantity One Basic software

version 4.4.0 (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

All experiments in the present study were repeated

independently ≥3 times. All the data were analyzed using GraphPad

software version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA)

by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's multiple

comparison test. Data was expressed as the mean ± standard

deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Analysis of the cytotoxicity of ACP in

cardiomyocytes

To optimize the concentration used in the present

study, the cytotoxicity of ACP at different doses on cardiomyocytes

was examined, as described by a previous study (31). The CCK-8 assay revealed that cell

viability began to be inhibited at 5 mg/ml, although there was no

significant difference compared with the control group until 10

mg/ml. Thus, the viability of cardiomyocytes was suppressed by ACP

at 10 mg/ml (Fig. 1). Therefore,

the concentrations of 1.25 and 2.5 mg/ml were used for the

subsequent experiments.

ACP alleviates Ang II induced cardiac

hypertrophy

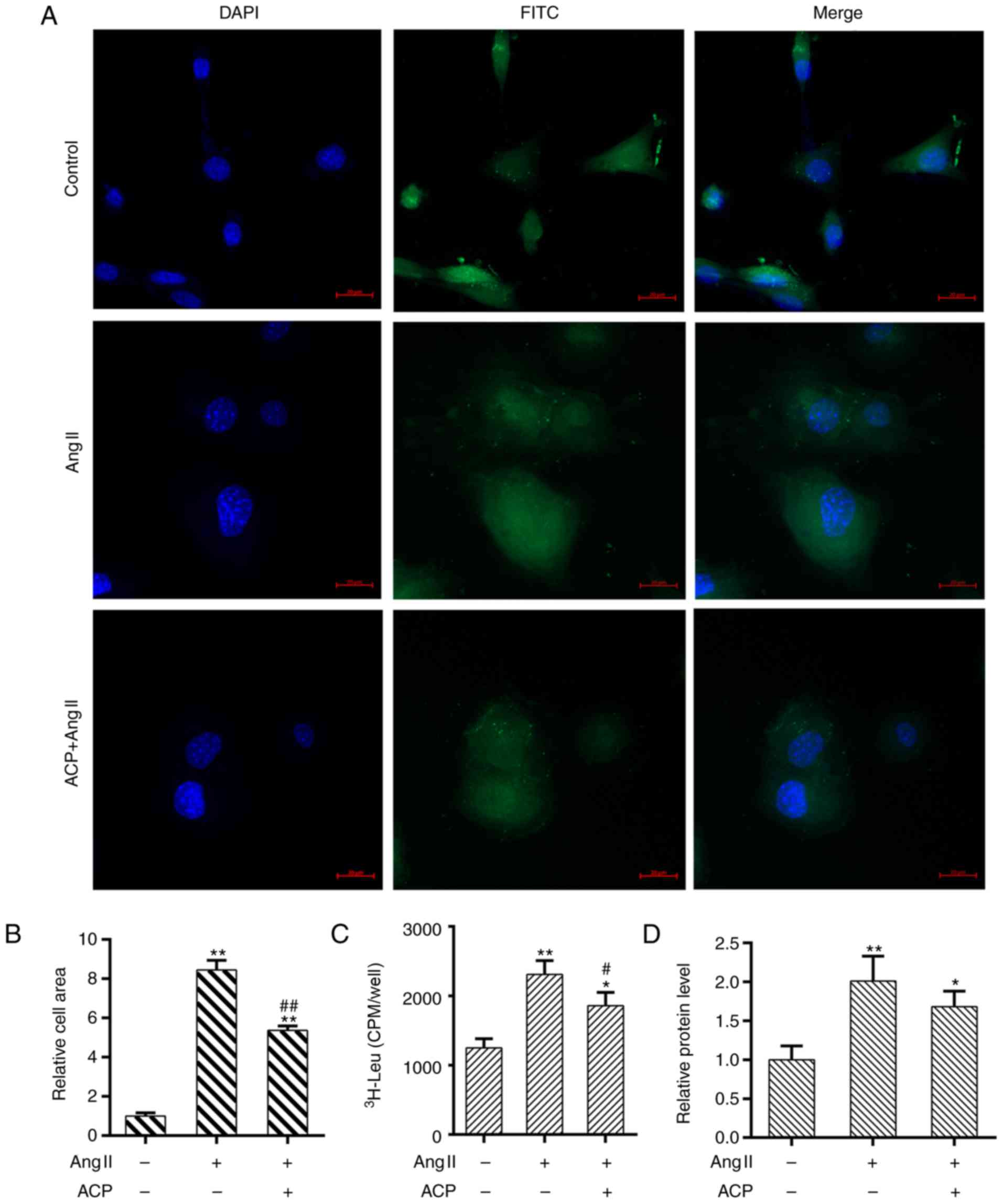

As shown in Fig.

2A, the cardiac phenotype of the obtained cells was identified.

The surface area of the cell was enlarged in cardiomyocytes

stimulated with Ang II, while ACP significantly reduced the cardiac

hypertrophy compared with the Ang II treated group (P<0.01;

Fig. 2A and B). Additionally, the

leucine incorporation assay demonstrated that ACP significantly

decreased the elevation in protein synthesis rate induced by

treatment with Ang II. (P<0.05; Fig. 2C). In addition, the Bradford assay

demonstrated that the protein content was significantly decreased

by ACP treatment compared with Ang II alone (P<0.05; Fig. 2D).

ACP improves the survival of

cardiomyocytes

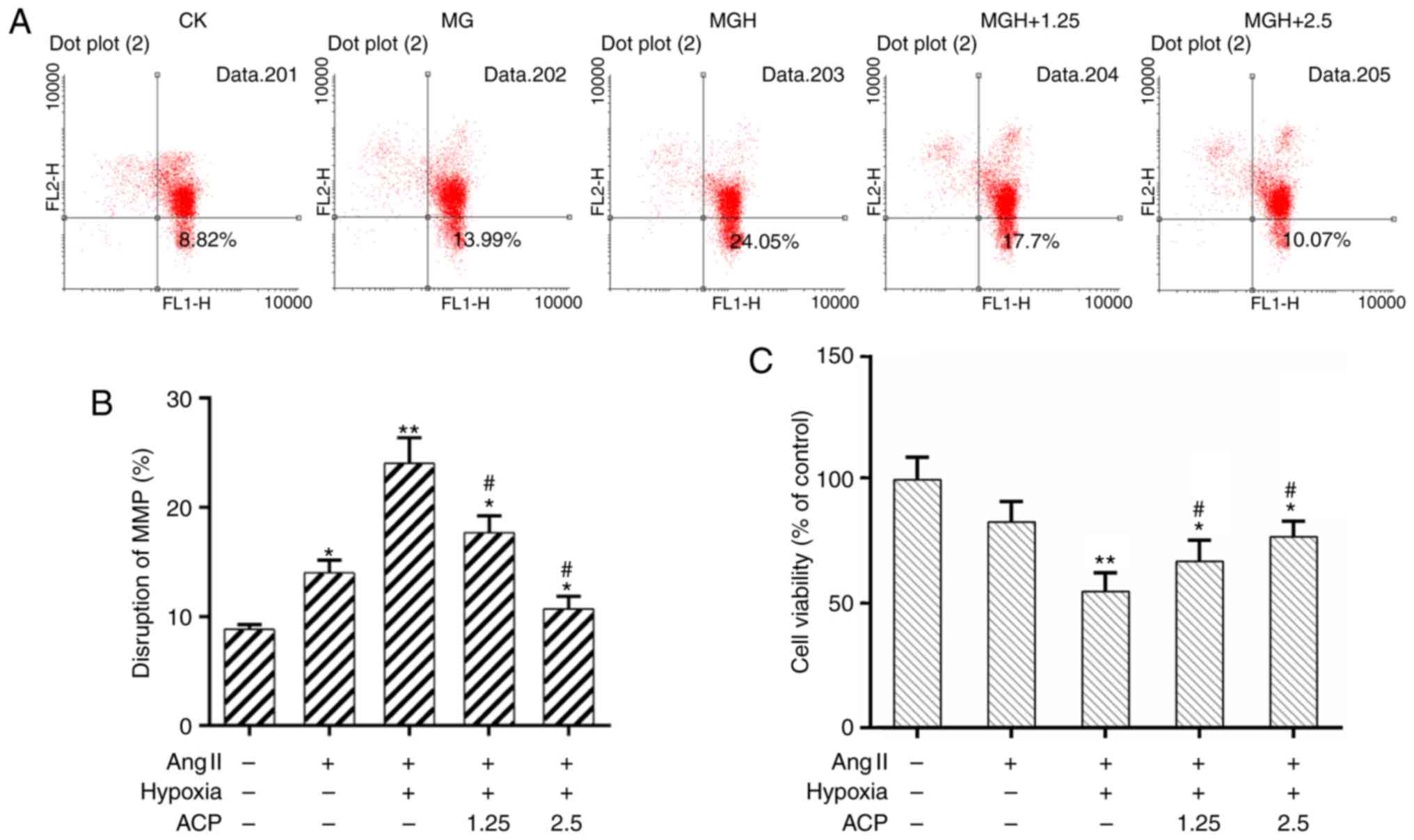

It is known that mitochondrial dysfunction will

trigger a cellular crisis (32,33).

It was demonstrated using flow cytometric analysis that the

disruption of the MMP was increased in the MGH group when compared

with the model group. The MMP was recovered effectively by

pretreatment with ACP (Fig. 3A and

B). In addition, the CCK-8 assay demonstrated that cell

viability was significantly improved in the ACP pretreatment groups

compared with the MGH group (P<0.05; Fig. 3C). These results suggested that ACP

could improve the survival of cardiomyocytes.

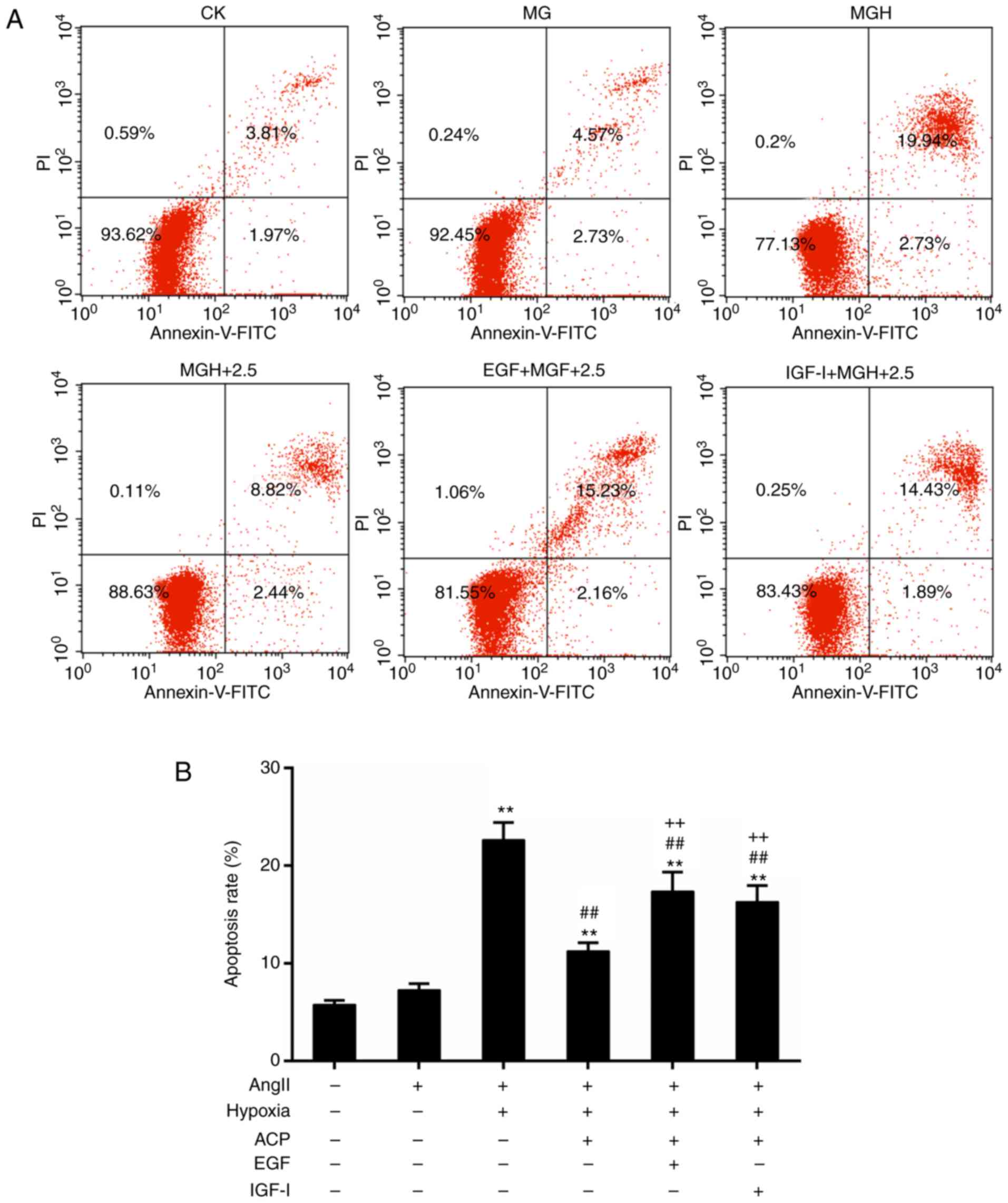

ACP mitigates apoptosis induced by

hypoxia in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes

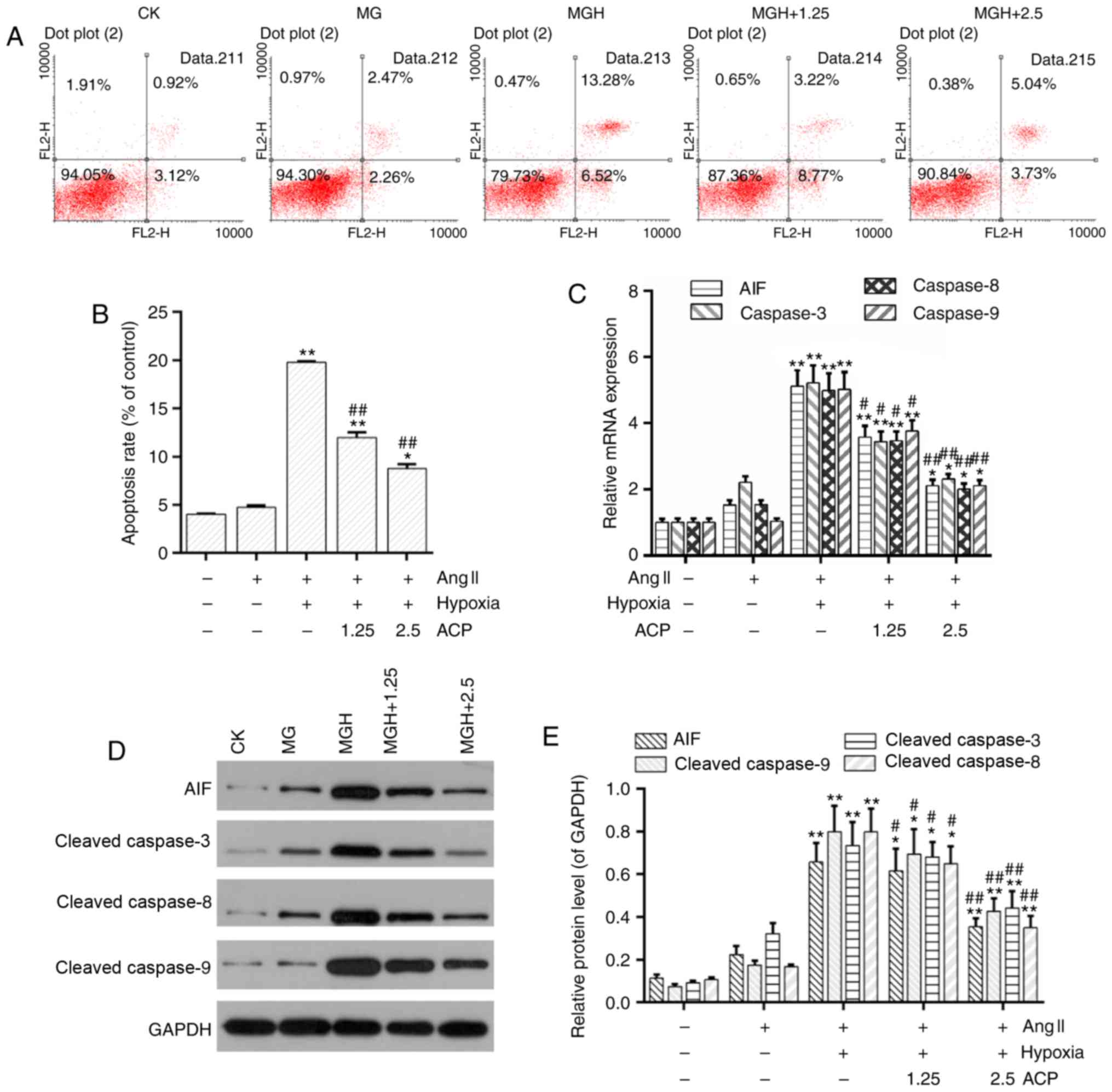

Disruption of the MMP is recognized as an important

event during the early stage of apoptosis (34,35).

The flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that cell apoptosis was

low in the model group whereas it was significantly increased in

the MGH group in comparison (P<0.01; Fig. 4A and B). However, cell apoptosis

was significantly decreased in the ACP pretreatment groups compared

with the MGH group (P<0.01; Fig. 4A

and B). Furthermore, the mRNA expression of

apoptosis-associated genes including AIF and caspase-3/8/9 were

downregulated in the ACP pretreatment groups compared with the MGH

group (Fig. 4C). Western blot

analysis demonstrated the protein levels of AIF and cleaved

caspase-3/8/9 were decreased in the ACP pretreatment groups

compared with the MGH group (Fig. 4D

and E).

ACP inhibits the phosphorylation of

ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT

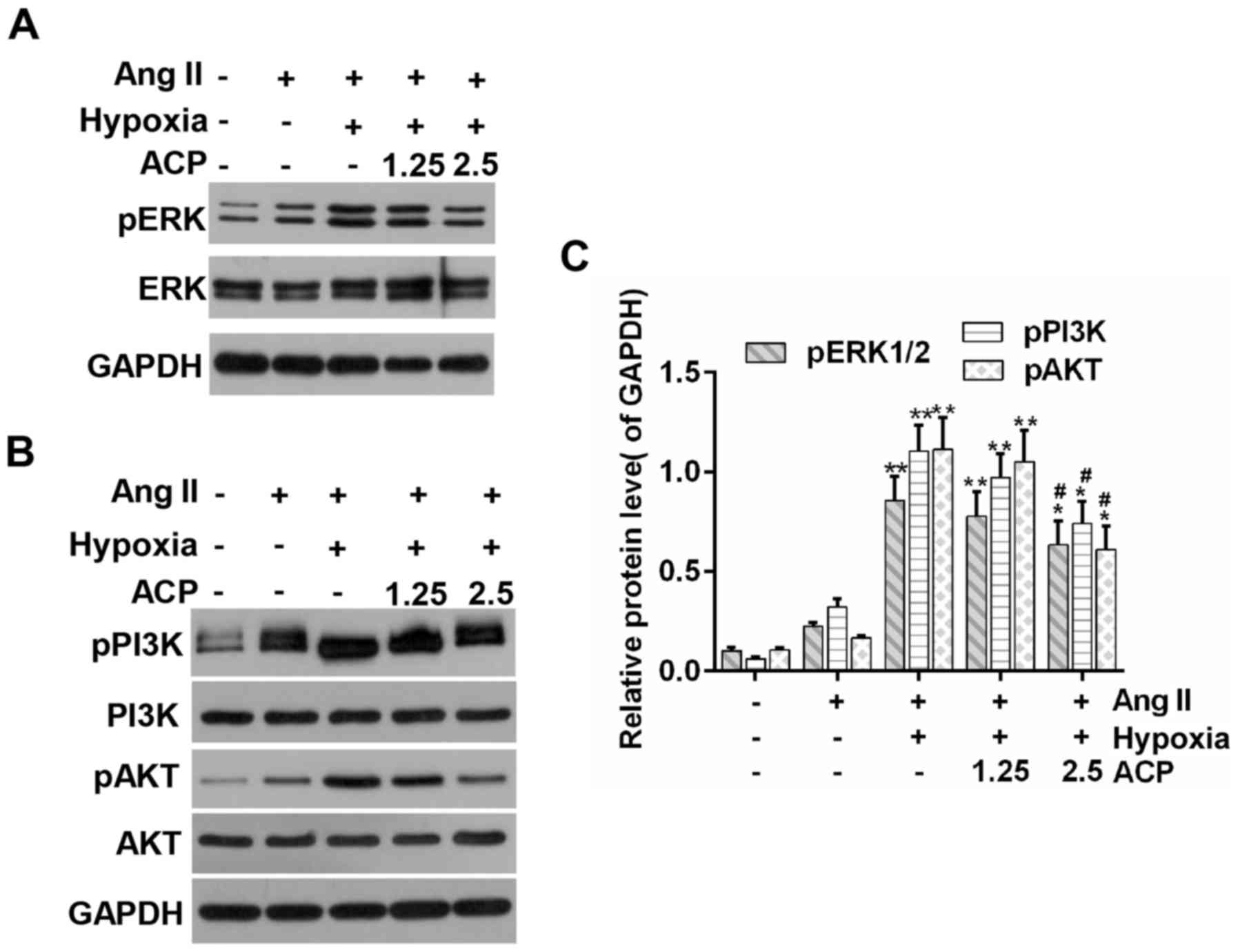

It has been reported that the ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT

signaling pathways contribute to the maintenance of myocardial

morphology and function (36).

Western blot analysis indicated that the phosphorylation levels of

ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT were increased in the model group compared to

control group; while it was further increased in the MGH groups.

The expression of p-ERK1/2, p-PI3K and p-AKT were depressed in the

ACP pretreatment groups when compared with the MGH group (Fig. 5).

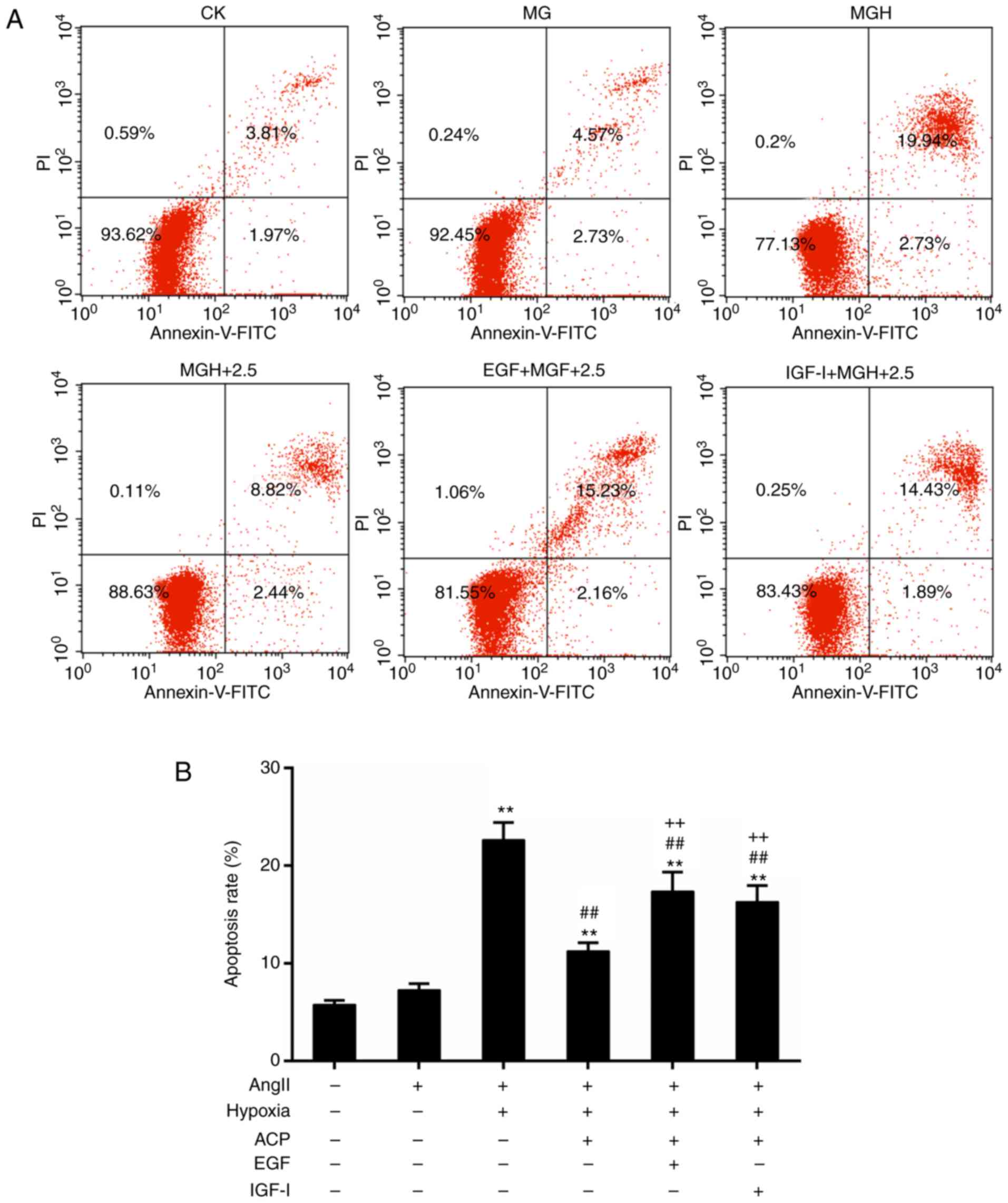

Specific activation of ERK1/2 and

PI3K/AKT reverses the inhibitory effect of ACP on apoptosis

Furthermore, specific activators were used to

determine the involvement of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT in the protective

role of ACP. Recombinant human EGF and IGF-I are activators for

ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT, respectively. Results from flow cytometry

analysis demonstrated that the activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT

did not inhibit hypoxia-induced apoptosis even in the presence of

ACP (Fig. 6). It was suggested

that the protective effects of are ACP likely dependent on

inhibiting the activation of the ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling

pathways.

| Figure 6.Activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT

reversed the apoptotic effect of ACP. (A) Flow cytometric analysis

for the detection of apoptosis. (B) Quantitative analysis of the

rate of apoptosis. The ACP (2.5 mg/ml) pretreatment groups included

the following: (MGH+2.5), EGF (100 ng/ml) and ACP (2.5 mg/ml)

treatment group (EGF+ MGH+2.5), and the IGF-I (100 ng/ml) and ACP

(2.5 mg/ml) treatment group (IGF-I + MGH+2.5). *P<0.05 and

**P<0.01 vs. CK; ##P<0.01 vs. MGH;

++P<0.01 vs. MGH+ACP. ACP, Actinidia chinensis

planch polysaccharide; CK, control mock; MG, model group; MGH,

hypoxia treatment group; EGF, epidermal growth factor; IGF-I,

insulin-like growth factor 1; Ang II, angiotensin II; PI, propidium

iodide; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. |

Discussion

IHD is a major threat to human health. Cardiac

hypertrophy is a common complication during the progression of IHD.

It is recognized that apoptosis serves an important role during the

progression from cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure (37,38).

It is hypothesized that cell apoptosis possesses a close connection

with the development of the heart diseases. As the center of

cellular energy and metabolism, the mitochondria serve a critical

role in the progression of cellular apoptosis (39). It has been reported that ACP

possesses multiple bioactivities (6,7). In

the present study, the potential effects of ACP on cardiomyocytes

of rats were investigated in vitro.

In the present study, Ang II was used to induce

cardiac hypertrophy. In addition, pretreatment with ACP reduced

cardiac hypertrophy. The collapse of the MMP leads to release of

pro-apoptotic molecules into the cytoplasm (40). Pretreatment with ACP rescued the

disruption of the MMP and improved the cell viability of

cardiomyocytes. It was indicated that the prevention of

mitochondrial dysfunction could protect against myocardial injury

(41). Furthermore, the rate of

apoptosis was decreased in the ACP pretreatment groups compared

with the MGH group. Several important molecules are involved in

apoptosis signals including AIF (42) and caspases-3/8/9 (43). The results of the present study

demonstrated that the expression of AIF and caspase-3/8/9 was

downregulated in the ACP pretreatment groups compared with those of

the MGH group at the transcriptional and translational levels.

These results suggested that ACP could protect against

cardiomyocyte apoptosis by regulating the apoptosis-associated

genes (AIF and caspase-3/8/9), which is in agreement with the

published anti-apoptotic effect of ACP in Neuro-2A cells (39). However, a previous study

demonstrated that ACP inhibited growth and induced apoptosis in

human gastric cancer cells (31).

These results may be attributed to several factors, including the

difference in the dosage of ACP, cell types and pathological

processes. A previous study demonstrated that the endoplasmic

reticulum stress-mediated pathway is involved in apoptosis

(44). However, the role of

endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis in the present study model

is not clear. Additionally, it is known that the ERK1/2 and

PI3K/AKT signaling pathways are involved in cardio-protection

(45,46). Notably, the results of the present

study demonstrated that pretreatment with ACP inhibited the

expression of p-ERK1/2 and p-PI3K/AKT. In addition, the activation

of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT reversed the inhibitory effect of ACP on

apoptosis. It is possible that ACP inhibited the phosphorylation of

ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT thereby decreasing myocardial apoptosis induced

by hypoxia. However, it was reported that ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT were

activated in multiple types of cancer, promoting cell survival and

inhibiting apoptosis (47–49). Nevertheless, previous studies have

demonstrated that instead of inhibiting cell death, the sustained

activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT rendered cells more sensitive to

metabolic stress (50–53). This implies dual roles for ERK1/2

and PI3K/AKT in tumor progression and the stress response (50). Currently, it has been reported that

several downstream targets were regulated by PI3K/AKT, including

Forkhead box protein O1, mammalian target of rapamycin and

endogenous nitric oxide synthase (54). However, the downstream targets of

ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT are not clear in the present study.

Furthermore, the mechanisms of cardiac protection involve a complex

signaling cascade, and how ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signals crosstalk

with other signaling pathways requires further investigation.

In conclusion, the present study identified that ACP

decreased mitochondrial dysfunction and improved cell viability of

cardiomyocytes treated with Ang II. In addition, ACP decreased

hypoxia-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes treated with Ang II.

Furthermore, ACP inhibited the activation of ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT

signaling pathways. It can be hypothesized that the protective

effects of ACP on hypoxia-induced apoptosis may depend on

inactivating the ERK1/2 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. The

results of the present study demonstrated the potential application

of ACP and provide important molecular evidence for the clinical

treatment of cardiac diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and/or analyzed during this study

are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

QiaW wrote the main manuscript. YX and YG performed

the experiments. QiaW and QW designed the study. YX performed data

analysis. QiaW and QW contributed to manuscript revisions and all

authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Morrone D, Marzilli M, Kolm P and

Weintraub WS: Do clinical trials in ischemic heart disease meet the

needs of those with ischemia? J Am Coll Cardiol. 65:1596–1598.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S,

Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et

al: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20

age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the global

burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 380:2095–2128. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Sag CM, Santos CX and Shah AM: Redox

regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 73:103–111.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fumarola C and Guidotti GG: Stress-induced

apoptosis: Toward a symmetry with receptor-mediated cell death.

Apoptosis. 9:77–82. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhou XF, Zhang P, Pi HF, Zhang YH, Ruan

HL, Wang H and Wu JZ: Triterpenoids from the roots of actinidia

chinensis. Chem Biodivers. 6:1202–1207. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lim S, Han SH, Kim J, Lee HJ, Lee JG and

Lee EJ: Inhibition of hardy kiwifruit (Actinidia aruguta) ripening

by 1-methylcyclopropene during cold storage and anticancer

properties of the fruit extract. Food Chem. 190:150–157. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Concha-Meyer AA, D'Ignoti V, Saez B, Diaz

RI and Torres CA: Effect of storage on the physico-chemical and

antioxidant properties of strawberry and kiwi leathers. J Food Sci.

81:C569–C577. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lyon RC, Zanella F, Omens JH and Sheikh F:

Mechanotransduction in cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Circ Res.

116:1462–1476. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Maillet M, van Berlo JH and Molkentin JD:

Molecular basis of physiological heart growth: Fundamental concepts

and new players. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14:38–48. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Li Q, Wang F, Zhang YM, Zhou JJ and Zhang

Y: Activation of cannabinoid type 2 receptor by JWH133 protects

heart against ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 31:693–702. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mitrega KA, Nozynski J, Porc M, Spalek AM

and Krzeminski TF: Dihydropyridines' metabolites-induced early

apoptosis after myocardial infarction in rats; new outlook on

preclinical study with M-2 and M-3. Apoptosis. 21:195–208. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Qiu Q, Yang C, Xiong W, Tahiri H, Payeur

M, Superstein R, Carret AS, Hamel P, Ellezam B, Martin B, et al:

SYK is a target of lymphocyte-derived microparticles in the

induction of apoptosis of human retinoblastoma cells. Apoptosis.

20:1613–1622. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Thornberry NA and Lazebnik Y: Caspases:

Enemies within. Science. 281:1312–1316. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Santos N, Silva RF, Pinto M, Silva EBD,

Tasat DR and Amaral A: Active caspase-3 expression levels as

bioindicator of individual radiosensitivity. An Acad Bras Cienc. 89

1 Suppl 0:S649–S659. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

McDougal AD and Dewey CF Jr: Modeling

oxygen requirements in ischemic cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem.

292:11760–11776. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yang Y, Ding S, Xu G, Chen F and Ding F:

MicroRNA-15a inhibition protects against

hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes by

targeting mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7. Mol Med Rep.

15:3699–3705. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dorn GW II and Force T: Protein kinase

cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest.

115:527–537. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sun J, Sun G, Meng X, Wang H, Luo Y, Qin

M, Ma B, Wang M, Cai D, Guo P, et al: Isorhamnetin protects against

doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in vivo and in vitro. PLoS One.

8:e645262013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chanda D, Luiken JJ and Glatz JF:

Signaling pathways involved in cardiac energy metabolism. FEBS

Lett. 590:2364–2374. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Daskalopoulos EP, Dufeys C, Bertrand L,

Beauloye C and Horman S: AMPK in cardiac fibrosis and repair:

Actions beyond metabolic regulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

91:188–200. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Saxena A, Shinde AV, Haque Z, Wu YJ, Chen

W, Su Y and Frangogiannis NG: The role of Interleukin Receptor

Associated Kinase (IRAK)-M in regulation of myofibroblast phenotype

in vitro and in an experimental model of non-reperfused myocardial

infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 89:223–231. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sepuri NBV, Angireddy R, Srinivasan S,

Guha M, Spear J, Lu B, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Suzuki CK and

Avadhani NG: Mitochondrial LON protease-dependent degradation of

cytochrome c oxidase subunits under hypoxia and myocardial

ischemia. Biochimica Biophys Acta. 1858:519–528. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Huang P, Xu X, Wang L, Zhu B, Wang X and

Xia J: The role of EGF-EGFR signalling pathway in hepatocellular

carcinoma inflammatory microenvironment. J Cell Mol Med.

18:218–230. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang M, Zhou Q, Liang QQ, Li CG, Holz JD,

Tang D, Sheu TJ, Li TF, Shi Q and Wang YJ: IGF-1 regulation of type

II collagen and MMP-13 expression in rat endplate chondrocytes via

distinct signaling pathways. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 17:100–106.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Cai XY, Xia Y, Yang SH, Liu XZ, Shao ZW,

Liu YL, Yang W and Xiong LM: Ropivacaine- and bupivacaine-induced

death of rabbit annulus fibrosus cells in vitro: Involvement of the

mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

23:1763–1775. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kirchman D, K'Nees E and Hodson R: Leucine

incorporation and its potential as a measure of protein synthesis

by bacteria in natural aquatic systems. Appl Environ Microbiol.

49:599–607. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Richards GP, Watson MA and Kingsley DH: A

SYBR green, real-time RT-PCR method to detect and quantitate

Norwalk virus in stools. J Virol Methods. 116:63–70. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Du Z, Li S, Liu L, Yang Q, Zhang H and Gao

C: NADPH oxidase 3associated oxidative stress and caspase

3-dependent apoptosis in the cochleae of D-galactose induced aged

rats. Mol Med Rep. 12:7883–7890. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Arocho A, Chen B, Ladanyi M and Pan Q:

Validation of the 2-DeltaDeltaCt calculation as an alternate method

of data analysis for quantitative PCR of BCR-ABL P210 transcripts.

Diagn Mol Pathol. 15:56–61. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Song WY, Xu GH and Zhang GJ: Effect of

Actinidia chinensis planch polysaccharide on the growth and

apoptosis and p-p38 expression in human gastric cancer SGC-7901

cells. Zhongguo Zhong xi yi jie he za zhi. 34:329–333. 2014.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Verma P, Singh A, Nthenge-Ngumbau DN,

Rajamma U, Sinha S, Mukhopadhyay K and Mohanakumar KP: Attention

deficit-hyperactivity disorder suffers from mitochondrial

dysfunction. BBA Clin. 6:153–158. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Jamshidzadeh A, Heidari R, Abasvali M,

Zarei M, Ommati MM, Abdoli N, Khodaei F, Yeganeh Y, Jafari F, Zarei

A, et al: Taurine treatment preserves brain and liver mitochondrial

function in a rat model of fulminant hepatic failure and

hyperammonemia. Biomedicine Pharmacother. 86:514–520. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Yan X, Wang L, Yang X, Qiu Y, Tian X, Lv

Y, Tian F, Song G and Wang T: Fluoride induces apoptosis in H9c2

cardiomyocytes via the mitochondrial pathway. Chemosphere.

182:159–165. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liang W, Liao Y, Zhang J, Huang Q, Luo W,

Yu J, Gong J, Zhou Y, Li X, Tang B, et al: Heat shock factor 1

inhibits the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway by regulating second

mitochondria-derived activator of caspase to promote pancreatic

tumorigenesis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 36:642017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jeong JJ, Ha YM, Jin YC, Lee EJ, Kim JS,

Kim HJ, Seo HG, Lee JH, Kang SS, Kim YS and Chang KC: Rutin from

Lonicera japonica inhibits myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion-induced apoptosis in vivo and protects H9c2

cells against hydrogen peroxide-mediated injury via ERK1/2 and

PI3K/Akt signals in vitro. Food Chem Toxicol. 47:1569–1576. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Fazal L, Laudette M, Paula-Gomes S, Pons

S, Conte C, Tortosa F, Sicard P, Sainte-Marie Y, Bisserier M,

Lairez O, et al: Multifunctional mitochondrial epac1 controls

myocardial cell death. Circ Res. 120:645–657. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Krech J, Tong G, Wowro S, Walker C,

Rosenthal LM, Berger F and Schmitt KRL: Moderate therapeutic

hypothermia induces multimodal protective effects in oxygen-glucose

deprivation/reperfusion injured cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrion.

35:1–10. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Roberts ER and Thomas KJ: The role of

mitochondria in the development and progression of lung cancer.

Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 6:e2013030192013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Gharanei M, Hussain A, Janneh O and

Maddock HL: Doxorubicin induced myocardial injury is exacerbated

following ischaemic stress via opening of the mitochondrial

permeability transition pore. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 268:149–156.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ahmed LA and El-Maraghy SA: Nicorandil

ameliorates mitochondrial dysfunction in doxorubicin-induced heart

failure in rats: Possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Biochem

Pharmacol. 86:1301–1310. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I,

Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler

M, et al: Molecular characterization of mitochondrial

apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 397:441–446. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Grutter MG: Caspases: Key players in

programmed cell death. Curr Opi Struct Biol. 10:649–655. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Nasu K, Nishida M, Kawano Y, Tsuno A, Abe

W, Yuge A, Takai N and Narahara H: Aberrant expression of

apoptosis-related molecules in endometriosis: A possible mechanism

underlying the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Reprod Sci.

18:206–218. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hu Y, Li L, Yin W, Shen L, You B and Gao

H: Protective effect of proanthocyanidins on anoxia-reoxygenation

injury of myocardial cells mediated by the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3beta

pathway and mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel. Mol Med

Rep. 10:2051–2058. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang Z, Zhang H, Xu X, Shi H, Yu X, Wang

X, Yan Y, Fu X, Hu H, Li X and Xiao J: bFGF inhibits ER stress

induced by ischemic oxidative injury via activation of the PI3K/Akt

and ERK1/2 pathways. Toxicol Lett. 212:137–146. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Manning BD and Cantley LC: AKT/PKB

signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 129:1261–1274. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ramalingam M, Kwon YD and Kim SJ: Insulin

as a potent stimulator of Akt, ERK and inhibin-βE signaling in

osteoblast-like UMR-106 cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 24:589–594.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Pillai VB, Kanwal A, Fang YH, Sharp WW,

Samant S, Arbiser J and Gupta MP: Honokiol, an activator of

Sirtuin-3 (SIRT3) preserves mitochondria and protects the heart

from doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in mice. Oncotarget.

8:34082–34098. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Los M, Maddika S, Erb B and

Schulze-Osthoff K: Switching Akt: From survival signaling to deadly

response. Bioessays. 31:492–495. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Coloff JL, Mason EF, Altman BJ, Gerriets

VA, Liu T, Nichols AN, Zhao Y, Wofford JA, Jacobs SR, Ilkayeva O,

et al: Akt requires glucose metabolism to suppress puma expression

and prevent apoptosis of leukemic T cells. J Biol Chem.

286:5921–5933. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Elstrom RL, Bauer DE, Buzzai M, Karnauskas

R, Harris MH, Plas DR, Zhuang H, Cinalli RM, Alavi A, Rudin CM and

Thompson CB: Akt stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells.

Cancer Res. 64:3892–3899. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Nogueira V, Park Y, Chen CC, Xu PZ, Chen

ML, Tonic I, Unterman T and Hay N: Akt determines replicative

senescence and oxidative or oncogenic premature senescence and

sensitizes cells to oxidative apoptosis. Cancer cell. 14:458–470.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Matsui T and Rosenzweig A: Convergent

signal transduction pathways controlling cardiomyocyte survival and

function: The role of PI 3-kinase and Akt. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

38:63–71. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|