Introduction

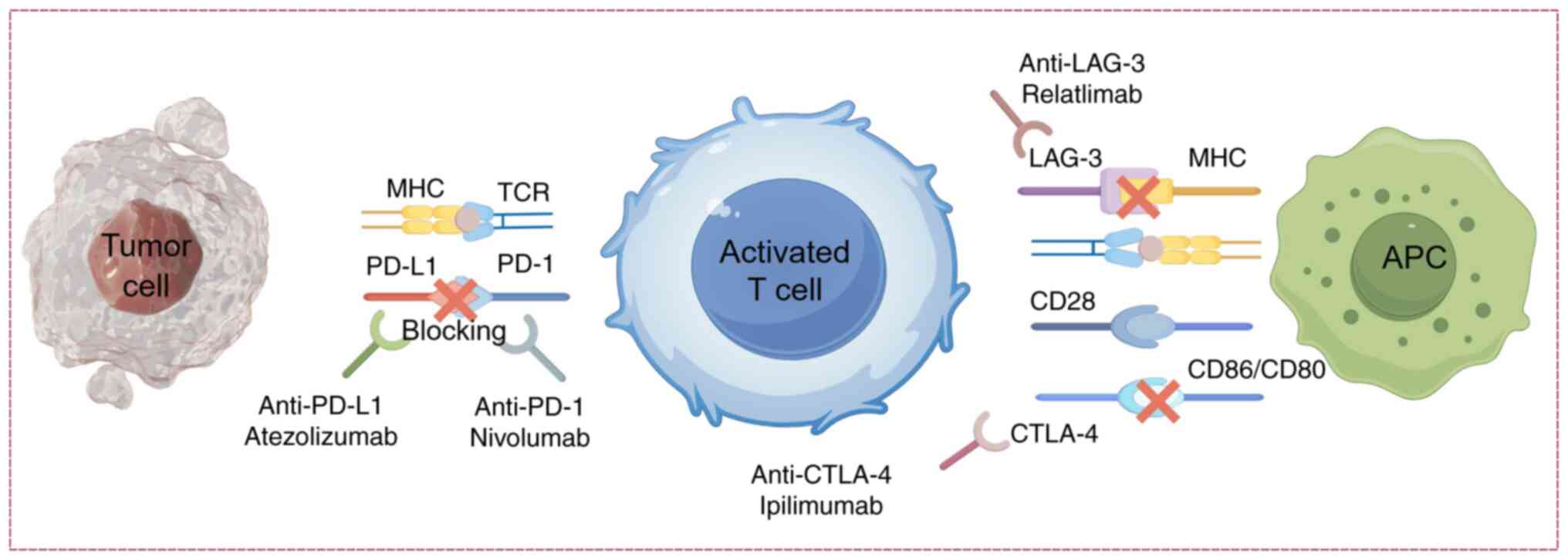

As the core regulatory mechanism of immune

homeostasis, immune checkpoints prevent autoimmune damage by

regulating T-cell activity (1).

However, in the tumor microenvironment, tumor cells evade immune

surveillance by overexpressing PD-L1, which engages PD-1 on

activated T cells, leading to functional suppression and T cell

exhaustion (2); this discovery has

driven the clinical translation of immune checkpoint inhibitors

(ICIs). As monoclonal antibody drugs, ICIs reactivate T

cell-mediated antitumor effects by blocking inhibitory signaling

pathways (3). Since the approval

of the first CTLA-4 inhibitor by the US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) in 2011, PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors have expanded

to the treatment of over a dozen solid tumors, including melanoma

and non-small cell lung cancer, markedly improving patient survival

rates (4). Notably, the 5-year

survival rate for advanced melanoma increased from 15% with

traditional therapies to 50% with the use of ipilimumab monotherapy

or combination regimens involving PD-1 inhibitors such as nivolumab

(5). However, alongside the

therapeutic breakthroughs, immune-related adverse events (irAEs)

have emerged as a new clinical challenge. Among these AEs,

cardiovascular toxicity, particularly ICI-related myocarditis, has

a high mortality rate of 46%, although it has an incidence of

<2% (6). The use of combination

therapy further increases the risk (3–5);

therefore, the early diagnosis and management of ICI-related

myocarditis have become critical issues in the field of cancer

immunotherapy (7–9).

Notably, the heart is considered a specific target

of immune attack (10); however,

the underlying reasons for the heightened susceptibility in

specific patient populations and the pathological mechanisms

driving ICI-related myocarditis remain incompletely elucidated. The

present review aimed to explore the immunopathological mechanisms

of ICI-related myocarditis. By summarizing the existing literature,

the review aimed to identify critical knowledge gaps in current

research and propose future directions, including the development

of novel therapeutic strategies and molecular targets. Ultimately,

this work aims to provide clinicians with actionable insights to

optimize the safety and efficacy of immunotherapy while advancing

prognostic outcomes for ICI-related myocarditis.

Epidemiological features of ICI-related

myocarditis

The development of ICI-related myocarditis is

closely associated with immune hyperactivation and therapeutic

mechanisms, with combination therapies posing a particularly

elevated risk. Epidemiological data indicate that monotherapy with

ICIs results in myocarditis incidence rates of 0.5, 2.4 and 3.3%

for anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 inhibitors, respectively.

However, combining PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors increases the

incidence to 2.4% (11), with

mortality rising sharply from 36% (monotherapy) to 67% (7,12).

Chinese cohort studies report a domestic ICI-related myocarditis

incidence of 1.05–1.06%, consistent with global epidemiological

trends (13,14). Identified high-risk factors include

diabetes mellitus, heart failure, a history of acute coronary

syndrome and advanced age (>80 years) (11,15).

Although the overall incidence remains <2%, the high fatality

rate renders ICI-related myocarditis a critical clinical challenge

in cancer immunotherapy.

ICI-related myocarditis typically occurs within

weeks of initiation, with a median onset of 34 days (IQR: 21–75

days), with timing and risk varying by cancer type (7,11).

Patients with melanoma, especially those receiving anti-PD-1/CTLA-4

combination therapy, predominantly develop early-onset myocarditis

(≤2 weeks) (11). Conversely,

patients with thymic epithelial tumors (TETs) more frequently

experience delayed-onset myocarditis (≥6 weeks), likely due to

thymic dysfunction and impaired central immune tolerance

predisposing to T cell-mediated autoimmunity (16). Patients with TETs also demonstrate

a higher incidence of severe irAEs, contributing to their high

myocarditis risk (17). Beyond

tumor-specific factors, host characteristics also modulate risk,

including advanced age (>64 years), elevated body mass index

(>28 kg/m2) and prior cardiovascular medication use

(15,18). These findings underscore the need

for tailored surveillance strategies integrating both

patient-specific and cancer-specific factors to enable early

detection and timely intervention.

Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and

differential diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis

Clinical manifestations

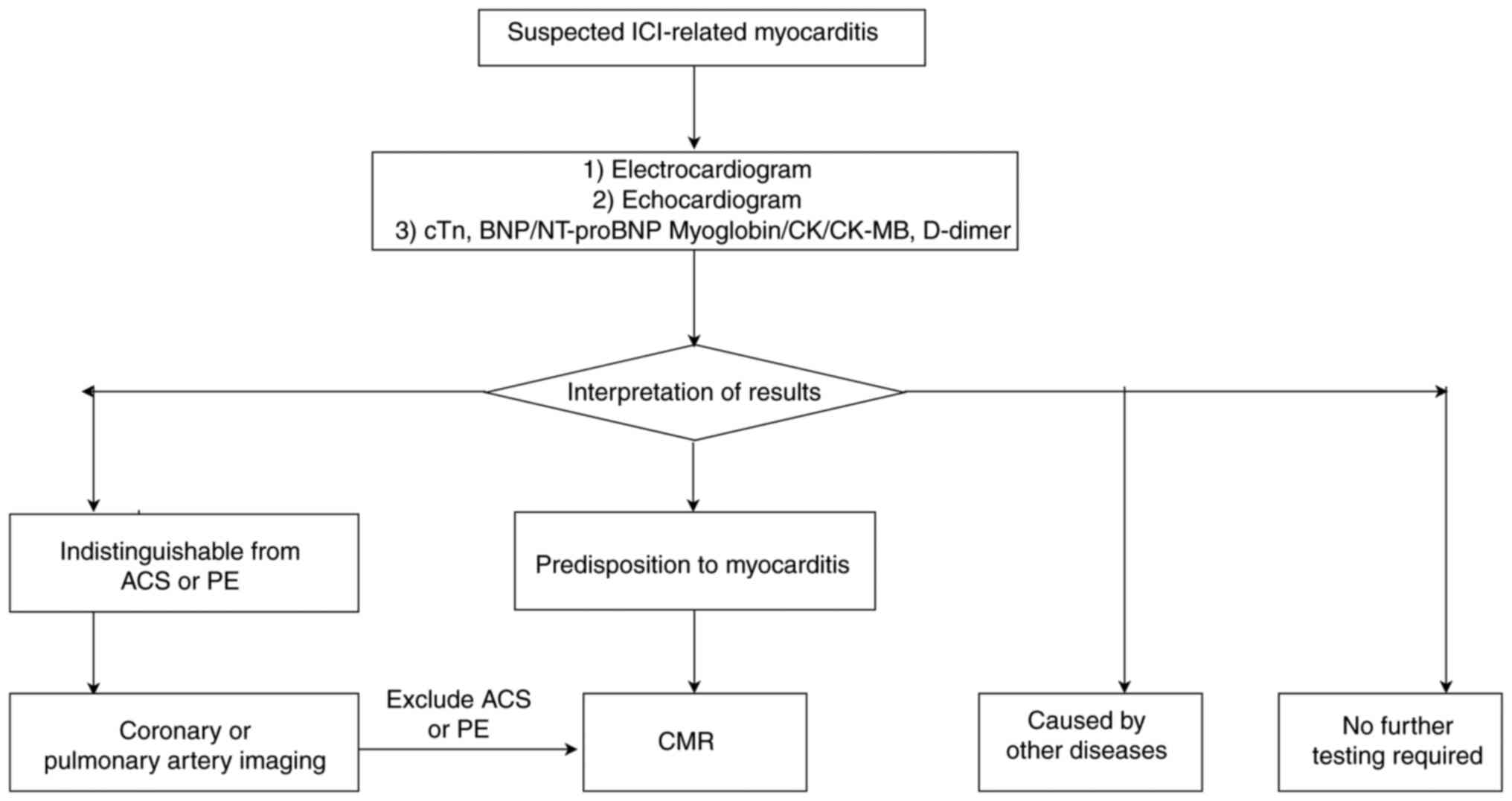

The diagnosis of ICI-related myocarditis requires

the integration of clinical manifestations, laboratory markers,

electrocardiogram findings and imaging features. Patients typically

present with chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations and fatigue. In

severe cases, the condition may progress to heart failure,

cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest (19). Physical examination may reveal

hypotension, tachyarrhythmias, jugular vein distension or other

signs (cold, clammy skin, prolonged capillary refill and oliguria)

of hemodynamic compromise (9,19,20)

(Fig. 1).

Diagnosis

Laboratory and imaging profiles in ICI-related

myocarditis

The laboratory profile of ICI-related myocarditis is

typically characterized by elevated myocardial injury and cardiac

stress biomarkers. Multiple studies have demonstrated abnormal

elevation of cardiac troponin (cTn)T and cTnI in 46–94% of cases

(21,22). This also discovered a critical

threshold of cTnT ≥32 times the upper reference limit, which was

significantly associated with adverse myocardial toxicity events

(high-risk cohort), whereas levels below this threshold indicated a

better prognosis (low-risk group). However, it was revealed that

some patients may present without cTnI or creatine kinase (CK)

elevation (22). The prevalence of

elevated natriuretic peptides [B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and

N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP)] exhibits interstudy variability: A

large-scale study reported NT-proBNP elevation in 77.5% (n=185) of

cases (23), contrasting with 100%

positivity in a 14-patient cohort (22), suggesting that sensitivity may be

sample size-dependent. While myoglobin, CK-MB, aspartate

aminotransferase and lactate dehydrogenase often show nonspecific

elevation (24,25), cTns demonstrate superior

specificity over natriuretic peptides, which may be confounded by

non-inflammatory left ventricular dysfunction or acute cardiac

stress. This may lead to increased wall tension and neurohormonal

activation, elevating BNP/NT-proBNP levels even in the absence of

myocardial inflammation (23,26).

Although individual biomarkers lack diagnostic specificity, their

combined interpretation provides critical value in the evaluation

of ICI-related myocarditis.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities are essential

diagnostic elements, detecting atrial fibrillation, ventricular

arrhythmias and conduction disturbances. Inflammatory involvement

of the cardiac conduction system may manifest as intraventricular

conduction delay, PR prolongation or complete heart block (27). Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR)

notably enhances diagnostic accuracy through structural and

functional assessment, with particular sensitivity in quantifying

myocardial involvement (28).

Prospective studies have validated the T1 mapping technology of CMR

as achieving 92% sensitivity for myocardial edema detection via

extracellular volume and T1 value quantification, enabling early

identification of myocarditis (28,29).

Existing diagnostic criteria and

procedures

Diagnostic confirmation of ICI-related myocarditis

requires multimodal integration of clinical presentation, biomarker

profiles and imaging findings. Current international consensus

advocates the Bonaca diagnostic framework comprising four pillars

(30): i) Characteristic symptoms

(including chest pain and heart failure); ii) ECG abnormalities

(ST-T changes and conduction blocks); iii) elevated myocardial

injury markers (cTnT ≥14 ng/l or CK-MB ≥5 µg/l); iv) CMR hallmarks

(T2-weighted edema and late gadolinium enhancement). Salem et

al (31) refined this protocol

through a multidisciplinary team (MDT) model: Primary screening via

ECG with high-sensitivity cTn, followed by CMR evaluation for

suspected cases, culminating in MDT interpretation. While

endomyocardial biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard, its

invasive nature and sampling variability restrict application to

diagnostically ambiguous cases (20).

Differential diagnosis

Core challenges in differential diagnosis

In clinical practice, establishing differential

diagnosis for ICI-related myocarditis presents multifaceted

challenges. First, the clinical manifestations demonstrate marked

heterogeneity and nonspecificity, ranging from asymptomatic

troponin elevation to fulminant heart failure or life-threatening

arrhythmia. These presentations show substantial overlap with viral

myocarditis and ischemic myocardial injury, while requiring

differentiation from irAEs, particularly neuromuscular

complications such as myositis and myasthenia gravis (32). Second, the coexistence of

preexisting cardiovascular comorbidities and treatment-related

complications in patients with cancer adds to the diagnostic

complexity (33).

Laboratory assessments are confounded by limited

specificity of conventional biomarkers (such as cTnT and CK), since

nonspecific factors including skeletal muscle injury and systemic

infections may alter their values. Furthermore, imaging modalities

currently lack sufficient discriminatory power to reliably

distinguish ICI-related myocarditis from other myocardial

pathologies (34,35). Collectively, these diagnostic

ambiguities underscore the critical need for developing novel

biomarker panels and advanced imaging techniques to improve

diagnostic precision.

Need for novel diagnostic tools and

technologies

Given the limitations of current diagnostic

methodologies, emerging technologies have expanded possibilities to

address these challenges. Liquid biopsy demonstrates distinct

advantages in early detection and disease stratification through

the capture of circulating biomarkers, including circulating tumor

cells and exosomes. These circulating components exhibit tissue

specificity while dynamically reflecting alterations in the cardiac

immune microenvironment, thereby providing molecular evidence for

differential diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring (36).

In artificial intelligence applications, machine

learning-based risk prediction models integrating clinical

characteristics, laboratory parameters and imaging biomarkers can

effectively identify populations at high risk of adverse cardiac

events. These models demonstrate superior predictive performance

compared with conventional scoring systems, offering clinicians a

robust foundation for early intervention strategies (37).

The synergistic application of multi-omics

technologies (including genomics, proteomics and metabolomics) has

further advanced the diagnostic paradigm for ICI-related

myocarditis. Single-cell sequencing of epicardial adipose tissue

has revealed that a CD8+ T cell to regulatory T cell

(Treg) ratio exceeding 2.5 serves as an early indicator of severe

myocarditis, enabling precision-guided immunosuppressive therapy

(38).

Mechanism

Physiological functions of immune

checkpoints and myocardial protection

PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway

Immune checkpoints serve key roles in maintaining

immune homeostasis and regulating immune responses. Key

immunosuppressive receptors, including CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1 and

LAG-3, prevent immune system overactivation by modulating T-cell

activation thresholds (39). The

PD-1/PD-L1 axis exerts immunoregulatory functions through

ligand-receptor interactions. As a CD28 superfamily member, PD-1 is

ubiquitously expressed on activated T cells, B lymphocytes,

monocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and dendritic cells (DCs).

Upon PD-L1 engagement, PD-1 recruits phosphatases SHP-1/2 to

inhibit T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling, thereby maintaining

peripheral immune tolerance (40).

Constitutive PD-L1 expression on cardiomyocytes and endothelial

cells provides local protection against autoimmune damage by

simultaneously suppressing regional T-cell responses (41).

ICIs restore T cell-mediated antitumor activity

through blockade of these inhibitory signals, potentially

disrupting immune equilibrium. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 monoclonal

antibodies competitively inhibit PD-1/PD-L1 interactions, reversing

T-cell functional suppression and activating downstream signaling

pathways (such as PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK) to amplify immune

responses (42,43). This mechanistic foundation has

enabled PD-1 inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, to achieve

therapeutic breakthroughs across multiple solid malignancies,

including tumors with specific genomic profiles (such as non-small

cell lung cancer or black chromocele) (44).

However, immune checkpoint blockade may reduce

T-cell activation thresholds, permitting aberrant activation of

autoreactive T cells that mount immune attacks against cardiac

tissue, a central pathogenic mechanism underlying ICI-related

myocarditis (45). The dual nature

of therapeutic benefits and risks emphasizes the critical need for

deeper understanding of immune checkpoint physiology and pathology

(Fig. 2).

Immunoregulatory function of

CTLA-4

CTLA-4, as a key immune checkpoint molecule, serves

a critical role early in T-cell activation by competitively binding

to CD80/CD86 molecules on the surface of antigen-presenting cells

(APCs), antagonizing the CD28 co-stimulatory signal, and thus

inhibiting T-cell proliferation and activation to maintain immune

homeostasis (46,47) (Fig.

2).

The cardioprotective role of CTLA-4 is particularly

notable: CTLA-4-deficient murine models develop lethal myocarditis

and pancreatitis, demonstrating its essential function in cardiac

autoimmunity (48). A previous

investigative study from Harbin Medical University revealed that

CTLA-4 m2a antibodies exacerbate myocardial damage in experimental

autoimmune myocarditis through CCL5+ neutrophil subset

infiltration, establishing a theoretical framework for

preventing/treating CTLA-4-associated myocarditis (49). Concurrently, anti-CTLA-4 antibodies

activate T helper (Th)17 cells and aggravate pressure

overload-induced heart failure, elucidating the immunological

pathway through which CTLA-4 signaling dysregulation precipitates

cardiac injury (50). In addition,

CTLA-4 has a central role in Treg-mediated immune suppression by

regulating cytokine secretion (such as by inhibiting the production

of IFN-γ), T-cell differentiation and proliferation, and

contact-dependent signaling between cells, thereby balancing the

intensity of the adaptive immune response (51).

In oncological therapeutics, anti-CTLA-4 antibodies

enhance T-cell activation via ligand binding blockade, thereby

exerting antitumor effects (52).

However, CTLA-4 inhibitors may induce cardiotoxicity, including

de novo onset or exacerbation of heart failure. These

findings underscore the necessity for systematic evaluation of the

dynamic equilibrium between immune activation and cardiac function

during treatment, mandating rigorous assessment of potential

cardiovascular risks

Co-inhibitory role of LAG-3

LAG-3, a type I transmembrane protein predominantly

expressed on Tregs and exhausted T cells, exerts immunosuppressive

effects on the tumor microenvironment through binding to MHC class

II molecules on APCs, thereby inhibiting T-cell activation and

proliferation (53).

Mechanistically, LAG-3 demonstrates synergistic inhibitory effects

with PD-1 in CD8+ T cells. Their co-expression

potentiates T-cell exhaustion and suppresses IFN-γ-mediated

antitumor immunity (54). This

functional interplay has been substantiated in murine models of

melanoma, where PD-1/LAG-3 double-deficient CD8+ T cells

have been reported to exhibit enhanced tumor clearance and

survival, while dual-knockout mice developed spontaneous T

cell-mediated myocarditis, confirming their joint role in

maintaining immune homeostasis and restraining autoimmune responses

(Fig. 2) (55).

The clinical translation of this synergistic

mechanism has yielded notable breakthroughs. Combination therapy

employing anti-LAG-3 (such as relatlimab) and anti-PD-1 (for

example, nivolumab) antibodies enhances T cell-mediated tumor

cytotoxicity and promotes effector cytokine secretion, including

TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-2 (56). The

landmark RELATIVITY-047 phase III trial demonstrated superior

clinical outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma receiving

combination therapy vs. monotherapy, leading to its US FDA approval

in 2022 (marketed as Opdualag) (57). This therapeutic milestone

underscores the pivotal role of co-inhibitory receptor networks in

advancing cancer immunotherapy paradigms.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of

ICI-related myocarditis

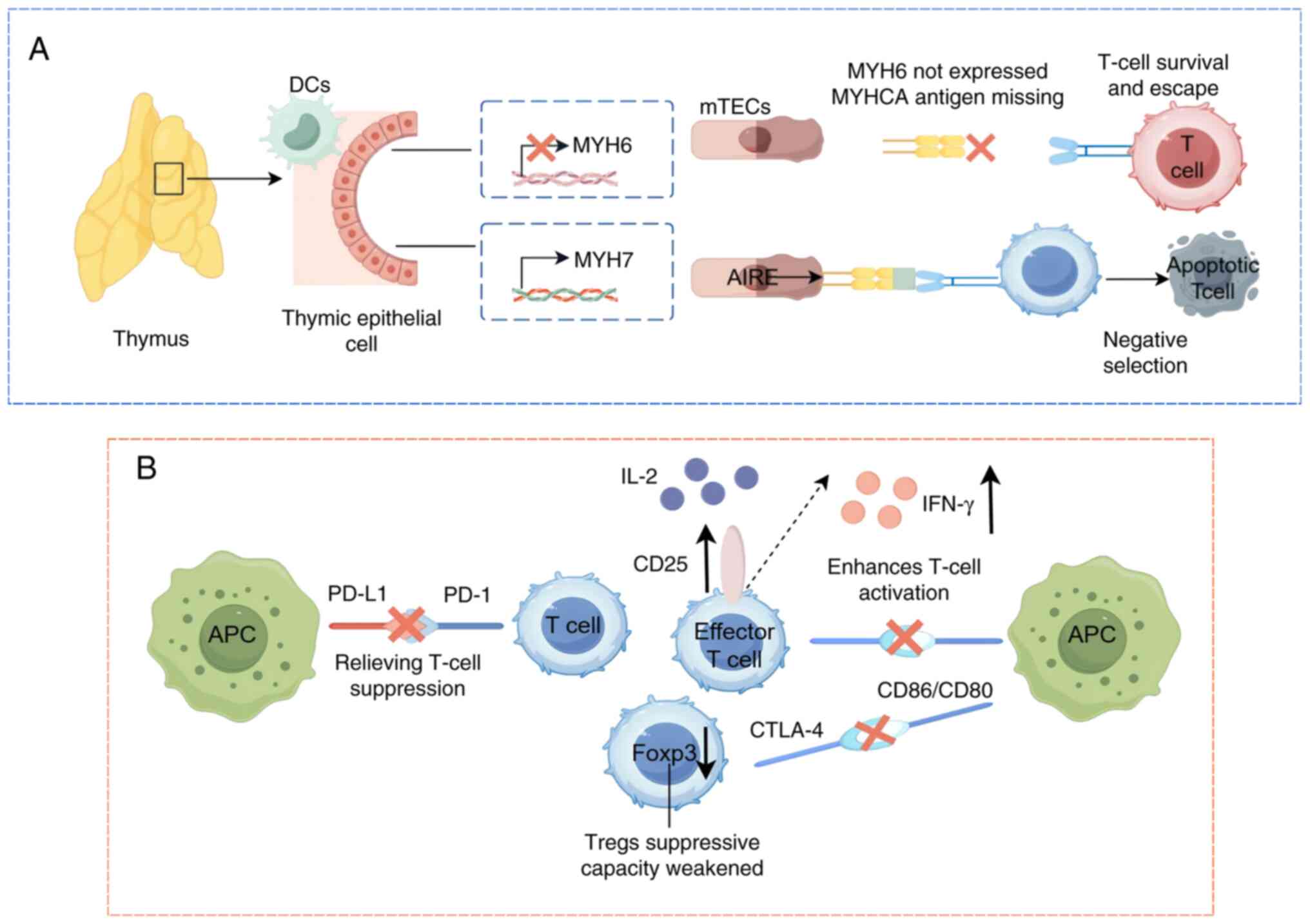

To maintain immune homeostasis, the immune system

must accurately distinguish between self and non-self antigens

during the process of eliminating pathogens and malignant cells.

This immunological balance is essential for mounting effective

immune responses while simultaneously preventing autoimmunity. To

achieve this, the host relies on two complementary tolerance

mechanisms-central tolerance and peripheral tolerance. Disruption

of these mechanisms, particularly through immune checkpoint

inhibition, may lead to loss of self-tolerance and the development

of immune-related adverse events, such as immune checkpoint

inhibitor-related myocarditis (58).

Central tolerance primarily involves thymic negative

selection, where self-reactive T lymphocytes are eliminated during

development. Peripheral tolerance encompasses multifaceted

regulatory processes: i) Functional suppression by Tregs and ii)

dynamic modulation of T-cell activation thresholds through immune

checkpoint signaling. These mechanisms collectively establish

immunological safeguards, including the maintenance of immune

privileged sites that protect vital organs from autoimmune

attack.

The synergistic operation of central and peripheral

tolerance systems enables accurate identification of pathogenic

threats while preserving tissue integrity. Disruption of this

equilibrium underlies the pathogenesis of ICI-related myocarditis,

where checkpoint inhibition may override protective mechanisms,

leading to aberrant immune targeting of cardiac tissue (59).

Destruction of immune tolerance

mechanisms

Defects in central tolerance

Central tolerance establishment relies on a biphasic

thymic selection process encompassing positive and negative

selection (60). During positive

selection, immature T-cell survival is determined by

moderate-affinity interactions between TCRs and self-peptide-MHC

complexes presented by thymic epithelial cells. T cells exhibiting

optimal affinity thresholds differentiate into CD4+

helper or CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lineages, whereas those

with insufficient affinity undergo apoptosis due to failed survival

signaling (61). Negative

selection subsequently eliminates high-affinity autoreactive T

cells through self-antigen presentation by medullary thymic

epithelial cells (mTECs) and DCs (62). This dual filtration mechanism

ensures exclusive export of foreign antigen-responsive mature T

cells to secondary lymphoid organs, thereby maintaining

immunological homeostasis. However, this system demonstrates

critical deficiencies in purging tissue-specific antigens,

particularly evident in cardiac autoimmunity.

The inefficacy of negative selection represents a

key limitation in central tolerance. Thymic deletion fails to

eliminate T cells targeting myosin heavy chain-α (MYHCA), a

cardiac-specific protein encoded by the MYH6 gene and predominantly

expressed in the atrioventricular myocardium (63,64).

This defect arises from the absence of MYH6 expression in the

thymus. While mTECs mediate negative selection by regulating

ectopic tissue antigen expression via the autoimmune regulator

(63), impaired MYH6 transcription

in mTECs allows MYHCA-reactive T cells to evade thymic deletion

during development (65). These T

cells therefore escape to peripheral tissues, where they may be

activated under specific conditions, potentially triggering an

autoimmune response. As a result, central tolerance is not entirely

effective and relies on other mechanisms, such as peripheral

tolerance, to compensate for its deficiencies, thus maintaining

immune system homeostasis and preventing the onset of autoimmune

diseases (Fig. 3A).

Disruption of peripheral

tolerance

Peripheral tolerance maintains immune homeostasis by

regulating the function of mature T cells. Its core mechanisms

include the immunosuppressive function of Tregs and immune

checkpoint signaling regulation. Tregs, as a subset of

CD4+ T cells (accounting for 5–7%) (66), suppress the function of effector T

cells through various mechanisms, including: Sequestration of the

pro-survival signal molecule IL-2, secretion of anti-inflammatory

cytokines such as TGFβ, IL-10 and IL-35, direct lysis of APCs and

effector T cells, mediating trogocytosis and inducing the

generation of other immunosuppressive T cell subsets within the

local microenvironment (67).

Additionally, insufficient co-stimulatory signals during T-cell

activation (such as low expression of CD80/CD86 on APCs) can lead

to T-cell anergy or apoptosis, which is further suppressed by Tregs

(68).

The immune checkpoint mechanism in peripheral

tolerance mainly involves co-inhibitory receptors on the surface of

T cells, such as CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1 and LAG-3 (69). CTLA-4 inhibits co-stimulatory

signals by competitively binding to CD80/CD86, serving a negative

regulatory role in the early stages of T-cell activation (4). PD-1 antagonizes the TCR/CD28

signaling pathway by recruiting tyrosine phosphatases, inhibiting

the activation of effector T cells (70,71).

In addition, CTLA-4 and PD-1 can enhance the immunosuppressive

function of Tregs (72). LAG-3

interferes with the interaction between T cells and APCs by binding

to MHC class II molecules (73).

These molecules together constitute a dynamic regulatory network of

peripheral tolerance.

The core mechanism by which ICIs induce cardiac

autoimmunity lies in the dual disruption of peripheral tolerance.

On one hand, ICIs block the CTLA-4 or PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis,

thereby relieving physiological suppression of effector T cells.

This leads to their overactivation and subsequent attack on

myocardial tissue (74).

Experimental evidence has demonstrated that in PD-L1-deficient

murine models of myocarditis, the inflammatory response is

exacerbated, confirming the direct protective role of PD-1/PD-L1 in

maintaining cardiac immune homeostasis (75). On the other hand, ICIs impair Treg

function. For example, CTLA-4 deficiency induces fatal

lymphoproliferative disorders, and anti-CTLA-4 therapy not only

diminishes Treg-mediated suppression but also dysregulates PD-1

signaling, resulting in compounded tolerance defects (76). Additionally, ICI therapy disrupts

endogenous cardiac protective mechanisms (such as myocardial PD-L1

expression), which potentiates CD8+ T cell cytotoxicity

against cardiac tissue (77).

Concurrently, LAG-3 inhibition exacerbates inflammatory

cardiomyopathy (78). The systemic

collapse of peripheral tolerance networks ultimately culminates in

cardiac-specific autoimmune pathology (Fig. 3B).

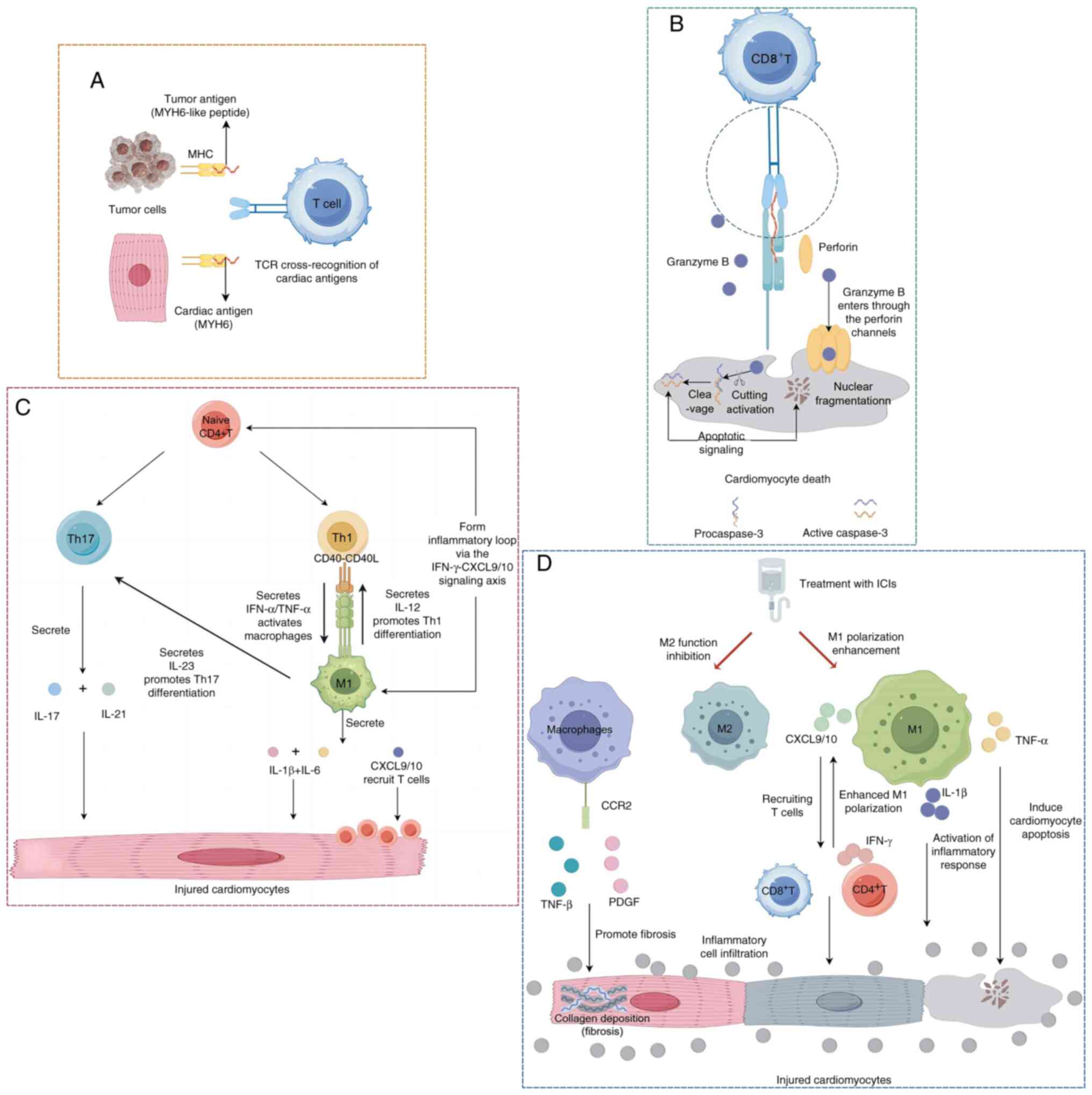

Cross-reactivity of cardiac

antigens

The pathogenesis of ICI-related myocarditis may

predominantly involve tumor-cardiac cross-antigen reactivity.

Substantial evidence has indicated that tumor antigens (such as

MYH6) share homologous epitopes with myocardial structural proteins

(including troponin), which can activate cross-reactive T cells

capable of simultaneously targeting both neoplastic and cardiac

tissues (79). Experimental

validation using immunocompetent A/J murine models has demonstrated

that repeated administration of anti-PD-1 antibodies induces

myocarditis, with myocardial infiltration of α-myosin-specific

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells identified through TCR

analysis. Notably, these cross-reactive T-cell populations have

also been detected in the peripheral blood, spleen, mediastinal

lymph nodes and cardiac tissues of healthy control mice, suggesting

pre-existing autoreactive lymphocytes that become pathogenic upon

immune checkpoint inhibition (80). Johnson et al (81) revealed that TCR-β clonotypic

sequences were highly overlapped between the myocardium, tumors and

skeletal muscles of patients with myocarditis, indicating that

cross-reactive T cells can mediate multi-organ damage. Clinically,

the frequent co-occurrence of myositis or myasthenia gravis in

patients with ICI-related myocarditis aligns with the shared

antigenic epitope theory. Particularly, MYHC antigens expressed in

both cardiac and skeletal muscles may serve as critical targets for

these cross-reactive immune responses (82). Collectively, these findings

establish that cross-antigen-driven immune mechanisms underlie the

simultaneous multi-organ damage observed in this clinical syndrome

(Fig. 4A).

Cellular and molecular mechanisms

T cell-mediated direct injury

T cells serve as central effector cells in

ICI-related myocarditis. These cells recognize cardiac antigens and

directly attack cardiomyocytes, resulting in tissue damage

(83,84). This process is initiated by the

binding of TCRs to MHC-antigen complexes presented on the surface

of cardiomyocytes, thereby triggering cytotoxic responses.

Role of CD8+ T cells

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes serve a

pivotal role in immune-mediated myocarditis. They induce

cardiomyocyte death through the release of perforin and granzyme B.

Perforin facilitates transmembrane pore formation, enabling

granzyme B influx and subsequent activation of the

caspase-dependent apoptotic cascade, ultimately leading to

cardiomyocyte death (85–87). Pathological analyses of myocardial

biopsies have revealed notable CD8+ T-cell infiltration

in focal necrotic regions, with infiltration levels positively

associated with the degree of T-cell clonal expansion (79). Mechanistically, CD8+ T

cells interact with cardiomyocytes via MHC class I molecules and

release cytotoxic mediators; especially when receiving anti-CTLA-4

combined with anti-PD-1 treatment, T-cell activation and

proliferation are enhanced, further aggravating myocardial damage

(88). Animal models have

demonstrated that CD8+ T-cell depletion markedly

attenuates myocardial inflammation and fibrosis (77). In addition, peripheral blood

analyses of patients with ICI-related myocarditis have detected

clonally expanded activated cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell

subsets. A prominent increase is observed in terminally

differentiated effector memory CD8+ T cells, whereas

naïve T cells, central memory T cells and other effector memory

subsets remain unaltered (89).

This distinct immunophenotypic shift underscores the critical

involvement of CD8+ T cells in the pathogenesis of

ICI-related myocarditis, with their activation status closely

associated with disease severity (Fig.

4B).

Role of CD4+ T cells

CD4+ T cells drive the inflammatory

cascade through cytokine networks in ICI-related myocarditis.

Although the number of infiltrating myocardial CD4+ T

cells is limited, the pro-inflammatory cytokines they secrete, such

as IFN-γ and TNF-α, synergistically promote the recruitment and

activation of monocytes/macrophages while directly activating

apoptotic pathways in myocardial cells, thereby exacerbating tissue

damage (90). Clinical evidence

has demonstrated a significant positive association between the

density of myocardial CD4+ T-cell infiltration and the

severity of the inflammatory response, indicating that their

regulatory activity is closely associated with the degree of

disease progression. In a

Ctla-4+/−Pdcd1−/−mouse model, CD4+

T cells and macrophages form a self-amplifying inflammatory loop

via the IFN-γ-CXCL9/10 signaling axis, leading to persistent

deterioration of the inflammatory microenvironment (91). Furthermore, within the inflammatory

milieu, cytokines drive the differentiation of CD4+ T

cells into Th1/Th17 subsets. These subsets recruit neutrophils and

activate cytotoxic T cells, thereby contributing to

multidimensional mechanisms of myocardial injury (65) (Fig.

4C).

T-cell hyperactivation and autoimmune

reactivity

The CTLA-4 protein exhibits superior binding

affinity for B7 molecules (CD80/CD86) on APCs compared with CD28.

This competitive interaction suppresses CD28-mediated T-cell

activation signals, serving as a critical negative regulatory

mechanism (52). Anti-CTLA-4

antibodies (such as ipilimumab) disrupt CTLA-4/B7 binding, thereby

restoring CD28 co-stimulatory signals and promoting T-cell

proliferation, differentiation and cytokine production. The

PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, on the other hand, inhibits T-cell function

through phosphorylation of the intracellular immune receptor

tyrosine-based inhibitory motif, which recruits phosphatases such

as SHP-2 to antagonize TCR and CD28 downstream signaling (40). PD-1 inhibitors (such as nivolumab

and pembrolizumab) block ligand binding, consequently alleviating

T-cell activity suppression and inducing aberrant activation of

effector T cells (42,43). Histopathological studies have

demonstrated T-cell infiltration within the myocardial tissues of

patients of ICI-related myocarditis, with clonal T cell populations

showing homology to tumor-infiltrating effector T cells (35,92).

Clinical evidence indicates that ICI-induced T-cell clonal

expansion drives myocardial tissue targeting, ultimately

precipitating myocarditis (81).

Mechanistically, ICIs interfere with signaling pathways such as

CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1, lowering the T-cell activation threshold and

disrupting peripheral immune tolerance, which leads to abnormal

T-cell activation and inappropriate immune attacks on myocardial

tissue.

Macrophages and inflammatory

amplification

Infiltration and pro-inflammatory mediator

release

The pathogenesis of ICI-related myocarditis is

characterized by prominent macrophage infiltration, as evidenced by

histopathological analyses (93).

Clinical investigations have demonstrated substantial

co-infiltration of CD68+ macrophages with

CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocytes within myocardial

tissues, suggesting their synergistic role in propagating

inflammatory responses (94).

Activated M1-type macrophages further amplify the inflammatory

response by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β and

IL-6) and chemokines (CXCL9 and CXCL10), which recruit T cells and

other immune cells to infiltrate the myocardial tissue, thereby

forming an inflammatory cascade amplification (77). Experimental models utilizing

CTLA-4/PD-1-deficient mice recapitulate these findings, showing

concurrent infiltration of CD68+ macrophages and T cells

in myocardial lesions. These macrophages exacerbate tissue damage

through sustained release of IL-1β and other inflammatory mediators

(95). Compared with other types

of myocarditis (such as dilated or lymphocytic myocarditis), the

myocardial tissue of patients with ICI-related myocarditis shows a

notable enrichment of CXCL9+/CXCL10+

macrophage populations (92).

Antigen presentation and T-cell

interactions

Macrophages simultaneously have antigen-presenting

function in ICI-related myocarditis. They potentially present

cardiac autoantigens (such as α-myosin) via MHC molecules,

consequently activating autoreactive T cells and establishing a

pathogenic positive feedback loop (96). Experimental models have

demonstrated that monocyte-derived CCR2+ macrophages

within cardiac tissue secrete CXCL9/CXCL10. These chemokines engage

CXCR3 receptors on T cells, driving T-cell activation and

sustaining a pro-inflammatory microenvironment (91). Furthermore, IFN-γ secreted by

activated T cells induces macrophage activation of the JAK/STAT

signaling pathway. This reciprocal interaction forms a

bidirectional regulatory network that amplifies inflammatory

responses (97). These experiments

collectively suggest that macrophages and T cells interact and

jointly promote the inflammatory response.

Macrophage phenotypic plasticity

Under physiological conditions, M2 macrophages

facilitate tissue repair through apoptotic cell clearance and

secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-10) (98). In ICI-related myocarditis, however,

this homeostatic balance shifts toward dominance of the

pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype (99). Animal model studies have shown that

inhibiting macrophage chemotaxis (such as by blocking MCP-1

signaling) or targeting the IFN-γ pathway can reduce the

infiltration of pro-inflammatory macrophages and improve myocardial

damage (90,100). Single-cell sequencing has further

revealed the heterogeneity of macrophage subsets and reported that

the CCR2+ subset exacerbates pathological myocardial

remodeling by activating pro-fibrotic pathways (such as TGF-β

signaling), providing a theoretical basis for its potential as a

therapeutic target (101). In

summary, macrophages in ICI-related myocarditis act both as

inflammatory effector cells and as key nodes in immune regulation.

Future research should further explore the specific functions of

these subsets and the mechanisms of phenotypic conversion to

provide a theoretical basis for immune interventions (Fig. 4D).

Other immune cells

Role of B cells

Current evidence does not establish a direct

pathogenic role of B cells in ICI-related myocarditis. While murine

models demonstrate detectable IgG-secreting plasma cells and

anti-myosin autoantibodies, these antibodies likely represent

secondary responses to antigen exposure following cardiomyocyte

necrosis, given the rare observation of B-cell infiltration in

clinical myocardial biopsies (102). Nevertheless, extrapolating from

B-cell functions in other subtypes of myocarditis and immune

checkpoint regulation of B-cell activity, it may be proposed that B

cells could contribute indirectly through antibody-mediated

immunity or T-cell collaboration. Studies have shown that in

PD-1-deficient mice, there is overactivation of B cells and

hypergammaglobulinemia, while PD-1 helps maintain immune

homeostasis by inhibiting B-cell proliferation and the secretion of

pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 (103,104). These findings suggest that this

indirect regulatory mechanism may explain some of the clinical

manifestations of humoral immune abnormalities in patients with

ICI-related myocarditis.

Role of NK cells

The pathological role of NK cells in ICI-related

myocarditis remains incompletely defined. Studies have indicated

that NK cells express immune checkpoint molecules, including PD-1

and CTLA-4, and their cytotoxic activity may be modulated by

checkpoint signaling pathways. Prolonged antigenic stimulation can

upregulate PD-1 expression on NK cells, leading to impaired

cytotoxic function (105,106). Consequently, ICI therapy may

reverse this inhibitory state, potentiating NK cell cytotoxicity

and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IFN-γ,

thereby contributing to the pathogenesis of myocarditis (107). Nevertheless, existing evidence

has not confirmed direct infiltration of NK cells into myocardial

tissue or their role in mediating cardiomyocyte injury.

Genetic and microenvironmental

determinants

Genetic predisposition

The HLA-DQ8 allele, encoding a specific MHC class II

heterodimer, exhibits strong associations with autoimmune

pathologies including type 1 diabetes mellitus and celiac disease.

Its molecular structure markedly increases the risk of ICI-related

myocarditis in carriers by enhancing autoantigen presentation and

T-cell activation (108). This

histocompatibility complex potentiates autoimmune responses through

structural facilitation of self-antigen presentation and subsequent

CD4+ T-cell activation, conferring elevated risk for

ICI-related myocarditis in genetically predisposed individuals

(109). Mechanistic validation

comes from murine models engineered with humanized HLA-DQ8

expression on an MHC class II-deficient background. These

preclinical models develop severe concurrent myocarditis and

myositis following anti-PD-1 therapy, recapitulating the human

disease phenotype (110). This

evidence suggests that specific genetic backgrounds, such as

HLA-DQ8, may significantly increase the susceptibility to

ICI-related myocarditis (111).

Thymic dysfunction

Patients with TETs exhibit a markedly elevated

incidence of myocarditis following ICI therapy. These individuals

frequently develop severe arrhythmia and myositis, complications

that may progress to respiratory failure or fatal outcomes

(111–113). The elevated levels of serum

anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies in this population suggest

that thymus-related autoimmune disorders are one of the causes of

the disease (114).

Mechanistically, the thymus regulates T-cell

development and central tolerance via CTLA-4 and PD-1 signaling. In

patients with TETs, thymic structural disruption creates dual

pathological consequences: i) Absence of cardiac-specific antigens

(such as MYHCA) in the thymic medulla permits autoreactive T cells

to evade negative selection (16);

ii) the tumor microenvironment may induce the formation of T-cell

subsets with potential self-targeting tendencies. After ICI

treatment relieves immune inhibitory signals, these T-cell subsets

become activated and breach immune tolerance, leading to an attack

on cardiac tissue (115). This

thymic dysfunction, in combination with the effects of ICI therapy,

ultimately results in a markedly increased risk of developing

myocarditis.

Gut microbiome

The molecular mimicry between peptides derived from

gut commensal microbiota and cardiac myosin (such as MYH6) may

activate cardiac-specific Th17 cells, thereby triggering autoimmune

responses against myocardial tissue. Studies have suggested that

such cross-reactive peptides drive ICI-related myocarditis by

promoting Th17 cell activation and cross-recognition of

tumor/microbial antigens. Furthermore, variations in gut microbiota

composition among patients may modulate these immune responses,

thereby influencing disease susceptibility (89,116).

Other aspects

Myocardial electrophysiology and conduction

system injury

ICI-related cardiac electrophysiological

abnormalities can induce arrhythmias through multiple pathways.

Primarily mediated by inflammatory responses (myocarditis), these

abnormalities trigger myocardial fibrosis and localized scar

formation. Such anatomical remodeling establishes a pathological

substrate for reentrant arrhythmias (such as atrial fibrillation

and ventricular fibrillation) through the creation of ectopic

electrical foci or conduction block zones (117,118). The electrophysiological

regulation of the cardiac conduction system is intrinsically linked

to macrophage functionality through electrical coupling mediated by

connexin 43 (Cx43) with cardiomyocytes (119). Hulsmans et al (119) demonstrated that

macrophage-specific Cx43 ablation causes atrioventricular

conduction delays, whereas CD11b deficiency induces progressive

atrioventricular blocks, implicating macrophage-dependent Cx43

signaling in both physiological conduction and arrhythmogenesis.

These synergistic mechanisms collectively amplify arrhythmia

susceptibility during ICI therapy.

Protective effects of estrogen

The sex disparity (the incidence or severity is

higher in women) observed in ICI-related myocarditis incidence may

be attributed to the estrogen-estrogen receptor (ER)

β-mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (MANF)

signaling axis. Mechanistic studies have demonstrated that estrogen

activates ERβ signaling, upregulating MANF. This neurotrophic

factor confers cardioprotection through two key mechanisms:

Suppressing myocardial T-cell infiltration and inhibiting

pro-inflammatory cytokine release (including IFN-γ and TNF-α)

(120,121).

Experimental data from female murine models have

revealed that ICI treatment induces 17-β-estradiol depletion,

concomitant with reduced cardiac MANF expression, which exacerbates

myocarditis progression. Pharmacological intervention with

exogenous estrogen or ERβ-selective agonists restores MANF levels,

markedly attenuating myocardial inflammation and fibrotic

remodeling (122). These findings

elucidate the molecular basis of estrogen-mediated protection and

provide a rationale for sex-specific therapeutic strategies in

ICI-associated cardiac toxicity.

Future directions

Biomarker development and diagnostic

technologies

Advancements have notably improved early diagnostic

strategies for ICI-related myocarditis. Myocardium-specific

autoantibodies (such as anti-myosin antibodies) and TCR repertoire

analysis have the potential for early diagnosis of ICI-related

myocarditis. Notably, T-cell infiltration and upregulation of PD-L1

expression has been detected in the myocardial tissue of patients

with ICI-related myocarditis, suggesting a T cell-mediated immune

injury mechanism (95).

Additionally, the combined detection of myocardial-specific

microRNAs (miRs), such as miR-208a, and cTnI enhances diagnostic

sensitivity, as miR-208a is released earlier than cTnI alone

(123). Furthermore, optimization

of imaging diagnostics and artificial intelligence-assisted systems

may address current diagnostic limitations (124). Future efforts should integrate

multi-omics biomarker datasets with dynamic monitoring platforms to

establish non-invasive, high-sensitivity diagnostic frameworks.

Innovative targeted therapeutic

strategies

The standard first-line treatment for ICI-related

myocarditis involves high-dose corticosteroids (such as

methylprednisolone, 1,000 mg/day for 3 days), followed by a

tapering regimen over several weeks. For steroid-refractory cases,

immunosuppressants such as abatacept, mycophenolate mofetil or

infliximab may be employed. Early treatment within 72 h is critical

for improved outcomes (125).

Advances in targeted therapeutic strategies for

ICI-related myocarditis have emerged as a critical research focus.

Current efforts have concentrated on three principal domains: i)

Immune checkpoint regulation: By antagonizing CTLA-4 or modulating

downstream PD-1 molecules (such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR), these strategies

aim to balance immune activation and myocardial protection

(126). ii) Cytokine-targeted

intervention: Implementation of IL-6 receptor antagonists

(tocilizumab) and TNF-α inhibitors may alleviate the onset of

inflammation. Clinical evidence has indicated that survival

outcomes are enhanced in critically ill patients when combined with

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support (127). iii) Development of specific

monoclonal antibodies: Antibody drugs targeting myocardial-specific

antigens, such as cTns, may reduce nonspecific attacks, although

this technology is still in the preclinical research phase

(89). Additionally, innovative

combination therapies have garnered attention. For example,

low-dose corticosteroids combined with JAK/STAT pathway inhibitors

(such as baricitinib) can synergistically suppress hyperactivated

immune responses while reducing the toxicity associated with

conventional treatments (128).

Nevertheless, current evidence remains predominantly derived from

limited clinical cohorts, underscoring the imperative for

large-scale randomized controlled trials to validate safety and

efficacy profiles. Future investigations should prioritize

multi-omics-driven target discovery and advanced drug delivery

platforms to optimize myocardial-specific immunomodulatory

precision.

Multidisciplinary collaboration

Rechallenge with ICIs after immune-related

myocarditis remains a controversial clinical issue. Rechallenge may

be considered under stringent conditions: Complete resolution of

myocarditis symptoms, normalization of troponin and NT-proBNP,

resolution of imaging findings and consensus by an MDT. Emerging

guidelines suggest cautious use and rechallenge is typically

avoided unless no alternatives exist (125).

The management of ICI-related myocarditis

necessitates MDT collaboration involving cardiology, oncology and

immunology to optimize early detection and personalized

interventions. Real-time coordination between oncologists and

cardiologists enables balanced therapeutic decision-making,

including ICI dose adjustments or co-administration of

immunomodulatory agents to mitigate cardiotoxicity without

compromising antitumor efficacy (Table

I) (129–131). In the future, standardized

collaborative processes need to be established to improve

prognosis.

| Table I.Graded treatment strategies for

ICI-related myocarditis. |

Table I.

Graded treatment strategies for

ICI-related myocarditis.

| Severity | First-line

treatment | Second-line

treatment | Monitoring and key

actions |

|---|

| Mild (Grade 1):

Suspected | 1) Hospitalization

for | If symptoms develop

or | Serial

monitoring: |

| or confirmed,

asymptomatic | monitoring. | biomarkers

worsen, | -Troponin |

| with cardiac

biomarker | 2) Initiation of

cortico- | escalation to

moderate/ | -ECG |

| elevation or ECG

changes | steroids:

Prednisone | severe treatment

protocol. | -Echocardiography

(LVEF) |

|

| 1-2 mg/kg/day

orally |

| Decision to resume

ICI is |

|

| (or

methylprednisolone |

| highly

individualized if |

|

| IV

equivalent). |

| symptoms resolve

and |

|

| 3) Discontinuation

of ICI therapy. |

| biomarkers

normalize. |

| Moderate to

severe | 1) Immediate

hospitali- | If no clinical

improvement | Intensive

monitoring: |

| (Grade 2–3): | zation (often to

cardiac | within 24–72 h of

high-dose | -Frequent troponin,

ECG |

| Significant

symptoms | unit). | steroids: |

-Echocardiography |

| (e.g., chest pain,

dyspnea), | 2) High-dose

cortico | -Add second-line

immuno- | -Assess for

multi-organ ir |

| biomarker

elevation, LVEF | steroids:

Methylpredni- | suppressants: | AEs (e.g.,

myositis, MG). |

| dysfunction or

arrhythmias | solone 1–2

mg/kg/day IV. | • Mycophenolate

mofetil | -Manage heart

failure/ |

|

| 3) Permanent

disconti- | • Antithymocyte

globulin | arrhythmias as

per |

|

| nuation of

ICI. | (ATG) | standard

guidelines. |

|

|

| • Abatacept

(especially for fulminant cases) |

|

|

|

| -CONTRAINDICATED:

Infliximab (associated with increased cardiovascular mortality and

heart failure). |

|

|

Life-threatening | 1) Admit to

ICU. | Initiate urgently

(concurrently | ICU-level

monitoring: |

| (Grade 4):

Hemodynamic | 2) Pulse-dose | or if no immediate

response): | -Hemodynamics

(e.g., |

| instability,

cardiogenic |

corticosteroids: | -Second-line

agents: ATG or | Swan-Ganz

catheter) |

| shock, lethal

arrhythmias |

Methylprednisolone | Abatacept. | -Continuous

telemetry |

|

| 1,000 mg/day

IV. | -Mechanical

circulatory | -Multi-organ

function |

|

| 3) Add IV

Immuno-globulin (IVIG). | support: Consider

VA-ECMO for cardiogenic shock. | support. |

|

| 4) Permanently

discontinue ICI. | -Temporary pacing

for high-grade heart block. |

|

|

|

| -Heart

failure/arrhythmia support. |

|

Conclusion

ICI-related myocarditis represents a critical

challenge in cancer immunotherapy. While ICIs have revolutionized

survival outcomes in malignancies, their cardiovascular toxicity

substantially limits their clinical utility. Current diagnostic

strategies integrating biomarker profiling, cardiac imaging and

histopathological confirmation remain constrained by delayed

detection and suboptimal specificity. Current research is focused

on three core issues: i) The pathophysiological mechanisms,

particularly the role of T-cell clonal expansion and the

cross-reactivity between myocardial antigen epitopes, which remain

to be fully elucidated; ii) the absence of validated predictive

biomarkers and risk stratification tools; iii) existing stratified

treatment strategies lack evidence-based support. Future research

is needed in the following areas: Firstly, systematic biology

methods should be employed to analyze dynamic changes in the immune

microenvironment, and single-cell sequencing techniques should be

used to reveal the clonotype characteristics of myocardium-specific

TCRs. Secondly, multi-omics predictive models integrating genomics,

proteomics and metabolomics should be developed. Additionally,

interdisciplinary research platforms spanning oncology, cardiology

and immunology should be established. Particular emphasis should be

placed on cohort studies and biobank development, as these will

provide crucial support for optimizing diagnostic and therapeutic

pathways. With the ongoing expansion of indications for

immunotherapy, further elucidating the molecular mechanisms of

ICI-related myocarditis and establishing prevention and treatment

strategies will become key directions for future research. Current

research must prioritize elucidating risk stratification mechanisms

to achieve a precise equilibrium between therapeutic efficacy and

cardiotoxicity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

LD was the primary contributor to the writing of

the manuscript. QX and YD proposed the topic, oversaw the

literature selection and synthesis, and critically revised the

manuscript for accuracy and clarity; these two authors contributed

equally to this article. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors read and approved the final manuscript, were responsible

for all aspects of the work and approved its submission.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liu X, Hogg GD and DeNardo DG: Rethinking

immune checkpoint blockade: ‘Beyond the T cell’. J Immunother

Cancer. 9:e0014602021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Blank C, Gajewski TF and Mackensen A:

Interaction of PD-L1 on tumor cells with PD-1 on tumor-specific T

cells as a mechanism of immune evasion: Implications for tumor

immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 54:307–314. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Naimi A, Mohammed RN, Raji A, Chupradit S,

Yumashev AV, Suksatan W, Shalaby MN, Thangavelu L, Kamrava S,

Shomali N, et al: Tumor immunotherapies by immune checkpoint

inhibitors (ICIs); the pros and cons. Cell Commun Signal.

20:442022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Korman AJ, Garrett-Thomson SC and Lonberg

N: The foundations of immune checkpoint blockade and the ipilimumab

approval decennial. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 21:509–528. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wei J, Li W, Zhang P, Guo F and Liu M:

Current trends in sensitizing immune checkpoint inhibitors for

cancer treatment. Mol Cancer. 23:2792024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Cone EB, Haeuser L and Reese SW: Immune

checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy is associated with less cardiac

toxicity than combination therapy. PLoS One. 17:e02720222022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Salem JE, Manouchehri A, Moey M,

Lebrun-Vignes B, Bastarache L, Pariente A, Gobert A, Spano JP,

Balko JM, Bonaca MP, et al: Cardiovascular toxicities associated

with immune checkpoint inhibitors: An observational, retrospective,

pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Oncol. 19:1579–1589. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gougis P, Jochum F, Abbar B, Dumas E,

Bihan K, Lebrun-Vignes B, Moslehi J, Spano J, Laas E, Hotton J, et

al: Clinical spectrum and evolution of immune-checkpoint inhibitors

toxicities over a decade-a worldwide perspective.

EClinicalMedicine. 70:1025362024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hu JR, Florido R, Lipson EJ, Naidoo J,

Ardehali R, Tocchetti CG, Lyon AR, Padera RF, Johnson DB and

Moslehi J: Cardiovascular toxicities associated with immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Cardiovasc Res. 115:854–868. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Yousif LI, Screever EM, Versluis D,

Aboumsallem JP, Nierkens S, Manintveld OC, de Boer RA and Meijers

WC: Risk factors for immune checkpoint inhibitor-mediated

cardiovascular toxicities. Curr Oncol Rep. 25:753–763. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Mahmood SS, Fradley MG, Cohen JV, Nohria

A, Reynolds KL, Heinzerling LM, Sullivan RJ, Damrongwatanasuk R,

Chen CL, Gupta D, et al: Myocarditis in patients treated with

immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 71:1755–1764.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Moslehi JJ, Salem JE, Sosman JA,

Lebrun-Vignes B and Johnson DB: Increased reporting of fatal immune

checkpoint Inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Lancet. 391:9332018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Wang F, Sun X, Qin S, Hua H, Liu X, Yang L

and Yang M: A retrospective study of immune checkpoint

inhibitor-associated myocarditis in a single center in China.

Cancer Commun. 9:162020.

|

|

14

|

Wang F, Qin S, Lou F, Chen FX, Shi M,

Liang X, Jiang H, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Du Y, et al: Retrospective

analysis of immune checkpoint Inhibitor-associated myocarditis from

12 cancer centers in China. J Clin Oncol. 38:e151302020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Oren O, Yang EH, Molina JR, Bailey KR,

Blumenthal RS and Kopecky SL: Cardiovascular health and outcomes in

cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors. Am J

Cardiol. 125:1920–1926. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Fenioux C, Abbar B, Boussouar S, Bretagne

M, Power JR, Moslehi JJ, Gougis P, Amelin D, Dechartres A, Lehmann

LH, et al: Thymus alterations and susceptibility to immune

checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis. Nat Med. 29:3100–3110. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Shelly S, Agmon-Levin N, Altman A and

Shoenfeld Y: Thymoma and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 8:199–202.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zamami Y, Niimura T, Okada N, Koyama T,

Fukushima K, Izawa-Ishizawa Y and Ishizawa K: Factors associated

with immune checkpoint inhibitor-related myocarditis. JAMA Oncol.

5:1635–1637. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Puzanov I, Subramanian P, Yatsynovich YV,

Jacobs DM, Chilbert MR, Sharma UC, Ito F, Feuerstein SG, Stefanovic

F, Hicar MD, et al: Clinical characteristics, time course,

treatment and outcomes of patients with immune checkpoint

inhibitor-associated myocarditis. J Immunother Cancer.

9:e0025532021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Bonaca MP, Olenchock BA, Salem JE, Wiviott

SD, Ederhy S, Cohen A, Stewart GC, Choueiri TK, Di Carli M,

Kumbhani DJ, et al: Myocarditis in the setting of cancer

therapeutics: Proposed case definitions for emerging clinical

syndromes in Cardio-oncology. Circulation. 140:80–91. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Lehmann LH, Heckmann MB, Bailly G, Finke

D, Procureur A, Power JR, Stein F, Bretagne M, Ederhy S, Moslehi J,

et al: Cardiomuscular biomarkers in the diagnosis and

prognostication of immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis.

Circulation. 148:473–486. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Barac A, Wadlow RC, Deeken JF and

deFilippi C: Cardiac troponin I and T in ICI myocarditis screening,

diagnosis, and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 6:804–807. 2024.

|

|

23

|

Zotova L: Immune checkpoint

Inhibitors-related myocarditis: A review of reported clinical

cases. Diagnostics. 13:12432023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Vasbinder A, Chen Y, Procureur A, Gradone

A, Azam TU, Perry D, Shadid H, Anderson E, Catalan T, Blakely P, et

al: Biomarker trends, incidence, and outcomes of immune checkpoint

Inhibitor-induced myocarditis. JACC CardioOncol. 4:689–700. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Caio G: Myocarditis with immune checkpoint

blockade. N Engl J Med. 376:291–292. 2017.

|

|

26

|

Semeraro GC, Cipolla CM and Cardinale DM:

Role of cardiac biomarkers in cancer patients. Cancers (Basel).

13:54262021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Song W, Zheng Y, Dong M, Zhong L, Bazoukis

G, Perone F, Li G, Ng CF, Baranchuk A, Tse G and Liu T:

Electrocardiographic features of immune checkpoint

inhibitor-associated myocarditis. Curr Probl Cardiol.

48:1014782023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Faron A, Isaak A, Mesropyan N, Reinert M,

Schwab K, Sirokay J, Sprinkart AM, Bauernfeind FG, Dabir D, Pieper

CC, et al: Cardiac MRI depicts immune checkpoint Inhibitor-induced

myocarditis: A prospective study. Radiology. 301:602–609. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Correction to. Routine application of

cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with suspected

myocarditis from immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Eur Heart J.

46:3042025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Pereyra M, Farina J, Mahmoud AK, Scalia I,

Tagle-Cornell MC, Kenyon C, Abbas MT, Baba N, Herrmann J, Arsanjani

R and Ayoub C: The prognostic value of criteria for diagnosis of

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Related Myocarditis: A comparison of

the Bonaca et al. Criteria and European Society of Cardiology

(ESC)-International Cardio-Oncology Society (ICOS) guidelines.

Circulation. 150 (Suppl 1):A41420442024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Salem JE, Bretagne M, Abbar B,

Leonard-Louis S, Ederhy S, Redheuil A, Boussouar S, Nguyen LS,

Procureur A, Stein F, et al: Abatacept/Ruxolitinib and screening

for concomitant respiratory muscle failure to mitigate fatality of

Immune-checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis. Cancer Discov.

13:1100–1115. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Thibault C, Vano Y, Soulat G and Mirabel

M: Immune checkpoint inhibitors myocarditis: Not all cases are

clinically patent. Eur Heart J. 39:35532018.

|

|

33

|

Domen H, Kaga K, Hida Y, Honma N, Kubota

R, Yagi Y and Matsui Y: Investigation of lung cancer patients with

cardiovascular disease. Kyobu Geka. 68:266–70. 2015.(In

Japanese).

|

|

34

|

Murtagh G, deFilippi C, Zhao Q and Barac

A: Circulating biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of immune

checkpoint inhibitor-related myocarditis: Time for a risk-based

approach. Front Cardiovasc Med. 11:13505852024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Palaskas N, Lopez-Mattei J, Durand JB,

Iliescu C and Deswal A: Immune checkpoint inhibitor myocarditis:

Pathophysiological characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am

Heart Assoc. 9:e0137572020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pi JK, Chen XT, Zhang YJ, Chen XM, Wang

YC, Xu JY, Zhou JH, Yu SS and Wu SS: Insight of immune checkpoint

inhibitor related myocarditis. Int Immunopharmacol. 143:1135592024.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Heilbroner SP, Few R, Mueller J, Chalwa J,

Charest F, Suryadevara S, Kratt C, Gomez-Caminero A and Dreyfus B:

Predicting cardiac adverse events in patients receiving immune

checkpoint inhibitors: A machine learning approach. J Immunother

Cancer. 9:e0025452021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Zhang C, Bockman A and DuPage M: Breaking

up the CD8+ T cell: Treg pas de deux. Cell Mol Immunol. 42:941–942.

2024.

|

|

39

|

Yu L, Sun M, Zhang Q, Zhou Q and Wang Y:

Harnessing the immune system by targeting immune checkpoints:

Providing new hope for oncotherapy. Front Immunol. 13:9820262022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ and Sharpe

AH: PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev

Immunol. 26:677–704. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Boussiotis VA: Molecular and biochemical

aspects of the PD-1 checkpoint pathway. N Engl J Med.

375:1767–1778. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yi M, Zheng X, Niu M, Zhu S, Ge H and Wu

K: Combination strategies with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: Current

advances and future directions. Mol Cancer. 21:282022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Gaikwad S, Agrawal MY, Kaushik I,

Ramachandran S and Srivastava SK: Immune checkpoint proteins:

Signaling mechanisms and molecular interactions in cancer

immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 86:137–150. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Malmberg R, Zietse M, Dumoulin DW,

Hendrikx JJMA, Aerts JGJVA, van der Veldt AAM, Koch BCP, Sleijfer

S, van Leeuwen RWF, Koch BCP, et al: Alternative dosing strategies

for immune checkpoint inhibitors to improve cost-effectiveness: A

special focus on nivolumab and pembrolizumab. Lancet Oncol.

23:e552–e561. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R,

Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D,

Ferrucci PF, et al: Overall survival with combined nivolumab and

ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 377:1345–1356. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Xu D, Wang H, Bao Q, Jin K, Liu M, Liu W,

Yan X, Wang L, Zhang Y, Wang G, et al: The anti-PD-L1/CTLA-4

bispecific antibody KN046 plus lenvatinib in advanced unresectable

or metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase II trial. Nat

Commun. 16:14432025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Schaub J and Tang SC: Beyond checkpoint

inhibitors: The three generations of immunotherapy. Clin Exp Med.

25:432025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Buehning F, Lerchner T, Vogel J,

Hendgen-Cotta UB, Totzeck M, Rassaf T and Michel L: Preclinical

models of cardiotoxicity from immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

Basic Res Cardiol. 120:171–185. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Wu MM, Yang YC, Cai YX, Jiang S, Xiao H,

Miao C, Jin XY, Sun Y, Bi X, Hong Z, et al: Anti-CTLA-4 m2a

antibody exacerbates cardiac injury in experimental autoimmune

myocarditis mice by promoting Ccl5-Neutrophil infiltration. Adv

Sci. 11:e24004862024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Shang AQ, Yu CJ, Bi X, Jiang WW, Zhao ML,

Sun Y, Guan H and Zhang ZR: Blocking CTLA-4 promotes pressure

Overload-induced heart failure via activating Th17 cells. FASEB J.

38:e238512024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Hossen MM, Ma Y, Yin Z, Xia Y, Du J, Huang

JY, Huang JJ, Zou L, Ye Z and Huang Z: Current understanding of

CTLA-4: From mechanism to autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol.

14:11983652023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Maurer MF, Lewis KE, Kuijper JL, Ardourel

D, Gudgeon CJ, Chandrasekaran S, Mudri SL, Kleist KN, Navas C,

Wolfson MF, et al: The engineered CD80 variant fusion therapeutic

davoceticept combines checkpoint antagonism with conditional CD28

costimulation for anti-tumor immunity. Nat Commun. 13:17902022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang J, Sanmamed MF, Datar I, Su TT, Ji L,

Sun J, Chen L, Chen Y, Zhu G, Yin W, et al: Fibrinogen-like protein

1 is a major immune inhibitory ligand of LAG-3. Cell.

176:334–347.e12. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Cillo AR, Cardello C, Shan F, Karapetyan

L, Kunning S, Sander C, Rush E, Karunamurthy A, Massa RC, Rohatgi

A, et al: Blockade of LAG-3 and PD-1 leads to Co-Expression of

cytotoxic and exhaustion gene modules in CD8+ T cells to promote

antitumor immunity. Cell. 187:4373–4388.e15. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Andrews LP, Butler SC, Cui J, Cillo AR,

Cardello C, Liu C, Brunazzi EA, Baessler A, Xie B, Kunning SR, et

al: LAG-3 and PD-1 synergize on CD8+ T cells to drive T cell

exhaustion and hinder autocrine IFN-γ-dependent anti-tumor

immunity. Cell. 187:4355–4372.e22. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Sordo-Bahamonde C, Lorenzo-Herrero S,

González-Rodríguez AP, Payer AR, González-García E, López-Soto A

and Gonzalez S: LAG-3 Blockade with Relatlimab (BMS-986016)

restores Anti-leukemic responses in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Cancers (Basel). 13:21122021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ,

Ascierto PA, Matamala L, Gutiérrez EC, Rutkowski P, Gogas HJ, Lao

CD, De Menezes JJ, et al: Relatlimab and nivolumab versus nivolumab

in untreated advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 386:24–34. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Schwartz RH: Historical overview of

immunological tolerance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

4:a0069082012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Chen X, Ghanizada M, Mallajosyula V, Sola

E, Capasso R, Kathuria KR and Davis MM: Differential roles of human

CD4+ and CD8+ regulatory T cells in controlling self-reactive

immune responses. Nat Immunol. 26:230–239. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Coutinho A, Caramalho I, Seixas E and

Demengeot J: Thymic commitment of regulatory T cells is a pathway

of TCR-dependent selection that isolates repertoires undergoing

positive or negative selection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol.

293:43–71. 2005.

|

|

61

|

Kisielow P: How does the immune system

learn to distinguish between good and evil? The first definitive

studies of T cell central tolerance and positive selection.

Immunogenetics. 71:513–518. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Spetz J, Presser AG and Sarosiek KA: T

cells and regulated cell death: Kill or be killed. Int Rev Cell Mol

Biol. 342:27–71. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Lv H, Havari E, Pinto S, Gottumukkala

RVSRK, Cornivelli L, Raddassi K, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A, Bronson

RT, Smith R, et al: Impaired thymic tolerance to α-Myosin directs

autoimmunity to the heart in mice and humans. J Clin Invest.

121:1561–1573. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Sur M, Rasquinha MT, Arumugam R,

Massilamany C, Gangaplara A, Mone K, Lasrado N, Yalaka B, Doiphode

A, Gurumurthy C, et al: Transgenic mice expressing functional TCRs

specific to cardiac Myhc-α 334–352 on Both CD4 and CD8 T cells are

resistant to the development of myocarditis on C57BL/6 genetic

background. Cells. 12:23462023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Nindl V, Maier R, Ratering D, De Giuli R,

Züst R, Thiel V, Scandella E, Di Padova F, Kopf M, Rudin M, et al:

Cooperation of Th1 and Th17 cells determines transition from

autoimmune myocarditis to dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Immunol.

42:2311–2321. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Raffin C, Vo LT and Bluestone JA: Treg

Cell-based therapies: Challenges and perspectives. Nat Rev Immunol.

20:158–172. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Cheru N, Hafler DA and Sumida TS:

Regulatory T cells in peripheral tissue tolerance and diseases.

Front Immunol. 14:11545752023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

ElTanbouly MA and Noelle RJ: Rethinking

peripheral T cell tolerance: Checkpoints across a T cell's journey.

Nat Rev Immunol. 21:257–267. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Bluestone JA and Anderson M: Tolerance in

the age of immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 383:1156–1166. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Pardoll DM: The blockade of immune

checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:252–264.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Sharpe AH and Pauken KE: The diverse

functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol.

18:153–167. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P,

Yamaguchi T, Miyara M, Fehervari Z, Nomura T and Sakaguchi S:

CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science.

322:271–275. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Aggarwal V, Workman CJ and Vignali DAA:

LAG-3 as the third checkpoint inhibitor. Nat Immunol. 24:1415–1422.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Grabie N, Lichtman AH and Padera R: T cell

checkpoint regulators in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 115:869–877.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Tan CL, Kuchroo JR, Sage PT, Liang D,

Francisco LM, Buck J, Thaker YR, Zhang Q, McArdel SL, Juneja VR, et

al: PD-1 restraint of regulatory T cell suppressive activity is

critical for immune tolerance. J Exp Med. 218:e201822322021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Zhang A, Ren Z, Tseng K-F, Liu X, Li H, Lu

C, Cai Y, Minna JD and Fu YX: Dual targeting of CTLA-4 and CD47 on

Treg cells promotes immunity against solid tumors. Sci Transl Med.

13:eabg86932021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Guo X, Wang H, Zhou J, Li Y, Duan L, Si X

and Zhang L, Fang L and Zhang L: Clinical manifestation and

management of immune checkpoint Inhibitor-associated

cardiotoxicity. Thorac Cancer. 11:475–480. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Huertas RM, Serrano CS, Perna C, Gómez AF

and Gordoa TA: Cardiac toxicity of Immune-checkpoint inhibitors: A

clinical case of Nivolumab-induced myocarditis and review of the

evidence and new challenges. Cancer Manag Res. 11:4541–4548. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Axelrod ML, Meijers WC, Screever EM, Qin

J, Carroll MG, Sun X, Tannous E, Zhang Y, Sugiura A, Taylor BC, et

al: T cells specific for α-Myosin drive Immunotherapy-related

myocarditis. Nature. 611:818–826. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Lim SY, Lee JH, Gide TN, Menzies AM,

Guminski A, Carlino MS, Breen EJ, Yang JYH, Ghazanfar S, Kefford

RF, et al: Circulating cytokines predict Immune-related toxicity in

melanoma patients receiving Anti-PD-1-based immunotherapy. Clin

Cancer Res. 25:1557–1563. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias

S, Gorham J, Xu Y, Hicks M, Puzanov I, Alexander MR, Bloomer TL, et

al: Fulminant myocarditis with combination immune checkpoint

blockade. N Engl J Med. 375:1749–1755. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S,

Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, Das S, Beckermann KE, Ha L, et al: Fatal

toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A

systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 4:1721–1728. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Martínez-Lostao L, Anel A and Pardo J: How

do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clin Cancer Res.

21:5047–5056. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Del Re DP, Amgalan D, Linkermann A, Liu Q

and Kitsis RN: Fundamental mechanisms of regulated cell death and