Introduction

Globally, colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading

oncological burden, positioned as the third most frequently

diagnosed malignancy and the second principal contributor to

cancer-associated mortality (1).

The World Health Organization estimated that in 2022, there were

>1.9 million new cases of CRC and 904,000 CRC-associated deaths

worldwide, with China accounting for ~30% of these cases (2). Projections indicate that by 2040, the

number of new cases and deaths to will increase to 3.2 million and

1.6 million, respectively, posing a notable public health challenge

(3). Despite 60% of patients being

diagnosed with resectable CRC, ~50% of those who undergo curative

surgery alone and 20–25% of those who receive adjuvant chemotherapy

experience cancer relapse, metastatic disease and eventual death

(4). This underscores the

inadequacy of current treatment options for this fatal

malignancy.

Due to the toxicity concerns and high costs

associated with modern therapies, there is an increasing interest

in discovering potential natural products (5,6).

Curcumin, one of the primary curcuminoids found in the root of the

Curcuma longa (turmeric) plant, has been extensively studied

in the treatment of a wide range of diseases, including CRC

(7). A phase IIa open-label

randomized controlled trial showed that adjuvant treatment with

curcumin significantly increased the objective response rate (53.3%

vs. 11.1%, P=0.039) and prolonged median survival time (502 vs. 200

days, P=0.02) compared with single chemotherapy (8). Additionally, incorporating curcumin

into standard chemotherapeutic regimens for metastatic CRC can help

reduce side effects, overcome chemotherapy resistance and

ultimately enhance the quality of life for patients (9). Due to the potential therapeutic

benefits, several other clinical trials have already been

registered and conducted, assessing curcumin either in combination

with chemotherapy or as a single agent for the prevention of colon

cancer (10–12).

Several studies have investigated and revealed the

potential mechanisms of curcumin in treating cancer, such as

inducing apoptosis and senescence, suppressing migration and

invasion (13), blocking the cell

cycle (14), activating

ferroptosis (15), regulating the

gut microbiota, and exerting anti-inflammatory and antioxidant

effects (16). However, the

underlying mechanisms of curcumin against CRC are still not fully

elucidated.

Pyroptosis, a form of inflammatory programmed cell

death that differs from apoptosis, has emerged as a focal area of

research due to its implications in various diseases, including CRC

(17). This process is primarily

triggered by inflammatory stimuli that activate caspases,

particularly caspase-1 (18),

which induces the formation of perforation-active gasdermin

(GSDM)D. Following proteolytic activation, the N-terminal of GSDMD

oligomerizes into transmembrane pores on the plasma membrane,

mediating: i) Non-selective ion flux causing osmotic imbalance and

cytolysis, and ii) regulated release of canonical inflammatory

mediators (IL-1β and IL-18); these collectively execute the

terminal phase of pyroptotic cell death (19).

Investigative findings have revealed that malignant

cells demonstrate heightened pyroptotic susceptibility compared

with normal cells (20).

Pyroptosis has demonstrated notable antitumor potential in

controlling cancer progression, including in CRC (17). A previous study reported that

caspase-1 activation could mediate a ‘cold’ to ‘hot’ transformation

of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in CRC (21). By contrast, Fusobacterium

nucleatum could inhibit the caspase-3/GSDME pyroptosis-related

pathway induced by chemotherapy drugs, thereby mediating CRC cell

chemo-resistance (22).

Consequently, pyroptosis induction could serve as a dual-function

mechanism for both tumor suppression and therapeutic intervention

in CRC.

Given the increasing incidence of CRC, the

development of targeted therapeutic interventions is of paramount

importance. The diverse mechanisms of curcumin, particularly its

role in inducing caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis, warrant further

investigation as a potential therapeutic strategy for CRC. The

present study aimed to elucidate the mechanisms through which

curcumin modulates caspase-1 activity and its impact on pyroptosis

in CRC cells, thereby advancing the understanding of CRC and the

therapeutic potential of natural compounds.

Materials and methods

Materials

The human CRC cell lines HCT-116 and SW480 (cat.

nos. SCSP-5076 and SCSP-5033) were acquired from The Cell Bank of

Type Culture Collection of The Chinese Academy of Sciences. For

comparative analysis, the normal colon epithelial cell line FHC was

procured from the American Type Culture Collection (cat. no.

CRL-1831). Cell culture media components including RPMI 1640, DMEM

and fetal bovine serum (FBS) (cat. nos. 11875093, 12491015 and

A5670501) were commercially obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc. Apoptosis detection reagents (In Situ Cell Death

Detection Kit) were sourced from Roche Diagnostics (cat. no.

11684795910). The caspase-1 inhibitor VX-765 was supplied by

MedChemExpress (cat. no. HY-13205). Western blot analysis employed

specific antibodies targeting caspase-1/3 (both precursor and

cleaved forms), IL-1β, IL-18, GSDMD and nucleotide-binding

oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor protein (NLRP)3

inflammasome components (cat. nos. ab138483, ab184787, ab2302,

ab283818, ab207323, ab209845 and ab263899; Abcam; cat. no.

HY-P80622; MedChemExpress). All the materials were maintained under

manufacturer-specified storage conditions.

Cell culture and experimentation

SW480 and HCT116 cell lines were propagated in RPMI

1640 medium containing 10% FBS, whereas FHC cells were cultured in

DMEM with equivalent serum supplementation. All cell populations

were maintained under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5%

CO2). For experimental interventions, both SW480 and

HCT116 cells were stratified into four treatment cohorts: i)

Curcumin monotherapy (10 µM), ii) caspase-1 inhibitor VX-765 (10 µM

for SW480; 20 µM for HCT116) (23), iii) combination therapy with

curcumin (10 µM) and VX-765 (20 µM), and iv) untreated control

group. Pharmacological treatments were administered following

established dosing protocols for 48 h at 37°C with 5%

CO2.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was quantitatively assessed using the

CCK-8 colorimetric assay (cat. no. CK04-20; Dojindo Laboratories,

Inc.) to evaluate curcumin-induced cytotoxicity. Specifically,

exponentially growing cells were plated in 96-well culture plates

at a standardized density of 5×103 cells/well. After 24

h adherence, cells were exposed to curcumin (cat. no. C1386;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) dissolved in DMSO, with concentrations

titrated from 0 to 200 µM. Following 48 h pharmacological exposure,

10 µl CCK-8 detection reagent was administered per well and

incubated for 2 h at 37°C, followed by optical density

quantification using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy H1;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.) at 450 nm with a reference wavelength

of 650 nm. Experimental design incorporated triplicate technical

replicates across three independent biological experiments.

Cell migration and invasion

assays

Cell migration under curcumin treatment was assessed

via scratch assay. Cells (5×105/well) in 12-well plates

were cultured to 95% confluence in medium containing 10% FBS.

Uniform wounds were created using sterile pipette tips, washed with

serum-free medium, and then cultured in serum-free medium at 37°C.

Images were captured at 0 and 48 h using phase-contrast microscopy

to monitor closure (Leica DMi8; Leica Microsystems, Inc.). Wound

closure was quantified using Digimizer software v4.5.1 (MedCalc

Software Ltd.) with migration rate (%) calculated as: (Initial

width-final width)/initial width ×100. Triplicate experiments were

performed.

Invasion assays utilized 24-well Transwell plates

pre-coated with Matrigel at 37°C for 1 h (pore size, 8 µm; BD

Biosciences). A total of 1×105 cells in serum-deprived

medium were introduced into the upper chamber, with 500 µl medium

containing 10% FBS placed in the lower chamber. After 48 h

incubation at 37°C, invasive cells retained on the membrane were

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with 0.5% (w/v) crystal

violet for 20 min, whereas non-invasive cells were removed with a

cotton swab. Three random microscopic fields per well were

quantified for statistical analysis.

Microscopy

Pyroptotic cellular dynamics were investigated using

24-well culture systems with an initial seeding density of

5×104 cells/well. Morphological evaluation was performed

through bright-field imaging (Olympus IX53; Olympus Corporation)

following experimental interventions.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

assay

Pyroptotic cell death was quantitatively assessed

through LDH release analysis (cat. no. EL-H0866; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). Culture supernatants collected

post-treatment were centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and

the clarified supernatants processed for LDH quantification

according to the manufacturer protocols, with absorbance measured

at 490 nm using a microplate reader.

TUNEL staining

Apoptotic nuclei were detected via TUNEL assay

(In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit). Cells seeded at

2×104 cells/well on sterilized coverslips were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C for 30 min, grown on coverslips,

permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100/0.1% sodium citrate solution

at room temperature (RT) for 10 min and subsequently incubated with

TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h. Nuclear counterstaining was

achieved with DAPI (1 µg/ml; at RT for 5 min). Samples were mounted

with ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant (cat. no. P36930;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and imaged using a Zeiss Axio

Observer fluorescence microscope. Quantitative analysis was

performed on ≥3 random fields per sample (×200 magnification). All

procedures strictly followed manufacturer-specified protocols,

including negative controls processed without terminal

transferase.

Western blotting

Cellular proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer

(cat. no. 89900; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and quantified via

the BCA assay. Equal aliquots (30 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on

12% gels and were transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking

with 5% BSA at RT for 1 h (cat. no. E-IR-R107; Wuhan Elabscience

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), the membranes were incubated with primary

antibodies (1:500 for caspase-1, cleaved-caspase-1 and

cleaved-caspase-3; 1:2,000 for caspase-3; 1:1,000 for IL-1β, IL-18,

GSDMD and NLRP3) at 4°C for 16 h, and then with HRP-conjugated

rabbit anti-rat IgG(H+L) secondary antibody (1:5,000; cat. no.

ab6734; Abcam) at RT for 2 h. β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no. ab20272;

Abcam) was used as the internal control. Protein bands were

visualized using ECL reagent (cat. no. E422-01; Vazyme Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) with chemiluminescent detection.

Immunofluorescence staining

HCT116 and SW480 cells (2×104 cells/well)

were seeded in 24-well plates containing round coverslips and fixed

in 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 15 min. The cells were then

membrane-permeabilized by incubation in 0.1% Triton-X 100 (cat. no.

T9284; MilliporeSigma), followed by blocking with 5% BSA (cat. no.

E-IR-R107; Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 1 h at

RT. Cells were incubated with primary antibody (GSDMD: 1:500, cat.

no. HY-P85810; caspase-1: 1:500, cat. no. HY-P81232;

MedChemExpress) at 4°C for 16 h, and incubation with goat

anti-mouse IgG H&L Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody (cat. no.

ab150117; Abcam) at RT for 1 h. Fluorescence signals were captured

using confocal microscopy (Leica SP8; Leica Microsystems, Inc.)

with DAPI nuclear counterstaining for 24 h at RT for signal

normalization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 9.4.1 software (Dotmatics). All experiments were repeated

three times. Quantitative data are presented as the median (IQR).

All continuous variables were formally tested for normality using

the Shapiro-Wilk test (α=0.05). Due to the small sample size (only

in vitro experiments were performed), non-parametric

analysis was conducted through Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn's post hoc

test for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

Determination of curcumin

concentration

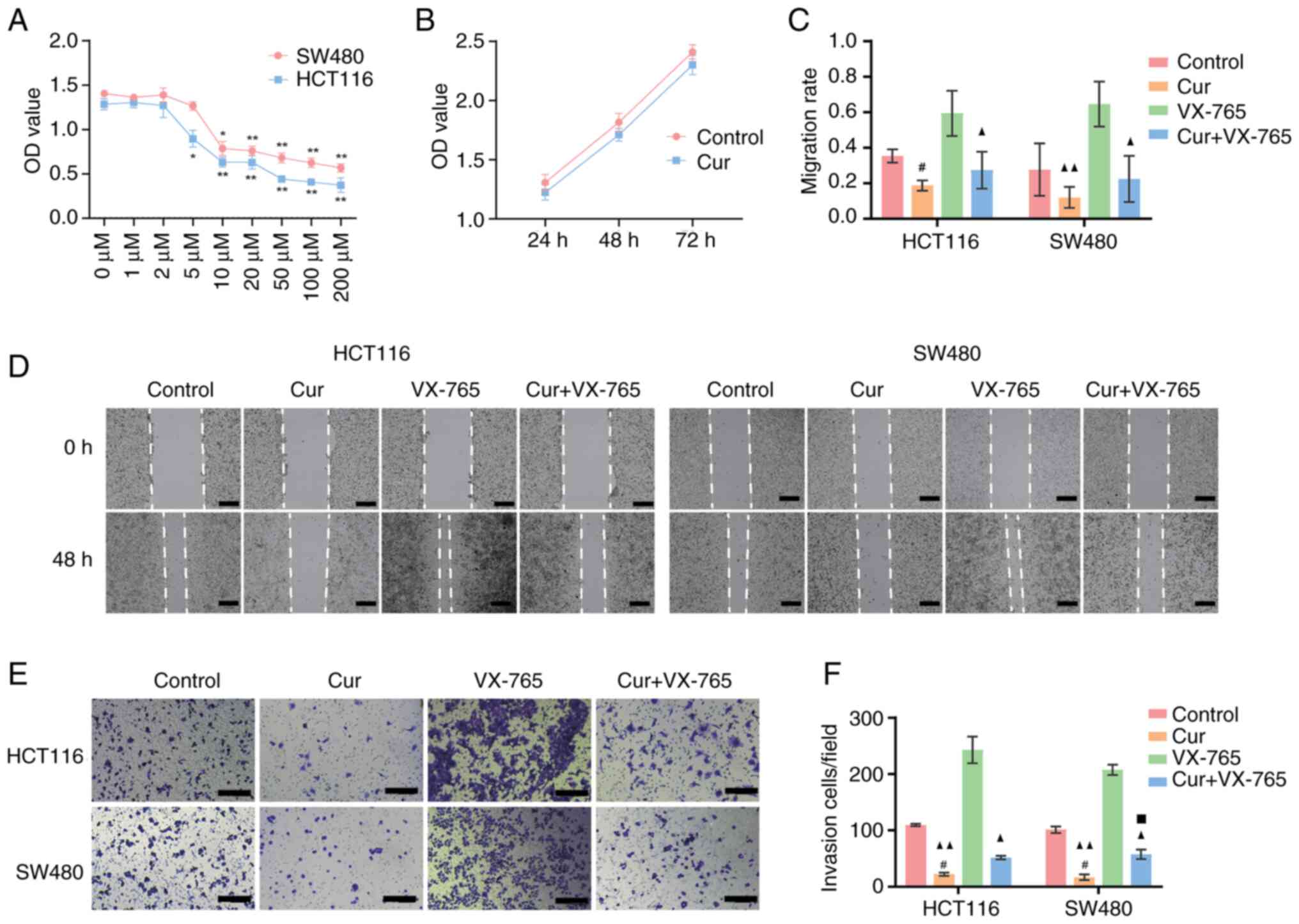

To determine the optimal dosage of curcumin, CRC

cell lines HCT-116 and SW480 were treated with curcumin at

concentrations ranging from 0 to 200 µM, and cell viability was

assessed using CCK-8 assays. As shown in Fig. 1A, curcumin reduced cell viability

in a dose-dependent manner. In response to 10 µM curcumin, both

cell lines exhibited statistically significant differences

(compared with 0 µM). Additionally, the cell viability assay

revealed no effect on FHC normal colon epithelial cells in response

to this concentration of curcumin for 72 h (Fig. 1B). Therefore, 10 µM curcumin was

selected for subsequent experiments.

Curcumin inhibits cell migration and

invasion

The migratory ability of CRC cell lines was assessed

using a wound healing assay. Cells were cultured in maintenance

medium for 48 h, and the scratch distance was measured for each

cell line. Curcumin treatment significantly reduced the extent of

wound closure and the migration rate (Fig. 1C and D). The effect of curcumin on

invasive capability was evaluated using a Matrigel-coated Transwell

system. As shown in Fig. 1E and F,

curcumin treatment significantly reduced the number of invasive

HCT-116 and SW480 cells compared with those in the control group.

These results demonstrated that curcumin may inhibit autonomous

migration and invasion in CRC cells.

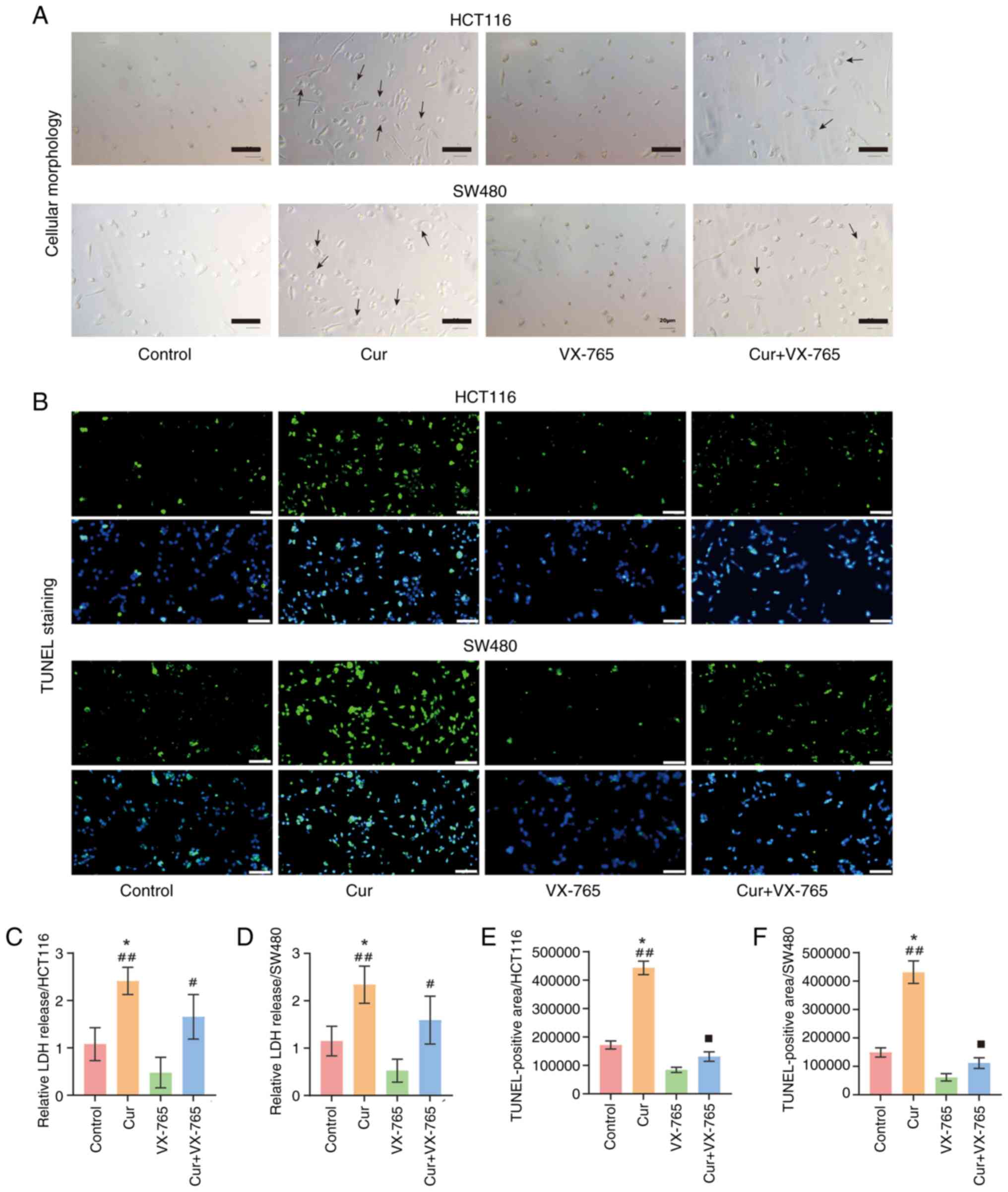

Curcumin induces pyroptosis in CRC

cells

To assess cellular morphology, CRC cells were

examined under a microscope. Fig.

2A demonstrated that curcumin-treated cells manifested

characteristic pyroptotic morphology, including membrane swelling

and subsequent rupture with cytoplasmic content release. TUNEL

staining was then performed to assess cell death. The results

demonstrated that curcumin significantly increased cell death

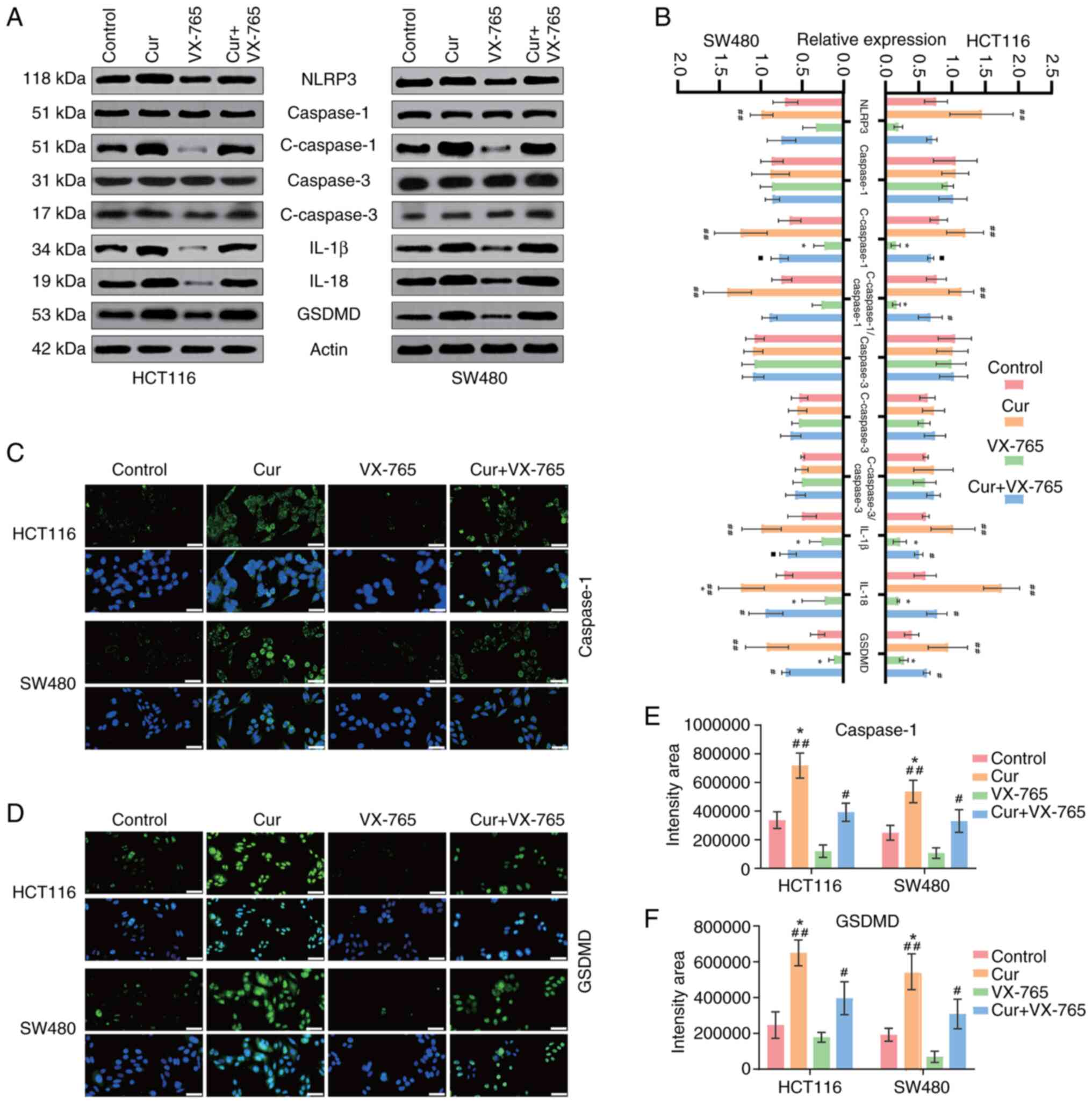

(Fig. 2B, E and F). Caspase-3, an

apoptosis-specific marker, was detected to distinguish between

pyroptosis and apoptosis. The results indicated that curcumin could

slightly increase cleaved-caspase-3 expression; however, this was

not significantly different (Fig. 3A

and B). Furthermore, cell membrane integrity is a key indicator

of pyroptosis. Therefore, LDH levels in the cell supernatant and

GSDMD expression were measured. The results indicated that

curcumin-treated cells exhibited elevated LDH levels (Fig. 2C and D) and increased GSDMD

expression (Fig. 3A, B and D).

Furthermore, the expression levels of pyroptosis-related factors,

including caspase-1, its upstream marker NLRP3, and the downstream

markers IL-18 and IL-1β, were analyzed (Fig. 3A-C and E). The results indicated

that curcumin significantly upregulated the expression of

pyroptosis-related proteins, suggesting that pyroptosis may

contribute to the anti-CRC effects of curcumin.

Curcumin induces pyroptosis by

activating the caspase-1 signal

To evaluate the role of the caspase-1 signaling

pathway in curcumin-induced pyroptosis, VX-765, a selective

caspase-1 inhibitor, was used as a negative control. VX-765

markedly attenuated abnormal cellular morphological changes and

cell death induced by curcumin (Fig.

2A and B). Additionally, the expression levels of caspase-1 and

the downstream factors IL-1β and IL-18 were significantly lower in

the curcumin + VX-765 group compared with those in the

curcumin-only group (Fig. 3A-C and

E). Meanwhile, reduced LDH levels and GSDMD expression

indicated that VX-765 attenuated curcumin-induced perforation

(Figs. 2C and D, and 3A, B, D and F).

Additionally, curcumin markedly reduced the

migratory capability of HCT116 and SW480 cells; however, the

inhibitory effect on migration was arrested when cells were

co-treated with curcumin and VX-765 (Fig. 1C and D). Similarly, the invasive

ability of CRC cells was significantly higher in the presence of

VX-765 compared with curcumin alone (Fig. 1E and F). These findings suggested

that curcumin inhibits CRC growth and metastasis by inducing

caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that curcumin may

exert antitumor effects on CRC cells, primarily through the

induction of caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis. The data revealed that

curcumin treatment not only suppressed tumor cell viability,

migration and invasion in a dose-dependent manner, but also

triggered pyroptosis, a lytic and immunogenic form of programmed

cell death distinct from apoptosis. This finding aligns with the

established literature indicating the ability of curcumin to engage

multiple cell death pathways in cancer, reinforcing its potential

as a therapeutic agent for CRC (24–26).

CRC remains a major global health burden and a

leading cause of cancer-related mortality. While notable advances

have been made in cancer immunotherapy, efforts continue to

identify strategies that elicit robust and sustained antitumor

immunity (27). Accumulating

evidence has indicated that specific regulated cell death

modalities, including pyroptosis, can function as potent

immunogenic switches. This occurs through the systemic release of

damage-associated molecular patterns and tumor-associated antigens,

which subsequently prime and activate antitumor immune responses

(28). Leveraging the inherent

immunogenicity of dying tumor cells thus represents a promising

avenue for enhancing immunotherapy efficacy. Pyroptosis,

classically recognized as a host defense mechanism against

pathogens, elicits a strong inflammatory response and activates

innate immunity (29). Critically,

pyroptosis-induced immunogenic cell death can transform

immunologically ‘cold’ tumors into ‘hot’ T cell-inflamed

microenvironments, establishing a dual-phase tumor suppressive

mechanism involving both primary tumor regression and disruption of

metastatic niches (30).

Consequently, strategies combining pyroptosis induction with

conventional anticancer therapies represent a viable treatment

approach (31).

The critical role of pyroptosis in CRC pathogenesis

and therapy is increasingly being recognized. Clinical studies have

reported dysregulation of inflammasome components, such as NLRP1,

NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family caspase recruitment

domain-containing protein (NLRC)4 and absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2),

in patients with CRC (32), with

several inflammasomes (NLRP1, NLRP6, AIM2, pyrin and NLRC4)

demonstrating anti-tumorigenic function (33). Pharmacological enhancement of NLRP3

activity, combined with chemotherapeutics such as 5-fluorouracil or

regorafenib, can effectively induce pyroptosis and suppress tumor

growth in preclinical CRC models (34). Inflammasome-regulated release of

IL-18 and IL-1β by immune cells within the TME holds therapeutic

potential by promoting inflammation and immune activation (31). For example, NLRP3-mediated

IL-18/IL-1β production enhances natural killer cell maturation and

cytotoxicity, thereby inhibiting CRC liver metastasis (35). Clinically, downregulated GSDMD

expression is associated with a poor prognosis in CRC (36), while cytoplasmic/nuclear GSDMB

expression may predict benefit from 5-fluorouracil-based

chemotherapy (37). Furthermore,

inducing pyroptosis via other mechanisms, such as

caspase-3-mediated GSDME cleavage during photodynamic therapy, can

sensitize microsatellite stable CRC cells to PD-1 blockade

(38). Targeted induction of

GSDMD-dependent pyroptosis has also shown efficacy in inhibiting

metastatic CRC (39).

The present mechanistic investigation revealed that

curcumin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in CRC cells, leading to

the upregulation of key pyroptosis executioner proteins caspase-1

and GSDMD. This cascade consequently promotes the maturation and

release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β.

Morphologically, curcumin-treated CRC cells exhibited

characteristic features of pyroptosis, including cellular swelling,

plasma membrane ballooning with protruding vesicles, and eventual

rupture leading to cytoplasmic content release. Crucially, the

specific caspase-1 inhibitor VX-765 significantly attenuated

curcumin-induced cell death and associated molecular changes,

strongly supporting the central role of caspase-1-mediated

pyroptosis in the anti-CRC effects of curcumin.

Several studies have explored the antitumor effects

of curcumin via pyroptosis. In non-small cell lung cancer cells,

curcumin inhibits ubiquitin ligase Smurf2 activity, promoting

NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis (40).

In mouse breast cancer 4T1 cells, curcumin induces Ca2+

overload, effectively triggering caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated

pyroptosis to suppress tumors (41). In U937 leukemia cells, curcumin

upregulates AIM2, IFI16 and NLRC4 inflammasomes, activating

caspase-1, cleaving GSDMD and inducing pyroptosis (42). However, evidence in CRC remains

limited. Prior research indicates that curcumin induces programmed

cell death and upregulates the NLRP3 inflammasome in CRC cells;

however, the underlying mechanism remains unresolved (26). The present findings established

curcumin as a potent inducer of caspase-1/GSDMD-dependent

pyroptosis in CRC cells, advancing this evidence base.

Notably, curcumin exhibits a cell type-dependent

duality in modulating pyroptosis, acting as both an inducer and

suppressor. In non-cancerous settings, such as models of

fenpropathrin-induced nephrotoxicity (39), aflatoxin B1-induced hepatotoxicity

(43) and intestinal inflammation

(44), curcumin protects tissues

by suppressing pyroptosis, often through downregulating NLRP3,

caspase-1, GSDMD and associated cytokines. Conversely, in various

cancer cell types, including leukemia (42), hepatocellular carcinoma (45), and as demonstrated in the present

study and in a previous study on CRC (26), curcumin consistently promotes

pyroptosis as a key antitumor mechanism. This pro-pyroptotic effect

in CRC extends beyond direct tumor cell killing; curcumin-induced

pyroptosis can also repolarize tumor-associated macrophages towards

the immunostimulatory M1 phenotype, counteracting TME

immunosuppression and enhancing overall antitumor efficacy

(46). This cell-type-specific

duality is not unique to pyroptosis, as similar contrasting effects

of curcumin have been observed in ferroptosis (47).

Despite these notable findings, several limitations

warrant attention in future studies. Firstly, the current

conclusions are based solely on in vitro cell line models.

Validation in in vivo animal models of CRC is essential to

confirm the antitumor efficacy of curcumin and its ability to

induce pyroptosis within the complex TME. Secondly, while

pharmacological inhibition with VX-765 strongly implicates

caspase-1, definitive genetic validation is needed. Employing

caspase-1 silencing (such as via small interfering RNA or short

hairpin RNA) or overexpression in CRC cells, coupled with studies

utilizing caspase-1-deficient transgenic animal models, would

provide more conclusive evidence for its indispensable role in

curcumin-induced pyroptosis. Additionally, alternative pathways

(such as non-canonical inflammasome activation or other

GSDM-dependent mechanisms) may concurrently mediate this process,

warranting systematic exploration in future studies.

In conclusion, the current study uncovered a novel

mechanism of curcumin in CRC treatment. By activating the caspase-1

pathway, curcumin may induce pyroptosis, and inhibit migration and

invasion in CRC cells, thereby exerting an anti-CRC effect.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82004333 and 82205033), the Natural

Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LQ21H290002),

the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine Science

and Technology Department-Zhejiang Provincial Administration of

Traditional Chinese Medicine Co-construction of Key Laboratory of

Research on Prevention and Treatment for Depression Syndrome (grant

no. GZY-ZJ-SY-2402), and the Zhejiang Traditional Chinese Medicine

Science and Technology Project (grant nos. 2022ZA044 and

2023ZR005).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JZ and LY contributed equally to this work and

shared the first authorship. JZ conceived the study, carried out

the investigation, administered the project, validated the results

and acquired funding. LY conceived and designed the study,

administered the project and wrote the main manuscript text. ZF and

JC carried out the investigation, and performed data collection and

statistical analysis. YW and HL conducted the formal analysis and

visualization using GraphPad Prism. SL conceived the study, and

contributed to writing, reviewing and editing the manuscript. BF

conceived and supervised the study, validated the results and

acquired funding. JZ and BF confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

AIM2

|

absent in melanoma 2

|

|

CRC

|

colorectal cancer

|

|

FBS

|

fetal bovine serum

|

|

GSDM

|

gasdermin

|

|

LDH

|

lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

NOD

|

nucleotide-binding oligomerization

domain

|

|

NLRP

|

NOD-like receptor protein

|

|

NLRC

|

NOD-like receptor family caspase

recruitment domain-containing protein

|

|

TME

|

tumor microenvironment

|

References

|

1

|

Hossain MS, Karuniawati H, Jairoun AA,

Urbi Z, Ooi J, John A, Lim YC, Kibria KMK, Mohiuddin AKM, Ming LC,

et al: Colorectal cancer: A review of carcinogenesis, global

epidemiology, current challenges, risk factors, preventive and

treatment strategies. Cancers (Basel). 14:17322022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263.

2024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V,

Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N and Bray F:

Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and

mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 72:338–344. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Weng W and Goel A: Curcumin and colorectal

cancer: An update and current perspective on this natural medicine.

Semin Cancer Biol. 80:73–86. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhang Y and Xie J: Targeting ferroptosis

regulators by natural products in colorectal cancer. Front

Pharmacol. 15:13747222024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Su Z, Li Y, Zhou Z, Feng B, Chen H and

Zheng G: Herbal medicine for colorectal cancer treatment: Molecular

mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Prolif. Jun 9–2025.(Epub

ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Neira M, Mena C, Torres K and Simón L: The

potential benefits of curcumin-enriched diets for adults with

colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Antioxidants (Basel).

14:3882025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Howells LM, Iwuji COO, Irving GRB, Barber

S, Walter H, Sidat Z, Griffin-Teall N, Singh R, Foreman N, Patel

SR, et al: Curcumin combined with FOLFOX chemotherapy is safe and

tolerable in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in a

randomized phase IIa trial. J Nutr. 149:1133–1139. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Layos L, Martínez-Balibrea E and Ruiz de

Porras V: Curcumin: A novel way to improve quality of life for

colorectal cancer patients? Int J Mol Sci. 23:140582022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang J, Wu Y, Tian Y, Xu H, Lin ZX and

Xian YF: Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of intestinal

cancer: Preclinical studies and potential clinical applications.

Mol Cancer. 23:2172024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gilad O, Rosner G, Ivancovsky-Wajcman D,

Zur R, Rosin-Arbesfeld R, Gluck N, Strul H, Lehavi D, Rolfe V and

Kariv R: Efficacy of wholistic turmeric supplement on adenomatous

polyps in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis-a

randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Genes

(Basel). 13:21822022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Panahi Y, Saberi-Karimian M, Valizadeh O,

Behnam B, Saadat A, Jamialahmadi T, Majeed M and Sahebkar A:

Effects of curcuminoids on systemic inflammation and quality of

life in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing chemotherapy: A

randomized controlled trial. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1328:1–9. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu C, Rokavec M, Huang Z and Hermeking H:

Curcumin activates a ROS/KEAP1/NRF2/miR-34a/b/c cascade to suppress

colorectal cancer metastasis. Cell Death Differ. 30:1771–1785.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wu Y, Han Y, Zhao NN and Zhao XF: Curcumin

exerts therapeutic effects on colorectal cancer by blocking the

cell cycle and regulating apoptosis. Asian J Surg. Aug

28–2024.(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

15

|

Miyazaki K, Xu C, Shimada M and Goel A:

Curcumin and andrographis exhibit anti-tumor effects in colorectal

cancer via activation of ferroptosis and dual suppression of

glutathione peroxidase-4 and ferroptosis suppressor protein-1.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 16:3832023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ojo OA, Adeyemo TR, Rotimi D, Batiha GE,

Mostafa-Hedeab G, Iyobhebhe ME, Elebiyo TC, Atunwa B, Ojo AB, Lima

CMG and Conte-Junior CA: Anticancer properties of curcumin against

colorectal cancer: A review. Front Oncol. 12:8816412022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fang Q, Xu Y, Tan X, Wu X, Li S, Yuan J,

Chen X, Huang Q, Fu K and Xiao S: The role and therapeutic

potential of pyroptosis in colorectal cancer: A review.

Biomolecules. 14:8742024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Pang Q, Wang P, Pan Y, Dong X, Zhou T,

Song X and Zhang A: Irisin protects against vascular calcification

by activating autophagy and inhibiting NLRP3-mediated vascular

smooth muscle cell pyroptosis in chronic kidney disease. Cell Death

Dis. 13:2832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Min R, Bai Y, Wang NR and Liu X:

Gasdermins in pyroptosis, inflammation, and cancer. Trends Mol Med.

Apr 29–2025.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cheng MZ, Yang BB, Zhan ZT, Lin SM, Fang

ZP, Gao Y and Zhou WJ: MACC1 and gasdermin-E (GSDME) regulate the

resistance of colorectal cancer cells to irinotecan. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 671:236–245. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Chen Q, Peng B, Lin L, Chen J, Jiang Z,

Luo Y, Huang L, Li J, Peng Y, Wu J, et al: Chondroitin

sulfate-modified hydroxyapatite for caspase-1 activated induced

pyroptosis through Ca overload/ER stress/STING/IRF3 pathway in

colorectal cancer. Small. 20:e24032012024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang N, Zhang L, Leng XX, Xie YL, Kang ZR,

Zhao LC, Song LH, Zhou CB and Fang JY: Fusobacterium

nucleatum induces chemoresistance in colorectal cancer by

inhibiting pyroptosis via the Hippo pathway. Gut Microbes.

16:23337902024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tang Z, Ji L, Han M, Xie J, Zhong F, Zhang

X, Su Q, Yang Z, Liu Z, Gao H and Jiang G: Pyroptosis is involved

in the inhibitory effect of FL118 on growth and metastasis in

colorectal cancer. Life Sci. 257:1180652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Brockmueller A, Ruiz de Porras V and

Shakibaei M: Curcumin and its anti-colorectal cancer potential:

From mechanisms of action to autophagy. Phytother Res.

38:3525–3551. 2024. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Zhou H, Zhuang Y, Liang Y, Chen H, Qiu W,

Xu H and Zhou H: Curcumin exerts anti-tumor activity in colorectal

cancer via gut microbiota-mediated CD8+ T Cell tumor

infiltration and ferroptosis. Food Funct. 16:3671–3693. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Dal Z and Aru B: The role of curcumin on

apoptosis and NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis on colorectal

cancer in vitro. Turk J Med Sci. 53:883–893. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Galluzzi L, Humeau J, Buqué A, Zitvogel L

and Kroemer G: Immunostimulation with chemotherapy in the era of

immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 17:725–741. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang X, Tang B, Luo J, Yang Y, Weng Q,

Fang S, Zhao Z, Tu J, Chen M and Ji J: Cuproptosis, ferroptosis and

PANoptosis in tumor immune microenvironment remodeling and

immunotherapy: Culprits or new hope. Mol Cancer. 23:2552024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Du T, Gao J, Li P, Wang Y, Qi Q, Liu X, Li

J, Wang C and Du L: Pyroptosis, metabolism, and tumor immune

microenvironment. Clin Transl Med. 11:e4922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wang M, Yu F, Zhang Y and Li P: Programmed

cell death in tumor immunity: Mechanistic insights and clinical

implications. Front Immunol. 14:13096352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Chen Q, Sun Y, Wang S and Xu J: New

prospects of cancer therapy based on pyroptosis and pyroptosis

inducers. Apoptosis. 29:66–85. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Liu R, Truax AD, Chen L, Hu P, Li Z, Chen

J, Song C, Chen L and Ting JP: Expression profile of innate immune

receptors, NLRs and AIM2, in human colorectal cancer: Correlation

with cancer stages and inflammasome components. Oncotarget.

6:33456–69. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sharma BR and Kanneganti TD: Inflammasome

signaling in colorectal cancer. Transl Res. 252:45–52. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Guan X, Liu R, Wang B, Xiong R, Cui L,

Liao Y, Ruan Y, Fang L, Lu X, Yu X, et al: Inhibition of HDAC2

sensitises antitumour therapy by promoting NLRP3/GSDMD-mediated

pyroptosis in colorectal cancer. Clin Transl Med. 14:e16922024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Sun Y, Hu H, Liu Z, Xu J, Gao Y, Zhan X,

Zhou S, Zhong W, Wu D, Wang P, et al: Macrophage STING signaling

promotes NK cell to suppress colorectal cancer liver metastasis via

4-1BBL/4-1BB co-stimulation. J Immunother Cancer. 11:e0064812023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wu LS, Liu Y, Wang XW, Xu B, Lin YL, Song

Y, Dong Y, Liu JL, Wang XJ, Liu S, et al: LPS enhances the

chemosensitivity of oxaliplatin in HT29 cells via GSDMD-mediated

pyroptosis. Cancer Manag Res. 12:10397–10409. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Sun L, Wang J, Li Y, Kang Y, Jiang Y,

Zhang J, Qian S and Xu F: Correlation of gasdermin B staining

patterns with prognosis, progression, and immune response in

colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 24:5672024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhou Y, Zhang W, Wang B, Wang P, Li D, Cao

T, Zhang D, Han H, Bai M, Wang X, et al: Mitochondria-targeted

photodynamic therapy triggers GSDME-mediated pyroptosis and

sensitizes anti-PD-1 therapy in colorectal cancer. J Immunother

Cancer. 12:e0080542024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sala R, Rioja-Blanco E, Serna N,

Sánchez-García L, Álamo P, Alba-Castellón L, Casanova I,

López-Pousa A, Unzueta U, Céspedes MV, et al: GSDMD-dependent

pyroptotic induction by a multivalent CXCR4-targeted nanotoxin

blocks colorectal cancer metastases. Drug Deliv. 29:1384–1397.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Xi Y, Zeng S, Tan X and Deng X: Curcumin

inhibits the activity of ubiquitin ligase Smurf2 to promote

NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Int

J Oncol. 66:212025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Li L, Xing Z, Wang J, Guo Y, Wu X, Ma Y,

Xu Z, Kuang Y, Liao T and Li C: Hyaluronic acid-mediated targeted

nano-modulators for activation of pyroptosis for cancer therapy

through multichannel regulation of Ca2+ overload. Int J

Biol Macromol. 299:1401162025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhou Y, Kong Y, Jiang M, Kuang L, Wan J,

Liu S, Zhang Q, Yu K, Li N, Le A and Zhang Z: Curcumin activates

NLRC4, AIM2, and IFI16 inflammasomes and induces pyroptosis by

up-regulated ISG3 transcript factor in acute myeloid leukemia cell

lines. Cancer Biol Ther. 23:328–335. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhang Y, Wang Y, Yang Y, Zhao D, Liu R, Li

S and Zhang X: Proteomic analysis of ITPR2 as a new therapeutic

target for curcumin protection against AFB1-induced pyroptosis.

Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 260:1150732023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Pan H, Hu T, He Y, Zhong G, Wu S, Jiang X,

Rao G, You Y, Ruan Z, Tang Z and Hu L: Curcumin attenuates

aflatoxin B1-induced ileum injury in ducks by inhibiting NLRP3

inflammasome and regulating TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mycotoxin

Res. 40:255–268. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Liang WF, Gong YX, Li HF, Sun FL, Li WL,

Chen DQ, Xie DP, Ren CX, Guo XY, Wang ZY, et al: Curcumin activates

ROS signaling to promote pyroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma

HepG2 cells. In Vivo. 35:249–257. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Cheng F, He L, Wang J, Lai L, Ma L, Qu K,

Yang Z, Wang X, Zhao R, Weng L and Wang L: Synergistic

immunotherapy with a calcium-based nanoinducer: Evoking pyroptosis

and remodeling tumor-associated macrophages for enhanced antitumor

immune response. Nanoscale. 16:18570–18583. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Foroutan Z, Butler AE, Zengin G and

Sahebkar A: Curcumin and ferroptosis: A promising target for

disease prevention and treatment. Cell Biochem Biophys. 82:343–349.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|