Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has

reached alarming proportions, affecting ~40% of the world

population (1,2). NAFLD is currently the main cause of

cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver transplantation

in the western world (3,4). Therefore, understanding the

pathogenesis of NAFLD is crucial to establish an improved

prevention and management of the disease.

An excess of fat accumulation in the liver

characterizes NAFLD. The disease progresses through different

stages, beginning with simple steatosis, with the accumulation of

lipid droplets within hepatocytes. This may evolve to non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis (NASH), a more severe stage marked by inflammation,

that might lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis (3,4).

Between 2–5% of the cases with steatosis may develop NASH, fibrosis

and chronic liver disease (2,4). The

mechanisms behind the progression from simple steatosis to NASH

remain unclear.

The risk factors for NAFLD and NASH include obesity,

insulin resistance, diabetes and dyslipidemia, among others. The

excess of lipid accumulation and dysregulation of lipid metabolism

may unfold lipotoxic pathways (5).

In this context, the formation of lipid droplets may serve as a

protective mechanism by sequestering lipids and preventing

lipotoxicity (6–8). Triacylglycerides (TAG) and

cholesterol esters (CE) form the neutral core of lipid droplets.

Conversely, charged intermediaries such as free fatty acids (FFA),

diacylglycerols (DAG) and free cholesterol (Chol) are not able to

enter the neutral core of lipid droplets. Thus, to be included into

the droplets they must first be incorporated into TAG and CE

(9–11). The inclusion of these lipid

intermediaries in lipid droplets avoids its toxic effects such as

inflammation and disruption of membrane dynamics. For instance, FFA

can activate the Toll-like 4 (TLR4) receptors (12) and DAG can promote the activity of

protein kinase C (PKC) (13). In

the same manner, high levels of Chol may alter the fluidity of cell

membranes (14,15), promoting endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

stress and inflammation (16,17).

Therefore, the esterification of Chol to form CE is also essential

to avoid lipotoxicity (18).

The analysis of sex differences is crucial for

understanding NAFLD and NASH. Whereas the prevalence of NAFLD is

markedly higher in men than in women, the disease becomes more

frequent in women following menopause. This is probably due to the

higher prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndrome (MS) at this

stage of life (19–21). Although the mechanisms of this sex

difference remain unknown, the lack of estrogen may play an

essential role in the increased incidence of NASH and NAFLD after

menopause (22).

The present study aimed to evaluate the role of

menopause in the pathogenesis of liver damage in the context of

obesity and insulin resistance. Therefore, the present study used a

well-established murine model of obesity, including males and

females, where a subgroup was ovariectomized to mimic

menopause.

Materials and methods

Animal model

The present study utilized a phenotypic mouse model

of obesity and insulin resistance, described in our previous

publication (21). A total of 79

C57BL/6J mice (57 females and 22 males; age, ~6 weeks; weight,

16–20 g), were acquired from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. These

mice were then randomized to receive either a standard diet (SD) or

a high fat diet (HFD) for six months. For males, 10 animals were

assigned to the SD group and 12 to the HFD group. For females, 25

animals were assigned to the SD group (8 of which were

ovariectomized: SD-OVX) and 32 to the HFD group (12 of which were

ovariectomized: HFD-OVX). Animals were housed in cages at a

constant temperature of 22°C under a 12-h light/dark cycle and 50%

relative humidity in the animal facility at the University of La

Laguna (Tenerife, Spain). Ovariectomies were performed at 2 months

of age, after diet-randomization. During the follow-up period,

animals underwent intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test and

insulin tolerance test during the follow-up period (21). The sample size was determined based

on previous studies (21,23) using similar models. To effectively

implement the 3Rs principles without compromising statistical

power, 8–12 mice were initially included per group to mitigate

potential losses during follow-up. Since female mice underwent a

surgical procedure, more female mice were included at baseline than

male to prevent a reduction in number due to surgical or

post-surgical complications. All animals were euthanized by an

overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) and death was

confirmed by cervical dislocation method. Animal care was performed

in accordance with institutional guidelines in compliance with

Spanish (Real Decreto 53/2013, February 1. BOE, February 8, 2013,

n: 34, p. 11370–11421) and international laws and policies

(Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council

of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for

scientific purposes). All procedures were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Comité de Ética de la

Investigación y de Bienestar Animal) of University of La Laguna

(approval number CEIBA2021-3107).

Diet composition

The HFD provides 60% of the calories from fat (cat.

no. D12492; Research Diets Inc.). This HFD diet had 6-times more

total lipid content than the SD. Furthermore, the fatty acid (FA)

content was 7-fold higher in the HFD compared with SD (Table SI). The details of the diets have

been described in a previous article (23).

Liver histology

Slides from liver tissue in paraffin were stained

with hematoxylin-eosin and Sirius Red to evaluate steatosis,

ballooning, inflammation and fibrosis. A pathologist specialized in

liver diseases (SGH) evaluated all samples following the ‘SAF

index’ published by Bedossa in 2012 (24).

Steatosis

The percentage of hepatocytes with lipid vacuoles

was classified as S0 (minimal or non-existent): <5%; S1 (mild):

5–33%; S2 (moderate): 34–65%; and S3 (intense): >65%.

Lobular necroinflammatory activity and

ballooning

Lobular inflammation was classified in 3 grades: I0,

minimal lobular necroinflammation; I1, two lobular inflammatory

foci in one field; I2, globular activity with multiple clusters in

one field. Lobular inflammation was detected under a light

microscope (magnification, ×200; 20× objective). The pathologist

examined a fraction of the liver and chose a field representing the

sample. Hepatocyte ballooning was classified in 3 grades; B0: no

ballooning, B1 when the hepatocytes had rounded edges while

maintaining their size and B2 when the size of the cell is twice

the size of a normal hepatocyte.

Liver fibrosis

Fibrosis in liver tissue was determined using

Picrosirius Red staining. Liver sections (3 µm) were deparaffinized

in xylene and rehydrated through a graded series of alcohol

concentrations (100, 90 and 70%). The sections were covered in

Picrosirius Red solution and incubated at room temperature for 60

min. Following incubation, the slides were washed with 0.5% acetic

acid solution and 100% ethanol. Finally, tissues were dehydrated

and mounted. The slides were observed, and images were captured

under a digital light microscope (magnification, ×400; 40×

objective). The area of positively red-stained collagen was

quantified using ImageJ version 1.52k software (National Institutes

of Health).

Serum analysis

Serum TAG and Chol were measured using an enzymatic

colorimetric test. Hepatic aspartate (AST; cat. no. ACN 8687; Roche

Diagnostics) and alanine aminotransferase (AST; cat. no. ACN 8685;

Roche Diagnostics) transaminases were measured by

spectrophotometric analysis. All analyzes were performed in a Cobas

c711 Module (Roche Diagnostics).

Inflammation markers in liver

tissue

SDS-PAGE and western blotting of liver proteins were

performed as follows: Liver homogenates were prepared with RIPA

buffer and disaggregated using the System Polytron PT 1200 E

(Kinematica AG), followed by sonication for 3 min at 80% amplitude

with a cycle of 15 sec on/off at a frequency of 20 kHz and 4°C

using a Qsonica Q800R3 sonicator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Homogenates were then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

Supernatants were collected and protein concentration was

determined by using a BCA protein assay kit (MilliporeSigma). Gels

(10–12% acrylamide) were loaded with 50 µg of total protein per

sample, then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes

(Whatman-Protran; Merck KGaA). Membranes were blocked with 5%

non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight

with the respective primary antibody at 4°C. The primary antibodies

and dilutions used were TNF-α (1:1,000; BS2081R; BIOSS), IL-1β

(1:500; P420B; Invitrogen, MA, USA) and NF-κβ p-65 (1:500; ab16502;

Abcam). Membranes were washed in TBS-0.1% Tween and then incubated

with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary

antibody (1:5,000; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam) for 1 h at room

temperature. Finally, membranes were developed with Clarity ECL

Western Blotting Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) and images

acquired using ImageQuant LAS 4000 mini digital imaging system

(General Electric). α-Tubulin or β-Actin were used as controls.

Lipid analysis of liver tissue

Total lipid content

Lipids were extracted with chloroform/methanol (2:1

v/v) from a wedge of fresh liver tissue (~150/200 mg) following the

Folch method adapted by Christie (25). Further details of the lipid

extraction method were published previously (23).

Lipid classes

Aliquots of 30 µg from total lipid extracts were

used for the analysis. Lipid classes were separated by

high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) in a

single-dimensional double-development following the Olsen and

Henderson method (26). Further

details of the method were published previously (23).

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) from

total lipids

1 mg of the total lipid extract was subjected to

acid-catalyzed transmethylation using toluene and sulfuric acid in

methanol, and was incubated for 16 h at 50°C to obtain the fatty

acid methyl esters (FAMEs) profile. Subsequently, FAMEs were

extracted and purified by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and

stored under a 100% nitrogen atmosphere to prevent sample

oxidation. Finally, FAMEs were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass

spectrometry (GC-MS; Agilent 7890A/7010B; Agilent Technologies,

Inc.) and identification was performed according to retention times

by library matching with NIST v.2.2 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Quantification was performed using the selected ion-monitoring mode

and the results are expressed as relative percentage areas. Further

details of the method are provided in a previously published

article (23).

Composition of FAMEs in lipid

classes

Aliquots of 2–4 mg of lipid extracts were loaded

into TLC 20×20 cm silica plates. Lipid classes were isolated in a

single-dimensional double-development following the Olsen and

Henderson method (26). The lipid

classes (LCs) were stained through spraying with

dichlorofluorescein. Then, the samples were visualized under UV

light and scraped from the silica plate. Finally, the LCs in the

silica were transmethylated at 50°C for 16 h to obtain FAMEs and

the four major LCs were selected: Phosphatidylcholine (PC),

phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylinositol (PI) and TAG.

The quantification of the samples was performed by GC-MS following

the aforementioned method. Further details can be found elsewhere

(23).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ±

standard deviation. For males, continuous variables between groups

were compared with unpaired Student's t-test, or non-parametric

Mann-Whitney test if the conditions of normality were not met. For

females, two-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey's multiple

comparisons test, Tamhane's T2 test or Dunnett's T3 test (if

variables were not homoscedastic) as post-hoc tests. Pairwise

comparisons were performed using Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni

correction if variables were not normally distributed. Fisher's

exact test was used to compare proportions between groups. Sample

size was calculated based on previous studies (21,23)

using similar obesity and ovariectomized models in which 6 to 10

cases should reach the end of the study. The present used SPSS

Statistics 20 (IBM Corp.) and GraphPad Prism 9 (Dotmatics) for

statistical analyzes and data plots, respectively. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Obesity and metabolic syndrome

The model was reported previously (21). Briefly, i) all mice on HFD

developed obesity and MS, ii) males reached higher weight than

females and iii) only obese males and obese ovariectomized females

developed hyperglycemia and insulin resistance (21).

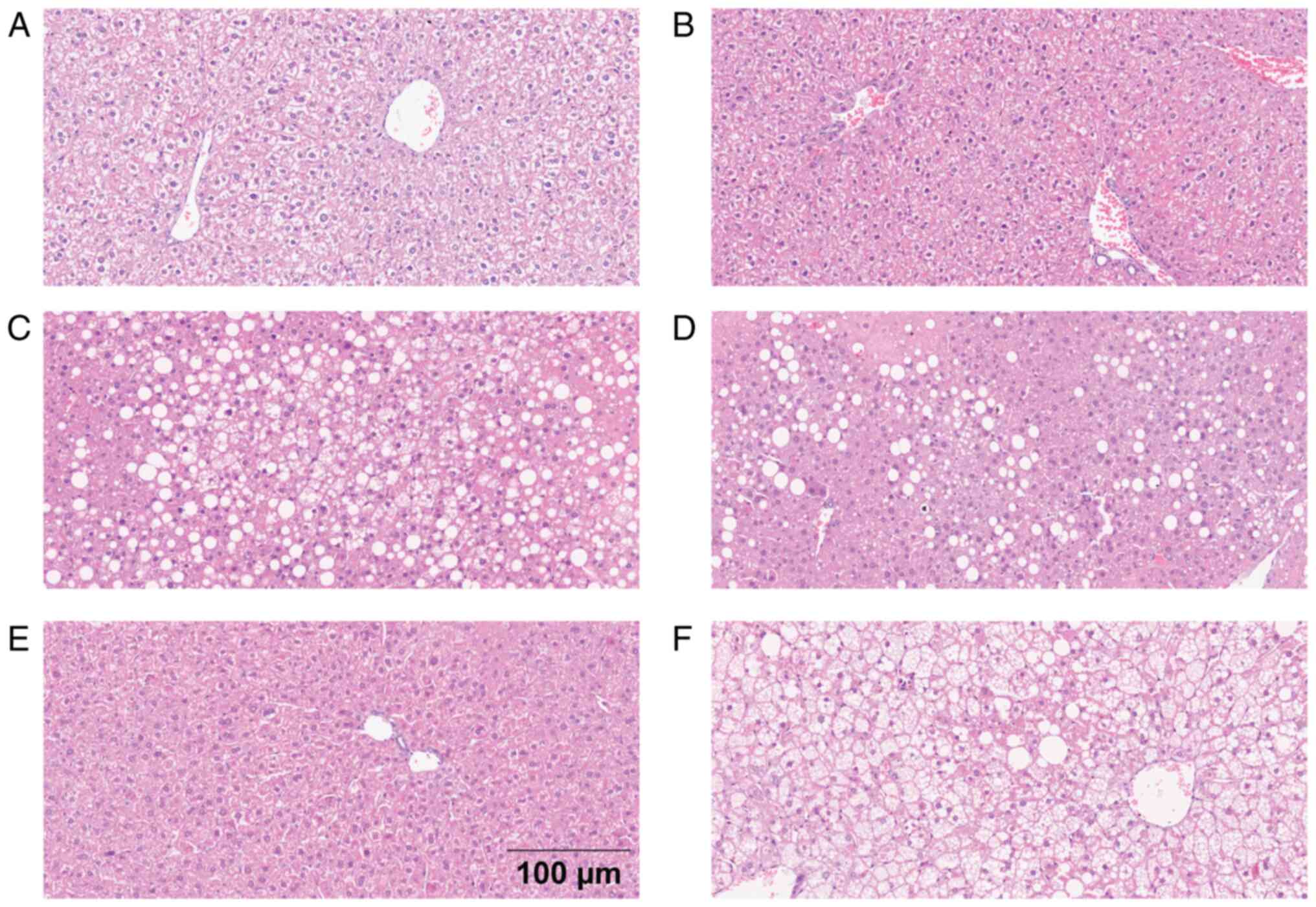

Liver histology

Females

Of the animals on HFD-OVX and HFD, 70 and 100%

showed steatosis, respectively (P>0.05), classified as severe

(27 and 57%), moderate (27 and 15%) or mild steatosis (13 and 29%).

Animals on HFD-OVX and HFD developed hepatocyte ballooning (67 and

85%), maintaining their size (60 and 57% in B1 stage) or increasing

twice or more the hepatocyte size (7 and 28% in B2 stage,

respectively; Table SII; Fig. 1). The HFD-OVX mice showed a mild

increase in collagen staining compared with SD-OVX (1.28 vs. 0.99%;

P=0.0109; Fig. S1). SD-OVX

animals presented lower collagen staining in comparison with SD

animals (0.99 vs. 1.61%; P=0.0106; Fig. S1). Despite the statistical

differences between groups, the observed fibrotic area was minimal,

representing only 1–2% of the total (Fig. S1). No differences were found

between SD and SD-OVX whereas animals on HFD and HFD-OVX had higher

steatosis and ballooning than those on SD and SD-OVX, respectively

(Table SII).

Males

Most animals on HFD developed steatosis (94%,

P<0.0001) with the following distribution: Severe (53%),

moderate (29%) and mild (12%), and ballooning (94%; P<0.0001)

where ~50% maintained the size of the hepatocyte and the other 50%

doubled the size at least (Fig.

1). Male animals on HFD presented an average of 1.10% of area

with positive collagen staining, while male animals in SD an

average of 0.77% (P=0.0124; Fig.

S1). Despite the statistical differences between groups, the

observed fibrotic area was minimal, representing only 1–2% of the

total (Fig. S1). Finally, animals

had comparable low levels of necroinflammation between groups

(Table SII).

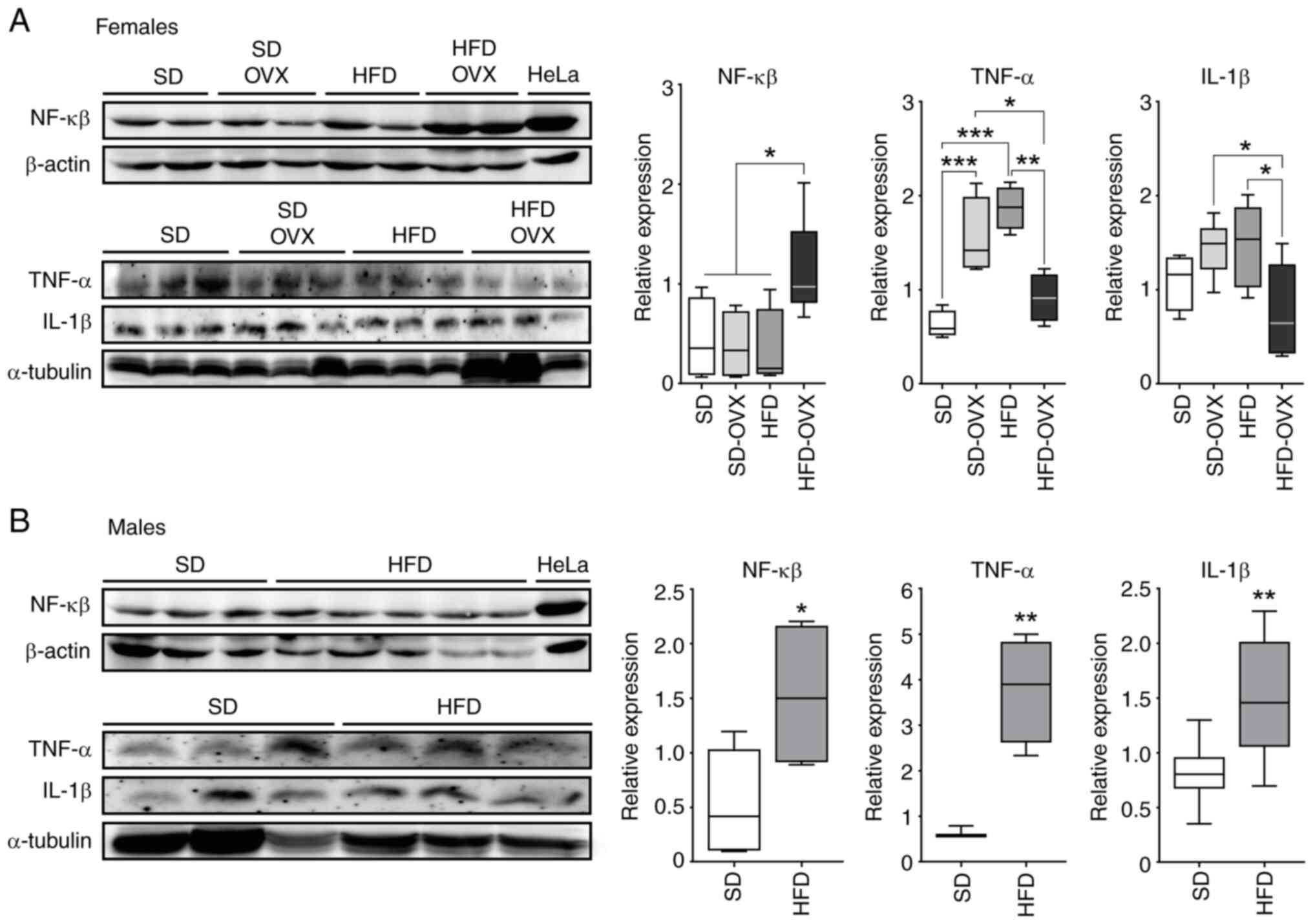

Inflammation markers in liver

tissue

Females

The HFD-OVX group showed upregulation of NF-κβ p-65

compared with HFD (P=0.013), SD-OVX (P=0.008) and SD (P=0.049)

groups. The HFD-OVX also showed lower TNF-a compared with HFD

(P=0.002) and SD-OVX (P=0.041). HFD-OVX mice showed lower levels of

IL-1B compared with HFD (P=0.048) and SD-OVX (P=0.032). Finally,

both HFD and SD-OVX animals had an increase in TNF-α compared with

SD group (P<0.001, Fig.

2A).

Males

The HFD group showed higher levels of NF-κβ p-65

(P=0.032), TNF-α (P=0.005) and IL-1β compared with controls

(P=0.006, Fig. 2B).

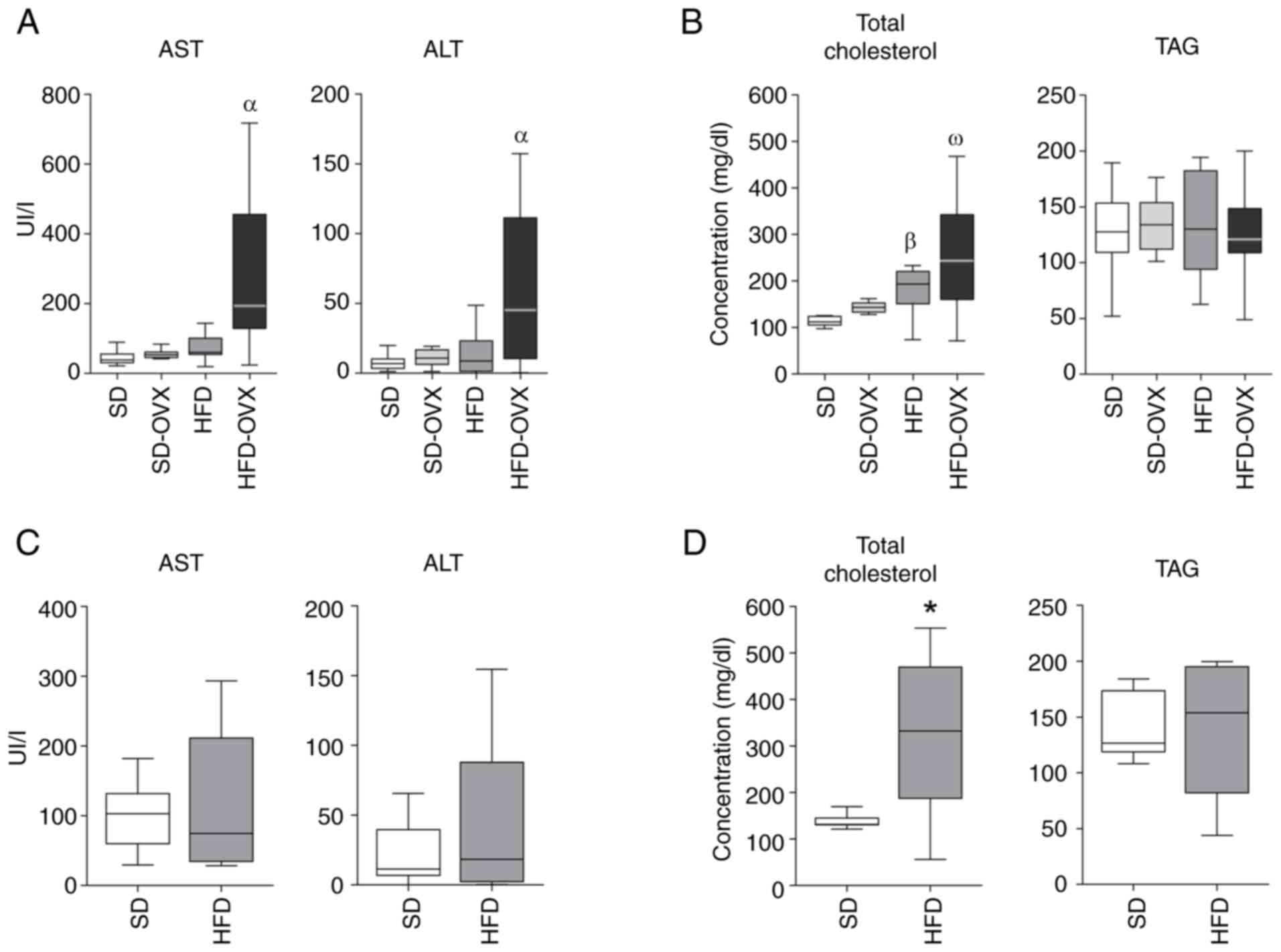

Serum analysis

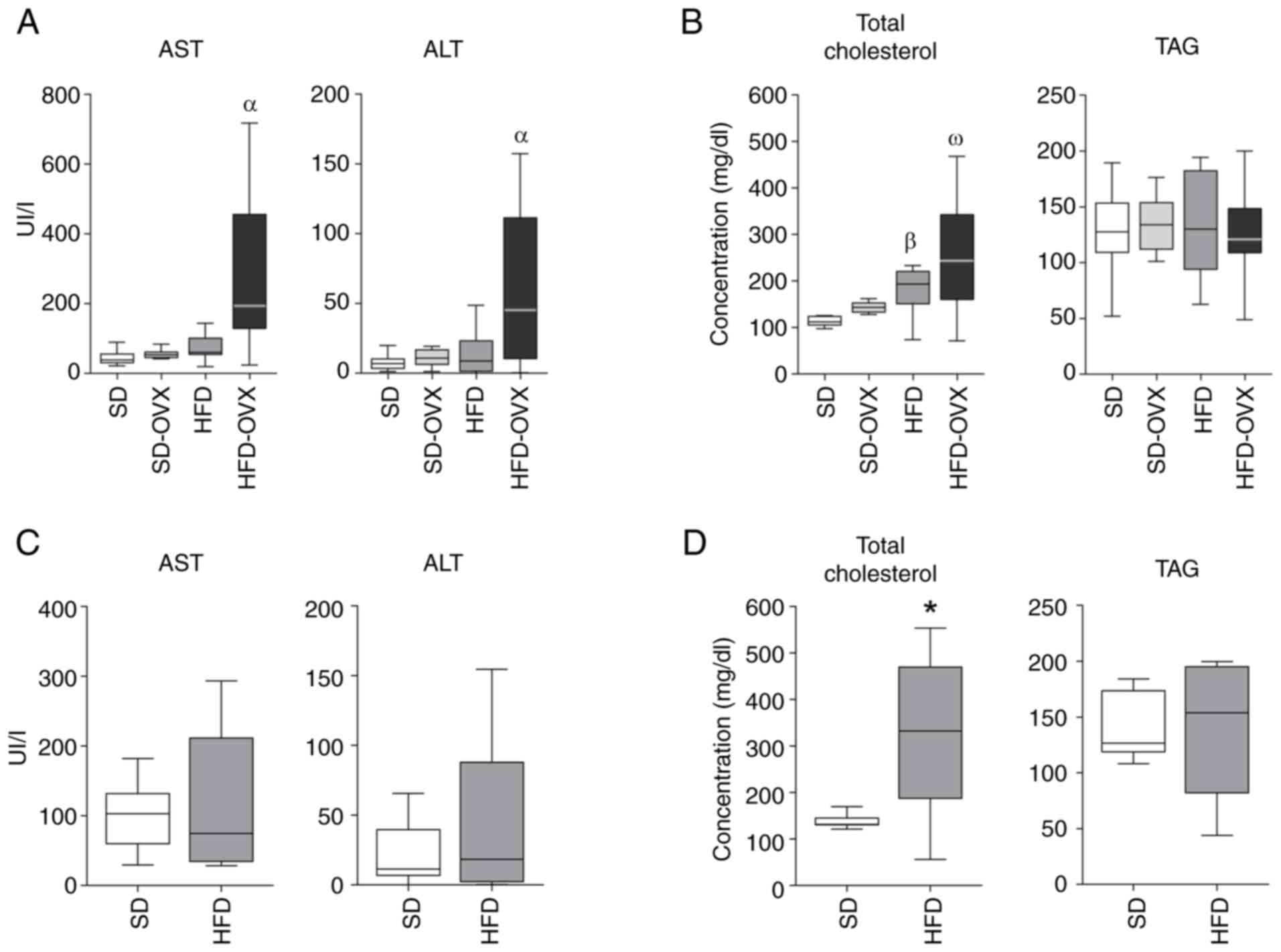

Females

The HFD-OVX showed higher levels of AST (P=0.002)

and ALT (P=0.024) compared with the SD, SD-OVX and HFD groups

(Fig. 3A). HFD and HFD-OVX both

showed higher total Chol levels compared with controls (Fig. 3B). No differences were observed in

the TAG levels among groups.

| Figure 3.Serum biochemical analysis. (A) Serum

transaminases in females. (B) Serum Chol and TAG levels in females.

(C) Serum transaminases in males. (D) Serum Chol and TAG levels in

males. Boxplots indicate the median as the horizontal line, the top

and bottom of the box show the upper and lower quartiles, maximum

and minimum values are displayed as whiskers. Female significance:

αHFD-OVX vs. HFD, SD and SD-OVX, P<0.05.

βHFD vs. SD, P<0.05, ωHFD-OVX vs. SD-OVX

and SD, P<0.05. Male significance: *HFD vs. SD, P<0.05. Chol,

free cholesterol; TAG, triglyceride AST, aspartate

aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; SD, standard diet;

HFD, high-fat diet; OVX, ovariectomized. |

Males

HFD and SD groups had comparable levels of AST, ALT

and TAG (Fig. 3C and D). The HFD

group displayed higher levels of serum total Chol (P=0.041;

Fig. 3D).

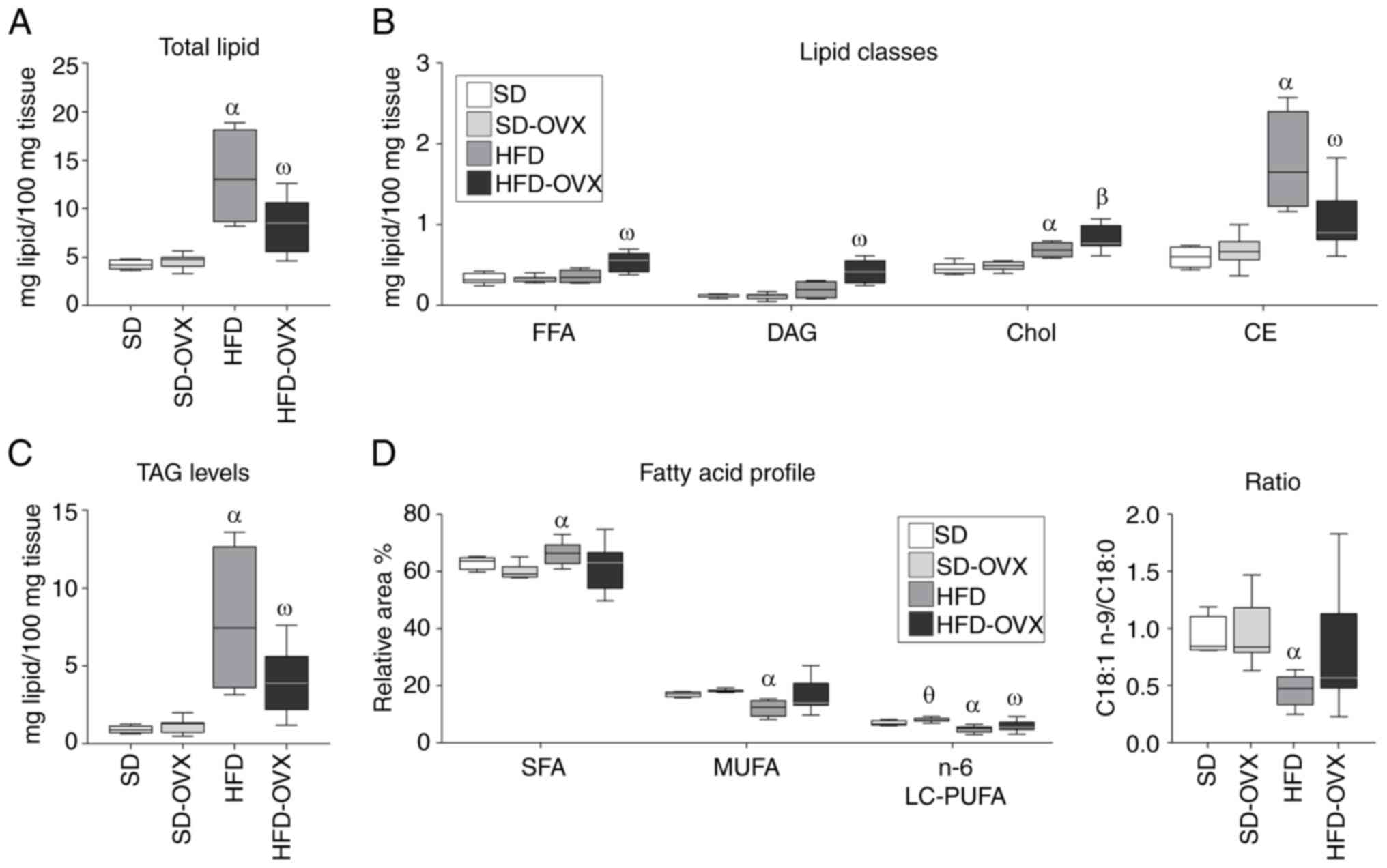

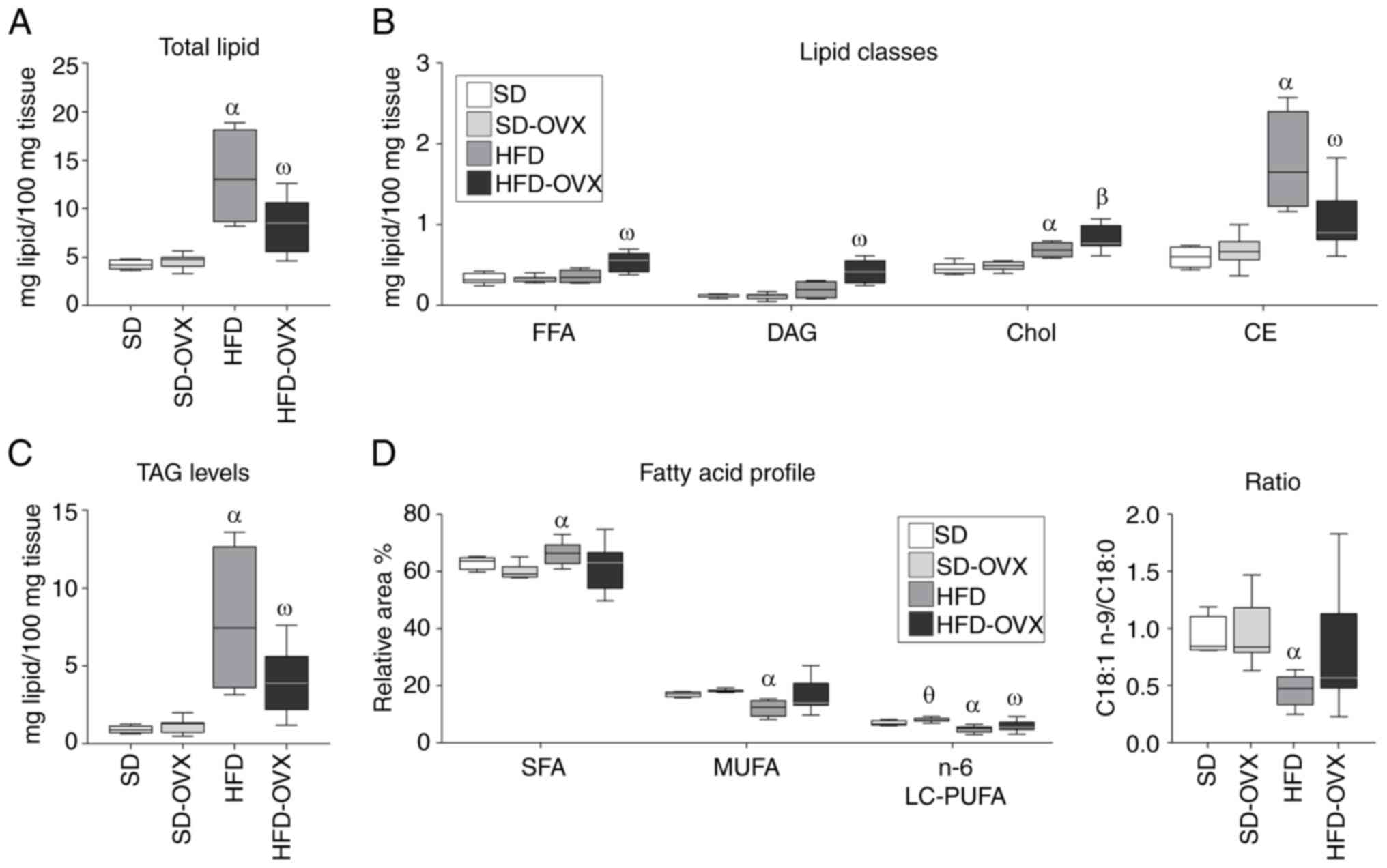

Liver lipidomics

Total hepatic lipid content in females

HFD-OVX had higher total lipid content than SD-OVX

(9.36±3.38 vs. 4.59±0.71; P<0.001) but lower than the HFD group

(9.36±3.38 vs. 13.28±5.04; P=0.027; Fig. 4A; Table SIII).

| Figure 4.Lipidomic profile of liver tissue in

female mice. (A) Total lipid content. (B) Lipid classes profile.

(C) TAG levels. (D) Fatty acid profile of females as indicated in

the figure. Boxplots show the median as the horizontal line, the

top and bottom of the box show the upper and lower quartiles,

maximum and minimum values are displayed as whiskers. Statistical

significance: αHFD vs. SD, P<0.05,

βHFD-OVX vs. SD-OVX and SD, P<0.05.

ωHFD-OVX vs. SD, SD-OVX and HFD, P<0.05.

θSD-OVX vs. SD, P<0.05. TAG, triglycerides; FFA, free

fatty acid; DAG, diglycerides; Chol, free cholesterol; CE,

cholesterol esters; SD, standard diet; HFD, high-fat diet; OVX,

ovariectomized. |

Total hepatic lipid content in

males

The HFD group showed higher total lipids compared

with the SD (13.92±6.14 vs. 4.82±0.74, P<0.001; Fig. 5A; Table SIII). Values correspond to the

mean mg total lipid/100 mg fresh tissue ± SD.

| Figure 5.Lipidomic profile of liver tissue in

male mice. (A) Total lipid content. (B) Lipid classes profile. (C)

TAG levels. (D) Fatty acid profile as indicated in the figure.

Boxplots show the median as the horizontal line, the top and bottom

of the box show the upper and lower quartiles, maximum and minimum

values are displayed as whiskers. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001. TAG,

triglycerides; FFA, free fatty acid; DAG, diglycerides; Chol, free

cholesterol; CE, cholesterol esters; SD, standard diet; HFD,

high-fat diet; OVX, ovariectomized; SFAs, saturated fatty acids;

MUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids; LC-PUFAs, long-chain

polyunsaturated fatty acids. |

Hepatic lipid classes profile in

females

HFD-OVX showed higher levels of FFA (0.54±0.12 vs.

0.36±0.08; P=0.044) and DAG (0.42±0.14 vs. 0.20±0.11; P=0.014) but

lower CE (1.06±0.35 vs. 1.76±0.62; P=0.004) and TAG (3.95±2.02 vs.

7.91±4.77; P=0.045) compared with the HFD group (Fig. 4B and C; Table SIII). Animals on HFD showed higher

levels of Chol (0.69±0.10 vs. 0.42±0.07; P=0.002), CE (1.76±0.62

vs. 0.57±0.12; P=0.002) and TAG (7.91±4.77 vs. 0.92±0.23; P=0.006)

compared with the SD group.

Hepatic lipid classes profile in

females

The HFD group showed increased FFA compared with SD

group (0.86±0.21 vs. 0.38±0.10, P<0.001), DAG (0.55±0.16 vs.

0.13±0.04, P<0.001), TAG (9.06±4.93 vs. 1.02±0.35, P<0.001),

Chol (0.95±0.17 vs. 0.57±0.09, P<0.001) and CE (0.96±0.44 vs.

0.41±0.12, P<0.05) (Fig. 5B and

C; Table SIII).

FAMEs profile of total lipids

Females

The HFD-OVX had lower 16:0 but higher 18:2 n-6 and

18:3 n-6 compared with the SD group (Fig. 4D; Table SIV). The HFD group showed lower

levels of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), omega-6 long-chain

polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-6 LC-PUFA) and 18:1 n-9/18:0 ratio

compared with animals on SD (Table

SIV). Finally, the total FAMEs profile of the HFD group showed

lower 18:1 and 20:4 n-6 (arachidonic acid; ARA) but higher 18:0,

18:2 n-6, 18:3 n-6 and 18:3 n-3 compared with the SD group

(Fig. 4D; Table SIV).

Males

The FA profile showed that the HFD group had lower

SFA (53.36±5.83 vs. 59.64±2.13; P<0.001) and n-6 LC-PUFA

(4.98±1.95 vs. 8.71±1.98; P<0.001) but also higher MUFA

(25.17±4.68 vs. 17.37±4.77, P<0.001) and 18:1 n-9/18:0 ratio

(2.88±1.44 vs. 1.12±0.47; P<0.001) compared with SD (Fig. 5D; Table SIV). The HFD group also showed

lower 18:0, 20:4 n-6 and 22:6 n-3 (docosahexaenoic acid; DHA), and

higher 14:0, 18:1, 20:1, 18:2 n-6, 18:3 n-6, 20:2 n-6, and 18:3 n-3

compared with the SD group (Fig.

5D; Table SIV).

FAMEs profile of lipid classes

Females

HFD-OVX showed lower 16:0 in PC and higher 18:0

dimethyl acetal (DMA) in PE compared with all other groups. The HFD

group had lower 20:3 n-6 in PC, PI and PE) 16:1 and 18:1 (in PC and

PE), and higher 18:0 (in PC and PE) and 22:6 n-3 (in PC) compared

with the SD (Tables SV, SVI and SVII). HFD and HFD-OVX groups both had in

TAG a lower SFA and MUFA (14:0, 16:1 and 18:1) and higher

polyunsaturated (PUFAs) profile (20:3 n-6, 20:4 n-6, 22:4 n-6, 22:5

n-6 and 22:6 n-3) compared with SD and SD-OVX (Table SVIII).

Males

The HFD had lower 20:1 (in PC, PE and PI), 16:0,

16:1, 18:2 n-6 and 22:5 n-3 (in PC and PE) and higher 18:0, 20:4

n-6, 22:6 n-3 (in PC and PE) and 18:0 DMA (in PE) compared with SD

(Table SV, SVI and SVII). In TAG, the HFD group had lower

SFAs and MUFAs (14:0, 16:0, 16:1) and higher PUFAs (18:3 n-3, 20:2

n-6, 20:4 n-6, 22:4 n-6 and 22:6 n-3) compared with SD (Table SVIII).

Discussion

The main finding of the present study was that

ovariectomy in obese female mice caused severe hepatic lipotoxicity

and liver damage. Only obese males and obese-ovariectomized females

developed insulin resistance (21)

and impaired lipid droplet formation with a consequent accumulation

of toxic lipid intermediaries (FFA, DAG and Chol). These markers of

hepatic lipotoxicity were associated with inflammation in both

groups. Notably, only obese-ovariectomized females had signs of

liver injury in serum analysis, evidenced by higher transaminases

levels. These findings suggest that the lack of estrogen may lead

to detrimental effects in the context of obesity and insulin

resistance, thus potentially promoting chronic liver damage.

The present study used a well-established model of

obesity and metabolic syndrome to investigate the effects of these

conditions on hepatic lipid metabolism. Furthermore, to examine the

role of estrogen in the progression of liver damage, the present

study performed ovariectomy on a subgroup of female mice (21,23).

As expected, obese female (both ovariectomized or not) and male

mice exhibited liver steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning, mild

fibrosis and expression of pro-inflammatory markers. Importantly,

while chronic changes (especially fibrosis) were minimal, severe

steatosis and ballooning were the most significant histological

markers of damage in obese males. This suggested that the model

reflected early-state damage, consistent with previous findings in

preclinical and clinical models (27,28).

Notably, sex markedly influenced the effect of obesity on the

hepatic profile. Compared with obese males, obese female mice

exhibited a lower degree of steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning and

expression of inflammatory markers. Again, chronic fibrotic changes

were minimal and the most important histological marker in

ovariectomized obese females was a trend towards reduced steatosis.

These findings in males suggested that the current model reflected

an early stage of damage, thus, longer-term models might be

necessary to fully characterize chronic damage progression.

Similarly, the hepatic lipid metabolism was less affected in

females, as they displayed high levels of Chol and CE whereas obese

males had elevated Chol, CE, DAG and FFA. The hepatic accumulation

of DAG and FFA is associated with the development of obesity,

insulin resistance and NAFLD (29,30).

Markedly, ovariectomy in obese female mice resulted in lower

hepatic TAG and CE and higher levels of cytotoxic FFA, DAG and

Chol. These differences reflected the protective role of estrogen

on regulating the packaging of FFA and DAG into TAG to form lipid

droplets in the liver (31).

In the context of lipotoxicity, the accumulation of

lipids, particularly FFA and DAG, can lead to changes in the

phospholipid profile, contributing to inflammation, cell

dysfunction, and organ damage. The present study observed a

significant reduction in total phospholipids in obese mice,

representing only 20% of total lipids, almost twice the value

obtained in lean animals. The low proportion of phospholipids in

relation to neutral lipids might impair membrane fluidity and cell

functioning. Furthermore, inflammation in liver has been associated

with alterations in phosphatidylserine and PE levels (32). The present study found a mild

increment in these phospholipids in HFD-OVX mice as well as a

markedly elevated Chol/PC ratio, which has been associated with

liver injury (33). Altogether,

these findings may indicate that the loss of estrogen in the

context of obesity and insulin resistance may induce hepatic

lipotoxicity, promoting inflammation and chronic liver damage.

However, more studies are needed to clarify this pathway.

The complex interplay between insulin and estrogen

may be key to understanding the results obtained in the current

study, as they have a profound impact on lipid metabolism. On one

hand, insulin modulates lipid metabolism in the hepatocyte by i)

promoting lipogenesis from glucose and other metabolites (34), ii) mediating the packing of FFA and

DAG into TAG (35), iii) promoting

the esterification of Chol (36),

and iv) regulating the correct lipid droplet formation via SREBP1

and mTORC1 (37). Given the

toxicity of FFA, DAG, and Chol (11,12,38–41),

insulin's promotion of lipogenesis and lipid droplet formation can

be considered ‘cell protective’ in the context of lipid

accumulation (8,35,42).

However, obesity and MS can eventually induce insulin resistance in

the hepatocytes. Consequently, reduced insulin responsiveness may

impair lipid droplet synthesis and elevate FFA, DAG and Chol

levels, thereby increasing hepatic toxicity, as observed in our

model.

On the other hand, several studies have found that

estrogen promotes insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in muscle

and liver (43,44). Estrogen and insulin can both

regulate lipogenesis via E2-induced activation of PI3K-Akt-Foxo1

(45). Therefore, these hormones

may facilitate neutral lipid droplet formation that protects from

toxic intermediaries in obesity (46). This may explain the impaired

hepatic lipid deposition associated with liver injury observed in

obese ovariectomized mice (Fig.

S2). Clinical trials have shown that estrogen replacement

improved insulin sensitivity and glucose levels in diabetic

postmenopausal women (47–49). Following ovariectomy in obese

female mice, estrogen supplementation reduced DAG accumulation in

the liver (44). In male mice with

obesity, estrogen administration prevented diet-induced hepatic

insulin resistance, hyperglycemia and the elevation in DAG levels

(50). Furthermore, a study has

shown that estrogen supplementation improved peripheral insulin

sensitivity and increased TAG levels in the liver of obese turkeys

(51). Notably, the metabolic

changes induced by ovariectomy depend on the nutritional status. In

murine models, ovariectomy in obese mice can result in a decreased

expression of genes related to lipid metabolism in adipose tissue,

liver and skeletal muscle, contributing to increased fat

accumulation as well as toxic lipids intermediaries (52,53).

By contrast, in non-obese mice, these effects are less pronounced,

suggesting that obesity amplifies the metabolic alterations induced

by estrogen deficiency (54). In

humans, the transition to menopause, which involves a natural

decline in estrogen levels, has been associated with increased

central adiposity and metabolic alterations, indicating parallels

to findings in animal models (55,56).

Lipid droplet formation is an essential metabolic

mechanism to circumvent hepatic lipotoxicity in conditions of

excessive energy intake (57).

Sequestration of FFA and DAG into inert TAG and CE within lipid

droplets is crucial for mitigating hepatic lipotoxicity. FFA, DAG

and Chol cannot readily enter lipid droplets due to their polar

groups (57). Thus, TAG and CE

serve to sequester these cytotoxic intermediaries to form the

neutral core of lipid droplets (58). Limiting lipid droplet formation can

be deleterious for hepatocytes, as elevated levels of FFA, DAG and

Chol are harmful to these cells (10–13,40).

For instance, FFA can induce lipid peroxidation and the activation

of TLR4 (12,59). DAG can induce inflammation and

impaired autophagy via PKC activation (11,13).

Furthermore, Chol can activate the unfolded protein response and

promote ER stress (14,15). Notably, increased levels of FFA,

DAG and Chol can promote the activation of NF-κβ and the initiation

of inflammatory pathways, in accordance with the present results

(53,60–62).

Differences in the hepatic FA profile between obese

and lean mice are related to differences in the dietary FA

composition. However, dysregulations of the metabolic pathway

involved in the synthesis/utilization of FAs were pronounced in

mice fed with HFD. On one hand, the present study found sexual

dimorphism in the distribution of FA in the liver of female and

male mice: Obese females (irrespective of ovariectomy) had higher

SFAs, lower MUFAs and lower n-6 LC-PUFAs whereas obese males showed

lower SFAs, higher MUFAs and lower n-6 LC-PUFAs. Taking into

account that SFAs are more toxic than MUFAs (5), the FA profile of males may indicate a

greater capacity to convert these SFAs into more inert MUFAs, as a

protective pathway against SFA-induced toxicity. These differences

might indicate sex-specific mechanisms to compensate metabolic

insults that should be further explored in future experiments.

Additionally, ARA (20:4 n-6) and consequently ARA/DHA ratio were

depleted in hepatic total lipids of all obese animals. As ARA is

the main precursor of proinflammatory prostanoids, this reduction

could be related to its increased utilization for the synthesis of

prostaglandins, thromboxanes and leukotrienes (63). Consistently, obese ovariectomized

females had the highest levels of DMAs in PE (chiefly 18:0 DMA, see

Table SVI). DMAs are precursors

for de novo biosynthesis of plasmalogens which are receiving

increasing attention due to their antioxidant role and their

involvement in mammalian anti-inflammatory responses (64). This aligns well with the higher

proportion of essential PUFAs, such as EPA and DHA in hepatic TAG

of obese mice that might be attributed to the described ability of

plasmalogens to reduce oxidative degradation (65).

NAFLD is associated with high SFA and Chol levels

that inhibit desaturase activity (66,67).

Notably, the present study revealed a decreased product 18C

precursor ratios for both n-6 and n-3 pathways in hepatic total

lipids, suggesting that delta-6 and delta-5-desaturase activities,

which catalyze the conversion of shorter chain precursors linoleic

acid (18:2 n-6) and linolenic acid (18:3 n-3) into their longer and

more unsaturated counterparts, might be impaired. Consistently, the

present study observed a decreased 18:1 n-9 proportion and 18:1

n-9/18:0 ratio in obese female mice; probably linked to the

proinflammatory status of this group. Chena et al (68) demonstrated the protective mechanism

of oleic acid (18:1 n-9) against SFA-induced hepatocyte

lipotoxicity in primary hepatocytes of rats with NASH, including

apoptosis, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction,

inflammation and fibrosis. Thus, an impairment of stearoyl-CoA

desaturase (delta-9 desaturase) involved in the conversion of 18:0

to 18:1 n-9 could be responsible for this reduction. The connection

between the observed lipid profile with the hepatic desaturase

activities must be addressed in future studies.

Several therapeutic strategies that involve

regulation of lipid metabolism and inflammation are being explored

for NAFLD (69–75), including the use of SIRT1

activators (70), AMPK modulators

(71), gut microbiota

interventions (72) and hormone

replacement therapy in the context of menopause (73). These approaches aim to reduce

hepatic lipotoxicity, improve insulin sensitivity, and ameliorate

inflammation. Among them, SIRT1 activation has gained attention for

its role in suppressing NF-κβ signaling and mitigating disease

progression (70). In the present

study, NF-κβ upregulation in obese ovariectomized mice, along with

increased transaminases, suggested an impairment in SIRT1 pathway,

and highlights the need to explore its therapeutic potential in

menopause-related liver injury. Finally, it is worth considering

that the alterations in inflammation and lipid metabolism are

related to cardiovascular disease, the main cause of death in

patients with NASH and NAFLD (74,75).

An important strength of the present study is that

it is among the few studies that analyze the interplay between

estrogen deficiency and obesity in mice. Most previous studies have

focused solely on males. Thus, sex-based comparisons may provide

valuable insights that pave the way for more efficient treatments

of metabolic disorders. One straightforward interpretation of the

present results is that the lack of sex hormones might predispose

females to more severe damage, mirroring the situation in males.

Furthermore, the comparison revealed that obese females did not

experience the same detrimental effects as obese males, which can

be attributed to the protective effect of estrogen. These results

demonstrated that ovariectomy generally worsened the hepatic

profile in obese females. However, the present study has

limitations. The first pertains to the applicability of

pre-clinical models to humans. As mouse lipid metabolism differs

from human metabolism, these findings should be confirmed in large

animal models and human studies. The duration of the experiment is

relatively short, and this may explain the mild fibrosis and

moderate variations in the hepatic fatty acid profile observed in

the model. Chronic animal models (small and large) are expensive,

which may compromise their viability in research projects. In any

case, larger periods of follow up could improve our understanding

about the impact of menopause in MS and liver disease.

In conclusion, ovariectomy in obese animals

exacerbated hepatic lipotoxicity, accelerating the progression of

liver injury. This suggested that estrogen loss may contribute to

the onset of hepatic damage in the context of obesity and insulin

resistance. Furthermore, estrogen may exert its protective effect

through the regulation of lipid droplet formation when insulin

action is impaired. Further experiments are needed to unveil

mechanistic insights, which may open therapeutic opportunities.

Additional research in sex differences regarding liver disease may

also contribute to achieve an improved understanding of the NAFLD

and NASH pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III

(STT received grant no. PFIS-FI20/00147; EP received grant no.

PI19/01756 and AERR, who is a recipient of a contract from the Sara

Borrell program, received grant no. CD21/00142). This research was

also funded by the SENEFRO foundation (Sociedad Española de

Nefrología) and European Commission, HORIZON-WIDERA-2021-ACCESS-03

through Diabetes Obesity and the Kidney project (grant no.

PN:101079207).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AERR, EP and MHG designed, discussed and supervised

the study; AERR, EP, AAA, JDG, SLL, BAP, AHB, MIH, SGH, LDM and STT

performed the experiments, data analyses and result plotting; AAA,

JDG, JAPP, NGAG and CRG collaborated in the data interpretation,

drafting and revising the manuscript; AERR, EP, MHG, AAA and JDG

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Animal care was performed in accordance with

institutional guidelines in compliance with Spanish (Real Decreto

53/2013, February 1. BOE, February 8, 2013, n: 34, p. 11370-11421)

and international laws and policies (Directive 2010/63/EU of the

European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the

protection of animals used for scientific purposes) and were

approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Comité

de Ética de la Investigación y de Bienestar Animal of University of

La Laguna, Spain). The ethics committee approval number was

CEIBA2021-3107.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CE

|

cholesteryl esters

|

|

Chol

|

free cholesterol

|

|

DAG

|

diacylglycerol

|

|

FA

|

fatty acids

|

|

FAMEs

|

fatty acid methyl esters

|

|

FFA

|

free fatty acids

|

|

GC

|

gas chromatography

|

|

HFD

|

high-fat diet

|

|

HFD-OVX

|

ovariectomized animals on high-fat

diet

|

|

IR

|

insulin resistance

|

|

LC-PUFAs

|

long-chain polyunsaturated fatty

acids

|

|

MS

|

metabolic syndrome

|

|

MUFAs

|

monounsaturated fatty acids

|

|

n-3

|

omega-3 fatty acids

|

|

n-6

|

omega-6 fatty acids

|

|

NAFLD

|

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

|

|

NASH

|

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

disease

|

|

PC

|

phosphatidylcholine

|

|

PE

|

phosphatidylethanolamine

|

|

PI

|

phosphatidylinositol

|

|

PUFAs

|

polyunsaturated fatty acids

|

|

SD

|

standard diet

|

|

SD-OVX

|

ovariectomized animals on standard

diet

|

|

SFAs

|

saturated fatty acids

|

|

TAG

|

triacylglycerol

|

|

TLC

|

thin-layer chromatography

|

References

|

1

|

Boutari C and Mantzoros CS: A 2022 update

on the epidemiology of obesity and a call to action: As its twin

COVID-19 pandemic appears to be receding, the obesity and

dysmetabolism pandemic continues to rage on. Metabolism.

133:1552172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel

Y, Henry L and Wymer M: Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty

liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence,

and outcomes. Hepatology. 64:73–84. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Noureddin M, Vipani A, Bresee C, Todo T,

Kim IK, Alkhouri N, Setiawan VW, Tran T, Ayoub WS, Lu SC, et al:

NASH leading cause of liver transplant in women: Updated analysis

of indications for liver transplant and ethnic and gender

variances. Am J Gastroenterol. 113:1649–1659. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Baffy G, Brunt EM and Caldwell SH:

Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An

emerging menace. J Hepatol. 56:1384–1391. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Geng Y, Faber KN, de Meijer VE, Blokzijl H

and Moshage H: How does hepatic lipid accumulation lead to

lipotoxicity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? Hepatol Int.

15:21–35. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bugianesi E, Moscatiello S, Ciaravella MF

and Marchesini G: Insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease. Curr Pharm Des. 16:1941–1951. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Rada P, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A,

Garcia-Monzon C and Valverde AM: Understanding lipotoxicity in

NAFLD pathogenesis: Is CD36 a key driver? Cell Death Dis.

11:8022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Listenberger LL, Han X, Lewis SE, Cases S,

Farese RV Jr, Ory DS and Schaffer JE: Triglyceride accumulation

protects against fatty Acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 100:3077–3082. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tripathy D, Mohanty P, Dhindsa S, Syed T,

Ghanim H, Aljada A and Dandona P: Elevation of free fatty acids

induces inflammation and impairs vascular reactivity in healthy

subjects. Diabetes. 52:2882–2887. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hommelberg PP, Plat J, Langen RC, Schols

AM and Mensink RP: Fatty Acid-induced NF-kappaB activation and

insulin resistance in skeletal muscle are chain length dependent.

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 296:E114–E120. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li D, Yang SG, He CW, Zhang ZT, Liang Y,

Li H, Zhu J, Su X, Gong Q and Xie Z: Excess diacylglycerol at the

endoplasmic reticulum disrupts endomembrane homeostasis and

autophagy. BMC Biol. 18:1072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I,

Yin H and Flier JS: TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty

acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 116:3015–3025.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gassaway BM, Petersen MC, Surovtseva YV,

Barber KW, Sheetz JB, Aerni HR, Merkel JS, Samuel VT, Shulman GI

and Rinehart J: PKCε contributes to lipid-induced insulin

resistance through cross talk with p70S6K and through previously

unknown regulators of insulin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

115:E8996–E9005. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tabas I: Free cholesterol-induced

cytotoxicity a possible contributing factor to macrophage foam cell

necrosis in advanced atherosclerotic lesions. Trends Cardiovasc

Med. 7:256–263. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tabas I: Consequences of cellular

cholesterol accumulation: Basic concepts and physiological

implications. J Clin Invest. 110:905–911. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Song Y, Liu J, Zhao K, Gao L and Zhao J:

Cholesterol-induced toxicity: An integrated view of the role of

cholesterol in multiple diseases. Cell Metab. 33:1911–1925. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kong FJ, Wu JH, Sun SY and Zhou JQ: The

endoplasmic reticulum stress/autophagy pathway is involved in

cholesterol-induced pancreatic beta-cell injury. Sci Rep.

7:447462017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gan LT, Van Rooyen DM, Koina ME, McCuskey

RS, Teoh NC and Farrell GC: Hepatocyte free cholesterol

lipotoxicity results from JNK1-mediated mitochondrial injury and is

HMGB1 and TLR4-dependent. J Hepatol. 61:1376–1384. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Pu D, Tan R, Yu Q and Wu J: Metabolic

syndrome in menopause and associated factors: A meta-analysis.

Climacteric. 20:583–591. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Janssen I, Powell LH, Crawford S, Lasley B

and Sutton-Tyrrell K: Menopause and the metabolic syndrome: The

Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Arch Intern Med.

168:1568–1575. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rodriguez-Rodriguez AE, Donate-Correa J,

Luis-Lima S, Diaz-Martin L, Rodriguez-Gonzalez C, Perez-Perez JA,

Acosta-González NG, Fumero C, Navarro-Díaz M, López-Álvarez D, et

al: Obesity and metabolic syndrome induce hyperfiltration,

glomerulomegaly, and albuminuria in obese ovariectomized female

mice and obese male mice. Menopause. 28:1296–1306. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Stevenson JC: Metabolic effects of hormone

replacement therapy. J Br Menopause Soc. 10:157–161. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Afonso-Ali A, Porrini E, Teixido-Trujillo

S, Perez-Perez JA, Luis-Lima S, Acosta-Gonzalez NG, Sosa-Paz I,

Díaz-Martín L, Rodríguez-González C and Rodríguez-Rodríguez AE: The

role of gender differences and menopause in Obesity-related renal

disease, renal inflammation and lipotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci.

24:129842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bedossa P, Poitou C, Veyrie N, Bouillot

JL, Basdevant A, Paradis V, Tordjman J and Clement K:

Histopathological algorithm and scoring system for evaluation of

liver lesions in morbidly obese patients. Hepatology. 56:1751–1759.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Christie WW: Gas Chromatography and

Lipids: A practical guide. Oily Press; 1989

|

|

26

|

Olsen RE and Henderson RJ: The rapid

analysis of neutral and polar marine lipids using

double-development HPTLC and scanning densitometry. J Exp Mar Bio

Ecol. 129:189–197. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Echeverria F, Valenzuela R, Bustamante A,

Alvarez D, Ortiz M, Espinosa A, Illesca P, Gonzalez-Mañan D and

Videla LA: High-fat diet induces mouse liver steatosis with a

concomitant decline in energy metabolism: Attenuation by

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) or hydroxytyrosol (HT) supplementation

and the additive effects upon EPA and HT co-administration. Food

Funct. 10:6170–6183. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sanyal AJ, Williams SA, Lavine JE,

Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Alexander L, Ostroff R, Biegel H, Kowdley

KV, Chalasani N, Dasarathy S, et al: Defining the serum proteomic

signature of hepatic steatosis, inflammation, ballooning and

fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol.

78:693–703. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Teng X and Wang Y: Diacylglycerols as

lipid mediators in metabolic diseases: Insights from their role in

insulin resistance. Mol Metabolism. 21:86–98. 2019.

|

|

30

|

Bays HE and Tressler JA: Lipotoxicity: A

review of the relationship between obesity, type 2 diabetes, and

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metabolism.

95:415–425. 2010.

|

|

31

|

Palmisano BT, Zhu L and Stafford JM: Role

of estrogens in the regulation of liver lipid metabolism.

Homeostasis, Diabetes and Obesity, Advances in Experimental

Medicine and Biology 1043. Springer International Publishing AG;

pp. 227–256. 2017

|

|

32

|

Shama S, Jang H, Wang X, Zhang Y, Shahin

NN, Motawi TK, Kim S, Gawrieh S and Liu W:

Phosphatidylethanolamines are associated with nonalcoholic fatty

liver disease (NAFLD) in obese adults and induce liver cell

metabolic perturbations and hepatic stellate cell activation. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:10342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Puri P, BaillieR A, Wiest MM, Mirshahi F,

Choudhury J, Cheung O, Sargeant C, Contos MJ and Sanyal AJ: A

lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology.

46:1081–1090. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Haas JT, Miao J, Chanda D, Wang Y, Zhao E,

Haas ME, Hirschey M, Vaitheesvaran B, Farese RV Jr, Kurland IJ, et

al: Hepatic insulin signaling is required for obesity-dependent

expression of SREBP-1c mRNA but not for feeding-dependent

expression. Cell Metab. 15:873–884. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Czech MP, Tencerova M, Pedersen DJ and

Aouadi M: Insulin signaling mechanisms for triacylglycerol storage.

Diabetologia. 56:949–964. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

O'Rourke L, Gronning LM, Yeaman SJ and

Shepherd PR: Glucose-dependent regulation of cholesterol ester

metabolism in macrophages by insulin and leptin. J Biol Chem.

277:42557–42562. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Laplante M and Sabatini DM: An emerging

role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr Biol. 19:R1046–R1052.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chitraju C, Mejhert N, Haas JT,

Diaz-Ramirez LG, Grueter CA, Imbriglio JE, Pinto S, Koliwad SK,

Walther TC and Farese RV Jr: Triglyceride synthesis by DGAT1

protects adipocytes from Lipid-induced ER stress during lipolysis.

Cell Metab. 26:407–18.e3. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kellner-Weibel G, Jerome WG, Small DM,

Warner GJ, Stoltenborg JK, Kearney MA, Corjay MH, Phillips MC and

Rothblat GH: Effects of intracellular free cholesterol accumulation

on macrophage viability: A model for foam cell death. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 18:423–4231. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Ly LD, Xu S, Choi SK, Ha CM, Thoudam T,

Cha SK, Wiederkehr A, Wollheim CB, Lee IK and Park KS: Oxidative

stress and calcium dysregulation by palmitate in type 2 diabetes.

Exp Mol Med. 49:e2912017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Warner GJ, Stoudt G, Bamberger M, Johnson

WJ and Rothblat GH: Cell toxicity induced by inhibition of acyl

coenzyme A: Cholesterol acyltransferase and accumulation of

unesterified cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 270:5772–5778. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bosma M, Dapito DH, Drosatos-Tampakaki Z,

Huiping-Son N, Huang LS, Kersten S, Drosatos K and Goldberg IJ:

Sequestration of fatty acids in triglycerides prevents endoplasmic

reticulum stress in an in vitro model of cardiomyocyte

lipotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1841:1648–1655. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Gupte AA, Pownall HJ and Hamilton DJ:

Estrogen: An emerging regulator of insulin action and mitochondrial

function. J Diabetes Res. 2015:9165852015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhu L, Brown WC, Cai Q, Krust A, Chambon

P, McGuinness OP and Stafford JM: Estrogen treatment after

ovariectomy protects against fatty liver and may improve

pathway-selective insulin resistance. Diabetes. 62:424–434. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yan H, Yang W, Zhou F, Li X, Pan Q, Shen

Z, Han G, Newell-Fugate A, Tian Y, Majeti R, et al: Estrogen

improves insulin sensitivity and suppresses gluconeogenesis via the

transcription factor foxo1. Diabetes. 68:291–304. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

De Paoli M, Zakharia A and Werstuck GH:

The role of estrogen in insulin resistance: A review of clinical

and preclinical data. Am J Pathol. 191:1490–1498. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cuadros JL, Fernandez-Alonso AM, Chedraui

P, Cuadros AM, Sabatel RM and Perez-Lopez FR: Metabolic and

hormonal parameters in post-menopausal women 10 years after

transdermal oestradiol treatment, alone or combined to micronized

oral progesterone. Gynecol Endocrinol. 27:156–162. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Os I, Os A, Abdelnoor M, Larsen A,

Birkeland K and Westheim A: Insulin sensitivity in women with

coronary heart disease during hormone replacement therapy. J Womens

Health (Larchmt). 14:137–145. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Soranna L, Cucinelli F, Perri C, Muzj G,

Giuliani M, Villa P and Lanzone A: Individual effect of E2 and

dydrogesterone on insulin sensitivity in post-menopausal women. J

Endocrinol Invest. 25:547–550. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhu L, Martinez MN, Emfinger CH, Palmisano

BT and Stafford JM: Estrogen signaling prevents diet-induced

hepatic insulin resistance in male mice with obesity. Am J Physiol

Endocrinol Metab. 306:E1188–E1197. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Dashti N, Kelley JL, Thayer RH and Ontko

JA: Concurrent inductions of avian hepatic lipogenesis, plasma

lipids, and plasma apolipoprotein B by estrogen. J Lipid Res.

24:368–380. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Rogers NH, Perfield JW II, Strissel KJ,

Obin MS and Greenberg AS: Reduced energy expenditure and increased

inflammation are early events in the development of

ovariectomy-induced obesity. Endocrinology. 150:2161–2168. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ludgero-Correia A Jr, Aguila MB,

Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA and Faria TS: Effects of high-fat diet on

plasma lipids, adiposity, and inflammatory markers in

ovariectomized C57BL/6 mice. Nutrition. 28:316–323. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kamei Y, Suzuki M, Miyazaki H,

Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N, Wu J, Ishimi Y and Ezaki O: Ovariectomy in

mice decreases lipid metabolism-related gene expression in adipose

tissue and skeletal muscle with increased body fat. J Nutr Sci

Vitaminol (Tokyo). 51:110–117. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ozbey N, Sencer E, Molvalilar S and Orhan

Y: Body fat distribution and cardiovascular disease risk factors in

pre- and postmenopausal obese women with similar BMI. Endocr J.

49:503–509. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Ambikairajah A, Walsh E and Cherbuin N:

Lipid profile differences during menopause: A review with

meta-analysis. Menopause. 26:1327–1333. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zadoorian A, Du X and Yang H: Lipid

droplet biogenesis and functions in health and disease. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 19:443–459. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Olzmann JA and Carvalho P: Dynamics and

functions of lipid droplets. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:137–155.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Nosadini R and Tonolo G: Role of oxidized

low density lipoproteins and free fatty acids in the pathogenesis

of glomerulopathy and tubulointerstitial lesions in type 2

diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 21:79–85. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Shen T, Li X, Jin B, Loor JJ, Aboragah A,

Ju L, Fang Z, Yu H, Chen M, Zhu Y, et al: Free fatty acids impair

autophagic activity and activate nuclear factor kappa B signaling

and NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome in calf

hepatocytes. J Dairy Sci. 104:11973–1182. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Li Y, Schwabe RF, DeVries-Seimon T, Yao

PM, Gerbod-Giannone MC, Tall AR, Davis RJ, Flavell R, Brenner DA

and Tabas I: Free cholesterol-loaded macrophages are an abundant

source of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6: Model of

NF-kappaB- and map kinase-dependent inflammation in advanced

atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 280:21763–21772. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Cheng J, Montecalvo A and Kane LP:

Regulation of NF-κB induction by TCR/CD28. Immunol Res. 50:113–117.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Di Marzo V: Arachidonic acid and

eicosanoids as targets and effectors in second messenger

interactions. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 53:239–254.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Brien M, Berthiaume L, Rudkowska I, Julien

P and Bilodeau JF: Placental dimethyl acetal fatty acid derivatives

are elevated in preeclampsia. Placenta. 51:82–88. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Bozelli JC Jr, Azher S and Epand RM:

Plasmalogens and chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Physiol.

12:7308292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Brenner RR: Nutritional and hormonal

factors influencing desaturation of essential fatty acids. Prog

Lipid Res. 20:41–47. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Cook HW: The influence of trans-acids on

desaturation and elongation of fatty acids in developing brain.

Lipids. 16:920–926. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Chena X, Lia L, Liua X, Luoa R, Liaob G,

Lia L, Liua J, Chenga J, Lua Y and Chen Y: Oleic acid protects

saturated fatty acid mediated lipotoxicity in hepatocytes and rat

of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Life Sci. 203:291–304. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Sun J, Jin X and Li Y: Current strategies

for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease treatment (Review). Int J Mol

Med. 54:882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Tian C, Huang R and Xiang M: SIRT1:

Harnessing multiple pathways to hinder NAFLD. Pharmacol Res.

203:1071552024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Smith BK, Marcinko K, Desjardins EM, Lally

JS, Ford RJ and Steinberg GR: Treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease: Role of AMPK. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

311:E730–E740. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Liu Q, Liu S, Chen L, Zhao Z, Du S, Dong

Q, Xin Y and Xuan S: Role and effective therapeutic target of gut

microbiota in NAFLD/NASH. Exp Ther Med. 18:1935–1944.

2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Kim SE, Min JS, Lee S, Lee DY and Choi D:

Different effects of menopausal hormone therapy on non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease based on the route of estrogen administration.

Sci Rep. 13:154612023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Keskin M, Hayıroğlu Mİ, Uzun AO, Güvenç

TS, Şahin S and Kozan Ö: Effect of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

on in-hospital and long-term outcomes in patients with ST-segment

elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 120:1720–1726. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Şaylık F, Çınar T and Hayıroğlu Mİ: Effect

of the obesity paradox on mortality in patients with acute coronary

syndrome: A comprehensive meta-analysis of the literature. Balkan

Med J. 40:93–103. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|