Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is known for its dire survival

outcomes, with only about 12% of patients surviving beyond five

years (1). This disease is

expected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related

deaths in the United States by 2040 (2). The late stage at diagnosis and high

rate of recurrence after surgery significantly hinder long-term

survival rates for those affected (3). Surgical resection is possible for

merely 20% of these patients, as half of all cases are diagnosed

after the cancer has metastasized to distant organs (4,5).

Presently, the cornerstone of treatment for pancreatic cancer is

combination therapy. This approach integrates traditional

modalities like surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy with more

novel strategies such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy

(6). Given this context, the

development of novel anticancer agents with varied mechanisms of

action is crucial to enhance the efficacy of combination therapy in

treating pancreatic cancer.

Rupatadine, primarily known as a selective

antagonist for the histamine H1 receptor and platelet-activating

factor (PAF) for treating allergic rhinitis, has garnered attention

for its potential anticancer effects (7–9). Its

anticancer properties first stem from its ability to induce

lysosomal membrane permeabilization, releasing lysosomal hydrolases

into the cytoplasm, which damages mitochondria and initiates

apoptosis. Further research has demonstrated Rupatadine's

capability to disrupt the TGFβ1 signaling pathway, a critical

promoter of cancer cell invasion, angiogenesis, and immune evasion

within the tumor microenvironment, thus playing a significant role

in hindering tumor progression and metastasis. Studies have shown

that Rupatadine's influence on the TGF-β signaling pathway may also

involve modulation of associated pathways such as PAF, NF-κB, and

p65, thereby broadening its therapeutic potential (10–13).

Despite extensive research exploring Rupatadine as a

potential anticancer agent across various cancer types (14–17),

its specific impact on pancreatic cancer has not been thoroughly

examined. This study is designed to rigorously assess Rupatadine's

anticancer efficacy through comprehensive in vitro and in

vivo experiments utilizing pancreatic cancer models. The

principal aim of this study is to elucidate the molecular and

cellular mechanisms by which Rupatadine influences pancreatic tumor

cells. Furthermore, this research seeks to enhance our

understanding of Rupatadine's pharmacological attributes and lay

the groundwork for its potential clinical applications in

oncology.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The AsPC-1 (passage 11) and MIA PaCa-2 (passage 13)

pancreatic cancer cell lines were obtained from the Korea Cell Line

Bank (KCLB). KCLB routinely authenticates cell lines via short

tandem repeat (STR) profiling to confirm their identity and screen

for contamination. All cell lines were cultured under standard

conditions and used at the specified passage numbers to ensure

experimental consistency. Cultivation of AsPC-1 cells was conducted

using Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium (Hyclone).

Concurrently, MIA PaCa-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified

Eagle's medium (DMEM)/High (Hyclone). Both media were enriched with

a supplement comprising 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), and

1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco BRL). The cell lines were

incubated at a temperature of 37°C in a humidified environment,

with a 5% CO2 atmosphere to ensure optimal growth

conditions.

Cell viability assay

The assessment of cell viability for both AsPC-1 and

MIA PaCa-2 cell lines was performed utilizing the Ez-cytox Cell

Viability Assay Kit (Itsbio) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. All experiments were performed in triplicate (n=3) to

ensure reproducibility and statistical significance.

Western blot analysis

Lysis of AsPC-1and MIA PaCa-2 cells, as well as

mouse tissue samples, was carried out using the EzRIPA Lysis kit

(ATTO Corporation). Protein concentration was determined using the

Bradford assay reagent (Bio-Rad). For protein visualization,

Western blot analysis was performed using primary antibodies at a

1:1,000 dilution, obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. This was

followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated

secondary antibodies at a 1:2,000 dilution, sourced from Vector

Laboratories. Detection of specific immune complexes was achieved

using the Western Blotting Plus Chemiluminescence Reagent

(Millipore). The primary antibodies used targeted hPARP (Cell

Signaling Technology, #9542), MCL-1 (Cell Signaling Technology,

#5453), cleaved-caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, #9664),

TGF-βR1 (Abcam, ab31013), p-SMAD2/3 (Cell Signaling Technology,

#8828s), SMAD2/3 (Cell Signaling Technology, #5678s), human

E-cadherin (Abcam, ab76055), Vimentin (Abcam, ab92547), Snail,

(Cell Signaling Technology, #3879), PUMA (Cell Signaling

Technology, #98672), and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, A5541). All

experiments were performed in triplicate (n=3) to ensure

reproducibility and statistical significance.

Immunocytochemistry analysis

AsPC-1and MIA PaCa-2 were seeded into 8-well plate

(SPL Life Science) at the concentration of 8,000 cells/well. After

cultured overnight, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

at room temperature for 10 min. Then the cells were blocked with

incubation buffer (Normal Hores serum in PBS) for 1 h at room

temperature. Following that, the cells were also stained with above

antibodies and incubated at 4°C protected from light. After 1 h

incubation, the cells were washed twice and stained with 100 ng/ml

DAPI for 10 min at room temperature. The immunocytochemistry

staining utilized antibodies against E-cadherin (Santa Cruze

Biotechnology, sc-8426), Vimentin (Santa Cruze Biotechnology,

sc-373717), Snail (Genetex, GTX125918) and GAPDH (Santa Cruze

Biotechnology, sc-365062). The final observation of the samples was

conducted using a fluorescence imaging system (EVOS U5000;

Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All experiments were

performed in triplicate (n=3) to ensure reproducibility and

statistical significance.

Immunohistochemical analysis

For the immunohistochemical analysis, tissue

sections that were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded underwent

deparaffinization, followed by a rehydration process using a series

of ethanol solutions. Epitope retrieval was then carried out in

accordance with standard methodologies. The immunohistochemical

staining utilized antibodies against BIM (Cell Signaling

Technology, #2933s), Mcl-1 (Santa Cruze Biotechnology, sc-377487),

E-cadherin (Santa Cruze Biotechnology, sc-8426), and Snail

(Genetex, GTX125918). Post-staining, the samples were analyzed for

antibody expression using a laser-scanning microscope (Eclipse

TE300; Nikon).

TUNEL assay

The detection of apoptosis in pancreatic cancer

cells was carried out using TUNEL analysis, employing the In Situ

Apoptosis Detection Kit (Takara Bio Inc.), with the protocol

adhering to the manufacturer's instructions. In summary, the

procedure involved incubating sample slides with 50 µl of TUNEL

reaction mixture and TdT labeling reaction mix for a duration of 1

h at 37°C, ensuring the environment was dark. Following the

incubation, the slides were washed three times using

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The final observation of the

samples was conducted using a fluorescence imaging system (EVOS

U5000; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Wound healing assay

The AsPC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines were cultured

in 6-well plates until they reached full confluence. Subsequently,

the growth medium was substituted with serum-free media, and the

cells underwent a 72-h incubation period. Post-incubation, the cell

monolayers were mechanically disrupted to create a wound, followed

by the application of a test agent (rupatadine). An exact region of

the wound was imaged using phase-contrast microscopy prior to the

administration of these agents. This same region was imaged again

after a 72-h period. The area of the wound was quantitatively

assessed using image analysis techniques, both initially and after

the 72-h interval. The rate of wound closure was calculated based

on the change in wound area over time, using the formula: [(initial

wound area-final wound area)/initial wound area] ×100, to express

this change as a percentage. All experiments were performed in

triplicate (n=3) to ensure reproducibility and statistical

significance.

Animals study design

Our animal study design involved five-week-old male

BALB/c nude mice (Orient Bio). Our animal experiments were approved

by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the

Catholic University of Korea (approval No. CUMC-2022-0014-01) and

were conducted in accordance with institutional and national

guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. For the

xenograft pancreatic cancer model, 1×106 AsPC-1 cells

were subcutaneously injected into the mice. In the evaluation of

rupatadine's in vivo efficacy, mice were grouped randomly,

with each group containing five mice. After two weeks

post-implantation of the tumor model, the mice were treated with

rupatadine (3 mg/kg) administered intraperitoneally, three times a

week for three weeks. Twenty-one days after initial treatment, the

animals were euthanized, and the tumors were surgically removed for

subsequent analysis. Animals were euthanized using compressed

carbon dioxide (CO2) gas at a displacement rate of

30–70% of the chamber volume per minute for 2–3 min. Loss of

consciousness was confirmed by observing lack of response and faded

eye color, and death was verified by cessation of respiration,

cardiac arrest, and pupil dilation. Throughout the experiment,

animal health was monitored daily, and humane endpoints-such as

weight loss >20%, severe lethargy, or ulceration-were predefined

and strictly observed.

Regarding the establishment and monitoring of tumor

formation before initiating Rupatadine treatment, tumors were

allowed to reach a predetermined size, specifically a volume of 100

mm3, confirmed through visual inspection before the

commencement of drug administration. The endpoint for the study was

matched based on the time-point rather than the stage, ensuring

that all groups were assessed over the same duration post-treatment

initiation.

Rupatadine pharmacokinetics in mouse

plasma and tissues

Mice received an intravenous dose of 10 mg/kg

rupatadine. Plasma samples were collected at intervals from 5 to

360 min and processed by mixing with four volumes of acetonitrile,

followed by centrifugation. Tissue samples at 5 and 60 min were

prepared similarly. Rupatadine concentrations were measured using

high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Waters Arc

system, a C18 column, and a mobile phase of methanol and 0.3 M

sodium acetate (pH 4.4) at a 20:80 ratio, with a flow rate of 1

ml/min. The retention time for rupatadine was 5 min.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 11.0

(SPSS Inc.), with data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The

Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc test was used for

multiple-group comparisons, while the Mann-Whitney U test and

Student's t-test were applied for nonparametric and normally

distributed two-group comparisons, respectively. Statistical

significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

In vitro anticancer effects of

rupatadine

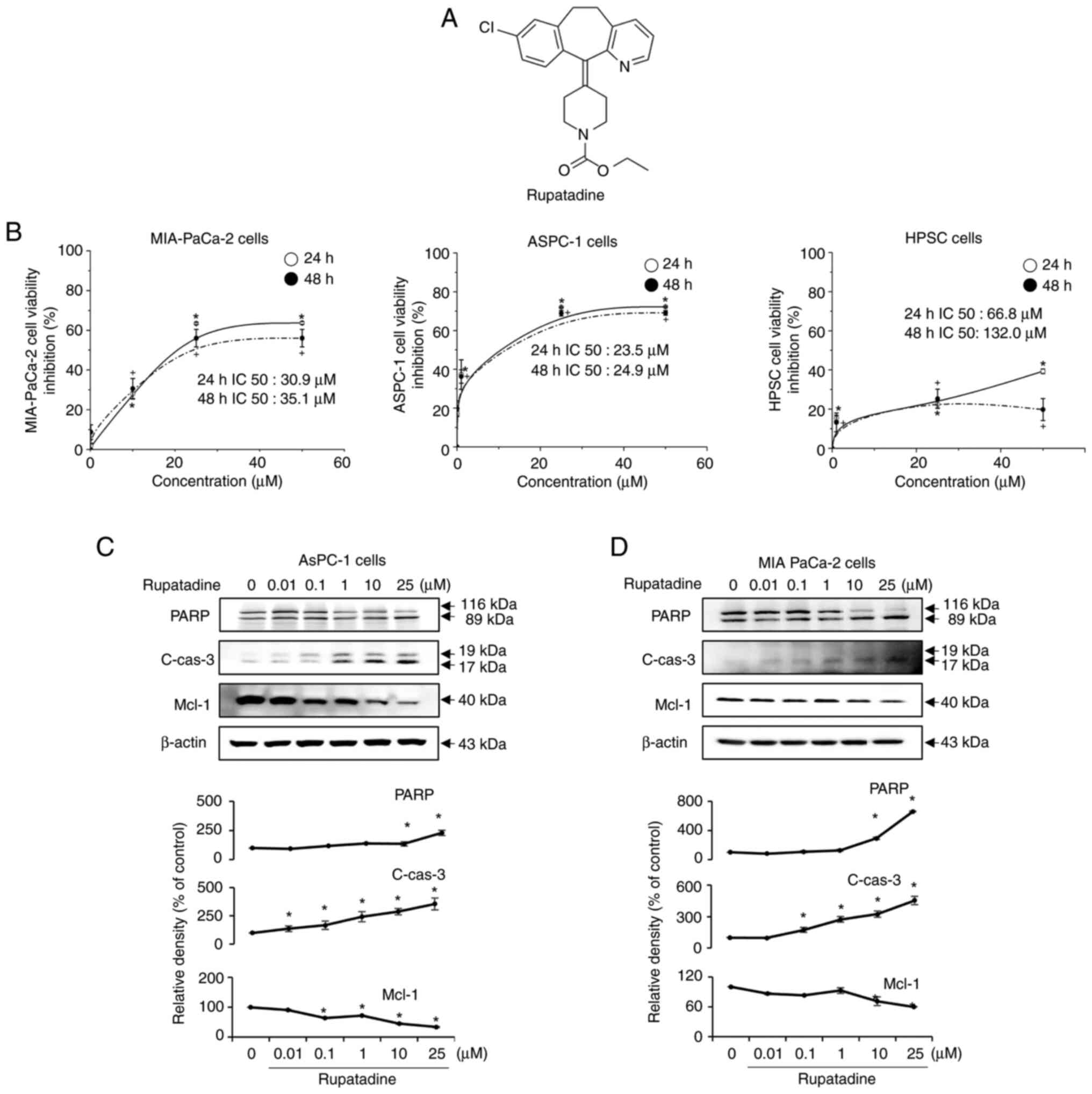

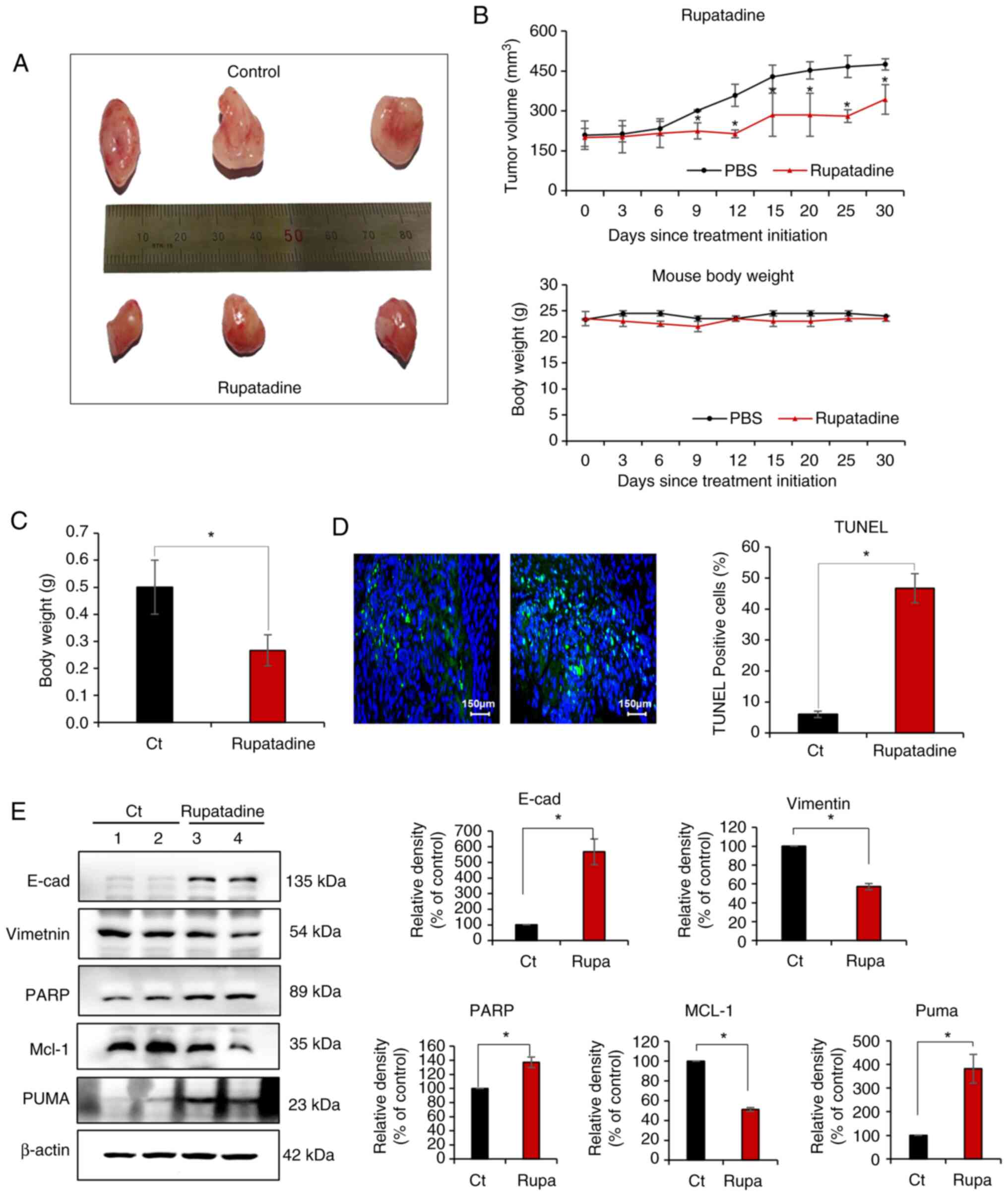

Rupatadine is a chemical compound characterized by a

cationic amphiphilic structure, consisting of a hydrophobic ring

system and a side chain with a cationic amine group (Fig. 1A). To further evaluate the

dose-dependent effects of rupatadine, dose-response curves were

generated for AsPC-1 and MIA-PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells, as

well as human pancreatic stellate cells (HPSC) (Fig. 1B). The IC50 values for AsPC-1 cells

were 23.5 µM (24 h) and 24.9 µM (48 h), while for MIA-PaCa-2 cells,

the IC50 values were 30.9 µM (24 h) and 35.1 µM (48 h). In the

MIA-PACA cell line, rupatadine displayed lower cell viability

compared to treatments with irinotecan (3.125–200 ng/ml),

5-fluorouracil (1–100 µM), and paclitaxel (1–10 nM) at both 24 and

48 h. This suggests that rupatadine may possess superior anticancer

effects relative to these well-established chemotherapeutic agents

(Fig. S1). In contrast,

rupatadine exhibited significantly lower cytotoxicity in human

pancreatic stellate cells (HPSC), with IC50 values of 66.8 µM at 24

h and 132.0 µM at 48 h, indicating a selectivity for pancreatic

cancer cells over normal pancreatic cells. Data are presented as

mean ± SD from three independent experiments. This data suggests

that rupatadine preferentially inhibits pancreatic cancer cells

while having a reduced effect on normal pancreatic cells.

| Figure 1.In vitro anticancer effects of

rupatadine on pancreatic cancer cell lines. (A) Chemical structure

of rupatadine. As a cationic amphiphilic drug, the structure of

rupatadine, comprising a hydrophobic ring and a cationic amine

group, facilitates its penetration through the plasma membrane. (B)

Dose-response curves comparing the effects of rupatadine on AsPC-1

and MIA-PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells with those on HPSC (bottom).

For the cancer cell lines, a dose-dependent decrease in viability

is observed with rupatadine concentrations from 0 to 50 µM, with

IC50 values of 23.5 µM (24 h) and 24.9 µM (48 h) for

AsPC-1 cells (top, left) and 30.9 µM (24 h) and 35.1 µM (48 h) for

MIA-PaCa-2 cells (top, right). By contrast, HPSCs (bottom) exhibit

significantly higher IC50 values of 66.8 µM (24 h) and

132.0 µM (48 h), indicating lower sensitivity to rupatadine. (C)

Induction of apoptosis in AsPC-1 cells. Western blot analysis shows

a dose-dependent increase in the levels of pro-apoptotic markers

PARP and cleaved caspase-3 and a reduction in the anti-apoptotic

marker Mcl-1 in AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cells following treatment

with rupatadine, ranging from 0 to 25 µM (P<0.05). (D) Induction

of apoptosis in MIA-PACA-2 cells. MIA-PACA-2 cells treated with

rupatadine showed increased pro-apoptotic markers and decreased

anti-apoptotic markers, similar to AsPC-1 cells, indicating

rupatadine's consistent pro-apoptotic effect (P<0.05). Relative

densities of individual markers had been quantified using Image J

software and then were normalized to that of β-actin in each group.

Values are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

*P<0.05 vs. the control after 24 h; +P<0.05 vs.

the control after 48 h. HPSC, human pancreatic stellate cells;

Mcl-1, Myeloid cell leukemia-1; c-, cleaved; cas3, caspase 3. |

Following the treatment with rupatadine, a

concentration-dependent (0–25 µM) increase in the pro-apoptotic

markers, PARP and cleaved caspase-3, and a decrease in the

anti-apoptotic marker, Mcl-1, were observed in AsPC-1 pancreatic

cancer cells, as evidenced by Western blot analysis (P<0.05)

(Fig. 1C). A similar trend was

noted in MIA PaCa-2 cells, demonstrating the compound's consistent

apoptotic induction across different cell lines (P<0.05)

(Fig. 1D). Data are presented as

mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Additionally, Western

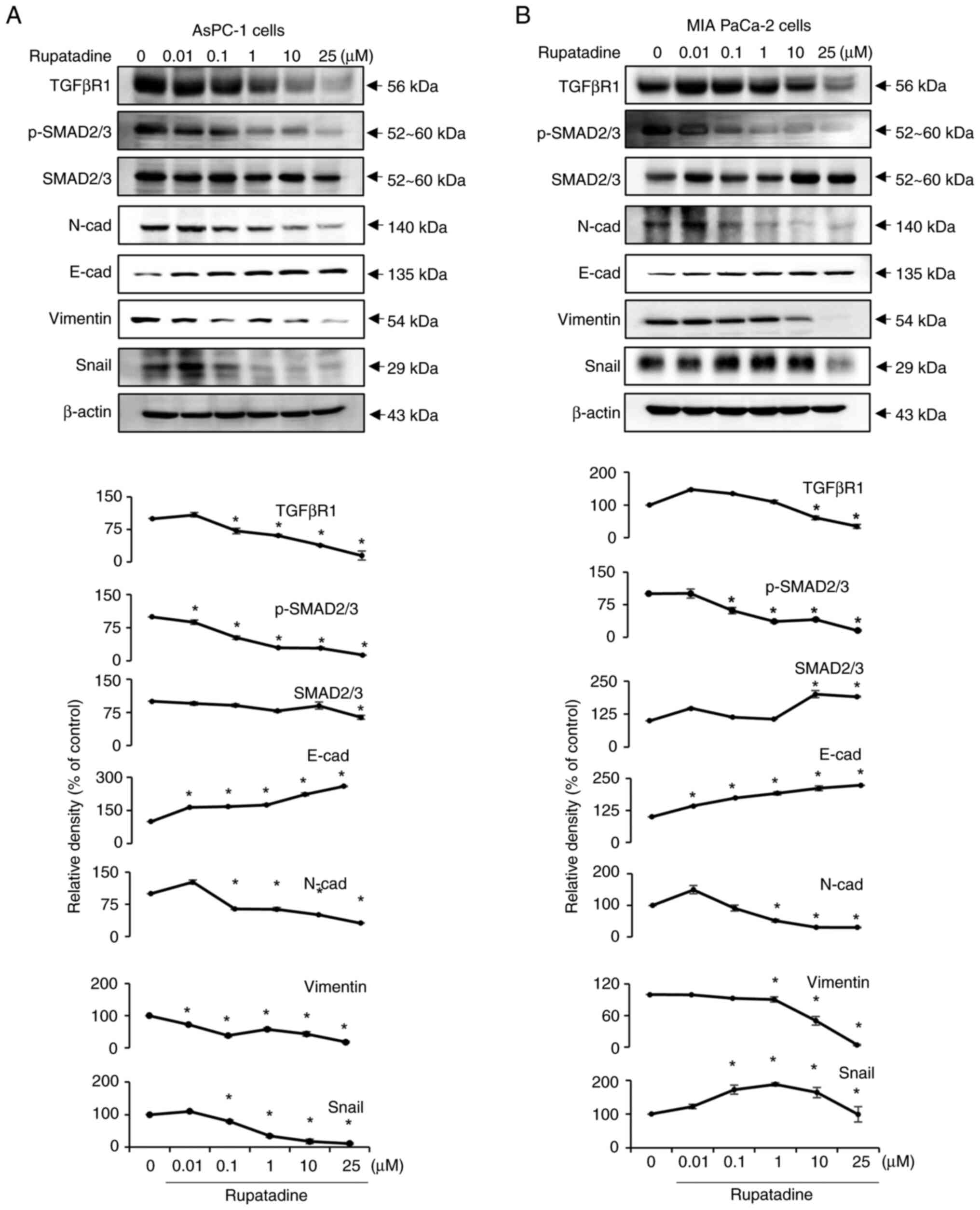

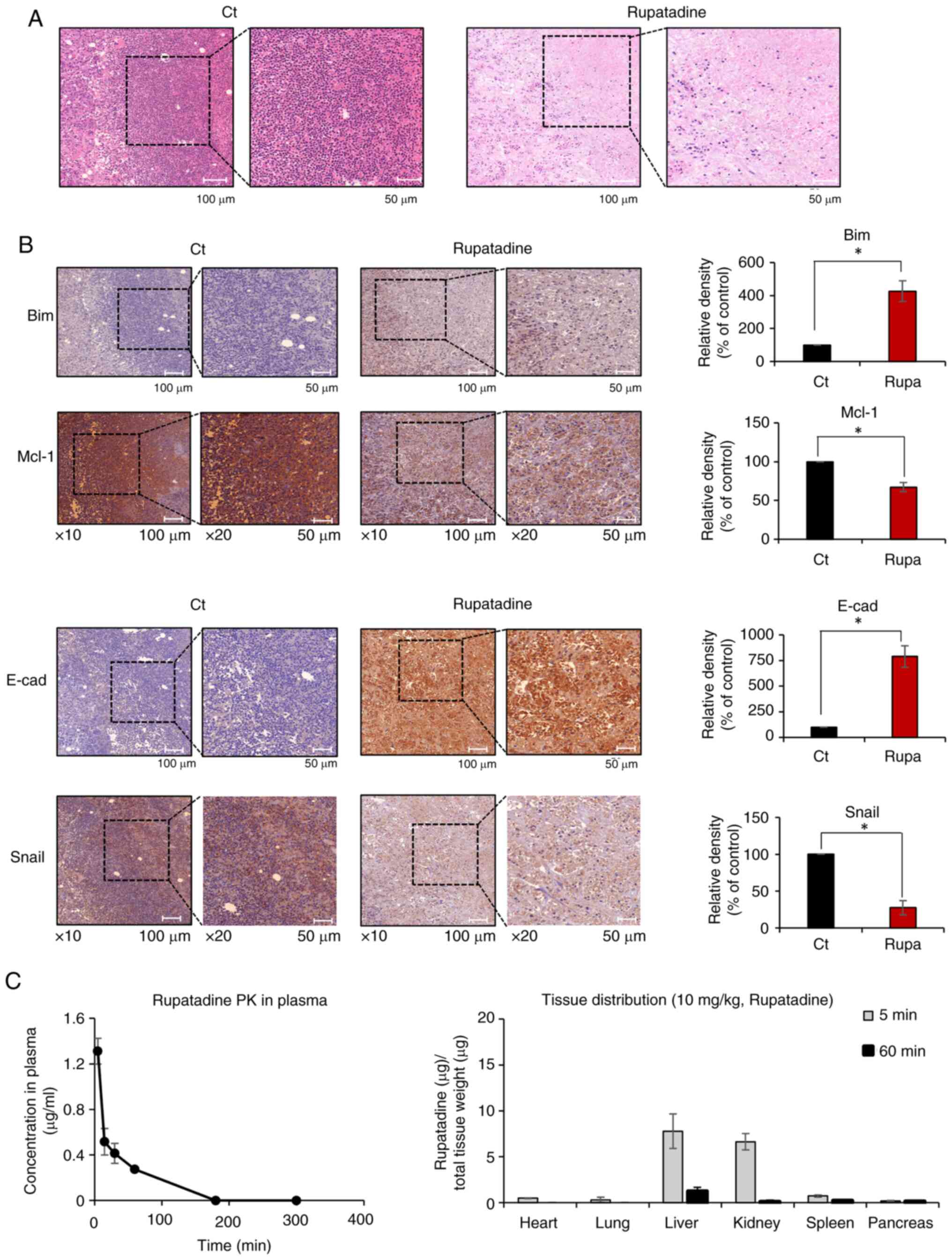

blot analysis was employed to assess the impact of rupatadine on

TGF-β signaling and EMT markers. The results indicate that

Rupatadine significantly suppresses the expression of TGFβRI and

diminishes the phosphorylated to total SMAD2/3 ratio in a

dose-dependent manner in AsPC-1 cells (P<0.05) (Fig. 2A), implicating the inhibition of

the TGFβ1 signaling pathway at the receptor level. The analysis

further revealed that Rupatadine upregulated the epithelial marker

E-cadherin while downregulating mesenchymal markers N-cadherin,

Vimentin, and Snail, highlighting its role in thwarting EMT

(P<0.05). Parallel results in MIA PaCa-2 cells reinforced

rupatadine's efficacy in targeting both the TGFβ signaling pathway

and EMT (Fig. 2B).

| Figure 2.Effects of rupatadine on TGF-β

signaling and EMT marker regulation. (A) In AsPC-1 pancreatic

cancer cells, rupatadine exhibits a dose-dependent decrease in

TGF-βRI expression and reduces the ratio of p-SMAD2/3 to total

SMAD2/3, suggesting an inhibition of the TGFβ1 pathway. (B) In MIA

PaCa-2 cells, analogous dose-dependent effects of rupatadine are

observed, consistent with findings in AsPC-1 cells, further

validating the drug's role in modulating TGF-β signaling and EMT.

Relative densities of individual markers had been quantified using

Image J software and then were normalized to that of β-actin in

each group. Values are presented as mean ± SD of three independent

experiments. *P<0.05 vs. the control. EMT,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition; TGF-βRI, transforming growth

factor β receptor type I; p-, phosphorylated; N-cad, N-cadherin;

E-cad, E-cadherin. |

Effects of rupatadine on migration of

pancreatic cancer cells

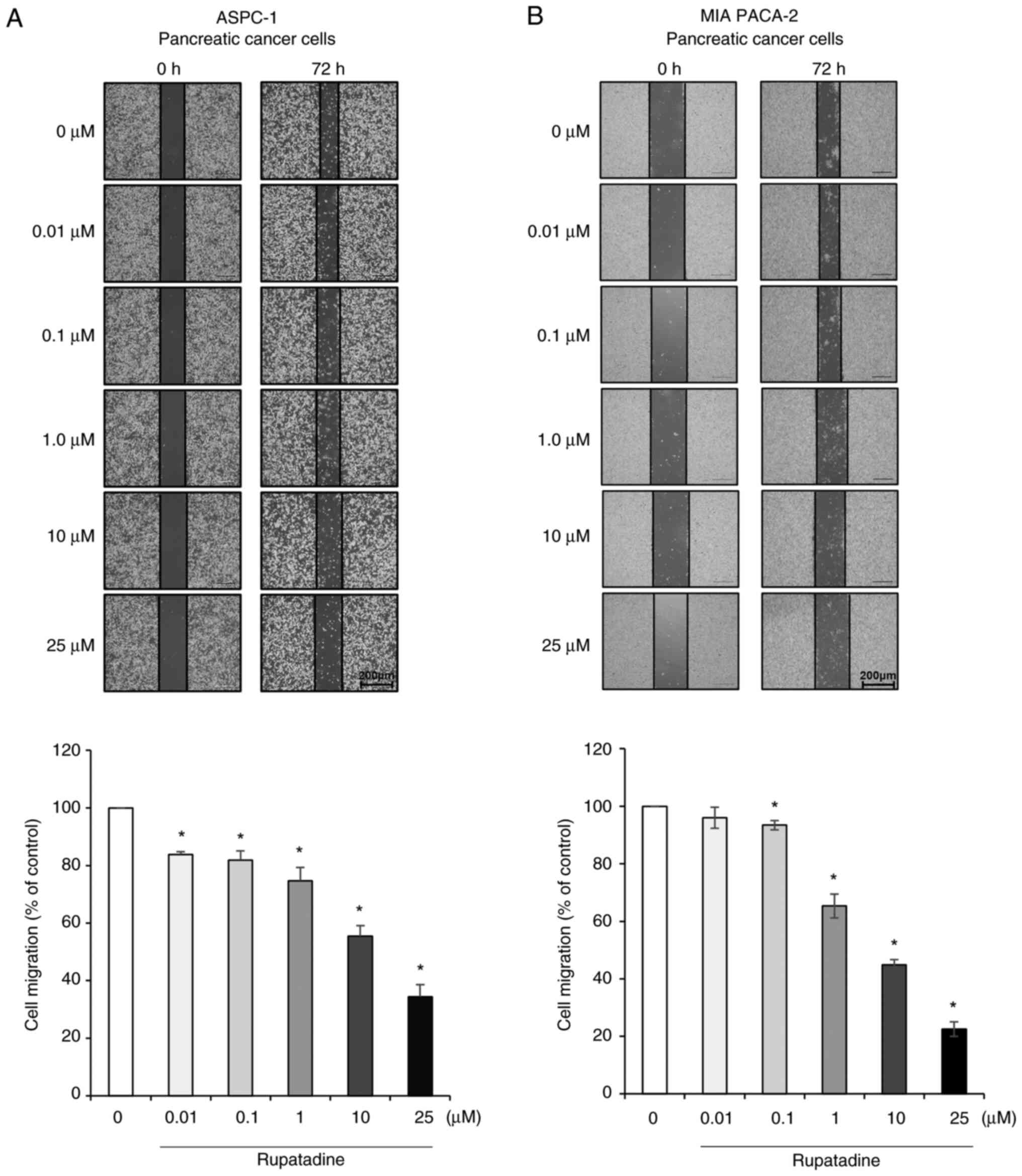

The impact of rupatadine on the migration of

pancreatic cancer cells was evaluated using a wound healing assay.

After creating a scratch in a confluent monolayer of AsPC-1 cells,

the closure of the wound was monitored in response to increasing

concentrations of rupatadine (0.01–25 µM). Increased concentrations

of rupatadine, specifically at 25 µM, were correlated with a

significant expansion of the scratch area, illustrating a

dose-dependent suppression of cell migration in AsPC-1 cells

(Fig. 3A). An analogous effect was

recorded in MIA PaCa-2 cells at the 25 µM concentration of

rupatadine (Fig. 3B). Data are

presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Effects of rupatadine on EMT of

pancreatic cancer cells

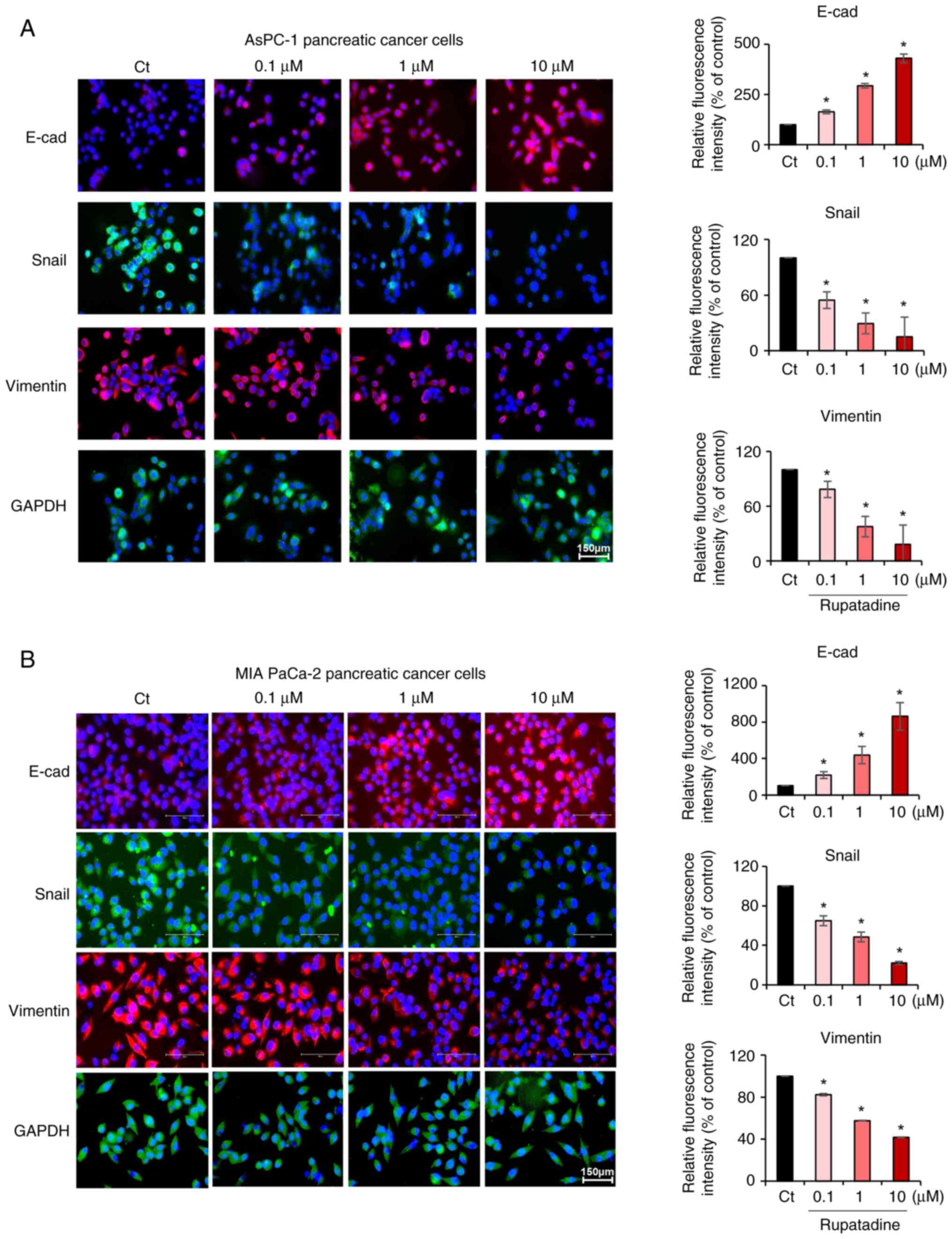

The influence of rupatadine on EMT in AsPC-1

pancreatic cancer cells was investigated through immunofluorescence

analysis of EMT markers following treatment with rupatadine.

Increasing the concentration of rupatadine (0.1–10 µM) resulted in

a concentration-dependent increase in the immunofluorescence of the

epithelial marker E-cadherin, and a decrease in the

immunofluorescence of mesenchymal markers Snail and Vimentin

(P<0.05) (Fig. 4A). Similar

effects were observed in MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells, with

rupatadine treatment leading to an increased immunofluorescence in

E-cadherin and a decreased immunofluorescence in Snail and Vimentin

(P<0.05) (Fig. 4B). Data are

presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Anticancer efficacy of rupatadine in a

pancreatic cancer xenograft mouse model

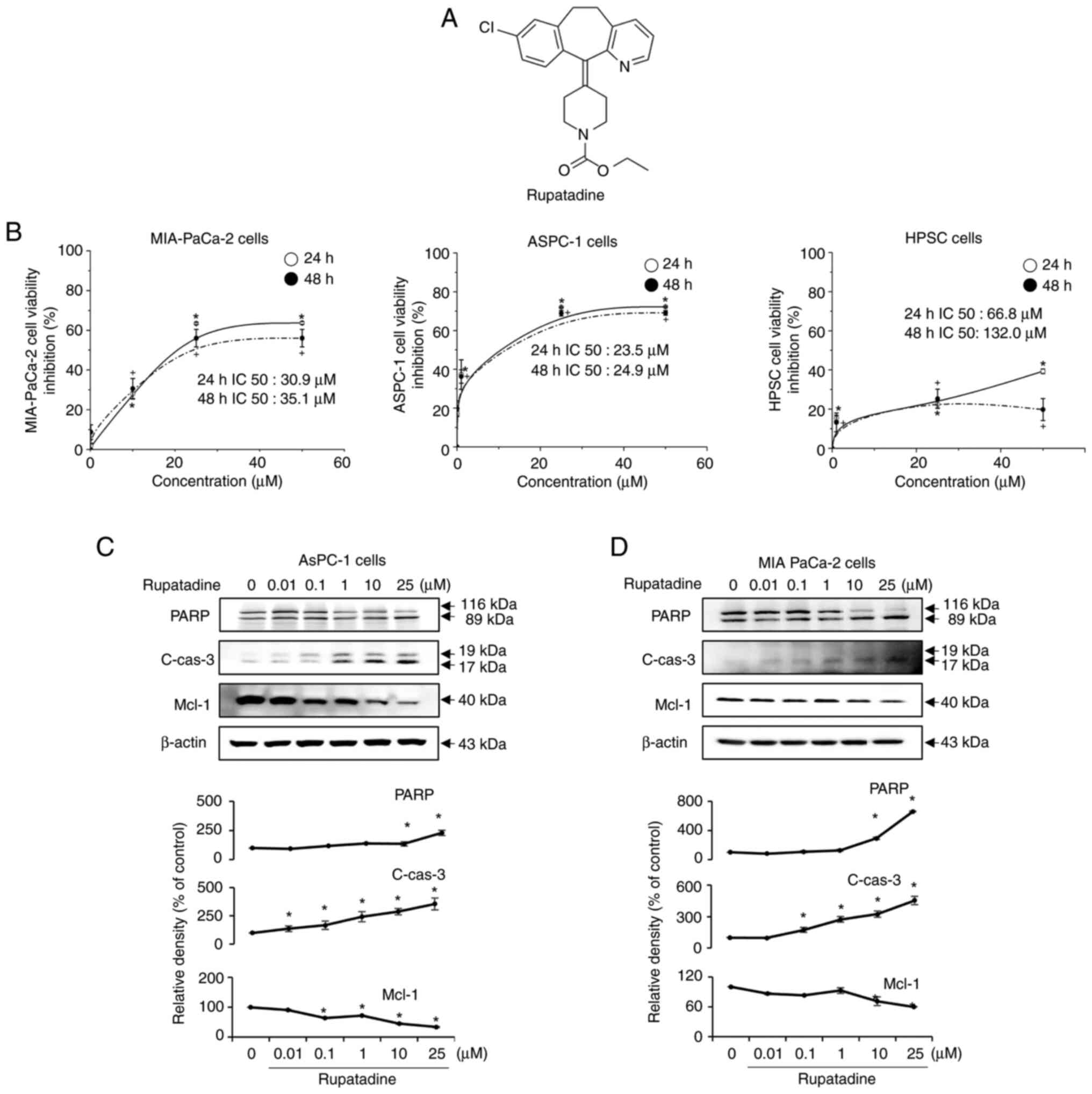

The in vivo xenograft mouse model of

pancreatic cancer was established by direct injection of AsPC-1

cells (1×106 cells) into the pancreas of BALB/c nude

mice after laparotomy under anesthesia. Two weeks later, the mice

were treated with rupatadine (3 mg/kg) administered

intraperitoneally, three times a week for three weeks. On 21 days

after initial treatment, the animals were euthanized, and the

tumors were surgically removed for subsequent analysis. Fig. 5A presents a representative

illustration depicting the difference in tumor size between the

control group and the rupatadine-treated group on 21 days after

initial treatment. Tumors in the control group weighed between 0.4

and 0.6 g, whereas those treated with Rupatadine weighed between

0.2 and 0.3 g. To assess the effects of rupatadine on tumor

progression over time, tumor volume was measured at multiple time

points following treatment initiation. The rupatadine-treated group

exhibited a significantly slower tumor growth rate compared to the

control group (Fig. 5B top). After

21 days of treatment, the average tumor volume in the control group

continued to increase, whereas the tumor volume in the

rupatadine-treated group showed a marked reduction (Fig. 5B top). In contrast, no significant

differences in body weight were observed between the two groups

throughout the experimental period, indicating that rupatadine

treatment did not cause notable systemic toxicity (Fig. 5B bottom). Consistently, tumor

weight analysis performed on day 21 after the initial treatment

revealed a significant reduction in the rupatadine-treated group

compared to the control group (P<0.05), further supporting its

tumor-suppressive effects (Fig.

5C). Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent

experiments.

Subsequently, a TUNEL assay was conducted to

quantify apoptosis in the excised tumors from the

rupatadine-treated groups. The results of the TUNEL assay revealed

a significantly higher apoptosis index in the tumors treated with

rupatadine compared to those in the control groups (P<0.05)

(Fig. 5D). Western blot analysis

was utilized to assess the differential expression of markers

associated with EMT and apoptosis in the excised tumor tissues

(Fig. 5E). In the group treated

with rupatadine, a notable upregulation of the epithelial marker

E-cadherin was observed, in contrast to the control group.

Conversely, the mesenchymal marker vimentin was significantly

downregulated (P<0.05) in the rupatadine-treated tumors.

Furthermore, the rupatadine-treated tumors demonstrated a

significant elevation in the levels of pro-apoptotic markers, PARP

and PUMA, while the expression of the anti-apoptotic marker Mcl-1

was markedly reduced (P<0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD

from three independent experiments.

Effects of rupatadine on histological

changes, apoptosis, EMT, and pharmacokinetics in a pancreatic

cancer xenograft mouse model

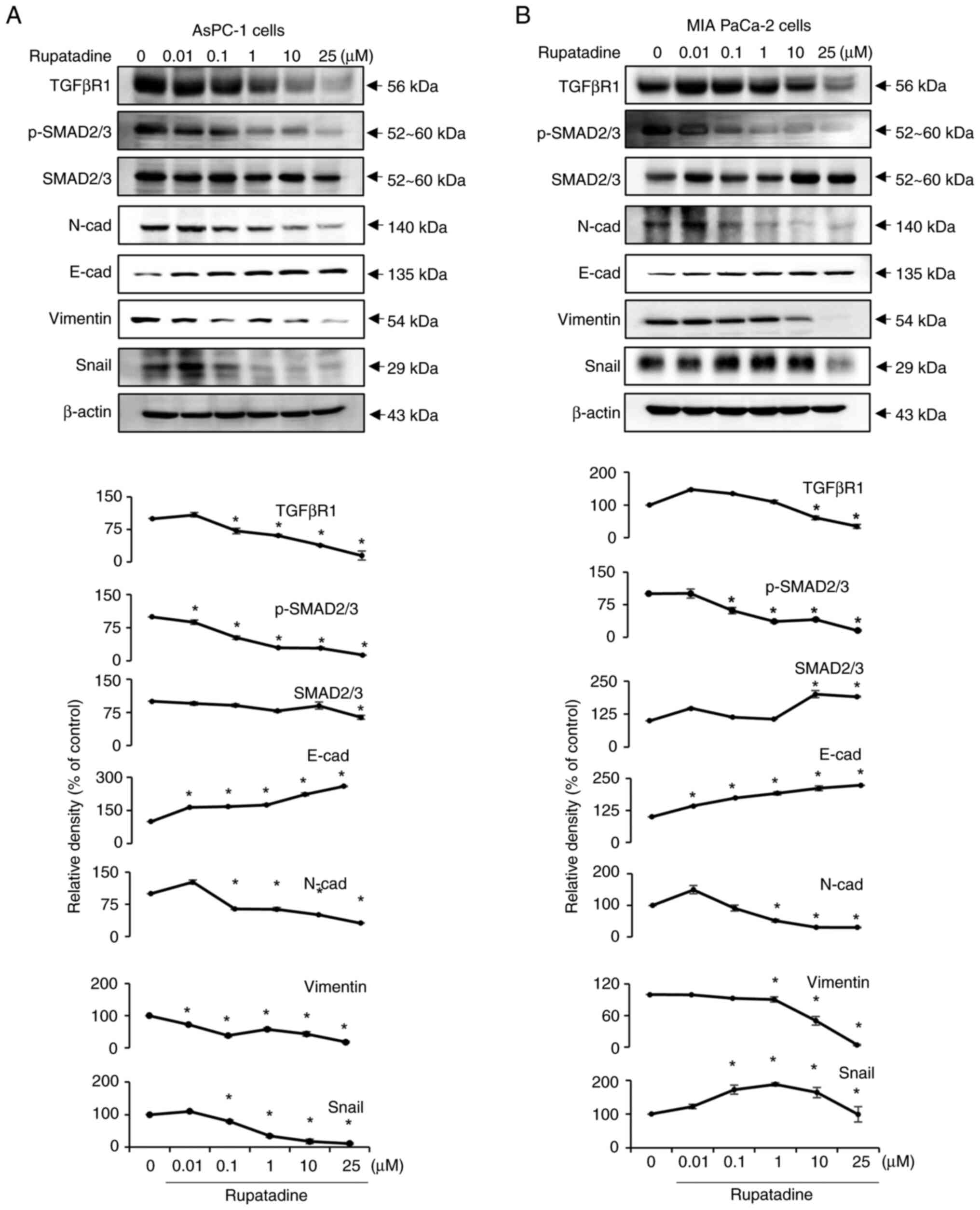

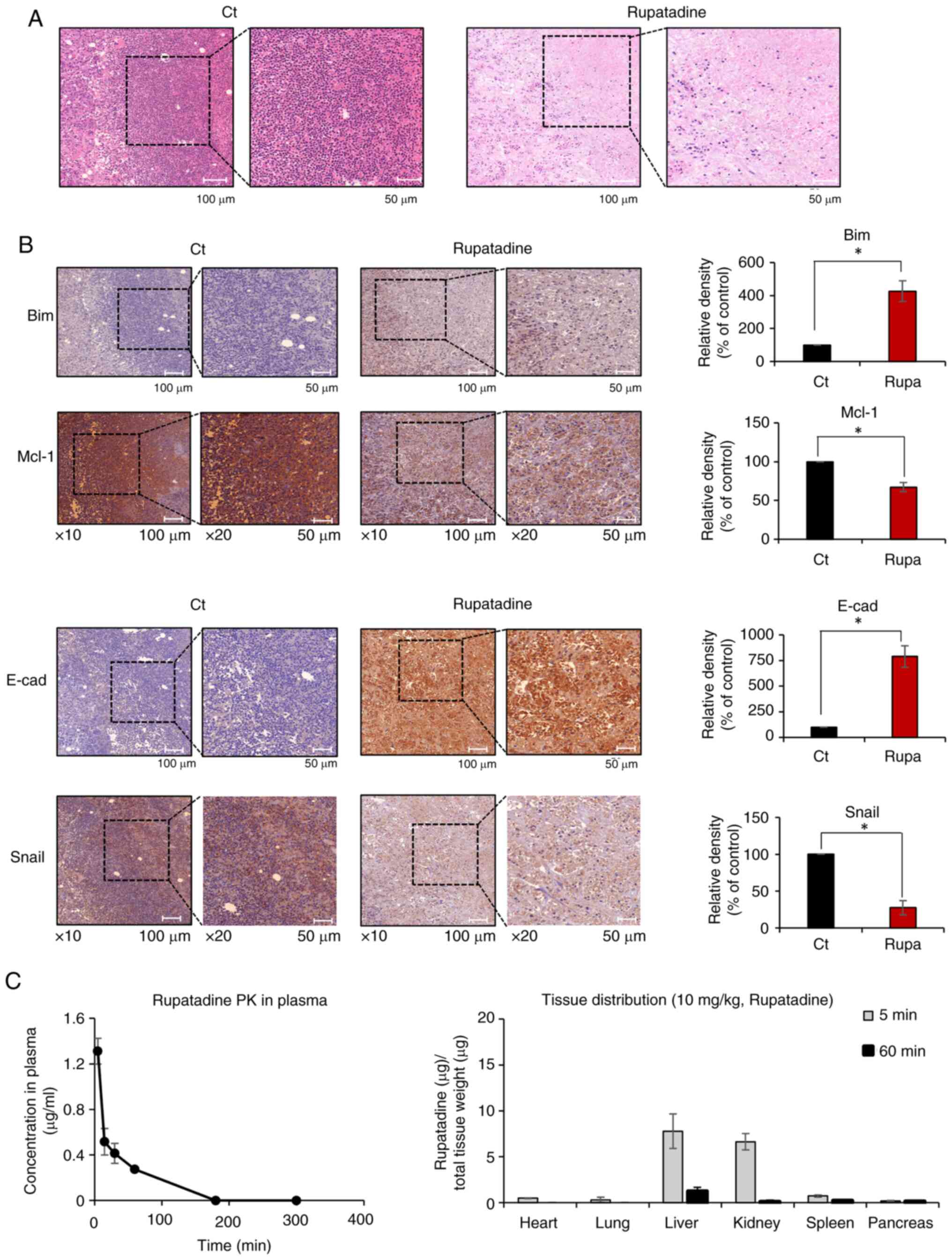

Tumor tissues derived from a mouse xenograft model

of pancreatic cancer underwent Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)

staining for comparative histological examination. In the

rupatadine-treated group, a notable reduction in tumor cell density

was observed (Fig. 6A). This was

followed by immunohistochemical staining of the excised tumor

tissues from each experimental group. Analysis of the stained

tissues revealed that, in the rupatadine-treated group, there was a

significant increase in the percentage of immunoreactive areas for

a pro-apoptotic marker, BIM, compared to the control group.

Conversely, the expression of Mcl-1, an anti-apoptotic marker, was

significantly decreased (P<0.05) (Fig. 6B top). Furthermore, the

rupatadine-treated group exhibited a significant increase in the

percentage of immunoreactive areas for the epithelial marker

E-cadherin, alongside a significant decrease in Snail, a

mesenchymal marker (P<0.05) (Fig.

6B bottom). Overall, these findings suggest that rupatadine

treatment can attenuate the EMT process and enhance apoptosis in

pancreatic cancer tissues within this mouse xenograft model.

| Figure 6.Impact of rupatadine on histological

changes in a pancreatic cancer xenograft mouse model. (A) H&E

staining of excised tumor tissues, demonstrating a notable

reduction in tumor cell density in the rupatadine-treated group.

(B) Immunohistochemical analysis for the markers of apoptosis and

EMT. Rupatadine-treated group exhibited increased immunoreactivity

for the pro-apoptotic marker BIM and decreased expression of the

anti-apoptotic marker Mcl-1. In addition, the rupatadine-treated

group exhibited decreased immunoreactivity for the epithelial

marker E-cadherin and decreased expression of the mesenchymal

marker Snail. For 10× magnification, the scale bar is 100 µm; for

20× magnification, the scale bar is 50 µm. (C) Pharmacokinetic and

tissue distribution analysis of rupatadine in vivo. (Left)

Plasma concentration-time curve of rupatadine following intravenous

administration (10 mg/kg) in mice. Rupatadine was rapidly cleared

from plasma, with undetectable levels beyond 180 min. (Right)

Tissue distribution of rupatadine at 5 and 60 min post-injection,

showing predominant accumulation in the liver and kidneys at early

time points, with minimal retention after 60 min. Values are

presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Percentages of immunoreactive areas were measured using Image J

(National Institute of Health) and expressed as relative values to

those in control tissues. *P<0.05 vs. the control. H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin staining; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal

transition; BIM, Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death; Ct,

control; Mcl-1, Myeloid cell leukemia-1; E-cad, E-cadherin; Rupa,

Rupatadine. |

To further investigate the in vivo

pharmacokinetics of rupatadine, we analyzed its plasma

concentration and tissue distribution following intravenous

injection (10 mg/kg) in mice. Plasma concentration-time profiling

demonstrated a rapid decline in rupatadine levels, with detectable

concentrations at 5, 15, 30, and 60 min, but no detectable levels

after 180 min, indicating fast clearance from circulation (Fig. 6C, left). Tissue distribution

analysis revealed that rupatadine primarily accumulated in the

liver and kidneys within 5 min post-injection but was largely

undetectable in these tissues by 60 min, suggesting rapid

metabolism and excretion (Fig. 6C,

right). These findings provide essential information regarding

rupatadine's pharmacokinetic profile and tissue clearance dynamics,

which are critical for understanding its potential as an anticancer

agent.

Discussion

Rupatadine, known for its role as a selective

histamine H1 receptor and platelet-activating factor antagonist in

treating allergic rhinitis, has gained attention for its anticancer

potential due to its capacity to induce lysosomal membrane

permeabilization. This research explores the anticancer properties

of rupatadine within in vitro and in vivo pancreatic

cancer models. Rupatadine demonstrated a concentration-dependent

reduction in the cell viability of both AsPC-1 and MIA PaCa-2

pancreatic cells, across a range of concentrations (0.001–50 µM).

In an in vivo pancreatic cancer xenograft model, intravenous

administration of rupatadine led to a significant tumor weight

reduction after 35 days of treatment. Further analysis of excised

tumor tissues from the mouse model corroborated the in vitro

findings, with rupatadine inhibiting EMT and promoting apoptosis in

tumor cells. Specifically, it increased E-cadherin levels while

decreasing Vimentin and Snail expressions, indicating a suppression

of EMT. Concurrently, it augmented the expression of the

pro-apoptotic marker PARP and reduced the anti-apoptotic marker

Mcl-1, suggesting an enhancement of apoptotic pathways.

Collectively, these findings underscore the potential of rupatadine

as a therapeutic agent in pancreatic cancer due to its ability to

concurrently inhibit EMT and activate apoptotic pathways in both

in vitro and in vivo models of pancreatic cancer.

Rupatadine, widely used as an antagonist for

histamine H1 receptors and platelet-activating factors in allergic

rhinitis treatment, has garnered attention for its potential

anticancer effects, particularly in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

and ovarian cancer (7,9). Specifically, research has shown that

rupatadine affects AML cells at concentrations marginally higher

than those used for alleviating allergic symptoms (9). In the study, rupatadine showed no

substantial impact on the viability of normal blood cells, such as

T cells, B cells, and myeloid cells, with the exception of a noted

decrease in the myeloid cell population. Moreover, the treatment

preserved the clonogenic capacity of healthy hematopoietic

progenitor/stem cells, indicating a selective action against cancer

cells while sparing healthy cells. Additionally, in vivo

experiments demonstrated that rupatadine reduced the regeneration

potential of AML cells when transplanted into immunocompromised

mice, further supporting its potential as an anticancer agent.

These findings highlight the potential of rupatadine as a selective

treatment option for AML, revealing a new avenue for the use of

this antihistamine beyond its traditional role in allergy

management.

This study offers preliminary insights into

rupatadine's ability to inhibit EMT, an effect not widely

recognized in previous research. The inhibitory effect of

rupatadine on EMT can reasonably be ascribed to its capacity to

induce lysosomal membrane permeabilization and mitochondrial

damage. This can lead to increased cellular stress, potentially

disrupting EMT-related signaling pathways and modulating

transcription factors crucial for EMT, such as Snail, Slug, and

Twist. Additionally, rupatadine's impact on cellular stress and

mitochondrial dysfunction could reduce the metastatic potential of

cancer cells and alter autophagic flux, further contributing to the

inhibition of EMT (9). These

combined effects, stemming from rupatadine's disruption of

lysosomal and mitochondrial functions, likely contribute to its

efficacy in inhibiting EMT processes in pancreatic cancer

cells.

This study confirms that rupatadine's anticancer

efficacy is primarily derived from its dual action of inhibiting

EMT and promoting apoptosis. In addition, this study has shown that

Rupatadine can have anticancer effect by inhibiting the TGFβ1

signaling pathway which promotes cancer cell invasion,

angiogenesis, and immune evasion within the tumor microenvironment,

facilitating tumor progression and metastasis. The inhibitory

effects of Rupatadine on the TGF-β signaling pathway have been

demonstrated in numerous previous studies (10–13).

Especially, Didamoony et al (11) delineates that Rupatadine mediates

its anticancer efficacy through the inhibition of the TGF-β1

pathway, potentially by modulating associated pathways such as PAF,

NF-κB, and p65. Furthermore, Rupatadine's anticancer effects can be

partly linked to its role in causing mitochondrial and lysosomal

damage (9). As a cationic

amphiphilic drug, Rupatadine can easily enter cells and accumulate

in lysosomes, the cell's waste disposal system. This leads to the

disruption of the lysosomal membrane, releasing enzymes that

trigger cell death.

Although the AsPC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines used

in this study were obtained from an authenticated source,

additional in-house authentication and mycoplasma testing were not

performed prior to the experiments. While the passage numbers were

kept relatively low (passage 11 for AsPC-1 and passage 13 for MIA

PaCa-2), we acknowledge that prolonged culture and high passage

numbers may contribute to genetic and phenotypic variability, which

could influence experimental outcomes. Future studies should

consider regular authentication to ensure reproducibility and

minimize variability associated with cell culture conditions.

In conclusion, this study highlights rupatadine's

anticancer effects in pancreatic cancer models. The in vitro

results demonstrated rupatadine's capacity to suppress EMT and

enhance apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. In a pancreatic

cancer xenograft mouse model, intravenous administration of

rupatadine led to a significant tumor weight reduction. Further

analysis of the excised tumor tissue from this model reinforced the

observation that rupatadine's anticancer efficacy largely stems

from its dual action in inhibiting EMT and facilitating apoptosis.

Future studies are needed to elucidate the precise mechanisms

underlying these effects. In addition, expanding the panel of

pancreatic cancer cell lines in future experiments will help

validate the generalizability of our findings and further support

the clinical relevance of rupatadine. Moreover, while the present

study focused on monotherapy, future investigations will evaluate

the combinatorial potential of rupatadine with established

chemotherapeutic agents and targeted therapies to better reflect

clinical treatment strategies. Overall, rupatadine can be

considered as a promising candidate for pancreatic cancer therapy,

offering a unique mechanism of action that could synergize

effectively with existing treatment modalities in a combination

therapy approach.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Jeong-Yeon Seo

(Translational Research Team, Surginex Co., Ltd., Seoul, South

Korea) for manuscript processing and Ms Jennifer Lee (Translational

Research Team, Surginex Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea) for their

contributions to the illustrations.

Funding

This work was supported by the financial support of the Catholic

Medical Center Research Foundation made in the program year of

2021.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SJK conceptualized the study and was project

administrator. BJC analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the

original draft. BJC, HJC, DL, JHP and THH performed the animal

experiments. HJJ, GHJ and OHK performed the in vitro

experiments. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. SJK and BJC confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Our animal experiments were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Catholic

University of Korea (approval no. CUMC-2022-0014-01) and were

conducted in accordance with institutional and national guidelines

for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jiang Z, Zheng X, Li M and Liu M:

Improving the prognosis of pancreatic cancer: Insights from

epidemiology, genomic alterations, and therapeutic challenges.

Front Med. 17:1135–1169. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rahib L, Wehner MR, Matrisian LM and Nead

KT: Estimated projection of US cancer incidence and death to 2040.

JAMA Netw Open. 4:e2147082021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:7–33.

2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mizrahi JD, Surana R, Valle JW and Shroff

RT: Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 395:2008–2020. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Park W, Chawla A and O'Reilly EM:

Pancreatic cancer: A review. JAMA. 326:851–862. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Awais N, Satnarine T, Ahmed A, Haq A,

Patel D, Hernandez GN, Seffah KD, Zaman MA and Khan S: A systematic

review of chemotherapeutic regimens used in pancreatic cancer.

Cureus. 15:e466302023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Deuster E, Hysenaj I, Kahaly M, Schmoeckel

E, Mayr D, Beyer S, Kolben T, Hester A, Kraus F, Chelariu-Raicu A,

et al: The platelet-activating factor receptor's association with

the outcome of ovarian cancer patients and its experimental

inhibition by rupatadine. Cells. 10:23372021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Faustino-Rocha AI, Ferreira R, Gama A,

Oliveira PA and Ginja M: Antihistamines as promising drugs in

cancer therapy. Life Sci. 172:27–41. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cornet-Masana JM, Banus-Mulet A, Carbo JM,

Torrente MA, Guijarro F, Cuesta-Casanovas L, Esteve J and Risueno

RM: Dual lysosomal-mitochondrial targeting by antihistamines to

eradicate leukaemic cells. EBioMedicine. 47:221–234. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ahmed LA, Mohamed AF, Abd El-Haleim EA and

El-Tanbouly DM: Boosting Akt pathway by rupatadine modulates

Th17/Tregs balance for attenuation of isoproterenol-induced heart

failure in rats. Front Pharmacol. 12:6511502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Didamoony MA, Atwa AM and Ahmed LA: A

novel mechanistic approach for the anti-fibrotic potential of

rupatadine in rat liver via amendment of PAF/NF-kB p65/TGF-beta1

and hedgehog/HIF-1alpha/VEGF trajectories. Inflammopharmacology.

31:845–858. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Didamoony MA, Atwa AM and Ahmed LA:

Modulatory effect of rupatadine on mesenchymal stem cell-derived

exosomes in hepatic fibrosis in rats: A potential role for

miR-200a. Life Sci. 324:1217102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lv XX, Wang XX, Li K, Wang ZY, Li Z, Lv Q,

Fu XM and Hu ZW: Rupatadine protects against pulmonary fibrosis by

attenuating PAF-mediated senescence in rodents. PLoS One.

8:e686312013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yuan W, Fang W, Zhang R, Lyu H, Xiao S,

Guo D, Ali DW, Michalak M, Chen XZ, Zhou C, et al: Therapeutic

strategies targeting AMPK-dependent autophagy in cancer cells.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1870:1195372023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Paunovic V, Kosic M, Misirkic-Marjanovic

M, Trajkovic V and Harhaji-Trajkovic L: Dual targeting of tumor

cell energy metabolism and lysosomes as an anticancer strategy.

Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 1868:1189442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Debnath J, Gammoh N and Ryan KM: Autophagy

and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

24:560–575. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bhagya N and Chandrashekar KR: Liposome

encapsulated anticancer drugs on autophagy in cancer cells -

Current and future perspective. Int J Pharm. 642:1231052023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|