Introduction

The majority of the human genome consists of regions

that do not code for proteins and within these regions are the

non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which are broadly classified as small

ncRNAs (sncRNAs) and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs). Since their discovery,

several studies have reported roles of ncRNAs as master regulators

of gene expression by acting through innumerable mechanisms

(1–4). Previous studies have shown that

microRNAs (miRNAs; miRs), RNYs-a class of ncRNAs that are

components of the Ro60 ribonucleoprotein particle-lncRNAs and

fragments derived from certain ncRNAs physically interact with

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which results in oncogenesis (5), the induction and suppression of

inflammatory processes in a neurodegenerative context (6), the induction of nephritis and lung

disease (7), the elimination of

bacterial infections (8) and the

reactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (9). In addition to this, Rodríguez-Corona

et al (10) predicted the

physical interaction of RNYs and their fragments with TLRs and

other cellular receptors, which indicate a range of signaling

pathways and cellular processes that could be regulated by

ncRNAs.

TLRs recognize unique microbial patterns known as

pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (11–15)

and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that lead to the

activation of the innate immune system. PAMPs have been associated

with molecules derived from pathogenic bacteria and viruses

(proteins and lipopeptides, LPS, RNA species, DNA and flagellin)

that activate pattern recognition receptor (PRR) families; however,

PRRs also respond to molecules from commensal organisms (16). Meanwhile, DAMPs are molecules

associated with tissue damage (heat shock proteins, transcription

factors, native RNA and DNA, tissue matrix components, such as

hyaluronan and fibronectin and humoral proteins such as

fibrinogen), which activate PRRs, particularly TLRs (17). To date, 10 TLRs have been

identified in humans (TLR1-10) (18) and 12 in mice (TLR1-9, TLR11-13)

(19), which are expressed on the

cell surface or in intracellular vesicles. Due to the importance of

TLR activation in the induction of the innate and adaptive immune

response, several studies have focused on the development of

activators and inhibitors of these receptors for the treatment of

various diseases (20–27). Currently, biomolecules are used for

the treatment of bladder cancer (28,29)

and several other biomolecules are still under study to establish

their use in clinical practice (20–22).

Previous studies reviewed information on the activation of TLRs by

miRNAs (30) and by sncRNAs,

proposing the sequential activation hypothesis in autoimmune

diseases (22,31). The purpose of the present review

was to describe the protective or harmful effects that activation

of TLRs by ncRNAs has, including the activation of these receptors

by lncRNAs and by fragments derived from ncRNAs. The present review

described the involvement of TLR-ncRNAs/fragments interactions in

other diseases such as cancer and viral infections, as well as in

neurodegenerative and neurocognitive diseases, and discussed

advances in the generation of TLR agonists and/or antagonists or

ncRNA mimics or inhibitors for the treatment of these diseases.

Advances in the study of ncRNAs/fragments-TLRs interaction could

lead to the development of clinically useful immunotherapies in the

future.

TLRs activation by ncRNAs

Currently, there is relatively little information

about the physical interaction of ncRNAs with cellular receptors.

Well-studied interactions include those between miRNAs and TLRs 7/8

and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and RNYs with TLRs 13/2 and 3/7/8,

respectively (5,7,32–37)

and recent evidence indicates TLRs interaction with lncRNAs

(38,39). In addition, Yang et al

(40) demonstrated the miRNA-1

interaction with the pore-facing G-loop of Kir2.1 via the core

sequence AAGAAC, which does not include the seed region of this

miRNA. To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence for the

interaction of other ncRNA with TLRs or other cellular receptors.

However, based on the existing evidence, it is possible that other

ncRNAs can interact with a variety of cellular receptors (10).

miRNAs

miRNAs are sncRNAs with length of ~22 nucleotides

(nt) in mature form (41–43). A study by Hansen et al

(44) demonstrated the presence of

miRNAs, with a size of 80–100 nt, known as Agotrons, which are

bound to and stabilized by Argonaute (Ago) proteins in the

cytoplasm. Although Agotrons also repress gene expression by

interacting with the 3′UTR region of their target mRNA, their main

function could be related to giving specificity to free Ago

proteins by certain RNA species.

miRNAs are produced by diverse biogenic pathways,

which seems to indicate that cells ‘secure’ the control of gene

expression by miRNAs using diverse molecular elements for their

synthesis and processing (45–47).

The best characterized function of miRNAs is their binding to the

3′UTR region of their target mRNAs via the seed region (48); however, there are organisms that do

not express Ago proteins (49),

suggesting different modes of action for these RNAs. Indeed, miRNAs

interact with specific promoters (50,51),

regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally at the nuclear

level (52), and act as ligands

for Kir2.1 (40) and for TLRs 7

and 8.

miRNA-mediated activation of TLRs in

cancer

TLRs recognize both PAMPs and DAMPs, where DAMPs are

secreted by cells in response to tissue damage or cell death and

their excessive release is associated with autoimmune diseases and

cancer (48,49). In relation to this, an increase in

the production of DAMPs (also called ‘alarmins’) has been observed

in different types of cancer as (e.g., pancreatic cancer, breast

cancer, lung cancer, among others) a response to cell death and

chronic inflammation (53,54).

The involvement of TLRs in cancer is a complex issue

as it involves several factors such as: i) Expression of specific

TLRs (55,56); ii) expression of TLRs in specific

cell strains (57); iii)

mutagenesis (58); and iv) TLR

adaptor proteins (59), among

others. In spite of the aforementioned issues, certain ligands of

TLRs 2,4,7 have been used for the treatment of various types of

cancer (28,29,60)

and several ligands have antitumor effects (61–63).

The efficiency of TLR ligands as immunotherapeutic agents lies

predominately in the initiation of T-cell immunity: Antigen uptake,

processing and presentation, dendritic cell maturation and T-cell

activation (64).

Activation of TLRs by miRNAs and their relation to

cancer was first demonstrated by Fabbri et al (5), who demonstrated that activation of

TLRs 7/8 by miRs-21 and −29a induced a prometastatic inflammatory

response and promoted tumor growth and metastasis in a

NF-κB-dependent manner. Similar to the observation of Heil et

al (65), Fabbri et al

(5) identified that GU-rich motifs

were required for the activation of TLRs by miRNAs. Notably,

survival of TLR7−/− mice was markedly longer compared

with that of wild-type mice injected with Lewis lung carcinoma

cells. In addition, depletion of tumor exosomes markedly attenuated

the induction of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin

(IL)-6 and early activation antigen CD69. This demonstrated the

impact of activation of TLRs 7/8 by specific miRNAs and suggested

the use of miRNA inhibitors to attenuate the effects in lung

cancer; however, further studies are needed to translate these

experimental results into clinical use for humans.

Studies subsequent to that of Fabbri et al

(5) reported a relationship

between TLRs-miRNAs, but superficially (32–34).

For instance, He et al (32) demonstrated that TLR7 activation, in

a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent manner, by miR-21 induced

myoblasts apoptosis in cancer cachexia. More recently, a feedback

loop was demonstrated between prostaglandin 2 (PGE2) and the

activation of TLRs 7/8 by circulating miR-574-5p (33). These authors suggested that

decreased intracellular expression levels of both miR-574-5p and

PGE2 were associated with the activation-dependent antitumor

effects of TLRs 7 and 8; however, this needs to be validated

experimentally. Finally, miR-16-5p was overexpressed in gastric

cancer and its function as a ligand of TLRs was predicted using

bioinformatics, but its biological impact is unknown. In addition,

it was also postulated that regulatory networks,

lncRNAs-miRNAs-mRNAs, were modified in gastric cancer (34).

Currently, understanding of TLR activation by miRNAs

and their relationship with cancer is limited. Some differentially

expressed miRNAs that function as ligands of TLRs have been

identified in cancer (5,32–34),

which could function as circulating biomarkers for the detection in

various types of cancer. The activation of TLRs by various ligands

is known to have both pro- (66–68)

and anti-tumor effects (69–71)

and this depends on several factors, which should be further

studied in depth in each type of cancer. The identification and

establishment of all the molecular events underlying the activation

of TLRs by miRNAs will likely result in the establishment of

activators and/or inhibitors useful in clinical practice.

miRNAs and TLRs in myocardial

ischemia

Free RNA concentration increases shortly after a

transient myocardial ischemia event and the presence of RNases

attenuates necrotic cell-induced cytokine production in

cardiomyocytes and immune cells and reduces myocardial infarction

after transient ischemia (72,73).

Feng et al (12) reported

that certain circulating miRNAs facilitated the production of

specific cytokines, an effect that was markedly attenuated by: i)

Mutating the uridines of miRs-133a, −146a and −208a by adenosines;

ii) treatment with RNases; iii) eliminating the expression of TLR7

and that of the signal transduction adapter innate immune system

(myeloid differentiation primary response 8, MyD88); or iv) using

TLR7 antagonists. Similarly, the exposure of murine cardiomyocytes

to extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing miR-146a-5p induced the

production of macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), IL-6 and

TNF-α in a TLR7-dependent manner. These effects were observed in

vivo, and cytokine production and activation of the innate

immune response, which was attenuated in mice lacking TLR7

(74).

Although there are still numerous studies that

should be carried out, it is reasonable to consider that the

increased expression of circulating RNA, particularly miRNAs, could

be useful for the diagnosis of a myocardial ischemia event. It

would be potentially beneficial to investigate whether the

expression of other ncRNAs is also increased during these ischemic

events and whether they function as TLR ligands. The search for and

establishment of inhibitors of these miRNAs or TLR7 could be

clinically useful for the treatment of this disease.

Involvement of miRNAs and TLRs in

sepsis

Sepsis is a serious clinical condition that leads to

organ dysfunction in the body caused by an uncontrolled host

response to infection characterized by systemic inflammation, which

is partially mediated by TLRs and certain miRNAs (75,76).

Xu et al (75) demonstrated

that specific circulating miRNAs that are secreted into EVs have a

proinflammatory effect and stimulated the production of IL-6,

TNF-α, interleukin-β and MIP-2. These effects were attenuated by

miR-34a, miR-122 and miR-146a inhibitors, as well as in cells that

did not express TLR7 or MyD88. Notably, injection of EVs from

septic mice into wild-type mice promoted peritoneal neutrophil

migration and this decreased in mice that did not express MyD88.

Similarly, intrathecal administration of exogenous miR-146a

triggered pulmonary inflammation, activated endothelium and

increased endothelial permeability in a TLR7-dependent manner,

indicating the involvement of miR146a-TLR7 in sepsis-associated

acute respiratory distress syndrome (76).

Based on the aforementioned studies, several

therapeutic strategies could be developed for the treatment of this

clinical condition, such as the establishment of miRNA inhibitors,

TLR7 antagonists or MyD88 inhibitors. In particular, some of these

therapeutic strategies may be effective for the treatment of

sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome.

miRNAs and TLRS in neonatal

morbidity

Several lines of evidence indicate that certain

miRNAs (miR-21a, miR-29a, miR-146a-3p and Let-7b) function as

endogenous danger signals by activating TLRs 7/8, which are viral

single strand RNA (ssRNA) sensors. Exposure to bacterial

lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from human fetal membrane (FM) explants

and wild-type mouse FM increased the expression of miR-146a-3p

(77). In women with preterm birth

and chorioamnionitis, increased expression of this miRNA was also

observed and TLR8 activation by miR-146a-3p induced the IL-8 and

IL-1β production in an LPS-dependent manner (77).

Involvement of miRNAs/TLRs 7/8 in

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by severe

acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), producing

symptoms such as fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia and fatigue, among

others (78). In severe cases, it

is characterized by pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome,

sepsis and circulatory shock (79,80).

In order to improve the understanding of the etiology of the

inflammatory processes triggered by SARS-COV-2, Wallach et

al (81) investigated whether

RNA fragments of SARS-COV-2 could activate TLRs. In fact, several

SARS-COV-2 RNA fragments, the majority of which were 22 nt in

length, activated TLRs 7/8 and induced the release of cytokines

from macrophages and microglia to induce the human immune response

against the virus. Regarding this, Liao et al (82) observed that the SARS-CoV-2 spike

protein activated platelets and induced the expression and

secretion of miR-21 and let-7b in EVs to activate TLRs 7 and 8. The

activation of these receptors induced p47phox phosphorylation and

the NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils, resulting in reactive

oxygen species (ROS) production and the formation of hyperactive

neutrophil extracellular traps, which was related to disease

severity. Therefore, increased circulating expression of miRs-21

and -let-7b could be used as predisposing factors and the

TLR7/8-miRNA axis as a therapeutic target for severe COVID-19.

TLR activation by miRNAs in the

brain

Several studies indicate the aberrant release of

miRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's (83–85)

and Parkinson's disease (86–88);

however, the physiological significance of this is currently

unknown. To investigate the possible relationship of miRNAs and the

establishment and/or progression of these diseases, Wallach et

al (6) demonstrated that

miRNAs secreted by cortical neurons induced the secretion of

cytokines and chemokines by microglia and macrophages, which had a

neurotoxic effect mediated by TLRs 7 and 8 (Fig. 1A and B). miRs 100–5p and 298–5p

were internalized within microglia and activated endosomal TLR8 in

a miRNA sequence-dependent manner, but not on its secondary

structure (Fig. 1C). In a similar

manner, these miRNAs also activated neuronal TLR7 and decreased

cell viability in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1D). The presence of these miRNAs in

the cerebrospinal fluid induced neurodegeneration and accumulation

of microglia in the mouse cerebral cortex through TLR7 activation

(Fig. 1E) (89). Similarly, in a murine model of

sepsis, it was observed that the activation of TLR7/MyD88 by

specific miRNAs activated the inflammatory processes in the brain

and induced neuronal apoptosis (90).

In addition, TLR7 and miR-let7b co-localize in

hippocampal CA1 neurons, suggesting the TLR7 activation by this

miRNA. Markedly reduced levels of both TLR7 and miR-let7b increased

hippocampal-dependent memory and attenuated inflammatory cytokine

production (91). These results

demonstrated for the first time that specific miRNAs secretion, in

a particular physiological context, can act on specific TLRs in the

brain. It has been postulated that these miRNAs could be important

in the establishment and/or development of neurodegenerative

diseases, as well as in neurocognitive disorders; however, further

studies are needed to ascertain this. An improved understanding of

the mechanisms underlying the activation of TLRs by miRNAs could

help to establish treatments to ameliorate neurodegenerative

diseases or neurocognitive disorders

Sequence characteristics of miRNAs in

TLR activation

Early work that demonstrated the ssRNA detection by

TLRs was carried out by Heil et al (65). The authors reported that

HIV-derived ssRNA, rich in guanosine (G) and uridine (U), induced

the secretion of interferon-α and proinflammatory and regulatory

cytokines in response to murine TLR7 activation and human TLR8.

Similarly, miRs-21 (GUUG) and −29a (GGUU) have a GU motif in the

nucleotide region 18–21, where base number 20 (U) was very

important for the activation of human TLR8 (1). Meanwhile, Wu et al (92) identified the ‘UGUUAU’ motif and

certain uridines and cytosines of miR-20a-5p as determinants for

TLR7 activation and cytokine secretion. The shortest sequence to

induce TLR7 activation was 10 nt in length (ssRNA), including the

‘UGUUAU’ motif. The activation of TLR7 promoted the secretion of

multiple proinflammatory molecules, which was dependent on PI3K,

MAPK and NF-κB1. The administration of miR-20a-5p in wild-type mice

increased leukocyte migration and this was attenuated in both TLR7

knockout mice and in mice administered with miR-20a-5p but with the

‘UGUUAU’ motif mutated.

TLR activation by miRNAs and other types of ncRNAs

is a focus of ongoing research and existing evidence indicates that

the recognition of miRNAs by TLRs is primarily dictated by GU-rich

motifs, where the sequence and position of nucleotides within the

mature miRNA sequence is a determinant for TLR activation (5).

TLR8 is activated by the binding of ssRNA

degradation products at two different sites (93). At the first binding site, uridine

mononucleoside (Kd, 55 µM) binds to TLR8 by stacking interactions

between TLR8 and the aromatic moiety of ligands and hydrogen bonds

(94). The second site of TLR8 is

recognized by the UG dinucleotide, which increases the affinity of

uridine for TLR8 by 50-fold. TLR8 and TLR7 receptors have

functional and sequence similarities, so some structural features

of TLR8 can be applied to those of TLR7. Regarding this, TLR7 has

an activation mode similar to that of TLR8, in which guanosine and

its derivatives, instead of uridine, bind to TLR7 and this binding

is also modulated by oligonucleotide binding at a second site

(95,96).

Similar to TLRs 7/8, TLR13 is activated by ssRNA 13,

derived from the 23S ribosomal subunit, by binding at a site formed

by the interaction of the N- and C-terminal regions of this

receptor (97). The binding of

ssRNA13 to TLR13 depends on the formation of a stem-loop structure

(G2057 and C2064) and the establishment of hydrogen bonds between

specific nucleotides (A2058, A2060 and G2061) and the TLR13 leucine

rich regions LRR2-LRR25. Notably, the interaction of ssRNA13 with

TLR13 was pH-dependent, with a preference for acid pH.

miRNAs retain the viral consensus motifs for TLR

interaction and activation, but this does not rule out other

sequences and mechanisms involved in TLR activation by ssRNA.

Ligand binding to a first site of TLRs 7 and 8 increases the

affinity of another ligand at a second site, which may occur by

allosteric events. More evidence is needed to know whether

activation of TLRs by miRNAs also occurs in this way.

Interactions of RNYs with TLRs

RNYs are highly conserved sncRNAs in vertebrates

(98) and have also been detected

in prokaryotes (99) and viruses

(100). In humans, four RNYs have

been identified: RNY1, RNY3, RNY4 and RNY5, and ~1,000 pseudogenes

(101). The physiological

importance of YRNAs was partially identified by studying their

interaction with proteins and by bioinformatics approaches

(6). Functions regulated by RNYs

include control of the immune system (102,103), DNA replication (99), development (98), cell proliferation (104), enhanced translation efficiency

and virus assembly and retrotransposition control (105).

Circulating ribonucleoprotein complexes associated

with RNYs predominantly induce immune activation and several of

these effects depend on signaling pathways mediated by TLRs. A

previous study reported that each of the TLRs do not respond in the

same way to the RNY activation and have diverse physiological

effects (Table I) (7). For instance, TLR7 activation by RNY1

induced nephritis, but that of TLR3 by RNY3 did not. It has also

been shown that the activation of a particular TLR by a specific

RNY can induce inflammation in a given tissue and repress it in

another. Regarding this, TLR3 or TLR7 activation by U1 RNA induced

lung disease, but that of TLR7 by RNY1 did not have the same effect

(7). In addition, it has been

shown that RNYs that are not bound to Ro60 or La proteins have a

greater effect on TLR activation, because these proteins recognize

the hairpin structure and the 5′-phosphate group of RNYs, which are

important sites for their interaction with TLRs (35).

| Table I.Activation of specific TLRs by ncRNAs

and their fragments. |

Table I.

Activation of specific TLRs by ncRNAs

and their fragments.

| A, ncRNAs:

miRNAs |

|---|

|

|---|

| First author/s,

year | ncRNA type | Activated TLR | Experimental

model | Biological

function | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Fabbri et

al, 2012 | miR-21 and

miR-29a | 7,8 | Cancer | Induction of

prometastatic inflammatory response: | (5) |

|

|

|

|

| Promotion of tumor

growth and metastasis. |

|

| Feng et al,

2017 | miR-133a, miR-146a

and miR-208a | 7 | Myocardial

ischemia | Production of the

cytokines MIP-2, TNFα and IL-6. Migration of peritoneal neutrophils

and monocytes. | (12) |

| Borchert et

al, 2007 | miR-146a-5p | 7 | Myocardial

ischemia | Production of

MIP-2, IL-6 and TNFα and activation of the innate immune

response. | (46) |

| Chung et al,

2011 | miR-34a, miR-122

and miR-146a | 7 | Sepsis | Proinflammatory and

production of MIP-2, IL-6, IL-β and TNFα: Peritoneal neutrophil

migration. | (47) |

| Wallach et

al, 2020 | miR-340-3p and

miR-132-5p | 7,8 | Neuronal

injury | Release of

cytokines and chemokines from microglia: Neurodegenerative

effect. | (6) |

| Mardente et

al, 2012 | miR-100-5p and

miR-298-5p | 7,8 | Neurodegenerative

disease model | Secretion of

cytokines and chemokines from microglia and macrophages: Increased

phagocytosis. Activation of autonomic apoptosis of cortical

neurons. miRNAs in cerebrospinal fluid: Neuro-degeneration and

accumulation of microglia in mouse cerebral cortex. | (54) |

| Hao et al,

2018 | miR-20a-5p and

miR-148b-3p | 7 | Central nervous

system pathology | Secretion of

proinflammatory molecules dependent on PI3K, MAPKs and NF-κβ.

Migration of leukocytes. | (56) |

|

| B, ncRNAs:

rRNAs |

|

| Oldenburg et

al, 2012; Huang et al, 2023; Chen et al; 2014;

Huang et al, 2022 | 23S rRNA | 13 | Bacterial

infections, action of lactic acid bacteria | Activation by

bacterial infections, regulates the beneficial actions of lactic

acid bacteria. | (8,34,72,76) |

| Shimada et

al, 2020 | 23S (Sa19) and 16S

mt-rRNA | 8 | Bacterial

infections | Activation of PBMCs

in a MyD88-dependent manner. | (74) |

| Chen et al,

2014 | 18S rRNA | 2 | Inflammation | Activation of

differentiated human monocytoid THP-1 cells. | (72) |

| Alvarez-Carbonell

et al, 2017 | Bacterial rRNA | 3 | HIV-associated

neurocognitive disorders | Synergic activation

of TLR2 stimulated transcriptional expression of inflammatory genes

and TNF-α release from macrophages. | (9) |

|

| C, ncRNAs:

RNYs |

|

| Greidinger et

al, | RNY3 | 3,7,8 | Autoimmunity | RNY3 was a strong

activator | (7) |

| 2007 | RNY1 | 7, 8 |

| strong activator of

TLRs 3,7, |

|

|

| RNY4 | 7 |

| and 8. |

|

|

| RNY5 | 7 |

| TLR3 activation by

RNY3 did |

|

|

|

|

|

| not induce

nephritis. |

|

|

|

|

|

| RNY4 was a strong

activator of TLR7. |

|

|

|

|

|

| TLR7 activation by

RNY5 induced nephritis. |

|

| Rodriguez-Corona

et al, 2023 | RNYs 1,3-5 | 5,7,8,10 | Pediatric

astrocytoma | The interaction of

RNYs 1,3-5 with TLRs 5,7,8,10 was predicted. | (10) |

|

|

|

|

| Alzheimer

disease-amyloid secretase, B cell activation, ubiquitin proteasome,

angiogenesis, apoptosis, endothelin and dopamine receptor

mediated-signaling pathways. |

|

|

| D, ncRNA

fragments: tRNAs |

|

| Deng et al,

2024 | 5′-tRNAHisGUG | 7 | Bacterial

infections | TLR7

activation | (91) |

| Wu et al,

2021 | 5′-tRNAVal

CAC/AAC | 7 | Bacterial

infections | Elimination of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a GUUU sequence-dependent

manner. | (92) |

|

| E, ncRNA

fragments: s-RNYs |

|

| Onafuwa- | RNY1-5p, | 7 |

Atherosclerosis | Induction of

apoptosis and | (100) |

| Nuga et al,

2005 | RNY3-5p and

RNY4-5p |

|

| NF-κB-mediated

inflammation |

|

| Rodriguez-Corona

et al, 2023 | s-RNYs loop

domains | 3,7,10 | Pediatric

astrocytoma | Bioinformatic

prediction. | (10) |

Based on the aforementioned studies, the TLR-RNY

interactions seem to depend on the type of TLR and RNY involved as

well as on the cellular tissue. In certain cases, this activation

was related to inflammatory processes, but the opposite effect was

observed in others. It is necessary to identify which other

molecular components and signaling pathways are determining these

biological differences.

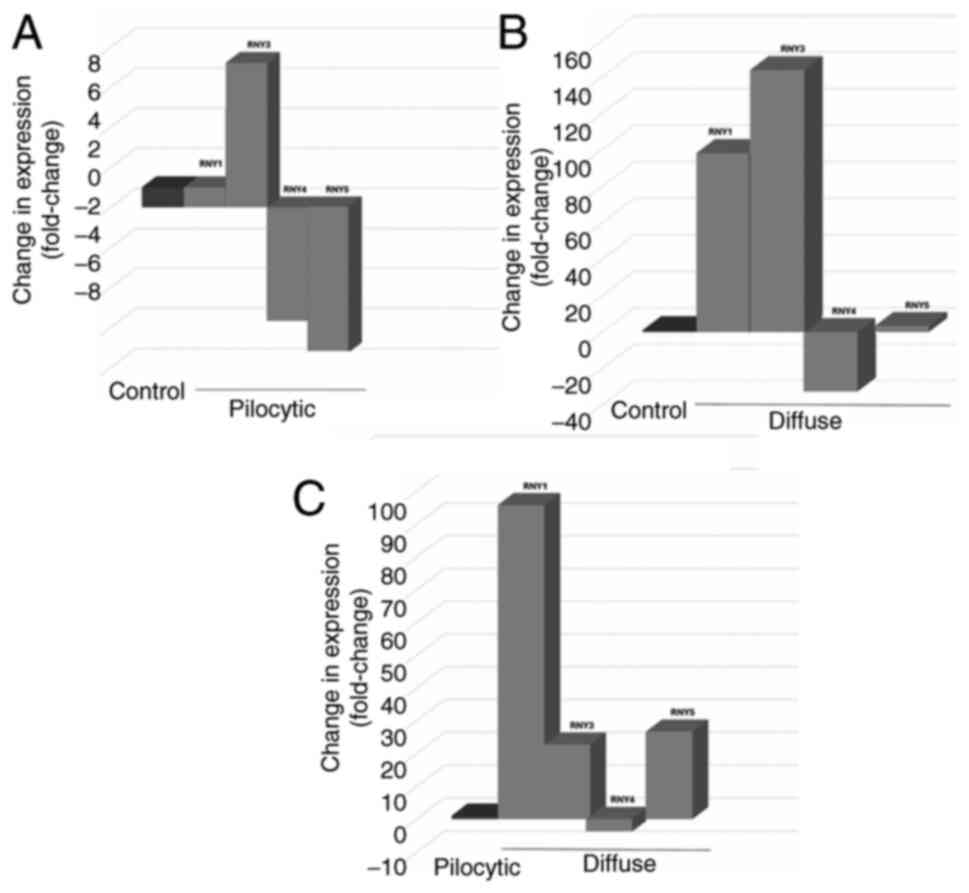

In pediatric patients with astrocytoma,

Rodríguez-Corona et al (10) demonstrated differential circulating

expression of RNYs (Fig. 2A-C) and

the interaction of RNYs with cellular receptors was predicted.

Bioinformatics analysis [HIPPIE database

(cbdm-01.zdv.uni-mainz.de/~mschaefer/hippie/), by using the

following commands: NETWORK QUERY; direct interaction; GO

(biological process); show KEGG effect; and PANTHER database

(pantherdb.org), by using the following commands: ID List; Homo

sapiens; Functional classification viewed in gene list;

Pathway)] indicated the RNY interaction with receptors other than

TLRs to regulate a myriad of cellular pathways, such as apoptosis,

angiogenesis, cholecystokinin receptor and p53 signaling pathways,

as well as Parkinson's disease (Fig.

3). Identifying the target organs of RNYs and understanding the

biological processes that are being modified by acting on TLRs or

on other types of receptors may be important to understand.

rRNA interactions with TLRs

rRNA is the most abundant RNA species in organisms

and, similar to miRNAs and RNYs, rRNAs also interact with TLRs.

TLR13 is known to recognize a specific sequence of the bacterial

ribosomal 23S subunit, which induces the production of

infection-fighting cytokines (8,36,97,106); however, the 23S ribosomal subunit

derived from erythromycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

(S. aureus) strains or methylated oligoribonucleotides,

which mimics MLS antibiotic resistance, did not stimulate TRL13

(36). This observation

demonstrates a mechanism of antibiotic resistance and parallels

host cell ‘detection’ systems, whereby exposure of bacteria to

antibiotics establishes epigenetic marks that render them less or

totally inert to antibiotics and also evade detection by TLR13.

Similarly, fish TLR13a and b receptors were activated by bacterial

23S rRNA and induced the immune response by stimulating specific

effector proteins (Table II)

(106).

| Table II.Differential activation of

intracellular pathways mediated by TLR13a and b. |

Table II.

Differential activation of

intracellular pathways mediated by TLR13a and b.

| Co-expression in

293T cells | Signaling pathway

activated |

|---|

| TLR13a/MyD88 | Increased

NF-κB-mediated pathway activation. |

|

| Low effect on AP1

pathway activation. |

|

| Significant

activation of the IFN-β-mediated pathway |

| TLR13b | Activation of the

AP1-mediated pathway. |

Li and Chen (36)

demonstrated that the Sa19 sequence (ACGGAAAGACCCC) of the 23S

subunit is a ligand of murine TLR13, which acts mainly against

infection by Gram-positive bacteria. The Sa19 sequence and

mitochondrial 16S rRNA (mt-rRNA) stimulate peripheral blood

mononuclear cells in a MyD88-dependent manner. Sa19 and S.

aureus and Escherichia coli (E. coli) derived

sequences and mitochondrial (mt)-RNA also activate human monocytoid

THP1 cells via TLR8. In addition to the 23S and 16S subunits,

Krüger et al (37) reported

that the 5S subunit from S. aureus and E. coli, as

well as mt-rRNA and P-/DAMPs stimulators, activate human TLR8. In

addition to the UGG motif, the UAA and UGA motifs are required for

TLR8 activation.

In addition to the 23S and 16S ribosomal subunits,

the 18S ribosomal subunit is involved in TLR activation. The

interaction of the 18S rRNA subunit with Pam2 (Pam2 CSK4), ligand

of TLRs 2 and 6, increased the affinity of Pam2 for TLR2 to act

synergistically. TLR2 activation stimulated the transcriptional

expression of inflammatory genes and TNF-α release from

macrophages, which was NF-κB-dependent (107). Usually, the acute cellular

responses to numerous signals are additive and, in certain cases,

the response to simultaneous stimuli is notably greater than the

sum of the responses to each stimulus separately; this is known as

synergism. This has biological significance since the cell will

only respond when two or more signals are present simultaneously.

Therefore, it will be necessary to identify whether all TLRs act

synergistically, and which ligand combinations and which mechanisms

govern the regulation of specific cellular processes.

Although TLRs are a primary detection system that

fight diverse infections, there is also evidence of their

participation in the beneficial action exerted by lactic acid

bacteria in organisms (e.g. anti-inflammatory effects and

activation of the intestinal immune system) (108–110). In mice, these bacteria have

immunomodulatory effects that are mediated, at least in part, by

IL-12 and TLR13. Since humans do not express this receptor, it

could be considered that the effects of this type of bacteria are

mediated by another TLR. Nishibayashi et al (111) demonstrated that the 23S and 16S

rRNA subunits of Enterococcus faecalis Ec-12 strain

activated TLR8 and induced IL-12 production.

Organisms have ‘engineered’ molecular elements that

allow them to fight infectious agents. The bacterial rRNA binding

site to the TLR is also involved in antibiotic resistance, which

ensures evasion of these two defense systems (36). Conversely, the infected cell

detects the infectious agent by means of TLRs and, additionally, it

secretes mtRNA to ensure the innate immune system response to the

infection (37). In short, each

organism fights for its survival by generating innumerable ‘attack’

or ‘defense’ mechanisms to ensure its survival.

i) rRNAs and TLRs in the brain. Alvarez-Carbonell

et al (9) demonstrated the

reactivation of HIV in microglia cultures, an effect that was

mediated by TLR3 activation by poly (I:C) and bacterial rRNA. The

activation of other TLRs revealed a minor effect on the

reactivation of this virus, and the activation of TLRs 2/1, 4–6

induced the NF-κB-mediated pathway, but the activation of TLR3

induced IRF3. Diverse effects were observed in human monocytes and

rat microglia. These results demonstrate that the activation of

TLRs may have functions other than the immune system control. As

aforementioned, both, the biological effect and the potency of this

effect, depends on the type of TLR activated and by the ligand and

the coactivators that may or may not be present in a given

tissue.

lncRNAs control TLR activity

lncRNAs are RNAs with a size of 200–1,000 kb, which

exert a variety of cellular functions by diverse mechanisms

(112,113). It is established that the

activation of TLRs 7 and 9 is associated with immune dysfunction

and severe disease states, and that blockade of these receptors

improved the health status of mice susceptible to develop lupus

(7–9,20).

Similarly, Yang et al (38)

demonstrated that lnc-Atg1611 binds to TLR7 and activates the

MyD88-mediated signaling pathway in immune cells and deletion of

this lncRNA attenuated TLR7-related autoimmune phenotypes in murine

models. The binding of lnc-Atg1611 to TLR7 is complex, as on one

side it binds to TLR7 and on the other to MyD88, thus functioning

as a ‘scaffold’, which induces structural changes in the TLR7

stem-loop and induces signal transduction (113). The authors suggested that

self-RNAs, particularly lnc-Atg1611, may be potential therapeutic

targets to control the development of autoimmune disorders. In this

regard, Mussari et al (20)

identified an antagonist (7f) that has a high affinity for TLR7

and, to a lesser extent, for TLR9, which blocks cytokine production

mediated by TLRs 7 and 9 and markedly decreased proteinuria,

antibody production and IL-10 secretion.

i) lncRNAs and TLRs in cancer. Anaplastic thyroid

carcinoma (ATC) is a rare and aggressive type of thyroid cancer

that spreads rapidly to other parts of the body. In thyroid cancer,

the lncRNA C5AR1 shows increased expression and correlates

positively with short patient survival (39). Molecularly, C5AR1 activates TLRs 1

and 2 receptors and MyD88, which results in tumor growth and lung

metastasis of ATC cells in a murine model and inhibition of the

expression of this lncRNA, considerably decreased the oncogenic

effects regulated by its interaction with TLRs (39). Regarding this, miR-355-5p

negatively regulated C5AR1 expression, which could be used as a

therapeutic tool to downregulate the levels of this lncRNA and

attenuate the oncogenic effects produced by C5AR1-TLRs 1/2-MyD88

signaling.

These results demonstrate that several ncRNAs can

function as ligands for TLRs and exert oncogenic effects. The

identification of all ncRNAs and molecular elements regulating the

TLR-mediated signaling at a specific point in time will allow for

the understanding of the interaction mechanisms underlying TLR

activation and/or inhibition to develop immunotherapies. lncRNAs

have been identified as positive or negative regulators of TLRs,

affecting immune response and drug sensitivity; however, further

studies are needed to understand the mechanisms by which these

ncRNAs control TLR pathways.

Interaction of ncRNA-derived fragments with

TLRs

Since 1971, the production of fragments (~50 nt)

originating from the 16S ribosomal subunit has been observed

(114). Similarly, Borek et

al (115) reported a higher

rate of turnover and excretion of transfer RNA (tRNA) ‘degradation

products’ in patients with cancer relative to individuals without

cancer. Subsequent studies continued to report the presence of

these ‘degradation products’ (116–120). It was not until 2008 that

Thompson et al (121)

reported that these RNA fragments have specific biological

functions in addition to controlling the levels of full-length

sequence transfer RNA (tRNAs). To date, it is acknowledged that all

known ncRNAs are fragmented and that this appears to occur by

specific biogenic pathways; however, the molecular elements

involved in these machineries are not yet known.

Fragments derived from tRNAs

Several types of fragments generated from tRNAs have

been identified and they are classified into two categories: tRNA

halves (tiRNAs; 31–40 nt) and tRNA-derived fragments (14–30 nt)

based on the nuclease cleavage sites in mature or premature tRNAs

(116,117).

Several physiological functions have now been

described for transfer RNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) (122,123), including TLR7 activation. Pawar

et al (118) demonstrated

that mycobacterium infection activates TLRs expressed on the

surface of human monocyte-derived macrophages, which promoted the

production and secretion of 5′-tRNA halves in EVs. Specifically,

the 5′-tRNAHisGUG half was recognized and endocytosed by

recipient cells to subsequently activate endosomal TLR7. Later, the

authors demonstrated TLR7 activation by the

5′-tRNAValCAC/AAC where its GUUU terminal sequence was

determinant for the activation of this receptor and for the

elimination of bacterial infection. The mutation of this tRNA-half

showed that the GUUU sequence was determinant for TLR7 activation.

Notably, this motif is present in other RNAs that also stimulate

this receptor (124).

To date, tsRNAs are the best characterized fragments

and are known to be involved in rRNA maturation, reverse

transcription, adaptation of parasites to their environment and as

ligands for TLRs. The tsRNA-TLR interaction is key for eliminating

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and certainly for other

types of bacteria and viruses, so understanding the mechanisms

underlying the tsRNA-TLR regulatory axis may be important for

generating drugs to mitigate these types of infections, which is

particularly important due to the growing resistance to antibiotics

(125,126).

Fragments derived from RNYs and

lncRNAs

RNY fragments (s-RNYs) are generated from stem

terminal regions during apoptosis (119) from miRNAs or Piwi-interacting

RNAs (127) or by RNase L

activity or by activation of the innate immune system mediated by

Poly: I:C (120). Specific

biogenic pathways have been proposed for the generation of s-RNYs,

which retain specific sequences from their parental RNYs to

regulate particular cellular processes (Table I). Currently, limited information

exists regarding TLR activation by s-RNYs. To the best of our

knowledge, there is only one study which revealed that the release

of s-RNYs (sRNYs1-5p, 3–5p and 4–5p)/Ro60 by macrophages resulted

in the activation of TLR7 and in the induction of

caspase-3-dependent apoptosis and NF-κB-mediated inflammation. The

full form of RNYs/Ro60 did not have the same effect, indicating

specific functions in this cellular context for the s-RNYs

(128). Related to this,

Rodriguez-Corona et al (10) predicted the RNYs and their

fragments interactions with TLRs and with other receptors (Table I).

RNYs and their fragments have a central role in

immune system responses and at least part of these responses depend

on RNYs/s-RNYs-TLRs interactions. Studies indicate that the action

of s-RNYs is not necessarily the same as that of parental RNYs

(10,128); therefore, it is necessary to

identify the molecular traits that are determining these

differences.

In relation to lncRNAs, Giraldez et al

(129) demonstrated the presence

of fragments of mRNAs and lncRNAs in blood plasma that are missed

by standard sequencing techniques. The detection of these fragments

in plasma has potential for use as biomarkers and their functions

need to be gradually elucidated.

Conclusion

The discovery of ncRNAs, considerably changed the

understanding and approach to the study of life sciences. Initial

studies demonstrated the interfering function that miRNAs (22,23)

and small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (97) have; subsequent studies have shown

the diversity of functions and mechanisms of action by which ncRNAs

may act.

Up to now, several studies have demonstrated that

TLR activity is mediated by ncRNAs and their fragments (5,7,8,32,36,38);

however, several questions arise regarding the molecular mechanisms

underlying this activation and the physiological effect this may

have. The majority of data indicate that activation of TLRs by

ncRNAs or their fragments primarily induces the innate immune

system, protecting organisms from microbial and viral infections

(11–15); however, this activation is also

associated with oncogenic (5,39),

neurodegenerative effects (6,90)

and viral reactivation (9).

Although in the majority of cases the end result is the activation

of the immune system, each ncRNA and its fragments activate

specific intracellular signaling pathways, resulting in the control

of specific biological effects (113,118,128). Uncovering the molecular

mechanisms involved in these differences will allow for improved

understanding of the ncRNAs/fragment-TLR relationship and the

biological functions that are mediated by these interactions.

Regarding this, Wallach et al (6) reported that secondary structure

formation did not determine the binding of miRNAs to TLRs; however,

miRs-21, −93 and 296 can adopt hairpin and/or homoduplex

structures, depending on the miRNA concentration and ionic

conditions, which determined their specificity for target mRNAs

(130,131). Similarly, there is evidence

indicating that secondary structures of mature siRNAs influenced

the efficiency of siRNA-mRNA interaction, where unstructured siRNAs

exert a greater silencing effect than those with secondary

structures. Belter et al (131) observed that miRNA hairpins

resemble those of the anti-Tn-C aptamer, indicating that miRNAs can

directly regulate their targets in an RISC-independent manner,

making them highly specific regulators, more so than previously

considered.

TLRs regulate both the innate and adaptive immune

system and are mainly associated with autoimmune disorders, chronic

inflammation, chronic viral infections and cancer, making these

receptors a target for the development of immunotherapeutic

strategies. Currently, there are several TLR ligands used as

vaccine adjuvants to increase the efficacy of vaccines, and TLR

agonists and antagonists have been identified for the treatment of

chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), HIV

(23,132), autoimmune diseases (20,21,133) or for the treatment of cancer

(25–27). For instance, TLR7 agonists have

been tested in clinical trials for HBV infection and a TLR9 ligand

as an adjuvant in a vaccine against HBV (132). The activation of specific TLRs

inhibited HIV replication and reduced viral spread; however, TLR

activation also led to the reactivation of latent HIV in cell

cultures. This may be important for the development of anti-HIV

therapies, since reactivation of latently infected reservoir cells

could facilitate the recognition by cytotoxic immune cells, which

has already been observed in clinical studies. Therefore,

immunotherapy against chronic HBV or HIV infection is promising and

antiviral drugs have been approved for the clinical treatment of

HBV and HIV (134).

In previous years, several groups have focused on

designing oligonucleotides that antagonize TLRs 7–9 and have been

proposed as potential treatments for autoimmune and inflammatory

diseases (20–22). Of these antagonists, IMO-8400

reduced moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in patients

participating in a phase IIa clinical trial (21). Other research groups have focused

on developing small molecules that function as antagonists of TLRs

7–9. For example, the 7f antagonist of TLRs 7 and 9 has a strong

potency and high selectivity for these receptors, emphasizing the

use of small molecules for the treatment of autoimmune diseases

(20). Meanwhile, TAC5, an

antagonist of endosomal TLRs, reduced inflammation and prevented

the progression of psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus in

mice, indicating its therapeutic potential for their treatment

(22). Despite this, there is a

need to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity as well as the

side effects that the application of these molecules may have. For

example, a study conducted by Christensen et al (133) reported that TLR9 knockout mice

developed more aggressive disease pathology; however, dual TLR 7

and 9 knockout demonstrated protection.

For cancer treatment, several TLR3 agonists were

observed to induce cancer regression by restoring immunogenicity to

chemotherapy (25,26). Similarly, intratumoral injection of

the TLR7 and 8 receptor agonist MEDI9197 suppressed tumor growth

and increased survival in murine models by regulating the immune

response and by increasing the expression of associated genes in

innate and adaptive immunity (27,135,136). Notably, the antitumor effects of

MEDI9197 were most potent when this drug was applied in combination

with a programmed death ligand 1 inhibitor (135). Although no tumor response was

observed, the application of MEDI9197 or in combination with

durvalumab and/or palliative radiation induced local and systemic

immune activation in patients with solid tumors (136). In addition, sugar-conjugated TLR7

ligands increased autoimmunostimulatory activity, demonstrating

potential for application as adjuvants in vaccines and cancer

therapies (137).

The activation of TLRs to induce innate and

adaptive immunity and to treat various diseases has great clinical

potential, as there is considerable experimental evidence

indicating their application for the treatment of viral and immune

diseases and different types of cancer. Nevertheless, the

translation of experimental observations into effective clinical

application is a major challenge and further work is still needed

to increase the therapeutic effect and increase the precision of

treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Verónica Vratny for

proofreading and editing.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

RREG and MAVF contributed to the study conception

and design and conducted the literature review and wrote the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient content for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Costa S, La Rocca G and Cavalieri V:

Epigenetic regulation of chromatin functions by MicroRNAs and Long

Noncoding RNAs and implications in human diseases. Biomedicines.

13:7252025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Godden AM, Silva WTAF, Kiehl B, Jolly C,

Folkes L, Alavioon G and Immler S: Environmentally induced

variation in sperm sRNAs is linked to gene expression and

transposable elements in zebrafish offspring. Heredity (Edinb). Mar

22–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Oliveira-Rizzo C, Colantuono CL,

Fernández-Alvarez AJ, Boccaccio GL, Garat B, Sotelo-Silveira JR,

Khan S, Ignatchenko V, Lee YS, Kislinger T, et al: Multi-omics

study reveals Nc886/vtRNA2-1 as a positive regulator of prostate

cancer cell immunity. J Proteome Res. 24:433–448. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Estravís M, García-Sánchez A, Martin MJ,

Pérez-Pazos J, Isidoro-García M, Dávila I and Sanz C: RNY3

modulates cell proliferation and IL13 mRNA levels in a T lymphocyte

model: A possible new epigenetic mechanism of IL-13 regulation. J

Physiol Biochem. 79:59–69. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Fabbri M, Paone A, Calore F, Galli R,

Gaudio E, Santhanam R, Lovat F, Fadda P, Mao C, Nuovo GJ, et al:

MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic

inflam-matory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:E2110–E2116.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wallach T, Wetzel M, Dembny P, Staszewski

O, Krüger C, Buonfiglioli A, Prinz M and Lehnardt S: Identification

of CNS Injury-Related microRNAs as Novel Toll-Like Receptor 7/8

Signaling Activators by Small RNA Sequencing. Cells. 9:1862020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Greidinger EL, Zang YJ, Martinez L, Jaimes

K, Nassiri M, Bejarano P, Barber GN and Hoffman RW: Differential

tissue targeting of autoimmunity manifestations by

autoantigen-associated Y RNAs. Arthritis Rheum. 56:1589–1597. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Oldenburg M, Krüger A, Ferstl R, Kaufmann

A, Nees G, Sigmund A, Bathke B, Lauterbach H, Suter M, Dreher S, et

al: TLR13 recognizes bacterial 23S rRNA devoid of erythromycin

resistance-forming modification. Science. 337:1111–1115. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Alvarez-Carbonell D, Garcia-Mesa Y, Milne

S, Das B, Dobrowolski C, Rojas R and Karn J: Toll-like receptor 3

activation selectively reverses HIV latency in microglial cells.

Retrovirology. 14:92017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rodríguez-Corona JM, Ruiz Esparza-Garrido

R, Horta-Vega JV and Velázquez-Flores M: Circulating Y-RNAs: A

predicted function mainly in controlling the innate immune system,

cell signaling and DNA replication in pediatric patients with

pilocytic and diffuse astrocytoma. Clin Pediatr. 8:1–9. 2023.

|

|

11

|

Akira S, Takeda K and Kaisho T: Toll-like

receptors: Critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity.

Nature Immunology. 2:675–680. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Feng Y, Zou L, Yan D, Chen H, Xu G, Jian

W, Ping Cui and Chao W: Extracellular MicroRNAs induce potent

innate immune responses via TLR7/MyD88-dependent mechanisms. J

Immunol. 199:2106–2117. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wiese MD, Manning-Bennett AT and Abuhelwa

AY: Investigational IRAK-4 Inhibitors for the treatment of

rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin invest Drugs. 29:475–482. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Xiao L, Liu Y and Wang N: New paradigms in

inflammatory signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol

Heart Circ Physiol. 306:H317–H325. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Van Tassell BW, Seropian IM, Toldo S,

Salloum FN, Smithson L, Varma A, Hoke NN, Gelwix C, Chau V and

Abbate A: Pharmacologic inhibition of myeloid differentiation

factor 88 (MyD88) prevents left ventricular dilation and

hypertrophy after experimental acute myocardial infarction in the

mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 55:385–390. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J,

Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S and Medzhitov R: Recognition of

commensal microflora by Toll-like receptors is required for

intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 118:229–241. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tsan MF and Gao B: Endogenous ligands of

Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 76:514–519. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Rock FL, Hardiman G, Timans JC, Kastelein

RA and Bazan JF: A family of human receptors structurally related

to Drosophila Toll. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:588–593. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Takeda K and Akira S: Toll-like receptors

in innate immunity. Int Immunol. 17:1–14. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mussari CP, Dodd DS, Sreekantha RK,

Pasunoori L, Wan H, Posy SL, Critton D, Ruepp S, Subramanian M,

Watson A, et al: Discovery of potent and orally bioavailable small

molecule antagonists of toll-like receptors 7/8/9 (TLR7/8/9). ACS

Med Chem Lett. 11:1751–1758. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Balak DM, van Doorn MB, Arbeit RD,

Rijneveld R, Klaassen E, Sullivan T, Brevard J, Thio HB, Prens EP,

Burggraaf J and Rissmann R: IMO-8400, a toll-like receptor 7, 8,

and 9 antagonist, demonstrates clinical activity in a phase 2a,

randomized, placebo-controlled trial in patients with

moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Clin Immunol. 174:63–72. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Patra MC, Achek A, Kim GY, Panneerselvam

S, Shin HJ, Baek WY, Lee WH, Sung J, Jeong U, Cho EY, et al: A

novel small-molecule inhibitor of endosomal TLRs reduces

inflammation and alleviates autoimmune disease symptoms in Murine

models. Cells. 9:16482020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Winckelmann AA, Munk-Petersen LV,

Rasmussen TA, Melchjorsen J, Hjelholt TJ, Montefiori D, Østergaard

L, Søgaard OS and Tolstrup M: Administration of a Toll-like

receptor 9 agonist decreases the pro viral reservoir in

virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients. PLoS One.

8:e620742013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Christensen S, Shupe J, Nickerson K,

Kashgarian M, Flavell R and Shlomchik M: Toll-like receptor 7 and

TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing

inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus.

Immunity. 25:417–428. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Komal A, Noreen M and El-Kott AF: TLR3

agonists: RGC100, ARNAX, and poly-IC: A comparative review. Immunol

Res. 69:312–322. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

LeNaour J, Thierry S, Scuderi SA,

Boucard-Jourdin M, Liu P, Bonnin M, Pan Y, Perret C, Zhao L, Mao M,

et al: A chemically defined TLR3 agonist with anticancer activity.

Oncoimmunology. 12:22275102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Singh M, Khong H, Dai Z, Huang XF, Wargo

JA, Cooper ZA, Vasilakos JP, Hwu P and Overwijk WW: Effective

innate and adaptive anti-melanoma immunity through localized

TLR-7/8 activation. J Immunol. 193:4722–4731. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Fuge O, Vasdev N, Allchorne P and Green

JS: Immunotherapy for bladder cancer. Res Rep Urol. 7:65–79.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Morales A, Eidinger D and Bruce AW:

Intracavitary Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of

superficial bladder tumors. J Urol. 116:180–183. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bayraktar R, Bertilaccio MTS and Calin GA:

The interaction between two worlds: MicroRNAs and Toll-like

receptors. Front Immunol. 14:10532019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yu J, Zhang X, Cai C, Zhou T and Chen Q:

Small RNA and Toll-like receptor interactions: Origins and disease

mechanisms. Trends Biochem Sci. Feb 15–2025.doi:

10.1016/j.tibs.2025.01.004 (Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

He WA, Calore F, Londhe P, Canella A,

Guttridge DC and Croce CM: Microvesicles containing miRNAs promote

muscle cell death in cancer cachexia via TLR7. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 111:4525–4529. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Donzelli J, Proestler E, Riedel A,

Nevermann S, Hertel B, Guenther A, Gattenlöhner S, Savai R, Larsson

K and Saul MJ: Small extracellular vesicle-derived miR-574-5p

regulates PGE2-biosynthesis via TLR7/8 in lung cancer. J Extracell

Vesicles. 10:e121432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Huang X, Ma Z and Qin W: Screening and

bioinformatics analyses of key miRNAs associated with Toll-like

receptor activation in gastric cancer cells. Medicina (Kaunas).

59:5112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Clancy RM, Alvarez D, Komissarova E,

Barrat FJ, Swartz J and Buyon JP: Ro60-associated single-stranded

RNA links inflammation with fetal cardiac fibrosis via ligation of

TLRs: A novel pathway to autoimmune-associated heart block. J

Immunol. 184:2148–2155. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Li XD and Chen ZJ: Sequence specific

detection of bacterial 23S ribosomal RNA by TLR13. Elife.

1:e001022012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Krüger A, Oldenburg M, Chebrolu C, Beisser

D, Kolter J, Sigmund AM, Steinmann J, Schäfer S, Hochrein H,

Rahmann S, et al: Human TLR8 senses UR/URR motifs in bacterial and

mitochondrial RNA. EMBO Rep. 16:1656–1663. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yang Z, Ji S, Liu L, Liu S, Wang B, Ma Y

and Cao X: Promotion of TLR7-MyD88-dependent inflammation and

autoimmunity in mice through stem-loop changes in Lnc-Atg16l1. Nat

Commun. 15:102242024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Liu B, Sun Y, Geng T, Wang H, Wu Z, Xu L,

Zhang M, Niu X, Zhao C, Shang J and Shang F: C5AR1-induced TLR1/2

pathway activation drives proliferation and metastasis in

anaplastic thyroid cancer. Mol Carcinog. 63:1938–1952. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yang D, Wan X, Dennis AT, Bektik E, Wang

Z, Costa MGS, Fagnen C, Vénien-Bryan C, Xu X, Gratz DH, et al:

MicroRNA biophysically modulates cardiac action potential by direct

binding to ion channel. Circulation. 143:1597–1613. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lee RC, Feinbaum RL and Ambros V: The

C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with

antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 75:843–854. 1993.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wightman B, Ha I and Ruvkun G:

Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by

lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans.

Cell. 75:855–862. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Llave C, Kasschau KD, Rector MA and

Carrington JC: Endogenous and silencing-associated small RNAs in

plants. Plant Cell. 14:1605–1619. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Hansen TB, Venø MT, Jensen TI, Schaefer A,

Damgaard CK and Kjems J: Argonaute-associated short introns are a

novel class of gene regulators. Nat Commun. 7:115382016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Smalheiser NR and Torvik VI: Mammalian

microRNAs derived from genomic repeats. Trends Genet. 21:318–322.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Borchert GM, Lanier W and Davidson BL: RNA

polymerase III transcribes human microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol.

13:1097–1101. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Chung W, Agius P, Westholm JO, Chen M,

Okamura K, Robine N, Leslie CS and Lai EC: Computational and

experimental identification of mirtrons in Drosophila melanogaster

and Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 21:286–300. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Lai EC: MicroRNAs are complementary to

3′UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional

regulation. Nat Genet. 30:363–364. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Drinnenberg IA, Weinberg DE, Xie KT, Mower

JP, Wolfe KH, Fink GR and Bartel DP: RNAi in budding yeast.

Science. 326:544–550. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zardo G, Ciolfi A, Vian L, Starnes LM,

Billi M, Racanicchi S, Maresca C, Fazi F, Travaglini L, Noguera N,

et al: Polycombs and microRNA-223 regulate human granulopoiesis by

transcriptional control of target gene expression. Blood.

119:4034–4046. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Di Mauro V, Crasto S, Colombo FS, Di

Pasquale E and Catalucci D: Wnt signalling mediates miR-133a

nuclear re-localization for the transcriptional control of Dnmt3b

in cardiac cells. Sci Rep. 9:1–15. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Leucci E, Patella F, Waage J, Holmstrøm K,

Lindow M, Porse B, Kauppinen S and Lund AH: MicroRNA-9 targets the

long non-coding RNA MALAT1 for degradation in the nucleus. Sci Rep.

3:25352013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

van Beijnum JR, Buurman WA and Griffioen

AW: Convergence and amplification of toll-like receptor (TLR) and

receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) signaling

pathways via high mobility group B1 (HMGB1). Angiogenesis.

11:91–99. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Mardente S, Mari E, Consorti F, Gioia CD,

Negri R, Etna M, Zicari A and Antonaci A: HMGB1 induces the

overexpression of miR-222 and miR-221 and increases growth and

motility in papillary thyroid cancer cells. Oncol Rep.

28:2285–2289. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ronkainen H, Hirvikoski P, Kauppila S,

Vuopala KS, Paavonen TK, Selander KS and Vaarala MH: Absent

Toll-like receptor-9 expression predicts poor prognosis in renal

cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 30:842011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Hao B, Chen Z, Bi B, Yu M, Yao S, Feng Y,

Yu Y, Pan L, Di D, Luo G and Zhang X: Role of TLR4 as a prognostic

factor for survival in various cancers: A meta-analysis.

Oncotarget. 9:13088–13099. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Kabelitz D: Expression and function of

toll-like receptors in T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 19:39–45.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Elliott DRF, Perner J, Li X, Symmons MF,

Verstak B, Eldridge M, Bower L, O'Donovan M and Gay NJ; OCCAMS

Consortium; Fitzgerald RC, : Impact of mutations in Toll-like

receptor pathway genes on esophageal carcinogenesis. PLoS Genet.

13:e10068082017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, Jhavar S,

Xiao W, Lim KH, Kohlhammer H, Xu W, Yang Y, Zhao H, et al:

Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature.

470:115–119. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Li R, Hao Y, Pan W, Wang W and Min Y:

Monophosphoryl lipid A-assembled nanovaccines enhance tumor

immunotherapy. Acta Biomater. 171:482–944. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Zhao BG, Vasilakos JP, Tross D, Smirnov D

and Klinman DM: Combination therapy targeting toll like receptors

7, 8 and 9 eliminates large established tumors. J Immunother

Cancer. 2:122014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Sato-Kaneko F, Yao S, Ahmadi A, Zhang SS,

Hosoya T, Kaneda MM, Varner JA, Pu M, Messer KS, Guiducci C, et al:

Combination immunotherapy with TLR agonists and checkpoint

inhibitors suppresses head and neck cancer. JCI Insight.

2:933972017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Takeda Y, Kataoka K, Yamagishi J, Ogawa S,

Seya T and Matsumoto M: A TLR3-specific adjuvant relieves innate

resistance to PD-L1 blockade without cytokine toxicity in tumor

vaccine immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 19:1874–1887. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Adams S: Toll-like receptor agonists in

cancer therapy. Immunotherapy. 1:949–964. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampeberger F,

Kirchning C, Akira S, Lipford G, Wagner H and Bauer S:

Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like

receptor 7 and 8. Science. 303:1526–1529. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Yoshida T, Miura T, Matsumiya T, Yoshida

H, Morohashi H, Sakamoto Y, Kurose A, Imaizumi T and Hakamada K:

Toll-like receptor 3 as a recurrence risk factor and a potential

molecular therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Clin Exp

Gastroenterol. 13:427–438. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Bianchi F, Milione M, Casalini P, Centonze

G, Le Noci VM, Storti C, Alexiadis S, Truini M, Sozzi G, Patorino

U, et al: Toll-like receptor 3 as a new marker to detect high risk

early stage Non-small-cell Lung Cancer patients. Sci Rep.

9:142882019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Yuan MM, Xu YY, Chen L, Li XY, Qin J and

Shen Y: TLR3 expression correlates with apoptosis, proliferation

and angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma and predicts

prognosis. BMC Cancer. 15:2452015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Ceccarelli S, Marzolesi VP, Vannucci J,

Bellezza G, Floridi C, Nocentini G, Cari L, Traina G, Petri D, Puma

F and Conte C: Toll-like receptor 4 and 8 are overexpressed in lung

biopsies of human Non-small cell lung carcinoma. Lung. 203:382025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Gonzalez-Reyes S, Fernandez JM, Gonzalez

LO, Aguirre A, Suarez A, Gonzalez JM, Escaff S and Vizoso FJ: Study

of TLR3, TLR4, and TLR9 in prostate carcinomas and their

association with biochemical recurrence. Cancer Immunol Immunother.

60:217–226. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Chuang HC, Huang CC, Chien CY and Chuang

JH: Toll-like receptor 3-mediated tumor invasion in head and neck

cancer. Oral Oncol. 48:226–232. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Chen C, Feng Y, Zou L, Wang L, Chen HH,

Cai JY, Xu JM, Sosnovik DE and Chao W: Role of extracellular RNA

and TLR3-trif signaling in myocardial Ischemia-reperfusion injury.

J Am Heart Assoc. 3:e0006832014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Cabrera-Fuentes HA, Ruiz-Meana M,

Simsekyilmaz S, Kostin S, Inserte J, Saffarzadeh M, Galuska SP,

Vijayan V, Barba I, Barreto G, et al: RNase1 prevents the damaging

interplay between extracellular RNA and tumour necrosis factor

alpha in cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost.

112:1110–1119. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Shimada BK, Yang Y, Zhu J, Wang S, Suen A,

Kronstadt SM, Jeyaram A, Jay SM, Zou L and Chao W: Extracellular

miR-146a-5p induces cardiac innate immune response and

cardiomyocyte dysfunction. Immunohorizons. 4:561–572. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Xu J, Feng Y, Jeyaram A, Jay SM, Zou L and

Chao W: Circulating plasma extracellular vesicles from septic mice

induce inflammation via MicroRNA- and TLR7-Dependent mechanisms. J

Immunol. 201:3392–3400. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Huang H, Zhu J, Gu L, Hu J, Feng X, Huang

W, Wang S, Yang Y, Cui P, Lin SH, et al: TLR7 Mediates acute

respiratory distress syndrome in sepsis by sensing extracellular

miR-146a. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 67:375–388. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Georges HM, Cassin C, Tong M and Abrahams

VM: TLR8-activating miR-146a-3p is an intermediate signal

contributing to fetal membrane inflammation in response to

bacterial LPS. Immunology. 172:577–587. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Hannestad UlF, Allard A, Nilsson K and

Rosén A: Prevalence of EBV, HHV6, HCMV, HAdV, SARS-CoV-2, and

Autoantibodies to Type I Interferon in Sputum from Myalgic

Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients. Viruses.

17:4222025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Simpkin AJ, McNicholas BA, Hannon D,

Bartlett R, Chiumello D, Dalton HJ, Gibbons K, White N, Merson L,

Fan E, et al: Correction: Effect of early and later prone

positioning on outcomes in invasively ventilated COVID-19 patients

with acute respiratory distress syndrome: Analysis of the

prospective COVID-19 critical care consortium cohort study. Ann

Intensive Care. 15:442025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Fakhraei R, Song Y, Kazi DS, Wadhera RK,

Lemos JA, Das SR, Morrow DA, Dahabreh IJ, Rutan CM, Thomas K and

Yeh RW: Social vulnerability and Long-term cardiovascular outcomes

after COVID-19 hospitalization: An analysis of the american heart

association COVID-19 registry linked with medicare claims data. J

Am Heart Assoc. 14:e0380732025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Wallach T, Raden M, Hinkelmann L, Brehm M,

Rabsch D, Weidling H, Krüger C, Kettenmann H, Backofen R and

Lehnardt S: Distinct SARS-CoV-2 RNA fragments activate Toll-like

receptors 7 and 8 and induce cytokine release from human

macrophages and microglia. Front Immunol. 13:10664562023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Liao TL, Liu HJ, Chen DY, Tang KT, Chen YM

and Liu PY: SARS-CoV-2 primed platelets-derived microRNAs enhance

NETs formation by extracellular vesicle transmission and TLR7/8

activation. Cell Commun Signal. 21:3042023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Guedes JR, Santana I, Cunha C, Duro D,

Almeida MR, Cardoso AM, de Lima MCP and Cardoso AL: MicroRNA

deregulation and chemotaxis and phagocytosis impairment in

Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 3:7–17. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Évora A, Garcia G, Rubi A, De Vitis E,

Matos AT, Vaz AR, Gervaso F, Gigli G, Polini A and Brites D:

Exosomes enriched with miR-124-3p show therapeutic potential in a

new microfluidic triculture model that recapitulates neuron-glia

crosstalk in Alzheimer's disease. Front Pharmacol. 16:14740122025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Kazemi M, Sanati M, Shekari Khaniani M and

Ghafouri-Fard S: A review on the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory

networks involved in inflammatory processes in Alzheimer's disease.

Brain Res. 1856:1495952025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Ravanidis S, Bougea A, Papagiannakis N,

Koros C, Simitsi AM, Pachi I, Breza M, Stefanis L and Doxakis E:

Validation of differentially expressed brain-enriched microRNAs in

the plasma of PD patients. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 7:1594–1607.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Currim F, Brown-Leung J, Syeda T, Corson

M, Schumann S, Qi W, Baloni P, Shannahan JH, Rochet JC, Singh R and

Cannon JR: Rotenone induced acute miRNA alterations in

extracellular vesicles produce mitochondrial dysfunction and cell

death. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 11:592025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Ishtiaq B, Paracha RZ, Nisar M, Ejaz S and

Hussain Z: Discovering promising drug candidates for Parkinson's

disease: Integrating miRNA and DEG analysis with molecular dynamics

and MMPBSA. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 39:82025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Wallach T, Mossmann ZJ, Szczepek M, Wetzel

M, Machado R, Raden M, Miladi M, Kleinau G, Krüger C, Dembny P, et

al: MicroRNA-100-5p and microRNA-298-5p released from apoptotic

cortical neurons are endogenous Toll-like receptor 7/8 ligands that

contribute to neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 16:802021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Park C, Lei Z, Li Y, Ren B, He J, Huang H,

Chen F, Li H, Brunner K, Zhu J, et al: Extracellular vesicles in

sepsis plasma mediate neuronal inflammation in the brain through

miRNAs and innate immune signaling. J Neuroinflammation.

21:2522024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Deng L, Gao R, Chen H, Jiao B, Zhang C,

Wei L, Yan C, Ye-Lehmann S, Zhu T and Chen C: Let-7b-TLR7 signaling

axis contributes to the Anesthesia/Surgery-induced cognitive