Introduction

The liver has a strong regenerative capacity;

however, chronic injury can lead to extracellular matrix

accumulation, fibrosis and eventually liver failure, representing a

major global health burden (1). In

2022, liver diseases such as cirrhosis, viral hepatitis and

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounted for 2 million deaths

worldwide (2). In China, the

increasing prevalence of liver diseases highlights the requirement

for more effective therapies (3).

Conventional treatments offer limited efficacy in conditions such

as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), alcoholic liver disease

(ALD) and HCC (4–7). Therefore, it is important to identify

shared molecular mechanisms to improve the diagnosis of liver

diseases and identify more effective treatment strategies.

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), a key enzyme

in the DNA damage response (DDR), also regulates cellular

metabolism by modulating oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

(NAD+) levels and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activity (8–10).

PARP-1 expression is upregulated in both primary and recurrent HCC

and has been implicated in chemoresistance (11). The involvement of PARP-1 in the

progression of various liver diseases, including non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease (NAFLD), ALD and HCC, suggests its potential as

a therapeutic target (12–14).

Unlike previous studies focusing on single disease

types, the present review comprehensively analyzes the role of

PARP-1 in multiple liver pathologies, including NASH, ALD, fibrosis

and HCC, revealing shared molecular mechanisms. The dual role of

PARP-1 in liver diseases is systematically summarized, and its

functions in liver regeneration and pathological fibrosis are

integrated to provide a comprehensive understanding of its

regulatory mechanisms. In addition to summarizing established

evidence, novel mechanistic insights into the regulation of tumor

metabolism, transcriptional programming and immune microenvironment

remodeling by PARP-1 in HCC are discussed, and the therapeutic

synergy between PARP inhibitors and immune checkpoint blockade is

highlighted. Furthermore, the translational potential of PARP-1

inhibitors for autoimmune liver diseases (AILDs) is proposed based

on preclinical evidence, addressing a critical research gap.

Overall, the present review synthesizes current knowledge on the

expression, regulatory networks and mechanisms of PARP-1 in various

liver diseases, ultimately evaluating its clinical diagnostic and

therapeutic value.

Overview of liver disease

In 2022, liver disease resulted in 2 million

fatalities worldwide, or 4% of total deaths globally, ranking it as

the 11th largest cause of death (2). The main causes of mortality are

complications arising from cirrhosis and HCC, while acute hepatitis

accounts for a lower proportion of fatalities. The primary global

causes of cirrhosis include viral hepatitis, alcohol use and NAFLD,

which lead to a progressive deterioration of hepatic function.

Other factors also contribute to liver disease, including age, sex,

body composition, diet, physical activity, microbiome, and history

of alcohol and tobacco use (15).

The liver performs essential biological tasks such

as protein synthesis, glucose and lipid metabolism, detoxification

and bile production. It exhibits marked immunological activity and

functions as a systemic barrier against intestinal infections and

toxins by maintaining a localized immune-regulating milieu and

promoting tolerance to prevalent antigens (16). Optimal liver function is essential

for the body to effectively combat bacteria and viruses; therefore,

individuals with liver dysfunction are particularly susceptible to

infections (17). The immune

response generated by the liver relies upon its distinctive

architecture, the presence of essential immune cells such as

Kupffer cells (KCs), continuous immunological surveillance and

rapid recruitment of immune cells (16,18).

Chronic alcohol use increases the permeability of the gut to

bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (19), elevates endotoxin levels in the

hepatic portal vein, and activates KCs via interactions with

Toll-like receptor-4 (14).

The liver has strong regenerative capacity and can

recover considerably after resection. However, conditions such as

ALD and chronic hepatitis B (CHB) may overly activate this

regenerative response, resulting in the excessive accumulation of

extracellular matrix and collagen, leading to liver fibrosis.

Furthermore, decompensated liver fibrosis leads to the formation of

hepatic scar tissue, which is known as cirrhosis. This

significantly reduces liver function, and may progress to liver

failure and death (1).

PARP-1, a DNA repair enzyme, plays a key role in

hepatocyte apoptosis by promoting cell death and increasing the

synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators when overactivated by ROS

and reactive nitrogen species, thereby influencing the self-healing

capacity of the liver (10). NAFLD

is a major contributor to chronic liver disease (CLD), with a

spectrum ranging from moderate steatosis to advanced NASH. NASH is

characterized by inflammation and progressive hepatocyte injury,

which can lead to cirrhosis (20)

and subsequently increase the risk of HCC.

Overview of PARP-1

PARPs are ADP-ribosyltransferases that catalyze

ADP-ribosylation, a post-translational protein modification.

ADP-ribosylation involves the cleavage of NAD+ to

generate single ADP-ribose units, oligomers or polymers that are

covalently linked to serine, glutamate, aspartate, arginine and

lysine residues in target proteins (21). The PARP family comprises 17

proteins, with PARP-1 accounting for 85–90% of total PARP activity

(22). PARP-1 contains several

conserved and functionally distinct domains, including an

auto-modification domain, a 55-kDa catalytic domain, and two zinc

finger domains responsible for DNA binding (23).

PARP-1 is present in all human tissues, with the

highest concentrations in the lymph nodes, appendix, brain,

placenta, prostate, spleen and testes. It is an essential element

in the DNA base excision repair mechanism (24,25)

and participates in the repair of single-strand and double-strand

breaks (DSBs) (26). Human PARPs,

namely PARP-1, −2 and −3, are categorized as DDR proteins because

of their involvement in DNA repair and reliance on DNA damage for

activation (22). Among these,

PARP-1 is the predominant enzyme, characterized by its abundance

and strong enzymatic activity. It serves as the principal signaling

factor in DDR, where its rapid activation is the most critical

stage in the DDR process (8).

PARP-1 serves as a primary sensor of DNA damage, capable of

detecting DNA breaks within 3 sec of their occurrence, and triggers

the recruitment of repair complexes via the ADP-ribosylation of

proteins near the damage site. Its activity is further influenced

by co-factors, such as histone PARylation factor 1 (HPF1), which

enhances the catalytic activity of PARP-1 and modifies substrate

selectivity. HPF1 interacts with the PARP-1 catalytic domain and

colocalizes with it at sites of DNA damage (8).

A study evaluating the hepatotoxicity of columbin

(CLB) demonstrated that CLB induces DNA damage both in vitro

and in vivo, which is associated with the upregulation of

PARP-1 (27). PARP-1 also

interacts with SIRTs. SIRT1-7 are a family of

NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases with extensive roles

in metabolism and aging. In the absence of PARP-1, NAD+

levels rise, potentially increasing SIRT1 activity (22,28).

In addition, PARP-1 and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)

mutually reinforce each other: The activation of PARP-1 stimulates

AMPK, which in turn phosphorylates and activates PARP-1. Within the

reactive oxygen species (ROS)-PARP-1-AMPK pathway, the interaction

between PARP-1 and AMPK promotes the nuclear export of AMPK, which

induces autophagic flux and cellular apoptosis (22,29).

PARP-1 plays an essential role in DNA repair and

cellular stress responses in the liver. During oxidative stress,

such as exposure to hydrogen peroxide, PARP-1 activation preserves

hepatocyte survival, while PARP-1 inhibition or genetic ablation in

primary hepatocytes diminishes oxidation-induced necrotic cell

death, suggesting a preventive mechanism against oxidative injury

(10).

A pilot study revealed that PARP-1 knockout mice

exhibit impaired liver regeneration and reduced hepatocyte

proliferation. It also showed that PARP-1 is required for both the

early liver response and late tissue repair during liver

regeneration, and that PARP-1 inhibitors can reduce hepatocyte

proliferation (30). These results

indicate that PARP-1 and its catalytic activity are essential for

hepatocyte proliferation. This effect appears to be associated with

Yes-associated protein (YAP), a key driver of hepatocyte

proliferation (31). In PARP-1

knockout mice, YAP activity and the expression of cell

cycle-related proteins in liver tissue are suppressed, resulting in

reduced hepatocyte proliferation and impaired liver repair during

liver regeneration (30). However,

another study showed that chronic or excessive activation, such as

that observed in severe or long-standing liver disease, depletes

NAD+ and promotes fibrosis, ultimately impairing liver

regeneration (32). In view of

this duality, the inhibition of pathological activation while

retaining the beneficial functions of PARP-1 is a therapeutic

challenge.

Chromatin relaxation is essential for efficient DNA

repair, and PARP-1 functions as a crucial mediator of this process.

The inhibition of PARP-1 activity directly affects chromatin

structure. Through poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, PARP-1 binds to and

modifies chromatin remodelers, thereby altering chromatin structure

and facilitating the ensuing DDR (33).

PARP-1 also plays a pivotal role in inflammation. It

activates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), nuclear factor of activated T

cells and activator protein 1, leading to the production of

inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)

and interleukin (IL)-1β, and effector T cell cytokines, including

IL-4 and IL-5. Excessive activation of PARP-1 promotes cell death

and tissue damage, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory response

(34). These functions are

particularly relevant to chronic inflammatory liver conditions,

including viral hepatitis, ALD and drug-induced liver injury

(DILI).

PARP-1 is essential for sustaining proper immune

function, and its dysregulation contributes to immune-mediated

disorders. Under physiological conditions, PARP-1 expression is

typically low but becomes significantly upregulated during early

liver injury, chronic liver fibrosis and HCC (10). Consequently, aberrant PARP-1

activity is associated with the progression of several liver

disorders.

Function of PARP-1 in liver disease

Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis

Viral infection is a major cause of acute hepatitis,

which leads to elevated liver transaminase levels and impaired

liver function (35). China is

among the top 20 nations with the highest viral hepatitis burdens.

Between 2016 and 2022, the proportion of people living with viral

hepatitis confirmed hepatitis B cases in China increased from 19 to

24%, while that of hepatitis C cases increased from 22 to 33%

(36). CHB infection is the major

cause of HCC. Transforming viral proteins such as hepatitis B virus

(HBV) regulatory protein X (HBx) are key oncogenic factors

(37). HBx induces the degradation

of the structural maintenance of chromosome 5/6 complex, a process

implicated in HBV-related HCC. This impairs homologous

recombination (HR)-mediated DNA repair, thereby contributing to

carcinogenesis. The accumulation of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)

breaks in cancer cells with HR deficit (HRD) can be lethal. PARP-1

inhibition prevents the repair of single-strand DNA breaks, which

subsequently exacerbates the accumulation of dsDNA breaks (38,39).

In addition to altering protein function, HBV infection regulates

the expression of certain long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in

infected cells. For example, HBx inhibits p53 activity, leading to

the upregulation of lncRNA-HUR1 expression, which promotes cell

proliferation and cancer progression (40). The overexpression of lncRNA-HUR1

reduces caspase-3/7 activity and PARP-1 cleavage, while lncRNA-HUR1

knockdown increases caspase-3/7 activity and promotes PARP-1

cleavage (41). Together, these

findings underscore the crucial role of PARP-1 in HBV-induced

HCC.

In addition to HBV, other viral hepatitis subtypes

may also interact with DNA damage and repair pathways. Although

PARP-1 has not been extensively studied in these contexts, existing

data suggest a potential involvement that is worthy of further

exploration. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a leading cause of CLD and

HCC that induces persistent oxidative stress and DNA damage in

infected hepatocytes. Viral proteins, including core protein and

the non-structural (NS) proteins NS3 and NS5A disrupt host DNA

repair pathways by targeting key components, such as the ataxia

telangiectasia-mutated (ATM)-nibrin-meiotic recombination 11

complex, thereby promoting chromosomal instability and malignant

transformation (42,43). Although direct studies of PARP-1 in

HCV-infected liver tissue are limited, the well-established roles

of this enzyme in DDR and inflammation suggest that PARP-1 may be

activated under conditions of HCV-induced genomic stress,

potentially contributing to fibrosis and cancer progression.

Hepatitis D virus (HDV), which often co-occurs with HBV, is

associated with more severe disease and heightened oxidative stress

(44), factors that may also

induce PARP-1 activation. However, direct evidence associating

PARP-1 with HDV-induced liver injury is lacking.

Collectively, these observations highlight the

importance of investigating the role of PARP-1 in diverse forms of

viral hepatitis, as its regulatory role in DNA repair, cell death

and the inflammatory response may have major implications for the

diagnosis and treatment of various liver infections.

ALD

Liver damage, inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis and

cancer resulting from prolonged or excessive alcohol consumption

are hallmarks of ALD. With 3.3 million associated fatalities, or 6%

of all deaths globally, alcohol-related damage is one of the most

prevalent preventable causes of mortality. Liver damage occurs in

20–30% of individuals who misuse alcohol (45). A key pathogenic characteristic of

ALD is hepatocyte apoptosis mediated by PARP-1. Under normal

physiological conditions, alcohol dehydrogenase is the primary

enzyme that metabolizes ethanol in the liver. However, chronic

alcohol intake stimulates the expression of cytochrome P450 2E1,

which metabolizes ethanol to acetaldehyde and produces considerable

amounts of ROS as byproducts (46). Acetaldehyde is a toxic metabolite

that forms adducts with cellular macromolecules and further

amplifies oxidative stress. ROS can induce oxidative DNA damage,

which is sensed by PARP-1 and activates the TGF-β1-Smad pathway. In

the early stages of DNA damage, PARP-1 binds to sites of DNA damage

and uses NAD+ as a substrate to synthesize PARPs

including PARP-1 (47). However,

persistent or severe DNA damage leads to the overactivation of

PARP-1, which consumes large amounts of NAD+ for

poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, leading to NAD+ and ATP

depletion along with impaired mitochondrial function and energy

metabolism, ultimately triggering hepatocyte necrosis or monocytic

cell death (48,49).

Preventing and treating ALD requires the reversal of

this imbalance caused by PARP-1 overactivation that leads to

hepatocyte necrosis or monocyte death (50). In ALD, hepatocytes and liver

macrophages exhibit upregulated C-C chemokine ligand type 2 (CCL2)

levels. A pharmacological study of mice revealed that

alcohol-induced liver damage can be prevented or reversed by

blocking the activation of C-C chemokine receptor type 2 and 5

(51). Alcohol-induced increases

in PARP-1 activity have also been shown to mediate hepatocyte

apoptosis (14,52). In Raw264.7 macrophages, PARP-1

activation promotes the nuclear translocation of LPS-induced NF-kB,

and increased KC activation exacerbates alcohol-induced liver

steatosis by increasing hepatic M1 macrophage marker gene

expression. Consistent with this, treatment of mice with the PARP-1

inhibitor PJ34 downregulates hepatic M1 marker gene expression

(14). This suggests that limiting

KC activation helps to restore hepatic lipid balance, an important

protective mechanism of PARP-1 inhibition in alcohol-induced

hepatic steatosis. Certain medications, such as cenicriviroc, have

been demonstrated to reduce hepatocyte apoptosis and alleviate

CCL2-induced hepatic steatosis (52).

NAFLD

Based on histological features, NAFLD can be

classified as NASH, which comprises <20% of cases, and

non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), which comprises the remaining

>80% (53,54). NAFL is defined as hepatic steatosis

without substantial hepatocyte injury, or minor lobular

inflammation is present, while NASH is characterized by hepatocyte

damage in addition to steatosis (54). With an estimated global incidence

of 25%, NAFLD is a growing public health concern. In the United

States, severe NASH is now the second most frequent indication for

liver transplantation in men and the most common indication in

women (55). Nearly 75% of

individuals in the United States with risk factors such as diabetes

and obesity develop NAFLD (56).

In early NAFLD, the gut vascular barrier is

disrupted, which allows intestinal bacteria to proliferate, leading

to increased translocation of LPS to the liver, thereby triggering

pyroptosis. LPS stimulation also activates PARP-1, which increases

signaling via NF-κB, a crucial transcription factor that regulates

the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Specifically, PARP-1

interacts with transcription factors and co-activators, including

p300, to increase the transcriptional activity of NF-κB. This then

influences the expression of cytokines and other pro-inflammatory

mediators, including inducible nitric oxide synthase and

cyclooxygenase-2, thereby contributing to the inflammatory response

in hepatic tissue (34). In

high-fat diet (HFD)-induced mouse models, DNA damage activates

PARP-1, which stimulates the activation of NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3 (NLRP3) and its downstream signaling proteins

(57). This is associated with

increased levels of cleaved PARP-1 together with elevated blood

levels of IL-1β and C-reactive protein (58). Beyond inflammation, the development

of NAFLD is strongly influenced by the SIRT1/AMPK pathway and

NAD+ homeostasis. PARP-1 contributes to this

dysregulation by depleting NAD+ and interfering with

SIRT1 activity, which is essential for AMPK activation (59). SIRT1 modulates hepatic lipid

metabolism by regulating the activity of peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) (60). PARP-1 activity also disrupts

hepatic lipid homeostasis by modulating the SIRT1/PPARα axis. It

depletes intracellular NAD+, directly

poly(ADP-ribosyl)ates PPARα, and impairs both SIRT1 activity and

the PPARα-mediated transcription of β-oxidation genes, leading to

suppressed mitochondrial function and fatty acid oxidation

(61,62). This promotes lipid accumulation and

the progression of steatosis. By contrast, the activation of SIRT1

enhances hepatic lipid catabolism and mitochondrial efficiency,

serving as a critical counterbalance in the maintenance of

metabolic adaptation during NAFLD progression (63). Collectively, these insights

highlight the pivotal regulatory function of the PARP-1/SIRT1/PPARα

axis in the pathophysiology of NAFLD.

DILI

Unanticipated liver damage caused by drugs or other

xenobiotics, known as DILI, is a major concern in clinical trials

and drug development (64). A wide

range of agents, including medications, natural products and

supplements, can cause DILI (65).

DILI is challenging to diagnose, requires the rigorous elimination

of other causes, and is underreported to pharmacovigilance

authorities; therefore, its prevalence is challenging to determine

(66,67). While traditional and nutritional

supplements are the primary causes of DILI in Asia, drug responses

to conventional pharmaceuticals are most prevalent in the United

States and Europe (67). With an

estimated 23.8 cases per 100,000 individuals, the frequency of DILI

is high in China (68). However,

the actual incidence could be much higher than this.

The mechanisms underlying liver injury vary

depending on the causative agents. Experimental models hased on

DILI principles have been developed to assess the efficacy of liver

protective and anti-fibrosis interventions. For example, carbon

tetrachloride can induce liver fibrosis and injury, processes that

are often accompanied by DNA damage and repair processes, with

PARP-1 playing a key role in the DDR (49). The overactivation of PARP-1

promotes the binding of transcription factor activator protein 1 to

the TGF-β1 gene, leading to chronic chemical damage in human and

animal liver cells (69). Another

example of a liver injury-inducing agent is CLB, which increases

ROS production and depletes glutathione. The resulting oxidative

stress promotes DNA breaks and upregulates PARP-1 expression

(27).

PARP-1 is activated during acetaminophen overdose,

resulting in poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of the pregnane X receptor.

This post-translational modification augments the transcription of

the cytochrome P450, family 3, subfamily A, polypeptide 11 enzyme,

thereby increasing the production of toxic acetaminophen

metabolites (70). Furthermore,

anti-tuberculosis medications, including isoniazid and rifampicin,

can induce marked hepatic damage by inducing an inflammatory

response and oxidative stress, subsequently activating the NLRP3

inflammasome. This induces PARP-1 activation, which contributes to

hepatic damage (71).

AILD

There are three principal types of AILD, a chronic

immune-mediated illness that affects hepatic and bile duct cells,

which are autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis

(PBC) and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (72,73).

A clinical phenotype known as overlap syndrome occurs when symptoms

of multiple categories co-exist within the spectrum of AILD;

however, the majority of patients fit the criteria of one specific

type (74). AILD has a

male-to-female ratio of 1:5, and an annual yearly incidence

worldwide of 1.37 cases per 100,000 individuals. PBC mostly affects

women, and has a prevalence of 39.2 per 100,000 in the United

States and 4.75 per 100,000 in Korea (75).

Studies have shown that the pathophysiology of

autoimmune disorders is associated with increased PARP-1 activation

(76,77). Trichloroethene exposure induces

autoimmune reactions, leading to increased apoptosis, immune

activation and the upregulation of PARP-1 expression following the

development of anti-single-stranded DNA antibodies (78). Concanavalin A (ConA) causes liver

damage via a mechanism comparable to the clinical alterations and

immunological responses observed in patients with AIH (79). In AIH model mice, the liver

exhibits widespread necrosis, marked macrophage infiltration, and

elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (80). Following ConA induction, PARP-1

levels and TNF-α production increase, which contributes to PARP-1

activation (80).

Although PARP-1 has been implicated in the

regulation of inflammation and T cell-mediated immune responses,

direct evidence for the use of PARP inhibitors in animal models of

AILD, including AIH, PBC and PSC, is currently lacking. The

ConA-induced hepatitis model has been widely employed to

investigate the immunopathogenesis of AIH, owing to its ability to

simulate CD4+ T cell-mediated hepatic injury (81). Notably, genetic ablation of PARP-2,

but not PARP-1, confers significant protection against ConA-induced

liver damage, suggesting isoform-specific roles of PARP enzymes in

immune liver injury (82).

However, the role of PARP-1 remains incompletely understood in this

context. Given the established involvement of PARP-1 in the

amplification of NF-κB-mediated proinflammatory cytokine release

and the modulation of CD4+ T cell polarization (83), it is plausible that PARP-1

inhibition may mitigate immune-driven hepatic inflammation in AIH

(84). Accordingly, future studies

utilizing pharmacological PARP-1 inhibitors such as PJ34 or

olaparib, or gene-silencing approaches in AIH models, such as the

ConA-induced hepatitis model, are warranted to determine whether

PARP-1 is a viable therapeutic target in AILD.

Liver fibrosis

Persistent liver injury, such as hepatitis, can lead

to liver fibrosis. This condition is characterized by the buildup

of extracellular matrix proteins, primarily cross-linked type I and

III collagen, which replace damaged normal tissue following

cholestatic and hepatotoxic injury. The resulting fibrous scarring

impairs the structural integrity of the liver tissue and disrupts

the homeostatic function of hepatocytes (85). Liver fibrosis may eventually

develop into cirrhosis, which is associated with high morbidity and

mortality, and increases the risk of HCC and chronic liver failure

(86).

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are non-parenchymal

cells located in the subendothelial region of the liver and are the

major mediators of liver fibrosis. A promising strategy to mitigate

the development of liver fibrosis is the induction of senescence in

activated HSCs (87). HSC

apoptosis can be accurately predicted based on changes in PARP-1

levels (88). Studies have shown

that autophagy exacerbates liver fibrosis by breaking down lipid

droplets in HSCs, thereby activating the HSCs. Conversely, the

suppression of autophagy promotes HSC death and reduces

proliferation. Elevated levels of cleaved PARP are associated with

HSC apoptosis, which can be induced by pharmacological agents such

as berberine (BBR) and carvedilol (89,90).

Specifically, BBR blocks autophagy in HSCs and downregulates

autophagy protein 5 expression, which leads to HSC death (90). In addition, PARP-1 activation is

associated with increased TGF-β expression. In activated KCs,

upregulated PARP-1 expression promotes TGF-β production, further

stimulating HSC activation (10).

HCC

Liver cancer ranks fourth in cancer-related

mortality and is the sixth most prevalent cancer worldwide, with

HCC accounting for >80% of cases (91,92).

With a yearly incidence rate of 1–6%, cirrhosis of any etiology is

the biggest risk factor for HCC. Indeed, HCC is the primary cause

of mortality in individuals with cirrhosis (93). Compared with nearby normal tissues,

HCC exhibits numerous chromosomal aberrations and elevated PARP

expression, which accumulates during DNA replication (94,95).

PARP-1 inhibition has been suggested to be an effective treatment

for HCC, particularly in BRCA-deficient tumors (94).

Emerging evidence indicates that PARP-1 enhances

glycolysis and metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells by physically

interacting with hypoxia inducible factor-1α, stabilizing it, and

acting as a transcriptional coactivator (96). This promotes the expression of

hexokinase 2 and other glycolytic enzymes, thereby reinforcing the

Warburg effect in HCC and facilitating tumor proliferation

(97). Beyond its role in DNA

repair, PARP-1 also functions as a transcriptional coregulator,

interacting with NF-κB and STAT5 to facilitate the expression of

pro-inflammatory and tumorigenic genes (98), which promotes chronic inflammation,

cell proliferation and angiogenesis in HCC. PARP-1 also modulates

the tumor immune microenvironment through multiple mechanisms. PARP

inhibition leads to the accumulation of cytosolic DNA, activation

of the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of IFN genes-type I IFN

pathway and upregulation of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1),

thereby reshaping immune cell infiltration and enhancing antitumor

immunity (99). A preclinical

study of HCC demonstrated that olaparib upregulates PD-L1 via the

suppression of microRNA-513, and its combination with

anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) therapy significantly

enhances CD8+T-cell infiltration and antitumor efficacy

(100). Broader oncology studies

indicate that PARP inhibitor plus immune checkpoint inhibitor

combinations are well-tolerated and exhibit synergistic antitumor

effects, which justifies their translational exploration in HCC

(101–103).

Caspase-3 is an effector protein in cancer cell

apoptosis, which promotes apoptosis by cleaving PARP-1 (104). Notably, HCC progression is

associated with decreased levels of both PARP-1 and cleaved

caspase-3. DNA damage repair fails when PARP-1 is cleaved, as the

cleaved form of PARP-1 can no longer repair DNA (104–106). Peptides derived from Laminaria

japonica promote apoptosis by increasing cleaved caspase-9 and

caspase-3 levels and activating PARP, potentially through upstream

apoptotic signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) phosphorylation and

subsequent p38 MAPK activation (107). Factors upstream of PARP-1, such

as JNK1/2 and ERK1/2, may also regulate cell death following PARP-1

inhibition (108). This mechanism

can kill cancer cells and provides a potential therapeutic avenue

for HCC. However, the upregulation of MET expression in HCC

presents a challenge: Oxidative DNA damage activates MET, which

interacts with and phosphorylates PARP-1 at tyrosine 907, thereby

limiting the effectiveness of PARP-1 inhibitors in HCC (109). Future studies on the use of PARP

inhibitors for the treatment HCC should account for this

mechanism.

A summary of the targets and associated molecules or

complexes of PARP-1 in liver diseases is presented in Table I.

| Table I.Targets, associated molecules and

complexes of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in liver diseases. |

Table I.

Targets, associated molecules and

complexes of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in liver diseases.

| First author/s,

year | Liver disease

type | Target, associated

molecule or complex | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Mukhopadhyay et

al, 2014 | Liver fibrosis | TGF-β | (10) |

| Zhang et al,

2016 | ALD | NF-κB | (14) |

| Liu et al,

2018 | Viral

hepatitis | lncRNA-HUR1 | (40) |

| Yin et al,

2022 | ALD | C-C chemokine

ligand type 2 | (51) |

| Ye et al,

2022 | NAFLD | NLRP3 | (57) |

| Salomone et

al, 2017 | NAFLD | SIRT1, AMPK | (60) |

| Gallyas and Sumegi,

2020 | Drug-induced liver

injury | Activator protein

1, TGF-β1 | (69) |

| Liu et al,

2023 | Autoimmune liver

disease | TNF-α | (80) |

| Ishteyaque et

al, 2024 | Hepatocellular

carcinoma | Caspase-3 | (104) |

PARP-1-mediated cellular signaling pathways

in liver disease

The onset and progression of liver diseases involve

intricate molecular pathways that are poorly understood and

associated with a poor prognosis. PARP-1 activity is both directly

or indirectly regulated by a variety of signals, rendering it a

potentially useful biomarker for detecting the onset of liver

disorders and monitoring their course. This section summarizes the

key cellular signaling pathways in which PARP-1 participates and

their contributions to the pathogenesis of various liver

disorders.

The regulation of tumor cell growth and death is

strongly influenced by lncRNAs. Numerous lncRNAs that promote the

proliferation of tumor cells also decrease their apoptosis

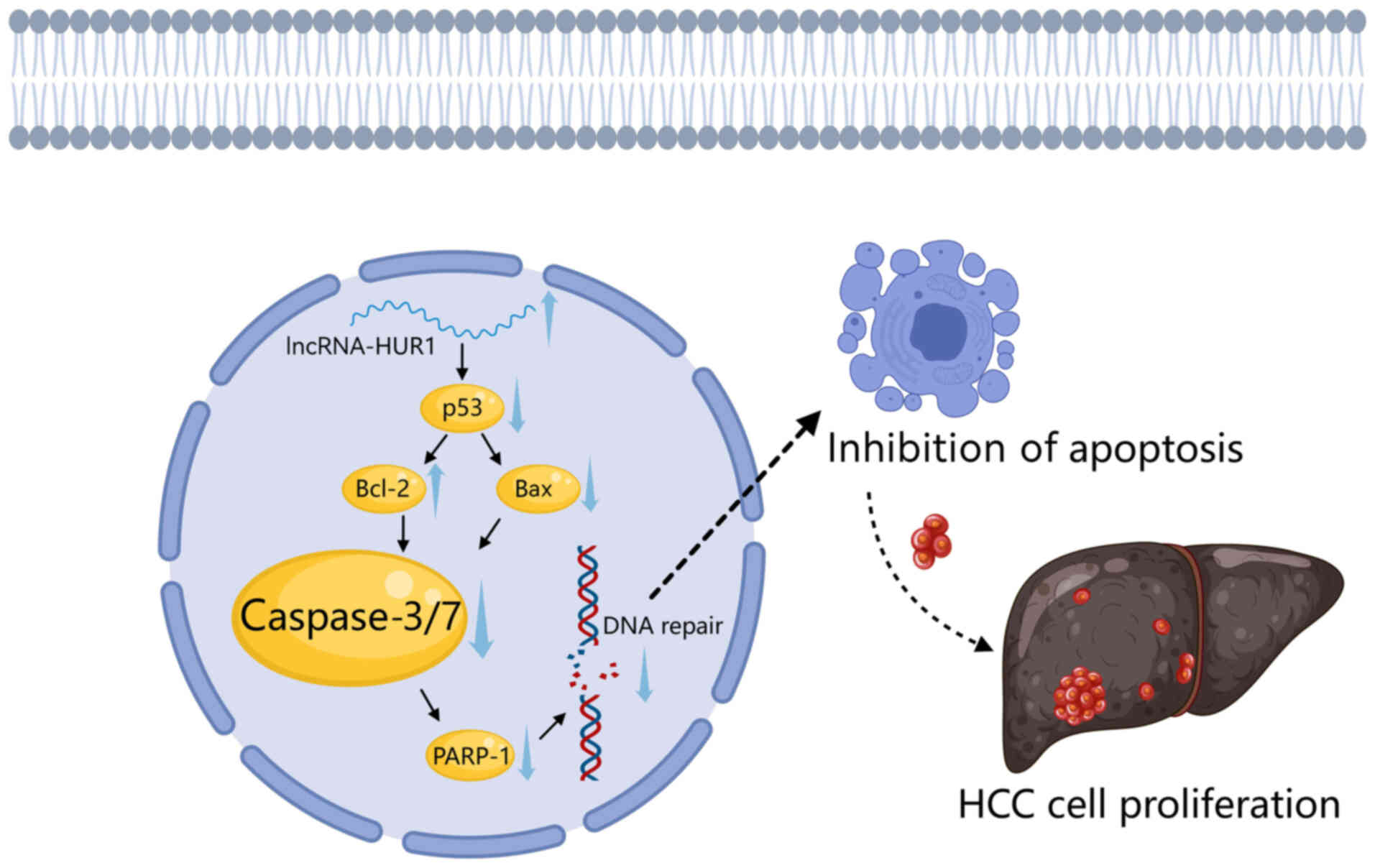

(110). For example, Chen et

al (41) reported that

lncRNA-HUR1 increases Bcl-2 expression and reduces Bax expression

by suppressing p53 activity. This inhibits caspase-3/7 activation

via the intrinsic apoptosis pathway, thereby preventing PARP-1

cleavage and cell death. Conversely, the study demonstrated that in

cell lines with stable lncRNA-HUR1 knockdown, Bcl-2 expression is

reduced, Bax expression is increased and caspase-3/7 activation is

promoted, which in turn accelerates PARP-1 cleavage and cell death

(41). Although few lncRNAs have

been thoroughly investigated in the context HCC, lncRNAs in general

have been demonstrated to be essential for the development and

progression of HCC (111),

indicating their potential as both diagnostic and therapeutic

targets (Fig. 1).

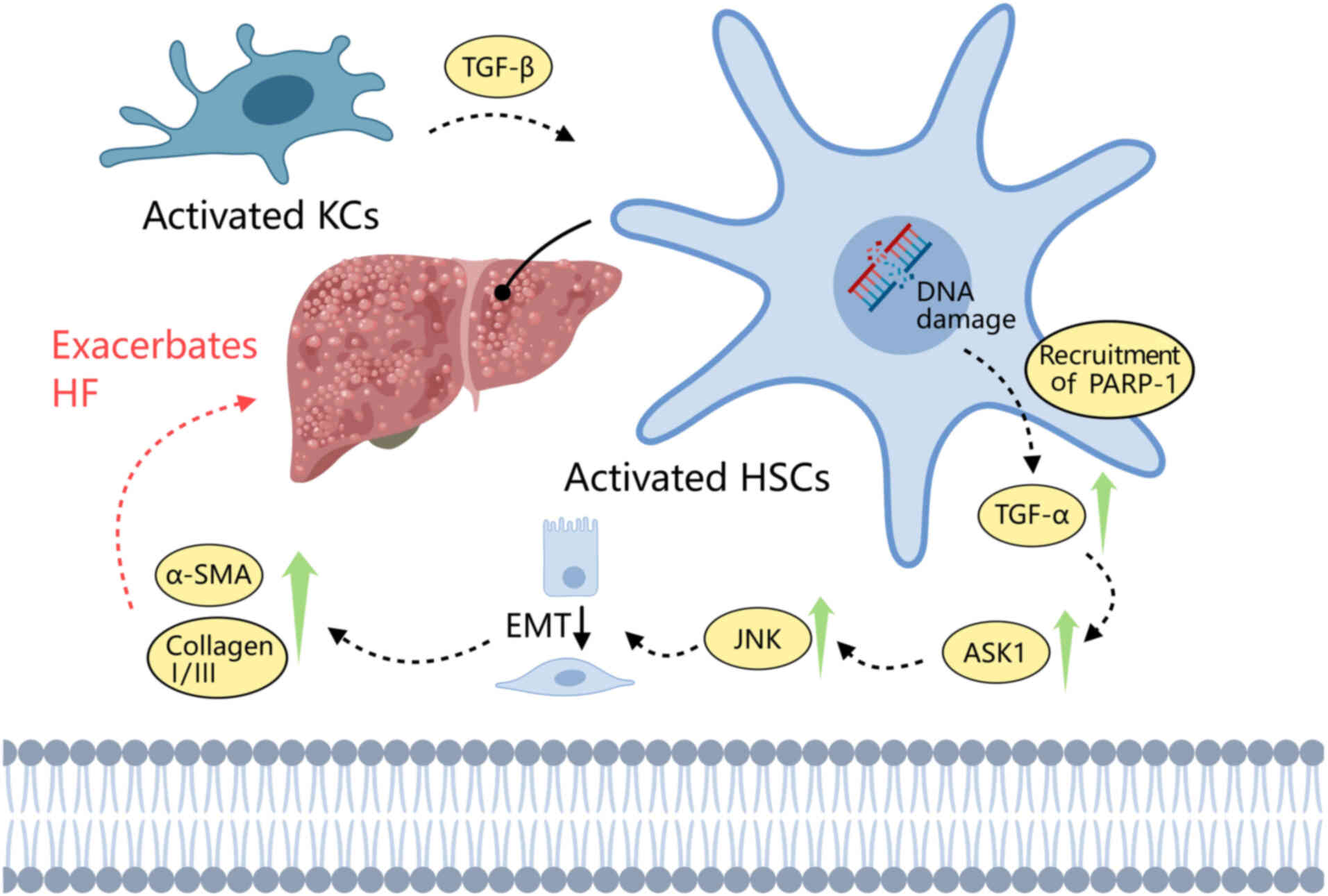

PARP-1 can sense DNA damage and trigger the

TGF-β1-Smad signaling pathway. TGF-β1 is produced by endothelial,

hematopoietic and connective tissue cells, and has been associated

with heart failure in several studies (49,112,113). A main cause of hepatic fibrosis

(HF) is the activation of HSCs. When DNA damage occurs, PARP-1 is

recruited and activates TGF-β1-Smad pathway by upregulating TNF-α

in HSCs, which increases ASK1-JNK phosphorylation. This exacerbates

HF by promoting epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and the

deposition of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and collagen I/III.

Dihydrokaempferol has been shown to decrease TNF-α transcription

and inhibit the PARP-1-regulated TGF-β1 pathway, thereby reducing

the levels of phosphorylated (p-)Smad 2/3 and p-ERK 1/2 (MAPK1).

This is associated with suppression of the ability of HSCs to

produce α-SMA and collagen I/III, contributing to the mitigation of

HF, potentially by inhibition of the downstream NF-κB and ASK1-JNK

signaling pathways (49) (Fig. 2).

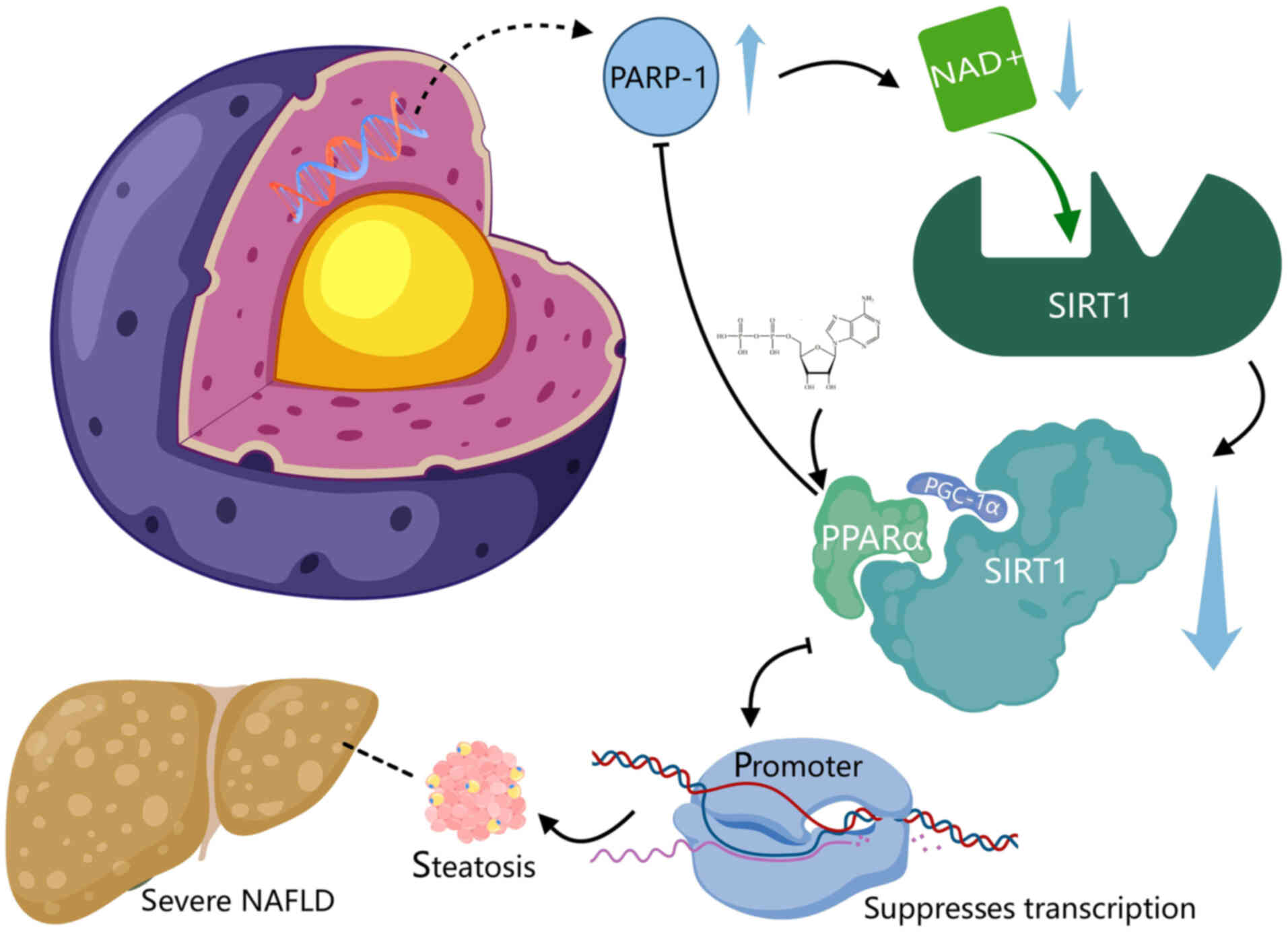

SIRT1 is an NAD+-dependent deacetylase

that plays a key role in the regulation of PPARα activity. Its

expression and activity are regulated by NAD+, which

serves as its substrate (114,115). Consequently, intracellular

NAD+ levels can directly influence PPARα signaling. In

the liver, PPARα signaling is markedly inhibited in the absence of

SIRT1. The inhibition of PARP-1 can raise intracellular

NAD+ levels, thereby increasing SIRT1 activity, and

upregulating PPARα signaling and mitochondrial oxidation. The

PARP-1-mediated poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PPARα suppresses its

transcriptional activity by preventing PPARα from binding to SIRT1

and from recruiting the PPARα/SIRT1/PPARg coactivator-1α complex to

target promoters (115). Notably,

the liver PARP activity of patients with severe NAFLD is much

greater than that of patients with simple steatosis, suggesting

that aberrant PARP-1 activation may contribute to the

downregulation of liver PPARα expression in these individuals

(115). These findings suggest

that inhibition of PARP-1 may have therapeutic potential in the

prevention and treatment of NAFLD (Fig. 3).

The accumulation of β-catenin has been observed in a

mouse model of liver cancer (116). Valanejad et al (117) identified a subset of 250-bp human

chromosomal domains, known as aggressive liver cancer domains

(ALCDs), that are located close to genes associated with various

cancer pathways and are regulated by PARP-1. Hepatoblastoma (HBL)

is a type of pediatric liver cancer that primarily affects children

<3 years old (118). Notably,

the PARP-1-ALCD axis modulates β-catenin, a potent promoter of

aggressive liver cancer, which is markedly increased in aggressive

HBL (117). PARP-1 activation can

contribute to the development of HBL by activating the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway and inducing post-translational changes in

tumor suppressor genes. Conversely, PARP-1 inhibition can decrease

cell proliferation, block Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and restore the

expression of tumor suppressor genes (119). These findings suggest that

targeting proteins associated with the Wnt/β-catenin pathway may

represent a potential therapeutic approach for liver cancer.

The PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway inhibits

apoptosis while enhancing cell survival and proliferation, and is

associated with angiogenesis, carcinogenesis, invasion, and

metastasis in several cancers, including colorectal cancer and

non-small cell lung cancer (120,121). Numerous studies have examined the

effects of natural substances on HCC, some of which target this

pathway. For example, in one study, the treatment of HepG2 cells

with 13-acetoxysarcocrassolide reduced p-PI3K, p-AKT and p-mTOR

levels, indicating suppression of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling

pathway. This inhibition decreased the mTOR-mediated

phosphorylation of p70S6K and its downstream effectors S6 and

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B, and also increased

cleaved PARP-1 levels, indicating that the induced apoptosis was

facilitated by mitochondrial dysfunction. These findings suggest

that PARP-1 activity may be associated with the phosphorylation of

AKT, which influences downstream mTOR signaling and promotes tumor

cell proliferation and apoptotic resistance (122).

Mechanistically, PARP-1 further promotes HCC growth

by forming a positive feedback loop with the PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling axis. PARP-1 activation increases the phosphorylation of

AKT at serine 473, which activates mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) targets

such as ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 and eukaroytic translation

initiator factor 4E binding protein 1, thereby driving protein

synthesis, cell proliferation and survival while inhibiting

apoptosis (123–125). Conversely, PARP-1 inhibition

downregulates AKT activity via upregulation of PH domain

leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatase 1, highlighting the direct

role of PARP-1 in the modulation of AKT/mTOR signaling (126). The activation of AKT/mTOR

signaling has been demonstrated to support the stability and

activity of PARP-1, with PARP-1 activation modulating mTORC1

through AMPK-dependent mechanisms, and AKT activation enhancing DDR

components, including PARP-1 itself (124,127). This mutual reinforcement

establishes a negative feedback loop of pro-survival signaling and

genomic maintenance that promotes HCC progression and therapy

resistance. Preclinical studies indicate that disrupting either

PARP-1 or the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway can disrupt this feedback loop,

reduce tumor viability, and sensitize cells to treatment (125,126,128).

These findings indicate that PARP-1 regulates

several cellular signaling pathways and is crucial for the onset,

progression and clinical signs of several liver diseases. This

suggests the potential of PARP-1 as a prognostic indicator and

possible target for liver disease therapy.

Potential clinical value of PARP-1 in liver

disease

In emerging nations, particularly in the

Asia-Pacific region, liver diseases are becoming widely

acknowledged as major health concerns. While viral hepatitis

remains the primary cause of morbidity and death, ALD and NAFLD are

contributing to the liver disease burden at an accelerating rate

(129).

PARP-1 expression in upregulated in numerous

cancers, and prompt evaluation of its expression is important when

devising a treatment plan and monitoring therapeutic effectiveness.

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging is an efficient,

noninvasive, real-time technique that can be used to assess PARP-1

activity throughout the body. In 2016, researchers conducted

preclinical evaluations and the first-in-human study of PARP

activity in cancer. Notably, the study observed increased uptake of

18F fluorthanatrace (18F-FTT) in a patient

with HCC (130). However,

investigations of PARP-targeted imaging in liver diseases,

including NASH, ALD and HCC, remain at the preclinical stage

(131), including a study of

PARP-targeted PET imaging in NASH animal models (132). Clinical trials of PARP-1 PET

probes such as 18F-FTT have so far been limited to other

tumor types, including breast, ovarian and prostate cancer

(133), with no direct

applications in liver pathology. This highlights a critical gap and

opportunity for the future clinical translation of PARP-1 in liver

diseases.

A number of tracers targeting PARP-1 have been

developed, including 18F-FTT and the olaparib analog

18F-PARPi. Patients with elevated PARP-1 expression can

be identified by PET imaging using 18F-FTT (134). A recent study designed a

high-affinity PARP-1 molecule, 18F-BIBD-300, by chemical

modification of the main pharmacophore of 18F-FTT. Since

18F-FTT has been used to diagnose liver

cancer,18F-BIBD-300 has been suggested to have potential

for this purpose (135).

18F-PARPi and 18F-FTT both undergo

hepatobiliary clearance, which may limit their effectiveness in the

imaging of abdominal lesions, such as liver metastases (136). 18F-FPyPARP, a

6-fluoronicotinoyl analog of 18F-PARPi, has been found

to be an excellent radioactive tracer for PARP expression that is

simpler to manufacture and less lipophilic than

18F-PARPi (136).

PARP inhibitors have emerged as leading cancer

treatments for BRCA-deficient patients with ovarian and breast

cancers (137). Notably, although

all PARP-1 drugs are classified as PARP inhibitors, not all PARP

inhibitors are selective for PARP-1. Thus, PARP-1 inhibitors

constitute a distinct subgroup within the broader category of PARP

inhibitors. The clinical utility of PARP inhibitors may be

attributed to their ability to efficiently kill cells with HRD in

BRCA1/2-deficient cancers by driving the accumulation of unrepaired

DNA damage and inducing synthetic lethality (138).

Common adverse reactions reported in cancer trials

of various PARP inhibitors, including olaparib and niraparib,

include anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, nausea, vomiting and

fatigue (139,140). While these adverse reactions have

been observed in patients with cancer, patients with liver disease

often have cytopenias, such as thrombocytopenia due to cirrhosis

(141); therefore, PARP

inhibitors may exacerbate hematological complications that are

already present. Nausea and vomiting are also common symptoms of

PARP inhibitors, occurring in >20% of patients, which may

exacerbate malnutrition in patients with advanced liver disease

(142). In addition, niraparib

has been associated with nephrotoxicity; impaired hepatic albumin

synthesis, such as that occurring in cirrhosis, may increase free

drug concentrations, thereby exacerbating nephrotoxicity (143,144).

Evidence for the efficacy of PARP-1 inhibitors in

liver diseases, including NAFLD/NASH, ALD, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis

and HCC, comes primarily from cell and animal models. For example,

one study demonstrated that PARP-1 inhibition contributed to the

antifibrotic effect of puerarin in mice (145), suggesting that targeting PARP-1

has therapeutic potential for liver fibrosis. Another study used

mouse models of NASH to verify that PARP inhibition and PARP-1

deletion reduce hepatic triglyceride accumulation, metabolic

disorders, inflammation and/or fibrosis (146), indicating that PARP inhibition

may be a promising treatment strategy for fatty hepatitis. Limited

data from patients are also available: A pilot study using liver

samples from patients with NAFLD confirmed that PARP-1 is activated

in human fatty liver, as well as in a HFD-induced mouse model

(61). In addition, a study at the

University of Minnesota analyzed liver tissue samples from patients

with alcoholic and HBV-related cirrhosis (stage 3–4 fibrosis). The

results of the study demonstrated the key pathogenic role of PARP-1

in liver fibrosis and the potential of PARP-1 inhibitors to restore

liver function after fibrosis (10). Collectively, these studies suggest

that repurposing PARP-1 inhibitors to treat liver diseases

associated with injury, inflammation and fibrosis may have

potential clinical applicability.

PARP-1 inhibitor monotherapy appears to be largely

ineffective in HCC, likely due to the BRCA nature of this cancer

type. However, one study investigated non-BRCA1/2 gene

abnormalities, and found that they confer sensitivities to PARP

inhibition comparable to those observed with BRCA1/2 mutations

(147). In addition, marked

suppression of HCC cell growth was observed both in vitro

and in vivo following treatment with a combination of

wild-type p53-induced protein phosphatase 1 and PARP inhibitors

(138). Synergistic strategies

comprising PARP inhibitors and radiotherapy have also been shown to

improve HCC management, with olaparib increasing the

radiosensitivity of HCC cells by promoting extensive DSBs (148). In addition, dual inhibition of

PARP-1/2 and tankyrase 1/2 exhibited potent anticancer activity

with strong synergy, suggesting an expanded therapeutic scope for

PARP-1 inhibitors (149).

Likewise, both ALD and NAFLD may be prevented by

blocking PARP-1. Since NAD+ plays a crucial role in

acute alcoholic liver injury, preserving NAD+ levels by

blocking PARP may help to maintain liver homeostasis (12). In addition, the pharmacological

inhibition or genetic deletion of PARP-1 has been shown to protect

against ethanol-induced hepatocyte damage and increased fatty acid

oxidation, thereby preventing fatty liver development in a rat

model of NAFLD (19).

Despite the encouraging results obtained for PARP-1

inhibitors in preclinical studies, several obstacles remain in the

translation of these discoveries into successful clinical

applications. A major issue is the intrinsic disparity between

animal or in vitro systems and the intricate pathophysiology

of human disease. Preclinical models cannot accurately replicate

the tumor microenvironment, genetic diversity or immune responses

observed in patients. In addition, drug metabolism and

pharmacokinetics differ significantly across species, resulting in

variations in efficacy and toxicity profiles. Another major barrier

is the development of resistance mechanisms in patients, which are

not always predictable from preclinical data (150). Collectively, these factors

contribute to the frequent failure of preclinically promising drugs

in clinical trials and highlight the requirement for improved

prediction models and biomarkers. Nevertheless, PARP-1 inhibition

remains a promising treatment strategy for various liver diseases,

if these translational challenges can be addressed.

Future expectations

As research has progressed, understanding of the

role of PARP-1 in liver disorders has advanced. Studies have shown

that conditions such as ALD (52),

liver cirrhosis (88) and HCC

(94,95) are associated with elevated PARP-1

levels, and that reducing PARP-1 expression and/or activity in

hepatocytes can alleviate these disorders. This section of the

review examines future directions for PARP-1 research by

integrating the latest findings from both medical and and

pharmaceutical perspectives.

PARP-1 inhibitors are commonly used to treat

malignancies, such as breast and ovarian cancers, with BRCA1/2

mutations (151). However, these

inhibitors have limited effectiveness in individuals who develop

resistance to PARP-1 inhibitors and in other malignancies, such as

HCC (152). Therefore, clinical

development has focused on overcoming PARP-1 inhibitor

resistance.

First, PARP-1 inhibitors can be combined with other

DNA damage repair inhibitors. Resistance to PARP inhibitors is

often not due to target protein mutations, but arises from the

ability of tumor cells to change their DNA damage repair pathways

(153). In addition to PARP-1,

several other proteins participate in DNA damage repair. For

example, DSBs recruit ATM proteins, which mediate checkpoint

signaling and DNA repair (154).

Replication stress activates ATM and Rad3-related (ATR), which

stabilize and restart replication forks, with checkpoint kinases 1

and 2 acting downstream of ATR and ATM (155). The effectiveness of DDR

inhibitors as monotherapies depends on their specific biological

activity, and combining inhibitors may be a beneficial therapeutic

approach when complementary pathways are targeted (156).

Secondly, PARP-1 inhibitors can be combined with

immune checkpoint inhibitors. PD-1, PD-L1 and cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 are the most studied

immunological checkpoints. Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting

these molecules exert antitumor effects by stimulating the tumor

immune response (157). Treatment

with a combination of PARP and immune checkpoint inhibitors has

been shown to exhibit higher antitumor efficacy than monotherapy.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are able to sensitize tumor cells to

PARP inhibitors, which represents a promising therapeutic approach

(158).

A recent study identified numerous novel liver

cancer susceptibility genes and characterized the landscape of rare

genetic variants of liver cancer in a Chinese population. These

variants were found to be strongly associated with the risk of

liver cancer. Notably, the nuclear RNAi-defective 2 (NRDE2) gene

was shown to enhance the assembly and activity of the casein kinase

2 complex, thereby promoting the phosphorylation of mediator of DNA

damage checkpoint protein 1, initiating the HR repair pathway for

DNA DSB repair, and ultimately inhibiting the development of liver

cancer. NRDE2 may be a potential synthetic lethal target as rare

genetic mutations that impair its HR repair function markedly

increase the susceptibility of HCC to PARP-1 inhibitors. Overall,

the study demonstrated that NRDE2 is a regulatory component that

suppresses HCC and facilitates DNA damage repair, and that its

deficiency in HCC cells results in greater susceptibility to PARP-1

inhibitors (159). This study

identified NRDE2 as a potential biomarker for the treatment of HCC

with PARP-1 inhibitors. However, further studies are necessary to

determine whether NRDE2 deficiency could be used as a biomarker for

PARP-1 inhibitor response in other cancer types or if the loss of

other genes may have an impact comparable to that of NRDE2

(158).

Conclusions

PARP-1 plays a crucial role in liver disease by

managing responses to DNA damage, inflammation, apoptosis and

metabolic balance. When PARP-1 is dysregulated, it significantly

contributes to the progression of conditions such as NAFLD, ALD,

viral hepatitis, autoimmune liver diseases, hepatic fibrosis and

the serious development of HCC. Research has shown that inhibiting

PARP-1 can help reduce liver cell injury, decrease inflammation and

fibrosis, and enhance antitumor immunity, highlighting its

potential as a therapeutic target. Additionally, combining PARP-1

inhibitors with immune checkpoint blockers or agents that target

DNA repair may improve treatment effectiveness. Future research

should focus on the specific roles of different PARP-1 isoforms,

the mechanisms behind treatment resistance and how to apply these

findings in clinical settings. Overall, PARP-1 represents a

promising target for both treatment and diagnosis, with the

potential to improve outcomes for various liver diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Research Project

of Anhui Educational Committee (grant no. 2024AH050702) and the

Anhui Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation

Research Project (grant no. 2024CCCX288).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

KH, HT and SC wrote the manuscript. YL and RW

created the figures and table. YJ and BC supervised the research,

revised the manuscript, obtained financial support, conceptualized

the review and performed the literature search. All authors read

and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Neshat SY, Quiroz VM, Wang Y, Tamayo S and

Doloff JC: Liver Disease: induction, progression, immunological

mechanisms, and therapeutic interventions. Int J Mol Sci.

22:67772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Devarbhavi H, Asrani SK, Arab JP, Nartey

YA, Pose E and Kamath PS: Global burden of liver disease: 2023

Update. J Hepatol. 79:516–537. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xiao J, Wang F, Wong NK, He J, Zhang R,

Sun R, Xu Y, Liu Y, Li W, Koike K, et al: Global liver disease

burdens and research trends: Analysis from a Chinese perspective. J

Hepatol. 71:212–221. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Younossi ZM, Loomba R, Rinella ME,

Bugianesi E, Marchesini G, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Serfaty L, Negro

F, Caldwell SH, Ratziu V, et al: Current and future therapeutic

regimens for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 68:361–371. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Alvarado-Tapias E, Pose E, Gratacós-Ginès

J, Clemente-Sánchez A, López-Pelayo H and Bataller R:

Alcohol-associated liver disease: Natural history, management and

novel targeted therapies. Clin Mol Hepatol. 31 (Suppl 1):S112–S133.

2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Llovet JM, De Baere T, Kulik L, Haber PK,

Greten TF, Meyer T and Lencioni R: Locoregional therapies in the

era of molecular and immune treatments for hepatocellular

carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 18:293–313. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ishikawa T: Efficacy and features of

balloon-occluded transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular

carcinoma: A narrative review. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol.

9:482024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pandey N and Black BE: Rapid detection and

signaling of DNA damage by PARP-1. Trends Biochem Sci. 46:744–757.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Galindo-Campos MA, Bedora-Faure M, Farrés

J, Lescale C, Moreno-Lama L, Martínez C, Martín-Caballero J,

Ampurdanés C, Aparicio P, Dantzer F, et al: Coordinated signals

from the DNA repair enzymes PARP-1 and PARP-2 promotes B-cell

development and function. Cell Death Differ. 26:2667–2681. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Cao Z, Horváth

B, Park O, Wang H, Erdelyi K, Holovac E, Wang Y, Liaudet L, et al:

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 is a key mediator of liver

inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology. 59:1998–2009. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Xu XL, Xing BC, Han HB, Zhao W, Hu MH, Xu

ZL, Li JY, Xie Y, Gu J, Wang Y and Zhang ZQ: The properties of

tumor-initiating cells from a hepatocellular carcinoma patient's

primary and recurrent tumor. Carcinogenesis. 31:167–174. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gariani K, Ryu D, Menzies KJ, Yi HS, Stein

S, Zhang H, Perino A, Lemos V, Katsyuba E, Jha P, et al: Inhibiting

poly ADP-ribosylation increases fatty acid oxidation and protects

against fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 66:132–141. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Guillot C, Hall J, Herceg Z, Merle P and

Chemin I: Update on hepatocellular carcinoma breakthroughs:

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors as a promising therapeutic

strategy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 38:137–142. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang Y, Wang C, Tian Y, Zhang F, Xu W, Li

X, Shu Z, Wang Y, Huang K and Huang D: Inhibition of

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 protects chronic alcoholic liver

injury. Am J Pathol. 186:3117–3130. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hardy T and Mann DA: Epigenetics in liver

disease: From biology to therapeutics. Gut. 65:1895–1905. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cheng ML, Nakib D, Perciani CT and

MacParland SA: The immune niche of the liver. Clin Sci (Lond).

135:2445–2466. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Piano S, Bunchorntavakul C, Marciano S and

Rajender Reddy K: Infections in cirrhosis. Lancet Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 9:745–757. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kubes P and Jenne C: Immune responses in

the liver. Annu Rev Immunol. 36:247–277. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Mukhopadhyay P, Horváth B, Rajesh M, Varga

ZV, Gariani K, Ryu D, Cao Z, Holovac E, Park O, Zhou Z, et al: PARP

inhibition protects against alcoholic and non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 66:589–600. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

De Siervi S, Cannito S and Turato C:

Chronic liver disease: latest research in pathogenesis, detection

and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 24:106332023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Santinelli-Pestana DV, Aikawa E, Singh SA

and Aikawa M: PARPs and ADP-ribosylation in chronic inflammation: A

focus on macrophages. Pathogens. 12:9642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Vida A, Márton J, Mikó E and Bai P:

Metabolic roles of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. Semin Cell Dev

Biol. 63:135–143. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Li WH, Wang F, Song GY, Yu QH, Du RP and

Xu P: PARP-1: A critical regulator in radioprotection and

radiotherapy-mechanisms, challenges, and therapeutic opportunities.

Front Pharmacol. 14:11989482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Szántó M, Gupte R, Kraus WL, Pacher P and

Bai P: PARPs in lipid metabolism and related diseases. Prog Lipid

Res. 84:1011172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Demin AA, Hirota K, Tsuda M, Adamowicz M,

Hailstone R, Brazina J, Gittens W, Kalasova I, Shao Z, Zha S, et

al: XRCC1 prevents toxic PARP1 trapping during DNA base excision

repair. Mol Cell. 81:3018–3030.e5. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ogawa K, Masutani M, Kato K, Tang M,

Kamada N, Suzuki H, Nakagama H, Sugimura T and Shirai T: Parp-1

deficiency does not enhance liver carcinogenesis induced by

2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline in mice. Cancer Lett.

236:32–38. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liao Y, Wang X, Ran G, Zhang S, Wu C, Tan

R, Liu Y, He Y, Liu T, Wu Z, et al: DNA damage and up-regulation of

PARP-1 induced by columbin in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol Lett.

379:20–34. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cantó C, Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Youn

DY, Oosterveer MH, Cen Y, Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Yamamoto H, Andreux

PA, Cettour-Rose P, et al: The NAD(+) precursor nicotinamide

riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against

high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 15:838–847. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Wu AY, Sekar P, Huang DY, Hsu SH, Chan CM

and Lin WW: Spatiotemporal roles of AMPK in PARP-1- and

autophagy-dependent retinal pigment epithelial cell death caused by

UVA. J Biomed Sci. 30:912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ju C, Liu C, Yan S, Wang Y, Mao X, Liang M

and Huang K: Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase-1 is required for

hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration in mice. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 511:531–535. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Yimlamai D, Christodoulou C, Galli GG,

Yanger K, Pepe-Mooney B, Gurung B, Shrestha K, Cahan P, Stanger BZ

and Camargo FD: Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate.

Cell. 157:1324–1338. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cover C, Fickert P, Knight TR,

Fuchsbichler A, Farhood A, Trauner M and Jaeschke H:

Pathophysiological role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)

activation during acetaminophen-induced liver cell necrosis in

mice. Toxicol Sci. 84:201–208. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Andronikou C and Rottenberg S: Studying

PAR-dependent chromatin remodeling to tackle PARPi resistance.

Trends Mol Med. 27:630–642. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Pazzaglia S and Pioli C: Multifaceted role

of PARP-1 in DNA repair and inflammation: Pathological and

therapeutic implications in cancer and non-cancer diseases. Cells.

9:412019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Llaneras J, Riveiro-Barciela M,

Rando-Segura A, Marcos-Fosch C, Roade L, Velázquez F,

Rodríguez-Frías F, Esteban R and Buti M: Etiologies and features of

acute viral hepatitis in Spain. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

19:1030–1037. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Cooke GS, Flower B, Cunningham E, Marshall

AD, Lazarus JV, Palayew A, Jia J, Aggarwal R, Al-Mahtab M, Tanaka

Y, et al: Progress towards elimination of viral hepatitis: A lancet

gastroenterology and hepatology commission update. Lancet

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9:346–365. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yeh SH, Li CL, Lin YY, Ho MC, Wang YC,

Tseng ST and Chen PJ: Hepatitis B virus DNA integration drives

carcinogenesis and provides a new biomarker for HBV-related HCC.

Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 15:921–929. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Funato K, Otsuka M, Sekiba K, Miyakawa Y,

Seimiya T, Shibata C, Kishikawa T and Fujishiro M: Hepatitis B

virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma with Smc5/6 complex

deficiency is susceptible to PARP inhibitors. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 607:89–95. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhou L, Liu CH, Lv D, Sample KM, Rojas Á,

Zhang Y, Qiu H, He L, Zheng L, Chen L, et al: Halting

hepatocellular carcinoma: Identifying intercellular crosstalk in

HBV-driven disease. Cell Rep. 44:1154572025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu N, Liu Q, Yang X, Zhang F, Li X, Ma Y,

Guan F, Zhao X, Li Z, Zhang L and Ye X: Hepatitis B

virus-upregulated LNC-HUR1 promotes cell proliferation and

tumorigenesis by blocking p53 activity. Hepatology. 68:2130–2144.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chen Y, Wen J, Qi D, Tong X, Liu N and Ye

X: HBV-upregulated Lnc-HUR1 inhibits the apoptosis of liver cancer

cells. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 38:3501–3514. 2022.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Machida K, Tsukamoto H, Mkrtchyan H, Duan

L, Dynnyk A, Liu HM, Asahina K, Govindarajan S, Ray R, Ou JH, et

al: Toll-like receptor 4 mediates synergism between alcohol and HCV

in hepatic oncogenesis involving stem cell marker Nanog. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 106:1548–1553. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Pal S, Polyak SJ, Bano N, Qiu WC,

Carithers RL, Shuhart M, Gretch DR and Das A: Hepatitis C virus

induces oxidative stress, DNA damage and modulates the DNA repair

enzyme NEIL1. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 25:627–634. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Smirnova OA, Ivanova ON, Mukhtarov F,

Valuev-Elliston VT, Fedulov AP, Rubtsov PM, Zakirova NF, Kochetkov

SN, Bartosch B and Ivanov AV: Hepatitis Delta virus antigens

trigger oxidative stress, activate antioxidant Nrf2/ARE pathway,

and induce unfolded protein response. Antioxidants (Basel).

12:9742023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bajaj JS: Alcohol, liver disease and the

gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16:235–246. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Contreras-Zentella ML, Villalobos-García D

and Hernández-Muñoz R: Ethanol metabolism in the liver, the

induction of oxidant stress, and the antioxidant defense system.

Antioxidants (Basel). 11:12582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Y, Luo W and Wang Y: PARP-1 and its

associated nucleases in DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst).

81:1026512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Langelier MF and Pascal JM: PARP-1

mechanism for coupling DNA damage detection to poly(ADP-ribose)

synthesis. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 23:134–143. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Huang H, Wei S, Wu X, Zhang M, Zhou B,

Huang D and Dong W: Dihydrokaempferol attenuates

CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis by inhibiting PARP-1 to

affect multiple downstream pathways and cytokines. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 464:1164382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ma XY, Zhang M, Fang G, Cheng CJ, Wang MK,

Han YM, Hou XT, Hao EW, Hou YY and Bai G: Ursolic acid reduces

hepatocellular apoptosis and alleviates alcohol-induced liver

injury via irreversible inhibition of CASP3 in vivo. Acta Pharmacol

Sin. 42:1101–1110. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Yin F, Wu MM, Wei XL, Ren RX, Liu MH, Chen

CQ, Yang L, Xie RQ, Jiang SY, Wang XF and Wang H: Hepatic NCoR1

deletion exacerbates alcohol-induced liver injury in mice by

promoting CCL2-mediated monocyte-derived macrophage infiltration.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 43:2351–2361. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ambade A, Lowe P, Kodys K, Catalano D,

Gyongyosi B, Cho Y, Iracheta-Vellve A, Adejumo A, Saha B, Calenda

C, et al: Pharmacological inhibition of CCR2/5 signaling prevents

and reverses alcohol-induced liver damage, steatosis, and

inflammation in mice. Hepatology. 69:1105–1121. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Wang XJ and Malhi H: Nonalcoholic fatty

liver disease. Ann Intern Med. 169:ITC65–ITC80. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Guo X, Yin X, Liu Z and Wang J:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathogenesis and natural

products for prevention and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 23:154892022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Harrison SA, Allen AM, Dubourg J,

Noureddin M and Alkhouri N: Challenges and opportunities in NASH

drug development. Nat Med. 29:562–573. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Saiman Y, Duarte-Rojo A and Rinella ME:

Fatty liver disease: Diagnosis and stratification. Annu Rev Med.

73:529–544. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ye H, Ma S, Qiu Z, Huang S, Deng G, Li Y,

Xu S, Yang M, Shi H, Wu C, et al: Poria cocos polysaccharides

rescue pyroptosis-driven gut vascular barrier disruption in order

to alleviates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Ethnopharmacol.

296:1154572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yang JH, Byeon EH, Kang D, Hong SG, Yang

J, Kim DR, Yun SP, Park SW, Kim HJ, Huh JW, et al: Fermented

soybean paste attenuates biogenic amine-induced liver damage in

obese mice. Cells. 12:8222023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Guo R, Li Y, Song Q, Huang R, Ge X, Nieto

N, Jiang Y and Song Z: Increasing cellular NAD+ protects

hepatocytes against palmitate-induced lipotoxicity by preventing

PARP-1 inhibition and the mTORC1-p300 pathway activation. Am J

Physiol Cell Physiol. 328:C776–C790. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Salomone F, Barbagallo I, Godos J, Lembo

V, Currenti W, Cinà D, Avola R, D'Orazio N, Morisco F, Galvano F

and Li Volti G: Silibinin restores NAD+ levels and

induces the SIRT1/AMPK pathway in non-alcoholic fatty liver.

Nutrients. 9:10862017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Huang K, Du M, Tan X, Yang L, Li X, Jiang

Y, Wang C, Zhang F, Zhu F, Cheng M, et al: PARP1-mediated PPARα

poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation suppresses fatty acid oxidation in

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 66:962–977. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Majeed Y, Halabi N, Madani AY, Engelke R,

Bhagwat AM, Abdesselem H, Agha MV, Vakayil M, Courjaret R, Goswami

N, et al: SIRT1 promotes lipid metabolism and mitochondrial

biogenesis in adipocytes and coordinates adipogenesis by targeting

key enzymatic pathways. Sci Rep. 11:81772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Ding RB, Bao J and Deng CX: Emerging roles

of SIRT1 in fatty liver diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 13:852–867. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ray K: Developing a toolbox for

drug-induced liver injury. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

17:7142020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Kumachev A and Wu PE: Drug-induced liver

injury. CMAJ. 193:E3102021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Björnsson HK and Björnsson ES:

Drug-induced liver injury: Pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical

features, and practical management. Eur J Intern Med. 97:26–31.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver, . EASL clinical practice guidelines: Drug-induced liver

injury. J Hepatol. 70:1222–1261. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Li X, Tang J and Mao Y: Incidence and risk

factors of drug-induced liver injury. Liver Int. 42:1999–2014.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Gallyas F Jr and Sumegi B: Mitochondrial

protection by PARP inhibition. Int J Mol Sci. 21:27672020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Wang C, Xu W, Zhang Y, Huang D and Huang

K: Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ated PXR is a critical regulator of

acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 9:8192018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Su Q, Kuang W, Hao W, Liang J, Wu L, Tang

C, Wang Y and Liu T: Antituberculosis drugs (rifampicin and

isoniazid) induce liver injury by regulating NLRP3 inflammasomes.

Mediators Inflamm. 2021:80862532021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Carbone M and Neuberger JM: Autoimmune

liver disease, autoimmunity and liver transplantation. J Hepatol.

60:210–223. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Trivedi PJ, Hirschfield GM, Adams DH and

Vierling JM: Immunopathogenesis of primary biliary cholangitis,

primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis: Themes and

concepts. Gastroenterology. 166:995–1019. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Yilmaz K, Haeberle S, Kim YO, Fritzler MJ,

Weng SY, Goeppert B, Raker VK, Steinbrink K, Schuppan D, Enk A and

Hadaschik EN: Regulatory T-cell deficiency leads to features of

autoimmune liver disease overlap syndrome in scurfy mice. Front

Immunol. 14:12536492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Heo NY and Kim H: Epidemiology and updated

management for autoimmune liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol.

29:194–196. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Zhang Y, Pötter S, Chen CW, Liang R, Gelse

K, Ludolph I, Horch RE, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JHW and Dees

C: Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 regulates fibroblast activation in

systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 77:744–751. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Su X, Ye L, Chen X, Zhang H, Zhou Y, Ding

X, Chen D, Lin Q and Chen C: MiR-199-3p promotes ERK-mediated IL-10

production by targeting poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in patients

with systemic lupus erythematosus. Chem Biol Interact. 306:110–116.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Wang G, Ma H, Wang J and Khan MF:

Contribution of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 activation and

apoptosis in trichloroethene-mediated autoimmunity. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 362:28–34. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Hao J, Sun W and Xu H: Pathogenesis of

concanavalin A induced autoimmune hepatitis in mice. Int

Immunopharmacol. 102:1084112022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Liu Q, Yang H, Kang X, Tian H, Kang Y, Li