Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), characterized by irregular

and rapid heartbeat originating in the atria, poses a considerable

global health concern (1).

Currently, AF affects >33.5 million people worldwide, including

2.7–6.1 million people in the United States, and the prevalence of

AF is influenced by predisposing factors, including age,

hypertension, diabetes and structural heart disease (2). Furthermore, lifestyle factors such as

obesity and physical inactivity also markedly contribute to the

onset of AF, highlighting the potential for preventive strategies

(3). The complex interplay of

these risk factors contributes to the initiation and perpetuation

of AF, creating a challenging clinical landscape. Given its

association with cardiovascular complications, such as stroke and

heart failure, understanding the epidemiology of AF is key for

developing targeted interventions (4). Therefore, current research focuses on

elucidating the complex mechanisms of AF pathogenesis, developing

novel therapeutic interventions and refining prognostic assessment

tools (5,6).

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

(PPAR) signaling pathway, a nuclear receptor pathway regulating

various physiological processes such as energy metabolism, lipid

metabolism, inflammation, includes the ligand-activated

transcription factors PPARα, PPARβ/δ and PPARγ (7,8).

Activated by ligands such as fatty acids, PPARs form heterodimers

with retinoid X receptors and regulate target gene transcription

through PPAR response elements in DNA, impacting lipid metabolism,

glucose homeostasis, inflammation and cell differentiation

(9,10). Essential in metabolic regulation,

the PPAR pathway is a therapeutic target for diabetes,

cardiovascular disease and metabolic disorders (11). Zhu et al (12) demonstrated the role of the PPAR

pathway in AF: PPARα and PPARγ attenuate angiotensin (Ang)

II-induced AF and fibrosis in mice, demonstrated by the protective

effects of angiopoietin-like 4 treatment. Zheng et al

(13) further established a

connection between the PPAR signaling pathway and AF, identifying

mannose receptor C-type 2 as a key inhibitory gene that suppresses

AF progression, offering potential diagnostic and therapeutic

avenues. Xu et al (14)

highlighted the protective role of the PPAR-γ activator

pioglitazone in mitigating age-associated vulnerability to AF

through enhanced antioxidant potential and suppression of apoptosis

via mitochondrial signaling pathways in a rat model. The

aforementioned studies highlight the potential of the PPAR

signaling pathway as an important research area for understanding

and managing AF, providing potential therapeutic strategies.

Heat shock protein D 1 (HSPD1) encodes the

mitochondrial chaperonin protein, HSP60 (15). It is key for maintaining

mitochondrial protein folding, ensuring proper protein transport

within the mitochondria and contributing to cellular homeostasis

(16). Dysregulation of HSPD1 is

associated with a range of diseases, including neurodegenerative

disorder and cardiovascular diseases, as its expression can be

induced in response to cellular stress to protect cells from damage

(17). van Marion et al

(18) demonstrated that elevated

levels of HSPD1 in atrial tissue are associated with persistent

stages of AF. Altered levels of HSPA5 in the right atrial appendage

and HSPA1 in the left atrial appendage are associated with the

development of postoperative AF and AF recurrence following

arrhythmia surgery. Oc et al (19) investigated the association between

pre- and postoperative circulating HSP70 levels and the development

of AF following coronary artery bypass surgery; HSP70 may have a

protective effect only when localized in cells, but it loses this

protection when released into the blood. Meijering et al

(20) demonstrated the protective

role of HSPs, including HSPD1, in preventing electrical,

contractile and structural remodeling of cardiomyocytes. This

underscores the potential for upstream therapy to prevent AF

progression and recurrence by upregulating the heat shock response

system.

Given the importance of AF in cardiac etiology and

its complexity, the present study aimed to clarify the causes of AF

development, with a focus on the HSPD1 gene. Peptide hormone Ang II

stimulates the release of aldosterone and constriction of blood

vessels, which are key mechanisms in the regulation of blood

pressure and fluid balance (21).

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of HSPD1

knockdown on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced fibrotic response of

cardiac fibroblasts (CF), including evaluation of cell viability,

expression of inflammatory and AF-related markers. In addition, the

potential regulatory association between HSPD1 and PPAR signaling

pathways in AF was explored. The present study aimed to enhance the

understanding of the pathogenesis of AF and suggest potential

therapeutic targets.

Materials and methods

AF-related datasets

A total of two gene expression datasets associated

with AF were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus

(ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/; accession nos. GSE31821 and GSE14975). The

GSE31821 dataset contains four AF samples (three from the auricle

of a patient with AF and one from the pulmonary vein of a patient

with AF) and two control samples. From this dataset, three AF

samples (auricles from patients with AF) and two control samples

were selected for analysis. The GSE14975 dataset includes 5 AF and

five samples of patients with sinus rhythm (as normal controls).

The data samples were all downloaded in MINiML format.

Screening and enrichment analysis of

differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the GSE31821 dataset

Differential expression analysis was performed on

five samples in the GSE31821 dataset using the Limma package

(version 3.52.4) in R (version 4.2.2;

bioconductor.org/packages/limma/). The threshold for fold change

was >1.3 or <0.77 with a significance level of P<0.05 to

identify DEGs. Subsequently, the Database for Annotation,

Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) database

(david.ncifcrf.gov/) was used to perform Gene Ontology (GO) and

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (22) enrichment analysis. GO includes

biological process (BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular

function (MF).

Candidate gene identification and

expression analysis in AF

To explore the interactions between DEGs,

protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis was performed

using the Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING)

database (string-db.org/). The resulting network was visualized

with Cytoscape (version 3.8.0; cytoscape.org/), using the maximum

correlation criterion (MCC), maximum neighborhood component (MNC)

and degree algorithms to identify key nodes. To determine the

commonalities between the top 10 genes identified by MCC, MNC and

degree algorithms, the Venn diagram tool from the Bioinformatics

& Evolutionary Genomics platform

(bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/) was employed for

intersection analysis. Using the GSE31821 and GSE14975 datasets,

the expression patterns of overlapping genes were investigated in

normal and AF samples. The results were visualized with the R tool

ggplot2 (version 3.4.0; ggplot2.tidyverse.org/).

Cell lines and culture

Rat CFs were obtained from Stemrecell (Shanghai)

Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (cat. no. STM-CE-3303). The rat CFs were

all cells that had been passaged ≤3 times. They were cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum

(FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 5%

CO2 at 37°C.

Cell treatment and transfection

To elucidate its effects, Ang II was administered to

CFs at 1, 10, 100 nM and 1 and 10 µM for 6, 12, 24 and 48 h at

37°C. To activate the PPAR signaling pathway, CFs were exposed to

10 µM thiazolidinedione (TZD; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 48 h

at 37°C. CFs were cultivated in six-well plates; 2×105

cells/well were seeded in 24-well plates for transfection. Specific

small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting HSPD1 and negative control

siRNA (both purchased from GenePharma, Shanghai, China) was

transfected into CFs to achieve knockdown of HSPD1 expression. To

enable effective knockdown of HSPD1, cells were cultured for 48 h

after transfection to allow for effective knockdown of HSPD1. siRNA

sequences for si-HSPD1 and si-negative control (NC) were used at a

final concentration of 80 µM, with sequences as follows:

si-HSPD1-1: forward: 5′-GGGCCAAAGGGAAGAACAGUGAUUA-3′ and reverse:

5′-UAAUCACUGUUCUUCCCUUUGGCCC-3′; si-HSPD1-2: Forward:

5′-GGAGAGGUGUGAUGUUGGCUGUUGA-3′ and reverse:

5′-UCAACAGCCAACAUCACACCUCUCC-3′ and si-NC: forward:

5′-GGGAAGAGGAAAGCAGAGUACCUUA-3′ and reverse:

5′-UAAGGUACUCUGCUUUCCUCUUCCC-3′. Following the manufacturer's

instructions, cells were transfected using

Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), and subsequent experiments were conducted 48 h

post-transfection at 37°C'.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR

Total RNA was extracted from 1×106 CFs

using TRIzol® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. For cDNA synthesis, a PrimeScript

RT kit (Takara Bio, Inc.) was used at 42°C for 30 min, followed by

85°C for 5 min to inactivate the enzyme qPCR was performed with the

StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix

(both Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Gene expression levels were

quantified and normalized to GAPDH. All target expression levels

were computed with the 2−ΔΔCq method. Thermocycling

conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 30

sec, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec.

The primer sequences used are listed in Table I. ACTA2 is the gene encoding

α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA). COL1A1 is the gene encoding Collagen

I. COL3A1 is the gene encoding COL3A1.

| Table I.Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. |

Table I.

Primer sequences for reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Gene | Direction | Sequence,

5′à3′ |

|---|

| HSPD1 |

|

|

|

| Forward |

CCAGCCTTGGATTCATT |

|

| Reverse |

CAAGCATGGCATCATAGCC |

| Col1a1 |

|

|

|

| Forward |

TCCTGCCGATGTCGCTATCC |

|

| Reverse |

TCGTGCAGCCATCCACAA |

| Col3a1 |

|

|

|

| Forward |

GCCTTCTACACCTGCTCCTG |

|

| Reverse |

AGCCACCCATTCCTCCGACT |

| ACTA2 | Forward |

GAGCGTGGCTATTCCTTCGTG |

|

| Reverse |

CAGTGGCCATCTCATTTTCAA |

|

|

| AGT |

| GAPDH |

|

|

|

| Forward |

CAATCCTGGGCGGTACAACT |

|

| Reverse |

TACGGCCAAATCCGTTCACA |

Western blotting (WB)

WB was performed using protein lysates extracted

from 1×106 CFs with RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with protease and phosphatase

inhibitors. The concentration of protein was quantified with the

BCA protein assay kit. Subsequently, 30 µg/lane total protein was

loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and the separated proteins were

transferred onto PVDF membranes (MilliporeSigma). Blocking of

membranes was performed out with 5% skimmed milk at room

temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, membranes were incubated

overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against HSPD1 (Abcam,

ab190828), Collagen I (Abcam, ab138492), Collagen III (Abcam,

ab184993), α-SMA (Cell Signaling Technology, #14968), atrial

natriuretic peptide (ANP) (Abcam, ab225844), MMP-2 (Abcam,

ab92536), PPARα (Abcam, ab314112), PPARγ (Abcam, ab272718),

carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-1; Cell Signaling Technology,

#41803), sirtuin (SIRT) 3 (Abcam, ab246522) and β-major

histocompatibility complex (MHC) (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.;

cat. no. #64038) (all 1:1,000), along with the respective

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L

secondary antibody (1:2,000; Abcam, ab6721) at room temperature for

1 h. GAPDH (Abcam, 1:5,000) served as an internal loading control.

Visualization of protein bands was performed using an enhanced

chemiluminescence kit (BOSTER, Wuhan, China), and ChemiDoc imaging

system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Densitometric analysis of the

bands was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health; http://imagej.nih.gov/).

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Viability of CFs was assessed using the CCK-8 assay

(Dojindo Europe GmbH). CFs were cultivated at a density of

5×103 cells/well in 96-well plates 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24 h prior to

treatment. Following the aforementioned treatments, 10 µl CCK-8

solution was added for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2

atmosphere to facilitate the reaction. The absorbance was measured

at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.).

Cell migration assay

Cell migration was evaluated using Transwell assay.

Transfected CF cells (5×104 cells/well) were suspended

in serum-free DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in

the upper chamber of Transwell plates. The lower chamber contained

medium with 10% FBS. After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, migrated

cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for

30 min and stained with DAPI (1 µg/ml) for 10 min at room

temperature. The number of migrated cells was determined by

counting the nuclei in five randomly selected fields of view under

an inverted fluorescence microscope (magnification, ×200).

ELISA

Cell culture supernatant were collected by

centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell

debris, and were subsequently diluted 1:2 with the sample diluent

provided in the ELISA kit. TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8 levels were

determined using ELISA kits (Cusabio, Technology, LLC), according

to the manufacturers' instructions: TNF-α (CSB-E11987r, Cusabio

Technology LLC, Wuhan, China), IL-1β (CSB-E08055r, Cusabio

Technology LLC, Wuhan, China), and IL-8 (MBS8579416, MyBiosource,

USA). The enzyme-linked secondary antibody (Abcam, ab6721, 1:5,000)

was added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After three

wash steps with 1×PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20 (each for 5 min at

room temperature), the wells were incubated with TMB

(3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate solution for 15 min at

room temperature. A stop solution was added to and then absorbance

at the 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The

concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8 were determined using a

standard curve generated using standards of known

concentration.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software

(version 4.2.2; r-project.org/). Data are presented as the mean ±

SD of triplicate experiments. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

followed by Tukey's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

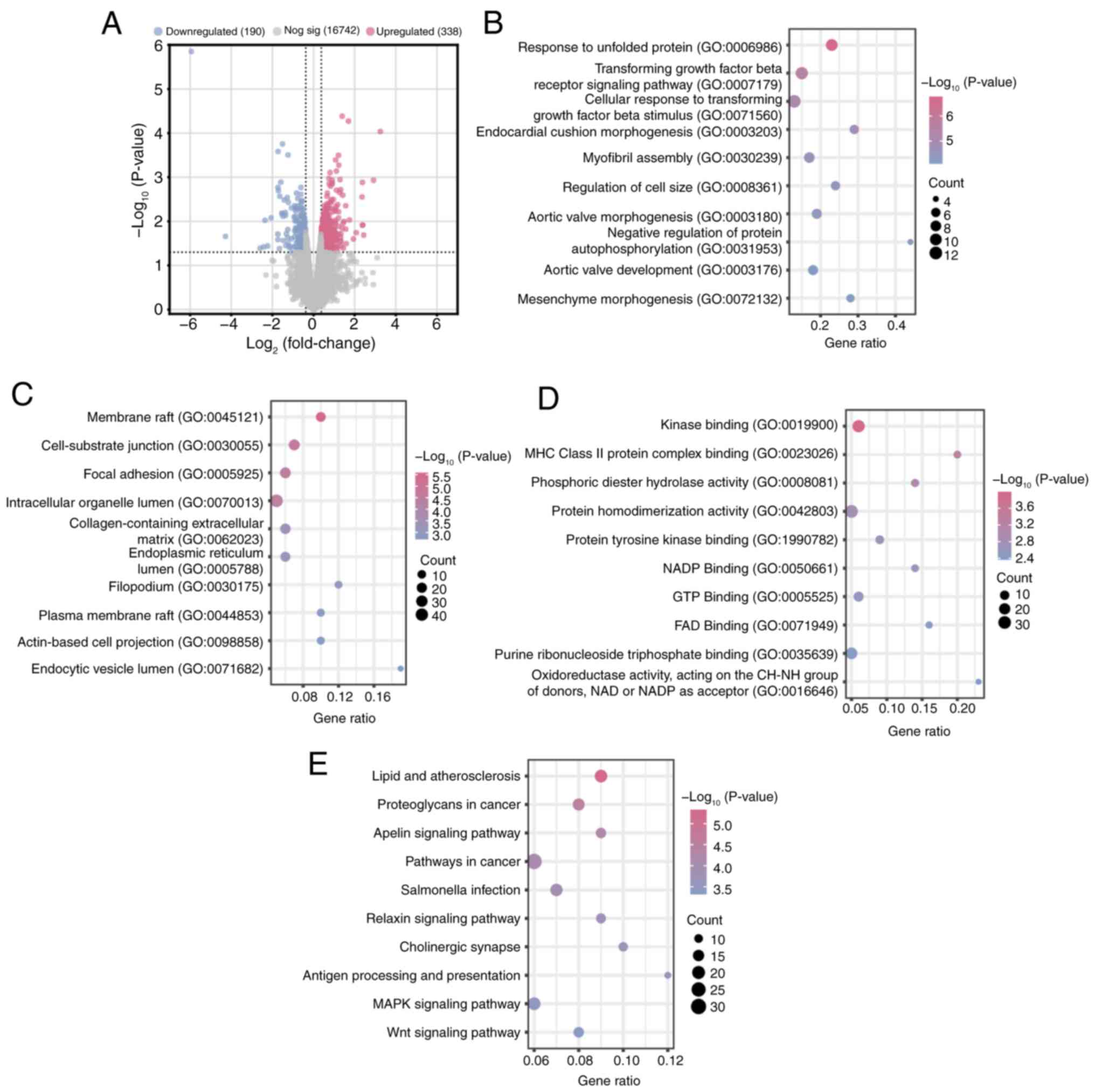

DEGs in the GSE318221 dataset are

enriched in inflammation-and remodeling-related pathways in AF

Using the R programming package, 338 up- and 190

downregulated DEGs were identified from cases and normal samples

within the GSE318221 dataset (Fig.

1A). DEGs were subjected to GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

using the DAVID database (Fig.

1B-E). The enriched terms included ‘myofibril assembly’ and

‘regulation of cell size’ (BP), ‘membrane raft’ and ‘focal

adhesion’ (CC), ‘NADP binding’ and ‘kinase binding’ (MF).

Additionally, the DEGs were significantly enriched in key pathways

such as ‘lipid and atherosclerosis’, ‘MAPK signaling pathway’ and

‘Wnt signaling pathway’, highlighting their potential roles in the

pathogenesis of AF.

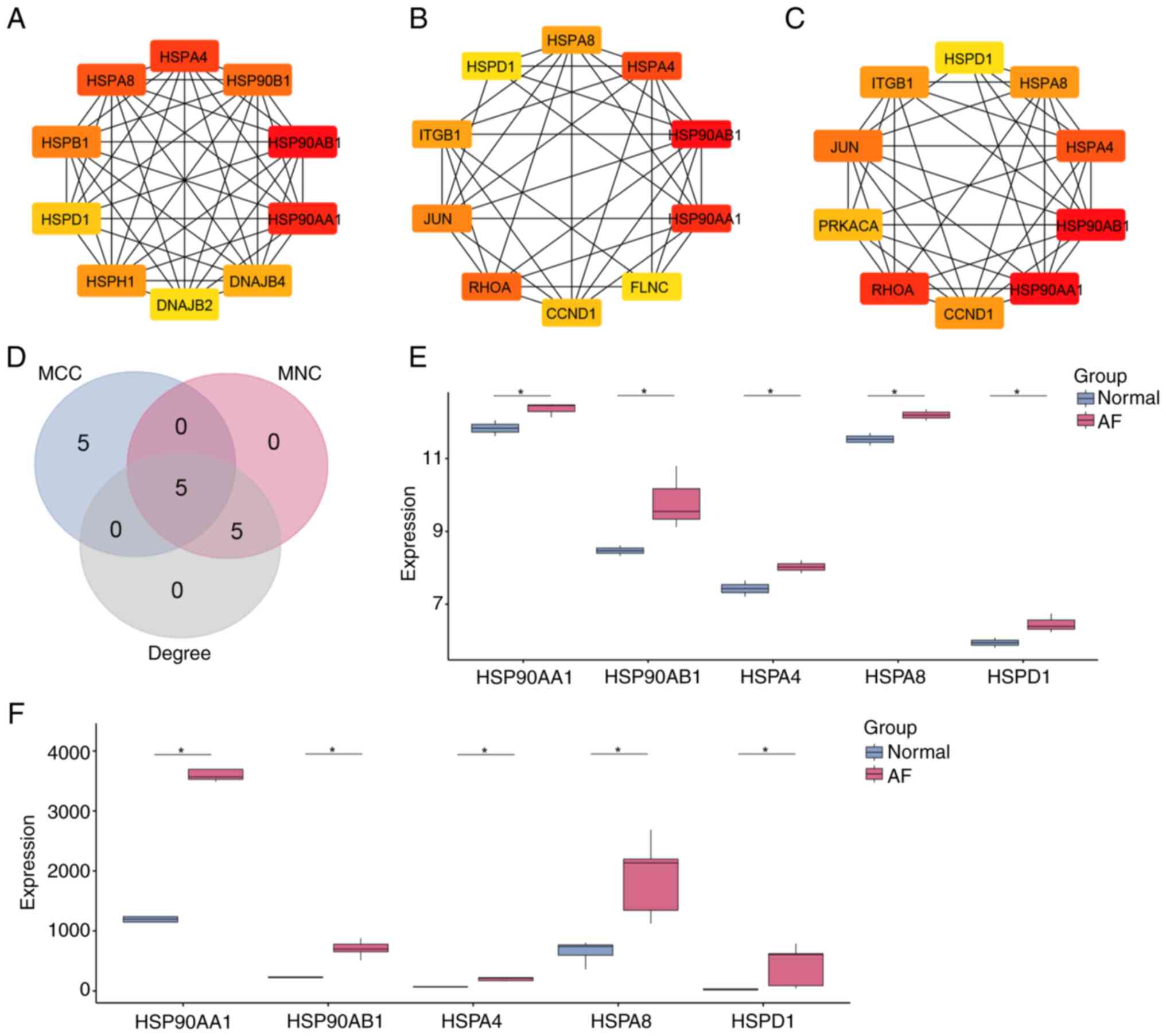

HSPD1 is a hub gene in AF

PPI network analysis was performed using the STRING

database on GSE31821 DEGs, and Cytoscape software visualized the

top 10 genes detected by MCC, MNC and degree algorithms (Fig. 2A-C). Specifically, the MCC network

encompassed 10 nodes and 44 edges, the MNC network comprised 10

nodes and 36 edges and the degree network included 10 nodes and 38

edges. Intersection analysis revealed five overlapping genes among

the top 10 genes identified in the MCC, MNC and degree networks

(Fig. 2D). Further investigation

of expression patterns within AF samples in the GSE31821 and

GSE14975 datasets revealed that five genes (HSP90AA1, HSP90AB1,

HSPA4, HSPA8 and HSPD1) were significantly upregulated (Fig. 2E and F), suggesting their potential

as targets for therapeutic intervention in AF. Among the five

overlapping genes, the roles of HSP90AA1, HSP90AB1, HSPA4 and HSPA8

in AF have been well-documented in previous studies (23–26).

In contrast, the function of HSPD1 in AF remains largely

unexplored. Therefore, HSPD1 was selected as the hub gene for

further investigation in this study.

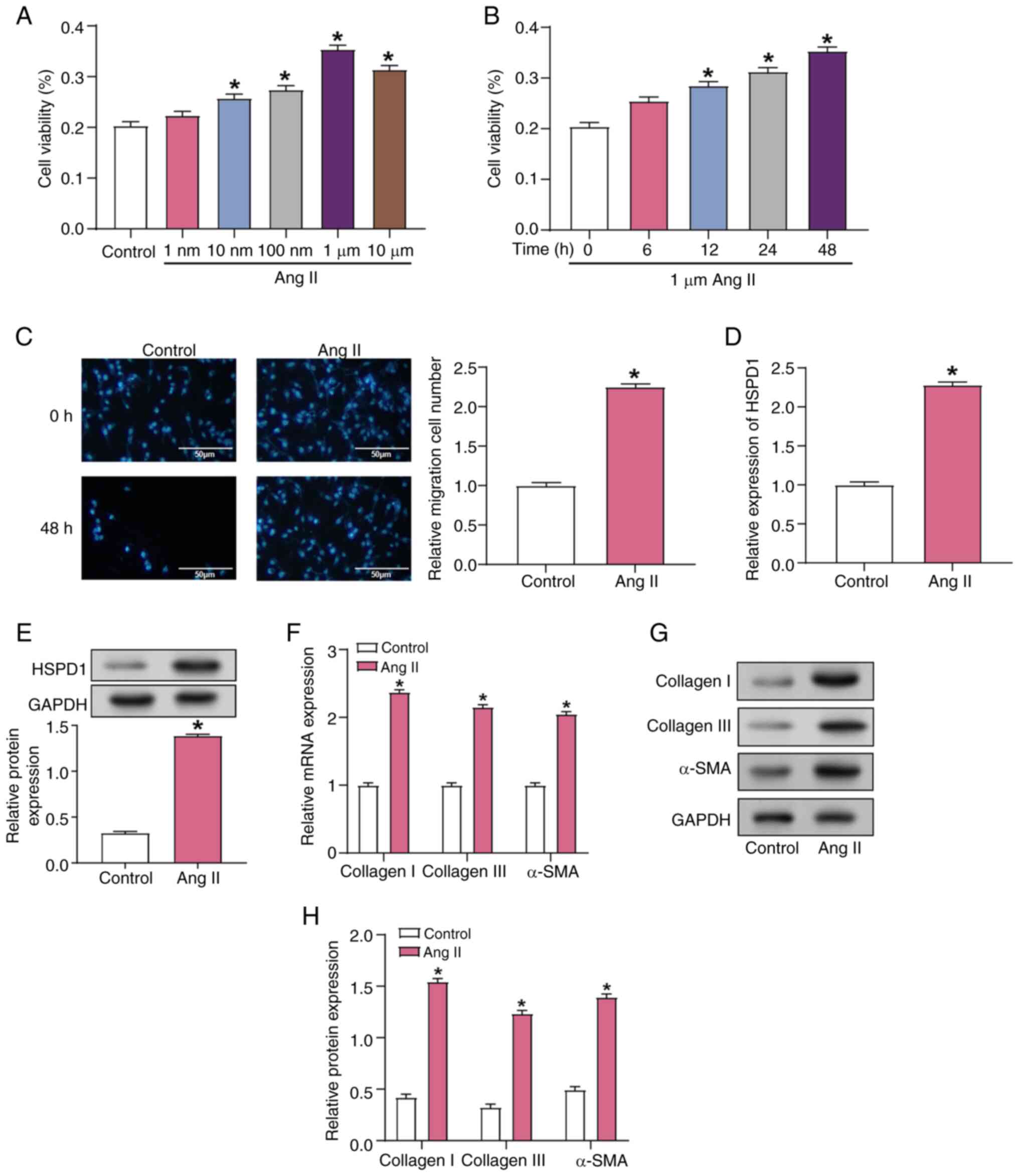

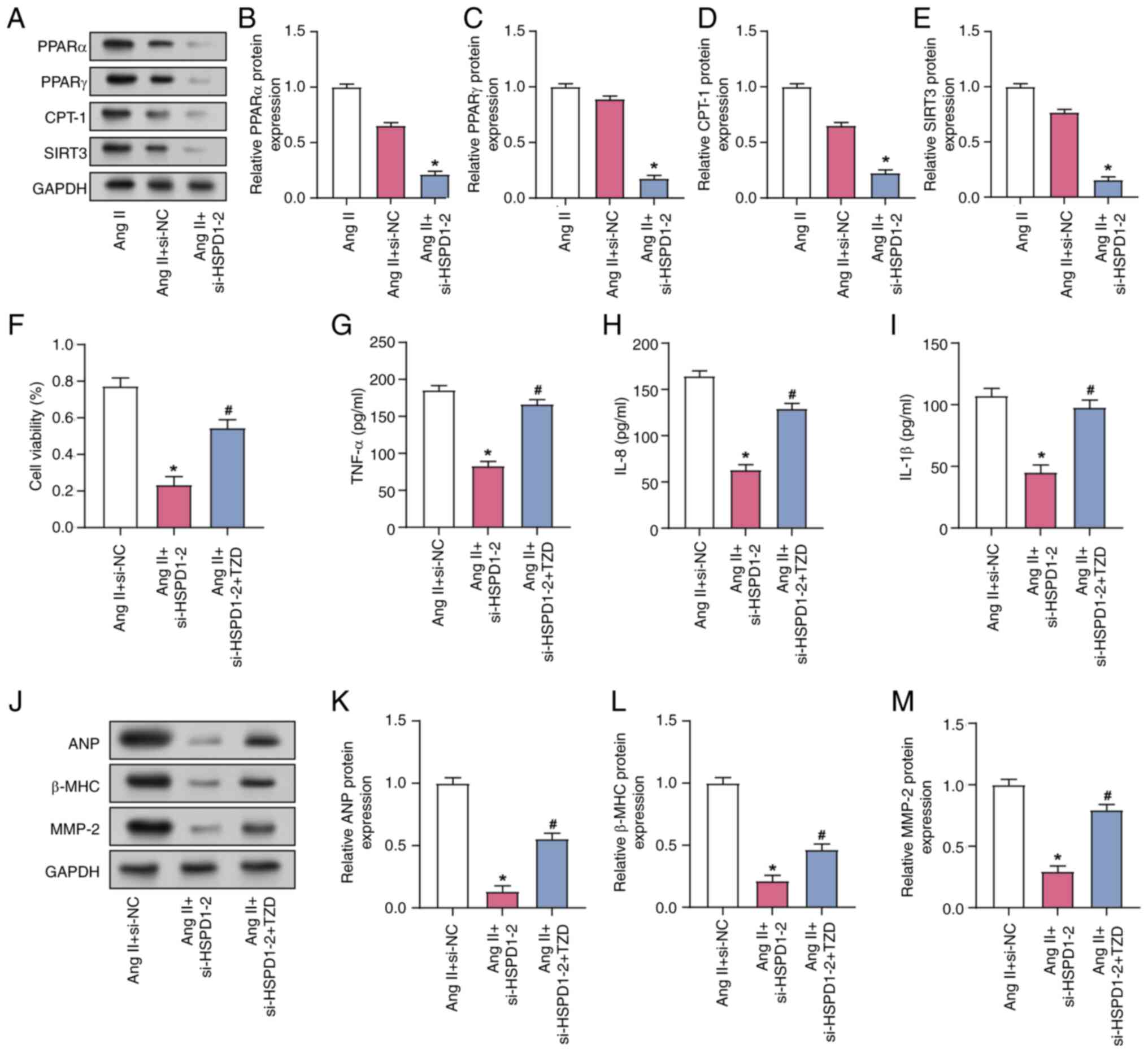

Ang II enhances CF activation and

fibrosis marker expression

Notably, a significant increase in CF viability was

observed 24 h after exposure to Ang II at concentrations greater

than 1 nM (Fig. 3A). Cell

viability continued to increase over time and reached its highest

recorded level at 48 h following induction with 1 µM Ang II

(Fig. 3B). The migratory capacity

of CFs was assessed using Transwell assay, demonstrating a notable

rise in cell migration following induction with 1 µM Ang II for 48

h (Fig. 3C). RT-qPCR and WB data

revealed a substantial upregulation of HSPD1 expression in CFs 48 h

post-induction with 1 µM Ang II (Fig.

3D and E). Additionally, collagen I and III and α-SMA

expression levels were significantly increased in CFs following 48

h induction with 1 µM Ang II, as demonstrated by both RT-qPCR and

WB (Fig. 3F-H). These findings

underscore the key role of Ang II in regulating CF viability,

migration and expression of fibrosis-related markers, elucidating

its mechanism of action in cardiac fibrosis.

| Figure 3.Effects of Ang II induction on

fibrosis in CFs. (A) Viability of CFs treated with different

concentrations of Ang II for 24 h, measured using the Cell Counting

Kit-8 assay. *P<0.05 vs. the Control group. (B) Cell viability

of CFs treated with 1 µM Ang II for 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h.

*P<0.05 vs. the 1 µM Ang II for 0 h group. (C) Transwell assay

of CF migration after induction with 1 µM Ang II for 48 h. Scale

bar, 50 µm. *P<0.05 vs. the Control group. (D) mRNA and (E)

protein expression of HSPD1 in CF cells induced by 1 µM Ang

II for 48 h. *P<0.05 vs. the Control group. (F) mRNA expression

of collagen I, collagen III and α-SMA in CFs following induction

with 1 µM Ang II for 48 h. *P<0.05 vs. the Control group. (G)

Representative western blotting and (H) protein expression of

collagen I, collagen III and α-SMA in CFs following induction with

1 µM Ang II for 48 h. *P<0.05 vs. Control group Ang II,

angiotensin II; CF, cardiac fibroblast; HSPD1, heat shock protein

D1. |

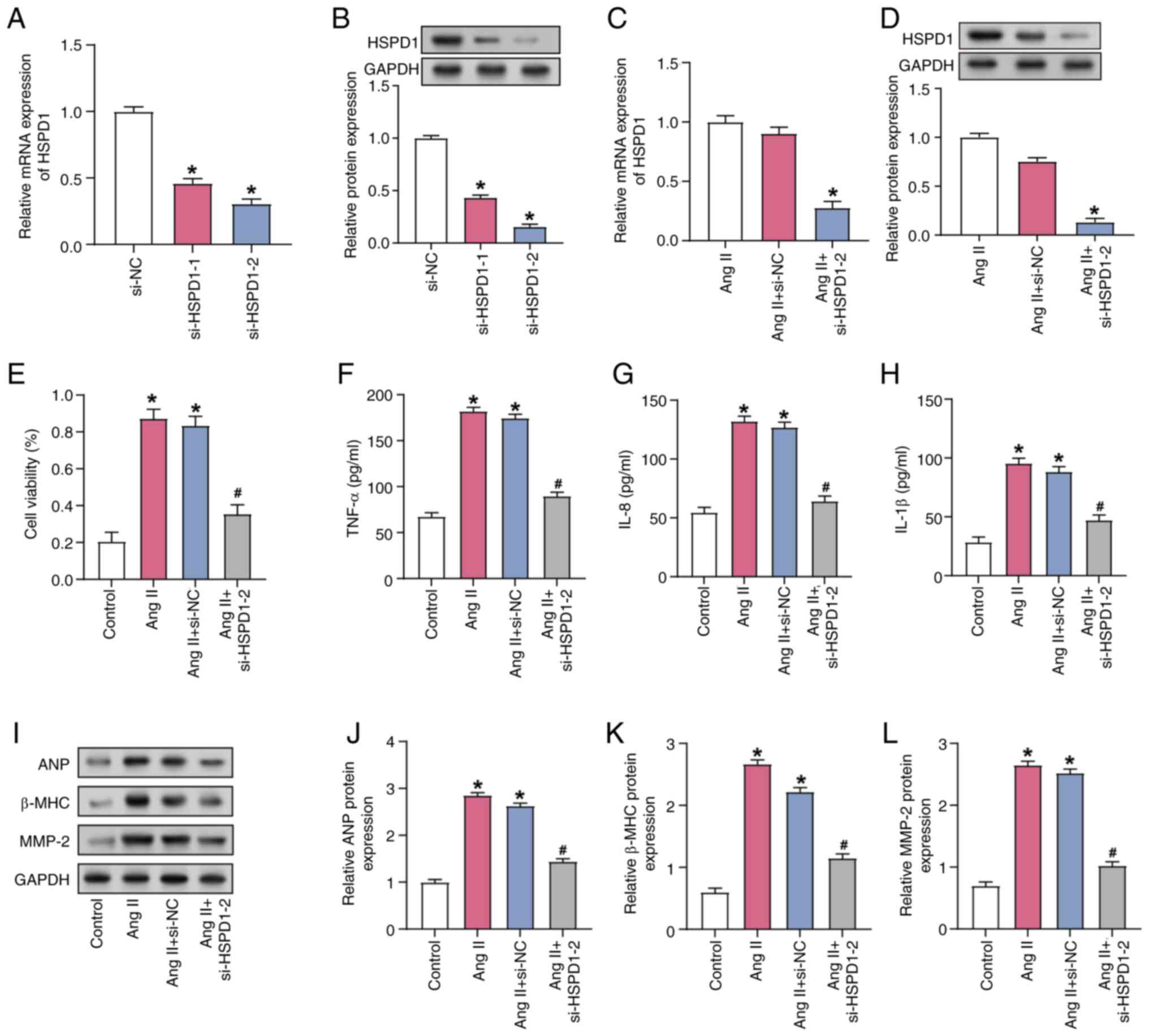

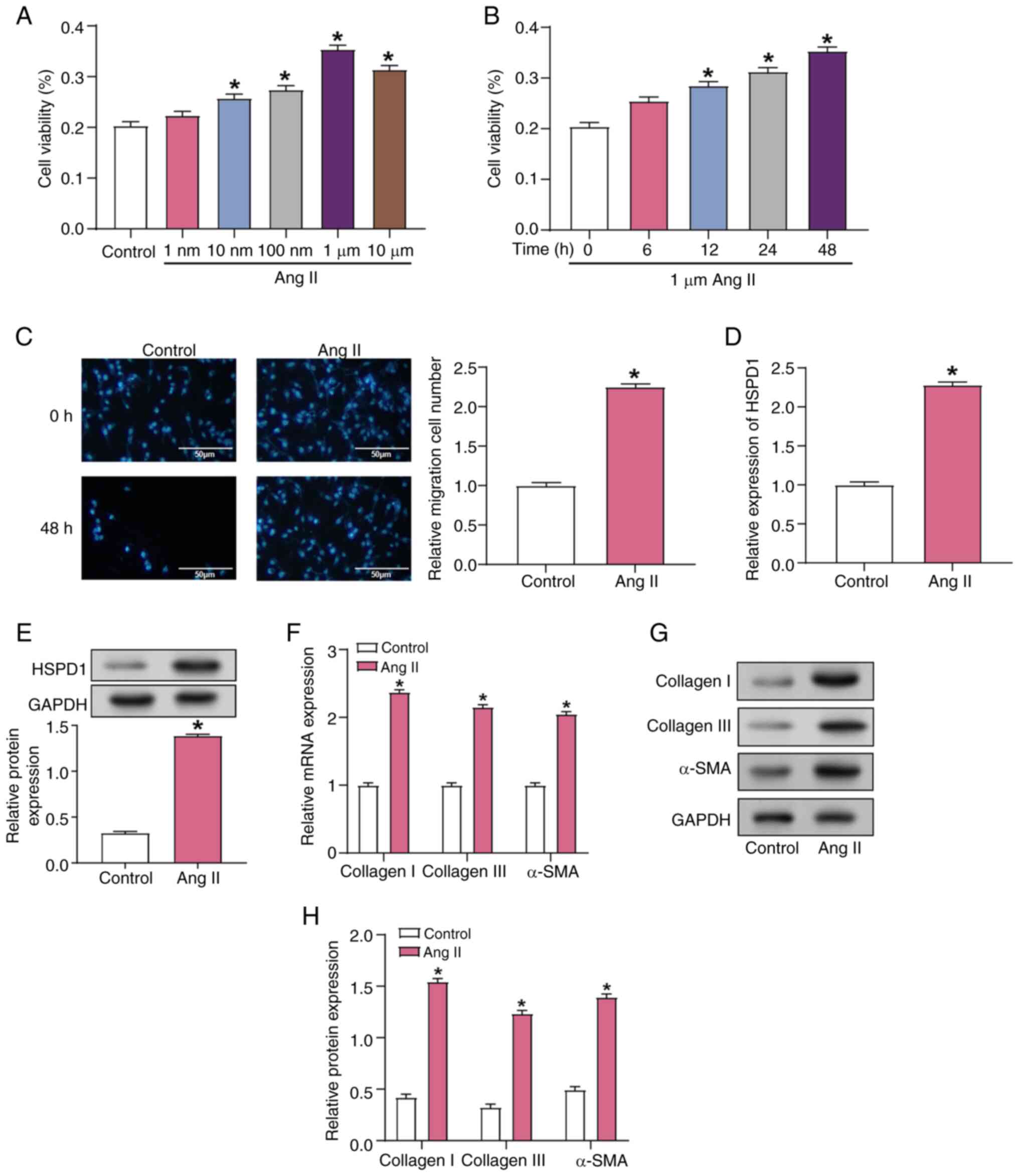

Downregulation of HSPD1 alleviates the

impact of Ang II induction on CF cell function

RT-qPCR and WB verified knockdown efficiency of

HSPD1, demonstrating the knockdown efficiency of si-HSPD1-2

was more pronounced (Fig. 4A and

B). HSPD1 expression in CFs was significantly decreased after

transfection with si-HSPD1-2 compared with Ang II induction alone,

as evidenced by both RT-qPCR and WB (Fig. 4C and D). Furthermore, Ang II

induction resulted in a significant increase in CF viability,

whereas HSPD1 knockdown alleviated this increase (Fig. 4E). ELISA demonstrated that the

secretion of inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-8 and IL-1β)

significantly increased after induction by 1 µM Ang II, while HSPD1

knockdown attenuated this increase (Fig. 4F-H). Protein expression of

AF-associated markers (ANP, β-MHC and MMP-2) was significantly

upregulated following induction with 1 µM Ang II. However, HSPD1

knockdown attenuated Ang II-induced responses and decreased ANP,

β-MHC and MMP-2 levels, as observed by RT-qPCR and WB (Fig. 4I-L). This suggested that HSPD1

served a role in regulating CF cell viability, inflammatory

responses and AF-associated markers.

| Figure 4.Downregulation of HSPD1 improves Ang

II-induced AF. (A) mRNA and (B) protein expression of HSPD1 in

HSPD1-knockdown CFs. *P<0.05 vs. the si-NC group. (C)

mRNA and (D) protein expression of HSPD1 in CFs. *P<0.05 vs. the

Ang II+ si-NC group. (E) Cell viability of CFs was assessed by Cell

Counting Kit-8 assay. ELISA was used to detect the secretion of

inflammatory factors (F) TNF-α, (G) IL-8 and (H) IL-1β in CFs. (I)

Representative western blotting and protein expression of the

AF-associated markers (J) ANP, (K) β-MHC and (L) MMP-2 in CFs.

*P<0.05 vs. the Control group; #P<0.05 vs. the Ang

II+ si-NC group. AF, atrial fibrillation; Ang II, angiotensin II;

CF, cardiac fibroblast; si, small interfering; NC, negative

control; HSPD1, heat shock protein D1; ANP, atrial natriuretic

peptide; MHC, major histocompatibility complex. |

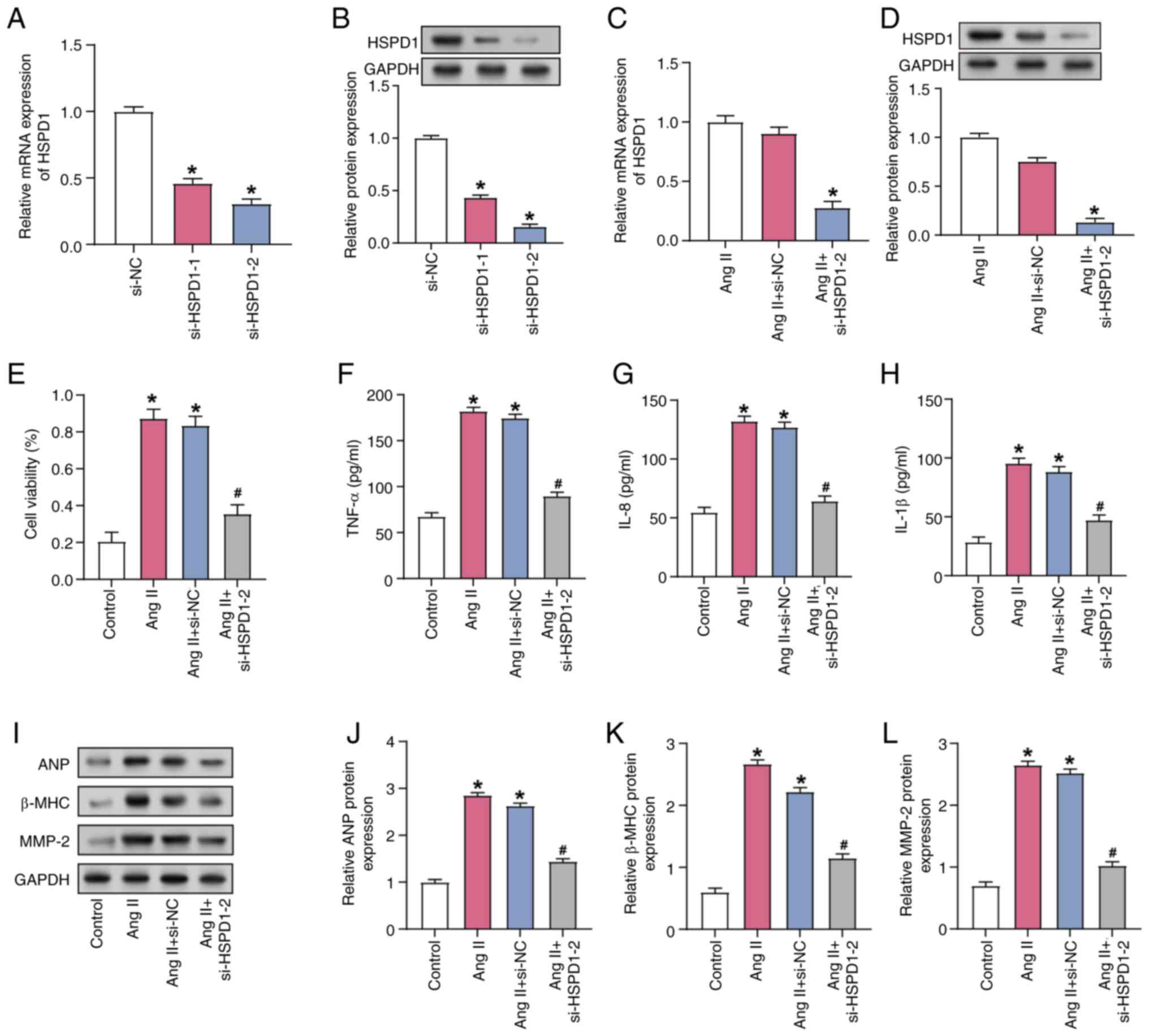

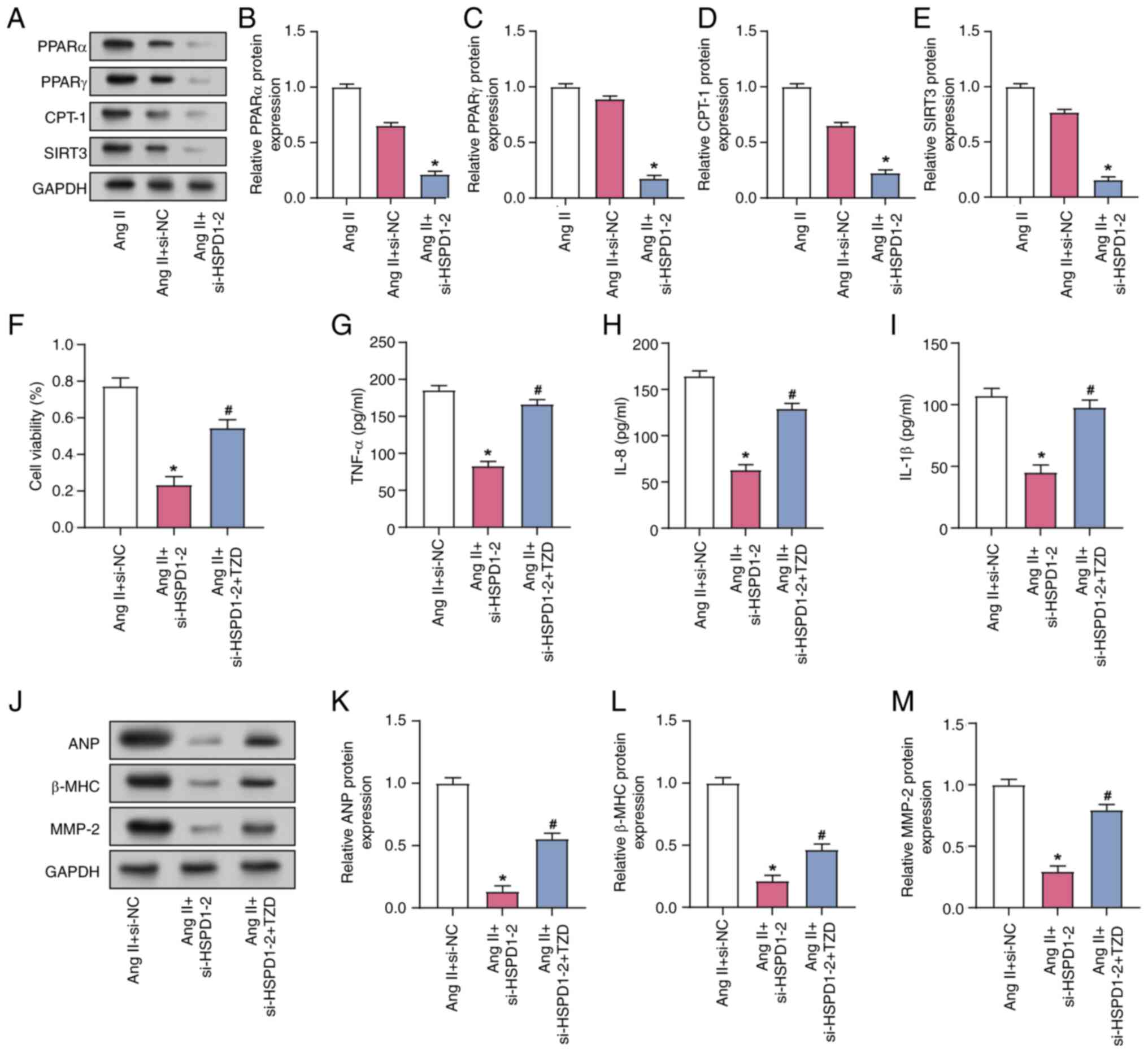

HSPD1 regulates Ang II-induced AF via

the PPAR signaling pathway

WB analysis revealed that HSPD1 knockdown

significantly decreased the expression of proteins involved in the

PPAR signaling pathway, including PPARα, SIRT3, CPT-1 and PPARγ, in

Ang II-induced CFs (Fig. 5A-E).

The cardioprotective effect of HSPD1 knockdown combined with

treatment with the PPAR activator TZD was investigated in Ang

II-induced CFs. Ang II-treated CFs exhibited increased viability,

which was significantly alleviated by siRNA-mediated knockdown of

HSPD1. TZD alleviated the effect of HSPD1 knockdown on Ang

II-induced CF (Fig. 5F). ELISA

demonstrated that HSPD1 knockdown led to a significant decrease in

the secretion of inflammatory factors TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-8 in Ang

II-induced CFs and addition of TZD prevented the increase of these

inflammatory factors (Fig. 5G-I).

HSPD1 knockdown significantly reduced the Ang II-induced protein

expression of AF-related markers ANP, β-MMP-2 and MHC; TZD

mitigated this reduction (Fig.

5J-M).

| Figure 5.Regulation of Ang II-induced AF by

HSPD1 via the PPAR signaling pathway. (A) Representative western

blotting and protein expression of PPAR signaling

pathway-associated proteins (B) PPARα, (C) PPARγ, (D) CPT-1 and (E)

SIRT3 in CFs. (F) Cell Counting Kit-8 assay of CF viability. ELISA

detection of the expression of the inflammatory factors (G) TNF-α,

(H) IL-8 and (I) IL-1β in CFs. (J) Representative western blotting

and protein expression of the AF markers (K) ANP, (L) β-MHC and (M)

MMP-2 in CFs. *P<0.05 vs. Ang II+ si-NC; #P<0.05

vs. the Ang II+si-HSPD1-2 group. AF, atrial fibrillation; TZD,

thiazolidinedione; CF, cardiac fibroblast; si, small interfering;

NC, negative control; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor; CPT-1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase I; SIRT, sirtuin;

ANP, atrial natriuretic peptide; MHC, major histocompatibility

complex. |

Discussion

AF poses a challenge due to its increasing

incidence, morbidity and mortality rates (27). Traditional diagnostic methods,

including electrocardiography and echocardiography, aid in AF

diagnosis but exhibit limitations in detecting asymptomatic or

paroxysmal cases, underscoring the need for more sensitive

biomarkers (28). Treatment

strategies primarily focus on heart rate and rhythm control,

anticoagulation therapy and invasive procedures such as catheter

ablation (29). In the present

study, HSPD1 was a key target gene, belonging to the HSP60 family.

Zhou et al (30)

highlighted the role of HSPD1 in inducing regulatory T cells and

modulating immunoregulation during helminth infection. Yang et

al (31) demonstrated the role

of the HSP60 family, including HSPD1, in regulating proteostasis

and the mitochondrial unfolded protein response in hepatic

inflammation and fibrosis, influenced by microRNA (miR)-29a

therapy. Additionally, Fu et al (32) identified HSPD1 as a potential hub

gene in the PPAR signaling pathway, suggesting its involvement in

regulating myocardial changes associated with volume overload. The

aforementioned studies suggest that integrating biomarkers into

risk stratification models can enhance predictive accuracy and

guide treatment decisions, thus offering a promising avenue for

improving AF management.

Based on the bioinformatics analysis of the GSE31821

dataset and the subsequent identification of DEGs, the present

study investigated the functional enrichment of these genes and

demonstrated enrichment in pathways such as ‘MAPK signaling

pathway’ and ‘Wnt signaling pathway’. This aligns with the study by

Zheng et al (33), which

elucidated the role of sympathetic activation in

hyperthyroidism-induced AF. The aforementioned study demonstrated

that cardiomyocyte apoptosis, orchestrated via the p38 MAPK

signaling pathway, is a pivotal mechanism in this context. Wolke

et al (34) demonstrated

the centrality of the WNT signaling pathway in the intricate

landscape of AF. This pathway influences diverse facets of AF,

ranging from its developmental phases to the maintenance and

progression of arrhythmia. This understanding of the molecular

mechanisms involved in AF pathogenesis provides a foundation for

devising targeted interventions. Zhao et al (35) demonstrated the protective role of

diminished α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression in

amyloid-β-induced atrial remodeling within the context of AF and

Alzheimer's disease (AD); inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative

stress mediated by oxidation of CaMKII/mitogen-activated protein

kinase/activator protein 1 in atrial cells and mice with AD

suggests a potential therapeutic avenue for mitigating atrial

remodeling in the context of AF and neurodegenerative

disorders.

PPI network analysis of the DEGs in the GSE31821

dataset revealed five candidate genes in AF, namely HSP90AA1,

HSP90AB1, HSPA4, HSPA8 and HSPD1. Expression analysis in the

GSE31821 and GSE14975 datasets demonstrated that all five genes

were highly expressed in AF samples. In addition to HSPD1, four

other genes are associated with heart disease. Fang et al

(23) identified HSP90AA1 as a key

gene involved in the pathogenesis of AF by affecting the lipid

biosynthetic pathway. This highlights the role of HSP90AA1 in the

metabolic disorders that lead to the development of AF. Xiao et

al (24) demonstrated that

dipyridamole, a vasodilator with antiplatelet and antithrombotic

properties, can interact with HSP90AB1 and may serve as an AF

treatment target, but the specific mechanism is still unclear.

Okamoto et al (25)

demonstrated that HSPA8 acts as an accessory protein of chloride

voltage-gated channel 2 (CLCN2) in rat pulmonary vein (PV)

cardiomyocytes, altering the CLCN2 current dependence on chloride

concentration and voltage activation, which may affect the

hyperpolarization-activated chloride current associated with

spontaneous activity, leading to AF. HSPA4 serves a key role in

cardiac health by maintaining protein quality control and

preventing cardiac hypertrophic growth, and may contribute to

protection against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by enhancing

autophagy and protein stability (26). The aforementioned findings suggest

a role for HSPs in cardiac disease and are consistent with findings

of the present study, highlighting the complex molecular mechanisms

associated with AF and potential targets for therapeutic

intervention.

Ang II, a key hormone for blood pressure regulation

and cardiovascular homeostasis, serves a key role in cardiac

fibrosis. In pathological conditions such as hypertension, elevated

Ang II levels induce excessive collagen deposition and structural

alterations in atrial tissue, fostering fibrotic remodeling

associated with AF development and progression (36,37).

The activation of the renin-Ang-aldosterone system, resulting in

heightened Ang II, markedly contributes to adverse atrial

structural changes, establishing a key association between Ang II,

cardiac fibrosis and AF pathogenesis (38).

Collagen I and collagen III, as key structural

proteins, confer strength and support to connective tissue, which

is essential for tissue architecture and wound healing (39). α-SMA, involved in smooth muscle

cell and myofibroblast contraction, participates in tissue

remodeling (40). Elevated levels

of collagen I, α-SMA and collagen III signify heightened fibrotic

activity, impacting tissue structure and function. These proteins

have been studied in various pathological contexts, notably in

cardiovascular diseases such as AF, where fibrosis serves a key

role in disease progression (39,41).

Collagen I, α-SMA and collagen III serves key roles in atrial

fibrosis associated with AF, as demonstrated by Su et al

(42), who reported increased

protein levels in response to Ang II stimulation. The

aforementioned study also revealed that H2S treatment

effectively mitigates fibrosis marker protein expression, offering

a potential therapeutic avenue through miR-133a/connective tissue

growth factor axis modulation. Additionally, Li et al

(43) revealed that overexpression

of miR-10a in AF-induced rats notably increases collagen I, α-SMA

and collagen III expression, promoting cardiac fibrosis via the

TGF-β1/Smads signaling pathway, while miR-10a downregulation exerts

opposite effects. Findings of the present study demonstrated the

effect of Ang II-induced CF on cell fibrosis, including increased

production of fibrosis-related proteins (collagen I, α-SMA and

collagen III) and improved survival and migration of CFs. These

findings suggest that Ang II is a major factor in the development

of cardiac fibrotic alterations. Nakamura et al (44) reveals that cyclic compressive

loading activates the Ang II type 1 receptor and stimulates

hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes via a

G-protein-dependent pathway. This highlights the role of Ang II in

cartilage biology, demonstrating its ability to induce tissue

remodeling via receptor-mediated signaling. This is consistent with

the results of the present study, which demonstrated that Ang II

increases the production of fibrosis-associated proteins (collagen

I, α-SMA and collagen III), leading to enhanced fibrosis activity

and affecting tissue structure and function. The aforementioned and

present studies underscore the importance of Ang II signaling in

driving cellular responses and tissue changes, suggesting that

targeting the Ang II pathway may hold therapeutic potential in

multiple tissue contexts.

Inflammatory factors, including TNF-α, IL-8 and

IL-1β, are key mediators of the inflammatory response. IL-1β is a

proinflammatory cytokine that aids in immune responses, TNF-α is a

cytokine that causes systemic inflammation and IL-8 is a chemokine

that draws immune cells to the site of inflammation (45). These inflammatory factors are

typically associated with the pathogenesis and progression of AF.

AF biomarkers, such as ANP, β-MHC and MMP-2, provide insights into

the structural and functional changes occurring in the atria. ANP

is released in response to atrial stretch and is indicative of

atrial enlargement and pressure overload (46). β-MHC is a cardiac muscle protein

associated with cardiac remodeling; its upregulation may signify

pathological changes in the heart (47).

MMP-2, a matrix metalloproteinase, serves a role in

tissue remodeling and is implicated in cardiac fibrosis and

structural alterations associated with AF (48). Investigating these indicators aids

in comprehending the molecular processes and potential treatment

options in AF. Thijssen et al (49) revealed increased expression of

β-MHC and a downregulation of overall MHC expression during

sustained AF in goats, indicating cardiomyocyte de-differentiation

and suggesting an early response to AF may involve ischemic stress.

Yang et al (50)

demonstrated that atorvastatin treatment in a rabbit model of

pacing-induced AF effectively prevents atrial remodeling by

reducing levels of atrial myeloperoxidase, MMP-2 and MMP-9.

Additionally, the study by Xia et al (51) on hypertensive rats revealed

pronounced alterations in PV electrophysiology and histology,

characterized by decreased expression of voltage-gated sodium

channel subunit Nav1.5 and Kir (Inward rectifyimg potassium

channel) 2.1, increased interstitial fibrosis and elevated levels

of fibrosis markers (TGF-β1, MMP-2 and collagen I). These findings

underscore the potential mechanistic association between altered

gene expression, atrial remodeling and PV changes in AF. The

present study demonstrated that HSPD1 downregulation mitigates the

pathological upregulation of AF-associated biomarkers and

inflammatory mediators in Ang II-stimulated CFs, suggesting that

modulating HSPD1 expression may be a promising therapeutic strategy

to counteract the inflammatory and fibrotic processes in AF. Based

on the widespread effects of Ang II on multiple types of tissue

(21), it is plausible that HSPD1

may be involved in other types of cardiovascular tissue, such as

the vasculature, where it could contribute to vascular remodeling

and hypertension. HSPD1 has been implicated in metabolic disorders,

including obesity and diabetes, where it contributes to

mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance (52,53).

These conditions are typically associated with systemic

inflammation and cardiovascular complications, suggesting that

HSPD1 may have broader systemic effects (54). Future research should explore

expression of HSPD1 and function in multiple types of tissue and

disease model to elucidate its systemic role and potential as a

therapeutic target.

A key function of the PPAR signaling pathway is in

regulating heart disease, affecting lipid metabolism, inflammation

and energy homeostasis in the heart (55). Studies have highlighted the

involvement of key proteins such as PPARα and PPARγ in regulating

cardiac function, with PPARα activation associated with improved

lipid utilization and decreased cardiac remodeling (10,56).

Conversely, the role of PPARγ in glucose metabolism and

inflammation underscores its therapeutic potential in diabetic

cardiomyopathy (57). CPT-1 is

regulated by PPARα and is key for mitochondrial fatty acid

oxidation, a key energy source for the heart (58). Furthermore, SIRT3 is affected by

PPARγ, involved in mitochondrial function and is associated with

cardiomyocyte protection against oxidative stress (59). Research on these proteins

highlights their potential as therapeutic targets for heart disease

(60,61), emphasizing the importance of the

PPAR signaling pathway in cardiovascular health. The present study

revealed that HSPD1 knockdown significantly decreased the

expression of PPAR signaling pathway-associated proteins in Ang

II-induced CFs. After HSPD1 knockdown, cell viability was

significantly decreased after Ang II treatment, whereas secretion

of inflammatory factors and levels of AF-related marker proteins

decreased. Application of the PPAR pathway activator TZD modulated

these effects, suggesting a regulatory interaction between HSPD1

and PPAR signaling pathways in mediating Ang II-induced AF. This

enhances the understanding of the role of HSPD1 in AF

pathophysiology and its potential as a target for therapeutic

intervention.

HSPD1 (also known as HSP60) is a mitochondrial

chaperonin involved in protein folding and maintaining cellular

homeostasis under stress (62).

While the present study investigated AF, the role of HSPD1 in CFs

and inflammation may also be relevant to hypertension. Hypertension

induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (63), which may lead to upregulated HSPD1

expression as a compensatory mechanism to protect cells.

Inflammation is a key contributor to hypertension (64). The present study demonstrated that

HSPD1 knockdown decreased the secretion of inflammatory cytokines

(for example, TNF-α, IL-8 and IL-1β) in Ang II-stimulated CFs. Ang

II induces inflammation and fibrosis, both central to

hypertension-associated complications (65). Thus, HSPD1 may promote hypertension

by regulating inflammation in cardiac and vascular tissue.

Hypertension is also associated with vascular fibrosis and

remodeling, which increase vascular stiffness and resistance

(36). The present study

demonstrated that HSPD1 upregulates fibrosis-associated markers

(for example, collagen I and III and α-SMA) in Ang II-induced CFs,

suggesting its role in hypertension through promoting fibrosis and

remodeling. Additionally, HSPD1 regulates the PPAR signaling

pathway, which is involved in lipid metabolism, inflammation and

energy homeostasis. PPAR signaling is implicated in hypertension,

with activators showing potential benefits in decreasing blood

pressure and vascular inflammation (9,58).

The downregulation of PPAR signaling proteins (PPARα, PPARγ, CPT-1

and SIRT3) following HSPD1 knockdown indicates that HSPD1 may

modulate hypertension via this pathway. In conclusion, the findings

of the present study highlight the potential role of HSPD1 in

hypertension pathogenesis. Future studies should explore HSPD1 as a

therapeutic target for hypertension by modulating mitochondrial

stress and enhancing PPAR pathway activity.

The present study identifying HSPD1 as a novel

therapeutic target for AF and potentially other types of

cardiovascular disease. By elucidating the role of HSPD1 in

mediating fibrosis, inflammation and PPAR signaling, the findings

of the present study provide novel insights into the pathogenesis

of AF and suggest that targeting HSPD1 may mitigate key

pathological processes such as fibrosis and inflammation.

Additionally, the involvement of HSPD1 in PPAR signaling highlights

its potential for broader cardiovascular applications, including

hypertension management. These results provide the groundwork for

future clinical research and development of targeted therapies

aimed at improving patient outcomes in AF and associated

conditions.

The present study has limitations. Although the

experiments reveal significant findings related to fibrosis,

inflammation and the expression of AF-associated proteins, they do

not fully capture the complexity of in vivo systems. The

absence of animal models limits the direct translation of the

findings to a physiological context. Future work should include

animal models to elucidate the role of HSPD1 in AF and to validate

the therapeutic potential of targeting the PPAR signaling

pathway.

In summary, the present study investigated the

regulatory role of HSPD1 in Ang II-induced AF and explored its

underlying mechanisms. The bioinformatics analysis revealed that

the expression of HSPD1 was significantly upregulated in AF

samples. In vitro assays demonstrated the important role of

HSPD1 in mediating the pathophysiological effects of Ang II on CFs,

emphasizing its impact on cell viability, inflammatory response and

expression of fibrosis-associated markers. Downregulation of HSPD1

attenuated Ang II-induced upregulation of key AF markers, thereby

attenuating fibrotic and inflammatory responses. Furthermore, the

present study demonstrated the regulatory role of HSPD1 on PPAR

signaling in the context of Ang II-induced AF, further elucidating

potential therapeutic avenues for AF management by integrating PPAR

signaling pathway activation via TZD. These insights contribute to

understanding the molecular complexity of AF development and

highlight HSPD1 as a potential therapeutic target.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Shanghai Municipal Health

Commission (grant no. 202340055).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YZ, ZZ, WZ and NX conceived and designed the study.

ZZ, WZ and JW collected data and contributed to data management.

YZ, QG, ZZ, LZ, JW and NC analyzed and interpreted data. SZ

interpreted data. YZ and SZ wrote the manuscript. ZZ and JW

critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual

content. YZ and ZZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Czabanski R, Horoba K, Wrobel J, Matonia

A, Martinek R, Kupka T, Jezewski M, Kahankova R, Jezewski J and

Leski JM: Detection of atrial fibrillation episodes in long-term

heart rhythm signals using a support vector machine. Sensors

(Basel). 20:7652020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bavishi A and Patel RB: Addressing

comorbidities in heart failure: Hypertension, atrial fibrillation,

and diabetes. Heart Fail Clin. 16:441–456. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Middeldorp ME, Ariyaratnam J, Lau D and

Sanders P: Lifestyle modifications for treatment of atrial

fibrillation. Heart. 106:325–332. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Carlisle MA, Fudim M, DeVore AD and

Piccini JP: Heart failure and atrial fibrillation, like fire and

fury. JACC Heart Fail. 7:447–456. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Karakasis P, Theofilis P, Vlachakis PK,

Korantzopoulos P, Patoulias D, Antoniadis AP and Fragakis N: Atrial

fibrosis in atrial fibrillation: Mechanistic insights, diagnostic

challenges, and emerging therapeutic targets. Int J Mol Sci.

26:2092024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Huang J, Wu B, Qin P, Cheng Y, Zhang Z and

Chen Y: Research on atrial fibrillation mechanisms and prediction

of therapeutic prospects: Focus on the autonomic nervous system

upstream pathways. Front Cardiovasc Med. 10:12704522023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Korbecki J, Bobiński R and Dutka M:

Self-regulation of the inflammatory response by peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors. Inflamm Res. 68:443–458. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Qiu YY, Zhang J, Zeng FY and Zhu YZ: Roles

of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) in the

pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Pharmacol

Res. 192:1067862023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tahri-Joutey M, Andreoletti P, Surapureddi

S, Nasser B, Cherkaoui-Malki M and Latruffe N: Mechanisms mediating

the regulation of peroxisomal fatty acid beta-oxidation by PPARα.

Int J Mol Sci. 22:89692021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Montaigne D, Butruille L and Staels B:

PPAR control of metabolism and cardiovascular functions. Nat Rev

Cardiol. 18:809–823. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Recinella L, Orlando G, Ferrante C,

Chiavaroli A, Brunetti L and Leone S: Adipokines: New potential

therapeutic target for obesity and metabolic, rheumatic, and

cardiovascular diseases. Front Physiol. 11:5789662020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhu X, Zhang X, Cong X, Zhu L and Ning Z:

ANGPTL4 attenuates Ang II-induced atrial fibrillation and fibrosis

in mice via PPAR pathway. Cardiol Res Pract. 2021:99353102021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zheng P, Zhang W, Wang J, Gong Q, Xu N and

Chen N: Bioinformatics and functional experiments reveal that MRC2

inhibits atrial fibrillation via the PPAR signaling pathway. J

Thorac Dis. 15:5625–5639. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Xu D, Murakoshi N, Igarashi M, Hirayama A,

Ito Y, Seo Y, Tada H and Aonuma K: PPAR-γ activator pioglitazone

prevents age-related atrial fibrillation susceptibility by

improving antioxidant capacity and reducing apoptosis in a rat

model. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 23:209–217. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Enomoto H, Mittal N, Inomata T, Arimura T,

Izumi T, Kimura A, Fukuda K and Makino S: Dilated

cardiomyopathy-linked heat shock protein family D member 1

mutations cause up-regulation of reactive oxygen species and

autophagy through mitochondrial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res.

117:1118–1131. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wachoski-Dark E, Zhao T, Khan A, Shutt TE

and Greenway SC: Mitochondrial protein homeostasis and

cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 23:33532022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Khafaga AF, Noreldin AE and Saadeldin IM:

Role of HSP in the pathogenesis of age-related inflammatory

diseases. Heat Shock Proteins in Inflammatory Diseases. Asea AAA

and Kaur P: Volume 22. Springer; Cham: pp. 341–371. 2020,

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

van Marion DMS, Ramos KS, Lanters EAH,

Bulte LB, Bogers AJJC, de Groot NMS and Brundel BJJM: Atrial heat

shock protein levels are associated with early postoperative and

persistence of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 18:1790–1798.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Oc M, Ucar HI, Pinar A, Akbulut B, Oc B,

Akyon Y, Kanbak M and Dogan R: Heat shock protein70: A new marker

for subsequent atrial fibrillation development? Artif Organs.

32:846–850. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Meijering RAM, Zhang D, Hoogstra-Berends

F, Henning R and Brundel BJJM: Loss of proteostatic control as a

substrate for atrial fibrillation: A novel target for upstream

therapy by heat shock proteins. Front Physiol. 3:362012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Nehme A, Zouein FA, Zayeri ZD and Zibara

K: An update on the tissue renin angiotensin system and its role in

physiology and pathology. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 6:142019.

|

|

22

|

Dennis G Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang

J, Gao W, Lane HC and Lempicki RA: DAVID: Database for annotation,

visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Boil. 4:P32003.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Fang Y, Liu L and Wang H: The four key

genes participated in and maintained atrial fibrillation process

via reprogramming lipid metabolism in AF patients. Front Genet.

13:8217542022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Xiao S, Zhou Y, Liu Q, Zhang T and Pan D:

Identification of pivotal MicroRNAs and target genes associated

with persistent atrial fibrillation based on bioinformatics

analysis. Comput Math Methods Med. 2021:66802112021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Okamoto Y, Nagasawa Y, Obara Y, Ishii K,

Takagi D and Ono K: Molecular identification of HSPA8 as an

accessory protein of a hyperpolarization-activated chloride channel

from rat pulmonary vein cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem.

294:16049–16061. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Marques Rodrigues D: The role of heat

shock protein A4 (HSPA4) in the heart. eDiss. 2023.

|

|

27

|

Rowin EJ, Link MS, Maron MS and Maron BJ:

Evolving contemporary management of atrial fibrillation in

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 148:1797–1811. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hesselkilde EZ, Carstensen H, Flethøj M,

Fenner M, Kruse DD, Sattler SM, Tfelt-Hansen J, Pehrson S,

Braunstein TH, Carlson J, et al: Longitudinal study of electrical,

functional and structural remodelling in an equine model of atrial

fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 19:2282019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Velleca M, Costa G, Goldstein LJ, Bishara

M, Ming Boo L and Sha Q: Management of atrial fibrillation in

Europe: Current care pathways and the clinical impact of

antiarrhythmic drugs and catheter ablation. EMJ Cardiol. 7:98–109.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zhou S, Jin X, Chen X, Zhu J, Xu Z, Wang

X, Liu F, Hu W, Zhou L and Su C: Heat shock protein 60 in eggs

specifically induces Tregs and reduces liver immunopathology in

mice with Schistosomiasis japonica. PLoS One. 10:e01391332015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Yang YL, Wang PW, Wang FS, Lin HY and

Huang YH: miR-29a modulates GSK3β/SIRT1-linked mitochondrial

proteostatic stress to ameliorate mouse non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 21:68842020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Fu Y, Zhao D, Zhou Y, Lu J, Kang L, Jiang

X, Xu R, Ding Z and Zou Y: Identification of differential

expression genes between volume and pressure overloaded hearts

based on bioinformatics analysis. Genes (Basel). 13:12762022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Zheng J, Zhao S, Yang Q, Wei Y, Li J and

Guo T: Sympathetic activation promotes cardiomyocyte apoptosis in a

rabbit susceptibility model of hyperthyroidism-induced atrial

fibrillation via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Crit Rev Eukaryot

Gene Expr. 33:17–27. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wolke C, Antileo E and Lendeckel U: WNT

signaling in atrial fibrillation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood).

246:1112–1120. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhao J, Yu L, Xue X, Xu Y, Huang T, Xu D,

Wang Z, Luo L and Wang H: Diminished α7 nicotinic acetylcholine

receptor (α7nAChR) rescues amyloid-β induced atrial remodeling by

oxi-CaMKII/MAPK/AP-1 axis-mediated mitochondrial oxidative stress.

Redox Biol. 59:1025942023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zeng X and Yang Y: Molecular mechanisms

underlying vascular remodeling in hypertension. Rev Cardiovasc Med.

25:722024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sygitowicz G, Maciejak-Jastrzębska A and

Sitkiewicz D: A review of the molecular mechanisms underlying

cardiac fibrosis and atrial fibrillation. J Clin Med. 10:44302021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Mirabito Colafella KM, Bovée DM and Danser

AHJ: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and its therapeutic

targets. Exp Eye Res. 186:1076802019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Singh D, Rai V and Agrawal DK: Regulation

of collagen I and collagen III in tissue injury and regeneration.

Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 7:5–16. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hinz B, McCulloch CA and Coelho NM:

Mechanical regulation of myofibroblast phenoconversion and collagen

contraction. Exp Cell Res. 379:119–128. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ma J, Chen Q and Ma S: Left atrial

fibrosis in atrial fibrillation: Mechanisms, clinical evaluation

and management. J Cell Mol Med. 25:2764–2775. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Su H, Su H, Liu CH, Hu HJ, Zhao JB, Zou T

and Tang YX: H2S inhibits atrial fibrillation-induced

atrial fibrosis through miR-133a/CTGF axis. Cytokine.

146:1555572021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Li PF, He RH, Shi SB, Li R, Wang QT, Rao

GT and Yang B: Modulation of miR-10a-mediated TGF-β1/Smads

signaling affects atrial fibrillation-induced cardiac fibrosis and

cardiac fibroblast proliferation. Biosci Rep. 39:BSR201819312019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Nakamura F, Tsukamoto I, Inoue S,

Hashimoto K and Akagi M: Cyclic compressive loading activates

angiotensin II type 1 receptor in articular chondrocytes and

stimulates hypertrophic differentiation through a

G-protein-dependent pathway. FEBS Open Bio. 8:962–973. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Soare AY, Durham ND, Gopal R, Tweel B,

Hoffman KW, Brown JA, O'Brien M, Bhardwaj N, Lim JK, Chen BK and

Swartz TH: P2X antagonists inhibit HIV-1 productive infection and

inflammatory cytokines interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-1β in a human

tonsil explant model. J Virol. 93:e01186–18. 2018.

|

|

46

|

Rao S, Pena C, Shurmur S and Nugent K:

Atrial natriuretic peptide: Structure, function, and physiological

effects: A narrative review. Curr Cardiol Rev.

17:e0511211910032021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Bai L, Zhao Y, Zhao L, Zhang M, Cai Z,

Yung KKL, Dong C and Li R: Ambient air PM2.5 exposure

induces heart injury and cardiac hypertrophy in rats through

regulation of miR-208a/b, α/β-MHC, and GATA4. Environ Toxicol

Pharmacol. 85:1036532021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Henriet P and Emonard H: Matrix

metalloproteinase-2: Not (just) a ‘hero’ of the past. Biochimie.

166:223–232. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Thijssen VLJL, van der Velden HMW, van

Ankeren EP, Ausma J, Allessie MA, Borgers M, van Eys GJJM and

Jongsma HJ: Analysis of altered gene expression during sustained

atrial fibrillation in the goat. Cardiovasc Res. 54:427–437. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Yang Q, Qi X, Dang Y, Li Y, Song X and Hao

X: Effects of atorvastatin on atrial remodeling in a rabbit model

of atrial fibrillation produced by rapid atrial pacing. BMC

Cardiovasc Disord. 16:1422016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Xia PP, Li LJ, Qi RD, Shi JJ, Ju WZ and

Chen ML: Electrical and histological remodeling of the pulmonary

vein in 2K1C hypertensive rats: Indication of initiation and

maintenance of atrial fibrillation. Anatol J Cardiol. 19:169–175.

2018.

|

|

52

|

Hauffe R, Rath M, Schell M, Ritter K,

Kappert K, Deubel S, Ott C, Jähnert M, Jonas W, Schürmann A and

Kleinridders A: HSP60 reduction protects against diet-induced

obesity by modulating energy metabolism in adipose tissue. Mol

Metab. 53:1012762021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Kleinridders A, Lauritzen HPMM, Ussar S,

Christensen JH, Mori MA, Bross P and Kahn CR: Leptin regulation of

Hsp60 impacts hypothalamic insulin signaling. J Clin Invest.

123:4667–4680. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Timofeev YS, Kiselev AR, Dzhioeva ON and

Drapkina OM: Heat shock proteins (HSPs) and cardiovascular

complications of obesity: Searching for potential biomarkers. Curr

Issues Mol Biol. 45:9378–9389. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Bougarne N, Weyers B, Desmet SJ, Deckers

J, Ray DW, Staels B and De Bosscher K: Molecular actions of PPARα

in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Endocr Rev. 39:760–802. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Wang X, Zhu XX, Jiao SY, Qi D, Yu BQ, Xie

GM, Liu Y, Song YT, Xu Q, Xu QB, et al: Cardiomyocyte peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor α is essential for energy

metabolism and extracellular matrix homeostasis during pressure

overload-induced cardiac remodeling. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

43:1231–1242. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Song F, Mao YJ, Hu Y, Zhao SS, Wang R, Wu

WY, Li GR, Wang Y and Li G: Acacetin attenuates diabetes-induced

cardiomyopathy by inhibiting oxidative stress and energy metabolism

via PPAR-α/AMPK pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 922:1749162022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Liu X, Xu X, Zhang T, Xu L, Tao H, Liu Y,

Zhang Y and Meng X: Fatty acid metabolism disorders and potential

therapeutic traditional Chinese medicines in cardiovascular

diseases. Phytother Res. 37:4976–4998. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Zhang J, Ren D, Fedorova J, He Z and Li J:

SIRT1/SIRT3 modulates redox homeostasis during ischemia/reperfusion

in the aging heart. Antioxidants (Basel). 9:8582020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Kvandová M, Majzúnová M and Dovinová I:

The role of PPARgamma in cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Res. 65

(Suppl 3):S343–S363. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Metzger JM, Matsoff HN, Zinnen AD,

Fleddermann RA, Bondarenko V, Simmons HA, Mejia A, Moore CF and

Emborg ME: Post mortem evaluation of inflammation, oxidative

stress, and PPARγ activation in a nonhuman primate model of cardiac

sympathetic neurodegeneration. PLoS One. 15:e02269992020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Singh MK, Shin Y, Han S, Ha J, Tiwari PK,

Kim SS and Kang I: Molecular chaperonin HSP60: Current

understanding and future prospects. Int J Mol Sci. 25:54832024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Pokharel MD, Marciano DP, Fu P, Franco MC,

Unwalla H, Tieu K, Fineman JR, Wang T and Black SM: Metabolic

reprogramming, oxidative stress, and pulmonary hypertension. Redox

Biol. 64:1027972023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Navaneethabalakrishnan S, Smith HL, Arenaz

CM, Goodlett BL, McDermott JG and Mitchell BM: Update on immune

mechanisms in hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 35:842–851. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Escobales N, Nuñez RE and Javadov S:

Mitochondrial angiotensin receptors and cardioprotective pathways.

Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 316:H1426–H438. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|