Introduction

Insulin resistance represents a fundamental

pathophysiological mechanism in the development of type 2 diabetes

mellitus (T2DM), characterized by a reduced response of tissue to

insulin signaling. Research has demonstrated that intestinal immune

system dysregulation, which manifests as persistent inflammation,

serves a pivotal role in mediating T2DM-associated insulin

resistance (1). Experimental

evidence has indicated that aberrant activation of T helper (Th)17

cells triggers intestinal inflammation and precipitates autoimmune

disorders, whereas regulatory T cells (Tregs) exert

immunosuppressive functions to modulate inflammatory processes

(2). Furthermore, perturbation of

the homeostatic balance between Tregs and Th17 cells has emerged as

a critical determinant in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance,

as evidenced by elevated IL-17 levels and enhanced pro-inflammatory

cytokine secretion (3). Multiple

studies have established that Tregs and Th17 cells are essential

mediators in maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis, with their

dynamic equilibrium being crucial for proper immune function

(4–6).

Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax ex

Pax et Hoffm, formerly known as TaiZiShen, was initially described

in the Chinese book Ben Cao Cong Xin, and is often used to treat

diabetes, chronic obstructive pneumonia, cardiomyocyte injury,

immune deficiency and other diseases (7–9).

This herb has been included in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia primarily

due to its medicinal value (7).

Polysaccharides (molecular weight: 52-210 kDa), such

as PF40, are the primary active ingredient of Pseudostellaria

heterophylla (10). Structural

elucidation of PF40 by UV spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared

spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance has confirmed the

absence of protein and nucleic acid impurities, as well as the

presence of characteristic α-pyranose configurations (11). Notably, Congo red assay and

scanning probe microscopy analyses have revealed that PF40 adopts a

triple-helical conformation and a multi-branched molecular

structure, features known to enhance the biological stability and

functional activity of polysaccharides. Compared with other

plant-derived polysaccharides, PF40 displays superior thermal

stability and is predominantly amorphous in physical state, as

evidenced by X-ray diffraction analysis. These properties not only

support its suitability for pharmaceutical processing but also

enhance its in vivo functionality (11). A radioisotope tracing study

previously demonstrated that PF40 exhibits targeted accumulation in

the small intestine following oral administration, suggesting a

high degree of intestinal bioavailability and potential for

interaction with gut-associated lymphoid tissues (12). This gut-enrichment behavior may

explain its previously observed ability to modulate intestinal

immune homeostasis, restore Th17 cell/Treg balance, and improve

mucosal barrier integrity in diabetic models (9,11).

Together, these unique structural and biopharmaceutical features

distinguish PF40 from other polysaccharides and support its

candidacy as a novel immunomodulatory agent for the treatment of

metabolic diseases.

Previous studies have shown that PF40 has favorable

pharmacological activity in improving insulin resistance and

reducing fasting glucose in a rat model of T2DM (10–12).

In our previous study, it was revealed that PF40 can correct

imbalances in Treg/Th17 cells in the jejunal tissue (11). Th17 cells and Tregs, alongside Th1

and Th2 cells, constitute crucial subpopulations of CD4+

T lymphocytes that serve key roles in maintaining intestinal

microbial balance and overall metabolic homeostasis (13,14).

Studies have shown that in states of insulin resistance,

pro-inflammatory CD4+ T cells, such as Th1 and Th17

cells, are markedly activated in the gut, whereas anti-inflammatory

Tregs are relatively deficient, exacerbating intestinal

inflammatory responses (15,16).

Additionally, impairment of the intestinal barrier and alterations

in gut microbiota composition further amplify the expansion of

inflammatory CD4+ T cells, thereby promoting the

progression of systemic insulin resistance (17,18).

Interfering with the balance of intestinal CD4+ T cell

subpopulations may offer a novel approach for preventing and

treating insulin resistance. Previous research has suggested that

enhancing Treg activity or suppressing the uncontrolled

proliferation of Th1 and Th17 cells can notably improve insulin

sensitivity and alleviate symptoms of metabolic disorders (19,20).

However, understanding regarding how the CD4+ T-cell

subset balance influences insulin resistance, and the detailed

molecular mechanisms involved, remains limited.

Our previous study established the therapeutic

efficacy of PF40 in rat models of T2DM, where dose-response

analyses were conducted, and it was demonstrated that PF40 could

markedly improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic parameters

(10). Notably, when combined with

metformin, PF40 exerts a synergistic effect, resulting in superior

glycemic control and reduced systemic inflammation compared with

either treatment alone (10,11).

These findings underscore the potential of PF40 as an effective

immunometabolic modulator. Building on this evidence, the present

study focuses on identifying the cellular and molecular mechanisms

by which PF40 influences hepatocellular insulin signaling via

intestinal CD4+ T cells.

The present study aimed to evaluate the activity of

differentially treated CD4+ T cells in ameliorating

insulin resistance using an in vitro cell model. Particular

focus was given to their effects on antioxidant activity,

apoptosis, glucose uptake and energy metabolism in

insulin-resistant (IR) cells, alongside their influence on the

insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. By

elucidating the roles and underlying regulatory mechanisms of

differentially treated CD4+ T cells, the current study

may provide theoretical support for developing interventional

strategies against insulin resistance and advance immunotherapeutic

approaches for metabolic diseases.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

Pseudostellaria heterophylla was obtained

from a Good Agricultural Practice-certified cultivation base in

Zherong (Fujian Zheshen Biotechnology Co., Ltd), and PF40 was

prepared as described previously (10). The total sugar content was measured

using the anthrone-sulfuric acid method as described previously

(21), and the protein content of

PF40 was determined using a Bradford assay with BSA (Beyotime

Biotechnology) as the standard (22). The average molecular weight of PF40

was characterized by high-performance gel permeation chromatography

(23). The monosaccharide

composition was analyzed using pre-column derivatization with

1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone followed by high-performance liquid

chromatography (HPLC) (24). BNL

CL.2 cells were obtained from Procell Life Science & Technology

Co., Ltd. Other materials, including fetal bovine serum (FBS), DMEM

and trypsin (used for cell passaging), were obtained from Gibco

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). DMSO was sourced from

MilliporeSigma. The glucose assay kit (cat. no. S0201S) was

acquired from Shanghai Beyotime Biotechnology. The phosphorylated

(p)-PI3K (p85-Tyr607; cat. no. AF3241) polyclonal antibody was

purchased from Affinity biosciences Co., Ltd. PI3K (cat. no.

A4992), IRS-1 (cat. no. A16902), p-IRS-1 (Ser307; cat. no. AP0552),

AKT (cat. no. A17909) and p-AKT (S473; cat. no. AP1208) polyclonal

antibodies were obtained from ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.

Intervention and purification of

CD4+ T cells

The T2DM rat model was established as described

previously (11). Briefly, 60 male

Sprague Dawley rats (4 weeks, 180-200 g, SPF conditions) were

obtained from Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences Shanghai

Laboratory Animal Center (certificate no. SCXK 2017-0005) and

housed under standard conditions with free access to food and water

and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Except for the normal control

group, all other rats were intraperitoneally injected with freshly

prepared STZ solution (0.021 mol/l in pH 4.5 sodium citrate buffer,

0.5 ml/100 g bodyweight) after overnight fasting with free access

to water to induce diabetes. After 3 days, rats with fasting blood

glucose ≥16.7 mmol/l were considered to have T2DM. A total of 38

rats were successfully rendered diabetic. These T2DM rats were

randomly assigned to four groups: model (n=10), PF40 [1.5 g/kg body

weight (bw); n=10], metformin (Merck KGaA; 135 mg/kg bw; n=9) and

PF40 + metformin (PF40, 1.5 g/kg bw + metformin 135 mg/kg bw; n=9).

Animals received their assigned treatments via oral gavage once

daily for a duration of 4 weeks. The normal control group received

an equivalent volume of saline. Each intervention lasted 4 weeks in

total. Subsequently, the rats were euthanized in a small animal

anesthesia machine using 10% isoflurane for 30 min, with death

confirmed by the absence of a heartbeat. Jejunal lymphocytes were

isolated as described previously (25). Briefly, jejunal tissue was rapidly

excised and rinsed with cold PBS to remove feces. The tissue was

then minced and digested in a solution containing 50 mg/ml

deoxyribonuclease I and 30 mg/ml liberase for 30 min at 37°C to

facilitate lymphocyte release. The digested tissue was filtered

through a 70-µm cell mesh to obtain a single-cell suspension,

washed with PBS and resuspended in 40% Percoll solution. This

suspension was layered over 70% Percoll solution and centrifuged at

800 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Lymphocytes were collected from the

interface between the two layers. CD4+ T cells were then

purified from the lymphocyte population using the MagniSort™

CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.; cat. no. 8804-6820-74) according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Cell purity was assessed using a NovoCyte flow cytometer

(NovoCyte; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and analyzed with

NovoExpress software (version 1.4.1; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Samples in which CD4+ T cells accounted for at least 80%

of the population were used for further analysis. CD4+ T

cells were labeled based on the interventions the mice received as

follows: Control (Con-T), model (Mod-T), PF40 (P-T), metformin

(M-T), and combined PF40 and metformin (PM-T). Cells were cultured

in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at

37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Establishment of the insulin

resistance model

BNL CL.2 cells were seeded in culture flasks and

maintained in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1%

penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5%

CO2 and 95% humidity. The culture medium was changed

every 48 h. Once the cells reached 80-90% confluence, the culture

medium was replaced with DMEM containing varying concentrations of

insulin (1×10−6, 1×10−7, 1×10−8

and 1×10−9 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA; cat. no.

Y0001717) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h to identify the optimal

insulin concentration that could induce insulin resistance. Based

on glucose measurements in the culture medium, the concentration of

1×10−7 mol/l was identified as the ideal concentration

for inducing insulin resistance. Subsequently, cells were treated

with 1×10−7 mol/l insulin for 24, 36, 48 and 60 h to

determine the optimal duration for stable induction of insulin

resistance. Untreated cells were used as a control group and each

experimental condition included six replicates. After treatment,

the supernatant was collected, and the glucose concentration in the

culture medium was measured using a glucose assay kit using the

o-toluidine method (Beyotime Biotechnology). The glucose

consumption was calculated based on the difference between the

initial glucose concentration and the post-treatment concentration,

enabling assessment of the response of cells to insulin and

identification of the optimal concentration and treatment duration

for stable insulin resistance induction.

Co-culture of IR-BNL CL.2 cells with

CD4+ T cells

The co-culture model was established using the

Transwell insert system, with CD4+ T cells seeded in the

apical medium and IR-BNL CL.2 cells seeded in the basolateral

medium (26,27), using inserts with 6 wells and a

pore size of 0.4 µm. Purified CD4+ T cells were

co-cultured with IR-BNL CL.2 cells at various CD4+ T

cells to IR-BNL CL.2 cell ratios: 1:1, 2:1, 5:1, 10:1, 20:1 and

40:1, to determine the optimal ratio for the co-culture system.

Phenol red-free DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was used to

avoid color interference. Both CD4+ T cells and IR-BNL

CL.2 cells were cultured in this medium, supplemented with 10% FBS,

and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After 24 h,

10 µl CCK-8 solution (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) was added to each

well, followed by a 2-h incubation at 37°C. Subsequently,

absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The optimal ratio of

CD4+ T cells to IR-BNL CL.2 cells was determined based

on changes in IR-BNL CL.2 cell viability across different

co-culture ratios.

Glucose consumption assay

CD4+ T cells from different treatment

groups were co-cultured with IR-BNL CL.2 cells at the optimal cell

ratio in phenol red-free DMEM for 24 h. At the end of the

co-culture period, the supernatant was collected and glucose

concentration was measured according to the instructions provided

with the glucose assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology). Glucose

consumption was calculated as the difference between the initial

glucose concentration and the glucose concentration in the

supernatant after 24 h. The glucose degradation ratio was

calculated as the percentage decrease in glucose consumption in the

experimental group relative to the BNL CL.2 control group.

Specifically, it was determined by subtracting the glucose

consumption of the experimental group from that of the control

group, dividing this difference by the glucose consumption of the

control group, and multiplying by 100.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and

malondialdehyde (MDA) assays

Following co-culture with CD4+ T cells

under the respective treatment conditions [the control (Con-T),

model (Mod-T), PF40 (P-T), metformin (M-T) or PF40 + metformin

(PM-T) groups], IR-BNL CL.2 cells from each treatment group were

collected and washed three times with cold PBS. Cells were then

lysed with an appropriate volume of RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubating on ice for 15 min. The

lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the

supernatant was collected for subsequent analysis. Protein

concentrations were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (cat.

no. A045-4-2; Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. The activity of SOD and levels of

MDA were measured using respective commercial assay kits according

to the manufacturer's protocol (SOD Assay Kit, cat. no. A001-3-2;

MDA Assay Kit, cat. no. A003-1-2; both from Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

assay

Treated IR-BNL CL.2 cells, following co-culture with

CD4+ T cells under the respective experimental

conditions (Con-T, Mod-T, P-T, M-T or PM-T), were collected and

seeded into black, opaque-bottom 96-well plates for ROS detection.

Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Following adherence, the cells were washed twice with serum-free

medium, and each well was loaded with 100 µM DCFDA in 1X buffer

(cat. no. S0035S; Beyotime Biotechnology). After a 45-min

incubation at 37°C, the DCFDA solution was removed and the cells

were washed twice with 1X PBS to minimize non-specific staining.

The plate was then analyzed using a flow cytometer (NovoCyte), and

data were collected and analyzed using NovoExpress software

(version 1.4.1) according to the DCFDA kit protocol to quantify ROS

levels (28).

Apoptosis assay

To evaluate apoptosis, IR-BNL CL.2 cells were

collected and washed twice with cold PBS after co-culture with

CD4+ T cells under the indicated treatment conditions

(Con-T, Mod-T, P-T, M-T or PM-T). Cells were resuspended in 1X

binding buffer, and 5 µl Alexa Fluor™ 488 Annexin V and 1 µl 100

µg/ml propidium iodide were added as per the manufacturer's

instructions (cat. no. A10788; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 20 min to

protect against photobleaching. Following incubation, the samples

were analyzed immediately on a flow cytometer (NovoCyte), and data

were collected and analyzed using NovoExpress software (version

1.4.1) to determine the proportions of live and apoptotic cells

across treatment groups (29).

Western blot analysis

IR-BNL CL.2 cells were collected and washed three

times with cold PBS following co-culture with CD4+ T

cells under the indicated treatment conditions (Con-T, Mod-T, P-T,

M-T or PM-T). Cells were then lysed with RIPA lysis buffer

containing protease inhibitors and lysates were incubated on ice

for 30 min, vortexing every 10 min, to ensure complete lysis.

Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the

supernatant was collected for protein analysis. Protein

concentrations were quantified using a BCA assay kit, and equal

amounts of protein (30 µg/lane) from each sample were denatured at

95°C for 5 min before being separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% gels.

Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto PVDF

membranes at 4°C. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA at room

temperature for 1 h to minimize non-specific binding, and were then

incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit monoclonal primary

antibodies targeting p-PI3K (1:1,000), PI3K (1:1,000), p-AKT

(1:500), AKT (1:500), p-IRS-1 (1:1,000), IRS-1 (1:1,000) and

β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no. AC026; ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.). The

following day, the membranes were washed three times with TBS-T

buffer (TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20; 5 min each) to remove unbound

antibodies, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000; cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, protein bands

were visualized using a Pierce™ Fast Western kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and images were captured. Band intensities were

semi-quantified using Image Lab software (version 6.1.0; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.).

Targeted energy metabolomics analysis

by ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass pectrometry

(UPLC-MS/MS)

IR-BNL CL.2 cells were submitted to Wekemo Tech Co

(https://www.bioincloud.tech/) for

metabolomics analysis via UPLC-MS/MS. Briefly, 50 mg cell sample

was mixed with 1,000 µl water/methanol/acetonitrile (1:2:2, v/v),

vortexed for 25 min, and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at

4°C. The supernatant was dried using a vacuum centrifuge, and the

residue was reconstituted in 100 µl 50% acetonitrile. The sample

was centrifuged again at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C before

undergoing UPLC-MS/MS analysis at Wekemo Tech Co. The conditions

for mass spectrometry and chromatography are described in detail in

the Supplementary materials.

Statistical analysis and

visualization

Experimental data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation. Baseline data across treatment groups were

analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test for comparisons between

two groups or a one-way ANOVA for comparisons between multiple

groups. Following one-way ANOVA, Tukey's post hoc multiple

comparisons test was performed to determine significant differences

between individual groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Targeted energy metabolomics

data analysis and visualization were performed on the Wekemo

Bioincloud platform (https://bioincloud.tech/) using default parameters. To

further explore metabolic differences between groups, principal

component analysis (PCA), orthogonal partial least squares

discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) and redundancy analysis (RDA) were

conducted on the same platform. Unless otherwise specified, all

analyses were carried out with the standard settings provided by

Wekemo Bioincloud.

Results

Physicochemical characterization of

PF40

To investigate the physicochemical properties of

PF40, a series of compositional and structural analyses were

conducted. The polysaccharide yield from Pseudostellaria

heterophylla was 18.63±1.21%. The total carbohydrate content of

PF40 was determined to be 79.85±3.54%, while the protein content

was relatively low at 0.12±0.01%, indicating a high degree of

polysaccharide purity. Gel permeation chromatography revealed that

PF40 exhibited a molecular weight distribution ranging from 52.6 to

212 kDa (Fig. S1), suggesting a

heterogeneous macromolecular population. Monosaccharide composition

was analyzed by HPLC after acid hydrolysis. The results showed that

glucose was the predominant monosaccharide in PF40 (84.06 mol%),

followed by a minor proportion of galactose (2.50 mol%). These

findings were further supported by co-chromatography with standard

monosaccharides and peak area comparison, as shown in the

chromatograms. Fig. S2A presents

the chromatograms of glucose and galactose standards, while

Fig. S2B shows the monosaccharide

composition analysis of PF40. These results indicated that PF40 is

a polysaccharide mainly composed of glucose with a small amount of

galactose.

Establishment of an IR-BNL CL.2 cell

model

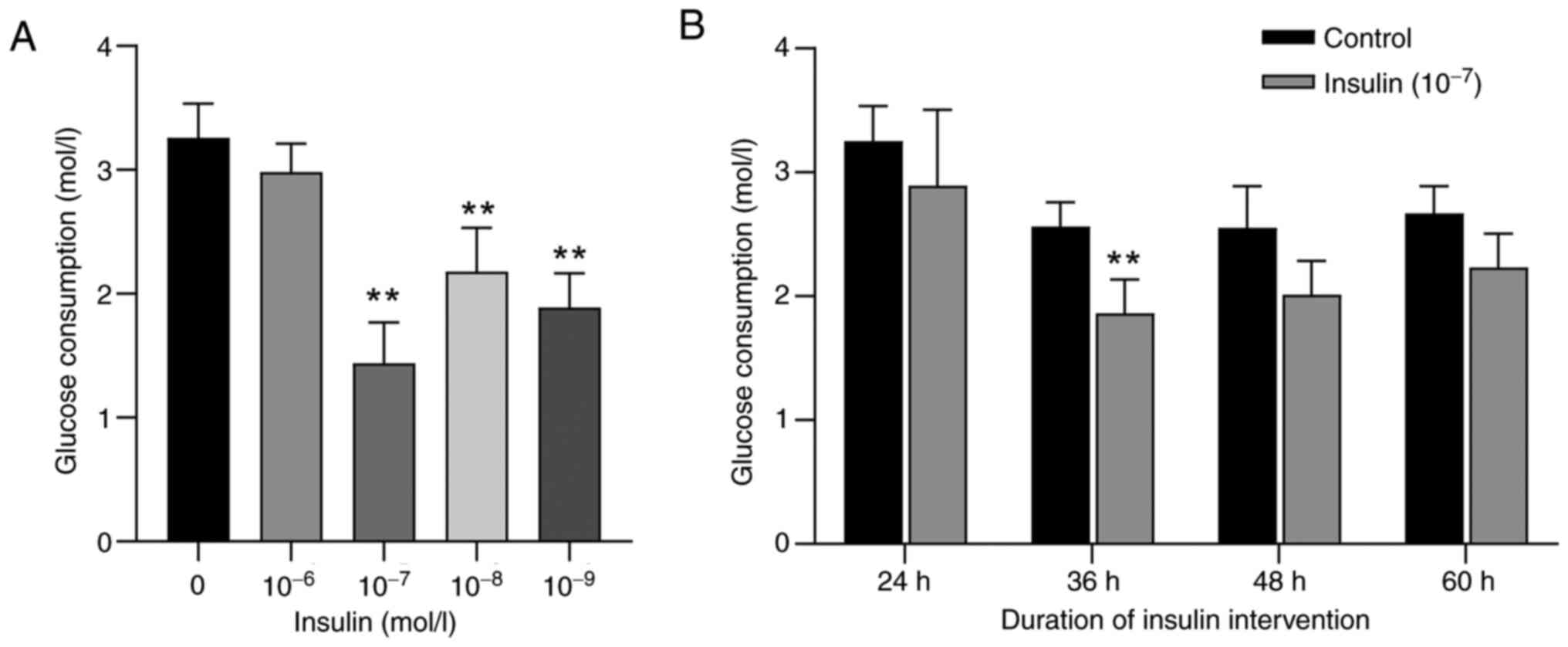

To establish an IR cell model, BNL CL.2 cells were

treated with a high concentration of insulin. To determine the

optimal insulin concentration, BNL CL.2 cells were exposed to

insulin at concentrations ranging from 1×10−6 to

1×10−9 mol/l. As shown in Fig. 1A, compared with in the control

group, the 1×10−7 to 1×10−9 mol/l

insulin-treated groups exhibited significantly inhibited glucose

consumption in BNL CL.2 cells (P<0.01). The 1×10−7

mol/l insulin treatment exhibited the most pronounced inhibitory

effect, reducing glucose consumption to 1.44±0.32 mol/l, which

represents a 55.8% decrease from the control group (3.26±0.28

mol/l) (P<0.01). Therefore, 1×10−7 mol/l was selected

as the optimal insulin concentration. Subsequently, the effects of

varying exposure durations of 1×10−7 mol/l insulin on

glucose consumption in cells was examined (Fig. 1B). Following treatment with

1×10−7 mol/l insulin for 24, 36, 48 and 60 h, glucose

consumption decreased by 11.08, 27.11, 21.18 and 16.48%,

respectively, compared with that in the control group, with a

significant reduction observed at 36 h. These results indicated

that treatment with 1×10−7 mol/l insulin for 36 h

represented the optimal conditions for inducing insulin resistance

in BNL CL.2 cells.

Notably, a non-linear relationship between insulin

concentration and glucose consumption was observed in BNL CL.2

cells (Fig. 1). While low

concentrations of insulin significantly promoted glucose uptake,

higher concentrations did not further enhance glucose consumption

and even showed a plateau or decline in effect. This may be due to

insulin receptor desensitization, or negative feedback regulation

induced by prolonged or excessive insulin exposure. At high doses,

insulin can trigger signaling attenuation through mechanisms such

as increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1, thereby impairing

downstream PI3K/AKT pathway activation and reducing glucose

utilization efficiency. This phenomenon is consistent with

previously reported insulin-induced insulin resistance in

hepatocyte models (30).

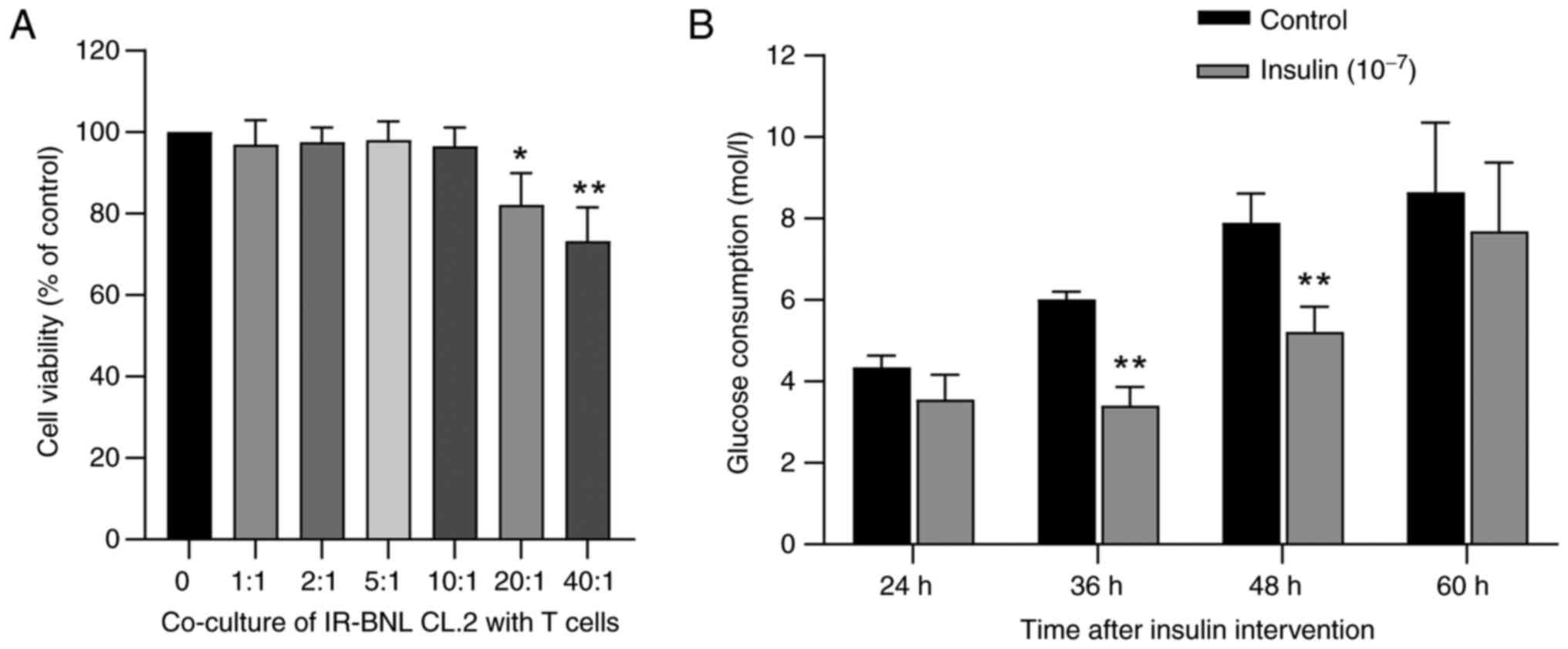

Stability of the IR-BNL CL.2

model

To evaluate the stability of the insulin resistance

cell model, IR-BNL CL.2 cells were continuously monitored following

insulin treatment. As shown in Fig.

2B, compared with that in the control group, glucose

consumption in cells pretreated with 1×10−7 mol/l

insulin was significantly reduced at 36 and 48 h after insulin

removal (P<0.01). Notably, at the final observation point of 60

h, although glucose consumption in the insulin-treated group

remained lower than that in the control group, this difference was

no longer statistically significant (P>0.05). This result

suggested that the insulin resistance model remains stable for up

to 48 h after insulin withdrawal but may begin to undergo partial

self-repair by 60 h. Thus, subsequent experiments were performed

within a 48-h time period following the establishment of the

model.

Biocompatibility of T cells with

IR-BNL CL.2

Isolated CD4+ T cells (Fig. S3) were co-cultured with IR-BNL

CL.2 cells at varying ratios (1:1, 2:1, 5:1, 10:1, 20:1 and 40:1)

to assess the biocompatibility of the co-culture system. A CCK-8

assay was used to evaluate the viability of IR-BNL CL.2 cells

(Fig. 2A). When the ratio of

CD4+ T cells was ≤10:1 there was no significant impact

on IR-BNL CL.2 cell viability (P>0.05). However, at ratios of

20:1 and 40:1, the viability of IR-BNL CL.2 cells was significantly

reduced (both P<0.01; 82.11 and 73.26% of the control group,

respectively). Therefore, a CD4+ T cell to IR-BNL CL.2

cell ratio of 10:1 was selected for subsequent experiments.

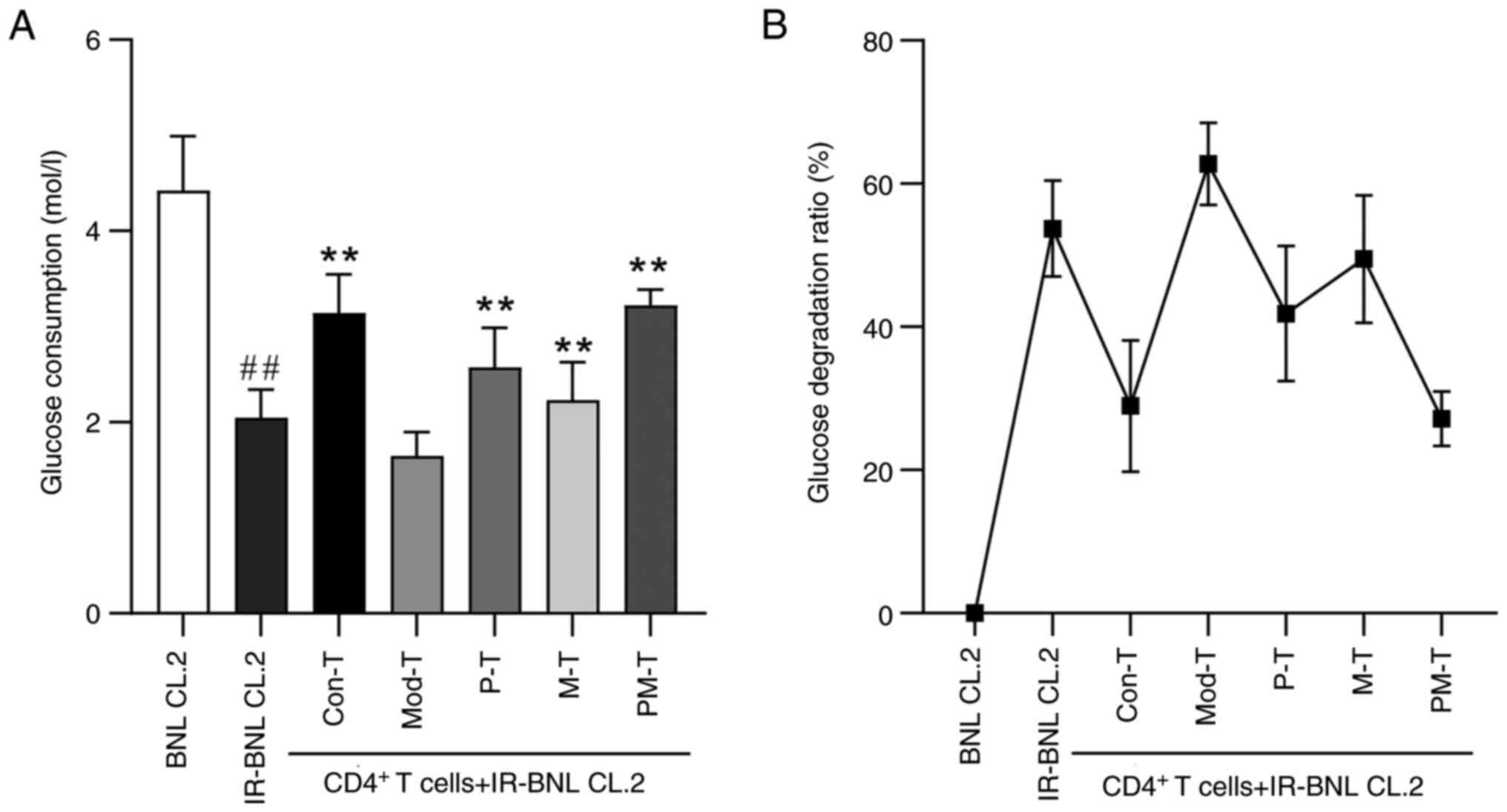

Glucose consumption of IR-BNL CL.2

cells in response to different CD4+ T-cell

treatments

CD4+ T cells subjected to various

treatments were co-incubated with IR-BNL CL.2 cells to assess their

impact on glucose consumption in the IR-BNL CL.2 cells. As shown in

Fig. 3, glucose consumption was

significantly reduced in IR-BNL CL.2 cells compared with that in

normal BNL CL.2 cells (P<0.05), confirming the successful

establishment of the IR model. In the co-culture experiments,

glucose consumption in IR-BNL CL.2 cells was markedly lower in the

Mod-T group than in the Con-T group (P<0.01). Notably,

co-culture of IR-BNL CL.2 cells with P-T, M-T or PM-T significantly

improved glucose metabolism compared with the Mod-T group. The PM-T

group showed the most pronounced effect, with glucose consumption

nearly doubled compared with that in the Mod-T group

(P<0.01).

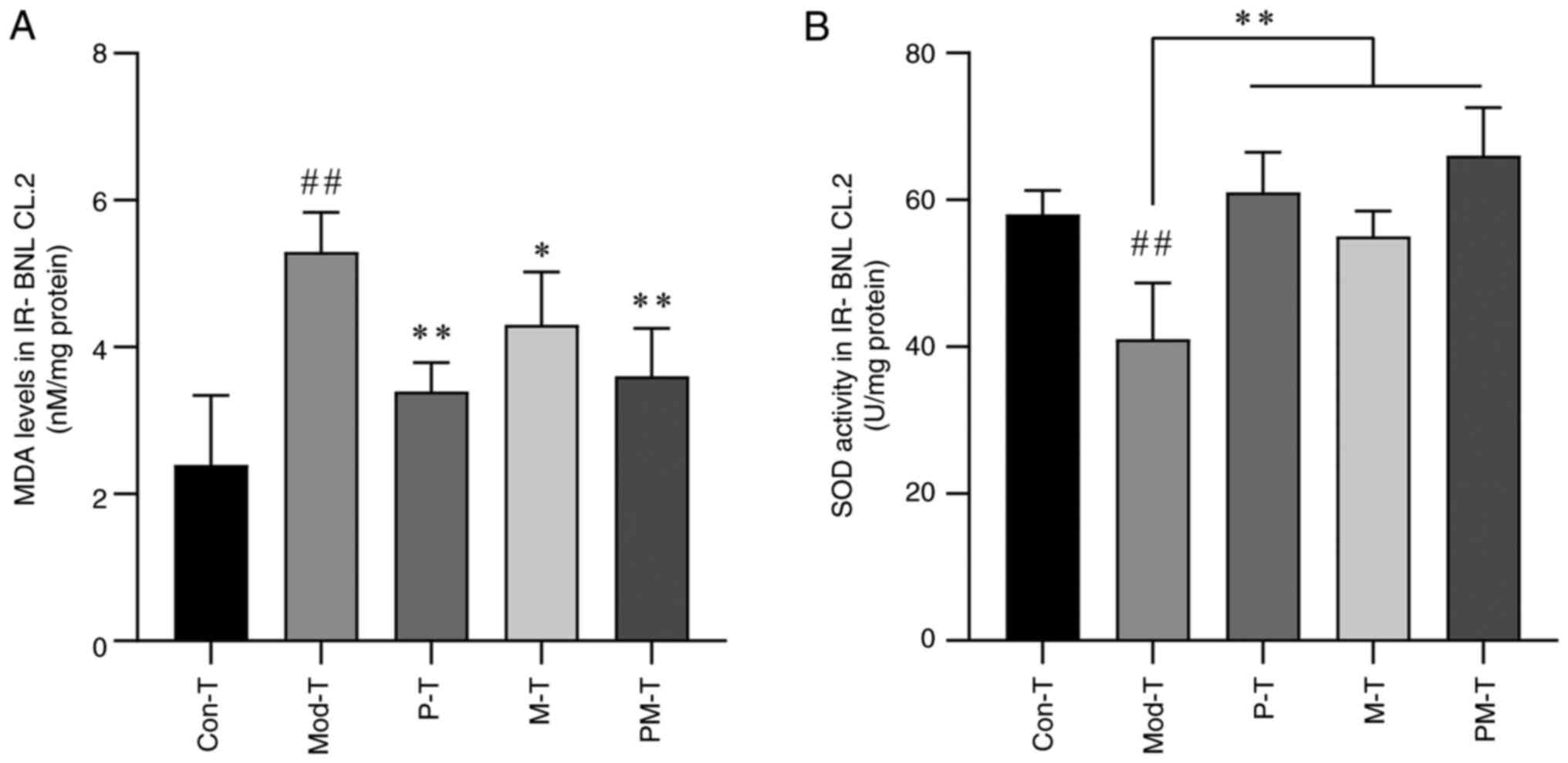

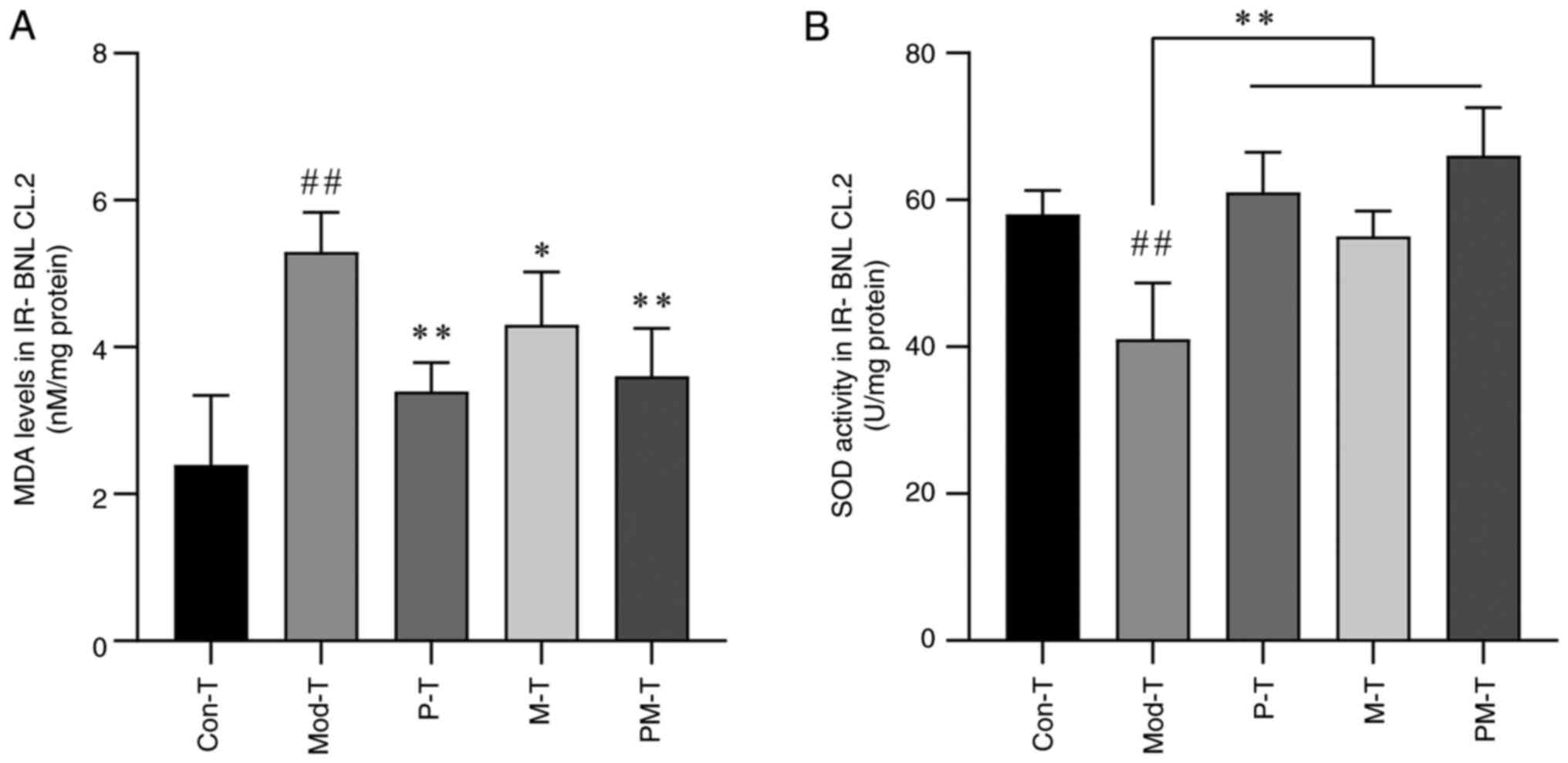

Oxidative stress of IR-BNL CL.2 cells

in response to different CD4+ T-cell treatments

To evaluate the oxidative stress status in IR-BNL

CL.2 cells across different treatment groups, MDA levels and SOD

activity were measured. MDA, a primary product of lipid

peroxidation, reflects the extent of cellular oxidative damage,

whereas SOD, a key antioxidant enzyme, indicates cellular

antioxidant capacity (31). As

shown in Fig. 4, MDA levels in

IR-BNL CL.2 cells were significantly elevated in the Mod-T group

compared with those in the Con-T group (P<0.01), whereas SOD

activity was significantly reduced (P<0.01). Among the treatment

groups, both the P-T and PM-T groups significantly lowered MDA

levels (P<0.05), and although the M-T group also showed a trend

toward reducing MDA, the difference was not statistically

significant compared with the Mod-T group (P>0.05). All

treatment groups exhibited notable improvements in SOD activity

(P<0.01), with the PM-T group showing the most significant

effect, nearly restoring SOD activity to control levels.

| Figure 4.Effects of differently treated

CD4+ T cells on (A) MDA and (B) SOD levels in IR-BNL

CL.2 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n=5.

##P<0.01 vs. Con-T group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

Mod-T group. MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase;

IR-BNL CL.2, insulin-resistant BNL CL.2; Con-T, control; Mod-T,

model; P-T, PF40; M-T, metformin; PM-T, combined PF40 and

metformin. |

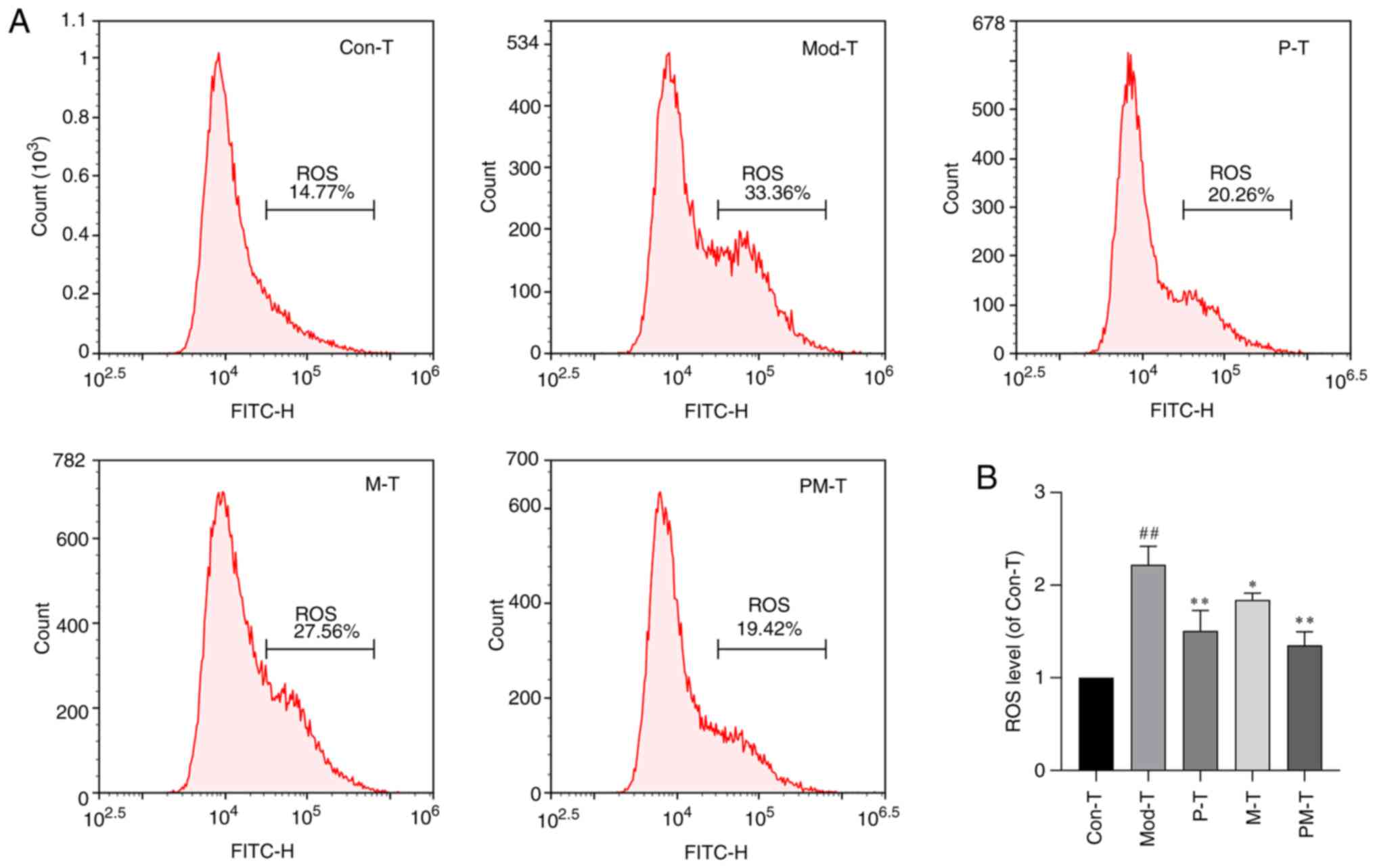

Subsequently, intracellular ROS levels in IR-BNL

CL.2 cells co-cultured with CD4+ T cells from various

treatment groups were assessed using flow cytometry. As shown in

Fig. 5, ROS levels were

significantly elevated in the Mod-T group compared with those in

the Con-T group (P<0.01), reaching approximately double that of

the control levels. Both the P-T and M-T treatment groups

significantly reduced ROS levels (P<0.05). Furthermore, the

combined treatment group (PM-T) exhibited the strongest inhibitory

effect on ROS levels, restoring them to close to the control levels

(P<0.01).

Apoptosis of IR-BNL CL.2 cells in

response to different CD4+ T-cells treatments

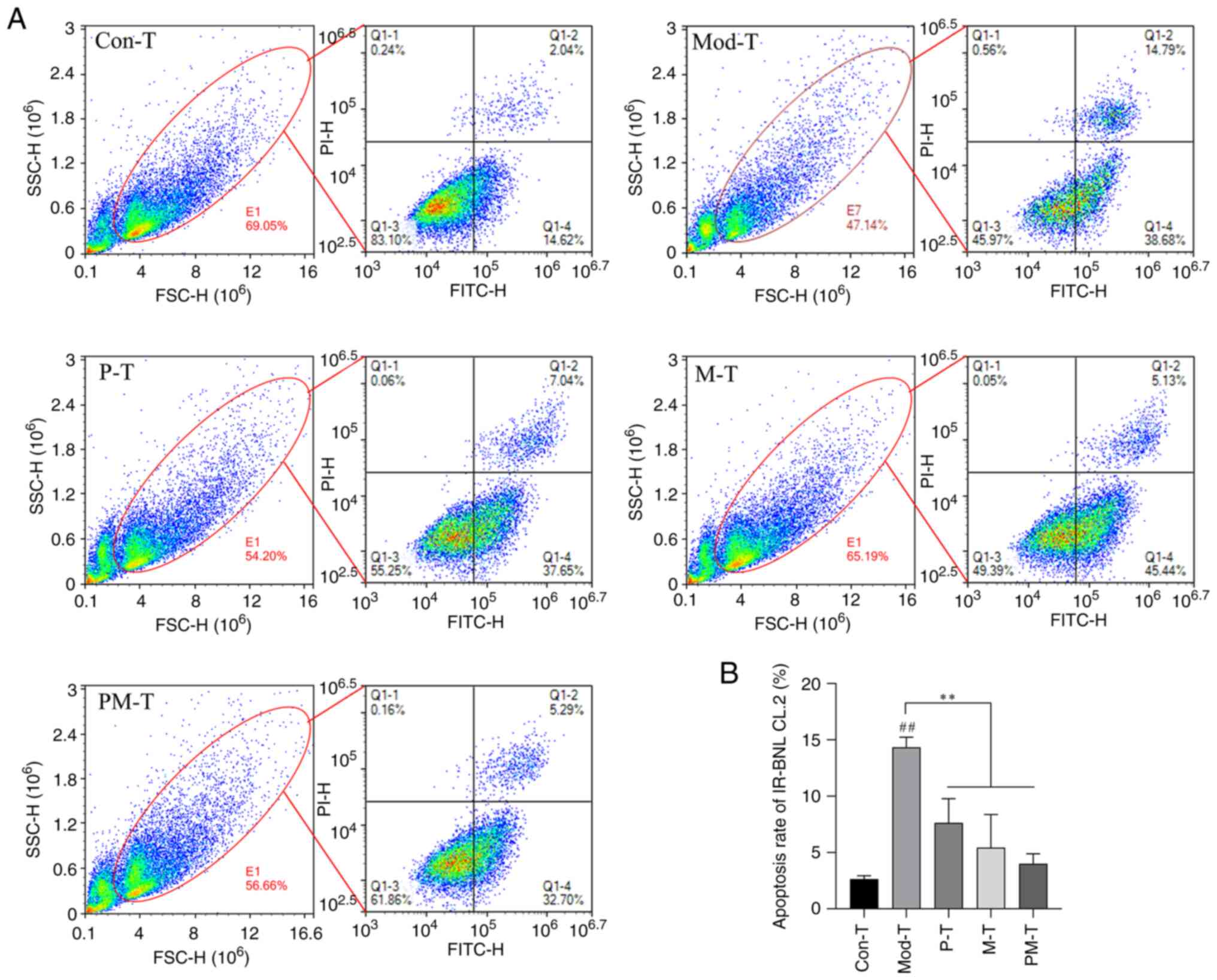

FSC (forward scatter) and SSC (side scatter) plots

were used to assess cell populations, where FSC reflects cell size

and SSC indicates cell granularity or internal complexity. To

investigate the impact of CD4+ T cells from different

treatment groups on IR-BNL CL.2 cell apoptosis, the apoptotic rate

of IR-BNL CL.2 cells in the co-culture system was measured using

flow cytometry (Fig. 6). The

results showed that the Mod-T group exhibited significantly

increased apoptosis of IR-BNL CL.2 cells compared with that in the

Con-T group (P<0.01). This finding indicated that

CD4+ T cells in a T2DM state may exacerbate insulin

resistance by promoting the apoptosis of IR-BNL CL.2 cells.

Following P-T or M-T treatment, the apoptosis rates in IR-BNL CL.2

cells were significantly reduced (P<0.01). Notably, the PM-T

group showed the most pronounced protective effect, reducing the

rate of apoptosis to close to that of control levels (P<0.01).

These findings suggested that PF40 and metformin may mitigate

apoptosis in IR-BNL CL.2 cells through functional modulation of

CD4+ T cells, with a potential synergistic effect.

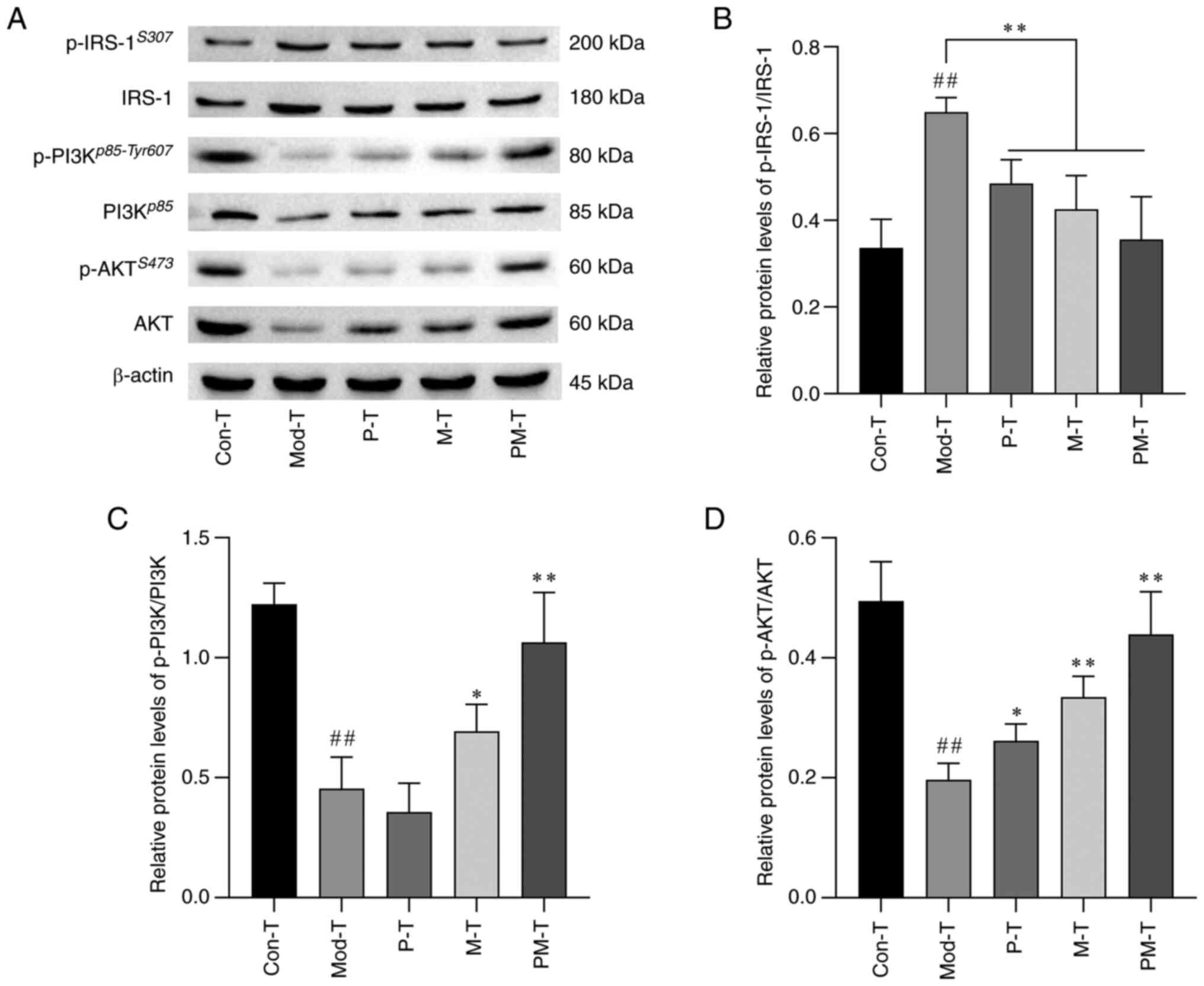

Expression of IRS-1/PI3K/AKT and

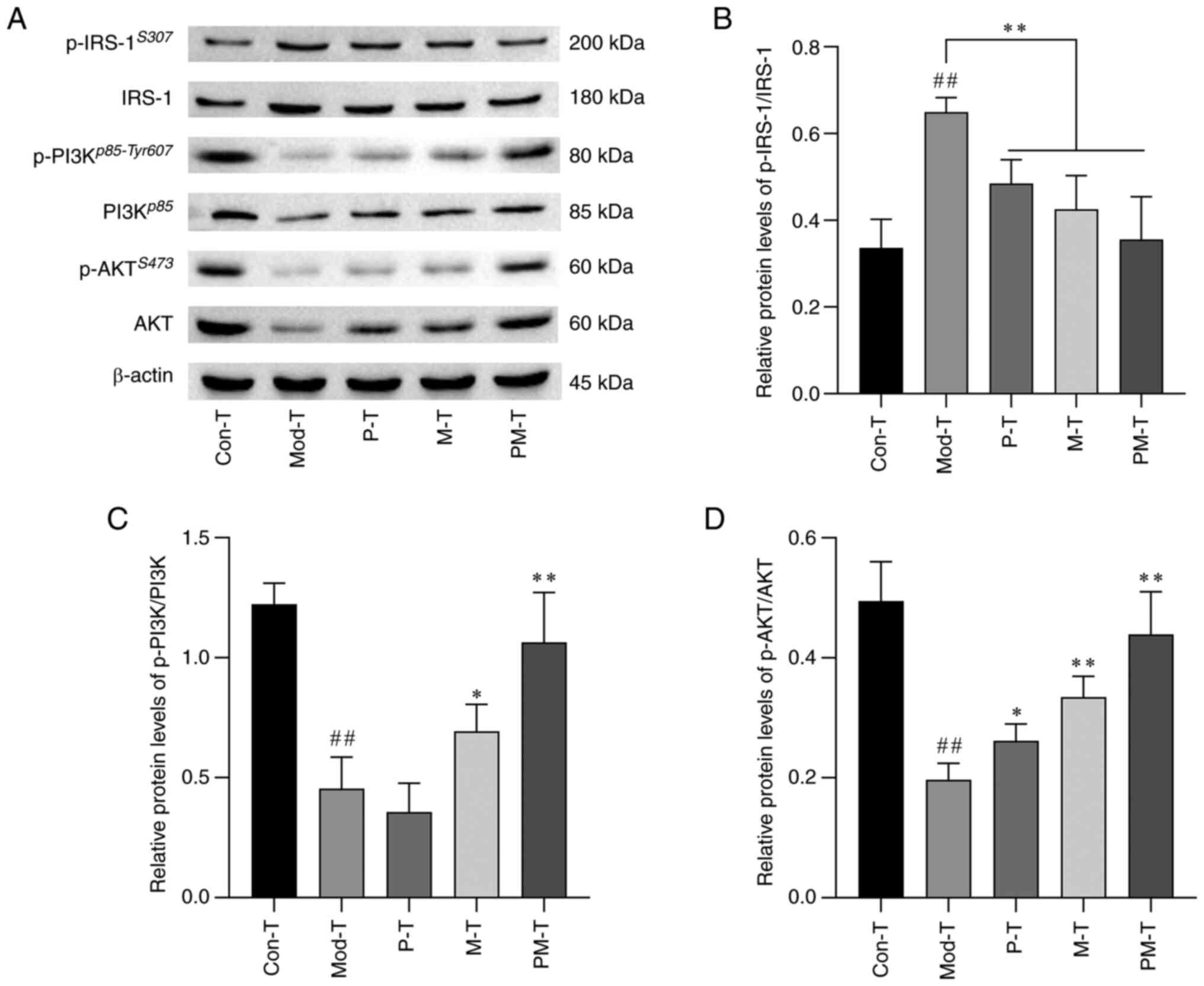

phosphorylated proteins in IR-BNL CL.2 cells

The expression of insulin signaling markers in

IR-BNL CL.2 cells was assessed using western blot analysis

(Fig. 7). The results indicated

that in the Mod-T group IR-BNL CL.2 cells exhibited an impaired

insulin signaling cascade, as evidenced by increased

phosphorylation of IRS-1Ser307 (P<0.01), and

significantly decreased phosphorylation of

PI3Kp58-Tyr607 and AKTS473 (both P<0.01),

compared with that in the Con-T group. By contrast, the PM-T group

showed a marked reduction in p-IRS-1Ser307 (P<0.01),

and a significant increases in p-PI3Kp58-Tyr607 and

p-AKTS473 levels (P<0.01) compared with in the Mod-T

group. These findings suggested that P-T or M-T may activate the

PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by reducing p-IRS-1Ser307

expression, effectively increasing insulin sensitivity and

improving insulin resistance.

| Figure 7.Effects of differently treated

CD4+ T cells on the IRS-1/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in

IR-BNL CL.2 cells. (A) Representative western blot images showing

protein and p-protein expression levels of IRS-1, PI3K and AKT

across the different treatment groups. Relative protein expression

levels of (B) p-IRS-1/IRS-1, (C) p-PI3K/PI3K, and (D) p-AKT/AKT.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD, n=3. ##P<0.01

vs. Con-T group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. Mod-T group. Con-T,

control; Mod-T, model; P-T, PF40; M-T, metformin; PM-T, combined

PF40 and metformin; IRS-1, insulin receptor substrate-1; p-,

phosphorylated. |

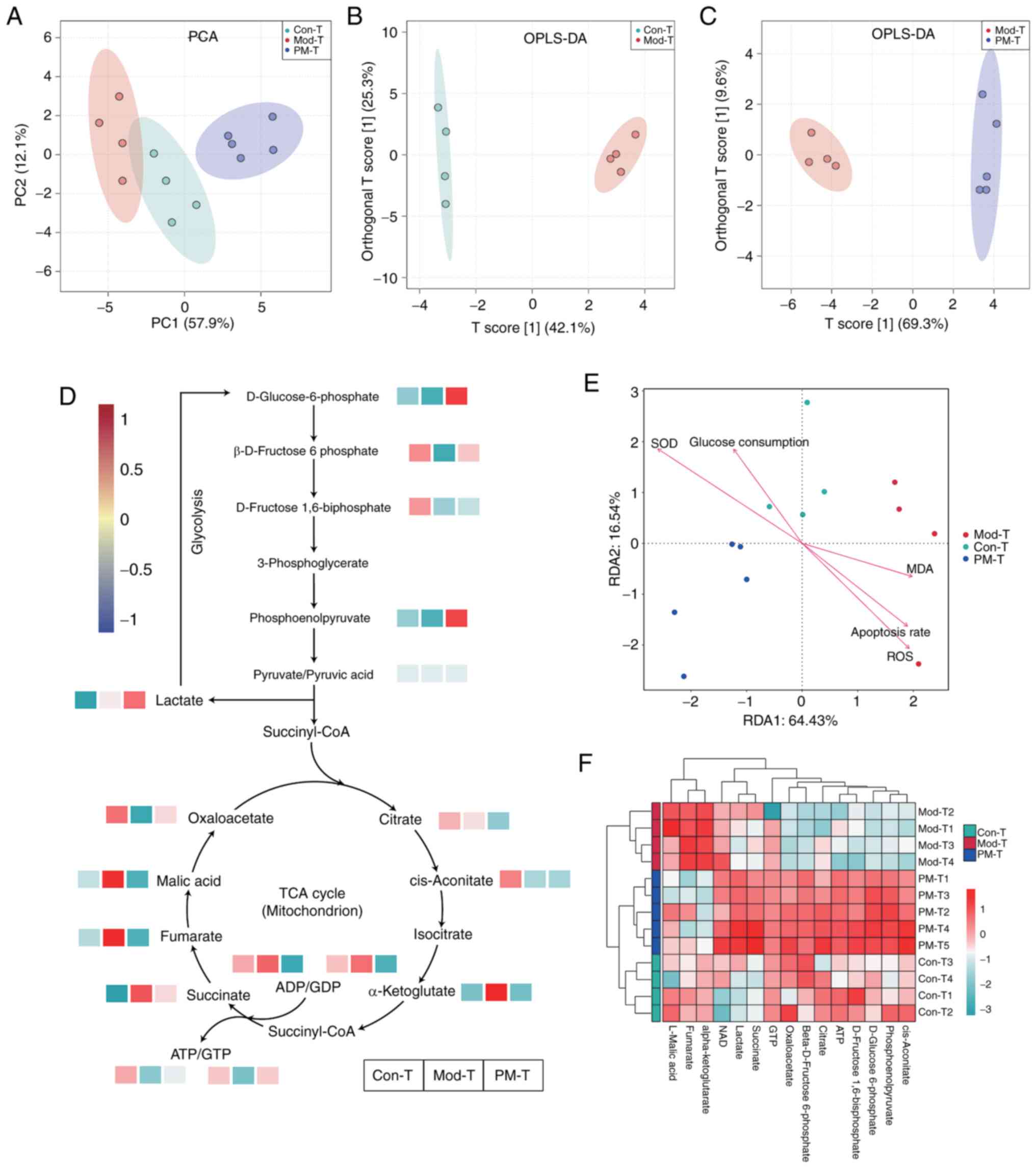

Energy metabolism in IR-BNL CL.2 cells

in response to different CD4+ T-cell treatments

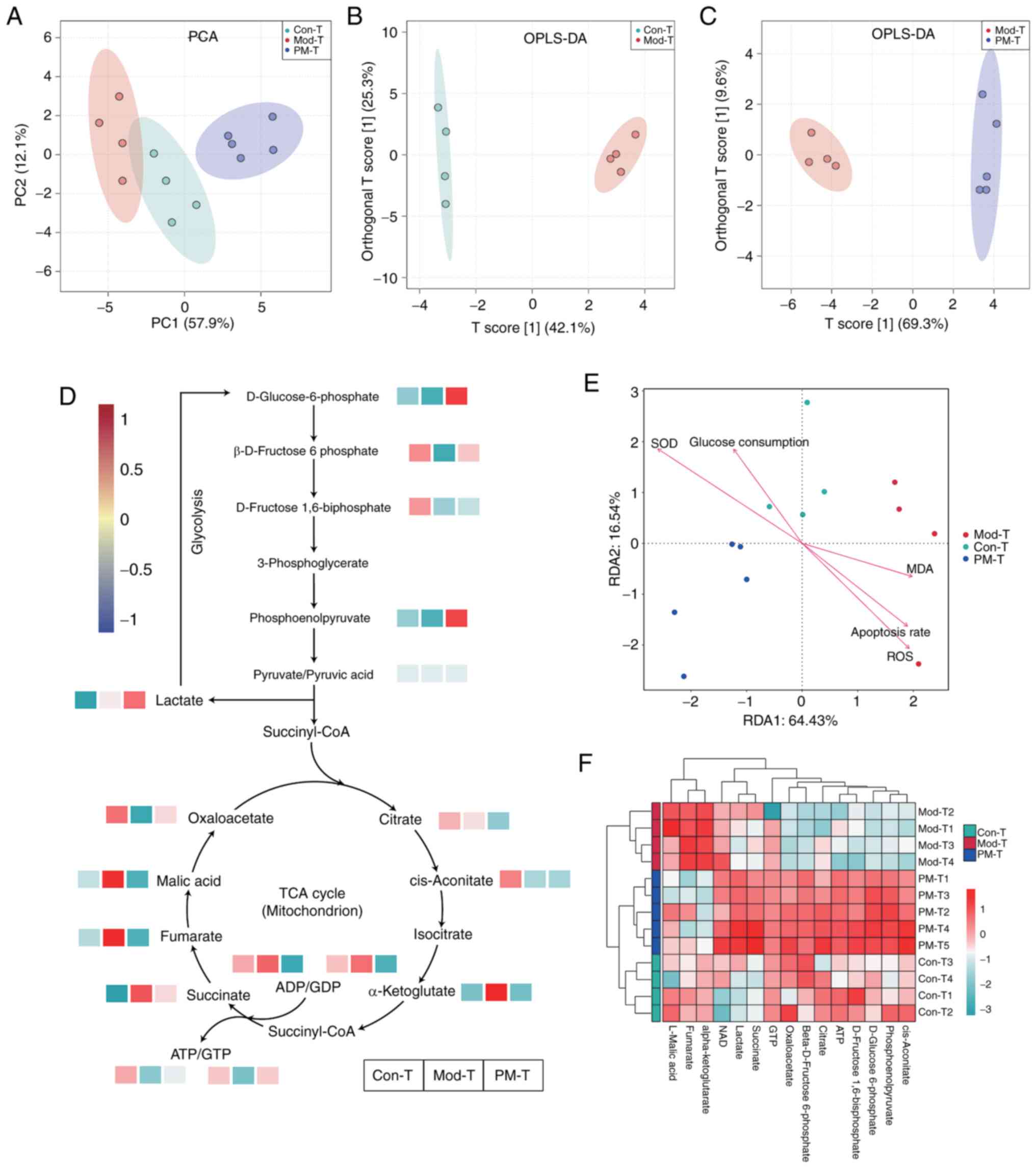

UPLC-MS/MS was used to investigate changes in energy

metabolism-related metabolites in IR-BNL CL.2 cells. To streamline

data analysis, the Con-T, Mod-T and PM-T groups were selected. To

explore metabolic differences between samples, PCA and OPLS-DA were

performed (Fig. 8A-C). The PCA

score plot indicated a clear separation trend among the three

groups on PC1 (57.9%) and PC2 (12.1%). The OPLS-DA analysis between

the Con-T and Mod-T groups showed that the predictive component T

score and orthogonal component T score explained 42.1 and 25.3% of

the variance, respectively. In the OPLS-DA analysis between the

Mod-T and PM-T treatment groups, the predictive component T score

and orthogonal component T score explained 69.3 and 9.6% of the

variance, respectively. Both OPLS-DA score plots displayed good

group separation, indicating significant metabolic alterations due

to insulin resistance modeling, while PM-T treatment effectively

modulated these metabolic abnormalities.

| Figure 8.Targeted energy metabolomics analysis

of the different treatment groups. (A) PCA of metabolites in the

different treatment groups. OPLS-DA was performed between the (B)

Con-T and Mod-T groups, and the (C) Mod-T and PM-T groups. (D) Heat

maps showing the relative content of key glycolysis products across

different treatment groups. (E) Redundancy analysis. Data are

presented as the mean ± SD, n=4 or 5. (F) Heat map showing the

relative content of key TCA cycle products across different

treatment groups. Mod-T. Con-T, control; Mod-T, model; P-T, PF40;

M-T, metformin; PM-T, combined PF40 and metformin; PCA, principal

component analysis; OPLS-DA, orthogonal partial least squares

discriminant analysis; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. |

As shown in Fig. 8D and

F, heatmaps illustrated the levels of key metabolites involved

in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and glycolysis pathways

within IR-BNL CL.2 cells. Compared with in the Con-T group, the

Mod-T group exhibited significant changes in key metabolites within

the TCA cycle and glycolysis. In the TCA cycle, α-ketoglutarate,

succinate, fumarate and malic acid levels were markedly increased,

while oxaloacetate levels were markedly decreased. In the

glycolysis pathway, levels of D-glucose-6-phosphate and

β-D-fructose-6-phosphate were substantially reduced in the Mod-T

group. These results suggested that the Mod-T group may compensate

for impaired glycolysis by upregulating key metabolites in the TCA

cycle to maintain cellular energy balance. The PM-T treatment group

an opposing metabolic pattern was detected compared with that in

the Mod-T group, particularly regarding levels of α-ketoglutarate

and D-glucose-6-phosphate, suggesting that PM-T exerts therapeutic

effects by modulating the metabolic balance between the TCA cycle

and glycolysis pathways.

RDA showed that the first and second axes explained

64.43 and 16.54% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 8E). The RDA ordination plot revealed

clear separation among the Con-T, Mod-T and PM-T groups. RDA

revealed that the Mod-T group was positively associated with ROS

and apoptosis rate, whereas the PM-T group was positively

associated with SOD activity and negatively with MDA levels,

indicating that PM-T treatment improves oxidative stress by

enhancing antioxidant capacity and reducing lipid peroxidation

damage.

Discussion

In the present study, an IR-BNL CL.2 cell model was

established and co-incubated with intestinal CD4+ T

cells treated with PF40, metformin or both. The results showed that

P-T reduced oxidative stress in IR-BNL CL.2 cells by lowering ROS

and MDA levels, while enhancing SOD activity, which reflected

improved antioxidant defense. Oxidative stress is a known factor in

insulin resistance, primarily by affecting glucose metabolism and

the insulin signaling pathways, thereby accelerating the

progression of insulin resistance (31). By mitigating oxidative stress, P-T

co-culture restored the redox balance and improved insulin

sensitivity. The findings of the present study emphasized that

CD4+ T cells may serve a critical role in alleviating

insulin resistance in IR-BNL CL.2 cells. This aligns with

accumulating evidence that immune cells, particularly

CD4+ T lymphocytes, notably impact metabolic activity

and inflammation in the context of insulin resistance (32,33).

The liver is a key organ involved in glucose

metabolism and a primary target in insulin resistance (34,35).

Establishing a stable and reliable IR cell model is crucial for

screening anti-insulin resistance drugs and studying their

mechanisms of action. Murine embryonic liver cells are widely used

as model cells to investigate hepatic insulin resistance, and

insulin serves as an inducer for developing IR cell models

(36,37). In developing the IR-BNL CL.2 cell

model, a marked reduction in glucose consumption in response to

optimal induction conditions was observed (1×10−7 mol/l

insulin for 36 h), and model stability was confirmed over 48 h.

Impaired glucose consumption and elevated oxidative stress levels

in IR-BNL CL.2 cells are consistent with previous findings,

validating the stability and reliability of the model (36,38).

When co-cultured with P-T cells, glucose uptake was restored in

IR-BNL CL.2 cells. The present study also investigated the

biocompatibility of CD4+ T cells with IR-BNL CL.2 cells

at specific co-culture ratios, and the results showed that the

optimal non-cytotoxic ratio for co-culturing CD4+ T

cells with IR-BNL CL.2 cells was 10:1. The establishment of this

co-culture system provides a basis for further exploration of the

mechanisms by which CD4+ T cells modulate insulin

resistance in IR-BNL CL.2 cells.

In the current study, the murine hepatocyte-derived

BNL CL.2 cell line was selected to establish an insulin resistance

model for co-culture with CD4+ T cells isolated from

PF40-treated rats with T2DM. This choice was made to maintain

taxonomic proximity within the Rodentia order and to minimize

potential immune incompatibility or non-specific activation that

could result from co-culturing rodent-derived immune cells with

more distantly related species. While BNL CL.2 cells are embryonic

in origin and do not fully recapitulate the metabolic complexity of

human hepatocytes, they are widely used in studies of hepatic

insulin signaling (39), oxidative

stress (40) and energy metabolism

(41). Nevertheless, the

limitations of this model in mimicking human pathophysiology should

be acknowledged, and future studies incorporating humanized

hepatocyte-immune co-culture systems or liver organoids will be

necessary to validate and extend the findings in a translational

context. Moreover, the T cell-to-hepatocyte ratio employed in the

co-culture system (10:1) exceeds physiological levels typically

found in vivo. This elevated ratio was selected based on the

biocompatibility testing of different CD4+ T

cell/IR-hepatocyte ratios, to ensure that CD4+ T cells

could exert sufficient paracrine and immunomodulatory effects on IR

hepatocytes without inducing excessive cytotoxicity. While this

setup enhances the detection of immunometabolic interactions in

vitro, it may not fully replicate the cellular microenvironment

of the gut-liver axis under physiological or pathological

conditions. Therefore, the data should be interpreted as

proof-of-concept findings, and future studies employing more

physiologically relevant cell ratios or three-dimensional

co-culture models are warranted to confirm the observed

effects.

SOD is a critical antioxidant enzyme that

effectively scavenges superoxide anions, thereby reducing oxidative

stress-induced cellular damage. In the pathophysiology of T2DM,

prolonged hyperglycemic conditions lead to a marked elevation in

intracellular ROS levels, exacerbating oxidative stress, which

further exacerbates insulin resistance and cellular injury

(42,43). P-T intervention significantly

increased SOD activity in IR-BNL CL.2 cells in the present study,

suggesting that P-T alleviated oxidative stress by enhancing

cellular antioxidant capacity. Furthermore, the observed reduction

in MDA levels supports the antioxidant role of P-T. As a marker of

lipid peroxidation, decreased MDA levels indicate that P-T may

reduce lipid peroxidation under IR conditions, thereby lowering the

risk of oxidative membrane damage. Lipid peroxidation, a

consequence of oxidative stress, destabilizes cell membranes,

increases permeability and impairs cell function (44). Compared with in the Mod-T group,

the P-T group exhibited a significant reduction in MDA levels,

suggesting that P-T may serve a crucial role in inhibiting lipid

peroxidation and preserving membrane integrity.

Oxidative stress is one of the primary inducers of

cellular apoptosis, with ROS acting as reactive molecules that

cause oxidative damage to membrane lipids, proteins and DNA under

oxidative stress, ultimately triggering apoptotic pathways

(45). In the present study, P-T

treatment significantly reduced ROS levels in IR-BNL CL.2 cells,

along with a decrease in the lipid peroxidation marker MDA. This

finding indicated that P-T not only exhibits antioxidant properties

but may also inhibit the progression of oxidative damage by

reducing ROS. Apoptosis assays of IR-BNL CL.2 cells further

validated these findings, with Mod-T showing substantial apoptosis

relative to the Con-T group, whereas P-T treatment significantly

reduced apoptotic cell counts. Thus, P-T may prevent apoptosis

pathway activation by lowering oxidative stress, which is crucial

for mitigating insulin resistance-associated cellular injury.

To further elucidate the potential molecular

mechanisms by which P-T influenced glucose metabolism, the

expression of insulin signaling-related markers in IR-BNL CL.2

cells was examined. Upon binding to its receptor, insulin promotes

glucose uptake through a series of signaling cascades, resulting in

the phosphorylation of IRS proteins at multiple tyrosine residues,

which subsequently activate downstream molecules such as PI3K and

AKT (46). The PI3K/AKT pathway is

a primary regulator of metabolic functions and glucose uptake

induced by insulin (46–48). Activated AKT serves a central role

in regulating various downstream pathways, including those involved

in cell proliferation, protein synthesis and glucose metabolism.

Phosphorylation of AKT further activates GLUT4, enhancing glucose

uptake in peripheral tissues. IRS-1, a major IRS subtype, is

closely associated with glucose homeostasis in the liver; however,

phosphorylation of IRS-1 at the Ser307 residue significantly

diminishes its activity, which is linked to the inhibition of

insulin signaling (49,50). Western blot analysis showed that in

the Mod-T group, levels of p-IRS-1Ser307 were markedly

elevated, whereas PI3Kp85-Tyr607 and

p-AKTSer473 levels were notably reduced, indicating

impairment of the insulin signaling cascade. Treatment with P-T or

M-T significantly reduced p-IRS-1Ser307 levels, enhanced

PI3Kp85-Tyr607 expression, and increased AKT

phosphorylation, thereby promoting glucose uptake.

Phosphorylation of AKT has a pivotal role in glucose

uptake and utilization by activating key glycolytic enzymes, such

as glucokinase, which facilitates glucose phosphorylation, an

essential step for entry into glycolysis and the TCA cycle

(51,52). During a state of insulin

resistance, reduced AKT phosphorylation may lead to decreased

glucokinase activity, directly lowering the levels of

glucose-6-phosphate (53). In the

present study, reduced glucose-6-phosphate levels were observed in

the Mod-T group. This reduction disrupted the TCA cycle, which

could impair glycolytic input, resulting in decreased ATP

production efficiency and subsequent ROS accumulation. In the

IR-BNL CL.2 model group, elevated ROS levels and reduced TCA cycle

intermediates suggested mitochondrial stress, compromising cellular

bioenergetics and promoting apoptosis. This increase in apoptosis

aligned with the results from RDA, where elevated ROS and lipid

peroxidation were associated with higher apoptotic rates. Thus,

disruption of the glucokinase-AKT pathway highlights links among

glucose metabolism disorders, oxidative stress and cell

survival.

The present study used targeted energy metabolomics

analysis to reveal differences in energy metabolism pathways in

IR-BNL CL.2 cells among the different treatment groups. In the

Mod-T group, a notable increase in multiple key metabolites within

the TCA cycle was observed, particularly α-ketoglutarate,

succinate, fumarate and malic acid, which suggested the presence of

a compensatory regulatory mechanism in response to metabolic

dysregulation. Studies have shown that the accumulation of TCA

cycle metabolites is often associated with mitochondrial

dysfunction (54,55). Concurrently, the significant

reduction of glycolytic intermediates (such as

D-glucose-6-phosphate and β-D-fructose-6-phosphate) in the Mod-T

group suggested that glycolysis may be suppressed. This metabolic

shift aligns with previously reported characteristics of metabolic

disease models (56). Notably, the

PM-T treatment group exhibited metabolic features that were the

opposite of those in the Mod-T group. Following PM-T treatment, the

levels of glycolytic intermediates, such as D-glucose-6-phosphate

and phosphoenolpyruvate, were increased, and TCA cycle metabolites

approached normal levels. This finding suggested that PM-T may

improve cellular energy metabolism by modulating the metabolic

balance between the TCA cycle and glycolysis pathways.

RDA provided further biochemical evidence supporting

the role of PM-T in ameliorating oxidative stress. The separation

between the Mod-T and PM-T groups on the RDA plot, along with the

positive association between the Mod-T group and elevated ROS

levels and apoptosis rates, indicated that Mod-T-induced metabolic

stress may be associated with increased oxidative damage. However,

PM-T treatment showed a strong positive association with SOD

activity and a negative association with MDA content, indicating

enhanced antioxidant defense capacity and reduced lipid

peroxidation in treated cells. This transition in oxidative status

may represent a key mechanism by which PM-T reduces cellular stress

and prevents apoptosis. Collectively, PM-T may exert its protective

effects through rebalancing energy metabolism and enhancing

antioxidant responses, potentially alleviating functional

impairments in IR cells.

The combined treatment of CD4+ T cells

with PF40 and metformin demonstrated synergistic effects on

antioxidant activity and apoptosis inhibition. Compared with M-T,

the PM-T group exhibited markedly enhanced antioxidant capacity and

reduced ROS levels, which may be attributed to the complementary

mechanisms of PF40 and metformin. PF40 primarily reduces oxidative

stress through its antioxidant properties, whereas metformin

improves cellular metabolism by modulating the insulin signaling

pathway (10,57). Thus, their combined application may

alleviate insulin resistance and improve cell status through

several different mechanisms. Although metformin is effective in

reducing insulin resistance, adjunct therapy with natural

antioxidants may further enhance therapeutic outcomes and

potentially reduce side effects associated with metformin

monotherapy (57,58). It has been reported that mushroom

polysaccharide NAP-3 can enhance the efficacy of metformin in lipid

and glucose metabolism in mice with T2DM by reshaping the

homeostasis of the gut microbiota community (59). The Astragalus polysaccharide

APS-D1 has also been shown to reduce the required dosage of

metformin by enriching Staphylococcus lentus, which promotes

fatty acid oxidation and inhibits gluconeogenesis (60).

In the present study, the effects of differentially

treated intestinal immune cell subsets on insulin resistance were

investigated. The results revealed that modulating the homeostasis

of CD4+ T cells in the gut immune system may notably

improve insulin signaling and glucose metabolism in an IR cell

model. This aligns with previous studies highlighting the role of

gut immune cells in metabolic regulation, particularly the

exacerbation of IR by T-cell alterations in inflammatory

environments (61,62). Targeting intestinal immune cells

may present a novel approach for the prevention and treatment of

insulin resistance and metabolic diseases (63). However, the CD4+ T-cell

population in the present study likely includes various subsets,

such as Th1, Th2 and Th17 cells, and Tregs. The specific roles of

these subsets in this process remain unclear. To further elucidate

this mechanism, future studies should employ techniques such as

single-cell sequencing to better understand the contributions of

these immune cell subsets in improving insulin resistance and

reducing apoptosis.

In our previous study, the regulatory effects of

PF40 on CD4+ T-cell subsets, particularly in the balance

between Tregs and Th17 cells were determined (11). PF40 may alleviate immune system

overactivation and reduce insulin resistance by enhancing the

function of Tregs. Tregs serve a critical role in maintaining

immune tolerance and suppressing excessive immune responses,

whereas Th17 cells are typically associated with inflammatory

responses and the development of insulin resistance (3,4). By

modulating the Treg/Th17 balance, PF40 may inhibit Th17 cell

expansion and reduce the inflammation induced by these cells,

thereby improving insulin signaling. Specifically, PF40 may enhance

the secretion of factors such as IL-10 by Tregs, while suppressing

the secretion of IL-17A by Th17 cells, thereby regulating the

immune microenvironment and mitigating insulin resistance caused by

immune activation (11). In the

present study, it was observed that P-T cells suppressed oxidative

stress responses and activated the IRS-1/PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway. These findings not only provide evidence for the potential

mechanisms through which PF40 maintains immune balance but also

highlight its promising application prospects in the treatment of

insulin resistance.

While the current study provides experimental data

on the role of PF40 in alleviating insulin resistance, its

limitations must be considered. First, the present study primarily

relied on in vitro models, and although the IR-BNL CL.2 cell

model has been widely validated in insulin resistance research, it

differs from in vivo environments, particularly regarding

the dynamic changes in immune cells and tissue-specific responses.

Therefore, future studies should consider validating these findings

in animal models to enhance the biological relevance of the

results. Second, since the study did not delve deeply into the

specific mechanisms of CD4+ T-cell subsets, future

research could employ single-cell sequencing technologies or other

high-throughput analysis methods to explore the roles and

interactions of different T-cell subsets in insulin resistance.

These studies would contribute to a more comprehensive

understanding of PF40-mediated modulation of the immune system and

provide novel insights and strategies for the treatment of insulin

resistance and related metabolic diseases. Finally, although the

combined treatment of PF40 and metformin indicated potential

synergistic effects, the absence of formal synergy calculations

represents a limitation of the present study, and further

quantitative analyses are warranted to substantiate this

interaction.

The present study provides evidence that P-T cells

are conducive to improving immune activation-induced insulin

resistance. However, the precise mechanisms by which PF40 regulates

CD4+ T-cell subset differentiation remain to be

elucidated. It is well known that polysaccharides are characterized

by their high molecular weight and low bioavailability. Our

previous research identified a water-soluble pectic polysaccharide

isolated from Pseudostellaria heterophylla that can be

absorbed through the intestinal mucosa and enter the systemic

circulation (12). Emerging

evidence has suggested that fermentation of Porphyra

haitanensis polysaccharides by Lactiplantibacillus

plantarum markedly reduces their particle size and enhances the

anti-allergic effects both in vitro and in vivo

(21). Fucoidan has also been

shown to markedly modulate the composition and functional output of

the gut microbiota (64,65). Notably, this microbial remodeling

appears to be a key mechanism underpinning the biological activity

of polysaccharides. The reshaped microbiota ferments these complex

carbohydrates, leading to the production of critical metabolites,

particularly short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate,

propionate and butyrate (66).

These SCFAs act as essential signaling molecules and energy

substrates, serving pivotal roles in the differentiation of

intestinal immune cells (67).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

P-T cells significantly enhanced SOD activity, reduced MDA and ROS

levels, and lowered oxidative stress, thereby reducing apoptosis in

the IR-BNL CL.2 cell model. Additionally, these T cells alleviated

insulin resistance by activating the IRS-1/PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway, increasing glucose uptake in IR-BNL CL.2 cells, and

optimizing the TCA cycle and glycolysis. CD4+ T

lymphocytes in intestinal tissue serve a critical role in

PF40-mediated metabolic regulation and are key effector cells in

the action of PF40 in improving insulin resistance. Targeted

modulation of intestinal immune cell homeostasis may represent a

promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of insulin

resistance.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Bianhong Zhang

(Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China) for

their help in data visualization of targeted energy metabolism. The

authors would also like to thank Dr Ye Liu (Fujian Agriculture and

Forestry University, Fuzhou, China) for assisting in the detection

of targeted energy metabolism.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation

of China (grant nos. 82405034, 81872994 and 81903945), a major

scientific and technological innovation project of Fujian

University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no. XJB2022001),

the Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Medical

Institutions of Fujian Province (Fujian University of Traditional

Chinese Medicine), the Construction Project of Quality Evaluation

System for Pseudostellaria heterophylla in Zherong County

Pharmaceutical Development Center (2024), and the Science and

Technology Innovation Special Fund of Fujian Agriculture and

Forestry University (grant no. CXZX2020037A).

Availability of data and materials

The metabolomics data generated in the present

study may be found in the OMIX, China National Center for

Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of

Sciences database under accession number OMIX010841 or at the

following URL: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/release/OMIX010841.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YK and YL conceived and designed the experiments.

YH, LZ, JC and WP analyzed and interpreted the data. YK wrote the

manuscript. WL contributed to statistical analysis and manuscript

revision, and JH contributed to experimental design and manuscript

revision. YK and YL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee at Fujian Academy of Chinese Medical

Sciences (Fuzhou, China; approval no. FJATCM-IAEC2020002).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Garg SS, Kushwaha K, Dubey R and Gupta J:

Association between obesity, inflammation and insulin resistance:

Insights into signaling pathways and therapeutic interventions.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 200:1106912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Guzmán-Flores J, Ramírez-Emiliano J,

Pérez-Vázquez V and López-Briones S: Th17 and regulatory T cells in

patients with different time of progression of type 2 diabetes

mellitus. Cent Eur J Immunol. 45:29–36. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kiernan K and MacIver NJ: A novel

mechanism for Th17 inflammation in human type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Trends Endocrinol Metab. 31:1–2. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zhang S, Gang X, Yang S, Cui M, Sun L, Li

Z and Wang G: The alterations in and the role of the Th17/Treg

balance in metabolic diseases. Front Immunol. 12:6783552021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yan JB, Luo MM, Chen ZY and He BH: The

function and role of the Th17/Treg cell balance in inflammatory

bowel disease. J Immunol Res. 2020:88135582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lin Z, Zhang J, Duan T, Yang J and Yang Y:

Trefoil factor 3 can stimulate Th17 cell response in the

development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep. 14:103402024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hu DJ, Shakerian F, Zhao J and Li SP:

Chemistry, pharmacology and analysis of Pseudostellaria

heterophylla: A mini-review. Chin Med. 14:212019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lu F, Yang H, Lin SD, Zhao L, Jiang C,

Chen ZB, Liu YY, Kan YJ, Hu J and Pang WS: Cyclic peptide extracts

derived from pseudostellaria heterophylla ameliorates COPD via

regulation of the TLR4/MyD88 pathway proteins. Front Pharmacol.

11:8502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kan Y, Liu Y, Huang Y, Zhao L, Jiang C,

Zhu Y, Pang Z, Hu J, Pang W and Lin W: The regulatory effects of

Pseudostellaria heterophylla polysaccharide on immune function and

gut flora in immunosuppressed mice. Food Sci Nutr. 10:3828–3841.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hu J, Pang W, Chen J, Bai S, Zheng Z and

Wu X: Hypoglycemic effect of polysaccharides with different

molecular weight of Pseudostellaria heterophylla. BMC Complement

Altern Med. 13:2672013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu Y, Kan Y, Huang Y, Jiang C, Zhao L, Hu

J and Pang W: Physicochemical characteristics and antidiabetic

properties of the polysaccharides from pseudostellaria

heterophylla. Molecules. 27:37192022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chen J, Pang W, Kan Y, Zhao L, He Z, Shi

W, Yan B, Chen H and Hu J: Structure of a pectic polysaccharide

from pseudostellaria heterophylla and stimulating insulin secretion

of INS-1 cell and distributing in rats by oral. Int J Biol

Macromol. 106:456–463. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Brucklacher-Waldert V, Carr EJ, Linterman

MA and Veldhoen M: Cellular plasticity of CD4+ T cells in the

intestine. Front Immunol. 5:4882014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jiménez JM, Contreras-Riquelme JS, Vidal

PM, Prado C, Bastías M, Meneses C, Martín AJM, Perez-Acle T and

Pacheco R: Identification of master regulator genes controlling

pathogenic CD4+ T cell fate in inflammatory bowel disease through

transcriptional network analysis. Sci Rep. 14:105532024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tao L, Liu H and Gong Y: Role and

mechanism of the Th17/Treg cell balance in the development and

progression of insulin resistance. Mol Cell Biochem. 459:183–188.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang M, Chen F, Wang J, Zeng Z, Yang Q and

Shao S: Th17 and Treg lymphocytes in obesity and type 2 diabetic

patients. Clin Immunol. 197:77–85. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Monteiro-Sepulveda M, Touch S, Mendes-Sá

C, André S, Poitou C, Allatif O, Cotillard A, Fohrer-Ting H, Hubert

EL, Remark R, et al: Jejunal T cell inflammation in human obesity

correlates with decreased enterocyte insulin signaling. Cell Metab.

22:113–124. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Garidou L, Pomié C, Klopp P, Waget A,

Charpentier J, Aloulou M, Giry A, Serino M, Stenman L, Lahtinen S,

et al: The gut microbiota regulates intestinal CD4 T cells

expressing RORγt and controls metabolic disease. Cell Metab.

22:100–112. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zi C, He L, Yao H, Ren Y, He T and Gao Y:

Changes of Th17 cells, regulatory T cells, Treg/Th17, IL-17 and

IL-10 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Endocrine. 76:263–272. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wei Y, Jing J, Peng Z, Liu X and Wang X:

Acacetin ameliorates insulin resistance in obesity mice through

regulating Treg/Th17 balance via MiR-23b-3p/NEU1 axis. BMC Endocr

Disorders. 21:572021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cheng Z, Wang SH, Li LY, Zhou YC and Zhang

CY: Fermented Porphyra haitanensis polysaccharides inhibit the

degranulation of mast cell and passive cutaneous anaphylaxis. Food

& Medicine Homology. 3:94200862025.

|

|

22

|

Bradford MM: A rapid and sensitive method

for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing

the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 72:248–254.

1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cai M, Xing H, Tian B, Xu J, Li Z, Zhu H,

Yang K and Sun P: Characteristics and antifatigue activity of

graded polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum separated by cascade

membrane technology. Carbohydr Polym. 269:1183292021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Nataraj A, Govindan S, Ramani P, Subbaiah

KA, Sathianarayanan S, Venkidasamy B, Thiruvengadam M, Rebezov M,

Shariati MA, Lorenzo JM and Pateiro M: Antioxidant, anti-tumour,

and anticoagulant activities of polysaccharide from calocybe indica

(APK2). Antioxidants (Basel). 11:16942022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kim E, Tran M, Sun Y and Huh JR: Isolation

and analyses of lamina propria lymphocytes from mouse intestines.

STAR Protoc. 3:1013662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hu X, Yu Q, Hou K, Ding X, Chen Y, Xie J,

Nie S and Xie M: Regulatory effects of Ganoderma atrum

polysaccharides on LPS-induced inflammatory macrophages model and

intestinal-like Caco-2/macrophages co-culture inflammation model.

Food Chem Toxicol. 140:1113212020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

da Rocha GH, Müller C, Przybylski-Wartner

S, Schaller H, Riemschneider S and Lehmann J: AhR-induced

anti-inflammatory effects on a Caco-2/THP-1 co-culture model of

intestinal inflammation are mediated by PPARγ. Int J Mol Sci.

25:130722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Liu X, Xiang D, Jin W, Zhao G, Li H, Xie B

and Gu X: Timosaponin B-II alleviates osteoarthritis-related

inflammation and extracellular matrix degradation through

inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear

factor-κB pathways in vitro. Bioengineered. 13:3450–3461. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wang W, Huang S, Li S, Li X, Ling Y, Wang

X, Zhang S, Zhou D and Yin W: Rosa sterilis juice alleviated breast

cancer by triggering the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway and

suppressing the Jak2/Stat3 pathway. Nutrients. 16:27842024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Fan X, Tao J, Zhou Y, Hou Y, Wang Y, Gu D,

Su Y, Jang Y and Li S: Investigations on the effects of

ginsenoside-Rg1 on glucose uptake and metabolism in insulin

resistant HepG2 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 843:277–284. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tangvarasittichai S: Oxidative stress,

insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

World J Diabetes. 6:456–480. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu L, Hu J, Wang Y, Lei H and Xu D: The

role and research progress of the balance and interaction between

regulatory T cells and other immune cells in obesity with insulin

resistance. Adipocyte. 10:66–79. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wu H and Ballantyne CM: Metabolic

inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity. Circ Res.

126:1549–1564. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Sakurai Y, Kubota N, Yamauchi T and

Kadowaki T: Role of insulin resistance in MAFLD. Int J Mol Sci.

22:41562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tanase DM, Gosav EM, Costea CF, Ciocoiu M,

Lacatusu CM, Maranduca MA, Ouatu A and Floria M: The intricate

relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), insulin

resistance (IR), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). J

Diabetes Res. 2020:39201962020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Schafer A, Neschen S, Kahle M, Sarioglu H,

Gaisbauer T, Imhof A, Adamski J, Hauck SM and Ueffing M: The

epoxyeicosatrienoic acid pathway enhances hepatic insulin signaling

and is repressed in insulin-resistant mouse liver. Mol Cell

Proteomics. 14:2764–2774. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhou X, Wang LL, Tang WJ and Tang B:

Astragaloside IV inhibits protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B and

improves insulin resistance in insulin-resistant HepG2 cells and

triglyceride accumulation in oleic acid (OA)-treated HepG2 cells. J

Ethnopharmacol. 268:1135562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhong RF, Liu CJ, Hao KX, Fan XD and Jiang

JG: Polysaccharides from Flos Sophorae Immaturus ameliorates

insulin resistance in IR-HepG2 cells by co-regulating signaling

pathways of AMPK and IRS-1/PI3K/AKT. Int J Biol Macromol.

280:1360882024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jiang S, Wu X, Wang Y, Zou J and Zhao X:

The potential DPP-4 inhibitors from Xiao-Ke-An improve the

glucolipid metabolism via the activation of AKT/GSK-3β pathway. Eur

J Pharmacol. 882:1732722020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Kim S, Yoon D, Lee YH, Lee J, Kim ND, Kim

S and Jung YS: Transformation of liver cells by

3-methylcholanthrene potentiates oxidative stress via the

downregulation of glutathione synthesis. Int J Mol Med.

40:2011–2017. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Jobgen WS and Wu G: L-Arginine increases

AMPK phosphorylation and the oxidation of energy substrates in

hepatocytes, skeletal muscle cells, and adipocytes. Amino Acids.

54:1553–1568. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ding W, Yang X, Lai K, Jiang Y and Liu Y:

The potential of therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial

biogenesis for the treatment of insulin resistance and type 2

diabetes mellitus. Arch Pharm Res. 47:219–248. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Roden M, Petersen KF and Shulman GI:

Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. Textbook of Diabetes Wiley.

238–249. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Masenga SK, Kabwe LS, Chakulya M and

Kirabo A: Mechanisms of oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Int

J Mol Sci. 24:78982023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Redza-Dutordoir M and Averill-Bates DA:

Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen

species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1863:2977–2992. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen H, Li J, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Li X, Tang

H, Liu Y, Li T, He H, Du B, et al: Bisphenol F suppresses

insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism in adipocytes by inhibiting

IRS-1/PI3K/AKT pathway. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 231:1132012022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhao SL, Liu D, Ding LQ, Liu GK, Yao T, Wu

LL, Li G, Cao SJ, Qiu F and Kang N: Schisandra chinensis lignans

improve insulin resistance by targeting TLR4 and activating

IRS-1/PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Int Immunopharmacol.

142:1130692024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Huang L, Guo Z, Huang M, Zeng X and Huang

H: Triiodothyronine (T3) promotes browning of white adipose through

inhibition of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Sci Rep.

14:203702024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Báez AM, Ayala G, Pedroza-Saavedra A,

González-Sánchez HM and Amparan LC: Phosphorylation codes in IRS-1

and IRS-2 are associated with the activation/inhibition of insulin

canonical signaling pathways. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 46:634–649.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Woo JR, Bae SH, Wales TE, Engen JR, Lee J,

Jang H and Park S: The serine phosphorylations in the IRS-1 PIR

domain abrogate IRS-1 and IR interaction. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA.

121:e24017161212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Lien EC, Lyssiotis CA and Cantley LC:

Metabolic reprogramming by the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway in cancer.

Metabolism in Cancer. 207:39–72. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Fontana F, Giannitti G, Marchesi S and

Limonta P: The PI3K/Akt pathway and glucose metabolism: A dangerous

liaison in cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 20:3113–3125. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Park J, Rho HK, Kim KH, Choe SS, Lee YS

and Kim JB: Overexpression of Glucose-6-Phosphate dehydrogenase is

associated with lipid dysregulation and insulin resistance in

obesity. Mol Cell Biol. 25:5146–5157. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Martínez-Reyes I and Chandel NS:

Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease.

Nat Commun. 11:1022020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Choi I, Son H and Baek JH: Tricarboxylic

Acid (TCA) cycle intermediates: Regulators of immune responses.

Life (Basel). 11:692021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Zhang X, Jia Y, Yuan Z, Wen Y, Zhang Y,

Ren J, Ji P, Yao W, Hua Y and Wei Y: Sheng Mai San ameliorated heat

stress-induced liver injury via regulating energy metabolism and

AMPK/Drp1-dependent autophagy process. Phytomedicine.

97:1539202022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Tian JL, Si X, Shu C, Wang YH, Tan H, Zang

ZH, Zhang WJ, Xie X, Chen Y and Li B: Synergistic effects of

combined anthocyanin and metformin treatment for hyperglycemia in

vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 70:1182–1195. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Namvarjah F, Shokri-Afra H,

Moradi-Sardareh H, Khorzoughi RB, Pasalar P, Panahi G and Meshkani

R: Chlorogenic acid improves anti-lipogenic activity of metformin

by positive regulating of AMPK signaling in HepG2 cells. Cell

Biochem Biophys. 80:537–545. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sun L, Jiang J, Zeng Y, Zhu J, Wang S,

Huang D and Cao C: Polysaccharide NAP-3 synergistically enhances

the efficiency of metformin in type 2 diabetes via Bile Acid/GLP-1

axis through gut microbiota remodeling. J Agric Food Chem.

72:21077–21088. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Long J, Li M, Yao C, Ma W, Liu H and Yan

D: Structural characterization of Astragalus polysaccharide-D1 and

its improvement of low-dose metformin effect by enriching

Staphylococcus lentus. Int J Biol Macromol. 272:1328602024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Toubal A, Kiaf B, Beaudoin L, Cagninacci

L, Rhimi M, Fruchet B, da Silva J, Corbett AJ, Simoni Y, Lantz O,

et al: Mucosal-associated invariant T cells promote inflammation

and intestinal dysbiosis leading to metabolic dysfunction during

obesity. Nat Commun. 11:37552020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Khan S, Luck H, Winer S and Winer DA:

Emerging concepts in intestinal immune control of obesity-related

metabolic disease. Nat Commun. 12:25982021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Riedel S, Pheiffer C, Johnson R, Louw J

and Muller CJF: Intestinal barrier function and immune homeostasis

are missing links in obesity and type 2 diabetes development. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12:8335442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wang YX, Chen XL, Zhou K, Wang LL, Zhong

YZ, Peng J, Ge BS, Ho CT and Lu CY: Fucoidan dose-dependently

alleviated hyperuricemia and modulated gut microbiota in mice. Food

& Medicine Homology. 3:94200952025.