Introduction

The highly specialized pancreatic β-cells are

located in the pancreas in structures called islets of Langerhans

(1). They play a unique and

important role in the physiology of organisms, as they synthesize

the hormone insulin (2). This

protein travels through the bloodstream to reach target peripheral

tissues to promote the uptake, utilization and storage of

nutrients, mainly glucose (3).

Therefore, β-cells are responsible for producing and secreting

insulin under tight regulation, which helps maintain circulating

glucose concentrations in the physiological range (1).

Insulin release is carefully regulated through a

feedback system that involves both insulin-sensitive tissues and

β-cells. The demand for insulin depends on physiological and

pathological conditions, such as aging, pregnancy and obesity.

Therefore, β-cells must adapt to these conditions by activating

different mechanisms, such as hyperplasia and hypertrophy, as well

as increasing insulin synthesis and secretion (2). In situations of metabolic stress, the

demand for insulin increases, and β-cells initially release more

insulin to respond to this demand. However, β-cell functions tend

to decline in response to this stress, resulting in decreased

glucose tolerance (3). Since

insulin plays a fundamental role in regulating glucose metabolism,

any alteration in its secretion, action, or both can generate a

series of metabolic imbalances characterized by chronic

hyperglycemia known as diabetes mellitus (DM) (2,3).

DM represents a serious public health problem

worldwide (4). In recent decades,

the health and economic burdens of DM have increased worldwide,

significantly impacting low- and middle-income countries (5). The 10th edition of the IDF Diabetes

Atlas reports a continued global increase in the prevalence of

diabetes; by 2021, 537 million adults (20–79 years) were living

with diabetes, and this number is projected to increase to 643

million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 (6). It has also been reported that by

2021, diabetes was responsible for 6.7 million deaths and that

there were also 541 million adults with glucose intolerance, which

places them at high risk of suffering from diabetes (Fig. 1).

Diabetes can be divided into two main categories: i)

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) and ii) type 2 diabetes (T2D) (7). T1D involves an autoimmune process

that gradually and selectively destroys the β-cells of the

pancreas, leading to total insulin deficiency (7). While T2D encompasses ~90% of all DM

cases, with most presenting with a prediabetic state (7). Tissue sensitivity to the actions of

insulin is reduced, mainly in muscle, liver and adipose tissue

(8). This leads to failure in the

internalization of glucose in response to normal concentrations of

this hormone, which is known as insulin resistance (IR) (8). The clinical manifestations of the

disease occur when β-cells are unable to produce sufficient

compensatory insulin to counteract the resistance of the body to

insulin (9–12). Increased blood glucose can lead to

autoxidation or cross-linking with proteins present in the serum

(protein glycosylation) to give rise to a series of highly reactive

structures termed Amadori compounds (13). Prior to the clinical manifestations

of T2D, the β-cell mass decreases by up to 60% due to the increased

rate of apoptosis (11,12). In this sense, it should be noted

that apoptosis is a form of cell death that occurs in both

physiological and pathological situations in multicellular

organisms and constitutes a common mechanism of cell replacement,

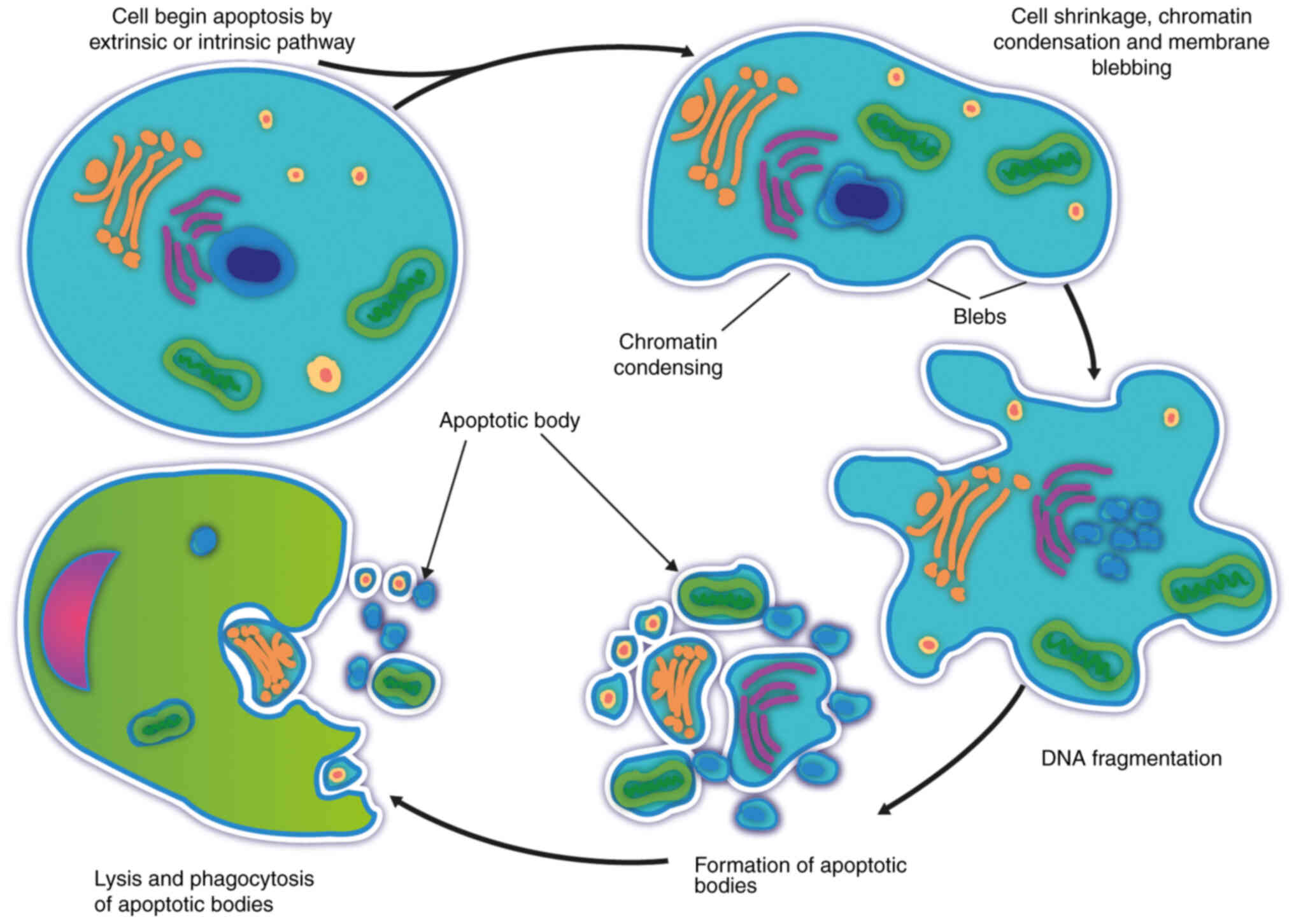

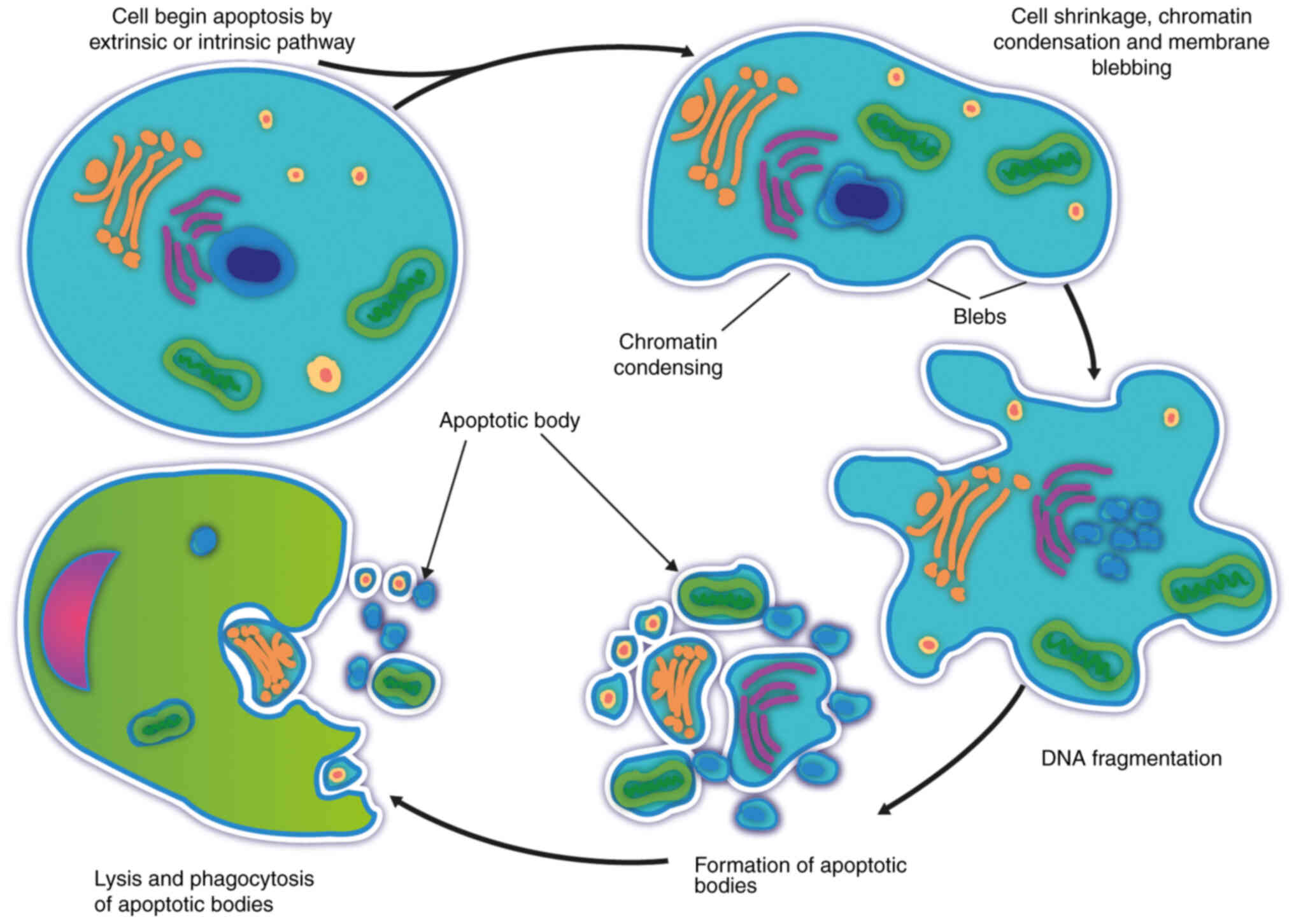

tissue remodeling and renewal of damaged cells (14). Although it is a complex process, it

is characterized by cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, DNA

fragmentation and the formation of apoptotic bodies (Fig. 2) (14). Apoptotic cells are rapidly

phagocytosed by neighboring cells or macrophages, thus preventing

an inflammatory reaction (14,15).

| Figure 2.Cell death by apoptosis. Apoptosis is

a physiological mechanism of programmed cell death that begins with

early chromatin condensation, leading to the formation of

perinuclear chromatin masses and decreased nuclear size, cytoplasm

compaction and cytoskeletal alterations, leading to cellular

shrinkage. In the same way, intranuclear DNA fragmentation occurs,

which leads to fragmentation of the cell, forming small vesicles

called apoptotic bodies still surrounded by a membrane, which

changes its composition, resulting in the translocation of

phosphatidylserine to its surface, which serves as a recognition

signal for macrophages; thus, the bodies are quickly

phagocytosed. |

Various potential mechanisms have been identified to

explain the increase in β-cell apoptosis during T2D, among which

chronic hyperglycemia is a key factor (12). The process of cell death by

apoptosis involves the participation of a series of regulatory

factors. One of the most crucial and widely studied factors in this

process is p53, which functions as the ‘guardian of the genome’

since it plays a fundamental role in the supervision of cellular

stress and in inducing apoptosis in tissues where stressors cause

severe and irreversible damage (16).

Therefore, the present review focuses on the role of

p53 in reducing pancreatic β-cells in the context of hyperglycemia.

It was previously shown that an increase in glucose promotes the

mobilization of p53 toward the mitochondria, increasing the

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by modifying the

mitochondrial membrane potential (17). Therefore, a series of experimental

evidence corresponding to the post-translational modifications of

p53 induced by hyperglycemia has been obtained (Table I). These effects are closely

related to the regulation of apoptosis in the pancreatic β-cell

line RINm5F by high glucose. In addition, the regulation that this

protein undergoes through its ubiquitination by murine protein

double minute 2 (Mdm2) will be analyzed (10,11,18).

| Table I.Characteristics of the main articles

reviewed. |

Table I.

Characteristics of the main articles

reviewed.

| First author/s,

year | Methodology | Results | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ortega-Camarillo

et al, | - Apoptosis index:

FC (PS exposure) | - High glucose

increased apoptosis | (17) |

| 2006 | and DNA

fragmentation | and translocation

of p53 protein |

|

|

| - p53 localization:

WB/IF | to the mitochondria

of RINm5F |

|

|

| - ROS production:

FC (DCDHF-DA) | cells |

|

|

| - ψm: JC-1 confocal

microscopy | - Alterations in ψm

and an increase |

|

|

| - NADPH-oxidase

inhibitors | in NADPH-oxidase

and mito- |

|

|

|

| chondrial ROS were

also observed. |

|

|

|

| - Increased glucose

stimulated p53 |

|

|

|

| mobilization to

mitochondria, ROS |

|

|

|

| production and

pancreatic β-cell death |

|

| Flores-López et

al, | - P-p53, p-p38MAPK:

WB mito- | - Localization of

p53 and its phospho- | (11) |

| 2013 |

chondria/cytosol | rylation in

mitochondria was repressed |

|

|

| - Apoptosis | in RINm5F cells

cultured at high |

|

|

| - Caspase-3;

Bcl-2/Bax ratio and | glucose and with

the p38 MAPK |

|

|

| cyt c: WB

mitochondria/cytosol | inhibitor. |

|

|

| - DNA

fragmentation | - Deletion of p38

MAPK also prevented |

|

|

| - P38 MAPK

inhibitor | mitochondrial

cytochrome c egress and |

|

|

|

| decreased apoptosis

of RINm5F cells |

|

| Flores-López et

al, | -

Phosphorylation | - The localization

and phosphorylation | (18) |

| 2012 | -

O-N-Acetylglucosaminylation and | of p53 at Ser 15

and Ser 392 in mito |

|

|

|

Poly-ADP-ribosylation of P53: IP; | chondria were

associated with an |

|

|

| WB | increase in ROS,

decrease in the Bcl-2/ |

|

|

|

| Bax ratio and

increase in apoptosis. |

|

|

|

| - High glucose

increased PARP concen- |

|

|

|

| tration and

Poly-ADP-ribosylation of |

|

|

|

| p53 in the nuclear

fraction. |

|

|

|

| -

N-acetylglucosaminylation of p53 |

|

|

|

| increases first in

the cytosol and at |

|

|

|

| 24 h in the

mitochondria, together |

|

|

|

| with p53

mobilization to this organelle. |

|

|

|

| - High glucose

induces apoptosis in |

|

|

|

| RINm5F cells in a

time-dependent |

|

|

|

| manner without any

changes of |

|

|

|

| mRNA p53

expression, although |

|

|

|

| alterations occur

in intracellular distri- |

|

|

|

| bution and

phosphorylation. |

|

| Barzalobre- | - p53-Mdm2 complex:

IP; WB; IF | - High glucose

reduced Mdm2 (mRNA | (10) |

| Gerónimo et

al, | - Ub-p53: WB | and protein) but

increased Mdm2 and |

|

| 2015 | - pAkt: WB | Akt

phosphorylation. |

|

|

|

| - It observed

p53-Mdm2 complex form- |

|

|

|

| ation, but p53

ubiquitination was |

|

|

|

| suppressed.

Phosphorylation of p53 |

|

|

|

| Ser15 and ATM was

increased by high |

|

|

|

| glucose. Therefore,

the reduction of |

|

|

|

| pancreatic β-cells

mass is favored by |

|

|

|

| stabilization of

p53 due to reduced |

|

|

|

| expression of Mdm2

and low p53 |

|

|

|

|

ubiquitination. |

|

| Barzalobre- | - Animals drinking

water containing | - Carbohydrate in

drinking water | (9) |

| Geronimo et

al, | either 40% sucrose

or 40% fructose. | promotes apoptosis

and mobilization |

|

| 2023 | - Glucose tolerance

test was per- | of p53 from the

cytosol to the mito- |

|

|

| formed at week

15. | chondria of rat

pancreas β-cells before |

|

|

| - After 4 months

was measured: | blood glucose

rises. An increase in |

|

|

| - Apoptosis:

TUNEL. | p53, miR-34a and

Bax mRNA |

|

|

| - Bax and p53: WB,

IF and qPCR. | (P<0.001) was

detected in the sucrose |

|

|

| - Insulin,

triacylglycerol, serum | group. In addition

to hypertrigly- |

|

|

| glucose and fatty

acids in pan- | ceridemia,

hyperinsulinemia, glucose |

|

|

| creatic tissue were

measured | intolerance,

insulin resistance, accumu- |

|

|

|

| lation of visceral

fat and increased |

|

|

|

| pancreatic fatty

acids in the sucrose |

|

|

|

| group. Carbohydrate

consumption |

|

|

|

| increases p53 and

its mobilization into |

|

|

|

| β-cell mitochondria

and increases the |

|

|

|

| rate of apoptosis,

which occurs before |

|

|

|

| serum glucose

levels increase. |

|

For the present narrative literature review, PubMed

(https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and

Web of Science (https://clarivate.com/products/scientific-and-academic-research/research-discovery-and-workflow-solutions/webofscience-platform/)

were searched using the keywords ‘apoptosis’, ‘pancreatic β-cell

apoptosis and hyperglycemia’, ‘p53 and pancreatic β-cell

apoptosis’, ‘p53 and hyperglycemia’, ‘posttranslational

modifications of p53’, and ‘p53 and ROS’. The most relevant

articles in English were selected and reviewed, and articles that

analyzed the role of p53 in the death of pancreatic β-cells due to

high glucose levels were identified. Also included is the

description of death by apoptosis, as well as other mechanisms

involved in the damage of β-cells due to high glucose levels.

Apoptotic pathways are the crossroads where

signals and regulatory mechanisms converge

Apoptosis constitutes an essential mechanism for the

selective elimination of cells and is integrally involved in

various biological events (19).

This process involves the activation of caspases, a family of

proteases with a cysteine residue in their active site that is key

in the transduction and execution of apoptotic signals in response

to various stimuli (14). They

exist as zymogens (proenzymes) in the cytoplasm, endoplasmic

reticulum, mitochondria and nuclear matrix of most cells (20). The apoptosis process can be

triggered by two fundamental pathways, the extrinsic pathway and

the intrinsic pathway, with both pathways including the activation

of caspases (14,20).

The extrinsic pathway of apoptosis is induced by

death receptors belonging to the superfamily of tumor necrosis

factor (TNF) receptors. Two of the most characterized receptors are

the Fas receptor, also termed CD95 or apoptosis-1 protein, and the

TNF receptor (TNFR). These receptors share a homologous sequence

called the death domain (DD), which can initiate a cascade of

events that lead to apoptosis upon receiving extracellular signals

(Fig. 3) (19). The ligands that bind to these

receptors belong to the TNF family and include the Fas ligand and

TNF. The activated Fas receptor recruits adapter molecules such as

the Fas-associated DD (FADD), which also contains a DD that binds

to the Fas receptor analog domain, and a death effector domain

(DED) that binds to a Fas receptor analog domain of procaspase-8

(14,19). This enzyme, also termed FADD-like

IL-1β-converting enzyme (FLICE), undergoes autocatalytic activation

by binding to FADD, becoming active caspase-8 (21). The complex formed by Fas, FADD and

FLICE is called the death-inducing signaling complex. Caspase-8

activates effector caspases 3, 6 and 7, which in turn release

various cellular proteins involved in proteolysis and DNA

degradation. In the case of TNF receptors (TNFR-I and TNFR-II),

they recruit the adapter molecule TRADD (TNFR-associated death

domain) (21). Thus, the complex

formed by these components activates both initiator caspases (8 and

10) and effector caspases (3, 6 and 7), similar to what is observed

with the Fas receptor (22,23).

| Figure 3.Pathways of apoptosis. There are two

main signaling pathways by which a cell becomes apoptotic. The

extrinsic pathway begins by binding specific ligands to death

receptors on the cell surface, and this interaction leads to the

activation of caspases 8 and 10. The intrinsic pathway begins at

the mitochondrial level and leads to the formation of the

apoptosome, a protein complex that leads to the activation of

caspase-9. Caspases 8, 10 and 9 are known as regulatory caspases,

and when active, they begin an activation cascade of other

molecules, including caspases 3, 6 and 7, which are known as

effector caspases that initiate the proteolytic cascade that leads

to death by apoptosis. TNFR1, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1;

FADD, Fas-associated DD; TRADD, TNFR-associated death domain;

APAF-1, apoptotic protease activating factor 1; Cyt c, cytochrome

c; dATP, deoxyadenosine triphosphate; ROS, reactive oxygen species;

DED, death effector domain; PTP, permeability transition pore; Δψm,

transmembrane potential. |

The intrinsic pathway of apoptosis is triggered by

internal signals that focus on mitochondria (23). In the context of the intrinsic

pathway, there are contact zones between the mitochondrial

membranes, termed ‘dense zones’, whose protein components interact

to form the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP), which

includes proteins of different cellular parts: The cytoplasm

(hexokinase), outer membrane [voltage-gated anion channel (VDAC)],

inner membrane [adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT)] and

mitochondrial matrix [cyclophilin D (CpD)] (24). Under physiological conditions, the

different components of the PTP are scattered (25). Thus, VDAC contributes to the

permeabilization of the outer membrane, ANT specifically controls

the passage of the different phosphorylated and unphosphorylated

forms of adenine nucleotides through the inner membrane, and CpD is

a peptidyl-propyl isomerase that is crucial for protein folding

(26). When an apoptotic stimulus

reaches the mitochondria, these protein components can assemble,

forming a pore with a radius of 1.0–1.3 nm, allowing the

nonselective passage of molecules <1.5 kDa (25). Its opening leads to the

permeabilization of mitochondrial membranes, which contributes to

mitochondrial dysregulation and the loss of transmembrane potential

(Δψm) due to an increase in matrix osmolarity (24). In addition, the entry of water

causes swelling of mitochondria and rupture of the outer membrane,

releasing molecules from the intermembrane space into the cytoplasm

(25). A total of 79 peptide

components that are released during the opening of the PTP have

been characterized (25,26). These components include molecules

with known pro-apoptotic activity, such as cytochrome c (cyt c),

Smac/DIABLO, apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) and

apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), and some members of the caspase

family, such as caspase-2 and caspase-9 (27,28).

Once released into the cytoplasm, these agents can activate

different apoptotic pathways. AIF triggers chromatin condensation

and DNA fragmentation independent of caspase activation (29). The pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and

Bak have been shown to accelerate the opening of VDAC channels and

allow cytochrome c egress, while the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2

and Bcl-XL close these channels by directly binding to Bax and Bak

(30,31). Cytochrome c released into the

cytosol favors the activation of Apaf-1, which can oligomerize in

the presence of cytochrome c and deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP)

(23). The oligomers recruit

procaspase-9 using the recruitment domain of Apaf-1, thus forming

the apoptosome (23). Mature

caspase-9 is released from the complex and activates effector

caspases 3, 6 and 7, leading to the initiation of the proteolytic

cascade essential for apoptosis (15,27,32).

Glucolipotoxicity and p53 activation

Among the mechanisms involved in the induction of

damage to pancreatic β-cells, those related to the combination of

hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia are the most studied. This is

justified by the exacerbated increase in the number of obese

people, including infants, worldwide. An increase in free fatty

acids (FFAs) in the circulation combined with IR and hyperglycemia,

which are frequently observed in individuals with obesity,

constitutes a state known as glucolipotoxicity and is involved in

the pathogenesis of T2D (33).

Excessive and chronic accumulation of fatty acids

inhibits insulin secretion in response to glucose and increases the

intracellular production of lipid intermediates, which are toxic to

β-cells and activate apoptosis (34). In these circumstances, the activity

of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 decreases due to the increase

in malonyl-CoA, resulting in the subsequent esterification of FFAs

and the generation of complex lipids such as sphingolipids and

ceramides, which accumulate in pancreatic β-cells and trigger cell

death (33).

An increase in FFAs promotes p53 activity. It has

been shown that in pancreatic β-cells (NIT-1 cells), palmitic acid

inhibits cell proliferation by increasing the expression of p53

(34) and activates apoptosis via

the p38 MAPK/p53 and NFκB pathway (35). The apoptosis of β-cells induced by

exposure to FFAs has also been related to the expression of miR-34

(36), which inhibits Akt and Mdm2

activation and p53 degradation (10,37).

Glucolipotoxicity also promotes the inflammatory response in

β-cells, which is manifested by the increased activity of

proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α, which contribute

to the dysfunction and death of β-cells (38). Alterations in the expression of the

transcription factors Mafa and PDX-1 and of the insulin gene have

also been observed after exposure to FFAs and glucose (35,37).

Endoplasmic reticulum stress

Alterations in protein folding and the accumulation

of poorly folded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum generate a

state known as endoplasmic reticulum stress. This response begins

with the activation of protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK),

activating transcription factor-6 and inositol-requiring enzyme-1,

whose activation decreases the translation of proteins and

increases the folding capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum and the

degradation of poorly folded proteins (38). If this process is not successful,

then the apoptosis process begins (38).

Excessive weight gain can lead to a state of insulin

resistance, during which insulin-dependent tissues are unable to

internalize glucose molecules (3).

In these circumstances, the demand for insulin increases, and

β-cells must synthesize and secrete more insulin. This demand also

falls on the endoplasmic reticulum, which must process more insulin

molecules (8). Exposure to

saturated FFAs such as palmitate affects the response capacity of

the endoplasmic reticulum and increases the levels of poorly folded

proteins, resulting in stress in the endoplasmic reticulum

(38). If the demand for

continuous insulin and ER stress are not resolved, then apoptosis

is activated due to the PERK-dependent increase in the

transcription factor CHOP, increased expression of the

pro-apoptotic proteins Puma and DP5, and inhibition of the

anti-apoptotic protein MCL-1 (39). One study has reported that

endoplasmic reticulum stress markers are also increased in patients

with T2D (38). The participation

of p53 in stress-induced apoptosis of the endoplasmic reticulum has

been related to the regulation of the expression of pro-apoptotic

and anti-apoptotic proteins.

Implication of cytokines and inflammation in

pancreatic β-cell dysfunction

Obesity constitutes a chronic low-intensity

inflammatory state that activates the innate immune system, which

in turn can alter glucose tolerance, contribute to the development

of insulin resistance, and progress to diabetes and cardiovascular

disease (40,41). An increase in the plasma

concentration of C-reactive protein in the acute phase predicts the

presence of coronary heart disease, metabolic syndrome and T2D

(40).

In addition, Hotamisligil (41) was one of the first researchers to

establish that adipocytes express TNF-α and that this expression is

related to obesity and resistance to systemic insulin. Other

proinflammatory molecules, such as resistin, IL-6, serum amyloid

A3, acid glycoprotein A1 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1, are

also expressed in adipose tissue and potentially induce themselves

in response to obesity and diabetes. These proinflammatory

molecules contribute to alterations in pancreatic β-cells (42). Diabetes is characterized by the

infiltration of inflammatory cells into the pancreas, which favors

the progressive destruction of β-cells (7). T cells and infiltrated macrophages

produce and secrete inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IFN-γ and

TNF-α, which contribute to the loss of β-cells due to apoptosis

activation (43,44). This process highlights the

participation of the NF-κB nuclear factor, which regulates the

expression of genes involved in the response to stress, growth,

survival and cellular apoptosis (45). Previous studies have shown that IκB

transgenic mice-/- (NF-κB inhibitor protein), which are specific to

β-cells, do not develop streptozotocin-induced diabetes (45).

In adipose tissue, in addition to storing energy,

hormones such as adiponectin, leptin, resistin, and visfatin and

other mediators such as interleukins that regulate lipid and

glucose metabolism are produced, which also affect the function of

β-cells (46). Therefore, there is

a close association between the levels of adipokines secreted by

adipose tissue and the proper functioning of pancreatic β-cells.

The inhibitory effects of leptin on insulin synthesis, either

directly in the pancreas or indirectly mediated by the autonomic

nervous system, have been previously reported (47). Adiponectin is an anti-inflammatory

and anti-apoptotic cytokine. A decrease in adiponectin plasma

levels in obese individuals has been associated with insulin

resistance, metabolic syndrome and T2D (47). Adiponectin exerts its effects

through its interaction with its receptors (adipoR1 and adipoR2).

In addition to having anti-inflammatory properties, it contributes

to the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in the muscle and

liver and increases the use of glucose and the oxidation of fatty

acids (40,47).

Apoptosis and oxidative stress

Increased apoptosis in β-cells plays a precise role

in the initiation and progression of T2D (48). Among the possible mechanisms that

explain the increase in apoptosis in these cells, the production of

ROS of mitochondrial origin stands out (49). In T2D, IR is primarily compensated

for by enhanced insulin secretion by β-cells. However, over time,

this mechanism can fail and lead to a loss of metabolic regulation,

resulting in chronic exposure of β-cells to elevated levels of

glucose (33). Notably, the

increase in intracellular levels of Ca2+ necessary for

the exocytosis of insulin also contributes to the formation of ROS.

Overproduction of free radicals decreases the activity of the

glycolytic enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH),

resulting in increased concentrations of glycolytic metabolites,

such as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate or fructose-6-phosphate

(35–38,48,49).

Finally, GAPDH inhibition increases the levels of metabolites of

the glycolytic pathway. Consequently, the substrate for the polyol

pathway increases, and the enzyme aldose reductase consumes

available NADPH and decreases the antioxidant mechanisms of β-cells

(50). Furthermore, pancreatic

β-cells have a low capacity to respond to oxidative stress as the

expression of antioxidant enzymes is also low (51). In addition, the reaction of ROS

with biomolecules causes an autocatalytic chain reaction with

subsequent cellular damage and activates mechanisms that emphasize

the death of β-cells and decreased cell mass (48).

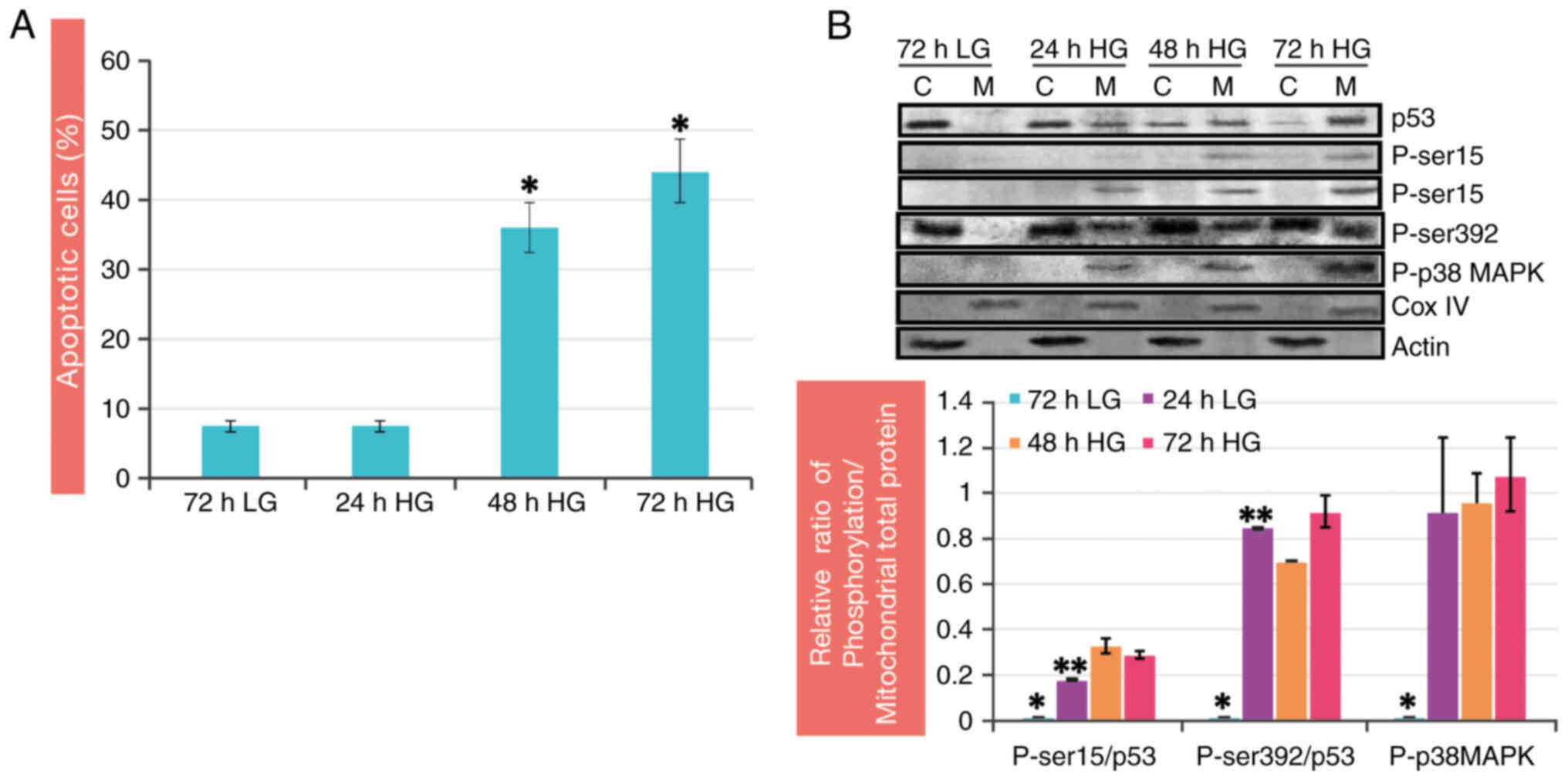

It was previously showed that by culturing RINm5F

pancreatic β-cells in the presence of a high concentration of

glucose (30 mM), the percentage of viable cells significantly

decreased after 48 h compared with that of the control (low

glucose, LG). These findings were consistent with the substantial

increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells (44%) at 72 h

compared with that in the control group (Fig. 4A) (11). Oxidative stress has been identified

as another critical mediator in the cell death process with the

ability to trigger or modulate apoptosis, and it has been found

that the pro-apoptotic role of ROS is manifested through

alterations in mitochondrial function, causing the release of

cytochrome c (32,52).

ROS and oxidative stress in pancreatic β-cells

exposed to high concentrations of glucose are characterized by an

alteration in the potential of the mitochondrial membrane and a

modification of its permeability (17). This alteration allows the release

of pro-apoptotic proteins such as cytochrome c into the cytosol

after 24 h of culture with high glucose. In addition, the

activation of caspase-3 is promoted (11,17).

The balance between pro- (Bax) and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2) proteins,

among others, plays an important role in the permeability of

mitochondrial membranes and the release of other pro-apoptotic

proteins (53,54). In this sense, it was shown that the

Bcl-2/Bax ratio in the mitochondria decreases significantly after

24 h of culture with high glucose, which indicates the cytotoxicity

induced by the high concentration of glucose in β-cells (11,17).

These results are in accordance with previous reports that

hyperglycemia induces apoptosis in β-cells, causing a decrease in

Bcl-2 expression and an increase in Bax expression, aspects

associated with cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation

(18,55). High glucose decreased ERK 1/2

phosphorylation. This observation is related to an increase in

apoptosis and a decrease in the rate of cell proliferation

(18). ERK 1/2 phosphorylation has

been shown to modulate genes related to proliferation,

differentiation, migration and death depending on the duration,

magnitude and cellular location (56). In β-cells, activation of ERK 1/2

favors the synthesis and secretion of insulin in response to

glucose and inhibits apoptosis (57); therefore, its inactivation impacts

cellular functions and the β-cell mass.

During the process of apoptosis, protein

translocation between the nucleus, cytoplasm and mitochondria

occurs, which promotes the regulation of this process of cell death

(17). The p53 protein is part of

this group of proteins and is known to be a regulator of apoptosis

when the cell presents irreparable damage to its structure

(58,59).

Dual role of the p53 protein: The guardian

of the genome and mediator of apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells

The p53 protein is known as the ‘guardian of the

genome’, and its activation leads to a series of crucial biological

consequences, ranging from the regulation of the cell cycle and DNA

recombination to chromosome segregation, cell aging and the

induction of apoptosis (60,61).

In response to different extracellular and intracellular stimuli,

such as DNA damage, p53 is activated, triggering various biological

responses such as cell cycle arrest or cell death. After cell

damage, the levels of p53 in cells rapidly increase. This increase

is mainly attributed to post-translational modifications that alter

the half-life of the protein and to the increase in the translation

of its mRNA, which results in the regulation of its target genes

(60,61).

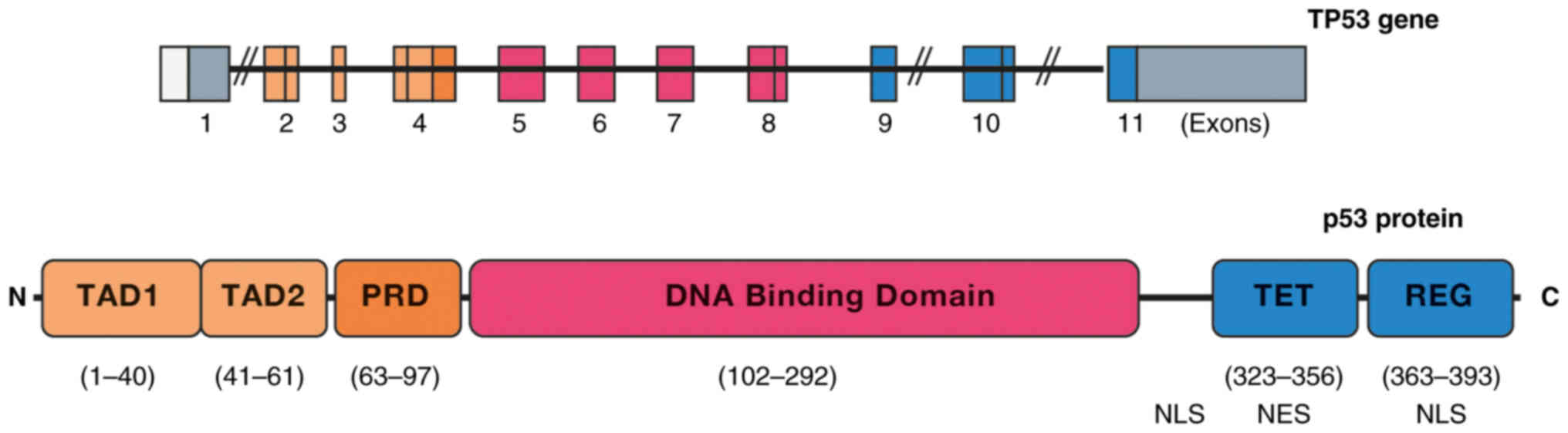

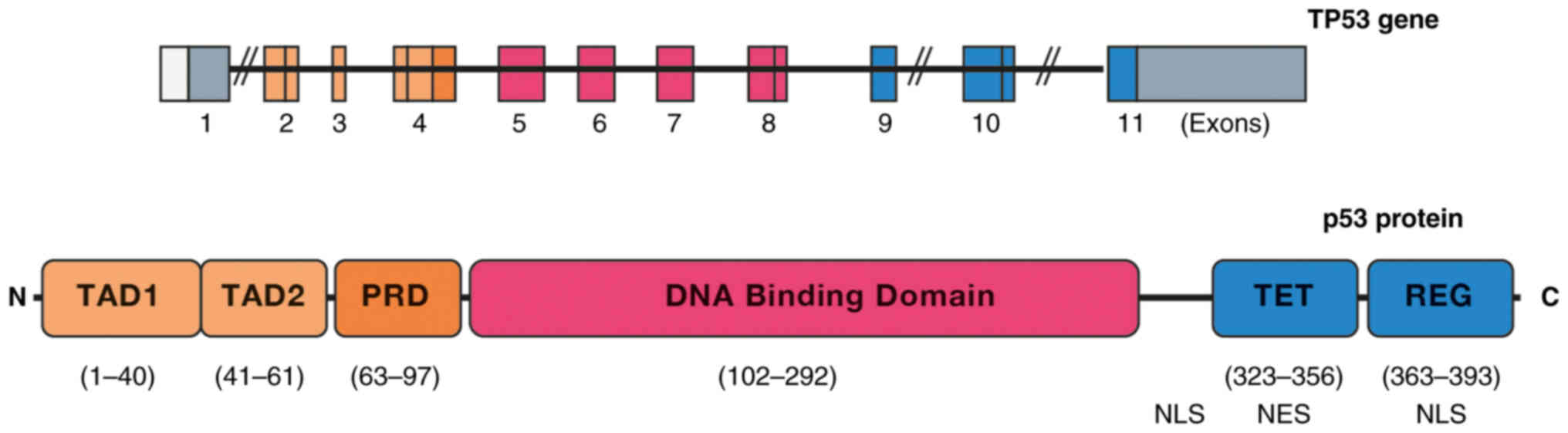

The p53 gene on chromosome 17 (17p13.1) is

composed of 11 exons, of which exon 1 contains a noncoding

sequence. In exon 2, there are two putative transcription start

sites, and exon 11 contains a stop codon and a large noncoding

sequence. The p53 protein has 393 amino acids divided into

functional domains (Fig. 5)

(60). The transactivation domain

(TAD) is located at its N-terminal end and is essential for

interactions with coactivators and transcriptional corepressors

(60,61). TADs are composed of two homologous

subdomains, TAD1 (residues 1–40) and TAD2 (residues 41–61), which

share conserved Φ-XX-Φ-Φ sequence motifs (where Φ represents

hydrophobic amino acids and X represents any amino acid), which are

common to numerous transcriptional regulatory proteins (62). The TAD is a proline-rich region

(PRD; residues 63–97) followed by a highly conserved DNA-binding

domain (DBD; residues 102–292), characterized by specific binding

to DNA sequences (63). Following

the DBD, a binding region harboring an integrated nuclear

localization signal (NLS; residues 301–323) is presented, followed

by the tetramerization domain (TET; residues 323–356), which

includes a nuclear export signal. Finally, there is a mostly

disordered C-terminal regulatory domain (residues 363–393)

(60). This last domain is

characterized by its basic nature; it contains two additional NLSs,

and it is a zone of important protein-protein interactions that

regulate the activity of p53, which binds to DNA in tetrameric form

(60,61). The formation of this quaternary

structure depends on the correct activation of p53 and

post-translational modifications of the TET (63). The C-terminal region is essential

for the formation of tetramers (64).

| Figure 5.Structures of the TP53 gene and p53

protein. A schematic representation of the 11 exons of the TP53

gene is shown, of which one is not encoded. TP53 encodes a protein

of 393 amino acids that has five domains: TAD, PRD, DNA-binding

domain, TET and REG. TAD, transactivation domain; PRD, proline-rich

region; TET, tetramerization domain; REG, regulatory domain; NLS,

nuclear localization signal; NES, leucine-rich nuclear export

signal. |

One of the essential functions of p53 is to monitor

cell stress and prevent the proliferation of damaged cells by

inducing apoptosis (58). As a

nuclear transcription factor, p53 can activate the transcription of

pro-apoptotic genes such as bax and puma (65,66).

Moreover, p53 can repress the expression of anti-apoptotic genes

such as bcl-2 and bcl-XL (30). In

addition, p53 also regulates the expression of death receptors. An

example is the death receptor Fas, which mediates apoptosis through

its interaction with the FasL ligand and, in turn, is under the

regulation of p53 (60).

Another prominent function of p53 is its role in

regulating apoptosis through transcription-independent mechanisms

(67,68). In response to multiple apoptotic

stimuli, a fraction of p53 translocates into mitochondria, where it

establishes physical interactions capable of inhibiting the

anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL (69). Likewise, it contributes to the

activation of the pro-apoptotic Bax and Bak proteins that induce

permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane by acting on

VDAC, allowing the release of apoptotic activators into the

cytoplasm (27,70). During the characterization of p53,

the possibility of its involvement in the regulation of cell

organelle functions was raised, which has been supported by the

observation of the mobilization of p53 toward the outer

mitochondrial membrane during apoptosis in response to stress from

γ radiation (62,71,72).

Exposure to high concentrations of glucose has been

linked to the apoptotic death of β-cells, a phenomenon that has

been associated with the translocation of the p53 protein into

mitochondria (17). The excessive

consumption of carbohydrates induces metabolic alterations,

negatively impacting the cellular functions of β-cells and

triggering their death (9). The

role of p53 in the death of pancreatic β-cells has recently been

analyzed using a model in which Sprague Dawley rats were subjected

to carbohydrate supplementation. For four months, the animals

received drinking water containing either 40% sucrose or 40%

fructose. Carbohydrate ingestion induced both apoptosis and the

mobilization of p53 from the cytosol to the mitochondria of rat

pancreatic β-cells, even before blood glucose levels rose (9). In addition, the ability of p53

knockout mice to regenerate the β-cell population and rescue the

diabetic phenotype has been demonstrated (73,74).

This finding emphasizes the critical importance of this protein in

the progression of diabetes. However, there is at least one report

that contradicts the participation of p53 in β-cell death (75).

The p53 protein is a transcription factor that is

responsible for monitoring DNA damage (60). Depending on the severity of the

damage, p53 induces apoptosis or arrests the cell cycle until DNA

repair mechanisms are activated. Activation of p53 occurs in

response to various types of stress, leading to its stabilization

and accumulation (63). p53 is

also known to be involved in the induction of apoptosis by acting

directly on mitochondria, where it forms complexes with the Bcl-2

and Bcl-XL proteins through its DBD and precedes the release of

cytochrome c and the activation of caspase-3 (76).

The apoptosis of β-cells exposed to high glucose

concentrations has been demonstrated to occur due to the exit of

cyt c into the cytosol and a decrease in the Bcl-2/Bax ratio in

mitochondria (11,17). These events are related to the

mobilization of p53 to mitochondria, increased ROS and decreased

mitochondrial membrane potential (11). Thus, it was concluded that high

glucose conditions regulate the intracellular distribution of p53

and favor its mitochondrial localization (11,17).

In addition, it promotes post-translational modifications of p53

that prevent its degradation and increase its biological activity

(9–11,17,18).

Post-translational modifications can

regulate p53 in β-cells under hyperglycemic conditions

Under physiological conditions, the p53 protein

remains in a latent state, reaching expression levels in some cell

types that are undetectable by immunohistochemical or Western blot

techniques (60). This protein,

with a half-life close to 15 min in some cell types, is found in an

inactive conformation that is diffusely located in the cell,

frequently being cytoplasmic (77). Although the p53 protein is found at

low concentrations in non-stressed cells, it is rapidly stabilized

and activated in response to various stimuli (59). These stimuli, which are associated

with cellular stress, such as direct damage to DNA by UV or

ionizing radiation, redox changes, hypoxia or thermal shock,

increase the levels of the p53 protein in the cell (78). This increase results from both

greater protein stability and biochemical activation through

post-translational modifications.

The functions of p53 are regulated by at least 10

different types of post-translational modifications, the most

frequent being phosphorylation, ubiquitination,

poly-ADP-ribosylation, acetylation, sumoylation, methylation,

glycosylation and O-GlcNAcylation at serine (Ser)149 of p53

(79–82). Various enzymes catalyze these

modifications and contribute to p53 activation through a wide

variety of mechanisms (83,84).

A number of these modifications are related to an increase in their

ability to arrest the cell cycle or induce apoptosis (58,59).

The permanence and functions of p53 in β-cells under hyperglycemic

conditions are controlled by different post-translational

modifications, including phosphorylation, O-GlcNAcylation and

poly-ADP-ribosylation, depending on the intracellular environment

(17,18).

p53 protein can be regulated by phosphorylation in

response to hyperglycemia: Implications for cell stability and

functions. It has been argued that the levels of the p53 protein

are intrinsically linked to the balance between its synthesis and

degradation, and it is evident that any effect on these events will

have different consequences in the cell (59,60).

A previous study has confirmed that high glucose concentrations do

not modify p53 transcription (10).

By contrast, it has been suggested that its

mobilization and increase in mitochondria result from protein

stabilization, which depends on post-translational modifications

such as phosphorylation (11). The

p53 protein contains multiple phosphorylation-prone sites on

(Ser)/threonine (Thr) residues distributed throughout the protein,

with enrichment at the N-terminus (57). Most of these sites can become

phosphorylated under cellular stress conditions, thus regulating

the functions of p53 (60).

Phosphorylation of p53 at the N-terminus, which occurs in the

cytosol, has been related to an increase in the transcription of

the pro-apoptotic protein Bax (85–87).

On the other hand, phosphorylation at the C-terminal end of Ser 392

(or Ser 389 in mice) is related to the formation of p53 tetramers,

DNA binding and the induction of apoptosis, in addition to

contributing to the suppression of tumors (88).

It has been previously reported that p53 is

phosphorylated at Ser15 and Ser392 in the mitochondria of

pancreatic β-cells cultured under high-glucose conditions (11). Phosphorylation at these residues

likely contributes to protein stability and is an essential

requirement for the interaction of p53 with pro- and/or

anti-apoptotic proteins (11). In

studies in which RBL-2H3 cells (mast cells) were treated with

eugenol (anti-allergenic), it was reported that p53 phosphorylation

at the Ser15 residue in mitochondria facilitates the interaction of

p53 with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, which in turn induces changes in the Δψm

and the release of cytochrome c (88). It is relevant to mention that the

observation of p53 phosphorylation at residue Ser 392 in

mitochondria in response to hyperglycemia seems to be the only one

thus far. However, there are at least two studies linking the

phosphorylation of this serine by p38 MAPK kinase with Bax

activation and apoptosis in myocytes cultured with high glucose

(89–91). Notably, p38 MAPK plays an important

role in regulating insulin secretion (92). Since p53 has multiple

phosphorylation sites, multiple kinases, including those activated

by oxidative stress, such as p38 MAPK, regulate this process

(93,94). Under high glucose conditions, the

subcellular redistribution of p38 MAPK (from the cytosol to

mitochondria) is stimulated, but its activation is only observed in

the mitochondrial fraction (Fig.

4B). The localization and phosphorylation of p53 coincide with

the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in mitochondria during high glucose

treatment (11). These findings

were confirmed by colocalization studies of the phosphorylated

proteins by confocal microscopy, where a high colocalization

coefficient was observed for both p53 and p38 MAPK in mitochondria

(11). To verify the participation

of p38 MAPK in p53 phosphorylation, a specific inhibitor of p38

MAPK (SB203580) was added to cultured RINm5F cells exposed to high

glucose. The results demonstrated that the inhibitor prevented p53

phosphorylation at the Ser 392 and Ser 15 residues at all time

points tested. Similarly, a decrease in the release of cytochrome c

and the rate of apoptosis were observed (11). These data corroborate that p38 MAPK

activation under these conditions is responsible for p53

phosphorylation at the Ser 392 and Ser 15 residues in mitochondria.

Previous studies in other cell types have revealed that under

conditions of hyperglycemia, oxidative stress and UV radiation, p38

MAPK regulates apoptosis by phosphorylating p53 at Ser 392

(85,94,95)

and Ser 15 (96). In addition, p38

MAPK inhibition affects p53 mobilization to mitochondria (11). Phosphorylation likely has a

protective effect on p53, preventing its interaction and

recognition by Mdm2, which in turn preserves its stability and

degradation, allowing its mobilization to mitochondria. This would

trigger the activation of apoptosis, as well as its association

with anti-apoptotic proteins (10,11).

The interaction between p53 and Bcl-2 in the

mitochondrial fraction of cells treated with 30 mM glucose was

observed after 24 h. Inhibition of p53 phosphorylation at Ser392

and Ser15 by a p38 MAPK inhibitor affected the association of p53

with Bcl-2. These results indicate that this phosphorylation is

very important for promoting the association of p53 with Bcl-2 and

for p53 to remain in the mitochondria (11).

Furthermore, p53 phosphorylation was detected at

Ser15 in the nuclear fraction. Previous studies have confirmed that

this phosphorylation at Ser15 caused by UV radiation or hydrogen

peroxide is due to ataxia telangiectasia mutated kinase (ATM)

activation. It should be noted that phosphorylation of this residue

when the protein is in the cell nucleus helps to stabilize and

activate the transcriptional functions of p53, which are related to

the regulation of apoptosis (97).

The results of the present study showed an increase in ATM

phosphorylation in the cytosol and nucleus in response to high

glucose exposure, probably because of the oxidative stress that

prevails under these conditions (17,98).

In this context, ATM-deficient mice exhibit oxidative stress and

damage to DNA, proteins and lipids via ROS (98). In addition, the administration of

antioxidants such as N-acetyl cysteine has been shown to be

effective in reducing oxidative damage, reversing neurological

deficits and preventing premature aging in these animal models

(99). ATM plays a crucial role by

phosphorylating numerous substrates needed for DNA repair, cell

cycle regulation and apoptosis, including the p53 protein (97). In addition, p53 phosphorylation at

Ser15 in the nuclear fraction appears to be related to ATM

activation (98). Furthermore,

streptozotocin-induced p53 activation by ATM is a critical event in

DNA damage in β-cells in vitro (100). However, ATM activation is likely

also associated with the phosphorylation of other proteins and

indirectly regulates p53. ATM can phosphorylate p53 through Chk2

activation (101,102) or phosphorylate Mdm2 at Ser395,

thus preventing p53 ubiquitination and degradation; thus, ATM could

be an adjacent mechanism for p53 stabilization (84,101). Additionally, the relevance of ATM

activation in glucose metabolism has been noted, although the

precise underlying mechanisms have not yet been determined. ATM

inhibition affects the incorporation of glucose into muscle and

adipose tissue through the mobilization of GLUT4, which is why it

has been linked to the development of insulin resistance and T2D

(100).

O-GlcNAcylation. O-GlcNAcylation is a regulatory

mechanism of p53 stability and function in response to glucose. It

is a noncanonical glycosylation process involving the attachment of

single O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) moieties to Ser and

Thr residues of cytoplasmic, nuclear and mitochondrial proteins

(102,103). O-GlcNAcylation is another

post-translational modification of p53 and depends on glucose

availability. In this mechanism, two enzymes participate: OGT

(O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase), which adds

N-acetylglucosamine residues to several proteins at the hydroxyl

group of Ser and Thr, and O-GlcNAcase (N-acetylglucosaminidase),

which eliminates the N-acetylglucosamine residues from the proteins

(104). Physiologically,

disruption of O-GlcNAc homeostasis has been implicated in the

pathogenesis of a plethora of human diseases, including cancer,

diabetes and neurodegeneration (105). O-GlcNAcylation has been linked to

T2D since the expression of OGT RNA in the pancreas and brain is

increased (2 Studies have reported that the protein level of p53 is

elevated in the liver of patients with T2DM, partly because hepatic

p53 is stabilized by O-GlcNAcylation and plays an essential role in

the physiological regulation of glucose homeostasis (79,80).

O-GlcNAcylation has been shown to stabilize p53 and prevent its

degradation (81).

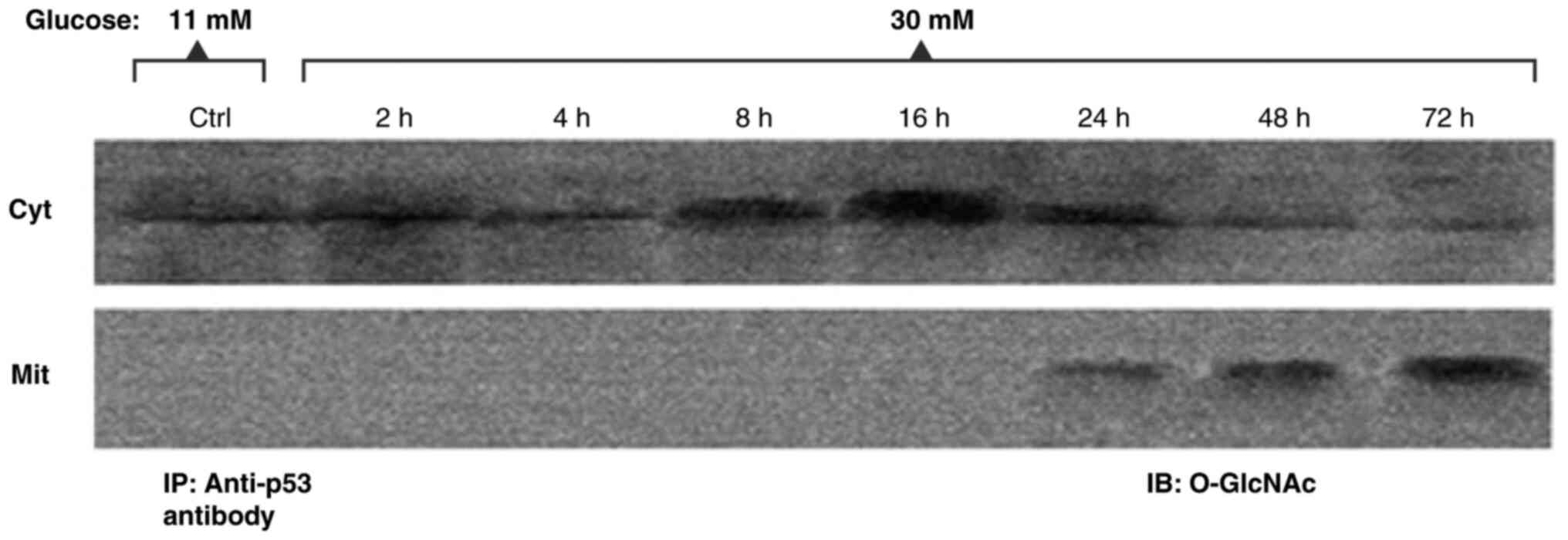

In a high-glucose environment, p53 O-GlcNAcylation

is related to its stability and stops its degradation.

O-GlcNAcylation does not interfere with phosphorylation, but it

stimulates p53 apoptotic function (105–107). In the studies presented in the

present review, it was observed that O-GlcNAcylation precedes

apoptosis and increases as apoptosis signals appear in RINm5F cells

under hyperglycemic conditions (Fig.

6). In addition, the O-GlcNAcylation of p53 promotes its

mobilization to mitochondria, which can contribute to the release

of pro-apoptotic factors (18).

O-GlcNAcylation of p53 at Ser149 increases its stability upon

interference with Thr155 phosphorylation and weakens the

interaction of p53 with Mdm2, along with the ubiquitination and

thus proteolysis of p53, which translates into greater stability of

p53. Thus, it is hypothesized that O-GlcNAcylation stabilizes p53

and may create a signal for its mobilization to the

mitochondria.

Interaction between PARP and p53: Modulation of DNA

repair and apoptosis in response to cell damage and high glucose

conditions. When DNA damage occurs in cells, poly (ADP-ribose)

polymerase (PARP), a nuclear protein of 116 kDa with two zinc

finger motifs that bind to DNA and specifically detect nicks or

breaks, is activated (108,109). PARP catalyzes the transfer of

ADP-ribose units from NAD+, an essential cofactor in ATP

synthesis and redox potential balance, to glutamic acid and

aspartic acid residues of several nuclear proteins (108). This post-translational

modification is important for the activation of a series of

cellular processes, including DNA repair and replication, gene

transcription, the inflammatory response and cell death, and occurs

mainly in response to DNA damage generated by genotoxic agents, as

well as different stimuli to DNA damage, such as infection and

stress (109–111). In vivo immunoprecipitation

of PARP and p53 has shown that both proteins interact, and that

this PARP-p53 interaction may affect the function of the p53

protein, as it is ADP-ribosylated by PARP in response to DNA damage

or cellular aging (112).

The amino-terminal region of the PARP protein

contains a target sequence of caspases 3 and 7 that is responsible

for PARP proteolysis into two fragments of 89 and 24 kDa. This

proteolytic breakdown is currently considered a marker of

caspase-dependent apoptosis (112). Fragments generated by the action

of caspases 3 and 7 contribute to the inactivation of the intact

enzyme (113). PARP fragmentation

coincides with the induction of apoptosis in β-cells by

hyperglycemia (10). These results

agree with previous reports showing that hyperglycemia induces the

apoptosis of β-cells and pancreatic cell lines, such as RINm5F

(11,17). Short-term treatment of RINm5F cells

with high glucose (2–16 h) induces an increase in PARP protein

(18). Immunoprecipitation assays

revealed an association between PARP and p53, as well as

poly-ADP-ribosylation of p53 in the nuclear fraction, which

promotes the function of p53 in DNA repair mechanisms in the early

stages of cell damage (10,18).

Poly-ADP-ribosylation of p53 under high-glucose conditions also

likely contributes to its stability and mobilization in

mitochondria (18). After 24 h,

PARP degrades and becomes inactivated, which leads to a decrease in

poly-ADP-ribosylation of p53. PARP fragmentation and inactivation

coincided with increased Bax in mitochondria, cytochrome c release,

and increased apoptosis of RINm5F cells due to high glucose

conditions (18).

Dual regulation of p53: Interaction between

Mdm2 and ubiquitination activity in the context of hyperglycemia

and cellular stress

Cell survival largely depends on the p53

concentration. Mdm2 is one of the regulatory mechanisms of p53.

Mdm2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that binds to p53 and adds ubiquitin

residues to it for proteasomal degradation. However, the fate of

p53 depends on Mdm2 activation and the addition of ubiquitins,

after which mono- or polyubiquitylation is regulated by Mdm2

(114). As previously cited, the

formation of the p53-Mdm2 complex is determined by the

post-translational modifications of both proteins. The

ubiquitylation, SUMOylation and phosphorylation of Mdm2 disrupts

the formation of the p53-Mdm2 dimer and stabilizes p53.

Phosphorylation of Mdm2 at Ser395 by ATM activation has been shown

to decrease the ability of Mdm2 to drive p53 degradation.

Furthermore, it was previously reported that Mdm2

phosphorylation by Akt is involved in the regulation of p53, as it

reduces transactivation and increases p53 ubiquitination (115,116). Akt is a critical regulator of

cell proliferation and survival (115). Phosphorylation of Mdm2 at Ser166

and Ser186 by Akt increases its E3 ligase activity, and can protect

cells against p53-induced apoptosis caused by hyperglycemia

(10). Notably, other kinases,

such as ERK 1/2, can phosphorylate Mdm2 at Ser166. However, with

increased glucose, ERK 1/2 decreases and apoptosis increases

(11).

Increased glucose decreases Mdm2 mRNA and protein

levels in the nucleus and cytosol, Mdm2 expression is regulated by

p53 (10). Previous studies have

shown that in cells cultured with high concentrations of glucose,

p53 is not found entirely in the nucleus but is mobilized to other

organelles, such as mitochondria (11,17).

Therefore, it cannot stimulate the expression of Mdm2. Furthermore,

DNA fragmentation due to hyperglycemia can also affect Mdm2 mRNA

expression (10).

The E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of Mdm2 is

situated within the RING-finger domain in the carboxyl-terminal

region, where the lysine acceptor is also found, whose main

function is to mark p53 for degradation (117). The central Mdm2 acidic domain

binds to the RING-finger domain and stimulates its catalytic

activation and ubiquitin release by the E2 enzyme (117). The interaction between the acidic

domain and the RING-finger domain is modulated by phosphorylated

ATM (10). In this model, an

increase in ATM phosphorylation due to hyperglycemia was also

observed, so it cannot be ruled out that stress and the

phosphorylation cascade induced by high glucose may phosphorylate

some residues present in or near the RING-finger domain and the

acidic core domain of Mdm2 and suppress p53 polyubiquitination and

degradation.

By contrast, ubiquitination of p53 depends on the

energy supply. Hyperglycemia increases ROS and mitochondrial

uncoupling, leading to decreased ATP levels. Therefore, if ATP

decreases, ubiquitins cannot condense the glycine residues of their

carboxyl-terminal region with the lysine residues of p53, and p53

degradation is inhibited (114,115).

Conclusions

The mechanisms involved in pancreatic β-cell loss

due to hyperglycemia are not yet fully known. Hyperglycemia is

characterized by exacerbated ROS production, which stimulates the

activation of phosphorylation cascades that may suppress Mdm2 E3

ubiquitin ligase activity and inhibit the p53-Mdm2 complex. Thus,

it prevents p53 degradation and promotes p53 recruitment to

mitochondria and β-cell death. Other changes initiated by

hyperglycemia, such as poly-(ADP-ribosylation) and O-GlcNAcylation,

also influence p53 stabilization and activation (Fig. 7). The studies described in the

present review aimed to elucidate the biochemical events related to

the loss of β-cells in patients with T2D. These findings offer a

reference point for the search for new therapeutic targets,

possibly for post-translational modifications of p53.

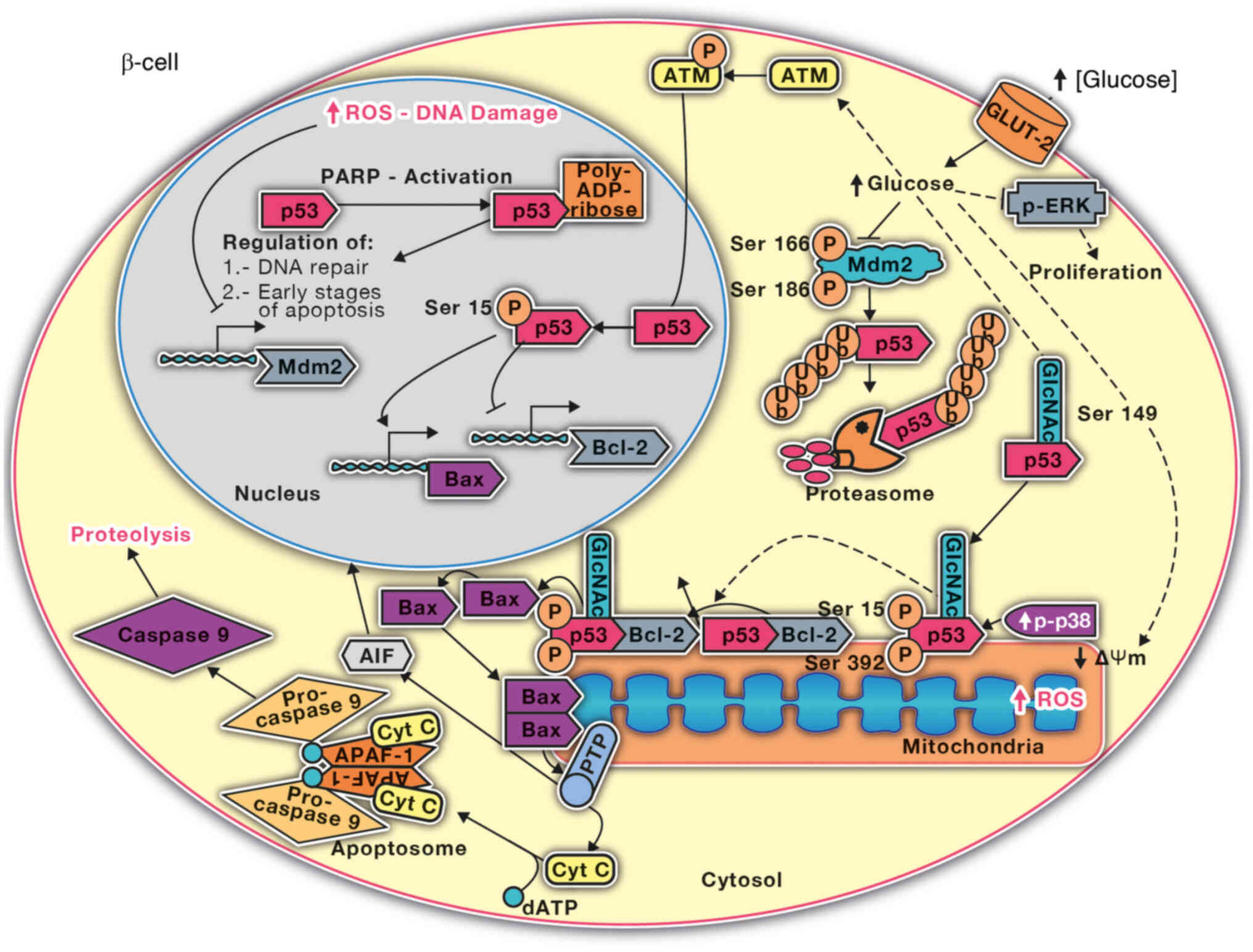

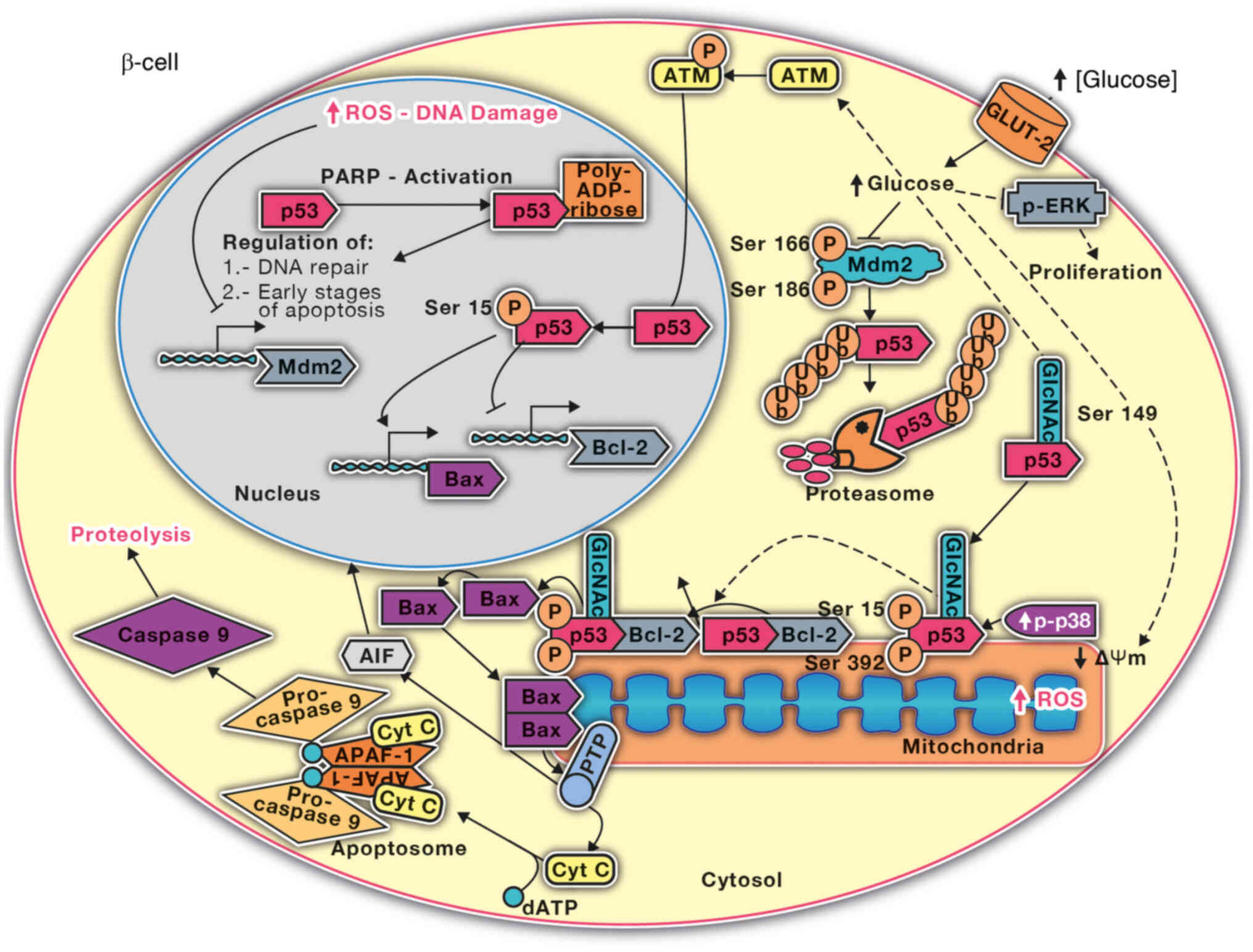

| Figure 7.Regulation of p53 due to high glucose

in pancreatic β-cells. Poly-ADP-ribosylation occurs in the early

stages of RINm5F cell culture with high glucose, which allows p53

to regulate DNA damage repair and the early stages of apoptosis.

p53 O-GlcNAcylation is increased in the cytosol and stabilizes p53,

enabling its migration to the mitochondria, where it is

phosphorylated via p38 MAPK. The phosphorylation of p53 likely

promotes its interaction with anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2) and

the release of pro-apoptotic elements such as cytochrome c. These

events lead to the activation of caspases. High glucose conditions

also inhibit the phosphorylation and activation of Mdm2 and the

ubiquitination of p53, as well as its degradation by the

proteasome. ROS, reactive oxygen species; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose)

polymerase; Mdm2, murine protein double minute 2; ATM, ataxia

telangiectasia mutated kinase; p, phosphorylated; GlcNAc

N-Acetylglucosamine, dATP, deoxyadenosine triphosphate; Δψm,

transmembrane potential; cyt c, cytochrome c; Ub, ubiquitin; AIF,

apoptosis-inducing factor; APAF-1, apoptotic protease activating

factor 1; PTP, permeability transition pore. |

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fiscal Resources Program for

Research of the National Institute of Pediatrics (grant nos.

2022/067, 2019/072 and 2020/016), and Border Science 2023, National

Council of Humanities, Sciences and Technologies (grant nos.

CF-2023-I-811 and CF-2023-I-2755).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

LAFL, AAR and COC conceptualized the study; LAFL,

COC, AAR, ACR, IDlMDlM and SEF performed the investigation; LAFL,

COC, IDlMDlM, SEF, IGT, RVR, AAR and GLV wrote, reviewed and edited

the manuscript; LAFL visualized the study; LAFL and COC performed

study supervision and analyzed the information. Data authentication

is not appliable. All the authors read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Marchetti P, Bugliani M, De Tata V,

Suleiman M and Marselli L: Pancreatic beta cell identity in humans

and the role of type 2 diabetes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 5:552017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang P, Fiaschi-Taesch NM, Vasavada RC,

Scott DK, García-Ocaña A and Stewart AF: Diabetes mellitus-advances

and challenges in human β-cell proliferation. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

11:201–212. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Abdul-Ghani MA, Tripathy D and DeFronzo

RA: Contributions of beta-cell dysfunction and insulin resistance

to the pathogenesis of impaired glucose tolerance and impaired

fasting glucose. Diabetes Care. 29:1130–1139. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M,

Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, et

al: IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes

prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes

Res Clin Pract. 183:1091192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Lin X, Xu Y, Pan X, Xu J, Ding Y, Sun X,

Song X, Ren Y and Shan PF: Global, regional, and national burden

and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis

from 1990 to 2025. Sci Rep. 10:147902020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

International Diabetes Federation, .

Diabetes Atlas. (10th Edition). https://fmdiabetes.org/atlas-idf-10o-edicion-2021/September

13–2023

|

|

7

|

Harreiter J and Roden M: Diabetes

mellitus: Definition, classification, diagnosis, screening and

prevention (update 2023). Wien Klin Wochenschr. 135 (Suppl

1):S7–S17. 2023.(In German). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rojas J, Bermudez V, Palmar J, Martínez

MS, Olivar LC, Nava M, Tomey D, Rojas M, Salazar J, Garicano C and

Velasco M: Pancreatic beta cell death: Novel potential mechanisms

in diabetes therapy. J Diabetes Res. 2018:96018012018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Barzalobre-Geronimo R, Contreras-Ramos A,

Cervantes-Cruz AI, Cruz M, Suárez-Sánchez F, Goméz-Zamudio J,

Diaz-Rosas G, Ávalos-Rodríguez A, Díaz-Flores M and

Ortega-Camarillo C: Pancreatic β-cell apoptosis in normoglycemic

rats is due to mitochondrial translocation of p53-induced by the

consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. Cell Biochem Biophys.

81:503–514. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Barzalobre-Gerónimo R, Flores-López LA,

Baiza-Gutman LA, Cruz M, García-Macedo R, Ávalos-Rodríguez A,

Contreras-Ramos A, Díaz-Flores M and Ortega-Camarillo C: Erratum

to: Hyperglycemia promotes p53-Mdm2 interaction but reduces p53

ubiquitination in RINm5F cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 406:3012015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Flores-López LA, Díaz-Flores M,

García-Macedo R, Ávalos-Rodríguez A, Vergara-Onofre M, Cruz M,

Contreras-Ramos A, Konigsberg M and Ortega-Camarillo C: High

glucose induces mitochondrial p53 phosphorylation by p38 MAPK in

pancreatic RINm5F cells. Mol Biol Rep. 40:4947–4958. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel

R, Rizza RA and Butler PC: Beta-cell deficit and increased

beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes.

52:102–110. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

McFarland KF, Catalano EW, Day JF, Thorpe

SR and Baynes JW: Nonenzymatic glucosylation of serum proteins in

diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 28:1011–1014. 1979. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tomita T: Apoptosis in pancreatic β-islet

cells in type 2 diabetes. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 16:162–179. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chandra J, Zhivotovsky B, Zaitsev S,

Juntti-Berggren L, Berggren PO and Orrenius S: Role of apoptosis in

pancreatic beta-cell death in diabetes. Diabetes. 50 (Suppl

1):S44–S47. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Gottlieb TM and Oren M: p53 and apoptosis.

Semin Cancer Biol. 8:359–368. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ortega-Camarillo C, Guzmán-Grenfell AM,

García-Macedo R, Rosales-Torres AM, Avalos-Rodríguez A, Durán-Reyes

G, Medina-Navarro R, Cruz M, Díaz-Flores M and Kumate J:

Hyperglycemia induces apoptosis and p53 mobilization to

mitochondria in RINm5F cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 281:163–171. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Flores-López LA, Cruz-López M,

García-Macedo R, Gómez-Olivares JL, Díaz-Flores M,

Konigsberg-Fainstein M and Ortega-Camarillo C: Phosphorylation,

O-N-acetylglucosaminylation and poly-ADP-ribosylation of P53 in

RINm5F cells cultured in high glucose. Free Radic Biol Med. 53

(Suppl 2):S952012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

DeLong MJ: Apoptosis: A modulator of

cellular homeostasis and disease states. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

842:82–90. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nicholson DW and Thornberry NA: Caspases:

Killer proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 22:299–306. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Peter ME and Krammer PH: Mechanisms of

CD95 (APO-1/Fas)-mediated apoptosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 10:545–551.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ichim G and Tait SWG: A fate worse than

death: Apoptosis as an oncogenic process. Nat Rev Cancer.

16:539–548. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Elmore S: Apoptosis: A review of

programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 35:495–516. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Johnson N, Khan A, Virji S, Ward JM and

Crompton M: Import and processing of heart mitochondrial

cyclophilin D. Eur J Biochem. 263:353–359. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Crompton M: Mitochondrial intermembrane

junctional complexes and their role in cell death. J Physiol.

529:11–21. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Andreeva L, Heads R and Green CJ:

Cyclophilins and their possible role in the stress response. Int J

Exp Pathol. 80:305–315. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Marchenko ND, Zaika A and Moll UM: Death

signal-induced localization of p53 protein to mitochondria. A

potential role in apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem.

275:16202–16212. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lemasters JJ, Qian T, He L, Kim JS, Elmore

SP, Cascio WE and Brenner DA: Role of mitochondrial inner membrane

permeabilization in necrotic cell death, apoptosis, and autophagy.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 4:769–781. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I,

Snow BE, Brothers GM, Mangion J, Jacotot E, Costantini P, Loeffler

M, et al: Molecular characterization of mitochondrial

apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 397:441–446. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Singh R, Letai A and Sarosiek K:

Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: The balancing act of

BCL-2 family proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:175–193. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tsujimoto Y and Shimizu S: VDAC regulation

by the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Cell Death Differ. 7:1174–1181.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Garrido C, Galluzzi L, Brunet M, Puig PE,

Didelot C and Kroemer G: Mechanisms of cytochrome c release from

mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 13:1423–1433. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Roche E: Diabetes tipo 2:

Gluco-lipo-toxicidad y disfunción de la célula β pancreática. Ars

Pharm. 44:313–332. 2003.

|

|

34

|

Chen SS, Jiang T, Wang Y, Gu LZ, Wu HW,

Tan L and Guo J: Activation of double-stranded RNA-dependent

protein kinase inhibits proliferation of pancreatic β-cells.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 443:814–820. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Yuan H, Zhang X, Huang X, Lu Y, Tang W,

Man Y, Wang S, Xi J and Li J: NADPH oxidase 2-derived reactive

oxygen species mediate FFAs-induced dysfunction and apoptosis of

β-cells via JNK, p38 MAPK and p53 pathways. PLoS One. 5:e157262010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lu H, Hao L, Li S, Lin S, Lv L, Chen Y,

Cui H, Zi T, Chu X, Na L and Sun C: Elevated circulating stearic

acid leads to a major lipotoxic effect on mouse pancreatic beta

cells in hyperlipidaemia via a miR-34a-5p-mediated

PERK/p53-dependent pathway. Diabetologia. 59:1247–1257. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mayo LD and Donner DB: A

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes translocation of

Mdm2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

98:11598–11603. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Lytrivi M, Castell AL, Poitout V and Cnop

M: Recent insights into mechanisms of β-Cell Lipo- and

glucolipotoxicity in type 2 diabetes. J Mol Biol. 432:1514–1534.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Cunha DA, Igoillo-Esteve M, Gurzov EN,

Germano CM, Naamane N, Marhfour I, Fukaya M, Vanderwinden JM,

Gysemans C, Mathieu C, et al: Death protein 5 and p53-upregulated

modulator of apoptosis mediate the endoplasmic reticulum

stress-mitochondrial dialog triggering lipotoxic rodent and human

β-cell apoptosis. Diabetes. 61:2763–2775. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Saltevo J, Vanhala M, Kautiainen H,

Kumpusalo E and Laakso M: Association of C-reactive protein,

interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and adiponectin with the

metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2007:935732007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hotamisligil GS: Inflammation and

metabolic disorders. Nature. 444:860–867. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Tilg H and Moschen AR: Inflammatory

mechanisms in the regulation of insulin resistance. Mol Med.

14:222–231. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhao YF and Chen C: Regulation of

pancreatic beta-cell function by adipocytes. Sheng Li Xue Bao.

59:247–252. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Donath MY, Schumann DM, Faulenbach M,

Ellingsgaard H, Perren A and Ehses JA: Islet inflammation in type 2

diabetes: From metabolic stress to therapy. Diabetes Care. 31

(Suppl 2):S161–S164. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Eldor R, Yeffet A, Baum K, Doviner V, Amar

D, Ben-Neriah Y, Christofori G, Peled A, Carel JC, Boitard C, et

al: Conditional and specific NF-kappaB blockade protects pancreatic

beta cells from diabetogenic agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:5072–5077. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Nolan CJ, Madiraju MSR,

Delghingaro-Augusto V, Peyot ML and Prentki M: Fatty acid signaling

in the beta-cell and insulin secretion. Diabetes. 55 (Suppl

2):S16–S23. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K,

Ueki K and Tobe K: Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin

resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest.

116:1784–1792. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bensellam M, Laybutt DR and Jonas JC: The

molecular mechanisms of pancreatic β-cell glucotoxicity: Recent

findings and future research directions. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

364:1–27. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Brownlee M: The pathobiology of diabetic

complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 54:1615–1625. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Du X, Matsumura T, Edelstein D, Rossetti

L, Zsengellér Z, Szabó C and Brownlee M: Inhibition of GAPDH

activity by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activates three major

pathways of hyperglycemic damage in endothelial cells. J Clin

Invest. 112:1049–1057. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Grankvist K, Marklund SL and Täljedal IB:

CuZn-superoxide dismutase, Mn-superoxide dismutase, catalase and

glutathione peroxidase in pancreatic islets and other tissues in

the mouse. Biochem J. 199:393–398. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gottlieb RA: Mitochondria: Execution

central. FEBS Lett. 482:6–12. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Schellenberg B, Wang P, Keeble JA,

Rodriguez-Enriquez R, Walker S, Owens TW, Foster F, Tanianis-Hughes

J, Brennan K, Streuli CH and Gilmore AP: Bax exists in a dynamic

equilibrium between the cytosol and mitochondria to control

apoptotic priming. Mol Cell. 49:959–971. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Adams JM and Cory S: The Bcl-2 protein

family: Arbiters of cell survival. Science. 281:1322–1326. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Huang Q, Bu S, Yu Y, Guo Z, Ghatnekar G,

Bu M, Yang L, Lu B, Feng Z, Liu S and Wang F: Diazoxide prevents

diabetes through inhibiting pancreatic beta-cells from apoptosis

via Bcl-2/Bax rate and p38-beta mitogen-activated protein kinase.

Endocrinology. 148:81–91. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Lawrence M, Shao C, Duan L, McGlynn K and

Cobb MH: The protein kinases ERK1/2 and their roles in pancreatic

beta cells. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 192:11–17. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ito K, Nakazato T, Yamato K, Miyakawa Y,

Yamada T, Hozumi N, Segawa K, Ikeda Y and Kizaki M: Induction of

apoptosis in leukemic cells by homovanillic acid derivative,

capsaicin, through oxidative stress: Implication of phosphorylation

of p53 at Ser-15 residue by reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res.

64:1071–1078. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Shen Y and White E: p53-dependent

apoptosis pathways. Adv Cancer Res. 82:55–84. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Green DR and Kroemer G: Cytoplasmic

functions of the tumor suppressor p53. Nature. 458:1127–1130. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Riley T, Sontag E, Chen P and Levine A:

Transcriptional control of human p53-regulated genes. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 9:402–412. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Jenkins LM, Durell SR, Mazur SJ and

Appella E: p53 N-terminal phosphorylation: A defining layer of

complex regulation. Carcinogenesis. 33:1441–1449. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

el-Deiry WS, Kern SE, Pietenpol JA,

Kinzler KW and Vogelstein B: Definition of a consensus binding site

for p53. Nat Genet. 1:45–49. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ahn J and Prives C: The C-terminus of p53:

The more you learn the less you know. Nat Struct Biol. 8:730–732.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Aubrey BJ, Kelly GL, Janic A, Herold MJ

and Strasser A: How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this

relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ.

25:104–113. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, Kim CN, Ibrado

AM, Cai J, Peng TI, Jones DP and Wang X: Prevention of apoptosis by

Bcl-2: Release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science.

275:1129–1132. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Müller M, Wilder S, Bannasch D, Israeli D,