Introduction

Cell adhesion molecules fulfill critical roles in

embryonic development, tissue repair and intercellular

communication (1,2). In cancer, dynamic regulation of

adhesion and detachment underlies tumor invasion and metastasis

(3). The progression and

metastasis of cancer are coordinated by intricate molecular

mechanisms that transcend mere tumor cell proliferation,

encompassing dynamic interactions with the surrounding tumor

microenvironment. Among these mechanisms, cell adhesion molecules

(CAMs) have emerged as pivotal regulators of malignant behaviors,

including cancer cell adhesion, migration and invasion and also

interaction with the vascular endothelium, thereby facilitating

metastatic dissemination and the acquisition of aggressive

phenotypes (4,5). Major CAM families, including

cadherins, integrins, selectins and members of the immunoglobulin

superfamily, contribute to tumor progression through distinct, yet

often interrelated, signaling pathways. For example, the loss of

E-cadherin expression is a well-established trigger of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition, promoting the enhanced motility,

invasiveness and metastatic potential of cancer cells (6). Integrins, which mediate

cell-extracellular matrix interactions, exert critical roles in

cellular migration and angiogenesis. Alterations in the expression

of specific integrin subunits have previously been associated with

unfavorable clinical outcomes in various malignancies (7). Moreover, accumulating evidence has

shown that CAMs function not only as structural mediators, but also

as active transducers of intracellular signaling cascades that

regulate tumor cell survival, therapeutic resistance and immune

evasion (8). In particular,

studies have highlighted that alterations in the expression and

function of CAMs are closely associated with the progression of

gastric cancer (9–14). Dysregulated CAM expression, such as

reduced E-cadherin or aberrant integrin profiles, has been linked

to enhanced tumor invasiveness, lymph node metastasis and poor

clinical prognosis in patients with gastric carcinoma (2,3,6–8,11).

These findings suggest that CAMs play a critical role not only in

early tumor development but also in the acquisition of metastatic

traits in gastric cancer. The present study focused on a specific

CAM, gicerin, that has been implicated in gastric cancer

progression. Through an analysis of its expression profile and

functional roles, the aim of this study was to elucidate its

potential as a novel therapeutic target in gastric cancer

treatment.

Gicerin, originally identified from chicken gizzard

smooth muscle, shares high homology with mammalian CD146/MelCAM

(15–19). As described in more detail below,

it has five immunoglobulin-like domains in its extracellular region

and two major isoforms [long (L)-gicerin and short (S)-gicerin)]

have been shown to be generated by alternative splicing (19–22).

Gicerin is a single-pass transmembrane glycoprotein localized to

the cell membrane and comprises a large extracellular domain, a

single transmembrane segment and a short cytoplasmic domain. The

extracellular region contains five immunoglobulin-like loop

structures, two of the V-set type and three of the C2-set type, as

well as several potential N-linked glycosylation sites. The

cytoplasmic domain is predicted to contain four serine/threonine

phosphorylation sites, suggesting that gicerin may be involved in

cell adhesion and intracellular signal transduction.

Gicerin has been shown to engage in both homophilic

and heterophilic interactions, including those with specific

laminins, influencing processes such as cell migration and neurite

extension (19,20). Although it is widely expressed

during embryogenesis, gicerin is limited in normal adult tissues to

sites such as vascular endothelium and muscle (19,20).

However, re-expression of gicerin in malignant tumors has been

shown to be associated with enhanced invasiveness and metastatic

potential (15,19,20).

Gastric cancer is a common gastrointestinal

malignancy, frequently metastasizing to the liver and peritoneum,

with occasional, but significant, pulmonary metastases (23–25).

Studies have indicated that various cell adhesion molecules are

critical regulators of metastasis in gastric cancer, highlighting

them as potential therapeutic targets (9–14,26,27).

Cell adhesion molecules, such as E-cadherin, claudin, contactin 1,

mucin 1 and L1 cell adhesion molecule, are known to facilitate or

inhibit tumor progression and gicerin is likely to have a

comparable role in gastric cancer.

NUGC-4, a poorly differentiated gastric

adenocarcinoma cell line, is commonly used for in vivo

modeling of tumor growth and metastasis (28). In the present study, it was shown

that NUGC-4 cells expressed gicerin and the study also evaluated

how anti-gicerin antibodies affect their subcutaneous

tumorigenicity and lung metastatic potential in nude mice.

Materials and methods

Immunization and purification of

anti-gicerin antibodies

To generate polyclonal antibodies against gicerin,

10 female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were immunized with

recombinant gicerin protein. The primary immunization was performed

subcutaneously with 50 µg of recombinant rat gicerin protein (aa

1–545; accession number Q9EPF2-1) (29), which exhibits ~70% peptide-sequence

homology to the human gicerin ortholog, emulsified in an equal

volume of Complete Freund's Adjuvant (MilliporeSigma). Booster

injections were administered on days 14 and 28 using an identical

dose of antigen emulsified in Incomplete Freund's Adjuvant

(MilliporeSigma). On day 42, mice were deeply anesthetized using

isoflurane (induction at 3–5% and maintenance at 2–3% in oxygen)

and the absence of reflex responses (pedal withdrawal and palpebral

reflexes) was confirmed before proceeding. For terminal blood

collection, cardiac puncture was performed under deep anesthesia

using a 1 ml syringe with a 23-gauge needle. Blood (~0.5–1.0 ml)

was withdrawn from the left ventricle. Following the procedure,

sacrifice of the mice was performed by cervical dislocation while

under deep anesthesia, or alternatively by thoracotomy to confirm

the cessation of cardiac activity. Finally, mortality was verified

by the absence of a heartbeat and fixed, dilated pupils. All animal

procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional

guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee

of Kyoto Prefecture University (approval no. KPU240401). A total of

55 mice, including those reserved as backups, were used for

antibody production and tumor cell transplantation in the present

study.

Collected blood samples were allowed to clot at room

temperature for 1 h prior to centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min

at 4°C to isolate serum. The sera from all mice were pooled and

total IgG was purified using a Protein G Sepharose column (GE

Healthcare) following the manufacturer's protocol. Bound IgG was

eluted with 0.1 M glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.7) and immediately

neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 9.0). The eluates were

subsequently dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH

7.4) and the IgG concentrations were determined

spectrophotometrically. Similarly, serum was collected from

non-immunized normal mice and IgG was purified using protein G

affinity chromatography. The resulting antibodies were used as

pre-immune IgG.

For the isolation of gicerin-specific antibodies,

affinity purification was performed using a custom-made column

prepared by covalently coupling recombinant gicerin protein to

CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads (Cytiva). The purified IgG was

subsequently loaded onto the affinity column equilibrated with PBS.

After extensive washing, bound antibodies were eluted with 0.1 M

glycine-HCl buffer (pH 2.7) and immediately neutralized, as

aforementioned. The eluted antibodies were then dialyzed against

PBS and protein concentrations were quantified using a BCA Protein

Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The final purified

anti-gicerin antibodies were subsequently adjusted to a

concentration of 1 mg/ml in PBS and stored at −80°C until use. The

overview of antibody production and purification is shown in

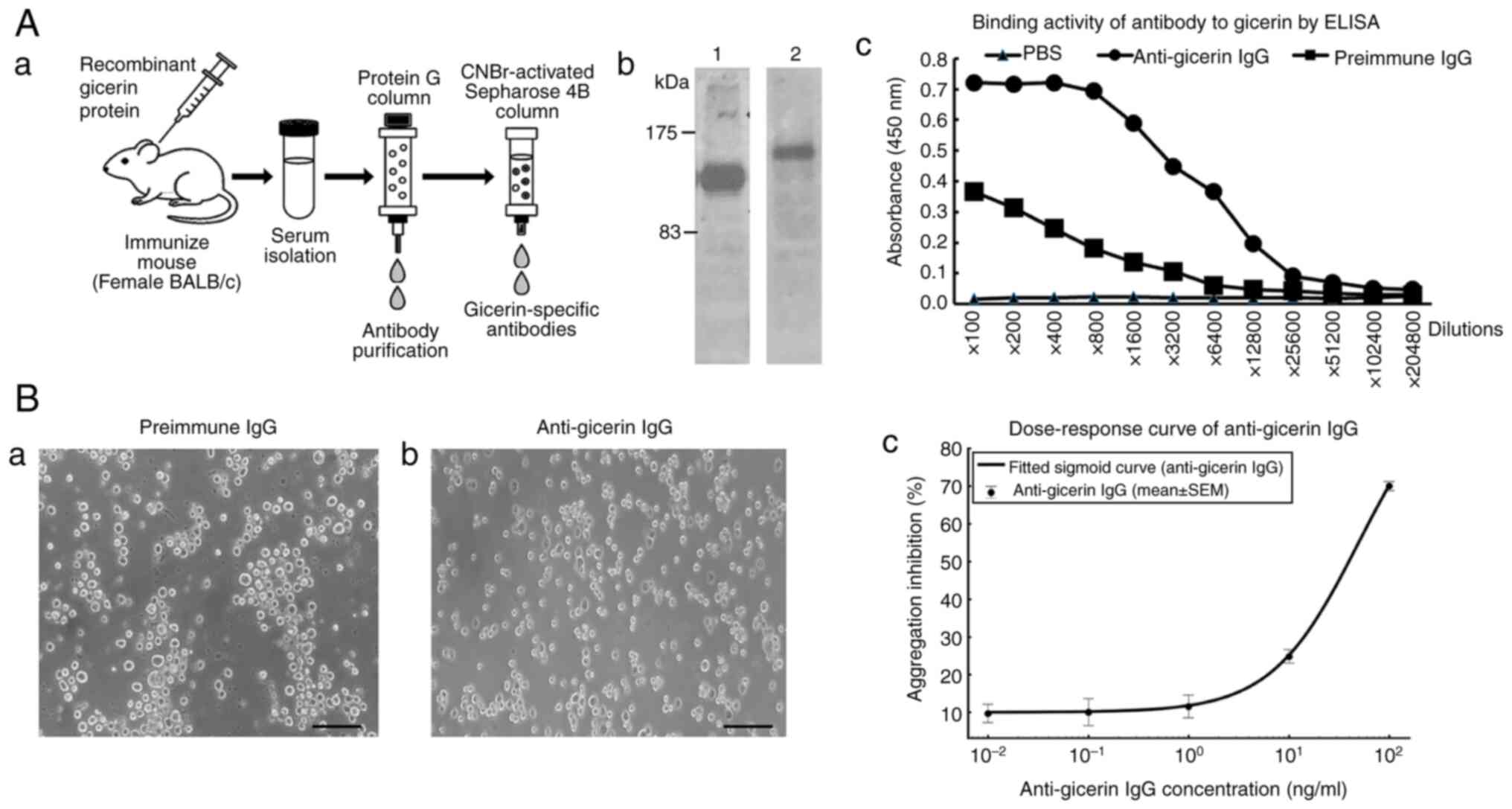

Fig. 1A.

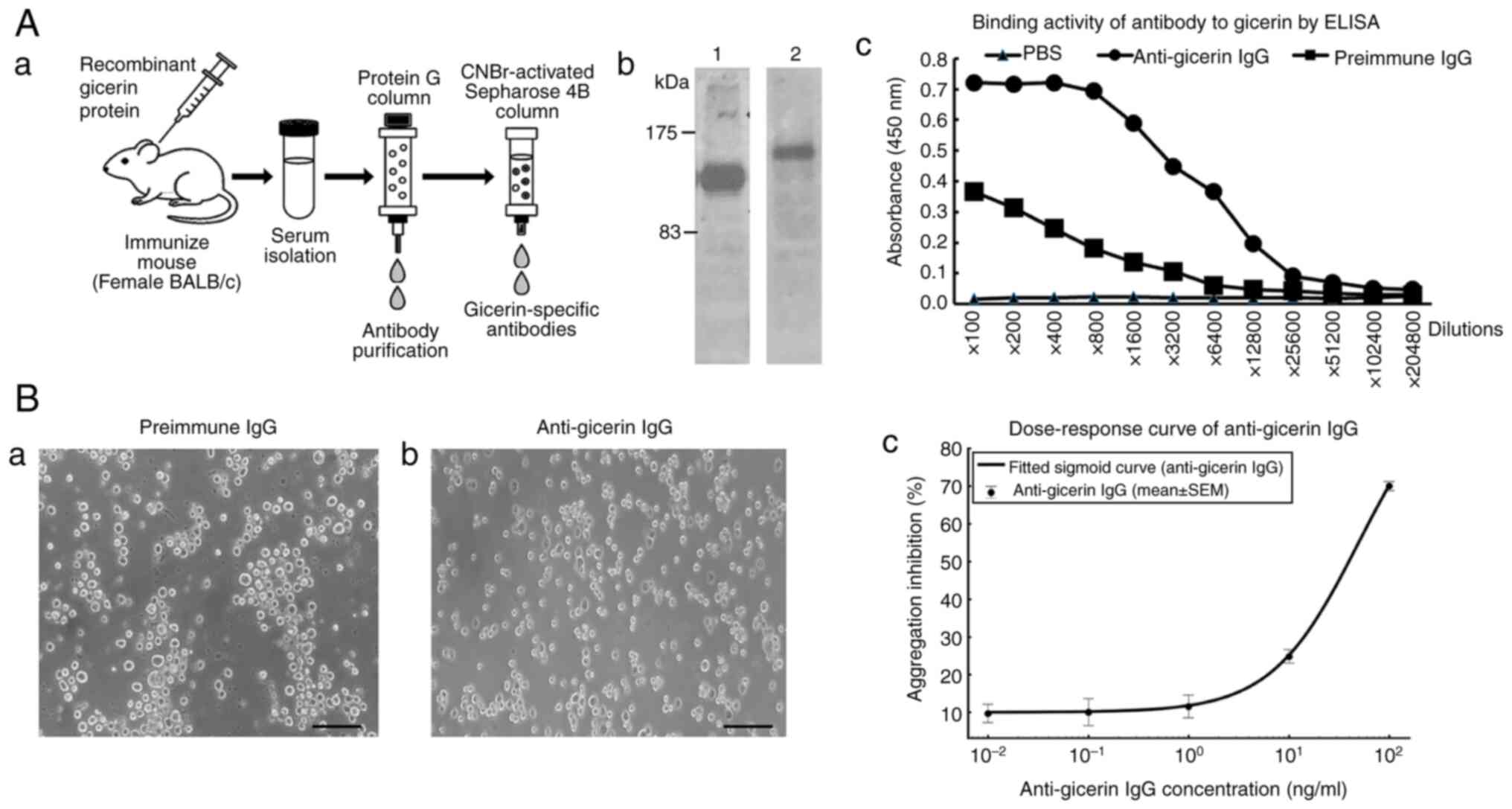

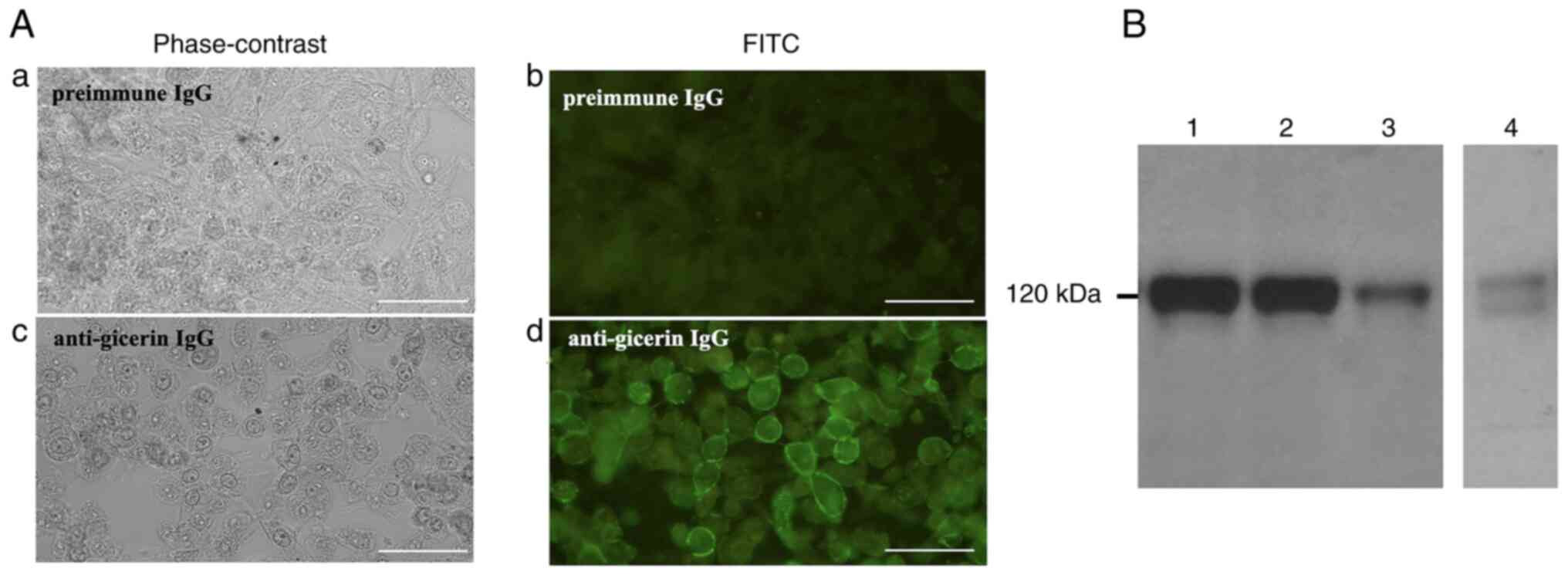

| Figure 1.Generation of mouse anti-gicerin

antibody and validation of its binding activity. (A) The procedure

for generating and purifying the murine anti-gicerin antibody is

summarized. (a) BALB/c mice were immunized with recombinant gicerin

protein, followed by IgG purification from serum. The IgG fraction

was subsequently affinity-purified using a Sepharose column

conjugated with gicerin protein. (b) As shown by SDS-PAGE, the

gicerin recombinant protein immunized as the antigen for antibody

production (lane 1) appeared as a single band at ~120 kDa, while

the final purified mouse IgG (lane 2) exhibited a single band at

~150 kDa. Binding activity of mouse IgG to gicerin proteins by

ELISA. (c) Recombinant proteins of gicerin were bound to plate at 2

µg/ml overnight at 4°C. Samples were blocked with 1% blocking

buffer (Block Ace) in distilled water for 2 h. Serial dilutions of

pre-immune or anti-gicerin IgG were incubated at room temperature

for 2 h. After washing with PBS, HRP-conjugated polyclonal antibody

against mouse IgGs were reacted for 1 h at room temperature. Then,

3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine was added to each well and plates

were read at 450 nm utilizing a Multiscan JX (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). ELISA demonstrated that the purified antibody

exhibited strong binding activity to gicerin protein, with an ELISA

titer of 12,800 when compared to pre-immune IgG. (B) Neutralizing

activity of anti-gicerin IgG in cell adhesion. (a) In the cell

aggregation assay, L-929 cells expressing gicerin formed

multicellular aggregates upon the addition of pre-immune IgG,

indicating cell-cell adhesion. (b) When the anti-gicerin IgG was

added to the suspension cultures, a marked inhibition of cell-cell

aggregation was observed. Scale bars, 100 µm; magnification, ×200.

(c) Dose-response curves were generated by plotting the aggregation

index against the logarithmic antibody concentrations. Nonlinear

regression analysis determined that the IC50 of

anti-gicerin IgG was 49.5 ng/ml, indicating its potent neutralizing

effect on cell adhesion. IC50, half-maximal inhibitory

concentration. |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide

gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB)

Staining

Recombinant gicerin protein and mouse antibodies

were separated by SDS-PAGE on 8% gels. Protein samples were mixed

with Laemmli sample buffer, heated at 95°C for 5 min and loaded

onto an 8% polyacrylamide gel. Electrophoresis was carried out

under reducing conditions using a Mini-PROTEAN Tetra System

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) at a constant voltage of 100 V. After

electrophoresis, the gel was briefly rinsed with distilled water

and stained using Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 staining solution

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. The gel

was subsequently destained with a solution containing 40% methanol

and 10% acetic acid until protein bands became clearly visible.

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

Each well of the polystyrene ELISA plates (Sumitomo

Bakelite Co., Ltd.) was coated with 0.2 µg of recombinant gicerin

proteins in PBS and the plate was incubated over night at 4°C. Each

of the following incubation steps were preceded by washing the

wells twice with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. The wells were

blocked for nonspecific binding by the addition of a commercial

blocking buffer (DS Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd.) and were incubated

at 37°C for 2 h. The serial dilutions of pre-immune IgG and

anti-gicerin IgG were added vertically to the wells and kept for

incubation at 37°C for 1 h. The HRP-conjugated rabbit IgG diluted

(1:5,000) in PBS was dispensed into each well. The plate was

incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Later, a substrate buffer containing TMB

(Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd.) was added to each well and kept for

incubation at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was terminated by the

addition of a stopping reagent (1.25M sulfuric acid). The

absorbance was recorded at 450 nm using the ELISA plate reader (DS

Pharma Biomedical Co., Ltd.). The ELISA titer was defined as the

highest dilution factor of anti-gicerin IgG that yielded an

absorbance value at least three times higher than that obtained

with pre-immune IgG.

Neutralization activity of

anti-gicerin IgG on cell-cell interactions

Reaggregation assay and determination of

IC50 for anti-gicerin antibody: A reaggregation assay

was performed to evaluate the inhibitory effect of anti-gicerin

mouse IgG on cell-cell adhesion in gicerin transfected L929 cells

(RIKEN BioResource Research Center; cat. no. RCB2619) (30). The cells were cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; high glucose) supplemented

with L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and

antibiotics (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) and maintained at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Then, the cells

were detached using 0.02% EDTA in calcium- and magnesium-free PBS

to obtain a single-cell suspension. The cells were then washed

twice with calcium- and magnesium-containing Hank's Balanced Salt

Solution (HBSS) and resuspended at a concentration of

1×106 cells/ml. Serial dilutions of purified

anti-gicerin mouse IgG (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 ng/ml) or

control non-immune mouse IgG were prepared in HBSS. Equal volumes

of antibody solution and cell suspension were mixed and transferred

to 96-well U-bottom low-adhesion plates (100 µl/well). The mixtures

were incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow antibody binding.

Subsequently, the plate was gently agitated on an orbital shaker

(50 rpm) and incubated for an additional 45 min at 37°C to promote

cell-cell reaggregation. Following incubation, the degree of cell

aggregation in each well was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy.

A cell aggregate composed of at least four cells was counted as a

single unit for analysis (21).

Images of representative fields (five per well) were captured at

×200 magnification. Aggregation was quantified by calculating the

inhibition of cell aggregation (%), defined as follows: Inhibition

of cell aggregation (%)=100 × (1-number of single cells/total

number of cells).

Cell line and culture conditions

NUGC-4 cells (JCRB Cell Bank; cat no. JCRB0834),

HUVEC cells [JCRB Cell Bank; cat. no. IFO50271; F10 (passage 10)]

and murine melanoma B16 cells (RIKEN BioResource Research Center;

cat. no. RCB1283) were cultured in DMEM (high glucose) supplemented

with L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate, 10% FBS and antibiotics (Nacalai

Tesque, Inc.) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere

containing 5% CO2.

Confirmation of gicerin expression on

NUGC-4 cells and HUVECs

Monolayers of NUGC-4 and HUVEC cells were fixed

using Zamboni's fixative and incubated with a murine polyclonal

anti-gicerin antibody (1:500; generated as aforementioned) at 37°C,

followed by an FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100;

MilliporeSigma; cat. no. AP124F) at 37°C. In addition, tumor

tissues harvested from mice were fixed in Zamboni's solution and

frozen sections (20 µm thickness) were subjected to

immunofluorescence staining using the anti-gicerin primary antibody

followed by the FITC-conjugated secondary antibody as

aforementioned. Fluorescence microscopy revealed the distinct

membrane-localized expression of gicerin on cells. A commercially

available mounting medium containing DAPI was employed following

the manufacturer's instructions. While nuclear staining was

achieved, the combined display of phase-contrast, FITC (gicerin)

and DAPI slightly reduced the clarity of cell contours in our

setup; therefore, the final images are presented without DAPI to

best illustrate the relationship between cell morphology and

gicerin expression in the same field of view.

Protein extraction and western blot

analysis

Cultured NUGC-4, HUVEC and B16 cells were rinsed

twice with calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks' balanced salt

solution and collected using a cell scraper. The harvested

monolayer cells were subsequently homogenized in PBS using a

Polytron homogenizer. The homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g

for 10 min at 4°C to remove cellular debris, followed by

centrifugation of the supernatants at 18,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C.

The resulting pellets were resuspended in 10 mM Tris-acetate buffer

(pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and incubated

at 4°C for 1 h with continuous rotation. The suspensions were

subsequently centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C and the

final supernatants were collected for western blot analysis, as

described by Taniura et al (31). Protein concentrations were

quantified using BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) at an absorbance of 562 nm, with bovine serum

albumin as a standard. Equal amounts of total protein (20 µg)

extracted from HUVEC, NUGC-4 and B16 cells, along with 10 ng

recombinant gicerin protein and mouse IgG, were separated by

SDS-PAGE using 7.5% polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred on

to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). The membranes were blocked with Bullet

Blocking One reagent (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.; cat. no. 1379) and

subsequently incubated for 1 h at room temperature with primary

anti-gicerin antibodies which were generated as aforementioned)

diluted 1:1,000 in 2% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)

buffer (150 mM NaCl/10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). After six washes with

TBST buffer (TBS buffer containing 0.05% Tween-20), the membranes

were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.;

cat. no. 21860-61l) diluted 1:1,000 in TBS buffer containing 2%

skimmed milk. Following four washes with TBST and two final washes

with TBS, immunoreactive bands were visualized using 0.05%

diaminobenzidine (MilliporeSigma) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6)

containing 0.03% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min at room temperature.

The reaction was stopped by rinsing in distilled water. Images of

the membranes were captured using a ChemiDoc imaging system

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) as previously described (19,20).

Subcutaneous tumor transplantation

model

Subcutaneous implantation of tumor cells into the

cervical region of nude mice offers several advantages (32). The cervical area provides a soft

and accessible site that facilitates precise and reproducible

injection of the cell suspension, minimizing procedural

variability. Tumors formed in this region tend to grow outward

beneath the skin, allowing for easy visual assessment and accurate

measurement of tumor size using calipers. Additionally, the

relatively stable blood supply in the cervical skin reduces the

risk of ulceration, thereby enabling long-term observation and

reliable evaluation of therapeutic efficacy. Since the tumor

remains localized in the cervical area, vital organs such as those

of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems are less likely to be

affected, contributing to the maintenance of the general condition

of the animals and allowing for consistent assessment of drug

effects and toxicity. Moreover, because cervical tumors rarely

interfere with the mobility or feeding behavior of the animals,

this model supports the ethical conduct of experiments while

minimizing distress to the animals. After harvesting the NUGC-4

cells with trypsin-EDTA (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), the cells were

split into two groups. One group was incubated with anti-gicerin

IgG (10 µg/ml), whereas the other was incubated with pre-immune IgG

(10 µg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and resuspended in

serum-free DMEM (3×107 cells/ml) and 0.2 ml cell

suspension was injected subcutaneously into the dorsal cervical

region of nude mice (9-week-old female BALB/c Slc-nu/nu mice; n=5

per group). Tumor volume was calculated every other day starting at

1-week post-inoculation using the formula (AxB2)/2,

where A and B represent the largest and smallest tumor diameters,

respectively.

After the final measurement, mice were deeply

anesthetized using isoflurane (induction at 3–5% and maintenance at

2–3% in oxygen) and the absence of reflex responses (pedal

withdrawal and palpebral reflexes) was confirmed before proceeding

with the experiment. Sacrifice was performed by cervical

dislocation while the mice were in a state of deep anesthesia, or

alternatively by thoracotomy to confirm the cessation of cardiac

activity. Mortality was verified by the absence of a heartbeat and

fixed, dilated pupils. In accordance with institutional animal care

guidelines, the maximum allowable tumor volume was limited to 1.5

cm3. Mice were sacrificed immediately upon reaching this

limit or upon exhibiting signs of pain, ulceration or impaired

mobility; however, no animals exhibited such conditions during the

course of the experiment.

Pathologically, the tumors were excised, 10%

buffered-formalin-fixed for 48 h at room temperature,

paraffin-embedded and stained with hematoxylin for 5 min at room

temperature (22–25°C), followed by eosin staining for 3 min at room

temperature [hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining] for a

histopathological assessment of local invasion. For

immunofluorescence staining, tumor tissues were fixed in Zamboni's

fixative, followed by cryoprotection in 20% sucrose solution for 24

h at 4°C. The samples were subsequently frozen at −30°C and 20-µm

frozen sections were prepared using a cryostat. The frozen sections

were blocked with 1% non-fat dry milk in PBS containing 0.1%

Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature, and were subsequently

incubated with a murine polyclonal anti-gicerin antibody (1:500;

generated as aforementioned) at 37°C, followed by an

FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100; MilliporeSigma; cat.

no. AP124F) at 37°C as aforementioned. Fluorescence microscopy

revealed the distinct membrane-localized expression of gicerin on

cells.

Hematogenous pulmonary metastasis

model

NUGC-4 cells (2.5×106 cells/ml) were

pretreated with anti-gicerin antibodies or pre-immune IgG under the

same conditions. Each mouse (n=5 per group) received a 0.1 ml

tail-vein injection of either of the treated cell suspensions.

After 1 week, mice were sacrificed and lungs were collected,

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded and stained with H&E, as

aforementioned. The number of metastatic foci was counted in all

lung lobes and expressed as nodules per cm2. In these

experiments, mice were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane

(induction at 3–5% and maintenance at 2–3% in oxygen) and the

absence of reflex responses (pedal withdrawal and palpebral

reflexes) was confirmed prior to the performance of any procedure.

Sacrifice was performed as aforementioned and mortality was

verified by the absence of a heartbeat and the presence of fixed,

dilated pupils. In cases where mice exhibited clinical signs such

as respiratory distress or lethargy, sacrifice was to have been

performed immediately to minimize suffering; however, no animals

exhibited such symptoms during the course of the experiment.

In vitro cell adhesion of NUGC-4 cells to gicerin

proteins: Cell adhesion experiments were carried out as

reported previously (21).

Aliquots (1 ml) of PBS containing 10ng/ml of recombinant gicerin

proteins were spotted on a 35 mm culture dish and incubated for 1 h

in a humidified 5% CO2 in incubator at 37°C. Then the

dishes were washed with DMEM three times and preincubated with DMEM

containing 10% FBS for 1 h to block nonspecific binding. Aliquots

(2 ml) of the cell suspension (1×106 cells/ml) were

plated on the test dishes. To assess the inhibition of adhesion

activity by anti-gicerin antibody, the cells were preincubated for

30 min at 37°C with the pre-immune IgG or anti-gicerin IgG at a

final concentration of 100 ng/ml before plating on the dishes. The

test dishes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, washed twice with DMEM

and the adhesion cells were observed by phase-contrast

microscopy.

In vitro cell adhesion of NUGC-4 cells

to vascular endothelial cells

Endogenous gicerin-positive HUVEC cells, a vascular

endothelial cell line, were cultured on dishes with DMEM containing

10% FBS at 37°C and used as feeder layers. The NUGC-4 cell

suspensions were preincubated with anti-gicerin polyclonal

antibodies or pre-immune IgG for 1 h at 37°C. After five washing in

PBS and centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the NUGC-4

cells were resuspended in DMEM and seeded on to the HUVEC

monolayers. Following a 30 min incubation at 37°C, the cultures

were gently washed with DMEM and removed and the NUGC-4 cells

adhering to the feeder layers were observed under a light

microscope (Nikon Corporation). The cell number per area was

determined for five areas and the average scores and standard

deviation (SD) were calculated.

Measurement of doubling time of NUGC-4

cells with antibodies

NUGC-4 cells were seeded into 6-well tissue culture

plates at a density of 2×104 cells per well in complete

DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The cells were incubated at 37°C in

a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 4 h to

allow for cell attachment, 10 µl of phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS), 10 µl of pre-immune IgG, or 10 µl (10 ng/ml) of anti-gicerin

IgG (10 ng/ml) was added to each well, respectively. For each

treatment group, a total of four independent plates (n=4) were

prepared and analyzed. At 0, 24, 48 and 72 h after seeding, one

well from each plate was harvested. Cells were gently washed with

PBS, detached using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA and resuspended in culture

medium. Cell viability was assessed using trypan blue exclusion and

viable cells were counted with a hemocytometer. Only unstained

(viable) cells were included in the count.

Doubling time (Td) was calculated using

the following formula:

where t is the elapsed time (in h),

N0 is the number of viable cells at time 0 and

Nt is the number of viable cells at time t. The mean

doubling time were calculated for each treatment group. Statistical

comparison was performed between the pre-immune IgG group and

anti-gicerin IgG using Student's t-test.

In vitro cell migration assay

NUGC-4 cells on culture dishes coated with gicerin

protein (as aforementioned) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with

10% FBS at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2 until they reached confluence. A straight scratch

was made across the center of each well using a sterile yellow

200-µl micropipette tip to detach cells along the line. The medium

was carefully aspirated to remove the detached cells and replaced

with fresh serum-free DMEM. The cells were then treated with either

pre-immune IgG (100 ng/ml) or anti-gicerin IgG (100 ng/ml) and

incubated under the same conditions. Cell migration into the

scratched area was monitored daily under a light microscope for up

to 96 h.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity

(CDC) assay

NUGC-4 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with

10% FBS and seeded into 24-well culture plates (Corning, Inc.).

Cells were subsequently incubated at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2 until they reached

semi-confluence. After removal of the culture medium, cells were

gently rinsed with PBS. Subsequently, serum-free DMEM containing

either pre-immune IgG or anti-gicerin polyclonal antibody was added

to each well. The final antibody concentration was adjusted to 10

µg/ml. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Following antibody

treatment, cells were washed gently two or three times with PBS to

remove any unbound antibodies. Fresh mouse serum

(complement-active) or heat-inactivated mouse serum (treated at

56°C for 30 min) was subsequently diluted in serum-free DMEM to a

final concentration of 20% and added to the cells. After a 1 h

incubation at 37°C, the supernatant containing non-adherent cells

was collected and temporarily maintained at 37°C, while the

adherent cells were detached using trypsin-EDTA. The cell

suspension and supernatant were mixed in the tubes and subsequently

centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min. The pellet was then resuspended

in either PBS or serum-free DMEM. Cell viability was subsequently

assessed using the trypan blue exclusion method. Equal volumes of

cell suspension and 0.4% trypan blue solution were mixed and the

mixture was loaded onto a hemocytometer. Viable (unstained) and

non-viable (blue-stained) cells were counted under a light

microscope and the cell death rate (as a percentage) was calculated

using the following formula: Cell death rate (%)=number of

blue-stained cells/total number of cells ×100. At least five

independent wells were analyzed per treatment group.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are presented as mean ±

standard deviation (SD). For in vivo experiments, n=5 mice

per group; for in vitro assays, at least n=4 independent

replicates per group unless otherwise indicated. Two-tailed,

unpaired Student's t-tests were used for single pairwise

comparisons and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by

Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used for

≥3-group comparisons. Exact P-values are reported on the graphs

and/or in the figure legends; where thresholds are shown,

significance is denoted as *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and *P<0.001;

‘ns’ indicates P≥0.05. Error bars on all graphs represent SD and

all ‘±’ values denote SD. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Generation and purification of murine

anti-gicerin antibody

The procedure for generating and purifying the

murine anti-gicerin antibody is summarized in Fig. 1A. BALB/c mice were immunized with

recombinant gicerin protein, followed by IgG purification from

serum. The IgG fraction was subsequently affinity-purified using a

Sepharose column conjugated with gicerin protein. SDS-PAGE analysis

revealed a single band at ~150 kDa in the final purified fraction,

indicating that a highly pure IgG preparation was obtained.

Furthermore, ELISA demonstrated that the purified antibody

exhibited strong binding activity to gicerin protein, with an ELISA

titer of 12,800 when compared to pre-immune IgG.

Neutralizing activity of anti-gicerin

IgG in cell adhesion

The neutralizing activity of anti-gicerin IgG was

evaluated using a cell aggregation assay. When anti-gicerin IgG was

added to the suspension culture of gicerin-expressing L929 cells, a

marked inhibition of cell-cell aggregation was observed (Fig. 1Ba and Bb). Dose-response curves

were generated by plotting the aggregation index against the

logarithmic antibody concentrations (Fig. 1Bc). Nonlinear regression analysis

determined that the half-maximal inhibitory concentration

(IC50) of anti-gicerin IgG was 49.5 ng/ml, indicating

its potent neutralizing effect on cell adhesion.

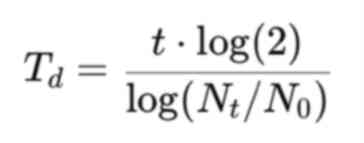

Gicerin is expressed in NUGC-4

cells

Immunofluorescence analysis revealed the presence of

distinct membrane-associated signals in NUGC-4 cells, confirming

robust gicerin expression (Fig.

2A). As a limitation of this study, it was unable to perform

co-localization staining with another inner membrane protein. This

was due to the poor adherence of NUGC-4 cells, which made them

susceptible to detachment during the multiple steps required for

double immunofluorescence staining, such as repeated washing,

antibody incubation and prolonged handling. Western blot analysis

demonstrated that gicerin was expressed in the membrane fractions

of B16 and HUVEC cells, both of which are known to endogenously

express gicerin, similarly to the recombinant protein. In addition,

gicerin expression was also detected in NUGC-4 cells (Fig. 2B). Notably, doublet bands were

observed at ~120 kDa, indicating that NUGC-4 cells express both the

S- and the L-isoforms of gicerin (19,20).

| Figure 2.Gicerin expression in NUGC-4 cells.

(A) Indirect immunofluorescence staining of NUGC-4 cells was

performed and observed under a fluorescence microscope (as shown by

the B-excitation filter). No fluorescence was detected when

pre-immune IgG was applied (a, phase contrast; b,

immunofluorescence). By contrast, strong green fluorescence was

observed on the cell surface following staining with anti-gicerin

IgG (c, phase contrast; d, immunofluorescence), indicating

membrane-associated expression of gicerin. scale bars, 50 µm;

magnification, ×400. (B) Western blot analysis of membrane

fractions from B16 (lane 2), HUVEC (lane 3) and NUGC-4 cells (lane

4) following SDS-PAGE. The recombinant gicerin protein used as the

immunogen was also subjected to electrophoresis as a positive

control and to verify the specificity and reactivity of the

antibody (lane 1). Notably, a doublet band of ~120 kDa was observed

in lane 4, consistent with the expression of both the short and

long isoforms of gicerin in NUGC-4 cells. |

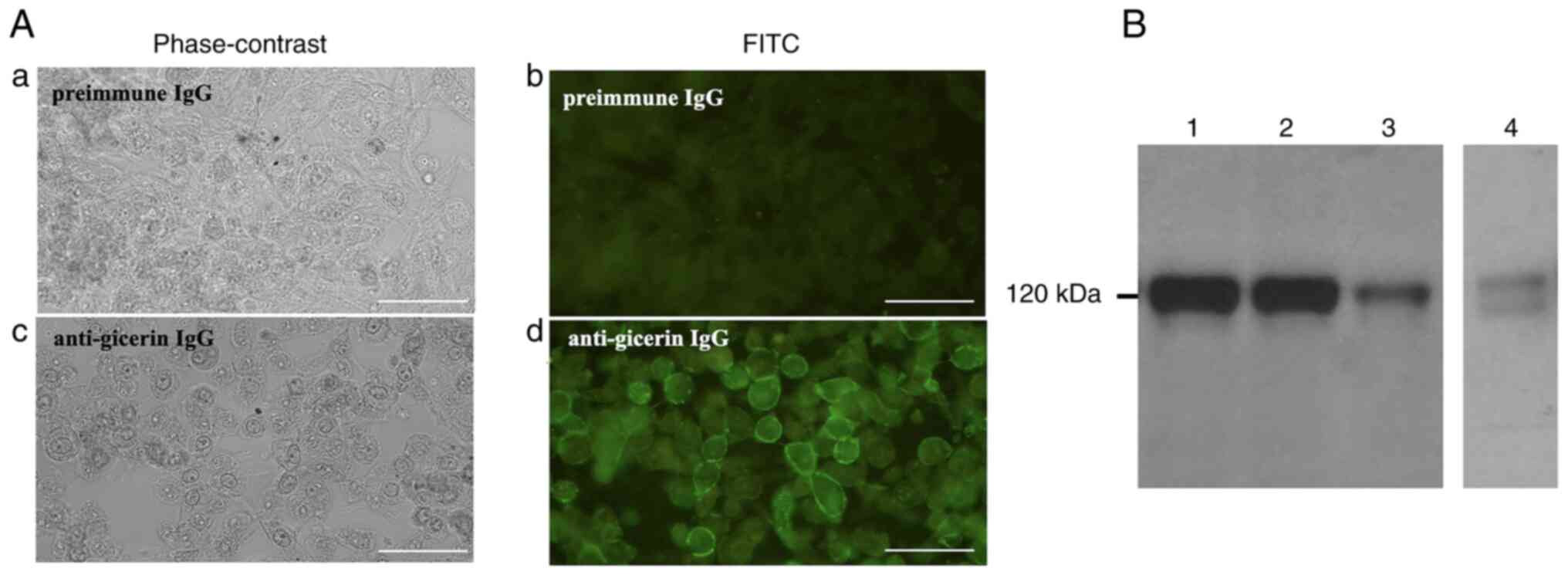

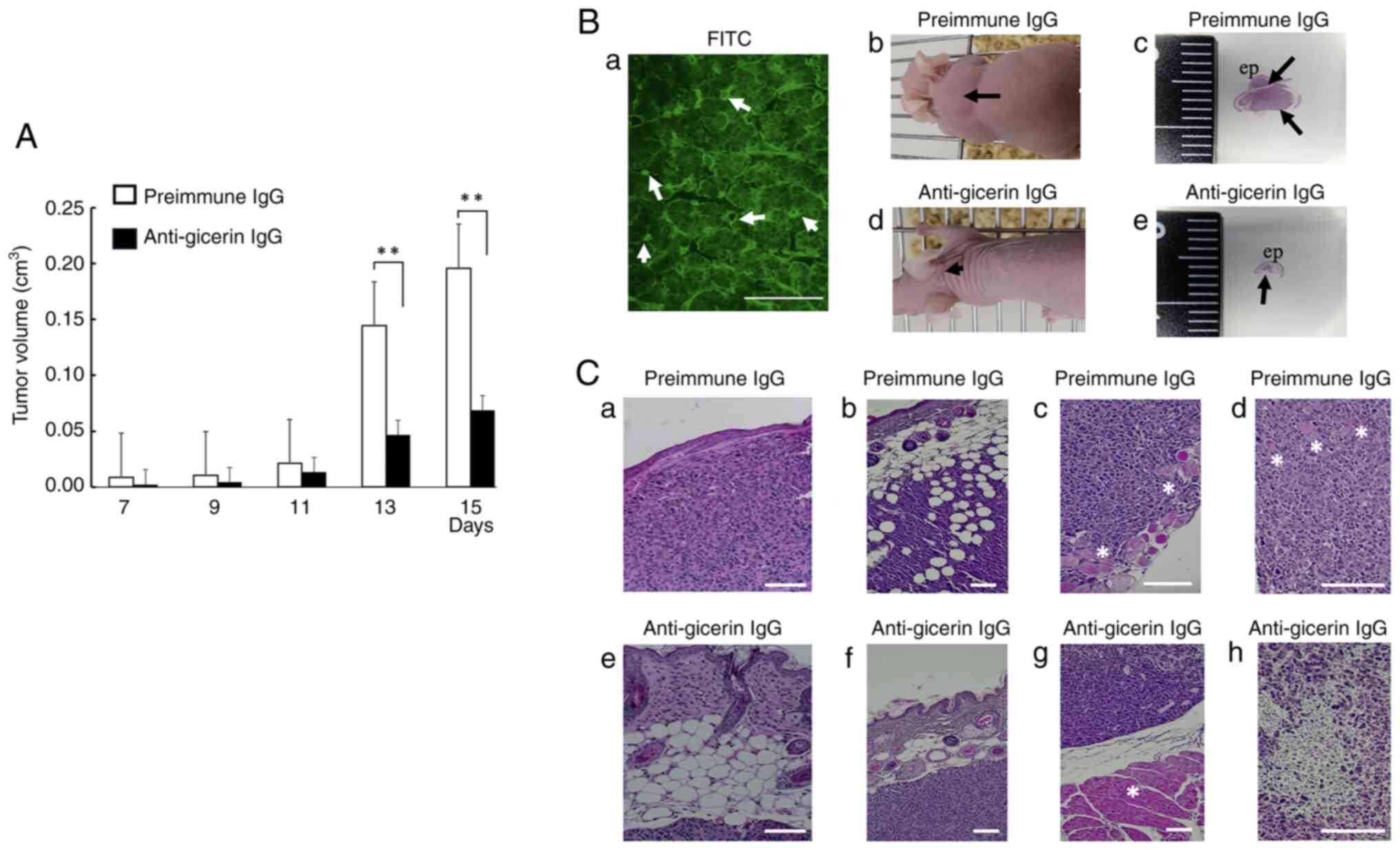

Subcutaneous tumor growth and invasion

is reduced in the subcutaneous tumor model

In the subcutaneous tumor model, tumor masses

derived from cells treated with anti-gicerin antibody exhibited

markedly suppressed tumor growth compared with the control group (P

<0.01; Fig. 3A).

Immunofluorescence analysis further revealed strong gicerin

expression on the membranes of tumor cells and in the endothelial

cells of newly formed blood vessels within tumors located in the

cervicodorsal region of the implanted mice (Fig. 3B). Moreover, histopathological

analysis revealed that tumors in the control group exhibited

extensive invasion into the dermis, muscle and adipose tissue. In

addition, epithelial-like arrangements of tumor cells were observed

in the control group, thereby revealing histological features

consistent with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. By contrast,

tumors in the anti-gicerin antibody-treated group were more

circumscribed and exhibited markedly reduced local invasiveness.

Furthermore, frequent and prominent focal necrotic lesions were

observed in tumors from animals administered the anti-gicerin

antibody. Within these tumors, cellular degeneration, structural

disintegration, pyknosis and karyorrhexis were also frequently

noted (Fig. 3C).

| Figure 3.Tumor growth and histopathological

features following subcutaneous injection into nude mice. (A)

NUGC-4 cells treated with either pre-immune IgG or anti-gicerin IgG

were subcutaneously injected into the dorsal neck region of nude

mice (n=5 per group). Tumor volume was measured over time using the

formula: AxB2/2, where A and B represent the maximum and

minimum tumor diameters, respectively. Data are mean ± SD (n=5 mice

per group). Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-tests were performed

between pre-immune IgG and anti-gicerin IgG at each time point.

Significance indicators: ns (P≥0.05), *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (B)

On day 15 post-injection, tumor tissues were examined both

histologically and using immunofluorescence analysis. (a) Gicerin

expression was detected in the tumor cell membranes, especially in

epithelial-like structures, as well as in neovascular structures

(denoted by the arrows) scale bars, 100 µm; magnification, ×200.

Compared with mice injected with pre-immune IgG (b and c), those

injected with anti-gicerin IgG displayed smaller tumor masses and

reduced tumor areas histologically with hematoxylin and eosin

staining (arrows) (d and e). (C) In the pre-immune IgG group,

histological evidence of tumor invasion into the dermis (a),

adipose tissue (b), subcutaneous muscle (c) and undifferentiated

adenocarcinoma (d) regions was noted (arrows indicate invasion into

the muscle). (e-g) By contrast, mice treated with anti-gicerin IgG

showed markedly reduced tumor invasiveness. (h) Furthermore, signs

of cellular degeneration, structural disintegration, pyknosis and

karyorrhexis were frequently observed within tumors treated with

anti-gicerin antibody. Scale bars, 100 µm; magnification: a and e:

×100; b, f and g: ×50; and c, d and h, ×200. |

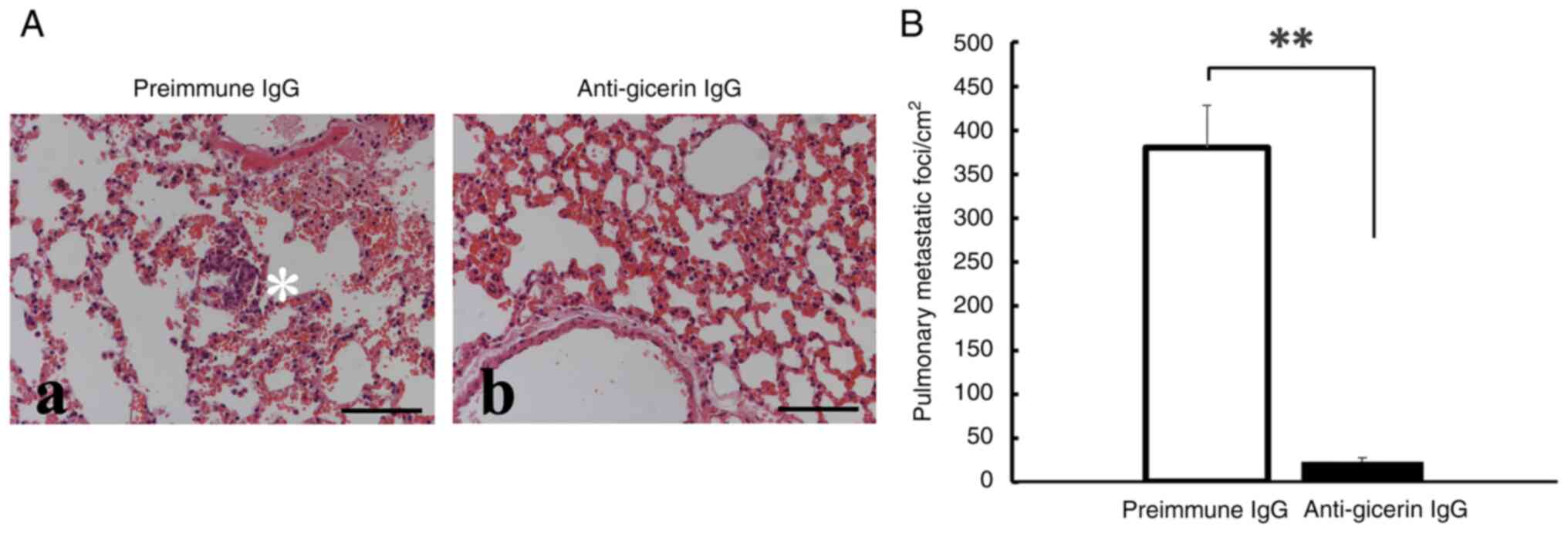

Pulmonary metastasis is suppressed in

the tail-vein injection model

In the tail-vein injection model, mice that received

pre-immune IgG-treated cells were found to develop multiple tumor

nodules in the lung parenchyma, often accompanied by hemorrhagic

changes (Fig. 4). By contrast,

mice injected with anti-gicerin antibody-treated cells exhibited

markedly fewer metastatic lesions, indicating substantial

inhibition of hematogenous spread.

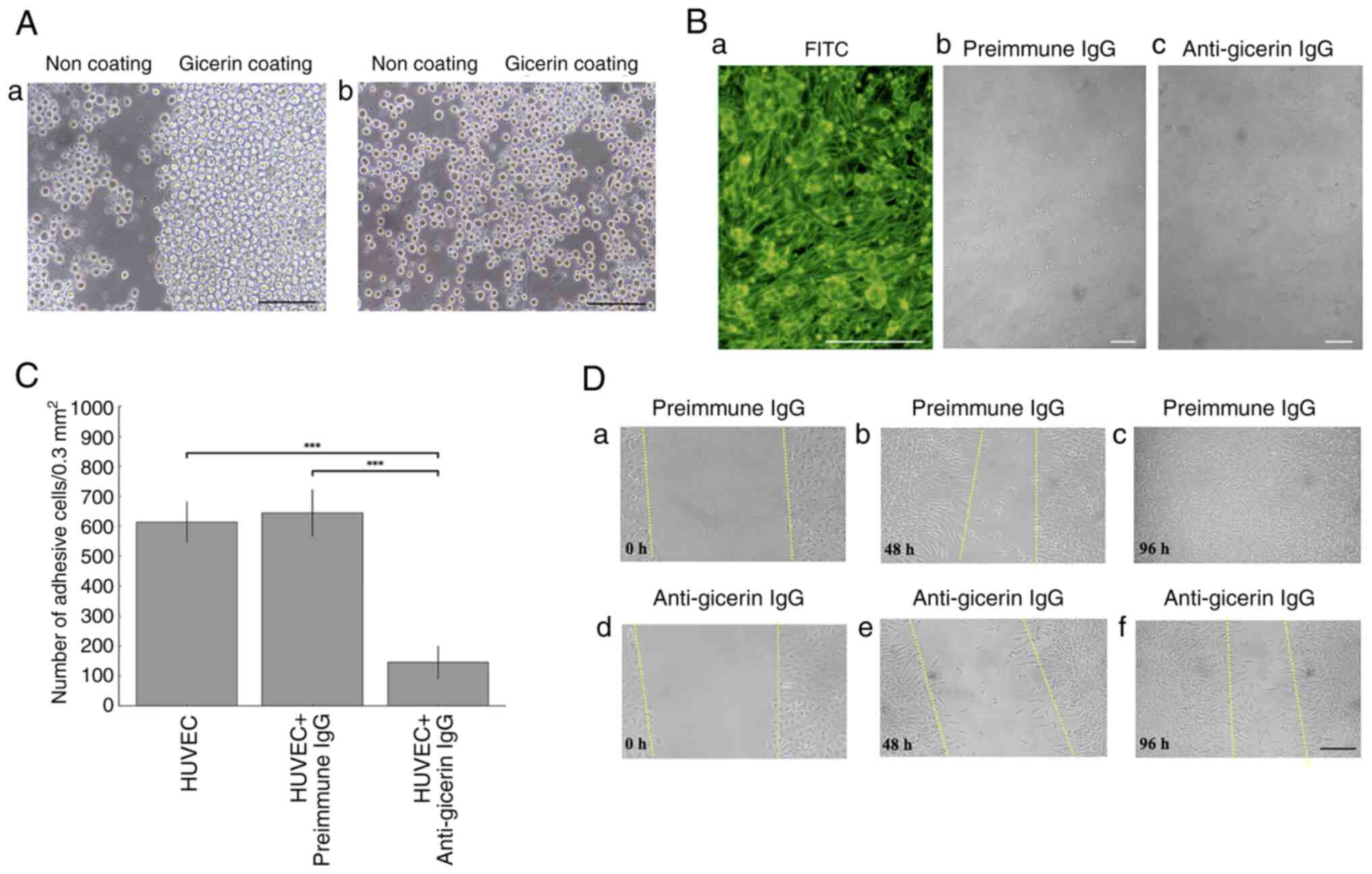

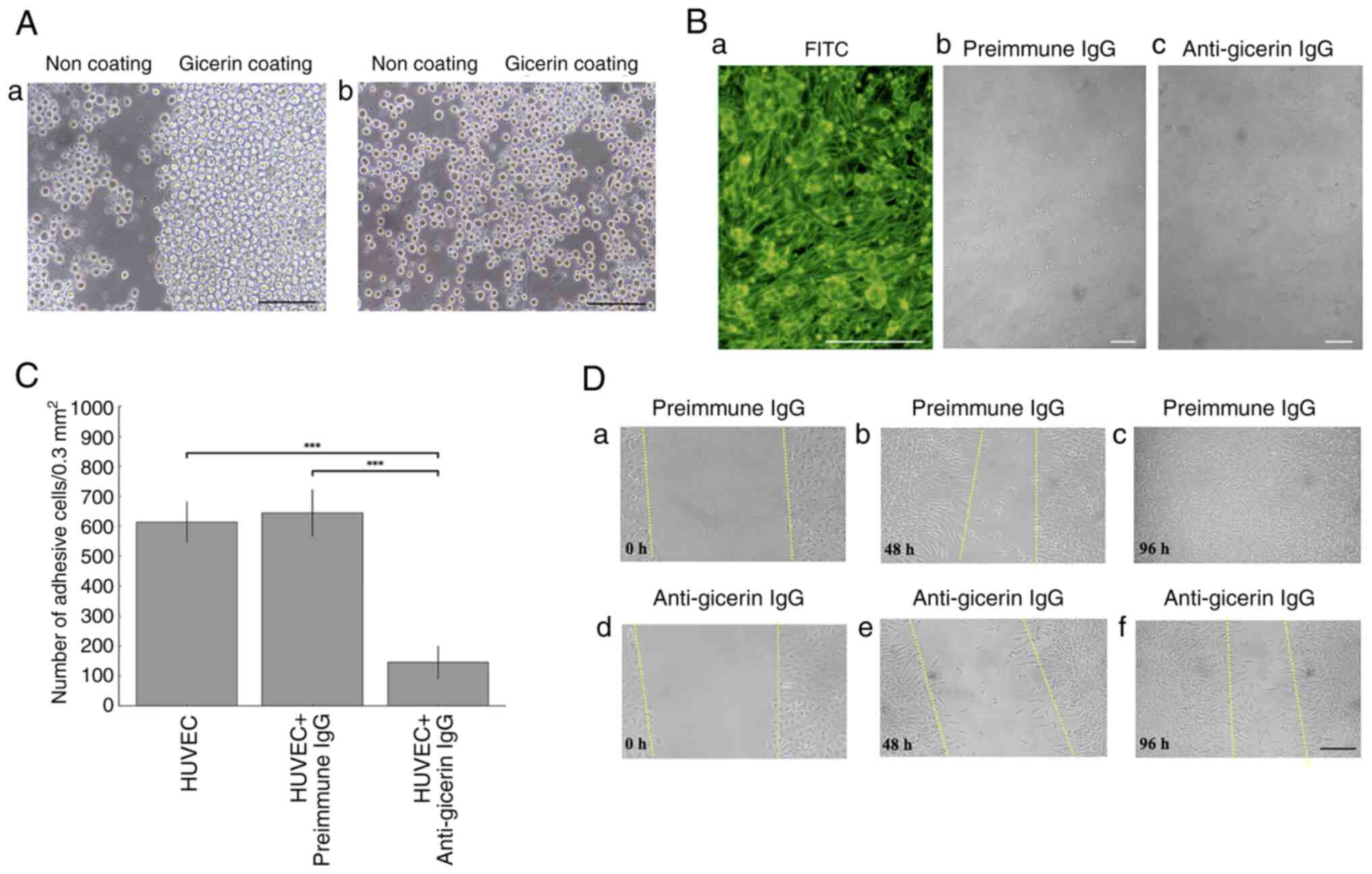

Inhibition of NUGC-4 cell adhesion to

gicerin-coated surfaces by anti-gicerin antibody

To evaluate the role of gicerin in mediating cell

adhesion, culture dishes were coated with recombinant gicerin

protein and seeded with NUGC-4 cells. A substantial number of cells

adhered to the gicerin-coated surface under control conditions.

However, in the presence of anti-gicerin antibody, cell adhesion to

the gicerin-coated areas was markedly inhibited, as evidenced by a

significant reduction in the number of adherent cells (Fig. 5A). These findings demonstrated that

the anti-gicerin antibody effectively neutralizes the homophilic

binding activity of gicerin, thereby suppressing gicerin-mediated

adhesion of NUGC-4 cells.

| Figure 5.(A) Inhibition of NUGC-4 cell

adhesion to gicerin protein by anti-gicerin antibody. Only the

right half of each culture dish was coated with recombinant gicerin

protein. NUGC-4 cell adhesion was assessed under a phase-contrast

microscope. (a) The cells predominantly adhered to the

gicerin-coated region, indicating that NUGC-4 cells exhibit

homophilic binding through gicerin molecules expressed on their

surface. Adhesion was not inhibited by pre-immune IgG. (b) By

contrast, treatment with anti-gicerin IgG markedly suppressed the

attachment of NUGC-4 cells to the gicerin-coated area. These

findings demonstrate that anti-gicerin IgG effectively blocks the

homophilic adhesion ability of NUGC-4 cells via gicerin. Scale

bars, 100 µm; magnification ×200. (B) Adhesion of NUGC-4 cells to

HUVEC monolayers. (a) Immunofluorescence staining revealed gicerin

expression on both adherent NUGC-4 cells and HUVEC feeder cells.

NUGC-4 cells treated with either (b) pre-immune IgG or (c)

anti-gicerin IgG were seeded on to confluent HUVEC monolayers.

Compared with the pre-immune IgG group, the number of NUGC-4 cells

attached to HUVEC layers was noticeably reduced in the anti-gicerin

IgG group. Scale bar, 100 µm. Magnification: a, ×200; and b and c,

×50. (C) The number of NUGC-4 cells adhering to HUVECs was markedly

lower in the anti-gicerin IgG group compared with the pre-immune

control. Adherent cells were counted in randomly selected 0.3

mm2 areas under light microscopy. Data are mean ± SD

(n=5 independent replicates per group). Group differences were

analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test across PBS,

pre-immune IgG and anti-gicerin IgG conditions. Anti-gicerin IgG

differed markedly from the other groups (***P<0.001), whereas

other pairwise comparisons were not significant unless indicated.

(D) Inhibition of NUGC-4 cell migration by anti-gicerin antibody.

NUGC-4 cells were seeded on culture dishes pre-coated with gicerin

protein and incubated until they reached confluence. (a) A linear

scratch was made across the cell monolayer using the tip of a

yellow pipette to create a cell-free area. (b) Culture media

containing either pre-immune IgG or anti-gicerin IgG was then added

and cell migration into the scratched area was monitored over time

using phase-contrast microscopy. (b) In the presence of pre-immune

IgG, numerous cells migrated into the scratch area by 48 h and (c)

the wound was completely closed by 96 h. (d) By contrast, dishes

treated with anti-gicerin IgG showed (e) markedly reduced cell

migration at 48 h and (f) a large cell-free area remained even

after 96 h. These findings indicate that anti-gicerin IgG inhibits

gicerin-mediated cell motility. The dashed straight line indicates

the edge of the wound at each time point after the initial scratch

procedure. Scale bar, 100 µm; magnification: ×100. |

In vitro cell adhesion of the NUGC-4

cells to vascular endothelial cells

When HUVECs were used as a feeder layer and NUGC-4

cells were seeded, a substantial number of NUGC-4 cells adhered to

the surface of HUVECs. Immunofluorescence staining subsequently

revealed that gicerin was positively expressed in the monolayer of

HUVEC cells, as well as in the NUGC-4 cells adhering to them

(Fig. 5B). In this experiment,

two-color staining was attempted to visualize HUVECs, which served

as the feeder layer and the NUGC-4 cells adhered to them. However,

successful fluorescence-based visualization could not be achieved.

The reason for this was that the adhesion of NUGC-4 cells to HUVECs

was weak and during the double-staining procedure, where gicerin on

HUVECs was labeled red with rhodamine and gicerin on NUGC-4 cells

was labeled green using a FITC-conjugated antibody, the NUGC-4

cells detached. Therefore, it was not possible to perform dual

staining with different dyes. In this condition, NUGC-4 cells

adhered to the surface of HUVECs with a small, rounded morphology.

Based on this morphology and the observed fluorescence, both NUGC-4

cells and HUVECs were confirmed to express gicerin, as evidenced by

the green fluorescence emitted by both cell types. Notably, the

fluorescence intensity was stronger in NUGC-4 cells. These findings

clearly demonstrate gicerin positivity in both cell types through

their morphological and fluorescence characteristics.

The addition of an anti-gicerin antibody markedly

decreased the number of NUGC-4 cells that adhered to HUVECs

compared with the addition of pre-immune IgG, demonstrating that

the anti-gicerin antibody could inhibit the adhesion of NUGC-4

cells to vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 5C).

In vitro cell migration assay

To examine the involvement of gicerin in the

migratory potential of NUGC-4 cells, an in vitro scratch

assay were performed. Notably, NUGC-4 cells treated with pre-immune

IgG exhibited markedly greater migration into the scratched area

compared with those treated with anti-gicerin IgG (Fig. 5D). By day 4, the scratched area was

completely closed in the pre-immune IgG group, whereas cell

migration was markedly delayed in the group treated with

anti-gicerin antibody. These findings suggested that gicerin

expression facilitates the migration of NUGC-4 cells.

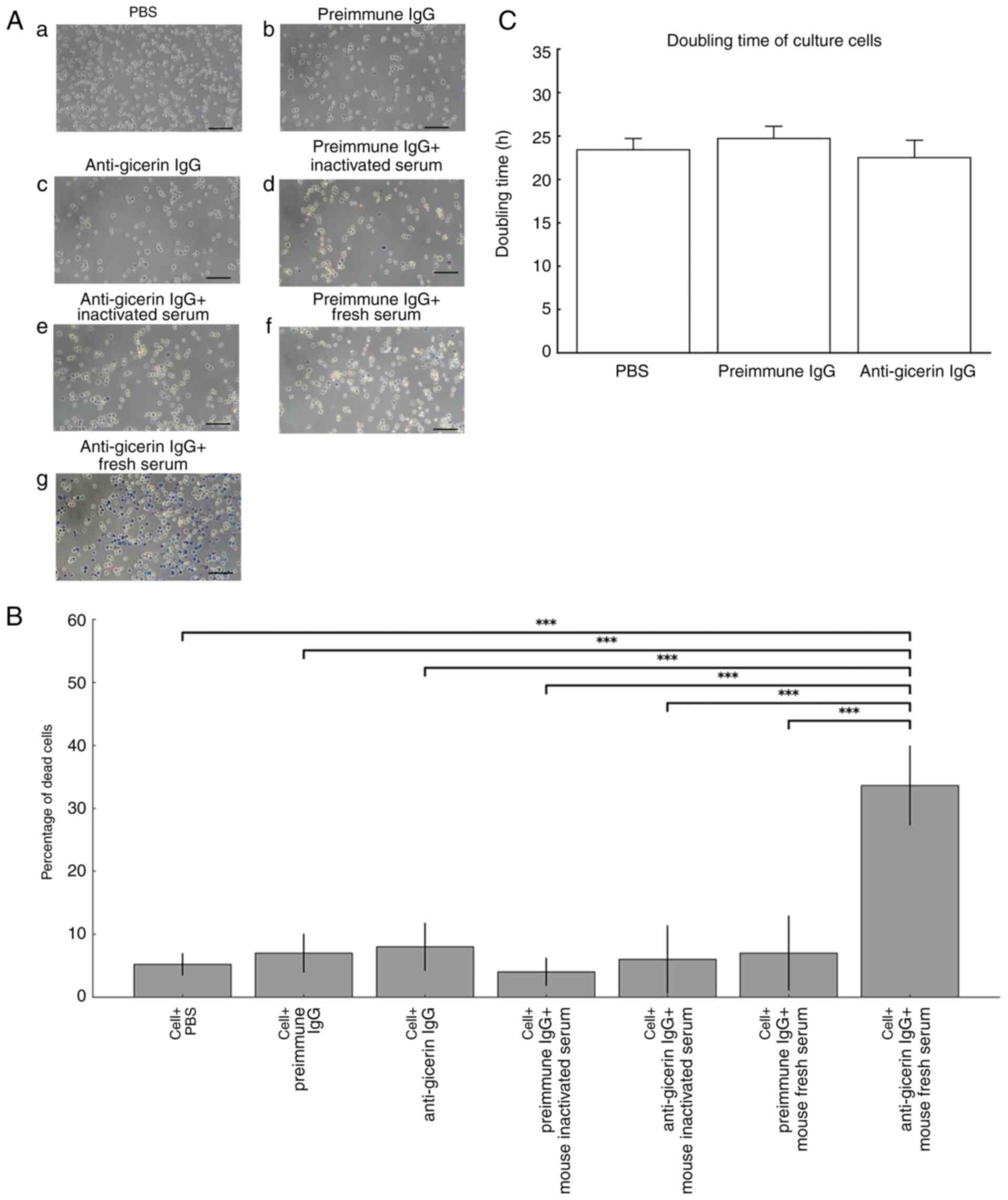

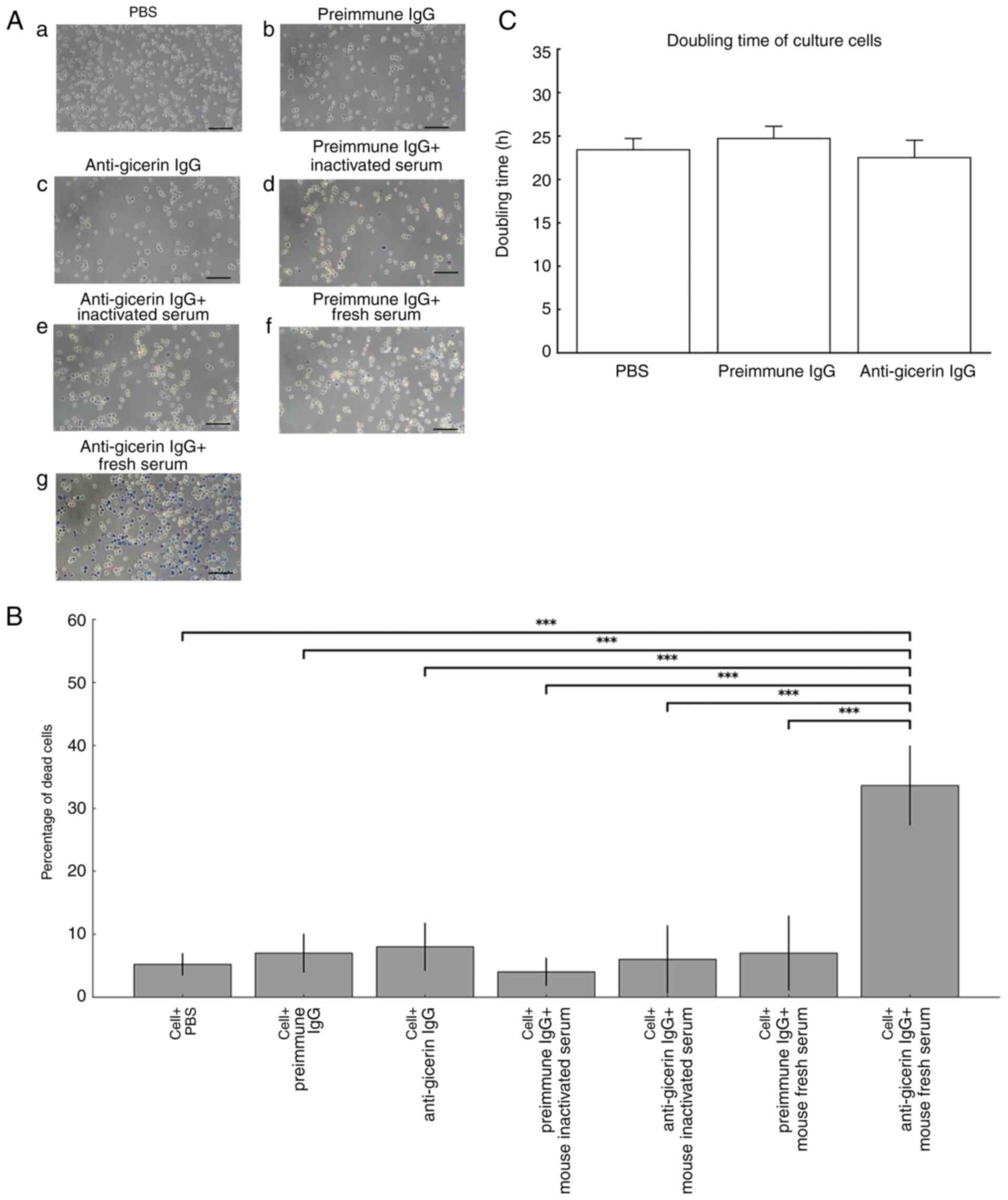

Measurement of cell death by CDC

assay

When pre-immune IgG was used, the addition of fresh

serum did not induce cell death. By contrast, significant levels of

cell death were observed when fresh murine serum was added to

NUGC-4 cells preincubated with anti-gicerin IgG; however, no cell

death occurred when heat-inactivated serum was used (Fig. 6A). Taken together, these results

suggested that complement activity in the serum, engaged by the

anti-gicerin IgG bound to NUGC-4 cells, is responsible for inducing

cell death (Fig. 6B). The doubling

time of NUGC-4 cells was 23.4 h. When pre-immune IgG was added, the

doubling time was 24.7 h and when anti-gicerin IgG was added, it

was 22.5 h (Fig. 6C). These

findings suggest that the addition of anti-gicerin IgG does not

affect the proliferation of gastric cancer cells: no significant

difference between pre-immune IgG and anti-gicerin IgG groups;

(P<0.05).

| Figure 6.Complement-dependent cytotoxicity

assay. (A) NUGC-4 cells were incubated with either pre-immune IgG

or anti-gicerin IgG, followed by treatment with either fresh mouse

serum (complement-active) or heat-inactivated serum (heated at 56°C

for 30 min). After a 1 h incubation at 37°C, non-adherent cells

were removed and adherent cells were detached by treating the cells

with trypsin-EDTA. Cell viability was assessed using the trypan

blue exclusion method under light microscopy (a, with PBS; b, with

pre-immune IgG, c, with anti-gicerin IgG; d, with pre-immune IgG

and inactivated serum; e, with anti-gicerin IgG and inactivated

serum; f, pre-immune IgG and fresh serum; g, with anti-gicerin IgG

and fresh serum. (B) Viable (unstained) and nonviable

(blue-stained) cells were counted and the percentages of dead cells

were calculated. Data are mean ± SD (n=5 independent replicates per

group). Seven groups were compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's

HSD; only the cell + anti-gicerin IgG + fresh mouse serum group

differed markedly from all other groups (***P<0.001). (C)

Doubling times of NUGC-4 cells with anti-gicerin antibody. The

cells were cultured with PBS, pre-immune IgG and anti-gicerin IgG

and doubling times in each condition were calculated. As shown in

the graph, anti-gicerin antibody did not affect the proliferation

of NUGC-4 cells under in vitro conditions, similar to

pre-immune IgG. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=4 independent

replicates per group). Differences among the three groups (PBS,

pre-immune IgG and anti-gicerin IgG) were evaluated by one-way

ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD post hoc test; no statistically

significant differences were detected. |

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that gicerin was

highly expressed in NUGC-4 gastric cancer cells and that the

specific binding of these cells to anti-gicerin antibodies markedly

suppressed subcutaneous tumor growth, local invasion and pulmonary

metastasis in an in vivo model. These observations are all

consistent with previous studies, which suggest that gicerin

fulfills a critical role in tumor metastasis (16,19,20).

Notably, the cell-adhesive properties of gicerin appear to enhance

interactions between tumor cells and the surrounding tissues

(especially muscular and adipose tissues), as well as endothelial

cells, thereby promoting the processes of intravasation, embolus

formation and subsequent extravasation. Indeed, the findings in the

present study have added further support to the hypothesis that

gicerin facilitates in vitro adhesion of gastric cancer

cells to endothelial cells. L-gicerin, which possesses a longer

intracellular domain, has been shown to promote significant

proliferative activity of the cells and metastasis to multiple

organs, thereby driving tumor progression more effectively compared

with S-gicerin, which has a shorter intracellular domain (20,26).

Notably, the NUGC-4 cell line used in the present study expressed

both gicerin isoforms. Although normal muscle tissue likewise

expresses both isoforms, the biological significance of their

co-expression remains poorly understood and elucidating the

interplay between these two isoforms in NUGC-4 cells warrants

further investigation.

Furthermore, the addition of anti-gicerin IgG to the

culture medium was found not to alter the doubling time of tumor

cells in vitro, suggesting that this antibody does not

directly suppress tumor cell proliferation under these conditions.

However, in the mouse subcutaneous tumor model, the presence of

anti-gicerin IgG did markedly inhibit tumor growth, suggesting that

antibody bound to the tumor surface may interact with factors in

the tumor microenvironment, thereby contributing to tumor control

in vivo. Since tumor progression and expansion often involve

interactions between cell adhesion molecules on the tumor surface

and normal tissues, this finding highlighted the potential role of

gicerin as a molecular mediator in these processes. In addition,

the in vitro data generated in the present study

demonstrated that complement components in mouse blood can interact

with anti-gicerin IgG to induce tumor cell death; hence, complement

activation within the tumor milieu may further promote tumor cell

destruction, ultimately reducing tumor growth, local infiltration

and hematogenous metastasis to the lung. During tumorigenesis,

cancer cells not only acquire the ability to evade host regulatory

mechanisms, but also actively manipulate systemic homeostasis to

favor their own survival and proliferation (33). Tumor-derived cytokines and hormones

have been shown to influence key endocrine organs, including the

hypothalamus, pituitary, adrenal glands and thyroid, thereby

modulating central regulatory axes to establish a physiological

milieu conducive to tumor growth and progression. It has been

demonstrated that gicerin mediates homophilic interactions between

gicerin molecules themselves, which facilitate the adhesion of

tumor cells to each other, to vascular tissues and to muscular

structures (16,19,20,34–36).

In addition, heterophilic interactions between gicerin and

extracellular matrix (ECM) components have been suggested to

promote local tissue invasion by tumor cells. These findings

collectively indicate that gicerin may play a multifaceted role in

tumor progression through both structural and signaling mechanisms.

Notably, previous analyses also suggests that gicerin expression

within tumors may contribute to intratumoral angiogenesis, possibly

through factors expressed by tumor cells themselves (16,19,20,36–39).

These mechanisms are not unique to experimental tumor models but

are highly relevant to human gastric cancer as well. The current

study further expanded on this knowledge by using a mouse-derived

anti-gicerin antibody to target gicerin expressed on tumor cells

within a murine model of gastric cancer. Unlike our previous work,

which employed rabbit-derived antibodies to study gicerin function

in tumors of murine and avian origin (16,19,20,34–36),

the present study represented the first attempt, to the best of the

authors' knowledge, to directly target gicerin within a living

mouse using a homologous (murine) antibody. Strikingly, systemic

administration of the mouse-derived anti-gicerin antibody resulted

in widespread necrotic foci within the tumor tissue. This

observation suggested that the murine antibodies, by engaging with

mouse complement proteins, may have efficiently induced

complement-mediated cytotoxicity against gicerin-expressing gastric

cancer cells. This is in contrast to our in vitro findings,

where the same anti-gicerin antibody had no effect on the

proliferation rate (doubling time) of gastric cancer cells. Thus,

the induction of tumor necrosis in vivo appears to be

mediated by immune components present in the host, rather than by

direct effects of the antibody on cell proliferation. In addition

to directly inducing necrosis of the tumor itself, the

mouse-derived anti-gicerin antibody may have disrupted

gicerin-positive neovasculature within the tumor, thereby creating

a hypoxic and energy-deficient microenvironment that led to

secondary tumor cell necrosis. Furthermore, it remains an important

issue for future investigation whether the suppression of gastric

cancer progression by the antibody also involves the induction of

apoptosis in cancer cells.

Additionally, the present study demonstrated that

the antibody markedly suppressed the motility of gastric cancer

cells cultured on gicerin-coated dishes. These findings support the

hypothesis that gicerin plays a critical role in facilitating tumor

cell migration and tissue infiltration, particularly in gastric

cancer. In subsequent studies, it is planned to further dissect the

interaction between gicerin and other adhesion molecules such as

cadherins and vimentin, using in vitro chemotaxis systems

and cell motility analyses in the presence of anti-gicerin

antibodies.

The present study chose recombinant rat gicerin as

the immunogen for antibody production. This decision was based on

previous success in establishing a high-purity, large-scale

production system for recombinant rat gicerin protein, which

enabled the generation of highly sensitive neutralizing antibodies

when used to immunize rabbit (29). By contrast, our attempts to produce

recombinant human gicerin in large quantities were unsuccessful, as

the yield from cultured cells was extremely low and insufficient

for immunization. Given these technical constraints and the

sufficient cross-reactivity of rat gicerin with human gicerin

expressed on NUGC-4 gastric cancer cells, the present study opted

to use recombinant rat gicerin to immunize mice, resulting in the

successful generation of anti-gicerin IgG with potent neutralizing

activity. Inhibitory anti gicerin monoclonal antibodies (such as

AA98) bind the D4-D5 junction, stabilize the monomeric form and

thereby suppress dimerization dependent signaling and cell

migration (40). These functional

surfaces (loops on D1 and D4-D5) are structurally conserved among

mammals. The antibody in the present study was murine polyclonal,

so it probably contained multiple IgG species that collectively

recognize several conserved epitopes on human gicerin, which is

consistent with the broad neutralization observed in

adhesion/invasion/metastasis assays. The antibodies in the present

study were not raised against a short peptide. Instead, it

immunized with a purified recombinant rat gicerin soluble

extracellular domain encompassing all five Ig like domains. The

resulting product is a mouse polyclonal IgG (anti gicerin IgG)

purified to high homogeneity. As the immunogen was the full

ectodomain, the antibody preparation necessarily recognizing

multiple linear and conformational epitopes distributed across the

extracellular domains. Therefore, there is no single ‘epitope

location’ or ‘peptide sequence’ applicable to this polyclonal.

Despite overall 70–72% identity between rat and

human gicerin/CD146 in the extracellular region, functionally

important surfaces within the Ig like domains are conserved. Prior

structural work shows that inhibitory anti gicerin monoclonal

antibodies (mAbs) can bind the D4-D5 interface and attenuate

dimerization/activation. It is hypothesized that our polyclonal

anti rat gicerin IgG contains subpopulations recognizing such

conserved epitopes on human gicerin, which explained the

neutralization of adhesion/invasion/metastasis observed in NUGC 4

cells. The present study did not perform epitope mapping. As follow

up, it is planned to i) test binding to isolated human gicerin

domain fragments (D1-D5), ii) run peptide competition or Pepscan

ELISAs focusing on conserved surface loops within D1 and D4-D5 and

iii) evaluate blocking against a reference inhibitory anti

gicerin/CD146 mAb (e.g., AA98) to determine overlap. These

experiments will pinpoint the dominant neutralizing epitopes.

In the development of antibody-based therapies,

these results underscore the dual role of gicerin in gastric

cancer: not only as a structural adhesion molecule that facilitates

tumor dissemination, but also as an immunological target whose

inhibition may trigger tumor necrosis through host immune

mechanisms. These findings collectively highlighted gicerin as a

promising therapeutic target for the treatment of gastric

cancer.

Nevertheless, further studies are warranted, both to

clarify whether anti-gicerin antibodies primarily interfere with

homophilic or with heterophilic binding and to elucidate the

functions of distinct isoforms, if any should exist. Additional

investigations focusing on established tumors and the possible

synergistic effects of anti-gicerin therapy in combination with

standard chemotherapy will be essential in order to define the

clinical applicability of this strategy. Overall, these findings

have strongly supported the potential usefulness of gicerin as a

molecular target in the treatment of gastric cancer.

Gastric cancer cells actively shape their tumor

microenvironment (TME) through several mechanisms that promote

tumor survival, invasion and metastasis (41). First, gastric cancer cells secrete

a range of cytokines and growth factors, such as VEGF, IL-6 and

TGF-β, that modulate angiogenesis, stromal remodeling and immune

cell recruitment. These factors contribute to the creation of a

pro-tumorigenic environment by promoting vascularization,

suppressing immune surveillance and enabling ECM degradation.

Secondly, studies have shown that gastric cancer cells can induce

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages toward an M2-like

phenotype, which in turn supports tumor progression by secreting

anti-inflammatory cytokines and matrix-remodeling enzymes. In

addition, cancer-associated fibroblasts, often activated by

tumor-derived signals, secrete ECM components and

metalloproteinases that facilitate tumor cell migration and local

invasion (4,33,41).

Importantly, the present study suggested that the cell adhesion

molecule gicerin may also participate in regulating the TME of

gastric cancer. Gicerin-mediated interactions between tumor cells

and endothelial or stromal cells may facilitate intravasation and

immune evasion. Moreover, the observed complement-dependent

cytotoxicity induced by anti-gicerin antibodies in vivo

implied that gastric cancer cells may exploit gicerin to avoid

complement activation under normal conditions, thereby maintaining

TME homeostasis favorable to tumor growth.

However, when administering anti-gicerin antibodies

to tumor-bearing animals, it is necessary to pretreat the antibody

so as to minimize complement activation in the circulation. This

cautionary measure arises from the fact that normal vascular and

muscular tissues constitutively express gicerin; specifically,

inadvertent binding of the antibody, followed by complement

activation, could have deleterious effects on healthy tissues.

Indeed, our preliminary pilot investigations revealed that the

intravenous administration of intact anti-gicerin IgG to healthy

mice induced pulmonary edema as a serious adverse event.

Accordingly, before proceeding with in vivo therapeutic

evaluations, there is a need to optimize the antibody protein to

circumvent complement-mediated toxicity, which will thereby enhance

the safety profile of this promising therapeutic strategy.

Collectively, the observed suppression of gastric

cancer progression in vivo by the antibody may be attributed

to the complement-mediated cytotoxic effect induced by anti-gicerin

antibody in mice, as well as the inhibition of hematogenous

metastasis and local tissue invasion through suppression of cell

adhesion between gastric cancer cells and vascular endothelium.

Cadherins are known to strengthen intercellular adhesion and their

loss or mutation is associated with increased cancer cell invasion

and metastasis. By contrast, cell adhesion molecules belonging to

the immunoglobulin superfamily, such as gicerin, may play an

opposing role. These findings support the concept that, in

vivo, tumor progression is finely regulated by a complex

network of multiple adhesion molecules and related factors.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SU was responsible for conceptualization of the

project, performing the investigation, data analysis, writing and

reviewing the manuscript and editing. NU was responsible for

devising the methodology and validation of the data. KA performed

the animal experiments. YT was responsible for conceptualization of

the project, project administration, the acquisition of funding and

preparation of the original draft of the manuscript. SU and YT

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The use of HUVECs in this study was approved by the

institutional review committee of Kyoto Prefectural University

(Kyoto, Japan) at the time of cell purchase (approval no.

OSP20190889). All animal experiments conducted in this study were

reviewed for their scientific rationale and ethical justification

and were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Kyoto

Prefectural University (approval no. KPU240401). The authors

declare that the animal experiment in this study was reviewed and

approved by the institutional ethics committee without the

participation of the project leader or any of the applicants in the

review and approval process.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cunningham BA: Cell adhesion molecules and

signal transduction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 7:628–633. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Albelda SM: Role of integrins and other

cell adhesion molecules in tumor progression and metastasis. Lab

Invest. 68:4–17. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Takeichi M: Cadherins in cancer:

Implications for invasion and metastasis. Curr Opin Cell Biol.

5:806–811. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Janiszewska M, Primi MC and Izard T: Cell

adhesion in cancer: Beyond the migration of single cells. J Biol

Chem. 295:2495–2505. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Berx G and van Roy F: The

E-cadherin/catenin complex: An important gatekeeper in breast

cancer tumorigenesis and malignant progression. Breast Cancer Res.

3:289–293. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Desgrosellier JS and Cheresh DA: Integrins

in cancer: Biological implications and therapeutic opportunities.

Nat Rev Cancer. 10:9–22. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rathinam R and Alahari SK: Important role

of integrins in the cancer biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

29:223–237. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Jung H, Jun KH, Jung JH, Chin HM and Park

WB: The expression of claudin-1, claudin-2, claudin-3, and

claudin-4 in gastric cancer tissue. J Surg Res. 167:e185–e191.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Chen DL, Zeng ZL, Yang J, Ren C, Wang DS,

Wu WJ and Xu RH: L1cam promotes tumor progression and metastasis

and is an independent unfavorable prognostic factor in gastric

cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 6:432013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lu G, Cai Z, Jiang R, Tong F, Tu J, Chen

Y, Fu Y, Sun J and Zhang T: Reduced expression of E-cadherin

correlates with poor prognosis and unfavorable clinicopathological

features in gastric carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY).

16:10271–10298. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gu L, Chen M, Guo D, Zhu H, Zhang W, Pan

J, Zhong X, Li X, Qian H and Wang X: PD-L1 and gastric cancer

prognosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One.

12:e01826922017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Chen DH, Yu JW and Jiang BJ: Contactin 1:

A potential therapeutic target and biomarker in gastric cancer.

World J Gastroenterol. 21:9707–9716. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Singh P, Toom S and Huang Y: Anti-claudin

18.2 antibody as new targeted therapy for advanced gastric cancer.

J Hematol Oncol. 10:1052017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tsukamoto Y, Taira E, Kotani T, Yamate J,

Wada S, Takaha N, Miki N and Sakuma S: Involvement of gicerin, a

cell adhesion molecule, in tracheal development and regeneration.

Cell Growth Differ. 7:1761–1767. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Adachi K, Hattori M, Kato H, Inai M,

Tsukamoto M, Handharyani E, Taira E and Tsukamoto Y: Involvement of

gicerin, a cell adhesion molecule, in the portal metastasis of rat

colorectal adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 24:1427–1431.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tsukamoto Y, Matsumoto T, Kotani T, Taira

E, Takaha N, Miki N, Yamate J and Sakuma S: The expression of

gicerin, a cell adhesion molecule, in regenerating process of

collecting ducts and ureters of the chicken kidney after the

nephrotrophic strain of infectious bronchitis virus infection.

Avian Pathol. 26:245–255. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tsukamoto Y, Taira E, Yamate J, Nakane Y,

Kajimura K, Tsudzuki M, Kiso Y, Kotani T, Miki N and Sakuma S:

Gicerin, a cell adhesion molecule, participates in the histogenesis

of retina. J Neurobiol. 33:769–780. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsukamoto Y, Sakaiuchi T, Hiroi S, Furuya

M, Tsuchiya S, Sasaki F, Miki N and Taira E: Expression of gicerin

enhances the invasive and metastatic activities of a mouse mammary

carcinoma cell line. Int J Oncol. 23:1671–1677. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tsukamoto Y, Egawa M, Hiroi S, Furuya M,

Tsuchiya S, Sasaki F, Miki N and Taira E: Gicerin, an

Ig-superfamily cell adhesion molecule, promotes the invasive and

metastatic activities of a mouse fibroblast cell line. J Cell

Physiol. 197:103–109. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Taira E, Takaha N, Taniura H, Kim CH and

Miki N: Molecular cloning and functional expression of gicerin, a

novel cell adhesion molecule that binds to neurite outgrowth

factor. Neuron. 12:861–872. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Taira E, Nagino T, Taniura H, Takaha N,

Kim CH, Kuo CH, Li BS, Higuchi H and Miki N: Expression and

functional analysis of a novel isoform of gicerin, an

immunoglobulin superfamily cell adhesion molecule. J Biol Chem.

270:28681–28687. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kong JH, Lee J, Yi CA, Park SH, Park JO,

Park YS, Lim HY, Park KW and Kang WK: Lung metastases in metastatic

gastric cancer: Pattern of lung metastases and clinical outcome.

Gastric Cancer. 15:292–298. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Niimi T, Samejima J, Koike Y, Miyoshi T,

Tane K, Aokage K, Taki T, Ishii G and Tsuboi M: A case of lung

metastasis from gastric cancer presenting as ground-glass opacity

dominant nodules. J Cardiothorac Surg. 19:3652024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Chen ZR, Yang MF, Xie ZY, Wang PA, Zhang

L, Huang ZH and Luo Y: Risk stratification in gastric cancer lung

metastasis: Utilizing an overall survival nomogram and comparing it

with previous staging. World J Gastrointest Surg. 16:357–381. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rabben HL, Kodama Y, Nakamura M, Bones AM,

Wang TC, Chen D, Zhao CM and Øverby A: Chemopreventive effects of

dietary isothiocyanates in animal models of gastric cancer and

synergistic anticancer effects with cisplatin in human gastric

cancer cells. Front Pharmacol. 12:6134582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li W, Zhao X, Wang H, Liu X, Zhao X, Huang

M, Qiu L, Zhang W, Chen Z, Guo W, et al: Maintenance treatment of

Uracil and Tegafur (UFT) in responders following first-line

fluorouracil-based chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer: A

randomized phase II study. Oncotarget. 8:37826–37834. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Akiyama S, Amo H, Watanabe T, Matsuyama M,

Sakamoto J, Imaizumi M, Ichihashi H, Kondo T and Takagi H:

Characteristics of three human gastric cancer cell lines, NU-GC-2,

NU-GC-3 and NU-GC-4. Jpn J Surg. 18:438–446. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Taira E, Kohama K, Tsukamoto Y, Okumura S

and Miki N: Characterization of Gicerin/MUC18/CD146 in the rat

nervous system. J Cell Physiol. 198:377–387. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Taira E, Nagino T, Tsukamoto Y, Okumura S,

Muraoka O, Sasaki F and Miki N: Cytoplasmic domain is not essential

for the cell adhesion activities of gicerin, an Ig-superfamily

molecule. Exp Cell Res. 253:697–703. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Taniura H, Kuo CH, Hayashi Y and Miki N:

Purification and characterization of an 82-kD membrane protein as a

neurite outgrowth factor binding protein: Possible involvement of

NOF binding protein in axonal outgrowth in developing retina. J

Cell Biol. 112:313–322. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Spyridopoulou K, Aindelis G, Lampri E,

Giorgalli M, Lamprianidou E, Kotsianidis I, Tsingotjidou A, Pappa

A, Kalogirou O and Chlichlia K: Improving the subcutaneous mouse

tumor model by effective manipulation of magnetic

nanoparticles-treated implanted cancer cells. Ann Biomed Eng.

46:1975–1987. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Slominski RM, Raman C, Chen JY and

Slominski AT: How cancer hijacks the body's homeostasis through the

neuroendocrine system. Trends Neurosci. 46:263–275. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Tsukamoto Y, Taira E, Miki N and Sasaki F:

The role of gicerin, a novel cell adhesion molecule, in

development, regeneration and neoplasia. Histol Histopathol.

16:563–571. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tsuchiya S, Tsukamoto Y, Furuya M, Hiroi

S, Miki N, Sasaki F and Taira E: Gicerin, a cell adhesion molecule,

promotes the metastasis of lymphoma cells of the chicken. Cell

Tissue Res. 314:389–397. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kirimura N, Kubota Y, Adachi K and

Tsukamoto Y: Involvement of gicerin, a cell adhesion molecule, in

the hematogenous metastatic activities of a melanoma cell line. Am

Int J Biol. 2:65–75. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Kohama K, Tsukamoto Y, Fruya M, Okamura K,

Tanaka H, Miki N and Taira E: Molecular cloning and analysis of the

mouse gicerin gene. Neurochem Int. 46:465–470. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Taira E, Kohama K, Tsukamoto Y, Okumura S

and Miki N: Gicerin/CD146 is involved in neurite extension of

NGF-treated PC12 cells. J Cell physiol. 204:632–637. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Tsuchiya S, Tsukamoto Y, Taira E and

LaMarre J: Involvement of transforming growth factor-beta in the

expression of gicerin, a cell adhesion molecule, in the

regeneration of hepatocytes. Int J Mol Med. 19:381–386.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen X, Yan H, Liu D, Xu Q, Duan H, Feng

J, Yan X and Xie C: Structure basis for AA98 inhibition on the

activation of endothelial cells mediated by CD146. iScience.

24:1024172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Matsuoka T and Masakazu Y: Molecular

mechanism for malignant progression of gastric cancer within the

tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 25:117352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|