Introduction

Esophageal carcinoma is a prevalent malignant tumor

originating from the esophageal mucosa, with varying global

incidence in different regions. Increased incidences of esophageal

carcinoma were reported in developing countries, particularly in

the low-middle Social Demographic Index (SDI) region, where

incident cases surged by 105.73% (1), which may be attributed to regional

cultures, dietary patterns and other factors (2,3). In

China, the main histologic type of esophageal carcinoma is

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Contributors to ESCC

include smoking, alcohol intake (4,5),

poor diet, chronic esophagitis, genetic mutations (6) and viral infections (7). Treatment strategies for ESCC include

surgical resection, endoscopic therapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy,

targeted therapy and immunotherapy (8–10).

Despite improvements in treatment strategies, the 5-year survival

rate of patients with ESCC is 18% (11), warranting exploration of the

molecular pathogenesis of ESCC to find new therapeutic

strategies.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) is a state of

cellular stress caused by ER dysfunction and abnormal protein

accumulation, which triggers an adaptive program response known as

the unfolded protein response (UPR). In response to UPR, three

transmembrane sensors, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α [IRE1α; also

known as endoplasmic reticulum to nucleus signaling 1 (ERN1)],

protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase [PERK;

also known as eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha

kinase 3 (EIF2AK3)] and activating transcription factor (ATF) 6 are

activated by dissociating with the molecular chaperone

glucose-regulated protein 78. Among them, IRE1α catalyzes the

shearing of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA, thus resulting in

translation of active transcription factors called XBP1s. PERK

phosphorylates its catalytic substrate, eIF2α through

autophosphorylation, and then stimulates the production of ATF4,

which subsequently activates CHOP to initiate cell death, including

apoptosis. ATF6 translocates to the golgi apparatus, where it is

cleaved by sphingosine-1-phosphate and site-2 protease to release

amino acid fragments with transcriptional activity called ATF6f

(12). ATF4, XBP1s and ATF6f

regulate transcription of a large range of target genes that

participate in the UPR. In tumors, the biological effects of ERS

are two-fold, the intensity of stress and different cell types will

induce mRNA transcription and promote tumor cell proliferation

(13), migration (14), autophagy (15–17)

and apoptosis (18–20). However, the mechanism of ERS in

ESCC is still not well clarified.

To explore the occurrence and mechanism of ERS in

ESCC, RNA sequencing was carried out on the in vitro ESCC

cell model of ERS and focused on the role of C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand (CXCL) 8, also known as IL-8. CXCL8, is a cytokine and

chemokine that belongs to the CXC chemokine family and is a small

molecule protein produced by a variety of cells. CXCL8 carries out

an important role in inflammation, tumor and immune response

(21). CXCL8 exerts biological

effects by binding to its chemokine receptors (CXCRs) 1 and 2,

among which CXCR1 mainly binds to CXCL8, while CXCR2 also binds to

CXCL1, 2, 3, 5 and 7 (22).

Increased CXCL8 expression is associated with poor prognosis in a

variety of tumors, including breast, colon and lung cancer

(23–25). Furthermore, elevated CXCL8

expression has been associated with resistance to chemotherapy and

immunotherapy in breast cancer, gastric cancer, lung adenocarcinoma

and hepatocellular carcinoma (26–29).

The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis promotes migration, proliferation, invasion

and survival of tumor cells (30).

CXCL8 and CXCR1/2 are reported to be highly expressed in ESCC

tissues and are associated with factors and prognosis (31,32).

In particular, CXCL8 promotes migration and invasion of ESCC cells

through phosphorylation of AKT and ERK1/2 (32). Nevertheless, the role of CXCL8 in

ERS and the potential downstream mechanisms promoting ESCC

progression need to be further investigated.

The present study investigated the mechanisms

underlying CXCL8 upregulation during ERS and its tumor-promoting

effects in ESCC, in order to provide a new strategy for ESCC

treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Human esophageal cancer cell lines (KYSE-150,

KYSE-170 and TE-1) and the human normal esophageal epithelial cell

line (HEEC) were purchased from the China Center for Type Culture

Collection and cultured in RPMI1640 medium (cat. no. 11879020;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; cat. no. A5670201; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Cells were maintained under standard culture conditions

(37°C and 5% CO2) in culture medium. For thapsigargin

(TG; cat. no. T9033; MilliporeSigma) treatment, KYSE-150 and TE-1

cells were cultured at 37°C and treated with 100 nM TG for 0 to 24

h. For recombinant human (rh-)CXCL8 (cat no. HY-P7379;

MedChemExpress) treatment, KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were cultured at

37°C and treated with rh-CXCL8 at varying concentrations (0, 10,

20, 40, 80 or 160 ng/ml) for 0 to 48 h. For TGF-β1 (cat. no.

HY-P7118; MedChemExpress) treatment, KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were

cultured at 37°C and treated with 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 48 h.

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assays

Total RNA was extracted from KYSE-150, KYSE-170,

TE-1 and HEEC cells (4×106 cells per sample) using

Triquick reagent (cat. no. R1100; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with the

Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (cat. no. 04896866001;

Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer's protocol. SYBR

Green real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR premix (cat. no.

B110031; Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) was carried out in StepOnePlus

real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR system (Applied Biosystems;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following cycling

conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of

95°C for 15 sec, 56°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 30 sec, and a final

extension at 72°C for 7 min. The expression levels of genes were

analyzed with the 2−ΔΔCq method (33) and normalized to endogenous GAPDH.

Primer sequences are listed in Table

SI.

RNA sequencing analysis

TE-1 cells were treated with 100 nM TG for 12 h

under standard culture conditions (37°C; 5% CO2), after

which total RNA was extracted using TRIzol™ Reagent

(cat. no. 15596026CN; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The quality

and integrity of the RNA samples were assessed using an Agilent

2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Library

construction, sequencing and data analysis were carried out by

Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. Sequencing was carried out on an Illumina

platform using paired-end sequencing with a read length of 150 bp.

The sequencing was performed using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system

with the NovaSeq 6000 S4 Reagent Kit (300 cycles; cat. no.

20027466; Illumina, Inc.). The final library was quantified using a

Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the

concentration was adjusted to 10–20 pM prior to sequencing, based

on molar concentration calculations. Bioinformatics analysis was

performed using the programs FastQC (v0.11.9; http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/),

Cutadapt (v2.10; http://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/), HISAT2 (v2.2.1;

http://daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/) and

featureCounts (v2.0.1; http://subread.sourceforge.net/featureCounts.html).

Statistical analysis and visualization were conducted in R (v4.3.2;

https://www.r-project.org/; The R

Foundation). Differential expression analysis was conducted in R

(v4.3.2; http://www.r-project.org) using

DESeq2 (v1.30.1; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html).

Differentially expressed genes were screened based on the following

criteria: |log2foldchange|>1, adjusted P<0.05.

Cell transfection

ERN1, EIF2AK3 and ATF6 small interfering (si)RNA,

alongside si-negative control were purchased from Shanghai

GenePharma Co., Ltd., sequences are listed in Table SII. pcDNA3.1-XBP1 and

pcDNA3.1-ATF6 were purchased from GenScript Biotech Corporation.

The cDNA encoding ATF4 was amplified and inserted into the pcDNA3.1

vector (cat. no. V79520; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific

Inc.), named pcDNA3.1-ATF4, sequences are listed in Table SIII. KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were

seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well

and cultured for 24 h to allow adherence. Upon reaching 70–80%

confluency, transfection was carried out according to the

manufacturer's protocol for Lipofectamine® 2000 (cat.

no. 11668500; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Specifically, 3 µg of target overexpression plasmid and empty

vector control plasmid or 100 pmol of siRNA and negative control

siRNA was mixed with transfection reagent at room temperature for

20 min and added to the cell culture system. Post-transfection,

cells were maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. The

culture medium was replaced with fresh medium at 6 h. After 48 h of

total incubation, cells were harvested for transfection efficiency

analysis by RT-qPCR and subsequent experiments.

Lentiviral infection

Full-length human CXCL8 cDNA was obtained via

RT-qPCR and inserted into the lentiviral expression vector

pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puro. The recombinant plasmid (10 µg), along with

the packaging plasmid psPAX2 (7.5 µg) and the envelope plasmid

pMD2.G (5 µg), was mixed and incubated at room temperature for 20

min to form the transfection complex. The complex was then

co-transfected into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000®

to produce lentiviral particles at 37°C for 6 h, after which the

medium was replaced with fresh medium. After 48 h, viral

supernatants were harvested and subsequently used to transduce

KYSE-150 cells. Infected cells were cultured in medium containing

1.0 µg/ml puromycin for 14 days to generate a stable KYSE-150 cell

line with CXCL8 overexpression.

Western blot analysis

KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were washed in ice-cold PBS

and RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. R0010; Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd.). PMSF (cat. no. P0100; Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to extract proteins

from cells. Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA

Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. PC0020; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly,

samples were mixed with working reagent (1:50 ratio) and incubated

at 37°C for 30 min before absorbance measurement at 562 nm. Protein

(50 µg/lane) was then separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to

PVDF membranes (cat. no. 1.15546; MilliporeSigma). Membranes were

blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS with 0.05% Tween-20 for 1 h at

room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies

overnight at 4°C and corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary

antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The enhanced

chemiluminescence detection reagent (cat. no. WBULS0100;

MilliporeSigma) was used to detect the protein bands by Chemi XT 4

(Syngene). The antibodies are listed in Table SIV.

Gene expression profiling interactive

analysis (GEPIA) database analysis

Expression profile analysis of CXCL8 across various

types of cancer and normal tissues was carried out using the GEPIA

web server (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), which integrates RNA

sequencing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and Genotype-Tissue

Expression projects. The ‘Expression DIY’ module was used to assess

CXCL8 mRNA expression in pan-cancer types, and to compare its

expression levels between ESCC and normal esophageal tissues. The

thresholds were set at |log2 fold change (FC)|>1 and

P<0.01 to define significant differential expression. Box plots

were generated directly through GEPIA for visualization.

PROMO database analysis

Prediction of transcription factor binding sites was

performed using the PROMO database (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3),

which is based on the TRANSFAC transcription factor binding site

database. The promoter region (−2,000 bp upstream of the

transcription start site) of the CXCL8 gene was analyzed, with the

species set to Homo sapiens and the maximum matrix

dissimilarity rate set to 15%. Candidate transcription factors were

selected based on their known relevance to ERS for further

validation.

Cell proliferation assay

Cellular proliferation capability was detected using

an MTS assay. Briefly, 1×103 cells pretreated with

rh-CXCL8 for 24 h under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5%

CO2) were seeded per well in 96-well plates. At 0, 24,

48, 72 and 96 h post-seeding, CellTiter 96® AQueous One

Solution Reagent (cat. no. G3582; Promega Corporation) was added,

followed by a 2-h incubation at 37°C before measuring absorbance at

490 nm.

Cell migration and invasion

assays

Wound healing and Transwell assays were carried out

to detect the migration and invasion ability of cells. For the

wound healing assay, treated cells (KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells

subjected to 24 h treatment with NC or 10 ng/ml rh-CXCL8, 12 h

treatment with 100 nM TG, 48 h transfection with 100 pmol siCXCR1

and combined treatment with 100 nM TG and 100 pmol siCXCR1) were

inoculated in 6-well plates and cultured in medium containing 10%

FBS. A straight scratch was made in each well when the cell

monolayer reached near complete confluence, and cells were then

maintained in serum-free medium. Images were taken at the same

position at 0 and 24 h using an inverted optical microscope (Nikon

Eclipse 50i; Nikon Corporation). Subsequently, ImageJ (National

Institutes of Health) software was employed to analyze the acquired

images. The calculation of scratch area percentage was defined as

the ratio of scratch area at 24 h to the scratch area at 0 h for

each group.

For the Transwell invasion assay, 1×105

indicated cells in 200 µl serum-free medium were placed in the

upper chamber (Corning, Inc.) and cultured at 37°C for 24 h. The

chamber had been previously coated with 200 µl Matrigel (incubated

at 37°C for 6 h), and 0.7 ml medium containing 10% FBS was placed

in the lower chamber. Cells on the upper surface were wiped off

after 24 h of incubation and 4% paraformaldehyde was used to fix

the invasive cells on the lower surface of the chamber which was

then stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution for 20 min at room

temperature. Subsequently, the number of invading cells was counted

in five random fields selected by an inverted microscope, and the

average was calculated. The migration assay was carried out

following the same protocol as the invasion assay, except that

Transwell membranes were not coated with Matrigel.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

In KYSE-150 cells, the promoter-reporter gene

plasmids (containing promoter regions derived from CXCL8, SNAI2 and

ZEB1) were separately co-transfected with pcDNA3.1-XBP1,

pcDNA3.1-ATF4, pcDNA3.1 empty plasmid or treated with TGF-β1.

Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection and

treatment under standard culture conditions (37°C; 5%

CO2), using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter

Assay System (cat. no. E1910; Promega Corporation) according to the

manufacturer's instructions and normalized to Renilla luciferase

activity. The primer sequences for the dual-luciferase reporter

plasmids are detailed in Table

SV.

Animal experiments

A total of 10 BALB/c-nude mice (6-week-old male and

body weight of 18–22 g) were purchased from the Beijing Huafukang

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Mice were housed under standard conditions

and had unlimited access to sterilized food and distilled water.

Room temperature was maintained at 24±2°C, relative humidity was

maintained at 60±10% and a 12-h light/dark cycle was used. After 7

days of acclimation, the mice were randomly divided into two

experimental groups (n=5 per group): i) Control group, ii)

CXCL8-overexpressed group. Group i) mice served as the normal

control group and were subcutaneously injected with

5×106 control (KYSE-150) cells into the dorsal flanks.

Group ii) was the CXCL8-overexpressed group and the mice were

injected with a total of 5×106 CXCL8-overexpressing

KYSE-150 cells into the dorsal flanks. The total duration of the

animal study was 30 days. The mice were monitored daily for food

and water intake, weight, body posture, behavior, distress and

response to external stimuli.

Humane endpoints of the present study were loss of

>20% body weight, severe dehydration, refusal of food, severe

pain or distress or a moribund state, no animals reached these

endpoints or were found dead during the present study. All mice

were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg

pentobarbital sodium and 0.5–1 ml blood was collected by cardiac

puncture followed by sacrifice by exsanguination. Indexes such as

breathing, heartbeat, pupils and nerve reflexes were assessed to

confirm death. Mice were euthanized after 30 days, and terminal

volume and weight of tumor tissues were measured. The present study

was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

(IACUC) of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University

(approval no. IACUC-4th Hos Hebmu-2023001).

Immunohistochemical staining

assay

In the CXCL8-overexpressing mouse model, both

esophageal carcinoma and adjacent normal tissues were collected and

fixed in 4% formaldehyde at 4°C for 24–48 h. After washing with

PBS, the specimens were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series,

embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4-µm. The

sections were then blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide (15 min at

room temperature) to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity and

subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at

>95°C for 5 min. Primary antibodies against CXCR1/2, p-SMAD2/3,

SNAI2 and ZEB1 (all at 1:100 dilution) were applied and incubated

overnight at 4°C, followed by a 2 h room temperature incubation

with secondary antibodies. The stained sections were visualized

using an inverted optical microscope. The antibody information is

identical to that used for western blotting (Table SIV).

Prediction of SMAD3-regulated miRNAs

targeting ZEB1

To identify candidate miRNAs that may be

transcriptionally regulated by SMAD3 and simultaneously target

ZEB1, bioinformatics screening was conducted using the

TransmiR v3.0 (http://www.cuilab.cn/transmir) and TargetScan Release

7.1 (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/). First, TransmiR

v3.0 was queried to identify miRNAs either known or predicted to be

regulated by SMAD3. Subsequently, TargetScan was used to predict

miRNAs with conserved binding sites in the 3′-untranslated region

(3′-UTR) of ZEB1. The predicted miRNAs from both TransmiR v3.0 and

TargetScan databases were compared, and the overlapping miRNAs were

identified as potential candidates linking SMAD3 and ZEB1.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.0 (Dotmatics) was used to carry out

data analysis and graphing. Statistical significance was determined

using an unpaired Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's

post hoc test. All in vitro experiment data came from three

independent experiments carried out in triplicate and presented as

mean ± SD. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

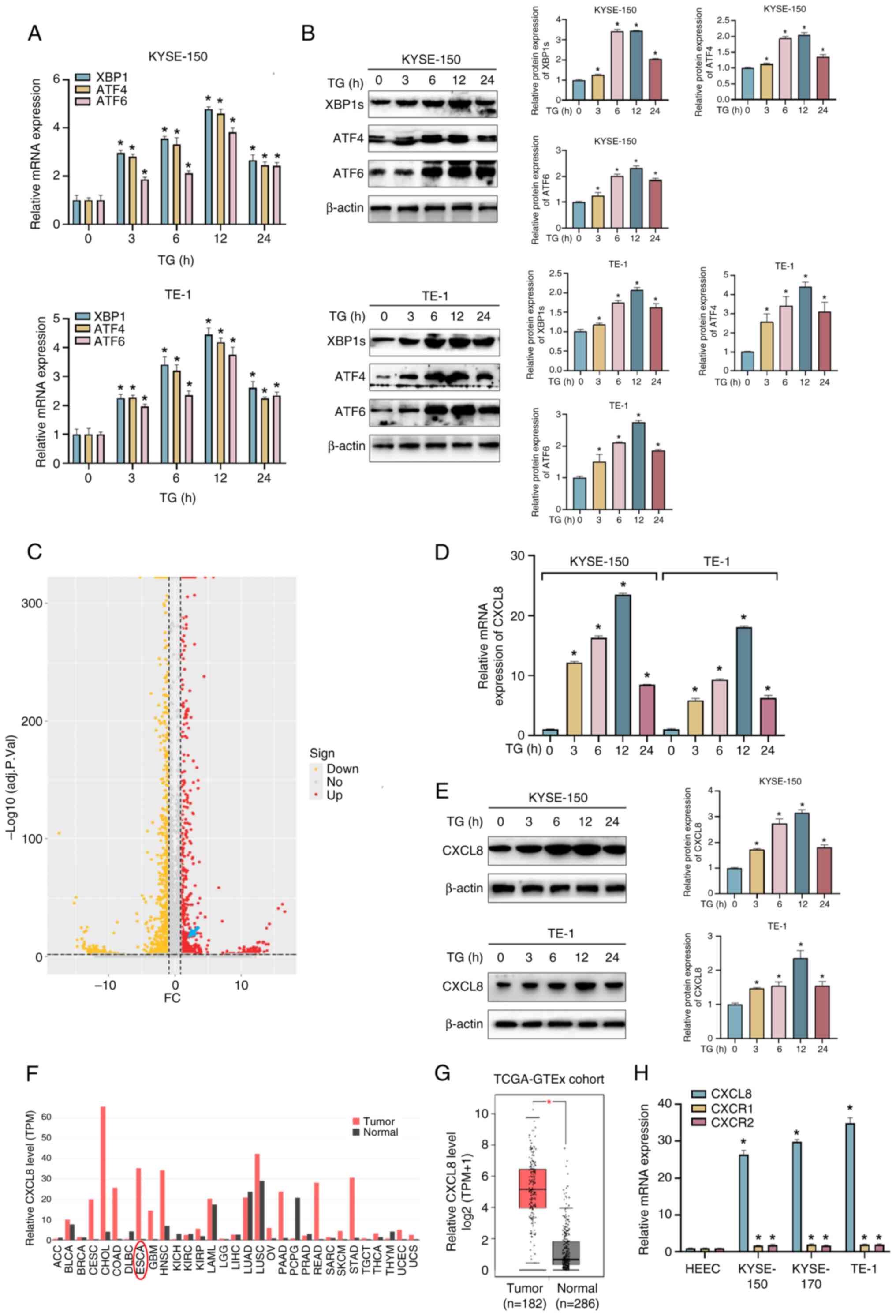

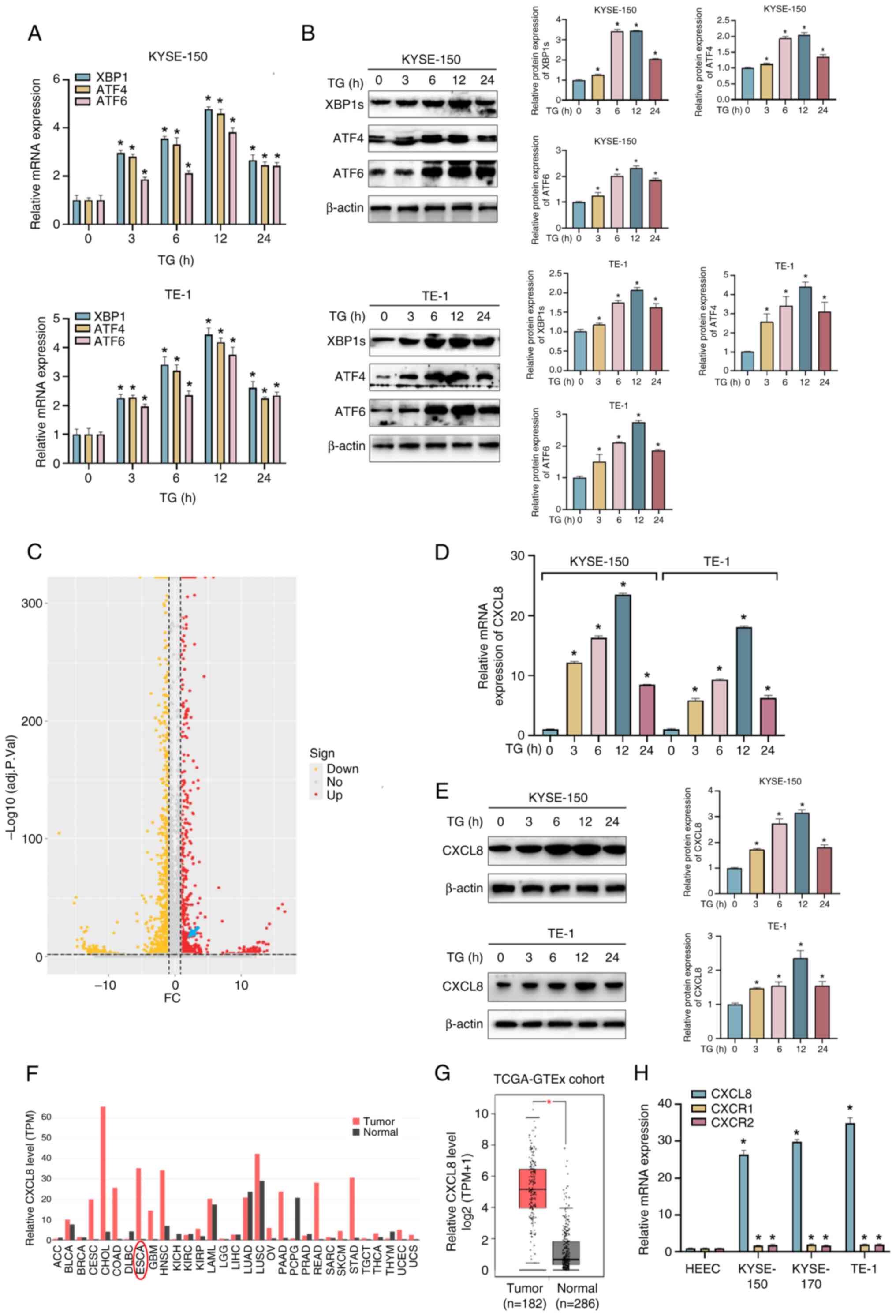

CXCL8 is induced by ERS in ESCC

ESCC cells were treated with 100 nM TG (an ERS

inducer) for 0–24 h (34), after

which expression of effectors of the UPR were assessed. The mRNA

and protein expression levels of XBP1, ATF4 and ATF6 peaked at 12 h

after TG treatment (Fig. 1A and

B). To explore the potential mechanism of ERS in ESCC

progression, RNA sequencing analysis was employed to compare the

gene expression profiles between TE-1 cells treated with either TG

or DMSO. CXCL8 was one of the top ranked differentially altered

genes in response to ERS (Fig.

1C). The elevated mRNA and protein expression levels of CXCL8

were further verified at 12 h in TG-treated KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells

by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis (Fig. 1D and E). CXCL8 was significantly

upregulated in a variety of types of cancer, including esophageal

cancer by searching the GEPIA database (Fig. 1F and G). The mRNA expression level

of CXCL8, as well as its receptors, CXCR1 and CXCR2, was increased

in ESCC cells compared with that in HEEC cells (Fig. 1H).

| Figure 1.Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces

CXCL8 expression in ESCC cells. KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were

treated with 100 nM TG for 0, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h, and expression

levels of effectors in the UPR were examined by (A) RT-qPCR and (B)

western blot analysis. (C) The volcano plot shows differentially

expressed genes in TE-1 cells treated with 100 nM TG for 12 h. The

x-axis represents the log2-transformed of FC ratios and the y-axis

is the log10-transformed adjusted P-value. Red/yellow dots

represent significantly up/downregulated genes (|log2FC|≥1,

adj.P<0.05). The blue arrow indicates the possible location of

CXCL8. The (D) mRNA and (E) protein expression levels of CXCL8 in

ESCC cells treated with 100 nM TG for 24 h. (F) The CXCL8

expression profile across all tumor samples and corresponding

normal tissues was obtained from the GEPIA. (G) The mRNA expression

levels of CXCL8 in ESCC tissues (n=182) and normal tissues (n=286)

were obtained from the GEPIA database. (H) Expression levels of

CXCL8, the receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 in the normal esophageal

epithelial cell line and ESCC cell lines were determined by RT-qPCR

method. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n=3/group. *P<0.05

vs. TG-treated 0 h group. CXCL8, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand;

ESCC, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; TG, thapsigargin; FC,

fold change; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive

£Analysis, RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; HEEC,

human normal esophageal epithelial cell; XBP1, X-box binding

protein 1; ATF, activating transcription factor; TCGA-GTEx; The

Cancer Genome Atlas-Genotype-Tissue Expression; sign, significance;

up, upregulated; no, no significance; down, downregulated; TPM,

transcript per million. |

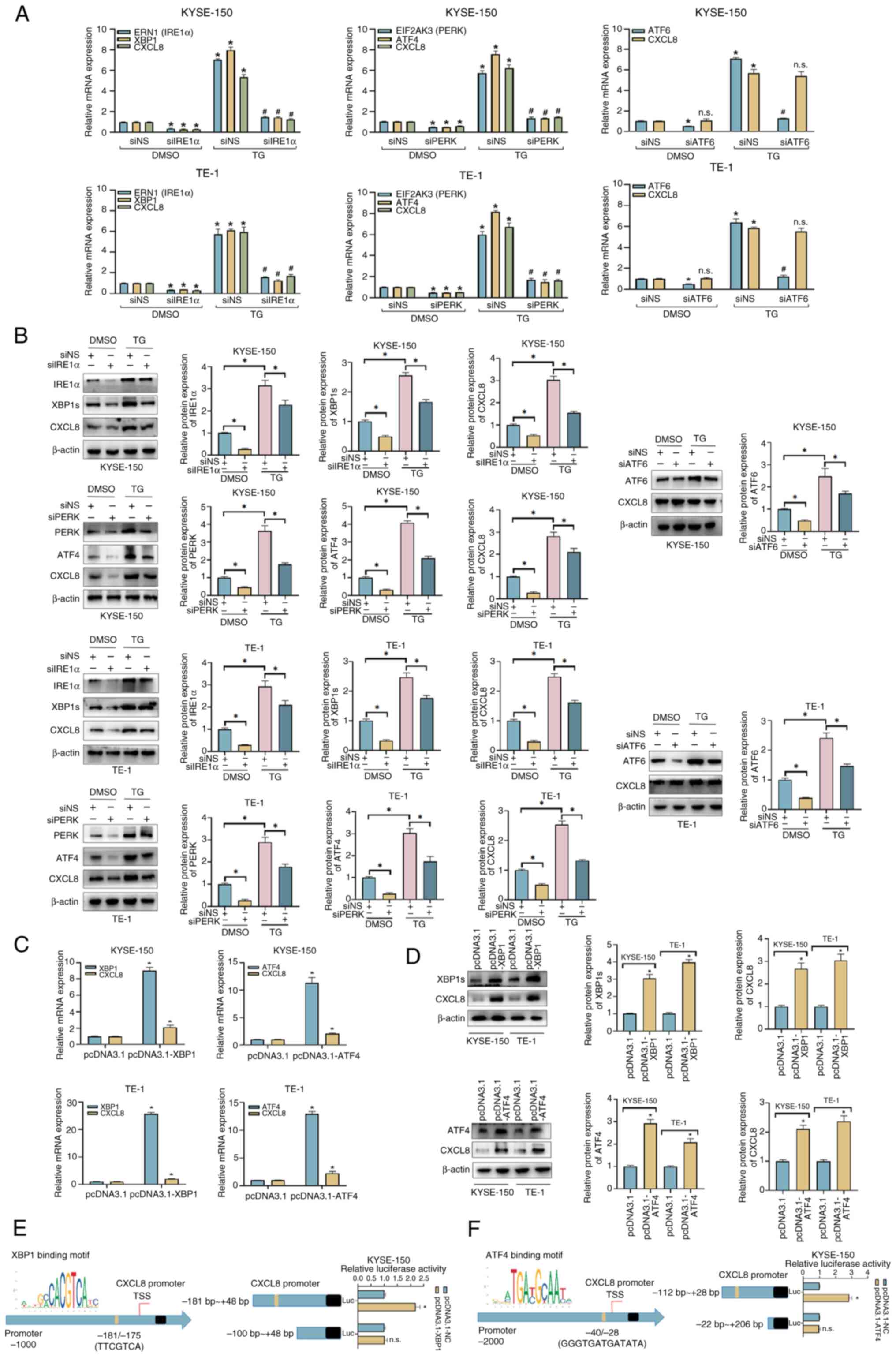

Both the IRE1α and PERK pathways

regulate the transcription of CXCL8

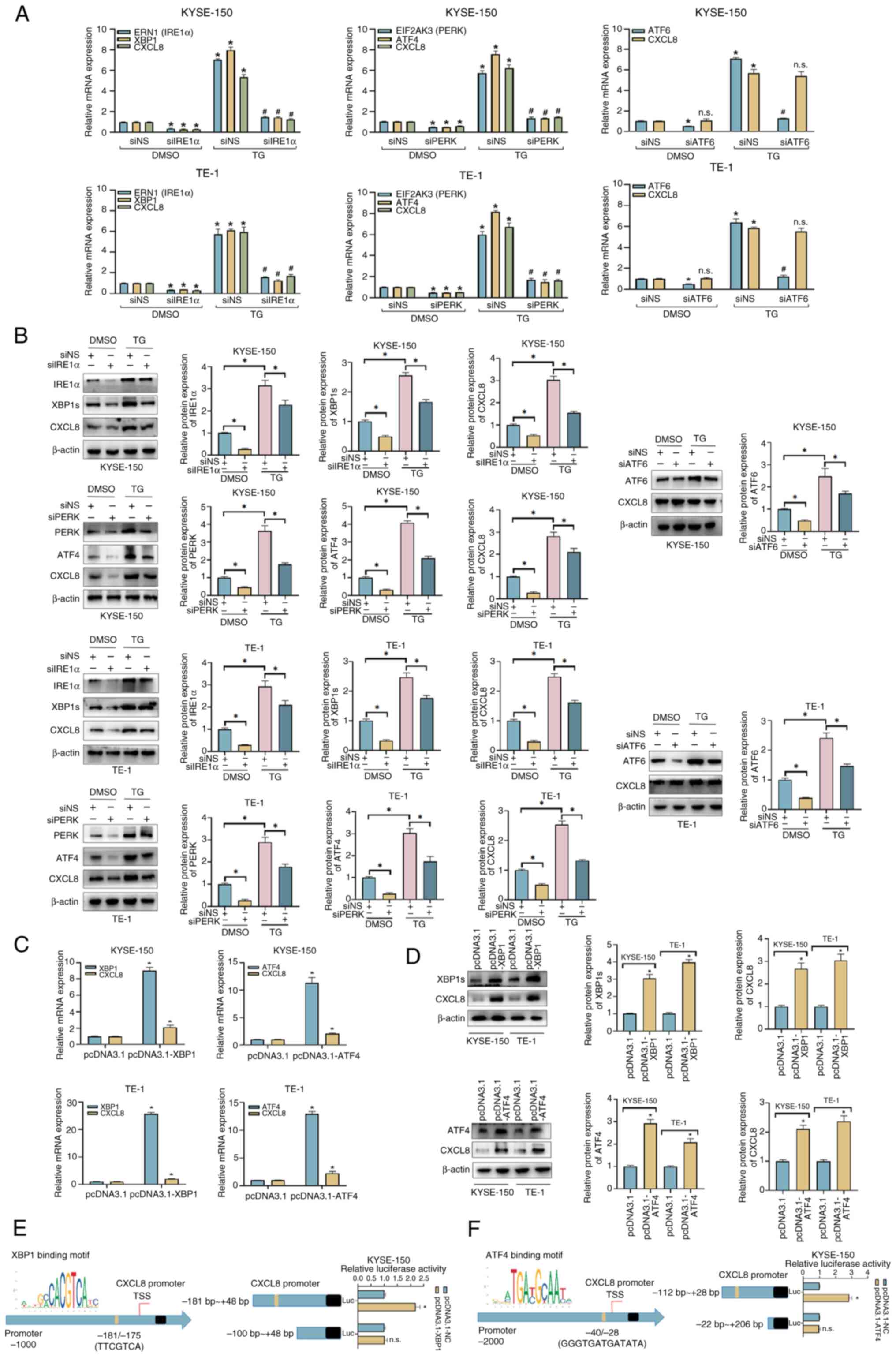

To explore the signaling pathways which may be

responsible for induction of CXCL8, three transmembrane sensors

(IRE1α, PERK and ATF6) were respectively knocked down in KYSE-150

and TE-1 cells using siRNAs, and the knockdown efficiency was

validated by RT-qPCR assay (Fig.

S1A). As shown in Fig. 2A and

B, under the DMSO-treated condition, knockdown of the three

sensors resulted in reduced expression of their downstream

transcription factors (XBP1, ATF4, and ATF6). A decrease in CXCL8

expression was observed only in the siIRE1α + DMSO and siPERK +

DMSO groups under the DMSO-treated condition. Under the TG-treated

condition, the siNS + TG group exhibited significantly increased

mRNA and protein levels of the three sensors, their downstream

transcription factors, and CXCL8, compared with the siNS + DMSO

group. In the siRNA + TG groups, the mRNA and protein levels of the

three sensors, their downstream transcription factors, were

decreased compared with those in the siNS + TG group; however, a

reduction in CXCL8 mRNA and protein expression was observed only in

the siIRE1α + TG and siPERK + TG groups. Elevated levels of CXCL8

mRNA and protein in KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells overexpressing XBP1 and

ATF4, the downstream transcription factors of IRE1α and PERK,

respectively were detected (Fig. 2C

and D). In contrast, the expression level of CXCL8 was not

influenced by the overexpression of ATF6 (Fig. S1B and C), indicating that

upregulation of CXCL8 in ERS may be regulated by the IRE1α/XBP1 and

PERK/ATF4 signaling pathways. As transcription factors, XBP1 and

ATF4 carry out key roles by regulating the transcription of various

genes which are involved in ERS. A possible binding site of XBP1 on

the promoter region of CXCL8 (−181 bp/-175 bp) was predicted by the

PROMO database, and the binding effect was further verified by

dual-luciferase reporter assay in KYSE-150 cells (Fig. 2E). A possible binding site of ATF4

on the promoter region of CXCL8 (−40 bp/-28 bp) was also predicted

and the transcriptional regulatory effect of ATF4 on CXCL8 was also

verified (Fig. 2F).

| Figure 2.CXCL8 is induced by the PERK and

IRE1α pathways of the unfolded protein response in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma cells. Evaluation of the indicated (A) mRNA

and (B) protein expression levels in siRNA-transfected KYSE-150 and

TE-1 cells, which were treated with 100 nM TG or DMSO for 24 h.

Evaluation of (C) mRNA and (D) protein expression levels of CXCL8

in transfected KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and western blot analysis.

Dual-luciferase reporter assays were conducted in KYSE-150 cells to

verify the direct binding effects of (E) XBP1 and (F) ATF4 on the

CXCL8 promoter. All data are expressed as mean ± SD, n=3/group.

*P<0.05, vs. siNS + DMSO group, siNS + TG group or pcDNA3.1

group; #P<0.05 vs. siNS + TG group. n.s., not

significant; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α; PERK, protein

kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; si, small

interfering; ERN, endoplasmic reticulum to nucleus signaling;

EIF2AK3, ATF, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha

kinase 3; TG, thapsigargin; NS, non-silencing; CXCL, C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand. |

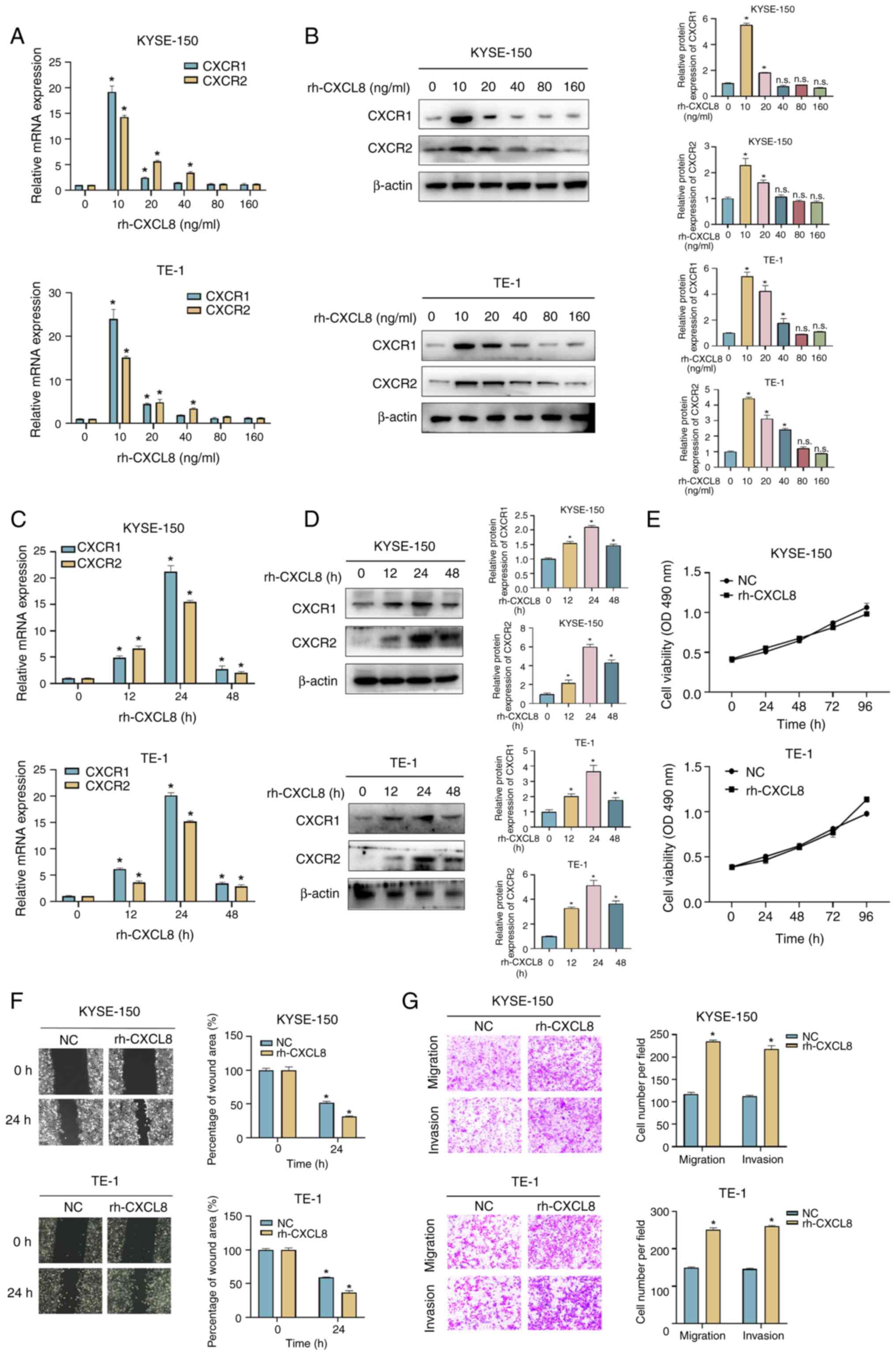

CXCL8 promotes ESCC cells migration

and invasion in vitro

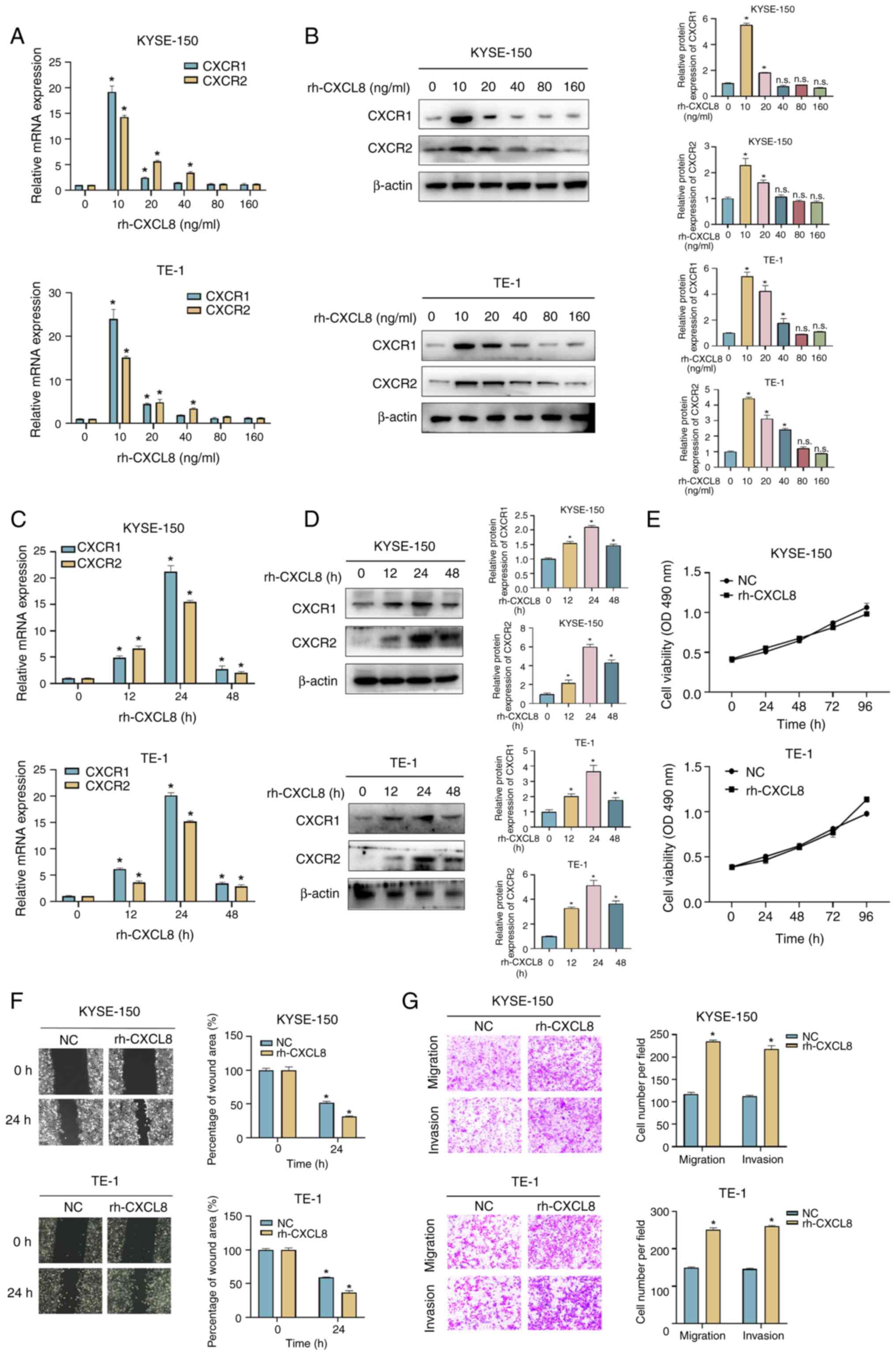

In order to study the biological function of CXCL8

in ESCC, KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were treated with rh-CXCL8, and

the expression levels of CXCR1 and CXCR2 were assessed. As shown in

Fig. 3A-D, the mRNA and protein

expression levels of both receptors peaked at 24 h with 10 ng/ml

rh-CXCL8 treatment. ESCC cells were then treated with 10 ng/ml

rh-CXCL8 for 24 h to detect the variation of cell function. CXCL8

had no effect on the viability of ESCC cells (Fig. 3E) but significantly promoted their

migration and invasion (Fig. 3F and

G).

| Figure 3.CXCL8 facilitates migration and

invasion of ESCC cells. Evaluation of (A) mRNA and (B) protein

expression levels of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells

treated with 0, 10, 20, 49, 80 and 160 mg/ml rh-CXCL8 for 24 h.

Evaluation of (C) mRNA and (D) protein expression levels of CXCR1

and CXCR2 in KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells treated with 10 ng/ml rh-CXCL8

for 0, 12, 24 and 48 h. (E) Cell proliferation was analyzed with an

MTS assay in KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells treated with 10 ng/ml rh-CXCL8

for 24 h. (F) Wound healing and (G) Transwell assays were conducted

to assess the migration and invasion abilities in KYSE-150 and TE-1

cells treated with 10 ng/ml rh-CXCL8 for 24 h. All data are

expressed as mean ± SD, n=3/group. *P<0.05 vs. 0 ng/ml

rh-CXCL8-treated group, rh-CXCL8-treated 0 h group, NC-treated 0 h

group or NC group. n.s., not significant; rh-CXCL, recombinant

human-C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; CXCR, chemokine receptor; NC,

negative control. |

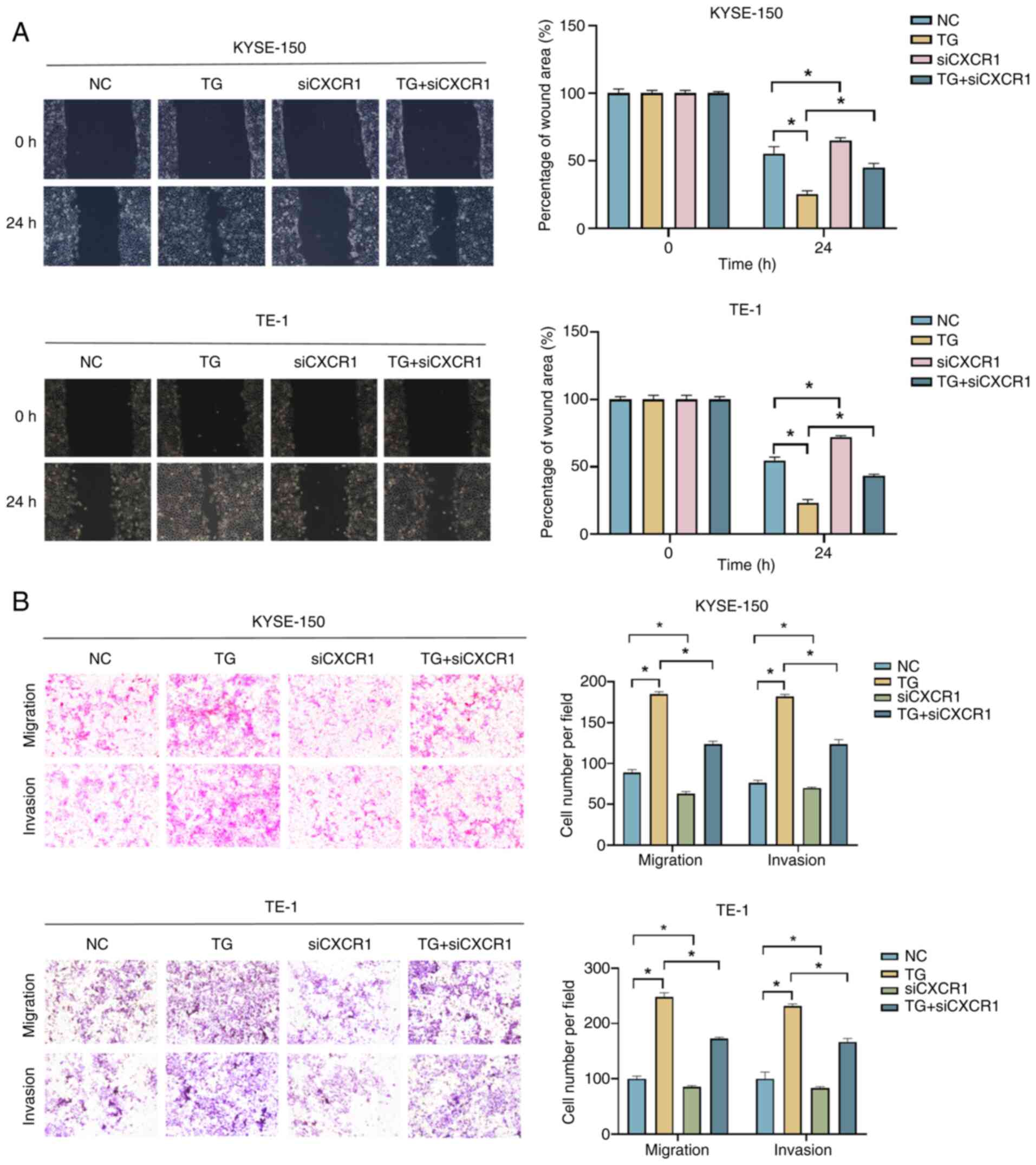

CXCL8/CXCR1 promotes migration and

invasion of ESCC cells under an ERS state

Roles of CXCL8/CXCR1 in the progression of ESCC

cells under ERS state were further examined. The knockdown

efficiency of CXCR1 was validated by an RT-qPCR assay (Fig. S1D). When ESCC cells were treated

with 100 nM TG for 24 h, cell migration and invasion were

significantly enhanced, while knockdown of CXCR1 partially

prevented this effect (Fig. 4A and

B).

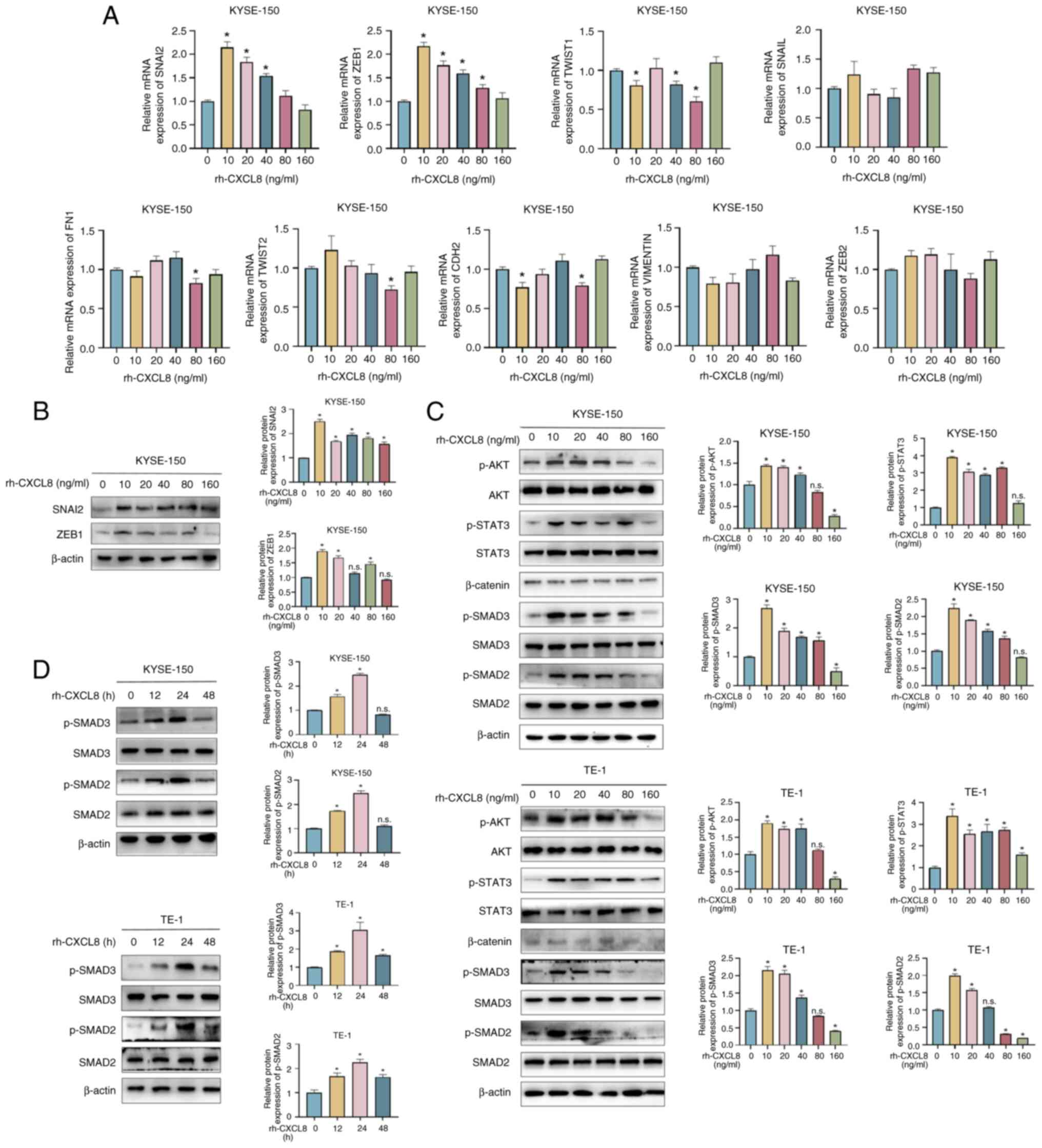

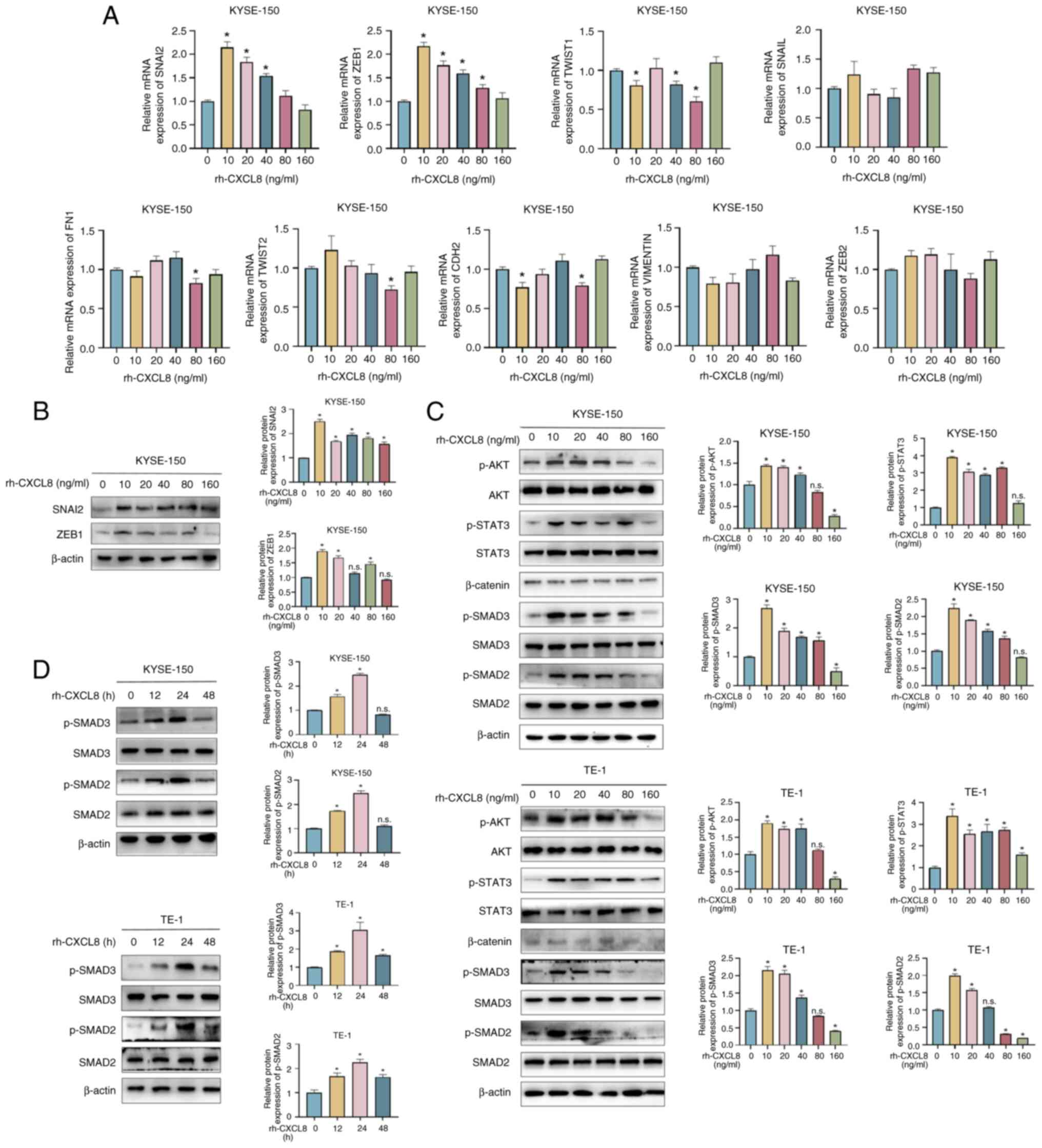

CXCL8 increases the expression of

EMT-related genes, SNAI2 and ZEB1

Considering that both ERS and CXCL8 promoted the

migration and invasion of ESCC cells, the mRNA expression levels of

a set of EMT-related genes were screened in rh-CXCL8-treated ESCC

cells, including SNAI2, ZEB1, TWIST1, SNAIL, FN1, TWIST2, CDH2,

VIMENTIN and ZEB2. Among these genes, SNAI2 and ZEB1 demonstrated

the most significant trend of increased expression in KYSE-150

(Fig. 5A) and TE-1 cells (Fig. S2) when treated with 10 ng/ml

rh-CXCL8. Nevertheless, further increases in the rh-CXCL8

concentration led to a progressive decline in their expression

levels. The protein expression levels of SNAI2 and ZEB1, which were

similar to their mRNA expression levels, were further verified in

rh-CXCL8-treated ESCC cells by western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). Given that SNAI2 and ZEB1 are

important genes involved in EMT process, we hypothesized whether

CXCL8 promoted the expression of SNAI2 and ZEB1 by regulating the

activation of EMT-related pathways. The PI3K/AKT, JAK2/STAT3,

Wnt/β-catenin and TGF-β/SMAD pathways are important pathways that

regulate the EMT process, therefore whether CXCL8 promoted the

activation of these pathways was further investigated. As shown in

Fig. 5C and D, rh-CXCL8 treatment

promoted phosphorylation of AKT, STAT3 and SMAD2/3, whereas its

effect on β-catenin appeared to be minimal although this was not

quantitatively assessed, suggesting that CXCL8 may be involved in

the progression of EMT by regulating the activation of AKT, STAT3

and SMAD2/3. The present study revealed several signaling pathways

that may be involved in the action of CXCL8. Since activation of

AKT and STAT3 by CXCL8 has been reported (35–37),

which is consistent with the findings of the present study, the

TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway was the focus of the present

study.

| Figure 5.CXCL8 participates in the EMT process

by regulating the expression of SNAI2 and ZEB1. KYSE-150 cells were

treated with specified concentrations of rh-CXCL8 for 24 h, and

then (A) mRNA expression of SNAI2, ZEB1, TWIST1, SNAIL, FN1,

TWIST2, CDH2, VIMENTIN and ZEB2 was detected by RT-qPCR, and (B)

protein expression of SNAI2 and ZEB1 was detected by western

blotting. (C) KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were treated with specified

concentrations of rh-CXCL8 for 24 h and the protein expression

levels of EMT-related pathway genes were examined by Western blot

assay. (D) KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml

rh-CXCL8 for indicated times, and the protein expression of SMAD2/3

and p-SMAD2/3 was detected by Western blot assay. All data are

expressed as mean ± SD, n=3/group. *P<0.05 vs. 0 ng/ml

rh-CXCL8-treated group or rh-CXCL8-treated 0 h group. n.s., not

significant; rh-CXCL, recombinant human C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand; EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition. |

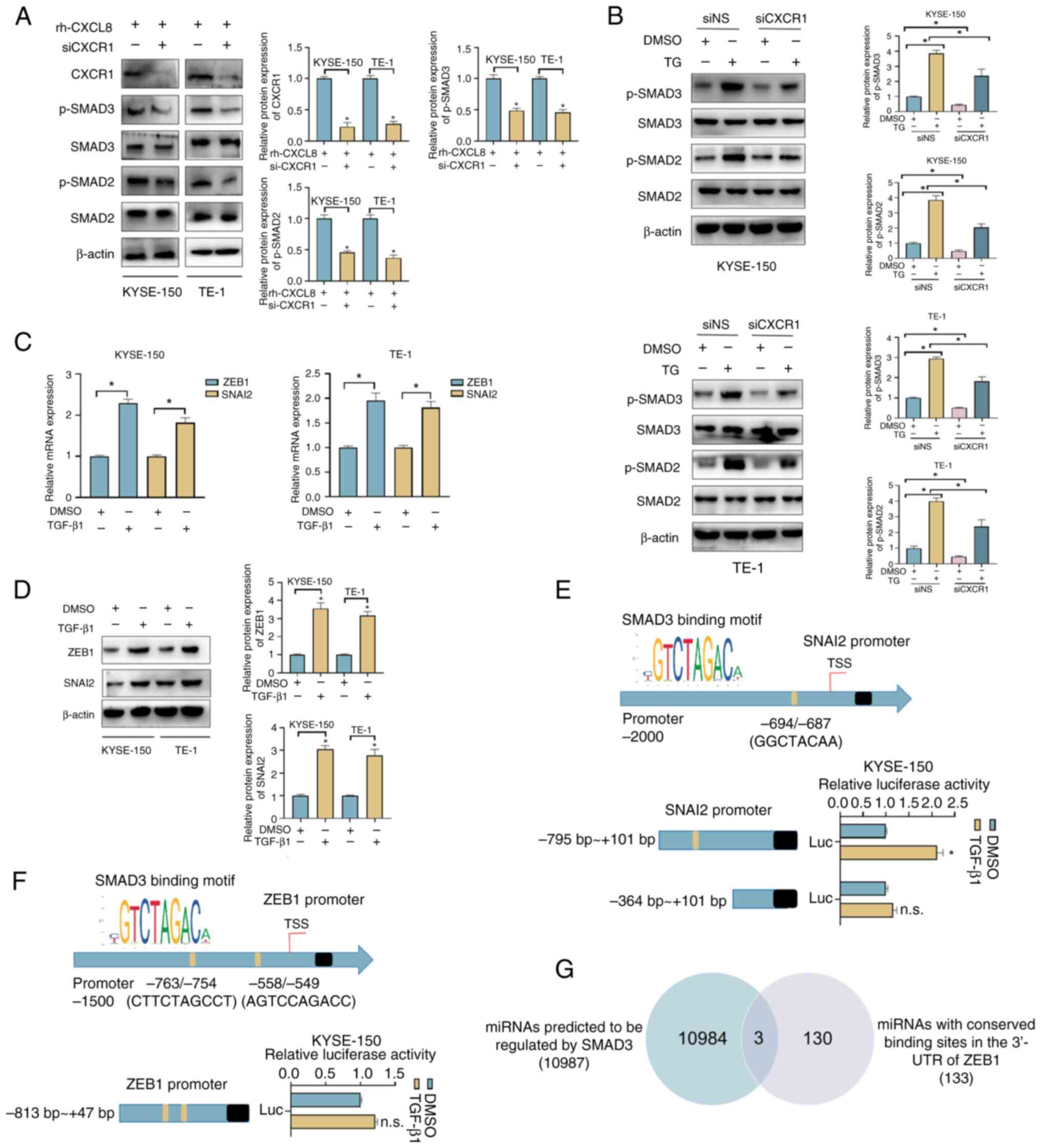

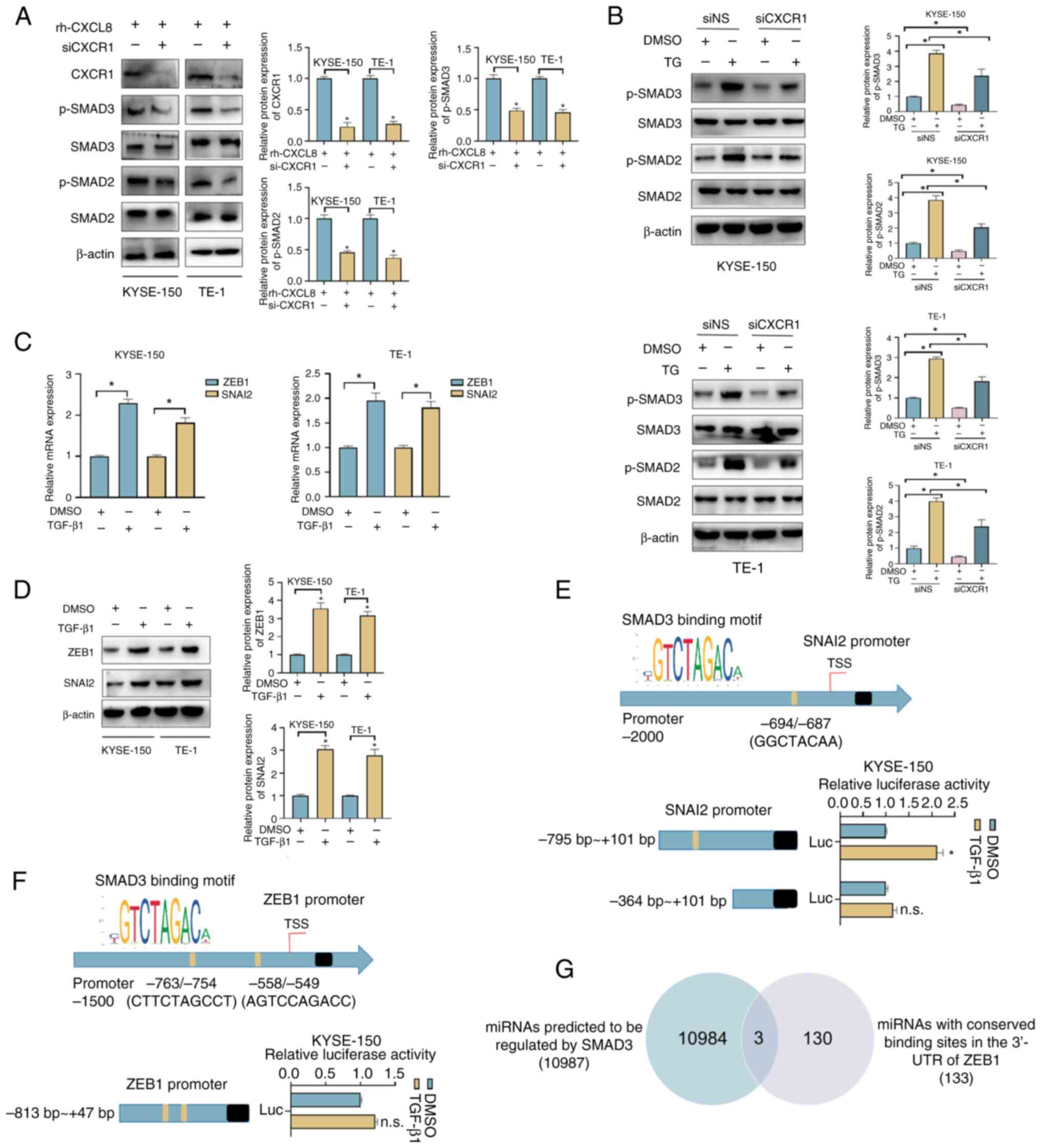

CXCL8/CXCR1 promotes the EMT process

by activating SMAD2/3

CXCR1 was knocked down to study the activating

effect of CXCL8 on SMAD2/3. As shown in Fig. 6A, the protein expression levels of

p-SMAD2/3 were significantly reduced when CXCR1 was knocked down,

suggesting that CXCL8 may activate SMAD2/3 by binding to CXCR1. The

regulatory role of CXCL8/CXCR1 in the ERS state was further

analyzed. As shown in Fig. 6B, the

expression levels of p-SMAD2/3 were significantly increased in

TG-treated ESCC cells, whereas knockdown of CXCR1 partially

alleviated this effect.

| Figure 6.CXCL8 regulates the expression of

SNAI2 and ZEB1 through phosphorylated activation of SMAD2/3. (A)

Influence of knocking down CXCR1 on the protein expression of

SMAD2/3 and p-SMAD2/3 in KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells, treated with 10

ng/ml rh-CXCL8 for 24 h. (B) Influence of knocking down CXCR1 on

protein expression of SMAD2/3 and p-SMAD2/3 in TG (100 nM; 24 h)

treated KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells. (C) mRNA and (D) protein

expression levels of ZEB1 and SNAI2 were examined in KYSE-150 and

TE-1 cells treated with TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml; 48 h) using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR and western blot analysis.

Dual-luciferase reporter assays were conducted in KYSE-150 cells to

detect the transcriptional regulatory effect of SMAD3 on (E) SNAI2

and (F) ZEB1. (G) Venn diagram showing the bioinformatics

identification of SMAD3-regulated miRNAs that target ZEB1. All data

are expressed as mean ± SD, n=3/group. *P<0.05 vs. rh-CXCL8

group, DMSO + siNS group, TG + siNS group or DMSO group. n.s., not

significant; rh-CXCL, recombinant human-C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand; CXCR, chemokine receptor; p-, phosphorylated; TG,

thapsigargin; si, small interfering; NS, non-silencing; Luc,

luciferase; miRNA, microRNA; UTR, untranslated region. |

Analysis revealed that 10 ng/ml CXCL8 significantly

promoted the expression of SNAI2 and ZEB1 and whether this effect

was achieved through its activation of SMAD2/3 was further

investigated. KYSE-150 and TE-1 cells were treated with 10 ng/ml

TGF-β1 for 48 h (38). As shown in

Fig. 6C and D, increased mRNA and

protein expression levels of SNAI2 and ZEB1 were detected in

TGF-β1-treated cells, potentially indicating the regulatory effect

of TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway on the expression of SNAI2 and

ZEB1. A binding site for SMAD3 was identified in the promoter

region of SNAI2, and dual-luciferase reporter assay confirmed that

exogenous addition of TGF-β1 promoted transcription of SNAI2

(Fig. 6E). Two binding sites for

SMAD3 were also found in the promoter region of ZEB1, but ZEB1

transcription was not affected by exogenous incorporation of TGF-β1

(Fig. 6F). miR-3146, miR-3163 and

miR-3171 were predicted to be transcriptionally regulated by SMAD3

and further regulated the expression of ZEB1 by binding to its

3′-UTR (Fig. 6G).

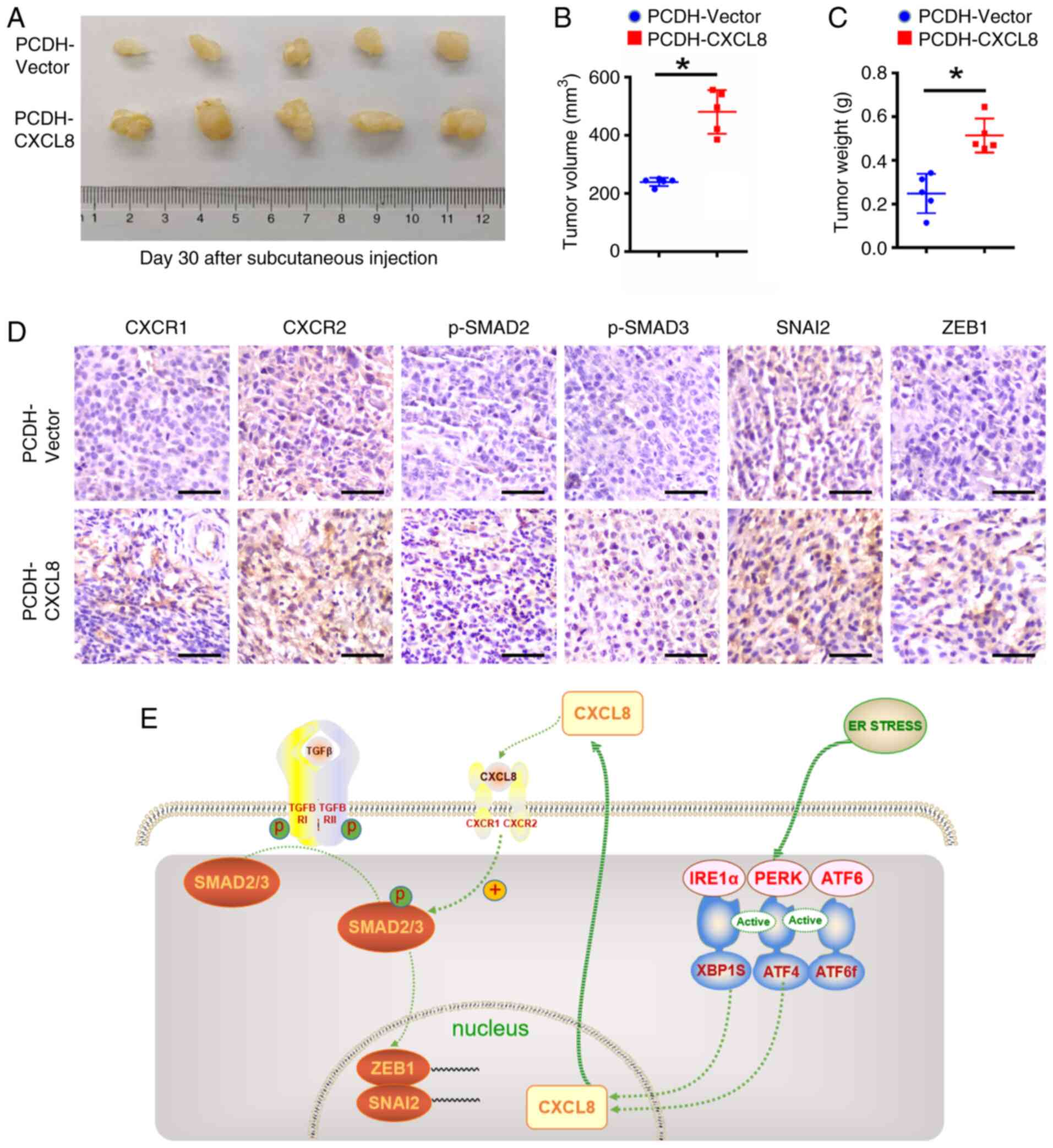

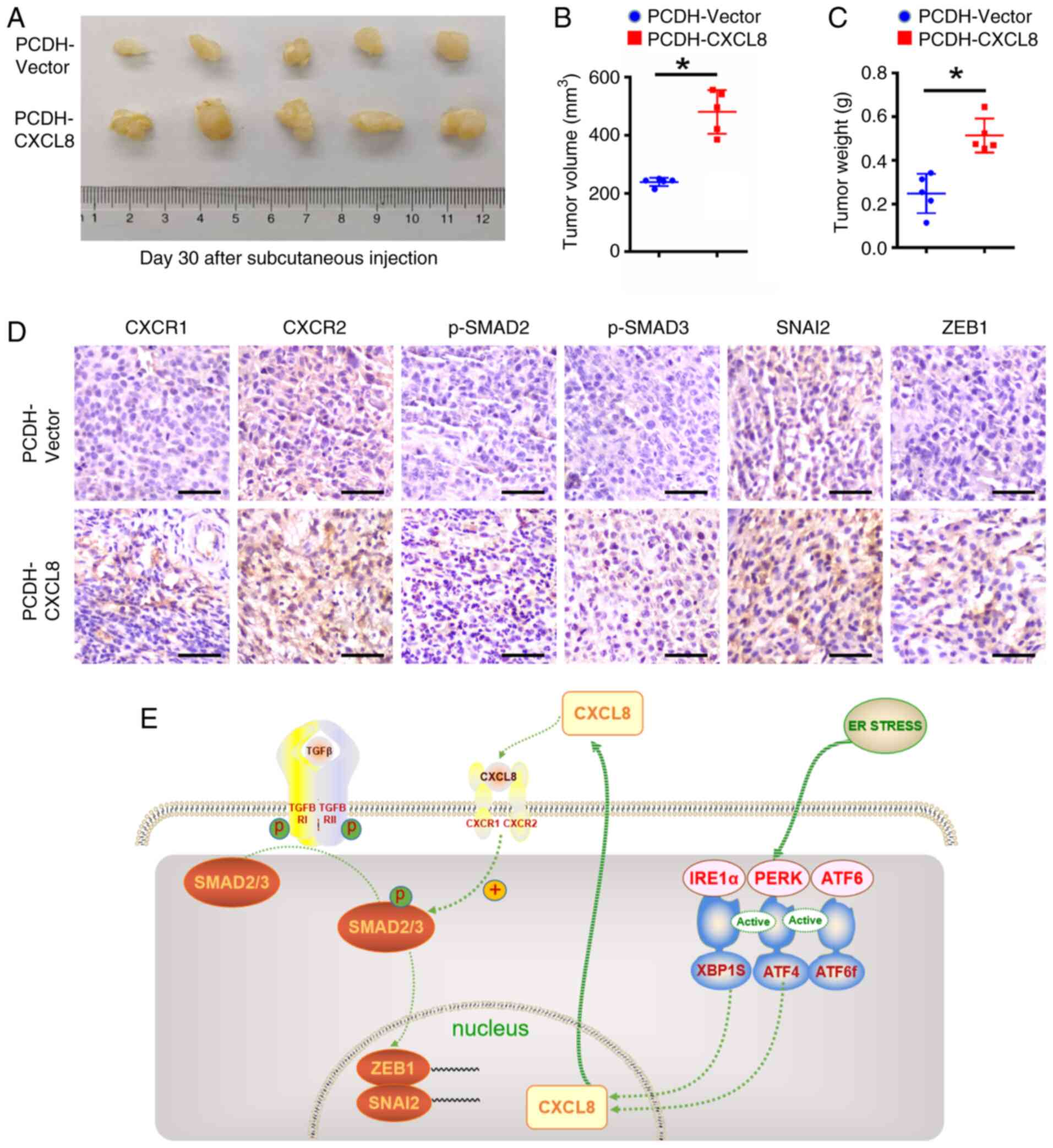

CXCL8 facilitates ESCC progression in

vivo

To evaluate the oncogenic role of CXCL8 in

vivo, KYSE-150 cells stably overexpressing CXCL8 or control

cells were Xeno transplanted subcutaneously into the flanks of

mice. Quantitative analysis at 30 days post-inoculation revealed a

statistically significant augmentation in both tumor volume and

weight in the CXCL8-overexpressing group compared with control

group (Fig. 7A-C), suggesting a

pro-tumorigenic function of CXCL8. To further validate the role of

the CXCL8-CXCR1/2-SMAD2/3-SNAI2/ZEB1 axis in tumor metastasis, the

protein expression levels of CXCR1/2, p-SMAD2/3, SNAI2 and ZEB1

were examined in CXCL8-overexpressing ESCC tissues.

Immunohistochemical analyses revealed enhanced positive staining

for CXCR1/2, p-SMAD2/3, SNAI2 and ZEB1 in the CXCL8-overexpression

group compared with control group (Fig. 7D).

| Figure 7.Animal experiments validate the role

of the CXCL8-CXCR1/2-SMAD2/3-SNAI2/ZEB1 axis in tumor growth and

metastasis. (A) Image of subcutaneous xenograft tumors following

injection of CXCL8-overexpressing KYSE-150 cells (n=5) or control

cells (n=5) in BALB/c-nude mice. The volume (B) and weight (C) of

harvested xenograft tumors were measured (n=5). (D) Representative

immunohistochemical images of CXCR1/2, p-SMAD2/3, SNAI2 and ZEB1

expression in CXCL8-overexpressing ESCC tissues and corresponding

control tissues (n=5). Scale bar, 50 µm. (E) Mechanistic diagram of

CXCL8 in ESCC cells under an ER stress state. All data are

expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. vs. PCDH-Vector group. CXCL,

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α;

PERK, protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase;

ATF, activating transcription factor; XBP, X-box binding protein;

ER, endoplasmic reticulum; p-, phosphorylated; ESCC, esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. |

The aforementioned results suggested that CXCL8,

which was highly secreted by ESCC cells in the ERS state, promoted

the EMT process by activating SMAD2/3 after binding to its

receptors. Activated SMAD2/3 directly or indirectly regulated the

transcription of SNAI2 and ZEB1 (Fig.

7E).

Discussion

The significance of ERS in tumor progression is well

recognized, where the activation of the UPR intricately governs the

fate of tumor cells (39,40). In different types of human cancer,

the activation of distinct elements within the UPR cascade was

poised to yield diverse cellular outcomes across nearly all stages

of tumor cell development (14,17,41–43).

In addition, a previous study proposed that the UPR may influence

key characteristics defining cancer, encompassing angiogenesis,

metastasis, genome stability, inflammatory responses and resistance

to drugs (39). As for the role of

ERS in the emergence and advancement of ESCC, studies have revealed

that the ERS-induced PERK/eIF2α/CHOP pathway might impede

proliferation and induce apoptosis (44,45).

The activation of the IRE1/JNK pathway in ESCC is implicated in

regulating apoptosis and autophagy (46). Notably, the IRE1α/AKT/mTOR

signaling axis has been identified as an inducer of apoptosis in

ESCC cells (47). Nevertheless, to

the best of our knowledge, the involvement of CXCL8 in the ERS of

ESCC and its specific functional role have not been reported. The

present study revealed that CXCL8 was one of the most significantly

upregulated genes in ESCC cells with ERS, and may be induced by the

IRE1α-XBP1 and PERK-ATF4 pathways. CXCL8-induced activation of

SMAD2/3 and SMAD2/3 subsequently exerted direct or indirect

regulation of SNAI2 and ZEB1 and promoted the progression of EMT in

ESCC cells.

CXCL8, recognized as a multifaceted chemokine,

encompasses diverse functions in biological processes and has been

implicated in numerous diseases including HIV (48), inflammatory bowel disease (49), reperfusion injury (50) and chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (51,52). The increased expression of CXCL8

has also been reported in several types of cancer. For example,

elevated CXCL8 enhances the tumorigenic properties of human colon

cancer LoVo cells by activating specific signaling pathways

(23); CXCL8 serves as a pivotal

mediator in the tumor-stroma-inflammation network of

triple-negative breast cancer (24) and CXCL8 functions as an autocrine

growth regulator in human lung cancer pathogenesis (25).

Mechanistically, the present study uncovered a

previously unrecognized role of CXCL8 in driving ESCC progression

by engaging in ERS-associated cascades, challenging the

conventional perspective on its pro-metastatic functions.

Functional analyses demonstrated that tumor-derived CXCL8 served in

a dual capacity. It operated in a paracrine manner, modifying the

immune cell composition within the tumor microenvironment.

Simultaneously, CXCL8 acted in an autocrine manner, promoting

oncogenic signaling, angiogenesis and fostering pro-metastatic

traits such as invasion and resistance (53). However, the functional role and

underlying mechanisms of CXCL8 in the ERS state tumors remain

poorly investigated, with limited reports in only a few types of

cancer. In breast cancer cells, CXCL8 has been identified as one of

the secretory factors displaying the highest fold change after

treatment with TG and it might be induced via the PERK-CEBPδ

pathway (54). In thyroid tumors,

TG treatment markedly increased the expression of CXCL8 at both the

mRNA and protein levels (55). In

non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells, the transcription

factors ATF4 and P65 downstream of the UPR directly orchestrated

the transcription of CXCL8 (56).

The present study revealed that the upregulation of CXCL8 in the

ERS state ESCC cells was not only regulated by the PERK/ATF4

signaling pathway as observed in non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma

(56), but also regulated by the

IRE1α/XBP1 pathway. The evident upregulation of CXCL8 by the two

pathways promoted ESCC migration and invasion through participating

in the EMT process.

The augmentation of CXCL8-CXCR1/2 expression has

been observed in several tumors. CXCL8/CXCR1/2 promoted

androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth and proliferation

ability by activating cyclin D1 expression (57). In pancreatic cancer (PaCa),

CXCL8-CXCR2 notably increased cancer cell angiogenesis,

proliferation and invasion ability, and CXCR2 was an

anti-angiogenic target in PaCa (58). CXCR1 also promotes proliferation,

migration and invasion of gastric cancer in vitro and in

vivo (59). CXCL8 enhances

angiogenesis of glioblastoma endothelial cells via CXCR2 signaling

(60). The present study revealed

that CXCL8-CXCR1/2 could facilitate the migration and invasion of

ESCC cells in vitro. The promotion of tumor progression by

CXCL8 occurs due to its binding to CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors,

indicating that targeting this interaction could be a promising

therapeutic strategy for ESCC.

The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis has been reported to be

involved in tumor progression through activating several signaling

pathways, including PI3K/AKT (36,61),

JAK2/STAT3 (37), MAPK (35,62),

phospholipase C (37) and

Rho-GTPase (37). In the present

study, aside from the aforementioned pathways, the phosphorylated

activation of SMAD2/3 by CXCL8/CXCR1 was observed. The activated

SMAD2/3 directly or indirectly modulated the transcription of EMT

markers SNAI2 and ZEB1 to further participate in the EMT process.

The direct transcriptional regulatory effect of p-SMAD2/3 on SNAI2

observed in the present study was consistent with the study by

Brandl et al (63) in panc1

cells, as for the indirect regulation of p-SMAD2/3 on ZEB1, there

may be intermediate genes or mechanisms involved. For example, in

the process of renal fibrosis, the miR-200 family regulates

TGF-β1-induced renal tubular EMT through the SMAD pathway by

targeting ZEB1 (64). Based on

bioinformatics analysis using the TransmiR v3.0 database and

TargetScan Release 7.1, miR-3146, miR-3163 and miR-3171 were

predicted to be regulated by SMAD3 and target the 3′-UTR of ZEB1 to

modulate its expression. However, further studies need to be

carried out to verify this prediction.

In summary, the findings of the present study

highlighted that CXCL8, originating from the IRE1α-XBP1 and

PERK-ATF4 pathways in ERS, facilitated the EMT process in ESCC

cells through the CXCL8-CXCR1/2-SMAD2/3-SNAI2/ZEB1 axis. This

underscored the potential therapeutic strategy of targeting the

CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis to intervene in ERS signaling, hopefully

improving therapeutic efficacy in ESCC treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82372863 and 82203622),

Hebei Natural Science Foundation (grant nos. H2022206598 and

H2024206106), 2024 Government Funded Clinical Medicine Excellent

Talent Training Project (grant nos. ZF2024099), Innovative Research

Team Support Program of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical

University (grant nos. 2023B09 and 2023C15) and S&T Program of

Hebei (grant no. 20377766D).

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data generated in the present study

may be found in the NCBI SRA database under accession number

PRJNA1256794 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1256794.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WG and LL contributed to the conception and design

of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation,

supervision of the experiments, and revision of the manuscript. JW

carried out the experiments, analyzed the data and drafted the

paper. FS and JL collected the data and prepared the tables and

figures. HX, XY and FL carried out the statistical analysis. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript. WG and LL confirm

the authenticity of all raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All animal experiments in the present study were

conducted in accordance with the Regulations for the Administration

of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals and relevant

institutional guidelines. The experiments were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Fourth

Hospital of Hebei Medical University (approval no. IACUC-4th Hos

Hebmu-2023001).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jin W, Huang K, Ding Z, Zhang M, Li C,

Yuan Z, Ma K and Ye X: Global, regional, and national burden of

esophageal cancer: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of

Disease Study 2021. Biomark Res. 13:32025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ilic I, Zivanovic Macuzic I, Ravic-Nikolic

A, Ilic M and Milicic V: Global burden of esophageal cancer and its

risk factors: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease

study 2019. Life (Basel). 15:242024.

|

|

3

|

Qi L, Sun M, Liu W, Zhang X, Yu Y, Tian Z,

Ni Z, Zheng R and Li Y: Global esophageal cancer epidemiology in

2022 and predictions for 2050: A comprehensive analysis and

projections based on GLOBOCAN data. Chin Med J (Engl).

137:3108–3116. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yokoyama A, Tsutsumi E, Imazeki H, Suwa Y,

Nakamura C, Mizukami T and Yokoyama T: Salivary acetaldehyde

concentration according to alcoholic beverage consumed and aldehyde

dehydrogenase-2 genotype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 32:1607–1614. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Prabhu A, Obi KO and Rubenstein JH: The

synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk

of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J

Gastroenterol. 109:822–827. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Blaydon DC, Etheridge SL, Risk JM, Hennies

HC, Gay LJ, Carroll R, Plagnol V, McRonald FE, Stevens HP, Spurr

NK, et al: RHBDF2 mutations are associated with tylosis, a familial

esophageal cancer syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 90:340–346. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ludmir EB, Stephens SJ, Palta M, Willett

CG and Czito BG: Human papillomavirus tumor infection in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 6:287–295. 2015.

|

|

8

|

Kato K, Ito Y, Nozaki I, Daiko H, Kojima

T, Yano M, Ueno M, Nakagawa S, Takagi M, Tsunoda S, et al:

Parallel-group controlled trial of surgery versus chemoradiotherapy

in patients with stage I esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

Gastroenterology. 161:1878–1886.e2. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Sun JM, Shen L, Shah MA, Enzinger P,

Adenis A, Doi T, Kojima T, Metges JP, Li Z, Kim SB, et al:

Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for

first-line treatment of advanced oesophageal cancer (KEYNOTE-590):

A randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet.

398:759–771. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Fan X, Wang J, Xia L, Qiu H, Tian Y,

Zhangcai Y, Luo X, Gao Y, Li C, Wu Y, et al: Efficacy of endoscopic

therapy for T1b esophageal cancer and construction of prognosis

prediction model: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg.

109:1708–1719. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Li Y, Li Y and Chen X: NOTCH and

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1287:59–68.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ron D and Walter P: Signal integration in

the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 8:519–529. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Grigoriadou C,

Pytel D, Zhang F, Ye J, Koumenis C, Cavener D and Diehl JA: PERK

promotes cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth by limiting

oxidative DNA damage. Oncogene. 29:3881–3895. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Urra H, Henriquez DR, Cánovas J,

Villarroel-Campos D, Carreras-Sureda A, Pulgar E, Molina E, Hazari

YM, Limia CM, Alvarez-Rojas S, et al: IRE1α governs cytoskeleton

remodelling and cell migration through a direct interaction with

filamin A. Nat Cell Biol. 20:942–953. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hart LS, Cunningham JT, Datta T, Dey S,

Tameire F, Lehman SL, Qiu B, Zhang H, Cerniglia G, Bi M, et al: ER

stress-mediated autophagy promotes Myc-dependent transformation and

tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 122:4621–4634. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Avivar-Valderas A, Salas E,

Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Nagi C, Debnath J and

Aguirre-Ghiso JA: PERK integrates autophagy and oxidative stress

responses to promote survival during extracellular matrix

detachment. Mol Cell Biol. 31:3616–3629. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Notte A, Rebucci M, Fransolet M, Roegiers

E, Genin M, Tellier C, Watillon K, Fattaccioli A, Arnould T and

Michiels C: Taxol-induced unfolded protein response activation in

breast cancer cells exposed to hypoxia: ATF4 activation regulates

autophagy and inhibits apoptosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 62:1–14.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lu M, Lawrence DA, Marsters S,

Acosta-Alvear D, Kimmig P, Mendez AS, Paton AW, Paton JC, Walter P

and Ashkenazi A: Opposing unfolded-protein-response signals

converge on death receptor 5 to control apoptosis. Science.

345:98–101. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Li G, Mongillo M, Chin KT, Harding H, Ron

D, Marks AR and Tabas I: Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of

inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic

reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 186:783–792. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Prieto K, Cao Y, Mohamed E, Trillo-Tinoco

J, Sierra RA, Urueña C, Sandoval TA, Fiorentino S, Rodriguez PC and

Barreto A: Polyphenol-rich extract induces apoptosis with

immunogenic markers in melanoma cells through the ER

stress-associated kinase PERK. Cell Death Discov. 5:1342019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Alfaro C, Sanmamed MF, Rodríguez-Ruiz ME,

Teijeira Á, Oñate C, González Á, Ponz M, Schalper KA, Pérez-Gracia

JL and Melero I: Interleukin-8 in cancer pathogenesis, treatment

and follow-up. Cancer Treat Rev. 60:24–31. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Raghuwanshi SK, Su Y, Singh V, Haynes K,

Richmond A and Richardson RM: The chemokine receptors CXCR1 and

CXCR2 couple to distinct G protein-coupled receptor kinases to

mediate and regulate leukocyte functions. J Immunol. 189:2824–2832.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shen T, Yang Z, Cheng X, Xiao Y, Yu K, Cai

X, Xia C and Li Y: CXCL8 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition

in colon cancer cells via the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway.

Oncol Rep. 37:2095–2100. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Liubomirski Y, Lerrer S, Meshel T,

Rubinstein-Achiasaf L, Morein D, Wiemann S, Körner C and Ben-Baruch

A: Tumor-stroma-inflammation networks promote pro-metastatic

chemokines and aggressiveness characteristics in triple-negative

breast cancer. Front Immunol. 10:7572019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhu YM, Webster SJ, Flower D and Woll PJ:

Interleukin-8/CXCL8 is a growth factor for human lung cancer cells.

Br J Cancer. 91:1970–1976. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yi M, Peng C, Xia B and Gan L: CXCL8

facilitates the survival and paclitaxel-resistance of

triple-negative breast cancers. Clin Breast Cancer. 22:e191–e198.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhai J, Shen J, Xie G, Wu J, He M, Gao L,

Zhang Y, Yao X and Shen L: Cancer-associated fibroblasts-derived

IL-8 mediates resistance to cisplatin in human gastric cancer.

Cancer Lett. 454:37–43. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Xue J, Song Y, Xu W and Zhu Y: The

CDK1-related lncRNA and CXCL8 mediated immune resistance in lung

adenocarcinoma. Cells. 11:26882022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhang H, Yu QL, Meng L, Huang H, Liu H,

Zhang N, Liu N, Yang J, Zhang YZ and Huang Q: TAZ-regulated

expression of IL-8 is involved in chemoresistance of hepatocellular

carcinoma cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 693:1085712020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Liu Q, Li A, Tian Y, Wu JD, Liu Y, Li T,

Chen Y, Han X and Wu K: The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 pathways in cancer.

Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 31:61–71. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ogura M, Takeuchi H, Kawakubo H, Nishi T,

Fukuda K, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, Wada N, Saikawa Y, Omori T, et

al: Clinical significance of CXCL-8/CXCR-2 network in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma. Surgery. 154:512–520. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hosono M, Koma YI, Takase N, Urakawa N,

Higashino N, Suemune K, Kodaira H, Nishio M, Shigeoka M, Kakeji Y

and Yokozaki H: CXCL8 derived from tumor-associated macrophages and

esophageal squamous cell carcinomas contributes to tumor

progression by promoting migration and invasion of cancer cells.

Oncotarget. 8:106071–106088. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hayakawa K, Nakajima S, Hiramatsu N,

Okamura M, Huang T, Saito Y, Tagawa Y, Tamai M, Takahashi S, Yao J

and Kitamura M: ER stress depresses NF-kappaB activation in

mesangial cells through preferential induction of C/EBP beta. J Am

Soc Nephrol. 21:73–81. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Knall C, Young S, Nick JA, Buhl AM,

Worthen GS and Johnson GL: Interleukin-8 regulation of the

Ras/Raf/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in human

neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 271:2832–2838. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Cheng GZ, Park S, Shu S, He L, Kong W,

Zhang W, Yuan Z, Wang LH and Cheng JQ: Advances of AKT pathway in

human oncogenesis and as a target for anti-cancer drug discovery.

Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 8:2–6. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Waugh DJJ and Wilson C: The interleukin-8

pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 14:6735–6741. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Cheng K and Hao M: Metformin inhibits

TGF-β1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via PKM2

relative-mTOR/p70s6k signaling pathway in cervical carcinoma cells.

Int J Mol Sci. 17:20002016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hetz C and Papa FR: The unfolded protein

response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 69:169–181. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

He J, Zhou Y and Sun L: Emerging

mechanisms of the unfolded protein response in therapeutic

resistance: From chemotherapy to Immunotherapy. Cell Commun Signal.

22:892024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Dong D, Ni M, Li J, Xiong S, Ye W, Virrey

JJ, Mao C, Ye R, Wang M, Pen L, et al: Critical role of the stress

chaperone GRP78/BiP in tumor proliferation, survival, and tumor

angiogenesis in transgene-induced mammary tumor development. Cancer

Res. 68:498–505. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Li J and Lee AS: Stress induction of

GRP78/BiP and its role in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 6:45–54. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Tan Y, Dourdin N, Wu C, De Veyra T, Elce

JS and Greer PA: Ubiquitous calpains promote caspase-12 and JNK

activation during endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J

Biol Chem. 281:16016–16024. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Yuan YJ, Liu S, Yang H, Xu JL, Zhai J,

Jiang HM and Sun B: Acetylshikonin induces apoptosis through the

endoplasmic reticulum stress-activated PERK/eIF2α/CHOP

axis in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med.

28:e180302024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Hetz C, Zhang K and Kaufman RJ:

Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein

response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:421–438. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Yin X, Zhang P, Xia N, Wu S, Liu B, Weng L

and Shang M: GPx8 regulates apoptosis and autophagy in esophageal

squamous cell carcinoma through the IRE1/JNK pathway. Cell Signal.

93:1103072022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Wang YM, Xu X, Tang J, Sun ZY, Fu YJ, Zhao

XJ, Ma XM and Ye Q: Apatinib induces endoplasmic reticulum

stress-mediated apoptosis and autophagy and potentiates cell

sensitivity to paclitaxel via the IRE-1α-AKT-mTOR pathway in

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Biosci. 11:1242021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mamik MK and Ghorpade A: Chemokine CXCL8

promotes HIV-1 replication in human monocyte-derived macrophages

and primary microglia via nuclear factor-κB pathway. PLoS One.

9:e921452014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Aarntzen EHJG, Hermsen R, Drenth JPH,

Boerman OC and Oyen WJG: 99mTc-CXCL8 SPECT to monitor disease

activity in inflammatory bowel disease. J Nucl Med. 57:398–403.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Amrouche L, Desbuissons G, Rabant M,

Sauvaget V, Nguyen C, Benon A, Barre P, Rabaté C, Lebreton X,

Gallazzini M, et al: MicroRNA-146a in human and experimental

ischemic AKI: CXCL8-dependent mechanism of action. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 28:479–493. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Barnes PJ: New treatments for chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 39:573–582.

2003.

|

|

52

|

Traves SL, Smith SJ, Barnes PJ and

Donnelly LE: Specific CXC but not CC chemokines cause elevated

monocyte migration in COPD: A role for CXCR2. J Leukoc Biol.

76:441–450. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Long X, Ye Y, Zhang L, Liu P, Yu W, Wei F,

Ren X and Yu J: IL-8, a novel messenger to cross-link inflammation

and tumor EMT via autocrine and paracrine pathways (Review). Int J

Oncol. 48:5–12. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Sheshadri N, Poria DK, Sharan S, Hu Y, Yan

C, Koparde VN, Balamurugan K and Sterneck E: PERK signaling through

C/EBPδ contributes to ER stress-induced expression of

immunomodulatory and tumor promoting chemokines by cancer cells.

Cell Death Dis. 12:10382021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Zhang L, Xu S, Cheng X, Wu J, Wang Y, Gao

W, Bao J and Yu H: Inflammatory tumor microenvironment of thyroid

cancer promotes cellular dedifferentiation and silencing of

iodide-handling genes expression. Pathol Res Pract. 246:1544952023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Püschel F, Favaro F, Redondo-Pedraza J,

Lucendo E, Iurlaro R, Marchetti S, Majem B, Eldering E, Nadal E,

Ricci JE, et al: Starvation and antimetabolic therapy promote

cytokine release and recruitment of immune cells. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 117:9932–9941. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

MacManus CF, Pettigrew J, Seaton A, Wilson

C, Maxwell PJ, Berlingeri S, Purcell C, McGurk M, Johnston PG and

Waugh DJJ: Interleukin-8 signaling promotes translational

regulation of cyclin D in androgen-independent prostate cancer

cells. Mol Cancer Res. 5:737–748. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Matsuo Y, Raimondo M, Woodward TA, Wallace

MB, Gill KR, Tong Z, Burdick MD, Yang Z, Strieter RM, Hoffman RM

and Guha S: CXC-chemokine/CXCR2 biological axis promotes

angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo in pancreatic cancer. Int J

Cancer. 125:1027–1037. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Wang J, Hu W, Wu X, Wang K, Yu J, Luo B,

Luo G, Wang W, Wang H, Li J and Wen J: CXCR1 promotes malignant

behavior of gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo in AKT and

ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Int J Oncol. 48:2184–2196. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Urbantat RM, Blank A, Kremenetskaia I,

Vajkoczy P, Acker G and Brandenburg S: The CXCL2/IL8/CXCR2 pathway

is relevant for brain tumor malignancy and endothelial cell

function. Int J Mol Sci. 22:26342021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Knall C, Worthen GS and Johnson GL:

Interleukin 8-stimulated phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase activity

regulates the migration of human neutrophils independent of

extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated

protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 94:3052–3057. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Luppi F, Longo AM, de Boer WI, Rabe KF and

Hiemstra PS: Interleukin-8 stimulates cell proliferation in

non-small cell lung cancer through epidermal growth factor receptor

transactivation. Lung Cancer. 56:25–33. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Brandl M, Seidler B, Haller F, Adamski J,

Schmid RM, Saur D and Schneider G: IKK(α) controls canonical

TGF(ß)-SMAD signaling to regulate genes expressing SNAIL and SLUG

during EMT in panc1 cells. J Cell Sci. 123:4231–4239. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Xiong M, Jiang L, Zhou Y, Qiu W, Fang L,

Tan R, Wen P and Yang J: The miR-200 family regulates

TGF-β1-induced renal tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition

through Smad pathway by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression. Am J

Physiol Renal Physiol. 302:F369–F379. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|