Introduction

Liver fibrosis may be caused by acute or chronic

liver injury and has been associated with severe morbidity and

mortality (1). The progression

from hepatitis to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and even hepatic

carcinoma has been reported to be accelerated by the occurrence of

metabolic liver disease, alcoholism and viral hepatitis (2,3).

The development of liver fibrosis is a result of the interaction

among various types of resident hepatocytes, inflammatory cells,

mediators and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, which are

usually characterized by increased matrix protein production and

decreased matrix remodeling (4,5).

Liver fibrosis accelerates the progression of acute liver disease

to its chronic form by disrupting the normal liver parenchyma

(6). Furthermore, animal models

that simulate liver fibrosis have improved our understanding of

liver injury, and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced

liver fibrosis is widely used in mouse models to study hepatotoxic

mechanisms (3,7). CCl4-induced acute liver

injury leads to the complex regulation of cellular responses. It

has previously been established that continuous exposure of mice to

a low dose of CCl4 (0.2 ml/kg), beginning at 8 weeks of

age and lasting up to 6 weeks, leads to the development of liver

fibrosis and compensatory cell proliferation (8). A CCl4-induced liver

fibrosis mouse model has been demonstrated to be able to

effectively simulate the formation of liver injury in vivo,

which has been widely used in the study of the mechanism of

hepatotoxicity (3,8–11).

Currently, treatments for liver fibrosis mainly

include eliminating the primary causes and suppressing

inflammation. However, there is still a lack of effective

preventative methods or therapeutic drugs for liver fibrosis

(12,13). The drug discovery process has paid

great attention to the investigation of the efficacy drugs used in

traditional medicine, as they are cheaper and have fewer side

effects. Pien Tze Huang (PZH), a complex combination of Panax

notoginseng (85%); Calculus bovis (5%); snake

gallbladder (7%), obtained from the dry gall bladder of snake; and

musk (3%), obtained from the preputial gland located in the abdomen

of male musk deer, has been used as a traditional medicine with

anti-inflammatory and soothing effects on skin boils and abscesses

(14). A previous study has

demonstrated that PZH exerts an important protective effect on

CCl4-induced liver injury in mice (15). Additional studies have also

suggested that PZH is effective in inhibiting liver damage caused

by excessive drinking (16),

improving histopathological damage in the liver and positively

affecting physiological and biochemical indexes, such as serum

alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, to a

certain extent (15,17). Cell necrosis and swelling,

microvesicular steatosis and lymphocyte infiltration in the injured

liver have been reported to be significantly reduced following PZH

treatment for liver disease (18).

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a recently discovered

type of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). Most circRNAs are endogenous

ncRNAs, and their formation does not have a covalent ring structure

at the 3′ and 5′ end (19). Owing

to their special structure, circRNAs cannot be easily degraded by

nucleic acid exoenzyme ribonuclease R (RNase R) and are more stable

than linear RNA (20).

Furthermore, circRNAs regulate alternative splicing and

transcription in a variety of diseases by acting as efficient

microRNA (miRNA/miR) sponges, which can efficiently prevent the

suppression of their mRNA targets (21,22). A previous study confirmed the

regulatory role of circRNAs in circRNA/miRNA-gene regulatory

networks by building a database of circRNAs derived from

transcriptome sequencing data (23). Therefore, the interactions among

circRNA, miRNA and mRNA have been considered important in

transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation.

An increasing number of studies have demonstrated

that circRNAs can act as promising and technically suitable

biomarkers for the occurrence and development of various diseases

(24–28). Recently, Xu et al (29) analyzed the regulatory role of the

circRNA/miRNA/mRNA network and revealed that circRNA_0001178 and

circRNA_0000826 may be potential diagnostic markers for colorectal

cancer metastasis. Furthermore, a recent study revealed that Mus

musculus (mmu)_circRNA_002381 may influence the regulatory

process of the transcription of certain genes affected by

cocaine-induced neuroplasticity via the circRNA/miRNA interaction

network (30). However, it

remains unclear as to how the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA network modulates

improvements in the fibrotic liver tissue of PZH-treated

subjects.

The present study investigated the hepatoprotective

activity of PZH against CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, and

aimed to determine the circRNA-based molecular mechanisms by which

it may confer its protection on the mice liver against

CCl4-induced liver damage. Differentially expressed

circRNAs were successfully identified using high-throughput

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) in liver tissues from

CCl4-induced and PZH-treated mice. The sponging action

of differentially expressed circRNAs and related miRNA targets was

further examined using multiple bioinformatics tools. Moreover,

functional circRNA/miRNA/mRNA networks were established to provide

novel insights into the treatment of liver fibrosis with PZH. The

functional characteristics of the representative circRNA candidates

were further analyzed by performing reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) on the mRNAs associated

with the differentially expressed circRNAs in hepatic stellate

cells (HSCs).

Materials and methods

Animal experiment

A total of 45 C57BL/6 mice of each group (age, 6

weeks; weight, 20–30 g) were purchased from Shanghai Model

Organisms Center, Inc. The mice were housed at 24±2°C, relative

humidity of 55±15%, kept in clean cages under a 14/10 h light-dark

cycle and fed with standard rodent diet throughout the entire

experimental period. Mice were randomly divided into two groups

named the ‘PZH-treated’ and ‘CCl4-induced’ (PZH-treated,

hepatic fibrosis model using PZH plus CCl4;

CCl4-induced, hepatic fibrosis model using

CCl4 only; n=15 mice/group). Meanwhile, a no-induction

group (n=15 mice/group) was added to confirm the success of the

liver fibrosis model. Mice in the CCl4-induced liver

fibrosis model group were intraperitoneally injected with a solvent

mixture of 10 µl/g body weight CCl4 (Wuhan Yafa

Biological Technology Co., Ltd.) and 10% corn oil twice a week and

intragastrically administered with double-distilled

(dd)H2O once a day. Mice in the PZH-treatment group were

intraperitoneally injected with a solvent mixture of 10 µl/g body

weight CCl4 and 10% corn oil twice a week (31) and intragastrically administered

with 0.25 mg/g PZH-sonicated reagent (Zhangzhou Pientzehuang

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Chinese Food and Drug Administration

approval no. Z35020242; the PZH drug powder was dissolved in double

distilled water, and its concentration was diluted to 25 mg/ml)

once a day. During the 8-week experimental period, three mice in

each group were anesthetized intraperitoneally with 40 mg/kg

pentobarbital (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) and sacrificed by

cervical dislocation every 2 weeks in the first 6 weeks, and their

liver tissue and blood were harvested for detecting the hepatic

fibrosis level and hepatic biochemical index. The remaining 12 mice

were also anesthetized and sacrificed by cervical dislocation in

the 8th week. Mice were subsequently subjected to a laparotomy and

liver tissue was harvested for the following experiments.

Throughout the animal experiment mental state, hair and the body

weight of the mice were closely monitored for toxic effects caused

by CCl4. No significant differences were observed in the

body weight of the mice between CCl4-induced and

PZH-treated groups (P=0.7772; Fig.

S1). The experimental procedures in the present study were

approved by The Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Jiao Tong

University (Shanghai, China; approval no. IACUC.NO:2017-0033).

RNA isolation for high-throughput

sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from mouse liver tissue

samples using TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were then

processed with RNase-free DNase to remove traces of genomic DNA.

The RNA concentration and quality were determined using a

NanoDrop® ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and the Bioanalyzer 2100 System (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). The A260/A280 ratio and RNA integrity number

(RIN; Agilent Technologies Deutschland GmbH) were used to assess

RNA purity and integrity, respectively (32). All samples met the following

criteria: A260/A280 ratio >1.8 and RIN >8, which means that

the RNA integrity was high quality for sequencing.

Transcriptome data analysis

RNA libraries were constructed using ribosomal

RNA-depleted RNAs with TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Kit

(cat. no. RS-122-2201; Illumina, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 5 µg RNA was treated using the

Ribo-Zero™ kit (cat. no. MRZH11124; Illumina, Inc.) to remove all

ribosomal RNAs and linear RNAs were digested using RNase R (cat.

no. RNR07250; Lucigen Corporation). Subsequently, the enriched

circRNAs were fragmented and a double-stranded cDNA library was

synthesized using random primers and adapters. Finally, the cDNAs

were purified and amplified with a thermocycler. All samples were

mixed and underwent bridge amplification to generate clusters using

HiSeq 4000 Paired-End Cluster Kit (cat. no. PE-410-1001-1;

Illumina, Inc.). Quality control was performed using Q30. The

library was subjected to 150-bp paired-end sequencing using HiSeq

4000 SBS Kit (cat. no. FC-410-1001-1; Illumina, Inc.). FastQC

(version v0.11.5; http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc)

(33) was used to evaluate the

quality of the sequencing data. Trim-galore (version 0.6.0)

(34) with default parameters was

used to remove double-ended adapters and perform quality control on

raw sequencing data.

Identification of differentially

expressed circRNAs between the two groups

The filtered data were first mapped to the reference

genome/transcriptome (version mm10, downloaded from UCSC,

http://genome.ucsc.edu/) using STAR software

version 2.5.3 (35). Only the

common circRNAs predicted by CIRI (version 2.0.6) (36) and CIRCexplorer (37) software were termed ‘identified

circRNAs’ in the subsequent analysis. CircBase (http://www.circbase.org/) (38) and Circ2Traits (39) (http://gyanxet-beta.com/circdb) databases were used to

annotate the identified circRNAs. circRNAs were normalized to the

number of back-splice junctions spanning spliced reads per billion

mapping (SRPBM). The differentially expressed circRNAs were

screened according to a log2(FC)>1 and P<0.05.

RNA-seq data were deposited in National Center for Biotechnology

Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; accession no.

GSE150883).

Target prediction and bioinformatics

analysis

For the specific competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA)

network of significantly dysregulated circRNAs and mRNAs, the

miRNA/mRNA and miRNA/circRNA interactions were predicted using the

RegRNA 2.0 (40) (http://regrna2.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/), miRWalk 2.0

(41) (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de) and TargetScan

7.2 (42) (http://www.targetscan.org) databases. miRNA-binding

sites on circRNAs were determined using RegRNA 2.0 with a cutoff

score of ≥170 and free energy of ≤-25. The putative target genes of

these miRNAs were identified using the miRWalk algorithm with a

binding energy of ≤-30 (43). The

intersection of predicted target genes identified by both of these

algorithms was selected as the differentially expressed

circRNA-related predicted target genes in the present study for

further analysis. The shared mRNAs between the differentially

expressed circRNA-related predicted target genes in the present

study and the differentially expressed mRNAs from mRNA-seq data

(GEO accession no. GSE133481) were extracted. The overlapping

mRNA-related miRNAs and miRNA binding sites on these circRNAs were

selected to construct the ceRNA regulatory network. Cytoscape

(version 3.6.1) was used to visualize the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA

network interactions (44). The R

package Cluster Profiler (45)

was used for Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (http://geneontology.org/) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (https://www.kegg.jp/) was used for pathway analysis of

the differentially expressed circRNA-related target genes based on

the adjusted P<0.05.

Validation of differentially expressed

circRNA-related target gene candidates by RT-qPCR in LX-2

cells

The expression levels of candidate differentially

expressed circRNA-related target genes in the ceRNA network were

further validated by RT-qPCR in the human hepatic stellate LX-2

cell line (American Type Culture Collection). LX-2 cells were grown

in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C in DMEM (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS

(MilliporeSigma), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

µg/ml streptomycin (complete medium; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Cells were seeded into 6-well plates

(1×106/well) and divided into the PZH-induced (0.75

mg/ml) and the untreated control groups. The expression levels of

differentially expressed circRNA-related target gene candidates

were determined at 24, 48 and 72 h. Total RNA was extracted from

LX-2 cells using TRIzol reagent, aforementioned. Total RNA was

reversed transcribed into cDNA using 1 µg isolated RNA with the

PrimeScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara Bio, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. qPCR was subsequently

performed using an ABI7500 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master

(Roche Diagnostics). Each qPCR reaction contained 25 µl FastStart

Universal SYBR Green Master, 0.3 µM forward primer, 0.3 µM reverse

primer, 50 ng cDNA template and ddH2O to a final volume

of 50 µl. The qPCR conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation

at 95°C for 10 min; followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 and 60 sec

at 60°C. All primers are shown in Table SI. Relative mRNA expression

levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method and

normalized to the internal reference gene GAPDH (46). At 2−ΔΔCq >1, the

mRNA expression levels were considered to be upregulated and at

2−ΔΔCq <1 downregulated.

Statistical analysis

Data from three independent experiments were used

for analysis. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism

8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used for all statistical

analyses. Unpaired Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA with Duncan's

post hoc test were used to determine the statistical differences

between the control and PZH-treated groups. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis was performed using the survival

package in R (version 3.6.3) (47) to explore the relationship between

the differentially expressed circRNA-related targets and the status

data of 269 clinical patients with liver hepatocellular carcinoma

from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (48). Patients with expression levels

higher than the median values were assigned to the high-expression

group, and patients with expression levels lower than the median

values were assigned to the low-expression group. Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis was performed to plot survival curves and the

log-rank test was used to assess the statistical difference in

survival rates between the high- and low-expression groups.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Prediction and expression analysis of

circRNAs

To identify differentially expressed circRNAs in

PZH-treated mice exhibiting liver damage improvement compared with

the CCL4-induced group, RNA-seq was used to profile

circRNA expression levels in the tissue samples from six

PZH-treated mice and six CCL4-induced mice with liver

fibrosis. The quality control results from the sequencing data

demonstrated that the Q30 of all samples reached 95% (Table I). The filtered data was

subsequently mapped to the reference genome/transcriptome

(GRCm38/mm10; Table II). CIRI

and CIRCexplorer software were used to identify the circRNAs in all

samples. Detailed information regarding the circRNAs identified is

displayed in Table SII. A total

of 59,476 intersection circRNAs were detected by circRNA-seq. Among

all the types of circRNA, the proportion of exon circRNA was as

high as 98.35% (Table SII).

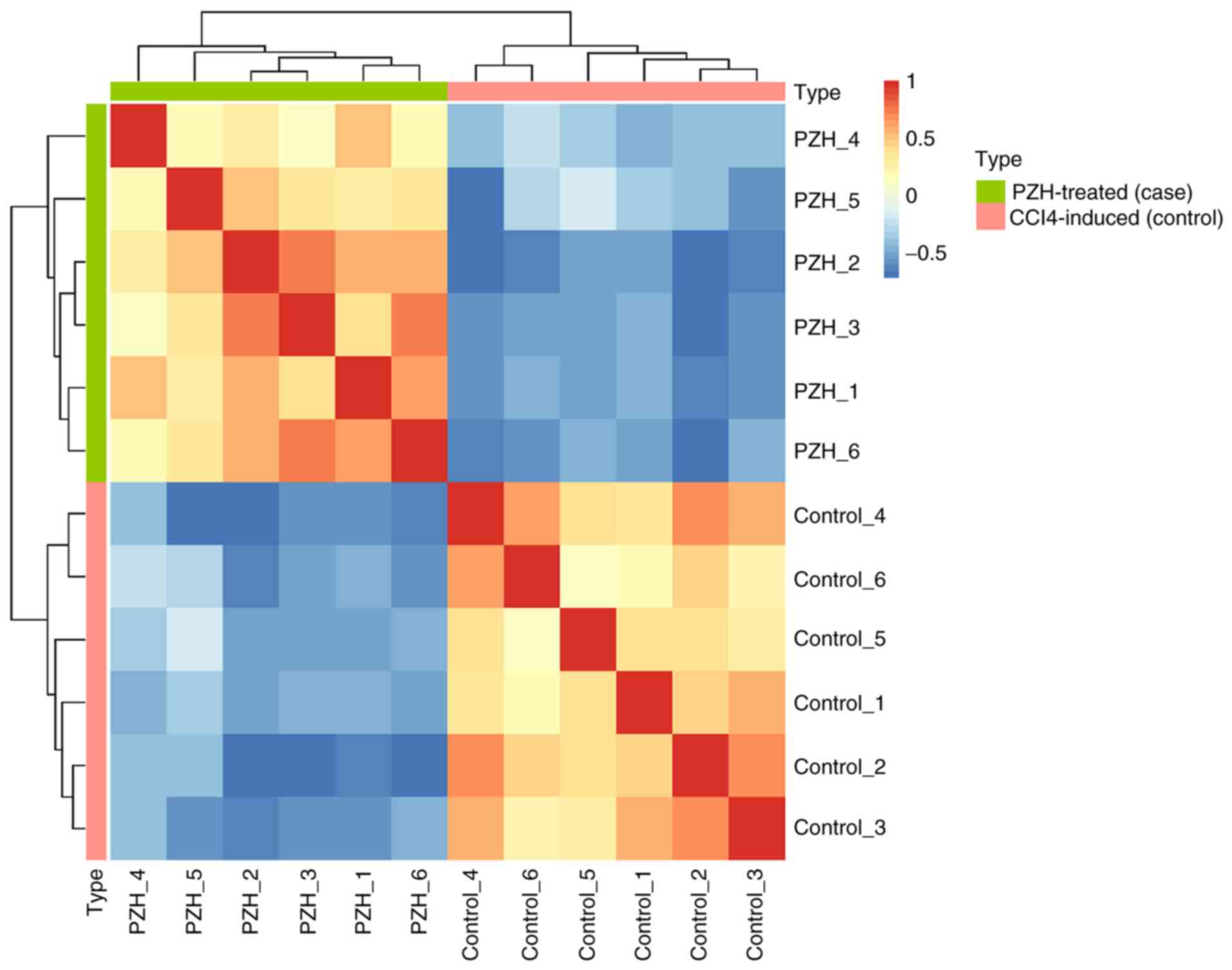

Subsequently, hierarchical clustering was performed using an

expression matrix calculated from each circRNA across 12 samples.

The CCL4-induced and PZH-treated fibrotic liver samples

were classified into different branches (Fig. 1). The SRPBM expression values of

each circRNA for all samples are shown in Table SIII.

| Table I.Quality control results for all

samples. |

Table I.

Quality control results for all

samples.

| Sample | Reads count | Base count | Error,

%a | Q20, %b | Q30, % | GC, %c |

|---|

| PZH_1 | 81068764 | 10516643897 | 0.0118 | 98.28 | 95.46 | 57.29 |

| PZH_2 | 90141456 | 11798532726 | 0.0119 | 98.25 | 95.41 | 57.20 |

| PZH_3 | 85539612 | 11098006475 | 0.0118 | 98.29 | 95.48 | 57.46 |

| PZH_4 | 89396344 | 11600890156 | 0.0121 | 98.17 | 95.16 | 57.57 |

| PZH_5 | 89704690 | 11682502150 | 0.0121 | 98.14 | 95.14 | 57.70 |

| PZH_6 | 82737206 | 10730442091 | 0.0119 | 98.26 | 95.42 | 57.13 |

| Control_1 | 95957422 | 12581967724 | 0.0120 | 98.16 | 95.26 | 52.03 |

| Control_2 | 79748818 | 10401728633 | 0.0122 | 98.06 | 95.04 | 55.98 |

| Control_3 | 88915072 | 11546488853 | 0.0120 | 98.19 | 95.28 | 56.98 |

| Control_4 | 89463266 | 11634186983 | 0.0120 | 98.12 | 95.26 | 52.62 |

| Control_5 | 99444270 | 12929236537 | 0.0119 | 98.18 | 95.36 | 54.19 |

| Control_6 | 82923014 | 10776422218 | 0.0122 | 97.98 | 94.95 | 53.67 |

| Table II.Mapping ratio statistics of all clean

data. |

Table II.

Mapping ratio statistics of all clean

data.

| Sample | Reads count | Mapped reads | Mapped ratio,

% | Unique mapped

reads | Unique mapped

ratio, % |

|---|

| PZH_1 | 40534382 | 38952915 | 96.10 | 12552203 | 30.97 |

| PZH_2 | 45070728 | 43433153 | 96.37 | 14150855 | 31.40 |

| PZH_3 | 42769806 | 41221377 | 96.38 | 12478538 | 29.18 |

| PZH_4 | 44698172 | 42680427 | 95.49 | 13259939 | 29.67 |

| PZH_5 | 44852345 | 43051071 | 95.98 | 12857153 | 28.67 |

| PZH_6 | 41368603 | 39789422 | 96.18 | 12193014 | 29.47 |

| Control_1 | 47978711 | 42105288 | 87.76 | 14914179 | 31.08 |

| Control_2 | 39874409 | 36838848 | 92.39 | 11268513 | 28.26 |

| Control_3 | 44457536 | 42229515 | 94.99 | 13088832 | 29.44 |

| Control_4 | 44731633 | 39892267 | 89.18 | 13676170 | 30.57 |

| Control_5 | 49722135 | 45379494 | 91.27 | 15213018 | 30.60 |

| Control_6 | 41461507 | 37464042 | 90.36 | 12430113 | 29.98 |

Identification of differentially

expressed circRNAs

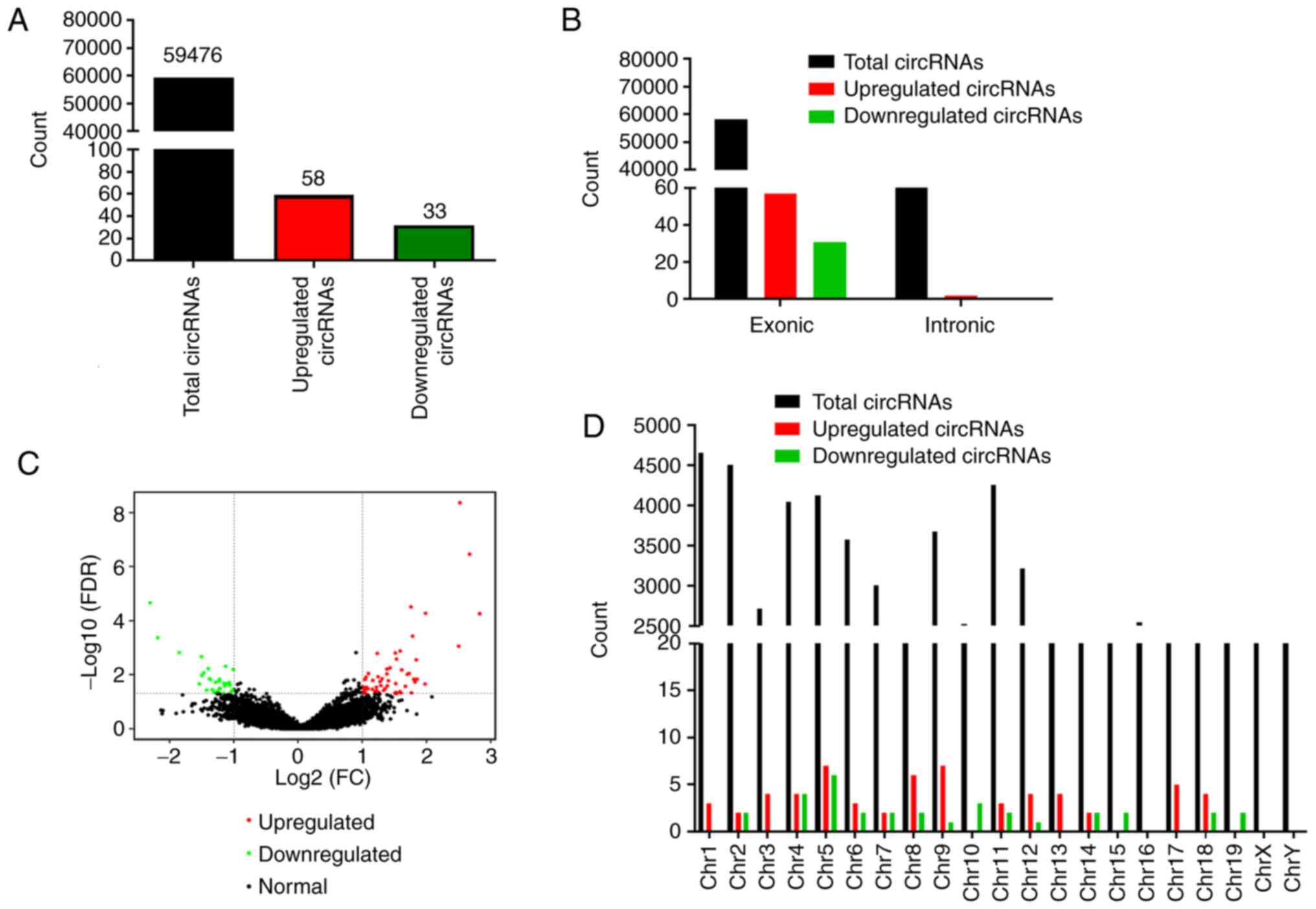

The overall expression profiles of the

differentially expressed circRNAs between the

CCl4-induced and PZH-treated groups are displayed in the

volcano plot in Fig. 2C. In

total, 91 circRNAs, including 58 (63.73%) upregulated and 33

(36.27%) downregulated circRNAs, were demonstrated to be

significantly differentially expressed in liver tissue samples from

the PZH-treated compared with the CCL4-induced group

(Fig. 2A). An analysis of the

source of these circRNAs revealed that, of the 91 differentially

expressed circRNAs, 88 (96.7%) were derived from exons (data not

shown). The results also demonstrated that the most significant

differentially expressed circRNAs were transcribed from the exons

of protein-coding regions (Fig.

2B). The distribution of the identified circRNAs on different

chromosomes was also analyzed. The statistical analysis results

demonstrated that circRNAs were distributed on all chromosomes.

Moreover, all differentially expressed circRNAs were found to be

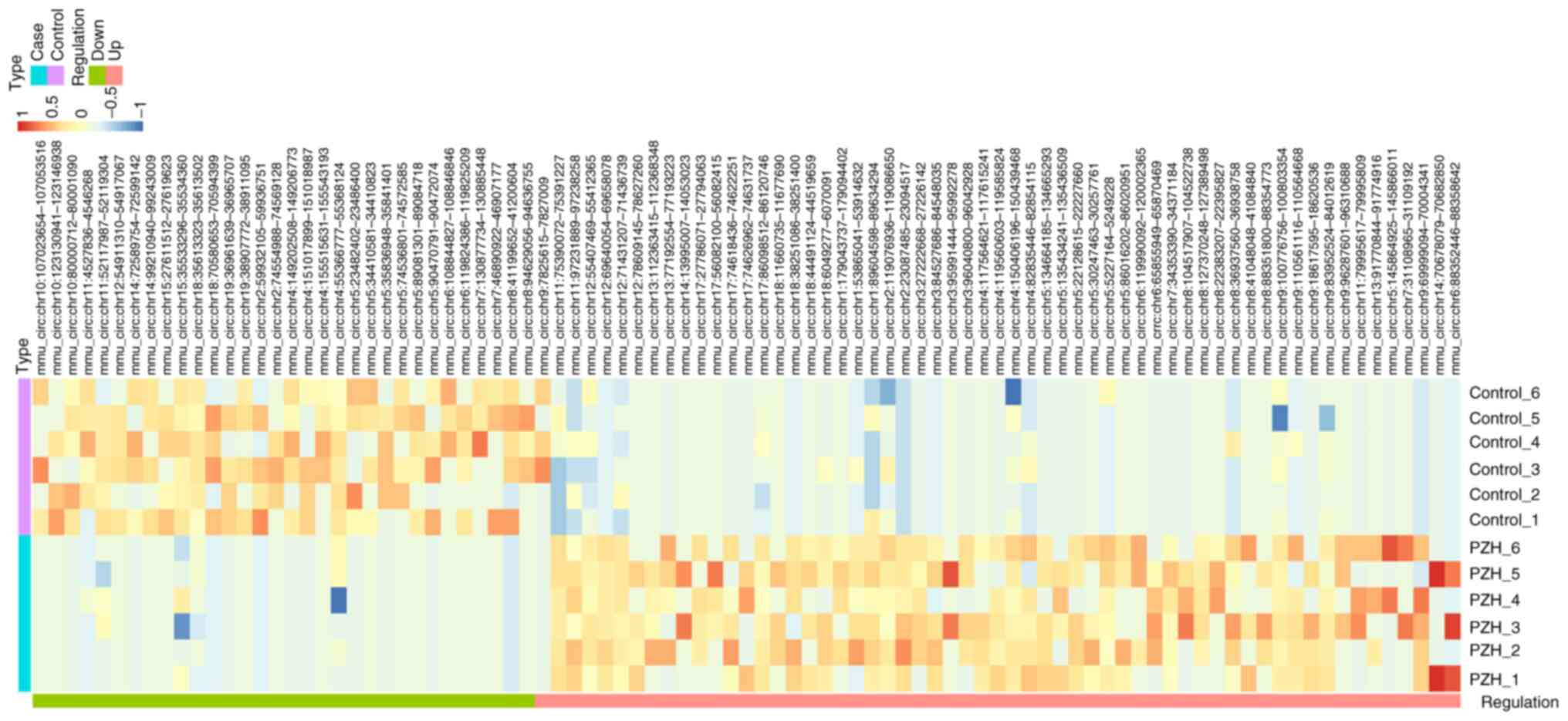

markedly expressed, except for those on chromosome 16 (Fig. 2D). Hierarchical clustering was

also performed to investigate these differentially expressed

circRNAs across 12 samples between PZH-treated and

CCL4-induced groups (Fig.

3). Detailed information on the top 20 differentially expressed

circRNAs is included in Table

SIV. The analysis of the circRNA-seq data suggested that the

expression levels of circRNA differed between PZH treatment and

CCL4-induced fibrotic livers.

Prediction of differentially expressed

circRNA-related target genes and construction of circRNA/miRNA/mRNA

networks

The identification of circRNA target genes is

crucial for characterizing circRNA function. One of the molecular

functions of circRNAs is their role as a ceRNA, which regulate

miRNAs and consequently modulate mRNA expression (24,49). The interactions among circRNA,

miRNA and mRNA were assessed based on the differentially expressed

circRNAs between PZH-treated and the CCl4-inducted

groups; the results showed that the upregulated circRNAs had

interactions with 139 miRNA binding sites and 927 target genes. A

total of 103 potential miRNAs binding sites and 887 target genes of

these miRNAs were also identified on downregulated circRNAs

(Table SV). Multiple

circRNA-related biomarkers associated with liver fibrosis were also

identified using circRNA-seq. However, the number of putative

biomarkers was too large to accurately identify the biomarkers that

may be involved in PZH treatment of liver fibrosis. Therefore, only

the predicted target genes of the differentially expressed circRNAs

were selected for further analysis.

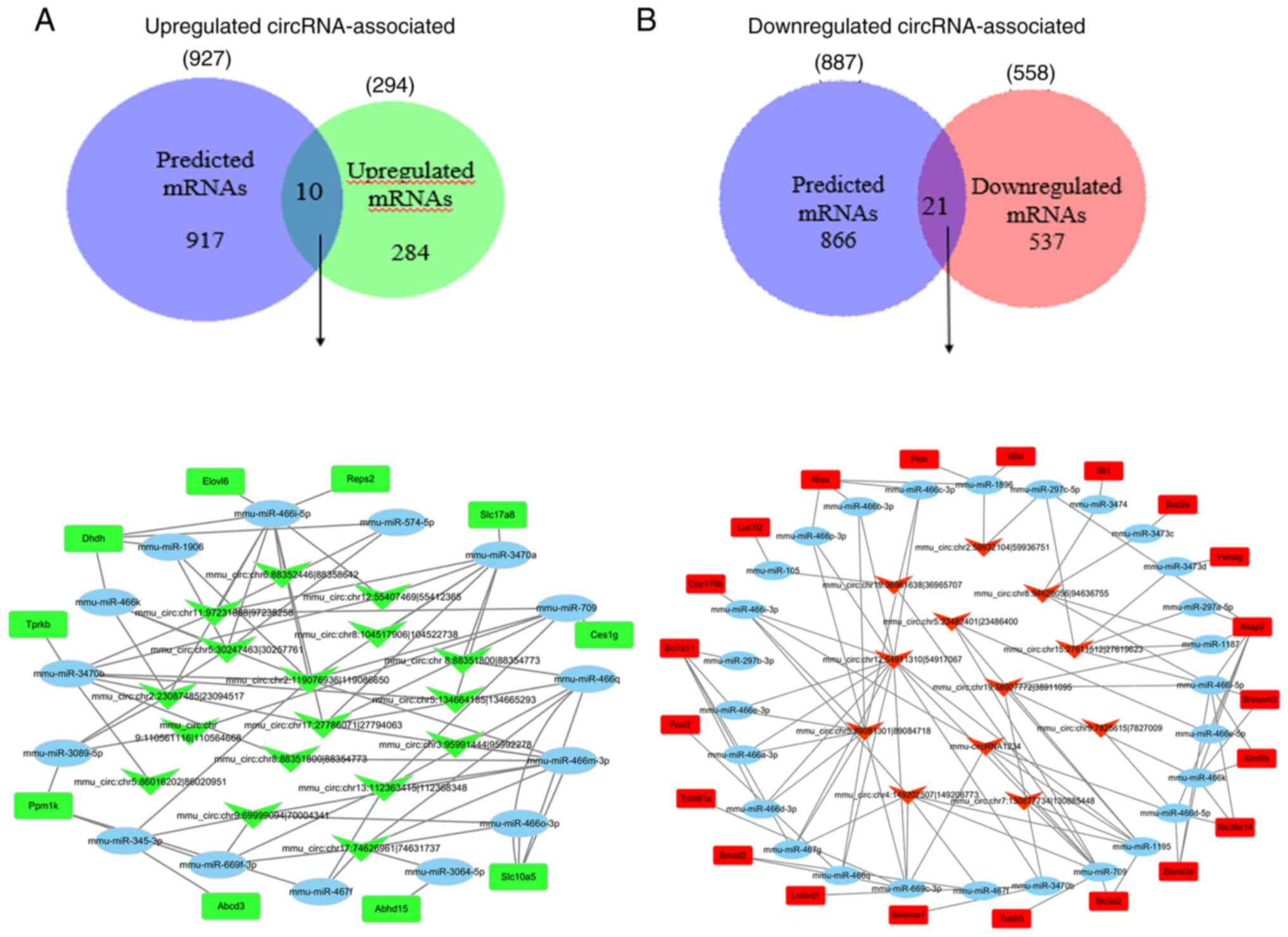

The predicted set of functional genes for up- or

downregulated circRNAs was compared with a set of differentially

expressed mRNA genes enriched in the mRNA-seq data (these mRNAs

were enriched in the same treatment conditions as those in the

present study) (GEO accession no. GSE133481). The shared genes

between these two datasets were recorded. In the upregulated

circRNAs, only 10 overlapping genes from the 927 predicted mRNAs

and 294 upregulated mRNAs from the mRNA-seq data were identified.

Subsequently, the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory network of these

related miRNAs and the corresponding significantly upregulated

circRNA-binding sites were constructed (Fig. 4A). The results demonstrated that

10 upregulated mRNAs were found to interact with 15 miRNAs, which

were involved in the regulation of 17 circRNAs. Among the 15 miRNAs

in the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory network, mmu-miR-466i-5p was

targeted by seven identified upregulated circRNAs and exhibited the

largest interaction network. miR-345-3p was predicted to be

negatively modulated by mmu_circ:chromosome

(chr)9:69999094|70004341 and mmu_circ:chr2:119076936|119086650. The

following top five most upregulated circRNAs appeared to be

associated with the largest binding miRNA network:

mmu_circ:chr17:74626961|74631737,

mmu_circ:chr2:119076936|119086650,

mmu_circ:chr13:112363415|112368348,

mmu_circ:chr17:27786071|27794063 and

mmu_circ:chr9:69999094|70004341. In the downregulated circRNAs, 21

overlapping genes from the 887 predicted mRNAs and 558

downregulated mRNAs from the mRNA-seq data were identified.

Similarly, the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory network of these

related miRNAs and the corresponding significantly downregulated

circRNA-binding sites were constructed (Fig. 4B). The results demonstrated that

21 downregulated mRNAs were found to interact with 27 miRNAs, which

were involved in the regulation of 12 downregulated circRNAs. The

following top five most downregulated circRNAs were found to be

associated with the largest binding miRNA network:

mmu_circ:chr12:54911310|54917067, mmu_circ:chr15:27611512|27619623,

mmu_circ:chr4:149202507|149206773, mmu_circ:chr5:23482401|23486400

and mmu_circ:chr5:89081301|89084718. The expression information for

the dysregulated circRNAs and their related target genes involved

in circRNA/miRNA/mRNA interaction networks are listed in Tables III and IV, respectively. A flowchart

summarizing the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA interaction network associated

with the dysregulated circRNAs, as well as the results of the

subsequent target gene analysis, is displayed in Fig. 5.

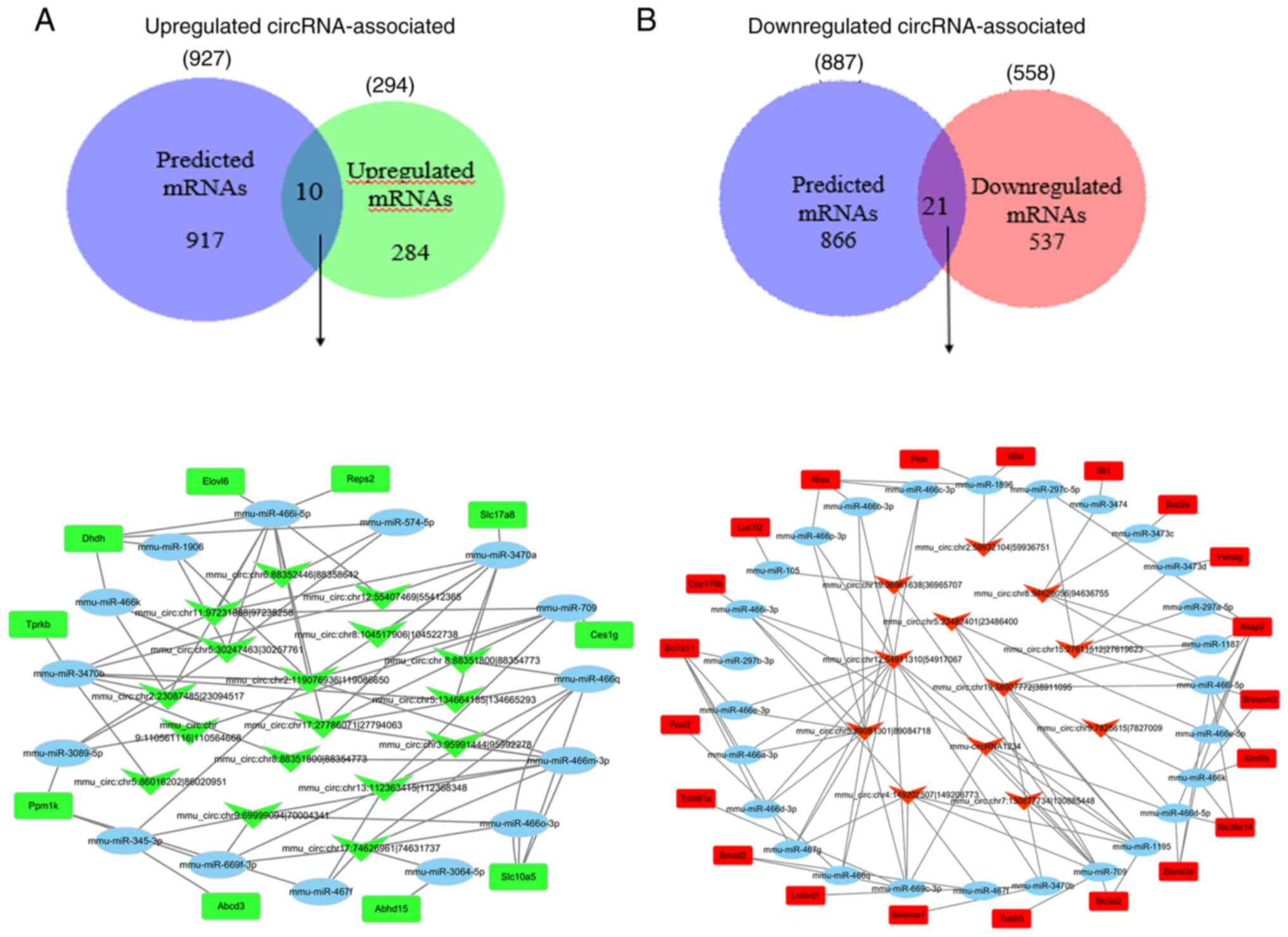

| Figure 4.circRNA-seq data analysis. (A)

Between the upregulated circRNA-related target genes and the

upregulated genes obtained from the mRNA-seq data, 10 overlapping

genes were identified. The circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory network of

their related miRNAs and their corresponding significantly

upregulated circRNA-binding sites was constructed. The network

consisted of 17 circRNAs (arrowheads), 15 miRNAs (ellipses), 10

mRNAs (rectangles) and 75 connections. (B) Between the

downregulated circRNA-related target genes and the downregulated

genes obtained from the mRNA-seq data 21 overlapping genes were

identified. The circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory network of their

related miRNAs and the corresponding significantly downregulated

circRNA-binding sites was constructed. The network consisted of 12

circRNAs (arrowheads), 27 miRNAs (ellipses), 21 mRNAs (rectangles)

and 101 connections. Abcd3, ATP-binding cassette subfamily D,

member 3; Abhd15, abhydrolase domain-containing 15; Akap2,

A-kinase-anchoring protein 2; Baz2a, bromodomain adjacent to

zinc-finger domain 2A; Cep170b, centrosomal protein 170B;

Ces1gES1G, carboxylic ester hydrolase; chr, chromosome; circRNA,

circular RNA; Dhdh, dihydrodiol dehydrogenase; Fktn, fukutin;

Fosl2, FOS-like 2, AP-1 transcription factor subunit; Ifit1,

interferon induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1; Il6st,

interleukin 6 cytokine family signal transducer; Kmt5b, lysine

methyltransferase 5B; Lmbrd1, LMBR1 domain-containing 1; Luc7l2,

putative RNA-binding protein Luc7-like 2; miR, microRNA; seq,

sequencing; mmu, Mus musculus; Nras, NRAS proto-oncogene

GTPase; Ppm1k, protein phosphatase Mg2+/Mn2+

dependent 1K; Serpine1, serpin family E, member 1; Shroom3, shroom

family member 3; Slc3a2, solute carrier family 3, member 2;

Slc7a11, solute carrier family 7, member 11; Slc10a5, solute

carrier family 10, member 5; Slc17a8, solute carrier family 17,

member 8; Slc39a14, solute carrier family 39, member 14; Tprkb,

TP53RK binding protein; TRMT61A, tRNA methyltransferase 61A; Tubb5,

tubulin b class I; Ywhag, tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan

5-monooxygenase activation protein g; Zfand2a, zinc-finger

AN1-type-containing 2A Smad2, SMAD family member 2; Trmt61a, tRNA

methyltransferase 61A; Reps2, RALBP1-associated Eps

domain-containing 2; Elov16, ELOVL fatty acid elongase 6. |

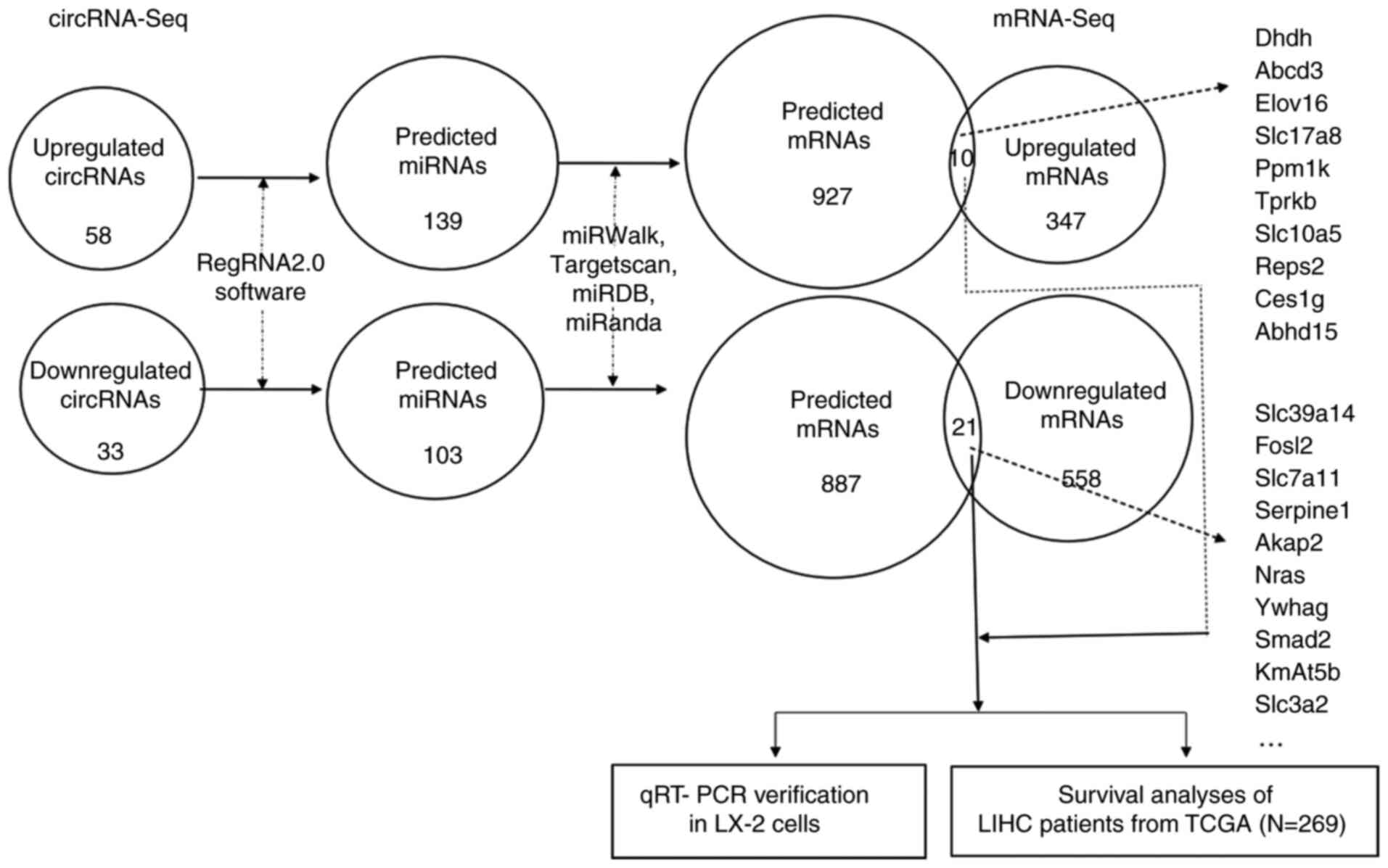

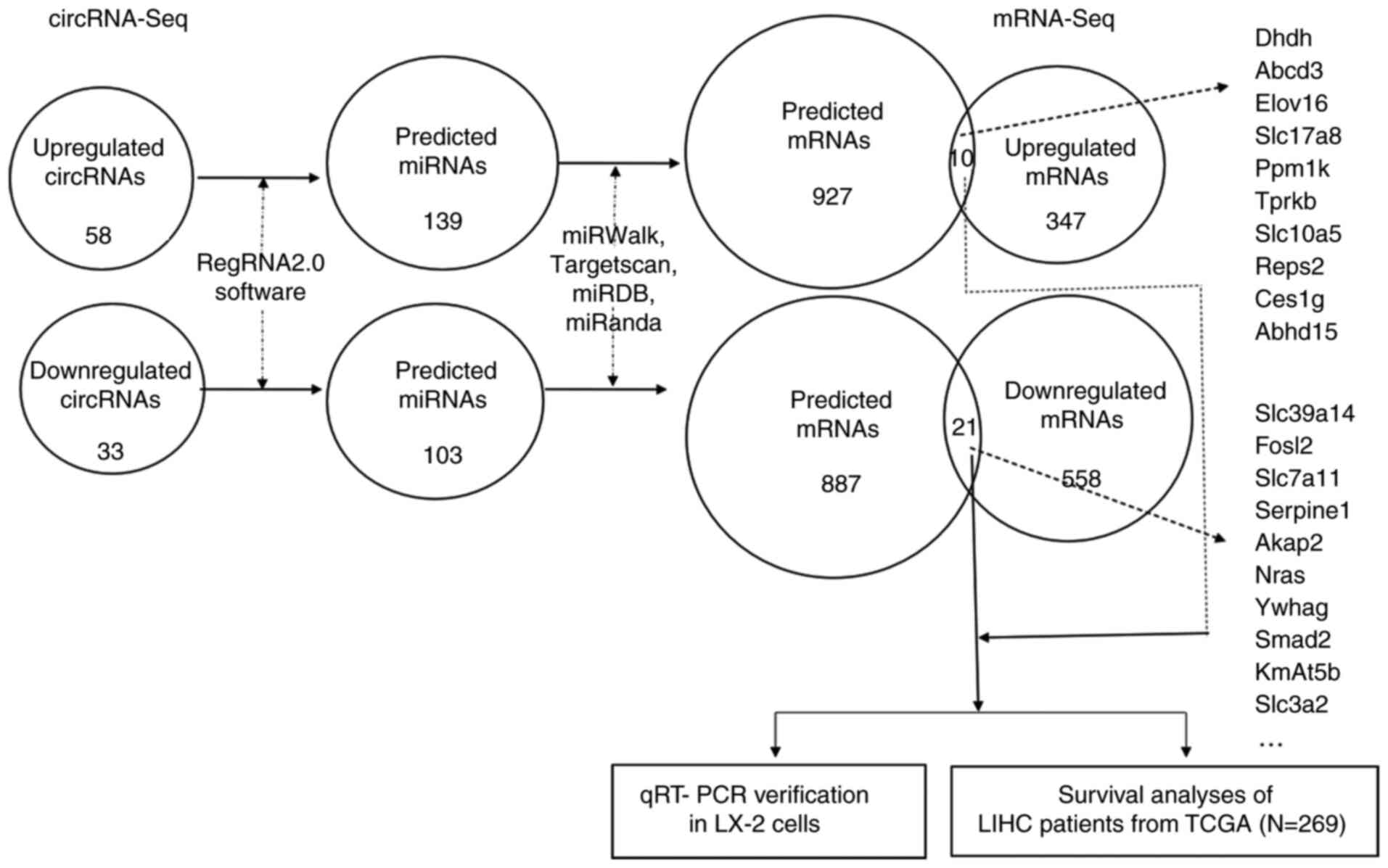

| Figure 5.Bioinformatics analysis and

experimental verification of up- and downregulated circRNAs between

the PZH-treated and untreated control group. The shared mRNAs

between the differentially expressed circRNA-related predicted

target genes in the present study and the differentially expressed

mRNAs from mRNA-seq data (GEO accession no. GSE133481) were

extracted for further analysis. Abcd3, ATP-binding cassette

subfamily D, member 3; Abhd15, abhydrolase domain-containing 15;

Akap2, A-kinase-anchoring protein 2; Ces1g, carboxylic ester

hydrolase; circRNA, circular RNA; Dhdh, dihydrodiol dehydrogenase;

Elov16, ELOVL fatty acid elongase 6; Fosl2, FOS-like 2, AP-1

transcription factor subunit; Kmat5b, lysine methyltransferase 5B;

LIHC, liver hepatocellular carcinoma; miR, microRNA; Nras, NRAS

proto-oncogene GTPase; Ppm1k, protein phosphatase

Mg2+/Mn2+ dependent 1K; PZH, Pien Tze Huang;

Reps2, RALBP1-associated Eps domain-containing 2; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; Serpine1, serpin family E, member

1; seq, sequencing; Slc3a2, solute carrier family 3, member 2;

Slc7a11, solute carrier family 7, member 11; Slc10a5, solute

carrier family, 10 member 5; Slc17a8, solute carrier family 17,

member 8; Slc39a14, solute carrier family 39, member 14; TCGA, The

Cancer Genome Atlas; Tprkb, TP53RK-binding protein; Ywhag, tyrosine

3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein

γ. |

| Table III.Information on identified

dysregulated circRNAs. |

Table III.

Information on identified

dysregulated circRNAs.

| circRNA ID | Gene | Log2

fold-change | Regulation | P-value |

|---|

|

mmu_circ:chr9:69999094|70004341 | Bnip2 | 2.669154139 | Up |

3.41×10−7 |

|

mmu_circ:chr3:95991444|95992278 | Plekho1 | 1.817786326 | Up |

1.82×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr2:119076936|119086650 | Knl1 | 1.020291023 | Up |

4.89×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr2:23087485|23094517 | Acbd5 | 2.518912306 | Up |

4.36×10−9 |

|

mmu_circ:chr6:88352446|88358642 | Eefsec | 2.828790508 | Up |

5.39×10−5 |

|

mmu_circ:chr11:97231888|97238258 | Npepps | 1.851337918 | Up |

1.47×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr5:30247463|30257761 | Selenoi | 1.219232659 | Up |

2.83×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr17:27786071|27794063 | D17Wsu92e | 1.065565101 | Up |

3.40×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr12:55407469|55412365 | Psma6 | 1.056995708 | Up |

4.91×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr5:134664185|134665293 | Limk1 | 1.514958004 | Up |

1.56×10−3 |

|

mmu_circ:chr8:104517906|104522738 | Nae1 | 1.699428017 | Up |

9.48×10−3 |

|

mmu_circ:chr8:88351800|88354773 | Brd7 | 1.258290693 | Up |

4.82×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr17:74626961|74631737 | Birc6 | 1.408138487 | Up |

1.64×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr13:112363415|112368348 | Ankrd55 | 1.086885064 | Up |

3.34×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr9:110561116|110564668 | Setd2 | 1.583016549 | Up |

4.16×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr5:86016202|86020951 | Cenpc1 | 1.286666981 | Up |

2.53×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr8:88351800|88354773 | Brd7 | 1.258290693 | Up |

4.82×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr5:89081301|89084718 | Slc4a4 | −1.033058375 | Down |

4.03×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr12:54911310|54917067 | Baz1a | −1.044583375 | Down |

4.22×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr2:59932104|59936751 | Baz2b | −1.850754348 | Down |

1.53×10−3 |

|

mmu_circ:chr8:94629056|94636755 | Rspry1 | −1.304377354 | Down |

4.43×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr19:36961638|36965707 | Btaf1 | −1.363049915 | Down |

1.51×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr15:27611512|27619623 | Otulin | −1.229226523 | Down |

1.72×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr19:38907772|38911095 | Tbc1d12 | −1.144664409 | Down |

2.61×10−2 |

|

mmu-circRNA1234 | Fndc3a | −1.384170351 | Down |

1.41×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr9:7825615|7827009 | Birc2 | −1.539082966 | Down |

2.21×10−2 |

|

mmu_circ:chr4:149202507|149206773 | Kif1b | −1.503481469 | Down |

2.16×10−3 |

|

mmu_circ:chr5:23482401|23486400 | Kmt2e | −1.397731511 | Down |

5.86×10−3 |

|

mmu_circ:chr7:130877734|130885448 | Plekha1 | −1.335857428 | Down |

3.53×10−2 |

| Table IV.Overlapping genes between

dysregulated circular RNA-associated target genes and

differentially expressed mRNAs. |

Table IV.

Overlapping genes between

dysregulated circular RNA-associated target genes and

differentially expressed mRNAs.

| Gene | Log2

fold-change | Regulation | P-value | Full name |

|---|

| Abcd3 | 1.0280 | Up |

7.92×10−6 | ATP-binding

cassette subfamily D, member 3 |

| Elovl6 | 1.1377 | Up |

2.83×10−4 | ELOVL fatty acid

elongase 6 |

| Slc17a8 | 1.2805 | Up |

2.05×10−6 | Solute carrier

family 17, member 8 |

| Ppm1k | 1.0442 | Up |

4.30×10−4 | Protein

phosphatase, Mg2+/Mn2+ dependent 1K |

| Tprkb | 1.3508 | Up |

2.78×10−2 | TP53RK-binding

protein |

| Slc10a5 | 1.6327 | Up |

1.58×10−6 | Solute carrier

family 10, member 5 |

| Reps2 | 1.1568 | Up |

2.75×10−2 | RALBP1-associated

Eps domain-containing 2 |

| Ces1g | 1.2722 | Up |

6.21×10−5 | Carboxylesterase

1G |

| Dhdh | 1.4262 | Up |

1.26×10−6 | Dihydrodiol

dehydrogenase |

| Abhd15 | 1.1437 | Up |

6.69×10−5 | Abhydrolase

domain-containing 15 |

| Nras | −1.0682 | Down |

3.79×10−2 | NRAS

proto-oncogene, GTPase |

| Baz2a | −1.1493 | Down |

2.07×10−2 | Bromodomain

adjacent to zinc-finger domain 2A |

| Luc7l2 | −1.2942 | Down |

2.23×10−2 | LUC7 like 2,

pre-mRNA splicing factor |

| Ywhag | −1.1007 | Down |

5.95×10−6 | Tyrosine

3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein

γ |

| Serpine1 | −3.3643 | Down |

5.52×10−5 | Serpin family E,

member 1 |

| Zfand2a | −1.2588 | Down |

1.21×10−2 | Zinc-finger

AN1-type-containing 2A |

| Smad2 | −1.1590 | Down |

3.52×10−3 | SMAD family member

2 |

| Kmt5b | −1.4307 | Down |

2.56×10−2 | Lysine

methyltransferase 5B |

| Slc3a2 | −1.5998 | Down |

9.27×10−7 | Solute carrier

family 3, member 2 |

| Trmt61a | −1.0673 | Down |

1.30×10−4 | tRNA

methyltransferase 61A |

| Cep170b | −1.5367 | Down |

7.12×10−3 | Centrosomal protein

170B |

| Slc7a11 | −2.2590 | Down |

1.40×10−5 | Solute carrier

family 7, member 11 |

| Il6st | −1.0635 | Down |

4.03×10−5 | Interleukin 6

signal transducer |

| Ifit1 | −1.0547 | Down |

4.36×10−3 | Interferon-induced

protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 |

| Tubb5 | −1.2318 | Down |

9.96×10−7 | Tubulin, β5 class

I |

| Lmbrd1 | −1.4803 | Down |

2.68×10−2 | LMBR1

domain-containing 1 |

| Fktn | −1.0167 | Down |

4.39×10−3 | Fukutin |

| Akap2 | −1.2242 | Down |

1.25×10−3 | A-kinase anchoring

protein 2 |

| Fosl2 | −1.2528 | Down |

5.73×10−5 | FOS-like 2, AP-1

transcription factor subunit |

| Slc39a14 | −1.0692 | Down |

5.52×10−4 | Solute carrier

family 39, member 14 |

| Shroom3 | −1.2148 | Down |

1.19×10−2 | Shroom family

member 3 |

Host gene enrichment analysis of

differentially expressed circRNA-related target genes

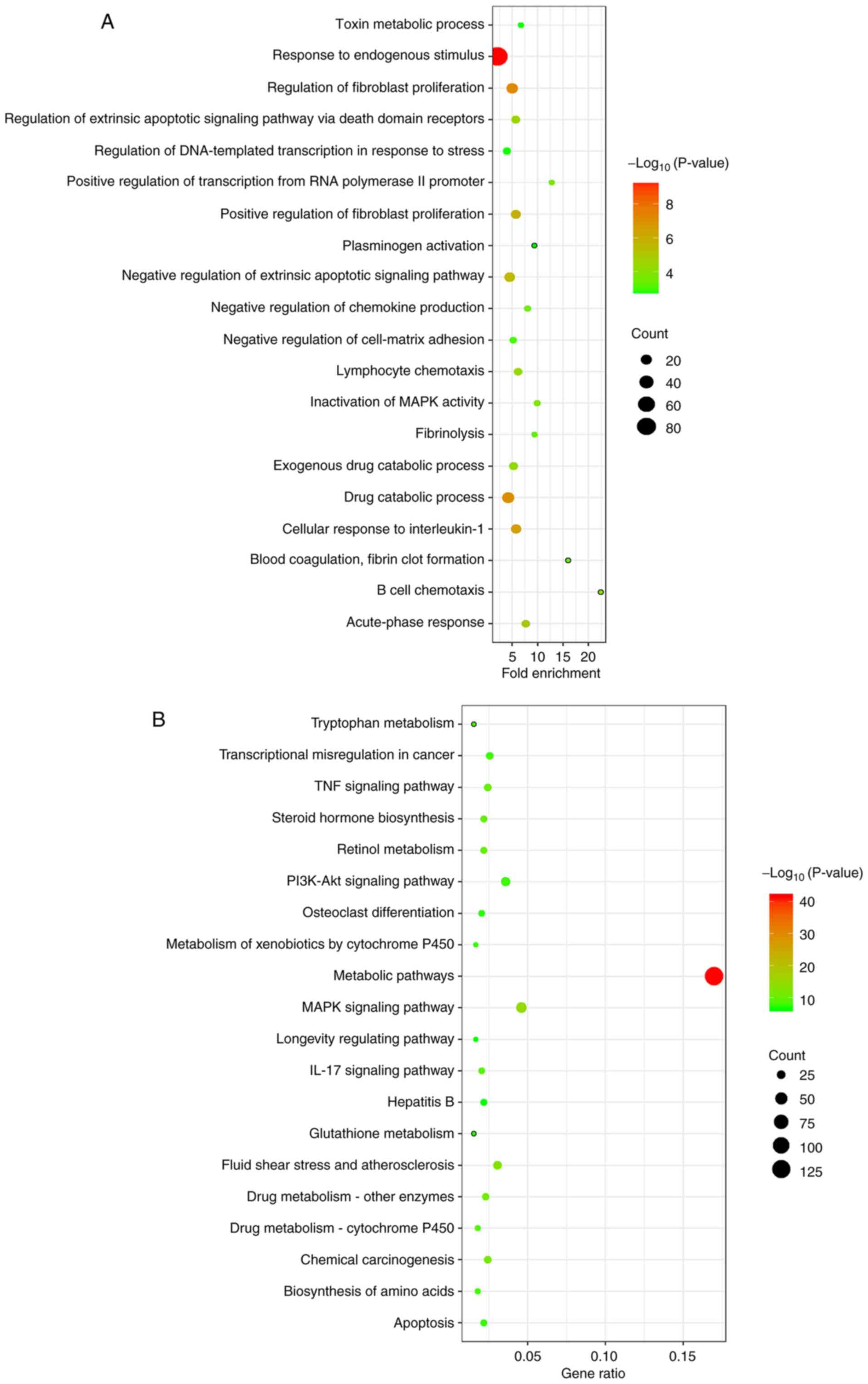

The function of all differentially expressed

circRNA-related target genes was further explored. The GO analysis

results demonstrated that the target genes mainly participated in

the biological processes of ‘positive regulation of fibroblast

proliferation’, ‘response to endogenous stimulus’, ‘drug catabolic

process’ and ‘regulation of DNA-templated transcription in response

to stress’ (Fig. 6A). KEGG

pathways were also identified for differentially expressed

circRNA-related target genes. KEGG analysis identified the

following enriched pathways: ‘Metabolic pathways’, ‘TNF signaling

pathway’, ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’, ‘IL-17 signaling pathway’,

‘MAPK signaling pathway’ and ‘apoptosis’ (P<0.05; Fig. 6B). Meanwhile, the results of GO

pathway analyses showed that the differentially expressed

circRNA-related target genes in this network were associated with

cellular components, such as ‘fibrinogen complex’, ‘transcription

factor AP-1 complex’ and ‘platelet alpha granule’; and molecular

functions, such as ‘ketosteroid monooxygenase activity’ and ‘MAP

kinase tyrosine/serine/threonine and phosphatase activity’

(Fig. S2).

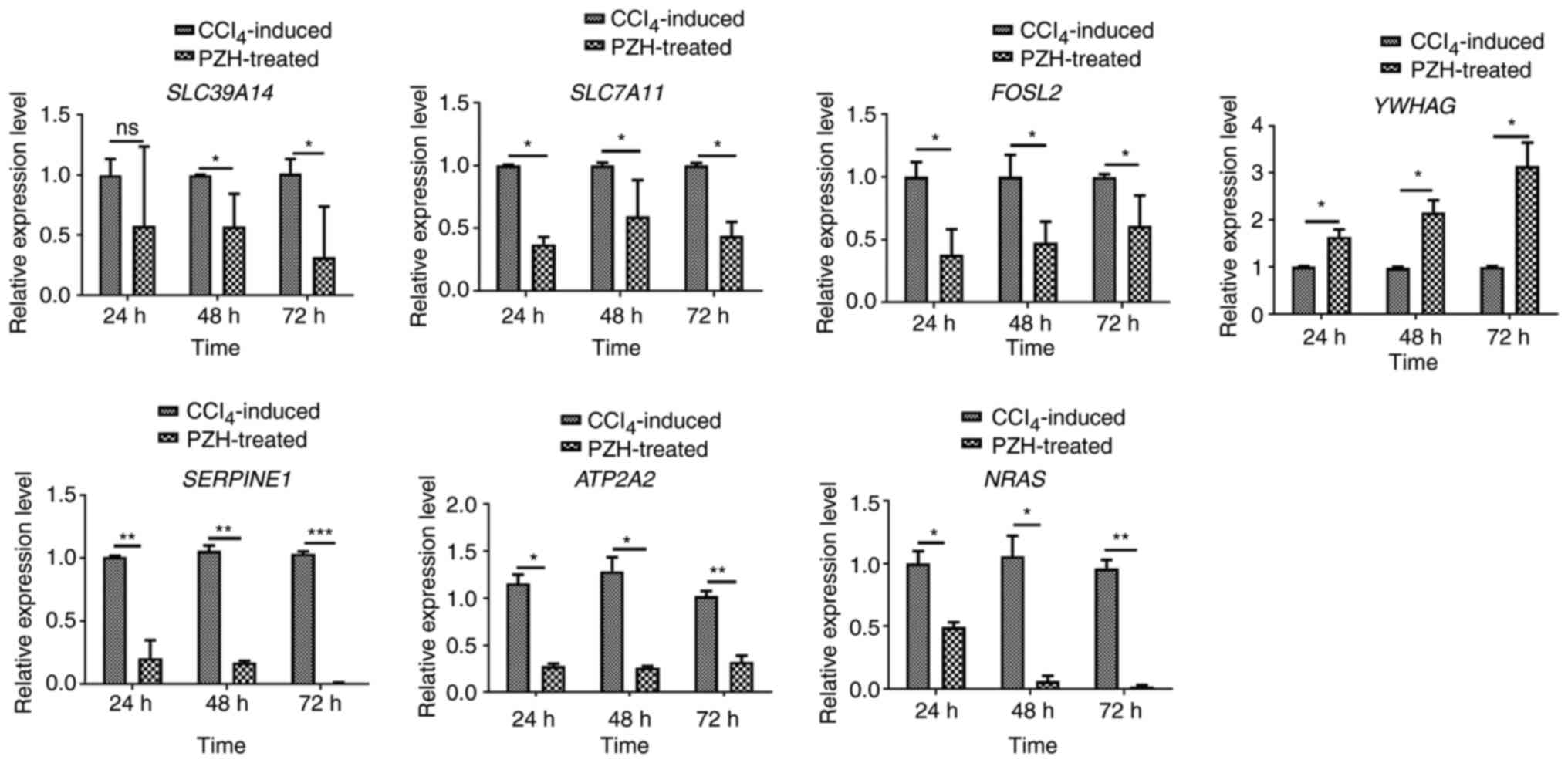

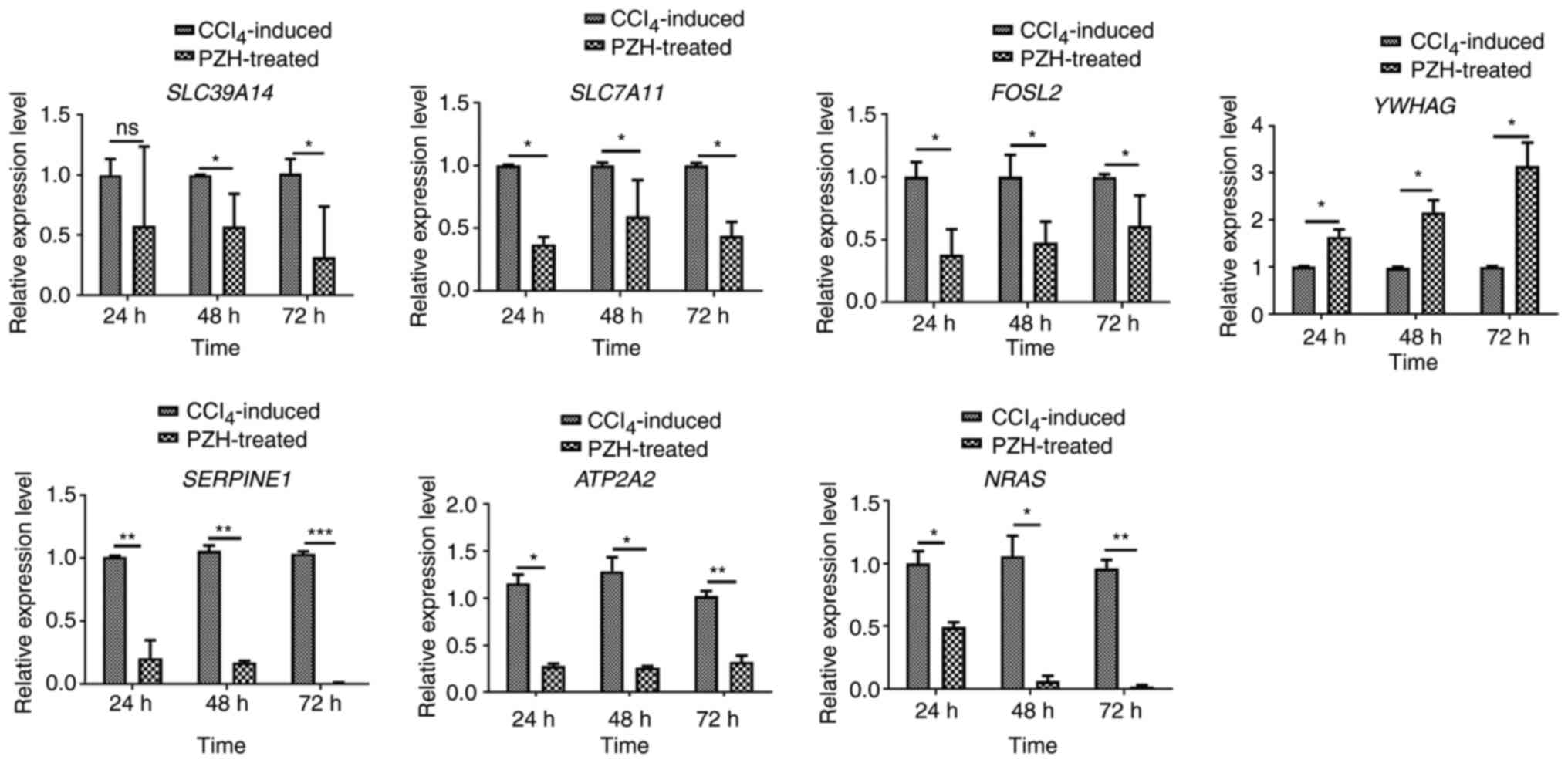

Validation of candidate

circRNA-related target genes by RT-qPCR

To verify the results of the co-expression network

analysis, seven overlapping circRNA-related target gene candidates

were selected for RT-qPCR in LX-2 cells in the

CCL4-induced and PZH-treated group (Table V). mRNA expression levels of the

seven gene candidates were subsequently detected 24, 48 and 72 h

following PZH treatment (0.75 mg/ml). The seven selected

transcripts included: Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan

5-monooxygenase activation protein γ (YWHAG); solute carrier family

39, member 14 (SLC39A14); FOS-like 2, AP-1 transcription factor

subunit (FOSL2); solute carrier family 7, member 11 (SLC7A11);

serpin family E, member 1 (SERPINE1); ATPase

sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ (ATP2A2); and

NRAS proto-oncogene GTPase (NRAS). Among these seven, seven

(SLC39A14, FOSL2, SLC7A11, SERPINE1, ATP2A2 and NRAS) were

significantly differentially expressed compared with the control

(Fig. 7). SLC39A14, FOSL2,

SLC7A11, SERPINE1, ATP2A2 and NRAS mRNA expression levels were

significantly downregulated in the PZH-treated group compared with

the control group, while YWHAG was significantly upregulated.

Overall, the results of the RT-qPCR validation of overlapping

candidate circRNA-related target genes were consistent with the

mRNA-seq results.

| Figure 7.Validation of target genes displayed

in competing endogenous RNA networks in LX-2 cells by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the median ±

SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ATP2A2, ATPase

sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+; FOSL2, FOS-like

2, AP-1 transcription factor subunit; NRAS, NRAS proto-oncogene

GTPase; PZH, Pien Tze Huang; SERPINE1, serpin family E, member 1;

SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7, member 11; SLC39A14, solute

carrier family 39, member 14. |

| Table V.Selected candidate circular

RNA-associated target genes for reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR. |

Table V.

Selected candidate circular

RNA-associated target genes for reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR.

| Genea | Full name | Role in liver

injury | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Slc7a11 | Solute carrier

family 7, member 11 | Induced in

activated hepatic stellate cells | (78) |

| Serpine1 | Serpin family E,

member 1 | Progression of

fibrosis | (79,80) |

| Fosl2 | FOS-like 2, AP-1

transcription factor subunit | Progression of

fibrosis | (67) |

| Atp2a2 | A-kinase anchoring

protein 2 | Progression of

fibrosis | (81) |

| Nras | NRAS

proto-oncogene, GTPase | Progression of

hepatocellular carcinoma | (82) |

| Slc39a14 | Solute carrier

family 39, member 14 | Progression of

fibrosis | (83) |

| Ywhag | Tyrosine

3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein

γ | Progression of

fibrosis | (84) |

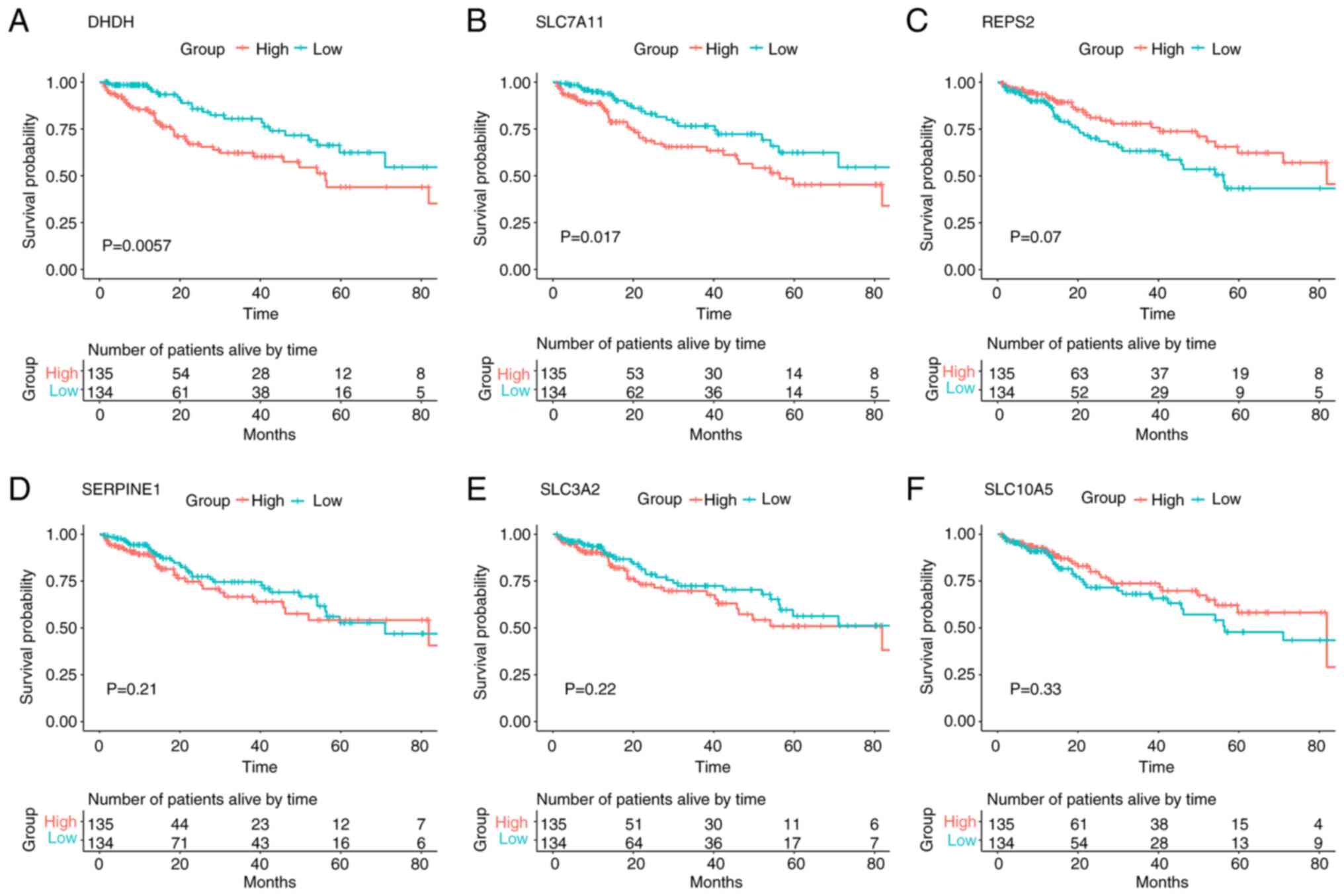

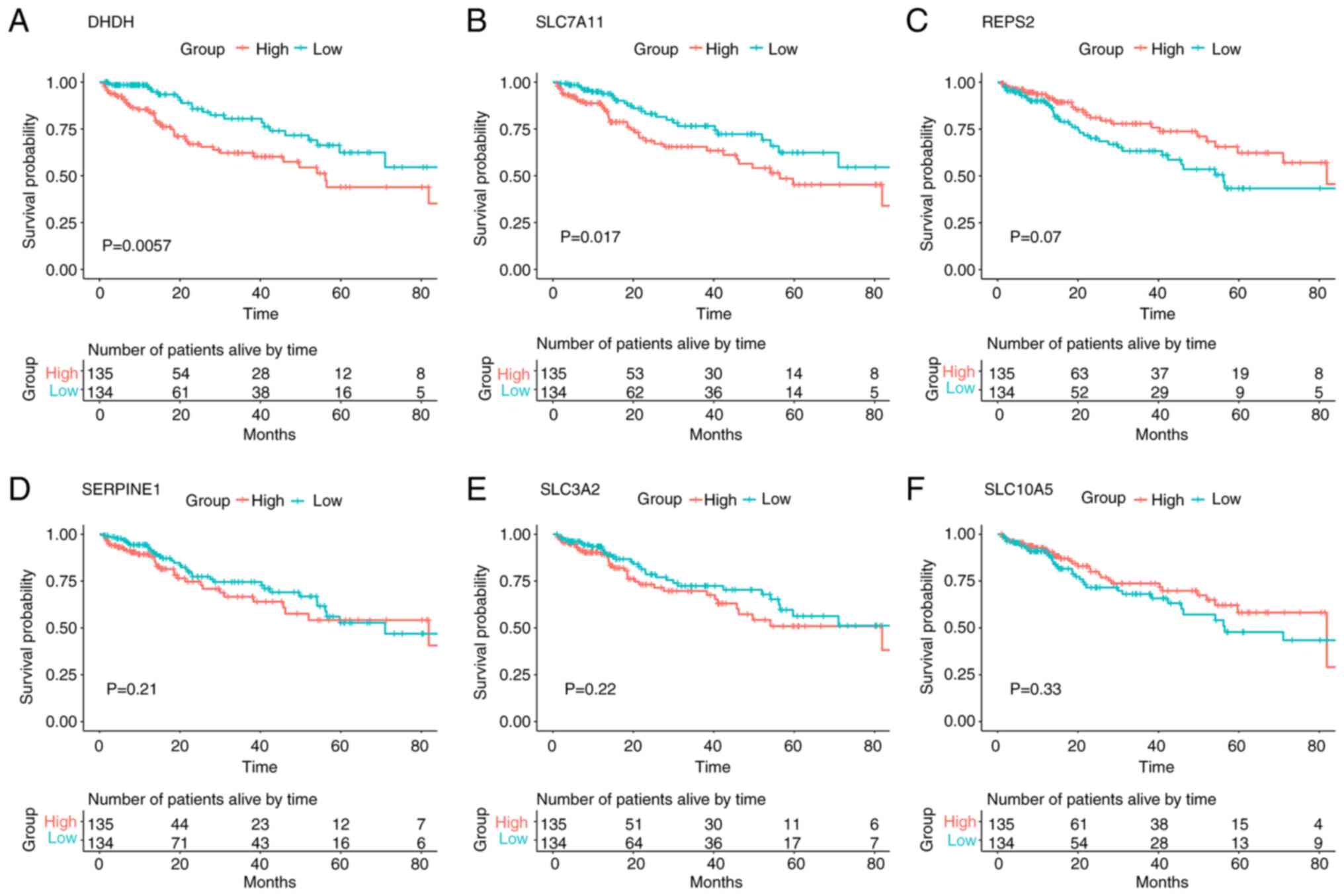

Survival analysis between patient

mortality and differentially expressed circRNA-related target gene

expression levels in liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC)

To explore the relationship between the expression

levels of overlapping functional genes associated with

differentially expressed circRNAs and patient survival, 269

patients with LIHC from TCGA database were divided into low- and

high-expression groups based on the median values. The mRNA

expression of 2 out of the 31 overlapping functional genes was

significantly associated with patient survival in LIHC (Fig. 8). These were dihydrodiol

dehydrogenase (DHDH) and SLC7A11. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

demonstrated that patients with low DHDH expression levels

exhibited a greater survival rate compared with those with high

DHDH expression levels (log-rank test, P=0.0057; Fig. 8A). The results for DHDH were also

consistent with the survival rate of patients with LIHC based on

SLC7A11 mRNA expression analysis (log-rank test, P=0.017; and

Fig. 8B). However, Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis of the remaining genes, including

RALBP1-associated Eps domain-containing 2 (REPS2), SERPINE1, solute

carrier family 3, member 2 (SLC3A2) and solute carrier family 10,

member 5 (SLC10A5), indicated that although the difference in LIPC

survival rates between high-expression and low-expression groups

was not statistically significant (log-rank test, P=0.07, P=0.21,

P=0.22 and P=0.33, respectively), the mRNA expression levels of

these genes were still closely associated with the survival of the

patients (Fig. 8C-F).

| Figure 8.Kaplan-Meier survival analysis

between the patient clinical outcomes and circular RNA-related

target genes. (A) DHDH, (B) SLC7A11, (C) REPS2, (D) SERPINE1, (E)

SLC3A2 and (F) SLC10A5 gene expression levels in 269 patients with

liver hepatocellular carcinoma from The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort

were used to plot survival curves produced using Kaplan-Meier

survival analysis. Patients exhibiting gene expression levels

higher than the median values were assigned to the high-expression

group, whereas those exhibiting mRNA expression levels lower than

the median values were assigned to the low-expression group. The

log-rank test was used to compare the difference in survival rates

between the high- and low-mRNA expression groups. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

DHDH, dihydrodiol dehydrogenase; REPS2, RALBP1-associated Eps

domain-containing 2; SLC3A2, solute carrier family 3, member 2;

SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7, member 11; SLC10A5, solute

carrier family 10, member 5; SERPINE1, serpin family E, member

1. |

Discussion

Traditional Chinese Medicine PZH has attracted

considerable attention due to its marked therapeutic effect on

liver injury (15,16). PZH exposure has been reported to

significantly reduce cell necrosis and swelling, microvesicular

steatosis and lymphocyte infiltration in the injured liver

(50). Previous studies have

shown that PZH may affect the immune system by interfering with the

expression of functional genes in immune-related pathways in

CCl4-induced mice (15,50). CCl4 is the mostly used

reagent for the induction of liver injury animal models. Our

previous study demonstrated that the ratio of positive Sirius red

staining against the total area was significantly decreased in the

PZH treatment group compared with the non-treatment group using

Sirius red staining (39). These

results prompted us to explore potential molecular mechanisms

underlying these observed effects in a PZH-treated

CCl4-induced liver injury model. circRNAs have certain

advantages in the development and application of new clinical

diagnostic markers, for example, Ye et al found that

circRNAs participate in the pathogenesis of hepatic injury and

providing efficient targets in the therapy against liver injury

(28), and increasing number of

studies have reported that circRNAs may act as miRNA sponges to

regulate disease occurrence and development (21,24,49). However, to the best of our

knowledge, there are currently no studies on the regulatory

mechanisms of differentially expressed circRNAs in PZH-treated

liver damage using RNA-seq technology. Therefore, mining circRNA

transcript expression profiles using RNA-seq is important for

exploring the pathological mechanism of PZH in the treatment of

liver diseases, especially liver fibrosis. In the present study,

circRNA-seq and bioinformatic analyses were used to explore the

function of circRNAs in PZH-treated mice with liver fibrosis. The

circRNA expression profile identified 91 differentially expressed

circRNAs between the PZH-treated and CCl4-induced

groups, of which 58 were upregulated and 33 were downregulated. To

the best of our knowledge this was the first study to provide

evidence that circRNAs are differentially expressed in PZH-treated

fibrotic liver tissue compared with the controls, which used

CCl4 only.

CircRNAs act as miRNA sponges that regulate target

gene expression by binding to miRNAs (24). The present study predicted that

there were 242 miRNA-binding sites on circRNAs and 994

differentially expressed circRNA-related target genes using related

software, and these results were similar to previous reports in

human studies (26,27,29). To gain insights into the function

of differentially expressed circRNAs, GO term and KEGG pathway

enrichment analyses were performed. From the KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis, it was determined that all differentially

expressed circRNA-related target genes were found to be involved in

several crucial pathways, including ‘metabolic pathways’, ‘TNF

signaling pathway’, ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’, ‘IL-17 signaling

pathway’, ‘MAPK signaling pathway’ and ‘apoptosis’. Previous

studies have reported that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is

important for HSC activation and apoptosis, as well as the

regulation of proliferation in liver fibrosis (51–53). Shu et al (54) demonstrated that the inhibition of

the MAPK signaling pathway alleviates CCl4-induced liver

fibrosis in Toll-like receptor 5-deficient mice. Furthermore,

Ghallab et al (55)

identified that the TGF-β and TNF-α inflammatory pathways were

activated by influencing lobular zonation of liver fibrosis.

Moreover, the activation of the IL-17 signaling pathway may inhibit

the development of liver fibrosis (56,57). It can therefore be hypothesized

that the differential expression of circRNAs in these signaling

pathways serves an important role in PZH-induced improvement in the

fibrotic liver.

In the present study, a co-expression network was

constructed based on the circRNA-seq and mRNA-seq data to

investigate their interactions. The predicted set of functional

genes for up- or downregulated circRNAs overlapped with a set of

differentially expressed mRNA genes. In the upregulated circRNAs,

10 overlapping genes were identified and the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA

regulatory network of 15 related miRNAs and a corresponding 17

significantly upregulated circRNA-binding sites on these miRNAs was

constructed. Hyun et al (58) demonstrated that miR-466i-5p was

significantly upregulated in the CCl4-induced liver

fibrosis model group, which further aggravated the activation of

HSCs and induced liver fibrosis. Another report suggested that

ELOVL fatty acid elongase 6 (ELOV16) expression was significantly

downregulated in human lungs with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

(59). The results of the present

study indicated that seven of the identified upregulated circRNAs

may serve an important role in the therapeutic effect of PZH in the

fibrotic liver by decreasing the expression levels of miR-466i-5p

and further increasing those of ELOV16. Previous studies have also

reported that miR-345-3p upregulation is involved in the

pathogenesis of liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

by negatively regulating cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 in

cancer cells (57,60). This result indicated that the

overexpression of these two circRNAs may induce pulmonary fibrosis

by decreasing miR-345-3p expression levels and consequently

increasing that of ATP-binding cassette subfamily D, member 3. In

the downregulated circRNAs, 21 overlapping genes were identified

and the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory network of 27 related miRNAs

and the corresponding 12 significantly downregulated

circRNA-binding sites on these miRNAs was constructed. A previous

study reported that miRNA-105 expression is markedly downregulated

in both HCC cell lines and clinical HCC tissues, compared with

normal human hepatocyte and adjacent non-cancerous tissues

(61). The results of the present

study found 12 significantly downregulated circRNA-binding sites in

PZH-treated fibrotic livers in model mice. An et al

(62) demonstrated that miR-467f

is downregulated in acute liver failure compared with mock-treated

livers. Furthermore, the increased expression of SMAD2 has been

demonstrated to serve a vital role in the development of liver

fibrosis (63). The results of

the present study indicated that downregulated

mmu_circ:chr4:149202507|149206773 may participate in the

therapeutic effects of PZH on the fibrotic liver by decreasing the

expression of SMAD2. Overall, these results demonstrated that

differentially expressed circRNAs may alter the expression of

certain functional genes via the circRNA/miRNA/mRNA regulatory

network, therefore mediating PZH-treated liver fibrosis. It was

therefore hypothesized that differentially expressed circRNAs may

act as miRNA sponges and serve an important role in PZH-treated

liver fibrosis by preventing miRNAs from regulating their target

mRNAs.

The RT-qPCR data for the six differentially

expressed circRNA-related target genes in the LX-2 cell model were

consistent with the trends observed in the mRNA-seq data. Among the

verified genes, SLC7A11 was the one most widely investigated in

liver damage. It has previously been reported that inhibiting

SLC7A11 induces ferroptosis in myofibroblastic HSCs and protects

against liver fibrosis (64).

Zhang et al (65) reported

that the upregulation of SLC7A11 is an indicator of unfavorable

prognosis in liver carcinoma. Furthermore, SERPINE1 has been

demonstrated to serve an important role in the development of liver

fibrosis. Lodder et al (66) found that increased expression of

gene SERPINE1 aggravating the degree of liver fibrosis, liver cell

damage and inflammation in myeloid cells. A previous study also

demonstrated that homolog Fos-related antigen 2, encoded by FOSL2,

is a contributing pathogenic factor of pulmonary fibrosis in humans

(67). Furthermore, NRAS is a

proto-oncogene, whose activating mutation has been linked to

several types of human cancer, including HCC (68,69). Previous studies have demonstrated

that sustained NRAS activation resulting from the overexpression of

constitutively active NRAS, induces HCC in genetically compromised

mice (70,71). In the present study, the results

of the RT-qPCR validation of the differentially expressed

circRNA-related target genes (SLC7A11, SERPINE1, FOSL2, NRAS,

SLC39A14 and ATP2A2) corresponded to the mRNA-seq results. These

results further suggested that the differentially expressed

circRNAs acted as miRNA sponges in the regulation of target gene

expression to influence the effects of PZH-treatment on liver

fibrosis.

To explore the association between the

differentially expressed circRNA-related targets and the survival

time of patients with LIHC, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was

performed using data from the TCGA (n=269). The upregulated genes

in PZH-treated liver fibrosis (SLC7A11 and DHDH) were found to be

significantly positively associated with patient survival. Yue

et al (72) reported that

SLC7A11 served an important role in HCC as a potential prognostic

indicator and its overexpression promoted HCC development.

Furthermore, SLC7A11 may be a prognostic factor for liver

carcinoma, as indicated by the survival analysis (73). Elevated levels of plasminogen

activator inhibitor-1 (the protein product of SERPINE1) have been

reported in patients with viral infection-related HCC (74). A number of studies have also

indicated that SERPINE1 may contribute to cancer dissemination

mechanisms, including the prevention of excessive ECM degradation,

modulation of cell adhesion and stimulation of angiogenesis and

cell proliferation (75,76). Wu et al (77) reported that SLC3A2 was highly

expressed in the human HCC cell membrane and may serve an important

role in promoting tumor metastasis and HCC progression. Overall,

these results indicated that a specific set of differentially

expressed circRNA-related functional genes may act as therapeutic

targets for liver injury.

In conclusion, the present study identified 91

differentially expressed circRNAs in a PZH-treated

CCl4-induced liver fibrosis model and the potential

functions of 6 circRNA-related target genes were validated in LX-2

cells. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis further confirmed that two

target mRNAs had potential clinical prognostic value for LIHC.

Meanwhile, a functional circRNA/miRNA/mRNA network was

systematically established to further investigate the underlying

mechanisms of action of differentially expressed circRNAs. Overall,

the present study provided new insights into the mechanisms

underlying the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis and may provide novel

and potentially efficient therapeutic targets against liver injury.

However, a limitation of the present study was that it did not

include any further molecular biology experiments to validate each

of the differentially expressed circRNAs, and thus this will be

investigated future studies.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from The 863 Program (grant

nos. 2012AA02A515 and 2012AA021802), The National Nature Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 81773818, 81273596, 30900799 and

81671326), The National Key Research and Development Program (grant

nos. 2017YFC0909303, 2016YFC0905000, 2016YFC0905002, 2016YFC1200200

and 2016YFC0906400), The 4th Three-year Action Plan for Public

Health of Shanghai (grant no. 15GWZK0101), The Shanghai Pujiang

Program (grant no. 17PJD020), The Shanghai Key Laboratory of

Psychotic Disorders (grant no. 13dz2260500), The Natural Science

Foundation of Fujian Province (grant no. 2016J05210), The Anhui

Medical University for Scientific Research (grant no. XJ201607) and

The Anhui Medical University for Scientific Research (grant no.

2017×kj006).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the

current study are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus

repository, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE150883

(accession no. GSE150883).

Authors' contributions

SQ, FH, LH and JZ designed the study. TW, JZ, DZ,

HW, LC, QX, NZ, YW and LG performed the experiments. TW, LG, JM, MW

and LL performed the data analysis. TW and JZ drafted the

manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. TW and JZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The mice used in the study were obtained from the

Shanghai Southern Model Animal Center. All experimental procedures

were performed in accordance with the guidelines for the Care and

Use of Laboratory Animals at the Chinese Academy of Animal

Sciences. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Shanghai, China;

approval no. IACUC.NO:2017-0033).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The TCM Pien Tze Huang (PZH) was manufactured by

Zhangzhhou Pien Tze Huang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., to which LG and

FH are affiliated as employees. All other authors declare that they

have no competing interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CCl4

|

carbon tetrachloride

|

|

ceRNA

|

competing endogenous RNA

|

|

circRNA

|

circular RNA

|

|

ECM

|

extracellular matrix

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

miRNA/miR

|

microRNA

|

|

PZH

|

Pien Tze Huang

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

seq

|

sequencing

|

References

|

1

|

Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, Huebener

P, Mu X, Dapito DH, Pradere JP and Schwabe RF: Fate tracing reveals

hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis

independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 4:28232013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Schuppan D and Afdhal NH: Liver cirrhosis.

Lancet. 371:838–851. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shrestha N, Chand L, Han MK, Lee SO, Kim

CY and Jeong YJ: Glutamine inhibits CCl4 induced liver fibrosis in

mice and TGF-β1 mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mouse

hepatocytes. Food Chem Toxicol. 93:129–137. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Friedman SL: Hepatic stellate cells:

Protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol

Rev. 88:125–172. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zeisberg M and Kalluri R: Cellular

mechanisms of tissue fibrosis. 1. Common and organ-specific

mechanisms associated with tissue fibrosis. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 304:C216–C225. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wynn TA and Ramalingam TR: Mechanisms of

fibrosis: Therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med.

18:1028–1040. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mansour MF, Greish SM, El-Serafi AT,

Abdelall H and El-Wazir YM: Therapeutic potential of human

umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells on rat model of liver

fibrosis. Am J Stem Cells. 8:7–18. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Uehara T, Pogribny IP and Rusyn I: The DEN

and CCl4-induced mouse model of fibrosis and

inflammation-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Protoc

Pharmacol. 66:14.30.1–10. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Morio LA, Chiu H, Sprowles KA, Zhou P,

Heck DE, Gordon MK and Laskin DL: Distinct roles of tumor necrosis

factor-alpha and nitric oxide in acute liver injury induced by

carbon tetrachloride in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 172:44–51.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Steinman L, Martin R, Bernard C, Conlon P

and Oksenberg JR: Multiple sclerosis: Deeper understanding of its

pathogenesis reveals new targets for therapy. Annu Rev Neurosci.

25:491–505. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Watanabe Y, Tsuchiya A, Seino S, Kawata Y,

Kojima Y, Ikarashi S, Starkey Lewis PJ, Lu WY, Kikuta J, Kawai H,

et al: Mesenchymal stem cells and induced bone marrow-derived

macrophages synergistically improve liver fibrosis in mice. Stem

Cells Transl Med. 8:271–284. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Altamirano-Barrera A, Barranco-Fragoso B

and Méndez-Sánchez N: Management strategies for liver fibrosis. Ann

Hepatol. 16:48–56. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bozic M and Molleston J: Strategies for

management of pediatric cystic fibrosis liver disease. Clin Liver

Dis (Hoboken). 2:204–206. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chen X, Zhou H, Liu YB, Wang JF, Li H, Ung

CY, Han LY, Cao ZW and Chen YZ: Database of traditional Chinese

medicine and its application to studies of mechanism and to

prescription validation. Br J Pharmacol. 149:1092–1103. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhao J, Zhang Y, Wan Y, Hu H and Hong Z:

Pien Tze Huang Gan Bao attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced

hepatocyte apoptosis in rats, associated with suppression of p53

activation and oxidative stress. Mol Med Rep. 16:2611–2619. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yang Y, Chen Z, Deng L, Yu J, Wang K,

Zhang X, Ji G and Li F: Pien Tze Huang ameliorates liver injury by

inhibiting the PERK/eIF2α signaling pathway in alcohol and high-fat

diet rats. Acta Histochem. 120:578–585. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lin W, Zhuang Q, Zheng L, Cao Z, Shen A,

Li Q, Fu C, Feng J and Peng J: Pien Tze Huang inhibits liver

metastasis by targeting TGF-β signaling in an orthotopic model of

colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 33:1922–1928. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lin YC, Chen YC, Chen TH, Chen HH and Tsai

WJ: Acute kidney injury associated with hepato-protective Chinese

Herb-Pien Tze Huang. J Exp Clin Med. 3:184–186. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ragan C, Goodall GJ, Shirokikh NE and

Preiss T: Insights into the biogenesis and potential functions of

exonic circular RNA. Sci Rep. 9:20482019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Koh W, Pan W, Gawad C, Fan HC, Kerchner

GA, Wyss-Coray T, Blumenfeld YJ, El-Sayed YY and Quake SR:

Noninvasive in vivo monitoring of tissue-specific global gene

expression in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:7361–7366. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hansen TB, Jensen TI, Clausen BH, Bramsen

JB, Finsen B, Damgaard CK and Kjems J: Natural RNA circles function

as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature. 495:384–388. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zheng Q, Bao C, Guo W, Li S, Chen J, Chen

B, Luo Y, Lyu D, Li Y, Shi G, et al: Circular RNA profiling reveals

an abundant circHIPK3 that regulates cell growth by sponging

multiple miRNAs. Nat Commun. 7:112152016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu YC, Li JR, Sun CH, Andrews E, Chao RF,

Lin FM, Weng SL, Hsu SD, Huang CC, Cheng C, et al: CircNet: A

database of circular RNAs derived from transcriptome sequencing

data. Nucleic Acids Res. 44D:D209–D215. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F,

Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer

M, et al: Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with

regulatory potency. Nature. 495:333–338. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li Y, Zheng Q, Bao C, Li S, Guo W, Zhao J,

Chen D, Gu J, He X and Huang S: Circular RNA is enriched and stable

in exosomes: A promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res.

25:981–984. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Liang J, Wu X, Sun S, Chen P, Liang X,

Wang J, Ruan J, Zhang S and Zhang X: Circular RNA expression

profile analysis of severe acne by RNA-Seq and bioinformatics. J

Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 32:1986–1992. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lu C, Shi X, Wang AY, Tao Y, Wang Z, Huang

C, Qiao Y, Hu H and Liu L: RNA-Seq profiling of circular RNAs in

human laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 17:862018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ye Z, Kong Q, Han J, Deng J, Wu M and Deng

H: Circular RNAs are differentially expressed in liver

ischemia/reperfusion injury model. J Cell Biochem. 119:7397–7405.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xu H, Wang C, Song H, Xu Y and Ji G:

RNA-seq profiling of circular RNAs in human colorectal cancer liver

metastasis and the potential biomarkers. Mol Cancer. 18:82019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bu Q, Long H, Shao X, Gu H, Kong J, Luo L,

Liu B, Guo W, Wang H, Tian J, et al: Cocaine induces differential

circular RNA expression in striatum. Transl Psychiatry. 9:1992019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ma X, Zhou Y, Qiao B, Jiang S, Shen Q, Han

Y, Liu A, Chen X, Wei L, Zhou L and Zhao J: Androgen aggravates

liver fibrosis by activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in CCl4-induced

liver injury mouse model. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

318:E817–E829. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Schroeder A, Mueller O, Stocker S,

Salowsky R, Leiber M, Gassmann M, Lightfoot S, Menzel W, Granzow M

and Ragg T: The RIN: An RNA integrity number for assigning

integrity values to RNA measurements. BMC Mol Biol. 7:32006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Brown J, Pirrung M and McCue LA: FQC

dashboard: Integrates FastQC results into a web-based, interactive,

and extensible FASTQ quality control tool. Bioinformatics.

33:3137–3139. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Utturkar S, Dassanayake A, Nagaraju S and

Brown SD: Bacterial differential expression analysis methods.

Methods Mol Biol. 2096:89–112. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Dobin A and Gingeras TR: Optimizing

RNA-seq mapping with STAR. Methods Mol Biol. 1415:245–262. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gao Y, Wang J and Zhao F: CIRI: An

efficient and unbiased algorithm for de novo circular RNA

identification. Genome Biol. 16:42015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhang XO, Dong R, Zhang Y, Zhang JL, Luo

Z, Zhang J, Chen LL and Yang L: Diverse alternative back-splicing

and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Res.

26:1277–1287. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Glažar P, Papavasileiou P and Rajewsky N:

circBase: A database for circular RNAs. RNA. 20:1666–1670. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhu J, Zhang D, Wang T, Chen Z, Chen L, Wu

H, Huai C, Sun J, Zhang N, Wei M, et al: Target identification of

hepatic fibrosis using Pien Tze Huang based on mRNA and lncRNA. Sci

Rep. 11:169802021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chang TH, Huang HY, Hsu JB, Weng SL, Horng

JT and Huang HD: An enhanced computational platform for

investigating the roles of regulatory RNA and for identifying

functional RNA motifs. BMC Bioinformatics. 14 (Suppl 2):S42013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P and Gretz N:

miRWalk-database: Prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by

‘walking’ the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform. 44:839–847.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW and Bartel DP:

Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs.

Elife. 4:e050052015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dweep H and Gretz N: miRWalk2.0: A

comprehensive atlas of microRNA-target interactions. Nat Methods.

12:6972015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Adams JM and Cory S: The Bcl-2 apoptotic

switch in cancer development and therapy. Oncogene. 26:1324–1337.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y and He QY:

clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among

gene clusters. OMICS. 16:284–287. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Austin PC, Lee DS and Fine JP:

Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of

competing risks. Circulation. 133:601–609. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

International Cancer Genome Consortium, .

Hudson TJ, Anderson W, Artez A, Barker AD, Bell C, Bernabé RR, Bhan

MK, Calvo F, Eerola I, et al: International network of cancer

genome projects. Nature. 464:993–998. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Piwecka M, Glažar P, Hernandez-Miranda LR,

Memczak S, Wolf SA, Rybak-Wolf A, Filipchyk A, Klironomos F, Cerda

Jara CA, Fenske P, et al: Loss of a mammalian circular RNA locus

causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function. Science.

357:eaam85262017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhao J, Hu H, Wan Y, Zhang Y, Zheng L and

Hong Z: Pien Tze Huang Gan Bao ameliorates carbon

tetrachloride-induced hepatic injury, oxidative stress and

inflammation in rats. Exp Ther Med. 13:1820–1826. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Parsons CJ, Takashima M and Rippe RA:

Molecular mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. J Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 22 (Suppl 1):S79–S84. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Bai T, Lian LH, Wu YL, Wan Y and Nan JX:

Thymoquinone attenuates liver fibrosis via PI3K and TLR4 signaling

pathways in activated hepatic stellate cells. Int Immunopharmacol.

15:275–281. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang J, Chu ES, Chen HY, Man K, Go MY,

Huang XR, Lan HY, Sung JJ and Yu J: MicroRNA-29b prevents liver

fibrosis by attenuating hepatic stellate cell activation and

inducing apoptosis through targeting PI3K/AKT pathway. Oncotarget.

6:7325–7338. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Shu M, Huang DD, Hung ZA, Hu XR and Zhang

S: Inhibition of MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways alleviate carbon

tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis in Toll-like receptor 5

(TLR5) deficiency mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 471:233–239.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ghallab A, Myllys M, Holland CH, Zaza A,

Murad W, Hassan R, Ahmed YA, Abbas T, Abdelrahim EA, Schneider KM,

et al: Influence of liver fibrosis on lobular zonation. Cells.

8:15562019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Meng F, Wang K, Aoyama T, Grivennikov SI,

Paik Y, Scholten D, Cong M, Iwaisako K, Liu X, Zhang M, et al:

Interleukin-17 signaling in inflammatory, Kupffer cells, and

hepatic stellate cells exacerbates liver fibrosis in mice.

Gastroenterology. 143:765–776.e3. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang Y, Huang D, Gao W, Yan J, Zhou W,

Hou X, Liu M, Ren C, Wang S and Shen J: Lack of IL-17 signaling

decreases liver fibrosis in murine Schistosomiasis japonica. Int

Immunol. 27:317–325. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hyun J, Wang S, Kim J, Rao KM, Park SY,

Chung I, Ha CS, Kim SW, Yun YH and Jung Y: MicroRNA-378 limits

activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis by

suppressing Gli3 expression. Nat Commun. 7:109932016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sunaga H, Matsui H, Ueno M, Maeno T, Iso

T, Syamsunarno MR, Anjo S, Matsuzaka T, Shimano H, Yokoyama T and

Kurabayashi M: Deranged fatty acid composition causes pulmonary

fibrosis in Elovl6-deficient mice. Nat Commun. 4:25632013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Shiu TY, Huang SM, Shih YL, Chu HC, Chang

WK and Hsieh TY: Correction: Hepatitis C virus core protein

down-regulates p21Waf1/Cip1 and inhibits curcumin-induced apoptosis

through MicroRNA-345 targeting in human hepatoma cells. PLoS One.

12:e01812992017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Shen G, Rong X, Zhao J, Yang X, Li H,

Jiang H, Zhou Q, Ji T, Huang S, Zhang J and Jia H: MicroRNA-105

suppresses cell proliferation and inhibits PI3K/AKT signaling in

human hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 35:2748–2755. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

An F, Gong B, Wang H, Yu D, Zhao G, Lin L,

Tang W, Yu H, Bao S and Xie Q: miR-15b and miR-16 regulate TNF

mediated hepatocyte apoptosis via BCL2 in acute liver failure.

Apoptosis. 17:702–716. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Koo JH, Lee HJ, Kim W and Kim SG:

Endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatic stellate cells promotes

liver fibrosis via PERK-mediated degradation of HNRNPA1 and

up-regulation of SMAD2. Gastroenterology. 150:181–193.e8. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Du K, Oh SH, Dutta RK, Sun T, Yang WH, Chi

JT and Diehl AM: Inhibiting xCT/SLC7A11 induces ferroptosis of

myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells but exacerbates chronic

liver injury. Liver Int. 41:2214–2227. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Zhang L, Huang Y, Ling J, Zhuo W, Yu Z,

Luo Y and Zhu Y: Overexpression of SLC7A11: A novel oncogene and an

indicator of unfavorable prognosis for liver carcinoma. Future

Oncol. 14:927–936. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Lodder J, Denaës T, Chobert MN, Wan J,

El-Benna J, Pawlotsky JM, Lotersztajn S and Teixeira-Clerc F:

Macrophage autophagy protects against liver fibrosis in mice.

Autophagy. 11:1280–1292. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Eferl R, Hasselblatt P, Rath M, Popper H,

Zenz R, Komnenovic V, Idarraga MH, Kenner L and Wagner EF:

Development of pulmonary fibrosis through a pathway involving the

transcription factor Fra-2/AP-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

105:10525–10530. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Rajalingam K, Schreck R, Rapp UR and