Introduction

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a critical

respiratory disease with notable implications for the survival and

long-term prognosis of preterm infants (1,2). It

is particularly prevalent among severely preterm infants

(gestational age <28 weeks) and infants of very low birth weight

(VLBW; birth weight <1,000 g) (3). In recent years, with advancements in

perinatal and neonatal medicine, there has been a marked increase

in the survival rate of preterm infants but the incidence of BPD

has increased accordingly. Notably, BPD is associated with elevated

mortality in the neonatal period, where surviving infants will

frequently develop persistent airway hyperresponsiveness and

abnormal lung function (4). These

sequelae contribute to a poor long-term prognosis, imposing burdens

on the quality of life of affected children.

The prevailing perspective on the etiology of BPD

attributes its development to a number of factors, such as

premature lung structural immaturity, elevated oxygen exposure,

mechanical ventilation-induced injury and infection (1,5).

However, emerging evidence has highlighted the important role of

intestinal dysbacteriosis in the pathogenesis and progression of

BPD. Gut microecology, defined as the microbial community of the

intestinal flora, comprises both symbiotic and pathogenic

microorganisms residing in the tissues and intestines. Dysbiosis of

the intestinal flora has been associated with immune dysregulation

and is associated with multisystemic diseases, including obesity,

diabetes, atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

(6,7). The lung microenvironment is likely to

be affected by changes in the gut microbiota, since microbiomes

also exist in the upper and lower respiratory tract. This notion is

supported by clinical observations where respiratory diseases also

present with concomitant gastrointestinal symptoms, whereas

gastrointestinal disorders are frequently accompanied by

respiratory manifestations (8,9).

Patients with influenza virus infection may exhibit

gastrointestinal symptoms (8),

whilst ~50% patients with inflammatory bowel disease, which is

characterized by alterations in gut microbiota composition, have

been reported to exhibit impaired lung function (9). This bidirectional crosstalk between

the intestines and lungs is referred to as the gut-lung axis, which

may provide novel insights into the pathophysiology of BPD.

The gut-lung axis has been shown to serve a notable

role in respiratory disease. Gut microecology evolves with age,

where infants with BPD are more prone to early-life gut dysbiosis

(10). A previous study showed

that in vaginally delivered preterm infants, the BPD group exhibits

increased relative abundance of Escherichia/Shigella and

decreased levels of Klebsiella and Salmonella in

their gut flora compared with those in the non-BPD group (10). Chen et al (11) documented that the intestinal flora

diversity in preterm infants with BPD was markedly lower compared

with that in controls at postnatal day 28. The gut-lung axis may

influence BPD development through immune cell migration, mucosal

immune disruption and alterations in gut-lung microenvironmental

cytokines.

Previous studies have explored alterations in the

intestinal flora of patients with BPD (10,11).

However, these studies remain fragmented, where a gap exists

between the theoretical framework of the gut-lung axis and the

clinical management of BPD. To address this, there is a pressing

need to synthesize existing research on the gut-lung axis and its

relationship with BPD, thereby enhancing strategies for disease

prognosis management. The present review systematically

consolidates advances in understanding the role of the gut-lung

axis in BPD pathogenesis, aiming to provide a robust theoretical

foundation for the development of targeted interventions.

Bidirectional communication in the gut-lung

axis

Similarities between the respiratory and

intestinal tracts

Embryonic developmental homology

During early embryonic development, the endoderm

gives rise to the pro-intestinal tube, which subsequently

differentiates into the foregut, midgut and hindgut. The foregut

further develops into the respiratory tract and upper digestive

tract, including the esophagus, stomach and duodenum, whilst the

midgut and hindgut form the remaining intestinal tract. This shared

embryonic origin from the endoderm-derived pro-intestinal tube

establishes the homology between the respiratory and intestinal

tracts (12–14).

Similar signaling pathways and

transcription factor regulatory networks

During development, the formation of the respiratory

and intestinal tracts is orchestrated by analogous signaling

pathways and transcription factors. The Wnt, Bmp and Fgf signaling

pathways are essential for modulating cell proliferation,

differentiation and migration, thereby ensuring the normal

development of the respiratory and intestinal tracts (15–17).

In addition, various transcription factors, such as Nkx2.1 and

Sox9, are pivotal in driving the development of both systems

(18–20). These factors regulate the

expression of key genes involved in organ morphogenesis,

underscoring their critical role in the coordinated development of

the respiratory and intestinal tracts. Collectively, these

signaling pathways and transcription factors highlight the shared

regulatory mechanisms between these two systems, providing insights

into their interrelated functions and potential shared

pathologies.

Structural and functional parallels

The respiratory and intestinal tracts exhibit

notable structural and functional parallels. Structurally, the

mucosa of both tracts belongs to the mucosal immune system and

comprises epithelium and lamina propria. They both feature a

luminal structure consisting of endoderm-derived epithelial cells,

which undergo comparable morphogenetic processes during

development, such as the establishment of epithelial cell polarity

and the formation of intercellular junctions (13). Functionally, both tracts are

essential for maintaining ventilation and material exchange to

support the normal physiological functions of the body, whilst also

being capable of producing secretory immunoglobulin A. These

structural and functional similarities underscore their homology in

embryonic histogenesis (21).

The extensive similarities between the respiratory

and intestinal tracts not only enhance the comprehension of their

interplay during physiological development, but also establish the

biological foundation for bidirectional communication within the

gut-lung axis. While acknowledging that structural homology alone

does not guarantee communication, we contend that the anatomical

and developmental parallels between respiratory and intestinal

tracts create a permissive biological framework for bidirectional

crosstalk. These parallels further offer insights into the

mechanisms underlying related diseases, providing a framework for

exploring pathophysiological connections between these systems

(22).

Intestinal microbiota: A foundation of

bidirectional communication in the gut-lung axis

The gut-lung axis displays dynamic bidirectional

crosstalk between the intestinal and pulmonary systems (21). Lung diseases have been previously

shown to impact intestinal function and vice versa (21,23–28).

Amongst the key elements facilitating this interaction is the

bacterial flora, which serves as a critical link between these two

systems (29). Accumulating

evidence has indicated that commensal bacteria residing in the gut

and lungs are indispensable for the development and maintenance of

immune homeostasis (30,31). These microbiota begin to colonize

newborns not only at birth but also during fetal development. A

previous study identified overlapping gut and lung microbiota in

human fetuses as early as 10–18 weeks of gestation (32). It has also been reported that gut

and lung microbiota can translocate between these organs through

fluid circulation, where metabolites derived from gut microbiota

can influence lung physiology through various immune-mediated

pathways (such as immune cell migration, mucosal immune disruption

and alterations in gut-lung microenvironmental cytokines) (33). The gut-lung axis therefore provides

a framework for understanding the interplay between local

microbiota and distal immune mechanisms, offering novel

perspectives on disease pathogenesis and progression. This

conceptual model not only improves the comprehension of the

physiological connections between the gut and lungs, but also

highlights potential therapeutic targets for disorders affecting

these interconnected systems.

Characteristics of intestinal microbiota in

preterm infants

The gut microbiota in early human life is dynamic,

gradually stabilizing to resemble adult profiles after the age of

2–3 years. The precise timing of the colonization of the gut by

bacteria remains controversial. It has previously been considered

that the fetus and placenta are sterile, but advances in testing

techniques (such as 16S ribosomal DNA-based and whole-genome

shotgun metagenomic studies) have enabled the identification of a

unique placental microbiome niche that is comprised of

non-pathogenic commensal microbiota (such as Firmicutes,

Tenericutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria

phyla) (34). Collado et

al (35) also previously

identified a unique bacterial community in the amniotic fluid

dominated by Proteobacteria and successfully cultured bacteria from

the placentas of healthy pregnant women. The observation that the

amniotic fluid and placenta have their own microbiota suggests the

potential for fetal colonization by bacteria during the

intrauterine environment, which may contribute to the maturation of

early immune cells (36). However,

contamination could not be ruled out as one of the causes of the

aforementioned phenomena (37,38).

Bacteria can be detected in the fetal stool of

preterm infants after birth (39).

Compared with healthy term infants, preterm infants tended to have

more Staphylococcaceae and delayed colonization by

Bifidobacteriaceae in their feces (40). The intestinal microbiota of preterm

infants does not have a specific ‘phenotype’ and develops in a

manner similar to that of healthy term infants, from

Gram-positive cocci to Enterobacteriaceae and then to

Bifidobacteriaceae (39,40).

The development of intestinal microbes in preterm infants is

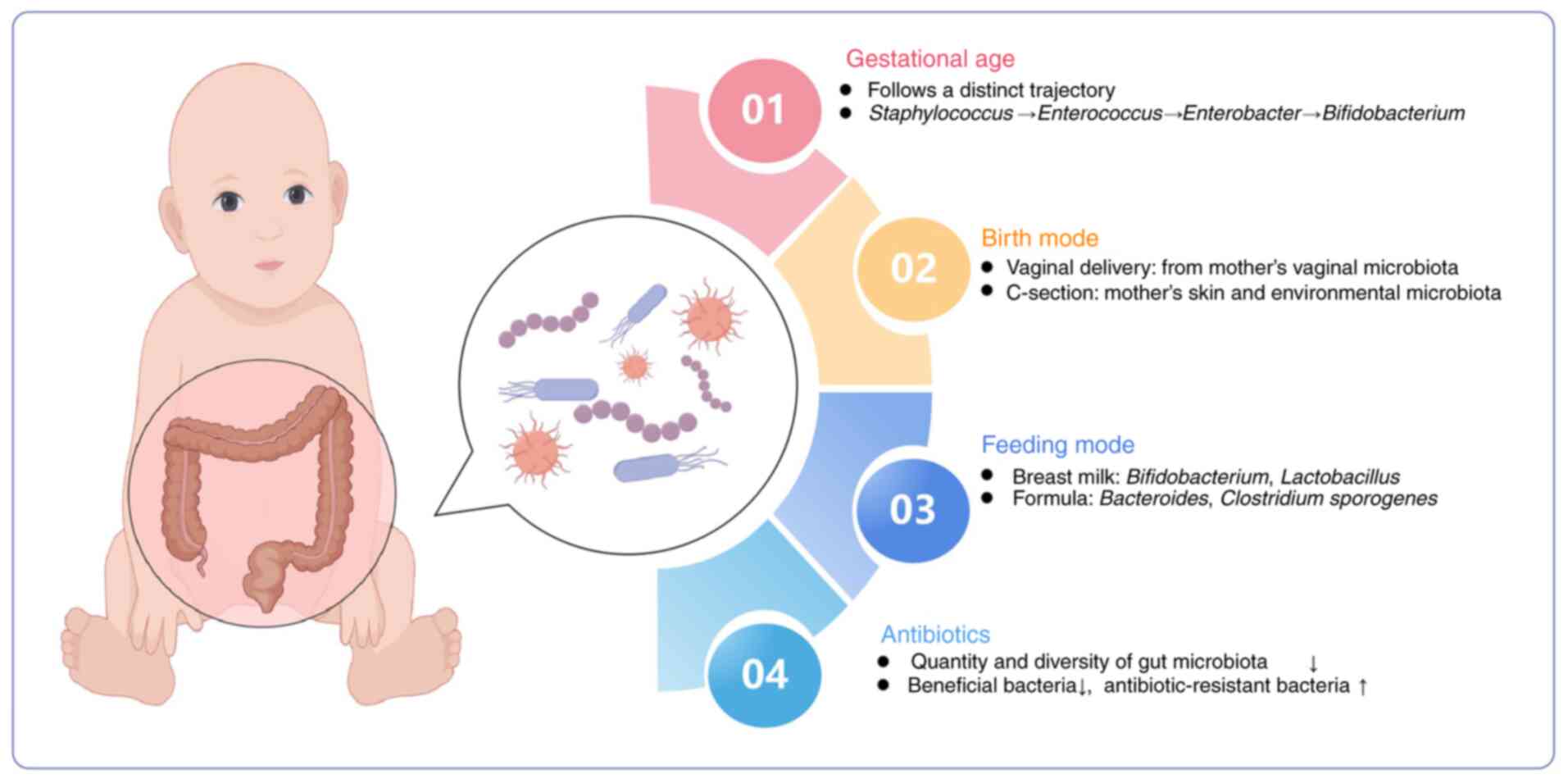

influenced by key perinatal factors, including gestational age,

delivery mode, feeding mode and the profile of antibiotics use

(Fig. 1).

Gestational age

In preterm neonates, gut microbiota development is

predominantly determined by gestational age. A previous study has

indicated that the gut microbiota of premature infants residing in

a tightly controlled microbial environment progresses through a

choreographed succession of bacterial classes from Bacilli

to Gammaproteobacteria to Clostridia (41). Antibiotics, vaginal vs. caesarian

birth, diet and age of the infants when sampled influence the pace,

but not the sequence of progression (41). Korpela et al (42) delineated four phases of gut

microbiota maturation in preterm infants, where the first three

phases are dominated by Staphylococcus, Enterococcus and

Enterobacter, then the fourth phase is characterized by the

prevalence of Bifidobacterium. This progression is closely

associated with postmenstrual age. Compared with term infants,

preterm neonates exhibit reduced gut microbiota diversity, increase

in conditionally pathogenic bacteria and delayed colonization by

beneficial species, such as Bifidobacteriaceae and

Bacteroidetes (43).

Birth mode

The intestinal microbiota of preterm infants

delivered vaginally is primarily sourced from the vaginal

microbiota of the mother, including Lactobacillus,

Prevotella and Sneathiella spp (44). By contrast, the gut microbiota of

preterm infants born through cesarean section (C-section) more

closely resembles the skin of the mother and the environmental

microbiota, which is predominantly comprised of Staphylococcus,

Corynebacterium and Propionibacterium spp. Notably, the

colonization of beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus,

Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides spp., is delayed in

infants delivered by C-section (44,45).

This disparity in gut microbiota composition between infants

delivered vaginally and by C-section diminishes at 4 and 12 months

after birth (45).

Feeding mode

Feeding practices notably influence the gut

microbiota composition of preterm infants, with breastfed infants

exhibiting greater microbial diversity. Breast milk is rich in

diverse microbiota and human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which

promote the growth of Bifidobacterium (46). Consequently, the gut of breastfed

preterm infants is predominantly colonized by

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, whereas

Bacteroides spp. and Clostridium sporogenes are more

prevalent in formula-fed infants (46). In particular, pasteurized donor

breastmilk has been shown to assist preterm infants in developing a

gut microbiota profile resembling that of breastfed healthy

neonates, accelerating the acquisition of microbial diversity

(47).

Antibiotics

Antibiotics can exert a profound impact on the gut

microbiota. Preterm infants frequently receive antibiotics for

extended durations during the perinatal period, longer than their

term counterparts. This prolonged exposure can markedly reduce the

quantity and diversity of gut microbiota, leading to a depletion of

beneficial bacteria (48). In

addition, extended antibiotic use is associated with increased

colonization by potentially pathogenic bacteria, such as

Escherichia coli, Shigella, Enterobacteriaceae and

Enterococcus, which may contribute to the emergence of

antibiotic-resistant bacteria (49).

Gut microbiota is integral to the health of preterm

infants, where it serves a key role in maintaining intestinal

immune homeostasis. A balanced symbiotic relationship between

commensal microbiota and the host is essential for establishing

effective immune defense and immune tolerance. Conversely,

dysbiosis of the gut microbiota can disrupt this delicate balance,

leading to immune system dysfunction and increasing the risk of

various morbidities in preterm infants (50).

The cause-and-effect of intestinal

microecology on BPD

BPD induces alterations in intestinal

microenvironment

BPD is a multifactorial and heterogeneous disease,

the pathogenesis of which is rooted in repeated injury to immature

lungs and aberrant repair processes triggered by a number of

factors, such as infection, mechanical ventilation and hyperoxia

(1,4). Maintaining a healthy gut microbiota

is crucial for immune homeostasis in preterm infants. Furthermore,

emerging evidence has indicated that both pulmonary and gut

microbiota are altered in infants with BPD (10,51).

Clinical studies have demonstrated that in preterm infants, the

progression of BPD is associated with dynamic changes in the

Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla and the Lactobacillus

genus within the lung microbiota, where that pulmonary dysbiosis

may exacerbate BPD severity (52,53).

Specifically, preterm infants with severe BPD exhibit more

pronounced changes in the respiratory microbiota, characterized by

reduced Staphylococcus and increased Ureaplasma

during early postnatal colonization (54,55).

The interaction between lung and gut microbiota is

bidirectional, with alterations in one able to influence the other.

This interplay is mediated through shared immune signaling

pathways, including cytokine signaling and Toll-like receptor (TLR)

activation, in addition to neuroendocrine pathways, such as the

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and vagus nerve-mediated

communication, which collectively impact respiratory and

gastrointestinal health. Previous studies have shown associations

between gut dysbiosis and changes in lung microbiota composition,

with reciprocal effects of lung microbiota perturbations on gut

health (56,57). Chen et al (11) divided preterm infants with a

gestational age of 26–32 weeks into a BPD and non-BPD group and

demonstrated that gut microbiota diversity was significantly

reduced in the BPD group compared with non-BPD group at postnatal

day 28. Furthermore, other clinical studies reported lower Shannon

diversity of the gut microbiota indices in infants with BPD, which

documented that the relative abundance of Proteobacteria was

elevated in the gut microbiota of the BPD group whereas the

abundance of the Firmicutes phylum was decreased, between postnatal

days 14 and 28 (54,58). To address confounding factors, such

as preterm birth and delivery mode, Lal et al (59) investigated the gut microbiota of

vaginally delivered preterm infants and revealed that BPD was

associated with increased relative abundance of Escherichia

coli and Shigella, with decreased levels of

Klebsiella and Salmonella in the gut microbiota

(10). These findings collectively

support the existence of intestinal dysbiosis in BPD, highlighting

the gut-lung axis as a potential therapeutic target for mitigating

disease progression.

Gut microecological disorders

contribute to BPD progression through the gut-lung axis

Infants with BPD exhibit disruptions in both the

respiratory and gut microbiota. This can influence BPD progression

by both regulating immune-related gene expression and inducing

systemic and intrapulmonary inflammatory responses (60). In a BPD mouse model,

antibiotic-induced intestinal commensal disruption during the

perinatal period promotes a more severe BPD phenotype,

characterized by increased lung fibrosis, vascular remodeling,

alveolar inflammation and higher rates of morbidity and mortality.

This was attributed to the disruption of intestinal commensal

bacterial colonization, highlighting the gut-pulmonary axis as a

key factor in BPD development (61).

Intestinal microecology disorders can promote BPD

progression through the gut-lung axis and the mechanisms may

include the following: i) Intestinal barrier disruption, where gut

dysbiosis can compromise the intestinal barrier, increasing

intestinal permeability to allow bacterial translocation to the

lungs. Additionally, dysbiosis-generated metabolites may trigger

immune cell activation, leading to local or systemic inflammation

and metabolic disturbances (62).

ii) Amplification of pulmonary inflammation, where gut dysbiosis

can exacerbate lung injury by promoting pulmonary inflammation. A

previous study indicated that TLRs can recognize

lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from gut bacteria, upregulating IL-1β

expression to activate NF-κB in a rodent model. This initiates an

inflammatory cascade to exacerbates lung injury (63). iii) Metabolic dysregulation, where

gut dysbiosis influences BPD development through various metabolic

pathways. Li et al (64)

determined that 129 differentiated metabolites were changed in

patients with BPD via metabolomics analysis, and a correlation

analysis revealed a remarkable relationship between gut microbiota

and metabolites. Other studies have shown that oral administration

of Lactobacillus plantarum L168 may play a protective role

in BPD by regulating the systemic metabolome, such as glutathione

metabolism and arachidonic acid metabolism (65). iv) Association with growth

restriction. Gut dysbiosis is strongly associated with growth

restriction and BPD in preterm infants. Given the critical role of

the gut microbiota in the extrauterine growth of VLBW infants and

the protective effects of nutritional support against BPD (66), modulating gut microbiota to improve

nutritional status may reduce BPD risk in preterm infants.

Compared with term infants, preterm infants have a

reduced diversity of gut microbial communities, where factors such

as exposure to hyperoxia, antibiotic exposure and nosocomial

infections, further disrupt microbial homeostasis. These

disruptions compromise the gut barrier, trigger inflammatory

responses, metabolic disorders and malnutrition, all of which

further impair lung tissue repair through the gut-lung axis,

ultimately accelerating the progression of BPD (53).

Unique mechanism of the gut-lung axis

in BPD

The core pathological feature of BPD in preterm

infants is the developmental arrest of immature lungs due to

injuries, such as hyperoxia and mechanical ventilation (1). The gut-lung axis may contribute to

BPD through the following mechanisms: i) Early disruption of gut

microbiota diversity, where both the gut and lungs of preterm

infants are immature. Prolonged hyperoxia inhibits the growth of

beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, increasing

pathogen abundance and causing dysbiosis. This dysbiosis can

intensify pulmonary inflammation and alveolar developmental

disorders by altering metabolites, including short-chain fatty

acids (SCFAs), trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), volatile organic

compounds (VOCs) and butyrate, as soon as impairing immune

regulation (67,68). BPD-related dysbiosis is

characterized by reduced biodiversity and the absence of specific

bacteria (such as Lactobacillus) (11,58).

By contrast, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)-associated lung injury

involves a complete gut microbiota collapse, with endotoxins

(including LPS) entering the circulation and triggering systemic

inflammation (69). ii)

Hyperoxia-induced microbiota-inflammation interactions. Hyperoxia

exposure induces alveolar epithelial cells damage in BPD,

simultaneously alters gut microbiota composition and promotes

bacterial translocation to the lungs. This process activates immune

and inflammatory pathways, releasing cytokines (such as IL22, IL6

and IL17) that inhibit alveolar development (60,61).

NEC-related lung injury, however, results from systemic

inflammation and sepsis caused by acute intestinal necrosis, rather

than the direct effects of hyperoxia (69,70).

Immunological modulation of the gut-lung

axis in BPD progression

Gut microbiota and its metabolites

mediate the pulmonary immune response through the gut-lung

axis

The neonatal immune response consists of both innate

and adaptive components. In preterm infants with an immature immune

system, airway and gut microbiota serve a crucial role in immune

development. The ‘intestinal microbiota translocation’ theory

posits that gut microbiota or bacterial products can directly

transfer to the lungs through the gut-lung axis, disrupting

pulmonary microecological balance. Additionally, gut microbial

metabolites entering the pulmonary circulation through systemic

circulation can stimulate lung immune cells, activating

inflammatory responses and inducing lung injury (71). Furthermore, these metabolites,

including SCFAs, can enter the bone marrow through the bloodstream,

promoting hematopoiesis and stimulating hematopoietic stem cell

differentiation (31). These cells

then migrate to the respiratory tract, modulating lung inflammation

in conjunction with the aforementioned mechanisms.

Gut microbiota

The gut barrier is a critical defensive system

within the gastrointestinal tract, preventing pathogen and

endotoxin invasion to avert inflammation and bacterial

translocation. Numerous factors, such as gestational age, feeding

practices and antibiotic use, can all disrupt the intestinal

microecological balance, affecting gut barrier maturation in

preterm infants (10). In neonates

with NEC, intestinal mucosal macrophages and immune cells clear the

majority of bacteria. However, surviving bacteria or their

inflammatory fragments can reach the lungs, activating alveolar

macrophages and causing lung injury (72). Gut-derived bacterial products,

including bacterial fragments and metabolites, can enter the

pulmonary circulation through the systemic circulation to stimulate

lung immune cells (such as macrophages, T cells and neutrophils) to

trigger inflammation (29).

Dickson et al (73)

previously detected live gut bacteria in the lungs of septic mouse

models and in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with

acute respiratory distress syndrome, suggesting that local or

systemic inflammation can mediate gut microbiota translocation,

disrupting lung microecological homeostasis. Intestinal

microecological imbalances can also increase gut permeability,

potentially allowing bacterial products to directly transfer to the

lungs and exacerbate pulmonary inflammation. Notably, recent

studies have drawn attention to the impact of strain-specific

microbiota (65,74). Shen et al (65) observed reduced lung injury and

improved lung development in BPD rats exposed to

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum L168. These results suggested

that L168 may improve BPD through downregulation of the

TLR4/NF-κB/Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 pathway (65). By contrast, although supplementing

Lactobacillus reuteri DSM17938 has been shown to improve

intestinal health, it has no notable therapeutic effects on BPD

(75). The differences between the

two suggest strain-specific microbiota effects.

Microbiota metabolites

Alterations in gut flora composition can impact

pulmonary immune function, with bacterial metabolites serving a key

role in gut-lung immune communication and potentially contributing

to BPD progression. SCFAs are essential gut microbiota metabolites

that exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by reducing immune cell

migration and adhesion and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokine

release. SCFAs can traverse the gut-lung axis to modulate pulmonary

immunity, with two primary immunomodulatory mechanisms suggested:

i) Driving anti-inflammatory responses through downstream effector

molecules; and ii) inhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity

to regulate immune responses. SCFAs can also promote

anti-inflammatory responses in extraintestinal organs, mitigating

airway inflammation. Low fecal acetic acid levels in preterm

infants have been associated with higher BPD incidence, whereas

acetic acid supplementation could reduce inflammation in mice with

hyperoxia-exposed BPD, decrease the proportion of

Escherichia-Shigella, increase the abundance of

Ruminococcus and attenuate lung injury, potentially

preventing neonatal BPD (76).

Other gut microbiota metabolites, such as TMAO and

VOCs, can also influence BPD pathology by reducing airway

inflammation and restoring epithelial function. Altered urinary

metabolites, including lactate, taurine, TMAO, inositol and

gluconate, have all been observed in infants with BPD (77). Specifically, alanine and betaine

levels are elevated whereas TMAO, lactate and glycine levels are

reduced in patients with BPD compared with those in non-BPD

controls (78). Notably, gut

microbiota can alter TMAO levels, and TMAO can activate

inflammation and induce oxidative stress, thereby modulating BPD

susceptibility (79). Fecal VOCs,

produced by intestinal flora during polysaccharide fermentation,

can influence lung function by altering the air-liquid interface

properties of pulmonary surfactants, stimulating pro-inflammatory

factor production and exacerbating oxidative stress. These effects

suggest a potential link between VOCs and BPD development (80). Previous studies have shown

associations between fecal VOC changes and BPD severity, where VOCs

have demonstrated potential for early BPD diagnosis and prediction

within the first 2 weeks of birth (81,82).

Furthermore, it has been shown that butyrate can enhance gene

expression (such as p16INK4a, p14ARF, and p15INK4b) by inhibiting

HDACs, thereby promoting histone acetylation and a more relaxed

chromatin structure (83,84). SCFAs can also influence DNA

methylation patterns by modulating DNA methyltransferases,

chromatin remodeling complexes, microRNAs and transcription factors

(85,86). However, the exact role of these

epigenetic mechanisms in BPD pathogenesis remains to be fully

clarified.

Gut microenvironment alters the levels

of pulmonary inflammation through the lung-gut axis

It has been previously demonstrated that the gut

microenvironment serves a crucial role in modulating pulmonary

immunity through the gut-lung axis. Gut microenvironment disruption

can lead to increased cytokines and inflammatory mediators, which

then spill over into the systemic circulation, driving lung

inflammation, disrupting the lung microenvironment and worsening

BPD. This process involves alterations in key inflammatory

pathways, including changes in IL-17, IL-22, IL-6 and TNF-α

signaling (87). Metabolites from

gut microbiota, such as polysaccharide A, α-galactosylceramide and

tryptophan metabolites, can activate proinflammatory factors,

including IL-17 and IL-22, triggering local or systemic

inflammation and immune dysfunction. Aberrant signaling from these

metabolites can alter the developing lungs, contributing to lung

disease (88). In neonatal mice

with BPD, T helper (Th)17 inflammatory responses are heightened in

the lung tissue, where neutralizing IL-17 with specific antibodies

can alleviate BPD-associated lung injury (89). Additionally, Lactobacillus

species degrade tryptophan to produce IL-22, which suppresses

immune responses and promotes regulatory T-cell development, in

turn protecting both gut and lung tissues (81). FMT has also shown promise in

mitigating acute lung injury in rats by reducing inflammatory cell

infiltration and lung interstitial exudation through downregulating

TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and TGF-β expression (90). These findings underscore the

influence of the gut microbiota on inflammatory mediator levels and

its subsequent impact on pulmonary pathology.

Immune cell migration-mediated mucosal

immunoregulatory mechanisms in the gut-lung axis

A primary communication pathway within the gut-lung

axis involves the migration of immune cells between the gut and

lungs, activating mucosal immunoregulatory mechanisms and

influencing BPD progression (91).

Certain intestinal mucosal immune cells, such as CD4+

and CD8+ cells, can reside in both the gut and lungs,

suggesting that mucosal immunity may constitute the immune network

between the lungs and the intestines (29). In BPD, lung inflammation involves

immune cell infiltration, some of which originate from the gut and

are activated by intestinal immune responses before migrating to

the lungs (91). Innate lymphoid

cells (ILCs) and dendritic cells (DCs) migrating along the gut-lung

axis may serve a notable role in BPD pathogenesis (92,93).

ILCs are widely distributed in the mucosa of the

intestine and respiratory tract, where they regulate immunity and

mucosal barrier homeostasis through cytokine secretion (92,94).

Gut ILCs can enter the bloodstream through the mesenteric lymphatic

system and migrate to the lungs, contributing to epithelial repair

(71). In neonatal mice with BPD,

type 2 ILCs (ILC2) numbers are elevated in the lung tissue and are

associated with alveolar differentiation arrest (92,94).

ILC2 depletion by anti-CD90.2 antibodies has been reported to

alleviate BPD-related lung injury (94). ILC2 can migrate from the intestine

to the lungs under the induction of IL-25 and participate in the

immune inflammatory response of the lungs (90). This was demonstrated in a previous

study where connecting the circulatory systems of two mice and

injecting IL-25 into one led to ILC2 migration from the gut of the

treated mouse to the lungs of both, exacerbating lung inflammation

(63). This suggests that

inflammatory stimulus may drive ILC2 recruitment to the lungs

through the gut-lung axis, impacting BPD pathogenesis, but the

exact molecular mechanisms require further investigation.

Type 3 ILCs (ILC3), a critical component of mucosal

immunity, serve an essential role in defending against lung

infections in preterm infants. A previous study showed that the

level of ILC3 expression is notably elevated in the lung tissue of

mice with BPD, promoting Th17 inflammatory responses and

exacerbating lung injury (89). In

preterm infants with NEC, gut mucosal DCs can recognize intestinal

dysbiosis, triggering ILC3 migration to the lungs of neonatal mice.

This disrupts pulmonary innate immunity and impairs type II

alveolar epithelial cell secretion of surfactants, leading to lung

injury (88). Gray et al

(93) previously demonstrated that

intestinal DCs can drive ILC3 migration to the lungs. Disrupting

postnatal bacterial colonization or selectively deleting DCs blocks

IL-22 and ILC3 migration, increasing susceptibility to

Streptococcus pneumoniae in neonatal mice (93). This highlights the role of

commensal gut bacteria in orchestrating pulmonary mucosal immunity,

crucial for lung defense system maturation. Disrupting ILC3

homeostasis in neonatal lungs may impair the pulmonary mucosal

defense system, raising the risk of respiratory infections and

inflammatory diseases, worsening BPD incidence and severity. Novel

insights into mucosal immunoregulation may offer promising avenues

for understanding BPD development, emphasizing the complex gut-lung

axis interactions. In conclusion, the present review discussed the

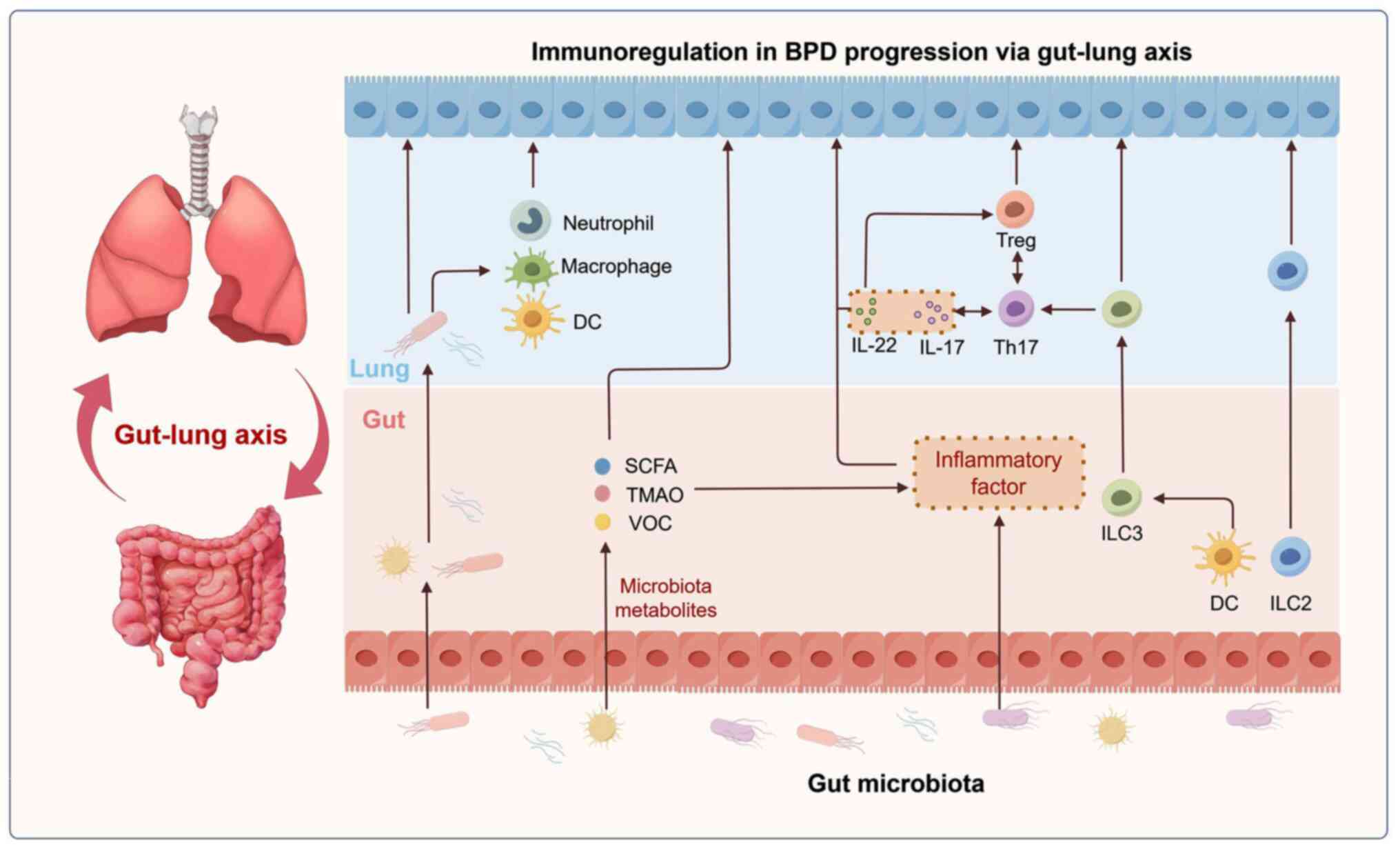

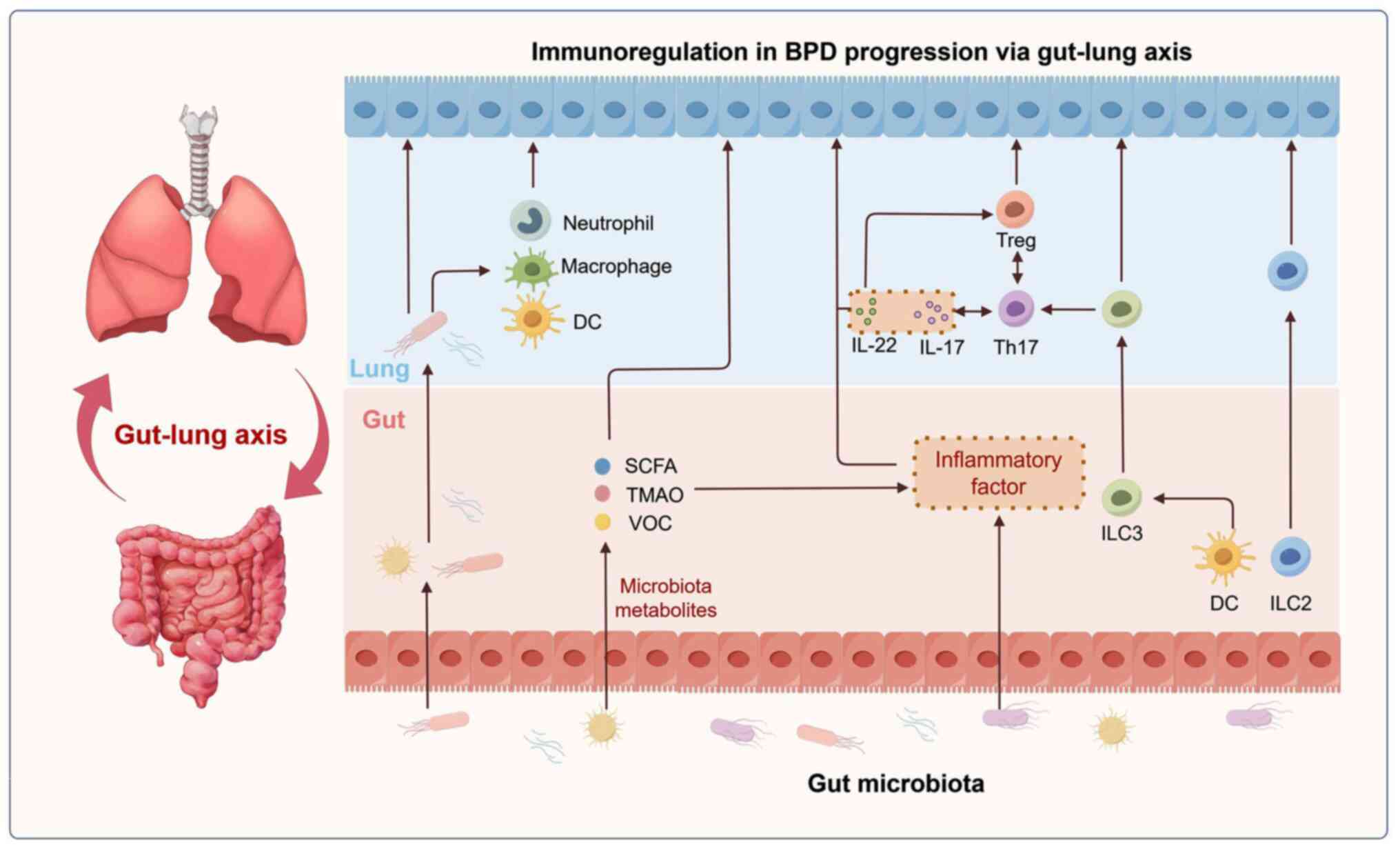

immunological modulation of the lung-gut axis in BPD (Fig. 2).

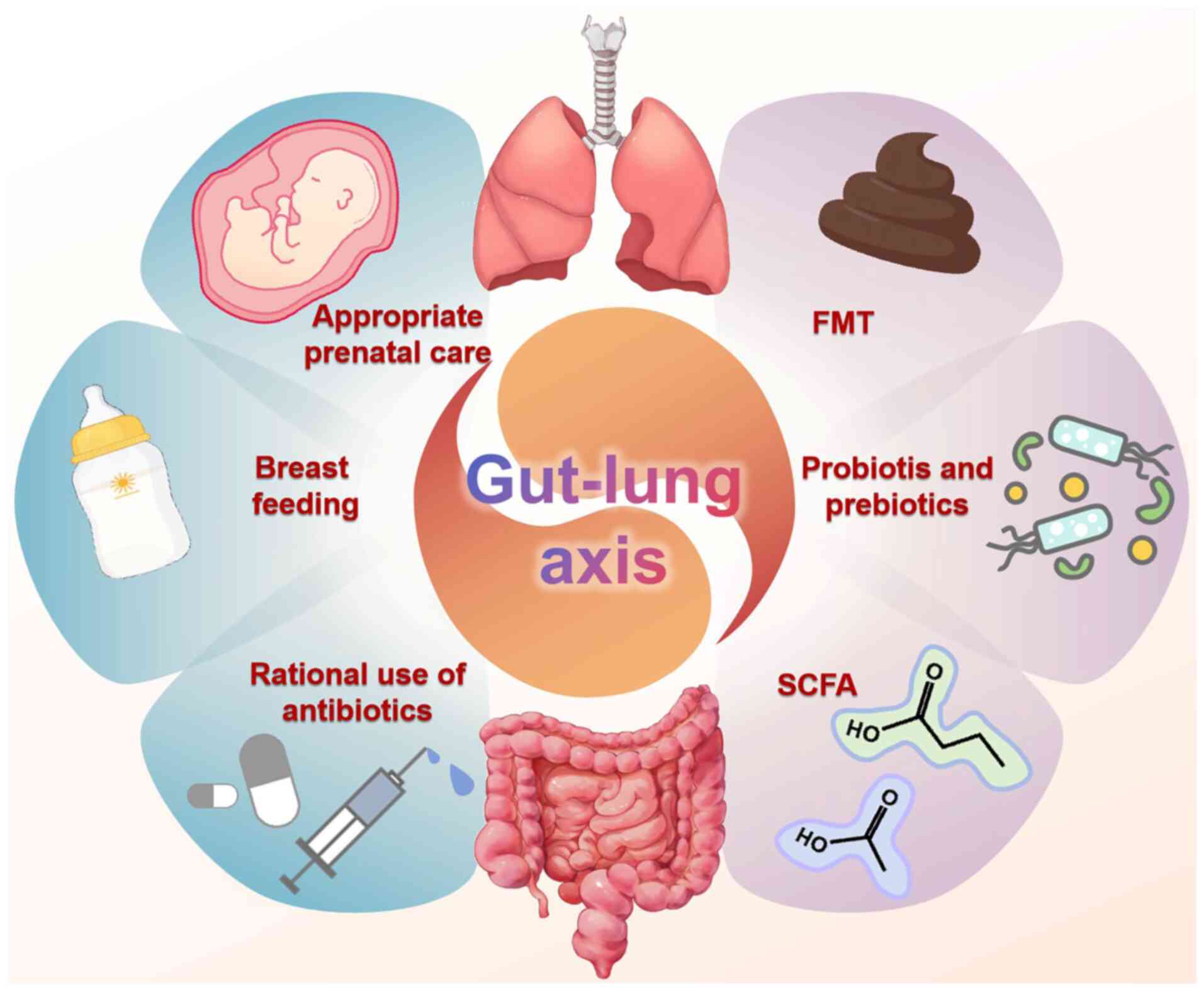

| Figure 2.Mechanism of the gut-lung axis in the

progression of BPD. The mechanism underlying immunological

modulation of the gut-lung axis in BPD includes: i) Gut microbiota

and its metabolites mediate the pulmonary immune response; ii) gut

microenvironment alters the level of pulmonary inflammation; and

iii) immune cell migration-mediated mucosal immunoregulatory

mechanisms. Figure drawn with Figdraw software 2.0 (ID: IRWIA45788,

www.figdraw.com; provided by Home for

Researchers, China). BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; DC, dendritic

cell; ICL2, type 2 ILCs; ILC3, type 3 ILCs; ICLs, innate lymphoid

cells; SCFA, short-chain fatty acid; Th, T helper; TMAO,

trimethylamine N-oxide; Treg, regulatory T cells; VOC, volatile

organic compound. |

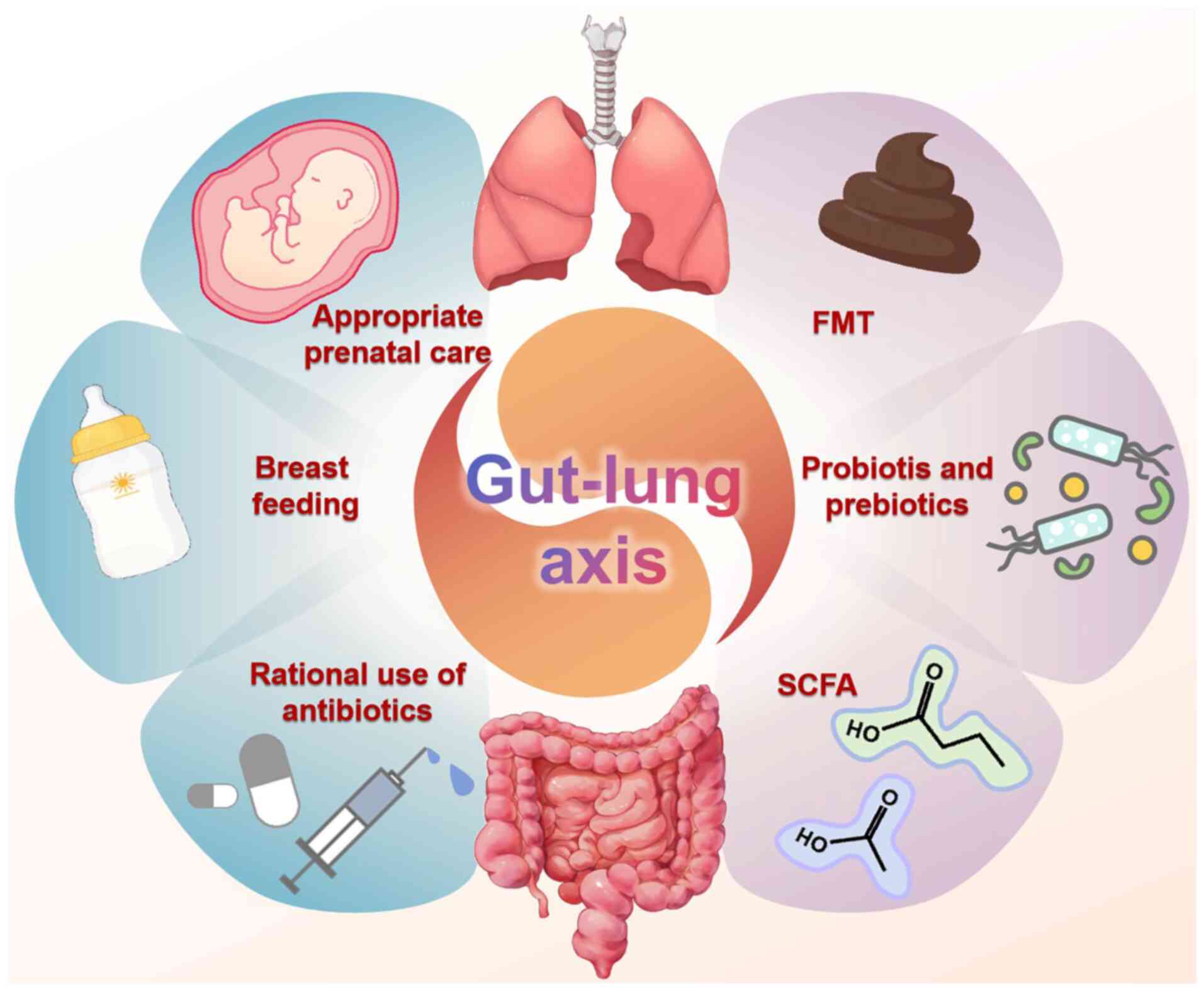

Emerging therapeutic approaches for BPD via

the gut-lung axis

The treatment implications of the gut microbiome in

BPD remain under investigation. However, several potential

treatment implications have emerged (Fig. 3). Probiotics offer a potential

approach to restoring the balance of gut microbiota, which in turn

can have a positive impact on lung health. Accumulating evidence

has suggested that specific probiotics may confer protection

against BPD and other respiratory conditions (e.g., asthma, COPD,

cystic fibrosis, lung cancer and respiratory infection). These

probiotics, such as Filamentous bacteria, Limosilactobacillus

reuteri and Bifidobacterium bifidum, achieve their

beneficial effects through immune modulation, reduction of

inflammation and the preservation of barrier integrity in both the

gut and lungs (94–96). Qu et al (97) previously investigated the effects

of Clostridium butyricum supplementation on extremely

preterm infants and found that probiotic-treated infants had lower

rates of BPD and invasive mechanical ventilation use, suggesting

that probiotics may be a notable factor influencing BPD risk (odds

ratio=0.034; 95% CI, 0.012–0.096). However, a meta-analysis by

Villamor-Martínez et al (98) found no significant effect of

probiotic supplementation on BPD risk. These contradictory results

should be interpreted cautiously and may stem from methodological

differences in randomized controlled trials, such as variations in

enrollment criteria, timing and dosing regimens. Additionally,

different probiotic strains, doses and formulations may yield

varying results. Future research should focus on optimizing

probiotic usage, including strain selection, dosing, timing and

administration methods, to understand their potential in BPD

management.

| Figure 3.Emerging therapeutic approaches for

BPD via the gut-lung axis. Several potential treatment implications

of the gut microbiome in BPD have emerged, including probiotics and

prebiotics, FMT, SCFA supplementation, avoiding premature birth,

breast feeding and the rational use of antibiotics. Figure drawn

with Figdraw software 2.0 (ID: TWPSObfadf, Obfadfwww.figdraw.com;

provided by Home for Researchers, China). BPD, bronchopulmonary

dysplasia; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; SCFA, short-chain

fatty acid. |

In addition to probiotics, prebiotics present

another avenue for influencing the gut microbiota. These

indigestible fibers can promote the growth of beneficial bacteria

in the gut (99). By incorporating

prebiotics (e.g. fructans, galactooligosaccharides,

xylooligosaccharides, chitooligosaccharides, lactulose, resistant

starch, polyphenols) as supplements, it is possible to affect

changes in the microbiota and their metabolites within both the

intestinal and pulmonary environments, potentially offering a novel

intervention strategy (98).

Furthermore, the direct administration of SCFAs has demonstrated

efficacy in regulating immune responses, preserving barrier

function and mitigating inflammatory processes in the gut and lungs

(99,100). SCFAs can be delivered through

various routes, including intranasal administration, in conjunction

with milk or through drinking water (98,99).

However, it is important to note that these findings have primarily

been observed in animal models and therefore require further

validation in clinical settings.

FMT represents another emerging therapeutic approach

that may influence lung health, by enhancing gut microbiota

diversity, reducing inflammation and modulating immune responses

(101). To the best of our

knowledge, FMT has not yet been investigated in the context of BPD,

which presents a promising area for future research. The

implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs in neonatal

intensive care units is therefore crucial at present. By optimizing

antibiotic use and minimizing unnecessary exposure, such programs

can help preserve the integrity of the gut microbiome and

potentially reduce the risk of BPD (102).

Gestational age is considered a pivotal factor in

influencing both microbiota composition and lung development.

Consequently, strengthening perinatal clinical care may be one of

the important means to prevent premature birth. For cases of

inevitable preterm birth, perinatal management strategies focused

on lung protection for preterm infants are particularly vital.

Breast milk has been shown to decrease the incidence of BPD, due to

its rich nutritional content and bioactive components, including

its microbial composition, exosomes and HMOs (46). Current optimal feeding strategies

emphasize the importance of promoting breastfeeding and fortifying

formula milk with HMOs (46).

Conclusions and prospects

The gut-lung axis, a bidirectional communication

pathway between the intestines and lungs, serves a pivotal role in

shaping the progression of BPD through alterations in the gut

microbiota and the immune microenvironment. Disruptions in

intestinal microecology are closely associated with pulmonary

pathogenesis. The gut-lung axis can influence the progression of

BPD through a range of mechanisms, such as bacterial translocation,

microbial metabolite exchange, inflammatory cytokine spillover and

immune cell migration. The present review delved into the role of

the gut-lung axis in BPD pathogenesis, including the bidirectional

communication of the gut-lung axis, the interplay between BPD and

gut microenvironmental changes and the immune regulatory mechanisms

of the gut-lung axis.

Emerging evidence from animal models and human

studies has suggested that FMT and probiotics may offer promising

therapeutic or preventive strategies for BPD. Additionally,

analyzing the microbial composition and metabolite profiles of

infants may enhance diagnostic accuracy and prognostic predictions

of BPD. However, research into the relationship between gut

microbiota and BPD remains in its infancy, with both progress and

limitations. Key limitations include: i) Small and heterogeneous

clinical samples, such that the majority of studies have small

sample sizes, where preterm infants vary greatly in gestational

age, birth weight and treatments (such as the duration of

mechanical ventilation), making results difficult to generalize

(11,52). ii) Limited microbiota analysis

methods, since the majority of existing studies use 16S rRNA

sequencing, which cannot detect strain-level differences or direct

metabolic effects (53,103). iii) Lack of longitudinal studies,

since the majority of previous studies focused on short-term

postnatal microbiota changes (52,104). However, the pathological process

of BPD can last months, where long-term microbiota dynamics data

remain scarce. A number of previous animal studies have explored

the relationship between gut microbiota and BPD. However, animal

experiments have difficulties in extrapolation of findings from

animal studies to humans, specifically regarding model

construction, physiological differences, microbiota complexity and

clinical transformation, as follows: i) Physiological differences,

where animal models differ physiologically from human preterm

infants, particularly in developmental staging and immune system

maturity (105,106). ii) Species-specific gut

microbiota, where gut microbiota composition and metabolites vary

by species. Differences exist in colonization patterns, strain

functions, metabolic pathways and pathogen virulence (107,108). iii) Clinical translation

barriers, where challenges remain in clinical translation, such as

determining administration methods and assessing safety. Although

FMT has shown promise in animal studies, its safety in

immunocompromised preterm infants requires further evaluation.

Research on the relationship between gut microbiota

in preterm infants and BPD remains in its early stages. The present

study reviewed the role of the lung-gut axis in BPD in recent years

through a qualitative synthesis. However, the cited evidence has

limitations, as follows: i) Uncontrolled confounders, such that the

majority of animal models failed to simulate concurrent nutritional

deprivation in preterm infants; ii) measurement bias, where 16S

rRNA sequencing in the vast majority of clinical studies could not

resolve strain-specific functions (such as commensal vs. pathogenic

E. coli); and iii) Generalizability, since the majority of

included cohorts were single-center with limited ethnic diversity.

By contrast, a meta-analysis would provide quantitative estimates

of the gut-lung axis mechanisms in BPD and strengthen the evidence

synthesis. However, a meta-analysis of the studies may have the

following methodological and scope-related limitations: i) The

available clinical studies exhibited substantial heterogeneity in

patient populations [including varying gestational ages (24–32

weeks), birth weights (500–1,500 g)], intervention protocols

(probiotic strains, dosing regimens) and outcome measures (BPD

diagnostic criteria ranging from National Institutes of Health 2001

to 2018 consensuses). Such heterogeneity would compromise the

validity of pooled effect estimates. ii) A meta-analysis is

typically suited for interventional trials with dichotomous

outcomes (such as BPD incidence), whereas the present review

focused on mechanistic pathways (such as immune cell migration,

SCFA-induced epigenetic regulation) primarily derived from animal

and in vitro studies, which cannot be meaningfully

quantified by statistical pooling. iii) Critical data required for

meta-analysis (including standard deviations of microbial abundance

and exact cytokine levels) are rarely reported in mechanistic

studies. Future large-scale, standardized cohorts are needed to

enable meta-analyses of gut microbiota signatures in BPD.

The present review systematically consolidated

advances in understanding the role of the gut-lung axis in BPD

pathogenesis and demonstrates advantages over similar reviews in

the following key areas (93,109): i) Focused mechanistic depth on

the gut-lung axis. The present study systematically focused on the

bidirectional causal relationship between intestinal dysbiosis and

the progression of BPD. In addition, by comparing the gut-lung axis

mechanisms in BPD with those in NEC-related lung injury, the

BPD-specific mechanisms were highlighted, which is rarely presented

in similar reviews (93,109). ii) Integration of developmental

immunology. The present review established the fundamental

biological basis of the gut-lung axis by detailing the shared

embryonic origin (endoderm), signaling pathways (Wnt/Bmp/Fgf) and

transcription factors (Nkx2.1/Sox9). The review also clarified the

immunomodulatory role of the gut-lung axis in BPD, a mechanism that

is rarely covered in similar reviews (59,109). iii) Critical appraisal of

therapeutics. The current review discussed the contradictory

clinical evidence of probiotics, avoiding overgeneralization.

Furthermore, the possibility of emerging therapeutic applications

(FMT, SCFA supplementation and prebiotics) was explored, whilst

acknowledging the translation gap from animals to humans. iv)

Methodological rigor and transparency. The present review clearly

outlined the shortcomings of the existing clinical studies (such as

small heterogeneous cohorts, limitations of 16S rRNA sequencing and

lack of longitudinal data). Furthermore, it was clearly explained

as to why the performance of a meta-analysis was inappropriate

(heterogeneity, mechanism focus and missing data), enhancing

academic credibility. In the future, further elucidation of the

role of the gut-lung axis in BPD is essential to uncover novel

patho-mechanistic insights and therapeutic targets. The present

study may facilitate a more integrated approach to BPD prevention,

management and prognosis, ultimately improving the quality of life

for affected patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present review was supported by the Graduate Student

Research and Creative Projects of Jiangsu Province (grant no.

KYCX21-3402) and the Excellent PhD Engineering Program of

Children's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (grant no.

BSYC2024004).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

YZ was involved in the conception of the study, the

formulation of overarching study aims, manuscript preparation and

article revision. RDD contributed by preparing the manuscript,

specifically its critical review, commentary and revision. Data

authentication is not applicable. Both authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dankhara N, Holla I, Ramarao S and

Kalikkot Thekkeveedu R: Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Pathogenesis

and pathophysiology. J Clin Med. 12:42072023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Collaco JM and McGrath-Morrow SA:

Long-term outcomes of infants with severe BPD. Semin Perinatol.

48:1518912024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gilfillan M, Bhandari A and Bhandari V:

Diagnosis and management of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. BMJ.

375:n19742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Shukla VV and Ambalavanan N: Recent

advances in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Indian J Pediatr.

88:690–695. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chen X, Yuan L, Jiang S, Gu X, Lei X, Hu

L, Xiao T, Zhu Y, Dang D, Li W, et al: Synergistic effects of

achieving perinatal interventions on bronchopulmonary dysplasia in

preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr. 183:1711–1721. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lu D, Huang Y, Kong Y, Tao T and Zhu X:

Gut microecology: Why our microbes could be key to our health.

Biomed Pharmacother. 131:1107842020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Wang H, Zheng Y, Yang M, Wang L, Xu Y, You

S, Mao N, Fan J and Ren S: Gut microecology: Effective targets for

natural products to modulate uric acid metabolism. Front Pharmacol.

15:14467762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gu S, Chen Y, Wu Z, Chen Y, Gao H, Lv L,

Guo F, Zhang X, Luo R, Huang C, et al: Alterations of the gut

microbiota in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 or H1N1

influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 71:2669–2678. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Raftery AL, Tsantikos E, Harris NL and

Hibbs ML: Links between inflammatory bowel disease and chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease. Front Immunol. 11:21442020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ryan FJ, Drew DP, Douglas C, Leong LEX,

Moldovan M, Lynn M, Fink N, Sribnaia A, Penttila I, McPhee AJ, et

al: Changes in the composition of the gut microbiota and the blood

transcriptome in preterm infants at less than 29 weeks gestation

diagnosed with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. mSystems. 4:e00484–19.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen SM, Lin CP and Jan MS: Early gut

microbiota changes in preterm infants with bronchopulmonary

dysplasia: A pilot Case-control study. Am J Perinatol.

38:1142–1149. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zhao L, Song W and Chen YG:

Mesenchymal-epithelial interaction regulates gastrointestinal tract

development in mouse embryos. Cell Rep. 40:1110532022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Batki J, Hetzel S, Schifferl D, Bolondi A,

Walther M, Wittler L, Grosswendt S, Herrmann BG and Meissner A:

Extraembryonic gut endoderm cells undergo programmed cell death

during development. Nat Cell Biol. 26:868–877. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Fang Y and Li X: Metabolic and epigenetic

regulation of endoderm differentiation. Trends Cell Biol.

32:151–164. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Aros CJ, Pantoja CJ and Gomperts BN: Wnt

signaling in lung development, regeneration, and disease

progression. Commun Biol. 4:6012021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Aspal M and Zemans RL: Mechanisms of

ATII-to-ATI cell differentiation during lung regeneration. Int J

Mol Sci. 21:31882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yang J, Wang J, Ding B, Jiang Z, Yu F, Li

D, Sun W, Wang L, Xu H and Hu S: Feedback delivery of BMP 7 on the

pathological oxidative stress via smart hyaluronic acid hydrogel

potentiated the repairing of the gut epithelial integrity. Int J

Biol Macromol. 282:1367942024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Herriges MJ, Tischfield DJ, Cui Z, Morley

MP, Han Y, Babu A, Li S, Lu M, Cendan I, Garcia BA, et al: The

NANCI-Nkx2.1 gene duplex buffers Nkx2.1 expression to maintain lung

development and homeostasis. Genes Dev. 31:889–903. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chelladurai P, Kuenne C, Bourgeois A,

Günther S, Valasarajan C, Cherian AV, Rottier RJ, Romanet C,

Weigert A, Boucherat O, et al: Epigenetic reactivation of

transcriptional programs orchestrating fetal lung development in

human pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med. 14:eabe54072022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Dolmatov IY, Kalacheva NV, Tkacheva ES,

Shulga AP, Zavalnaya EG, Shamshurina EV, Girich AS, Boyko AV and

Eliseikina MG: Expression of Piwi, MMP, TIMP, and Sox during Gut

Regeneration in Holothurian Eupentacta fraudatrix (Holothuroidea,

Dendrochirotida). Genes (Basel). 12:12922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DL, Cooper

MA, Morrison M, Hugenholtz P and Hansbro PM: Emerging pathogenic

links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol.

15:55–63. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Thursby E and Juge N: Introduction to the

human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 474:1823–1836. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Keely S, Talley NJ and Hansbro PM:

Pulmonary-intestinal cross-talk in mucosal inflammatory disease.

Mucosal Immunol. 5:7–18. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Keely S and Hansbro PM: Lung-gut cross

talk: A potential mechanism for intestinal dysfunction in patients

with COPD. Chest. 145:199–200. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu G, Mateer SW, Hsu A, Goggins BJ, Tay

H, Mathe A, Fan K, Neal R, Bruce J, Burns G, et al: Platelet

activating factor receptor regulates Colitis-induced pulmonary

inflammation through the NLRP3 inflammasome. Mucosal Immunol.

12:862–873. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Fricker M, Goggins BJ, Mateer S, Jones B,

Kim RY, Gellatly SL, Jarnicki AG, Powell N, Oliver BG,

Radford-Smith G, et al: Chronic cigarette smoke exposure induces

systemic hypoxia that drives intestinal dysfunction. JCI Insight.

3:e940402018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mateer SW, Maltby S, Marks E, Foster PS,

Horvat JC, Hansbro PM and Keely S: Potential mechanisms regulating

pulmonary pathology in inflammatory bowel disease. J Leukoc Biol.

98:727–737. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mateer SW, Mathe A, Bruce J, Liu G, Maltby

S, Fricker M, Goggins BJ, Tay HL, Marks E, Burns G, et al: IL-6

drives Neutrophil-mediated pulmonary inflammation associated with

bacteremia in murine models of colitis. Am J Pathol. 188:1625–1639.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Anand S and Mande SS: Diet, microbiota and

gut-lung connection. Front Microbiol. 9:21472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Marsland BJ, Trompette A and Gollwitzer

ES: The Gut-lung axis in respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 12

(Suppl 2):S150–S56. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dang AT and Marsland BJ: Microbes,

metabolites, and the gut-lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. 12:843–850.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Al Alam D, Danopoulos S, Grubbs B, Ali N,

MacAogain M, Chotirmall SH, Warburton D, Gaggar A, Ambalavanan N

and Lal CV: human fetal lungs harbor a microbiome signature. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med. 201:1002–1006. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chakradhar S: A curious connection:

Teasing apart the link between gut microbes and lung disease. Nat

Med. 23:402–404. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Aagaard K, Ma J, Antony KM, Ganu R,

Petrosino J and Versalovic J: The placenta harbors a unique

microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 6:237–265. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Collado MC, Rautava S, Aakko J, Isolauri E

and Salminen S: Human gut colonisation may be initiated in utero by

distinct microbial communities in the placenta and amniotic fluid.

Sci Rep. 6:231292016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ortiz Moyano R, Raya Tonetti F, Tomokiyo

M, Kanmani P, Vizoso-Pinto MG, Kim H, Quilodrán-Vega S, Melnikov V,

Alvarez S, Takahashi H, et al: The ability of respiratory commensal

bacteria to beneficially modulate the lung innate immune response

is a strain dependent characteristic. Microorganisms. 8:7272020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Leiby JS, McCormick K, Sherrill-Mix S,

Clarke EL, Kessler LR, Taylor LJ, Hofstaedter CE, Roche AM, Mattei

LM, Bittinger K, et al: Lack of detection of a human placenta

microbiome in samples from preterm and term deliveries. Microbiome.

6:1962018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

de Goffau MC, Lager S, Sovio U, Gaccioli

F, Cook E, Peacock SJ, Parkhill J, Charnock-Jones DS and Smith GCS:

Human placenta has no microbiome but can contain potential

pathogens. Nature. 572:329–334. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tauchi H, Yahagi K, Yamauchi T, Hara T,

Yamaoka R, Tsukuda N, Watanabe Y, Tajima S, Ochi F, Iwata H, et al:

Gut microbiota development of preterm infants hospitalised in

intensive care units. Benef Microbes. 10:641–651. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Guittar J, Shade A and Litchman E:

Trait-based community assembly and succession of the infant gut

microbiome. Nat Commun. 10:5122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

La Rosa PS, Warner BB, Zhou Y, Weinstock

GM, Sodergren E, Hall-Moore CM, Stevens HJ, Bennett WE Jr, Shaikh

N, Linneman LA, et al: Patterned progression of bacterial

populations in the premature infant gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:12522–12527. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Korpela K, Blakstad EW, Moltu SJ, Strømmen

K, Nakstad B, Rønnestad AE, Brække K, Iversen PO, Drevon CA and de

Vos W: Intestinal microbiota development and gestational age in

preterm neonates. Sci Rep. 8:24532018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bresesti I, Salvatore S, Valetti G, Baj A,

Giaroni C and Agosti M: The Microbiota-gut axis in premature

infants: Physio-pathological implications. Cells. 11:3792022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O'Brien JL,

Hutchinson DS, Smith DP, Wong MC, Ross MC, Lloyd RE, Doddapaneni H,

Metcalf GA, et al: Temporal development of the gut microbiome in

early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature. 562:583–588. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia

H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Li Y, Xia Y, Xie H, Zhong H, et al:

Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the

first year of life. Cell Host Microbe. 17:690–703. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lyons KE, Ryan CA, Dempsey EM, Ross RP and

Stanton C: Breast milk, a source of beneficial microbes and

associated benefits for infant health. Nutrients. 12:10392020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Quigley M, Embleton ND and McGuire W:

Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth

weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

6:CD0029712018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Aguilar-Lopez M, Dinsmoor AM, Ho TTB and

Donovan SM: A systematic review of the factors influencing

microbial colonization of the preterm infant gut. Gut Microbes.

13:1–33. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ramirez J, Guarner F, Bustos Fernandez L,

Maruy A, Sdepanian VL and Cohen H: Antibiotics as major disruptors

of gut microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 10:5729122020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kalbermatter C, Fernandez Trigo N,

Christensen S and Ganal-Vonarburg SC: Maternal microbiota, early

life colonization and breast milk drive immune development in the

newborn. Front Immunol. 12:6830222021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Colombo SFG, Nava C, Castoldi F, Fabiano

V, Meneghin F, Lista G and Cavigioli F: Preterm Infants' Airway

microbiome: A scoping review of the current evidence. Nutrients.

16:4652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Lohmann P, Luna RA, Hollister EB, Devaraj

S, Mistretta TA, Welty SE and Versalovic J: The airway microbiome

of intubated premature infants: Characteristics and changes that

predict the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Res.

76:294–301. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Pammi M, Lal CV, Wagner BD, Mourani PM,

Lohmann P, Luna RA, Sisson A, Shivanna B, Hollister EB, Abman SH,

et al: Airway microbiome and development of bronchopulmonary

dysplasia in preterm infants: A systematic review. J Pediatr.

204:126–133.e2. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Sun T, Yu H and Fu J: Respiratory tract

microecology and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants.

Front Pediatr. 9:7625452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Chen X, Huang X, Lin Y, Lin B and Yang C,

Huang Z and Yang C: Association of Ureaplasma infection pattern and

azithromycin treatment effect with bronchopulmonary dysplasia in

Ureaplasma positive infants: A cohort study. BMC Pulm Med.

23:2292023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Chung KF and Adcock IM: Multifaceted

mechanisms in COPD: Inflammation, immunity, and tissue repair and

destruction. Eur Respir J. 31:1334–1356. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Song Z, Meng Y, Fricker M, Li X, Tian H,

Tan Y and Qin L: The role of gut-lung axis in COPD: Pathogenesis,

immune response, and prospective treatment. Heliyon. 10:e306122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang Z, Jiang J, Li Z and Wan W: The

change of cytokines and gut microbiome in preterm infants for

bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front Microbiol. 13:8048872022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Lal CV, Kandasamy J, Dolma K, Ramani M,

Kumar R, Wilson L, Aghai Z, Barnes S, Blalock JE, Gaggar A, et al:

Early airway microbial metagenomic and metabolomic signatures are

associated with development of severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 315:L810–L815. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Yang K and Dong W: Perspectives on

probiotics and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front Pediatr.

8:5702472020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Willis KA, Siefker DT, Aziz MM, White CT,

Mussarat N, Gomes CK, Bajwa A, Pierre JF, Cormier SA and Talati AJ:

Perinatal maternal antibiotic exposure augments lung injury in

offspring in experimental bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol

Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 318:L407–L418. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Enaud R, Prevel R, Ciarlo E, Beaufils F,

Wieërs G, Guery B and Delhaes L: The Gut-lung axis in health and

respiratory diseases: A place for inter-organ and inter-kingdom

crosstalks. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 10:92020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Wedgwood S, Gerard K, Halloran K,

Hanhauser A, Monacelli S, Warford C, Thai PN, Chiamvimonvat N,

Lakshminrusimha S, Steinhorn RH and Underwood MA: Intestinal

dysbiosis and the developing lung: The role of toll-like receptor 4

in the gut-lung axis. Front Immunol. 11:3572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Li Y, He L, Zhao Q and Bo T: Microbial and

metabolic profiles of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and therapeutic

effects of potential probiotics Limosilactobacillus reuteri and

Bifidobacterium bifidum. J Appl Microbiol. 133:908–921. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Shen X, Yang Z, Wang Q, Chen X, Zhu Q, Liu

Z, Patel N, Liu X and Mo X: Lactobacillus plantarum L168 improves

hyperoxia-induced pulmonary inflammation and hypoalveolarization in

a rat model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. NPJ Biofilms

Microbiomes. 10:442024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Underwood MA, Lakshminrusimha S, Steinhorn

RH and Wedgwood S: Malnutrition, poor post-natal growth, intestinal

dysbiosis and the developing lung. J Perinatol. 41:1797–1810. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Ding J, Xu J, Wu H, Li M, Xiao Y, Fu J,

Zhu X, Wu N, Sun Q and Liu Y: The cross-talk between the metabolome

and microbiome in a double-hit neonatal rat model of

bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Genomics. 117:1109692025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Thatrimontrichai A, Praditaukrit M,

Maneenil G, Dissaneevate S, Singkhamanan K and Surachat K:

Characterization of gut microbiota in very low birth weight infants

with versus without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin Exp Pediatr.

68:503–511. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Sodhi CP, Gonzalez Salazar AJ, Kovler ML,

Fulton WB, Yamaguchi Y, Ishiyama A, Wang S, Prindle T Jr, Vurma M,

Das T, et al: The administration of a pre-digested fat-enriched

formula prevents necrotising enterocolitis-induced lung injury in

mice. Br J Nutr. 128:1050–1063. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Jia H, Sodhi CP, Yamaguchi Y, Lu P, Martin

LY, Good M, Zhou Q, Sung J, Fulton WB, Nino DF, et al: Pulmonary

epithelial TLR4 activation leads to lung injury in neonatal

necrotizing enterocolitis. J Immunol. 197:859–871. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Tan JY, Tang YC and Huang J: Gut

microbiota and lung injury. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1238:55–72. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Samuelson DR, Welsh DA and Shellito JE:

Regulation of lung immunity and host defense by the intestinal

microbiota. Front Microbiol. 6:10852015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Dickson RP, Singer BH, Newstead MW,

Falkowski NR, Erb-Downward JR, Standiford TJ and Huffnagle GB:

Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and

the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Microbiol.

1:161132016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Moreno-Villares JM, Andrade-Platas D,

Soria-López M, Colomé-Rivero G, Catalan Lamban A, Martinez-Figueroa

MG, Espadaler-Mazo J and Valverde-Molina J: Comparative efficacy of

probiotic mixture Bifidobacterium longum KABP042 plus Pediococcus

pentosaceus KABP041 vs. Limosilactobacillus reuteri DSM17938 in the

management of infant colic: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J

Pediatr. 183:5371–5381. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Spreckels JE, Wejryd E, Marchini G,

Jonsson B, de Vries DH, Jenmalm MC, Landberg E, Sverremark-Ekström

E, Martí M and Abrahamsson T: Lactobacillus reuteri

Colonisation of extremely preterm infants in a randomised

Placebo-controlled trial. Microorganisms. 9:9152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zhang Q, Ran X, He Y, Ai Q and Shi Y:

Acetate downregulates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes and

attenuates lung injury in neonatal mice with bronchopulmonary

dysplasia. Front Pediat. 8:5951572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Fanos V, Pintus MC, Lussu M, Atzori L,

Noto A, Stronati M, Guimaraes H, Marcialis MA, Rocha G, Moretti C,

et al: Urinary metabolomics of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD):

Preliminary data at birth suggest it is a congenital disease. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 27 (Suppl 2):S39–S45. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Pintus MC, Lussu M, Dessì A, Pintus R,

Noto A, Masile V, Marcialis MA, Puddu M, Fanos V and Atzori L:

Urinary 1H-NMR metabolomics in the first week of life

can anticipate BPD diagnosis. Oxid Med Cell Longev.

2018:76206712018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Piersigilli F and Bhandari V: Metabolomics

of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin Chim Acta. 500:109–114. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Zhao Q, Li Y, Chai X, Xu L, Zhang L, Ning

P, Huang J and Tian S: Interaction of inhalable volatile organic

compounds and pulmonary surfactant: Potential hazards of VOCs

exposure to lung. J Hazard Mater. 369:512–520. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Berkhout DJC, Niemarkt HJ, Benninga MA,

Budding AE, van Kaam AH, Kramer BW, Pantophlet CM, van Weissenbruch

MM, de Boer NKH and de Meij TGJ: Development of severe

bronchopulmonary dysplasia is associated with alterations in fecal

volatile organic compounds. Pediatr Res. 83:412–419. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Wright H, Bannaga AS, Iriarte R, Mahmoud M

and Arasaradnam RP: Utility of volatile organic compounds as a

diagnostic tool in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 89:263–268. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA,

Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K and Kato T:

Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of

colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 504:446–450. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Torow N, Hand TW and Hornef MW: Programmed

and environmental determinants driving neonatal mucosal immune

development. Immunity. 56:485–499. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Jugder BE, Kamareddine L and Watnick PI:

Microbiota-derived acetate activates intestinal innate immunity via

the Tip60 histone acetyltransferase complex. Immunity.

54:1683–1697. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Woo V and Alenghat T: Epigenetic

regulation by gut microbiota. Gut Microbes. 14:20224072022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Weiss GA and Hennet T: Mechanisms and

consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci.

74:2959–2977. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

McDermott AJ and Huffnagle GB: The

microbiome and regulation of mucosal immunity. Immunology.

142:24–31. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Cai J, Lu H, Su Z, Mi L, Xu S and Xue Z:

Dynamic Changes of NCR-type 3 innate lymphoid cells and their role

in mice with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Inflammation. 45:497–508.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Li B, Yin GF, Wang YL, Tan YM, Huang CL

and Fan XM: Impact of fecal microbiota transplantation on

TGF-β1/Smads/ERK signaling pathway of endotoxic acute lung injury

in rats. 3 Biotech. 10:522020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Tirone C, Pezza L, Paladini A, Tana M,

Aurilia C, Lio A, D'Ippolito S, Tersigni C, Posteraro B,

Sanguinetti M, et al: Gut and lung microbiota in preterm infants:

Immunological modulation and implication in neonatal outcomes.

Front Immunol. 10:29102019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Yao HC, Zhu Y, Lu HY, Ju HM, Xu SQ, Qiao Y

and Wei SJ: Type 2 innate lymphoid cell-derived amphiregulin

regulates type II alveolar epithelial cell transdifferentiation in

a mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Int Immunopharmacol.

122:1106722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Gray J, Oehrle K, Worthen G, Alenghat T,

Whitsett J and Deshmukh H: Intestinal commensal bacteria mediate

lung mucosal immunity and promote resistance of newborn mice to

infection. Sci Transl Med. 9:eaaf94122017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Zhu Y, Mi L, Lu H, Ju H, Hao X and Xu S:

ILC2 regulates hyperoxia-induced lung injury via an enhanced Th17

cell response in the BPD mouse model. BMC Pulm Med. 23:1882023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Willis KA and Ambalavanan N: Necrotizing

enterocolitis and the Gut-lung axis. Semin Perinatol.

45:1514542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Ngo VL, Lieber CM, Kang HJ, Sakamoto K,

Kuczma M, Plemper RK and Gewirtz AT: Intestinal microbiota

programming of alveolar macrophages influences severity of