Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) is associated with a high

incidence of morbidity and mortality. Despite the beneficial

effects of prompt reperfusion therapy on survival rates in the

initial stages of MI, post-MI cardiac remodeling remains a

significant contributing factor to heart failure and later

mortality (1). Cardiac remodeling

is a complex process involving functional and structural

disturbances in the myocardium, primarily driven by myocardial

injury and overload (2). This

process is typically characterized by three distinct stages:

Inflammation, proliferation and maturation (3). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)

represents a novel technological advancement that facilitates

transcriptome analysis at the single-cell level, thereby offering

comprehensive insights into the heterogeneity of diverse cell

populations within tissues. This technology enables the

identification of novel marker genes, cellular clusters and

cellular heterogeneity, as well as the inference of cellular

lineage trajectories. Furthermore, it can elucidate intercellular

interactions and facilitates comparisons between healthy and

diseased cells (4,5). In the context of MI, scRNA-seq can

elucidate transcriptional variability among similar cell types in

post-infarction tissues in comparison to normal tissues.

Furthermore, it can detect gene expression differences and dynamic

changes over time.

The present study reviewed the application of

scRNA-seq for the analysis of temporal changes in cardiomyocytes

and non-cardiomyocytes following MI. It aimed to provide a

theoretical basis for identifying new therapeutic targets for

preventing and treating post-infarction cardiac remodeling by

classifying different cell clusters and elucidating their roles in

post-infarction tissue remodeling.

Single-cell sequencing

Emergence of single-cell

sequencing

Traditional gene expression analysis techniques,

such as quantitative PCR, microarrays and high-throughput RNA

sequencing, permit the analysis of cell populations that are

heterogeneous at the gene expression level. These methods provide

only an averaged representation of gene expression across the

group, often overlooking low-abundance transcripts and masking the

unique characteristics of individual cells. As a result,

intercellular heterogeneity remains largely undetected (6–8). To

address these limitations, single-cell sequencing technology was

developed, enabling a shift from population-level analyses to the

study of individual cells. This technological advancement allows

for the in-depth exploration of tissues, organs and even entire

systems at the cellular level, markedly enhancing the current

understanding of cellular diversity and function (9–11).

Single-cell sequencing technology

Single-cell sequencing technology can be broadly

summarized as the amplification and sequencing of DNA or RNA at the

level of a single cell. The process primarily involves single-cell

isolation, nucleic acid processing, DNA amplification, library

construction, sequencing and data analysis (12–15).

Currently, single-cell sequencing techniques are categorized into

several types, including single-cell genome sequencing, single-cell

transcriptome sequencing (scRNA-seq), single-cell epigenome

sequencing, single-cell multiomics sequencing and spatial

transcriptome sequencing. Common single-cell sequencing methods

include Smart-seq (16),

Smart-seq2 (17), Drop-seq

(18), STRT-seq (19,20),

MARS-seq (21), MARS-seq2

(22) and Fluidigm C1 (23), which can be selected based on

specific experimental goals. Single-cell sequencing has been

applied across various fields, such as stem cell and developmental

biology, oncology and immunology and has become increasingly

important in both clinical and basic medical research. The present

review focused on the application of single-cell sequencing for

analyzing individual cells within post-infarction myocardial

tissues. Specifically, it highlighted the exploration of the

heterogeneity and enrichment of cardiomyocytes and

non-cardiomyocytes in these tissues, demonstrating the clustering

of these cells at different time points (for example, days 3, 7, 8

and 21 post-infarction) compared with control groups.

Advantages and disadvantages of

different single-cell sequencing methods to study

cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes in the heart can reach ≤100 µm in

length and 25 µm in width. This presents challenges for current

commercial single-cell transcriptome sequencing (scRNA-seq)

platforms, which have limitations regarding cell size. For

instance, the 10X Genomics platform has a microtubule diameter of

50 µm in its chip and it is recommended that the captured cells not

exceed 40 µm. As a result, cells must be filtered using a 30–40 µm

sieve to remove larger cells prior to capture. However, this

filtration step excludes large cardiomyocytes and prevents the

generation of scRNA-seq data from adult primary heart tissues

(24), To address this issue, the

majority of studies on cardiomyocytes have adopted single-nucleus

RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq), as it targets the nuclei of cells

rather than the entire cell. While snRNA-seq offers the advantage

of detecting nuclear-localized transcripts and maintaining membrane

integrity, it has limitations. Specifically, the method reduces

assay sensitivity and omits cytoplasmic mRNA information.

Additionally, isolated nuclei tend to adhere more than isolated

whole cells, increasing the risk of aggregation and duplex rate

expansion (25,26). However, snRNA-seq allows for the

transcriptomic analysis of tens of thousands of nuclei isolated

from fresh or frozen tissues, including mature mammalian hearts. It

facilitates the isolation of intact single cells from complex

tissues, reduces bias from easily recoverable cell types and

mitigates aberrant gene expression during cytokinesis (27,28).

Single-cell sequencing to analyze changes in

cardiomyocytes following MI

Cluster analysis and changes in

cardiomyocytes following MI

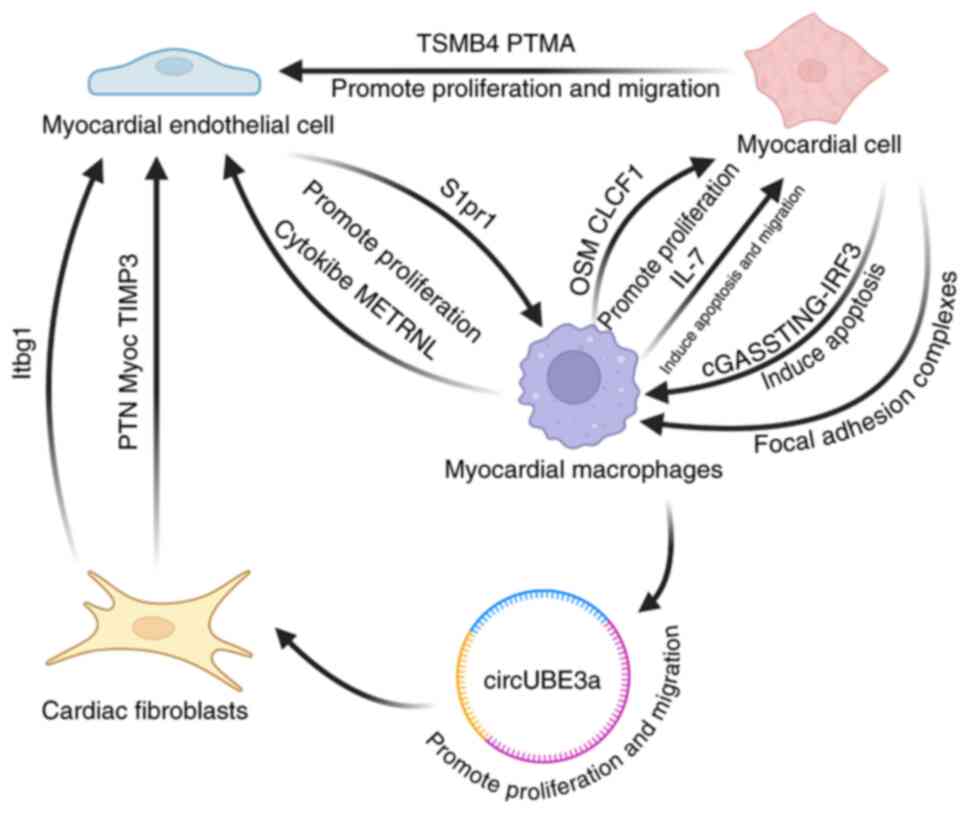

There are two key studies that focus on the cluster

analysis of cardiomyocytes following MI, as outlined in Table I. In 2020, Litviňuková et al

(29) identified five ventricular

cardiomyocyte populations (vCM1-vCM5) and five atrial cardiomyocyte

populations (aCM1-aCM5) by isolating single cells, nuclei and

CD45+ cells from the right and left ventricular free

walls, right and left atria, left ventricular apices and

interventricular septum using both scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq.

Detailed information about the marker genes for each cluster is

provided in Fig. 1A. vCM1 and vCM2

showed minimal differences, with vCM2 highly expressing PRELID2 and

the myosin genes MYH6 and CDH13. vCM3 expressed stress-responsive

genes, including ANKRD1 (30),

FHL1 (31), DUSP27 (32), XIRP1 and XIRP2. vCM4 was enriched

in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes such as NDUFB11, NDUFA4,

COX7C and COX5B. vCM5 highly expressed DLC1 and EBF2. Regarding the

atrial myocytes, aCM1 expressed basal atrial myocyte genes and

lower levels of neurological function molecules such as ADGRL2,

NFXL1 and ROBO2, while aCM2 was enriched in the right atrium and

predominantly expressed HAMP, SLIT3, ALDH1A2 (33), BRINP3 and GRXCR2. aCM3-5 and vCM3-5

shared similar transcriptional profiles. The present study

systematically mapped the molecular typing of atrial and

ventricular myocytes for the first time in adults, laying the

foundation for understanding cellular diversity in the

physiological state of the heart.

| Figure 1.Cardiomyocyte cluster typing and

marker genes for each cluster. vCM1-vCM5 represent myocardial cell

populations under different ventricular conditions, which are

determined by characteristics such as stress response, metabolic

changes and proliferation. Marker genes such as MYH6 are notably

expressed in vCM2, indicating that they are closely related to

metabolic activities in myocardial repair. (A) Adult cardiomyocyte

cluster typing and marker genes for each cluster. (B) Mouse

cardiomyocyte cluster typing and marker genes for each cluster.

SnRNA-seq, single-nucleus RNA sequencing; ScRNA-seq, single-cell

RNA sequencing; vCM, ventricular cardiomyocyte clusters; aCM,

atrial cardiomyocyte clusters; vCM1, functionally maintained

cardiomyocytes; vCM2, myocardial cells enriched in the right

ventricle (with high expression of MYH6); vCM3, stress-responsive

cardiomyocytes (expressing ANKRD1, etc.); vCM4, high-energy

metabolic cardiomyocytes (enriched mitochondrial genes, CRYAB);

vCM5, electrophysiologically associated cardiomyocytes (high

expression of DLC1 and EBF2); aCM1, basic functional

cardiomyocytes; aCM2, metabolic regulation of cardiomyocytes in the

right atrium (predominantly expressed ALDH1A2, etc.); aCM3, smooth

muscle-like cardiomyocytes; aCM4, cardiomyocytes with high

metabolic activity; aCM5, electrophysiological regulation of

cardiomyocytes; CM1, steady-state contractile mature

cardiomyocytes; CM2, injury stress-response cardiomyocytes (high

expression of Top2A and Casc5); CM3, metabolism-adaptive

cardiomyocytes; CM4, inflammatory/fibrotic regulatory

cardiomyocytes (expressing Atp5b, Sod2 and Mb); CM5, terminally

differentiated/senescent cardiomyocytes (expressing Xirp2, Ankrd1

and CD44). |

| Table I.A typical study on the analysis of

myocardial cell subsets by ScRNA-seq. |

Table I.

A typical study on the analysis of

myocardial cell subsets by ScRNA-seq.

| Source of

organization | Right and left

ventricular free walls, right and left atria, left ventricular apex

and interventricular septum in adults | Ventricular tissue

in mice |

|---|

| Methods | 1. Fresh tissue for

ScRNA-seq | SnRNA-seq |

|

| 2. Frozen tissue

for SnRNA-seq |

|

| Number of cells

captured | 45,870 cells;

78,023 CD45+ enriched cells and 363,213 nucleus | 21,737 myocardial

cell nucleus |

| Clusters | vCM1-vCM5;

aCM1-aCM5 | CM1-CM5 |

Cui et al (34) performed snRNA-seq on both

regenerating and non-regenerating cardiomyocytes in neonatal mice

on postnatal days 1 and 8, as well as on days 1 and 3 following MI

[1 and 3 days post-infarction (dpi)], comparing these with

sham-operated mice. The authors identified five main cardiomyocyte

populations, named CM1-CM5, based on the expression of Myh6. The

marker genes for each cluster are detailed in Fig. 1B. CM2 was characterized by high

expression of cell cycle genes such as Top2A and Casc5. CM4 highly

expressed metabolic genes involved in oxygen reduction (such as

Atp5b, Sod2 and Mb) and mechanistically, overexpression of NFYA and

NFE2L1 promoted cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival through

the activation of CM4-associated injury response pathways. CM5

exhibited high expression of actin filament-regulated genes (such

as Xirp2, Ankrd1 and CD44) with a gene expression profile

suggestive of decreased cardiac function (downregulation of

contractile/calcium channel genes), activation of stress/apoptotic

pathways and association with pathological remodeling (upregulation

of dilated cardiomyopathy and muscle hypertrophy-related genes).

Additionally, CM4 was found to be associated with cardiac

regeneration, as it upregulated cell cycle genes, particularly

during the G2/M phase. The proportion of CM4

cardiomyocytes increased following cardiac injury, with a marked

increase in regenerating hearts at 3 dpi, suggesting that CM4 may

be a key source of cardiomyocyte proliferation after injury. By

contrast, the CM5 population was markedly increased in

non-regenerating hearts at 1 and 3 dpi, which was potentially

linked to hypertrophic remodeling and cardiomyocyte apoptosis after

infarction (34). Together, the

aforementioned two studies revealed significant molecular

heterogeneity in cardiomyocytes and identified key functional

subpopulations. In particular, the study of Cui et al

(34) highlighted the value of CM4

as a potential target for regenerative therapies, as well as the

importance of CM5 as a marker of pathological remodeling.

Single-cell sequencing to investigate

the regenerative properties of cardiomyocytes

Kretzschmar et al (35) found that circulating cardiomyocytes

were observed only during the early postnatal growth phase by using

single-cell mRNA sequencing and genetic lineage tracing in two Ki67

knock-in mouse models. While a large number of proliferating

cardiomyocytes were detected in neonatal hearts, they were absent

in damaged adult hearts. Similarly, Cui et al (34) analyzed the number of proliferating

cardiomyocytes in regenerating hearts at 1, 3 and 7 dpi, revealing

that cardiomyocyte proliferation commenced as early as 3 dpi.

In other studies, fluorescence-activated cell

sorting was used to isolate cardiomyocyte nuclei with an antibody

targeting the myocardial nuclear membrane protein PCM1, which then

facilitated snRNA-seq analysis of cardiomyocyte nuclei (24,36,37).

Analysis of nuclear RNAs revealed that 23% of unique molecular

identifiers were mapped to introns and 52% to exons, confirming

cardiomyocyte regeneration following MI in neonatal mice (34). Additionally, Tani et al

(38) identified the mechanisms

underlying cardiac reprogramming for in vivo repair through

microarray and scRNA-seq. That study demonstrated that cardiac

reprogramming could repair chronic MI by promoting myocardial

regeneration and reducing fibrosis.

Heterogeneity of non-cardiomyocytes and

changes following MI

Endothelial cell (EC) heterogeneity

and changes following MI

The heterogeneity of ECs following MI has been

extensively studied using single-cell sequencing, with three key

articles providing valuable insights, as summarized in Table II. In 2020, Wang et al

(39) performed scRNA-seq on

ventricular tissues from timed-pregnant ICR/CD-1 regenerating and

non-regenerating mice, as well as age-matched sham controls, at 1

and 3 days following MI. Their analysis revealed that neonatal 1-

and 8-days mouse hearts exhibited heterogeneous EC clusters. A

total of six EC clusters were identified through cluster analysis,

namely Art.EC, VEC1-3, Endo.EC and Pro.EC. The marker genes for

each subcluster are shown in Fig.

2A. However, changes in the number of post-infarction

subclusters were not discussed in detail. All six clusters

exhibited high expression of the EC marker genes Cdh5 and Pecam1.

The Cxcl12 gene and others were enriched in the Art.EC population

(40), while H19 and Cpe were

enriched in the Endo.EC population (41,42).

Enrichment of cell cycle genes (Hmgb2, Birc5) in Pro.EC may provide

a cellular source for vascular regeneration.

![Endothelial cell cluster typing and

marker genes for each cluster. The high expression of capillary

marker Gpihbp1 in VEC1 and VEC2, as well as the enrichment of

macrovascular genes such as Plvap and Vwf in VEC3, indicate that

they are related to the maintenance of vascular activity and

angiogenesis. Endothelial cells have multiple functions in blood

vessels, including vascular stability, blood flow regulation,

material exchange and immune response. Following myocardial

infarction, endothelial cells have the functions of repair,

vascular regeneration and remodeling, as well as coagulation. (A)

Endothelial cell clusters of ventricular tissue origin and marker

genes. (B) Endothelial cell clusters of TIP origin and marker

genes. TIP, cardiac interstitial cell population; ScRNA-seq,

single-cell RNA sequencing; VEC1-3, venous endothelial cells (VEC1

highly expresses Gpihbp1, VEC2 cluster highly expresses Cxcl1 and

Icam1, VEC3 highly expresses Plvap and Vwf); Art.EC, arterial

endothelial cells (enriched with artery-related genes such as

Cxcl12); Endo, metabolism-related endothelial cells (specifically

expressing metabolic genes such as H19 and Cpe); Pro.EC,

proliferative active endothelial cells [highly expressing

proliferation genes Hmgb2 and Birc5]; VEC1, microvascular

endothelial cells [expressing Ly6a (encoding SCA1) and vascular

transcription factor Sox17]; VEC2, arterial endothelial cells

(involved in NOTCH signaling pathways, such as Sox17, Hey1); VEC3,

venous endothelial cells.](/article_images/mmr/32/6/mmr-32-06-13680-g01.jpg) | Figure 2.Endothelial cell cluster typing and

marker genes for each cluster. The high expression of capillary

marker Gpihbp1 in VEC1 and VEC2, as well as the enrichment of

macrovascular genes such as Plvap and Vwf in VEC3, indicate that

they are related to the maintenance of vascular activity and

angiogenesis. Endothelial cells have multiple functions in blood

vessels, including vascular stability, blood flow regulation,

material exchange and immune response. Following myocardial

infarction, endothelial cells have the functions of repair,

vascular regeneration and remodeling, as well as coagulation. (A)

Endothelial cell clusters of ventricular tissue origin and marker

genes. (B) Endothelial cell clusters of TIP origin and marker

genes. TIP, cardiac interstitial cell population; ScRNA-seq,

single-cell RNA sequencing; VEC1-3, venous endothelial cells (VEC1

highly expresses Gpihbp1, VEC2 cluster highly expresses Cxcl1 and

Icam1, VEC3 highly expresses Plvap and Vwf); Art.EC, arterial

endothelial cells (enriched with artery-related genes such as

Cxcl12); Endo, metabolism-related endothelial cells (specifically

expressing metabolic genes such as H19 and Cpe); Pro.EC,

proliferative active endothelial cells [highly expressing

proliferation genes Hmgb2 and Birc5]; VEC1, microvascular

endothelial cells [expressing Ly6a (encoding SCA1) and vascular

transcription factor Sox17]; VEC2, arterial endothelial cells

(involved in NOTCH signaling pathways, such as Sox17, Hey1); VEC3,

venous endothelial cells. |

| Table II.A typical study on ScRNA-seq of

endotheliocyte subsets. |

Table II.

A typical study on ScRNA-seq of

endotheliocyte subsets.

| Source of

organization | Ventricular tissue

of mice | Cardiac

interstitial cell populations in mice | Non-cardiac muscle

tissue from mice |

|---|

| Methods | 10X Genomics | 10X Genomics | ScRNA-seq |

|

| scRNA-seq | ScRNA-seq |

|

| Number of cells

captured | 17,320 cells | 13,331 cells | 35,312 cells |

| Clusters | Art.EC, VEC1-3,

Endo.EC, Pro.EC | EC1, EC2, EC3 | 5 endothelial cell

clusters |

In the VEC clusters, Gpihbp1 was highly expressed,

with VEC3 showing a higher expression level among the three

subclusters (VEC1-3) (40). The

VEC2 cluster overexpressed Cxcl1 and Icam1 and activated the

ROS/TNF signaling pathway to drive an inflammatory response.

In 2019, Farbehi et al (43) conducted sham and MI surgeries on

mice at 3 and 7 days post-infarction. The authors extracted the

cardiac interstitial cell population from 8-week-old male

PdgfraGFP/+ mice and performed single-cell expression

profiling. A total of three major EC clusters (EC1, EC2 and EC3)

were identified, The EC1 population expressed Ly6a (encoding SCA1)

and the vascular transcription factor Sox17, as indicated by marker

genes, which may represent microvascular ECs. EC2 expressed Sox17

and Hey1, which function downstream of the Notch signaling pathway

and are important for arterial ECs. In addition to the marker

genes, a number of EC3 cells expressed Prox1 and Lyve1. The EC1

cluster showed a rapid decrease at 3 dpi and a subsequent increase

at 7 dpi, although it remained below control levels.

In 2021, Tombor et al (44) conducted single-cell sequencing and

trajectory analysis on non-myocardial tissues from C57BL/6J

Cdh5-CreERT2 mice at various time points (days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 14

and 28 post-infarction). The authors identified five EC clusters,

with Cdh5 and Pecam1 serving as key marker genes. Subcluster 3

activated neutrophil chemotaxis and cytokine signaling to

exacerbate inflammatory damage. Subcluster 4 showed an increase in

number between days 1 and 7, returning to baseline levels after day

14. This subcluster expressed mesenchymal genes and proliferation

markers, while fatty acid metabolism genes were downregulated,

suggesting dysregulated energy metabolism.

Trajectory analysis confirmed that ECs underwent an

‘interstitial’ transient transition with partial recovery after 14

days. A separate study (45) found

that circFndc3b was markedly downregulated in heart following MI.

However, overexpression of circFndc3b in cardiac ECs increased

vascular endothelial growth factor expression, enhanced angiogenic

activity and reduced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes and ECs.

Additionally, the LPA-LPA2 signaling pathway was shown to promote

vascular neogenesis and maintain vascular homeostasis, which is

essential for restoring blood flow and repairing ischemic tissues

(46). EC clusters show a

sequential response of inflammation, proliferation and

mesenchymalization following MI and targeted intervention of

specific subpopulations (including inhibition of VEC2 inflammation,

amplification of Pro.EC and blockade of mesenchymal transformation)

is expected to break through the current bottleneck in vascular

regeneration therapy.

Fibroblast heterogeneity and

associated changes following MI

Cardiac fibroblasts are transformed into

myofibroblasts (MYOs) following injury, which plays a critical role

in mediating healing after acute MI (AMI) and contributes to

long-term fibrosis in chronic disease (47). Fibroblasts are essential for

cardiac remodeling following MI. Several studies have analyzed the

characterization and changes in various fibroblast clusters

following MI using single-cell sequencing, as detailed in Table III.

| Table III.A typical study on ScRNA-seq of

fibroblast subsets. |

Table III.

A typical study on ScRNA-seq of

fibroblast subsets.

| Source of

organization | Cardiac

interstitial cell populations in mice | Non-cardiomyocytes

from mice | Epicardial

interstitial cells in mice | Ventricular tissue

in mice | Ventricular tissue

in mice | Ventricular tissue

in mice | Mouse heart

tissue |

|---|

| Methods | 10XGenomics | ScRNA-seq | 10X Genomics | 10X Genomics | 10X Genomics | ATAC- | 10X Genomics |

|

| ScRNA-seq |

| ScRNA-seq | ScRNA-seq | ScRNA-seq | Seq | ScRNA-seq |

| Number of cells

captured | 13,331 cells | 27,349 cells | 38,600 cells | 17,320 cells | 10,487 cells | 29,176 cells | - |

| Clusters | MYO, F-Act, F-Cyc,

F-CI, F-SH, F-SL, F-WntX, F-Trans | Fibro-1, Fibro-2,

Fibro-3, Fibro-4, Fibro-5, Fibro-Myo | I, II, III; (three

main Myofb clusters: Myofb, ProlifMyofb, MFCs) | FB1-FB4,

Pro.FB | CF1-7 | A-J | F-SL, F-SH,

F-Trans, F-WntX, F-Act, F-CI, F-Cyc, F-IFNS |

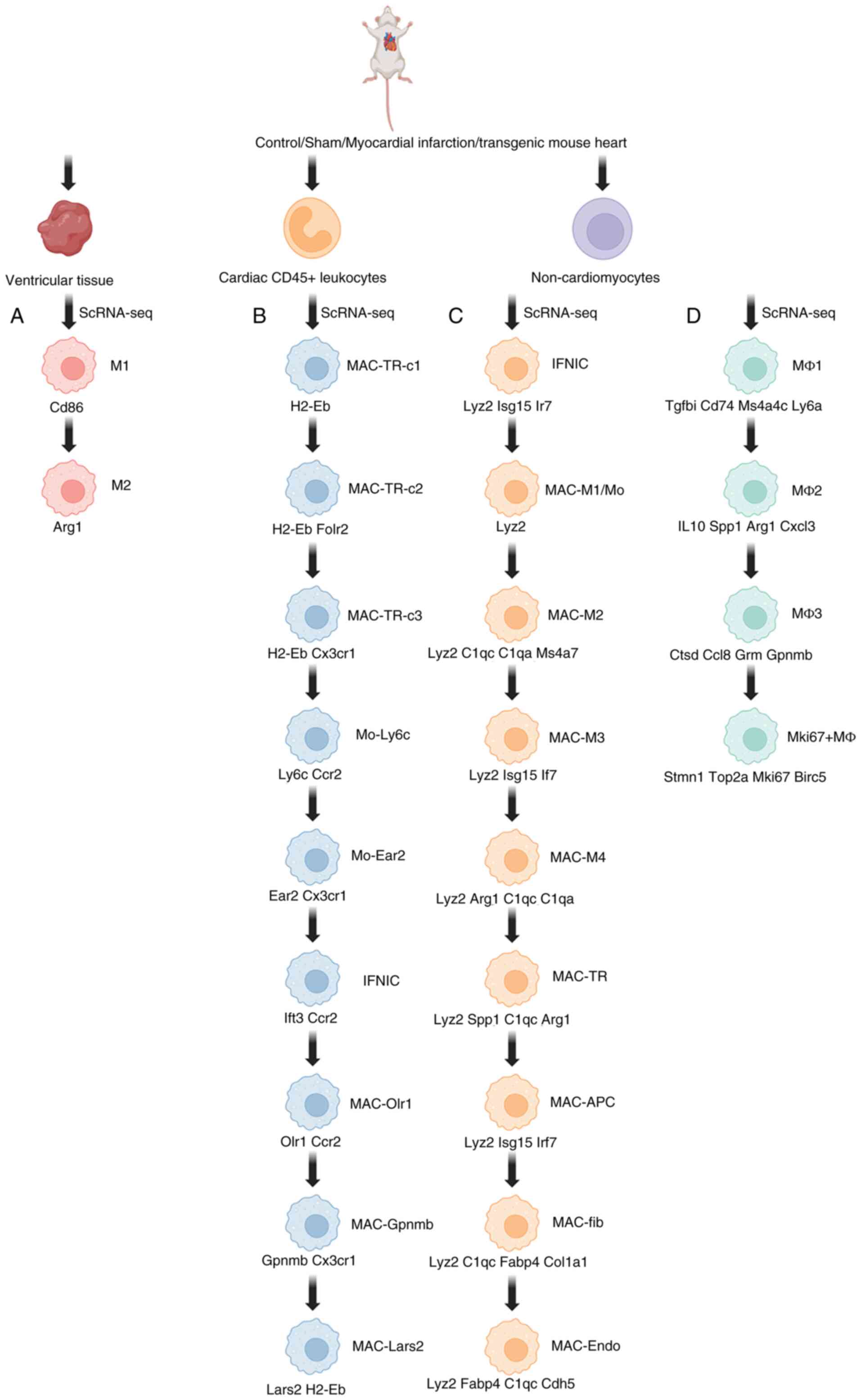

In 2019, Farbehi et al (43) classified the fibroblast population

into eight clusters: MYOs, activated fibroblasts (F-Act), a unique

GFP+ proliferating population (F-Cyc),

fibroblasts-circulating intermediates (F-CI), fibroblast Sca1 high

cluster (F-SH), fibroblast Sca1 low cluster (F-SL),

fibroblast-Wnt-expressing cluster (F-WntX) and

fibroblast-transitional cluster (F-Trans). The marker genes for

each cluster were not detailed.

MYOs expressed fibrillogenic proteins, such as

periostin (Postn) and contractile proteins such as smooth muscle

actin (48), along with collagen

genes, including Col1a1, Col3a1 and Col5a2 (49), which can drive collagen deposition

with scarring, with a significant increase in numbers on day 7

post-MI. F-Cyc specifically expressed the cell cycle genes Cdk1 and

Mki67 (Ki67), a source of reparative cells that could inhibit

overproliferation through targeted regulation, which peaked on day

3 and decreased on day 7 following MI, which is consistent with

previous studies showing that the peak of fibroblast proliferation

occurs on days 2–4 following MI (48,50).

F-CI showed upregulated expression of genes involved in fibroblast

activation, such as Postn, Cthrc1 and Acta2, although it did not

express cell cycle markers, which is suggestive of a potentially

activated fibroblast population that could enter the cell cycle.

This cluster also exhibited upregulated protein translation genes,

a feature not observed in F-Act. High expression of Ly6a (Sca1) and

Pdgfra was observed in F-SH, with multidirectional differentiation

capacity or involved in tissue repair, which was reduced on day 3

and partially restored on day 7 following MI. The newly identified

F-WntX and F-Trans were present in both pseudo and myocardial

infarcted hearts and F-WntX specifically showed overexpression of

the Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor Wif1, which affected the repair

process and it was markedly reduced at day 7 post-MI.

A single-cell sequencing study by Zhuang et

al (51) involving

non-cardiomyocytes from healthy and post-infarction male mice (aged

8–10 weeks) at days 0, 3 and 7 identified six fibroblast clusters

named Fibro-1, Fibro-2, Fibro-3, Fibro-4, Fibro-5 and Fibro-Myo.

Marker genes for Fibro-4 and Fibro-5 were not markedly expressed.

Marker genes for the remaining subgroups are shown in Fig. 3A. The proportion of fibroblasts

decreased at 3 dpi compared with the sham group, while Fibro-Myo

markedly increased at 7 dpi relative to other fibroblast clusters,

indicating its crucial role in ischemic response and healing

process. Cthrc1 and Ddah1 were both markedly upregulated in the

Fibro-Myo cluster. Cthrc1 is a known marker for myofibroblasts

(52), while Ddah1 can also serve

as a myofibroblast marker. Thus, Fibro_Myo plays an important role

in promoting cardiac healing and may act as a relevant

subpopulation of intervening cells after improved cardiac

remodeling.

| Figure 3.Fibroblast cluster typing and marker

genes for each cluster. The high expression of myofibroblast marker

genes Acta2, Tagln and Cthrc1 in FB1/B group/Fibro-Myo; enrichment

of the differentiation inhibitory gene Dlk1 in FB2; the specific

expression of the proliferation gene Mki67 in Pro.FB; the

upregulation of matrix homeostasis genes Fbln5 and Bgn in FB4; the

significant expression of sclerosis-related genes Comp, Cilp and

Angptl7 in CF5/CF6 and the enrichment of osteogenic genes Adamtsl2

and paracrine factor SFRP2 in MFCs. This indicates that they are

respectively involved in fibrotic driving, differentiation

inhibition, proliferation repair, matrix remodeling and chronic

scar hardening. (A*) Fibroblast clusters of cardiac interstitial

cell origin and marker genes. (B*) Fibroblast clusters of

non-cardiomyocyte origin and marker genes. (C*-E*) Fibroblast

clusters of cardiac ventricular tissue origin and marker genes. The

CF1-CF4 subsets highly express genes related to the degradation of

homeostasis fibroblasts (Hsd11b1, Lpl and Dpt) and ECM; CF5 and CF6

express genes related to the activation of fibroblasts, cartilage

development and ossification, including Angptl7, Cilp, Comp, Ecrg4,

Fmod, Postn, Meox1 and Thbs4. ScRNA-seq, single-cell RNA

sequencing; Fibro1, the matrix generates fibroblasts; ibro2,

damage-responsive fibroblasts; Fibro3, precursor fibroblasts;

Fibro-myo, myofibroblasts (highly expressing Cthrc1 and Ddah1);

Type I, quiescent interstitial progenitor cells; Type II, cells

responding to transitional state damage; Type III, terminally

differentiated profibrotic cells; FB1, stromal homeostasis

fibroblasts; FB2, inflammatory injury response fibroblasts

(specifically expressing Dlk1); FB3, precursor of myofibroblasts

(specifically expressing Nov, Thy1, Pi16, Axl and Cd34); FB4,

perivascular repair fibroblasts (highly expressing Fbln5, Bgn and

Mfap); Pro.FB, regenerative potential progenitor cells; CF1,

resting-state progenitor cells; CF2, immunomodulatory fibroblasts;

CF3, stromal homeostasis fibroblasts; CF4, transition state

precursor fibroblasts; CF5, contractile myofibroblasts; CF6,

perivascular repair fibroblasts; CF7, lipid metabolism-related

fibroblasts (responsive growth factor); B, the stromal

microenvironment maintains fibroblasts; D, antigen-presenting

fibroblasts; I, myofibroblast precursor cells; J, terminal

contractile myofibroblasts. |

In 2020, Forte et al (53) performed scRNA-seq on epicardial

mesenchymal cells from seven male Wt1Cre transgenic mice,

identifying three fibroblast populations (Type I, II and III). The

marker genes for each population are shown in Fig. 3B. The marker gene ZsGreen was

expressed in all Type I–III fibroblasts. The ratio of Type I

fibroblasts was markedly higher on days 1 and 3 post-infarction,

with the highest contribution ratio on day 3. Type III fibroblasts

were markedly higher on day 3 post-infarction.

Within the Type I fibroblast population, three

closely related subpopulations of ZsGreen+ epicardial-derived

fibroblasts (EpiDs) were identified: steady-state

epicardial-derived fibroblasts (HEpiDs), progenitor-like state

fibroblasts (PLS) and late-phase fibroblasts (LR). The HEpiD

population highly expressed genes involved in the response to

organic substances and metabolic effectors, such as Dpep1, Lpl,

Hsd11b1 and Cxcl14. The PLS population remained relatively stable

across all time points, with comparatively high expression of genes

related to cell migration and morphogenesis such as Cd248 and Pi16.

The LR population, which was predominantly present during the

post-infarction maturation phase (days 14–18), showed high

expression of genes involved in cellular differentiation,

osteogenesis and matrix remodeling, such as Adamtls2.

Type II fibroblasts specifically expressed genes

closely related to valve leaflet development and were involved in

endochondral ossification, Wnt signaling and structural

morphogenesis. However, Type III fibroblasts have not been fully

characterized to date.

Additionally, three main myofibroblast (Myofb)

populations were observed after subclustering: Myofb (Acta2,

Cthrc1), proliferative myofibroblasts (ProlifMyofb; Acta2, Cthrc1

and cell cycle genes) and a group of stromal fibroblasts (MFCs)

similar to those found in mature scars (48). Myofb expressed Acta2 and Cthrc1 and

their proportion increased markedly on days 3, 5 and 7

post-infarction (peaking at day 5). ProlifMyofb expressed Acta2,

Cthrc1, the pro-repair paracrine factors SFRP2 and CLU and cell

cycle genes. The proportions increased markedly on days 3 and 5

post-infarction, with a decreasing trend on day 7. Stromal

fibroblast-like cells MFCs increased markedly in proportion on days

14–28 post-infarction (mature scar phase). The aforementioned key

populations (such as early activated FI/EpiDs, proliferating

ProlifMyofb, MFCs contributing to bone/chondrocyte-like ECM) and

their specific marker genes (Pi16, Adamtsl2, Comp and Cilp) and

pathways (Wnt signaling) provide new potential targets for

anti-fibrotic and amelioration of scar remodeling therapies.

In 2020, Wang et al (39) identified five cardiac fibroblast

(FB) subclusters, labeled FB1-FB4 and proliferating fibroblasts

(Pro.FB), all of which highly expressed FB marker genes such as

Postn, Col1a1 and Pdgfra. Specific genes defining each cluster were

identified using differential expression analyses (the marker gene

expression for each subcluster is shown in Fig. 3C). Partial FB1 cells expressed high

levels of myofibroblast marker genes, including Acta2 and Tagln,

but low levels of the static FB marker Pdgfra, reflecting the early

steps in the activation and differentiation of cardiac FBs into

myofibroblasts (48,53). FB2 expressed Dlk1, an inhibitor of

myofibroblast differentiation (54). The specific genes expressed by FB3

may be related to normal fibroblast physiological functions

(55–58). High expression of extracellular

matrix organization-related genes such as Fbln5, Bgn and Mfap in

FB4 may be associated with the regulation of matrix structure and

homeostasis and could be considered as a regulatory target for

improving scar elasticity. By comparing the number dynamics of FB

subclusters between 1- and 8-day-old neonatal mice following MI, it

was found that the percentage of Pro.FB was markedly higher in

8-day-old neonatal mice at 3 days post-infarction, indicating that

FB proliferation precedes cardiac fibrosis. This observation aligns

with previous findings FB proliferation occurred following MI in

8-day-old neonatal mice (55). FB1

showed the highest increase in P8-injured hearts, demonstrating it

as a core fibrotic effector group. By temporally regulating

specific subgroups (inhibiting early amplification of Pro.FB and

blocking the fibrotic transformation of FB1), the fibrotic process

after infarction can be precisely intervened.

In 2023, Tani et al (38) classified fibroblasts into seven

clusters by performing scRNA-seq on left ventricular tissues from

control mice (Tcf21iCre/Tomato) and TTg (Tcf21iCre/Tomato/MGTH2A)

mice 3 months following MI. These clusters were labeled CF1 to CF7,

with their respective marker genes shown in Fig. 3D. CF5 and CF6 numbers increased in

Ctrl-MI and decreased in TTg-MI mice compared with controls.

Clusters CF1-CF4 expressed genes associated with steady-state

fibroblasts (Hsd11b1, Lpl and Dpt) and ECM degradation, while CF5

and CF6 expressed genes related to activated fibroblasts,

chondrogenesis and ossification, including Angptl7, Cilp, Comp,

Ecrg4, Fmod, Postn, Meox1 and Thbs4. CF7 expressed genes responsive

to growth factors. Future studies may reveal a direct association

between CF5/CF6 and its genetic signature

(Comp+/Cilp+/Postn+) and elevated

cardiac stiffness in advanced stages. Angptl7, Thbs4 or downstream

signaling pathways could be used as targets for the development of

novel antifibrotic drugs. CF5/CF6 signature profiles or expression

levels could be used as non-invasive indicators (serum COMP assay)

to assess the severity of chronic fibrosis and response to therapy.

Non-invasive indicators include serum COMP and CILP test. Patients

with high CF5/CF6 ratios may require targeted antisclerotic

therapy.

Ruiz-Villalba et al (52) performed single-cell sequencing on

cardiac tissues from healthy and post-infarction Col1α1-GFP mice at

7 and 14 days post-infarction, identifying 10 fibroblast clusters

(A-J). Clusters B, D, I and J showed distinct expression profiles,

as shown in Fig. 3E. Clusters F

and H-K remained unchanged across different time points. Cluster I

decreased to a minimum and then increased at 14 dpi, while the

percentage of cluster B markedly increased following MI, peaking at

day 14 and then declining. Cluster B was markedly enriched in the

infarct zone at 7 days post-MI, decreasing by day 30 (52). Cluster B had pathways and gene

ontologies related to ECM organization, cell proliferation and

cell-matrix adhesion (56,57). The top marker of subcluster B,

Cthrc1, has been associated with vascular remodeling and fibrosis

(58–61). The highly specific expression of

ECM-related genes in subcluster B suggests a strong association

with fibrotic scar formation, which exhibits intense necrotic

features after infarction and localizes to damaged tissue.

Precision targeted intervention of Cthrc1 or its downstream pathway

inhibits cluster B activation and blocks early fibrotic outbreak.

The development of relevant assays targeting serum profiles of

genes characteristic of group B (Cthrc1) to assess fibrosis

activity and therapeutic efficacy following MI should be

considered.

In 2022, Janbandhu et al (62) performed scRNA-seq on tdTomato+

CD31−CD45− fibroblasts from male magnetic

mice 8–12 weeks after a sham operation or MI. The fibroblasts were

classified into eight clusters: F-SL, F-SH, F-Trans, F-WntX, F-Act,

F-CI, F-Cyc and F-IFNS (IF Stimulated). The F-Act cluster was

markedly expanded following MI; the F-CI cluster was markedly

increased in cKO (Hif-1a Δflox/-;PdgfraMCM/+) hearts

following MI; and the number of F-SLs was markedly increased in cKO

and HET (Hif1a flox/+; PdgfraMCM/+) hearts

following MI. The F-Act cluster specifically exhibited

downregulated expression of genes encoding negative regulators of

cell signaling, particularly genes involved in key pathways

regulating CF proliferation such as MAPK-ERK1/2 and fibroblast

growth factor (FGF). This suggests that hypoxia-inducible factor 1

(HIF-1)α deletion may deregulate the inhibition of the

proliferative pathway and promote the conversion of F-Act to the

proliferative state (F-CI). The proliferation-associated subgroups

F-CI (proliferative intermediate state) and F-Cyc (proliferative

state) also showed downregulation of HIF-1 target genes, directly

confirming the central role of HIF-1α signaling in the regulation

of CF proliferative program. The HIF-1α pathway and its downstream

regulation of key subgroups (F-Act, F-CI) and signaling nodes

(MAPK-ERK, FGF pathway negative regulatory factors) are potential

targets for intervention. Modulating HIF-1α activity or interfering

with its downstream effector molecules may precisely control

pathological CF proliferation and activation and attenuate

deleterious fibrosis. The identified specific subgroups (markedly

expanded F-Act, accumulated F-CI and F-SL in cKO) and their

characteristic gene expression profiles are expected to serve as

novel molecular markers to assess the development of fibrosis.

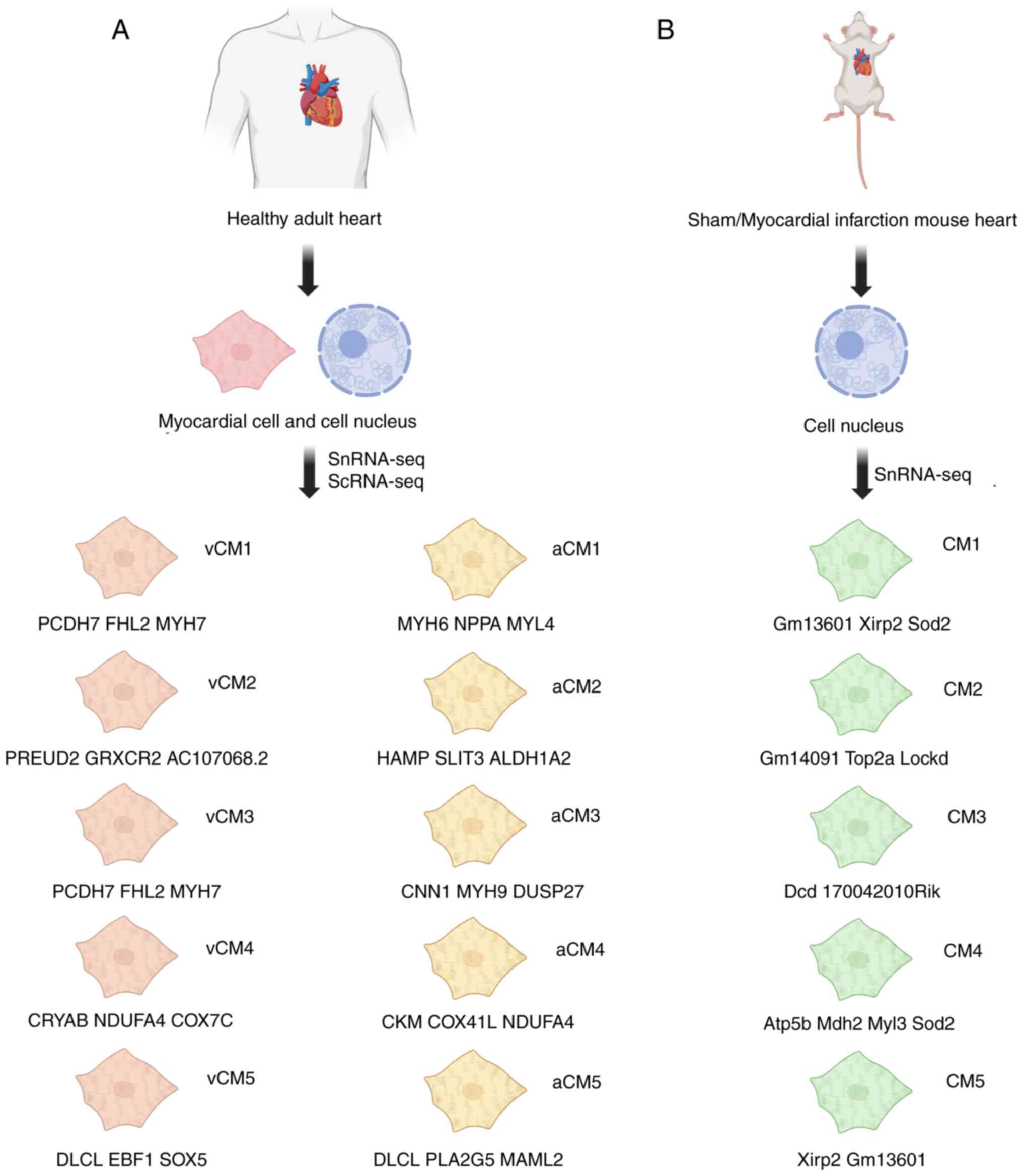

Monocyte/macrophage heterogeneity and

associated changes following MI

Macrophages are key players in inflammatory response

and post-infarction cardiac remodeling. The literature detailing

their detection via single-cell sequencing is summarized in

Table IV. In 2019, Farbehi et

al (43) classified monocytes

and macrophages into several clusters through single-cell RNA-seq,

as follows: M1MO, M1MΦ, M2MΦ, MAC-IFNIC, MAC-TR, MAC8, MAC7 and

MAC6. The M1MΦ cluster was identified as a derivative of classical

monocytes and was characterized by Ccr2high+Adgre1

(F4/80)+ Ly6c2+ H2-Aa (MHC-II)+,

driving the early inflammatory response. Non-classical M2MΦ cells,

which were characterized by Ccr2high Adgre1 (F4/80)+

H2-Aa (MHC-II) high-Ly6c2, participate in repair through the

non-arginase pathway (Arg1low), providing a novel immunomodulatory

mechanism After MI, the M1MΦ and M1MO populations increased at 3

dpi, while the M2MΦ population expanded at 7 dpi. On the third day

following MI, targeted inhibition of M1MΦ (such as anti-CCR2

antibody) was carried out to alleviate inflammatory damage; on the

7th day following MI, the M2MΦ/Cx3cr1+ population (such

as Cx3cr1 agonists) was enhanced to promote tissue repair.

| Table IV.A typical study on ScRNA-seq of

monocyte subsets. |

Table IV.

A typical study on ScRNA-seq of

monocyte subsets.

| Source of

organization | Cardiac

interstitial cell populations in mice | Ventricular tissue

in mice | Myocardial

CD45+ leukocytes in mice | Non-cardiomyocytes

from mice | CD45+

non-cardiomyocytes from mice |

|---|

| Methods | 10X | 10X | 10X | ScRNA-seq | ScRNA-seq |

|

| Genomics | Genomics | Genomics |

|

|

|

| ScRNA-seq | ScRNA-seq | ScRNA-seq |

|

|

| Number of cells

captured | 13,331 cells | 17,320 cells | 30,135 cells | 27,349 cells | 26,275 cells |

| Clusters | M1MO, M1MΦ, M2MΦ,

MAC-IFNIC, MAC-TR, MAC8, MAC7, MAC6 | M1, M2 | MAC-TRc1-3,

Mo-Ly6c, Mo-Ear2, MAC-Olr1, MAC-Gpnmb, MAC-Lars2, IFNIC | IFNIC, MAC-Mo/M1,

MAC-M2, MAC-TR, MAC-3, MAC-APC, MAC-4, MAC-Fib, MAC-Endo | MΦ1, MΦ2, MΦ3 |

In 2020, Wang et al (39) used Adgre1 as a specific marker for

mononuclear macrophages and classified macrophages into M1 and M2

clusters through higher-resolution sub-clustering analyses (the

marker genes for these clusters are shown in Fig. 4A). An increase in macrophage and

monocyte percentages was observed at all analyzed time points

post-MI. However, the timing and magnitude of macrophage elevation

differed depending on the neonatal stage, suggesting that

macrophages may play a role in post-infarction cardiac remodeling

and myocardial regeneration. Hearts from P1 mice exhibited higher

percentages of macrophages and monocytes 1 dpi, while hearts from

P8 showed elevated macrophage and monocyte percentages at 3 dpi. At

1 dpi, P1 mice demonstrated a rapid increase in the M1 and M2

macrophage populations compared with controls, with a unique level

of M2 infiltration not observed at other time points. Additionally,

both P1 and P8 neonatal mice showed a pronounced increase in M1 and

M2 macrophage composition at 3 dpi compared with controls (39). M2 macrophages secrete

anti-inflammatory cytokines, promoting wound healing and tissue

repair, which may support cardiac regeneration in neonatal mice and

it provides a theoretical basis for promoting cardiac repair via

enhancing the polarization or function of the M2 phenotype.

Furthermore, the macrophage-secreted factor CLCF1 was found to

enhance cardiomyocyte proliferation (39), which may provide options for

regenerative therapy.

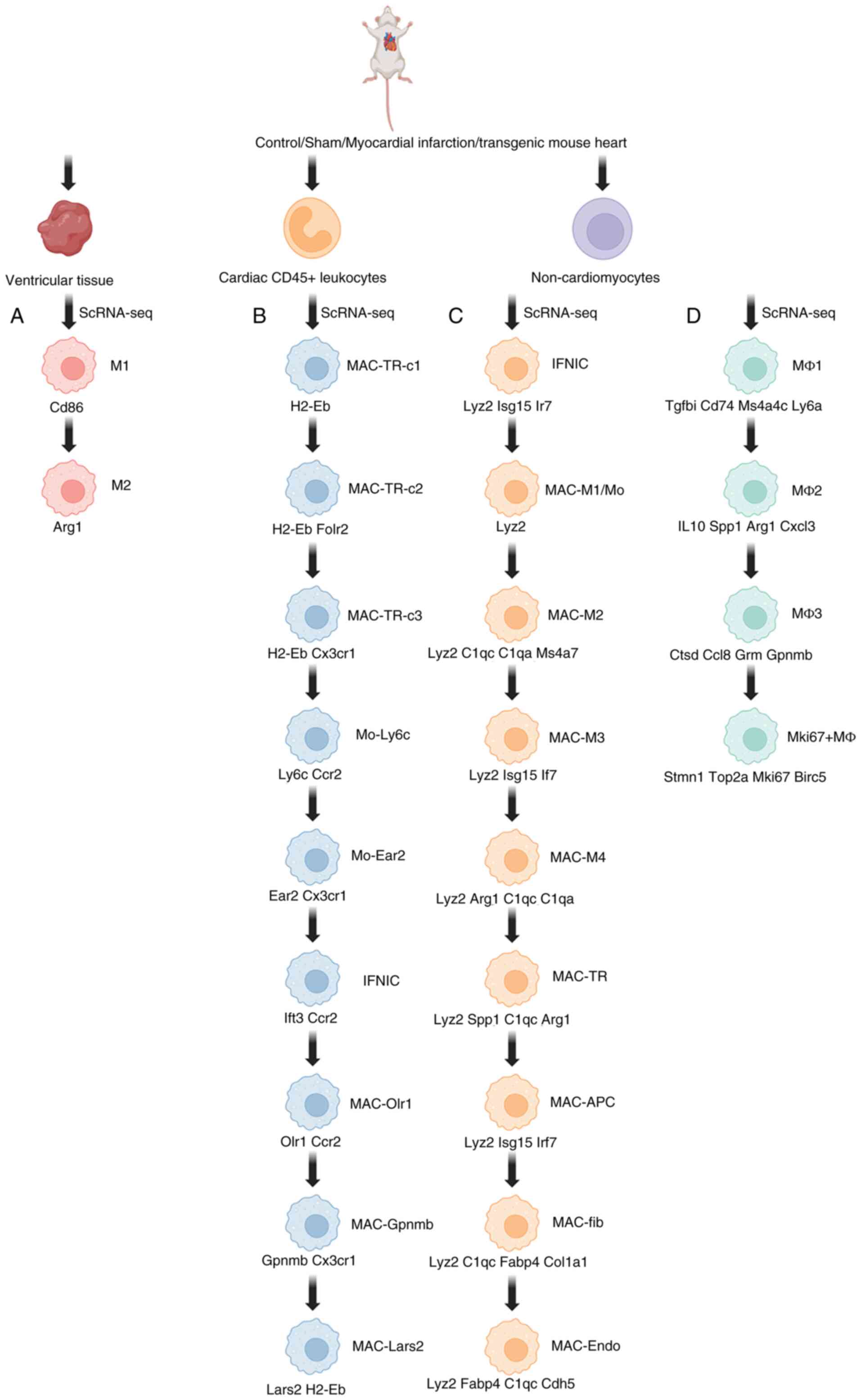

| Figure 4.Monocyte macrophage clusters typing

and marker genes for each cluster. High expression of

pro-inflammatory genes Ly6c2, S100a8 and the C1q family

(*C1qa/b/c*) in M1/MAC-Mo; enrichment of repair genes Spp1, Cd163

and Mrc1 in M2/MAC-TR; the significant upregulation of

anti-fibrotic genes Fabp5 and Gpnmb in Bhlhe41+MΦ; the activation

of phagocyte-related gene Folr2 in MAC-Gpnmb; and the co-expression

of the cross-lineage genes Col1a1 (fibroblast) and Cdh5

(endothelial) in MAC-Fib/MAC-Endo indicates that they are

respectively involved in inflammation initiation, tissue repair,

fibrosis inhibition, fragment clearance and lineage plasticity. (A)

Monocyte cell clusters of Cardiac ventricular tissue origin and

marker genes. (B) Monocyte cell clusters of Cardiac

CD45+ leukocytes origin and marker genes. (C) Monocyte

cell clusters of non-cardiomyocyte origin and marker genes. (D)

Monocyte cell clusters of non-cardiomyocyte (temporary cardiac

resident macrophage subset) origin and marker genes. The Ccr2_hi

cluster contains subgroups such as MAC_Mo/M1 and IFNIC and enriches

pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as Stat1 and Irf7. The

Ccr2_lo cluster contains subgroups such as MAC-TR, MAC-Fib and

MAC-Endo and is characterized by highly expressing Lyve1 and

Cx3cr1. ScRNA-seq, single-cell RNA sequencing; M1,

pro-inflammatory/damage-responsive macrophages (highly expressing

C1qa, C1qb, C1qc, Pf4); M2, repair/regeneration-promoting

macrophages (highly expressing C1qa, C1qb, C1qc, Spp1); MAC-TR-c1,

resting-state tissue-resident macrophages; MAC-TR-c2,

damage-responsive macrophages; MAC-TR-c3, ECM remodeling

macrophages; Mo-Ly6c, inflammatory mononuclear derived monocytes;

Mo-Ear2, anti-inflammatory readiness monocytes; IFNIC,

interferon-responsive macrophages; MAC-Olr1, lipid phagocytic

macrophages; MAC-Gpnmb, profibrotic macrophages; MAC-Lars2,

metabolic repair macrophages; IFNIC, interferon-responsive

macrophages; MAC-Mo/M1, classic pro-inflammatory macrophages;

MAC-M2, repair macrophages; MAC-TR, tissue-resident macrophages;

MAC-3, lipid-clearing macrophages; MAC-APC, antigen-presenting

macrophages; MAC-4, profibrotic macrophages; MAC-Fib, profibrotic

macrophages; MAC-Endo, promotes angiogenesis macrophages; MΦ1,

homeostatic tissue-resident macrophages (expressing

Timd4+ and Lyve1); MΦ2, repair hub macrophages

(expressing Bhlhe41+, Vegfa+); MΦ3,

profibrotic macrophages (expressing Spp1+ and

Mmp9+); Mki67+MΦ, proliferative and migratory

macrophages (expressing Mki67+ and

Cxcr4+). |

In 2022, Zhuang et al (63) identified nine subclusters of

mononuclear macrophages through single-cell RNA-seq: 3 intratissue

macrophage clusters (MAC-TRc1-3), 2 monocyte clusters (Mo-Ly6c and

Mo-Ear2) and 4 ischemia-associated macrophage subclusters with

differentially expressed marker genes (MAC-Olr1, MAC-Gpnmb,

MAC-Lars2 and IFNIC), with specific marker genes detailed in

Fig. 4B. MAC-Olr1 numbers

increased at 1 dpi and were characterized by the upregulation of

SASP and glycolysis pathways. The MAC-Gpnmb subcluster markedly

increased at 7 dpi and showed a powerful devouring ability (it was

positively correlated with phagocytosis and cellular FAO levels).

The Mo-Ly6c cluster was related to pro-inflammatory responses and

angiogenesis. The Mo-Ear2 cluster may be involved in adaptive

immune regulation following MI, providing a theoretical basis for

precisely regulating the differentiation of monocytes into

beneficial phenotypes (such as inhibiting pro-inflammatory Mo-Ly6c

and enhancing regulatory Mo-Ear2), which is helpful for balancing

inflammation and repair. Among the three MAC-TRs clusters,

MAC-TR-c2 expresses Folr2 and hematopoietic cell lineages,

lysosomes and endocytic signals are enriched in Folr2+

macrophages, making it an ideal target for promoting cardiac

repair. The proportion of Folr2+ macrophages decreased

on the first day following MI and recovered 7 days following

MI.

Zhuang et al (51) identified seven macrophage clusters:

IFNIC, MAC-Mo/M1, MAC-M2, MAC-TR, MAC-3, MAC-APC and MAC-4. The

marker genes for the newly identified clusters are detailed in

Fig. 4C. The proportions of

MAC-Mo/M1 and MAC-M2 increased at 3 dpi, with a particularly rapid

rise in MAC-M2, while MAC-TR showed greater proliferation by 7 dpi

(51). Pseudotemporal analysis of

macrophage populations revealed the presence of fibroblast-like

macrophages (MAC-Fib) and endothelial-like macrophages (MAC-Endo),

which expressed fibroblast markers (Col1a1) and endothelial markers

(Cdh5), respectively. Tissue-resident macrophages (MAC-TR) showed

increased expression of Cx3cr1 and H2-Aa, while downregulating the

pro-inflammatory gene Ly6c2. Some of these cells also expressed

Cd163 and Mrc1 while lacking H2-Aa, suggesting an anti-inflammatory

role in ischemic injury.

Further exploration of the core transcriptional

regulation driving macrophage differentiation was conducted using

single-cell regulatory network inference and clustering analysis

(64). A total of two clusters

were identified: The Ccr2_hi cluster contains subgroups, including

MAC_Mo/M1 and IFNIC; is enriched in pro-inflammatory transcription

factors such as Stat1 and Irf7; and it was positively associated

with myeloid cell activation, immune response and extracellular

secretion pathways (51). Previous

research has found that excessive activation of Irf3 is associated

with excessive interferon production and adverse inflammatory

responses (65). The Ccr2_lo

cluster contains subgroups such as MAC-TR, MAC-Fib and MAC-Endo and

is characterized by highly expressing Lyve1 and Cx3cr1 (66). This cluster is markedly enriched in

the gene set involved in the regulation of cell proliferation and

the response to growth factor HGF/TGF-β and is regulated by

transcription factors such as Egr1 and Jund (51). Functional comparative analysis

clearly supported the Ccr2_lo cluster (especially MAC-TR) to exert

protective effects of self-renewal and anti-inflammation following

MI (51). Enhancing the

anti-inflammatory function of MAC-TR and the angiogenesis ability

of MAC-Endo by using small molecule agonists is a direction for

treating cardiac remodeling following MI. In addition, in

vitro expansion of Ccr2_lo characteristic cells and

transplantation into the infarcted area is also a means to achieve

anti-inflammatory and vascular regeneration simultaneously.

In 2023, Xu et al (67) identified two major tissue

macrophage populations at steady state (Sham) using scRNA-seq in

8–10 week-old male C57BL/6J mice:

LYVE1+MHCII−CCR2− and

LYVE1−MHCII+CCR2−. The two

populations were markedly reduced at 3 days post-MI. Four

additional macrophage clusters showed a significant increase in

response to MI: MΦ1, MΦ2, MΦ3 (referred to as

Bhlhe41+MΦ) and Mki67+MΦ. MΦ3, which

exhibited higher Bhlhe41 activation. The specific marker genes for

each cluster are detailed in Fig.

4D. The number of MΦ3 cells markedly increased on day 3

post-MI, peaked on 7 dpi and returned to baseline by 14 dpi,

clearly indicating the key intervention time window targeting this

repair macrophage. In addition, Fabp5, Gpnmb and Ccl8 were markedly

upregulated in MΦ3 at 3 dpi, whereas Il1b, Il10, Tgfb1 and Nfkb1

were downregulated. Cell death-related markers, including those for

autophagy, apoptosis and necroptosis, were also downregulated,

along with O-GlcNAc modification, ubiquitylation levels and hypoxic

injury markers in Bhlhe41+ MΦ cells. These macrophages

played roles in collagen catabolic processes, positive regulation

of tissue remodeling and lipid metabolism pathways. Notably,

Bhlhe41+ MΦs were the only macrophage cluster enriched

in cardiac fibroblast lineage cells (Pdgfr-GFP+). It is

suggested that this subgroup plays a core protective role in

restricting the dilation of the infarcted area and preventing

pathological fibrosis by inhibiting the activation of

myofibroblasts and excessive collagen deposition. The

Bhlhe41+ m4 subgroup demonstrates a strong repair

ability. In the future, therapeutic strategies can be focused on

promoting its expansion and recruitment, maintaining its phenotype

and function and simulating its secretory factors/functions,

etc.

T-cell and B-cell heterogeneity and

associated changes following MI

T-cells and B-cells are critical participants in the

post-infarction inflammatory response. The literature on their

role, as identified by single-cell sequencing, is summarized in

Table V. In 2019, Farbehi et

al (43) identified two T-cell

clusters through single-cell RNA-seq: TC1-Cd8 (Cd8a+),

representing cytotoxic T-cells and TC2-Cd4 (Cd+4

Lef1+), which likely represents helper T-cells.

| Table V.A typical study on ScRNA-seq of T/B

cell subsets. |

Table V.

A typical study on ScRNA-seq of T/B

cell subsets.

| Source of

organization | Cardiac

interstitial cell populations in mice | Non-cardiomyocytes

from mice | Cardiac and

mediastinal lymph node B cells in mice | Myocardial

CD45+ leukocytes in mice |

|---|

| Methods | 10X Genomics | ScRNA-seq | 10X Genomics | 10X Genomics |

|

| ScRNA-seq |

| ScRNA-seq, S2

Cartridge | ScRNA-seq |

|

|

|

| ScRNA-seq |

|

| Number of cells

captured | 13,331 cells | 27,349 cells | 6,588 cells | 30,135 cells |

| Clusters | TC1-Cd8

(Cd8a+), TC2Cd4 (Cd4+ Lef1+) | Naïve T-cell,

effector T-cell, regulatory T-cell, NK-cell | B1, B2, MZ, GC, hB,

CD74+ cluster, IFNR, Cyc | CD4-C1-CCR7 and

CD8-C1-CCR7 represent naïve T cells and CD4-C2-CXCR3 and

CD8-C2-Gzmk represent effector T cells; B cell-Cd20, B

cell-Cd23 |

In 2020, Zhuang et al (51) performed single-cell sequencing on

non-cardiomyocytes from 8–10 week-old male mice, comparing

sham-operated mice and those at 3, 7 and 10 days post-infarction.

The authors classified T-cells into four clusters: Naïve, effector,

regulatory and NK cells. The marker genes for each cluster are

detailed in Fig. 5A. A significant

infiltration of T-cells was observed 7 days following MI. The

effector T-cell population showed upregulation of Ccl6 and Il1b and

was enriched for pathways associated with cell activation and

immune system regulation. The regulatory T-cell population

positively associated with inflammatory pathways of humoral immune

responses and myeloid leukocyte differentiation. Effector T-cells

were enriched for pro-inflammatory regulators such as Irf5 and

Fosb, while regulatory T-cells were enriched for activated Sp1

regulators. Exploring drugs targeting transcriptional regulatory

factors such as Irf5 or Fosb can regulate the activation and

function of effector T cells. Regulating the immunomodulatory

properties and Sp1-related stability exhibited by T cell subsets is

a potential therapeutic strategy for promoting immune tolerance and

improving the cardiac repair environment.

![T and B cell clusters typing and

marker genes for each cluster [MZ marker genes related literature].

High expression of pro-inflammatory factor IL-1β, chemokine Ccl6

and transcription factor Irf5/Fosb in effector T cells regulate the

enrichment of immune regulatory pathways (such as Sp1) in T cells;

co-activation of the dual-chemokine receptor Cxcr5/Ccr7 and the

tissue repair factor Tgfb1 in hB cells; and upregulation of the

cell cycle gene Trp53/Cdc27 in Cyc B cells indicates that they are

respectively involved in inflammatory drive, immunosuppression,

repair chemotaxis and proliferation responses. (A) T cell clusters

typing and marker genes for each cluster. (B) Cell clusters typing

and marker genes for each cluster. ScRNA-seq, single-cell RNA

sequencing; Naive T cells, immune response preparatory T cells;

effector T cells, pro-inflammatory injury type T cells (expressing

Ccl6 and IL-1β); regulatory T cells, immunosuppressive T cells

(rich in Sp1 regulators); NK cells, direct killer T cells; B1

cells, natural immune barrier type B cells; B2 cells, lymphoid

tissue localization type B cells; marginal zone B cells (MZ), rapid

antibody-responsive B cells; germinal center B cells (GC),

antibody-affinity mature B cells; hB, heart-associated B cells,

repair of core-type B cells (expressing Tgfb1, Cd69, Cxcr5 and

Ccr7); CD74+, antigen-presenting type B fine (expressing

Cd74+); IFNR cells, interferon-responsive B cells; Cyc

cells, proliferation type B cells (expressing Trp53, Cdc27, Mrto4,

Nhp2, Ranbp1 and Ncl Gnl3).](/article_images/mmr/32/6/mmr-32-06-13680-g04.jpg) | Figure 5.T and B cell clusters typing and

marker genes for each cluster [MZ marker genes related literature].

High expression of pro-inflammatory factor IL-1β, chemokine Ccl6

and transcription factor Irf5/Fosb in effector T cells regulate the

enrichment of immune regulatory pathways (such as Sp1) in T cells;

co-activation of the dual-chemokine receptor Cxcr5/Ccr7 and the

tissue repair factor Tgfb1 in hB cells; and upregulation of the

cell cycle gene Trp53/Cdc27 in Cyc B cells indicates that they are

respectively involved in inflammatory drive, immunosuppression,

repair chemotaxis and proliferation responses. (A) T cell clusters

typing and marker genes for each cluster. (B) Cell clusters typing

and marker genes for each cluster. ScRNA-seq, single-cell RNA

sequencing; Naive T cells, immune response preparatory T cells;

effector T cells, pro-inflammatory injury type T cells (expressing

Ccl6 and IL-1β); regulatory T cells, immunosuppressive T cells

(rich in Sp1 regulators); NK cells, direct killer T cells; B1

cells, natural immune barrier type B cells; B2 cells, lymphoid

tissue localization type B cells; marginal zone B cells (MZ), rapid

antibody-responsive B cells; germinal center B cells (GC),

antibody-affinity mature B cells; hB, heart-associated B cells,

repair of core-type B cells (expressing Tgfb1, Cd69, Cxcr5 and

Ccr7); CD74+, antigen-presenting type B fine (expressing

Cd74+); IFNR cells, interferon-responsive B cells; Cyc

cells, proliferation type B cells (expressing Trp53, Cdc27, Mrto4,

Nhp2, Ranbp1 and Ncl Gnl3). |

In 2022, Zhuang et al (63) conducted scRNA-seq of live

myocardial CD45+ leukocytes. Samples were collected at 7

days post-sham surgery and at 1 or 7 dpi. The authors identified

CD4-C1-CCR7 and CD8-C1-CCR7 as markers for naïve T-cells, while

CD4-C2-CXCR3 and CD8-C2-Gzmk were markers for effector T-cells.

These markers were positively associated with the differentiation

of Th17, Th1 and Th2 cells, as well as the PD-L1 signaling pathway.

CD4-C2-CXCR3 and CD8-C2-Gzmk T-cell populations both markedly

increased at 7 dpi. Cxcr3+ CD4 T-cells and Gzmk+ CD8

T-cells activated key adaptive immune responses via Fos and Fosb

activity on 7 dpi. Targeting specific effector T cell subsets or

their activation pathways (such as Fos/Fosb) may serve as a new

strategy for regulating cardiac inflammation and repair following

MI.

In 2022, Qian et al (68) observed that CD8+

effector T-cells secreted effector molecules such as GZMB, GNLY and

PRF1, which promoted apoptosis and EC shedding, leading to plaque

erosion. This was demonstrated via scRNA-seq of peripheral blood

mononuclear cells from 10 patients with AMI (5 with plaque rupture

and 5 without) (69). Upregulation

of CXCR4, B4GALT1 and TNFAIP3 was associated with angiogenesis and

wound healing, thereby promoting plaque healing (70). It may help evaluate the plaque

stability or healing potential of patients with AMI and provide a

basis for individualized intervention.

In 2021, Heinrichs et al (71) performed single-cell RNA and B-cell

receptor sequencing on 20 B-cells purified from the heart and

mediastinal lymph nodes on day 5 post-MI, revealing extensive

phenotypic diversity among B-cells infiltrating the infarcted

heart. scRNA-seq of 6,588 B-cells using UMAP revealed nine B-cell

subpopulations in the heart, including B1, B2 (including follicular

B-cells), marginal zone B-cells (MZ), germinal center B-cells (GC)

and heart-associated B-cells (hB). Additionally, three smaller

clusters were identified: a CD74+ cluster, an

IFN-responsive transcript-rich subpopulation and a cluster enriched

in cell cycle-related and ribosome biogenesis transcripts (Trp53,

Cdc27, Mrto4, Nhp2, Ranbp1, Ncl and Gnl3). This last cluster likely

represents cycling B-cell subpopulations (Fig. 5B).

With the exception of the hB population, all other

clusters underwent significant numerical expansion post-MI. B cells

are the only subpopulation expressing Cxcr5. The hB cell population

upregulates the expression of transforming growth factor β1 (Tgfb1)

and the activation marker Cd69, suggesting that it is in an

activated state and may be involved in the process of immune

regulation or tissue repair. It is also the only subpopulation that

simultaneously highly expressed both Cxcr5 and Ccr7 (double

positive). Flow cytometry confirmed that

CCR7+CXCR5+ B cells were specifically

enriched in the infarcted scar tissue. Their numbers peaked at 7

dpi (71). The pro-repair

properties of hB cells (such as secreting Tgfb1) and their specific

localization in scar tissue make them potential therapeutic targets

for promoting myocardial repair or inhibiting adverse remodeling.

Regulating its chemotaxis (such as the CXCR5/CCR7 pathway) or

functions (such as the Tgfb1 signaling) may have therapeutic value.

The expansion of different B cell subsets (such as pro-inflammatory

Cyc B that may regulate/repair hB) reflects the complex immune

response following MI, providing ideas for developing the

regulation of immune balance and optimizing the repair process.

In 2022, Zhuang et al (63) identified two B-cell clusters with

differential expression of Cd20 (Ms4a1) and Cd23 (Fcer1g):

B-cell-Cd20 and B-cell-Cd23. B-cell-Cd20 showed a slight expansion

at 1 dpi, while B-cell-Cd23 expanded at 7 dpi. B cell-CD20 highly

expressed CD20 (regulating B cell maturation, differentiation and

BCR signal transduction) and CD69 (an early activation marker). B

cell-Cd23 specifically and highly expresses CD23 (a low-affinity

IgE receptor involved in the activation regulation of B cells). The

CD20+ or CD23+ B cell subsets can be used as

markers for evaluating the immune response following MI.

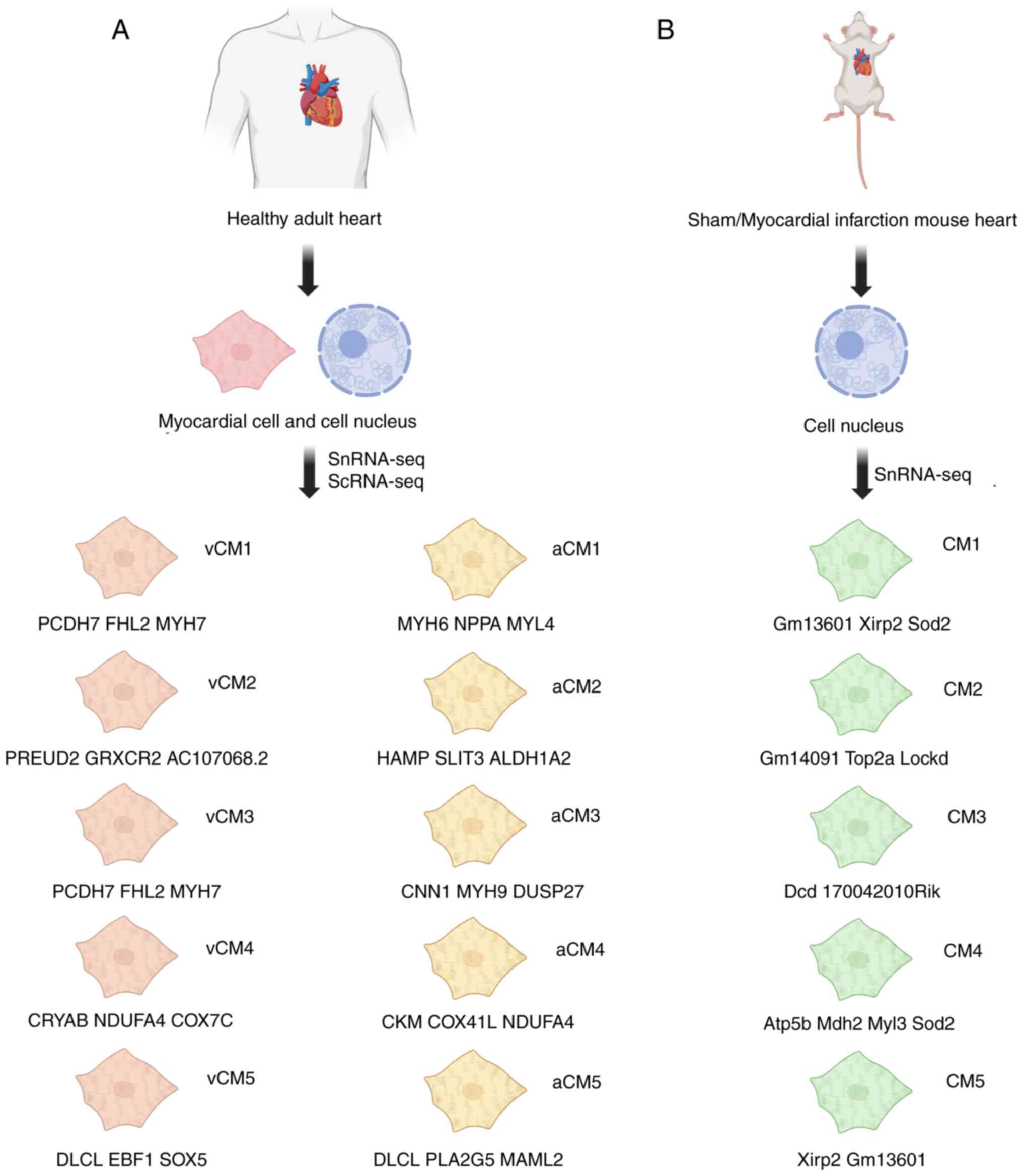

Interactions between cells in the heart

following MI

Increased intercellular communication is a hallmark

of cardiac repair and plays a critical role in cardiac remodeling

(72). The analysis of cellular

interactions through single-cell sequencing has deepened the

understanding of post-infarction cellular interactions, as

demonstrated in the following studies.

Cardiomyocytes and macrophages

In 2020, Li et al (73) found that macrophage secretion of

oncostatin M (OSM) promoted cardiomyocyte (CM) proliferation and

cardiac regeneration after infarction. Wang et al (39) observed that mononuclear macrophages

secreted CLCF1, which promoted neonatal CM proliferation. Yan et

al (74) in 2021 showed that

post-infarction macrophages could induce CM apoptosis and enhance

CM migration in vitro via IL-7. Wong et al (75) concluded that post-infarction

CCR2+ macrophages interact with CMs via adhesion plaque

complex markers such as β-integrins. Hu et al (76) demonstrated that, after infarction,

CMs that had undergone death could interact with macrophages

through the cGAS-STING-IRF3 pathway, potentially inducing apoptosis

in healthy CMs.

Cardiomyocytes and ECs

In 2021, Gladka et al (77) found that ZEB2 induced

cardiomyocytes to produce TMSB4 and PTMA, which drove EC migration

and proliferation, thereby promoting angiogenesis and improving

cardiac function.

Macrophages and ECs

In 2021, Kuang et al (78) demonstrated that ECs interacted with

macrophages in a contact-dependent manner via the

S1P/S1PR1/ERK/CSF1 signaling pathway, promoting the proliferation

of anti-inflammatory macrophages in damaged cardiac tissues and

reducing adverse cardiac remodeling post-MI. Alonso-Herranz et

al (79) found that post-MI

cardiac macrophages increased MMP14 (MT1-MMP) expression, activated

TGF-β1 and triggered paracrine SMAD2-mediated signaling in ECs.

Reboll et al (80) reported

that macrophages interact with ECs via the cytokine metrnl.

Fibroblasts and ECs

In 2019, Farbehi et al (43) revealed that myofibroblasts

interacted closely with ECs through an interaction network.

Fibroblast populations (F-SH, F-SL, F-Act and F-WntX) frequently

interacted with ECs and PDGFRA-GFP+ fibroblasts and

CD31+ ECs showed close spatial associations or direct

contact, with F-WntX upregulating ligands such as PTN, MyoC and

TIMP3. In 2020, Zhuang et al (51) utilized a selected collection of

human ligand-receptor pairs (81)

and the STRING database (82) to

demonstrate that Fibro-Myo and Endo_1 interacted via Itgb1.

Fibroblasts and macrophages

In 2021, Wang et al (83) identified that post-infarction

macrophages release endosomal membrane-derived vesicles enriched

with circUbe3a, which promotes fibroblast proliferation, migration

and phenotypic transformation, potentially exacerbating myocardial

fibrosis post-MI. Wang et al (39) identified RSPO1 as a mediator of

cellular crosstalk between epicardial cells and ECs, promoting the

angiogenic capacity of ECs during the regeneration of

post-infarction neonatal hearts.

In conclusion, interactions between cardiomyocytes

and non-cardiomyocytes, as well as between non-cardiomyocyte

populations, play an essential role in post-infarction cardiac

remodeling. These interactions are summarized in Fig. 6.

Summary and prospects

Through single-cell sequencing technology, mainly

scRNA-seq and snRNA-seq, different subsets of cardiomyocytes and

changes in the proportion of subsets and the expression of

different genes following MI have been explored. It has been

reported that cardiomyocytes following MI have renewability, which

is maintained within 1 week after birth. The aforementioned changes

of interstitial cardiomyocytes indicate their different functions.

Different interactions occur between cardiomyocytes and stromal

cells through regulatory factors, also demonstrating the response

of cardiomyocytes and cardiomyocyte stromal cells to MI.

Single-cell sequencing can help researchers precisely distinguish

the specific roles and changes of different cell subsets in these

processes, analyze the signaling pathways and interaction networks

of different cell subsets and identify the key molecules and

pathways that affect cardiac remodeling, thereby providing more

precise targets for treatment following MI.

However, the differences in the time points

selected across studies may affect the interpretation and

conclusion: Sparse time point designs (such as analyzing only 3 and

28 days) may miss key transitions. The peak of inflammation in

mouse models is within 72 h, while in humans it lasts several

weeks, resulting in limited functional studies on repair phase cell

subsets (such as VEC2 ECs). Technical method differences (such as

the sensitivity of 10X Genomics and Smart-seq2) can affect the

capture of rare subgroups (such as VEC3). To reduce bias, studies

need to adopt a dense time series design, combine spatial

transcriptome verification and correct the cross-species time axis

to comprehensively analyze the spatio-temporal specific functions

of cell subsets. In addition, single-cell sequencing can reveal

significant differences and provide a complementary value in cell

responses between animal models and clinical samples. Regarding

temporal dynamics differences. animal models (such as mouse models)

can help analyze h-level cell transformation after injury (such as

Bhlhe41+ macrophages expanding at 72 h to mediate

repair), while clinical samples (human autopsies/transplanted

hearts) only provide single-point snapshots and are difficult to

employ for capturing dynamic processes. In animal models, the

mononuclear-macrophage transformation is predominant, while in

clinical samples, B/T cells are more involved (for example,

CXCR5+hB cells secrete IL-10 to promote repair). In

animal models, there is regeneration in the heart, but in adult

human hearts, there is almost no regeneration. The fibroblast

subsets in the scar area are more complex (such as the enrichment

of the FAP+/DDR2+ pro-fibrotic subsets).

Future research should more deeply identify and

functionally verify the key rare cell subpopulations involved in

repair (such as angiogenesis, anti-inflammation and the transition

from pro-fibrotic to anti-fibrotic) and regeneration. The

combination of scRNA-seq with lineage tracing, CRISPR screening and

space technology may help precisely reveal the specific roles of

these cells in dynamic changes, fate determination and

intercellular communication after injury. Design individualized

targeted therapeutic strategies (such as specific antibodies, small

interfering RNA and small molecule inhibitors) should be employed

for analyzing key dysregulated pathways or harmful cell populations

in specific patients. The integration of scRNA-seq and spatial

transcriptomics is the core direction in the future, as it can not

only identify cell types, but also accurately reveal their spatial

distribution, neighborhood associations and local ecological niche

characteristics in the infarct, boundary and distal areas.

Combining space technology and stromal omics, studying how

different cells sense, reshape and respond to regional-specific

extracellular matrix changes, is at the core of fibrosis

regulation. Inferring cell interactions (such as CellChat and

NicheNet) using scRNA-seq data will depict the signal networks that

change dynamically following MI in greater depth. In the future, it

will be necessary to use secretomics to verify and quantify the

activities of key signaling pathways. Deeply integrating multimodal

data, utilizing artificial intelligence to mine hidden patterns in

complex data, establishing a comprehensive human heart cell atlas

(health and disease status), developing minimally invasive

biomarkers and intelligent targeted delivery systems and verifying

single-cell guided strategies in clinical trials should be the

focus of future studies. scRNA-seq is expected to markedly change

the current understanding and management of MI within the next

decade, moving from the traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ treatment

to a new era of precise diagnosis and targeted intervention based

on individual cellular and molecular characteristics.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by National Natural Science

Foundation Youth Fund (grant no. 81700230), China Postdoctoral

Science Foundation (grant no. 2022M711321) and Jining Medical

University Research Fund for Academician Lin He New Medicine (grant

no. JYHL2022FZD03).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XB, HG, CG, NL, LG and XC contributed to the study

conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was

written by XB. Writing was supervised and guided by XC and LG. Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors commented on previous

versions of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Heusch G: Myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion

injury and cardioprotection in perspective. Nat Rev Cardiol.

17:773–789. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

van der Bijl P, Abou R, Goedemans L, Gersh

BJ, Holmes DR Jr, Ajmone Marsan N, Delgado V and Bax JJ: Left

ventricular post-infarct remodeling: Implications for systolic

function improvement and outcomes in the modern era. JACC Heart

Fail. 8:131–140. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Liu Y, Xu J, Wu M, Kang L and Xu B: The

effector cells and cellular mediators of immune system involved in

cardiac inflammation and fibrosis after myocardial infarction. J

Cell Physiol. 235:8996–9004. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zheng GXY, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin

P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, Ziraldo SB, Wheeler TD, McDermott GP, Zhu J,

et al: Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of

single cells. Nat Commun. 8:140492017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM

III, Zheng S, Butler A, Lee MJ, Wilk AJ, Darby C, Zager M, et al:

Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell.

184:3573–3587.e29. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rondini EA and Granneman JG: Single cell

approaches to address adipose tissue stromal cell heterogeneity.

Biochem J. 477:583–600. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mackay IM, Arden KE and Nitsche A:

Real-time PCR in virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:1292–1305. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kalisky T, Blainey P and Quake SR: Genomic

analysis at the single-cell level. Annu Rev Genet. 45:431–445.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

van der Leun AM, Thommen DS and Schumacher

TN: CD8+ T cell states in human cancer: Insights from

single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:218–232. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Stewart BJ, Ferdinand JR and Clatworthy

MR: Using single-cell technologies to map the human immune

system-implications for nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 16:112–128.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Zaragosi LE, Deprez M and Barbry P: Using

single-cell RNA sequencing to unravel cell lineage relationships in

the respiratory tract. Biochem Soc Trans. 48:327–336. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ziegenhain C, Vieth B, Parekh S, Reinius

B, Guillaumet-Adkins A, Smets M, Leonhardt H, Heyn H, Hellmann I

and Enard W: Comparative analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing

methods. Mol Cell. 65:631–643.e4. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gao S: Data analysis in single-cell

transcriptome sequencing. Methods Mol Biol. 1754:311–326. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Saliba AE, Westermann AJ, Gorski SA and

Vogel J: Single-cell RNA-seq: Advances and future challenges.

Nucleic Acids Res. 42:8845–8860. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tang F, Barbacioru C, Wang Y, Nordman E,

Lee C, Xu N, Wang X, Bodeau J, Tuch BB, Siddiqui A, et al: mRNA-Seq

whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods.

6:377–382. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hou Y, Song L, Zhu P, Zhang B, Tao Y, Xu

X, Li F, Wu K, Liang J, Shao D, et al: Single-cell exome sequencing

and monoclonal evolution of a JAK2-negative myeloproliferative

neoplasm. Cell. 148:873–885. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Picelli S, Faridani OR, Björklund AK,

Winberg G, Sagasser S and Sandberg R: Full-length RNA-seq from

single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat Protoc. 9:171–181. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Macosko EZ, Basu A, Satija R, Nemesh J,

Shekhar K, Goldman M, Tirosh I, Bialas AR, Kamitaki N, Martersteck

EM, et al: Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of

individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell. 161:1202–1214.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Klein CA, Seidl S, Petat-Dutter K, Offner

S, Geigl JB, Schmidt-Kittler O, Wendler N, Passlick B, Huber RM,

Schlimok G, et al: Combined transcriptome and genome analysis of

single micrometastatic cells. Nat Biotechnol. 20:387–392. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sasagawa Y, Nikaido I, Hayashi T, Danno H,

Uno KD, Imai T and Ueda HR: Quartz-Seq: A highly reproducible and

sensitive single-cell RNA sequencing method, reveals non-genetic