Introduction

At present, cancer ranks as either the first or

second leading cause of premature mortality among most populations

worldwide, and the global number of individuals affected by cancer

is expected to continue to rise in the years ahead (1). Cancer is a complex disorder with

multiple contributing factors and developmental stages, involving

processes such as the activation of proto-oncogenes and the

inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. Despite the current

advancements in comprehensive cancer treatment, the complex

pathogenesis of the disease still merits in-depth exploration to

provide a novel direction for personalized cancer therapy (2). Proteins, such as organic

macromolecules, are not only the fundamental organic matter

constituting cells and the material basis of life, but are also

associated with life phenomena (such as maintaining cell survival,

proliferation, differentiation and homeostasis, and activating and

regulating intracellular signaling pathways and material metabolic

balance). Notably, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is

responsible for catalyzing the repair and degradation of a large

number of key protein substrates. Dysregulation of the UPS may thus

be implicated in the onset and progression of numerous diseases,

including cancer. During the process of ubiquitination, three

enzymes are essential for attaching ubiquitin proteins to their

target proteins: i) Ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1); ii)

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2); and iii) ubiquitin ligase (E3)

(3–5). Specifically, E3 binds to the

substrate protein, and this interaction ultimately results in the

degradation of the substrate through the 26S proteasome (3). Research has shown that the modulation

of E3 activity constitutes one of the key factors influencing the

development and progression of cancer (4). Among the various types of E3 ligases,

Cullin-RING ligases (CRL) are the ones with the largest number of

members and the most diverse types, and they play a role in cancer

development (5,6). One of these CRL1 ligases, also

referred to as the S-phase kinase-associated protein 1

(SKP1)/Cullin 1 (CUL1)/F-box protein (FBP) complex (SCF complex),

has been extensively investigated (7–9). A

total of 80–90% of proteins within cells undergo degradation via

the UPS (2). The SCF complex

consists of three invariant core components and variable FBPs.

RING-box 1 is responsible for the recruitment of E2; CUL1, a

scaffolding protein, also serves as the catalytic core; and SKP1

links the SCF complex to variable FBPs and their corresponding

target proteins to recruit substrates for ubiquitination (9). To date, 69 FBPs have been identified

in humans. These proteins can be further categorized into the

following three groups: i) Those containing leucine-rich repeats

(FBXL); ii) those with WD-40 repeats (FBXW); and iii) those

featuring only uncharacterized structural domains (FBXO) (10,11).

A growing body of evidence indicates that abnormal expression of

FBPs is linked to the occurrence, proliferation, angiogenesis and

metastasis of various malignant tumors. For instance, FABP5 can

alter the fatty acid metabolism pathways and products of tumor

cells, providing them with more energy and nutritional support,

thereby promoting the growth and spread of tumors (12). FABP4 is induced in endothelial

cells by the NOTCH1 signaling pathway and plays a significant role

in the formation of the tumor vascular system. In in situ mouse

ovarian tumor models, FABP4 is essential for angiogenesis and is an

important target in tumor angiogenesis, especially in tumors of

low-grade, interstitial and free fatty acid-rich tissues (13). Within the FBP family, F-box protein

2 (FBXO2) is abnormally expressed in multiple types of cancer. It

shows abnormal expression in various cancers, such as gastric

cancer (GC) (14), colorectal

cancer (CRC) (15), ovarian cancer

(OV) (16), endometrial cancer

(EC) (17), osteosarcoma (OS)

(18), glioblastoma (GB) (19), papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC)

(20) and oral squamous cell

carcinoma (OSCC) (21).

Specifically, it regulates EMT, mediates substrate degradation

through the UPS, activates related signaling pathways (such as

STAT3, PI3K-Akt), affects cell cycle and autophagy, thereby

promoting the malignant processes of corresponding cancers such as

cell proliferation, migration and invasion, and chemotherapy

resistance. Furthermore, its expression level is often associated

with clinical features such as cancer prognosis and metastasis

(14–21).

Composition and role of the UPS

It is widely acknowledged that protein homeostasis

is essential for maintaining normal cellular physiological

activities, among which the timely degradation or repair of

misfolded proteins is particularly crucial (22,23).

The degradation pathways mainly encompass autophagy (such as

lysosomal degradation pathway) and the UPS (24). The relationship between ubiquitin

and protein regulation was initially investigated by Hershko et

al (25) in the 1980s.

Subsequently, to gain a deeper understanding of ubiquitin and its

associated protein hydrolysis, Hershko et al (22) elaborated on ubiquitinating enzymes

further. This allowed the clarification of the biological

characteristics of the UPS, highlighting its essential role in

protein degradation, as well as its specific physiological

functions (including roles in the cell cycle, DNA repair, protein

synthesis, transcription and stress responses). The UPS selective

basis (such as short-term signals involved in protein-specific

degradation) and key mechanistic traits such as polyubiquitin

chains and the subunit selectivity of protein degradation were also

identified. These findings triggered a substantial expansion of

research in the ubiquitin field during the 1990s (26,27).

The UPS acts as a major system for the intracellular non-lysosomal

degradation of proteins, and regulates and eliminates aberrant

proteins in a highly specific manner. The UPS has been demonstrated

to be aberrantly activated in a variety of biologically notable

processes, including cell viability, proliferation and invasion,

colonization and metastasis, recurrence, vascular invasion,

immunomodulation, and chemotherapy resistance, in a wide range of

cancer types (28,29). In OV, the UPS is abnormally

activated (16). On one hand, it

promotes cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis through the

SOX6-FBXO2-Sad1 and UNC84 domain-containing protein 2 (SUN2) axis.

On the other hand, it is associated with chemotherapy resistance

through FBXO2. In PTC, UPS promotes the ubiquitination and

degradation of p53 through abnormal expression of FBXO2, promoting

cell proliferation and being related to tumor size and metastasis

(20). In OSCC, UPS regulates the

transformation of tumor cells to highly malignant clones through

FBXO2, promoting malignant processes such as proliferation and

invasion (21). The basic

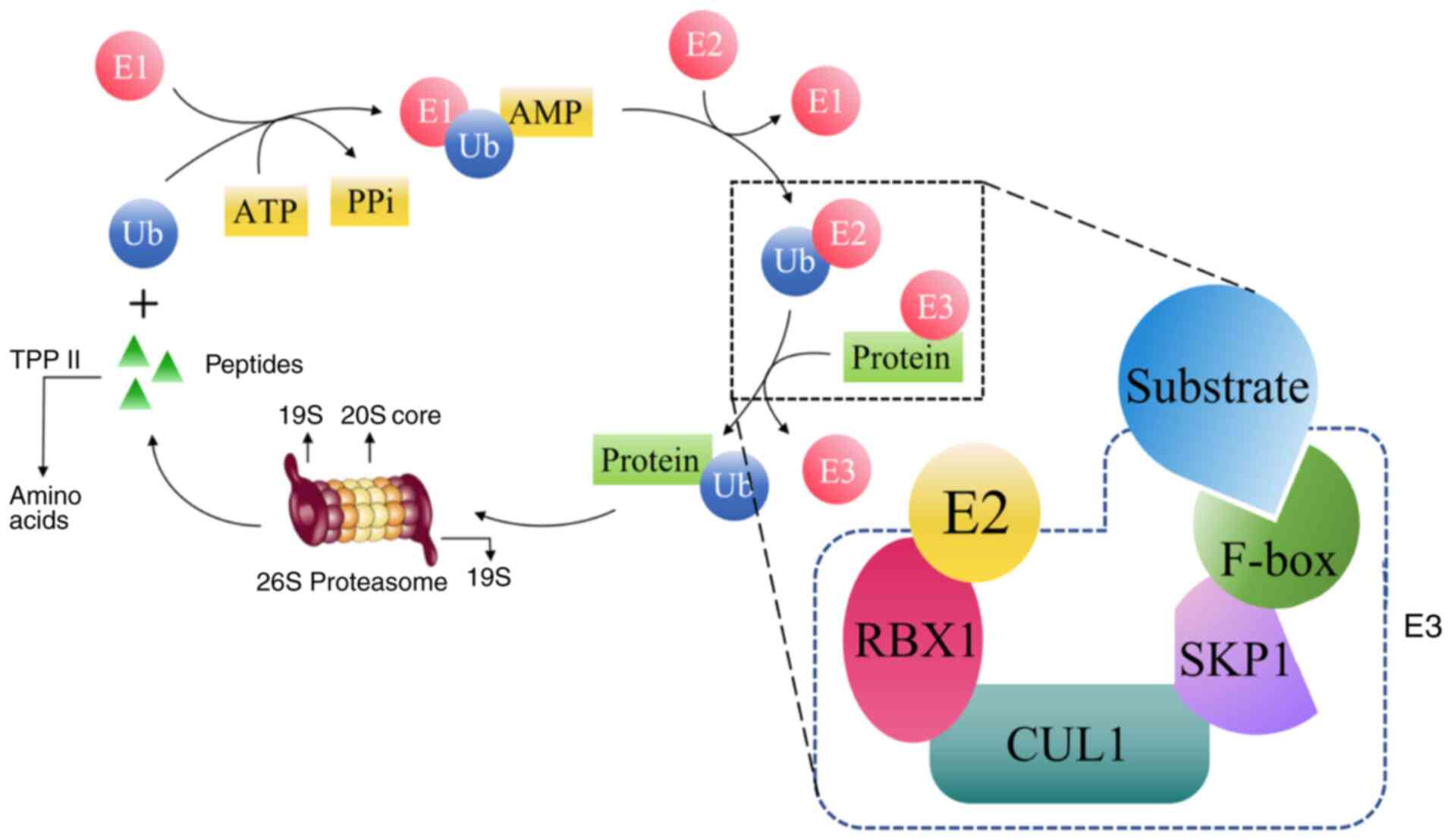

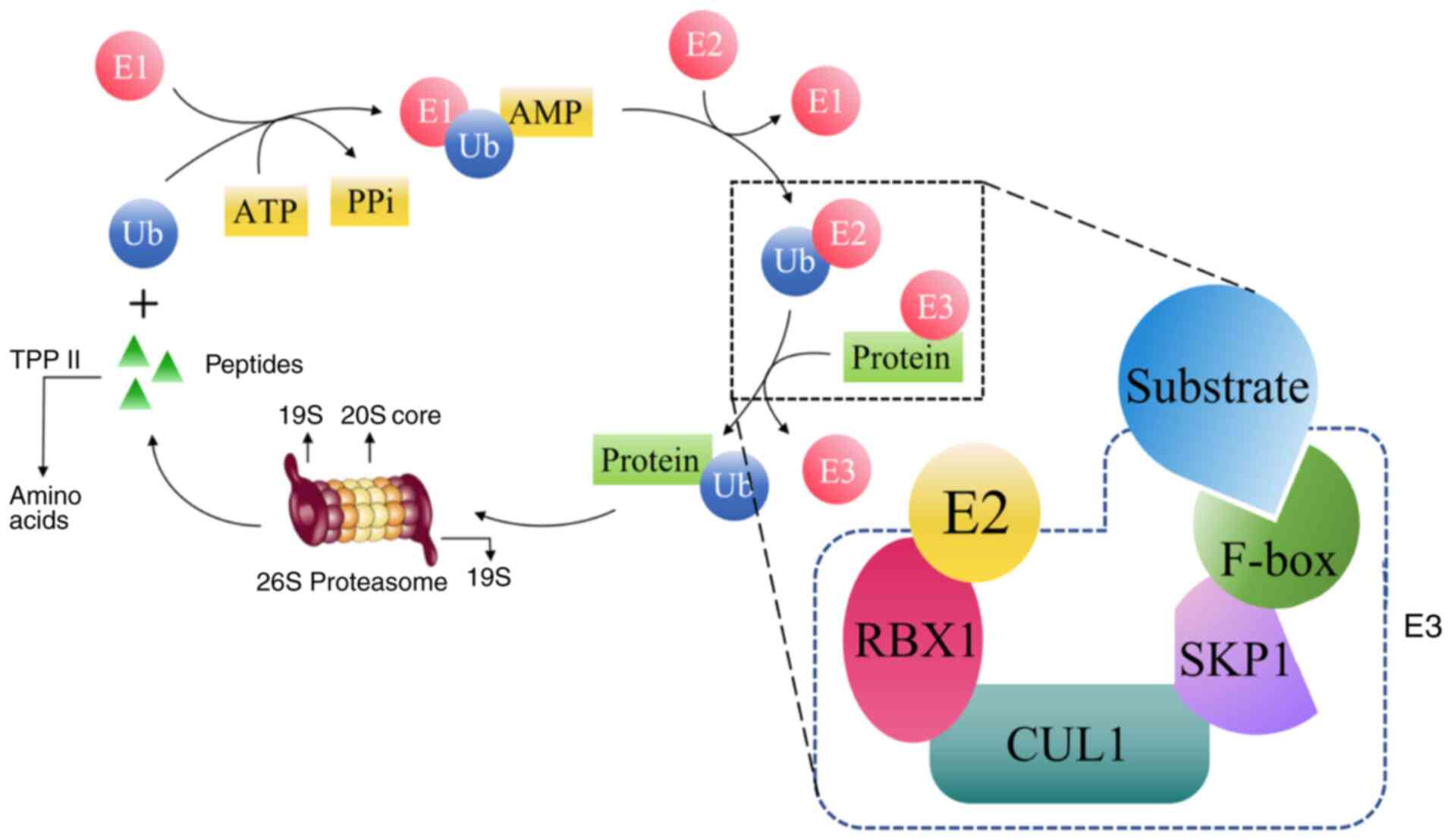

components of the UPS comprise ubiquitin, E1, E2, E3, the 26 S

proteasome and deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) (3). The process by which ubiquitin binds

to a substrate and causes it to be degraded is referred to as

ubiquitination (3). Ubiquitination

is a protein degradation process involving a multi-step cascade

reaction, primarily mediated by three types of ubiquitinating

enzymes: E1, E2 and E3. Initially, E1 utilizes the energy released

from ATP hydrolysis to form a thioester bond between the C-terminal

of ubiquitin and the cysteine residue at the active site of E1,

thereby activating ubiquitin, which constitutes the first step of

ubiquitination. Subsequently, the activated ubiquitin is

transferred to the cysteine residue located at the active site of

E2. After which, the activated ubiquitin is transferred to a

cysteine residue located at the active site of the E2, leading to

the formation of a thioester bond between the E2 enzyme and

ubiquitin. Then, in a two-step reaction, the E2 enzyme facilitates

the attachment of ubiquitin to the substrate with the assistance of

E3 that recognizes a specific target. In this process, the

specificity for substrates is guaranteed by 500–1,000 specific E3

enzymes encoded in the human genome (3,4,7,29).

Eventually, the substrate proteins marked with ubiquitin are broken

down by the 26S proteasome, which in turn regulates DNA repair,

influences stress responses and modifies cell proliferation

(30) (Fig. 1). When mutated or overexpressed in

various malignancies, ubiquitinating enzymes affect and regulate

various cellular pathways, such as protein transport, chromatin

remodeling, the cell cycle and apoptosis. Overexpression of NEDD4-1

in liver cancer can affect protein transport-related signals by

regulating AKT ubiquitination, promoting the cell cycle and

inhibiting apoptosis (31). In

multiple myeloma, it can also mediate AKT degradation to accelerate

apoptosis (32). MDM2

overexpression in cancer can degrade p53 and interfere with

apoptosis and the cell cycle (33). Mutation will cause loss of

substrate degradation ability, leading to uncontrolled cell cycle

and abnormal proliferation (34).

Therefore, the UPS serves a vital role in oncogenic signaling and

the development of malignant tumors (7). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated

that the UPS also exerts a notable role in neurodegenerative

diseases and various inflammatory reactions (23).

| Figure 1.Schematic diagram of the

ubiquitination process. E1, ubiquitin-activating enzyme; E2,

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme; E3, ubiquitin ligase; TPP II,

tripeptidyl peptidase II; RBX1, ubiquitin ligase with zinc finger

structure; CUL1, Cullin-1 proteins; SKP1, S-phase kinase-related

protein 1; F-box, F-box protein; Ub, ubiquitin; PPi,

pyrophosphate. |

Among ubiquitinating enzymes, the selectivity of the

UPS is determined by the E3 ligase (7,28). A

number of E3 ligases, when dysfunctional, can impair DNA damage

repair, cause cell cycle disturbances, lead to abnormal gene

expression regulation and disrupt or continuously interrupt signal

transduction, ultimately exerting carcinogenic or tumor-promoting

effects. For instance, anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) is a

representative E3 ligase that is indispensable for mitotic

progression (35). Research has

revealed that the abnormal regulation of cell division cycle 20

(CDC20) and cadherin 1 (CDH1) is linked to cancer (36). Inhibition of CDC20 can disrupt

mitosis and subsequently induce cell apoptosis, which suggests that

CDC20 possesses oncogenic characteristics (36,37).

The depletion of CDC20 can suppress the Wnt signaling pathway, in

turn reducing the proliferation of cancer cells in colon cancer

(38,39). CDH1 facilitates the

ubiquitination-mediated hydrolysis process initiated by BRAF either

in an APC-dependent or APC-independent manner, thereby contributing

to tumor formation (35).

Neurologically expressed developmentally downregulated 4-1

(NEDD4-1) has been demonstrated to exert a vital function in

modulating cancer progression. Specifically, NEDD4-1 stabilizes

MDM2 via Lys63-linked polyubiquitination, a process that

facilitates p53 degradation and thereby enhances cell proliferation

(31). Furthermore, NEDD4-1 binds

to N-Myc and strengthens the polyubiquitination of this protein,

thereby promoting the proliferation of neuroblastoma cells

(40). Silencing of NEDD4-1

results in reduced AKT phosphorylation and increased PTEN

expression, which in turn inhibits the proliferation and migration

of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (41). In addition, NEDD4-1 mediates the

ubiquitination of AKT at the Ser473 site, which triggers

phosphorylation at this position. This process promotes the

proteasomal degradation of AKT, thereby inhibiting AKT signaling

and accelerating apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells (32). MDM2, a key regulator of the tumor

suppressor p53, mediates the ubiquitination of p53 and triggers its

degradation via the proteasome. Mutations or deletions of p53 are

present in approximately half of all types of cancer (33). MDM2 expression is upregulated in

numerous cancer types, such as lung cancer and liver cancer, and

the chemotherapeutic drug cisplatin induces apoptosis in cancer

cells by phosphorylating and activating the p53 protein (42). However, increased MDM2 expression,

combined with p53 mutations or downregulation, leads to the

development of cisplatin resistance in epidermoid carcinoma

(42).

The E3 ligases that regulate the

ubiquitination-mediated degradation of proteins can be mainly

classified into two types (30).

HECT ligases are characterized by a C-terminal domain. They first

form a thioester bond to receive ubiquitin molecules from E2

ligases, after which the ubiquitin undergoes refolding and is

transferred to substrate proteins (43). RING ligase, which consists of RING

and RING-like ligases and their accompanying proteins, has a zinc

finger that transfers ubiquitin directly to the substrate via the

ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 (44). CRL is the most extensive E3 ligase

and serves a role in cancer. CRL1 ligase, otherwise referred to as

the SCF complex, comprises FBPs and FBXW7 as key components. These

elements serve a role in regulating the stability of diverse

cellular factors, including cell cycle regulators, oncogenic

transcription factors, cell surface receptors and signaling

molecules (34,45). Consequently, impairment of the

SCF-FBXW7 complex leads to unregulated cell proliferation and

survival, genomic instability and disordered signaling pathways

that promote cancer invasion and metastasis (46–48).

In summary, the substrate specificity of the SCF

complex is governed by FBPs, with each type of FBP capable of

recognizing and binding to a unique range of substrates (49). In addition to being components of

the SCF complex, FBPs are involved in DNA replication,

transcription, cell differentiation and cell death (50).

Composition and role of the FBP family

According to their specific structural domains, FBPs

can be further divided into three subfamilies: i) FBXL; ii) FBXW;

and iii) FBXO (10,11). FBPs directly interact with

post-translationally modified substrates and mediate the

ubiquitination and degradation of target proteins in various

cellular biological processes, such as the cell cycle,

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), apoptosis and multiple

tumor-related signaling pathways (such as the PI3K-AKT-mTOR, p53

and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 pathways), thus

affecting tumor progression (51).

Numerous members of the FBP family serve notable

roles in tumor development (Table

SI). For instance, SKP2 engages with multiple signaling

cascades, including but not limited to the PI3K/Akt (52), ERK (53), peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor γ (54), insulin-like

growth factor 1 (55) and mTOR

(10) signaling pathways. Through

the aforementioned signaling pathways and their potential

interactions, SKP2 exhibits high expression in breast cancer,

melanoma, pancreatic cancer, GC, lymphoma, prostate cancer and

nasopharyngeal cancer; notably, its high expression is associated

with poor prognosis in these malignancies (56). The dysregulation of the

SKP2/mH2A1/CDK8 pathway and the hydrolysis of mH2A1 by

SKP2-targeted proteins are crucial for breast cancer progression

and prognosis (57,58). In gliomas, FBXL18 exerts oncogenic

effects by curbing apoptosis, which is achieved through promotion

of K63-linked ubiquitination of AKT (59). In OV, FBXO6 (60) and FBXO16 (61) function as proto-oncogenes through

ribonuclease T2 and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L

ubiquitination and degradation, respectively. Additionally, FBXO32

promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression by targeting PTEN and

promoting its degradation to regulate the cell cycle, promote the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and ultimately accelerate EMT (62). FBXO32 acts as a target gene for

melanocyte inducing transcription factor (a major transcription

factor in melanocytes), facilitating melanoma progression in

vivo, and the knockdown of FBXO32 induces global changes in

melanoma gene expression profiles (63).

On the other hand, FBXW7, as an oncogene, mediates

tumor suppression by negatively regulating a number of oncogenic

proteins (50). The inactivation

of this protein in lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC,

breast cancer and hematopoietic system tumors holds importance for

the initiation and progression of these malignancies (64). Among the five types of tumors

mentioned above [lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC, breast

cancer and hematopoietic system tumors], microRNA-223 influences

the proliferation and apoptosis of CRC cells by activating the

NOTCH and AKT/mTOR pathways (65).

Thus, it can be inferred that the loss of FBXW7 may serve as an

independent prognostic marker for tumors (64). It has also been shown that FBXO4

acts as another tumor suppressor within the FBP family, and it

facilitates ubiquitin-mediated degradation of cyclin D1 through

phosphorylation at the Thr286 site (8). Consequently, dysfunction of FBXO4

causes cyclin D1 to accumulate in vivo and drives the

progression of malignant tumors, including melanoma (66) and esophageal cancer (67,68).

The absence of FBXO4 expression in mice caused cyclin D1

accumulation, and thus, malignant transformation of BrafV600E

melanoma, suggesting that FBXO4 deficiency serves a role in

melanoma development (66). These

studies have substantiated the tumor-suppressive effects of FBXO4

(8,66–68).

FBXO11 and FBXO31 are also recognized tumor suppressors, and both

target a variety of oncogenic substrates. For instance, FBXO11

mediates the ubiquitination-dependent degradation of the

proto-oncogene product B-cell lymphoma 6 protein, and it is often

absent or mutated in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (69). FBXO31 orchestrates its regulatory

role in tumor-related processes by triggering the ubiquitination

and degradation of distinct substrates, with the underlying

mechanism exhibiting substrate-specific divergence. For cyclinD1,

FBXO31 exerts its function by recognizing phosphorylation

modifications (e.g., at the Thr286 site) of cyclinD1; it then

associates with the SCF (SKP1-Cullin-F-box) E3 ubiquitin ligase

complex, thereby facilitating the ubiquitination and subsequent

proteasomal degradation of cyclinD1 to preclude aberrant cell cycle

progression (70). In the case of

SNAIL, a key transcription factor governing epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT), FBXO31 binds to specific structural domains of

SNAIL, which disrupts the interaction between SNAIL and its

stabilizing factors (e.g., SIP1) and induces conformational changes

in SNAIL. These events collectively promote the ubiquitination and

degradation of SNAIL, ultimately suppressing tumor cell invasion

and metastasis (71). Regarding

MDM2, the E3 ubiquitin ligase of the tumor suppressor p53, FBXO31

interacts with the RING domain of MDM2 to trigger MDM2

self-ubiquitination. This self-ubiquitination leads to MDM2

degradation, which alleviates the inhibitory effect of MDM2 on p53

and restores the tumor-suppressive functions of p53 (e.g., cell

cycle arrest and apoptosis induction) (72). For mitogen-activated protein kinase

kinase 6 (MAPKK6), a pivotal upstream kinase in the MAPK signaling

pathway, FBXO31 is capable of recognizing the unique conformational

state of hyperactivated MAPKK6. It then mediates the ubiquitination

and degradation of hyperactivated MAPKK6 via the SCF complex,

preventing excessive activation of the MAPK pathway and the

consequent abnormal cell proliferation (73). Collectively, FBXO31 achieves the

goal of inhibiting the occurrence and development of various

malignant tumors such as breast cancer (74), OV (75), liver cancer (76) and prostate cancer (77) by triggering the ubiquitination

degradation of specific substrates. Additionally, FBXL14 is capable

of inducing the ubiquitination-mediated degradation of the key

oncogene c-Myc. However, in glioma stem cells, this ubiquitination

process can be reversed by the DUB ubiquitin specific peptidase 13

(USP13), which suggests that an antagonistic relationship exists

between FBXL14 and USP13 (78).

Furthermore, FBXL14 can target and degrade CUB domain-containing

protein 1 (CDCP1), thereby reducing the stability of CDCP1 and

inhibiting breast cancer metastasis (79).

Taken together, all of the aforementioned FBP family

members influence various cellular signaling pathways via UPS, and

thereby affect the progression of malignant tumors.

Introduction of FBXO2

FBXO2, alternatively referred to as Fbx2, Fbg1,

Fbs1, neural F-box 42 kDa (NFB42) and organ of Corti protein 1, is

an FBP. It is highly abundant in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells

and functions as a subunit of the E3 ligase (80,81).

Research on FBXO2 began with the proteomic analysis of rat neural

tissues. As early as 1998, researchers identified an FBP referred

to as NFB42, with a molecular weight of ~42 kDa, in rat brain

tissues. This protein was highly expressed in neurons and served a

role in sustaining the non-dividing state of cells (82). Subsequently, through homology

sequence cloning technology, it was revealed that human FBXO2

(Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man 607112) is situated on

chromosome 1p36.22 and comprises six exons encoding a cytoplasmic

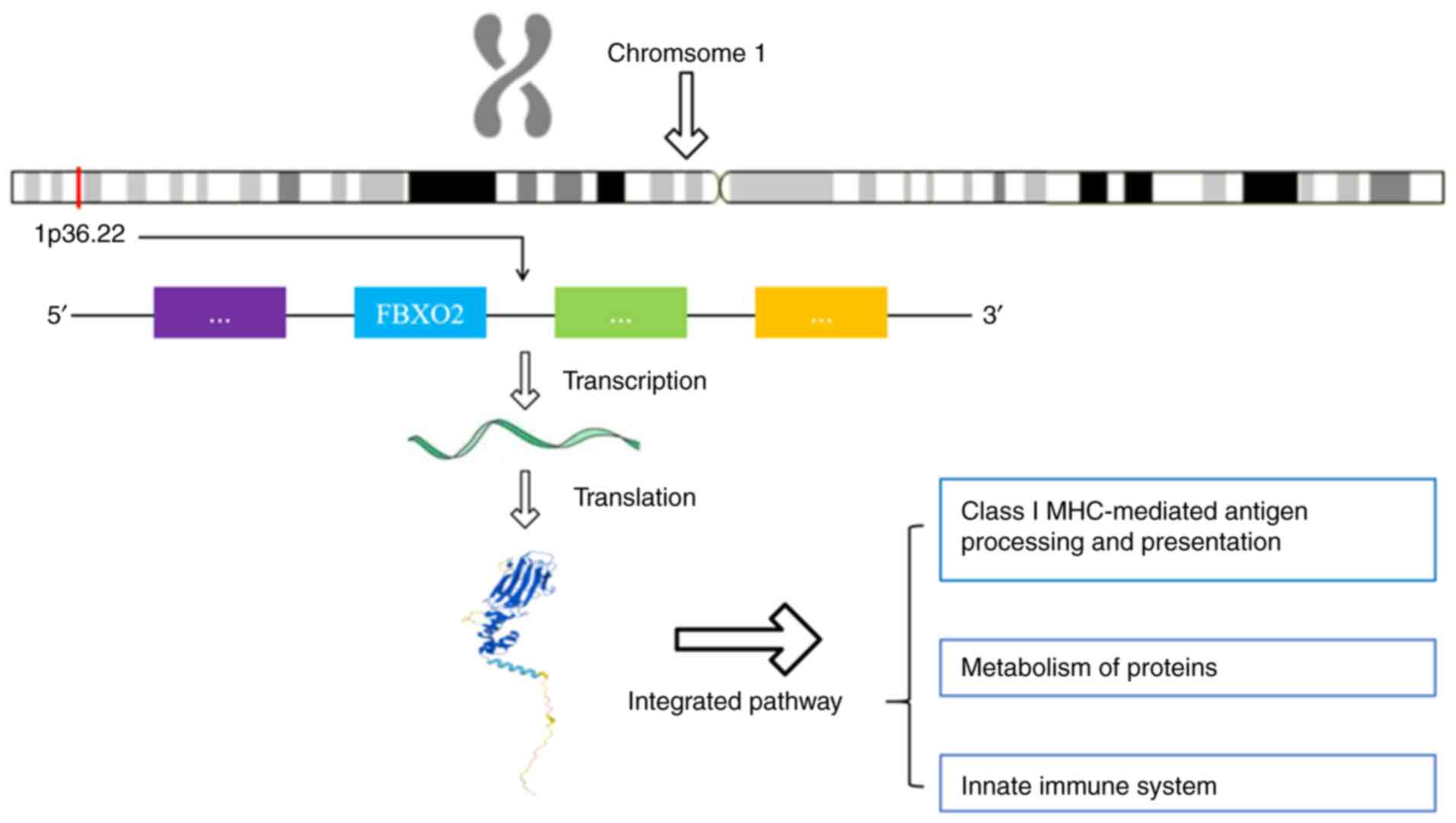

protein containing 296 amino acids (83) (Fig.

2). The human FBXO2 consists of an F-box domain (FBA) and a

glycoprotein-binding domain (SBD). The FBA domain is situated at

the N-terminal and exhibits a triple-helical bundle conformation

(84). It binds to the SKP1

protein within the SCF complex and serves as the core module for E3

ligase activity (83). The SBD is

located at the C-terminal and contains multiple protein interaction

modules, such as hydrophobic pockets and sugar recognition motifs

(84,85). For instance, FBXO2 recognizes the

Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein B (gB) through glycosylation sites

and mediates its endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

(86). Research into the

functionality of FBXO2 has indicated that it functions as the

substrate recognition subunit of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex,

facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of a variety of

proteins (87,88). Further research has shown that

FBXO2 is abnormally highly expressed in various cancer types (such

as OV and thyroid cancer), and promotes tumor progression by

regulating key signaling molecules such as p53 (16,20).

Comparative genomics studies have shown that FBXO2

has similar domain composition and substrate recognition abilities

in species such as mammals, birds and fish, but its regulatory

network shows certain adaptive differentiation among different

species (89–91). FBXO2 is specifically expressed in

tissues such as the brain and adrenal glands of mice, and its

absence leads to the accumulation of amyloid precursor protein in

neurons, suggesting its potential role in Alzheimer's disease (AD)

(92). Additionally, FBXO2

participates in the mechanism of liver fibrosis induced by

excessive exercise in mice by regulating the formation of muscle

lactate vesicles (89). In fish,

the homologous genes may be involved in ubiquitination regulation

during liver development. For instance, the abnormal expression of

FBXO32 in fish skeletal muscle tissues is associated with muscle

atrophy (90), suggesting the

conserved function of F-box family genes in organ development.

FBXO2 exhibits conservation during the evolution of insect sex

chromosomes, and its biological function may be associated with the

dosage compensation effect of insect sex chromosomes (i.e.,

balancing the expression dosage of genes on sex chromosomes between

male and female individuals through specific mechanisms to maintain

normal physiological functions) (91). Current studies have not yet

identified the homologous gene of FBXO2 in fruit flies, but FBPs

serve a key role in the asymmetric division of neural stem cells,

indicating the cross-species conservation of ubiquitination

regulation in stem cell biology (93).

FBXO2, as an important member of the FBP family,

exhibits both evolutionary conservation and functional diversity,

making it a hot topic in interdisciplinary research. From neural

development to disease regulation, FBXO2 precisely regulates

protein homeostasis through the ubiquitin network. Future studies

need to further analyze the regulatory differences of FBXO2 in

various diseases and explore its potential as a therapeutic target

for diseases.

Role and mechanisms of FBXO2 in

non-tumorigenic diseases

FBXO2 holds considerable importance in metabolic

disorders. FBXO2 is a functional E3 ligase for insulin receptors

(IRs) in the liver, and FBXO2 protein and mRNA levels are increased

in the livers of obese individuals. FBXO2 mediates the

ubiquitin-dependent degradation of IRs, thereby inhibiting the

PI3K-AKT pathway and impairing the integrity of insulin signaling

(87). This leads to insulin

resistance and abnormal glucose metabolism, offering a novel

therapeutic target for type 2 diabetes and associated metabolic

disorders (87,94). The expression levels of FBXO2 are

elevated in the liver tissues of patients suffering from

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The upregulated FBXO2

aggravates NAFLD by targeting the α subunit of hydroxy-COA

dehydrogenase and promoting its proteasome degradation in HepG2 and

293T cells. This suggests that FBXO2 may serve as a potential

therapeutic target for NAFLD (88). Additionally, FBXO2 exerts

considerable effects in neurological diseases. A study has shown

that there is an association between FBXO2 and the occurrence and

development of Parkinson's disease (PD), and variations in FBXO2

may reduce the risk of PD among Han individuals in mainland China

and serve as a biomarker for risk assessment of PD (95). Cognitive dysfunction is one of the

notable features of AD (96). The

pathogenesis of AD is associated with multiple mechanisms such as

transcriptional dysregulation, erroneous protein degradation and

synaptic dysfunction (97). A

previous study has shown that the upregulation of FBXO2 induced by

histone methyltransferase Smyd3 in AD mouse models (P301S Tau mice)

affected the function of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)

and the cognitive behavior of mice, which provides a potential

therapeutic strategy for AD (97).

Niemann-Pick C (NPC) disease is an autosomal recessive genetic

disorder that ultimately leads to neurodegeneration and premature

mortality. In the central nervous system, FBXO2 localizes to

damaged lysosomes and facilitates their degradation. Deficiency of

FBXO2 delays the clearance of impaired lysosomes, thereby

exacerbating motor function impairments in NPC, intensifying

neurodegeneration, and ultimately reducing survival (98). In osteoarthritis (OA), Tang et

al (99) demonstrated that RNA

binding motif protein 47 stabilized FBXO2 mRNA by activating the

STAT3 signaling pathway, thereby promoting the inflammatory,

apoptotic and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation of

chondrocytes treated with IL-1β, ultimately progressing OA. Another

study (100) employed single-cell

transcriptomic analysis to pinpoint novel specific biomarkers for

nucleus pulposus and intrafibrous annulus cells, while also

defining the cell populations in non-degenerative and degenerative

human intervertebral discs (IVD) from the same individual.

According to gene expression profiles at the single-cell resolution

and Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

analyses, FBXO2 was identified as one of the genes that could

predict IVD degeneration, which offers novel perspectives on the

biomarkers of IVD degeneration, and thus, enhances diagnostic and

therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, previous research (101) has demonstrated that inner ear

organoids are derived from embryonic stem cells, by targeting the

lineage-specific ear gene FBXO2 with the multi-allelic reporter

cassette (Venus/Hygro/CreER), researchers revealed the gradient

characteristics exhibited by cochlear tissue during development

(these characteristics are associated with cell differentiation or

structural formation) through the expression of Venus and the

activity of CreER. This approach also marked the sensory lineage,

confirmed the enrichment of the type I vestibular hair cell

subpopulation and revealed strong expression in adult cerebellar

granule cells. Subsequently, McGovern et al (102) described a novel tamoxifen-induced

CreER mouse strain, referred to as FBXO2CreERT2 mice. In adult

mice, the induction of FBXO2CreERT2 occurred more frequently in

type I hair cells than in type II hair cells. Therefore,

FBXO2CreERT2 mice were considered a novel tool for specifically

manipulating inner ear epithelial cells and targeting the type I

hair cells of the vestibule. The FBXO2/SCF ubiquitin ligase complex

enhances ubiquitin-mediated phagocytosis of group A streptococcus

(GAS) by recognizing the N-acetylglucosamine on GAS side chains,

promoting ubiquitin-mediated ligase activity (103). Additionally, gB in the

Epstein-Barr virus binds to the sugar-binding structural domain of

FBXO2 through its glycosylation site. Through the

ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, gB is degraded to limit viral

infectivity (86).

Role and mechanisms of FBXO2 in tumorigenic

diseases

FBXO2 exerts a cancer-promoting effect in multiple

types of malignancies, such as GC, OV, OS and thyroid cancer, with

its mechanism of action differing according to the specific cancer

type (Table SII). In GC, it

enhances cell proliferation, migration and invasion through the

regulation of EMT (14). In CRC,

it may inhibit tumor suppressor proteins through EMT and UPS

degradation, affecting the Wnt signaling pathway (104). Specifically, FBXO2 regulates key

EMT transcription factors such as SNAIL and TWIST, initiating the

EMT process in CRC cells. Subsequently, these key EMT transcription

factors can bind to the promoter of tumor suppressor genes to

inhibit their transcription, or affect the subcellular localization

and function of tumor suppressor proteins by altering the cell

state. At the same time, EMT may also collaborate with the UPS,

changing the kinase activity to phosphorylate tumor suppressor

proteins, which are then recognized by the UPS and degraded.

Eventually, the inhibition of tumor suppressor proteins will

release the negative regulation on Wnt and other pathways,

promoting the progression of CRC (43). In OV, it promotes cancer

development through the SOX6-FBXO2-SUN2 axis (among them, SUN2 is

fully known as Sad1 and UNC84 domain-containing protein 2, which is

a transmembrane protein located on the nuclear membrane. Its core

function is related to the maintenance of the nuclear membrane

structure, nuclear localization, and the transport of nuclear and

cytoplasmic substances. Additionally, it plays a role in the

connection between the cytoskeleton and the nuclear skeleton) and

related pathways, and is associated with chemotherapy resistance

(16). In addition, in EC it

degrades fibrillin 1 (FBN1) to regulate the cell cycle and

autophagy. In OS, it stabilizes IL-6R to activate the STAT3

signaling pathway (17). In GB, it

participates in tumor-microenvironment interaction (19), and in PTC, it degrades p53 to

promote proliferation (20).

Finally, in oral OSCC, it promotes the transformation of cells to

malignant clones (21). Therefore,

FBXO2 has the potential to act as a biomarker and therapeutic

target in a variety of cancer types.

Effect of FBXO2 on GC and its

mechanisms

GC is a common malignant tumor globally and stands

as the fourth primary cause of cancer-associated deaths. The

incidence of GC rises steadily with age, and the median survival

time for patients with advanced GC is <12 months (105,106). Therefore, it is of great

importance to explore approaches for the management of this disease

(106). Sun et al

(14) used four GC cell lines

(MGC-80-3, AGS, SGC-7901 and MKN-28) to conduct comparisons in

terms of their transcription and translation levels, as well as

migratory and invasive abilities, using reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR, western blotting, Transwell assays

and wound healing assays. To further substantiate the experimental

conclusions, MGC 80-3 cells were transfected with FBXO2 small

interfering RNA (siRNA), and the aforementioned experiments were

repeated. The findings showed that in siRNA-FBXO2 MGC 80-3 cells,

the mRNA expression of FBXO2 was downregulated, and the ability of

cells to proliferate, migrate and invade was notably suppressed.

Additionally, the expression of epithelial markers (E-cadherin

protein) was elevated, and the expression of mesenchymal markers

(N-cadherin and vimentin protein) was notably reduced. All these

results suggested that low FBXO2 expression could inhibit the

proliferation, migration and invasion of GC cells by reducing EMT.

In summary, FBXO2 has the ability to promote the proliferation,

migration and invasion of GC cells, and FBXO2-mediated EMT serves a

notable role in the migration and invasion of GC, and may emerge as

a novel target for the diagnosis and treatment of this

malignancy.

Effect of FBXO2 on CRC and its

mechanisms

CRC is the second and third most prevalent cancer

type in women and men, respectively, accounting for 9.2% of global

deaths, with incidence and mortality rates being 25% higher in men

than in women (107). Wei et

al (15) observed that FBXO2

was mainly expressed in the cytoplasm of CRC cells, and that the

overexpression of FBXO2 increased the expression of N-cadherin.

This indicates that FBXO2 is implicated in CRC metastasis through

EMT. In this article (15), the

team further investigated and found that the mechanism by which

FBXO2 promotes the development of CRC may be through the

degradation of N-cadherin by UPS, which regulates the tumor

proliferative activity of CRC. In addition, the excessive

expression of N-cadherin in CRC can further impact the expression

and localization of β-catenin. Furthermore, Zhao et al

(104) demonstrated that

β-catenin serves a notable role in the Wnt signaling pathway and

colon cancer development. These studies further suggested that the

upregulation of FBXO2 expression is associated with proliferation,

infiltration and distant metastasis of CRC, and that the inhibition

of FBXO2 expression may constitute a therapeutic strategy to

improve the prognosis of patients with CRC. Therefore, expression

levels of FBXO2 can serve as a potential biomarker for CRC

metastasis.

Effect of FBXO2 on OV and its

mechanisms

OV is the fifth most lethal cancer among women

globally, with an incidence and mortality rate of 3.4 and 4.7%,

respectively. This indicates that it poses a serious threat to the

health and survival of women (108). Ji et al (16) found, through analysis of multiple

genetic databases, that FBXO2 was highly expressed in OV tissues

and cells. The underlying mechanisms may involve the transcription

factor SOX6 binding to FBXO2, which leads to the abnormal

upregulation of FBXO2 expression. Subsequently, FBXO2 binds to the

glycosylated SUN2 protein and functions as an E3 ligase to mediate

the ubiquitination-dependent degradation of SUN2. This process

inhibits apoptosis, promotes cell proliferation and ultimately

accelerates the progression of OV. Further silencing of FBXO2

expression using short hairpin RNA revealed that cells with FBXO2

silenced showed reduced proliferative, migratory and invasive

abilities compared with previously. Furthermore, in in vivo

experiments, the knockdown of FBXO2 led to a notable reduction in

the volume, size and weight of subcutaneous tumors. Thus, the

aforementioned findings revealed a novel SOX6-FBXO2-SUN2 axis that

serves a role in OV development, and targeting this axis could

serve as an effective therapeutic approach for OV. Recent research

(109) has indicated that FBXO2

is capable of impacting chemotherapy resistance. It achieves this

by affecting the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, as well as the

interactions between focal adhesions and ECM receptors, while also

regulating tumorigenesis. In vitro experiments showed that,

in A2780 and SKOV3 OV cell lines where FBXO2 was silenced, the 50%

maximum inhibitory concentration of cisplatin was reduced. This

suggests that FBXO2 is a potential biomarker linked to chemotherapy

resistance in high-grade serous OV (HGSOC), and it can act as a

valuable prognostic indicator as well as a potential target in

HGSOC (109).

Effect of FBXO2 on EC and its

mechanisms

EC accounts for >90% of all uterine malignancies,

and its incidence is increasing. The majority of patients diagnosed

with EC are postmenopausal, with the median age at diagnosis being

60 years (110). Therefore,

improving the early diagnosis and prognostic assessment of patients

with EC is of critical importance (110). Che et al (17) revealed that FBXO2 binds to and

causes the degradation of FBN1 via polyubiquitination, which is

further enhanced by the regulation of cell cycle proteins (CDK4,

CyclinD1, CyclinD2 and CyclinA1) and the inhibition of autophagy

signaling pathways [autophagy related 4A cysteine peptidase (ATG4A)

and ATG4D], to promote EC proliferation. Subsequently, a knockdown

mouse model, verification via immunohistochemistry and other

techniques confirmed that FBXO2 knockdown led to elevated FBN1

expression and reduced Ki67 expression. Additionally, either FBN1

knockdown alone or the combined knockdown of both FBXO2 and FBN1

resulted in decreased Ki67 expression. These results implied that

the deletion of FBN1 blocks the proliferative effect of FBXO2. In

conclusion, the aforementioned experimental study demonstrated that

targeting FBXO2 may treat EC through the regulation of cell cycle

and autophagy signaling pathways, and that patients with high FBXO2

expression may be potential candidates for treatment with CDK4/6

inhibitors in EC (17).

Effect of FBXO2 on OS and its

mechanisms

OS is the most common primary bone malignancy,

characterized by strong local invasiveness and metastatic

potential, with the 5-year survival rate of patients with

metastases being <20% (111).

Research into improving the survival of patients with OS has proved

challenging. Zhao et al (18) confirmed that the persistent

activation of the IL-6 signaling pathway is harmful to bone tissue

and hypothesized that this ultimately contributes to the

development of OS. Through further research, it was identified that

upregulated FBXO2 in OS cells binds to the C-terminal SBD of IL-6R.

This binding gives rise to a stable complex. Once the stable IL-6R

binds to IL-6, it recruits Janus kinase, which in turn causes the

continuous phosphorylation of the Y705 site on STAT3. This, in

turn, activates the STAT3 signaling pathway. A luciferase reporter

gene assay showed that the overexpression of FBXO2 tripled the

transcriptional activity of STAT3, and the mRNA levels of its

downstream target genes [such as the anti-apoptotic proteins Mcl-1

and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP)] were notably

upregulated. Chromatin immunoprecipitation further confirmed that

FBXO2 strengthened the binding of STAT3 to the promoters of Mcl-1

and XIAP, promoting their transcription and ultimately promoting

the multiplication of OS cells. In a nude mouse xenograft model,

the expression levels of IL-6R and phosphorylated STAT3 in the

tumors formed by U2OS cells with FBXO2 knockout were notably

reduced, and the protein levels of Mcl-1 and XIAP decreased by

~50%. This directly demonstrated the core role of the

FBXO2-IL-6R-STAT3 axis in tumor growth. Treatment of cells

overexpressing FBXO2 (such as MG63 cells) with STAT3 inhibitors

(such as Stattic) could reverse their promoting effect, and the

cell count returned to the level of the control group. Furthermore,

the addition of IL-6R neutralizing antibodies (such as CNTO328)

also notably inhibited STAT3 activation mediated by FBXO2 and cell

proliferation. According to the aforementioned research, in OS, the

function of FBXO2 undergoes a functional reversal, whereby its

glycoprotein recognition domain specifically binds to IL-6R,

inhibits its degradation to stabilize the receptor and thereby

activates the STAT3 signaling pathway, instead of following the

traditional ubiquitination degradation pathway. Therefore,

inhibiting the expression or activity of FBXO2 may represent an

effective therapeutic strategy for OS (112). At present, biotherapies aimed at

the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway primarily center on monoclonal

antibodies. Based on the aforementioned study, the application of

IL-6 monoclonal antibodies may prove to be an effective approach

for the treatment of OS.

Effect of FBXO2 on GB and its

mechanisms

GB is the most common and highly malignant primary

brain tumor among adults. The median survival is 14–24 months and

surgical treatment is the main therapeutic modality (113). However, the recurrence rate

remains high and the prognosis remains poor (113). Buehler et al (19) revealed that FBXO2 expression was

increased in recurrent GB, and that knockdown of FBXO2 enhanced

in vivo survival and mitigated the invasive growth of glioma

cells in brain sections. FBXO2 was also found to be concentrated in

the infiltration zone, with FBXO2-positive cancer cells being

linked to synaptic signaling processes. In addition, Atkin et

al (114) found that FBXO2 in

the brain governs the abundance and localization of specific NMDAR

subunits, GluN1 and GluN2A, and affects synapse formation and

maintenance to a certain degree. The aforementioned research

illustrates the potential function of FBXO2-dependent interactions

within the glioma microenvironment in facilitating tumor growth.

Thus, inhibition of FBXO2 may be used to treat recurrent GB.

Effect of FBXO2 on PTC and its

mechanisms

PTC accounts for ~84% of all thyroid cancers. It is

categorized as a well-differentiated thyroid cancer, with the

5-year relative survival rate reaching 98.5%. The majority of cases

of well-differentiated thyroid cancer are asymptomatic and are

identified during physical examinations or incidentally during

diagnostic imaging studies. Surgery is effective for the majority

of cases of well-differentiated thyroid cancer, and post-surgical

radioactive iodine treatment is capable of enhancing the overall

survival rate in patients at a high risk of recurrence (115). Anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase

inhibitors and targeted therapies against the genetic mutations

that cause thyroid cancer are increasingly being used in the

treatment of metastatic diseases (115). Guo et al (20) performed in vitro experiments

to examine FBXO2 expression in PTC tissues. The findings indicated

that FBXO2 expression was upregulated in both PTC tissues and cell

lines. The expression levels of FBXO2 were positively associated

with the tumor size of PTC, as well as lymph node metastasis and

extracapsular invasion. Furthermore, silencing of FBXO2 suppressed

the proliferation of PTC cells and induced cell apoptosis, while

the overexpression of FBXO2 notably boosted the proliferation of

PTC cells. A mechanistic study demonstrated that FBXO2 is capable

of directly binding to p53 and facilitating its ubiquitination and

degradation (20). Knocking down

the p53 gene to a certain extent weakened the inhibitory effect of

FBXO2 knockdown on the progression of PTC cells, allowing the

proliferation, invasion, and metastasis processes of the originally

blocked tumor cells to recover. Knockdown of FBXO2 suppressed the

proliferation of PTC cells and promoted their apoptosis by

targeting p53 for ubiquitination and degradation (20). The aforementioned research findings

lay the groundwork for the diagnosis and treatment of PTC.

Effect of FBXO2 on OSCC and its

mechanisms

OSCC accounts for >90% of all malignant tumors in

the oral cavity (116). Due to

the extensive genetic susceptibility of the oral mucosa of patients

with OSCC to carcinogenic factors, the risk of developing

concurrent tumors in the oral cavity notably increases (116). Cheng et al (21) established the evolutionary

trajectory of tumor cells by relying on single-cell RNA sequencing

data, identified the dynamic clonal characteristics of OSCC and

further clarified that FBXO2 is a key gene that determines the

specific transcriptional state leading to the transformation of

tumor cells into clones with notably high malignant

characteristics. The expression levels of FBXO2 in OSCC are notably

higher than those in normal samples, particularly in patients with

more advanced clinical stages. In OSCC cells, knockdown of FBXO2

leads to a corresponding inhibition of cell proliferation,

G1-S phase transition, migration, invasion, EMT and

anti-apoptotic capacity, whereas its overexpression results in the

promotion of these processes (117). These findings offer novel

perspectives on clonal heterogeneity and lay the foundation for

more effective therapeutic approaches against OSCC, as well as for

overcoming the resistance of OSCC to treatment.

Role of FBXO2 in clinical tumor

treatment

FBXO2 is involved in the specific recognition and

degradation of substrate proteins within the UPS. Impairment of its

function is closely linked to the onset and progression of various

tumors such as GC (14), OV

(16), OS (18) and thyroid cancer (20), thereby endowing it with the

potential to act as a diagnostic or prognostic biomarker. In OV, Ji

et al (16) demonstrated

that the transcription factor SOX6 promotes the expression of FBXO2

by recognizing the potential response elements located in the

promoter region of FBXO2., Abnormally highly expressed FBXO2

targeted and degraded the tumor suppressor gene SUN2, inhibited

cell apoptosis and activated the proliferation-promoting signaling

pathway, thereby promoting the progression of OV. Knockdown of

FBXO2 notably inhibited the proliferation, metastasis and apoptosis

of OV cells, suggesting that its high expression may serve as an

independent indicator of poor prognosis in OV. In related research

on GB (19), it was found that

FBXO2 was continuously upregulated in recurrent GB, and its

expression levels exhibited a negative association with patient

survival rates. In addition, it was demonstrated that knockout of

FBXO2 could prolong the survival period of mice in an orthotopic

xenograft model and reduce the invasive growth of tumors in

organoid brain slices. Further analysis showed that high FBXO2

expression was related to the enrichment of tumor infiltration

areas and the interaction between glioma and the microenvironment,

and may promote malignant progression by regulating the interaction

between tumor cells and surrounding tissues (19). Through immunohistochemical studies

on CRC, it was revealed that high expression of FBXO2 is closely

related to distant metastasis and the American Joint Committee on

Cancer clinical stage of CRC, and is an independent influencing

factor for poor prognosis of patients (15,104). In addition, its carcinogenic

mechanisms may be related to regulating tumor proliferation

activity (positively associated with Ki-67 expression) and

angiogenesis formation (positively associated with VEGF expression)

(104). When exploring the

potential of FBXO2 as a diagnostic biomarker, a new patented study

(Chinese patent no. CN111381047A) proposed that detecting the

autoantibodies of FBXO2 in serum could be used for lung cancer

screening. Clinical data indicated that the levels of FBXO2

autoantibodies in the serum of patients with lung cancer were

notably lower compared with those of healthy controls, with a

specificity of 96.6% but a sensitivity of 20.0%. It is hypothesized

that combination with other markers may further improve the

diagnostic efficacy. Currently, this method still needs to be

verified by a larger-scale cohort study.

At present, the development of specific

small-molecule compounds targeting FBXO2 remains in the early

stages. Some proteasome inhibitors (such as bortezomib and MG-132)

(32,118) are not specifically targeted at

FBXO2, but can inhibit the degradation function of its substrates

by blocking the UPS. For example, treatment with MG-132 can

increase the accumulation of FBXO2 substrate proteins, thereby

indirectly inhibiting its oncogenic activity (118). Salidroside (a metabolic

regulator) can reduce the secretion of lactate vesicles carrying

FBXO2 by muscles in an over-exercise -induced liver fibrosis model,

thereby alleviating liver cell apoptosis and fibrosis (89). This suggests that metabolic

intervention may affect the intercellular transfer of FBXO2,

providing novel ideas for cancer treatment.

Summary and future prospects

In conclusion, the relationship between the FBP

family and tumors has attracted significant attention from

researchers. As research progresses, a more comprehensive

understanding of the interactions among the FBP family members is

required. Future drug development should focus on the complex

interactions and regulatory mechanisms of the FBP family to target

drugs at the FBP family. Among them, FBXO2 is a key component of

the ubiquitin ligase SCF complex. Besides serving a notable role in

hepatic glucose metabolism and cerebral degenerative diseases,

abnormally expressed FBXO2 is closely linked to the progression of

diverse tumors, such as GC, CRC, OV, EC, GB, thyroid cancer and

OSCC, and is also regarded to be one of the proto-oncogenes. In the

present review, the association between FBXO2 and tumorigenesis and

development was analyzed by reviewing the composition of the UPS

and FBP families, the roles they serve in malignant tumors, and the

progress of research on the relationship between FBXO2 and tumors.

Nevertheless, the complex mechanisms through which upregulated

FBXO2 promotes the growth, migration and invasion of various tumors

needs to be further studied in depth, which will help to more

clearly elucidate the pathogenic mechanisms of tumors and offer

novel avenues for the treatment of human malignant neoplasms.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by The Human Resources and

Social Security Department System of Shanxi Province, the Fund

Program for the Scientific Activities of Selected Returned Overseas

Professionals in Shanxi Province (grant no. 20210001), the Research

Project Supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (grant no.

2021-116), Shanxi ‘136’ Leading Clinical Key Specialty (grant no.

2019XY002) and Shanxi Provincial Key Laboratory of Hepatobiliary

and Pancreatic Diseases (under construction).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JZ was responsible for drafting and revising the

manuscript; JY, XZ, YY, SS and SZ collected relevant literature and

assisted in manuscript revision. JZ and JY designed the tables and

figures. JH revised the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable. All authors have read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

FBXL

|

F-box protein with leucine-rich amino

acid repeats

|

|

FBXW

|

F-box protein with WD-40 amino acid

repeats

|

|

FBXO

|

F-box protein with only

uncharacterized structural domains

|

References

|

1

|

Soerjomataram I and Bray F: Planning for

tomorrow: Global cancer incidence and the role of prevention

2020–2070. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:663–672. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Gong J, Cao J, Liu G and Huo JR: Function

and mechanism of F-box proteins in gastric cancer (Review). Int J

Oncol. 47:43–50. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Çetin G, Klafack S, Studencka-Turski M,

Krüger E and Ebstein F: The ubiquitin-proteasome system in immune

cells. Biomolecules. 11:602021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Zheng N, Zhou Q, Wang Z and Wei W: Recent

advances in SCF ubiquitin ligase complex: Clinical implications.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1866:12–22. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kim YJ, Lee Y, Shin H, Hwang S, Park J and

Song EJ: Ubiquitin-proteasome system as a target for anticancer

treatment-an update. Arch Pharm Res. 46:573–597. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Luo Z, Pan Y, Jeong LS, Liu J and Jia L:

Inactivation of the cullin (CUL)-RING E3 ligase by the

NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor MLN4924 triggers protective

autophagy in cancer cells. Autophagy. 8:1677–1679. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Park J, Cho J and Song EJ:

Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a target for anticancer

treatment. Arch Pharm Res. 43:1144–1161. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lin DI, Barbash O, Kumar KGS, Weber JD,

Harper JW, Klein-Szanto AJP, Rustgi A, Fuchs SY and Diehl JA:

Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCF

(FBX4-alphaB crystallin) complex. Mol Cell. 24:355–366. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Liu P, Cong X, Liao S, Jia X, Wang X, Dai

W, Zhai L, Zhao L, Ji J, Ni D, et al: Global identification of

phospho-dependent SCF substrates reveals a FBXO22 phosphodegron and

an ERK-FBXO22-BAG3 axis in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ.

29:1–13. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shapira M, Kakiashvili E, Rosenberg T and

Hershko DD: The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin down-regulates the

expression of the ubiquitin ligase subunit Skp2 in breast cancer

cells. Breast Cancer Res. 8:R462006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tekcham DS, Chen D, Liu Y, Ling T, Zhang

Y, Chen H, Wang W, Otkur W, Qi H, Xia T, et al: F-box proteins and

cancer: An update from functional and regulatory mechanism to

therapeutic clinical prospects. Theranostics. 10:4150–4167. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Warren WG, Osborn M, Yates A, Wright K and

O'Sullivan SE: The emerging role of fatty acid binding protein 5

(FABP5) in cancers. Drug Discov Today. 28:1036282023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Mukherjee A, Chiang CY, Daifotis HA,

Nieman KM, Fahrmann JF, Lastra RR, Romero IL, Fiehn O and Lengyel

E: Adipocyte-induced FABP4 expression in ovarian cancer cells

promotes metastasis and mediates carboplatin resistance. Cancer

Res. 80:1748–1761. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sun X, Wang T, Guan ZR, Zhang C, Chen Y,

Jin J and Hua D: FBXO2, a novel marker for metastasis in human

gastric cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 495:2158–2164. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wei X, Bu J, Mo X, Lv B, Wang X and Hou B:

The prognostic significance of FBXO2 expression in colorectal

cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 11:5054–506. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ji J, Shen J, Xu Y, Xie M, Qian Q, Qiu T,

Shi W, Ren D, Ma J, Liu W and Liu B: FBXO2 targets glycosylated

SUN2 for ubiquitination and degradation to promote ovarian cancer

development. Cell Death Dis. 13:4422022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Che X, Jian F, Wang Y, Zhang J, Shen J,

Cheng Q, Wang X, Jia N and Feng W: FBXO2 promotes proliferation of

endometrial cancer by ubiquitin-mediated degradation of FBN1 in the

regulation of the cell cycle and the autophagy pathway. Front Cell

Dev Biol. 8:8432020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhao X, Guo W, Zou L and Hu B: FBXO2

modulates STAT3 signaling to regulate proliferation and

tumorigenicity of osteosarcoma cells. Cancer Cell Int. 20:2452020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Buehler M, Yi X, Ge W, Blattmann P,

Rushing E, Reifenberger G, Felsberg J, Yeh C, Corn JE, Regli L, et

al: Quantitative proteomic landscapes of primary and recurrent

glioblastoma reveal a protumorigeneic role for FBXO2-dependent

glioma-microenvironment interactions. Neuro Oncol. 25:290–302.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Guo W, Ren Y and Qiu X: FBXO2 promotes the

progression of papillary thyroid carcinoma through the p53 pathway.

Sci Rep. 14:225742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cheng J, Liu O, Bin X and Tang Z: FBXO2 as

a switch guides a special fate of tumor clones evolving into a

highly malignant transcriptional subtype in oral squamous cell

carcinoma. Apoptosis. 30:167–184. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hershko A, Heller H, Elias S and

Ciechanover A: Components of ubiquitin-protein ligase system.

Resolution, affinity purification, and role in protein breakdown. J

Biol Chem. 258:8206–8214. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lyu L, Chen Z and McCarty N: TRIM44 links

the UPS to SQSTM1/p62-dependent aggrephagy and removing misfolded

proteins. Autophagy. 18:783–798. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Paudel RR, Lu D, Chowdhury SR, Monroy EY

and Wang J: Targeted protein degradation via lysosomes.

Biochemistry. 62:564–579. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hershko A, Ciechanover A, Heller H, Haas

AL and Rose IA: Proposed role of ATP in protein breakdown:

Conjugation of protein with multiple chains of the polypeptide of

ATP-dependent proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 77:1783–1786.

1980. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hochstrasser M: Ubiquitin and

intracellular protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol.

4:1024–1031. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hochstrasser M: Ubiquitin-dependent

protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 30:405–439. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jacopo M: Unconventional protein secretion

(UPS): Role in important diseases. Mol Biomed. 4:22023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Aliabadi F, Sohrabi B, Mostafavi E,

Pazoki-Toroudi H and Webster TJ: Ubiquitin-proteasome system and

the role of its inhibitors in cancer therapy. Open Biol.

11:2003902021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Li W, Bengtson MH, Ulbrich A, Matsuda A,

Reddy VA, Orth A, Chanda SK, Batalov S and Joazeiro CA: Genome-wide

and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies

MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics

and signaling. PLoS One. 3:e14872008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xu C, Fan CD and Wang X: Regulation of

Mdm2 protein stability and the p53 response by NEDD4-1 E3 ligase.

Oncogene. 34:281–289. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huang X, Gu H, Zhang E, Chen Q, Cao W, Yan

H, Chen J, Yang L, Lv N, He J, et al: The NEDD4-1 E3 ubiquitin

ligase: A potential molecular target for bortezomib sensitivity in

multiple myeloma. Int J Cancer. 146:1963–1978. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shangary S and Wang S: Targeting the

MDM2-p53 interaction for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res.

14:5318–5324. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Fujii Y, Yada M, Nishiyama M, Kamura T,

Takahashi H, Tsunematsu R, Susaki E, Nakagawa T, Matsumoto A and

Nakayama KI: Fbxw7 contributes to tumor suppression by targeting

multiple proteins for ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Cancer Sci.

97:729–736. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Wan L, Chen M, Cao J, Dai X, Yin Q, Zhang

J, Song SJ, Lu Y, Liu J, Inuzuka H, et al: The APC/C E3 ligase

complex activator FZR1 restricts BRAF oncogenic function. Cancer

Discov. 7:424–441. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Huang HC, Shi J, Orth JD and Mitchison TJ:

Evidence that mitotic exit is a better cancer therapeutic target

than spindle assembly. Cancer Cell. 16:347–358. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Manchado E, Guillamot M, de Cárcer G,

Eguren M, Trickey M, García-Higuera I, Moreno S, Yamano H, Cañamero

M and Malumbres M: Targeting mitotic exit leads to tumor regression

in vivo: Modulation by Cdk1, Mastl, and the PP2A/B55α,δ

phosphatase. Cancer Cell. 18:641–654. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kidokoro T, Tanikawa C, Furukawa Y,

Katagiri T, Nakamura Y and Matsuda K: CDC20, a potential cancer

therapeutic target, is negatively regulated by p53. Oncogene.

27:1562–1571. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hadjihannas MV, Bernkopf DB, Brückner M

and Behrens J: Cell cycle control of Wnt/β-catenin signalling by

conductin/axin2 through CDC20. EMBO Rep. 13:347–354. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Liu PY, Xu N, Malyukova A, Scarlett CJ,

Sun YT, Zhang XD, Ling D, Su SP, Nelson C, Chang DK, et al: The

histone deacetylase SIRT2 stabilizes Myc oncoproteins. Cell Death

Differ. 20:503–514. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Huang ZJ, Zhu JJ, Yang XY and Biskup E:

NEDD4 promotes cell growth and migration via PTEN/PI3K/AKT

signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 14:2649–2656.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hayashi S, Ozaki T, Yoshida K, Hosoda M,

Todo S, Akiyama S and Nakagawara A: p73 and MDM2 confer the

resistance of epidermoid carcinoma to cisplatin by blocking p53.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 347:60–66. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Liu L, Wong CC, Gong B and Yu J:

Functional significance and therapeutic implication of ring-type E3

ligases in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 37:148–159. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lipkowitz S and Weissman AM: RINGs of good

and evil: RING finger ubiquitin ligases at the crossroads of tumour

suppression and oncogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:629–643. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang H, Lu X, Liu Z, Chen L, Xu Y, Wang Y,

Wei G and Chen Y: FBXW7 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal

transition, stemness and metastatic potential of cholangiocarcinoma

cells. Oncotarget. 6:6310–6325. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Mao JH, Perez-Losada J, Wu D, Delrosario

R, Tsunematsu R, Nakayama KI, Brown K, Bryson S and Balmain A:

Fbxw7/Cdc4 is a p53-dependent, haploinsufficient tumour suppressor

gene. Nature. 432:775–779. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Rajagopalan H, Jallepalli PV, Rago C,

Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B and Lengauer C:

Inactivation of hCDC4 can cause chromosomal instability. Nature.

428:77–81. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Grim JE, Knoblaugh SE, Guthrie KA, Hagar

A, Swanger J, Hespelt J, Delrow JJ, Small T, Grady WM, Nakayama KI

and Clurman BE: Fbw7 and p53 cooperatively suppress advanced and

chromosomally unstable intestinal cancer. Mol Cell Biol.

32:2160–2167. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Thompson LL, Rutherford KA, Lepage CC and

McManus KJ: The SCF complex is essential to maintain genome and

chromosome stability. Int J Mol Sci. 22:85442021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Uddin S, Bhat AA, Krishnankutty R, Mir F,

Kulinski M and Mohammad RM: Involvement of F-BOX proteins in

progression and development of human malignancies. Semin Cancer

Biol. 36:18–32. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Liu Y, Pan B, Qu W, Cao Y, Li J and Zhao

H: Systematic analysis of the expression and prognosis relevance of

FBXO family reveals the significance of FBXO1 in human breast

cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 21:1302021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Gao D, Inuzuka H, Tseng A, Chin RY, Toker

A and Wei W: Phosphorylation by Akt1 promotes cytoplasmic

localization of Skp2 and impairs APCCdh1-mediated Skp2 destruction.

Nat Cell Biol. 11:397–408. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Lin YW and Yang JL: Cooperation of ERK and

SCFSkp2 for MKP-1 destruction provides a positive feedback

regulation of proliferating signaling. J Biol Chem. 281:915–926.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zaytseva YY, Wang X, Southard RC, Wallis

NK and Kilgore MW: Down-regulation of PPARgamma1 suppresses cell

growth and induces apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Mol

Cancer. 7:902008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Lu Y, Zi X and Pollak M: Molecular

mechanisms underlying IGF-I-induced attenuation of the

growth-inhibitory activity of trastuzumab (Herceptin) on SKBR3

breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 108:334–341. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Asmamaw MD, Liu Y, Zheng YC, Shi XJ and

Liu HM: Skp2 in the ubiquitin-proteasome system: A comprehensive

review. Med Res Rev. 40:1920–1949. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Sistrunk C, Kim SH, Wang X, Lee SH, Kim Y,

Macias E and Rodriguez-Puebla ML: Skp2 deficiency inhibits chemical

skin tumorigenesis independent of p27(Kip1) accumulation. Am J

Pathol. 182:1854–1864. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Fuchs SY, Spiegelman VS and Kumar KGS: The

many faces of beta-TrCP E3 ubiquitin ligases: Reflections in the

magic mirror of cancer. Oncogene. 23:2028–2036. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Zhang J, Yang Z, Ou J, Xia X, Zhi F and

Cui J: The F-box protein FBXL18 promotes glioma progression by

promoting K63-linked ubiquitination of Akt. FEBS Lett. 591:145–154.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ji M, Zhao Z, Li Y, Xu P, Shi J, Li Z,

Wang K, Huang X and Liu B: FBXO6-mediated RNASET2 ubiquitination

and degradation governs the development of ovarian cancer. Cell

Death Dis. 12:3172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Ji M, Zhao Z, Li Y, Xu P, Shi J, Li Z,

Wang K, Huang X, Ji J, Liu W and Liu B: FBXO16-mediated hnRNPL

ubiquitination and degradation plays a tumor suppressor role in

ovarian cancer. Cell Death Dis. 12:7582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Wu J, Wen T, Marzio A, Song D, Chen S,

Yang C, Zhao F, Zhang B, Zhao G, Ferri A, et al: FBXO32-mediated

degradation of PTEN promotes lung adenocarcinoma progression. Cell

Death Dis. 15:2822024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Habel N, El-Hachem N, Soysouvanh F,

Hadhiri-Bzioueche H, Giuliano S, Nguyen S, Horák P, Gay AS, Debayle

D, Nottet N, et al: FBXO32 links ubiquitination to epigenetic

reprograming of D cells. Cell Death Differ. 28:1837–1848. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Fan J, Bellon M, Ju M, Zhao L, Wei M, Fu L

and Nicot C: Clinical significance of FBXW7 loss of function in

human cancers. Mol Cancer. 21:872022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Liu Z, Ma T, Duan J, Liu X and Liu L:

MicroRNA-223-induced inhibition of the FBXW7 gene affects the

proliferation and apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells via the

notch and akt/mTOR pathways. Mol Med Rep. 23:1542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Lee EK, Lian Z, D'Andrea K, Letrero R,

Sheng W, Liu S, Diehl JN, Pytel D, Barbash O, Schuchter L, et al:

The FBXO4 tumor suppressor functions as a barrier to

BRAFV600E-dependent metastatic melanoma. Mol Cell Biol.

33:4422–4433. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Lian Z, Lee EK, Bass AJ, Wong KK,

Klein-Szanto AJ, Rustgi AK and Diehl JA: FBXO4 loss facilitates

carcinogen induced papilloma development in mice. Cancer Biol Ther.

16:750–755. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Barbash O, Zamfirova P, Lin DI, Chen X,

Yang K, Nakagawa H, Lu F, Rustgi AK and Diehl JA: Mutations in Fbx4

inhibit dimerization of the SCF(Fbx4) ligase and contribute to

cyclin D1 overexpression in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 14:68–78.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Duan S, Cermak L, Pagan JK, Rossi M,

Martinengo C, di Celle PF, Chapuy B, Shipp M, Chiarle R and Pagano

M: FBXO11 targets BCL6 for degradation and is inactivated in

diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Nature. 481:90–93. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Santra MK, Wajapeyee N and Green MR: F-box

protein FBXO31 mediates cyclin D1 degradation to induce G1 arrest

after DNA damage. Nature. 459:722–725. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Zou S, Ma C, Yang F, Xu X, Jia J and Liu

Z: FBXO31 suppresses gastric cancer EMT by targeting snail1 for

proteasomal degradation. Mol Cancer Res. 16:286–295. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Malonia SK, Dutta P, Santra MK and Green

MR: F-box protein FBXO31 directs degradation of MDM2 to facilitate

p53-mediated growth arrest following genotoxic stress. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 112:8632–8637. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Liu J, Han L, Li B, Yang J, Huen MSY, Pan

X, Tsao SW and Cheung AL: F-box only protein 31 (FBXO31) negatively

regulates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling by

mediating lysine 48-linked ubiquitination and degradation of

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 6 (MKK6). J Biol Chem.

289:21508–21518. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Liu D, Xia H, Wang F, Chen C and Long J:

MicroRNA-210 interacts with FBXO31 to regulate cancer proliferation

cell cycle and migration in human breast cancer. OncoTargets Ther.

9:5245–5255. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Islam S, Dutta P, Sahay O, Gopalakrishnan

K, Muhury SR, Parameshwar P, Shetty P and Santra MK:

Feedback-regulated transcriptional repression of FBXO31 by c-myc

triggers ovarian cancer tumorigenesis. Int J Cancer. 150:1512–1524.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Ma Y, Sun WL, Ma SS, Zhao G, Liu Z, Lu Z

and Zhang D: LincRNA ZNF529-AS1 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma

via FBXO31 and predicts the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma

patients. BMC Bioinformatics. 24:542023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Duan S, Moro L, Qu R, Simoneschi D, Cho H,

Jiang S, Zhao H, Chang Q, de Stanchina E, Arbini AA and Pagano M:

Loss of FBXO31-mediated degradation of DUSP6 dysregulates ERK and

PI3K-AKT signaling and promotes prostate tumorigenesis. Cell Rep.

37:1098702021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Fang X, Zhou W, Wu Q, Huang Z, Shi Y, Yang

K, Chen C, Xie Q, Mack SC, Wang X, et al: Deubiquitinase USP13

maintains glioblastoma stem cells by antagonizing FBXL14-mediated

Myc ubiquitination. J Exp Med. 214:245–267. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Cui YH, Kim H, Lee M, Yi JM, Kim RK, Uddin

N, Yoo KC, Kang JH, Choi MY, Cha HJ, et al: FBXL14 abolishes breast

cancer progression by targeting CDCP1 for proteasomal degradation.

Oncogene. 37:5794–5809. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Yoshida Y, Chiba T, Tokunaga F, Kawasaki

H, Iwai K, Suzuki T, Ito Y, Matsuoka K, Yoshida M, Tanaka K and Tai