Introduction

Sepsis is characterized by life-threatening organ

dysfunction resulting from an aberrant host response to infection

(1). Gastrointestinal injury (GI)

is prevalent among individuals with sepsis and has been linked to

increased mortality rates (2). In

2017 alone, an estimated global sepsis incidence was 48.9 million

cases (3). GI complications can

stem from either underlying causes of sepsis, such as peritonitis

originating from the abdominal cavity, or systemic pro-inflammatory

responses seen in cases of sepsis and septic shock (4). A potential explanation for GI disease

in sepsis could be attributed to disruptions in bowel peristalsis

due to extensive use of sedatives and prolonged mechanical

ventilation. The pathology of sepsis involves a complex interplay

between different biological systems that results in severe

dysregulation of the inflammatory network (5). Despite advances in understanding

sepsis, the mechanisms underlying sepsis-induced GI remain complex

and poorly understood, highlighting the need for further research

(6).

Mitochondria are critical organelles for energy

production via oxidative phosphorylation, a reaction conjugated

with producing reactive oxygen species (ROS). Tadokoro et al

(7) showed that doxorubicin

inhibited mitochondrial phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione

peroxidase (GPX4) expression, resulting in mitochondrial-dependent

ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent cell death that

differs from apoptosis and necrosis due to excessive accumulation

of peroxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are principally

oxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids by ROS (8). Ferroptosis occurs in various cells

and is vital in sepsis-induced multiple organ injury (9,10).

It is particularly crucial to inhibit ferroptosis caused by

oxidative damage.

In the repair process of acute GI, diverse molecular

signals are involved in regulating mitochondrial malfunction.

Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3), a mitochondrial deacetylase, mitigates

mitochondrial oxidative damage and apoptosis by peroxiredoxin-3

(PRDX3). SIRT3 is known to regulate the acetylation status of

several mitochondrial proteins, thereby influencing their activity

and stability (11). PRDX3

functions as an efficient scavenger of hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2) to safeguard cells against oxidative

damage, especially in intestinal ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury

(11). PRDX3 functions by

oxidizing and forming its inactive dimer form to clear

H2O2 and previous studies have demonstrated

its effective inhibition of oxidative stress, apoptosis, and

mitigation of cellular damage (11,12).

Transgenic mice overexpressing PRDX3 exhibit reduced mitochondrial

H2O2 production and oxidative damage compared

with control mice (13).

Atractylodin is a bioactive compound derived from

Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC., which has been widely used

to treat various gastrointestinal diseases, including dyspepsia,

flatulence, nausea and diarrhea (14). Atractylodin has been reported to

exert anti-inflammatory effects in various inflammatory diseases.

Lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury was ameliorated by

atractylodin inhibiting the nucleotide-binding oligomerization

domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome and Toll-like receptor

4 pathways (15).

Lipopolysaccharide- and D-galactosamine-induced acute liver failure

was also attenuated by atractylodin via suppressing inflammation

and oxidative stress (13). While

investigating the effects of atractylodin on the gastrointestinal

tract, a study demonstrated the ameliorative effects of

atractylodin on intestinal dysmotility, constipation, and diarrhea

in an experimental rat model (15). Studies have highlighted its

potential therapeutic effects, particularly in the context of

immune modulation and anti-inflammatory activities (16,17).

Despite the obvious anti-inflammatory effects of atractylodin, few

studies have been conducted on its molecular targets.

Based on the aforementioned backgrounds, it was

hypothesized that atractylodin might attenuate mitochondrial

dysfunction in sepsis-induced GI by activating SIRT3 to deacetylate

PRDX3. Thus, the present study aimed to perform molecular

biological experiments to verify the potential of atractylodin in

GI. It is hoped that the present study will provide a new strategy

for alleviating GI.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Isoflurane was obtained from RWD Life Science.

Anhydrous ethanol analytical reagent (AR), xylene (AR), paraffin

(56–58°C), water-soluble eosin Y staining solution, Tween 20,

sodium chloride (AR), trichloromethane (AR) and 3%

H2O2 were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical

Reagent Co., Ltd. Hematoxylin was obtained from MilliporeSigma.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 10 mM of phosphate-buffered saline

buffer (PBS), loading buffer, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)

solution, anti-fluorescence attenuation sealant, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10,

IL-1β and IL-1α, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits and

H2O2, malondialdehyde, Fe2+ and

mitochondrial respiratory chain complex activity assay kits were

purchased from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.

GSH/GSSG detection kit was from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute. Protease phosphatase inhibitor mixture, RIPA lysate

(strong), BCA protein assay kit, JC-1 mitochondrial membrane

potential assay kit and dihydroethidium (DHE) assay kit were

purchased from Shanghai Biyuntian Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The

details of the antibodies used are listed in Table SI.

Animal treatment

Male C57 BL/6 mice aged 6–8 weeks, weighing 22–25 g,

free from specific pathogens (n=90), were purchased from Jiangsu

Huachuang Xinnuo Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. The mice were

housed at 23°C and 50% relative humidity on a 12/12-h light/dark

cycle. Basic feed was processed by Beijing Huanyu Zhongke

Biotechnology according to the national standard (GB 14924.3-2010).

The model of sepsis was induced by performing cecal ligation and

perforation. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized using 4%

isoflurane, followed by a sterile midline laparotomy of ~2 cm to

expose the cecum. Half of the distal end of the cecum was ligated

at its center, and then a 21-gauge needle was inserted between the

ligature site and the end of the cecum to extrude a small amount of

cecal contents. The cecum was gently reduced and the laparotomy

site was sutured. In the Sham group, animals underwent laparotomy

and intestinal manipulation to expose the cecum without ligation or

puncture. Monitoring was performed twice a day (once in the morning

and once in the evening) and recorded every 4 h for 48 h after

surgery. All mice received resuscitation through subcutaneous

injection of normal saline at a 24 ml/kg body weight dose.

Subsequently, all mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium

(40 mg/kg) and sacrificed for further analysis, including

collection of serum as well as stomach and colon tissue. The animal

experiments in the present study was conducted in the Liyang

Hospital of Chinese Medicine and approved by the Experimental

Animal Ethics Committee of Liyang Hospital of Chinese Medicine

(Jiangsu, China; approval no. 2024LY-02-02-03).

The solvent DMSO was employed to dissolve

atractylodin and prepare a storage solution. Prior to

administration, the solution was diluted to the desired

concentration using saline, ensuring that the final concentration

of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%. The mice were randomly allocated into

five groups: Sham operation group (Sham group), the cecal ligation

perforation sepsis group (Model group), and the atractylodin

treatment group (low, medium, and high doses), with 12 mice in each

group.

One hour before surgery, the atractylodin treatment

group received intraperitoneal injections of atractylodin at a

concentration of 10 mg/kg/d for the low-dose group, a concentration

of 20 mg/kg/d for medium-dose group, and a high-dose concentration

of 40 mg/kg/d for high dose group. Post-surgery, mice received

once-daily intraperitoneal injection doses of the designated

atractylodin dese for 7 days. The dosage of the drug was obtained

from the previous studies (18,19).

Clinical evaluation was performed with no pulsation

on palpation of the carotid artery, detection of absence of corneal

reflex, and secondary confirmation. In addition, the animals that

died naturally were subjected to pathological analysis to exclude

experimental interference factors. The present study strictly

adhered to the following criteria to determine the timing of

sacrifice through daily weight monitoring, a behavioral scoring

system, and veterinary assessment, ensuring that animals did not

suffer avoidable pain. Sacrifice were performed when one of the

following situations occurred: i) Weight loss: A rapid weight loss

of 15–20%; ii) weakness and loss of mobility: Unable to stand for

more than 24 h, loss of appetite, dehydration; iii) infection and

wound problems: A board-like abdomen upon abdominal palpation

(indicating diffuse peritonitis); bloody discharge around the anus

(indicating intestinal ischemic necrosis); iv) abnormal body

temperature: A deviation of 4°C from the normal body temperature

for more than 24 h; v) pain and behavioral abnormalities: Obvious

signs of pain (such as aggression, aimless running), neurological

symptoms (convulsions, paralysis).

A total of 90 C57BL/6 mice were used in the present

study, of which six died naturally (autopsy showed sepsis), and the

remaining mice were sacrificed at the end of the experiment.

Isolfurane 4% (oxygen flow 2 l/min) was used for induction, and the

oxygen flow rate was adjusted to 1.8% during the maintenance phase.

The depth of anesthesia was verified by blood gas analysis after

operation. Animals were sacrificed with an overdose of sodium

pentobarbital (150 mg/kilogram) by intraperitoneal injection.

Clinical evaluation was performed with no pulsation on palpation of

the carotid artery, detection of absence of corneal reflex, and

secondary confirmation. In addition, the animals that died

naturally were subjected to pathological analysis to exclude

experimental interference factors.

Histological examination

The stomach and colon tissue of the mice was fixed

for 12–24 h at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehydeTissue

embedded in paraffin was cut into 3 µm thick sections. The tissue

sections were deparaffinized with xylene (twice, each for 5 min),

followed by hydration with decreasing concentrations of ethanol.

The sections were stained with hematoxylin for 15 min, then rinsed

with tap water. The sections were then incubated in acid-alcohol

for 30 sec, immersed in tap water for 15 min, and stained with

eosin for 5 min. The sections were dehydrated with a gradient of

ethanol (95, 95, 100, 100%, each for 2 sec) and cleared with xylene

twice (each for 1 min). Finally, the sections were cleared with

xylene, mounted with neutral resin, and observed under an inverted

microscope.

Western blotting

After extracting total protein from the tissue using

RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no.

P0013), the BCA method is used to detect protein concentration. The

protein extraction of stomach and colon tissues was boiled with

gel-loading buffer for 10 min at 100°C, 50 µg protein was loaded

per lane, and resolved by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide

gel electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes.

The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA in 1X PBST buffer (0.01%

Tween-20) for 90 min at room temperature and was probed with GAPDH)

antibody (1:5,000; Proteintech Group, Inc., 10494-1-AP) or GPX4

antibody (1:1,000; Abcam, ab125066), Mitochondrial import receptor

subunit TOM20 homolog (1:1,000; Abcam, ab186735), transferrin

receptor protein 1 (TFR1) antibody (1:1,000; Abcam, ab214039),

PRDX3 antibody (1:1,000; Abcam, ab73349), SIRT3 antibody (1:1,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc., 10099-1-AP), SLC7A11 antibody (1:1,000;

Proteintech Group, Inc., 32384-1-AP), occludin antibody (1:1,000;

Abcam, ab216327), and zona occludens protein 1 (ZO-1) antibody

(1:1,000; Proteintech Group, Inc.; cat. no. 21773-1-AP), for 2 h at

room temperature. The membrane was washed three times (10 min each

in 1X PBST) and incubated with secondary anti-rabbit IgG (H+L)

antibody, (horseradish peroxidase conjugate) (1:5,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc., #7074), for 90 min at room temperature.

After being washed three times (15 min each in 1X PBST), the

membrane was incubated in a 2.0 mM DAB solution prepared in PBS for

5 min. The image of the immunoblot was digitalized with the GelDoc

XR+ system and saved in TIF format. The protein levels were

quantified by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health,

version 1.8.0) and normalized to GAPDH as an internal control.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

For immunoprecipitation assays,

Co-Immunoprecipitation kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology;

cat. no. P2175) was used following manufacturer instructions.

Briefly, the tissue was collected and rinsed with PBS.

Subsequently, tissue was lysed in the EBC buffer supplemented with

protease inhibitors [50 mM tris (pH 7.5), 120 mM NaCl, and 0.5%

NP-40]. Following ultrasonic lysis (power: 60%, ultrasonic

intermittent time: 1 min, ultrasonic frequency: three times,

ultrasonic exposure 10 s/time, 4°C), Protein A beads conjugated

with anti-PRDX3 antibody (1:500, Abcam, cat. no. ab222807) were

added to the lysate at a ratio of 20 µl bead suspension per 500 µl

protein sample, followed by overnight immunoprecipitation at 4°C.

The next day, the immunoprecipitate was pelleted by centrifugation

at 500 × g for 3 min at 4°C. Then, the resulting product was washed

in the lysis buffer. The immunoprecipitate was denatured at 100°C

for 15 min with 50 µl 2X SDS protein loading buffer. The

immunoprecipitate, input samples, and other lysates (10 µl) were

separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF) membrane for

subsequent Western blotting. To detect acetylation of PRDX3,

anti-Peroxiredoxin 3/PRDX3 antibody (Abcam; cat. no. ab222807) to

precipitate PRDX3 from the samples. Subsequently, the

Acetylated-lysine Antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; cat.

no. 9441) was used to assess the acetylated levels of PRDX3 through

immunoimprinting.

Measurement of ROS levels

DHE, a ROS-level indicative fluorescence probe

(λex=535 nm, λem=610 nm), was used to detect intracellular

superoxide anions. Fresh tissues are frozen (−20°C) and then cut

into 10 µm thick sections using a DAKEWE 6250 cryostat microtome.

The probe of DHE was incubated with tissue slices and the intensity

of red fluorescence could reflect the level of ROS under a

fluorescence microscope.

TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling

(TUNEL) staining

One Step TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. C1090) was used to detect

apoptotic cells. After incubating with the TUNEL regent in the dark

for 1 h at 37°C, cells were stained with DAPI (10 min at room

temperature). Apoptotic cells showed red fluorescence. Cells were

counted in three randomly selected fields of view using an inverted

fluorescence microscope (20X magnification, Olympus IX83, Olympus

Corporation).

Determination of

H2O2 content

H2O2 content was determined by

H2O2 Content Detection Kit (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The H2O2

detection reagent was melted in an ice bath. Next, the sample

extraction solution or standard was added to the detection well,

followed by the H2O2 detection reagent. This

was gently mixed and allowed to rest at room temperature (15–30°C)

for 5 min. A volume of 200 µl was aliquoted into a 96-well plate to

measure the absorbance at 415 nm. Subsequently, the concentration

of H2O2 in the sample was determined using a

standard curve. Absorbance values were measured at 415 nm using a

96-well plate according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Detection of markers of oxidative

stress

To clarify the effect of atractylodin on

sepsis-induced mitochondrial oxidative damage, we detected the

activity of catalase (CAT) in tissues using the Catalase (CAT)

Activity Assay Kit (Solarbio, BC0205), determined the activity of

superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in tissues with the Superoxide

Dismutase (SOD) Isoenzyme Activity Assay Kit (Solarbio, BC5255),

and measured the content of glutathione/oxidized glutathione

(GSH/GSSG) in tissues by means of the Total Glutathione

(T-GSH)/Oxidized Glutathione (GSSG) Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng

Bioengineering Institute, A061-1-2), all in accordance with the

instructions provided by the kit manufacturers. In addition, the

contents of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and

malondialdehyde (MDA) in tissues were detected using the Hydrogen

Peroxide (H2O2) Content Assay Kit (Solarbio,

BC3595) and the Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content Assay Kit (Solarbio,

BC025), respectively.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane

potential

The mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed

utilizing an advanced mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit

incorporating JC-1 (cat. no. C2003S; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In

summary, mitochondria were isolated using a tissue mitochondria

isolation kit in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. The

isolated mitochondria were subsequently incubated with 0.5 ml of

JC-1 fluorescent dye for 30 min at 4°C in the absence of light,

followed by analysis via flow cytometry (BECKMANCOULTER, CytoFLEX)

using FlowJo software (v10.6.2, FlowJo, FlowJo Enterprise).

Measurement of mitochondrial complexes

activity

The activity of complex I–IV in mitochondrial was

determined with the micro mitochondrial respiratory chain complex

I, II, III or IV activity assay kit (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Briefly, stomach and colon tissues isolated from two respective

mice in the same group were pooled and suspended in the

mitochondrial complex extraction buffer, followed by gentle

homogenization. The homogenate was centrifuged at 600 × g for 10

min at 4°C to remove cell debris and nuclei, and the supernatant

was centrifuged again at 11,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The

resultant pellet was resuspended in the extraction buffer and

crushed by ultrasonication (power: 60%; intermittent time: 1 min;

frequency: three times; 10 s/time, 4°C). The complex activity of

mitochondrial homogenates in the respective reaction buffer was

then measured spectrophotometrically at 340 nm (complex I), 605 nm

(complex II), and 550 nm (complex III and IV), respectively.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on

paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Following dewaxing and

hydration, antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer (pH

6.0), microwave treatment for 3 min. The sections are blocked with

1% goat serum (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.;

cat. no. SL038) in PBS at room temperature for 1 h and incubated

with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C (Table SI. Subsequently, the sections are

washed with PBST, incubated with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647

secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at a 1:400

dilution at room temperature for 1 h, followed by DAPI (10 µg/ml)

staining for 10 min at room temperature, and mounting. Finally, the

sections are observed under a fluorescence microscope (20X,

Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and quantified using. ImageJ software

(National Institutes of Health, version 1.8.0).

Transmission electron Microscopy

(TEM)

TEM analyses were accomplished using HT7700 Hitachi

Transmission Electron Microscope (Hitachi High-Technologies

Corporation). TEM was used to observe the mitochondrial state of

tissues. Freshly stomach and colon tissues were quickly cut into 1

mm cubes fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (4°C) and then

post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (4°C, 2 h), dehydrated through

a graded ethanol series. Embedding was performed in a 1:1 resin

(EMBed-812) and propylene oxide (Electron Microscopy Services) mix

for 1 h at room temperature, followed by a 2:1 resin:propylene

oxide mixture overnight at room temperature. Tissue were then

placed in 100% resin for 3 h at room temperature. Ultrathin

sections (70 nm) were collected and double-stained with uranyl

acetate and lead citrate (room temperature for 15 min). Finally,

the sections were visualized with a JEM1200ex Electron Microscope

(JEOL).

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector

experimental protocols

AAV serotype 9 (AAV9)-short hairpin (sh)SIRT3 and

AAV9-shNC were synthesized by Jikai Gene Chemical Technology Co.,

Ltd. Male WT C57Bl/6J mice (8-week-old) were injected in the tail

vein with 2.5×1011 viral genome particles of AAV 9.

AAV9-mediated gene transfer and expression were allowed for 2 weeks

before subsequent experiment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Comparisons among groups were tested with a one-way analysis of

variance followed by the Tukey test. An unpaired t-test is used

between the two groups (GraphPad Prism version 5; Dotmatics).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

In vivo safety

The present study initiated dose safety studies in

mice to determine safety of atractylodin. C57BL/6 mice were treated

with atractylodin (10, 20, 40 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks to simulate

long-term administration. Following common discovery-stage

practices, multiple indices of liver function and renal function

were examined. As shown in Fig.

S1 atractylodin treatment did not markedly impair liver or

renal function. The results showed that there was no significant

difference in body weight, which proved the safety of the three

groups of doses.

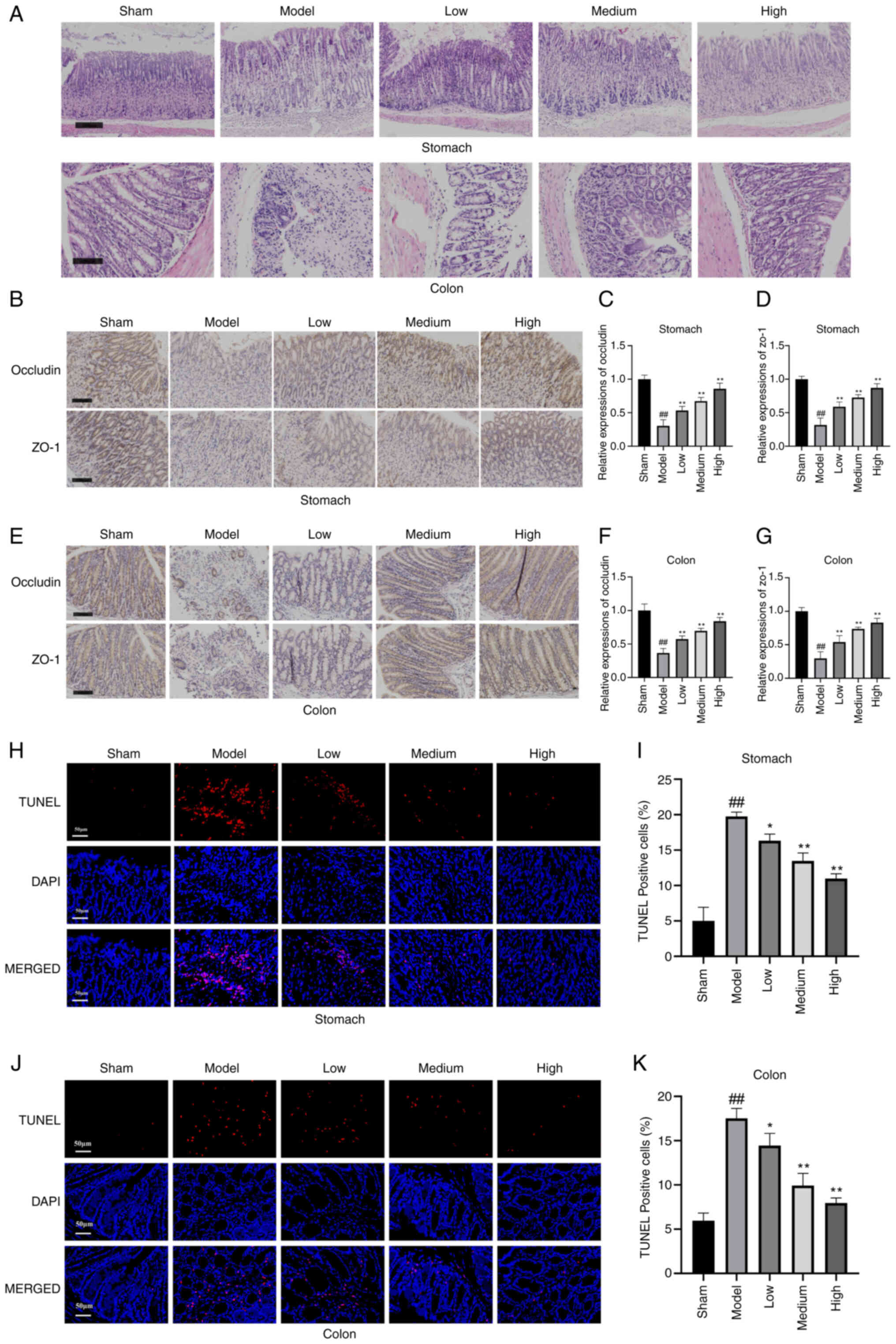

Atractylodin mitigates sepsis-induced

GI

To evaluate the effects of atractylodin on acute GI,

the present study created a model for sepsis-induced GI. The model

of sepsis was induced by performing cecal ligation and perforation.

Then, the corresponding treatments were performed in each group.

The stomach and colon tissue morphology of each group were observed

by H&E staining. The Sham group exhibited no evidence of

intestinal mucosal injury in the pathological examination results.

However, in the model group, there was an increase in epithelial

space, a decrease in the number of villous epithelial cells and

crypt cells, a disordered arrangement of villous epithelium, and

some overflow of villous tips. Atractylodin treatment markedly

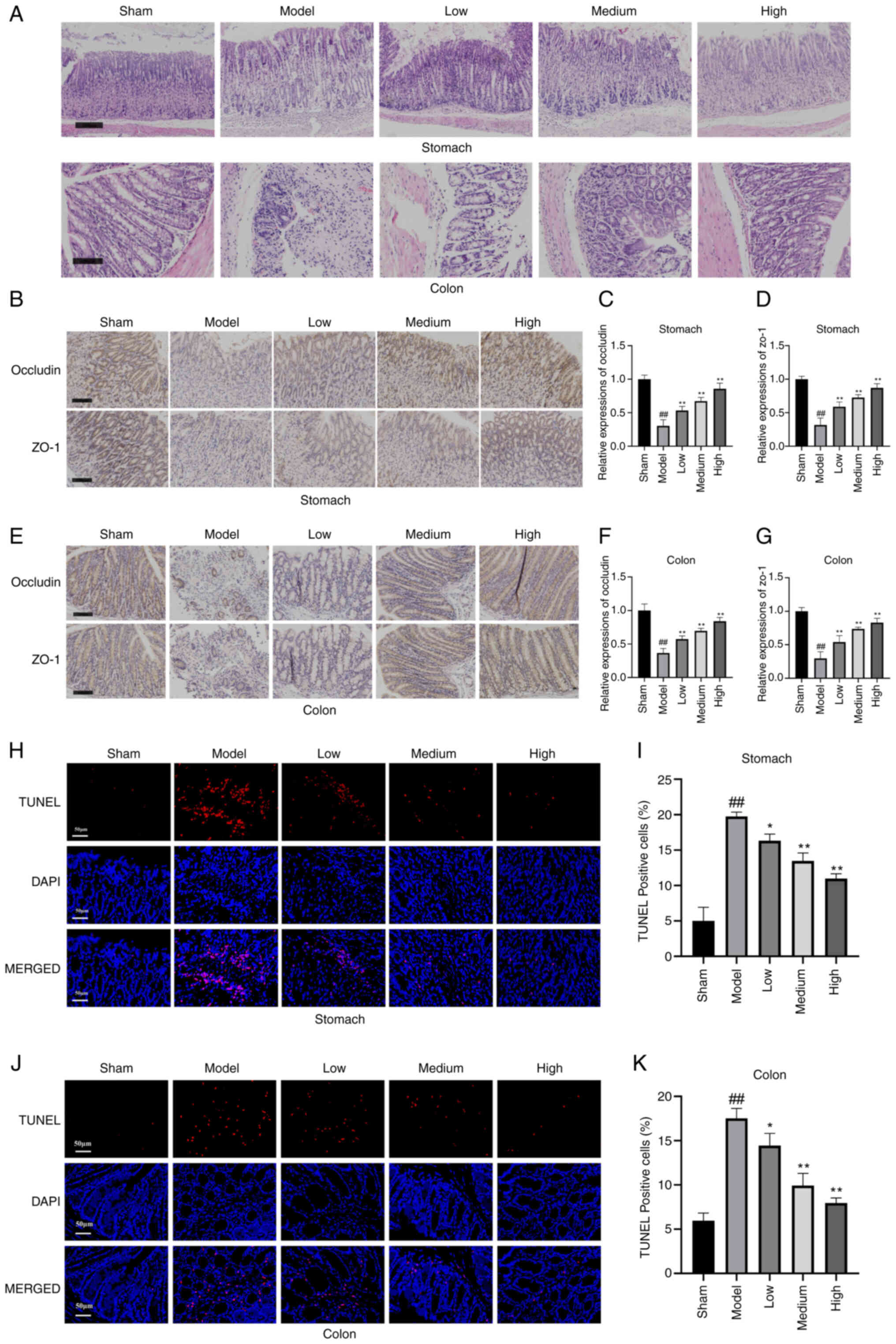

attenuated sepsis-induced acute GI (Fig. 1A).

| Figure 1.Atractylodin mitigates sepsis-induced

GI. (A) H&E staining of mousee stomach (scale bar, 200 µm) and

colon tissue. (B) The immunohistochemical detection of tissue

damage in the stomach; scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Relative expression

of Occludin in the stomach. (D) Relative expression of ZO-1 in the

stomach. (E) The immunohistochemical detection of tissue damage in

the colon, scale bar 100 µm. (F) Relative expression of occludin in

the colon. (G) Relative expression of ZO-1 in the colon. The (H)

stomach tissue and (J) colon tissue cell apoptosis were analyzed

via TUNEL assay. Blue is nuclei stained with DAPI, while red is

TUNEL-positive cells stained with TUNEL; scale bar 50 µm. The

percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in (I) stomach tissues and (K)

colon tissues. TUNEL-positive cells (%) were calculated by the

number of positive cells divided by the total number of cells. Data

are combined from n=3 biological repeats. *P<0.05, **P<0.01

vs. the model group, ##P<0.01 vs. the Sham group. GI,

gastrointestinal injury; H&E, hematoxylin-eosin; TUNEL,

terminal dUTP nick end labeling; ZO-1, Zona occludens protein

1. |

ZO-1 and Occludin are essential intestinal

epithelial tight junction proteins. The present study investigated

occludin and ZO-1 expression in the stomach and colon tissue with

immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1B and

E). The groups treated with atractylodin in low, medium and

high doses appeared to relieve the pathological injuries to

different degrees compared with the model group. The results

demonstrated that the levels of ZO-1 and occludin in the model

group were markedly lower than those in the Sham group, indicating

impaired colon barrier function. Compared with the model group, the

expression levels of ZO-1 and Occludin were markedly higher in all

atractylodin treated groups (Fig. 1C,

D, F and G).

The present study then assessed the role of

atractylodin in modulating apoptosis of stomach and colon tissues

in the mice using TUNEL staining. The number of TUNEL-positive

cells was increased in mice's stomach and colon tissues in the

model group, whereas atractylodin blocked this elevation

(P<0.01; Fig. 1H-K). these

results demonstrated that atractylodin represses the apoptosis of

stomach and colon tissues in mice.

To further evaluate the effects of atractylodin on

sepsis-induced GI mice, the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines

were determined in the serum and tissues. The cytokines of IL-1β,

IL-6, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-10 were evaluated in the blood, stomach

tissue, and colon tissue using ELISA (Fig. S2). Atractylodin effectively

prevented the increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines, while

increasing levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, and

IL-10.

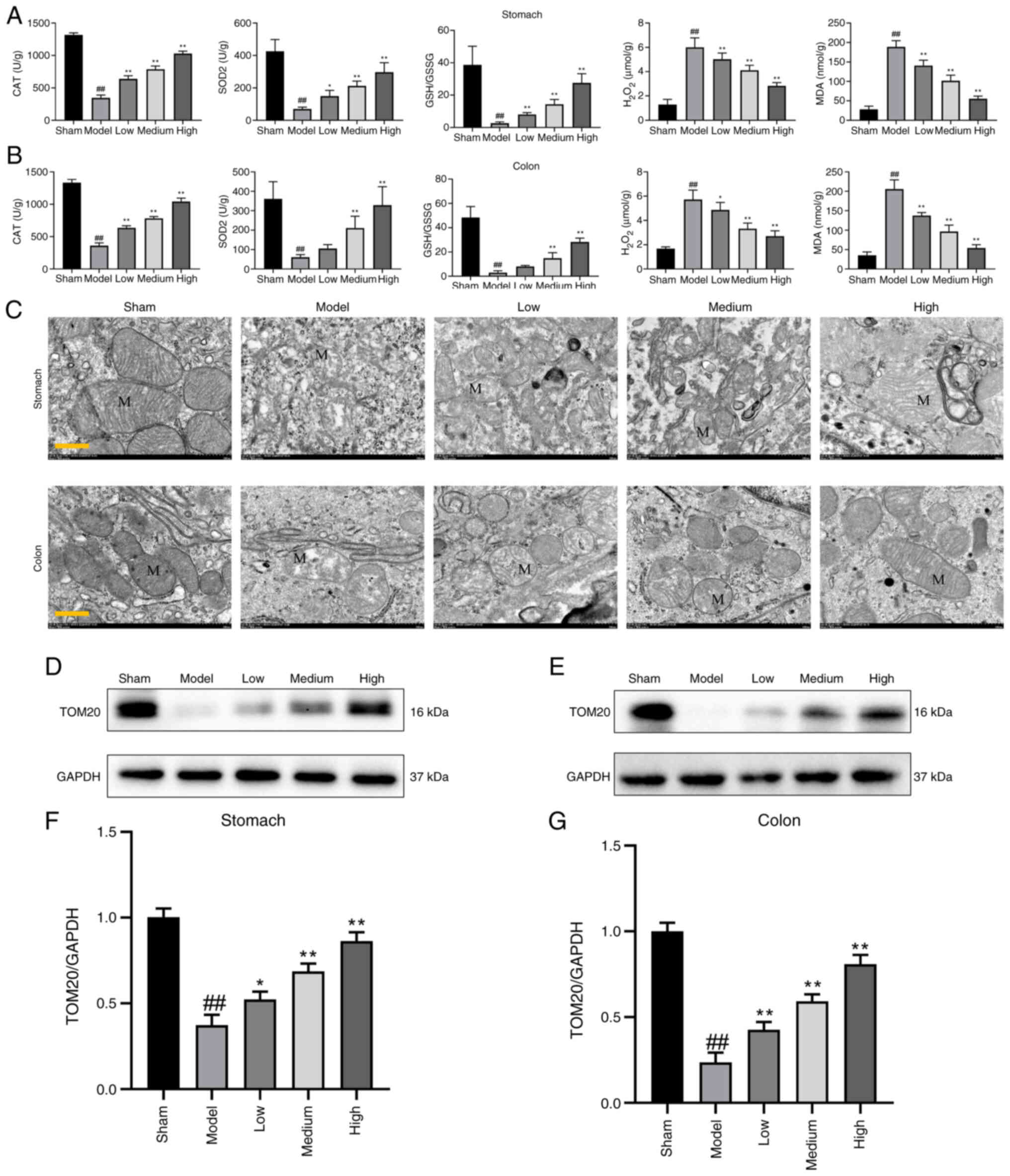

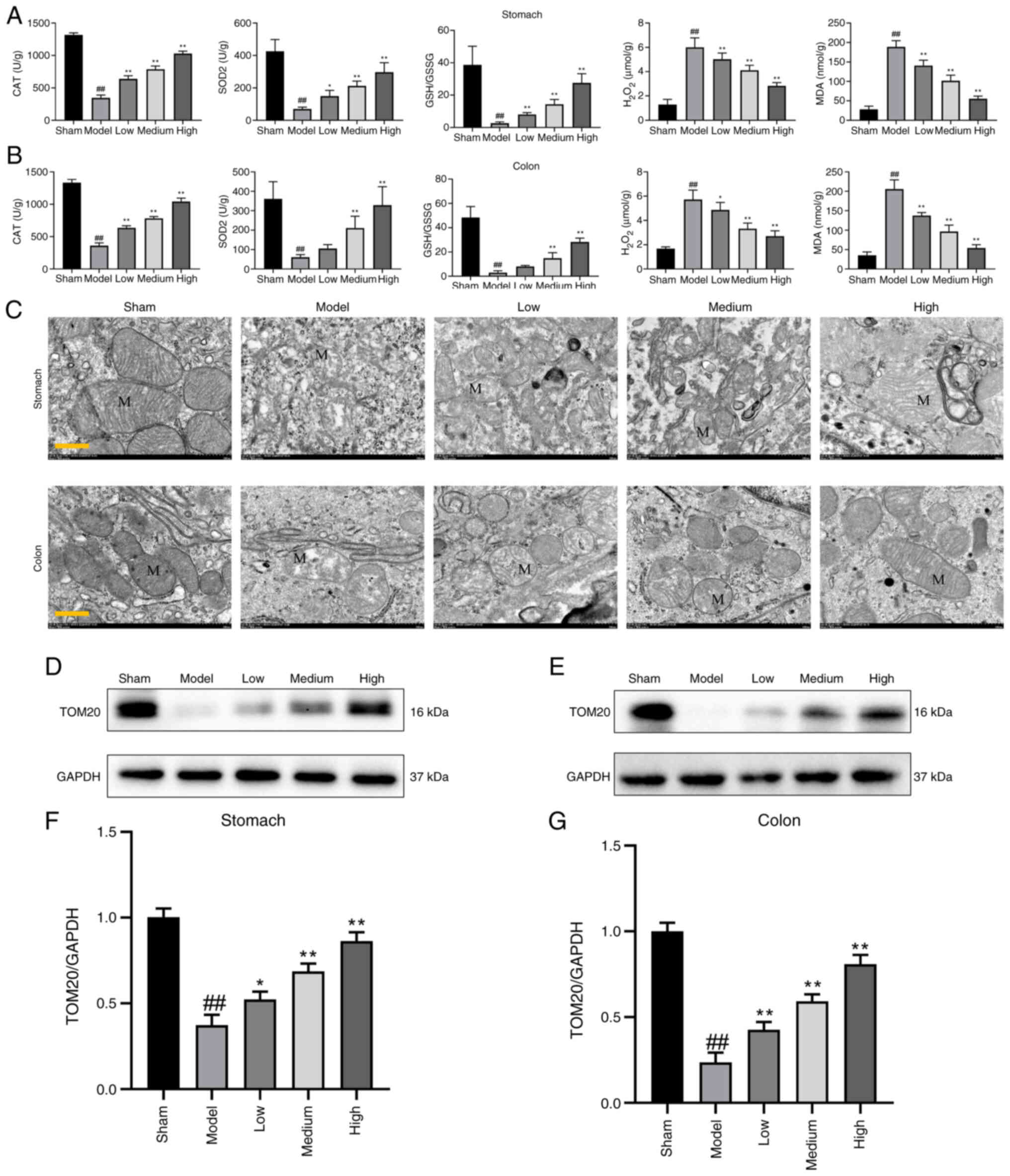

Atractylodin improves mitochondrial

dysfunction

Fig. 2A and B

illustrates changes in antioxidant defense system indicators such

as SOD2 and CAT levels in experimental mice. In the treatment

group, there was a significant increase in CAT, SOD 2, and GSH/GSSG

levels when compared with the model group in stomach and colon

tissues. As shown in Fig. 2A-B,

atractylodin treatment markedly decreased levels of

H2O2 and MDA in a dose-dependent manner. In

addition, mitochondrial morphology changes and function were

evaluated by TEM. TEM revealed more disorganized, swollen, and

damaged mitochondria in the model group. This mitochondrial damage

was mitigated in the atractylodin-treated group in stomach and

colon tissues (Fig. 2C).

Semiquantitative western blotting analysis showed a trend to

increase in TOM20/GAPDH ratio, which suggests an increase in

mitochondrial number or mitochondrial dimensions in

atractylodin-treated group compared with the model group (Fig. 2D-G).

| Figure 2.Effect of atractylodin on regulating

mitochondrial dysfunction. (A) Regulation of mitochondrial

oxidative damage markers: CAT, SOD 2, GSH/GSSG,

H2O2, MDA in the stomach, and (B) colon

tissue. (C) TEM images of mitochondrial morphology of each group.

Western blot analysis of mitochondrial membrane TOM20 markers in

(D) stomach and (E) colon tissue. Scale bar 500 nm. Relative

quantitation of the intensity of TOM20 in the (F) stomach and (G)

colon tissue. Values are means ± SD of n=6 (A, B, F and G) or n=3

(D and E) experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. the model group,

##P<0.01 vs. the Sham group. CAT, catalase; SOD 2,

superoxide dismutase; GSH/GSSG, glutathione/glutathione (oxidized);

MDA, malondialdehyde TEM, transmission electron microscopy; TOM20,

mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM20 homolog; MDA,

malondialdehyde. |

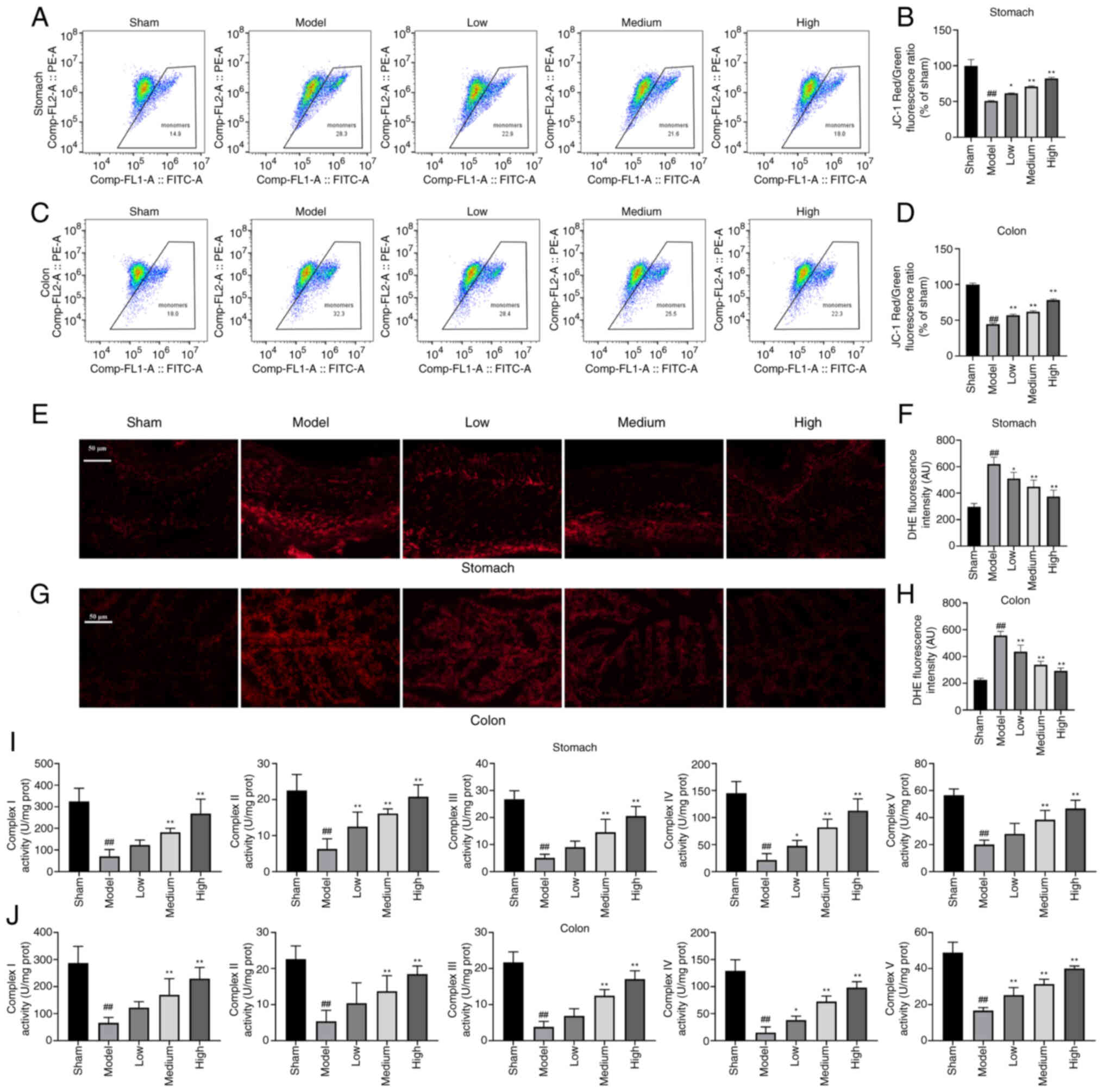

The mitochondrial function was further examined. To

assess the transmembrane potential, a flow cytometric-based assay

was performed to measure transmembrane potential in each group in

the stomach and colon tissue. Cells of the gastric and colon tissue

of mice in each group were isolated and the mitochondrial membrane

potential was detected using a mitochondrial membrane potential

detection kit. We found that the potential for the dissipation of

mitochondrial transmembrane could be attenuated by atractylodin in

each group of stomach and colon tissue (Fig. 3A-D). To examine the ROS levels,

stomach and colon tissue were stained with DHE, a superoxide

indicator. The intensity of DHE fluorescence was markedly decreased

in all atractylodin concentration groups compared with the model

group (Fig. 3E-H). Mitochondrial

complexes I, II, III, IV, and V activities were also markedly

enhanced in each atractylodin concentration group compared with

those in the model group (Fig. 3I and

J).

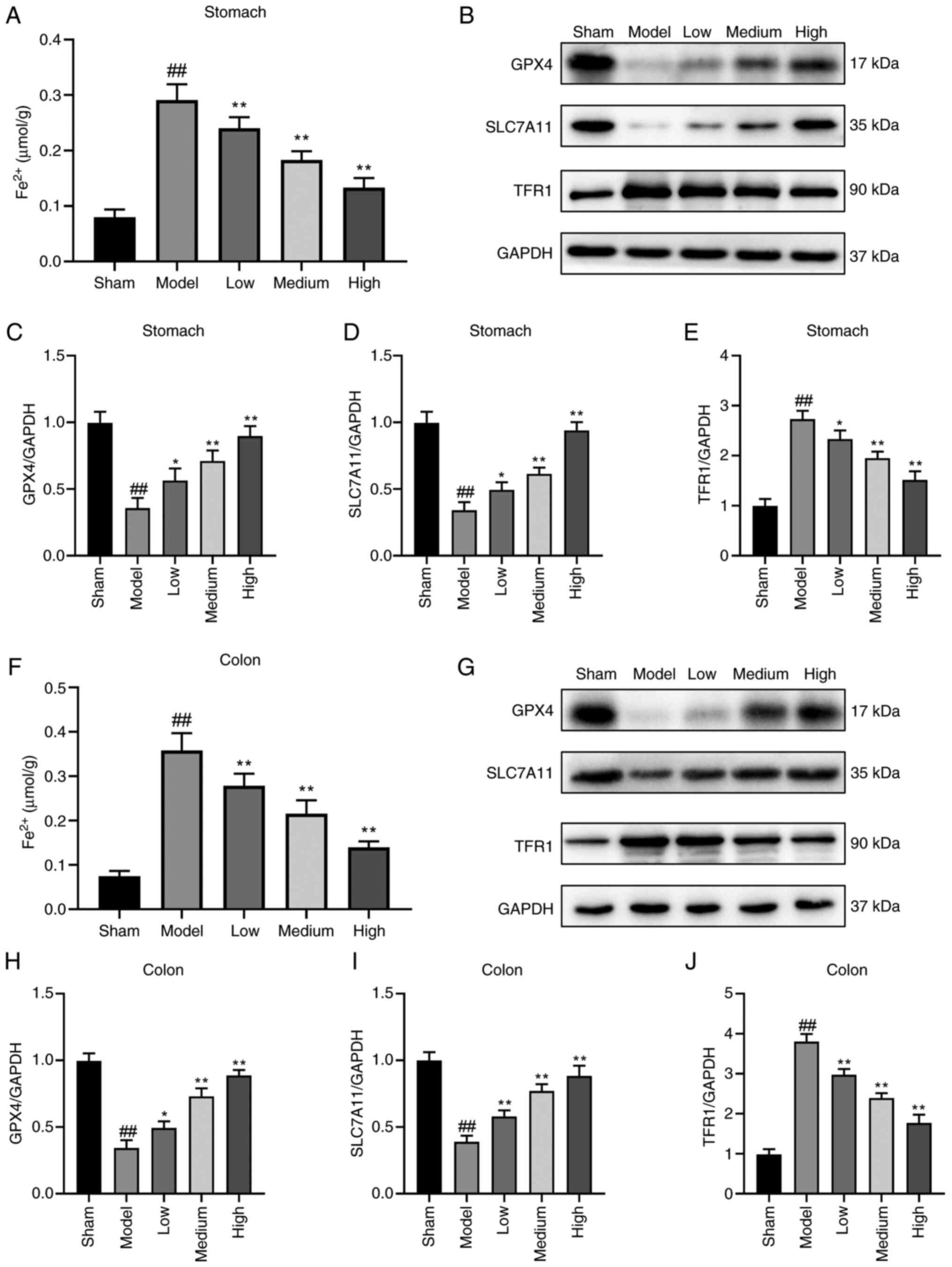

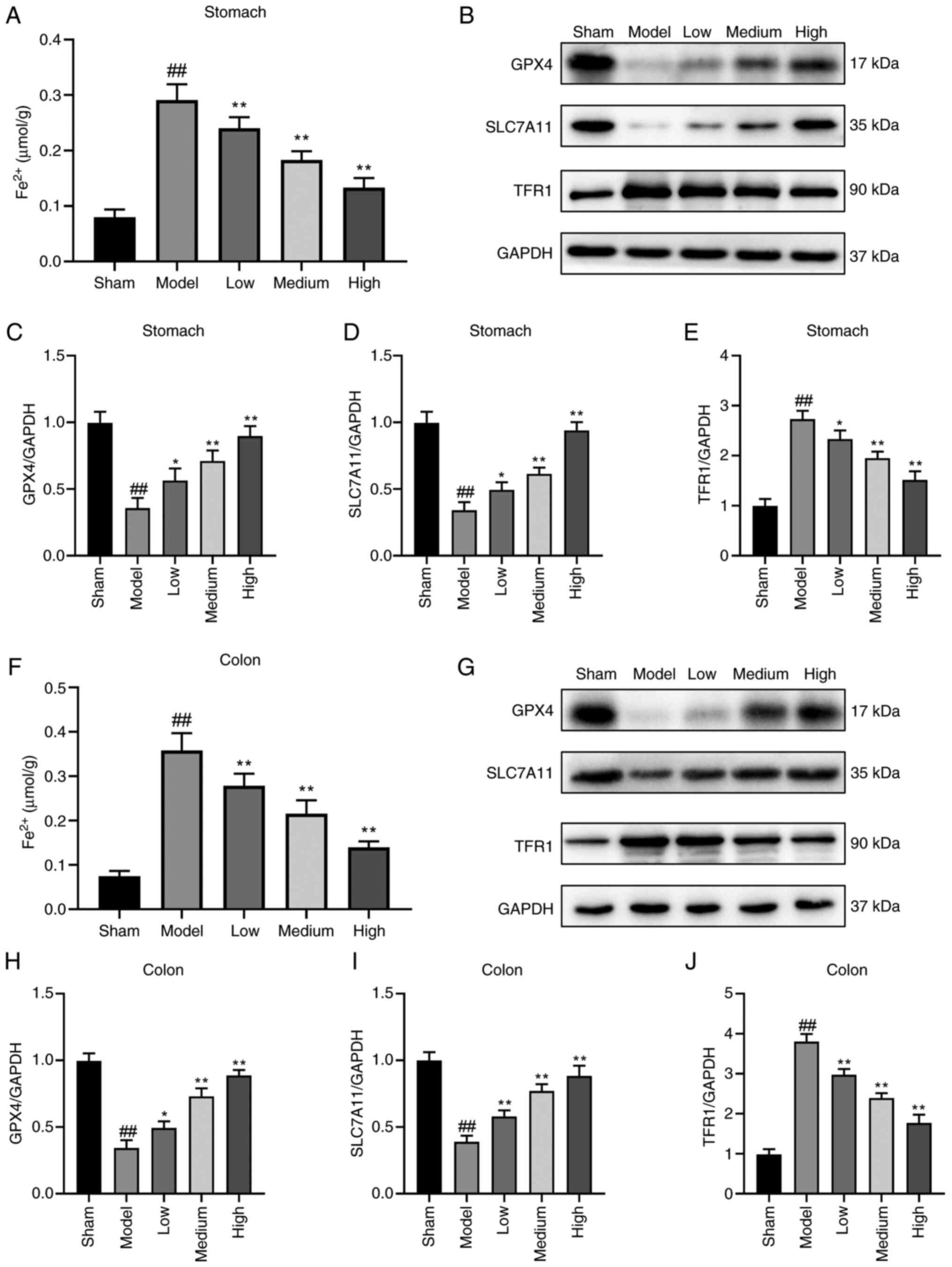

Atractylodin inhibits ferroptosis in

mice with sepsis-induced GI

To address the role of atractylodin in ferroptosis

of sepsis-induced GI, the Fe2+ levels in stomach and

colon tissues were determined. The results showed that the level of

Fe2+ in stomach and colon tissues of mice was markedly

decreased in the atractylodin-treated group (Fig. 4A and F). Based on the

aforementioned results, the essential proteins related to

ferroptosis were detected in each group. Western blotting showed

that the levels of GPX4 and Solute carrier family 7 member 11

(SLC7A11) in the atractylodin-treated group were markedly higher

compared with those of the model group. At the same time, TFR1 was

decreased in both stomach tissues (Fig. 5B-E) and colon tissues (Fig. 5G-J). these results showed that

atractylodin inhibited ferroptosis in mice with sepsis-induced

GI.

| Figure 4.Atractylodin treatment improves the

prognosis of sepsis-induced ferroptosis in the stomach and colon

tissues. (A) Determination of the expression levels of

Fe2+ in stomach tissues. (B) Protein expression levels

of GPX4, SLC7A11, TFR1 and GAPDH in stomach tissue in each group.

Quantification of relative protein expression of (C) GPX4, (D)

SLC7A11 and (E) TFR1in the stomach tissue. (F) Determination of the

expression levels of Fe2+ in colon tissues. (G) Protein

expression levels of GPX4, SLC7A11, TFR1 and GAPDH in colon tissue

in each group. (H-I) Quantifying relative protein expression of (H)

GPX4, (I) SLC7A11 and (J) TFR1 in the colon tissue. Values are

means ± SD of n=6 (A and F) or n=3 (B-E and G-J) experiments.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. the model group, ##P<0.01

vs. the Sham group. GPX4, Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione

peroxidase; SLC7A11, Solute carrier family 7 member 11; TFR1,

transferrin receptor protein 1; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase. |

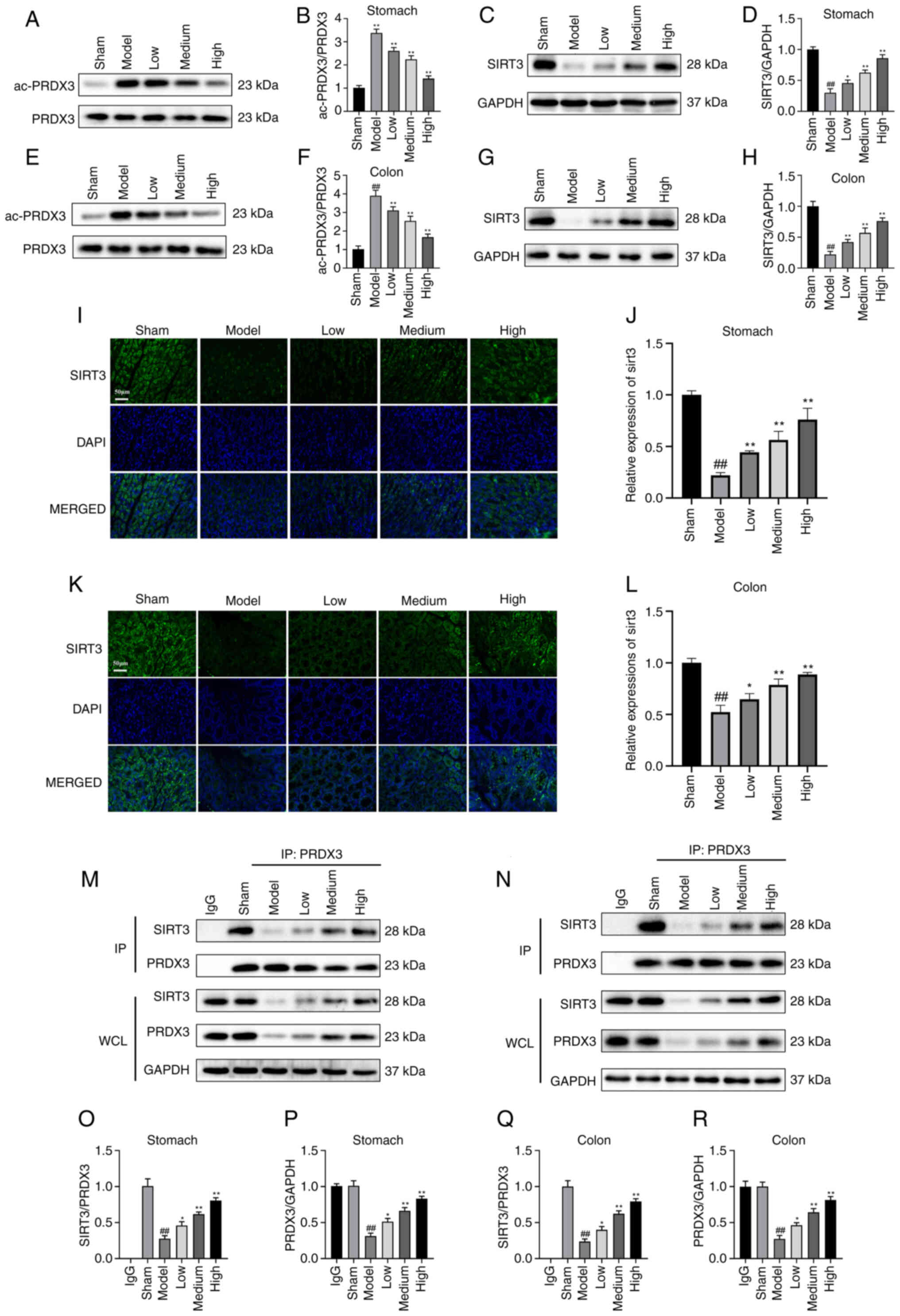

Atractylodin upregulate SIRT3 while

suppress acetylation of PRDX3

It has been suggested that SIRT3-mediated

deacetylation of PRDX3 could alleviate mitochondrial oxidative

injury (11). The present study

examined the expression of Ac-PRDX3 and SIRT3 in the stomach and

colon tissues of mice. The expression of Ac-PRDX3/PRDX3 in the

stomach tissues of mice in the atractylodin-treated group was lower

than that in the model group. The high-dose atractylodin-treated

group showed the lowest Ac-PRDX3/PRDX3 levels in stomach tissues

(Fig. 5A and B). As shown in

Fig. 5C and D, the SIRT3

expression markedly increased in the high-medium- and low-dose

groups compared with the model group. The same trend was observed

in the colon tissues (Fig. 5E-H).

The expression of SIRT3 increased in the stomach and colon tissues

of mice in the atractylodin-treated group compared with the model

group (Fig. 5C, D, G and H). To

explore how atractylodin regulates SIRT3 expression in cells, SIRT3

was colocalized with the nuclei marker DAPI using

immunofluorescence in the stomach and colon tissues. As shown in

Fig 5I and K, The increased SIRT3

expression with the atractylodin treatment groups was shown by

immunofluorescence. The expression of SIRT3 increased with an

increased dose of atractylodin in the stomach and colon tissues of

mice in atractylodin treated group compared with the model group

(Fig. 5J and L).

To assess whether atractylodin promotes the binding

of SIRT3 to PRDX3, a co-immunoprecipitation assay was performed.

The results showed that the binding of SIRT3 with PRDX3 was

increased in all atractylodin treatment groups (Fig. 5M and N). The high doses of the

atractylodin group showed increased SIRT3/PRDX3 and PRDX3/GAPDH in

the stomach and colon tissues (Fig. 5N

and O).

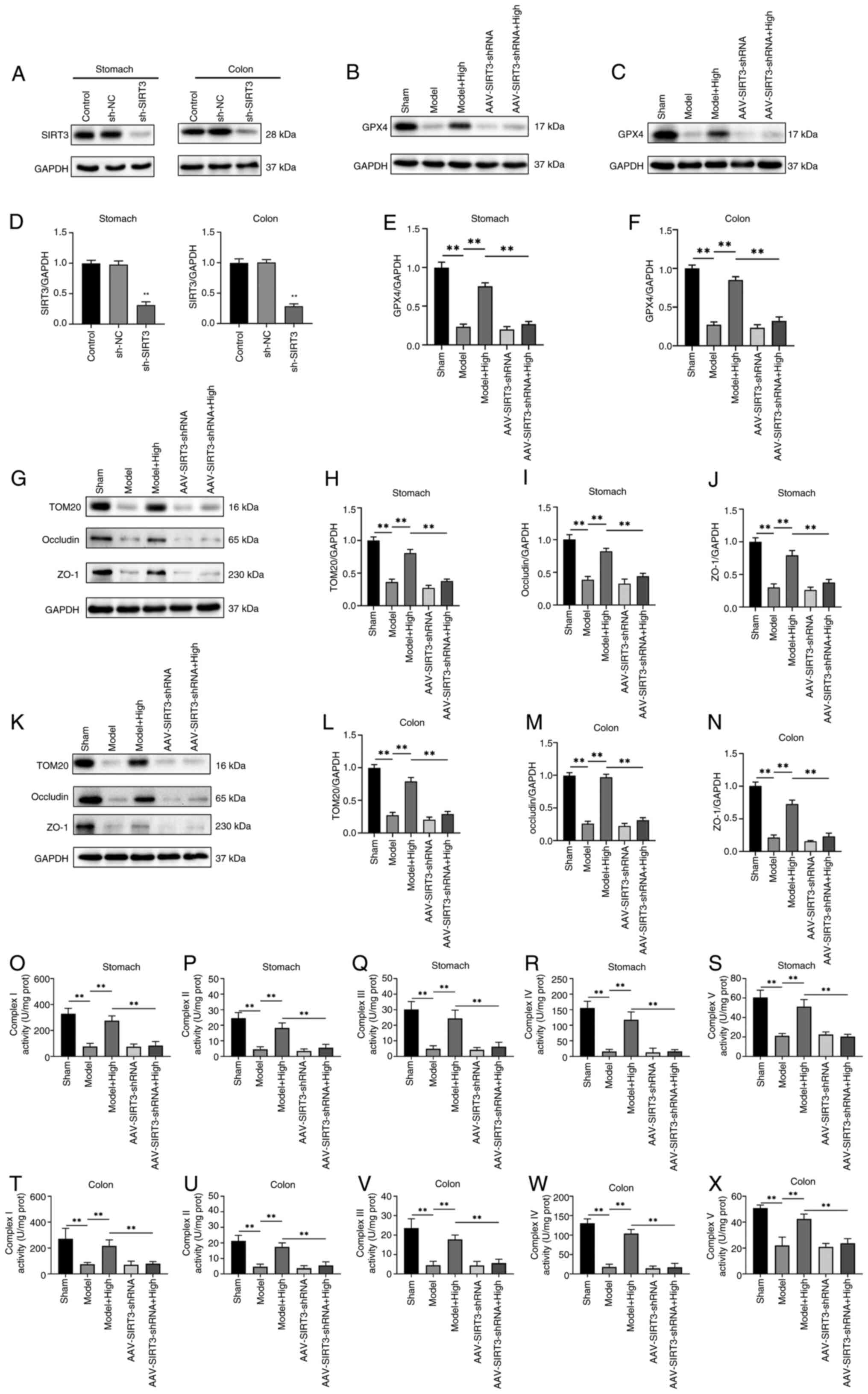

Atractylodin abolishes sepsis-induced

mitochondrial dysfunction in GI through mediation of SIRT3/PRDX3

signaling

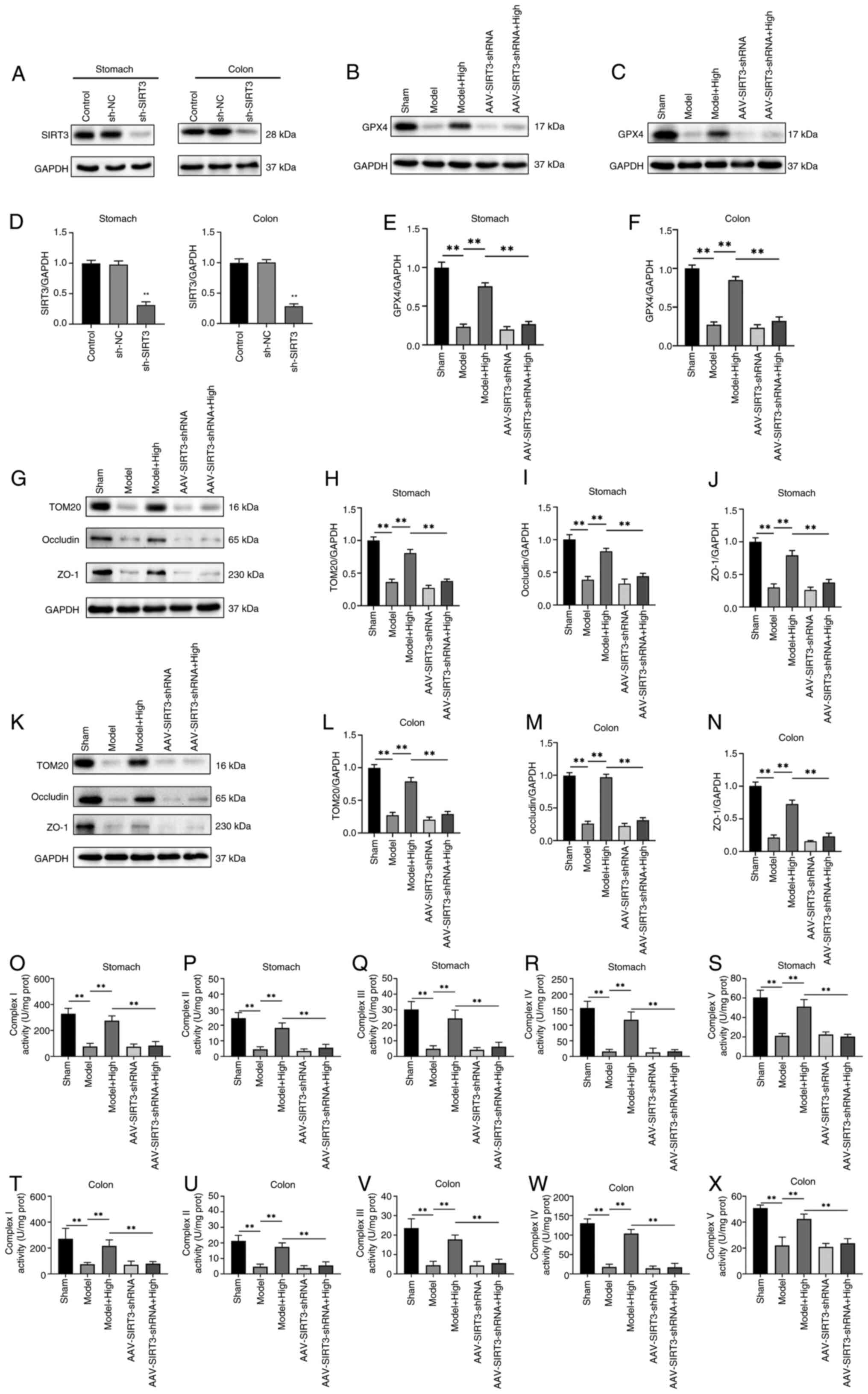

The downstream regulatory mechanism of the SIRT3 and

PRDX3 was explored in sepsis-induced GI. To confirm the involvement

of SIRT3 in the reparative effect on sepsis-induced GI, shSIRT3 was

intravenously injected into the mice through the tail vein to knock

down SIRT3. Fig. 6A and B showed

that the protein levels of SIRT3 were markedly downregulated by 68%

following injection with shSIRT3, as compared with the mice

injected with shNC. Mice were divided into five groups: sham group,

model group, model + atractylodin group, AAV-shSIRT3 group, and

AAV-shSIRT3 + atractylodin group. The expression of GPX4 in the

stomach and colon tissue was measured by eastern blotting. The

results demonstrated that in the stomach and colon tissue, the GPX4

expression in the model group was markedly reduced compared with

the sham group (Fig. 6C and E).

However, it was obviously upregulated in the model mice treated

with high-atractylodin. Compared with the model combined with

atractylodin group, the GPX4 level of both the AAV-shSIRT3 and the

AAV-shSIRT3 + atractylodin group was markedly decreased (Fig. 6D and F). These results suggested

that SIRT3 plays a key role in ferroptosis-mediated GI. Western

blotting also demonstrated that the protein expression of TOM20,

ZO-1 and occludin was markedly decreased in the AAV-shSIRT3 +

atractylodin treated group compared with the model combined with

atractylodin group in the stomach (Fig. 6G-J) and colon tissues (Fig. 6K-N). These results showed that

atractylodin inhibited mitochondrial oxidative stress by increasing

SIRT3 expression. Moreover, mitochondrial complexes I, II/III, IV

and V activities were also markedly attenuated in AAV-shSIRT3+

atractylodin-treated mice, as compared with model combined with

atractylodin mice in the stomach (Fig.

6O-S) and colon tissues (Fig.

6T-X).

| Figure 6.Regulatory mechanism of SIRT3 and

PRDX3 in sepsis-induced ferroptosis-mediated mitochondrial

oxidative damage. (A) Western blot analysis of SIRT3 protein level

in the stomach and colon tissue. Mice were injected with sh-SIRT3

or control shRNA (shRNA-NC). (B) Western blot analysis of GPX4

protein level in stomach and (C) Western blot analysis of GPX4

protein level in colon tissue. (D) Relative SIRT3/GAPDH expression

obtained using ImageJ software. Relative quantitative evaluation of

the GPX4/GAPDH expression in (E) stomach and (F) colon tissue of

each group. (G) Western blot analysis of TOM20, occludin, and ZO-1

protein level in stomach tissue of each group. Relative

quantitative evaluation of (H) TOM20, (I) occludin and (J) ZO-1

protein expression level in stomach tissue in each group. (K)

Western blot analysis of TOM20, occludin, and ZO-1 protein level in

stomach and colon tissue of each group. Relative quantitative

evaluation of (L) TOM20, (M) occludin and (N) ZO-1 protein

expression level in colon tissue. Activity of mitochondrial

respiratory chain complex (O) I, mitochondrial respiratory chain

complex II (P), mitochondrial respiratory chain complex III (Q),

mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV (R), mitochondrial

respiratory chain complex V (S) in the stomach tissue. (T-X) The

activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I (T),

mitochondrial respiratory chain complex II (U), mitochondrial

respiratory chain complex III (V), mitochondrial respiratory chain

complex IV (W), mitochondrial respiratory chain complex V (X) in

the colon tissue. Values are means ± SD of n=3 (A-N) or n=6 (O-X)

experiments. **P<0.01. SIRT3, NAD-dependent protein deacetylase

sirtuin-3, mitochondrial; PRDX3, peroxiredoxin-3; sh, short

hairpin; GPX4, Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase;

TOM20, mitochondrial import receptor subunit TOM20 homolog; ZO-1,

zona occludens protein 1. |

Discussion

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome characterized by an

aberrant inflammatory response to infection, leading to organ

dysfunction. Target organ dysfunction caused by sepsis and multiple

organ dysfunction syndrome are the primary causes of patient

mortality, with acute GI being particularly prevalent (3). The gastrointestinal tract is the

target for inflammatory mediators in sepsis and is a significant

source of these mediators (20).

Studies have reported varying degrees of GI in patients with sepsis

(21), making it the most common

complication associated with this condition. Impaired

gastrointestinal function results in bacterial translocation and

toxin transfer into the bloodstream, exacerbating inflammation and

impairing multiple organ function. Consequently, sepsis and

gastrointestinal dysfunction mutually reinforce each other,

creating a vicious cycle. Furthermore, since the gastrointestinal

tract is often the initial site affected by multiple organ

dysfunction syndrome resulting from sepsis, actively improving

gastrointestinal function of patients is significant in enhancing

the success rate of sepsis treatment.

Atractylodin is classified as an acetylene compound,

and modern pharmacological studies have demonstrated its

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties (22). The present study constructed a

cecum ligation perforation model to investigate how atractylodin

alleviates sepsis-associated gastrointestinal damage. ZO-1 and

occludin are crucial components of tight junctions, and their

downregulated expression or reduced activity can impair the

formation of tight junctions between cells, compromising the vital

defense barrier function of the intestinal mucosa and increasing

the risk of enteroborne infections caused by harmful bacteria and

toxins penetrating the bloodstream (23). The present study indicated that the

administration of atractylodin upregulated the expression of ZO-1

and occludin in gastrointestinal tissue, suggesting its potential

to enhance gastrointestinal tissue barrier function and reduce

inflammation occurrence. Histological examination using H&E and

immunohistochemical staining also revealed improved intestinal

damage repair and enhanced barrier function in both stomach and

colon tissues among mice in the all-administration group.

The concept of ferroptosis was initially proposed as

a form of iron-dependent programmed cell death, distinct from

apoptosis, cell necrosis, and autophagy (24). Various cellular metabolic events

including redox homeostasis, iron load, mitochondrial function and

lipid metabolism regulate ferroptosis. Mitochondria play crucial

regulatory roles in the process of iron death and are essential for

cellular resistance against it (25). Maintaining mitochondrial integrity

is an effective strategy for preventing iron death across different

cell types. The present study used electron microscopy to

demonstrate structural disorder, swelling and damage in the model

group mice; however, treatment with atractylodin reduced

mitochondrial damage while increasing the number and size of

mitochondria in the administration group. Upregulation of CAT, SOD2

and GSH/GSSG proteins indicated that atractylodin could mitigate

cell damage; meanwhile, downregulation of

H2O2 and MDA proteins suggested an

improvement in mitochondrial oxidative stress.

Mitochondria are the primary sites for ATP

generation in animal and plant cells. During respiratory oxidation,

asymmetric protons and other ions are distributed on both sides of

the inner membrane of mitochondria, resulting in mitochondrial

membrane potential (MMP) (26).

Maintaining a normal MMP is essential for sustaining mitochondrial

oxidative phosphorylation and ATP production, which contributes to

maintaining cellular physiological functions (27). The present study employed flow

cytometry and mitochondrial membrane potential detection kits to

investigate the effects of atractylodin on mitochondrial

transmembrane energy consumption and membrane potential in stomach

and colon tissues. The results revealed that atractylodin can

decrease mitochondrial transmembrane energy consumption while

enhancing the membrane potential.

The mitochondrial respiratory chain is a key

component of cellular energy metabolism, functioning as a

continuous reaction system that consists of a series of hydrogen

transfer reactions and electron transfer reactions in a specific

sequence, commonly referred to as the electron transport chain

(28). This respiratory chain

reaction efficiently synthesizes abundant ATP molecules while

simultaneously removing hydrogen atoms from metabolites to generate

water (29). Assessing the

activity of mitochondrial complexes can provide insights into the

effectiveness of electron transport in redox processes involved in

oxidative phosphorylation and cell death. The present study

demonstrated significant enhancements in mitochondrial complex I,

II, III, IV and V activities among mice exposed to different

concentrations of atractylodin. Furthermore, elevated levels of

mitochondrial ROS induce ferritin autophagy and increase

intracellular iron content, ultimately leading to ferroptosis

(30). Gastric and colon tissues

were stained with DHE, a superoxide indicator. Compared with the

model group, each concentration group treated with atractylodin

exhibited markedly reduced fluorescence intensity of DHE,

indicating that atractylodin effectively mitigates mitochondrial

ROS levels.

The accumulation of large quantities of free

Fe2+ can also induce ferroptosis (31) due to its role as a cofactor for

various metabolic enzymes, such as lipid oxygenase, thereby

enhancing their activity and promoting the production of lipid

peroxides. Fe2+ level catalyzed by the Fenton reaction

leads to the generation of peroxy and hydroxyl radicals, which

further react with lipid peroxides, resulting in the substantial

production of lipid ROS. Ultimately, these processes culminate in

the induction of ferroptosis (31). The present study assessed the

Fe2+ level and observed a significant reduction in the

atractylodin-administration group. The SLC7A11-GPX4 axis is the

pivotal system involved in resistance against ferroptosis (31). GPX4 is a glutathione peroxidase

that utilizes glutathione to detoxify lipid peroxides and inhibit

ferroptosis. TFR1 is a membrane protein widely expressed across

various cell and tissue types within the human body. Western

blotting analysis revealed markedly higher levels of GPX4 and

SLC7A11 in the administration group treated with atractylodin

compared with those in the model group. It also downregulated TFR1

expression.

PRDX is a potent thiol peroxidase family that

comprises at least six subtypes in mammalian cells (32). Isoforms PRDX1, PRDX2 and PRDX6 are

localized in the cytoplasm, while PRDX4 is found in the endoplasmic

reticulum. PRDX5 is located in both the peroxisome and

mitochondria, whereas PRDX3 is the dominant species within the

mitochondria (33). As PRDX3 is

the most abundant and effective enzyme for

H2O2 elimination in mitochondria, it serves

as an important mitochondrial antioxidant protein and acts as a

target for nearly 90% of HO produced in the matrix (34). The clearance of HO by PRDX3 occurs

through its oxidation to an inactive dimer form (35), with previous studies reporting its

ability to effectively inhibit oxidative stress, and apoptosis

(11–13,36),

and decrease cell damage. Transgenic mice overexpressing PRDX3 have

shown reduced production of H2O2 and

decreased oxidative damage within their mitochondria compared with

control mice (37). SIRT3, a

highly conserved nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent

deacetylase primarily expressed in mitochondria, regulates several

mitochondrial proteins involved in fatty acid oxidation, oxidative

phosphorylation, and antioxidant reaction systems (38). The immediate clearance of ROS by

SIRT3 is not feasible, while PRDX3 undergoes reversible acetylation

(39). Therefore, it was

hypothesized that SIRT3 plays a role in sepsis combined with GI

through deacetylation of PRDX3. The present study revealed the

downregulation of PRDX3 expression along with upregulation of SIRT3

expression in gastric tissues treated with atractylodin. To

investigate how atractylodin regulates SIRT3 expression within

cells, immunofluorescence was employed to co-localize SIRT3 with

nuclear marker DAPI within gastric and colon tissues.

Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated increased SIRT3 expression

upon treatment with atractylodin. Co-IP revealed an enhanced

interaction between SIRT3 and PRDX3 in the group treated with

atractylodin. Moreover, when SIRT3 was downregulated using

AAV-shSIRT3, the regulatory effect of atractylodin on mitochondrial

and cellular ferroptosis was attenuated. These findings suggested

that SITR3 mediated the inhibitory effects of atractylodin on cell

ferroptosis in sepsis-induced GI.

Research indicates that SIRT3 within mitochondria

undergoes SUMOylation under physiological conditions, markedly

inhibiting its deacetylase activity (40). Under conditions of metabolic

stress, the desumoylation enzyme SENP1 translocates to

mitochondria, restoring the deacetylation activity of SIRT3 by

removing its SUMOylation modification (41). This process regulates the

acetylation levels of mitochondrial proteins, thereby influencing

metabolic functions (41).

Notably, resveratrol, a natural activator of SIRT3, has been shown

to upregulate the expression of SOD2 and catalase via the

SIRT3/FoxO3a signaling axis, ROS and lipid peroxide levels, and

inhibit ferroptosis by enhancing the GSH/GPX4 pathway activity.

This activity effectively mitigates intestinal I/R injury (42). These findings demonstrate the

regulatory mechanisms of the dynamic post-translational

modifications of SIRT3 and provide a theoretical foundation for the

cytoprotective effects of monomeric components of traditional

Chinese medicine by targeting the downstream effector molecules of

SIRT3. Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that

atractylotin may enhance the deacetylation of PRDX3 by SIRT3

through the desumoylation of SIRT3, which ultimately exerts its

organ-protective effect by restoring mitochondrial redox

homeostasis and inhibiting ferroptosis during sepsis-induced GI.

However, the precise molecular regulation mechanism remains to be

elucidated by future studies.

The present study acknowledges several limitations.

First, the investigation did not incorporate an analysis of the

effect of interval dosing on efficacy, as comparisons between short

and long treatment courses were not conducted. As a mechanistic

study exploring the role of atractylodin in sepsis treatment, the

primary objective was to verify its fundamental efficacy and

dose-response relationship. To optimize dosing frequency and

duration, it is essential to integrate pharmacokinetic data.

Secondly, further research is required to elucidate the precise

molecular regulatory mechanisms involved in downstream

processes.

The present basic science study offers essential

preclinical evidence supporting the potential therapeutic efficacy

of atractylodin in the treatment of sepsis and establishes a

mechanistic basis that underscores the need for further

translational research. Prior to initiating clinical evaluation, it

is imperative to conduct comprehensive preclinical safety and

toxicology studies in relevant animal models to evaluate potential

systemic toxicity, organ-specific adverse effects and establish

safe dosage ranges for initial human trials. Subsequent rigorous

investigations into pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics (PK/PD)

are necessary to fully elucidate the absorption, distribution,

metabolism and excretion profile of atractylodin in relevant

preclinical species and to understand how drug exposure levels

correlate with the observed therapeutic outcomes and potential

toxicities. These PK/PD data are crucial for informing initial dose

selection for human studies. Following successful preclinical

validation, the potential of atractylodin would be evaluated in a

structured clinical trial program. This typically begins with Phase

1 trials in a small group of healthy volunteers or patients with

stable conditions to assess safety, tolerability and basic human

PK/PD (43). If deemed safe, Phase

2 trials would then enroll a larger cohort of sepsis patients to

investigate preliminary efficacy, explore dose-response

relationships, and further evaluate safety in the target

population. Efficacy endpoints in Phase 2 sepsis trials commonly

include changes in organ dysfunction scores, inflammatory markers,

or surrogate outcomes (44). Based

on promising Phase 2 results, Phase 3 trials would be necessary to

confirm efficacy on clinically relevant endpoints such as 28-day

mortality and time to organ failure resolution, in large,

multi-center, randomized controlled studies comparing atractylodin

to current standard of care (45).

Successfully navigating these rigorous clinical trial phases is

required to ultimately assess the safety, efficacy, and optimal

dosing of atractylodin for potential clinical use in human patients

with sepsis.

In summary, atractylodin can ameliorate

mitochondrial dysfunction in the acute gastrointestinal tract of

sepsis and mitigate ferroptosis. The underlying mechanism involves

the SIRT3/PRDX3 signaling pathway. Atractylodin holds promise as a

potential therapeutic agent for the treatment and prevention of

gastrointestinal disorders.

GI is a critical illness associated with high

morbidity and mortality. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and

ferroptosis are the key pathogenic events resulting from GI. The

present study first reported the following observations: i)

Atractylodin mitigated sepsis-induced GI. ii) PRDX3 protected

against sepsis-induced acute GI, mitochondrial oxidative damage and

ferroptosis. iii) SIRT3 deacetylates PRDX3 and can therefore

alleviate sepsis-induced acute GI mitochondrial oxidative damage

and ferroptosis.

The present study revealed that atractylodin can

alleviate mitochondrial dysfunction and decrease ferroptosis in

sepsis-induced acute GI. In addition, it was found that the

mechanisms of atractylodin are associated with SIRT3/PRDX3

signaling. Together, the findings of the present study demonstrated

that atractylodin may serve as a promising therapeutic agent for

treating and preventing GI.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 81804035), the Project of Jiangsu

Provincial Administration of Chinese Medicine (grant no.

MS2023092), the Changzhou Sci and Tech Program (grant no.

CJ20239006) and the Youth Talent Technology Project of Changzhou

Health Commission (grant no. QN202137).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

MQC was responsible for investigation and resources.

JLW, HDZ and TTL were responsible for investigation. TW was

responsible for resources. YXH was responsible for validation,

investigation and writing the original draft. YB was responsible

for writing, reviewing and editing, resources, methodology,

investigation, funding acquisition and conceptualization. HG was

responsible for writing, reviewing and editing, validation,

resources and investigation. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript. YXH and MQI confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiments in the present study was

conducted in the Liyang Hospital of Chinese Medicine and approved

by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Liyang Hospital of

Chinese Medicine (Jiangsu, China; approval no.

2024LY-02-02-03).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Salomão R, Ferreira BL, Salomão MC, Santos

SS, Azevedo LCP and Brunialti M: Sepsis: Evolving concepts and

challenges. Braz J Med Biol Res. 52:e85952019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Deitch EA: Gut-origin sepsis: Evolution of

a concept. Surgeon. 10:350–356. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford

KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer

S, et al: Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and

mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the global burden of disease

study. Lancet. 395:200–211. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Clements TW, Tolonen M, Ball CG and

Kirkpatrick AW: Secondary peritonitis and intra-abdominal sepsis:

An increasingly global disease in search of better systemic

therapies. Scand J Surg. 110:139–149. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rittirsch D, Flierl MA and Ward PA:

Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 8:776–787.

2008. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zarjou A and Agarwal A: Sepsis and acute

kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 22:999–1006. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tadokoro T, Ikeda M, Ide T, Deguchi H,

Ikeda S, Okabe K, Ishikita A, Matsushima S, Koumura T, Yamada KI,

et al: Mitochondria-dependent ferroptosis plays a pivotal role in

doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. JCI Insight. 5:e1327472020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta

R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS,

et al: Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell

death. Cell. 149:1060–1072. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Li N, Wang W, Zhou H, Wu Q, Duan M, Liu C,

Wu H, Deng W, Shen D and Tang Q: Ferritinophagy-mediated

ferroptosis is involved in sepsis-induced cardiac injury. Free

Radic Biol Med. 160:303–318. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Li J, Lu K, Sun F, Tan S, Zhang X, Sheng

W, Hao W, Liu M, Lv W and Han W: Panaxydol attenuates ferroptosis

against LPS-induced acute lung injury in mice by Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1

pathway. J Transl Med. 19:962021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang Z, Sun R, Wang G, Chen Z, Li Y, Zhao

Y, Liu D, Zhao H, Zhang F, Yao J and Tian X: SIRT3-mediated

deacetylation of PRDX3 alleviates mitochondrial oxidative damage

and apoptosis induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Redox Biol. 28:1013432020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Xu S, Liu Y, Yang S, Fei W, Qin J, Lu W

and Xu J: FXN targeting induces cell death in ovarian cancer

stem-like cells through PRDX3-Mediated oxidative stress. iScience.

27:1105062024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tang F, Fan K, Wang K and Bian C:

Atractylodin attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung

injury by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and TLR4 pathways. J

Pharmacol Sci. 136:203–211. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Koonrungsesomboon N, Na-Bangchang K and

Karbwang J: Therapeutic potential and pharmacological activities of

Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. Asian Pac J Trop Med.

7:421–428. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Yu C, Xiong Y, Chen D, Li Y, Xu B, Lin Y,

Tang Z, Jiang C and Wang L: Ameliorative effects of atractylodin on

intestinal inflammation and co-occurring dysmotility in both

constipation and diarrhea prominent rats. Korean J Physiol

Pharmacol. 21:1–9. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Xu L, Zhou Y, Xu J, Xu X, Lu G, Lv Q, Wei

L, Deng X, Shen X, Feng H and Wang J: Anti-inflammatory,

antioxidant and anti-virulence roles of atractylodin in attenuating

Listeria monocytogenes infection. Front Immunol. 13:9770512022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lin YC, Yang CC, Lin CH, Hsia TC, Chao WC

and Lin CC: Atractylodin ameliorates ovalbumin-induced asthma in a

mouse model and exerts immunomodulatory effects on Th2 immunity and

dendritic cell function. Mol Med Rep. 22:4909–4918. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Qu L, Lin X, Liu C, Ke C, Zhou Z, Xu K,

Cao G and Liu Y: Atractylodin attenuates dextran sulfate

sodium-induced colitis by alleviating gut microbiota dysbiosis and

inhibiting inflammatory response through the MAPK pathway. Front

Pharmacol. 12:6653762021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Heo G, Kim Y, Kim EL, Park S, Rhee SH,

Jung JH and Im E: Atractylodin ameliorates colitis via PPARα

agonism. Int J Mol Sci. 24:8022023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Vitzthum LK, Nalawade V, Riviere P, Marar

M, Furnish T, Lin LA, Thompson R and Murphy JD: Impacts of an

opioid safety initiative on US veterans undergoing cancer

treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 114:753–760. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Nullens S, Staessens M, Peleman C, Plaeke

P, Francque SM, Lammens C, Malhotra-Kumar S, De Man J and De Winter

BY: Su1190 effect of gastrointestinal barrier protection on

sepsis-induced changes of intestinal motility, inflammation and

colonic permeability. Gastroenterology. 150:S4912016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Song GY, Kim SM, Back S, Yang SB and Yang

YM: Atractylodes lancea and its constituent, atractylodin,

ameliorates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease via AMPK activation. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 32:778–792. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Kuo WT, Odenwald MA, Turner JR and Zuo L:

Tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 as regulators of

epithelial proliferation and survival. Ann N Y Acad Sci.

1514:21–33. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Li S and Huang Y: Ferroptosis: An

iron-dependent cell death form linking metabolism, diseases, immune

cell and targeted therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 24:1–12. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Wu H, Wang F, Ta N, Zhang T and Gao W: The

multifaceted regulation of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Life

(Basel). 11:2222021.

|

|

26

|

Gu J, Liu T, Guo R, Zhang L and Yang M:

The coupling mechanism of mammalian mitochondrial complex I. Nat

Struct Mol Biol. 29:172–182. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Ryu KW, Fung TS, Baker DC, Saoi M, Park J,

Febres-Aldana CA, Aly RG, Cui R, Sharma A, Fu Y, et al: Cellular

ATP demand creates metabolically distinct subpopulations of

mitochondria. Nature. 635:746–754. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sazanov LA: A giant molecular proton pump:

structure and mechanism of respiratory complex I. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 16:375–388. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lee HJ, Svahn E, Swanson JM, Lepp H, Voth

GA, Brzezinski P and Gennis RB: Intricate role of water in proton

transport through cytochrome c oxidase. J Am Chem Soc.

132:16225–16239. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chen Y, Guo X, Zeng Y, Mo X, Hong S, He H,

Li J, Fatima S and Liu Q: Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial

iron overload and ferroptotic cell death. Sci Rep. 13:155152023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Dixon SJ and Olzmann JA: The cell biology

of ferroptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 25:424–442. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Bryk R, Griffin P and Nathan C:

Peroxynitrite reductase activity of bacterial peroxiredoxins.

Nature. 407:211–215. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kang SW, Chae HZ, Seo MS, Kim K, Baines IC

and Rhee SG: Mammalian peroxiredoxin isoforms can reduce hydrogen

peroxide generated in response to growth factors and tumor necrosis

factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 273:6297–6302. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Cox AG, Winterbourn CC and Hampton MB:

Mitochondrial peroxiredoxin involvement in antioxidant defence and

redox signalling. Biochem J. 425:313–325. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Peskin AV, Low FM, Paton LN, Maghzal GJ,

Hampton MB and Winterbourn CC: The high reactivity of peroxiredoxin

2 with H(2)O(2) is not reflected in its reaction with other

oxidants and thiol reagents. J Biol Chem. 282:11885–11892. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Nonn L, Berggren M and Powis G: Increased

expression of mitochondrial peroxiredoxin-3 (thioredoxin

peroxidase-2) protects cancer cells against hypoxia and

drug-induced hydrogen peroxide-dependent apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res.

1:682–689. 2003.

|

|

37

|

Lombard DB and Zwaans BM: SIRT3: As simple

as it seems? Gerontology. 60:56–64. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Hua L,

Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Schwer B, Lombard DB, Li Y, Bunkenborg J, Alt

FW, Denu JM, et al: SIRT3 deacetylates mitochondrial

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase 2 and regulates ketone body

production. Cell Metab. 12:654–661. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hebert AS, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Yu W,

Bailey DJ, Selen ES, Boersma MD, Carson JJ, Tonelli M, Balloon AJ,

Higbee AJ, et al: Calorie restriction and SIRT3 trigger global

reprogramming of the mitochondrial protein acetylome. Mol Cell.

49:186–199. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Liang J, Zhou C, Zhang C, Liang S, Zhou Z,

Zhou Z, Wu C, Zhao H, Meng X, Zou F, et al: Nicotinamide

mononucleotide attenuates airway epithelial barrier dysfunction via

inhibiting SIRT3 SUMOylation in asthma. Int Immunopharmacol.

127:1113282024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wang T, Cao Y, Zheng Q, Tu J, Zhou W, He

J, Zhong J, Chen Y, Wang J, Cai R, et al: SENP1-Sirt3 signaling

controls mitochondrial protein acetylation and metabolism. Mol

Cell. 75:823–834.e5. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Wang X, Shen T, Lian J, Deng K, Qu C, Li

E, Li G, Ren Y, Wang Z, Jiang Z, et al: Resveratrol reduces

ROS-induced ferroptosis by activating SIRT3 and compensating the

GSH/GPX4 pathway. Mol Med. 29:1372023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Na-Bangchang K, Kulma I, Plengsuriyakarn

T, Tharavanij T, Kotawng K, Chemung A, Muhamad N and Karbwang J:

Phase I clinical trial to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics

of capsule formulation of the standardized extract of

Atractylodes lancea. J Tradit Complement Med. 11:343–355.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Park SJ, Park J, Lee MJ, Seo JS, Ahn JY

and Cho JW: Time series analysis of delta neutrophil index as the

predictor of sepsis in patients with acute poisoning. Hum Exp

Toxicol. 39:86–94. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Geven C, Blet A, Kox M, Hartmann O,

Scigalla P, Zimmermann J, Marx G, Laterre PF, Mebazaa A and

Pickkers P: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised,

multicentre, proof-of-concept and dose-finding phase II clinical

trial to investigate the safety, tolerability and efficacy of

adrecizumab in patients with septic shock and elevated

adrenomedullin concentration (AdrenOSS-2). BMJ Open. 9:e0244752019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|