Introduction

Graves' disease (GD), Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT)

and other autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITDs) are organ-specific

autoimmune diseases that are more common than type 1 diabetes and

multiple sclerosis (1). The

thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), as a G protein-coupled

receptor (GPCR), serves a key role in regulating thyroid function

(2). Specific autoantibodies such

as thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies (TRAb) bind to

TSHR, inducing abnormal changes in thyroid function, which are the

fundamental causes of diseases such as GD and HT (3).

TSHR autoantibodies have stimulatory

thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSAb) that block TSHR-blocking

antibodies (TBAb) or neutral activity, and the different activities

of TRAb are associated with the progression of AITDs, leading to

the occurrence of clinically relevant diseases. TSAb serves a key

role in the development of GD, as it activates the adenylyl cyclase

signaling system upon binding with TSHR, leading to an abnormal

elevation of thyroid hormones (4).

Additionally, TSAb is not controlled by the physiological

hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid negative feedback loop. After TSAb

binds to TSHR, it causes the activation of the cAMP pathway and the

secondary activation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, which promotes

the proliferation of thyroid follicular cells and the excessive

synthesis and secretion of thyroxine, and ultimately leads to the

pathogenesis of GD (5). However,

TBAb blocks the binding of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) to

TSHR, causing hypothyroidism and subsequently inducing HT (6). The serum TRAb positivity rate reaches

80–90% in patients with newly diagnosed GD, and as treatment

progresses, TRAb titers change accordingly (5). The different activities of TRAb are

associated with the progression of AITDs, leading to the

interconversion between hyper- and hypothyroidism (7). At present, it is difficult to

distinguish and differentiate TSAb from TBAb in clinical tests,

which makes clinical diagnosis and treatment difficult. This also

poses challenges in monitoring the disease progression of a patient

and providing precise treatment (8). Therefore, it is key to differentiate

the active types of TRAb in the diagnosis and treatment of

autoimmune diseases, such as GD, HT and mucinous edema.

Different methods of detecting TRAb are being

investigated. Currently, competitive binding assays and bioassays

are used for TRAb detection. However, these binding assays cannot

distinguish between TSAb and TBAb, while bioassays measure the

functional activity of TRAb rather than simple binding (8). As a result, compared with binding

assays, bioassays can more accurately detect the different

activities of TRAb. However, bioassays are complex and

time-consuming, requiring the use of experimental equipment and

technicians to conduct cell experiments, so cannot be widely used

in clinical testing (9). Since

TSHR is the main autoantigen in the pathogenesis of GD and HT

[particularly the extracellular region of TSHR, which is the

cluster region of antigenic determinants, with the A subunit of

TSHR being the binding site for TSAb (10), and the B subunit of TSHR being the

binding site for TBAb, the interaction between TSHR and

thyroid-specific lymphocytes and TRAb induces the occurrence and

development of AITD (11).

Therefore, analysing the characteristics of AITD induced by the

combination of different domains of TSHR and its autoantibodies may

provide a novel approach for precise diagnosis, treatment and

prevention for patients.

Given the key role of TSHR and its antibody, TRAb,

in the occurrence, development and prognosis of AITDs, studies have

been conducted using cloning, sequence analysis and partial

crystallization to confirm that TSHR possesses unique structural

and functional characteristics (12–14).

TSHR is composed of extracellular domains (ECDs) and transmembrane

domains (TMD) involved in membrane-bound signal transduction

(15,16). The ECD structure contains

leucine-rich repeat domains [LRRDs; amino acid (aa)22-279], which

are rich in leucine (16). The

molecular activation mechanism of TSHR differs from that of other

GPCRs, as its ECD (aa1-418) is larger and primarily responsible for

specific binding with TSH and TRAb. The binding of TRAb or TSH to

TSHR can trigger conformational changes in the ECD, and TSAb or

TBAb can only bind to the ECD when the spatial conformation of TSHR

is correct. This interaction affects thyroid function and induces a

cascade of signal transduction via TMD leading to the development

of AITD (17,18). Therefore, understanding the

antigenic epitopes involved in the binding of TSHR to TSAb and TBAb

helps clarify the pathogenic mechanisms of GD, HT and other related

autoimmune diseases. In the present study, different fragments of

the TSHR ECD were designed to simulate their natural activity

through the preparation of fusion proteins. The pathogenic

antigenic epitopes of TSHR and their immunogenicity were explored

in both in vitro and in vivo experiments, with the

aim of understanding the specific binding sites between TSHR and

its pathogenic antibodies. The present study provided a scientific

basis for the development of detection methods for different types

of TRAb, the construction of disease animal models, and the

diagnosis and treatment of GD, HT and associated autoimmune

diseases.

Materials and methods

Serum samples and study

population

In the present study, a total of 120 patients (aged

18–56 years) and 30 healthy individuals (aged 18–52 years) were

recruited between January 2023 and January 2024 from The Second

Hospital and Clinical Medical School of Lanzhou University

(Lanzhou, China). Thyroid assessments were conducted for all

participants based on the guidelines outlined in ‘Thyroid disease:

assessment and management’ [National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE) guideline NG10074] released by NICE in 2019

(19). The assessments included

the medical history, clinical symptoms, physical examinations,

thyroid ultrasound and thyroid function tests [TSH, free

triiodothyronine (FT3) and free thyroxine (FT4)]. The exclusion

criteria included acute or chronic infections, other autoimmune or

chronic diseases, malignancies, hepatic or renal dysfunction,

pregnancy, lactation or the use of glucocorticoids, antibiotics,

and interferons or other medications affecting the immune system

and thyroid function.

The 120 patients were divided into four groups based

on their levels of TRAb [serum TRAb levels >1.5 IU/l measured by

chemiluminescence were considered to be positive. By combining TRAb

in serum with the TSHR-biotin-streptavidin-magnetic bead complex

(cat. no. 88817; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and then with the

alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-human IgG secondary antibody

(cat. no. PA1-85606; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; 1:10,000;

diluted in PBS; 2 h at room temperature)], chemiluminescence is

produced. The intensity of the chemiluminescence signal is

positively associated with the concentration of TRAb): 30 patients

with hyperthyroidism who were TRAb+ (age, 33.91±13.06

years; 10 male and 20 female patients), 30 patients with

hyperthyroidism who were TRAb− (age, 35.10±13.76 years;

9 male and 21 female patients), 30 patients with hypothyroidism who

were TRAb+ (age, 33.17±18.97 years; 11 male and 19

female patients), 30 patients with hypothyroidism who were

TRAb− (age, 37.4±16.86 years; 10 male and 20 female

patients). Furthermore, 30 healthy individuals were included as the

control group (age, 34.9±12.23 years; 12 male and 18 female

patients).

All patients were newly diagnosed and did not

receive any treatment, and all subjects had no thyroid nodules,

thyroid cancer or other thyroid changes. Individuals with other

complicating diseases, extrathyroidal manifestations or who

received medications such as steroids that may affect immune

function or thyroid function were excluded from the present study.

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical

Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University

(approval no. 2023A-802; Lanzhou, China). All participants provided

written informed consent prior to participating in the present

study.

Thyroid function and thyroid-specific

autoantibody testing

Fasting whole blood samples were collected from all

participants after an 8-h fast. Samples were analyzed at the

Department of Nuclear Medicine, Second Hospital of Lanzhou

University (Lanzhou, China), using a chemiluminescence immunoassay

to assess the levels of TSH (cat. no. 06491080; Siemens

Healthineers), FT3 (cat. no. 119781; Siemens Healthineers), FT4

(cat. no. 06490106; Siemens Healthineers), TG (cat. no. 11201760;

Siemens Healthineers), TPOAb (cat. no. 10630887; Siemens

Healthineers) and TRAb (cat. no. 130203009M; Shenzhen New

Industries Biomedical Engineering Co., Ltd.) in the serum. The kits

were all used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cloning of the human TSHR (hTSHR)

recombinant gene

The hTSHR gene sequence, protein amino acid sequence

and spatial structural characteristics were determined by querying

the Uniprot (https://www.uniprot.org/) and

National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) databases. Primers were

designed using Primer 3.0 (https://primer3.ut.ee/) according to the Champion™ pET

vector connection requirements and synthesized by Sangon Biotech

Co., Ltd. (Table I). The hTSHR

plasmid, preserved by the Endocrinology and Metabolism Laboratory

of Lanzhou University Second Hospital, and PrimeSTAR® HS

DNA polymerase [Takara Biomedical Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd.]

were used for PCR amplification of the target gene. PCR primer

(5′-3′) sequences were as follows: hTSHR410 forward,

CACCGGAATGGGGTGTTCGTCTCC and reverse, CACAATTCTCAGGAACTTGTAGCCCA;

hTSHR290 forward, CACCAAGAAAATCAGAGGAATCCT and reverse,

CACAATTCTCAGGAACTTGTAGCCCA; and hTSHR289 forward,

CACCATGAGGCCGGCGGA and reverse, CTGATTCTTAAAAGCACAGCAGTGGC. The

following thermocycling conditions were used: 98°C for 5 min,

followed by 30 cycles of 98°C for 10 sec, 55°C for 5 sec and 72°C

for 30–90 sec; 72°C for 5 min, followed by a 4°C hold. PCR

experiments were performed using the T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). Gene size was determined by 2% agarose gel

electrophoresis (visualization method, green fluorescent nucleic

acid dye; cat. no. G8140; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology

Co., Ltd.) and imaging (BluSight Pro; GD50502; Monad Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), and the purified gene was extracted using the Gene JET Gel

extraction kit (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

gene concentration was determined using a UV spectrophotometer.

According to the Champion™ pET102 Directional TOPO™ Expression Kit

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) requirements, the

purified and recovered hTSHR target gene was connected to

pET102-D-TOPO and transformed into competent TOP10 cells

[Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; TOP10 Escherichia

coli cells were cultured in S.O.C. medium (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 100 µg/ml ampicillin (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C] by adding 3

µl reaction mixture to 50 µl TOP10 cells (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The recovered bacterial liquid was spread onto

LB (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) solid

plates containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and incubated overnight at

37°C.

| Table I.Primer sequences. |

Table I.

Primer sequences.

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|

| hTSHR410 |

5′-CACCGGAATGGGGTGTTCGTCTCC-3′ |

3′-CACAATTCTCAGGAACTTGTAGCCCA-5′ |

| hTSHR290 |

5′-CACCAAGAAAATCAGAGGAATCCT-3′ |

3′-CACAATTCTCAGGAACTTGTAGCCCA-5′ |

| hTSHR289 |

5′-CACCATGAGGCCGGCGGA-3′ |

3′-CTGATTCTTAAAAGCACAGCAGTGGC-5′ |

Monoclonal colonies were picked out from the petri

dish, the picked colonies were mixed in sterile and enzyme-free

water, and then PCR was performed under the aforementioned PCR

reaction conditions. They were confirmed and identified using 2%

agarose gel electrophoresis (visualization method, green

fluorescent nucleic acid dye; cat. no. G8140; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and imaging (BluSight Pro;

GD50502; Monad Biotech Co., Ltd.). Positive colonies were

inoculated into LB liquid medium (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) with 100 µg/ml ampicillin (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and shaken overnight (37°C; 220

rpm), and plasmids were extracted from recombinant TOP10-hTSHR

cells using a plasmid mini-prep kit (TIANprep Mini Plasmid Kit;

cat. no. DP103; Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd.) according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

After collecting the bacteria, using the plasmid

mini-prep kit, Buffer P1 solution, Buffer P2 solution and Buffer P3

solution containing RNaseA were added sequentially, and the

supernatant was moved into the adsorption column CP3 and

centrifuged for 2 min at room temperature at 13,400 × g, and the

elution buffer EB was added dropwise to the middle part of the

adsorption membrane, and the recombinant plasmid solution

containing the target gene was collected into the centrifuge tube

after centrifugation for 2 min at room temperature at 13,400 × g.

Using a 3730×l DNA Analyzer (cat. no. A41046; Thermo Fisher

Scientific Inc.), the extracted recombinant plasmid was used as a

template, and the primers used were: Forward, TTCCTCGACGCTAACCTG

and reverse, TAGTTATTGCTCAGCGGTGG. In the 3730×l DNA Analyzer, the

plasmid to be tested first replicates DNA from the primer under the

catalysis of DNA polymerase until the reaction stops when it

encounters ddNTP. Then, the sequence of the DNA obtained from the

reaction is read by gel electrophoresis, and ultimately the gene

sequence of the plasmid to be tested is inferred (Sequencing

Analysis v7.1; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

Transformation of different hTSHR

recombinant plasmids into Escherichia coli for expression

Each TOP10-hTSHR recombinant plasmid was transformed

into Escherichia coli BL21Star™ (DE3) (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Following expansion culture, induction of

hTSHR fusion protein expression was carried out using 0.5 mmol/l

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). After 5 h of

induction at 25°C, the bacterial culture was collected. The cells

were resuspended in 1X PBS or binding buffer (20 mM sodium

phosphate; 0.5 M NaCl; 5 mM imidazole; pH 7.4). The cells were

disrupted using a cell disruptor, and the bacterial lysate was

centrifuged at 13,400 × g for 20 min at 4°C to collect the

supernatant and pellet. SDS-PAGE was conducted to determine the

expression of each hTSHR fusion protein, distinguishing between

expression in the supernatant and inclusion bodies. A total of 10

ng of protein was loaded per lane in a 10% gel.

Expression and purification of hTSHR

recombinant protein

Expression and purification of the hTSHR fusion

protein, tagged with histidine (His), were performed using a

Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) column. The process involved

collecting precipitated bacteria from LB culture following IPTG

induction. The collected cells were sonicated on ice (ultrasonic

power 200 W; 40 min), and the resulting mixture was subjected to

low-temperature centrifugation at 13,400 × g for 20 min at 4°C to

separate the precipitate and supernatant. The inclusion bodies in

the precipitate were dissolved in binding buffer (20 mM sodium

phosphate; 0.5 M NaCl; 5 mM imidazole; 8 M urea; pH 7.4). Following

centrifugation at 13,400 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the supernatant

containing the dissolved inclusion bodies was collected. This

supernatant was then combined with Ni-NTA and incubated for 1 h at

4°C. Similarly, the supernatant from the expression of the fusion

protein was also combined with Ni-NTA and incubated for 1 h at 4°C.

The inclusion bodies in the precipitate were dissolved in binding

buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate; 0.5 M NaCl; 5 mM imidazole; 8 M

urea; pH 7.4). Following centrifugation at 13,400 × g for 20 min at

4°C, the supernatant containing the dissolved inclusion bodies was

collected. This supernatant was then combined with Ni-NTA and

incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Similarly, the supernatant from the

expression of the fusion protein was also combined with Ni-NTA and

incubated for 1 h at 4°C. The inclusion body-expressed protein

underwent gradient renaturation in refolding buffer (20 mM sodium

phosphate; 0.5 M NaCl; 6-0 M urea gradient; pH 7.4). The purified

protein was concentrated using an ultrafiltration tube, and the

concentration of the purified fusion protein was determined using a

BCA assay kit. Subsequently, the complete amino acid sequences of

hTSHR410, hTSHR290 and hTSHR289 were imported into ExpaSy-ProtParam

software (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/), and various

physical and chemical parameters, including the molecular weight,

of the protein were calculated through the software analysis, and

the molecular weight of each fusion protein was estimated. The

predicted molecular weights of hTSHR289, hTSHR410 and hTSHR290 are

~47, 70 and 39 kDa respectively.

Western blot analysis

SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis were used to

characterize the three hTSHR fusion proteins purified in the

previous step. Proteins were extracted using the ultrasonic

disruption method (power 200 w; ultrasound was on for 2 sec and off

for 3 sec), and SDS-PAGE loading buffer (cat. no. P1040, Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to the

extracted proteins, which were boiled for 5–10 min. The

concentration of the protein was detected using a BCA protein

quantification kit. Each lane was loaded with 5 µg of protein.

Prepared samples (purified hTSHR fusion protein with protein

extraction buffer) were loaded into the sample wells of the

SDS-PAGE gel (10%) and electrophoresed at 120 V. The SDS-PAGE gel

was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.), or the proteins in the SDS-PAGE gel

were electrotransferred to a PVDF membrane (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The membrane was blocked with

5% non-fat powdered milk (cat. no. D8340; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 h. The PVDF

membrane was then blocked and incubated with antibodies, including

TSHR 3B12 (1:1,000; sc-53542; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; 4°C;

12 h) and His (1:1,000; 1B7G5; Proteintech Group, Inc.; 4°C; 12 h).

The next day, following incubation with secondary antibodies [Goat

Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (HRP); 1:10,000; ab205719; Abcam] for 2 h at

room temperature, visualization was carried out using ECL reagent

(Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) on an

automated chemiluminescence imager.

Direct ELISA using hTSHR fusion

protein as the antigen (hTSHR ELISA) and specificity

The three fusion proteins were coated as antigens on

the plate of enzymes. Following repeated experiments, it was

determined that coating with 1 µg/well of antigen at 4°C overnight

and blocking with 200 µl 1% BSA (Jiangsu Aidisheng Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.) per well at 37°C for 2 h were the optimal conditions.

Different serum samples were diluted in a gradient of 1:1,000

(optimized dilution ratio) and used as the primary antibody, with

100 µl diluted serum added per well. Duplicate test wells and

control wells were set up and then incubated at 37°C for 2 h.

Following the addition of 100 µl HRP-labeled antibody (1:10,000;

cat. no. D110150; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.), the plate was

incubated at 37°C for a further 2 h, followed by color development

with tetramethylbenzidine substrate for 15 min at 37°C. The

absorbance value at 450 nm was then determined using an ELISA

reader.

Animal study

A total of 48 female BALB/c mice aged 5–6 weeks and

weighing 20±2 g were obtained from Jiangsu Cavens Experimental

Animals Co., Ltd. The mice were housed under specific pathogen-free

conditions at the Experimental Animal Research Platform of The

Second Hospital of Lanzhou University. The mice were raised in a

specific pathogen-free environment, the temperature was 18–22°C and

the humidity was 50–60%, with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. The feed

was purchased from Beijing Keao Xieli Feed Co., Ltd. (cat. no.

1016706714625204224). The drinking water came from the experimental

animal research platform. Both the feed and water underwent

high-temperature and high-pressure sterilization treatment. Mice

had ad libitum access to food and water. Food, water, air,

bedding and all other supplies entering the animal center barrier

system were sterilized with high temperature and high pressure, and

were sterilized by irradiation through the transfer window before

entering and exiting the animal research platform. The mice were

randomly divided into 4 groups, with 12 mice in each group, which

were the hTSHR410 fusion protein immune mouse group, hTSHR289

fusion protein immune mouse group, hTSHR290 fusion protein immune

mouse group and normal saline control group. The animal experiments

received approval from the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of

The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (approval no. D2023-156;

Lanzhou, China). After reviewing the literature and combining the

test results of previous studies, mice were immunized with a 1:1

mixture of fusion protein injected at 4 points on the back of the

mice with complete Freund's adjuvant (the first injection) and

incomplete Freund's adjuvant (the second two injections) (20,21).

Each female BALB/c mouse was injected subcutaneously with 50 µg

hTSHR fusion protein at 4 points on the back, and the control group

was injected with normal saline. Three immunizations were given at

weeks 0, 3 and 6. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal

injection of sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and euthanized by

anesthesia overdose (intraperitoneal injection of sodium

pentobarbital; 100 mg/kg). The Animal Research: Reporting of In

Vivo Experiments guidelines were followed (22).

Mouse serum analysis

Blood was collected via cardiac puncture 2 weeks

after the completion of immunization under deep anesthesia (30

mg/kg sodium pentobarbital; intraperitoneal injection). The

extracted blood was placed in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and left to

stand at room temperature. Next, a centrifuge was set to 3,000 × g

and samples were centrifuged for 15 min at room temperature to

separate the serum, which was then stored at −20°C. The present

study utilized the thyroxine (T4) ELISA kit (cat. no. JL10849;

Shanghai Jonlnbio Industrial Co., Ltd.), the TSH ELISA kit (cat.

no. JM-11776M1; Jingmei Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and the TRAb ELISA

kit (cat. no. ZY-TRAb-MU; Zeye Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) to assess

the levels of TSH, T4 and TRAb in the serum of each group of mice.

A total of 10 µl of serum was extracted from each mouse in each

group. The serum was diluted by 1:4 using the sample dilution

solution in the aforementioned kits, and then the analysis was

carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Readings

were obtained at 450 nm using an ELISA reader. The procedure was

repeated three times for each assessment.

Histological analysis

Mice were euthanized using an overdose anesthetic

method (intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital; 100

mg/kg), and the thyroid glands were dissected. The thyroid tissue

was soaked in 4% paraformaldehyde for >48 h at room temperature.

After fixation, the tissues were dehydrated, sequentially soaked in

75% alcohol, 95% alcohol and absolute ethanol for gradient

dehydration, sequentially soaked in two xylenes (Tianjin Fuyu Fine

Chemical Co., Ltd.) and paraffin-embedded, and were then sectioned

using a Leica microtome (thickness, 5 µm; Leica Microsystems,

Inc.). Subsequently, the slices were placed in a baking machine and

baked at 75°C for 1 h. After deparaffinization, hematoxylin was

added dropwise to the slices and these were incubated at room

temperature for 5 min. Differentiation was performed by adding

hydrochloric acid ethanol dropwise to the slices and incubating at

room temperature for 3–5 sec. Finally, eosin solution was added

dropwise to the slices and the slices were incubated at room

temperature for 1–2 min. After the neutral gum was completely

dried, observations and scans were performed using a light

microscope.

Flow cytometry of T cell subsets

Following euthanasia, splenic tissues were retrieved

from the immunized mice and placed in 1640 culture medium (Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The spleen tissues were dissected

into small pieces using a surgical blade. Subsequently, the spleen

tissue was ground on a 100-mesh cell strainer to obtain a

single-cell suspension. Following centrifugation at 350 × g at 4°C

for 10 min, cells were collected, treated with red blood cell lysis

buffer at room temperature for 10 min, washed with PBS and then

centrifuged at 350 × g at 4°C for 10 min to obtain lymphocytes.

Lymphocytes (2×106 cells) were stained using

allophycocyanin (APC)/phycoerythrin (PE)/FITC markers. Cells were

analyzed using the CytoFLEX LX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter,

Inc.). Reported results were analyzed using the CytExpert software

(version 2.5; Beckman Coulter, Inc.) of the CytoFLEX LX flow

cytometer to characterize T cell subsets. The analyte detectors

were as follows: CD3+ antibody (cat. no. 565643; Becton,

Dickinson and Company), CD4+ antibody (cat. no.

F21004A02; Multi Sciences Biotech), CD8+ antibody (cat.

no. F2100801; Multi Sciences Biotech), CD25 antibody (cat. no.

E-AB-F1102C; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and CD122

antibody (cat. no. E-AB-F1029D; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology

Co., Ltd.). The analyte reporters were as follows: CD3+,

APC; CD4+, PE; CD8+, FITC; CD25, FITC; and

CD122, PE.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.0 software (Dotmatics) and SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp.).

Quantitative data with normal distribution are presented as the

mean ± standard deviation, while data with a skewed distribution

are presented as the median (quartile), and count data are

presented as absolute values or percentages. One-way ANOVA with

Tukey's post hoc test was used for comparisons of multiple groups

of parametric data. Categorical variables were compared using

χ2 tests to compare all groups and Bonferroni correction

was applied to the P-values. The Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's

post hoc test was used for non-parametric data. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All

experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Results

Different fusion proteins of

hTSHR

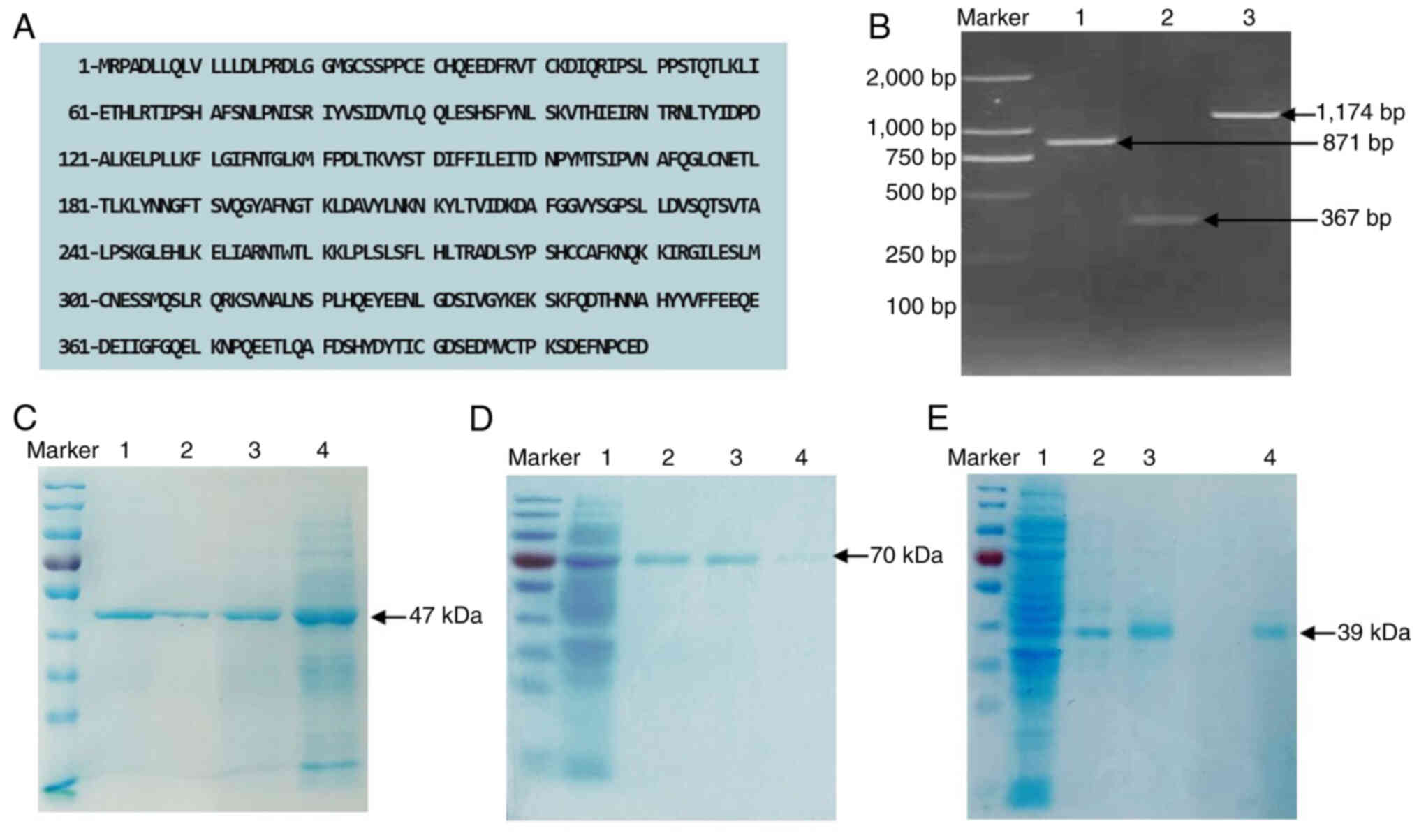

According to the full-length receptor gene sequence

of human TSHR, different hTSHR protein sequences were extracted:

hTSHR410, hTSHR289 and hTSHR290 (amino acid sequences shown in

Fig. 1A). The recombinant plasmid

was obtained by ligating the gene sequences corresponding to the

aforementioned hTSHR amino acid sequences with the vector. The

results of agarose gel electrophoresis after PCR amplification are

shown in Fig. 1B. Recombinant

plasmids with correctly framed reading sequences were selected for

expression in Escherichia coli, followed by induction with

IPTG, purification and visualization on SDS-PAGE gels, where three

distinct bands were observed (Fig.

1C-E). Based on SDS-PAGE, the molecular weight of the single

band in Fig. 1C was estimated to

be ~47 kDa, that of the single band in Fig. 1D was ~70 kDa and that of the single

band in Fig. 1E was ~39 kDa. These

results indicated that the purified proteins had molecular weights

consistent with the expected values, indicating that they were

hTSHR fusion proteins.

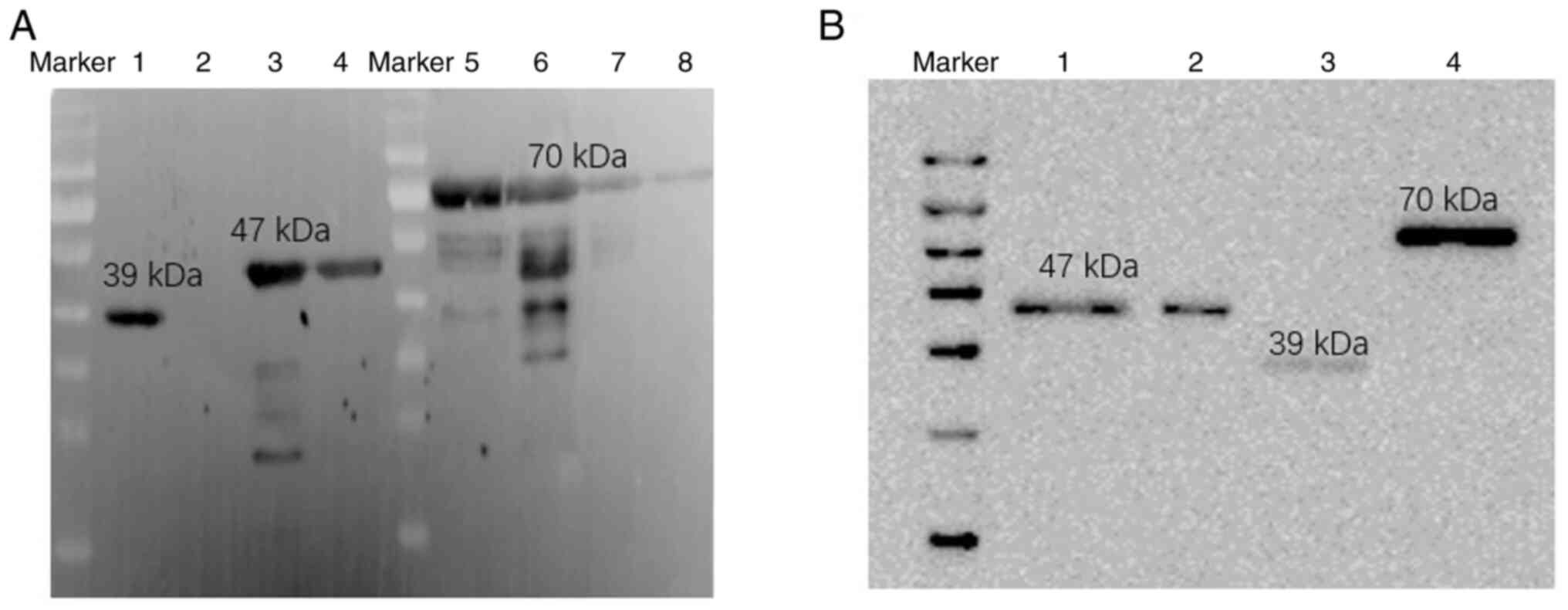

hTSHR fusion protein validation

Fusion proteins were expressed in the prokaryotic

system and single bands were obtained by SDS-PAGE after

purification. In order to accurately identify the three different

hTSHR fusion proteins, validation using western blotting was

performed. TSHR monoclonal antibody (3B12), His antibody and the

three different fusion proteins (hTSHR410, hTSHR289 and hTSHR290)

were assessed using western blotting. The results showed clear

protein bands at 70, 47 and 39 kDa (Fig. 2A and B). This demonstrated that the

purified fusion proteins were hTSHR fusion proteins.

Binding activity of different hTSHR

fusion proteins to an IgG antibody verified using an ELISA

In order to establish a convenient and stable method

for distinguishing the types of TRAb and to validate the biological

activity of the different hTSHR fusion proteins obtained, the age,

sex, and FT3, FT4, TSH and TRAb levels were analyzed in five groups

of recruited patients. There were no statistically significant

differences in the age or sex among the patients in each group.

This is summarized in Table

II.

| Table II.Clinical characteristics of all

subjects. |

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of all

subjects.

| Variable | Hyperthyroidism

(TRAb+) | Hyperthyroidism

(TRAb−) | Hypothyroidism

(TRAb+) | Hypothyroidism

(TRAb−) | Control | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 33.91±13.06 | 35.10±13.76 | 33.17±18.97 | 37.4±16.86 | 34.9±12.23 | 0.631a, 0.346b, 0.593c, 0.275d |

| Sex, n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Male | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 0.592a, 0.417b, 0.791c, 0.592d |

|

Female | 20 | 21 | 19 | 20 | 18 |

|

| FT3, pmol/l (normal

range, 2.77–6.31 pmol/l) | 15.19±9.23 | 13.67±4.80 | 2.29±1.71 | 1.87±0.99 | 4.13±1.35 | 0.012ae

0.030be, 0.021ce,

0.008de |

| FT4, pmol/l (normal

range, 10.44–24.38 pmol/l) | 41.99±16.21 | 38.28±14.32 | 4.12±3.48 | 3.85±2.52 | 16.61±3.50 | 0.035ae,

0.026be, 0.012ce,

0.007de |

| TSH, µIU/ml (normal

range, 0.38–4.34 µIU/ml) | 0.10 (0.10,

0.30) | 0.08

(0.06,0.40) | 68.09

(33.70,108.76) | 73.77

(41.43,116.29) | 2.64

(1.80,3.41) | 0.006ae,

0.007be, 0.036ce,

0.023de |

| TRAb, IU/l (normal

range, 0.00–60.00 U/ml) | 20.00 (11.00,

30.00) | 0.77

(0.36,1.15) | 16.64 (7.39,

30.00) | 0.54 (0.43,

0.61) | 0.38 (0.14,

1.07) | 0.008ae,

0.558b, 0.021ce,

0.642d |

| TG, ng/ml (normal

range, 1.00–39.00 ng/ml) | 601.56 (28.00,

1300.00) | 548.50 (30.60,

1300.00) | 572.04 (16.30,

1300.00) | 483.41 (21.00,

1300.00) | 15.70 (3.28,

35.40) | 0.016ae,

0.017be, 0.009ce,

0.006de |

| TPOAb, U/ml (normal

range, 0.0–1.5 IU/l) | 54.37 (0.50,

314.10) | 61.43 (0.20,

368.00) | 92.25 (2.00,

600.00) | 85.82 (0.63,

438.50) | 0.53 (0.00,

1.08) | 0.023ae,

0.037be, 0.018ce,

0.025de |

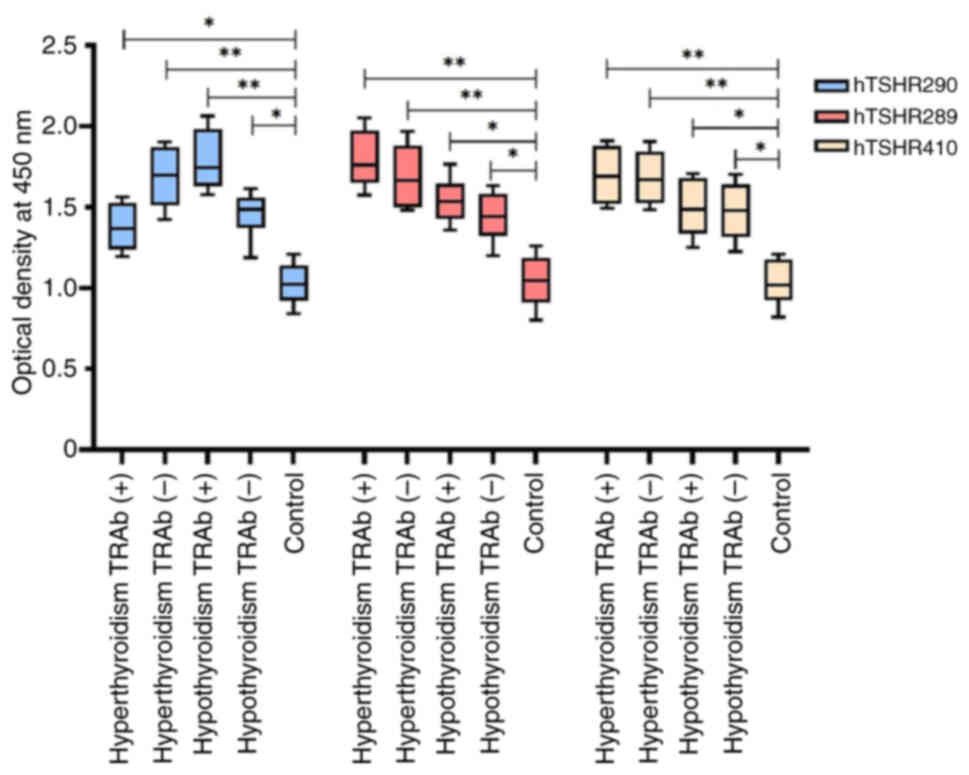

In the present study, an ELISA was carried out to

assess the binding activity of serum IgG antibodies to hTSHR410,

hTSHR289 and hTSHR290 fusion proteins in serum samples from the

aforementioned five groups: Hyperthyroidism (TRAb+ and

TRAb−), hypothyroidism (TRAb+ and

TRAb−) and healthy individuals. The results revealed

that the absorbance [optical density (OD)450 nm] of hTSHR289 fusion

protein with serum from patients in the hyperthyroidism

TRAb+, hyperthyroidism TRAb−, hypothyroidism

TRAb− and hypothyroidism TRAb+ groups was

increased compared with that in healthy individuals (P<0.05).

Among these, the serum from patients with hyperthyroidism

TRAb+ showed the highest binding OD450 value with

hTSHR289 fusion protein. Similarly, the binding OD450 values of

hTSHR290 fusion protein with serum from patients in the

hyperthyroidism TRAb−, hypothyroidism TRAb+,

hypothyroidism TRAb− and hypothyroidism TRAb−

groups were all higher compared with those in healthy individuals

(P<0.05). Among these, the serum from patients with

hypothyroidism TRAb+ exhibited the highest binding OD450

value with the hTSHR290 fusion protein. Furthermore, the binding

OD450 values of the hTSHR410 fusion protein with serum from

patients in the hyperthyroidism TRAb+, hyperthyroidism

TRAb−, hypothyroidism TRAb+ and

hypothyroidism TRAb− groups were all higher compared

with those in healthy individuals (P<0.05; Fig. 3).

Based on Figs. 2

and 3, both the hTSHR290 and

hTSHR289 fusion proteins were revealed to exhibit biological

activity and strong antigenicity. Thus, they could be used as

antigens to establish corresponding serological detection methods

for the determination of TSAb and TBAb.

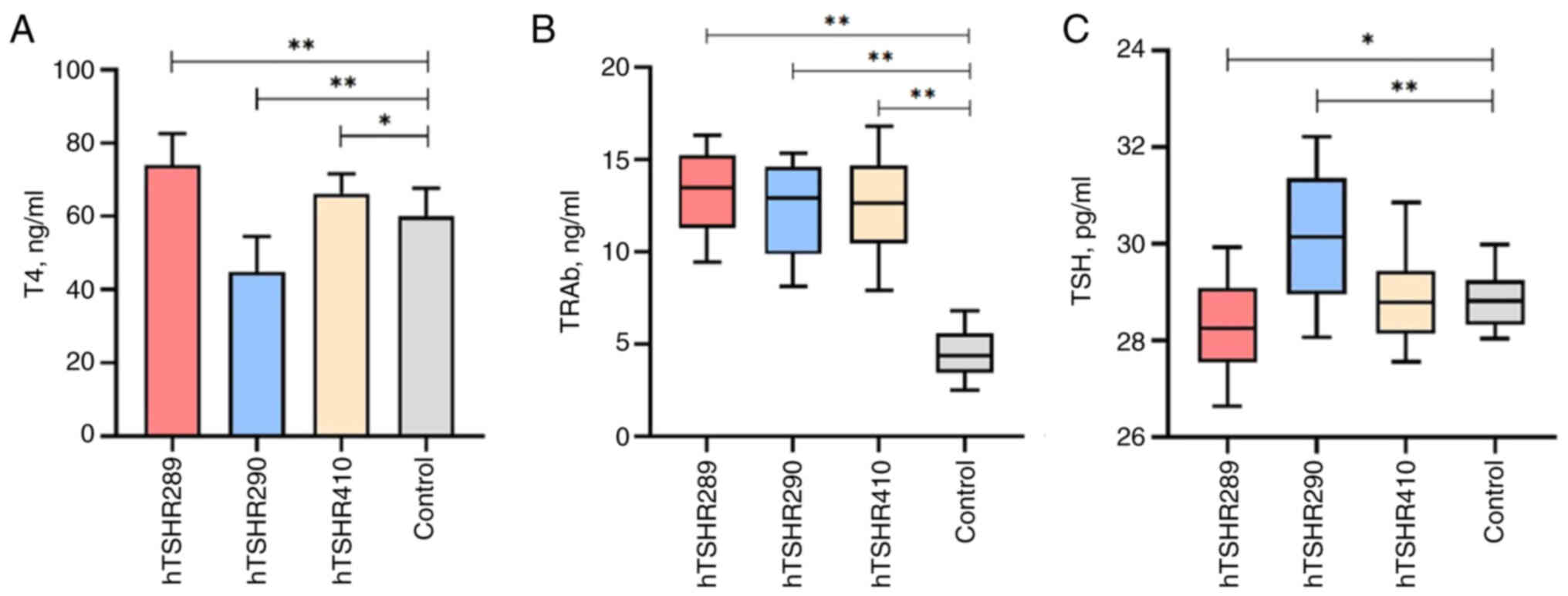

Changes in thyroid function of

immunized mice

An ELISA was carried out to detect the binding

activity of the three fusion proteins with serum from patients with

hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, demonstrating the biological

activity of the prepared fusion proteins. In order to further

validate the immunogenicity of the different fusion proteins,

BALB/c mice were immunized with the fusion proteins.

T4, TSH and TRAb may be effective indicators for

evaluating thyroid function. Following the immunization of mice,

serum samples from the four groups of mice were tested using T4,

TSH and TRAb ELISA kits. Analysis revealed that the T4 levels in

mice immunized with hTSHR289 (aa1-289) fusion protein were

74.06±8.55 ng/ml, and were significantly higher than those in the

control group (60.01±7.74 ng/ml) and exceeded the normal range for

T4 levels (52.27–67.75 ng/ml). The T4 levels in mice immunized with

hTSHR410 (aa21-410) were 66.17±5.48 ng/ml, and were higher compared

with those in the control group (60.01±7.74 ng/ml). The T4 levels

in mice immunized with hTSHR290 (aa290-410) were 44.85±9.70 ng/ml,

and were lower compared with those in the control group (60.01±7.74

ng/ml), and these differences were statistically significant

(P<0.05) (Fig. 4A).

The TSH levels in mice in the hTSHR290 (30.13±1.27

pg/ml) group were significantly higher and the TSH levels in the

hTSHR289 (28.34±0.90 pg/ml) group was significantly higher than

those in the control group (28.82±0.55 pg/ml), exhibiting a

statistically significant difference (P<0.05). The TSH levels in

mice in the hTSHR410 group (28.79±0.81 pg/ml) did not differ

significantly from those in mice in the control group (Fig. 4C).

The TRAb levels in mice immunized with hTSHR289

(13.51±2.26 ng/ml), hTSHR410 (12.47±3.48 ng/ml) and hTSHR290

(13.05±2.53 ng/ml) were all increased compared with those in the

control group (4.16±1.36 ng/ml), which was statistically

significant (P<0.05), as shown in Fig. 4B.

Following the determination of thyroid function

indicators, including T4, TSH and TRAb, to further ascertain

alterations in thyroid function in immunized mice, H&E staining

was conducted on the thyroid tissues and various pathological

changes were observed. Thyroid tissues from 7/12 of the hTSHR289

mice exhibited diffuse hyperplasia with increased cellularity.

Epithelial proliferation led to the formation of papillary

projections into the follicular lumen. The colloid within the

follicular lumen was sparse, exhibiting scalloped edges, along with

varying sizes of absorption vacuoles. The epithelium consisted of

tall columnar cells with basal nuclei that were crowded, round or

elliptical and irregular in shape, indicative of pathological

changes in the thyroids of hyperthyroid mice (Fig. 5A and B). In the thyroid tissues of

8/12 of the hTSHR290 mice, the thyroid follicular epithelium was

composed of tall columnar cells with loosely arranged basal nuclei,

exhibiting round or elliptical nuclei that were irregular in shape.

Some follicles exhibited destruction and atrophy, accompanied by

extruded colloid, representing pathological changes in hypothyroid

mouse thyroids (Fig. 5C and D).

The thyroid lesions in 7/12 of the hTSHR410 mice manifested as

focal distribution, with some follicles displaying destruction,

atrophy and extruded colloid. Regeneration of some follicular

epithelium and increased fibrous tissue between the follicles were

observed (Fig. 5E and F). The

thyroid tissue of mice in the control group revealed that the

follicular structure of the thyroid gland was normal, the follicle

was round or oval, the epithelial cells were arranged in a single

flat shape, and the follicle was filled with glia (Fig. 5G and H). No animals were

prematurely euthanized in the present study, and all animals

completed the predetermined protocol. The results reflected the

respective mean values of all measurements for all randomized

animals.

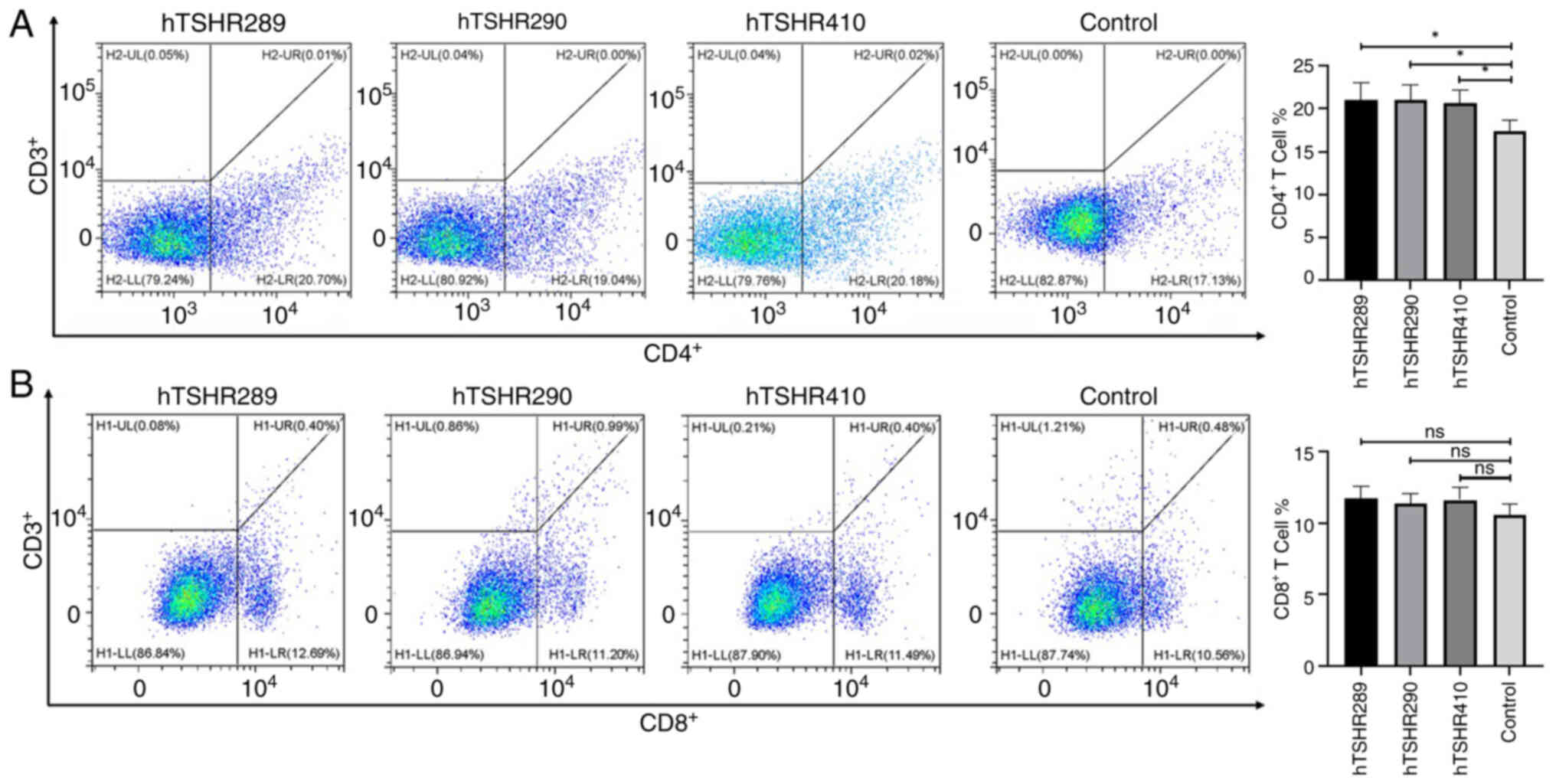

CD4+ T cells and

CD8+ T cells participate in immune responses in

mice

The predominant causes of thyroid cell damage and

TSHR antibody production in AITD include the activation of

CD4+ T cells. Simultaneously, cytokines produced

following the activation of CD4+ T cells stimulate

CD8+ T cells to destroy thyroid cells, particularly

thyroid cells in patients with HT (23,24).

Therefore, the overall balance, proliferation and activation of

CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells are of

importance in the pathogenesis of AITD.

In the present study, the immune response was

further investigated following the immunization of mice with three

types of hTSHR fusion proteins as antigens. Flow cytometry was

utilized to determine the proportions of CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells in splenocytes of each group of mice. The

proportion of CD4+ T cells in the three immunization

groups was increased compared with that in the control group, and

the difference was statistically significant. The proportion of

CD8+ T cells in the three immunization groups was

increased compared with that in the control group; however, the

difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 6).

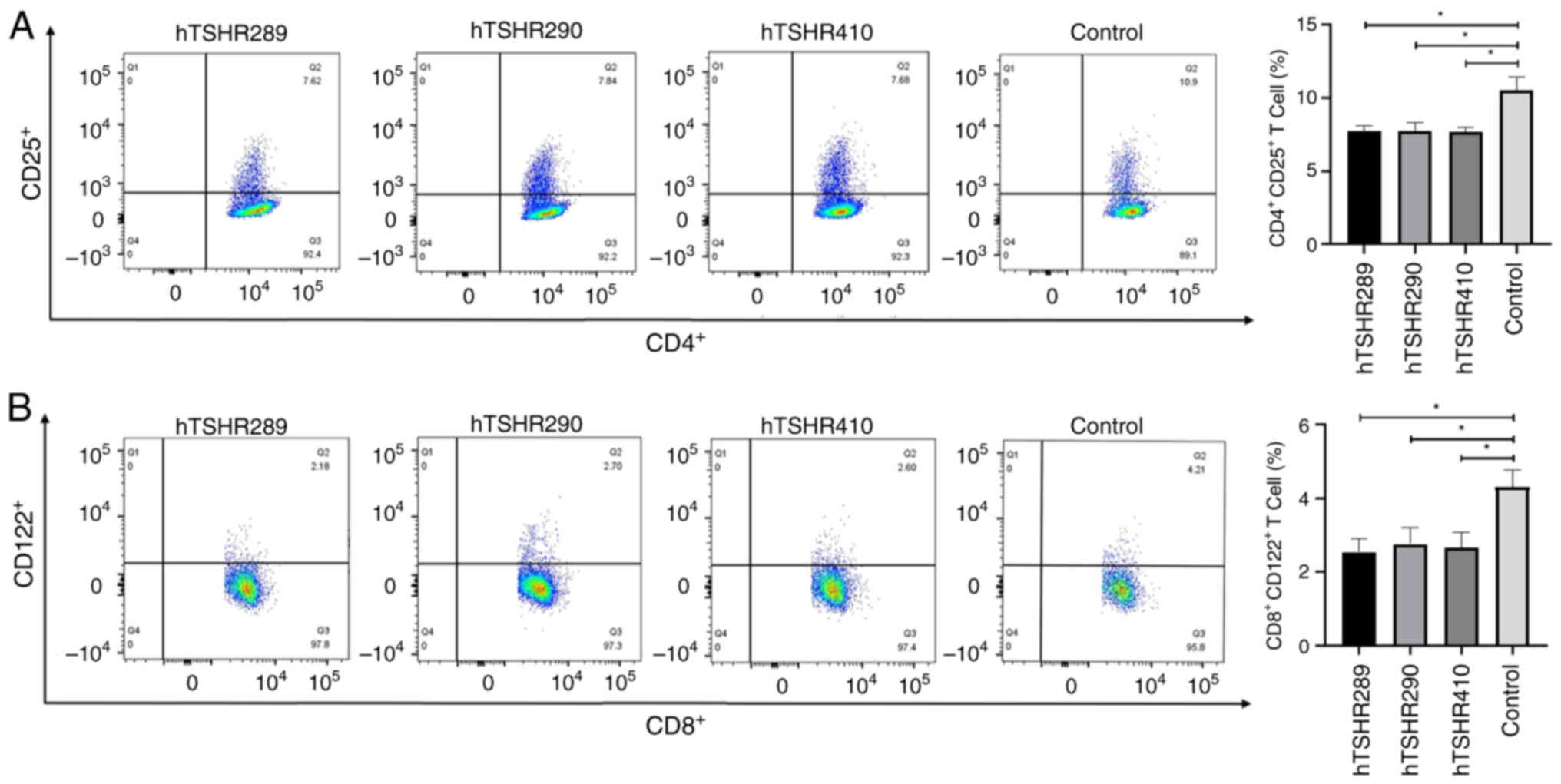

CD4+CD25+ T

cells and CD8+CD122+ T cells participate in

the immune response in mice

CD4+CD25+ T cells and

CD8+CD122+ T cells are associated with the

occurrence and severity of AITD (25,26).

Flow cytometry was carried out to detect the numbers of

CD4+CD25+ T cells and

CD8+CD122+ T cells in spleen cells from each

group of mice. Analysis revealed that the numbers of

CD4+CD25+ T cells and

CD8+CD122+ T cells in spleen cells of the

hTSHR289, hTSHR290 and hTSHR410 groups were decreased compared with

those in the control group (Fig.

7).

Discussion

The occurrence of AITD affects hundreds of millions

of individuals worldwide, with the main types being GD and HT,

characterized by hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, respectively

(27). GD is a diffuse goiter and

hyperthyroidism condition associated with the presence of TSHR and

its autoantibodies (28). TSHR

contains three structural domains: The LRRD, hinge region and TMD

(29–31). The full-length TSHR can be

proteolytically cleaved into an A subunit (aa1-289) and a

transmembrane B subunit (aa370-764) (32,33).

The A subunit can be shed from the full-length TSHR, becoming an

inducer of TRAb autoantibodies (34). Studies have shown that TSAb, TSH

and TBAb can bind to the leucine-rich repeat region, and some TBAb

and neutral antibodies can also bind to linear epitopes in other

structural domains of TSHR (35–37).

Furthermore, the epitopes recognized by TSH, TSAb and TBAb on TSHR

are spatially close and exhibit some overlap (36,37).

Therefore, based on the structural characteristics of TSHR and its

binding properties with autoantibodies, active hTSHR fusion

proteins were produced that mimic the natural protein structure and

function of hTSHR. These include the hTSHR289 fusion protein

containing the active LRRD of hTSHR (TSHR A subunit), the hTSHR410

(aa1-410) fusion protein containing the entire ECD of TSHR, and the

hTSHR290 fusion protein containing the carboxyl-terminal region of

the ECD including the hinge region of TSHR (TSHR aa290-410).

The present study further investigated the

immunogenicity and clinical significance of different fusion

proteins of TSHR using serological and in vivo experiments.

In a study by Zulkarnain et al (38), the authors used a prepared fusion

protein of the TSHR169 fragment to bind with the sera of 20

patients with GD, exploring methods for the diagnosis of GD. In the

present study, serum-based validation was conducted using the ELISA

method. Strong specific binding reactions were observed between the

hTSHR289 fusion protein and the sera of patients with clinically

diagnosed hyperthyroidism with TRAb+. The sera of

patients diagnosed with hyperthyroidism TRAb+ primarily

contain TSAb, indicating that TSAb largely binds specifically to

the TSHRA subunit (4). The

hTSHR290 fusion protein exhibited the strongest binding reaction

with the sera of patients with hypothyroidism who were

TRAb+, and even the sera of patients clinically

diagnosed with hypothyroidism who were TRAb− displayed a

binding reaction with the hTSHR290 fusion protein. Furthermore, the

results of the present study indicated that the carboxyl-terminal

end of TSHR (aa290-410) may be an antigenic determinant for

recognizing TBAb.

In previous years, numerous studies have used

eukaryotic or adenoviral vectors or plasmids as the basis for

investigating the role of TSHR. Researchers have expressed concerns

that prokaryotically prepared TSHR proteins may lack

immunogenicity, which was also a focus of the present study. For

studies of TSHR-induced thyroid disease models, current research

often employs adenoviral vectors carrying the TSHR A subunit or

plasmid-induced GD models. This method requires technical skills

and specialized equipment support, and is expensive (16,39–41).

The present study prepared different fusion proteins of TSHR in a

prokaryotic system, which is simple to operate, has high production

yields (higher than eukaryotic systems) (42) and is cost-effective. Subcutaneous

injection of fusion proteins to establish disease models has been

utilized in various disease models and has been demonstrated to be

effective (20,21). Previous investigations have noted

that immunization of BALB/c mice with the ECD protein of human

thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor induced thyrotropin-binding

inhibitory immunoglobulins (TBII) in the serum, subsequently

leading to thyroid pathology (11,39,43).

In addition, a study has demonstrated that repetitive intravenous

injections of 0.1 mg/kg of cyclic peptide 19, a derivative of the

first cytoplasmic loop of TSHR rich in LRRDs, could reduce thyroid

hyperplasia in a long-term mouse model of GD. This intervention

also led to elevated T4 levels and a reduction in sinus tachycardia

(11). Therefore, the important

role of LRRDs needs to be carefully considered. In the present

study, three fusion proteins with different biological activities

were identified through patient serum analysis. To gain a deeper

understanding of the role of TSHR as a primary antigen in the

pathogenesis of AITD, a series of experiments were conducted using

BALB/c mice to investigate the immunogenicity and clinical

significance of TSHR fusion proteins.

In the present investigation, using various fusion

proteins of hTSHR as immunogens, immune responses were induced in

mice that mimicked those triggered by native hTSHR protein

antigens. Analysis revealed that mice immunized with the hTSHR289

fusion protein exhibited significantly elevated levels of TSHR

antibodies and T4 compared with the control group.

Histopathological examination of thyroid tissue sections revealed

pathological changes consistent with hyperthyroidism. These

findings underscore the potential utility of hTSHR fusion proteins

in developing experimental models of thyroid disorders. Compared

with the control group, the hTSHR290 group of mice exhibited a

significant decrease in T4 levels, along with increased levels of

TRAb and TSH. Pathological examination of thyroid tissue sections

revealed pathological changes consistent with hypothyroidism, such

as the presence of tall columnar cells comprising the thyroid

follicular epithelium with nuclei located basally, partial follicle

destruction and atrophy, as well as extracellular colloid leakage.

When comparing the hTSHR410 group with the control group,

significant increases in TRAb and T4 levels were observed, while

TSH values did not significantly differ between the groups. The

pathological presentation of thyroid tissue indicated focal

distribution of fibrotic changes. Collectively, the fusion protein

hTSHR289 (TSHRA subunit; aa1-289) induced primarily stimulatory

antibodies in mice, leading to the development of GD. The fusion

protein hTSHR290 (carboxyl-terminal region of TSHR; aa290-410)

acted as an immunogenic antigen, resulting in the production of

TBAb, and thus, inducing hypothyroidism in mice. hTSHR410 fusion

protein (entire ECD of TSHR) triggered a cross-reactive immune

response in mice, among which the pathological changes associated

with GD were more prominent. However, as a single model for

research into AITD, the hTSHR410 fusion protein as an immunogen may

not be an ideal choice. Therefore, the utilization of hTSHR289 and

hTSHR290 fusion proteins as immunogens to induce hyperthyroidism

and hypothyroidism animal models, respectively, would be beneficial

for in-depth exploration of the occurrence, progression and

treatment of AITD. Furthermore, inducing disease occurrence through

fusion proteins is close to the natural process of autoimmune

disease development. The animal models induced and constructed in

the present study will be more conducive to the research of

AITD.

The activation of CD4+ T cells serves as

the primary mechanism in AITDs leading to thyroid cell damage and

the production of TRAb (31,44).

In HT, thyroid cells are destructed by inflammatory infiltration

composed of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells,

macrophages and plasma cells (24). Both CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells infiltrate the thyroid gland in varying

proportions, resulting in altered thyroid function and the onset of

HT and GD. Furthermore, they are closely associated with TRAb

levels, serving a key role in predicting treatment outcomes

(44,45). The animal experiments in the

present study indicated that the hTSHR fusion protein induced

alterations in mice, leading to hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism and

inflammatory responses. Further confirming the immunogenicity of

hTSHR fusion proteins and their role in inducing pathogenic TRAb in

mice, the present results indicated that the ratio of

CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells was altered in

immunized mice.

The specific expression of CD25 on the surface of

CD4+ T cells accounts for ~10% of peripheral blood

CD4+ T cells. Inhibiting abnormal or excessive immune

responses against self, microbial and environmental antigens is

associated with a wide range of autoimmune diseases (autoimmune

gastritis, thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes) (46). Deficiency of

CD4+CD25+ T cells leads to various autoimmune

and inflammatory states in mice (47). Studies have found that the

frequency of CD4+CD25+ T cells in lupus-prone

mice was lower than that in normal mice (48,49).

A decrease in the number of CD4+CD25+ T cells

may be one of the mechanisms leading to immune dysregulation in

immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), and the changes in the number of

CD4+CD25+ T cells are considered to be

associated with the severity of ITP (25). The lack of

CD4+CD25+ T cells can lead to severe

autoimmune/inflammatory diseases, while normal regulatory T cells

(Tregs) can inhibit disease development (50). CD122 is the β subunit of the IL-2

receptor, not only regulating Tregs but also influencing Treg

function. CD8+CD122+ T cells may regulate

immune responses by producing IL-10, TGFβ1 and IFNγ; however, the

exact mechanism of their inhibitory effect remains largely unknown

(51,52). Previous studies have indicated that

CD8+CD122+ T cells could suppress T cell

responses, modulated autoimmunity and alloimmune responses, and

served an important role in autoimmune diseases (52–54).

The development of systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease in

B6-Yaa mutant mice is associated with a defect in

CD8+CD122+ T cells (55). Disruption of the inhibitory

interaction between CD8+CD122+ T cells and

follicular helper T cells leads to the development of a lethal

systemic lupus erythematosus-like autoimmune disease dependent on

autoantibodies (56). The

depletion of CD8+CD122+ T cells increases the

incidence of AITD (57). Research

data show that CD8+CD122+ T cells in

secondary lymphoid organs of prediabetic non-obese diabetic mice

are reduced by ~50%, highlighting the role of

CD8+CD122+ T cells in suppressing autoimmune

diseases (26). Several studies

have shown that CD4+CD25+ and

CD8+CD122+ T cells serve a key role in the

incidence and severity of GD, HT and hypothyroidism (57,58).

The present study revealed that immunization with hTSHR fusion

protein led to a decrease in the number of

CD4+CD25+ and

CD8+CD122+ T cells in the secondary lymphoid

organs of mice. Collectively, the data in the present study

suggested that the three types of TSHR fusion proteins that were

prepared could induce immune dysregulation in BALB/c mice, leading

to the development of AITD.

The present study offers insights into the

significance of different structural domains of TSHR in the

pathogenesis of AITD. Additionally, the TRAb assay kit may also be

used to monitor changes in the condition of patients, providing

evidence for the early diagnosis and individualized treatment of

patients. The primary concern now is that the ELISA may face issues

when used in clinical testing, such as false positives, and low

sensitivity and specificity, which will affect the diagnosis and

treatment of patients. Therefore, multi-center and large-sample

research and testing are required, which should include a larger

group of patients. A more stable and accurate ELISA detection

system also needs to be created to improve reliability and clinical

applicability. In the present study, three fusion proteins were

prepared according to the characteristics of the TSHR domain, and

the regions that TSHR may bind with TSAb and TBAb were initially

identified. In the subsequent experiment, the extracellular region

of TSHR was segmented into smaller structural units according to

the structural characteristics of the internal functional

characteristics of a single domain. Further refining and clarifying

the binding sites of TSAb, TBAb and TSHR is also an effective way

of reducing false positives and increasing sensitivity and

specificity. In addition, combining the fusion protein with TRAb

detection methods such as the current third-generation TBII method

and biological assays is also one of the methods for more accurate

diagnosis and treatment of patients, which needs further

research.

Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the

biological effects of the TSHR fusion protein and in-depth

exploration of the specific mechanism of TSHR fusion protein

inducing the immune response can help increase the understanding of

the pathogenesis of AITD, provides a scientific basis for research

of TSHR and the application of fusion proteins, and provides a

basis for the accurate diagnosis, and individualized diagnosis and

treatment of patients with AITD.

In view of the important role of TSHR in AITDs, the

present study expressed fusion proteins of different domains of

TSHR, and the fusion proteins of different domains of TSHR

exhibited different immunogenicity. The TSHR A subunit fusion

protein and TSHR carboxyl-terminal fusion protein prepared in the

present study could serve as a basis for the development of ELISA

kits for the detection of TSAb and TBAb. Fusion proteins of

different structural domains of TSHR induced clinical symptoms of

hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism in mice. This research provides

a scientific basis for future studies on the etiology and

mechanisms of AITD, as well as the invention of novel methods for

the detection of TRAb.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Science and Technology

Plan Project of Gansu Province (Basic Research Plan; grant no.

25JRRA597) and the Lanzhou University Second Hospital ‘Cuiying

Technological Innovation’ Program (grant no. CY2018-ZD02).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XC contributed to conceptualization,

methodology,-visualization, writing of the original draft and

editing. HC contributed to conceptualization, acquired funding,

provided resources, supervised the study and revised the

manuscript. Both authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript. XC and HC confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiments received approval from the

Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of The Second Hospital of

Lanzhou University (approval no. D2023-156; Lanzhou, China). The

research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics

Committee of The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (approval

no. 2023A-802; Lanzhou, China). All participants provided written

informed consent prior to participating in the present study. All

experiments have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee

and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical

standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its

later amendments.

Patient consent for publication

Informed consent from patients was obtained for

publication of the present study, and relevant written consent has

been provided.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

McLachlan SM and Rapoport B: Thyroid

autoantibodies display both ‘Original antigenic sin’ and epitope

spreading. Front Immunol. 8:18452017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Furmaniak J, Sanders J, Núñez Miguel R and

Rees Smith B: Mechanisms of action of TSHR autoantibodies. Horm

Metab Res. 47:735–752. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Furmaniak J, Sanders J, Sanders P, Li Y

and Rees Smith B: TSH receptor specific monoclonal autoantibody

K1-70TM targeting of the TSH receptor in subjects with

Graves' disease and Graves' orbitopathy-Results from a phase I

clinical trial. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 96:878–887. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gupta AK and Kumar S: Utility of

antibodies in the diagnoses of thyroid diseases: A review article.

Cureus. 14:e312332022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Smith TJ and Hegedüs L: Graves' disease. N

Engl J Med. 375:1552–1565. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Latif R, Mezei M, Morshed SA, Ma R,

Ehrlich R and Davies TF: A Modifying autoantigen in Graves'

disease. Endocrinology. 160:1008–1020. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Núñez Miguel R, Sanders P, Allen L, Evans

M, Holly M, Johnson W, Sullivan A, Sanders J, Furmaniak J and Rees

Smith B: Structure of full-length TSH receptor in complex with

antibody K1-70™. J Mol Endocrinol. 70:e2201202022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

George A, Diana T, Längericht J and Kahaly

GJ: Stimulatory thyrotropin receptor antibodies are a biomarker for

graves' orbitopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 11:6299252021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Lytton SD, Schluter A and Banga PJ:

Functional diagnostics for thyrotropin hormone receptor

autoantibodies: Bioassays prevail over binding assays. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 23:2028–2043. 2018. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bahn RS: Current Insights into the

Pathogenesis of Graves' Ophthalmopathy. Horm Metab Res. 47:773–778.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Faßbender J, Holthoff HP, Li Z and Ungerer

M: Therapeutic effects of short cyclic and combined epitope

peptides in a Long-term model of Graves' disease and orbitopathy.

Thyroid. 29:258–267. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Rapoport B, Aliesky HA, Chen CR and

McLachlan SM: Evidence that TSH receptor A-subunit multimers, not

monomers, drive antibody affinity maturation in Graves' disease. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab. 100:E871–E875. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li CW, Osman R, Menconi F, Concepcion E

and Tomer Y: Cepharanthine blocks TSH receptor peptide presentation

by HLA-DR3: Therapeutic implications to Graves' disease. J

Autoimmun. 108:1024022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Holthoff HP, Goebel S, Li Z, Faßbender J,

Reimann A, Zeibig S, Lohse MJ, Münch G and Ungerer M: Prolonged TSH

receptor A subunit immunization of female mice leads to a long-term

model of Graves' disease, tachycardia, and cardiac hypertrophy.

Endocrinology. 156:1577–1589. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rapoport B, Chazenbalk GD, Jaume JC and

McLachlan SM: The thyrotropin (TSH) receptor: Interaction with TSH

and autoantibodies. Endocr Rev. 19:673–716. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Davies TF, Ando T, Lin RY, Tomer Y and

Latif R: Thyrotropin receptor-associated diseases: From adenomata

to Graves disease. J Clin Invest. 115:1972–1983. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Latif R, Teixeira A, Michalek K, Ali MR,

Schlesinger M, Baliram R, Morshed SA and Davies TF: Antibody

protection reveals extended epitopes on the human TSH receptor.

PLoS One. 7:e446692012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Marcinkowski P, Kreuchwig A, Mendieta S,

Hoyer I, Witte F, Furkert J, Rutz C, Lentz D, Krause G and Schülein

R: Thyrotropin receptor: Allosteric modulators illuminate

intramolecular signaling mechanisms at the interface of Ecto- and

transmembrane domain. Mol Pharmacol. 96:452–462. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Thyroid disease, . Assessment and

management. London: National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE); November 20–2019

|

|

20

|

Holthoff HP, Uhland K, Kovacs GL, Reimann

A, Adler K, Wenhart C and Ungerer M: Thyroid-stimulating hormone

receptor (TSHR) fusion proteins in Graves' disease. J Endocrinol.

246:135–147. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang Y, Xia Q, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Guan Z,

Zhang J, Li Z, Liu K, Li B, Shao D, et al: B602L-Fc fusion protein

enhances the immunogenicity of the B602L protein of the African

swine fever virus. Front Immunol. 14:11862992023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A,

Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl

U, et al: The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for

reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18:e30004102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zheng H, Xu J, Chu Y, Jiang W, Yao W, Mo

S, Song X and Zhou J: A global regulatory network for dysregulated

gene expression and abnormal metabolic signaling in immune cells in

the microenvironment of Graves' disease and Hashimoto's

thyroiditis. Front Immunol. 13:8798242022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kristensen B: Regulatory B and T cell

responses in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease and healthy

controls. Dan Med J. 63:B51772016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hsu WT, Suen JL and Chiang BL: The role of

CD4CD25 T cells in autoantibody production in murine lupus. Clin

Exp Immunol. 145:513–519. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Arndt B, Witkowski L, Ellwart J and

Seissler J: CD8+ CD122+ PD-1-effector cells promote the development

of diabetes in NOD mice. J Leukoc Biol. 97:111–120. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Benvenga S, Elia G, Ragusa F, Paparo SR,

Sturniolo MM, Ferrari SM, Antonelli A and Fallahi P: Endocrine

disruptors and thyroid autoimmunity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 34:1013772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A,

Gutierrez-Buey G, Lazarus JH, Dayan CM and Okosieme OE: Global

epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev

Endocrinol. 14:301–316. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Duan J, Xu P, Cheng X, Mao C, Croll T, He

X, Shi J, Luan X, Yin W, You E, et al: Structures of full-length

glycoprotein hormone receptor signalling complexes. Nature.

598:688–692. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Jiang X, Liu H, Chen X, Chen PH, Fischer

D, Sriraman V, Yu HN, Arkinstall S and He X: Structure of

follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with the entire ectodomain

of its receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:12491–12496. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kleinau G, Mueller S, Jaeschke H, Grzesik

P, Neumann S, Diehl A, Paschke R and Krause G: Defining structural

and functional dimensions of the extracellular thyrotropin receptor

region. J Biol Chem. 286:22622–22631. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Rapoport B and McLachlan SM: TSH receptor

cleavage into subunits and shedding of the A-subunit; a molecular

and clinical perspective. Endocr Rev. 37:114–134. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Couët J, de Bernard S, Loosfelt H, Saunier

B, Milgrom E and Misrahi M: Cell surface protein

disulfide-isomerase is involved in the shedding of human

thyrotropin receptor ectodomain. Biochemistry. 35:14800–14805.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Duan J, Xu P, Luan X, Ji Y, He X, Song N,

Yuan Q, Jin Y, Cheng X, Jiang H, et al: Hormone- and

antibody-mediated activation of the thyrotropin receptor. Nature.

609:854–859. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Faust B, Billesbølle CB, Suomivuori CM,

Singh I, Zhang K, Hoppe N, Pinto AFM, Diedrich JK, Muftuoglu Y,

Szkudlinski MW, et al: Autoantibody mimicry of hormone action at

the thyrotropin receptor. Nature. 609:846–853. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Morshed SA and Davies TF: Graves' disease

mechanisms: The role of stimulating, blocking, and cleavage region

TSH receptor antibodies. Horm Metab Res. 47:727–734. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Akamizu T, Kosugi S, Kohn LD and Mori T:

Anti-thyrotropin (TSH) receptor antibody binding epitopes of TSH

receptor: Site-directed mutagenesis approach. Nihon Rinsho.

52:1024–1030. 1994.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zulkarnain Z, Ulhaq ZS, Sujuti H,

Soeatmadji DW, Zufry H, Wuragil DK, Marhendra APW, Riawan W,

Kurniawati S, Oktanella Y and Aulanni'am A: Comparative performance

of ELISA and dot blot assay for TSH-receptor antibody detection in

Graves' disease. J Clin Lab Anal. 36:e242882022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

McLachlan SM, Aliesky HA, Garcia P,

Banuelos B and Rapoport B: Thyroid hemiagenesis in a thyroiditis

prone mouse strain. Eur Thyroid J. 7:187–192. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Rapoport B, Aliesky HA, Banuelos B, Chen

CR and McLachlan SM: A unique mouse strain that develops

spontaneous, Iodine-accelerated, pathogenic antibodies to the human

thyrotrophin receptor. J Immunol. 194:4154–4161. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schlüter A, Horstmann M, Diaz-Cano S,

Plöhn S, Stähr K, Mattheis S, Oeverhaus M, Lang S, Flögel U,

Berchner-Pfannschmidt U, et al: Genetic immunization with mouse

thyrotrophin hormone receptor plasmid breaks Self-tolerance for a

murine model of autoimmune thyroid disease and Graves' orbitopathy.

Clin Exp Immunol. 191:255–267. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Porowińska D, Wujak M, Roszek K and

Komoszyński M: Prokaryotic expression systems. Postepy Hig Med Dosw

(Online). 67:119–129. 2013.(In Polish). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Costagliola S, Alcalde L, Tonacchera M,

Ruf J, Vassart G and Ludgate M: Induction of thyrotropin receptor

(TSH-R) autoantibodies and thyroiditis in mice immunised with the

recombinant TSH-R. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 199:1027–1034. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Janyga S, Marek B, Kajdaniuk D,

Ogrodowczyk-Bobik M, Urbanek A and Bułdak Ł: CD4+ cells in

autoimmune thyroid disease. Endokrynol Pol. 72:572–583. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yin L, Zeng C, Yao J and Shen J: Emerging

roles for noncoding RNAs in autoimmune thyroid disease.

Endocrinology. 161:bqaa0532020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sakaguchi S, Mikami N, Wing JB, Tanaka A,

Ichiyama K and Ohkura N: Regulatory T cells and human disease. Annu

Rev Immunol. 38:541–566. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Grindebacke H, Wing K, Andersson AC,

Suri-Payer E, Rak S and Rudin A: Defective suppression of Th2

cytokines by CD4CD25 regulatory T cells in birch allergics during

birch pollen season. Clin Exp Allergy. 34:1364–1372. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Rosenberger S, Undeutsch R, Akbarzadeh R,

Ohmes J, Enghard P, Riemekasten G and Humrich JY: Regulatory T

cells inhibit autoantigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses in

lupus-prone NZB/W F1 mice. Front Immunol. 14:12541762023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yan JJ, Lee JG, Jang JY, Koo TY, Ahn C and

Yang J: IL-2/anti-IL-2 complexes ameliorate lupus nephritis by

expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Kidney Int.

91:603–615. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Malek TR and Castro I: Interleukin-2

receptor signaling: At the interface between tolerance and

immunity. Immunity. 33:153–165. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Rifa'i M, Kawamoto Y, Nakashima I and

Suzuki H: Essential roles of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the

maintenance of T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 200:1123–1134. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Yuan X, Dong Y, Tsurushita N, Tso JY and

Fu W: CD122 blockade restores immunological tolerance in autoimmune

type 1 diabetes via multiple mechanisms. JCI Insight. 3:e966002018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Liu J, Chen D, Nie GD and Dai Z:

CD8(+)CD122(+) T-cells: A newly emerging regulator with central

memory cell phenotypes. Front Immunol. 6:4942015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Mishra S, Srinivasan S, Ma C and Zhang N:

CD8+ regulatory T cell-a mystery to be revealed. Front Immunol.

12:7088742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Kim HJ, Wang X, Radfar S, Sproule TJ,

Roopenian DC and Cantor H: CD8+ T regulatory cells express the Ly49

Class I MHC receptor and are defective in autoimmune prone B6-Yaa

mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:2010–2015. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kim HJ, Verbinnen B, Tang X, Lu L and

Cantor H: Inhibition of follicular T-helper cells by CD8(+)

regulatory T cells is essential for self tolerance. Nature.

467:328–332. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Saitoh O, Abiru N, Nakahara M and Nagayama

Y: CD8+CD122+ T cells, a newly identified regulatory T subset,

negatively regulate Graves' hyperthyroidism in a murine model.

Endocrinology. 148:6040–6046. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

McLachlan SM, Nagayama Y, Pichurin PN,

Mizutori Y, Chen CR, Misharin A, Aliesky HA and Rapoport B: The

link between Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis: A role

for regulatory T cells. Endocrinology. 148:5724–5733. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|