Introduction

As a prominent global health concern, infertility

affects 8–12% of couples in the reproductive age group (between 15

and 49 years, with 50% being due to male-infertility-associated

factors associated with abnormal semen parameters (1,2).

Male infertility can be caused by congenital hypoplasia and

varicocele (3). Its pathogenesis

is usually caused by genetic and environmental factors (4). Studies have focused on key genes and

signaling pathways that regulate male reproduction (5–8), but

there is still controversy regarding this issue.

Sirtuins (SIRTs), highly conserved nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent deacetylases, are involved in

gene regulation, metabolism, aging and cancer (9). In mammals, seven types of SIRT, 1–7,

have been identified with distinct structures, cellular

localization and tissue expression (10). SIRTs are highly expressed in

mammalian testicular tissue; to the best of our knowledge, few

studies have evaluated the role of SIRTs in male reproductive

function (11–13). SIRT2 has been implicated in

regulating cell cycle progression and apoptosis in germ cells

during spermatogenesis (14,15).

Dysfunction of SIRT3 is associated with impaired sperm motility and

increased sperm DNA damage, highlighting its role in maintaining

sperm function (11,16,17).

Loss of SIRT6 in mice results in an elevated number of apoptotic

spermatids (18).

SIRT5 is a NAD-dependent desuccinylase, demalonylase

and deacetylase protein (19).

SIRT5 participates in a number of biological processes, including

the urea cycle, fatty acid oxidation and amino acid metabolism

(20). It also serves a key role

in cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms by activating

mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 (21,22).

In addition, via regulation of DNA repair proteins, such as

ATP-dependent DNA helicase 2 subunit Ku70-like protein, SIRT5

contributes to the maintenance of genomic integrity and protection

against DNA damage-induced cellular dysfunction (23). The multifaceted functions of SIRT5

underscore its role in cell physiology, including maintaining

metabolic homeostasis (22),

regulating stress responses (24)

and ensuring genomic stability (23). However, the specific functions and

mechanisms of SIRT5 in spermatogenic cells remain to be

explored.

The present study aimed to investigate the effects

of SIRT5 on GC-2 spd cells and its underlying mechanisms to

contribute to the development of more effective therapeutic

strategies for asthenospermia.

Materials and methods

Human semen sample collection

The present human study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shenzhen Ethics Review Committee on Biomedical

Research (Shenzhen, China) [(2023) approval no. 001]. All

participants provided written informed consent to participate. The

subjects were patients who were treated in Peking University

Shenzhen Hospital from July 2023 to January 2024. The present study

included 25 male patients aged between 22 and 45 years with

asthenozoospermia (sperm concentration, ≥15 million cells/ml;

progressive motility, <32%; total motility, <40%;

morphologically normal forms, ≥4%) and 25 participants with normal

semen parameters. Semen samples were collected by masturbation

following 3–7 days of abstinence. Samples were evaluated by

computer-assisted semen analysis (version SSA-II, Suijia Software

Co., Ltd) system. Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

aged between 20 and 45 years with complete clinical data and ii) no

syphilis, hepatitis, acquired immune deficiency syndrome or other

infectious disease. Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Patients

with genitourinary tract infection; ii) patients with a history of

recent use of drugs that interfere with sperm or semen quality and

iii) malignant tumor or abnormal liver and kidney function.

Database mining

To compare the expression of SIRT5 among

asthenozoospermic, asthenoteratozoospermic and normal sperm from

fertile individuals, mRNA expression data was retrieved from the

GEO database (accession no. GSE160749)

(ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/?acc=GSE160749). In addition, the

protein expression of SIRT5 in testicular cells was queried using

the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database

(proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000124523-SIRT5/single+cell+type).

Animals

A single male C57BL/6 J wildtype mouse (age, 2

months; weight, 22 g) was obtained from the Nanjing University

Experimental Animal Institute (Nanjing, China). The mouse was

housed in a specific-pathogen-free animal facility (22°C, 55%

humidity) with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle and free access to

standard food and water. Health and behavior were monitored every

day. The duration of the experiment was 20 weeks. Humane endpoints

were as follows: Complete anorexia or signs of depression

accompanied by hypothermia (body temperature <37°C) without

anesthesia or sedation. The mouse was euthanized by intraperitoneal

injection of an overdose of 1% pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg).

Animal death was confirmed by respiratory and cardiac arrest and

pupil dilation was observed for ≥10 min. All animals were treated

according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources for the National

Research Council. The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shenzhen Peking University-Hong Kong University of

Science and Technology Medical Center (approval no. 2021-007).

Immunofluorescence staining

After the mouse was euthanized, the testicles were

dissected and removed. Testes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 15–20 h at room temperature and dehydrated using a fully

automatic tissue dehydrator (Excelsior AS; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The samples were embedded in paraffin using an

embedding machine (HistoStar; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and

sectioned to 3–5 µm thickness. Sections were deparaffinized in

xylene at room temperature, rehydrated using descending ethanol

concentrations, immersed in 0.01 M citrate buffer (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.) at 100°C for 10 min to facilitate antigen

retrieval, and cooled for 2–3 h at room temperature. Sections were

washed three times for 5 min each at room temperature with PBS

(Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Sections were blocked with

5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Merck KGaA) at room temperature for

1h. Sections were incubated with SIRT5 (1:100; Cat. No. 15122-1-AP,

Proteintech Group, Inc.) and γH2AX (1:100; ab26350, Abcam) in a

humid environment at 4°C overnight. Sections were washed in PBS and

incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibody (1:100; Invitrogen;

cat. # A-11008 and Cat. # A32742, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

for 1 h at room temperature and treated with

VECTASHIELD® antifading mounting agent containing DAPI

(Vector Laboratories, Inc.) for 10 min at room temperature.

Sections were observed under a confocal microscope (STELLARIS 5;

Leica GmbH).

To observe the mitochondrial staining, the GC-2 spd

cells were cultivated in glass coverslips for 24 h and stained with

Mito-Tracker red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 30 min, all

at 37°C. Cells were blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h and incubated with

SIRT5 (1:100) for 1 h at room temperature and sealed with DAPI,

then observed under the confocal laser scanning microscope.

Cell culture

GC-2 spd cell line was procured from the American

Type Culture Collection. Cells were maintained in a

25-cm2 petri dish with DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine

serum (both Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 100 U/ml

penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5%

CO2.

Plasmid transfection

GC-2 spd cells at 60–70%. GC-2 spd cells were

transfected with 3 µg/ml pCDNA3.1-SIRT5 plasmid (Sangon Biotech Co.

Ltd.) using LipofectamineTM 3000 Transfection Reagent

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated in 5%

CO2 at 37°C for 8 h to overexpress (OE) SIRT5. Cells

transfected with 3 µg/ml pCDNA3.1 plasmid (Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd.)

were used as a control. Cells were treated in a 5% CO2

incubator at 37°C for 48 h before subsequent experiments.

Small interfering (si)RNA transfection. SIRT5 and

negative control siRNAs were synthesized by Suzhou GenePharma. The

antisense sequences (5′→3′) were as follows: Negative control,

ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT; SIRT5 siRNA-1, CCAGUUGUGUUGUAGACGATT and

SIRT5 siRNA-2, GGCUCGUCCAAGUUCAAAUTT. When the cell density reached

~30% confluency, 1 µg/ml SIRT5 and control siRNAs were transfected

into GC-2 spd cells. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5%

CO2 for 48 h before subsequent experiments.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from sperm samples and

1×106 GC-2 spd cells using SteadyPure RNA extraction kit

(Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). According to the

manufacturer's protocol, the extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed

into cDNA using Evo M-MLV RT Mix Tracking kit with gDNA Clean for

qPCR (Hunan Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). qPCR was

carried out using SYBR Green Premix Pro Taq HS qPCR kit (Hunan

Accurate Bio-Medical Technology Co., Ltd.). The following

thermocycling conditions were used: 95°C for 30 sec, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The housekeeping gene

GAPDH was used as an internal control for normalization. RT-qPCR

was performed out using a two-step process. The 2−ΔΔCq

method was employed to evaluate the relative expression of the

target genes (25). The primers

are listed in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used in reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Target | Forward, 5′→3′ | Reverse, 5′→3′ |

|---|

| SIRT5 (human) |

GGCACTTCCTCTGTGGTG |

CGTAGCTGGGGTGGTCT |

| SIRT5 (mouse) |

AAGCACATAGCCATCATCTC |

CCCTCCGGTAGTGGTAAA |

| GAPDH (human) |

CCACTCCTCCACCTTTGACG |

CTGGTGGTCCAGGGGTCTTA |

| GAPDH (mouse) |

AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA |

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously

described (17). The antibodies

were as follows: Anti-β-actin (1:10,000; cat. No. 66009-1-IG,

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-SIRT5 (1:5,000; Cat. No. 15122-1-AP,

Proteintech Group, Inc.), anti-PI3K (1:1,000; Cat. # 13666, Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-AKT (1:1,000; Cat. no. 9272, Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.,), anti-phosphorylated (p-)AKT (1:1,000;

Cat. # 4060, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), anti-Bax (1:1,000;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) and anti-Bcl-2 (1:1,000; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). The secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit

(1:2,000; Cat. #7074, Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). and

anti-mouse IgG (1:2,000; Cat. #7076, Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

CCK-8 assay (Dojindo Molecular Technologies Inc.)

was performed to evaluate cellular viability. Transfected GC-2 spd

cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 3,000

cells/well. A volume of 10 µl CCK-8 (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) was added to the DMEM and incubated at 37°C for 2 h.

Subsequently, the optical density at 450 nm was measured every 24 h

using a Multiskan Go plate reader (Beckman Coulter, Inc.).

EdU assay

An EdU incorporation assay was carried out with the

EdU cell proliferation kit (cat. no. C0078L, Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology). Sterilized slides were placed in a 24-well plate

and transfected cells were seeded into each well at a density of

30%. After culturing with 50 µmol/l EdU reagent for 2 h at room

temperature, slides were washed with PBS and fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature (Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology). After staining the nucleus with DAPI, the cells

were imaged and photographed with a confocal laser scanning

microscope.

Wound healing assay

Cell migration was detected using a wound healing

assay. 5×105 transfected cells were plated in a 6-well

plate and cultured to 90% confluency. Subsequently, monolayers were

scratched with a 200 µl pipette tip and washed with PBS. The medium

was replaced with a serum-free DMEM and images were captured 0 and

24 h by a Lecia DMi8 fluorescence microscope. All cells were grown

at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Apoptosis assay

An apoptosis assay was performed using Annexin V,

633 Apoptosis Detection kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.). In brief,

after digestion with trypsin, the cells were centrifuged at 700 × g

for 2 min at 4°C, washed twice with PBS and resuspended in binding

buffer at a final density of 1×106 cells/ml. Annexin

V-633 and PI (5 µl each) were added to 100 µl cell suspension. The

cell suspension was mixed and incubated for 15 min at room

temperature in the dark. A total of 200 µl binding buffer was added

and cells were measured by flow cytometry using Calibur (BD Accuri

C6 Plus; BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using BD Accuri C6

Plus software (version 1.0.264.21; BD Biosciences) and the

apoptotic rate was calculated as the percentage of early (Annexin

V-FITC) + late apoptotic (Annexin V-FITC and PI) cells.

Co-immunoprecipitation

A total of 1×107 GC-2 cells were lysed in

1 ml NP-40 buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) containing

protease inhibitor cocktail, centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at

4°C, and the supernatant was removed for use. 1 ml lysates were

incubated with PI3K (1:100; Cat. # 13666, Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.), FLAG (1:200; Cat. No. 20543-1-AP, Wuhan Sanying

Biotechnology) or mouse IgG (1:100; sc-515946, Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.) antibody for 12 h at 4°C and incubated with 20

µl Pierce Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The beads were washed with PBST

(0.1% Tween-20) and incubated at 95°C for 10 min in 1× loading

buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The beads were

separated using a magnetic rack and the supernatant was used for

Western blotting, as aforementioned.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8

(Dotmatics). The results from three experiments are reported as

mean ± standard deviation. Student's unpaired t-test was employed

for comparisons between two independent groups, while one-way ANOVA

followed by the Tukey's post hoc test was used to assess

significance between >2 groups. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

SIRT5 is downregulated in

asthenozoospermia and asthenoteratozoospermia

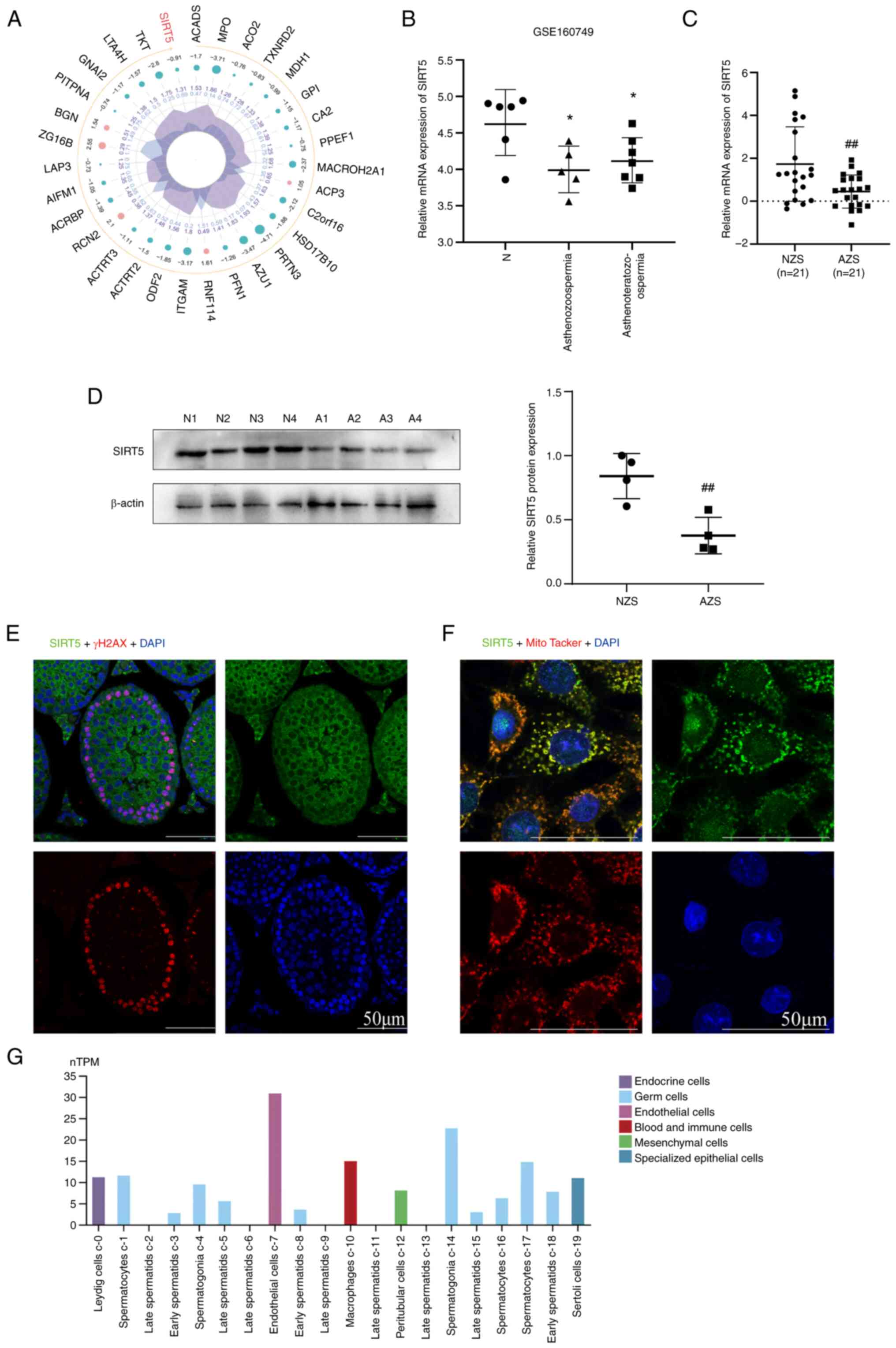

In our previous study, proteomic analysis revealed

that SIRT5 was downregulated in asthenozoospermia compared with

normal sperm samples (Fig. 1A)

(26). In addition, the expression

levels of SIRT5 were assessed in asthenozoospermia,

asthenoteratozoospermia and normal sperm from fertile men by

downloading the data from the GEO database (GSE160749). SIRT5

expression was significantly downregulated in asthenozoospermia and

asthenoteratozoospermia spermatozoa compared with normal (Fig. 1B). We obtained samples from

clinical patients and the basic semen parameters in normal and

asthenozoospermic patients are described in Table II. Furthermore, expression of

SIRT5 was assessed in normal and asthenozoospermia sperm samples,

which revealed that its mRNA and protein expression was

significantly downregulated in asthenozoospermia sperm samples

(Fig. 1C and D).

| Table II.Basic semen parameters in patients

with asthenozoospermia and healthy controls. |

Table II.

Basic semen parameters in patients

with asthenozoospermia and healthy controls.

| Variable | Control |

Asthenozoospermia | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 31.44±3.98 | 32.60±3.42 | 0.4594 |

| Sperm count,

×106 sperm/ml | 94.72±21.05 | 80.20±40.31 | 0.1169 |

| Volume, ml | 4.28±1.17 | 4.30±1.07 | 0.9499 |

| Total motility,

% | 77.24±5.72 | 26.40±9.05 | <0.0001 |

| Progressive

motility, % | 66.72±7.04 | 13.44±6.16 | <0.0001 |

SIRT5 is expressed in the testis and

primarily expressed in mitochondria in spermatocytes

To determine the SIRT5 expression in the testicular

tissue, immunofluorescence analysis was conducted using testicular

tissue from a 2-month-old wild-type mouse. Analysis revealed

widespread expression of SIRT5 in testicular tissue, including its

presence in spermatocytes (Fig.

1E). This was congruent with the expression profile of SIRT5 in

the HPA database (Fig. 1G). In the

mouse spermatocyte cell line GC-2 spd, SIRT5 was mainly localized

to mitochondria (Fig. 1F).

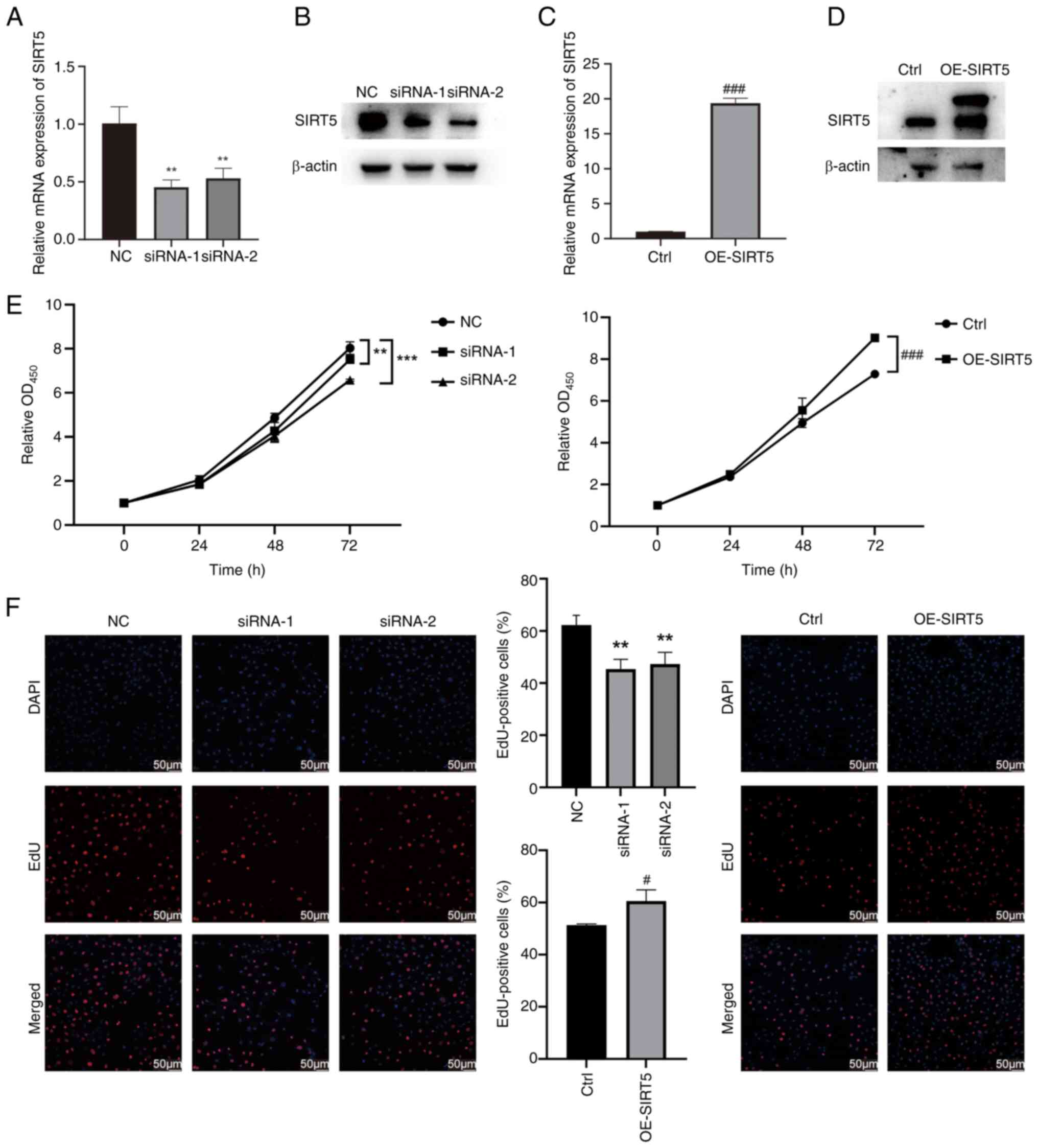

SIRT5 promotes the proliferation of

GC-2 spd cells

Both gain- and loss-of-function assays were

performed to further elucidate the biological function of SIRT5 in

GC-2 spd cells. GC-2 spd cells were infected with lentivirus

harboring pLV-SIRT5 or siRNAs for SIRT5 knockdown. The efficacy of

SIRT5 modulation in GC-2 spd cells was evaluated by RT-qPCR and

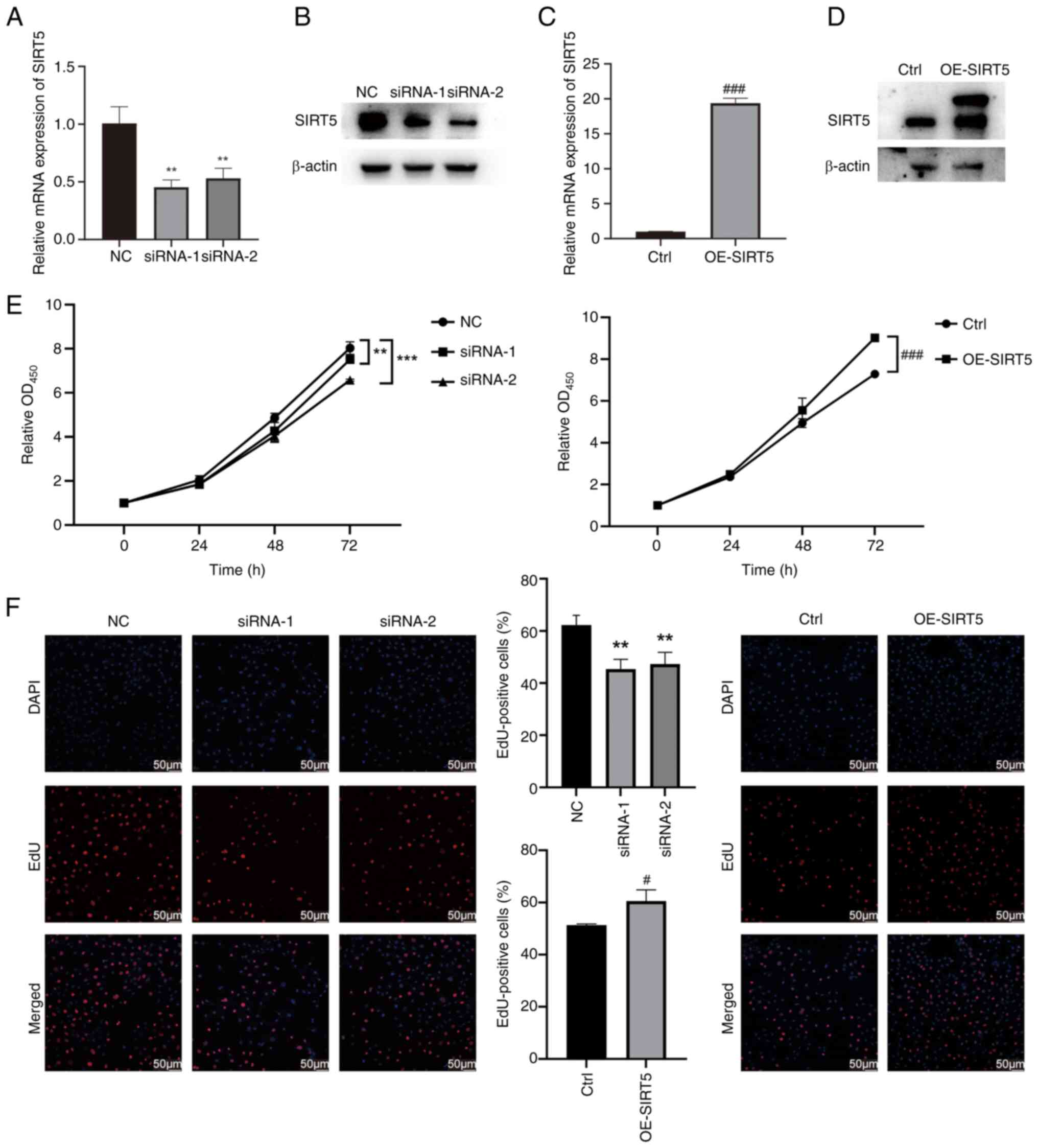

western blot analysis (Fig. 2A-D).

CCK-8 assays revealed the viability of OE-SIRT5 GC-2 spd cells

increased compared with the vector control group (Fig. 2E). Conversely, knockdown of SIRT5

in GC-2 spd cells decreased viability (Fig. 2E). EdU assay revealed that SIRT5

knockdown inhibited cell proliferation while OE-SIRT5 increased

cell proliferation (Fig. 2F).

These results suggested that SIRT5 promoted the proliferation of

GC-2 spd cells.

| Figure 2.Knockdown of SIRT5 inhibits

proliferation of GC-2 spd cells. Following transfection with

siRNAs, SIRT5 expression was suppressed in GC-2 spd cells at both

(A) transcriptional and (B) translational levels. After infection

with OE-SIRT5 lentivirus, SIRT5 expression was markedly increased

in GC-2 spd cells at both (C) transcriptional and (D) translational

levels. (E) Viability of GC-2 spd cells treated with siRNAs or

lentivirus. (F) EdU assays revealed the proliferation capacity of

GC-2 spd cells treated with siRNAs or lentivirus. **P<0.01,

***P<0.001 vs. NC; #P<0.05,

###P<0.001 vs. Ctrl. Ctrl, control; si, small

interfering; NC, negative control; OD, optical density; SIRT5,

sirtuin 5; OE, overexpression. |

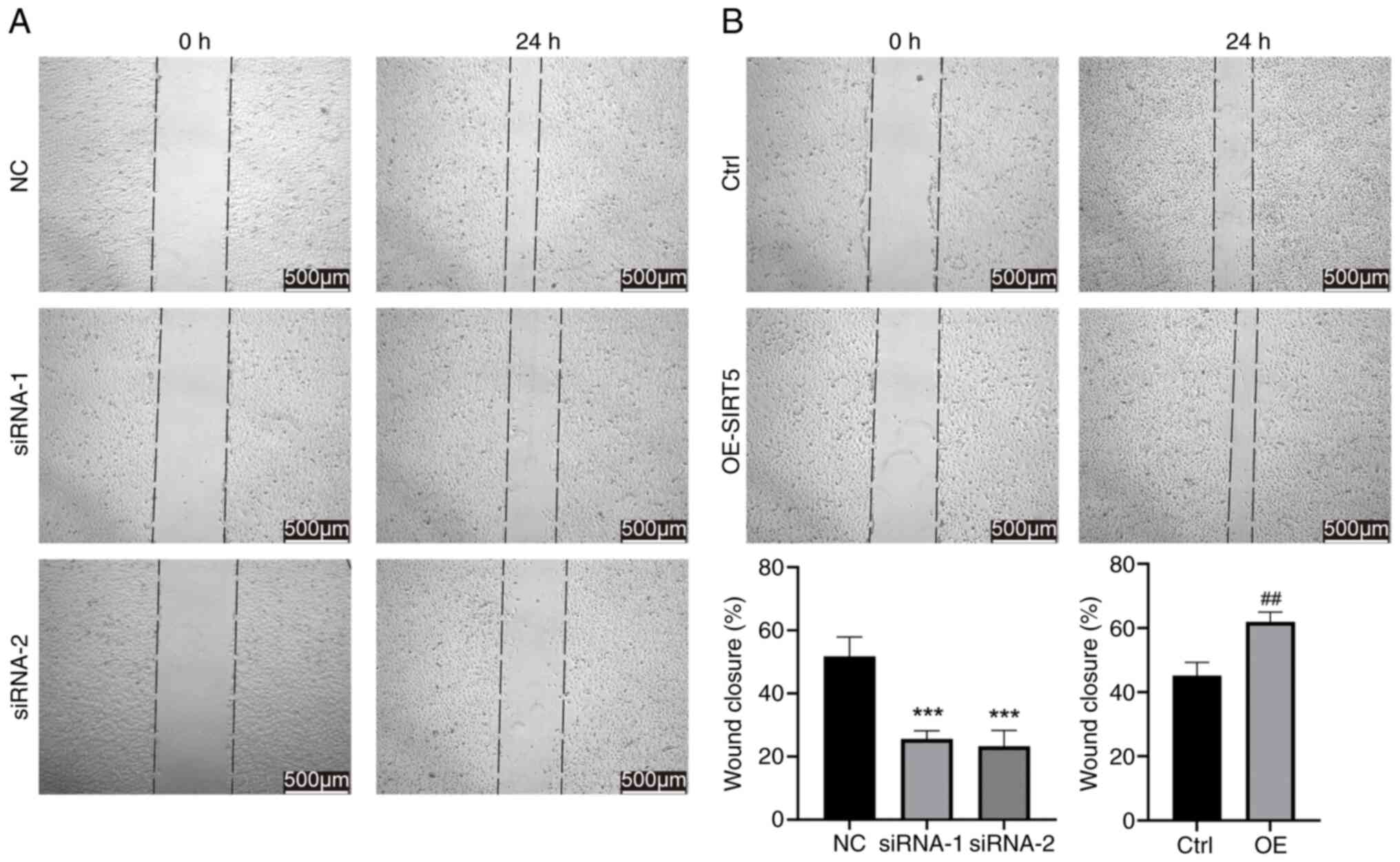

SIRT5 facilitates the migration of

GC-2 spd cells

Wound healing assay was performed to investigate the

effects of SIRT5 on the motility of GC-2 spd cells. Knockdown of

SIRT5 significantly impaired the migratory capacities of GC-2 spd

cells (Fig. 3A), whereas OE

increased migration (Fig. 3B).

SIRT5 inhibits apoptosis of GC-2 spd

cells

To determine the effects of SIRT5 on apoptosis in

GC-2 spd cells, flow cytometry was used. Notably, the proportion of

apoptotic cells was significantly elevated in the SIRT5 knockdown

compared with the control group (Fig.

4A). Conversely, the proportion of apoptotic cells with

OE-SIRT5 significantly decreased (Fig.

4B).

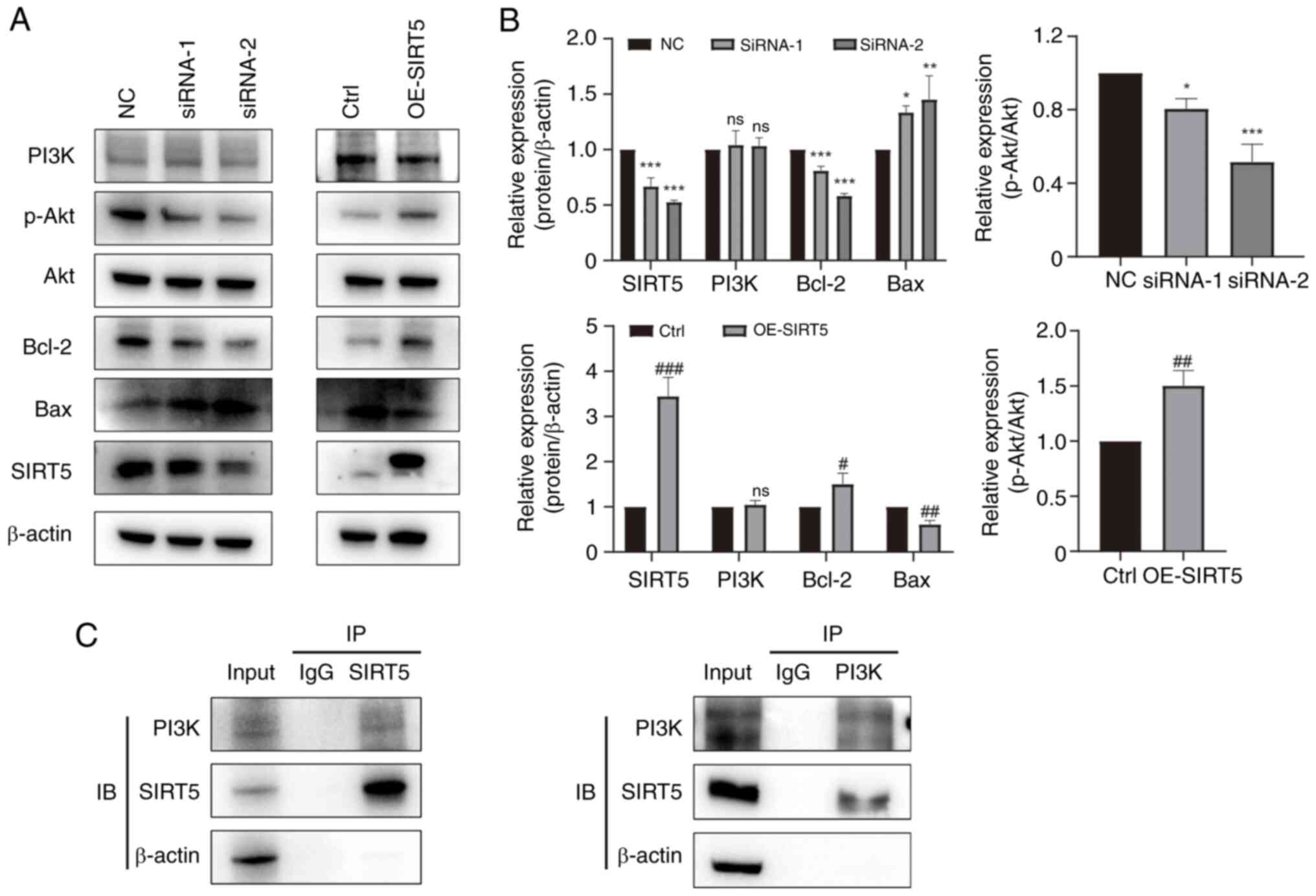

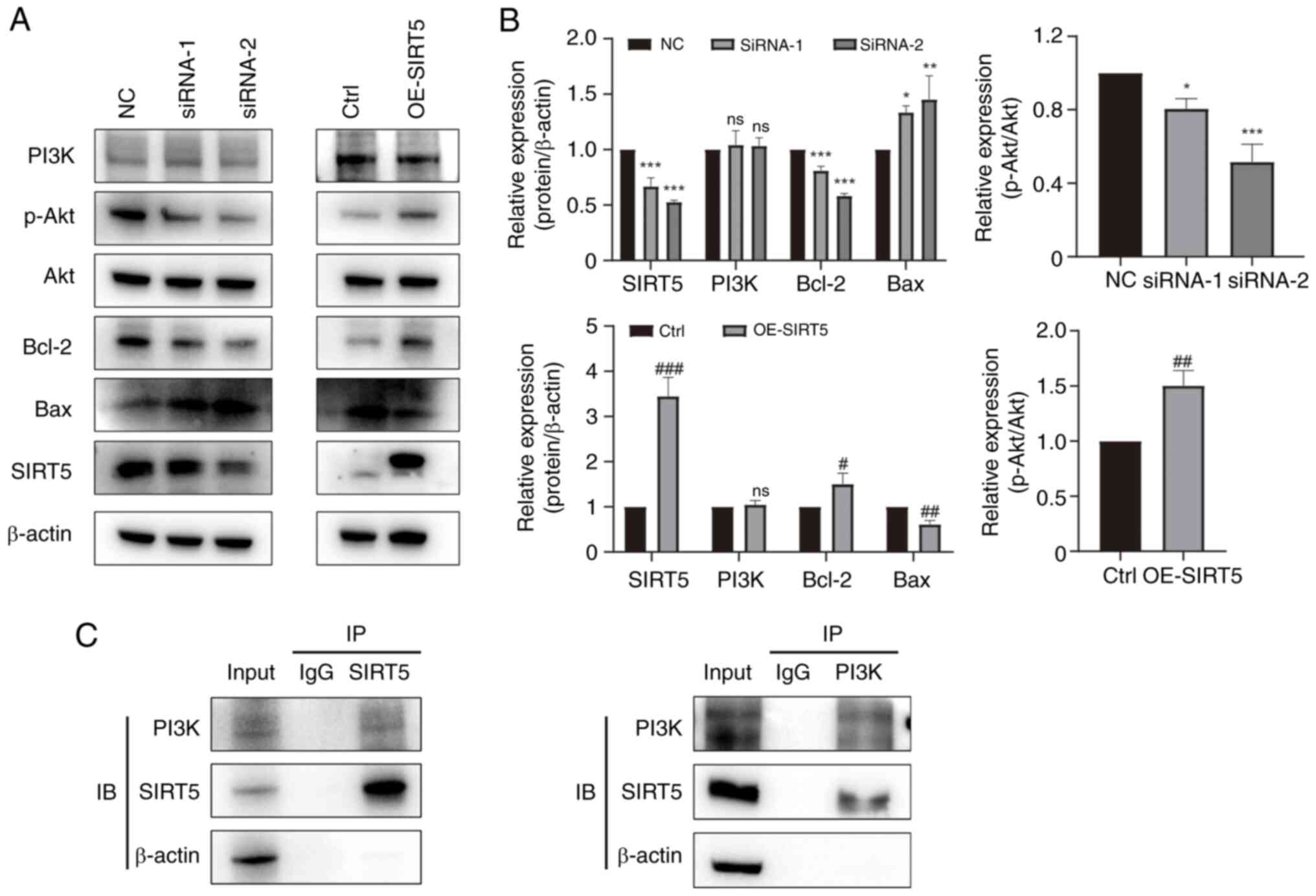

SIRT5 promotes the proliferation of

GC-2 spd cells via the PI3K/AKT pathway

To clarify the molecular mechanism underlying

regulation of proliferation and apoptosis by SIRT5 in GC-2 spd

cells, western blotting was performed. Knockdown of SIRT5

suppressed the expression of Bcl-2 and p-AKT, but promoted the

expression of Bax (Fig. 5A and B).

Conversely, OE-SIRT5 markedly enhanced the expression of Bcl-2 and

p-AKT, while decreasing expression of Bax (Fig. 5A and B). To explore how SIRT5

regulates the PI3K/AKT pathway, the binding of SIRT5 to PI3K was

assayed using co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 5C). SIRT5 could bind with PI3K,

which might inhibit the phosphorylation of PI3K/AKT signaling

members.

| Figure 5.SIRT5 regulates the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway in GC-2 spd cells. (A) Western blot analysis of

PI3K, p-AKT, AKT, Bcl-2, Bax and SIRT5 in GC-2 spd cells treated

with siRNA or lentivirus. (B) Semi-quantitative analysis of western

blot results. (C) Co-IP using a PI3K and FLAG antibody on GC-2 spd

cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01,

###P<0.001 vs. Ctrl. p-, phosphorylated; SIRT5,

sirtuin 5; Ctrl, control; NC, negative control; ns, not

significant; siRNA, small interfering RNA; OE, overexpression; IB,

immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation. |

Discussion

The causes of male infertility are complicated, and

its pathogenesis is unclear (27).

The process of spermatogenesis is regulated by factors including

energy metabolism, signaling pathways, and REDOX processes, to

ensure normal viability and fertilization ability (28,29).

Our previous proteomic analysis revealed that SIRT5 is

significantly downregulated in asthenozoospermic sperm (26); this finding was validated in human

sperm samples. However, the specific function of SIRT5 in male germ

cells has not been validated. To the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to demonstrate the role of SIRT5 in

inhibiting apoptosis and promoting sperm cell proliferation and

migration in vitro. The present study revealed that SIRT5

was involved in proliferation of GC-2 spd cells by regulating the

PI3K/AKT pathway.

Both the aforementioned proteomics results and

analysis of data from the GEO database revealed that SIRT5 was

significantly downregulated in asthenozoospermia compared with

normal motile sperm, which was also confirmed by RT-qPCR in human

sperm samples. These findings aligned with those reported in

previous studies (30,31). SIRT5 was expressed in the testis

and mainly localized in the mitochondria in the mouse spermatogenic

cell line. Loss of SIRT5 leads to mitochondrial membrane potential

defects and oxidative stress damage (32–34),

which can interfere with sperm motility (35,36).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that SIRT5 has an important role in

maintaining the normal movement of mature sperm.

The present study revealed that knockdown of SIRT5

decreased viability and proliferation and increased apoptosis of

GC-2 spd mouse spermatocytes. Previous research has reported that

SIRT5 participates in cellular processes through its regulation of

the PI3K/AKT pathway (37). This

pathway serves a key role in governing spermatogonial stem cell

self-renewal and spermatogonial proliferation (38). Therefore, we explored the

relationship between SIRT5 and the PI3K/AKT pathway and found that

the interaction between SIRT5 and PI3K was responsible for

inhibiting the phosphorylation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

members. Studies have revealed that the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

inhibits sperm apoptosis, accompanied by a decrease in the

expression of Bax (39,40), which is consistent with the

findings of the present study. In addition, inhibiting the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway decreases the expression of premeiotic and

meiotic markers in the testes of postnatal and adult mice (41), whereas activation of PI3K/AKT

signaling promotes meiotic entry (42). Meiosis is a complex process that

begins in the primary spermatocyte and requires several proteins

and enzymes (43). Abnormal

meiosis has a marked effect on both sperm count and quality,

increasing the risk of infertility (44,45).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that SIRT5 may be an important gene

affecting male infertility via the regulation of PI3K/AKT

pathway.

SIRT5 has low deacetylation activity but strong

desuccinylation, demalonylation and deglutarylation activities

(18,19). For example, SIRT5 regulates the

malonylation of GAPDH and succinylation of pyruvate kinase M2

(46,47) and isocitrate dehydrogenase 2

(48) to alter their activity,

thereby participating in the regulation of glycolysis and the

tricarboxylic acid cycle. It was hypothesized that altered SIRT5

expression may cause disturbances in energy metabolism and

homeostasis via these metabolic changes, which in turn would affect

germ cell proliferation and apoptosis. Especially in mature sperm,

ATP is primarily produced through glycolysis to maintain sperm

motility. Therefore, it was hypothesized that changes in SIRT5

expression in sperm would exert an effect on sperm motility by

influencing the glycolytic pathway (49). In addition, SIRT5 interacts with

PI3K, therefore, SIRT5 may affect the PI3K/AKT pathway through the

regulation of the protein modifications. However, further studies

are needed to clarify the role of SIRT5 post-translational

modification in regulation of spermatogenesis and sperm

viability.

The present study revealed that SIRT5 is associated

with sperm motility, and served an important role in maintaining

the viability and proliferation of GC-2 cells and decreasing

apoptosis. The results of the present study are important for a

comprehensive understanding of the mechanism and treatment of male

infertility. However, the lack of in vivo data to assess how

SIRT5 affects infertility warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by Guangdong Basic and Applied

Basic Research Foundation (grant no. 2025A1515012758), Shenzhen

Postdoctoral Research Start-Up Fund and Science Technology, the

Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (grant no.

JCYJ20200109140212277), the Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen

(grant no. SZSM202111011) and the Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline

Construction Fund (grant no. SZXK051)..

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HX performed experiments and data analysis. HX, SC

and MW constructed figures, data interpretation, and wrote the

manuscript. HX, TZ and BY designed, supervised the study, and

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. TZ and BY provided

financial support. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experiments strictly followed the ‘Helsinki

Declaration’ and obtained ethical approval from the Ethics

Committee of Shenzhen Ethics Review Committee on Biomedical

Research (Shenzhen, China) [approval no. (2023) 001]. All patients

signed written informed consent. All animal protocols were in

accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shenzhen Peking University-Hong Kong University of

Science and Technology Medical Center (Shenzhen, China) (approval

no. 2021-007).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

NAD

|

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

|

|

GEO

|

Gene Expression Omnibus

|

|

HPA

|

Human Protein Atlas

|

|

siRNA

|

small interfering RNA

|

|

RT-q

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

|

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

SIRT

|

sirtuin

|

References

|

1

|

Agarwal A, Baskaran S, Parekh N, Cho CL,

Henkel R, Vij S, Arafa M, Panner Selvam MK and Shah R: Male

infertility. Lancet. 397:319–333. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liu S, Yu H, Liu Y, Liu X, Zhang Y, Bu C,

Yuan S, Chen Z, Xie G, Li W, et al: Chromodomain Protein CDYL Acts

as a Crotonyl-CoA Hydratase to regulate histone crotonylation and

spermatogenesis. Mol Cell. 67:853–866.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Esteves SC and Agarwal A: Afterword to

varicocele and male infertility: Current concepts and future

perspectives. Asian J Androl. 18:319–322. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Maurya S, Kesari KK, Roychoudhury S,

Kolleboyina J, Jha NK, Jha SK, Sharma A, Kumar A, Rathi B and Kumar

D: Metabolic dysregulation and sperm motility in male infertility.

Adv Exp Med Biol. 1358:257–273. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xu C, Tang D, Shao Z, Geng H, Gao Y, Li K,

Tan Q, Wang G, Wang C, Wu H, et al: Homozygous SPAG6 variants can

induce nonsyndromic asthenoteratozoospermia with severe MMAF.

Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 20:412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zhuang BJ, Xu SY, Dong L, Zhang PH, Zhuang

BL, Huang XP, Li GS, You YD, Chen D, Yu XJ and Chang DG: Novel

DNAH1 mutation loci lead to multiple morphological abnormalities of

the sperm flagella and literature review. World J Mens Health.

40:551–560. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Akbari A, Pipitone GB, Anvar Z, Jaafarinia

M, Ferrari M, Carrera P and Totonchi M: ADCY10 frameshift variant

leading to severe recessive asthenozoospermia and segregating with

absorptive hypercalciuria. Hum Reprod. 34:1155–1164. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cao N, Hu C, Xia B, He Y, Huang J, Yuan Z,

Deng J and Duan P: The Activated AMPK/mTORC2 signaling pathway

associated with oxidative stress in seminal plasma contributes to

idiopathic asthenozoospermia. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2022:42404902022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mei Z, Zhang X, Yi J, Huang J, He J and

Tao Y: Sirtuins in metabolism, DNA repair and cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 35:1822016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kratz EM, Sołkiewicz K, Kubis-Kubiak A and

Piwowar A: Sirtuins as important factors in pathological states and

the role of their molecular activity modulators. Int J Mol Sci.

22:6302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Dhillon VS, Shahid M, Deo P and Fenech M:

Reduced SIRT1 and SIRT3 and lower antioxidant capacity of seminal

plasma is associated with shorter sperm telomere length in

oligospermic men. Int J Mol Sci. 25:7182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Iniesta-Cuerda M, Havránková J, Řimnáčová

H, García-Álvarez O and Nevoral J: Male SIRT1 insufficiency leads

to sperm with decreased ability to hyperactivate and fertilize.

Reprod Domest Anim. 57 (Suppl 5):S72–S77. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ye F, Wu L, Li H, Peng X, Xu Y, Li W, Wei

Y, Chen F, Zhang J and Liu Q: SIRT1/PGC-1α is involved in

arsenic-induced male reproductive damage through mitochondrial

dysfunction, which is blocked by the antioxidative effect of zinc.

Environ Pollut. 320:1210842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Feng YQ, Liu X, Zuo N, Yu MB, Bian WM, Han

BQ, Sun ZY, De Felici M, Shen W and Li L: NAD(+) precursors promote

the restoration of spermatogenesis in busulfan-treated mice through

inhibiting Sirt2-regulated ferroptosis. Theranostics. 14:2622–2636.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhang L, Hou X, Ma R, Moley K, Schedl T

and Wang Q: Sirt2 functions in spindle organization and chromosome

alignment in mouse oocyte meiosis. FASEB J. 28:1435–1445. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Nasiri A, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rahimi Z,

Bakhtiari M, Bahrehmand F, Kiani A, Mozafari H and Pourmotabbed T:

Evaluation of the relationship among the levels of SIRT1 and SIRT3

with oxidative stress and DNA fragmentation in

asthenoteratozoospermic men. Int J Fertil Steril. 15:135–140.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang Z, Zhu C, Song Y, Chen X, Zheng J, He

L, Liu X and Chen Z: SIRT3 inhibition suppresses hypoxia-inducible

factor 1α signaling and alleviates hypoxia-induced apoptosis of

type B spermatogonia GC-2 cells. FEBS Open Bio. 13:154–163. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Wei H, Khawar MB, Tang W, Wang L, Wang L,

Liu C, Jiang H and Li W: Sirt6 is required for spermatogenesis in

mice. Aging (Albany NY). 12:17099–17113. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Du J, Zhou Y, Su X, Yu JJ, Khan S, Jiang

H, Kim J, Woo J, Kim JH, Choi BH, et al: Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent

protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science.

334:806–809. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Park J, Chen Y, Tishkoff DX, Peng C, Tan

M, Dai L, Xie Z, Zhang Y, Zwaans BM, Skinner ME, et al:

SIRT5-mediated lysine desuccinylation impacts diverse metabolic

pathways. Mol Cell. 50:919–930. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Greene KS, Lukey MJ, Wang X, Blank B,

Druso JE, Lin MJ, Stalnecker CA, Zhang C, Negrón Abril Y, Erickson

JW, et al: SIRT5 stabilizes mitochondrial glutaminase and supports

breast cancer tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

116:26625–26632. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ji Z, Liu GH and Qu J: Mitochondrial

sirtuins, metabolism, and aging. J Genet Genomics. 49:287–298.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang HL, Chen Y, Wang YQ, Tao EW, Tan J,

Liu QQ, Li CM, Tong XM, Gao QY, Hong J, et al: Sirtuin5 protects

colorectal cancer from DNA damage by keeping nucleotide

availability. Nat Commun. 13:61212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen XF, Tian MX, Sun RQ, Zhang ML, Zhou

LS, Jin L, Chen LL, Zhou WJ, Duan KL, Chen YJ, et al: SIRT5

inhibits peroxisomal ACOX1 to prevent oxidative damage and is

downregulated in liver cancer. EMBO Rep. 19:e451242018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yang J, Liu Q, Yu B, Han B and Yang B:

4D-quantitative proteomics signature of asthenozoospermia and

identification of extracellular matrix protein 1 as a novel

biomarker for sperm motility. Mol Omics. 18:83–91. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Eisenberg ML, Esteves SC, Lamb DJ,

Hotaling JM, Giwercman A, Hwang K and Cheng YS: Male infertility.

Nat Rev Dis Primers. 9:492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

de Kretser DM, Loveland KL, Meinhardt A,

Simorangkir D and Wreford N: Spermatogenesis. Hum Reprod. 13 (Suppl

1):1–8. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Guo J, Nie X, Giebler M, Mlcochova H, Wang

Y, Grow EJ; DonorConnect, ; Kim R, Tharmalingam M, Matilionyte G,

et al: The dynamic transcriptional cell atlas of testis development

during human puberty. Cell Stem Cell. 26:262–276.e4. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Janiszewska E, Kokot I, Kmieciak A,

Stelmasiak Z, Gilowska I, Faundez R and Kratz EM: The association

between clusterin sialylation degree and levels of

oxidative-antioxidant balance markers in seminal plasmas and blood

sera of male partners with abnormal sperm parameters. Int J Mol

Sci. 23:105982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Di Emidio G, Falone S, Artini PG,

Amicarelli F, D'Alessandro AM and Tatone C: Mitochondrial sirtuins

in reproduction. Antioxidants (Basel). 10:10472021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Yang L, Peltier R, Zhang M, Song D, Huang

H, Chen G, Chen Y, Zhou F, Hao Q, Bian L, et al:

Desuccinylation-triggered peptide self-assembly: Live cell imaging

of SIRT5 activity and mitochondrial activity modulation. J Am Chem

Soc. 142:18150–18159. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Boylston JA, Sun J, Chen Y, Gucek M, Sack

MN and Murphy E: Characterization of the cardiac succinylome and

its role in ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

88:73–81. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Shen H and Ong C: Detection of oxidative

DNA damage in human sperm and its association with sperm function

and male infertility. Free Radic Biol Med. 28:529–536. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kurkowska W, Bogacz A, Janiszewska M,

Gabryś E, Tiszler M, Bellanti F, Kasperczyk S, Machoń-Grecka A,

Dobrakowski M and Kasperczyk A: Oxidative stress is associated with

reduced sperm motility in normal semen. Am J Mens Health.

14:15579883209397312020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gill K, Machałowski T, Harasny P,

Grabowska M, Duchnik E and Piasecka M: Low human sperm motility

coexists with sperm nuclear DNA damage and oxidative stress in

semen. Andrology. 12:1154–1169. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Choi SY, Jeon JM, Na AY, Kwon OK, Bang IH,

Ha YS, Bae EJ, Park BH, Lee EH, Kwon TG, et al: SIRT5 directly

inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway in prostate cancer cell lines. Cancer

Genomics Proteomics. 19:50–59. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen KQ, Wei BH, Hao SL and Yang WX: The

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway: How does it regulate development of

Sertoli cells and spermatogenic cells? Histol Histopathol.

37:621–636. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Ding N, Zhang Y, Huang M, Liu J, Wang C,

Zhang C, Cao J, Zhang Q and Jiang L: Circ-CREBBP inhibits sperm

apoptosis via the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway by sponging miR-10384

and miR-143-3p. Commun Biol. 5:13392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Xu Y, Fan Y, Fan W, Jing J, Xue K, Zhang

X, Ye B, Ji Y, Liu Y and Ding Z: RNASET2 impairs the sperm motility

via PKA/PI3K/calcium signal pathways. Reproduction. 155:383–392.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sahin P, Gungor-Ordueri NE and

Celik-Ozenci C: Inhibition of mTOR pathway decreases the expression

of pre-meiotic and meiotic markers throughout postnatal development

and in adult testes in mice. Andrologia. 50:May 10–2017.(Epub ahead

of print).

|

|

42

|

Deng CY, Lv M, Luo BH, Zhao SZ, Mo ZC and

Xie YJ: The Role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway in male

reproduction. Curr Mol Med. 21:539–548. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ishiguro KI: Mechanisms of meiosis

initiation and meiotic prophase progression during spermatogenesis.

Mol Aspects Med. 97:1012822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wang Y, Wu Y and Zhang S: Impact of

bisphenol-A on the spliceosome and meiosis of sperm in the testis

of adolescent mice. BMC Vet Res. 18:2782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zhao J, Lu P, Wan C, Huang Y, Cui M, Yang

X, Hu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Wang M, et al: Cell-fate transition and

determination analysis of mouse male germ cells throughout

development. Nat Commun. 12:68392021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang F, Wang K, Xu W, Zhao S, Ye D, Wang

Y, Xu Y, Zhou L, Chu Y, Zhang C, et al: SIRT5 desuccinylates and

activates pyruvate kinase M2 to block macrophage IL-1β production

and to prevent DSS-induced colitis in mice. Cell Rep. 19:2331–2344.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Wu N,

Asara JM and Cantley LC: Pyruvate kinase M2 is a

phosphotyrosine-binding protein. Nature. 452:181–186. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhou L, Wang F, Sun R, Chen X, Zhang M, Xu

Q, Wang Y, Wang S, Xiong Y, Guan KL, et al: SIRT5 promotes IDH2

desuccinylation and G6PD deglutarylation to enhance cellular

antioxidant defense. EMBO Rep. 17:811–822. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ford WC: Glycolysis and sperm motility:

Does a spoonful of sugar help the flagellum go round? Hum Reprod

Update. 12:269–274. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|