Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the most prevalent and

life-threatening cancer types worldwide. Due to its high incidence

and global mortality rates, as well as the limited therapeutic

options at advanced stages, liver cancer remains a major clinical

challenge (1–3).

Estrogen receptor (ER)-mediated signaling is known

to contribute to the pathogenesis of liver cancer (4,5).

ER-α36, an isoform of ER-α, has been reported to play a critical

role in the development of numerous tumors, including liver cancer

(6,7). ER-α36 is transcribed from a promoter

located in the first intron of the classic ER-α gene. Unlike

classical ER-α, ER-α36 is mainly localized on the plasma membrane,

where it mediates rapid estrogen signaling (8). ER-α36 expression in primary liver

cancer is upregulated compared with that in adjacent non-tumor

tissues, contrasting with the expression pattern of classical ER-α

(7,9). In addition, ER-α36-mediated rapid

estrogen signaling has been shown to promote the growth of

PLC/PRF/5 and HepG2 liver cancer cells, in culture and in

tumorspheres, through the epidermal growth factor

receptor/Src/extracellular signal-regulated kinase axis (10). Tamoxifen, an ER-α antagonist, has

not provided survival benefits in patients with breast cancer

(11), and ER-α36 has been

indicated to contribute to tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

and glioblastoma cells (11,12).

These findings suggest that ER-α36, rather than classical ER-α, is

the key ER isoform involved in the development and progression of

liver cancer. However, the mechanism underlying the potential

contribution of ER-α36 to liver tumorigenesis remains unclear.

Autophagy is a catabolic pathway that maintains

cellular homeostasis and supports organelle renewal by removing

misfolded proteins, cytotoxic aggregates and damaged organelles

(13). During this process,

cytoplasmic components are sequestered into autophagosomes, which

subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes. Within

autolysosomes, cellular contents, including protein substrates,

receptors and other autophagosome-associated proteins, are degraded

by lysosomal acidic hydrolases (14). Thus, lysosomes function as the

terminal degradation component of the autophagic process. Studies

have shown that lysosomal dysfunction, including lysosomal membrane

permeabilization (LMP), loss of acidity, changes in lysosome

localization and defects in lysosome-associated signaling molecules

(15–18), can impair the degradative capacity

of the lysosomal-autophagy pathway. These dysfunctions have

profound implications for the development and progression of

numerous diseases, including cancer (19). Tumor cells rely heavily on

increased lysosomal function to meet their proliferation and

metabolism requirements, which renders them particularly sensitive

to lysosomal dysregulation (20,21).

For example, it has been found that the re-localization of

lysosomes to the tumor cell periphery facilitates the exocytosis of

cathepsins, neuraminidase-1 and heparinase, thereby promoting tumor

cell invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis (20,22).

In addition, lysosomal acidity has been shown to influence cell

growth through the maintenance of iron homeostasis (23). Thus, the lysosome is an important

regulatory hub for multiple pathways involved in cell proliferation

(21). However, the exact

mechanism by which lysosomal function contributes to the

proliferation of liver cancer cells remains unclear.

In the present study, the role of ER-α36 in

regulating the malignant proliferation of liver cancer cells was

investigated in vivo and in vitro. In addition, the

role of ER-α36 in autophagy and lysosomal distribution was

examined.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

17β-estradiol (E2) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck KGaA. The ER-α36 antibody was kindly provided by Dr Zhaoyi

Wang (Shenogen Pharma Group). Antibodies against p62 (also known as

sequestosome 1; cat. no. 18420-1-AP), galectin-3 (Gal-3; cat. no.

60207-1-Ig), lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1; cat.

no. 21997-1-AP), AKT (cat. no. 10176-2-AP), phosphorylated-(p-)AKT

(cat. no. 66444-1-Ig) and β-actin (cat. no. 60008-1-IG) were

purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc. The microtubule-associated

protein 1 light chain 3b (LC3B) antibody (cat. no. A19665) was

purchased from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd. Antibodies for ubiquitin

(Ub; cat. no. AF0306) were purchased from Beyotime Biotech Inc. The

Ki67 antibody (cat. no. bs-2130R) was purchased from Biosynthesis

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Chloroquine (CQ; cat. no. HY-17589A) and

the AKT inhibitor MK-2206 (cat. no. HY-108232) were obtained from

MedChemExpress.

Cell culture, stably transfected cell

line preparation and cell treatment

The HepG2 (cat. no. STCC10114) and Huh7 (cat. no.

STCC10102) human liver cancer cell lines, which endogenously

express ER-α36, were obtained from Shenogen Pharma Group (7). The authenticity of both cell lines

was confirmed by STR analysis. The cells were maintained in DMEM

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with 10% FBS; Zhejiang Tianhang

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2.

Stable ER-α36 knockdown cell lines and control cell

lines were established as previously described (10,24).

In brief, short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting human ER-α36 was

constructed using the pRNAT-U6.1/Neo vector (provided by Dr Zhaoyi

Wang) (25,26). The construct was validated by DNA

sequencing. The target sequence was as follows: shER-α36:

5′-GTTCAGTACCTATTGGCA-3′ (nucleotides 4,261-4,278; sequence ID:

BX640939.1). The empty vector and ER-α36 shRNA expression vector (2

µg/ml) were transfected into the liver cancer cells for 6 h at

37°C, using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as the transfection reagent. The

transfected cells were selected with 600 µg/ml G418 (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 3 weeks. After this, cells from ≥25

clones were pooled. The empty vector transfected cells were named

HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector, and those transfected with ER-α36

shRNA were named HepG2/Sh36 and Huh7/Sh36.

For treatment, the cells were maintained in phenol

red-free DMEM with 1% charcoal-stripped fetal calf serum (FCS;

Zhejiang Tianhang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 48 h, and then

treated with MK-2206 (100 nM) for 6 h, followed by E2 (1 nM) for

either 30 min (detection of the phosphorylation levels of AKT) or

24 h (detection of LAMP1 expression) at 37°C in an atmosphere

containing 5% CO2 (10). An equal volume of alcohol was used

as the vehicle control. The cells were treated with CQ (20 µM) for

24 h at 37°C; the same volume of DMSO was used as the vehicle

control.

Western blot analysis

Cells and liver tissues were lysed with RIPA lysis

buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Protein

concentrations were measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit. The

proteins (20 µg/lane) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with

5% skim milk powder in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1%

Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking,

membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies:

anti-ER-a36 (1:1,000), anti-LC3B (1:1,000), anti-p62 (1:1,000),

anti-Ub (1:1,000), anti-LAMP1 (1:1,000), anti-p-AKT (1:1,000),

anti-AKT (1:1,000) and anti-β-actin (1:2,000). After washing with

TBST, the membranes were incubated with HRP Conjugated AffiniPure

Goat Anti-rabbit/mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibodies (cat. no.

BA1055/BA1051, 1:5,000, Wuhan Boster Biological Technology CO.,

LTD.) at room temperature for 1 h. Following incubation, membranes

were washed in TBST. The target proteins were detected using

enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagent (BeyoECL Moon

kit; Beyotime Institute of Biotech Inc.). Signal intensities were

captured using ECL western-blotting analysis system (GE

Healthcare). And quantitative analysis was performed using ImageJ

version 1.53t software (National Institutes of Health).

Colony formation assay

After seeding (2×103 cells/well), cells

were treated with MK-2206 (100 nM) for 6 h alone or in combination

with E2 (1 nM) for 24 h and cultured for 2 weeks at 37°C. The cell

colonies were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 15 min at 37°C. After washing with PBS, cells were stained with

1% crystal violet for 30 min at 37°C. Colonies containing >50

cells were counted. Colonies count was performed using ImageJ v

2.14.0 (FIJI) software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence (IF) staining

After seeding (5×103 cells/well), the

cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room

temperature. The tumor tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for

24 h at room temperature, dehydrated in graded ethanol, embedded in

paraffin, and sectioned into 4 µm slices. After paraffin was

removed with xylene at room temperature, the slides were gradually

hydrated using ethanol. The slides were incubated in 3% hydrogen

peroxide/methanol buffer to quench endogenous peroxidase activity.

Antigen retrieval was performed by immersing the slides in

ethylenediamine tetra acetic acid buffer (pH 8.0) and boiling for 5

min. Then, the samples were blocked with 5% BSA (BioFroxx) for 1 h

at room temperature, incubated with primary antibodies: anti-LC3B

(1:500), anti-p62 (1:500), anti-LAMP1 (1:500) and anti-Gal-3

(1:500) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with secondary

antibodies conjugated to fluorescein: ABflo®

488-conjugated Goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat. no.

AS076/AS053, 1:200, ABclonal Biotech Co.) or ABflo®

594-conjugated Goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat. no.

AS054/AS039, 1:200, ABclonal Biotech Co.) for 1 h at room

temperature. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 for 10 min

at room temperature. Images were captured using a Leica TCS SP8

confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems. Inc.), and image analysis

was performed using ImageJ v 2.14.0 (FIJI) software (National

Institutes of Health).

pmCherry-enhanced green fluorescence

protein (EGFP)-LC3 puncta assay

After seeding (1×104 cells/well), cells

were infected with the pmCherry-EGFP-LC3b adenovirus (MOI: 20;

Beyotime Biotech Inc.) for 12 h at 37 °C. Then, the infection

medium was replaced with fresh complete medium and cells were

cultured for 24 h at 37 °C. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst

33342 for 10 min at room temperature. Images were captured using a

Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems. Inc.), and

image analysis was performed using ImageJ v 2.14.0 (FIJI) software

(National Institutes of Health).

Lyso-Tracker Red staining

After seeding (5×103 cells/well), cells

were incubated in Lyso-Tracker Red (50 nM, Beyotime Institute of

Biotech Inc.) for 15 min at 37 °C. The nuclei were stained with

Hoechst 33342 for 10 min at room temperature, and images were

captured using an Olympus BX53 fluorescence microscope (Olympus

Co., Ltd).

Animal experiments

All experimental procedures were performed in

compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for

the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Ethics

Committee of Jianghan University (Wuhan, China; approval no.

JHDXLL2024-086). A total of 10 male BALB/c-nu mice (5 weeks old,

16–18 g) were purchased from Sipeifu (Beijing) Animal Technology

Co., Ltd., and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions at a

temperature of 24±2°C and relative humidity of 60%. The mice were

exposed to a 12-h light/dark cycle, and were given free access to

mouse feed sterilized and water sterilized by autoclaving. The

HepG2/Sh36 and HepG2/Vector cells (5×106 cells/mouse)

were injected into the livers of BALB/c-nu mice (n=4/group) to

establish 28-day orthotopic liver xenograft tumor models. The mice

were monitored daily for food and water intake, weight, body

posture, behavior, distress and response to external stimuli.

Several humane endpoints were established, including a >20% loss

of body weight, severe dehydration, refusal of food, severe pain or

distress, or a moribund state. However, no mice were humanely

sacrificed or found dead prior to the designated end of the study.

After 28 days, the mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal

injection of pentobarbital sodium at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight

and sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Death was confirmed when no

breathing or heartbeat was detected for >5 min. The livers were

then harvested from the mice for further investigation.

H&E Staining

The tumor tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h at room temperature, dehydrated in graded ethanol,

embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 4 µm slices. After

paraffin was removed with xylene at room temperature, the slides

were gradually hydrated using ethanol. The slides were dyed with

hematoxylin for 30 sec at room temperature and eosin for 1 min at

room temperature. Images were captured using a light

microscope.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

The tumor tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h at room temperature, dehydrated in graded ethanol,

embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 4 µm slices. After

paraffin was removed with xylene at room temperature, the slides

were gradually hydrated using ethanol. The slides were incubated in

3% hydrogen peroxide/methanol buffer to quench endogenous

peroxidase activity. Antigen retrieval was performed by immersing

the slides in ethylenediamine tetra acetic acid buffer (pH 8.0) and

boiling for 5 min. The slides were blocked with 5% BSA (BioFroxx)

for 1 h at room temperature, incubated with primary antibodies:

anti-LC3B (1:200), anti-p62 (1:200), anti-LAMP1 (1:200) and

anti-Ki67 (1:200) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with

secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit/mouse HRP-labeled polymer;

cat. no. PV-9000, Beijing Zhong Shan-Golden Bridge Biological

Technology CO., Ltd.) for 1 h at 37°C. The slides were stained with

3,3′-Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Beijing Zhong Shan

-Golden Bridge Biological Technology CO., Ltd.) and counterstained

with hematoxylin for 30 s at room temperature to visualize the cell

nuclei. Then, the slides were photographed by a light microscope.

Quantification of the positive staining was performed by measuring

the integral optical density using ImageJ v 2.14.0 (FIJI) software

(National Institutes of Health), with normalization to the stained

area.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of

mean of at least three independent experiments. The data were

analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (Dotmatics) with one-way

analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni's post hoc

tests. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

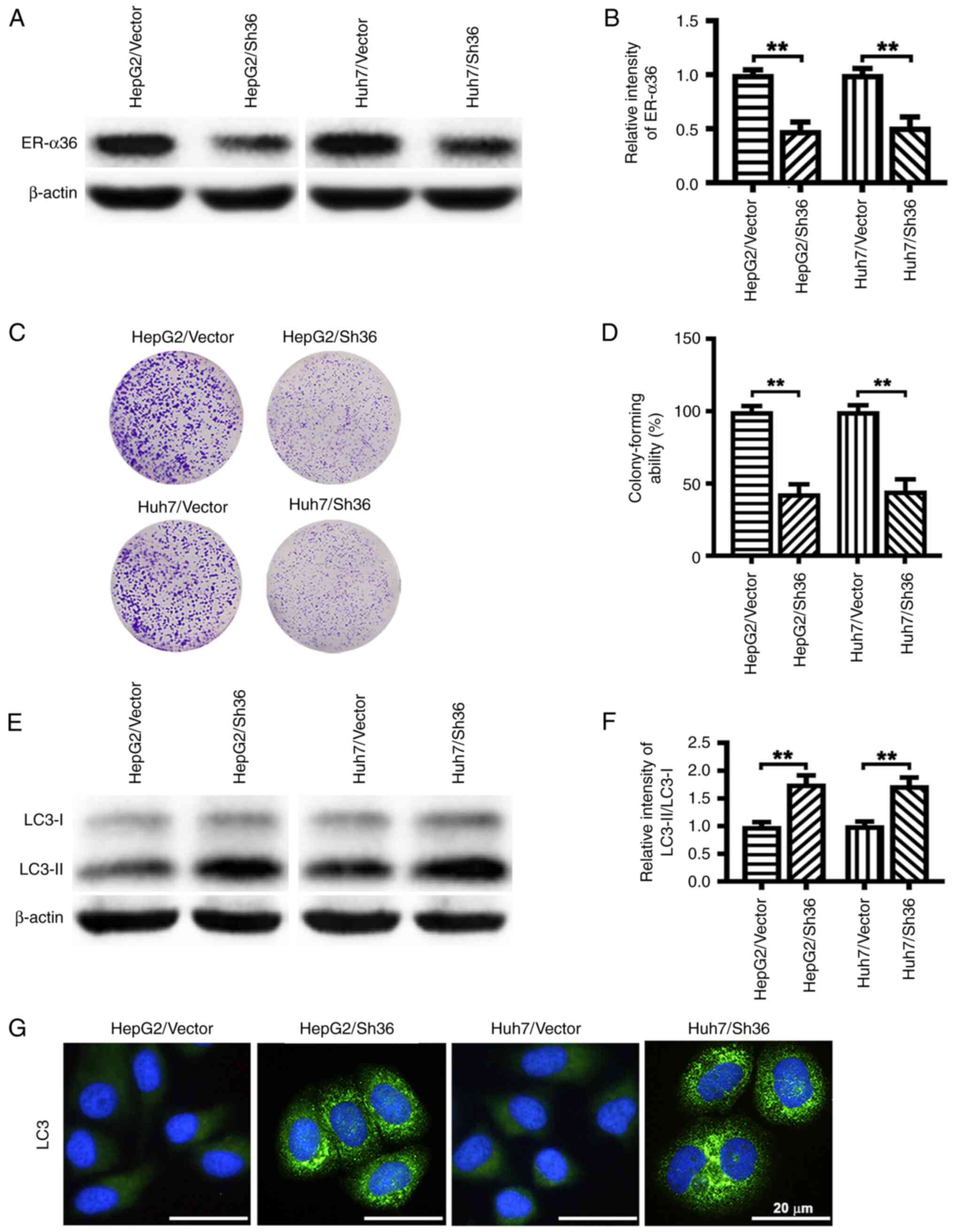

ER-α36 knockdown attenuates the

proliferation of liver cancer cells and promotes the accumulation

of autophagosomes

To test the role of ER-α36 in the proliferation and

autophagy of liver cancer cells, HepG2/Sh36 and Huh7/Sh36 cells

were prepared by transfection with an ER-α36 specific shRNA

expression vector, and HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector control cells

were prepared by transfection with an empty expression vector. The

successful knockdown of ER-α36 expression was verified by western

blotting (Fig. 1A and B). The

results of the colony formation assay revealed that ER-α36

knockdown attenuated the colony-forming ability of the liver cancer

cells (Fig. 1C and D). The

knockdown of ER-α36 expression also increased the LC3-II/LC3-I

ratio as revealed by western blot analysis (Fig. 1E and F), and increased the number

of LC3-II puncta as shown by IF staining (Fig. 1G). These findings suggest that

ER-α36 knockdown promoted autophagosome formation in the liver

cancer cells.

ER-α36 knockdown blocks autophagic

flux and autophagic degradation

The effect of ER-α36 knockdown on autophagic flux

was assessed. Western blotting revealed that the expression of p62,

a marker of autophagic flux, was increased in the HepG2/Sh36 and

Huh7/Sh36 cells compared with that in the respective empty

vector-transfected cells, suggesting that ER-α36 downregulation

impaired autophagic flux (Fig. 2A and

B). The transfected liver cancer cells were co-transfected with

pmCherry-EGFP-LC3b to monitor autophagy. In this system,

autophagosomes appear as yellow puncta, due to a combination of GFP

and mCherry fluorescence, whereas autolysosomes, formed by

autophagosome-lysosomal fusion, are identified by mCherry red

fluorescence only. This occurs because when autophagosomes fuse

with lysosomes, GFP is quenched by the acidic environment, whereas

mCherry remains fluorescent. The liver cancer cells with ER-α36

knockdown exhibited significantly increased numbers of yellow

puncta, indicative of autophagosomes, with occasional red dots

representing autolysosomes, suggesting that ER-α36 knockdown

blocked autophagic flux, thereby resulting in the accumulation of

autophagosomes (Fig. 2C and D).

Additionally, when the autophagosome-lysosome fusion inhibitor CQ

was used to treat the cells, western blotting revealed that ER-α36

knockdown increased the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio in the absence of CQ,

but caused no further increase in the presence of CQ. This suggests

that ER-α36 knockdown increased the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio due to

impaired autophagosome degradation (Fig. 2E and F). Furthermore, ER-α36

downregulation led to the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins,

suggesting that substrate degradation was inhibited (Fig. 2G and H). Taken together, these

findings indicate that ER-α36 knockdown impaired autophagic flux by

inhibiting the degradation of autophagosomes.

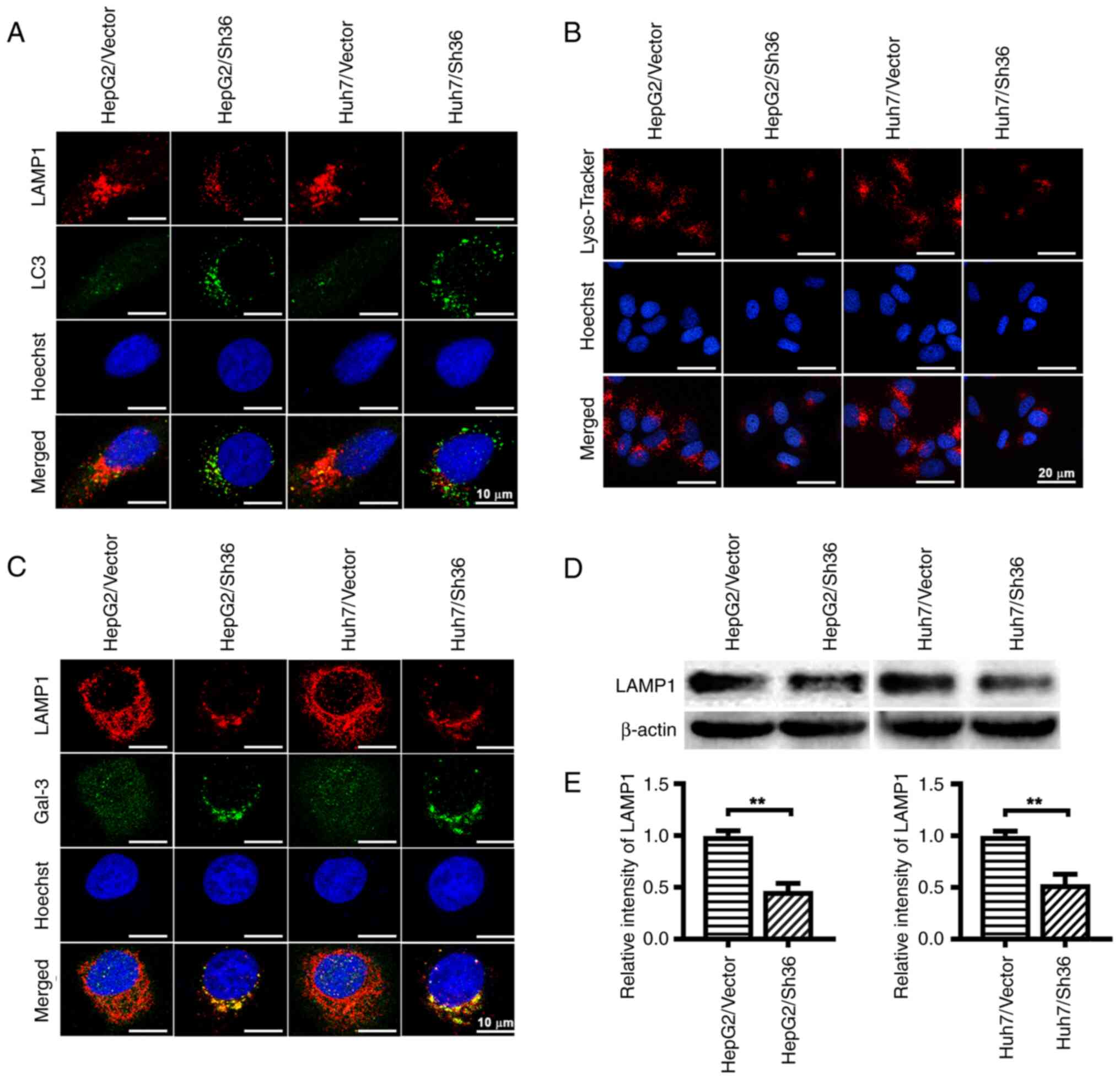

ER-α36 knockdown induces lysosomal

damage and LMP

To determine whether the autophagic degradation

defect induced by ER-α36 knockdown was due to impaired

autophagosome-lysosome fusion or defective lysosomal degradation,

IF staining of LC3 (green) and LAMP1 (red) was performed to assess

their co-localization (yellow) in liver cancer cells with different

levels of ER-α36 expression. Fewer red LAMP1 puncta and yellow

co-localization signals were observed in the HepG2/Sh36 and

Huh7/Sh36 cells compared with those in the corresponding vector

control cells (Fig. 3A),

suggesting that ER-α36 knockdown blocked autophagosome-lysosome

fusion, thereby contributing to the impairment of autophagic flux

in liver cancer cells.

Since lysosomal dysfunction can lead to autophagic

flux blockage and the accumulation of lysosomal substrates

(27), lysosomal integrity was

examined. A significant reduction in the Lyso-Tracker-staining of

lysosomes was observed in the HepG2/Sh36 and Huh7/Sh36 cells

compared with those in the respective vector control cells

(Fig. 3B), suggesting that ER-α36

downregulation compromised the acidic environment within lysosomes.

An increase in the pH of the lysosomal lumen is a known indicator

of LMP (28). As shown in Fig. 3C, IF staining revealed prominent

Gal-3 puncta in the HepG2/Sh36 and Huh7/Sh36 cells, whereas they

were only faintly visible in the vector control cells. In addition,

western blotting revealed that LAMP1 expression in the HepG2/Sh36

and Huh7/Sh36 cells was decreased compared with that in the vector

control cells (Fig. 3D and E).

These data indicate that ER-α36 knockdown disrupted lysosomal

integrity.

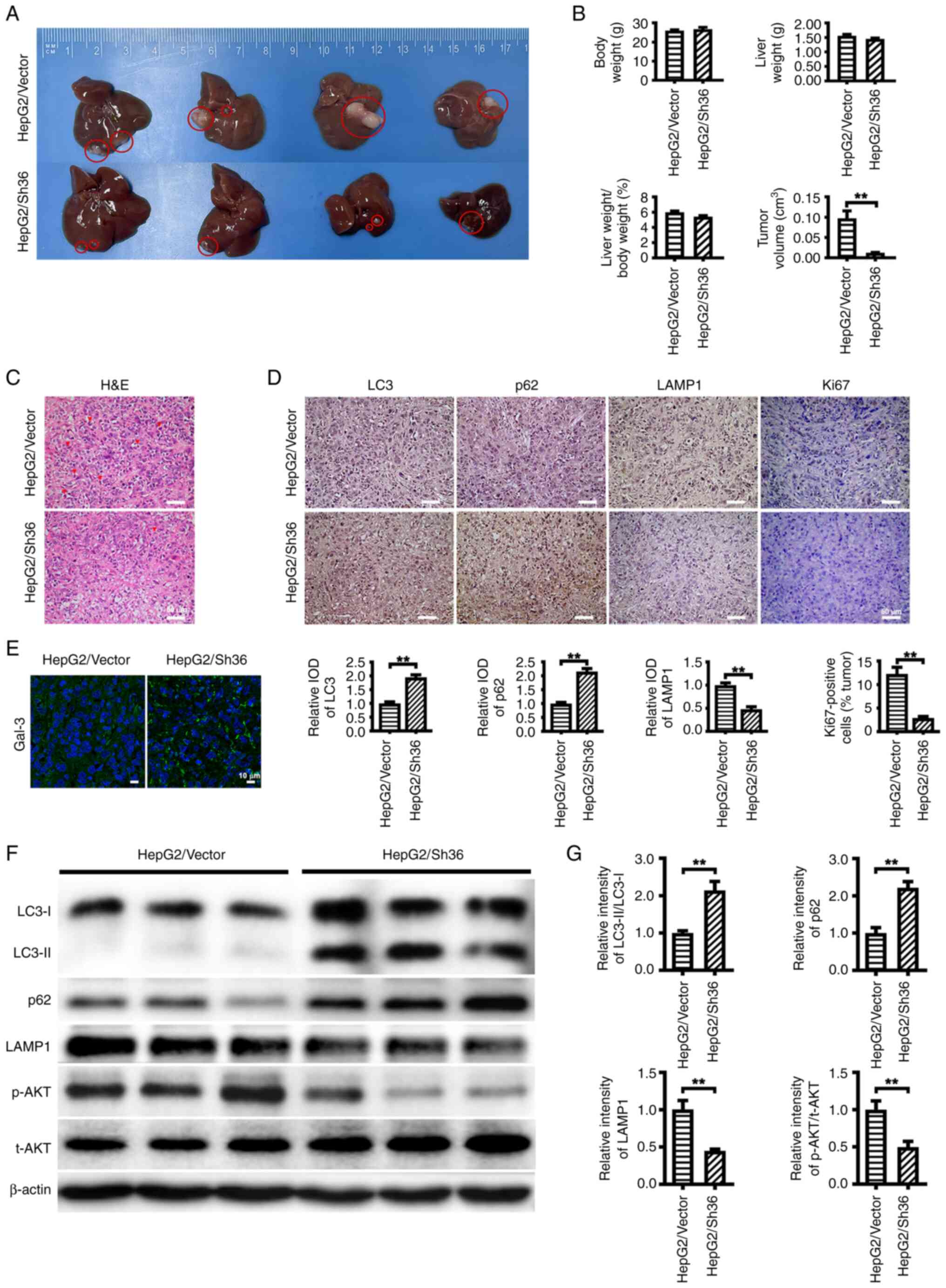

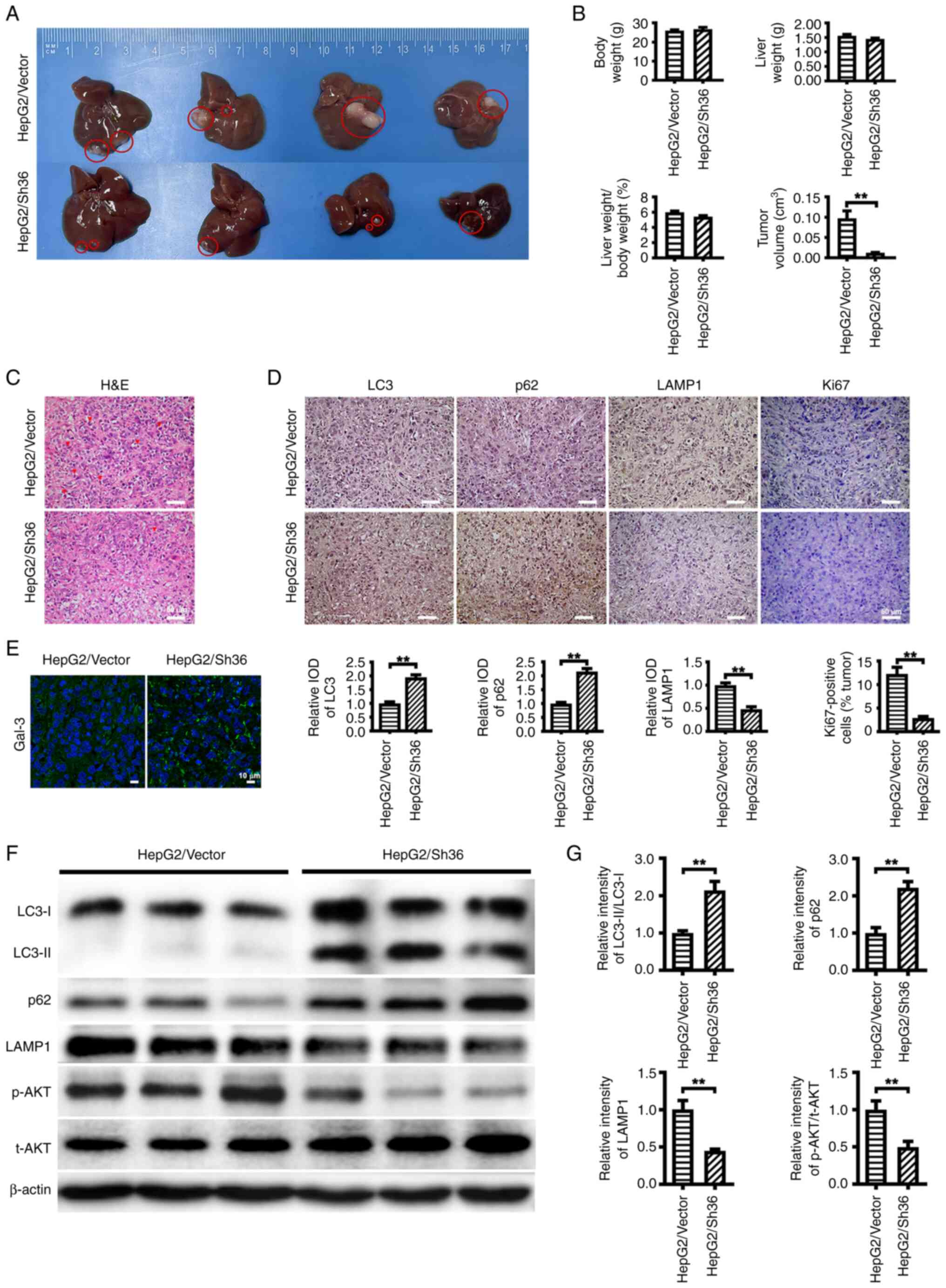

ER-α36 knockdown suppresses the

malignant proliferation of liver cancer cells and induces LMP

To investigate the function of ER-α36 in the

malignant proliferation of liver cancer cells in vivo, nude

mice were intrahepatically injected with HepG2/Vector cells or

HepG2/Sh36 cells to establish an orthotopic liver xenograft tumor

model for 28 days. While tumors were formed in the livers of all

mice, the tumor volumes formed by the HepG2/Sh36 cells were

significantly smaller than those formed by the HepG2/Vector cells.

The liver weight, body weight and ratio of liver weight to body

weight exhibited no significant differences between the two groups

(Fig. 4A and B). Furthermore, a

reduced number of pathological karyomitoses and Ki67-positive cells

were detected in the tumors formed from the HepG2/Sh36 cells by

H&E and IHC, suggesting that ER-α36 is involved in the

malignant proliferation of HepG2 cells (Fig. 4C and D). Western blot analysis and

IHC also revealed an increased LC3-II/I ratio and p62 expression

level, and decreased LAMP1 expression in the tumor tissues formed

by the HepG2/Sh36 cells compared with those in the tumors formed by

the HepG2/Vector cells (Fig. 4D, F and

G). In addition, IF staining demonstrated an increase in the

number of Gal-3 puncta in the tumors formed by the HepG2/Sh36 cells

compared with those formed by the HepG2/Vector cells (Fig. 4E). These results indicate that

ER-α36 knockdown suppressed the tumor proliferation of HepG2 cells

and induced LMP in vivo.

| Figure 4.ER-α36 knockdown suppresses the

malignant proliferation of liver cancer cells and induces lysosomal

membrane permeabilization. (A) Representative images of liver

tumors from nude mice intrahepatically injected with HepG2 cells

expressing different ER-α36 levels, harvested at 28 days

post-injection. (B) Quantitative analysis of liver tumor volume,

liver weight, body weight and the ratio of liver weight to body

weight. (C) Representative H&E staining images showing

pathological karyomitosis changes. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D)

Immunohistochemical staining of LC3, p62, LAMP1 and Ki67 with

corresponding IOD values. Scale bar, 50 µm. (E) Immunofluorescence

staining of Gal-3 in the tumors formed from the transfected HepG2

cells. Scale bar, 10 µm. (F) Western blotting results showing the

levels of LC3-II and LC3-II, p62, LAMP1, p-AKT and t-AKT in the

tumors, and (G) quantitative analyses of the LC3-II/LC3-I and

p-AKT/t-AKT ratios, and p62 and LAMP1 expression levels. β-actin

was used as the internal loading control. Data are presented as the

mean ± SEM. **P<0.01. ER, estrogen receptor; H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1 light

chain 3; LAMP1, lysosome-associated membrane protein 1; Gal-3,

galectin-3; IOD, integrated optical density; p-, phosphorylated;

t-, total; Sh36, transfected with ER-α36 specific short hairpin RNA

expression vector; Vector, transfected with empty vector. |

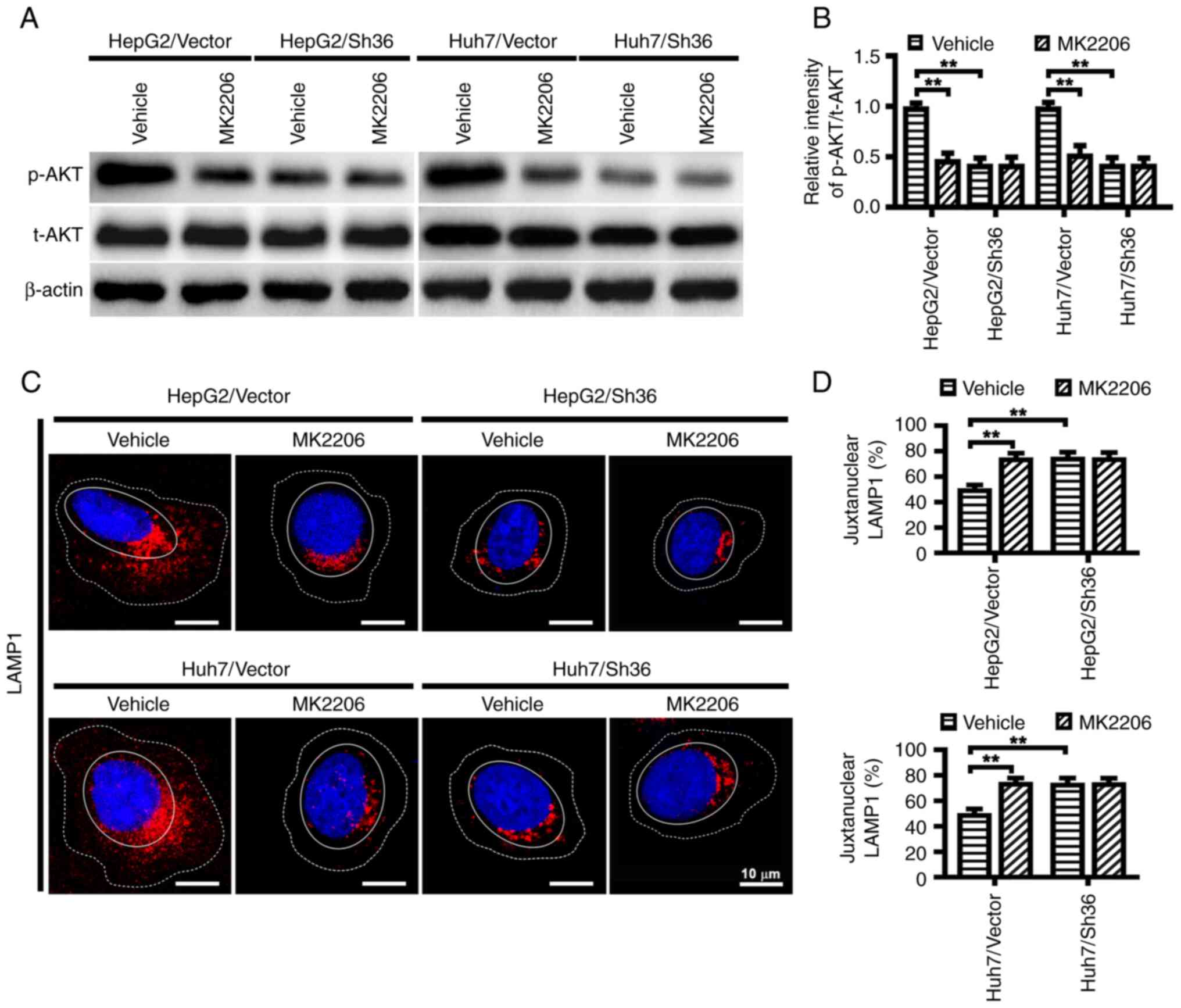

ER-α36 knockdown decreases AKT

phosphorylation and influences lysosomal localization in liver

cancer cells

AKT signaling, a typical event in ER-α36-mediated

rapid estrogenic signaling, has been reported to influence

lysosomal localization (10,29).

To determine whether ER-α36 mediated AKT activation is involved in

the regulation of lysosomal localization in liver cancer cells, the

phosphorylation levels of AKT in the HepG2 and Huh7 cells with and

without ER-α36 knockdown and in the tumors formed from them were

examined. Decreased AKT phosphorylation at Ser 473 was observed in

the liver cancer cells with ER-α36 knockdown and in the tumors

formed from them compared with that in the corresponding vector

controls (Figs. 4F and G, 5A and B). In addition, when compared with

the HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector cells, an accumulation of LAMP1

was observed at the juxtanuclear region in the HepG2/Sh36 and

Huh7/Sh36 cells (Fig. 5C and D),

consistent with earlier reports that the AKT inhibitor MK-2206

promotes the juxtanuclear clustering of lysosomes (29). However, in the present study,

MK-2206 did not further reduce AKT phosphorylation or influence

lysosome localization in HepG2/Sh36 and Huh7/Sih6 cells (Fig. 5C and D). These results indicate

that ER-α36 expression knockdown attenuated AKT phosphorylation,

which then led to the juxtanuclear clustering of lysosomes.

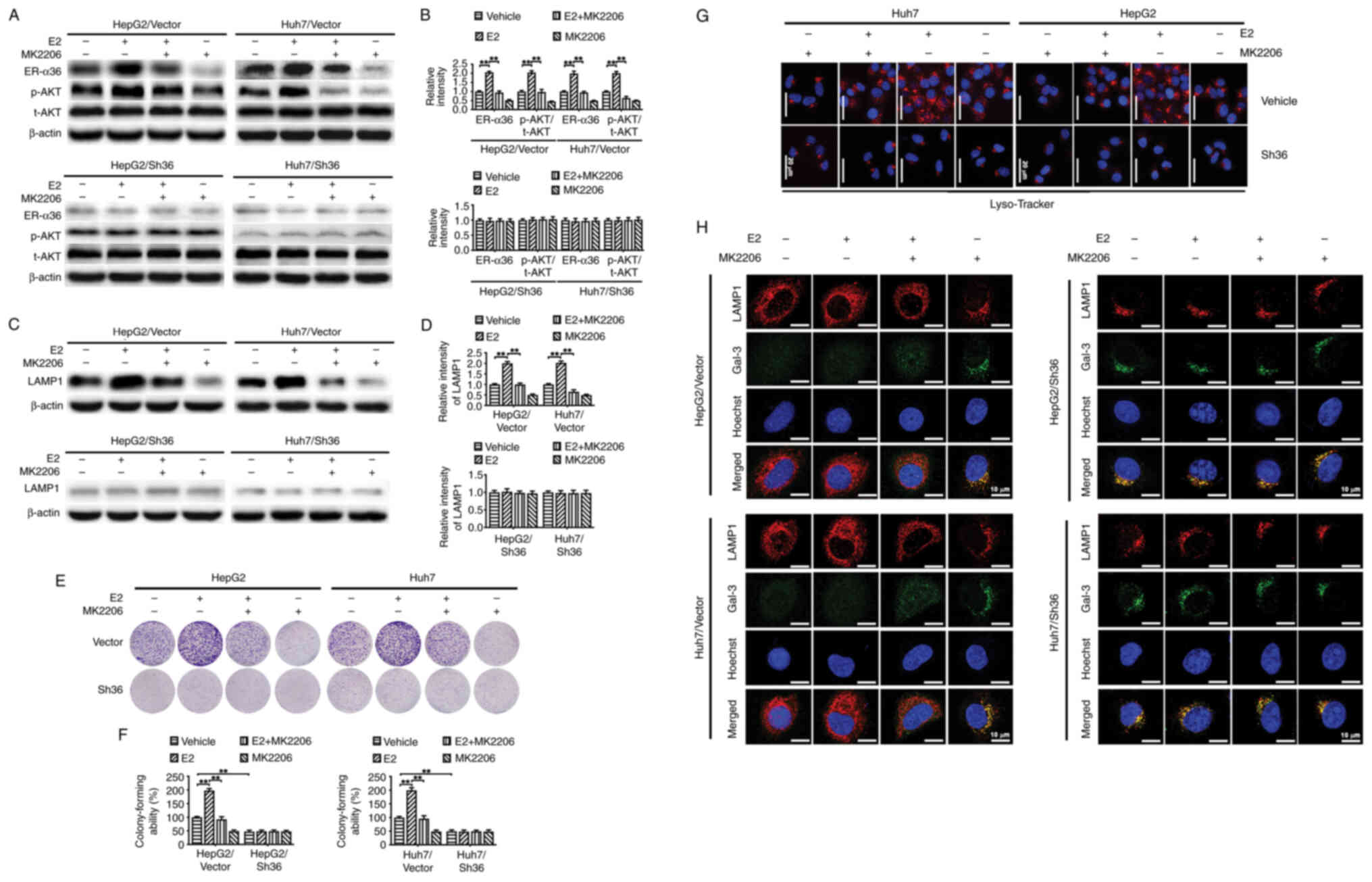

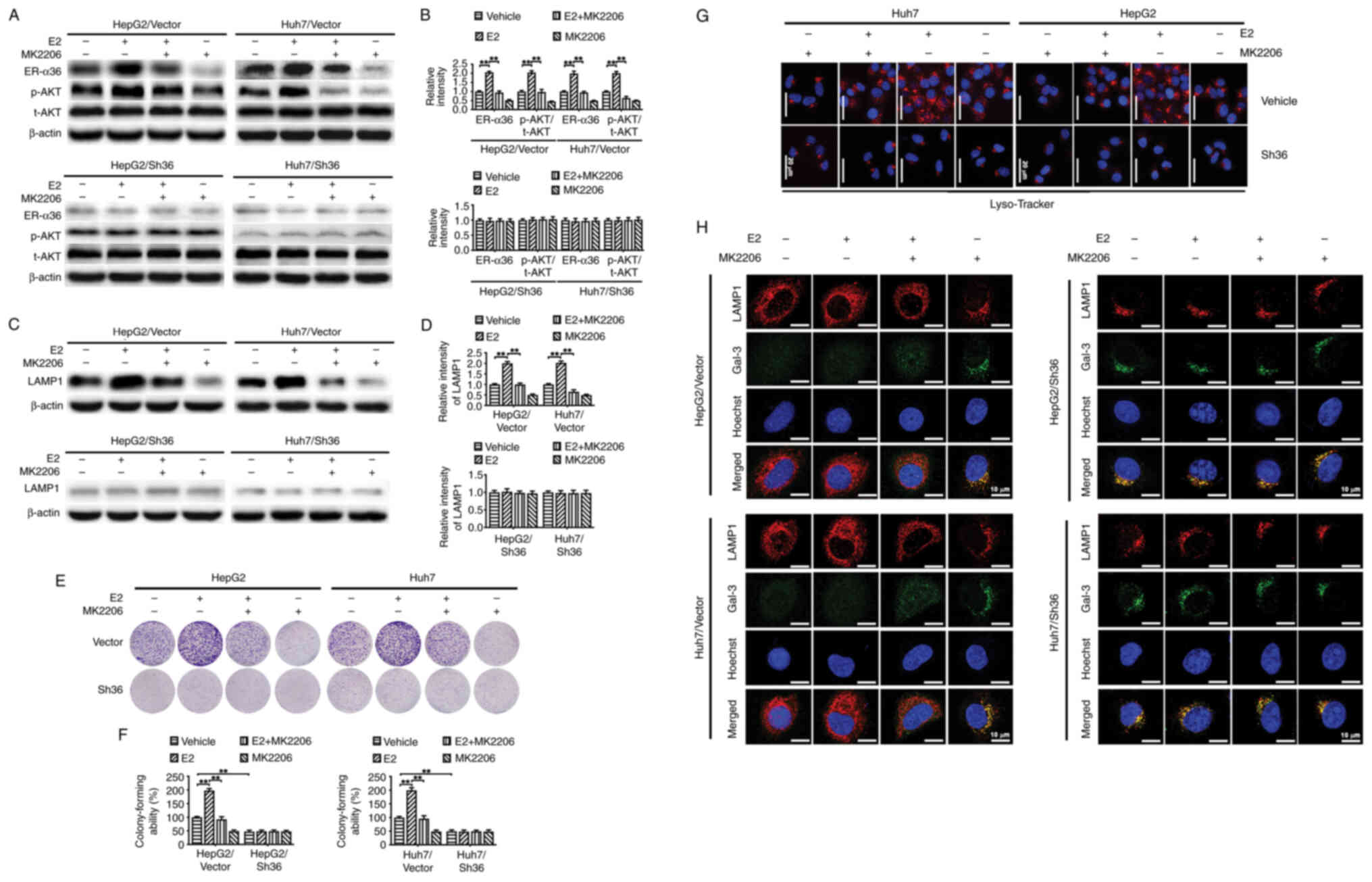

AKT is involved in the ER-α36

knockdown-induced changes in lysosomal localization and LMP in

liver cancer cells

To examine the effect of AKT on ER-α36 regulated LMP

and lysosomal localization, which influence the proliferation of

liver cancer cells, the transfected liver cancer cells were treated

with E2 and/or MK-2206. It was observed that treatment of the

HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector cells with E2 upregulated AKT

phosphorylation at Ser 473 and increased the colony-forming ability

of the cells, and these effects were abrogated by MK-2206 (Fig. 6A, B, E and F). This is consistent

with the previous finding that AKT signaling is involved in

ER-α36-mediated rapid estrogenic signaling and stimulation of cell

proliferation (10). The E2

treatment also upregulated LAMP1 expression (Fig. 6C, D and H), increased Lyso-Tracker

fluorescence intensity (Fig. 6G)

and re-localized lysosomes to the cell periphery in the

HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector cells (Fig. 6G), while MK-2206 abrogated all

these E2-induced effects. In addition, a diffuse distribution of

Gal-3 in the cytoplasm and nucleus was observed in E2-treated

HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector cells, while a punctate pattern was

observed in the HepG2/Vector and Huh7/Vector cells treated with the

combination of E2 and MK-2206 (Fig.

6H). By contrast, these phenomena were almost undetectable in

the HepG2/Sh36 and Huh7/Sh36 cells. These findings strongly suggest

that AKT is involved in the lysosomal localization and LMP changes

associated with ER-α36 knockdown.

| Figure 6.AKT is involved in the lysosomal

localization and LMP induced by ER-α36 knockdown. Transfected liver

cancer cells with different levels of ER-α36 expression were

treated with MK-2206 (100 nM) for 6 h, followed by E2 (1 nM) for 30

min, and the same volume of alcohol was used as a vehicle control.

(A) Representative western blots of ER-α36, p-AKT and AKT, and (B)

quantitative analysis of ER-α36 expression and the p-AKT/t-AKT

ratio. In subsequent assays, the transfected liver cancer cells

were treated with MK-2206 (100 nM) for 6 h, followed by E2 (1 nM)

for 24 h. (C) Representative western blots of LAMP1 and (D)

quantitative analysis of LAMP1 expression. (E) Representative

images of colony formation by the liver cancer cells and (F)

quantitative analysis of colony forming ability. Data are presented

as the mean ± SEM. **P<0.01. (G) Fluorescence microscopy images

of the cells following staining with Lyso-Tracker Red. Scale bar,

20 µm. (H) Co-localization of Gal-3 (green) and LAMP1 (red) in the

cells as revealed by immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar, 10 µm.

ER, estrogen receptor; E2, 17β-estradiol; Gal-3, galectin-3; p-,

phosphorylated; t-, total; LAMP1, lysosome-associated membrane

protein 1; Sh36, transfected with ER-α36 specific short hairpin RNA

expression vector; Vector, transfected with empty vector. |

Discussion

The present study provides evidence that the

knockdown of ER-α36 impaired autophagic flux and inhibited the

malignant proliferation of HepG2 and Huh7 human liver cancer cells

in vivo and in vitro. ER-α36 knockdown also induced

LMP as well as lysosomal dysfunction, including pH elevation,

impaired protein degradation and the juxtanuclear clustering of

lysosomes. These findings suggest that the maintenance of normal

lysosomal function is one of the key roles of ER-α36 in liver

cancer cells.

Previous studies have suggested that ER-α36 is

involved in liver tumorigenesis (10), that ER-α36 mRNA levels gradually

increase from normal liver tissue to cirrhotic liver and liver

carcinoma tissues (7), and that

upregulated ER-α36 expression is associated with primary liver

cancer (9). In addition, the

knockdown of ER-α36 expression has been shown to attenuate the

metastasis of HepG2 and Huh7 cells by downregulating

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the Src signaling pathway

(24). Furthermore, ER-α36 has

been demonstrated to be a prognostic factor in breast cancer

(30). However, the molecular

mechanism by which ER-α36 promotes cancer cell proliferation is

unclear.

Impaired autophagy has been linked to various

pathological conditions in humans, including liver dysfunction and

carcinogenesis (31). In

glioblastoma cells, ER-α36 has been reported to counteract

tamoxifen-mediated cell apoptosis by promoting autophagy via

inactivation of the AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)

signaling pathway (12).

Furthermore, ER-α36 promotes autophagy during the development of

acquired tamoxifen resistance (12,32),

and its expression level has been shown to correlate with that of

p62 in a three-dimensional culture model (12).

The present study also demonstrated that ER-α36

knockdown attenuated the malignant proliferation of liver cancer

cells and impaired autophagic flux. Specifically, ER-α36 knockdown

increased the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio and p62 expression levels in HepG2

and Huh7 cells, as well as in the tumor tissues formed by these

cells in mice, compared with those in the corresponding controls.

Furthermore, the use of a double-tagged LC3 construct

(pmCherry-EGFP-LC3b) revealed that autophagic flux in

ER-α36-knockdown cells was impaired compared with that in the

control cells. To further elucidate the dynamics of autophagy, CQ

was used as a late-stage autophagy inhibitor to determine whether

ER-α36 knockdown promotes or inhibits autophagy. CQ inhibits

autophagosome degradation; therefore, when CQ treatment is

administered, any observed changes in the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio

represent autophagosome synthesis, whereas in the absence of CQ,

they represent the combined effects of both autophagosome synthesis

and degradation (33–36). In the present study, ER-α36

knockdown increased the LC3-II/LC3-I ratio in the absence of CQ,

but not its presence. This suggests that ER-α36 knockdown induces

the aggregation of autophagosomes due to impaired autophagosome

degradation, indicating a blockade of autophagic flux.

The colocalization of LC3 with LAMP1 in the HepG2

and Huh7 cells was observed to decrease following ER-α36 knockdown

in the present study, suggesting that ER-α36 downregulation

disrupts autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Intact lysosomes are highly

acidic, and this acidic environment is maintained by the integrity

of the lysosomal membrane (37).

Loss of lysosomal integrity results in elevated lysosomal pH, which

can impair autophagic degradation and block autophagic flux

(13,38–40).

In the present study, decreased LAMP1 expression was observed

following ER-α36 knockdown, suggesting a potential loss of

lysosomal membrane integrity that may affect lysosomal

function.

Gal-3 staining, a well-established indicator of

lysosomal injury, is commonly used to assess lysosomal integrity

(41). In the present study, the

accumulation of Gal-3-positive puncta was observed in the liver

cancer cells with ER-α36 knockdown in vivo and in

vitro, further supporting a role of ER-α36 in the regulation of

LMP. Together, these findings suggest that ER-α36 downregulation

impairs autophagic flux and inhibits liver cancer cell

proliferation.

The positioning of lysosomes within the cytoplasm

has been shown to influence the rate of autophagosome-lysosome

fusion, and thus regulate autophagic flux (42). For example, the knockout of

biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles complex-1, which

facilitates the kinesin-dependent movement of lysosomes toward the

cell periphery, results in the juxtanuclear clustering of lysosomes

and impairs both their encounter and fusion with autophagosomes

(43). The reduction in encounters

occurs due to the inability of lysosomes to move toward the

peripheral cytoplasm, where autophagosomes are predominantly formed

(44). Notably, the peripheral

localization of lysosomes has been associated with pathological

processes, including cancer cell growth, invasion and metastasis

(45), whereas the accumulation of

lysosomes at the juxtanuclear region is associated with reduced

proteinase secretion and a reduction in the invasiveness of tumor

cells (46). In the present study,

ER-α36 knockdown led to the juxtanuclear clustering of lysosomes,

which may impair the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes,

thereby inhibiting autophagic flux.

The lysosome functions as a central hub for

signaling networks (45). AKT

signaling has been shown to regulate lysosomal positioning

(29,47). Juxtanuclear clustering of lysosomes

has been shown to delay the activation of mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1),

mTORC2 and AKT following serum replenishment (48). By contrast, the peripheral

clustering of lysosomal mTORC1 brings it closer to activated AKT,

which predominantly localizes near to the plasma membrane during

the recovery phase following serum starvation (42). Notably, ER-α36-mediated rapid

estrogen signaling involves the AKT signaling pathway, which has

been implicated in liver tumorigenesis (10). In the present study, it was found

that ER-α36 downregulation induced a reduction in AKT

phosphorylation and the accumulation of LAMP1 in the juxtanuclear

region. In addition, the inhibition of AKT phosphorylation was

found to block ER-α36-mediated effects, including its promotion of

cell proliferation and induction of lysosomal dispersal to the cell

periphery. A previous study reported that decreased AKT expression

is associated with elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels, which

induce LMP and lysosomal damage (49). In the present study, the role of

ER-α36-mediated rapid estrogen signaling in LMP was investigated,

and the results revealed that ER-α36 downregulation reduced AKT

phosphorylation and LMP in vivo and in vitro.

Treatment with E2 upregulated ER-α36 and LAMP1 expression,

activated AKT and increased the Lyso-Tracker staining of lysosomes

in empty vector-transfected HepG2 and Huh7 cells; all these effects

were attenuated by MK-2206. However, these phenomena were almost

undetectable in the HepG2 and Huh7 cells with ER-α36 knockdown,

suggesting AKT is involved in the lysosomal localization and LMP

changes associated with ER-α36 knockdown.

However, some important issues remain to be

explored. LMP often results in the translocation of lysosomal

cathepsins from the lysosomal lumen to the cytoplasm, a process

implicated in the regulation of various cell death pathways

(16). In the present study,

Lyso-Tracker Red staining and the assessment of lysosomal integrity

via LAMP1 and Gal-3 puncta assays provided evidence of LMP.

However, additional assays such as cathepsin release or dextran

leakage assays are necessary for further confirmation. Whether all

these mechanisms are involved in the ER-α36-induced proliferation

of liver cancer cells remains to be established.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that

ER-α36 knockdown induced LMP, disrupted lysosomal membrane

integrity, altered lysosomal localization and impeded autophagic

activity via the inactivation of AKT. These effects may all

contribute to the inhibition of liver cancer cell proliferation

in vivo and in vitro. Thus, lysosomal dysfunction may

be an underlying mechanism by which ER-α36 promotes liver cancer

development.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81872040) and the Research Fund of

Jianghan University (grant no. 2021jczx-002).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HuH, XW and ZWe were responsible for methodology,

investigation, managing, storing and maintaining data to ensure its

reliability and availability, analysis and writing the original

draft of the manuscript. AW, XF, HaH and ZWu were responsible for

the methodology, investigation and the acquisition of data. XS and

BS were responsible for analysis and interpretation of data,

supervision, reviewing and editing the manuscript. QC, XH and HZ

were responsible for the methodology, resources and the acquisition

of data. YL and ZF were responsible for conceptualization,

reviewing and editing the manuscript, supervision and funding

acquisition. ZF and HuH confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Al experimental procedures were performed in

compliance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for

the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the

Ethics Committee of Jianghan University (Wuhan, China; approval no.

JHDXLL2024-086).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN and Jemal A:

Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:12–49.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Han B, Zheng R, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K,

Chen R, Li L, Wei W and He J: Cancer incidence and mortality in

China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. 4:47–53. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kasarinaite A, Sinton M, Saunders PTK and

Hay DC: The influence of sex hormones in liver function and

disease. Cells. 12:16042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Iavarone M, Lampertico P, Seletti C,

Donato MF, Ronchi G, del Ninno E and Colombo M: The clinical and

pathogenetic significance of estrogen receptor-beta expression in

chronic liver diseases and liver carcinoma. Cancer. 98:529–534.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tu BB, Lin SL, Yan LY, Wang ZY, Sun QY and

Qiao J: ER-α36, a novel variant of estrogen receptor α, is involved

in EGFR-related carcinogenesis in endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 205:227.e221–226. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Miceli V, Cocciadiferro L, Fregapane M,

Zarcone M, Montalto G, Polito LM, Agostara B, Granata OM and

Carruba G: Expression of wild-type and variant estrogen receptor

alpha in liver carcinogenesis and tumor progression. OMICS.

15:313–317. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Su X, Xu X, Li G, Lin B, Cao J and Teng L:

ER-α36: A novel biomarker and potential therapeutic target in

breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 7:1525–1533. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhang J, Ren J, Wei J, Chong CC, Yang D,

He Y, Chen GG and Lai PB: Alternative splicing of estrogen receptor

alpha in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 16:9262016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

You H, Meng K and Wang ZY: The ER-α36/EGFR

signaling loop promotes growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

Steroids. 134:78–87. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Li G, Zhang J, Jin K, He K, Zheng Y, Xu X,

Wang H, Wang H, Li Z, Yu X, et al: Estrogen receptor-α36 is

involved in development of acquired tamoxifen resistance via

regulating the growth status switch in breast cancer cells. Mol

Oncol. 7:611–624. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Qu C, Ma J, Zhang Y, Han C, Huang L, Shen

L, Li H, Wang X, Liu J, Zou W, et al: Estrogen receptor variant

ER-α36 promotes tamoxifen agonist activity in glioblastoma cells.

Cancer Sci. 110:221–234. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Qi Z, Yang W, Xue B, Chen T, Lu X, Zhang

R, Li Z, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Han F, et al: ROS-mediated lysosomal

membrane permeabilization and autophagy inhibition regulate

bleomycin-induced cellular senescence. Autophagy. 20:2000–2016.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yamamoto H, Zhang S and Mizushima N:

Autophagy genes in biology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 24:382–400.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gros F and Muller S: The role of lysosomes

in metabolic and autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol. 19:366–383.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Xiang L, Lou J, Zhao J, Geng Y, Zhang J,

Wu Y, Zhao Y, Tao Z, Li Y, Qi J, et al: Underlying mechanism of

lysosomal membrane permeabilization in CNS injury: A literature

review. Mol Neurobiol. 62:626–642. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Nie B, Liu X, Lei C, Liang X, Zhang D and

Zhang J: The role of lysosomes in airborne particulate

matter-induced pulmonary toxicity. Sci Total Environ.

919:1708932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Eriksson I and Öllinger K: Lysosomes in

cancer-at the crossroad of good and evil. Cells. 13:4592024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Li Z, Zhang Y, Lei J and Wu Y: Autophagy

in oral cancer: Promises and challenges (Review). Int J Mol Med.

54:1162024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ballabio A and Bonifacino JS: Lysosomes as

dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 21:101–118. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cao M, Luo X, Wu K and He X: Targeting

lysosomes in human disease: From basic research to clinical

applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 6:3792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Davidson SM and Vander Heiden MG: Critical

functions of the lysosome in cancer biology. Annu Rev Pharmacol

Toxicol. 57:481–507. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Weber RA, Yen FS, Nicholson SPV, Alwaseem

H, Bayraktar EC, Alam M, Timson RC, La K, Abu-Remaileh M, Molina H

and Birsoy K: Maintaining iron homeostasis is the key role of

lysosomal acidity for cell proliferation. Mol Cell.

77:645–655.e647. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Wang R, Chen J, Yu H, Wei Z, Ma M, Ye X,

Wu W, Chen H and Fu Z: Downregulation of estrogen receptor-α36

expression attenuates metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

Environ Toxicol. 37:1113–1123. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhang X, Deng H and Wang ZY: Estrogen

activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase is mediated by

ER-α36 in ER-positive breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol

Biol. 143:434–443. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang ZY and Yin L: Estrogen receptor

alpha-36 (ER-α36): A new player in human breast cancer. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 418:193–206. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kendall RL and Holian A: The role of

lysosomal ion channels in lysosome dysfunction. Inhal Toxicol.

33:41–54. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chen Y, Zhu S, Liao T, Wang C, Han J, Yang

Z, Lu X, Hu Z, Hu J, Wang X, et al: The HN protein of Newcastle

disease virus induces cell apoptosis through the induction of

lysosomal membrane permeabilization. PLoS Pathog. 20:e10119812024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu B, Liu DA, Guan L, Myint PK, Chin L,

Dang H, Xu Y, Ren J, Li T, Yu Z, et al: Stiff matrix induces

exosome secretion to promote tumour growth. Nat Cell Biol.

25:415–424. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li Q, Sun H, Zou J, Ge C, Yu K, Cao Y and

Hong Q: Increased expression of estrogen receptor α-36 by breast

cancer oncogene IKKε promotes growth of ER-negative breast cancer

cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 31:833–841. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Klionsky DJ, Petroni G, Amaravadi RK,

Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, Boya P, Pedro JM, Cadwell K, Cecconi F,

Choi AM, et al: Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J.

40:e1088632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Koirala M and DiPaola M: Overcoming cancer

resistance: Strategies and modalities for effective treatment.

Biomedicines. 12:18012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T and

Kominami E: Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of

endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy. 1:84–91. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ju JS, Varadhachary AS, Miller SE and

Weihl CC: Quantitation of ‘autophagic flux’ in mature skeletal

muscle. Autophagy. 6:929–935. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rubinsztein DC, Cuervo AM, Ravikumar B,

Sarkar S, Korolchuk V, Kaushik S and Klionsky DJ: In search of an

‘autophagomometer’. Autophagy. 5:585–589. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ou M, Cho HY, Fu J, Thein TZ, Wang W,

Swenson SD, Minea RO, Stathopoulos A, Schönthal AH, Hofman FM, et

al: Inhibition of autophagy and induction of glioblastoma cell

death by NEO214, a perillyl alcohol-rolipram conjugate. Autophagy.

19:3169–3188. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Nakamura S, Akayama S and Yoshimori T:

Autophagy-independent function of lipidated LC3 essential for TFEB

activation during the lysosomal damage responses. Autophagy.

17:581–583. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chan H, Li Q, Wang X, Liu WY, Hu W, Zeng

J, Xie C, Kwong TNY, Ho IHT, Liu X, et al: Vitamin D (3) and

carbamazepine protect against Clostridioides difficile infection in

mice by restoring macrophage lysosome acidification. Autophagy.

18:2050–2067. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gu H, Qiu H, Yang H, Deng Z, Zhang S, Du L

and He F: PRRSV utilizes MALT1-regulated autophagy flux to switch

virus spread and reserve. Autophagy. 20:2697–2718. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhang J, Zeng W, Han Y, Lee WR, Liou J and

Jiang Y: Lysosomal LAMP proteins regulate lysosomal pH by direct

inhibition of the TMEM175 channel. Mol Cell. 83:2524–2539.e2527.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Tanaka T, Warner BM, Michael DG, Nakamura

H, Odani T, Yin H, Atsumi T, Noguchi M and Chiorini JA: LAMP3

inhibits autophagy and contributes to cell death by lysosomal

membrane permeabilization. Autophagy. 18:1629–1647. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Korolchuk VI, Saiki S, Lichtenberg M,

Siddiqi FH, Roberts EA, Imarisio S, Jahreiss L, Sarkar S, Futter M,

Menzies FM, et al: Lysosomal positioning coordinates cellular

nutrient responses. Nat Cell Biol. 13:453–460. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Jia R, Guardia CM, Pu J, Chen Y and

Bonifacino JS: BORC coordinates encounter and fusion of lysosomes

with autophagosomes. Autophagy. 13:1648–1663. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhao YG, Codogno P and Zhang H: Machinery,

regulation and pathophysiological implications of autophagosome

maturation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 22:733–750. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Pu J, Schindler C, Jia R, Jarnik M,

Backlund P and Bonifacino JS: BORC, a multisubunit complex that

regulates lysosome positioning. Dev Cell. 33:176–188. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Steffan JJ, Dykes SS, Coleman DT, Adams

LK, Rogers D, Carroll JL, Williams BJ and Cardelli JA: Supporting a

role for the GTPase Rab7 in prostate cancer progression. PLoS One.

9:e878822014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Palma M, Riffo E, Farias A,

Coliboro-Dannich V, Espinoza-Francine L, Escalona E, Amigo R,

Gutiérrez JL, Pincheira R and Castro AF: NUAK1 coordinates growth

factor-dependent activation of mTORC2 and Akt signaling. Cell

Biosci. 13:2322023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Jia R and Bonifacino JS: Lysosome

positioning influences mTORC2 and AKT signaling. Mol Cell.

75:26–38. e232019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Seo SU, Woo SM, Lee HS, Kim SH, Min KJ and

Kwon TK: mTORC1/2 inhibitor and curcumin induce apoptosis through

lysosomal membrane permeabilization-mediated autophagy. Oncogene.

37:5205–5220. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|