Introduction

The human placenta is a transient foetal organ

during pregnancy which is responsible for multiple vital functions,

including the transfer of nutrients/factors/gases between the

mother and the foetus, the removal of waste products from the

foetus, and immunoprotection for the foetus (1,2).

Among these functions, the placenta also acts as an endocrine

organ, secreting a number of key hormones (e.g., steroids) for the

maintenance of pregnancy and foetal development (1,2).

Asprosin was identified by Romere et al

(3) during investigation of

Neonatal Progeroid Syndrome (NPS), showing that its pathogenesis is

due to premature ablation of profibrillin-1 (pro-FBN1) by furin

(3). Patients with NPS have a

unique phenotype characterised by extreme leanness, low appetite,

lipodystrophy and insulin sensitivity. Asprosin is implicated in a

number of physiologic processes and is perhaps most known for its

glucogenic function, namely stimulating hepatic glucose secretion

via the G-protein-cAMP-PKA pathway (4). The receptor by which asprosin carries

out its glucogenic function has been established to be the mouse

olfactory receptor OLFR743, whilst in humans asprosin is thought to

act via the ortholog OR4M1 (4,5).

Asprosin has also been found to induce pro-inflammatory effects in

both skeletal muscle and pancreatic β cells, as well as in

macrophages, inducing the expression and secretion of

pro-inflammatory mediators, such as tumour necrosis factor α

(TNFα), and interleukins IL-1β, IL-8 and IL-12 (4,6,7).

Asprosin exerts these pro-inflammatory effects via Toll-like

receptor 4 (TLR4), Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and nuclear

factor-kappa B (NFκB) pathways (4,6,7).

Moreover, asprosin exerts orexigenic effects in

relation to its role in regulating appetite (4). In terms of its orexigenic function,

asprosin is able to cross the blood brain barrier activating

agouti-related protein neurons in the hypothalamus. This role is

modulated via the same G-protein-cAMP-PKA pathway, although here it

is thought to be through a different cell surface receptor, namely

the protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D (PTPRD) (8,9).

Mishra et al (8) showed

that genetic ablation of this ligand in a mouse model resulted in

strong loss of appetite, leanness and lack of response to

asprosin's orexigenic effects (8).

Notably, emerging studies point towards a role for asprosin in

reproduction. For example, asprosin levels are elevated in women

with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (10), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

(11), and preeclampsia (12). Asprosin has also been shown to

induce markers for ovarian folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis in

a mouse model (13). Given the

increasing evidence on the pleiotropic effects/roles of asprosin,

in the present study, we investigated the potential role of

asprosin in relation to placental cells in vitro, by

assessing its effects on the transcriptome of BeWo and JEG-3

placental cell lines. We have also expanded on our observations by

measuring the expression of FBN1/Furin and asprosin's candidate

receptors in normal placentas and comparing these to placentas from

GDM pregnancies.

Materials and methods

Tissue culture

To study placental function in vitro, we used

two established cell lines, namely the BeWo cell line which

secretes hormones and undergoes syncytialisation after treatment

with forskolin, and the JEG-3 cell line which does not undergo

substantial fusion (14). BeWo

cells were cultured using Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM)

Ham's F12 (Sigma Aldrich D8437) supplemented with 10% foetal Bovine

Serum (Sigma Aldrich F6765) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco

15140122) at 37°C with 5% CO2. JEG-3 cells were cultured

using Eagle's minimum essential medium (EBSS) with 2 mM Glutamine,

1% Non-Essential Amino Acids (NEAAs), 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate (NaP),

10% Foetal Bovine Serum (Sigma Aldrich F6765), and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco 15140122) at 37°C with 5%

CO2. Both cell lines were treated with 10 nM Recombinant

Human Asprosin (BioLegend, 761904) for 4 h. A wound healing assay

was also performed, as previously described (15).

RNA isolation and RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from cell lysates using a

Trizol/phenol-chlorophorm based method. Sample purity was assessed

using Nano Drop 2000C (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Only

samples with a ratio of absorbance A260/A280 between 1.8 and 2.1

were used. Triplicate samples were sequenced using the Illumina

NextSeq 500/550 Mid Output kit V2.5 (in-house sequencing unit).

Data were de-multiplexed and aligned to the human genome.

Expression data was analysed using R (v.4.2.3, The R Foundation for

Statistical Computinga), with the R studio desktop application

(RStudio) and with the use of specific packages; DSeq2 (v1.44),

pheatmap and ggplot2. For visualisation, volcano plots were

generated using R package ggplot2 (v.3.5.1). Differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) were identified for subsequent enrichment

analysis.

Gene expression/gene ontology

analysis

The identified DEGs, were then subjected to

functional enrichment analysis. Funrich (v3.1.3) (16) was accessed to provide a functional

annotation, including biological processes, pathways and molecular

functions. Enrichment analysis was also performed using Omics

playground (v3.44, BigOmics Analytics) (17) for the function comparison of the

genes in asprosin treated versus untreated BeWo and JEG-3

cells.

Human placental samples

Human placental tissue samples from patients with

GDM (n=4; four experimental replicates per sample, i.e., n=16), as

well as normal healthy placenta control samples (n=4; three

experimental replicates per sample, i.e., n=12) were obtained from

the Arden Tissue Bank at the University Hospital Coventry and

Warwickshire (UHCW) NHS Trust (ethical approval obtained by the

Arden Tissue Bank management committee and by the UHCW ethics

committee; NRES 18/SC/0180). Patient consent to participate in the

study and use their tissues was obtained, as specified in the

Declaration of Helsinki.

Fresh human placental tissue samples were collected

on the same day as the delivery/surgery on wet ice in 50 ml Falcon™

tubes full of RNAlater™ stabilization solution (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Samples were stored at 4°C until further

processing. Paraffin embedded human placental tissue slides were

also obtained from the Arden Tissue Bank at UHCW which were

collected on the same day as the delivery/surgery and were stored

short-term at room temperature until processing.

Isolation of mRNA, cDNA synthesis and

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from human placental tissue

using the Qiagen RNEasy Plus Mini Kit®. Sample purity

was assessed using Nano Drop 2000C (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Only samples with a ratio of A260/A280 between 1.8 and 2.1

were used. cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA

Reverse-Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems™) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. The cDNA samples were diluted to 10 ng/µl

RNA with nuclease free water and stored at −20°C until further

use.

SYBR Green-based assays

Exploring the expression of a number of genes in

both normal healthy and GDM human placental cDNA samples. Primers

were obtained from Harvard Primer Bank and RT-qPCR was run using

PowerUp SYBR® Green Master Mix. RT-qPCR was performed in

triplicate using the primers included in Table I.

| Table I.List of primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR in human placenta samples. |

Table I.

List of primers used for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR in human placenta samples.

| Name | Amplicon Size,

bp | Strand | Size (bases) | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| Furin | 108 | Forward | 22 |

TCGGGGACTATTACCACTTCTG |

|

|

| Reverse | 20 |

CCAGCCACTGTACTTGAGGC |

| PTPRDδ | 105 | Forward | 21 |

CAGGCGGAAGCGTTAATATCA |

|

|

| Reverse | 23 |

TTGGCATATCATCTTCAGGTGTC |

| OR4M1 | 100 | Forward | 23 |

TCTGTTAATGTCCTATGCCTTCC |

|

|

| Reverse | 20 |

AATGTGGGAATAGCAGGTGG |

| TLR4 | 94 | Forward | 23 |

AGTTGATCTACCAAGCCTTGAGT |

|

|

| Reverse | 23 |

GCTGGTTGTCCCAAAATCACTTT |

| FBN1 | 166 | Forward | 20 |

TTTAGCGTCCTACACGAGCC |

|

|

| Reverse | 21 |

CCATCCAGGGCAACAGTAAGC |

| Beta Actin | 140 | Forward | 20 |

CTGGAACGGTGAAGGTGACA |

|

|

| Reverse | 23 |

AAGGGACTTCCTGTAACAATGCA |

Taqman based-assays

For the purpose of validating the expression of the

top genes identified from RNA sequencing, RT-qPCR was performed in

triplicate using TaqMan™ Gene Expression Assays (Applied

Biosystems) and TaqMan™ Fast Advanced MasterMix (Applied

Biosystems). Details on the genes and assay IDs are presented in

Table II. All RT-qPCR experiments

were carried out on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System, 96-well

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Amplicon load was measured by

relative quantification using a ΔΔCq method.

| Table II.List of primers used for RNA

sequencing validation. |

Table II.

List of primers used for RNA

sequencing validation.

| Gene ID | Gene name | Amplicon Size,

bp | Assay ID |

|---|

| DDIT4 | DNA damage

inducible transcript 4 | 68 | Hs01111686_g1 |

| HK2 | Hexokinase II | 149 | Hs00606086_m1 |

| STC2 | Stanniocalcin

2 | 93 | Hs01063215_m1 |

| SLC2A1 | Solute carrier

family 2 member 1/glucose transporter 1 | 76 | Hs00892681_m1 |

| ZNF395 | Zinc finger protein

395 | 97 | Hs00608626_m1 |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase | 157 | Hs02786624_g1 |

In silico analysis

ThemiRDB, TargetScan, and ENCORI databases were

utilized to identify functional miRNA:TLR4 interactions

(18–20). Following this, the results from

these databases were plotted in a Venn diagram using FunRich

(21) to identify the more

efficacious mRNA target interactions. The database STRING (22) was used to identify the top

co-expressed genes with TLR4.

Statistical analysis

Differences identified in experiments were assessed

for statistical significance using the unpaired Student's t-test.

An assessment for homoscedasticity of data for each data set was

made using the F-test. If homoscedasticity was proven, an unpaired

Student's t-test was performed to assess significance. If the data

were not determined to be homoscedastic, an unpaired Student's

t-test with Welch's correction was performed to account for the

variance. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad

Prism® software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). P-values

<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Effect of asprosin on BeWo and JEG-3

cells

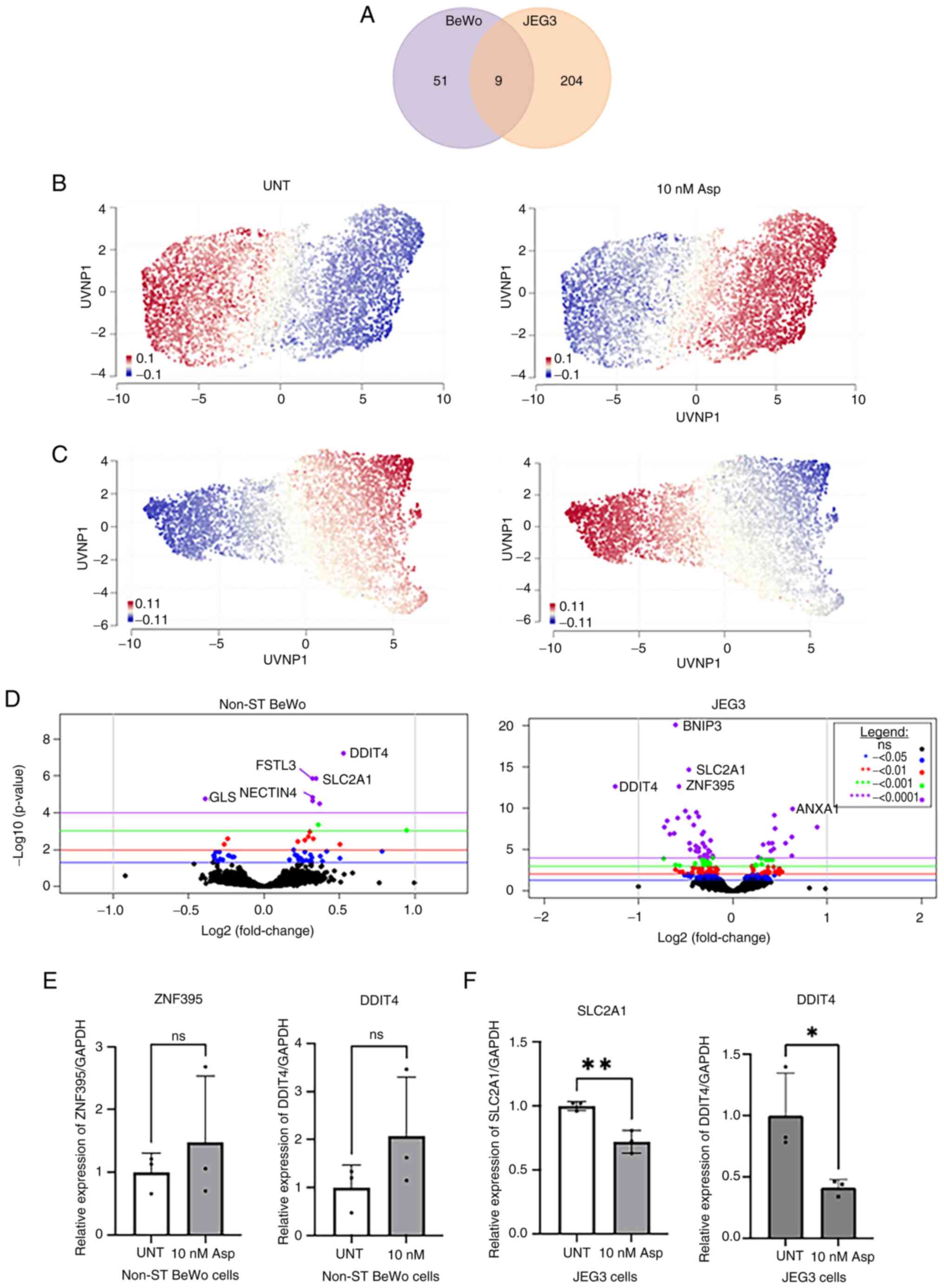

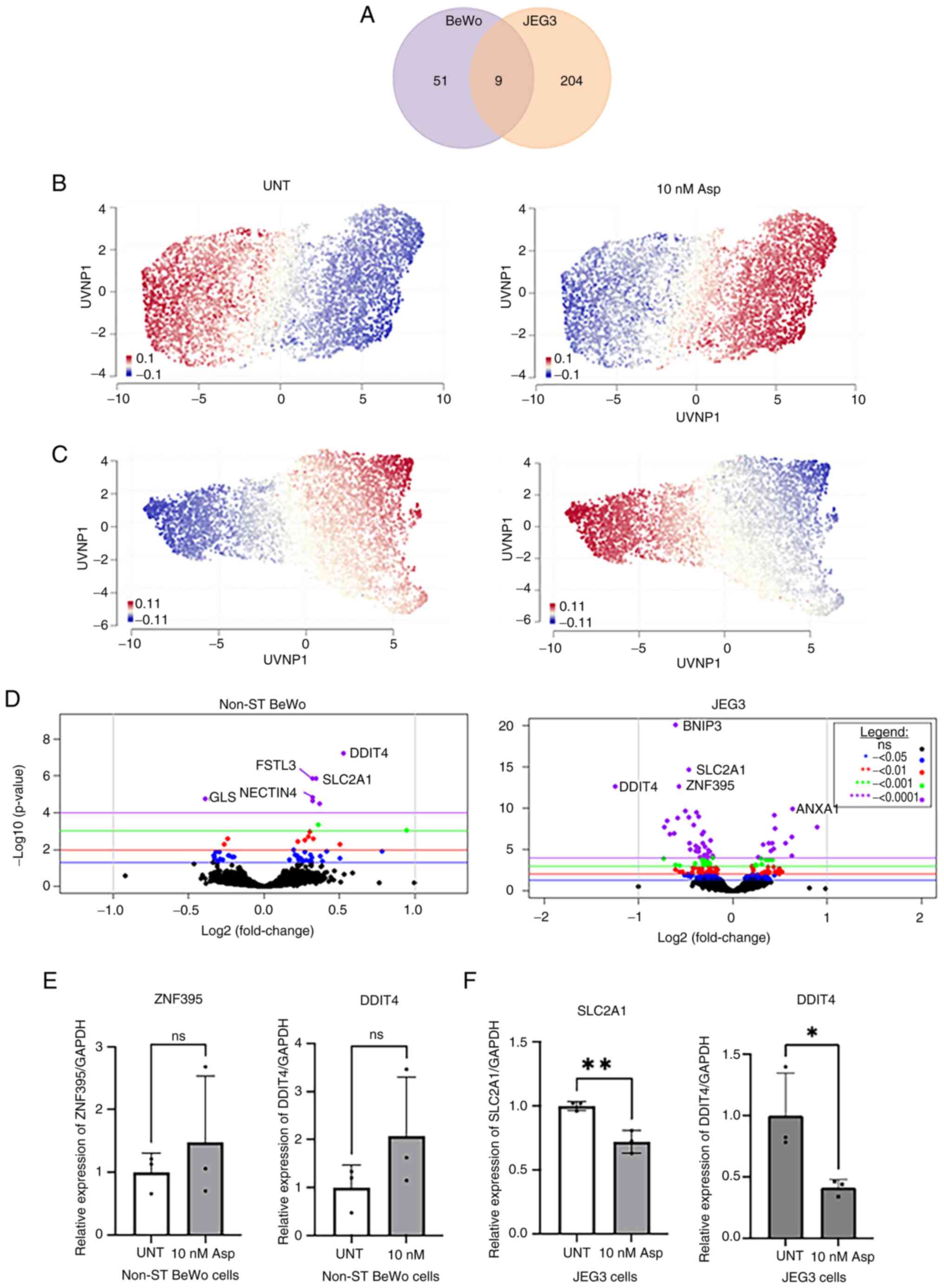

To gain a better insight into its role in the human

placental transcriptome, BeWo and JEG-3 cells were treated with

asprosin (10 nM for 4 h). RNA sequencing revealed that asprosin

induced cell specific differential expression for 51 genes (DEGs)

in BeWo cells, and 204 in JEG-3 cells, with nine common DEGs in

both in vitro models (Fig.

1A; Tables SI and SII). A Uniform Manifold Approximation

and Projection (UMAP) was constructed to display the up (red) and

down-regulated (blue) genes for BeWo and JEG-3 asprosin-treated and

control (i.e. untreated) samples (Fig. 1B,C). The results show a contrast

between the two cell lines in terms of treated and control samples

(see volcano plots, Fig. 1D). We

have used Taqman probes for validation of RNAseq data, for two up-

and down-regulated genes in BeWo (Fig.

1E), and JEG-3 (Fig. 1F)

cells, respectively. Despite the lack of significance in BeWo

asprosin-treated cells, a trend for upregulation of ZNF395

and DDIT4 was noted. In JEG-3 cells, both SLC2A1 and DDIT4

were significantly downregulated following treatment with asprosin

(P<0.001 and P<0.05 respectively).

| Figure 1.DEGs in BeWo and JEG-3 cells treated

with Asp. (A) A Venn diagram displaying the DEGs for Asp-treated

BeWo and JEG-3 cells when compared with their respective UNT

controls. (B and C) Geneset signature UMAP displaying up- and

down-regulated genes in different samples. UMAPs display genes

clustered by relative log-expression which were up- (red) or down-

(blue) regulated in (B) BeWo and (C) JEG-3 cells, UNT control and

10 nM Asp-treated samples. (D) Volcano plots for BeWo and JEG-3

cells, indicating the most up- and down-regulated DEGs. RNA

sequencing validation for (E) BeWo and (F) JEG-3 cells, using

reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. *P<0.05, **P<0.001.

DEGs, differentially expressed genes; UMAP, uniform manifold

approximation and projection; UNT, untreated; Asp, asprosin;

ZNF395, Zinc Finger Protein 395; DDIT4, DNA Damage Inducible

Transcript 4; SLC2A1, solute carrier family 2 member 1; Non-ST,

non-syncytialised; ns, not significant. |

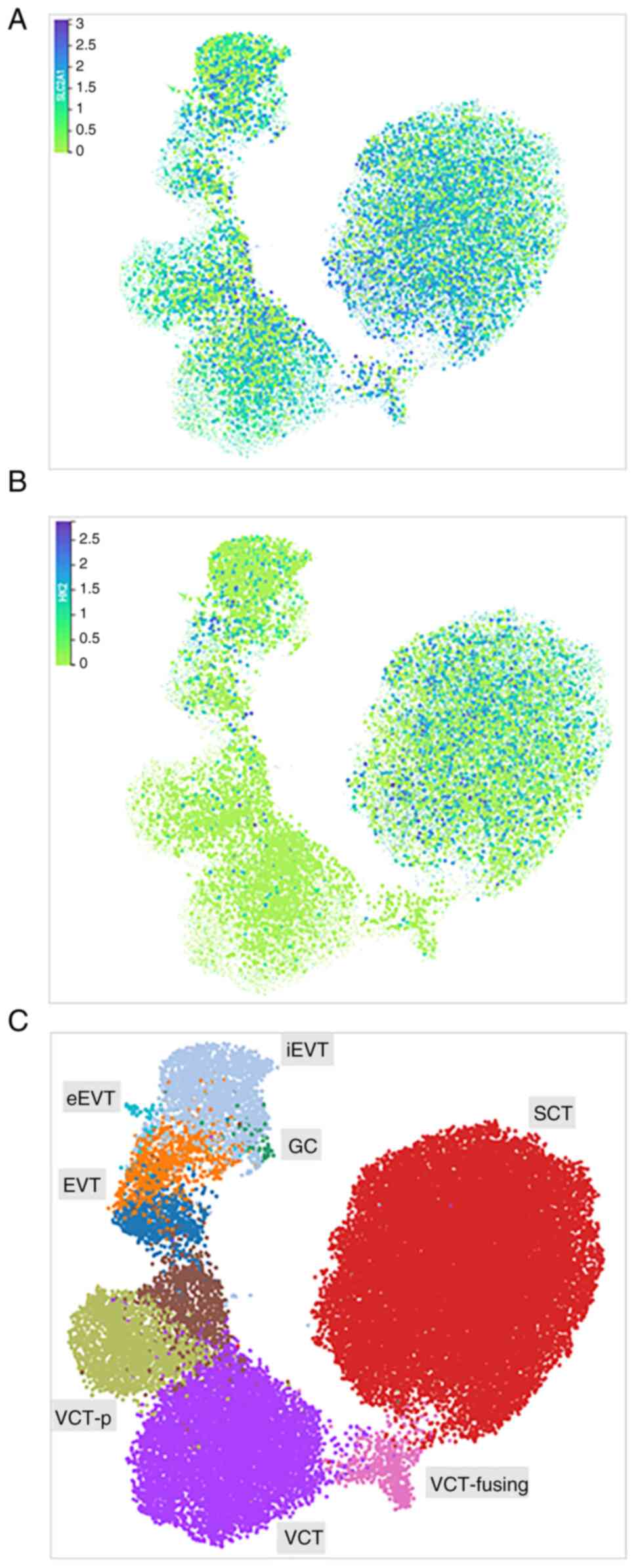

We have used a spatially resolved single-cell

multiomic characterization of the maternal-foetal interface

(reproductivecellatlas.org) (23)

to map the expression of SLCA1 and HK2 in a diverse trophoblast

population (Fig. 2). SLCA1 is

abundantly expressed in villous syncytiotrophoblasts (SCTs),

extravillous trophoblast cells (EVTs), and villous cytotrophoblast

cells (VCTs), as well as in placenta giant cells (GCs) (Fig. 2A and C). HK2 expression was

primarily confound in SCTs (Fig. 2B

and C).

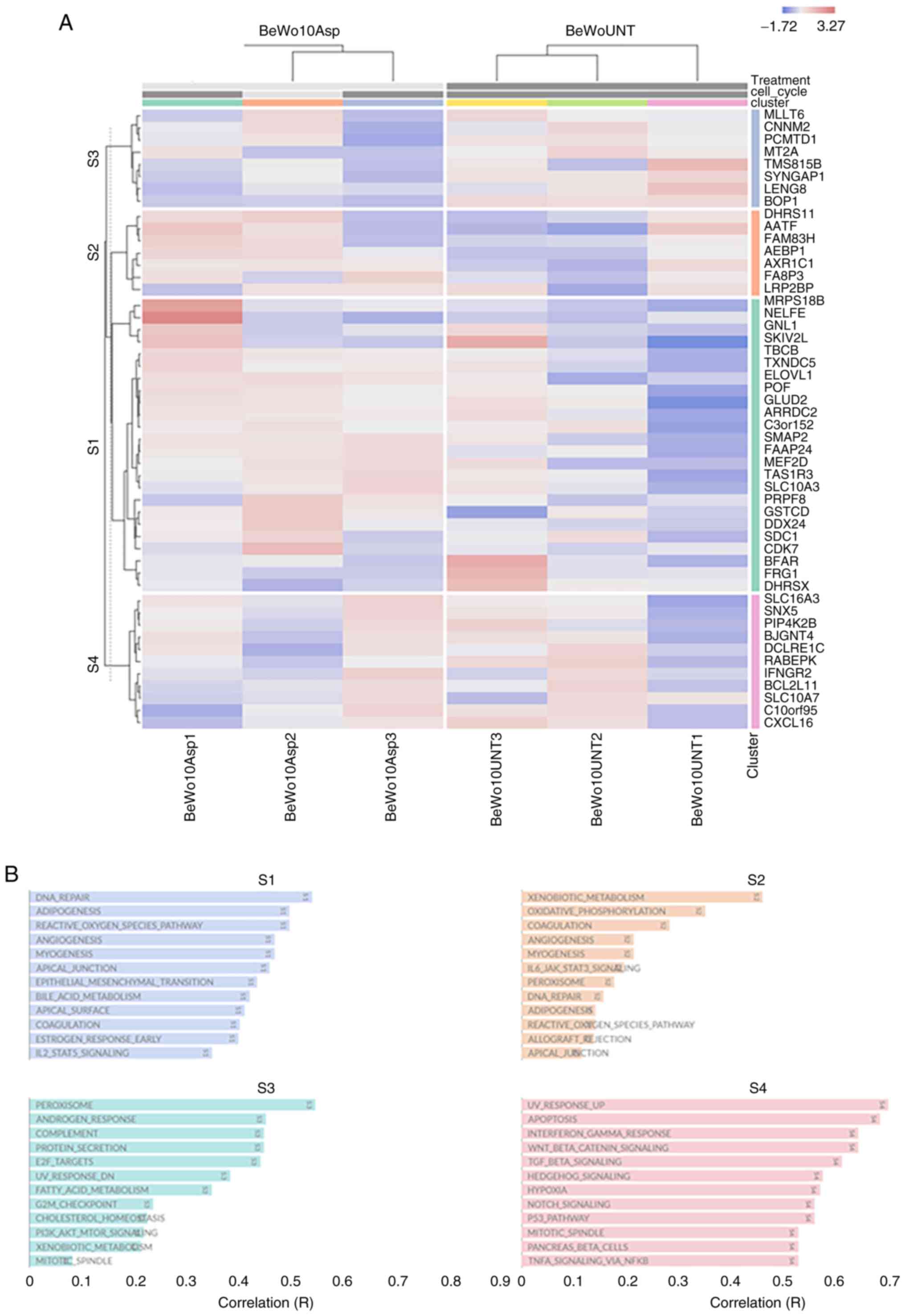

Heat map of top 50 DEGs identifies

four different clusters in both asprosin-treated cell lines

Fig. 3A presents

the functional heat map of the top 50 DEGs with highest standard

deviation across all samples (BeWo-treated vs. control). The

hierarchical clustering was performed at the gene level and

showcased four clusters S1-S4 (Fig.

3B). Many of these functional annotations are related to DNA

Repair, angiogenesis, fatty acid metabolism, mTOR/NOTCH/WNT/p53

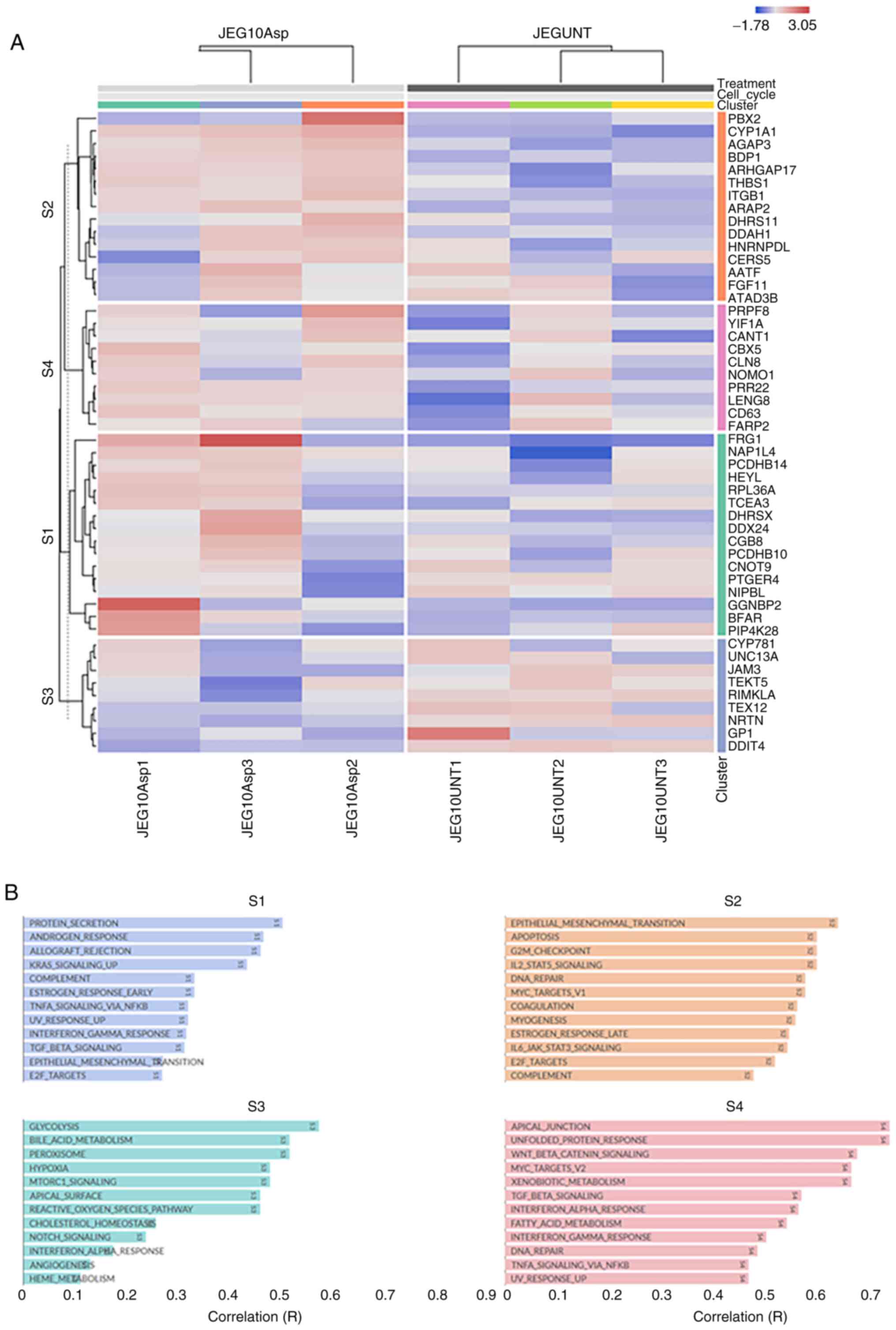

signalling. Similarly, four distinct clusters were identified in

JEG-3 treated samples (Fig. 4A),

including changes in protein secretion, glycolysis,

TGFβ/TNFα/KRAS/L2 signalling, hypoxia and steroid response

(Fig. 4B).

Gene enrichment analysis

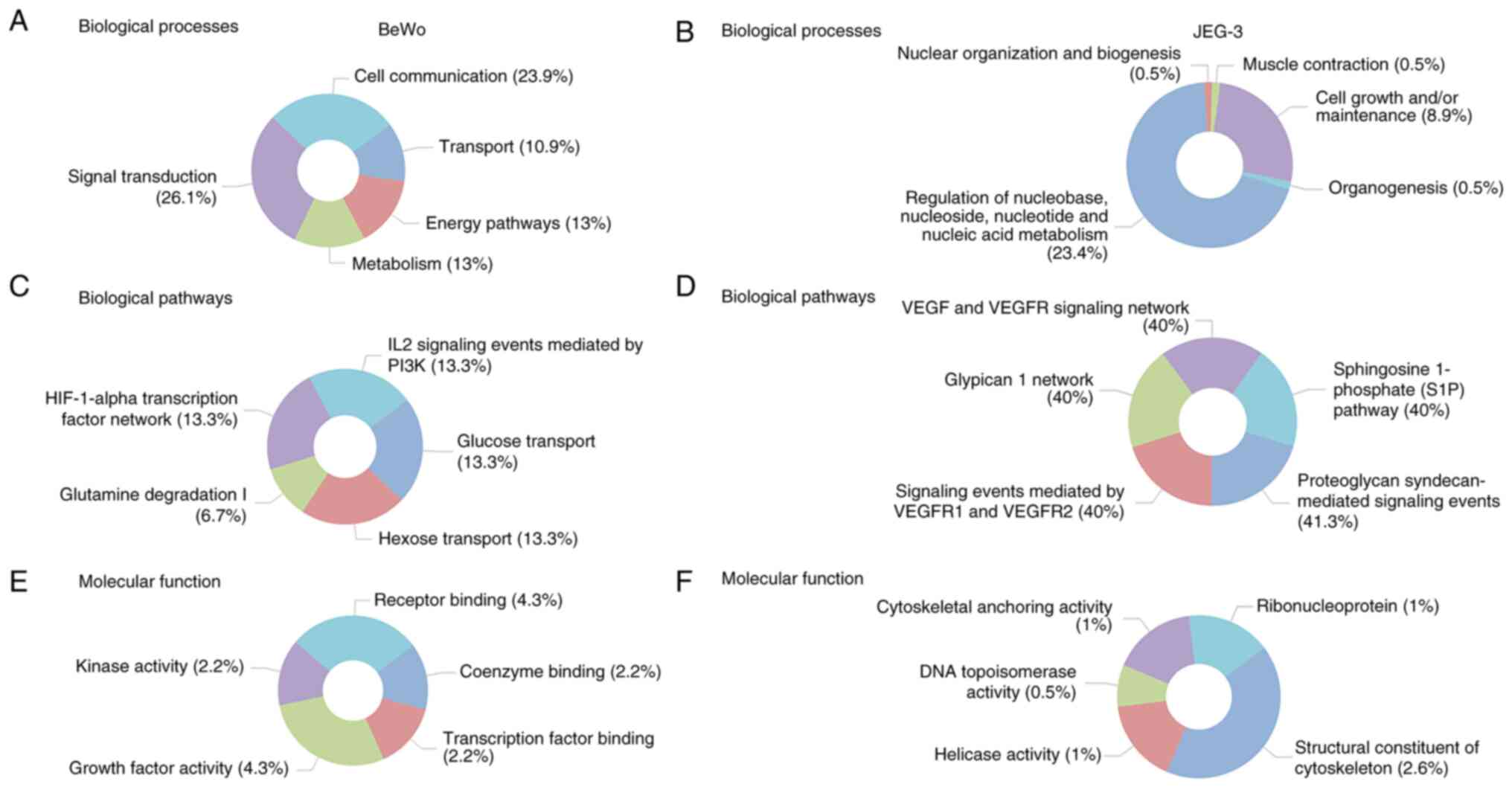

Funrich was used to determine the top five enriched

biological processes (Fig. 5A),

biological pathways (Fig. 5B), and

molecular functions (Fig. 5C) in

BeWo cells treated with asprosin. The main biological processes

identified as: signal transduction, cell communication, energy

pathways/metabolism, and transport. Glucose/Hexose transport were

two of the five biological pathways identified, underpinning the

role of asprosin in cell homeostasis. Enriched molecular functions

included receptor binding, growth factor and kinase activity.

Similar analyses were performed for the JEG-3

related DEGs, identifying the top five enriched biological

processes (Fig. 5D), biological

pathways (Fig. 5E), and molecular

functions (Fig. 5F). Most enriched

biological processes included regulation of nucleic acid

metabolism, and cell maintenance, whereas vascular endothelial

growth factor receptor (VEGFR) signalling predominated under

biological pathways. Contrary to BeWo cells, structural constituent

of the cytoskeleton was the most enriched molecular function in

JEG-3 cells. All p-values for the top five enriched biological

pathways, biological processes, and molecular pathways (depicted in

Fig. 5) are presented in Fig. S1.

Furthermore, we have assessed asprosin's role in

cell proliferation and migration in vitro, using BeWo cells.

When cells were treated with asprosin, no apparent differences were

observed at 24 or 48 h post asprosin treatment (Fig. S2A). The performed wound healing

assay at the same time-points indicated a potential cytostatic

effect for asprosin (Fig. S2B and

S2C).

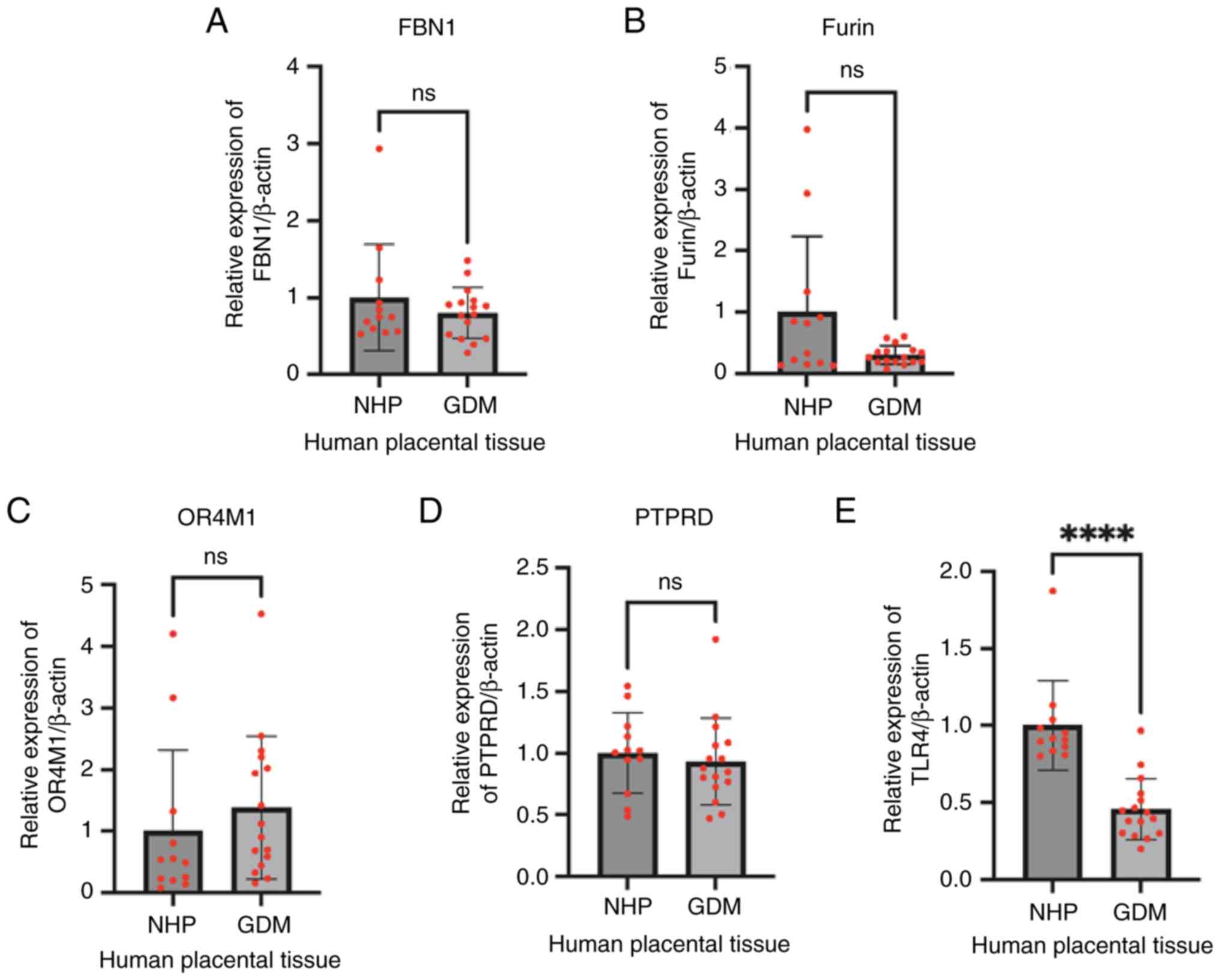

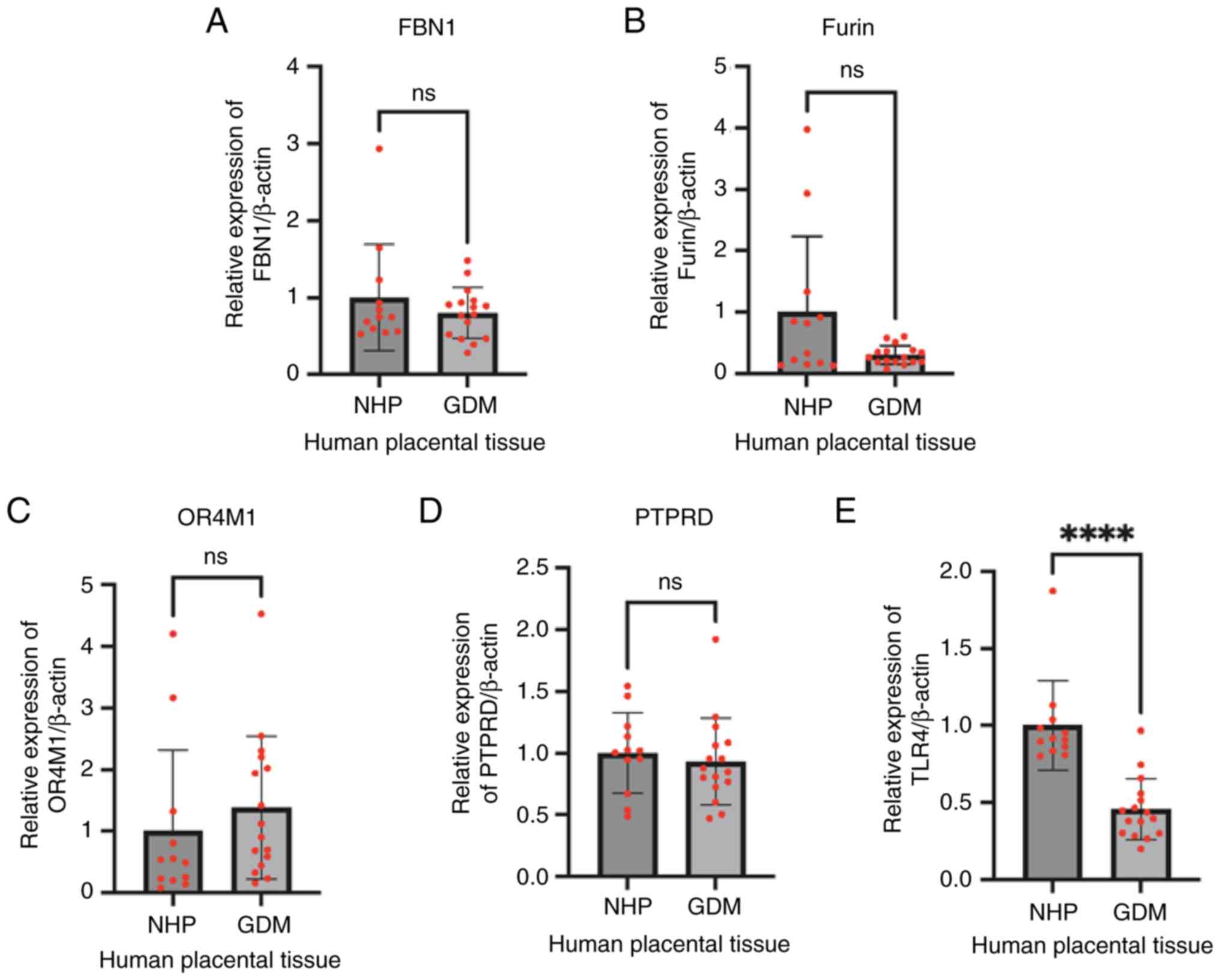

Expression of FBN1, Furin, OR4M1,

PTPRD and TLR4 in placentas from normal and GDM pregnancies

Expression of FBN1, Furin and putative asprosin

receptors was assessed in normal and GDM placentas at term. There

was no difference in the gene expression of either FBN1 (Fig. 6A) or Furin (Fig. 6B) between these two groups. Similar

expression of OR4M1 (Fig. 6C), and

PTPRD (Fig. 6D) was also noted

between normal and GDM samples, whereas TLR4 expression (Fig. 6E) was significantly downregulated

in GDM placentas compared to the controls (P<0.0001).

| Figure 6.Gene expression of (A) FBN1, (B)

Furin, (C) OR4M1, (D) PTPRD and (E) TLR4 in NHP (control) and GDM

placenta samples, as assessed by reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR. ****P<0.0001. FBN1, fibrillin-1; OR4M1, olfactory receptor

4M1; PTPRD, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D; GDM,

gestational diabetes mellitus; NHP, normal human placenta; ns, not

significant. |

Identification of miRNA:mRNA

interactions and investigation of TLR4 effects in signalling

pathways

Investigation of three predictive miRNA databases

was undertaken, namely miRDB, TargetScan, and ENCORI, which

identified 95, 1, and 91 interactions, respectively (Fig. S3A). The results showed that there

were 10 common miRNAs between ENCORI and miRDB targeting TLR4, and

only one common miRNA between miRDB and TargetScan. The 10 common

miRNAs are: hsa-miR-448, hsa-miR-642a-5p, hsa-miR-7-5p,

hsa-miR-25-3p, hsa-miR-367-3p, hsa-miR-363-3p, hsa-miR-92a-3p,

hsa-miR-92b-3p, hsa-miR-32-5p, and hsa-miR-655-3p. The one common

miRNA is hsa-miR-140-5p.

Given the most notable changes in receptor

expression rest with TLR4, we have performed STRING analysis, and

we have identified candidate proteins which have a cross-talk with

TLR4. The proteins are: TICAM1, TICAM2, IRAK4, TRAF6, TIRAP, TLR2,

LY96, TLR6, HSPD1, and HMGB1. With the exemption of TLR2, all other

interactions are experimentally determined (Fig. S3B).

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence of how

asprosin can change the placental transcriptome using two

well-characterised in vitro models. We have also measured

the expression of FBN1, the proteolytic enzyme furin, as well as

asprosin's putative receptors (OR4M1, PTPRD and TLR4) (9) in healthy (normal pregnancy) and GDM

placentas.

Asprosin treatment altered almost 4-fold more genes

in JEG-3 cells compared to BeWo cells, indicating their inherent

transcriptomic differences, as previously described (24). Of note, nine genes were similarly

affected in both these cell lines, namely SLC2A1, ZNF395, DDIT4,

HK2, STC2, RGS16, SH3PDXD2B, XYLT1 and CENPF. SLC2A1 encodes a

major placental glucose transporter (GLUT1), increases in

expression with gestation, and facilitates glucose uptake (25). Similarly, asprosin also affected

the expression of Hexokinase 2 (HK2), an enzyme which

phosphorylates glucose to glucose-6-phosphate, the first step in

most glucose metabolism pathways (26). Both GLUT1 and HK2 appear to be

upregulated in patients with GDM (27). Another link between asprosin and

glucose is suggested by the differential regulation of

stanniocalcin-2 (STC2), a gene which is also upregulated in GDM

placentas and inhibits trophoblast invasion under high-glucose

conditions (28). DNA Damage

Inducible Transcript 4 (DDIT4) has also been affected by asprosin.

This is also a crucial signalling pathway in the human placenta

which regulates cell proliferation by inhibiting the activity of

the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) (29,30).

Notably, it has been suggested that DDIT4 is critical for normal

decidualization and possibly involved in the development of

preeclampsia (31). For the

remaining genes (ZNF395, RGS16, SH3PDXD2B, XYLT1, CENPF) no data

are available for specific functions in the human placenta.

However, Xylosyltransferase 1 (XYLT1) has been described as an

insulin sensitizer (32), whilst

depletion of CENPF disrupts GLUT4 trafficking in murine cells

(33), and RGS16 induces insulin

secretion (34). Collectively,

this is the first time that a direct effect of asprosin as a

glucose sensor on key components, such as SLC2A1, HK2, and STC2,

has been shown at the placental level.

In accordance with their genetic/phenotypic

differences as trophoblastic cell lines, BigOmics analytics

generated four distinct pathway-related clusters for BeWo and JEG-3

cells based on RNAseq data. Despite some overlap, notable pathways

for JEG-3 cells include glycolysis, mTORC1, NOTCH, and KRAS

signalling. Common pathways include steroidal responses,

cholesterol homeostasis, xenobiotic and fatty acid metabolism, as

well as cytokine responses and hypoxia. Glycolysis is an important

process for the maintenance of the homeostasis of the

maternal-foetal interface, as well as ensuring normal gestation

(35). Dysregulation of glycolysis

has attracted interest for its role in pregnancy disorders,

including miscarriage, GDM and preeclampsia. Indeed, Lu et

al (36) have shown that NOTCH

signalling, glycolysis, and hypoxia were the main enriched area for

six preeclampsia-related genes, using the Gene Expression Omnibus

public database (36).

We have also explored DEG enrichment for both cell

lines in terms of the role of the DEGs in biological processes and

pathways, as well as molecular function using FunRich, where a

non-overlapping enrichment emerged when the two cell lines were

compared. In BeWo cells, the most enriched biological process with

mapped genes included GLS, HK2, TMX1, SGMS1, XYLT1 and ILVBL.

Corroborating previous data, glucose transport was the most

enriched biological pathway (SLC2A1, HK2); whereas the most

enriched molecular function was that of growth factor activity,

involving GDF15 and PGRN. Interestingly, low expression of growth

differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) has been associated with impaired

invasion of extravillous trophoblasts and predisposition to

pregnancy loss (37), whereas

progranulin (PGRN) deficient mice developed abnormal placental

angiogenesis (38). In JEG-3

cells, nucleic acid metabolism and VEGF signalling were amongst the

most enriched biological processes and pathways. VEGF is a key

angiogenic factor that affects not only endothelial cells, but also

trophoblasts (39). Impaired

glucose tolerance appears to affect the expression of placental

VEGFRs (40). Contrary to BeWo

cells, ‘structural constituents of the cytoskeleton’ was the most

enriched molecular function in JEG-3 cells. For this function,

mapped genes included DSP, KRT19, ERRFI1, ACTB and ACTR1A; none of

which have any known placental-specific functions assigned.

Of note, HK2 and SLC2A1 expression was noted during

embryo morphogenesis (in the period between implantation and

gastrulation) (41); particularly

in cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, but not in epiblasts

or hypoblasts (see Fig. S4). The

presence of these genes as early as nine days post-fertilisation,

suggests an important role for embryonic development. Moreover,

when cytotrophoblast cells (BeWo cells) were treated with asprosin

over 48 h, no apparent changes were noted in cell proliferation,

corroborating previous human and animal studies (supplementary

data) (42,43). Future studies should use ex

vivo or in vivo models, or even more comprehensive

clinical studies to confirm the role(s) and mechanism(s) of

asprosin in the overall pregnancy environment.

Following RNA sequencing analysis, we investigated

the expression of FBN1, Furin, OR4M1, PTPRD and TLR4 in healthy and

GDM placentas. Early studies have shown increased plasma asprosin

levels in pregnant women with GDM as early as 18–20 weeks of

gestation (44). More recently,

Boz et al (11) showed that

asprosin levels were elevated in pregnant women with normal glucose

tolerance or with GDM when compared to healthy non-pregnant

controls (11). In the present

study, no difference in the expression of FBN1 and Furin was noted

between GDM and healthy placentas. This suggests that the source of

elevated asprosin in GDM pregnancies is not likely the placenta.

Indeed, GDM is associated with elevated maternal body mass index

(BMI), so it is possible that increased in adiposity drives higher

release of asprosin in circulation. For example, a positive

correlation between placental asprosin immunoreactivity and BMI has

been shown (45). In terms of the

putative asprosin receptors, only TLR4 was significantly

downregulated in GDM placentas in our study. Numerous studies have

shown that TLR4-mediated signalling plays a pivotal role in immune

and inflammatory processes (46).

Moreover, a TLR4/NF-κB/PFKFB3 signalling cascade might provide a

link between glycometabolism and trophoblastic pyroptosis (47). However, a previous study has

reported elevated levels of TLR4 in patients with GDM (48). Thus, more studies are needed to

determine the potential differences in the expression of asprosin

receptors at both gene and protein level in GDM and other pregnancy

complications.

Of note, relating to the identified potential miRNA

interactions with TLR4, there is good evidence for involvement of

hsa-miR-7-5p, hsa-miR-92a-3p, and hsa-miR-32-5p in GDM/obesity. For

example, miRNA 32 and 92a-3p are upregulated in GDM (49,50),

whereas hsa-miR-7-5p expression was reduced at 21 days post

bariatric surgery (51). STRING

motif also revealed interactions implicated in GDM. For example, it

has been suggested that the miR-146a-3p/TRAF6 interaction might

play a key role in the pathogenesis of GDM (52), whereas HMGB1 expression is

increased as a result of tissue damage due to inflammation and

oxidative stress related to GDM (53). Following analyses of cord blood

samples from diabetic and normal pregnancies, it was shown that

maternal diabetes drives a profound inflammatory activation in

neonates that involves TLR1/2 or TRL5 (54). It should be noted that there is a

further interplay between TLR2 and TLR4, since it has been shown

that, under foetal exposure to GDM conditions, TLR4 and TLR2 can

activate IL-1β responses in rat offspring spleen cells (55). This corroborates a previous in

vivo study, where C57BL/6 mice lacking TLR4 (TLR4-knockout,

TLR4−/− mice) were partially protected from high-fat

diet-induced insulin resistance, suggesting that TLR4 acts as

molecular link among pro-inflammatory responses, nutrition, and

lipids (56).

To conclude, the present study provides a novel

insight into the actions of asprosin in two well-established in

vitro placental (trophoblast) models, identifying key genes and

signalling pathways. Based on the present findings, a common theme

that emerged is that of glucose homeostasis, in accordance with the

physiologic role of this adipokine. Future work is needed to

understand the exact role of asprosin in health and disease (e.g.

in GDM) expanding on in vitro models (e.g.,

syncytialised BeWo cells), using primary placental cells, as well

as trying to recapitulate better the placental microenvironment

using 3D cultures.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The General Charities of the City of Coventry (grant no.

RMV1169CSA).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JC, HSR, IK and EK conceptualised the study. SO, SG

and EK acquired and analysed data. SO, VP, SG, JK, SS, EK, IK and

HSR performed the formal analysis. HSR and IK were responsible for

funding. HSR, IK and EK were involved in the investigation. SO, SG,

SS, VP and EK were involved in the methodology. HSR, IK, EK

administered the project. HSR, EK and IK supervised the study. EK,

SS and SO visualised the data. EK, SO, JC and IK wrote the original

draft. JC, EK, SO, IK, SS and HSR wrote and edited the final draft.

EK and HSR confirm the authenticity of the data. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Human placental tissue samples were obtained from

the Arden Tissue Bank at the University Hospital Coventry and

Warwickshire NHS Trust (ethical approval obtained by the Arden

Tissue Bank management committee and by the UHCW ethics committee;

NRES 18/SC/0180). Patients provided written informed consent to

participate.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Costa J, Mackay R, De Aguiar Greca SC,

Corti A, Silva E, Karteris E and Ahluwalia A: The role of the 3Rs

for understanding and modeling the human placenta. J Clin Med.

10:34442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Herrick EJ and Bordoni B: Embryology,

placenta. StatPearls (Internet). StatPearls Publishing; Treasure

Island, FL: 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551634/November

11–2024

|

|

3

|

Romere C, Duerrschmid C, Bournat J,

Constable P, Jain M, Xia F, Saha PK, Del Solar M, Zhu B, York B, et

al: Asprosin, a fasting-induced glucogenic protein hormone. Cell.

165:566–579. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shabir K, Brown JE, Afzal I, Gharanei S,

Weickert MO, Barber TM, Kyrou I and Randeva HS: Asprosin, a novel

pleiotropic adipokine implicated in fasting and obesity-related

cardio-metabolic disease: Comprehensive review of preclinical and

clinical evidence. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 60:120–132. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kerslake R, Hall M, Vagnarelli P,

Jeyaneethi J, Randeva H, Pados G, Kyrou I and Karteris E: A

pancancer overview of FBN1, asprosin and its cognate receptor OR4M1

with detailed expression profiling in ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett.

22:6502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Shabir K, Gharanei S, Orton S, Patel V,

Chauhan P, Karteris E, Randeva HS, Brown JE and Kyrou I: Asprosin

exerts pro-inflammatory effects in THP-1 macrophages mediated via

the Toll-like Receptor 4 (TLR4) pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 24:2272022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee T, Yun S, Jeong JH and Jung TW:

Asprosin impairs insulin secretion in response to glucose and

viability through TLR4/JNK-mediated inflammation. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 486:96–104. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mishra I, Xie WR, Bournat JC, He Y, Wang

C, Silva ES, Liu H, Ku Z, Chen Y, Erokwu BO, et al: Protein

tyrosine phosphatase receptor δ serves as the orexigenic asprosin

receptor. Cell Metab. 34:549–563.e8. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Orton S, Karkia R, Mustafov D, Gharanei S,

Braoudaki M, Filipe A, Panfilov S, Saravi S, Khan N, Kyrou I, et

al: In silico and in vitro mapping of receptor-type protein

tyrosine phosphatase receptor type D in health and disease:

Implications for asprosin signalling in endometrial cancer and

neuroblastoma. Cancers (Basel). 16:5822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ozturk HA and Arici FN: Achilles tendon

thickness and serum asprosin level significantly increases in

patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. PeerJ. 12:e179052024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Boz İB, Aytürk Salt S, Salt Ö, Sayın NC

and Dibirdik İ: Association between plasma asprosin levels and

gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes.

16:2515–2521. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shafi N, Bano F and Uraneb S: The role of

novel hormone asprosin in insulin resistance during preeclampsia.

Pak J Pharm Sci. 34 (Suppl 3):1039–1043. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Banerjee A, Vishesh C, Anamika Tripathy M

and Umesh R: Asprosin-mediated regulated of ovarian functions in

mice: An age-dependent study. Peptides. 181:1712932024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Msheik H, El Hayek S, Bari MF, Azar J,

Abou-Kheir W, Kobeissy F, Vatish M and Daoud G: Transcriptomic

profiling of trophoblast fusion using BeWo and JEG-3 cell lines.

Mol HumReprod. 25:811–824. 2019.

|

|

15

|

Morea A, Saravi S, Sisu C, Hall M, Tosi S,

Karteris E and Storlazzi CT: Effect of MYC and PARP inhibitors in

ovarian cancer using an In-Vitro model. Anticancer Res.

44:1817–1827. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

FunRich, . Functional Enrichment Analysis

Tool. http://www.funrich.org/December

28–2024

|

|

17

|

BigOmics Analytics, . Omics Analysis

Software. BigOmics Analytics SA; Lugano: 2019, https://bigomics.ch/December 28–2024

|

|

18

|

Chen Y and Wang X: miRDB: An online

database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic

Acids Res. 48:D127–D131. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW and Bartel DP:

Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs.

Elife. 4:e050052015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Li JH, Liu S, Zhou H, Qu LH and Yang JH:

starBase v2.0: Decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA

interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids

Res. 42:D92–D97. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pathan M, Keerthikumar S, Ang CS, Gangoda

L, Quek CY, Williamson NA, Mouradov D, Sieber OM, Simpson RJ, Salim

A, et al: FunRich: An open access standalone functional enrichment

and interaction network analysis tool. Proteomics. 15:2597–2601.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M,

Nastou K, Mehryary F, Hachilif R, Gable AL, Fang T, Doncheva NT,

Pyysalo S, et al: The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein

association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any

sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D638–D646.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Arutyunyan A, Roberts K, Troulé K, Wong

FCK, Sheridan MA, Kats I, Garcia-Alonso L, Velten B, Hoo R,

Ruiz-Morales ER, et al: Spatial multiomics map of trophoblast

development in early pregnancy. Nature. 616:143–151. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Burleigh DW, Kendziorski CM, Choi YJ,

Grindle KM, Grendell RL, Magness RR and Golos TG: Microarray

analysis of BeWo and JEG3 trophoblast cell lines: Identification of

differentially expressed transctripts. Placenta. 28:383–389. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lynch CS, Kennedy VC, Tanner AR, Ali A,

Winger QA, Rozance PJ and Anthony RV: Impact of placental SLC2A3

deficiency during the first-half of gestation. Int J Mol Sci.

23:125302022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Tan VP and Miyamoto S: HK2/hexokinase-II

integrates glycolysis and autophagy to confer cellular protection.

Autophagy. 11:963–964. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Song TR, Su GD, Chi YL, Wu T, Xu Y and

Chen CC: Dysregu-lated miRNAs contribute to altered placental

glucose metabolism in patients with gestational diabetes via

targeting GLUT1 and HK2. Placenta. 105:14–22. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lai R, Ji L, Zhang X, Xu Y, Zhong Y, Chen

L, Hu H and Wang L: Stanniocalcin2 inhibits the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion of trophoblasts via

activation of autophagy under high-glucose conditions. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 547:1115982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mparmpakas D, Zachariades E, Goumenou A,

Gidron Y and Karteris E: Placental DEPTOR as a stress sensor during

pregnancy. Clin Sci (Lond). 122:349–359. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mparmpakas D, Zachariades E, Foster H,

Kara A, Harvey A, Goumenou A and Karteris E: Expression of mTOR and

downstream signalling components in the JEG-3 and BeWo human

placental choriocarcinoma cell lines. Int J Mol Med. 25:65–69.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yang J, Zhang Y, Tong J, Lv H, Zhang C and

Chen ZJ: Dysfunction of DNA damage-inducible transcript 4 in the

decidua is relevant to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Biol

Reprod. 98:821–833. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Orioli L, Canouil M, Sawadogo K, Ning L,

Deldicque L, Lause P, de Barsy M, Froguel P, Loumaye A, Deswysen Y,

et al: Identification of myokines susceptible to improve glucose

homeostasis after bariatric surgery. Eur J Endocrinol. 189:409–421.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pooley RD, Moynihan KL, Soukoulis V, Reddy

S, Francis R, Lo C, Ma LJ and Bader DM: Murine CENPF interacts with

syntaxin 4 in the regulation of vesicular transport. J Cell Sci.

121:3413–3421. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Vivot K, Moullé VS, Zarrouki B, Tremblay

C, Mancini AD, Maachi H, Ghislain J and Poitout V: The regulator of

G-protein signaling RGS16 promotes insulin secretion and β-cell

proliferation in rodent and human islets. Mol Metab. 26:988–996.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Gou R and Zhang X: Glycolysis: A fork in

the path of normal and pathological pregnancy. FASEB J.

37:e232632023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lu X, Lan X, Fu X, Li J, Wu M, Xiao L and

Zeng Y: Screening preeclampsia genes and the effects of CITED2 on

trophoblastic function. Int J Gen Med. 17:3493–3509. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lyu C, Ni T, Guo Y, Zhou T, Chen ZJ, Yan J

and Li Y: Insufficient GDF15 expression predisposes women to

unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss by impairing extravillous

trophoblast invasion. Cell Prolif. 56:e135142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xu B, Chen X, Ding Y, Chen C, Liu T and

Zhang H: Abnormal angiogenesis of placenta in progranulin-deficient

mice. Mol Med Rep. 22:3482–3492. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shibuya M: Vascular endothelial growth

factor (VEGF) and its receptor (VEGFR) signaling in angiogenesis: A

crucial target for anti- and pro-angiogenic therapies. Genes

Cancer. 2:1097–1105. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Marini M, Vichi D, Toscano A, Thyrion GD,

Bonaccini L, Parretti E, Gheri G, Pacini A and Sgambati E: Effect

of impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy on the expression of

VEGF receptors in human placenta. Reprod Fertil Dev. 20:789–801.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Molè MA, Coorens THH, Shahbazi MN,

Weberling A, Weatherbee BAT, Gantner CW, Sancho-Serra C, Richardson

L, Drinkwater A, Syed N, et al: A single cell characterisation of

human embryogenesis identifies pluripotency transitions and

putative anterior hypoblast centre. Nat Commun. 12:36792021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang Z, Tan Y, Zhu L, Zhang B, Feng P,

Gao E, Xu C, Wang X, Yi W and Sun Y: Asprosin improves the survival

of mesenchymal stromal cells in myocardial infarction by inhibiting

apoptosis via the activated ERK1/2-SOD2 pathway. Life Sci.

231:1165542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Lu Y, Liu C, Pang X, Chen X, Wang C and

Huang H: Bioinformatic identification of signature miRNAs

associated with fetoplacental vascular dysfunction in gestational

diabetes mellitus. Biochem Biophys Reps. 41:1018882024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zhong L, Long Y, Wang S, Lian R, Deng L,

Ye Z, Wang Z and Liu B: Continuous elevation of plasma asprosin in

pregnant women complicated with gestational diabetes mellitus: A

nested case-control study. Placenta. 93:17–22. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Hoffmann T, Morcos YAT, Janoschek R,

Turnwald EM, Gerken A, Müller A, Sengle G, Dötsh J, Appel S and

Hucklenbruch-Rother E: Correlation of metabolic characteristics

with maternal, fetal and placental asprosin in human pregnancy.

Endocr Connect. 11:e2200692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Barboza R, Lima FA, Reis AS, Murillo OJ,

Peixoto EPM, Bandeira CL, Fotoran WL, Sardinha LR, Wunderlich G,

Bevilacqua E, et al: TLR4-mediated placental pathology and

pregnancy outcome in experimental malaria. Sci Rep. 7:86232017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang Y, Liu W, Zhong Y, Li Q, Wu M, Yang

L, Liu X and Zou L: Metformin corrects glucose metabolism

reprogramming and NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis via

inhibiting the TLR4/NF-κβ/PFKFB3 signaling in trophoblasts:

Implication for a potential therapy of preeclampsia. Oxid Med Cell

Longev. 2021:18063442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhou J, Bai J, Guo Y, Fu L and Xing J:

Higher levels of triglyceride, fatty acid translocase, and

toll-like receptor 4 and lower level of HDL-C in pregnant women

with GDM and their close correlation with neonatal weight. Gynecol

Obstet Invest. 86:48–54. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Batalha IM, Maylem ERS, Spicer LJ, Pena

Bello CA, Archilia EC and Shütz LF: Effects of asprosin on

estradiol and progesterone secretion and proliferation of bovine

granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 565:1118902023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Vasu S, Kumano K, Darden CM, Rahman I,

Lawrence MC and Naziruddin B: MicroRNA signatures as future

biomarkers for diagnosis of diabetes states. Cells. 8:15332019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Atkin SL, Ramachandran V, Yousri NA,

Benurwar M, Simper SC, McKinlay R, Adams TD, Najafi-Shoushtari SH

and Hunt SC: Changes in blood microRNA expression and early

metabolic responsiveness 21 days following bariatric surgery. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9:7732019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chen M and Yan J: A preliminary integrated

analysis of miRNA-mRNA expression profiles reveals a role of

miR-146a-3p/TRAF6 in plasma from gestational diabetes mellitus

patients. Ginekol Pol. 95:627–635. 2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Oğlak SC, Aşir F, Yılmaz EZ, Bolluk G,

Korak T and Ağaçayak E: The immunohistochemical and bioinformatics

analysis of the placental expressions of vascular cell adhesion

protein 1 (VCAM-1) and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) proteins

in gestational diabetic mothers. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol.

229:90–98. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Yanai S, Tokuhara D, Tachibana D, Saito M,

Sakashita Y, Shintaku H and Koyama M: Diabetic pregnancy activates

the innate immune response through TLR5 or TLR1/2 on neonatal

monocyte. J Reprod Immunol. 117:17–23. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Li QP, Pereira TJ, Moyce BL, Mahood TH,

Doucette CA, Rempel J and Dolinsky VW: In utero exposure to

gestational diabetes mellitus conditions TLR4 and TLR2 activated

IL-1beta responses in spleen cells from rat offspring. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1862:2137–2146. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I,

Yin H and Flier JS: TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty

acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 116:3015–3025.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|