Introduction

Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription

factor II [COUP-TFII; also known as nuclear receptor subfamily 2

group F member 2 (NR2F2)] is a member of the steroid/thyroid

nuclear receptor superfamily (1,2).

COUP-TFII is an orphan nuclear receptor that regulates the

transcription of numerous genes in multiple physiological and

pathological conditions (3), and

can adjust cellular processes, such as angiogenesis, metabolism and

differentiation, as a transcriptional regulator (3–5).

While it can act as either a transcriptional activator or

repressor, the latter appears to be more common (6).

Using conventional knockout and tissue-specific

conditional knockout mice, studies have revealed that COUP-TFII

serves an important role in heart development, angiogenesis and

vein identity determination (7–10).

Dysregulation of COUP-TFII has been implicated in the pathogenesis

of both cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and colorectal cancer (CRC)

(3). In CVDs, COUP-TFII serves a

role in vascular remodeling and energy metabolism (3), while in CRC, it may function as

either a tumor suppressor or promoter, depending on the cellular

context (3,11). However, the understanding of the

detailed molecular mechanisms linking COUP-TFII to these diseases

remains incomplete.

CVDs and CRC are common causes of mortality and

morbidity worldwide (12). Growing

evidence suggests a shared pathophysiology between CVDs and CRC,

despite these being separate disease entities (13–15).

In addition, CVDs and CRC have overlapping modifiable risk factors,

such as diet, physical inactivity and chronic inflammation

(16). The development of

therapeutic modalities has improved the survival rates of patients

with CRC, thus increasing the numbers of CRC survivors who are at

higher risk for a first or subsequent CVD event; this is partly

attributable to the shared pathophysiology of the two diseases, and

the cardiotoxic effect of anticancer treatment (15). It is reasonable to hypothesize that

therapeutic strategies to improve modifiable CRC risk factors will

also have a beneficial effect on CVD prevention and vice versa.

The present review aims to summarize the structure

and regulatory mechanisms of COUP-TFII, to review its mechanistic

roles in CVDs (Table I) and CRC

(Table II) by focusing on

published papers identified using PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with the key words

‘COUP-TFII (NR2F2)’ and ‘CVDs’, ‘COUP-TFII (NR2F2)’ and ‘CRC’, or

‘CVDs’ and ‘CRC’, and to provide future research directions.

| Table I.Roles and molecular mechanisms of

COUP-TFII in the vasculature and heart. |

Table I.

Roles and molecular mechanisms of

COUP-TFII in the vasculature and heart.

| First author/s,

year | Functions of

COUP-TFII | Molecular

mechanisms | Pathological

implications | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Pereira et

al, 1999; Wu et al, 2013; You et al, 2005; Chen

et al, 2012; Al Turki et al, 2014; Sissaoui et

al, 2020 | Vascular

development and patterning; expressed in venous ECs, atria,

coronary arteries, aorta and VSMCs; acts as a molecular switch

between venous and arterial differentiation | Binds to

cis-regulatory elements (e.g., HEY2 and FOXC1) to

repress arterial markers; recruits HDACs in venous ECs to actively

repress HEY2; interacts with ERG to promote

vein-specific gene expression; the −161K enhancer functions as a

bimodal switch based on COUP-TFII occupancy | Loss or forced

expression disrupts normal vascular identity, leading to aberrant

arterial marker expression in veins and vice versa | (7,8,10,42,44,45) |

| Cui et al,

2015 | Adult vascular

endothelium maintenance-maintains venous identity | Direct binding to

the BMP4 promoter to repress its expression; regulates

inflammatory (e.g., CXCL10/11 and CCL5) and

antithrombotic (for example, TFPI2) genes to prevent

EndMT | Dysregulation can

trigger EndMT, inflammation and altered antithrombotic

responses | (46) |

| Qin et al,

2010 | Angiogenesis -

promotes vessel stability and maturation | Directly

upregulates Ang-1 expression by binding with Sp1 to the Ang-1

promoter | Supports the

formation of stable blood vessels under physiological conditions;

disruption may impair vessel maturation | (20) |

| Dougherty et

al, 2023; Cao et al, 2019; Talati and Hemnes, 2015;

Poels et al, 2020; Rodríguez-García et al, 2017 | Pathological

angiogenesis and metabolic dysregulation; involvement in

atherosclerosis and PAH | Knockdown of

COUP-TFII activates AKT/STAT signaling and increases DKK1

expression; upregulates glycolytic genes (e.g., HK2, LDHA

and PFKFB3), enhancing oxidative stress and lactate

production | Elevated glycolysis

and lipogenesis destabilize atherosclerotic plaques and promote

endothelial proliferation, contributing to PAH pathogenesis;

overall, dysregulation leads to a pro-inflammatory,

hyperproliferative and migratory endothelial phenotype | (56–60) |

| Periera et

al, 1999; Lin et al, 2012; Al Turki et al, 2014;

Nakamura et al, 2011; Qiao et al, 2018; Upadia et

al, 2018; Cornea et al, 2008; Botto et al, 2001;

Perilhou et al, 2008; Vilhais-Neto et al, 2010;

Gruber and Epstein, 2004 | Heart

development-essential for proper cardiac morphogenesis;

conventional knockout leads to embryonic lethality (embryonic day

10) with poorly developed atria, cardinal veins and hemorrhagic

vessels; hypomorphic mutants display atrioventricular septal,

valvular defects and abnormal coronary morphogenesis | Regulates

transcriptional activation (missense variants affect activator

function while repressor function is preserved); interacts with

dosage-sensitive transcription factors (GATA4, TBX5 and NKX2-5);

environmentally responsive (modulated by high glucose and retinoic

acid via pathways such as the Foxo1 pathway) | Congenital heart

defects (atrial/ventricular septal defects, aortic stenosis,

coarctation of the aorta, DORV and VSD) | (7,9,44,61–68) |

| Wu et al,

2015; Kittleson et al, 2005; Hannenhalli et al,

2006 | Adult heart -

mitochondrial and metabolic regulation; maintains mitochondrial

function and metabolic homeostasis in cardiomyocytes | Overexpression

causes defects in the ETC; downregulates genes for mitochondrial

fusion and quality control (Mfn1, Mfn2, Opa1 and Pink1); suppresses

the PGC-1α-Sod2 pathway, leading to the accumulation of damaged

mitochondria; alters fatty acid and glucose metabolism | Mitochondrial

dysfunction and oxidative stress, leading to heart failure;

development of metabolic inflexibility in heart failure | (69–71) |

| Wu et al,

2015; Miao et al, 2022; Tan et al, 2020; Dhalla et

al, 2020; Dixon et al, 2012; Li et al, 2020 Ma

et al, 2020; Tang et al, 2021; Wang et al,

2022 | Elevated COUP-TFII

expression is observed in DIHF | Promotes

ferroptosis (an iron-dependent, non-apoptotic cell death marked by

lipid ROS accumulation) and mitochondrial dysfunction; knockdown

reduces mitochondrial damage and ferroptosis in palmitic

acid-treated neonatal rat cardiomyocytes; direct regulation of

mitochondrial metabolic regulator genes (for example, PPARα and

PGC-1α) | Exacerbation of

diabetic heart failure via increased oxidative stress,

mitochondrial damage and ferroptosis | (69,72–79) |

| Table II.Comparative summary of COUP-TFII

functions in CRC in different molecular contexts. |

Table II.

Comparative summary of COUP-TFII

functions in CRC in different molecular contexts.

| First author/s,

year |

Context/condition | Role of

COUP-TFII | Molecular

mechanisms/marker | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Shin et al,

2009; | High expression

levels in tissue | Tumor

suppressor | Associated with

improved | (80,81) |

| Yun et al,

2017 | microarray (early

studies) |

| survival, ↓ LN

metastasis |

|

| Yun and Park,

2020 | Overexpression in

SNU-C4 cells | Tumor

suppressor | ↑ p53, ↑ PTEN, ↓

Akt signaling | (82) |

| Yun et al,

2020 | Knockdown in HT-29

cells | Tumor

suppressor | ↑ Akt → ↓ GSK-3β →

↑ | (83) |

|

|

|

| β-catenin, ↑ MMP7,

↑ FOXC1 |

|

| Bau et al,

2014; | High expression

levels in EMT- | Tumor promoter | Directly activates

Snail1 | (84,86–88) |

| Cano et al,

2000; | prone CRC

cells |

| transcription → EMT

(by |

|

| Li et al,

2007; |

|

| downregulating

E-cadherin and |

|

| Kudo- Saito et

al, |

|

| enhancing

immunosuppression) |

|

| 2009 |

|

|

|

|

| Wang et al,

2017 | miR-21

overexpression | Tumor promoter | ↑ COUP-TFII →

inhibits | (90) |

|

|

|

| Smad7 → TGF-

β-induced EMT |

|

| Bao et al,

2019 | COUP-TFII

regulation of miR-34a | Tumor promoter | COUP-TFII → ↓

tumor- | (91) |

|

|

|

| suppressor miR-34a

→ ↑ cell |

|

|

|

|

| migration, ↓

chemosensitivity |

|

Literature search

A comprehensive literature search was conducted

using PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to identify relevant

studies on COUP-TFII in CVDs or in CRC. The search covered the

literature from January 1900 to January 2025. The inclusion

criteria were: i) Original research articles and reviews

investigating COUP-TFII expression and function in CVDs or CRC; ii)

studies using human tissue samples, cell lines or animal models;

iii) original articles and reviews under the key words ‘CVDs’ and

‘CRC’; and iv) articles published in English. The exclusion

criteria were: i) Studies lacking specific data on COUP-TFII; and

ii) non-English publications. All authors screened the articles,

and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Structure and regulatory mechanisms of

COUP-TFII

Structural characteristics

As shown in Fig.

1A, COUP-TFII is composed of six regions containing three main

domains: An N-terminal domain containing a transcriptional

activation function (AF) motif [1–78 amino acids (aa)], a

DNA-binding domain (DBD; 79–151 aa) and a C-terminal ligand binding

domain (LBD; 177–411 aa), separated by a hinge region (D) (2,3,17).

| Figure 1.Structure and transcriptional

regulatory mechanism of COUP-TFII. (A) Schematic structure of the

human COUP-TFII protein. The numbers represent the positions of

amino acids. (B) Transcriptional regulatory mechanism of COUP-TFII.

COUP-TFII binds to the 5′-AGGTCA-3′ motif or palindromic sequences

with various spacings (DR site), either directly (homodimer) or

indirectly, through heterodimer formation with other proteins (such

as RXR) to regulate downstream target gene expression. COUP-TFII

can also bind to Sp1 sites via interaction with Sp1 to

cooperatively activate gene expression. COUP-TFII, chicken

ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II; RXR, retinoid

X receptor; Sp1, specificity protein 1; TSS1, transcription start

site 1; DBD, DNA-binding domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; AF,

activation function; DR, direct repeat. |

The N-terminal A/B region containing AF1 motif is

required for the recruitment of coactivators or corepressors. DBD,

located in the C region, contains two zinc-finger motifs that

enable COUP-TFII to bind to specific DNA sequences referred to as

direct repeat (DR) motifs composed of the AGGTCA sequence. These

sequences are commonly found in the regulatory regions of target

genes involved in developmental and metabolic pathways. To regulate

a variety of target genes, the DBD of COUP-TFII recognizes and

binds to DR elements and palindromic sequences with variable

spacing (DR-1, DR-2 and DR-4) within the promoter regions of target

genes (2,3,17).

The LBD, located in the E region, facilitates

interactions with coactivators such as steroid receptor

coactivator-1 (SRC-1) and peroxisome proliferator activated

receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α), and corepressors such as

nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) and silencing mediator for

retinoid or thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) (2,3,17).

Although COUP-TFII lacks a known endogenous ligand,

the LBD modulates transcription through allosteric interactions

with coactivators or corepressors. Various classes of molecules can

interact with the LBD of COUP-TFII, including endogenous lipids and

metabolites (such as retinoic acid derivatives, fatty acids and

phospholipids), synthetic small molecules, steroid hormones,

peptides and coregulatory proteins (such as NCoR, SMRT and SRC-1).

The AF2 motif, located within the LBD, is pivotal for the

recruitment of coactivators or corepressors and modulating

transcriptional activity. The F region refers to the C-terminal

region of the COUP-TFII protein (2,3,17).

COUP-TFII is a ligand-regulated nuclear receptor.

Kruse et al (18)

demonstrated that COUP-TFII adopts an auto-repressed conformation,

as revealed by crystallographic analysis, due to the interaction

between the co-factor binding sites and the AF2 motif, preventing

co-factor recruitment in the absence of ligands. Ligands, such as

retinoic acids, can activate COUP-TFII by releasing it from its

auto-repressed conformation (18).

The findings of this integrative approach can enhance the

translational value of the structural analyses of COUP-TFII in the

absence or presence of ligands in drug development. However, to the

best of our knowledge, the physiological relevance of ligand

regulation remains unclear, with further studies being required to

identify endogenous ligands and validate tissue-specific

effects.

COUP-TFII can function as either a negative or

positive transcriptional regulator via direct binding to DNA

response elements (DR sites) or interaction with other

transcription factors [such as retinoid × receptor and specificity

protein 1 (Sp1)], respectively (3,17).

COUP-TFII can inhibit the transcription of target genes via the

recruitment of corepressors through the formation of homodimers or

heterodimers (Fig. 1B) (2,3).

Alternatively, it can also bind to Sp1 sites to activate the

transcription of target genes [such as neuropilin 2 and

angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1); Fig. 1B]

(19,20). The experimental evidence for this

mechanism was mainly obtained in in vitro studies and tumor

models (19,20). Qin et al (20) used a conditional COUP-TFII

knockout strategy in xenograft models to demonstrate that COUP-TFII

positively regulated tumor angiogenesis by directly binding to Sp1

binding sites in the promoter regions of angiogenesis-related

genes. These findings were supported by robust promoter-reporter

assays, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and loss-of-function

experiments, providing convincing mechanistic evidence. Therefore,

in cancer biology contexts, the experimental quality of these

studies (19,20) is high. However, beyond oncogenic

models, their physiological relevance has yet to be validated.

Further studies using cardiovascular- or angiogenesis-specific

models are necessary to confirm the functional relevance of

COUP-TFII-Sp1 interactions in non-cancer conditions.

Regulatory mechanisms of COUP-TFII

expression and activity

The regulatory mechanisms of COUP-TFII expression

and activity are not completely understood, because its specific

ligand has not yet been fully characterized. The expression and

activity of COUP-TFII are tightly regulated by various mechanisms,

such as transcriptional and epigenetic regulation, and by

interactions with signaling pathways.

Transcriptional regulation of COUP-TFII

expression

Upstream regulators of COUP-TFII

expression

COUP-TFII expression has been reported to be

modulated by sonic hedgehog (Shh) during developmental processes,

because an Shh-responsive element was identified in the COUP-TFII

promoter (21). This finding was

based on in vitro promoter assays, and although revealing a

potential regulatory element, in vivo results were lacking.

Thus, the physiological significance of this regulation has yet to

be further validated. COUP-TFII expression has also been reported

to be regulated by retinoic acid (22,23),

estradiol (24) or MAPK pathways

(25). Retinoic acid and its

derivatives regulate COUP-TFII expression via nuclear

receptor-mediated pathways. This regulation is important to

maintain tissue homeostasis and differentiation (22,23).

However, since the study by Soosaar et al (23) was solely based on in vitro

experiments using a combination of cell culture and biochemical

assays, their findings may not be generalized. In addition,

retinoic acid has been reported to suppress COUP-TFII expression in

some contexts (such as the rat glioblastoma C3 and human

glioblastoma U373 cell lines), suggesting that the cellular context

and specificity of receptor isoforms influence the outcome of

retinoic acid signaling (23).

COUP-TFII expression is also regulated by other factors, including

Oct4 (26), microRNA

(miRNA/miR)-302 (26) and Ets-1

(27). COUP-TFII expression has

been revealed to be repressed by Oct4, which binds to the COUP-TFII

promoter, and by miR-302, which interacts with its 3′-untranslated

region (3′-UTR) (26). Oct4, as a

key pluripotency factor, interacts with COUP-TFII to regulate its

transcriptional activity, particularly in stem cell maintenance and

differentiation (26). The

findings of Rosa and Brivanlou (26) were based on overexpression and

knockdown experiments without addressing potential off-target

effects; however, in stem cell models, the results were

comprehensive. Furthermore, the suppressive effect of Oct4 on

COUP-TFII may not be conserved in non-pluripotent cell types,

suggesting that this regulation may be limited by tissue

specificity (26). Petit et

al (27) revealed that Ets-1,

together with SRC-1, could activate COUP-TFII expression in

luciferase reporter assays. This study is insightful for providing

explainable potential mechanisms. However, its conclusions are

derived from in vitro assays, and direct binding of Ets-1 to

the endogenous promoter in physiological conditions has yet to be

fully demonstrated. COUP-TFII expression is repressed by

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α in hypoxic endometrial stromal

cells (28) and by the

artery-specific Δ-like canonical Notch ligand 4 -

Notch-hairy/enhancer of split-related with YRPW motif protein 2

(Hey2) signaling axis in endothelial progenitor cells under hypoxic

conditions (29). Both studies

(28,29) emphasized the importance of hypoxic

signaling; however, since the results are confined to specific cell

types, they do not address whether similar regulation occurs in

other cell lineages.

miRNAs are known to be important

post-transcriptional regulators in cancer (30). In particular, Yun and Park

(11) reviewed regulation of

COUP-TFII expression by miRNAs. For example, miRNA-27b

downregulates COUP-TFII expression through interaction with its

3′-UTR, leading to the inhibition of proliferation and invasion of

gastric cancer cells in vitro, and metastasis of gastric

cancer cells to the liver in vivo (31). A study by Feng et al

(31) demonstrated both in

vitro and in vivo effects, which reinforces its

conclusions. However, the mechanistic association between COUP-TFII

suppression and phenotypic outcomes was not directly validated by

rescue experiments, leaving room for alternative explanations.

Additionally, miR-302, miR-302a, miR-382, miR-101, miR-27a and

miR-194 have been reported to downregulate COUP-TFII expression,

and to have diverse functions in different cell types, such as

embryonic stem cells, mesenchymal C3H10T1/2 cells, colorectal

cancer cells and prostate cancer cells (26,32–37).

These studies used luciferase reporter assays, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and western blot analyses to

demonstrate miRNA-mediated repression of COUP-TFII. However, the

studies have several limitations. For example, Rosa and Brivanlou

(26) based their findings on

embryonic stem cells, limiting their applicability to cancer. For

miR-382 and miR-101 (34–36), COUP-TFII downregulation was

observed, but indirect effects could not be excluded. In the case

of miR-27a (36), opposing roles

in different tissues suggest context dependence. The study by Jeong

et al (37) demonstrated

that miR-194 functions as a key regulator of COUP-TFII in

mesenchymal stem cells, directing their fate toward differentiation

into osteoblasts and adipocytes.

Overall, although evidence supports the miRNA-based

regulation of COUP-TFII, context specificity, functional redundancy

and cell type-dependent expression complicate the identification of

consistent regulatory mechanisms.

Epigenetic regulation of COUP-TFII

expression

Methylation of DNA, usually at CpG island sites in

promoters of genes, has been reported to inhibit transcription by

interfering with the binding of transcription factors (38,39).

Using the CpGPLOT program from the European Bioinformatics

Institute website (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/emboss/cpgplot), Al-Rayyan et

al (40) revealed that the CpG

island is located in the promoter and within exon 1 of COUP-TFII,

and demonstrated that transcription of COUP-TFII might be regulated

by DNA methylation. The authors also revealed that methylation of

the COUP-TFII promoter led to its reduced expression, which

contributed to resistance to antiestrogen treatment in

endocrine-resistant breast cancer cells (40). This study provides important

evidence associating epigenetic repression of COUP-TFII with

therapeutic resistance, using bioinformatics prediction (CpGPLOT),

bisulfite sequencing and expression analysis. However, the findings

were based on a specific endocrine-resistant breast cancer cell

line (MCF-7-derived), which limits the generalizability.

Furthermore, while COUP-TFII repression was associated with

resistance, functional rescue assays were not performed, and thus,

the causal relationship is undetermined.

A total of four isoforms (Iso1, Iso2, Iso3 and Iso4)

are encoded by the NR2F2 gene. NR2F2-Iso1 is a full-length

protein composed of an N-terminal AF1 motif, a DBD, a hinge region

and an LBD containing a ligand-dependent AF2 motif. NR2F2-Iso2,

NR2F2-Iso3 and NR2F2-Iso4 are different from NR2F2-Iso1 in their

N-terminal sequences and do not have a DBD (41). Davalos et al (41) demonstrated that when neural crest

cells (NCCs) differentiated into melanocytes, NR2F2-Iso2 expression

was silenced by DNA methylation, whereas during the progression of

metastatic melanoma, this process was reversed. Thus, the study

suggested that DNA methylation and demethylation serve important

roles in the progression of metastatic melanoma, and their

regulation of NR2F2 activity through NR2F2-Iso2 contributes to the

acquisition of NCC-like and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

(EMT)-like features in transformed melanocytes (41).

Davalos et al (41) combined genome-wide methylation

profiling with functional assays to reveal that epigenetic

reactivation of NR2F2-Iso2 promoted melanoma progression. While the

study provided supportive evidence, it depended on melanoma cell

lines and xenografts, which may not fully reflect the heterogeneity

of human tumors. Additionally, since the association between

NR2F2-Iso2 and EMT-like features was based on correlative data and

functional assays, the direct molecular targets remain unknown.

The role of NR2F2 isoforms appears to be

context-dependent. In contrast to their oncogenic role in melanoma,

some truncated isoforms lacking the DBD exhibit growth-suppressive

effects in breast and lung cancer. These discrepancies suggest that

isoform function is influenced by cell type, co-regulators and

signaling context. Therefore, the pro-metastatic role of NR2F2-Iso2

should not be generalized across all types of cancer. Further

research should be performed to define isoform-specific mechanisms

and interactions in diverse tumor types.

Interactions with signaling pathways

MAPK pathway

Activation of the MAPK pathway has been reported to

increase COUP-TFII expression in certain cellular contexts. For

example, in breast cancer cell lines with elevated MAPK activity,

COUP-TFII levels are increased (25), suggesting that this pathway can

upregulate COUP-TFII as part of a broader cellular response to

growth signals. However, the precise relationship between MAPK

signaling and COUP-TFII expression is complex, and appears to vary

depending on the specific cell type and environmental context. This

study examined the association between MAPK signaling and COUP-TFII

upregulation in breast cancer models using pharmacological

inhibitors, suggesting an association between pathway activation

and COUP-TFII expression (25).

However, it lacks evidence regarding direct transcriptional

regulation by MAPK effectors, such as ERK, ETS like-1 protein or

c-fos. The study also used a limited number of cell lines, and

failed to investigate potential pathway interactions, such as

crosstalk with PI3K/AKT or hormonal signaling.

Notch signaling

Notch signaling serves an antagonistic role in

regulating COUP-TFII expression (10,29).

In endothelial cells (ECs), activation of Notch signaling leads to

a reduction in COUP-TFII levels, which in turn promotes arterial

differentiation (10,42). Conversely, COUP-TFII can inhibit

Notch signaling to maintain venous identity, thereby influencing

cell fate decisions during vascular development (10,42).

This reciprocal regulation emphasizes the role of COUP-TFII in

establishing and preserving vascular heterogeneity. Taken together,

these findings are supported by studies (10,42)

using genetic mouse models, lineage tracing and molecular assays

that demonstrate a causal association between Notch activation and

COUP-TFII downregulation in ECs during vascular development.

However, the majority of the studies (10,42)

focused on embryonic or early postnatal stages, leaving its role in

adult or pathological conditions unclear. It is also uncertain

whether this regulatory axis applies to other vascular beds, such

as lymphatic or tumor endothelium. While mutual antagonism between

COUP-TFII and Notch in development processes has been established,

its dynamics in disease contexts require further investigation

across diverse tissues.

Wnt/β-catenin pathway

COUP-TFII expression has been reported to be

upregulated by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (43). ChIP assays have demonstrated that

β-catenin/T-cell factor 7-like 2 or transcription factor 7-like 2

(TCF7L2) complexes bind directly to the COUP-TFII promoter, leading

to increased transcription. This interaction is notable in the

context of cell differentiation. For example, activation of Wnt

signaling, leading to the upregulation of COUP-TFII via

β-catenin/TCF7L2 complexes, results in the suppression of adipocyte

differentiation by inhibiting the expression of the adipogenic

transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

(PPAR)γ (43). Okamura et

al (43) demonstrated that

β-catenin/TCF7L2 directly bound to the COUP-TFII promoter in ChIP

and reporter assays in preadipocyte models, and confirmed

Wnt-mediated regulation through gain- and loss-of-function

approaches. However, the focus of the study on adipocytes limited

the generalizability to other cell types. It also remains undefined

whether upregulation of COUP-TFII is a primary Wnt response, or a

downstream effect. Broader in vivo and multi-lineage studies

are needed to fully define the mechanisms by which Wnt signaling

modulates COUP-TFII expression.

COUP-TFII in CVDs

Roles and molecular mechanisms of

COUP-TFII in the vasculature: From developmental patterning to

pathological angiogenesis

COUP-TFII is predominantly expressed in venous ECs,

the atria, coronary arteries, the aorta (44) and vascular smooth muscle (8). COUP-TFII is important for proper

vascular development (7). An in

vivo study revealed that genetic ablation of COUP-TFII induces

the ectopic expression of arterial markers in venous ECs, whereas

forced expression of COUP-TFII in arterial cells suppresses

arterial gene expression, underscoring its role as a molecular

switch in vascular differentiation (10). Mechanistically, COUP-TFII binds to

cis-regulatory elements at key loci, such as HEY2 and

FOXC1 which are required for arterial differentiation. By

binding to their regulatory regions, COUP-TFII inhibits the

activation of the arterial differentiation program (42). A study by Sissaoui et al

(45) demonstrated that in venous

ECs, COUP-TFII recruited histone deacetylases (HDACs) to actively

repress the expression of HEY2, a key mediator of arterial

identity. Furthermore, COUP-TFII interacted with ETS-related gene

(ERG) to induce the expression of several vein-specific

genes, such as family with sequence similarity 174 member B, a

disintergrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin motifs 18 and

LIM homeobox 6 (45).

The working model proposed by Sissaoui et al

(45) suggests that a regulatory

element (the −161K enhancer) acts as a bimodal switch depending on

the cellular context: In venous ECs, COUP-TFII occupies this

enhancer to block ERG-mediated activation of HEY2, whereas

in arterial ECs lacking COUP-TFII, ERG binds to the −161K enhancer

and promotes arterial gene expression. In the study by Sissaoui

et al (45),

CRISPR-CRISPR-associated protein 9 enhancer deletion,

ChIP-sequencing and reporter assays were effectively used to define

the COUP-TFII-HDAC-ERG axis and demonstrate the role of COUP-TFII

as a repressor of arterial identity in venous ECs. However, the

focus on embryonic tissues and human umbilical vein ECs limits the

relevance to adult vasculature and pathological angiogenesis. In

pathological settings such as tumors, COUP-TFII expression can

persist in vessels with arterial features, suggesting that its

regulatory role may be more flexible than previously suggested

(20). Broader, context-specific

studies are needed to clarify its function in vascular

remodeling.

Cui et al (46) revealed the role and molecular

mechanism of COUP-TFII in adult vascular endothelium, demonstrating

that knockdown of COUP-TFII in adult vascular ECs upregulated the

expression levels of inflammatory genes [such as C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand (CXCL)10, CXCL11 and C-C motif chemokine ligand

(CCL)5], while downregulating the expression levels of

antithrombotic genes [such as tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2

(TFPI2)]. This dysregulation could trigger

endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT). Furthermore, the

expression levels of arterial markers (such as ephrin-B2 and hes

family bHLH transcription factor 1/4), expression of genes involved

in angiogenesis [such as endothelial PAS domain protein 1/HIF-2α,

ephrin-A1, tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin like and EGF like

domains-2 (Tie-2) and ephrin-A4] and the osteogenic potential

leading to calcium deposition of adult ECs were suppressed by

COUP-TFII overexpression. Cui et al (46) demonstrated that the actions of

COUP-TFII in adult ECs may be mediated by its negative regulation

of bone morphogenic protein 4 (BMP4) through direct binding to the

BMP4 promoter. These results suggest that COUP-TFII serves a key

role in maintaining the venous identity in adult ECs, as well as

during development (46). This

study focused on adult ECs, a less explored context for COUP-TFII.

Cui et al (46) used in

vitro knockdown/overexpression and ChIP assays to reveal that

COUP-TFII suppressed pro-inflammatory, angiogenic and osteogenic

gene programs, reinforcing their conclusions. However, reliance on

cultured ECs limits in vivo relevance, while other pathways

regulating BMP4 were not fully excluded. Their findings suggest

anti-inflammatory and anti-osteogenic roles of COUP-TFII in adult

ECs, which are inconsistent with reports of its pro-angiogenic and

immunosuppressive effects in tumor models (17,20).

These discrepancies underscore context-dependent functions of

COUP-TFII and emphasize the need for further investigations in

normal vs. diseased adult vasculature.

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels,

relies on coordinated interactions among shear stress, vascular

growth factors such as VEGF and Ang-1 (a ligand for Tie-2),

intracellular signaling pathways (such as Notch) and intercellular

contacts (47–54).

Knockdown experiments in mouse aortic vascular

smooth muscle cells and C3H10T1/2 fibroblasts have revealed that

COUP-TFII positively regulates Ang-1 expression levels (20). This regulation occurs through the

direct binding of COUP-TFII, in cooperation with Sp1, to the Ang-1

promoter. The upregulation of Ang-1 by COUP-TFII suggests a

pro-angiogenic role, promoting vessel stability and maturation

(20). However, this study

(20) was limited by its

dependence on in vitro fibroblast and smooth muscle cell

models, which may not reflect the in vivo angiogenic

environment. Although ChIP assays verified COUP-TFII binding to the

Ang-1 promoter, its functional relevance in ECs in vivo

remains unvalidated. Furthermore, the role of COUP-TFII in

angiogenesis appears to be context-dependent, while it can promote

Ang-1 expression, another study has revealed that it may suppress

VEGF receptor expression and inhibit sprouting, particularly in

tumors (55). These conflicting

findings suggest that COUP-TFII may balance vascular stabilization

and angiogenic modulation in a tissue- and context-specific

manner.

Dysregulation of COUP-TFII can lead to pathological

angiogenesis, contributing to various vascular diseases, such as

atherosclerosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (56). For instance, in multiple types of

human ECs (e.g., lung microvascular, coronary artery and pulmonary

artery ECs), knockdown of COUP-TFII activates the AKT and STAT

signaling pathways. This activation is accompanied by an increase

in Dickkopf-related protein 1 expression, resulting in a

pro-inflammatory, proliferative, hypermigratory and

apoptosis-resistant phenotype. These changes are further

characterized by the induction of EndMT, increased oxidative

stress, enhanced lactate production and the upregulation of

glycolytic genes, such as hexokinase 2, lactate dehydrogenase A and

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphophatase 3 (PFKFB3)

(56). The strengths of this study

include the use of multiple types of ECs, and the integration of

molecular, metabolic and phenotypic analyses (56). However, key limitations include the

reliance on in vitro knockdown models, which may not fully

reflect the complexity of the in vivo vascular

environment.

Suppression of COUP-TFII has been associated with

the induction of glycolytic and lipogenic pathways (57,58).

Elevated PFKFB3 levels, in particular, destabilize atherosclerotic

plaques and contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis

(59). Similarly, enhanced

endothelial glycolysis and proliferation, driven by COUP-TFII

suppression, may underlie the pathogenesis of PAH (57,60).

These studies are notable for their mechanistic data associating

metabolic shifts with vascular dysfunction and their use of

relevant EC models (57,60). However, limitations include a lack

of in vivo causal data, and uncertainty regarding whether

the metabolic changes are a primary driver, or a secondary effect,

of the diseases. Furthermore, other studies suggest that COUP-TFII

loss may induce protective metabolic adaptations in other contexts,

indicating potential tissue- or disease-specific variability that

warrants further investigation (3,5).

Role of COUP-TFII in the heart

Knockout mouse models and human genetic analyses

have been used to elucidate the role of COUP-TFII in the heart

during development (7,9,44,61–63).

Conventional COUP-TFII knockout mice die at embryonic day 10,

exhibiting poorly developed atria and cardinal veins with enlarged

hemorrhagic vessels, while hypomorphic mutants are born with

atrioventricular septal and valvular defects, as well as abnormal

coronary morphogenesis (7,9). EC-specific COUP-TFII knockout mice

exhibit embryonic lethality due to vascular defects, including

hypoplastic endocardial cushions, hemorrhage, and thin, dilated

vessels (9). This study provided

in vivo evidence for the key role of COUP-TFII in vascular

development, using a genetically controlled, cell type-specific

knockout model (9). However,

limitations include the early lethality of the models, which

restricts analysis to embryonic stages, and the lack of mechanistic

investigation of downstream pathways. To the best of our knowledge,

while no direct conflicting results have been reported, some

studies have suggested that the function of COUP-TFII may differ in

postnatal or under pathological conditions (17,20,55),

indicating potential stage-specific roles that require further

research.

Human genetic studies have revealed that COUP-TFII

missense variants or 15q terminal deletions encompassing COUP-TFII

are associated with atrial or ventricular septal defects, either in

isolation or in combination with other congenital heart defects,

such as aortic stenosis and coarctation of the aorta (44,61–63).

In vitro experimental data indicate that all six COUP-TFII

missense variants (Gln75dup, Asp170Val, Asn205Ile, Glu251Asp,

Ser341Tyr and Ala412Ser), identified in patients with

atrioventricular septal defects, have a measurable impact on the

transcriptional activator function of COUP-TFII in at least one of

two assays: Nerve growth factor-induced protein A or apolipoprotein

B (APOB) promoter-driven luciferase assays in HEK293 cells. By

contrast, the repressor function of COUP-TFII appears to remain

intact, as revealed by APOB promoter-driven luciferase assays in

HEPG2 cells. The promoter-specific effects of these individual

mutations likely reflect the complexity of the protein-protein

interactions involving COUP-TFII, which vary, depending on the

tissue, developmental stage and genomic context (44). The strengths of this study include

the integration of genetic and functional data; however,

limitations derive from the use of non-cardiac,

overexpression-based assays that may not accurately reflect in

vivo cardiac transcriptional networks (44). In addition, the mutation-specific

and promoter-dependent effects underscore the complexity of

COUP-TFII regulation, while for the majority of variants, no in

vivo confirmation of pathogenicity has been provided.

COUP-TFII may also function as an environmentally

responsive factor by mediating the effects of known non-genetic

congenital heart disease risk factors, such as high glucose

(64) and retinoic acid levels

(65). Insulin and glucose have

been revealed to suppress COUP-TFII expression via the Foxo1

pathway in hepatocytes and pancreatic cells (66). Furthermore, COUP-TFII serves an

important role in retinoic acid signaling during development

(67). However, to the best of our

knowledge, direct evidence for its role in the developing heart is

scarce. Thus, the translational relevance of these findings remains

uncertain. Further studies are required to determine how glucose

and retinoic acid levels may alter COUP-TFII expression in the

developing heart. Additionally, COUP-TFII has been reported to

interact with other dosage-sensitive transcription factors that are

key for heart formation, including GATA binding protein 4 (GATA4),

T-box transcription factor 5 and NK2 homeobox 5 (68). Specifically, a novel heterozygous

mutation (p.G83X) in the COUP-TFII gene was identified in a family

affected by congenital double outlet right ventricle and

ventricular septal defect. Functional investigations demonstrated

that the COUP-TFII G83X-mutant protein exhibited no transcriptional

activity. Furthermore, the mutation abrogated the synergistic

transcriptional activation of COUP-TFII with GATA4 (62). These functional assays provide

mechanistic insights, but are limited by the use of overexpression

systems in non-cardiac cells. No in vivo validation or

comprehensive mutational analysis was carried out, and the

interaction between COUP-TFII and environmental signals in human

cardiogenesis has yet to be fully elucidated.

The role and molecular mechanisms of COUP-TFII in

the adult heart have been investigated using COUP-TFII

overexpression mouse models (69),

and two independent cohorts of patients with non-ischemic dilated

cardiomyopathy (DCM) (70) and

idiopathic DCM (dataset no. GSE406) (71). Using COUP-TFII-overexpressing mice

and rescue experiments through the removal of COUP-TFII in

calcineurin-transgenic (CnTg/Cre/F+) mice, this study

has demonstrated that COUP-TFII overexpression induced defects in

the electron transport chain (ETC), downregulation of genes

involved in mitochondrial fusion and quality control [such as

mitofusin (Mfn)1 and Mfn2, optic atrophy 1 (Opa1), and PTEN-induced

kinase 1 (Pink1)], accumulation of damaged mitochondria, and

reduced mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging

capacity, leading to oxidative stress and heart failure.

Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by COUP-TFII overexpression may

be mediated through the suppression of the PGC-1α-superoxide

dismutase 2 (Sod2) pathway (69).

Thus, alterations in the expression of key genes involved in both

fatty acid and glucose metabolism by COUP-TFII may contribute to

the development of metabolic inflexibility in heart failure

(69). These findings are

supported by gain- and loss-of-function models and transcriptomic

data from two independent DCM cohorts (70,71).

However, the limitations of these studies include the use of

non-physiological overexpression levels, which may not accurately

reflect COUP-TFII dysregulation in human disease, and a lack of

longitudinal data to determine causality in patients (70,71).

In addition, other COUP-TFII targets relevant to calcium handling,

fibrosis or apoptosis were not explored and potential

context-dependent roles of COUP-TFII in different tissues remain

unresolved.

Increased COUP-TFII expression has been observed in

diabetes-induced heart failure (DIHF) (72). Although metabolic disturbances,

oxidative stress-induced cardiomyocyte death, inflammation and

mitochondrial dysfunction are known to contribute to cardiac

remodeling in DIHF, the pathophysiology and underlying mechanisms

of DIHF remain unclear (73,74).

A previous study demonstrated that the overexpression of COUP-TFII

exacerbated DIHF by promoting ferroptosis and mitochondrial

dysfunction, as evidenced by reduced mitochondrial damage and

ferroptosis after COUP-TFII knockdown in palmitic acid (PA)-treated

neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) (72). Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent,

non-apoptotic form of cell death, is characterized by the

accumulation of lipid ROS and mitochondrial overload (75). Although ferroptosis contributes to

the development of CVDs and its suppression may alleviate diabetic

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (76–78)

and cardiomyopathy (79), the role

of mitochondria in ferroptosis remains controversial. Further

studies are needed to validate the association between PA-induced

ferroptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in NRCMs. Taken together,

the aforementioned studies suggest that COUP-TFII directly

regulates mitochondrial metabolic regulator genes, including PPARα

and PGC-1α (69), and its

upregulation is associated with heart failure, possibly as a result

of mitochondrial dysfunction (69,72).

While the study effectively associates COUP-TFII with ferroptosis

through lipid ROS and mitochondrial stress, its reliance on

neonatal rat models limits its translational relevance (69). Additionally, the mechanistic role

of mitochondria in ferroptosis is still open to debate (75–79),

and the causal relationship between COUP-TFII upregulation and DIHF

in human hearts is still unconfirmed. Further in vivo

validation and exploration of the interaction of COUP-TFII with key

mitochondrial regulators such as PPARα and PGC-1α are needed.

COUP-TFII in CRC

Tumor-suppressive role of COUP-TFII in

CRC

Several studies have demonstrated that COUP-TFII

acts as a tumor suppressor in CRC (80–83).

A retrospective study using tissue microarray assays have indicated

that high COUP-TFII expression is associated with improved survival

rates and reduced lymph node metastasis in patients with CRC;

however, the initial study was limited by small sample sizes and

short follow-up periods (80).

These findings have subsequently been confirmed in larger cohorts

with extended follow-up durations (81), supporting the hypothesis that

COUP-TFII exerts tumor-suppressive effects in CRC.

Functional studies in human CRC cells have provided

mechanistic insights. In SNU-C4 cells, COUP-TFII overexpression

suppressed proliferation and invasion by upregulating the tumor

suppressors p53 and PTEN, and by inhibiting Akt activity,

respectively (82,83). Conversely, COUP-TFII knockdown in

HT-29 CRC cells enhanced cell proliferation and invasive

capabilities through the activation of the Akt pathway, leading to

glycogen synthase kinase-3 β inactivation, β-catenin stabilization,

and the upregulation of MMP7 and FOXC1 (83); however, the use of only two CRC

cell lines (SNU-C4 and HT-29) limits the generalizability. These

results underscore the function of COUP-TFII as a negative

regulator of tumor aggressiveness in CRC. However, additional in

vivo validation studies are necessary to confirm these findings

and fully elucidate the mechanism by which COUP-TFII modulates CRC

progression.

Tumor-promoting role of COUP-TFII in

CRC

By contrast, a growing body of evidence indicates a

tumor-promoting role of COUP-TFII under certain conditions. For

example, patients with CRC with high COUP-TFII expression have an

increased risk of metastasis and reduced overall survival, compared

with patients with CRC with low COUP-TFII expression (84,85).

Mechanistically, COUP-TFII directly binds to the promoter region of

the Snail1 gene, a master regulator of EMT, leading to the

suppression of E-cadherin and increased immunosuppressive signaling

(84,86–88).

Additionally, miR-21, an oncomiR highly expressed in various types

of cancer (89), increases

COUP-TFII expression, which in turn promotes TGF-β-induced EMT by

inhibiting Smad7 (90). COUP-TFII

can also regulate the expression of miR-34a (91), a well-known tumor suppressor miRNA

that inhibits tumor cell migration and promotes chemosensitivity

(92–95). Notably, COUP-TFII-regulated miR-21

inhibits PTEN and elevates the levels of prostaglandin

E2, a pro-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic mediator, by

suppressing 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase, further

contributing to tumor progression and inflammation (3,90).

Although these findings are supported by cell and animal models,

limitations remain, including reliance on overexpression systems,

and unclear relevance across different types of cancer. A

conflicting report of the anti-inflammatory roles of COUP-TFII in

other tissues suggests context-dependent effects (96), emphasizing the need for further

validation in human tumors and diverse inflammatory settings.

Dual functions of COUP-TFII as either a

tumor suppressor or a tumor promoter

COUP-TFII exhibits context-dependent dual roles in

CRC, functioning either as a tumor suppressor or as a tumor

promoter, depending on the molecular and cellular environment

(3,11). To illustrate these dichotomous

roles, Table II summarizes the

molecular and phenotypic outcomes associated with COUP-TFII

expression in CRC.

The findings presented in Table II highlight the dualistic and

context-dependent role of COUP-TFII in CRC, where its functional

role is modulated by dynamic interactions with transcriptional

regulators, non-coding RNAs and oncogenic signaling pathways.

As aforementioned, discrepancies in reported

findings are possibly due to differences in study conditions, such

as experimental models, patient cohorts and methodological

approaches. Additionally, the majority of the aforementioned

studies relied on in vitro and animal models, which may not

fully recapitulate the pathophysiology of human CRC. Another

limitation is the variability in COUP-TFII detection methods, such

as differences in antibody specificity and RNA expression analysis

techniques, which could contribute to inconsistent results. Future

studies with standardized methodologies, large patient cohorts and

human experimental data are needed to clarify the role of COUP-TFII

in CRC.

Interrelation between CVDs and CRC

CVDs and CRC are among the leading causes of

mortality worldwide (12). CRC is

the third most common malignancy worldwide, accounting for 11% of

all cancer diagnoses (97).

Although CVDs and CRC are distinct disease entities, emerging

evidence suggests that they may share common features (98,99).

Using an ischemic cardiomyopathy C57BL/6J-ApcMin/J

(APCmin) mouse model, researchers identified a potential

causal association between heart failure and CRC by observing the

association of presence of heart failure with enhanced tumor

formation, possibly via cardiac excreted factors, such as SerpinA3,

fibronectin and paraoxonase 1 (100). This study provided valuable

insights into a potential causal association between heart failure

and CRC, whereas its interpretation is still limited due to the use

of a familial CRC model that does not fully recapitulate sporadic

CRC, and the lack of mechanistic validation using targeted

interventions, such as knockdown or neutralization of candidate

cardiac excreted factors. In a clinical study, patients aged >65

years with stage I–III CRC were revealed to have a higher risk of

developing new-onset CVDs compared to a matched cohort of Medicare

patients without cancer (13),

suggesting the possibility of shared vulnerability or cancer

treatment-related cardiovascular complications. However, the

observational nature of the study lacks causal inference, while the

residual confounding effect of common risk factors (such as age,

diabetes and smoking) cannot be excluded. Two meta-analyses have

demonstrated that use of angiotensin converting enzyme

inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and renin-angiotensin

system (RAS) inhibitors was associated with a decreased risk of

CRC, respectively (101,102). These findings indicate that

hypertension might be a causal factor for CRC. Although these

findings are promising, the analyses are limited by heterogeneity

in study design, population characteristics and potential

indication bias, since patients receiving RAS inhibitors may be

healthier or more closely monitored than non-users. Furthermore,

emerging evidence indicates that chronic inflammation and oxidative

stress, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms for both

diseases, may contribute to the association between CVDs and CRC

(16,103,104). Additional mechanisms that have

been suggested include the cardiotoxicity of certain anticancer

agents, shared molecular pathways between the two diseases and

innate immunity (103,105–107). However, while these mechanisms

are supported by both experimental and clinical evidence (16,103–107), the evidence remains largely

correlative and prospective studies with mechanistic endpoints are

needed to clarify their roles and causality.

COUP-TFII as a common molecular

regulator of CVDs and CRC

Despite the controversial roles of COUP-TFII in

CRC, growing evidence (3,5,20,46,69,82,89,90)

has associated chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, angiogenesis

and metabolic dysregulation with both CVDs and CRC, with COUP-TFII

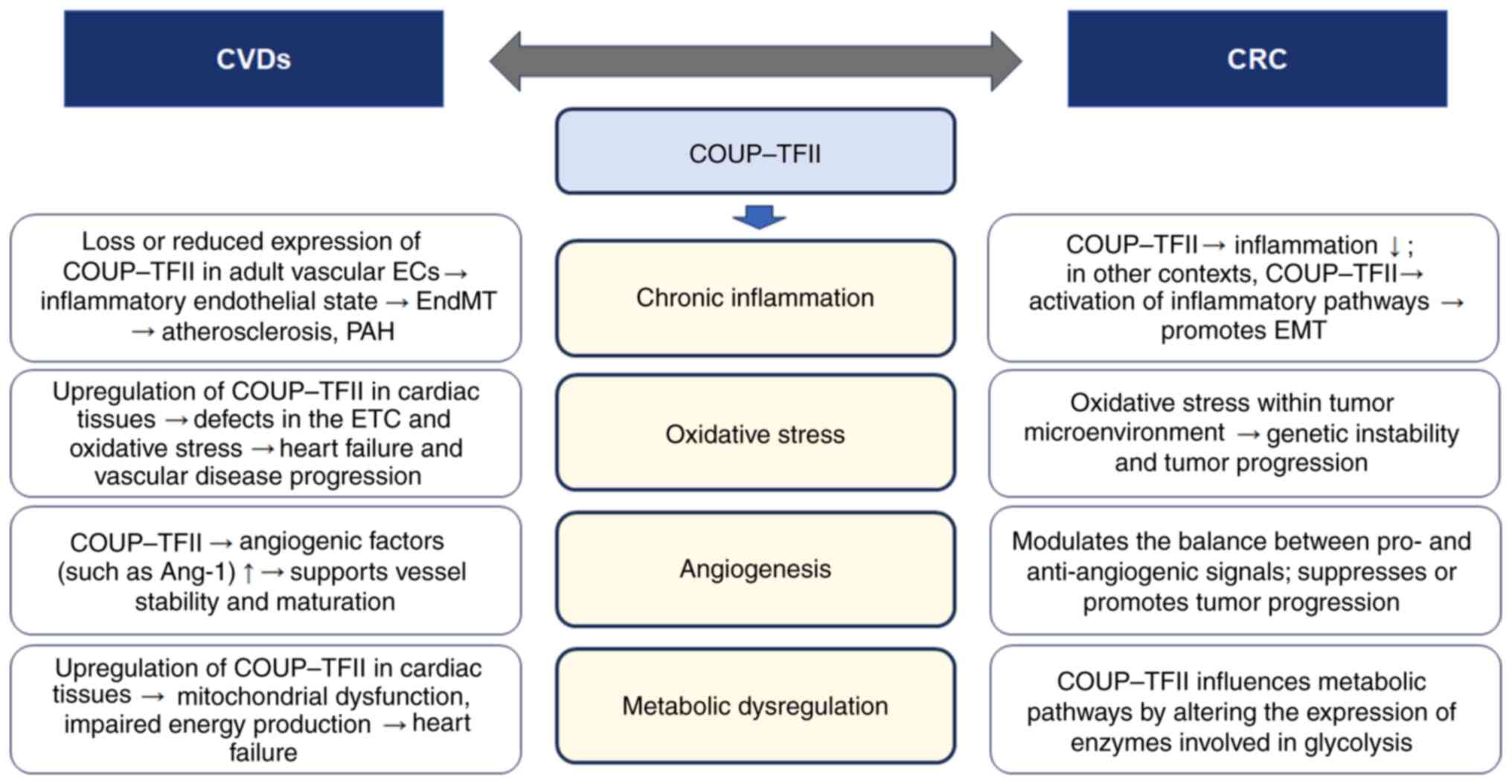

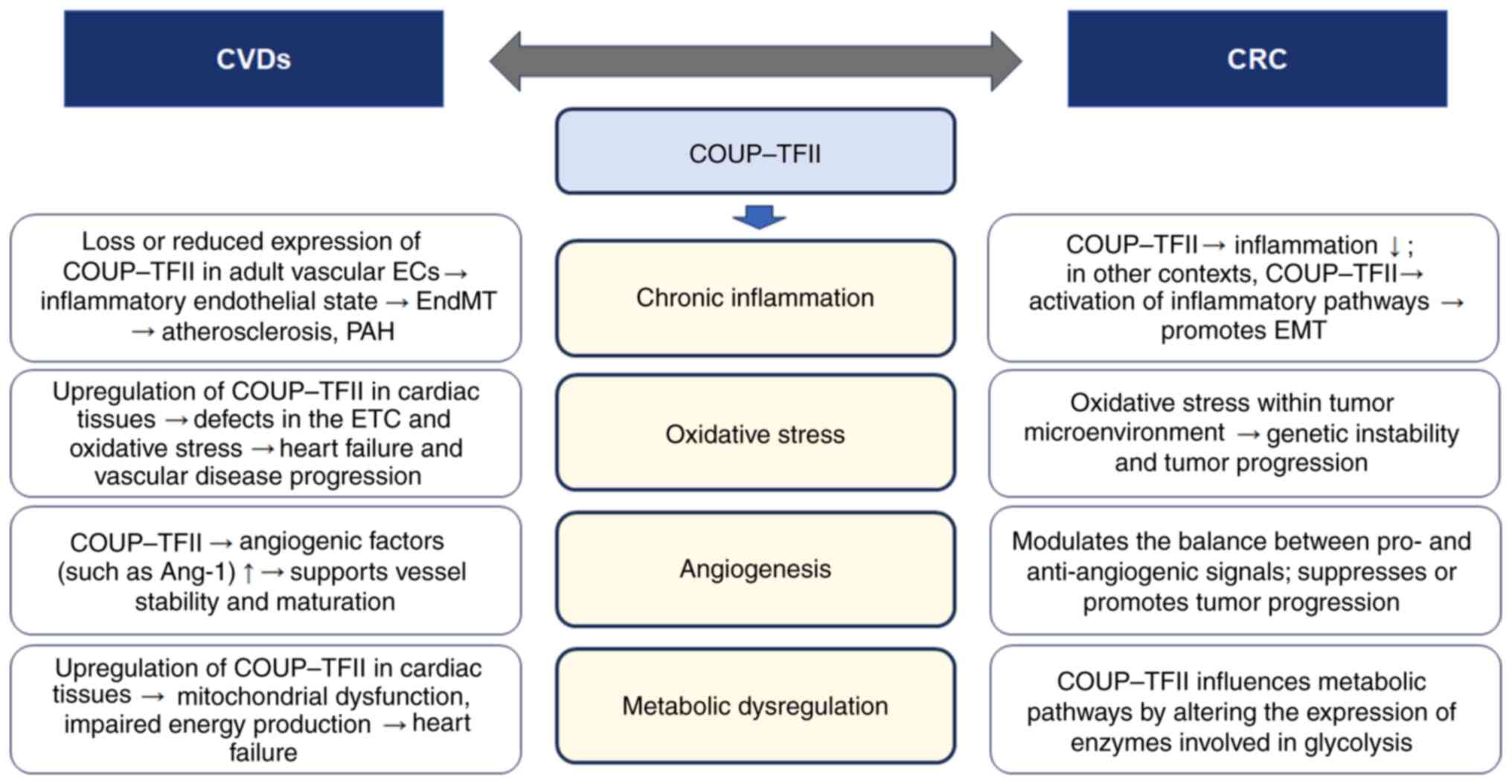

serving as a common molecular regulator. Fig. 2 illustrates the molecular

mechanisms by which COUP-TFII functions as a common regulator in

both CVDs and CRC.

| Figure 2.Schematic illustration of the

molecular mechanisms by which COUP-TFII functions as a common

regulator in both CVDs and CRC. Although CVDs and CRC are distinct

disease entities, they share common pathophysiological features. In

particular, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, angiogenesis

and metabolic dysregulation by COUP-TFII may serve roles in the

pathogenesis of both conditions. COUP-TFII, chicken ovalbumin

upstream promoter-transcription factor II; EC, endothelial cell;

EndMT, endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition; ETC, electron

transport chain; Ang-1, angiopoietin-1; EMT,

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; CVD, cardiovascular disease;

CRC, colorectal cancer; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension. |

Based on published reports (46,108) and the aforementioned

descriptions, chronic inflammation is involved in both CVDs and CRC

(Fig. 2). As previously mentioned

(46), COUP-TFII is key to

maintain endothelial homeostasis. In adult vascular ECs, it

represses the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as

CXCL10, CXCL11 and CCL5), while supporting the expression of

anti-thrombotic genes, such as TFPI2. Loss or reduced expression of

COUP-TFII can lead to an inflammatory endothelial state, triggering

EndMT, which contributes to atherosclerosis and other vascular

pathologies (46). In the tumor

microenvironment of CRC, chronic inflammation is a known driver of

cancer progression (108).

COUP-TFII appears to serve a dual role, depending on the cellular

context. In some CRC cells, overexpression of COUP-TFII promotes

tumor-suppressive signaling by upregulating p53 and PTEN while

inhibiting Akt (82), which can

help reduce inflammation. However, in other contexts, increased

COUP-TFII expression, especially when upregulated by miRNAs such as

miR-21, can promote EMT through activation of inflammatory

pathways, thereby enhancing tumor invasiveness (3,89,90).

Oxidative stress serves an important role in both

CVDs and CRC (Fig. 2). In the

heart and vasculature, COUP-TFII is involved in the regulation of

mitochondrial function. Upregulation in cardiac tissues has been

associated with defects in the ETC, and a reduction in the

expression of mitochondrial quality control genes (such as Mfn1,

Mfn2, Opa1 and Pink1). This leads to the accumulation of damaged

mitochondria and impaired ROS scavenging, culminating in elevated

oxidative stress, a key factor in heart failure and vascular

disease progression (69). While

the study by Wu et al (69)

is pivotal in terms of mechanistic exploration using transgenic

mouse models of DCM, some limitations should be addressed. First,

the cardiac-specific effects of COUP-TFII may not be directly

generalizable to other tissues, including the colon. Second,

although the mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress were

associated with COUP-TFII levels, direct causality and

dose-response relationships were not fully established,

particularly with respect to downstream disease phenotypes. In CRC,

oxidative stress within the tumor microenvironment can promote

genetic instability and tumor progression (109). However, lack of direct evidence

associating COUP-TFII with ROS regulation in CRC leaves the

proposed relationship speculative. To the best of our knowledge,

the majority of the existing data, including the aforementioned

study by Yang et al (109), focus on general mechanisms of ROS

in cancer, and do not specifically implicate COUP-TFII. Therefore,

while it is plausible that regulation of metabolic and

mitochondrial pathways by COUP-TFII could indirectly influence ROS

levels in CRC, this hypothesis remains unvalidated in CRC-specific

in vivo models. Further research using CRC-specific

conditional knockout or overexpression models is essential to

clarify whether COUP-TFII modulates oxidative stress in the colon

epithelium or tumor microenvironment and whether this mechanism

contributes causally to colorectal tumorigenesis.

COUP-TFII regulates angiogenesis, affecting the

progression of both CVDs and CRC (Fig.

2). COUP-TFII positively regulates angiogenic factors such as

Ang-1 by binding to its promoter (often in cooperation with Sp1),

which supports vessel stability and maturation (46). This function is key for normal

vascular repair and to prevent pathological calcification (46). In CRC, COUP-TFII modulates the

balance between pro- and anti-angiogenic signals. By influencing

the expression of factors that control angiogenesis, COUP-TFII can

impact tumor vascularization (17,20).

Depending on the cellular context, this modulation may either

suppress or promote tumor progression.

COUP-TFII also regulates energy metabolism,

influencing both cardiac function and cancer cell proliferation

(Fig. 2). COUP-TFII regulates

various genes such as GLUTt4, PPARα, fatty acid binding

protein 3 and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 involved in both

fatty acid and glucose metabolism (3,5).

Upregulation of COUP-TFII in cardiac tissues has been associated

with the downregulation of key metabolic regulators, such as PGC-1α

and Sod2, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired energy

production and ultimately heart failure (69). In CRC, COUP-TFII can influence

metabolic pathways through its effects on the Akt signaling cascade

and by altering the expression of enzymes involved in glycolysis

(5). This metabolic dysregulation

provides the energetic and biosynthetic requirements for rapid

tumor cell proliferation, thereby contributing to cancer

progression.

Therapeutic implications of COUP-TFII in

CVDs

Vascular interventions using grafts are often

required to treat severe CVDs (110). However, traditional grafts face

challenges, such as susceptibility to infection, thrombogenicity

and poor long-term patency rates (111–113). Recent advances in vascular

biology underscore the key role of COUP-TFII in regulating

endothelial identity and angiogenesis, protecting against

atherosclerosis, and mitigating vascular calcification (114). Xing et al (114) demonstrated that COUP-TFII

overexpression following the localized delivery of COUP-TFII pDNA

nanocarriers (COUP-TFII@HPEI) in a rat abdominal artery replacement

model regulated stem/progenitor cell differentiation towards

endothelialization, and inhibited the calcification of

decellularized allografts. This presents an effective strategy to

enhance the applicability of decellularized allografts for vascular

interventions (114). However,

the limitations of this study include the use of a short-term

preclinical model, and the lack of long-term patency and immune

response data. Furthermore, the effect of COUP-TFII overexpression

on systemic metabolism and off-target tissues was not assessed. Wu

et al (69) revealed that

reducing the COUP-TFII expression in calcineurin

(CnTg/Cre/F+) transgenic mouse models that develop DCM

resulted in an increase in overall survival. Thus, inhibiting

COUP-TFII to restore the metabolic balance in the heart exhibits

potential as a therapeutic approach for heart failure, highlighting

the potential of COUP-TFII in CVD treatments. Nevertheless, there

are also limitations to this study, including its reliance on a

genetically engineered model with a strong calcineurin-dependent

phenotype, which may not generalize to other forms of heart

failure, and the use of global or tissue-specific knockouts without

temporal control of gene expression. Overall, these findings

emphasize the context-dependent effects of COUP-TFII: While its

overexpression may support vascular regeneration and graft

compatibility by enhancing endothelial reprogramming, it may

conversely exacerbate cardiac dysfunction when dysregulated in the

myocardium. This dichotomy emphasizes the importance of

spatiotemporal control in potential COUP-TFII-targeted therapies.

Additional studies are warranted to resolve these paradoxes,

validate the efficacy and safety in large-animal models or human

tissues, and establish optimal delivery strategies that minimize

off-target effects, while leveraging the therapeutic potential of

the gene of interest.

Therapeutic implications of COUP-TFII in

CRC

The role of COUP-TFII in CRC remains controversial.

Therefore, targeting COUP-TFII in CRC requires further exploration.

In tumor-promoting contexts of COUP-TFII, small molecules or

RNA-based therapies targeting COUP-TFII are anticipated to show

promise, according to previous preclinical models such as prostate

cancer xenograft models and patient-derived xenograft mice

(115). Qin et al

(20) revealed that the inhibition

of COUP-TFII via conditional ablation in a mouse xenograft model

resulted in impaired neoangiogenesis and suppressed tumor growth.

Although this study provided a mechanistic explanation for the

angiogenic role of COUP-TFII, its dependence on immune-deficient

mouse models may limit translational relevance, particularly in the

context of tumor-immune interactions (20). Additionally, Wang et al

(116) revealed that COUP-TFII

knockdown attenuated tumorigenesis and tumor progression in an

immunocompetent mouse glioblastoma model, indicating that COUP-TFII

may have a broader oncogenic function in various types of cancer.

However, the results are still based on a tumor type-specific model

and lack CRC-specific validation. Wang et al (115) identified a small molecular

inhibitor of COUP-TFII using a luminescence-based cell-based

high-throughput screening assay, and also revealed that this

inhibitor reduced prostate cancer cell proliferation, colony

formation, cell invasion and angiogenesis in xenograft mouse models

and patient-derived xenograft models. Although promising, the

selectivity, bioavailability and toxicity profiles of the compound

were not fully addressed, and its effects in CRC models remain

unknown. These findings support the rationale for developing

COUP-TFII-targeted agents, particularly in tumors with COUP-TFII

upregulation. Similarly, targeting COUP-TFII to inhibit

angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming may suppress tumor

progression. To the best of our knowledge, no clinical trials

specifically targeting COUP-TFII have been carried out; however,

related nuclear receptor-targeting compounds, such as retinoic acid

receptor agonists (117) and HDAC

inhibitors (40), are being

investigated in cancer therapy and may provide insights into

potential COUP-TFII-targeted approaches.

On the other hand, there is evidence that COUP-TFII

expression is associated with certain positive prognostic

indicators in CRC, suggesting its potential role as a tumor

suppressor (80,81). Therefore, extensive prospective

studies are necessary to reconcile these conflicting observations.

Kruse et al (18) reported

the potential of retinoic acids as COUP-TFII promoters using

multiple cell line experiments; however, the required concentration

was greater than the physiological levels of retinoic acids,

raising concerns regarding clinical feasibility. In

tumor-suppressive contexts, developing novel drugs that can enhance

COUP-TFII expression may provide novel therapeutic avenues for CRC

treatment.

In terms of synergy with existing treatments (for

example, doxorubicin or 5-fluorouracil), COUP-TFII modulation has

the potential to enhance the efficacy of standard chemotherapy and

targeted therapies (118). For

example, several studies have suggested that COUP-TFII modulates

Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β signaling pathways, including EMT, both of

which are responsible for resistance to conventional CRC treatments

(84,89,118). In particular, the reduction of

COUP-TFII after doxorubicin treatment may contribute to EMT-induced

doxorubicin resistance in CRC cells (118), supporting the possibility that

COUP-TFII upregulation can lead to chemosensitivity to doxorubicin

in CRC. Taken together, combining COUP-TFII modulators with

conventional Wnt pathway inhibitors or immune checkpoint inhibitors

may improve treatment responses in resistant tumors by hindering

resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, given the role of COUP-TFII in

angiogenesis and metastasis, its inhibition could complement

anti-angiogenic therapies, such as VEGF inhibitors, by preventing

tumor vascularization and dissemination (17,20).

However, challenges remain in translating these findings into

clinical applications.

Future research directions

There are several challenges in research that

should be overcome in developing COUP-TFII-related therapies for

CVDs and CRC. One major concern is the lack of well-characterized

small-molecule inhibitors or modulators that can specifically

target COUP-TFII without affecting other nuclear receptors.

Additionally, the dual role of COUP-TFII as both an oncogene and

tumor suppressor in different contexts complicates therapeutic

strategies for CRC, underscoring the need to investigate potential

biomarkers to identify patients who would benefit from

COUP-TFII-targeted interventions. Furthermore, the development of

selective COUP-TFII modulators, optimization of drug delivery

systems and comprehensive preclinical validation are necessary

steps before clinical trials can be pursued.

Therefore, future research should focus on

elucidating the precise regulatory mechanisms of COUP-TFII,

identifying specific patient subgroups that would benefit from

COUP-TFII-targeted therapies, carrying out human clinical trials

based on previous preclinical experimental data, exploring

combination strategies to enhance treatment efficacy while

minimizing toxicity, and developing personalized treatments based

on these findings. Structural studies on the LBD of COUP-TFII may

help identify novel therapeutic ligands or modulators.

Investigating the interactions of COUP-TFII with key signaling

molecules, such as VEGF and PGC-1α, could further help identify

potential therapeutic targets. Additionally, understanding the

interaction between COUP-TFII-related CVDs and CRC will be key to

develop integrated therapeutic approaches. For example,

longitudinal studies examining the bidirectional risk between CVDs

and CRC could provide valuable insights into their shared

pathophysiological mechanisms. Biomarker-based approaches to

monitor COUP-TFII activity could also guide tailored treatment

strategies for patients with coexisting CVDs and CRC.

Conclusion

COUP-TFII is a versatile transcription factor with

key roles in both CVDs and CRC. Its structural features and

regulatory mechanisms enable it to affect diverse cellular

processes, from angiogenesis to metabolism. Future studies should

aim to uncover the tissue-specific roles of COUP-TFII in various

pathological contexts, develop selective modulators of COUP-TFII

for clinical applications, and explore the interplay between

COUP-TFII-mediated pathways in CVDs and CRC. Comprehensive

understanding of the dual roles of COUP-TFII in CRC and its

interrelation with CVDs, will provide opportunities for innovative

therapeutic strategies that target this nuclear receptor.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Research

Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (grant

no. 2022R1A2C1009739) and the Basic Science Research Program

through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (grant no.

2022R1I1A1A01072409).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

THP and JIP were responsible for conception,

organization, searching the literature, writing of the first draft

and reviewing the manuscript. SHH, JGC, SJP and JYH searched the

literature and reviewed the manuscript. SHH and JIP designed the

figures. Data authentication is not applicable. All authors have

read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AF

|

activation function

|

|

Ang-1

|

angiopoietin-1

|

|

APOB

|

apolipoprotein B

|

|

BMP4

|

bone morphogenic protein 4

|

|

CCL

|

C-C motif chemokine ligand

|

|

ChIP

|

chromatin immunoprecipitation

|

|

COUP-TFII

|

chicken ovalbumin upstream

promoter-transcription factor II

|

|

CVD

|

cardiovascular disease

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

CXCL

|

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand

|

|

DBD

|

DNA-binding domain

|

|

DCM

|

dilated cardiomyopathy

|

|

DIHF

|

diabetes-induced heart failure

|

|

DR

|

direct repeat

|

|

EC

|

endothelial cell

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition

|

|

EndMT

|

endothelial-to-mesenchymal

transition

|

|

ERG

|

ETS-related gene

|

|

ETC

|

electron transport chain

|

|

HDAC

|

histone deacetylase

|

|

HIF

|

hypoxia-inducible factor

|

|

Mfn

|

mitofusin

|

|

miR

|

microRNA

|

|

NRCM

|

neonatal rat cardiomyocyte

|

|

Opa1

|

optic atrophy 1

|

|

PA

|

palmitic acid

|

|

PAH

|

pulmonary arterial hypertension

|

|

PFKFB3

|

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphophatase 3

|

|

PGC-1α

|

peroxisome proliferator activated

receptor γ coactivator-1α

|

|

Pink1

|

PTEN-induced kinase 1

|

|

PPAR

|

peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor

|

|

RAS

|

renin-angiotensin system

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

Shh

|

sonic hedgehog

|

|

SMRT

|

silencing mediator for retinoid or

thyroid hormone receptor

|

|

Sod2

|

superoxide dismutase 2

|

|

Sp1

|

specificity protein 1

|

|

SRC-1

|

steroid receptor coactivator-1

|

|

TCF7L2

|

T-cell factor 7-like 2 or

transcription factor 7-like 2

|

|

TFPI2

|

tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2

|

|

Tie-2

|

tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin

like and EGF like domains-2

|

|

UTR

|

untranslated region

|

|

aa

|

amino acids

|

References

|

1

|

Wang LH, Tsai SY, Cook RG, Beattie WG,

Tsai MJ and O'Malley BW: COUP transcription factor is a member of

the steroid receptor superfamily. Nature. 340:163–166. 1989.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tsai SY and Tsai MJ: Chick ovalbumin

upstream promoter-transcription factors (COUP-TFs): Coming of age.

Endocr Rev. 18:229–240. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Polvani S, Pepe S, Milani S and Galli A:

COUP-TFII in health and disease. Cells. 9:1012019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pereira FA, Tsai MJ and Tsai SY: COUP-TF

orphan nuclear receptors in development and differentiation. Cell

Mol Life Sci. 57:1388–1398. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ashraf UM, Sanchez ER and Kumarasamy S:

COUP-TFII revisited: Its role in metabolic gene regulation.

Steroids. 141:63–69. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pereira FA, Qiu Y, Tsai MJ and Tsai SY:

Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF):

Expression during mouse embryogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

53:503–508. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pereira FA, Qiu Y, Zhou G, Tsai MJ and

Tsai SY: The orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII is required for

angiogenesis and heart development. Genes Dev. 13:1037–1049. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wu SP, Cheng CM, Lanz RB, Wang T, Respress

JL, Ather S, Chen W, Tsai SJ, Wehrens XH, Tsai MJ and Tsai SY:

Atrial identity is determined by a COUP-TFII regulatory network.

Dev Cell. 25:417–426. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lin FJ, You LR, Yu CT, Hsu WH, Tsai MJ and

Tsai SY: Endocardial cushion morphogenesis and coronary vessel

development require chicken ovalbumin upstream

promoter-transcription factor II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

32:e135–e146. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

You LR, Lin FJ, Lee CT, DeMayo FJ, Tsai MJ