Introduction

The cellular prion protein (PrPc) has

been studied for its diverse roles across various biological

systems, such as providing neuroprotection through the regulation

of copper and NMDA receptors, as well as maintaining stem cell

health by influencing Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways (1–6),

with particular emphasis on unraveling its mechanisms of action

within the nervous system (7,8).

Notably, PrPc has been revealed to interact with

amyloid-β peptides in Alzheimer's disease and α-synuclein in

Parkinson's disease (9,10). Furthermore, PrPc can

modulate neuroendocrine signaling pathways, especially pathways

that are associated with the regulation of gonadotropin, revealing

a possible role in reproductive physiology (11,12).

PrPc is involved in oocyte maturation (13). Furthermore, in ovariectomized ewes,

the expression of PrPc in ovine uteroplacental tissues

was shown to increase when the ewes were treated with estrogen and

during the early stage of pregnancy (14). However, the roles of

PrPc, including how it regulates ovarian reserve

maintenance and the dynamics of follicular recruitment, have not

been fully elucidated.

Recent advances in reproductive endocrinology

demonstrate the need to clarify the non-steroidogenic mechanisms

that govern follicular homeostasis, with a particular focus on

mechanisms involving anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH)-mediated

signaling (15–17). As AMH levels are closely linked to

ovarian reserve and are recognized as the most sensitive clinical

biomarker for diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) syndromes, it is

crucial to clarify the regulatory mechanisms involved (18,19).

We hypothesized that PrPc may act as a novel type of

modulator for AMH-dependent follicular recruitment, potentially

through mechanisms that are different from the regulation of

classical steroid hormones. To test this hypothesis, two

complementary models were used, the in vitro mouse ovarian

granulosa cells (mGCs) with prion protein gene (PRNP)

knockdown and overexpression (OE) and the in vivo PRNP

knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) models. The specific effects of

PrPc on AMH secretion were compared with those on

progesterone (P4) and estradiol (E2) production. The

present study aimed to analyzed the effects of maintaining the

follicular pool through histomorphometric analysis and reproductive

longevity via litter size tracking, while also examining

neuroendocrine adaptations in the HPG axis using vaginal cytology,

serum FSH quantification, and ovarian reserve evaluation through

follicle counting.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

mGCs were procured from Haixing Biosciences Co.,

Ltd. (cat. no. ORCM050). The cells were grown in high-glucose DMEM

(cat. no. 12,100; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), which included 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin as standard components, with 10% heat-inactivated FBS

(cat. no. FSS500; Shanghai ExCell Biology, Inc.). mGCs were

maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2, and the

culture medium was replaced every 2 days. To preserve physiological

relevance, cell passage was restricted to early generations

(P2-P3), thereby minimizing cellular dedifferentiation.

Additionally, follicle stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR)

expression levels were periodically confirmed by

immunofluorescence, ≥80% of cells exhibited positive FSHR staining

(Fig. S1A).

Immunofluorescence

Cell coverslips were prepared by seeding

1×105 cells in 1 ml of medium and incubating them

overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2 until they reached 70–80%

confluency. After removing the medium, the cells were washed with

ice-cold PBS and fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min

at room temperature. Following additional washes with PBS, the

cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton™ X-100 for 15

min and then blocked with 10% goat serum (cat. no. S9070; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 60 min at room

temperature. The coverslips were then incubated overnight at 4°C

with a rabbit anti-FSHR antibody diluted to 1:200 (cat. no.

22665-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.). After washing, the cells were

stained with an Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated secondary

antibody at a dilution of 1:500 (cat. no. SA00006-2; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) for 2 h at room temperature. Finally, the coverslips

were mounted on slides using DAPI antifade medium (cat. no. S2110;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), and the

samples were imaged for analysis using an inverted platform

(Primovert LED; ZEISS, Germany).

Transfection

Recombinant lentiviruses, rLV-short hairpin

(sh)RNA-Puro-mPRNP and rLV-mPRNP−3flag-ZsGreen-Puro

were procured from Haixing Biosciences Co., Ltd. Empty vectors were

used as negative controls (NCs). The target sequences of the

PRNP shRNAs were as follows: mPRNP sh-1,

5′-GGACAACCTCATGGTGGTAGT-3′; mPRNP sh-2,

5′-GCGTCAATATCACCATCAAGC-3′; and mPRNP sh-3,

5′-GCCTATTACGACGGGAGAAGA-3′. To achieve stable silencing and OE of

the PRNP gene, the cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a

density of 2.5×105 cells per well, and cultured

overnight until they reached a confluence of 40–50%. On the

subsequent day, lentiviral transfection of the cells was performed

following the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. Lentiviral

vectors that encode EGFP reporters were generated using a

third-generation system in 293T cells (cat. no. CL-0005; Wuhan

Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The cells were transfected at

70% confluence with 3 µg pLVX-shRNA2-Puro-mPrnp or

pLVX-mPrnp-3flag-ZsGreen-Puro transfer plasmid, 2 µg of psPAX2, and

1 µg of pMD2.G in a ratio of 3:2:1 using PEI in Opti-MEM. After 48

h of incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2, fluorescence

screening indicated a packaging efficiency of over 85%. To obtain

stably transfected mGCs, lentiviral transduction was performed at

the optimized multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 80, followed by

selection with 3 µg/ml of puromycin for 72 h (cat. no. PS1224;

Beijing Puxitang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), and 1 µg/ml thereafter

for culture maintenance. After 72 h of transduction, the infected

mGCs were collected for subsequent experiments. Stable

PrPc-knockdown mGCs were established through lentiviral

shRNA transduction. Following this, these cells were infected with

a lentivirus designed to overexpress PrPc, allowing for

both the knockdown and overexpression of PrPc within the

same cellular environment.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from mGCs following the

manufacturer's instructions (cat. no. UE-MN-MS-RNA-10; Suzhou

UElandy Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Quantity and purity of RNA were

determined using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer

(Thermo Scientific). The RNA concentrations were measured at A260,

while the purity was evaluated by calculating the A260/A280 ratios.

Subsequently, RT was performed following the manufacturer's

instructions for the RevertAid™ Master Mix (cat. no.

M1632; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). qPCR was carried out on a

CFX Connect fluorescent Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.), using the Universal SYBR Green qPCR Supermix (cat. no.

S2024L; US Everbright, Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were as

follows: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec

and 60°C for 30 sec. The PRNP primer sequences (cat. no.

MQP094390; GeneCopoeia, Inc.) were as follows: PRNP forward

(F), 5′-GGCCCATGATCCATTTTGGC-3′ and reverse (R),

5′-TGCTGTACTGATCCACTGGC-3′. Additionally, the following primer

sequences were used for β-actin (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.,

Ltd.): β-actin F, 5′-GACTTTGTACATTGTTTTG-3′ and R,

5′-TGCACTTTTATTGGTCTCA-3′, which was selected as the internal

control for normalization. The 2−ΔΔCq method was

employed for quantification of the data (20). qPCR was selected for its superior

sensitivity in detecting transcript-level changes (detection

threshold ≤10 copies/µl) compared with conventional PCR (21,22),

with SYBR Green chemistry providing cost-effective quantification

of PRNP expression dynamics.

Western blotting (WB)

mGCs and ovarian tissue were lysed on ice for 30 min

in RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (cat. no.

R0010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The

total protein content was determined using a BCA Protein

Quantification Kit (cat. no. C0050; TargetMol Chemicals Inc.).

Following protein quantification, 25 µg total protein/lane in each

sample were separated via 10% SWE Rapid High Resolution Running

Buffer (cat. no. G2081-1L; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.).

Subsequently, the separated proteins were transferred onto PVDF

membranes (cat. no. IPVH00010; MilliporeSigma).

To block non-specific binding, the PVDF membranes

were incubated in a solution of 5% non-fat dried milk (cat. no.

S10191; Beijing Puxitang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) in Tris-buffered

saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST; cat. no. T1082; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 2 h at room

temperature. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight

at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-CD230 (Prion;

cat. no. 808001; BioLegend, Inc.) and anti-β-actin at a 1:5,000

dilution (cat. no 20536-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.).

After the overnight incubation, the membranes were

washed three times with TBST and incubated for 2 h at room

temperature with the following secondary antibodies: HRP-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit IgG at a 1:1,000 dilution (SA00001-2; Proteintech

Group, Inc.) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG at a 1:10,000

dilution (SA00001-1; Proteintech Group, Inc.).

Finally, an enhanced chemiluminescence detection

reagent (cat. no. S6009L; Suzhou UE Landi Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

was used to visualize the immunoreactive bands on ChemiDoc MP

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Densitometry of the WB bands was

performed using ImageJ 1.48V software (National Institutes of

Health).

Apoptosis assay

Following the instructions of the Annexin V/PI

detection Kit (cat. no. Y6026S; Suzhou UE Landy Biotechnology Co.,

Ltd.), 1×105 mGCs were digested with 0.25%

trypsinization solution (without EDTA)(cat. no. T1350; Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), then enzymatically

neutralized and resuspended in cold staining buffer, then

resuspended in a staining buffer, which was prepared by adding 5 µl

each Annexin V storage solution and 5 µl PI storage solution.

Subsequently, the cells were incubated in the dark at 4°C for 20

min and analyzed using a NovoCyte D3000 flow cytometer (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) Flow cytometry data were analyzed using De Novo

FCS Express™ 6 software (Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Annexin V/PI dual staining was employed to differentiate early

apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI−) from late

apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+)

populations, enabling stage-specific analysis of mGC death

pathways, the total percentage of apoptotic cells reflects the

overall measurement of both early and late apoptotic

populations.

Cell cycle assay

For cell cycle analysis, 5×105 mGCs were

harvested by trypsinization at 72 h post-infection. The cells were

then washed with cold PBS and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol at 4°C

overnight. Next, mGCs were incubated with RNase A and PI in a 0.5

ml reaction mixture (cat. no. C6031S; Suzhou UE Landy Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) at 37°C for 30 min in a dark chamber. Cell cycle

distribution was measured using a NovoCyte D3000 flow cytometer and

analyzed with De Novo FCS Express™ 6 software (Agilent

Technologies, Inc.).

ELISA for hormone measurements

mGC culture medium containing 10% FBS and mouse

serum collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C

were used to measure the concentrations of E2 (cat. no.

SEKM-0286; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.),

AMH (cat. no SEKM-0310; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.), P4 (cat. no. SEKSM-0002; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.), FSH (cat. no. KE1425; ImmunoWay

Biotechnology Company) and luteinizing hormone (LH; cat. no.

KE1421; ImmunoWay Biotechnology Company), following the

manufacturer's instructions.

Animals

A total of 24 mice were used, comprising FVB-PRNP-/-

and FVB wild-type (WT) mice, with each group consisting of 12

females. At the start of the experiment, the mice were 7 weeks old,

and body weight was of 19.1–22.9 g (mean ± SD: 20.82±1.13 g). PRNP

KO mice with an FVB genetic background were provided by Professor

Wen-Quan Zou (Jiangxi Academy of Clinical Medical Sciences of the

First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University) and Professor Li

Cui (Department of Neurology, First Hospital of Jilin University).

FVB WT mice, sourced from GemPharmatech Co. Ltd., were utilized as

controls in the present study. All experimental protocols were

approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)

of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (approval

no. CDYFY-IACUC-202310QR030; Nanchang, China) in accordance with

the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for animal welfare. To

maintain optimal health and experimental integrity, both the KO and

WT mice were housed in individually ventilated cages under specific

pathogen-free (SPF) conditions, maintaining a temperature of 22±1°C

and humidity levels of 55±10%. They were kept on a 12:12-h

light/dark cycle. The animals had unrestricted access to autoclaved

standard rodent chow and reverse-osmosis purified water. These

carefully controlled housing conditions minimized the potential

influence of external pathogens on the experimental outcomes,

ensuring that any observed differences between the KO and WT groups

could be more accurately attributed to the genetic modifications

rather than environmental factors. Breeding pairs were formed by

housing WT and KO female mice (n=6 per group) with proven-fertility

WT males at 10 weeks of age under specific pathogen-free

conditions. After confirming the presence of copulatory plugs,

which indicated successful mating and was designated as Gestational

Day 0, the dams were individually housed in ventilated cages.

Inhalant anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane (cat. no.

R510-22-16; RWD Life Science Co., Ltd.) in oxygen at 1 l/min flow

rate, and maintained for 5 min until the pedal withdrawal reflex

ceased and the respiratory rate stabilized (40–60 breaths/min).

Cervical dislocation was performed with simultaneous isoflurane

overdose to ensure humane euthanasia. Death validation included

confirmation of apnea for >3 min and absence of the corneal

reflex. Terminal whole blood samples (~0.3 ml) were obtained via

retro-orbital venous plexus puncture within 2 min post-mortem to

ensure coagulation integrity. Ovarian tissues were dissected, fixed

in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 24–48 h, then processed for

paraffin embedding and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E)

staining.

H&E staining

H&E staining was performed in accordance with a

standard protocol (23,24). Specifically, ovarian tissues were

fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (w/v in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4) at 4°C for

a duration of 24 to 48 h, 5-µm-thick paraffin sections underwent

three 5-min immersions in xylene. This was followed by a

rehydration process through a graded series of ethanol

concentrations: 100, 95, 80, and 70% (v/v), with each step lasting

2 min, ultimately concluding in distilled water. Next, the sections

were stained with H&E (cat. no. L11021604l; Nanchang Yulu

Experimental Equipment Co., Ltd.). Sections were stained with

Mayer's hematoxylin at room temperature (23±2°C) for a duration of

3 min, and this was followed by staining with eosin Y alcoholic

solution at the same temperature for 2 min. Ovarian follicles were

quantified using systematic random sampling in every sixth serial

section with a thickness of 5 µm. A manual counting method was

employed, examining 30 non-overlapping fields per ovary at a

magnification of 200× using a light microscope (Beijing Sunny

Instruments Co., Ltd.). Follicles were identified across various

stages, from primordial to antral, in accordance with the Amsterdam

Consensus Criteria (25,26).

Estrous cycle staging

Estrous cycle staging was performed through daily

vaginal smear cytology between 9:00-10:00 a.m. Vaginal lavage

samples were obtained using 10 µl sterile PBS, placed onto

poly-L-lysine coated slides, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at

4°C for 15 min. Hematoxylin (3 min) and eosin (30 sec) staining at

room temperature, adhering to standard protocols.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SD based on a

minimum of three independent experiments. Prior to analysis,

normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test (α=0.05) and the

homogeneity of variance was confirmed via Brown-Forsythe test.

Parametric tests were applied when assumptions were satisfied.

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 9.5

software (Dotmatics). For the comparison between two groups, a

two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was used, with Cohen's d

effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals automatically calculated

by the software. For the comparison of >2 groups, one-way ANOVA

with Tukey's post hoc test (for all pairwise comparisons) or

Dunnett's post hoc test (for comparisons vs. the control group) was

applied, with partial η2 effect sizes and family-wise

error rate control at α=0.05. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

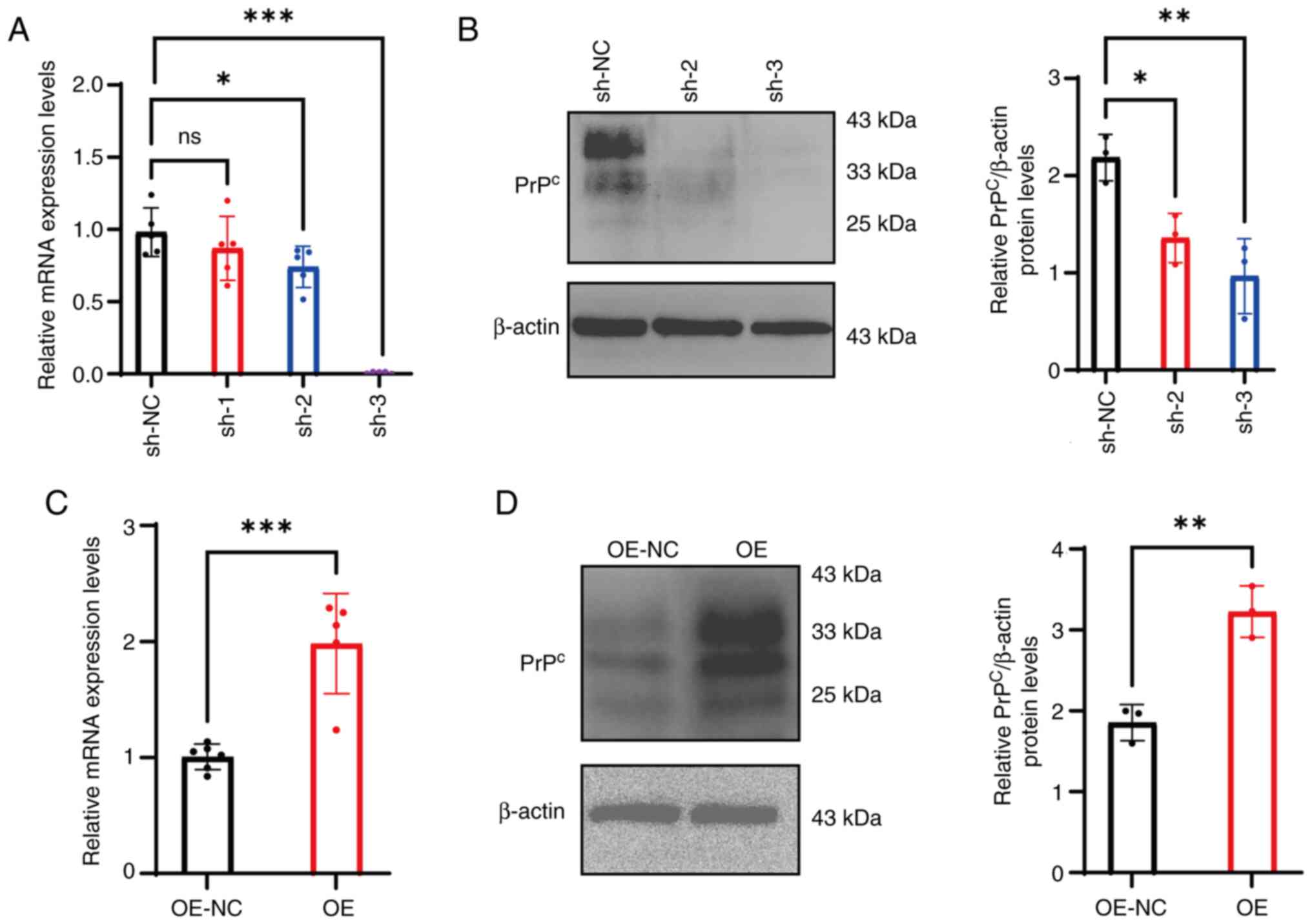

Validation of PrPc

knockdown and OE efficiency

To knock down PrPc in mGCs, the following

lentivirus-based vectors were used: mPRNP sh-1, sh-2 and

sh-3. Compared with those of mGCs infected with the NC vector

(sh-NC), the mRNA expression levels of PRNP in the sh-1

group exhibited no significant change (P>0.05). However,

infections with sh-2 and sh-3 resulted in a marked reduction in

mRNA expression (sh-2:P<0.05; Sh-3:P<0.001), respectively,

confirming successful knockdown of the PRNP gene (Fig. 1A). Supporting these findings, WB

analysis revealed that the gray values of the PrPc

protein bands in cells transfected with sh-2 and sh-3 were

significantly reduced compared with those in the sh-NC group

(P<0.05; Fig. 1B). Based on

these results, sh-2 and sh-3 were selected as the most efficient

shRNAs for subsequent experiments.

In the PrPc OE group, the mRNA expression

levels of PRNP were significantly increased compared with

those in the OE-NC group (P<0.001; Fig. 1C), indicating that the OE vector

effectively increased the transcription of the PRNP gene.

Correspondingly, the expression levels of the PrPc

protein in the OE group was significantly increased compared with

that in the OE-NC group (P<0.01; Fig. 1D), aligning with the observed trend

in mRNA expression levels.

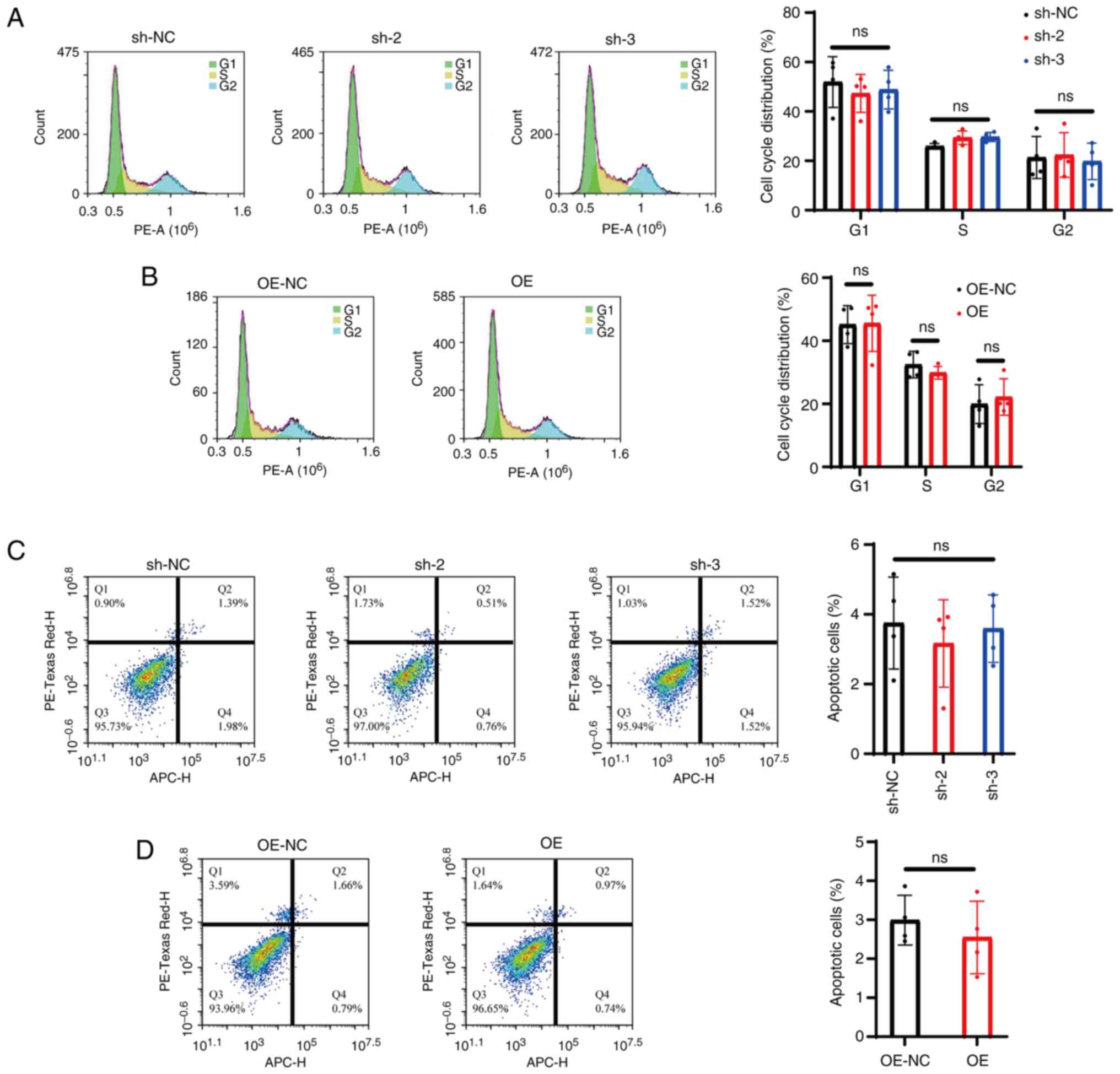

PrPc does not alter mGC

cycle progression or apoptosis

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out to assess

cell cycle distribution in mGCs. The results revealed no

significant differences in the proportions of cells in the

G1, S and G2 phases among the sh-2, sh-3 and

sh-NC groups (P>0.05; Fig. 2A).

Likewise, no notable changes were observed in the distribution of

cells across these phases in the OE group compared with OE-NC

(P>0.05; Fig. 2B).

Analysis of apoptosis using the Annexin V/PI double

staining method by flow cytometry revealed that, under normal

culture conditions, the apoptosis rate of mGCs was consistent

between the sh-NC and OE-NC groups. Moreover, sh-2, sh-3 and sh-NC

did not exhibit any significant differences in the proportion of

apoptotic cells (P<0.05; Fig.

2C). Similarly, the OE group demonstrated no notable variation

in the proportion of apoptotic cells compared with OE-NC

(P<0.05; Fig. 2D).

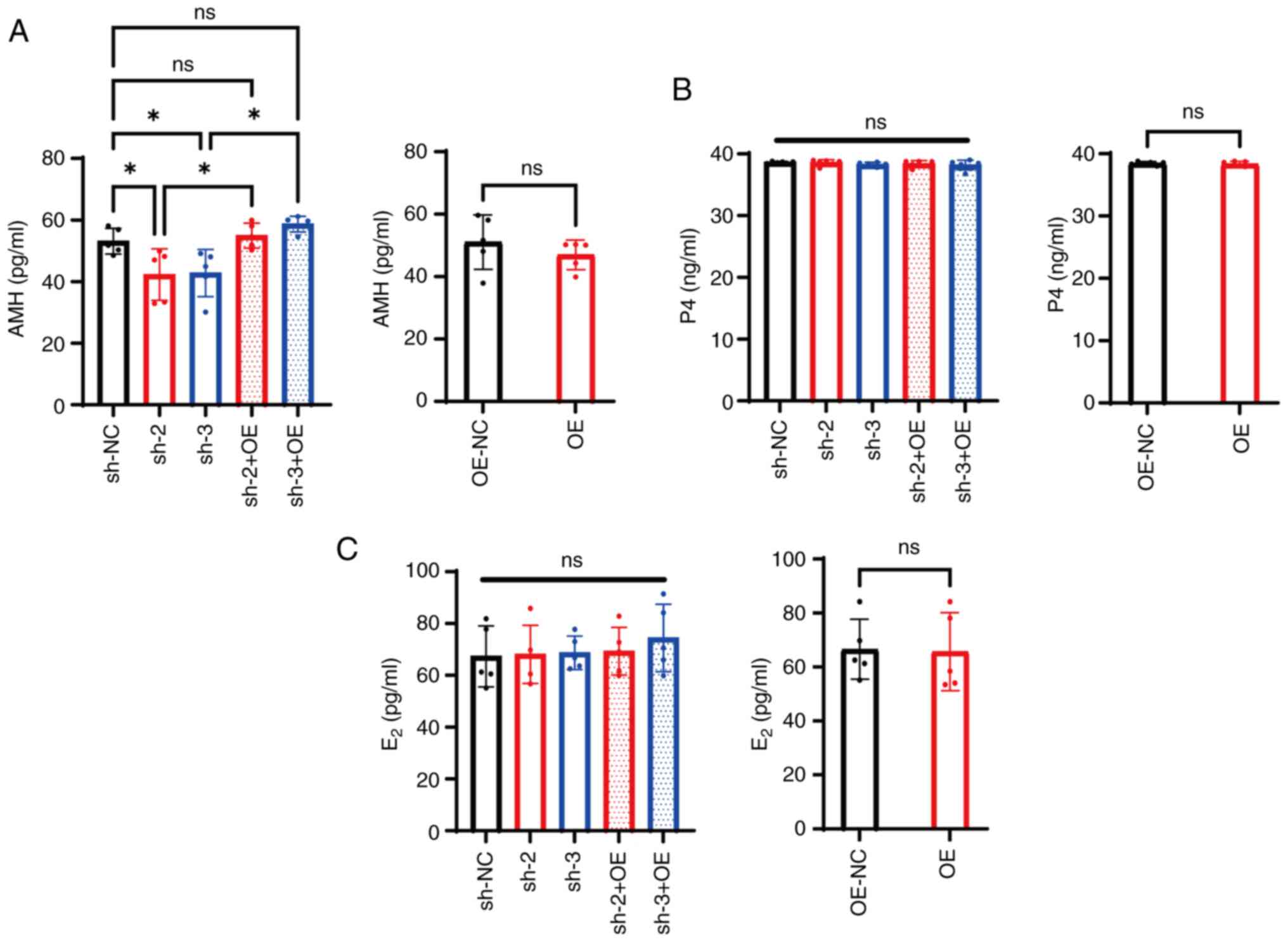

PrPc knockdown reduces AMH

secretion while preserving P4 and E2 production

in mGCs

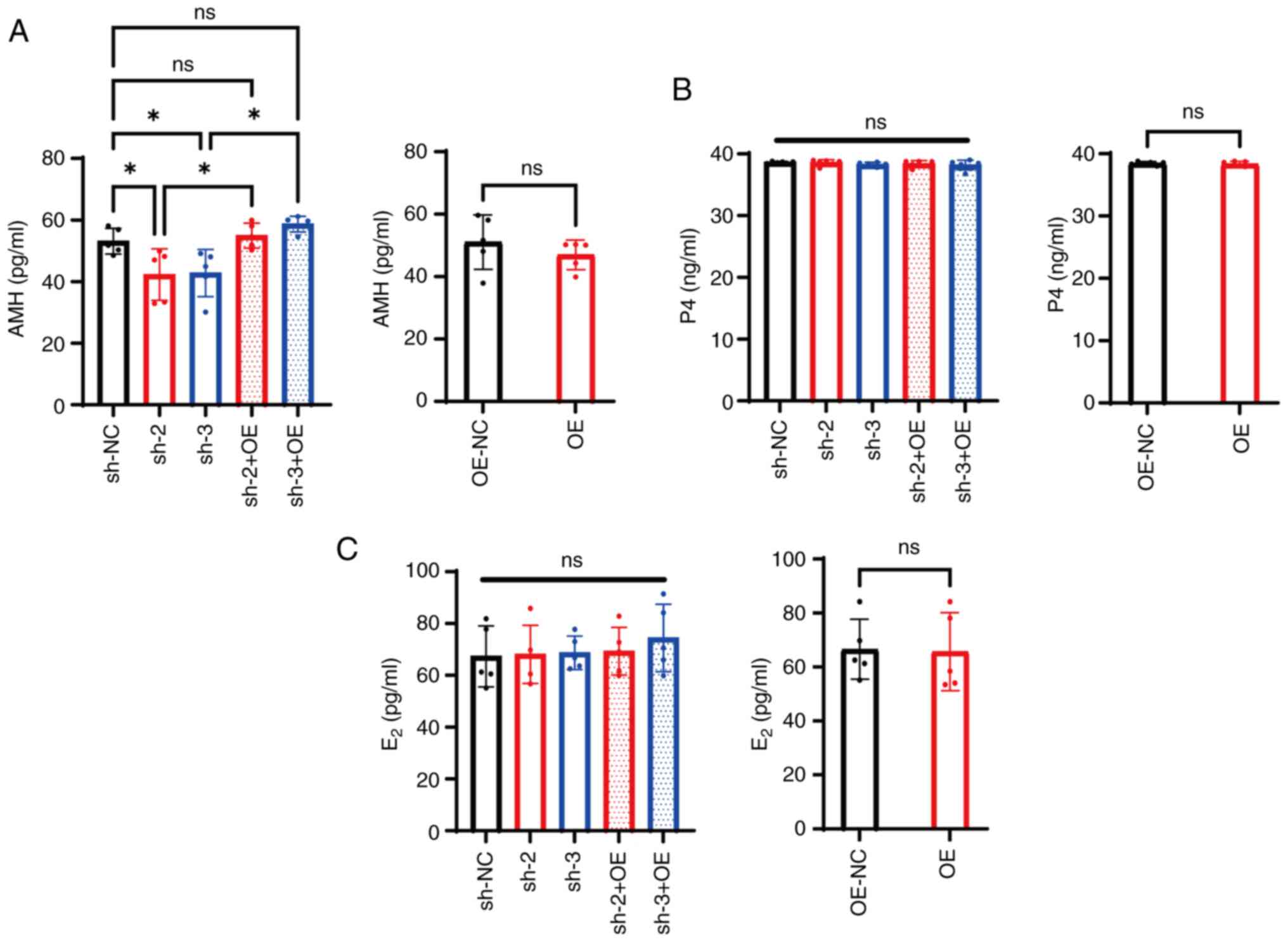

AMH levels averaged 56.10±3.73 ng/ml in the sh-NC

group, while they significantly decreased to 42.27±7.51 and

42.7±6.85 ng/ml in the sh-2 and sh-3 groups respectively

(P<0.05; Fig. 3A). However,

PrPc expression was restored following knockdown in mGCs

infected both with the PRNP knockdown and OE vectors (sh-2 +

OE and sh-3 + OE; Fig. S1B), and

AMH levels increased compared with those in the sh-2 and sh-3

groups (P<0.05; Fig. 3A). By

contrast, the average AMH expression levels in the OE group was

46.96±4.22 ng/ml, exhibiting no significant difference compared

with that in the OE-NC group (P>0.05; Fig. 3A).

| Figure 3.Cellular prion protein knockdown

specifically reduces AMH secretion in mGCs. (A) AMH, (B) P4 and (C)

E2 levels in the culture medium of mGCs transfected with

different shRNAs, OE vectors or their combination. *P<0.05. ns,

non-significant; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; mGCs, mouse granulosa

cells; P4, progesterone; E2, estradiol; sh, short

hairpin; OE, overexpression; NC, negative control. |

The average P4 level was 38.61±0.15 ng/ml in the

sh-NC group, and 38.57±0.43 and 38.24±0.37 ng/ml in the sh-2 and

sh-3 groups, respectively, with the latter showing no significant

difference compared with the control group (P>0.05; Fig. 3B). Furthermore, compared with the

sh-2 and sh-3 groups, the sh-2 + OE and sh-3 + OE groups did not

exhibit significant changes in P4 levels (P>0.05; Fig. 3B). Similarly, the average P4 level

in the OE group was 38.33±0.40 ng/ml, which was comparable with

that in the OE-NC group (P>0.05; Fig. 3B).

The average E2 level in the sh-NC group

was 67.33±10.54 pg/ml, while the sh-2 and sh-3 groups exhibited

values of 68.11±10.07 and 68.74±5.81 pg/ml, respectively, both

showing no significant differences compared with sh-NC (P>0.05;

Fig. 3C). Similarly, compared with

the sh-2 and sh-3 groups, no notable changes in E2

expression levels were observed in the sh-2 + OE and sh-3 + OE

groups (P>0.05; Fig. 3C).

Likewise, the average E2 level in the OE group was

65.67±11.67 pg/ml, which was not significantly different compared

with that in the OE-NC group (P>0.05; Fig. 3C).

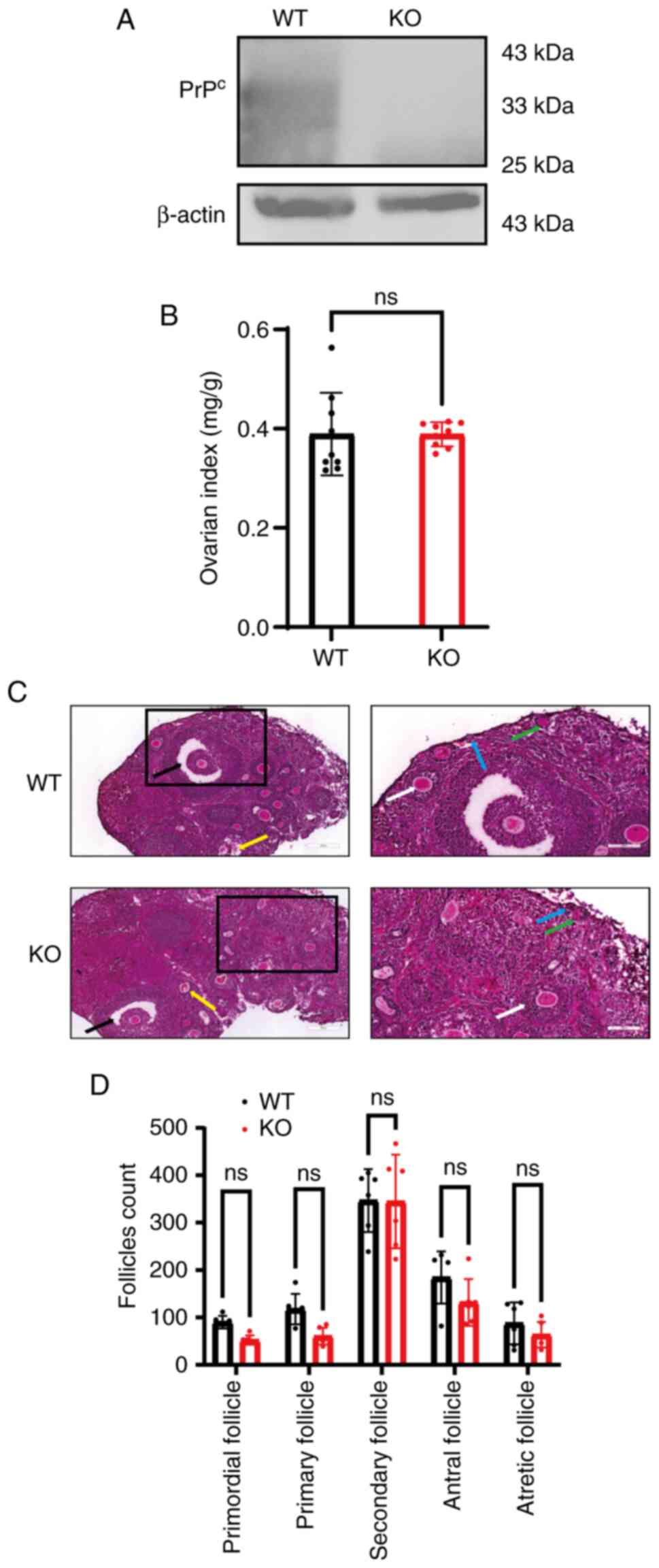

PrPc expression levels do

not affect the classification count of ovaries

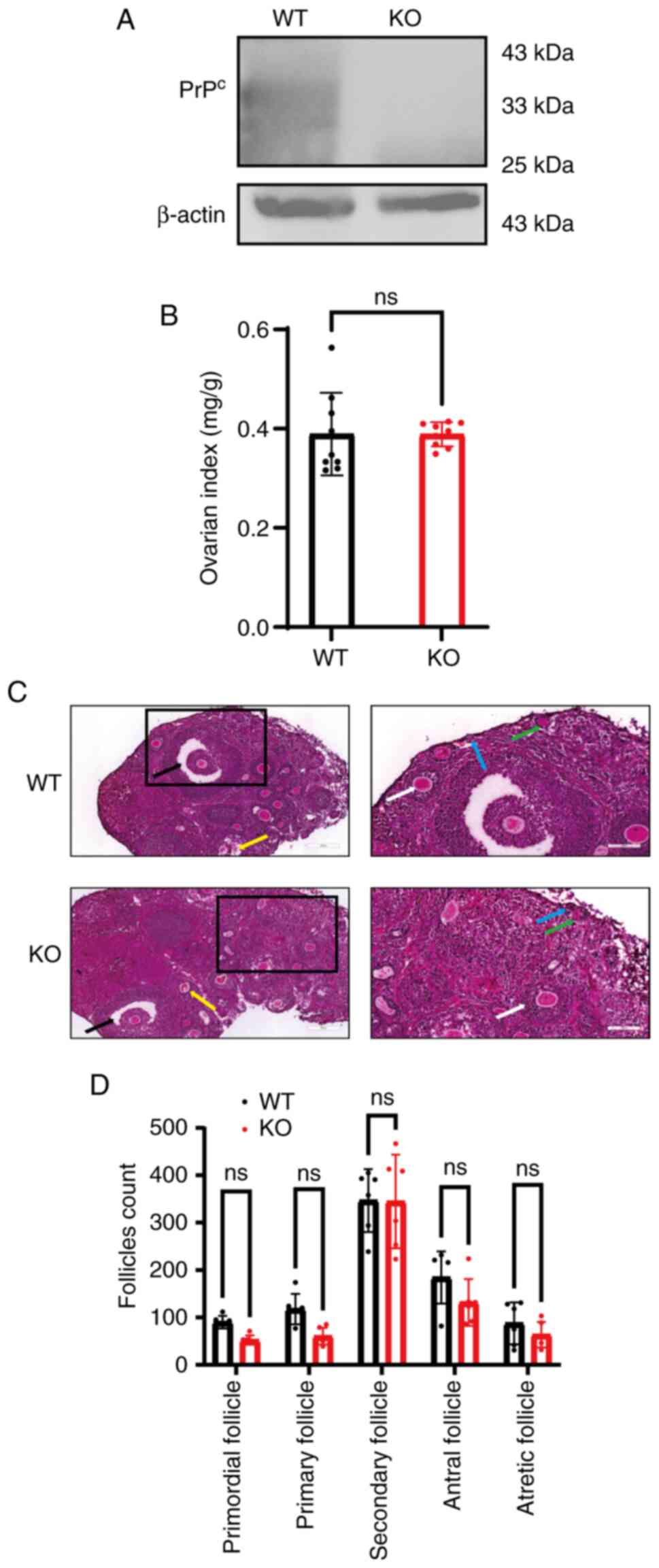

Ovaries from WT and KO mice were isolated and WB was

carried out to assess PrPc protein expression levels.

The results indicated that PrPc levels in the ovaries of

KO mice were reduced compared with those in the WT group (Fig. 4A) confirming the effectiveness of

the KO.

| Figure 4.Prion protein gene KO mice exhibit

normal ovarian morphology and follicular development. (A)

PrPc protein expression in the ovaries of WT and KO

mice. (B) Ratio of bilateral ovary weight to body weight showed no

differences between groups. (C) H&E staining on mouse ovaries

(scale bars, 200 µm for overviews and 100 µm for higher mag). The

stages of follicular development are clearly indicated by

color-coded arrows: Blue represents primordial follicles, which

consist of a single layer of squamous granulosa cells; green

denotes primary follicles, characterized by cuboidal granulosa

cells; white signifies secondary follicles, identifiable by having

≥3 layers of granulosa cells and the early formation of an antrum;

black marks antral follicles, distinguished by the presence of a

fluid-filled cavity; and yellow indicates atretic follicles, which

display pyknotic granulosa cell nuclei and fragmentation of the

zona pellucida. (D) Follicle counts across developmental stages

were comparable between WT and KO mice. ns, non-significant; WT,

wild-type; KO, knockout; PrPc, cellular prion

protein. |

At 7 weeks of age, ovarian tissue was collected, and

the wet weight index of ovaries was measured. The WT group had an

ovarian weight of 0.390±0.08 mg/g, while the KO group exhibited a

weight of 0.389±0.02 mg/g, with no statistically significant

difference between the groups (P>0.05; Fig. 4B).

H&E staining revealed the pathological and

morphological characteristics of the ovaries in each group

(Fig. 4C). Although the KO group

exhibited a slight reduction in the number of primordial and

primary follicles, this difference was not statistically

significant (P>0.05; Fig. 4D).

Similarly, there were no significant differences in the numbers of

secondary, antral or atretic follicles between the two groups

(P>0.05; Fig. 4D).

PRNP deficiency elevates circulating

FSH levels with unaltered AMH, LH and E2 levels

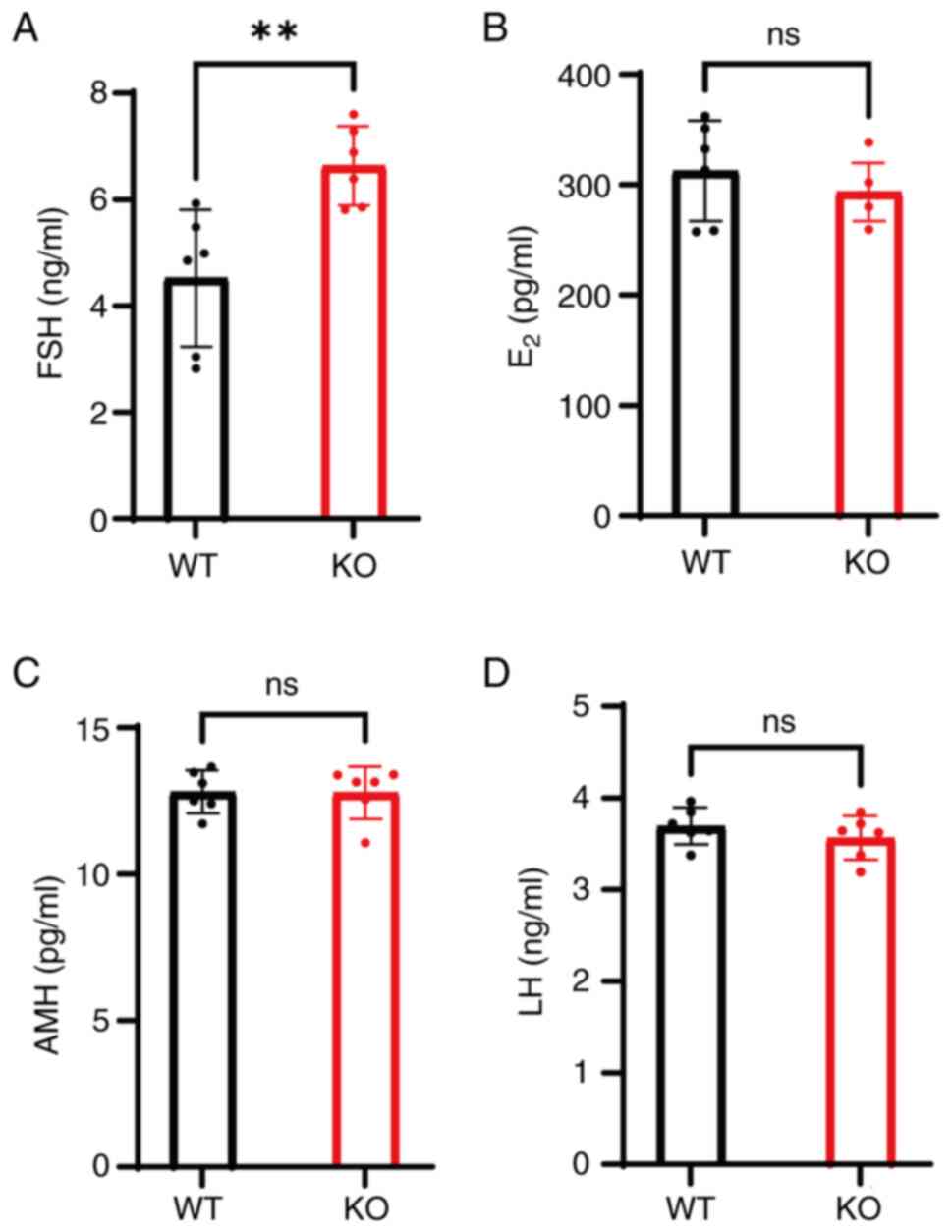

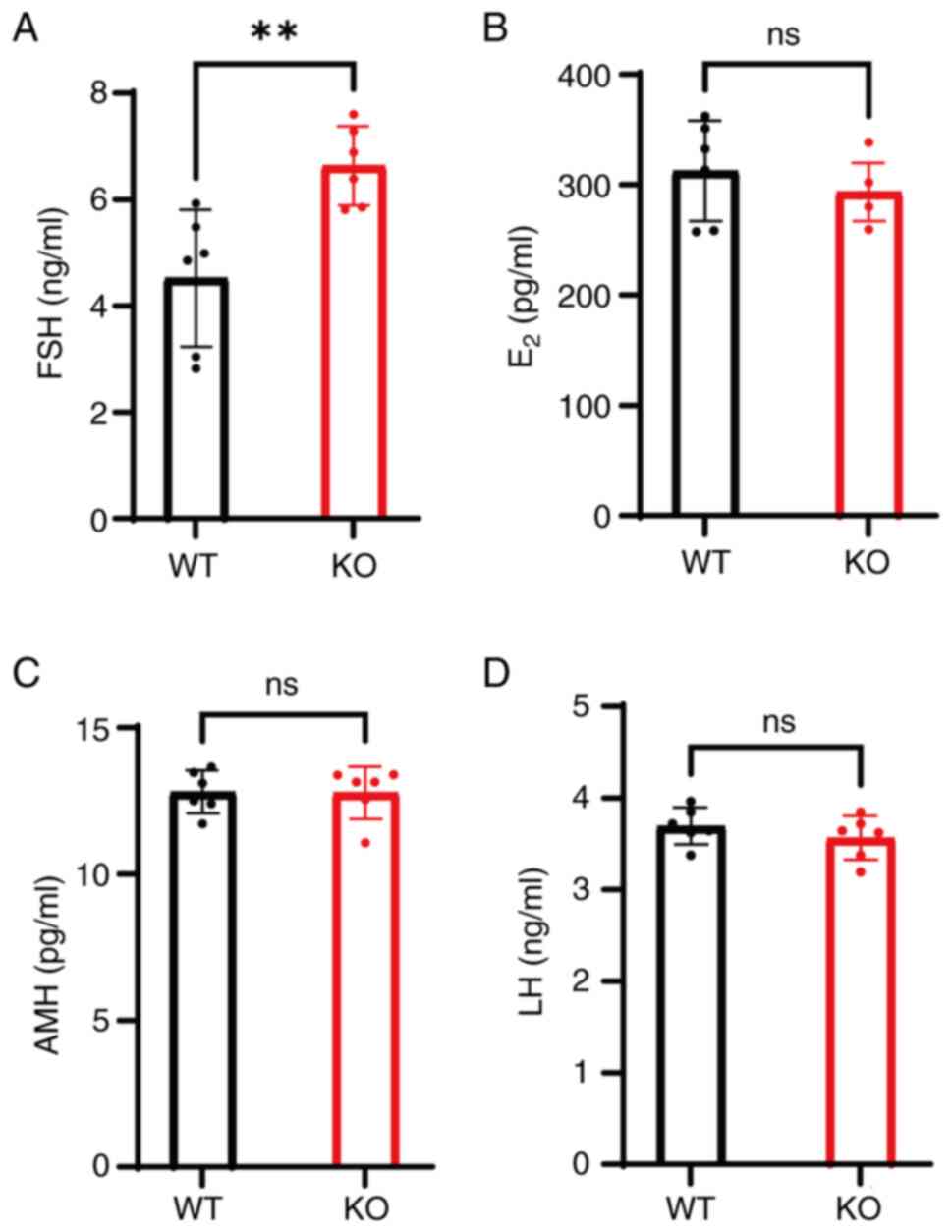

FSH levels in KO mice were significantly increased

at 6.64±0.68 ng/ml compared with 4.52±1.18 ng/ml in the WT group

(P<0.01; Fig. 5A). By contrast,

E2 levels were not significantly different between the

two groups (P>0.05; Fig. 5B).

Similarly, AMH and LH levels were also not significantly different

between WT and KO mice (P>0.05; Fig. 5C and D).

| Figure 5.KO mice exhibit elevated FSH levels

but normal E2, AMH and LH levels. Serum hormone levels

of (A) FSH, (B) E2, (C) AMH and (D) LH in WT and KO

mice. **P<0.01. ns, non-significant; FSH, follicle-stimulating

hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; E2, estradiol; AMH,

anti-Müllerian hormone; WT, wild-type; KO, knockout. |

PRNP KO mice exhibit normal

reproductive performance

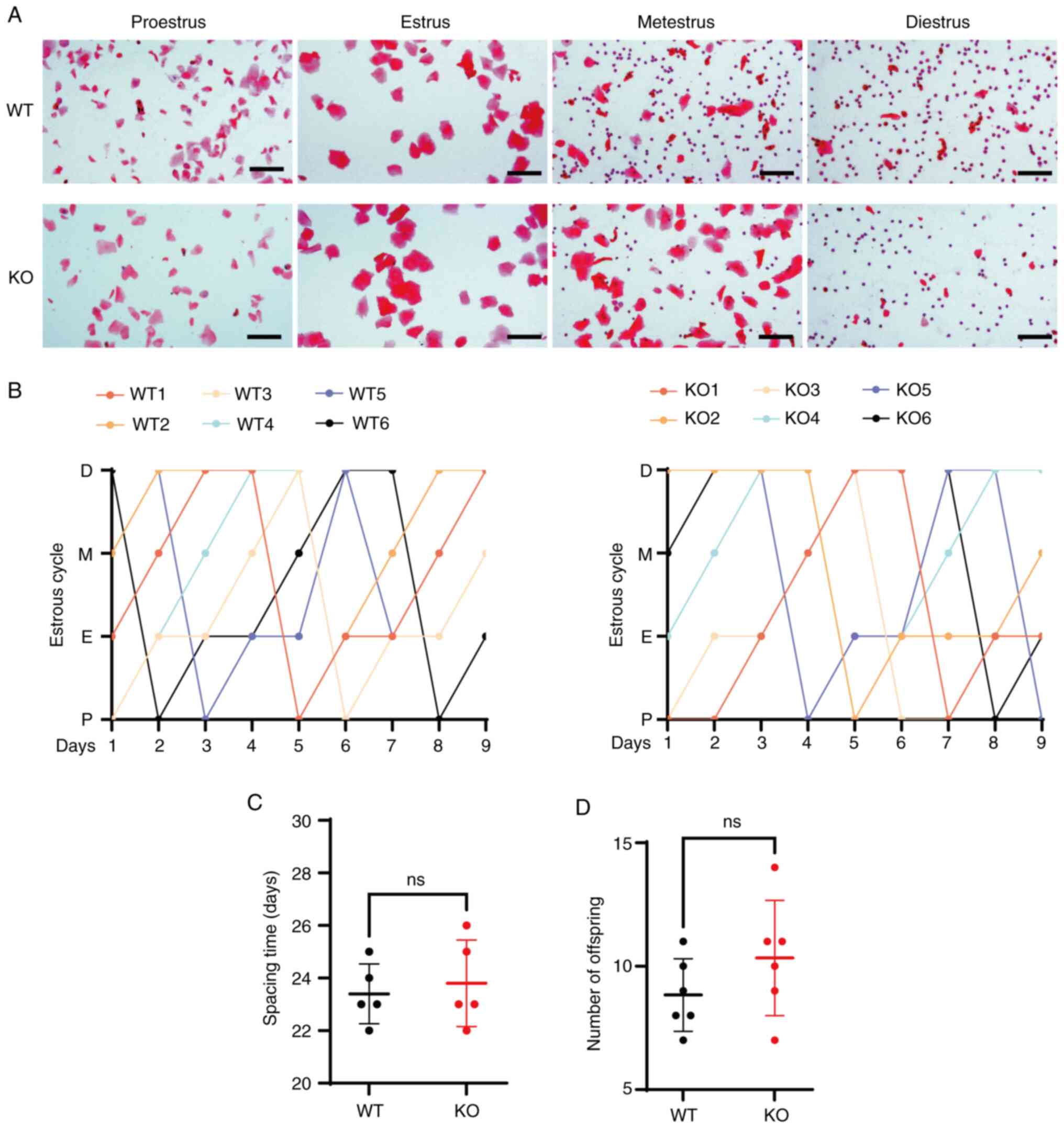

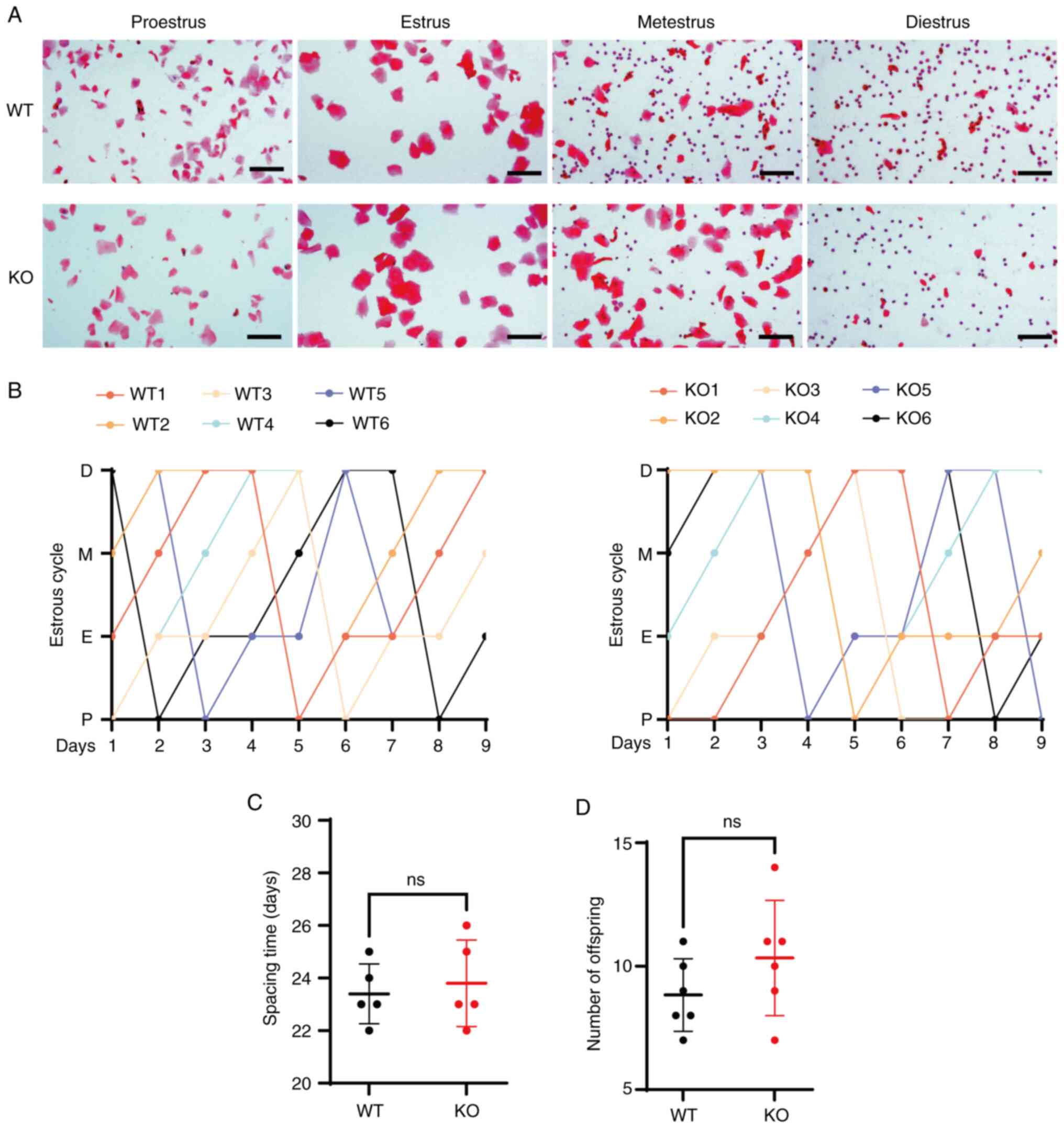

WT and KO mice exhibited a standard estrous cycle,

typically spanning 4–5 days per cycle and encompassing four

distinct phases: Proestrus, estrus, metestrus and diestrus

(Fig. 6A). In the proestrus stage

(P), the smears are primarily made up of nucleated epithelial

cells, which are characterized by their polygonal shape, large

spherical nuclei, and abundant cytoplasm. As the cycle progresses

to estrus (E), there is a notable increase in keratinized

epithelial cells, which display a distinct eosinophilic staining in

their cytoplasm. This is followed by metestrus (M), where the

number of keratinized cells begins to decline, and nucleated

epithelial cells become more present, accompanied by a few clusters

of leukocytes. Finally, in the diestrus stage, the cytological

composition shifts to predominantly leukocytes, with few scattered

nucleated epithelial cells present (27). Each stage in the WT mice was

clearly defined, with smooth and consistent transitions between

phases. Similarly, KO mice exhibited no notable alterations in

cycle duration, with neither a marked prolongation nor a noticeable

shortening of the cycle observed (Fig.

6B).

| Figure 6.KO mice exhibit regular estrous cycle

and fertility. (A) Vaginal secretion smears stained with H&E

stain during estrous cycle phases: Proestrus, estrus, metestrus,

diestrus (scale bar, 50 µm). (B) Regular estrous cycle patterns in

mice spanning 9 consecutive days. (C) Interval from mating,

following co-housing, to parturition. (D) Number of offspring at

birth. ns, non-significant; WT, wild-type; KO, knockout; P,

proestrus; E, estrus; M, metestrus; D, diestrus. |

No statistically significant differences were

observed in the litter intervals between the two groups (P>0.05;

Fig. 6C). The average litter size

remained consistent at 8–10 pups, and the mothers exhibited normal

nurturing abilities. The offspring survival rate was high, with no

notable differences detected between the groups (P>0.05;

Fig. 6D).

Discussion

Previous studies have predominantly explored the

role of PrPc within the nervous system (28–31).

However, there is little research on the function of

PrPc in non-neuronal tissues, especially in endocrine

regulation. The present in vitro study revealed that

PrPc can selectively affect the secretion of AMH, while

no significant changes in AMH, P4, E2, folliculogenesis

and the reproductive cyclicity in mice. These findings broaden the

functional range of PrPc beyond its typical roles in

neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity (32,33),

indicating that PrPc may be a potential niche regulator

of ovarian reserve biomarkers.

The present study revealed that alterations in the

expression of PrPc in mGCs did not significantly

influence the cell cycle or apoptosis, suggesting that

PrPc may not regulate cellular homeostasis in mGCs.

PrPc may not directly affect the signaling molecules

involved in key cell cycle transitions, such as those between the

G1/S and G2/M phases. However, its role

varies significantly in other systems. In neural environments,

PrPc acts as an accelerator of apoptosis during

proteotoxic stress by impairing the ESCRT-0/AMPAR axis. In renal

settings, it promotes regeneration through the activation of the

PI3K/Akt-mTOR pathway. In cardiac contexts, PrPc is

crucial for structural recovery, although it does not influence

functional recovery. Additionally, in oncogenic environments, it

serves as a key regulator of cell fate by modulating the dynamics

between p53 and MDM2 during endoplasmic reticulum stress (34–36).

Additionally, a previous study has highlighted the presence of

compensatory mechanisms among members of the prion protein family,

particularly PrPc and Shadoo, which aid in maintaining

cell cycle progression and suppressing apoptosis (37).

The levels of AMH, which is considered a marker of

the ovarian reserve function and is primarily secreted by GCs

(15), were decreased when

PrPc was knocked down. The effect of PrPc

knockdown may be associated with disrupted TGF-β/bone morphogenetic

protein (BMP)-SMAD superfamily signaling pathways (38). AMH transcription is strictly

controlled by SMAD1/5/8 complexes, which are activated by BMP

ligands (39). The present

findings are consistent with mechanistic framework proposed by Puig

et al (40), which suggests

that PrPc plays a role in modulating the trafficking of

FSHR and bone morphogenetic protein receptors (BMPR-II). Regarding

the secretion of P4 and E2, no significant changes were

observed after PrPc knockdown or overexpression, and the

AMH-specific effect contrasts those of classical steroidogenic

regulators, such as PPAR-γ agonists, miR-335-5p, retinoic acid, and

artemisinins, which alter multiple hormonal axes (41–44).

It may be hypothesized that PrPc stabilizes BMP receptor

clusters on GCs, which activates SMAD phosphorylation and

subsequent AMH synthesis. This hypothesis can be tested by mapping

the interactions between PrPc and BMP receptor 2 and by

quantifying the levels of phosphorylated-SMAD1/5 in PrPc

knockdown models.

The results of the present study indicating that

PrPc is dispensable for murine ovarian function

contrasts with its reported roles in neuronal survival,

underscoring profound tissue specificity (45). Although PrPc deletion in

neurons induces apoptosis via Bcl-2 suppression, GCs may remain

viable after PrPc depletion through compensatory

mechanisms involving the Shadoo protein (46).

Despite minor changes, no statistically significant

differences were observed in the ovary weight and the numbers of

primordial and primary follicles in the PrPc KO mice

compared with the WT group. Furthermore, there seemed to be no

evident changes in the estrous cycle, litter interval or the number

of pups per litter between the two groups. This suggests that

PrPc may not be critical in maintaining the structure

and reproductive activity of the ovaries. Vigorous compensatory

mechanisms in the organism may have abolished the effect of

PrPc deficiency on ovarian function.

Furthermore, the lack of PrPc does not

seem to interfere with the estrous cycle or the reproductive

functions, potentially because the hormonal regulatory pathways

within the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis maintain normal

reproductive rhythms and functions (47). Nonetheless, it cannot be ruled out

that, under chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage or under

hyperandrogenic conditions mimicking polycystic ovary syndrome

(PCOS), PrPc may have a key impact on reproductive

functions.

The mouse model used in the present study may not

capture all the physiological and pathological intricacies of the

human ovary. There are marked differences in the structural,

functional and hormonal regulation, as well as the reproductive

cycle between mouse and human ovaries. For example,

folliculogenesis in humans is a process that spans 90 to 120 days,

which is significantly longer than the 14 to 21-day cycle observed

in mice. In humans, primordial follicles can remain dormant for

several decades, a situation that can contribute to oxidative

stress within the ovarian environment. Additionally, humans

typically exhibit a single-wave, monovulatory pattern for the

selection of the dominant follicle, in contrast to mice, which

display multi-wave, polyovulatory cycles (48). In addition, there is an apparent

limitation to the in vitro cell culture model used in the

present study, since cultured cells may lose some of their

physiological characteristics (49,50)

and be affected by microenvironmental conditions (51,52),

which may result in findings that do not represent the in

vivo settings. Murine ovaries lack the protracted

folliculogenesis and hormonal complexity of humans. Furthermore,

environmental endocrine disruptors such as phthalates (53), which potently alter human AMH

levels, were not examined in the present study.

PRNP KO mice seem to have phenotypic

resilience, but this does not entirely invalidate their clinical

relevance. Under stress, there can be a compensatory failure and

PrPc may have a key effect on ovarian function. In mice,

Shadoo-mediated compensatory mechanisms may take place (54), whilst in humans these mechanisms

may not occur. When humans face prolonged oxidative stress, for

example during chemotherapy or when there is age-related follicular

depletion, Shadoo-mediated redundancy may not be sufficient. The

observation of elevated (FSH) levels in PRNP knockout (KO) mice

aligns with the clinical characteristic of increased

early-follicular phase FSH levels seen in patients diagnosed with

diminished ovarian reserve (DOR), as defined by established

international diagnostic criteria (55). Additionally, PrPc

expression in human follicular fluid may be associated with AMH

levels or in vitro fertilization outcomes; therefore, cohort

studies examining the association between PrPc

concentrations in human follicular fluid and key reproductive

parameters is warranted are warranted.

The anti-apoptotic role of PrPc in glioma

cells via interaction with PRKC Apoptosis WT1 Regulator (PAWR)

raises the possibility that PrPc may protect GCs from

chemotherapy-specific observations in glioma models (56). This hypothesis aligns with clinical

observations that the ovarian reserve declines post-chemotherapy

(57–59), it was hypothesized that

PrPc expression critically regulates

chemotherapy-induced ovarian reserve depletion by modulating

granulosa cell survival pathways. Inhibiting PrPc-PAWR

interactions may sensitize ovarian cancer cells to chemotherapy

while preserving normal ovarian tissue. Conversely, enhancing

PrPc activity could protect ovarian follicles during

oncotherapy.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that

PrPc selectively disrupted AMH secretion in mGCs without

affecting the levels of P4 and E2 or the reproductive

cycle. Unlike its anti-apoptotic roles in neurons or glioma, the

role of PrPc in AMH regulation was independent of cell

survival. It was hypothesized that: Murine ovaries may exhibit

compensatory mechanisms via Shadoo in the absence of

PrPc, while human cells exposed to prolonged stress,

such as chemotherapy, may rely more on PrPc for the

regulation of AMH levels and cell survival. Clinically,

PrPc could refine ovarian reserve diagnostics or inspire

fertility preservation strategies. Furthermore, targeting the

PrPc-BMP-SMAD interactions may also address AMH

dysregulation in polycystic ovary syndrome or ovarian

insufficiency.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Wen-Quan

Zou (Jiangxi Academy of Clinical Medical Sciences of the First

Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanching, China), for

technical discussion. The authors would also like to thank

Professor Li Cui (Department of Neurology, First Hospital of Jilin

University, Changchun. China) for their donation of FVB-PRNP

tm1/ILAS congenic mice.

Funding

The present study was partially supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82260295).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CT interpreted data and revised the manuscript. QC

and HW, who made contributions to the study's conceptualization and

data validation. In vivo investigations, including surgical

procedures and H&E staining, were carried out by QC, JH, and

YW. QC, FL, TD and XY performed experiments. QY contributed to

pathological assessments and the drafting of the manuscript. QC and

HW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors

participated in data analysis, manuscript review and they

collectively assume accountability for the published work. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The experimental procedures in the present study

were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of

The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (approval no.

CDYFY-IACUC-202310QR030; Nanchang, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ermonval M, Petit D, Le Duc A, Kellermann

O and Gallet PF: Glycosylation-related genes are variably expressed

depending on the differentiation state of a bioaminergic neuronal

cell line: Implication for the cellular prion protein. Glycoconj J.

26:477–493. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hu W, Nessler S, Hemmer B, Eagar TN, Kane

LP, Leliveld SR, Müller-Schiffmann A, Gocke AR, Lovett-Racke A, Ben

LH, et al: Pharmacological prion protein silencing accelerates

central nervous system autoimmune disease via T cell receptor

signalling. Brain. 133:375–388. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Wulf MA, Senatore A and Aguzzi A: The

biological function of the cellular prion protein: An update. BMC

Biol. 15:342017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Watts JC, Bourkas MEC and Arshad H: The

function of the cellular prion protein in health and disease. Acta

Neuropathol. 135:159–178. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sigurdson CJ, Bartz JC and Glatzel M:

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of prion disease. Annu Rev

Pathol. 14:497–516. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ribes JM, Patel MP, Halim HA, Berretta A,

Tooze SA and Klöhn PC: Prion protein conversion at two distinct

cellular sites precedes fibrillisation. Nat Commun. 14:83542023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Salvesen Ø, Tatzelt J and Tranulis MA: The

prion protein in neuroimmune crosstalk. Neurochem Int.

130:1043352019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dematteis G, Restelli E, Vanella VV,

Manfredi M, Marengo E, Corazzari M, Genazzani AA, Chiesa R, Lim D

and Tapella L: Calcineurin controls cellular prion protein

expression in mouse astrocytes. Cells. 11:6092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Goedert M: NEURODEGENERATION. Alzheimer's

and Parkinson's diseases: The prion concept in relation to

assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Science. 349:12555552015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Stoner A, Fu L, Nicholson L, Zheng C,

Toyonaga T, Spurrier J, Laird W, Cai Z and Strittmatter SM:

Neuronal transcriptome, tau and synapse loss in Alzheimer's

knock-in mice require prion protein. Alzheimers Res Ther.

15:2012023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Evoniuk JM, Johnson ML, Borowicz PP, Caton

JS, Vonnahme KA, Reynolds LP, Taylor JB, Stoltenow CL, O'Rourke KI

and Redmer DA: Effects of nutrition and genotype on prion protein

(PrPC) gene expression in the fetal and maternal sheep placenta.

Placenta. 29:422–428. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Moldenhauer LM, Jin M, Wilson JJ, Green

ES, Sharkey DJ, Salkeld MD, Bristow TC, Hull ML, Dekker GA and

Robertson SA: Regulatory T cell proportion and phenotype are

altered in women using oral contraception. Endocrinology.

163:bqac0982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Memon S, Li G, Xiong H, Wang L, Liu XY,

Yuan M, Deng W and Xi D: Deletion/insertion polymorphisms of the

prion protein gene (PRNP) in gayal (Bos frontalis). J Genet.

97:1131–1138. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Johnson ML, Grazul-Bilska AT, Reynolds LP

and Redmer DA: Prion (PrPC) expression in ovine uteroplacental

tissues increases after estrogen treatment of ovariectomized ewes

and during early pregnancy. Reproduction. 148:1–10. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Buratini J, Dellaqua TT, Dal Canto M, La

Marca A, Carone D, Mignini Renzini M and Webb R: The putative roles

of FSH and AMH in the regulation of oocyte developmental

competence: From fertility prognosis to mechanisms underlying

age-related subfertility. Hum Reprod Update. 28:232–254. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Suarez-Henriques P, Miranda E,

Silva-Chaves C, Cardoso-Leite R, Guilermo-Ferreira R, Katiki LM and

Louvandini H: Exploring AMH levels, homeostasis parameters, and

ovarian primordial follicle activation in pubertal infected sheep

on a high-protein diet. Res Vet Sci. 169:1051582024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Smith ER, Ye D, Luo S, Xu IRL and Xu XX:

AMH regulates a mosaic population of AMHR2-positive cells in the

ovarian surface epithelium. J Biol Chem. 300:1078972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Xiang Y, Jiang L, Gou J, Sun Y, Zhang D,

Xin X, Song Z and Huang J: Chronic unpredictable mild

stress-induced mouse ovarian insufficiency by interrupting lipid

homeostasis in the ovary. Front Cell Dev Biol. 10:9336742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Rios JS, Greenwood EA, Pavone MEG, Cedars

MI, Legro RS, Diamond MP, Santoro N, Sun F, Robinson RD, Christman

G, et al: Associations between anti-mullerian hormone and

cardiometabolic health in reproductive age women are explained by

body mass index. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 105:e555–e563. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Remans T, Keunen E, Bex GJ, Smeets K,

Vangronsveld J and Cuypers A: Reliable gene expression analysis by

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR: Reporting and minimizing

the uncertainty in data accuracy. Plant Cell. 26:3829–3837. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hatakeyama D, Chikamoto N, Fujimoto K,

Kitahashi T and Ito E: Comparison between relative and absolute

quantitative real-time PCR applied to single-cell analyses:

Transcriptional levels in a key neuron for long-term memory in the

pond snail. PLoS One. 17:e02790172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Salido J, Vallez N, González-López L,

Deniz O and Bueno G: Comparison of deep learning models for digital

H&E staining from unpaired label-free multispectral microscopy

images. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 235:1075282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Asaf MZ, Salam AA, Khan S, Musolff N,

Akram MU and Rao B: E-Staining DermaRepo: H&E whole slide image

staining dataset. Data Brief. 57:1109972024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Egbert JR, Fahey PG, Reimer J, Owen CM,

Evsikov AV, Nikolaev VO, Griesbeck O, Ray RS, Tolias AS and Jaffe

LA: Follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone increase

Ca2+ in the granulosa cells of mouse ovarian follicles†. Biol

Reprod. 101:433–444. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim SJ, Kim TE and Jee BC: Impact of

imatinib administration on the mouse ovarian follicle count and

levels of intra-ovarian proteins related to follicular quality.

Clin Exp Reprod Med. 49:93–100. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wall EG, Desai R, Khant Aung Z, Yeo SH,

Grattan DR, Handelsman DJ and Herbison AE: Unexpected plasma

gonadal steroid and prolactin levels across the mouse estrous

cycle. Endocrinology. 164:bqad0702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Abrams J, Arhar T, Mok SA, Taylor IR,

Kampmann M and Gestwicki JE: Functional genomics screen identifies

proteostasis targets that modulate prion protein (PrP) stability.

Cell Stress Chaperones. 26:443–452. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Schmitt-Ulms G, Mehrabian M, Williams D

and Ehsani S: The IDIP framework for assessing protein function and

its application to the prion protein. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc.

96:1907–1932. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Sawaya MR, Hughes MP, Rodriguez JA, Riek R

and Eisenberg DS: The expanding amyloid family: Structure,

stability, function, and pathogenesis. Cell. 184:4857–4873. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Lawrence JA, Aguilar-Calvo P, Ojeda-Juárez

D, Khuu H, Soldau K, Pizzo DP, Wang J, Malik A, Shay TF, Sullivan

EE, et al: Diminished neuronal ESCRT-0 function exacerbates AMPA

receptor derangement and accelerates prion-induced

neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 43:3970–3984. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lidón L, Vergara C, Ferrer I, Hernández F,

Ávila J, Del Rio JA and Gavín R: Tau protein as a new regulator of

cellular prion protein transcription. Mol Neurobiol. 57:4170–4186.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ribeiro LW, Pietri M, Ardila-Osorio H,

Baudry A, Boudet-Devaud F, Bizingre C, Arellano-Anaya ZE, Haeberlé

AM, Gadot N, Boland S, et al: Titanium dioxide and carbon black

nanoparticles disrupt neuronal homeostasis via excessive activation

of cellular prion protein signaling. Part Fibre Toxicol. 19:482022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yang CC, Sung PH, Chen KH, Chai HT, Chiang

JY, Ko SF, Lee FY and Yip HK: Valsartan- and melatonin-supported

adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells preserve renal function in

chronic kidney disease rat through upregulation of prion protein

participated in promoting PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling and cell

proliferation. Biomed Pharmacother. 146:1125512022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sheu JJ, Chai HT, Chiang JY, Sung PH, Chen

YL and Yip HK: Cellular prion protein is essential for myocardial

regeneration but not the recovery of left ventricular function from

apical ballooning. Biomedicines. 10:1672022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tuğrul B, Balcan E, Öztel Z, Çöllü F and

Gürcü B: Prion protein-dependent regulation of p53-MDM2 crosstalk

during endoplasmic reticulum stress and doxorubicin treatments

might be essential for cell fate in human breast cancer cell line,

MCF-7. Exp Cell Res. 429:1136562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Pimenta JMBGA, Pires VMR, Nolasco S,

Castelo-Branco P, Marques CC, Apolónio J, Azevedo R, Fernandes MT,

Lopes-da-Costa L, Prates J and Pereira RMLN: Post-transcriptional

silencing of Bos taurus prion family genes and its impact on

granulosa cell steroidogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

598:95–99. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Hart KN, Stocker WA, Nagykery NG, Walton

KL, Harrison CA, Donahoe PK, Pépin D and Thompson TB: Structure of

AMH bound to AMHR2 provides insight into a unique signaling pair in

the TGF-β family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 118:e21048091182021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Spector I, Derech-Haim S, Boustanai I,

Safrai M and Meirow D: Anti-Müllerian hormone signaling in the

ovary involves stromal fibroblasts: A study in humans and mice

provides novel insights into the role of ovarian stroma. Hum

Reprod. 39:2551–2564. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Puig B, Altmeppen HC, Linsenmeier L,

Chakroun K, Wegwitz F, Piontek UK, Tatzelt J, Bate C, Magnus T and

Glatzel M: GPI-anchor signal sequence influences PrPC sorting,

shedding and signalling, and impacts on different pathomechanistic

aspects of prion disease in mice. PLoS Pathog. 15:e10075202019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Suriyakalaa U, Ramachandran R,

Doulathunnisa JA, Aseervatham SB, Sankarganesh D, Kamalakkannan S,

Kadalmani B, Angayarkanni J, Akbarsha MA and Achiraman S:

Upregulation of Cyp19a1 and PPAR-γ in ovarian steroidogenic pathway

by Ficus religiosa: A potential cure for polycystic ovary syndrome.

J Ethnopharmacol. 267:1135402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang S, Liu Y, Wang M, Ponikwicka-Tyszko

D, Ma W, Krentowska A, Kowalska I, Huhtaniemi I, Wolczynski S,

Rahman NA and Li X: Role and mechanism of miR-335-5p in the

pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Transl

Res. 252:64–78. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cai S, Chen M, Xue B, Zhu Z, Wang X, Li J,

Wang H and Zeng X, Qiao S and Zeng X: Retinoic acid enhances

ovarian steroidogenesis by regulating granulosa cell proliferation

and MESP2/STAR/CYP11A1 pathway. J Adv Res. 58:163–173. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liu Y, Jiang JJ, Du SY, Mu LS, Fan JJ, Hu

JC, Ye Y, Ding M, Zhou WY, Yu QH, et al: Artemisinins ameliorate

polycystic ovarian syndrome by mediating LONP1-CYP11A1 interaction.

Science. 384:eadk53822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Doeppner TR, Kaltwasser B, Schlechter J,

Jaschke J, Kilic E, Bähr M, Hermann DM and Weise J: Cellular prion

protein promotes post-ischemic neuronal survival, angioneurogenesis

and enhances neural progenitor cell homing via proteasome

inhibition. Cell Death Dis. 6:e20242015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Passet B, Castille J, Makhzami S, Truchet

S, Vaiman A, Floriot S, Moazami-Goudarzi K, Vilotte M, Gaillard AL,

Helary L, et al: The Prion-like protein Shadoo is involved in mouse

embryonic and mammary development and differentiation. Sci Rep.

10:67652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Lonardo MS, Cacciapuoti N, Guida B, Di

Lorenzo M, Chiurazzi M, Damiano S and Menale C:

Hypothalamic-ovarian axis and adiposity relationship in polycystic

ovary syndrome: Physiopathology and therapeutic options for the

management of metabolic and inflammatory aspects. Curr Obes Rep.

13:51–70. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Telfer EE, Grosbois J, Odey YL, Rosario R

and Anderson RA: Making a good egg: Human oocyte health, aging, and

in vitro development. Physiol Rev. 103:2623–2677. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Park SU, Walsh L and Berkowitz KM:

Mechanisms of ovarian aging. Reproduction. 162:R19–R33. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Amadei G, Handford CE, Qiu C, De Jonghe J,

Greenfeld H, Tran M, Martin BK, Chen DY, Aguilera-Castrejon A,

Hanna JH, et al: Embryo model completes gastrulation to neurulation

and organogenesis. Nature. 610:143–153. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Chap BS, Rayroux N, Grimm AJ, Ghisoni E

and Dangaj Laniti D: Crosstalk of T cells within the ovarian cancer

microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 10:1116–1130. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Schoutrop E, Moyano-Galceran L, Lheureux

S, Mattsson J, Lehti K, Dahlstrand H and Magalhaes I: Molecular,

cellular and systemic aspects of epithelial ovarian cancer and its

tumor microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:207–223. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Mariana M, Castelo-Branco M, Soares AM and

Cairrao E: Phthalates' exposure leads to an increasing concern on

cardiovascular health. J Hazard Mater. 457:1316802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Pepe A, Avolio R, Matassa DS, Esposito F,

Nitsch L, Zurzolo C, Paladino S and Sarnataro D: Regulation of

sub-compartmental targeting and folding properties of the

Prion-like protein Shadoo. Sci Rep. 7:37312017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Steiner AZ, Pritchard D, Stanczyk FZ,

Kesner JS, Meadows JW, Herring AH and Baird DD: Association between

biomarkers of ovarian reserve and infertility among older women of

reproductive age. JAMA. 318:1367–1376. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhuang D, Liu Y, Mao Y, Gao L, Zhang H,

Luan S, Huang F and Li Q: TMZ-induced PrPc/par-4 interaction

promotes the survival of human glioma cells. Int J Cancer.

130:309–318. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Spears N, Lopes F, Stefansdottir A, Rossi

V, De Felici M, Anderson RA and Klinger FG: Ovarian damage from

chemotherapy and current approaches to its protection. Hum Reprod

Update. 25:673–693. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Park HS, Seok J, Cetin E, Ghasroldasht MM,

Liakath Ali F, Mohammed H, Alkelani H and Al-Hendy A: Fertility

protection: A novel approach using pretreatment with mesenchymal

stem cell exosomes to prevent chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage

in a mouse model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 231:111.e1–111.e18. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Guo Y, Xue L, Tang W, Xiong J, Chen D, Dai

Y, Wu C, Wei S, Dai J, Wu M and Wang S: Ovarian microenvironment:

Challenges and opportunities in protecting against

chemotherapy-associated ovarian damage. Hum Reprod Update.

30:614–647. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|