Introduction

Keloids are a common, chronic and inflammatory skin

disorder, characterized by benign fibroproliferative overgrowth of

the skin (1). Keloids grow

continuously and aggressively beyond the original wound boundaries,

resulting from cutaneous injury or abnormal wound healing

associated with inflammatory and fibrotic conditions (2–4).

Although it is not a life-threatening condition, the incidence of

keloids is relatively high, thus reducing the quality of life of

patients due to pain, pruritus and cosmetic reasons (5,6).

Various modalities, including surgery, radiation therapy and

intralesional steroid injections, have been used for the treatment

of keloids; however, they commonly relapse (7–9). In

addition, the underlying molecular mechanisms of keloid formation

remain largely unclear, thus restricting the development of

therapeutic strategies.

Numerous studies have investigated genes and

pathways associated with the pathophysiological processes involved

in the development of keloids, thus providing novel insights into

their onset (10–13). Notably, emerging evidence has

suggested that inflammatory etiologies, particularly chronic

inflammation, may be involved in the pathogenesis of keloids

(14,15). Furthermore, previous studies have

indicated that various pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and

their receptors could be notably upregulated in keloids and closely

associated with keloid inflammation (16–18).

For example, IL-17 can enhance the expression of C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand (CXCL)12 in keloids, which in turn promotes the

infiltration of C-X-C motif chemokine receptor (CXCR)4+

cells in keloid scars (18–20).

In addition, existing data have suggested that T helper 2

(Th2)-related cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-13, may act as crucial

mediators of keloid inflammation (21). Mechanistically, IL-4 and IL-13

could be involved into skin fibrosis via excessive fibroblast

proliferation and collagen deposition in keloids (21).

Previous cDNA microarray analyses have been

performed to compare the gene expression profiles of fibroblasts

between normal skin and keloid tissues. These analyses have

identified several gene and pathway alterations, such as those in

hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) (11), the fibrosis and Wnt signaling

pathway (22) and the

extracellular matrix (23), all of

which are closely associated with the pathogenesis of keloids.

Although gene chips could identify dysregulated

genes in keloid tissues, the small sample size and considerable

heterogeneity may affect data reproducibility. Therefore, the

present study retrieved several microarray datasets from the Gene

Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, with the aim of identifying

common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between keloid

fibroblasts (KFs) and normal fibroblasts (NFs). Then, gene

knockdown assays and RNA sequencing were performed to investigate

the expression profiles, functions and potential pathogenic

mechanisms of DEGs in keloids.

Materials and methods

Microarray data processing and

screening of target DEGs

Three independent keloid datasets, namely GSE145725

(11), GSE7890 (22) and GSE44270 (23), were obtained from the GEO

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). A

total of 19 samples from GSE145725 (10 NF and 9 KF samples), 10

samples from GSE7890 (5 NF and 5 KF samples) and 12 samples from

GSE44270 (3 NF and 9 KF samples) were selected for further analysis

(details are shown in Table I).

The original expression matrix was normalized and analyzed using R

package (version 4.2.1) (24).

DEGs were screened using the Limma package (25). Genes with P<0.05 and |log2 fold

change (FC)|>1 were defined as DEGs in GSE145725, GSE7890 and

GSE44270. TBtools was used to construct a Venn diagram to identify

common DEGs from the three datasets (26).

| Table I.Details of datasets used in the

present study. |

Table I.

Details of datasets used in the

present study.

| First author,

year | GEO accession

no. | Number of KF

samples | Number of NF

samples | KF samples | NF samples | Experiment

type/platform | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Smith et

al, | GSE7890 | 5 | 5 | GSM194109; | GSM194118; | Expression | (22) |

| 2008 |

|

|

| GSM194110; | GSM194119; | profiling by |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM194111; | GSM194120; | array/ |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM194112; | GSM194121; | GPL570 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM194113 | GSM194122 |

|

|

| Hahn et

al, | GSE44270 | 9 | 3 | GSM1081582; | GSM1081608; | Expression | (23) |

| 2013 |

|

|

| GSM1081583; | GSM1081609; | profiling by |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081584; | GSM1081610 | array/ |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081585; |

| GPL6244 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081586; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081587; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081588; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081589; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM1081590 |

|

|

|

| Kang et

al, | GSE145725 | 9 | 10 | GSM4331585; | GSM4331594; | Expression | (11) |

| 2020 |

|

|

| GSM4331586; | GSM4331595; | profiling by |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331587; | GSM4331596; | array/ |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331588; | GSM4331597; | GPL6244 |

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331589; | GSM4331598; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331590; | GSM4331599; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331591; | GSM4331600; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331592; | GSM4331601; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331593 | GSM4331602, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GSM4331603 |

|

|

Patients and specimen collection

All subjects (three patients with keloids and three

healthy controls) were recruited from February to May 2023 from the

Department of Dermatology, Peking University Shenzhen Hospital

(Shenzhen, China). The average age of patients with keloids was

28.3 years (range, 25–30 years), while the average age of healthy

individuals was 28.7 years (range, 23–37 years). A total of two men

and one woman were diagnosed with keloids, and sex-matched healthy

controls (two men and one woman) were included in the present

study. All of the patients with keloids enrolled in the current

study did not receive any topical therapy or systemic treatment for

≥1 month before skin biopsy. Biopsies from the non-lesional skin of

healthy volunteers were used as controls. Specimens were

immediately placed in ice-cold 1X PBS pre-mixed with 1X penicillin

and 1X streptomycin. The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Peking University Shenzhen Hospital and was conducted

in accordance with The Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed

consent was obtained from all participants.

Cell culture

Primary human dermal fibroblasts were isolated from

skin tissues obtained from the three patients with keloids and the

three healthy controls as previously described (27). Firstly, the epidermis and adipose

tissues were removed from the specimens obtained from the healthy

donors/patients with keloids. Subsequently, the dermis was cut into

0.25 cm2 sections and allowed to attach to a 10-cm

culture dish. Fibroblasts began to migrate out and proliferate from

the edges of the dermis onto the culture dish. This process yields

a pure population of fibroblasts for subsequent studies. The

fibroblasts obtained from keloid patients were designated KF#1,

KF#2 and KF#3, while those derived from healthy donors were labeled

NF#1, NF#2 and NF#3. The fibroblast cells were cultured in DMEM

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and

100 µg/ml streptomycin (all Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

in a CO2 incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Reagents, small interfering (si)RNAs

and antibodies

siRNAs targeting POSTN and IL-4R, as well as the

controls (si-CTL, forward, 5′-CCUAAGGUUAAGUCGCCCU-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGGGCGACUUAACCUUAGG-3′) were from Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.

The siRNA sequences targeting the POSTN gene were as follows:

si-POSTN#1, forward, 5′-GUGACAGUAUAACAGUAAA-3′ and reverse,

5′-UUUACUGUUAUACUGUCAC-3′; si-POSTN#2, forward,

5′-GGAUCAGCGCCUCCUUAAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-UUUAAGGAGGCGCUGAUCC-3′.

The siRNA sequences targeting the IL-4R gene were as follows:

si-IL-4R#1, forward, 5′-GUCAACAUUUGGAGUGAAA-3′ and reverse,

5′-UUUCACUCCAAAUGUUGAC-3′; si-IL-4R#2, forward,

5′-CUUCCACCUUCGGGAAGUA-3′ and reverse, 5′-UACUUCCCGAAGGUGGAAG-3′.

Antibodies against POSTN (cat. no. ab14041) and IL-4R (cat. no.

ab203398) were from Abcam, antibodies against phosphorylated

(p)-STAT1 (Tyr701) (cat. no. 9167), p-STAT1 (Ser727) (cat. no.

8826) and STAT1 (cat. no. 14994) were from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc., whereas the antibody against β-actin (cat. no.

AF5003) was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. The

SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit used for

signal detection in western blotting was obtained from Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc. (cat. no. 34095). All other reagents or

chemicals were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. unless

otherwise mentioned.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as described

previously (28). Briefly, protein

samples from fibroblasts were harvested using ice-cold RIPA buffer

containing 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1

mM NaF, 20 mM Na4P2O7, 1% Triton

X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS and 0.5% deoxycholate, and protease

and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. The protein concentration was

determined using the BCA method (cat. no. 5000002; Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.). A total of 10 µg/lane protein was separated

using a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, after which they were transferred onto

PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with blocking buffer

(cat. no. ST023; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at

room temperature, and incubated with primary antibodies (1:1,000)

as follows: phosphorylated (p)-STAT1 (Tyr701) (cat. no. 9167),

p-STAT1 (Ser727) (cat. no. 8826) and STAT1 (cat. no. 14994; all

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; β-actin (cat. no. AF5003) was from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. The membranes were incubated

with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the

corresponding secondary antibodies, goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L

(HRP) (cat. no. ab205718; 1:10,000; Abcam) for p-STAT1 (Tyr701),

p-STAT1 (Ser727) and STAT1 and m-IgGκ BP-HRP (cat. no. sc-516102;

dilution: 1:10,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for β-actin,

were incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The signals were

detected using the SuperSignal West Femto Chemiluminescent

Substrate Kit (cat. no. 34095; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The

images were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.54; National

Institutes of Health) and the relative content of the target

protein was expressed as the gray value of the target

protein/β-actin gray value. A total of three biological replicates

was performed for each treatment group.

Immunofluorescence staining

POSTN levels in KFs were detected using

immunofluorescence staining as described previously (29). Briefly, cells were fixed using 4%

paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min, followed by

permeabilization for 10 min at room temperature using 0.1% Triton

X-100 (cat. no. P0096; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Cells

were blocked with blocking solution (cat. no. P0102; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature, followed

by incubation with the primary antibody against POSTN (cat. no.

ab14041; dilution: 1:100; Abcam) at 4°C overnight. After washing

off the primary antibody, an Alexa Fluor555-labeled donkey

anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (cat. no. A0453; 1:200;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) was applied for 30 min at room

temperature. For immunofluorescence staining, cells were

counterstained with DAPI (cat. no. ab104139; Abcam) at room

temperature for 15 min, and fluorescence microscopy (Nikon Inc.,

Melville, NY) was used for observation.

RNA isolation and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol®

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently,

RT-qPCR was performed as described previously (29). Briefly, total RNA was

reverse-transcribed into cDNA using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT kit (cat.

no. FSQ-201; Toyobo Life Science) with the following temperature

protocol: 37°C for 15 min, 50°C for 5 min, and 98°C for 5 min. qPCR

was performed using iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix

(cat. no. 1725121; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) with an initial

denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec and the following thermocycling

conditions: 95°C for 10 sec, 59°C for 25 sec and 72°C for 30 sec

for 40 cycles. The relative mRNA expression levels of target genes

were normalized to those of GAPDH using the 2−ΔΔCq

method (30). All of the primers

used in the present study were designed using the online software

PrimerBank (https://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/index.html).

The primer sequences were as follows: GAPDH-forward (F),

5′-ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG-3′, GAPDH-reverse (R),

5′-GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC-3′; POSTN-F, 5′-CTCATAGTCGTATCAGGGGTCG-3′,

POSTN-R, 5′-ACACAGTCGTTTTCTGTCCAC-3′; IL-4R-F,

5′-CGTGGTCAGTGCGGATAACTA-3′, IL-4R-R, 5′-TGGTGTGAACTGTCAGGTTTC-3′.

CCNA1-F, 5′-GAGGTCCCGATGCTTGTCAG-3′, CCNA1-R,

5′-GTTAGCAGCCCTAGCACTGTC-3′; CCNA2-F, 5′-CGCTGGCGGTACTGAAGTC-3′,

CCNA2-R, 5′-GAGGAACGGTGACATGCTCAT-3′; CCNB1 F,

5′-AATAAGGCGAAGATCAACATGGC-3′, CCNB1-R,

5′-TTTGTTACCAATGTCCCCAAGAG-3′; CCNB2 F, 5′-CCGACGGTGTCCAGTGATTT-3′,

CCNB2-R, 5′-TGTTGTTTTGGTGGGTTGAACT-3′; CCNC-F,

5′-CCTTGCATGGAGGATAGTGAATG-3′, CCNC-R,

5′-AAGGAGGATACAGTAGGCAAAGA-3′; CCND3-F, 5′-TACCCGCCATCCATGATCG-3′,

CCND3-R, 5′-AGGCAGTCCACTTCAGTGC-3′; CCNE2-F

5′-TCAAGACGAAGTAGCCGTTTAC-3′, CCNE2-R,

5′-TGACATCCTGGGTAGTTTTCCTC-3′; CDK1-F 5′-AAACTACAGGTCAAGTGGTAGCC-3′

and R, 5′-TCCTGCATAAGCACATCCTGA-3′; CDK2-F,

5′-CCAGGAGTTACTTCTATGCCTGA-3′, CDK2-R, 5′-TTCATCCAGGGGAGGTACAAC-3′;

CDK3-F, 5′-GAAGGTAGAGAAGATCGGAGAGG-3′, CDK3-R,

5′-GTCCAGCAGTCGGACGATG-3′; CDK4-F, 5′-ATGGCTACCTCTCGATATGAGC-3′,

CDK4-R, 5′-CATTGGGGACTCTCACACTCT-3′; CDK5-F,

5′-GGAAGGCACCTACGGAACTG-3′, CDK5-R, 5′-GGCACACCCTCATCATCGT-3′;

JAK1-F, 5′-CTTTGCCCTGTATGACGAGAAC-3′, JAK1-R,

5′-ACCTCATCCGGTAGTGGAGC-3′; JAK2-F, 5′-TCTGGGGAGTATGTTGCAGAA-3′,

JAK2-R, 5′-AGACATGGTTGGGTGGATACC-3′; STAT1-F,

5′-CGGCTGAATTTCGGCACCT-3′, STAT1-R, 5′-CAGTAACGATGAGAGGACCCT-3′;

STAT2-F, 5′-CCAGCTTTACTCGCACAGC-3′, STAT2-R,

5′-AGCCTTGGAATCATCACTCCC-3′; IFNAR2-F,

5′-TCATGGTGTATATCAGCCTCGT-3′, IFNAR2-R,

5′-AGTTGGTACAATGGAGTGGTTTT-3′; IFNGR1-F,

5′-TCTTTGGGTCAGAGTTAAAGCCA-3′, IFNGR1-R,

5′-TTCCATCTCGGCATACAGCAA-3′; CXCL1-F, 5′-GCCAGTGCTTGCAGACCCT-3′,

CXCL1-R, 5′-GGCTATGACTTCGGTTTGGG-3′; CXCL2-F,

5′-CAAACCGAAGTCATAGCCAC-3′ and R, 5′-TCTGGTCAGTTGGATTTGCC-3′;

CXCL5-F, 5′-AGCTGCGTTGCGTTTGTTTAC-3′, CXCL5-R,

5′-TGGCGAACACTTGCAGATTAC-3′; CXCL8-F, 5′-TCTGTCTGGACCCCAAGGAA-3′,

CXCL8-R, 5′-GCATCTGGCAACCCTACAACA-3′; CXCL12-F,

5′-ATTCTCAACACTCCAAACTGTGC-3′, CXCL12-R,

5′-ACTTTAGCTTCGGGTCAATGC-3′; CCL2-F, 5′-CAGCCAGATGCAATCAATGCC-3′,

CCL2-R, 5′-TGGAATCCTGAACCCACTTCT-3′; CCL28-F,

5′-TGCACGGAGGTTTCACATCAT-3′, CCL28-R, 5′-TTGGCAGCTTGCACTTTCATC-3′;

IL33-F, 5′-GTGACGGTGTTGATGGTAAGAT-3′ and R,

5′-AGCTCCACAGAGTGTTCCTTG-3′; IL34-F, 5′-CCTGGCTGCGCTATCTTGG-3′,

IL34-R, 5′-AGTGTTTCATGTACTGAAGTCGG-3′; LIF-F,

5′-CCAACGTGACGGACTTCCC-3′, LIF-R, 5′-TACACGACTATGCGGTACAGC-3′;

LIFR-F, 5′-TGGAACGACAGGGGTTCAGT-3′, LIFR-R,

5′-GAGTTGTGTTGTGGGTCACTAA-3′; TSLP-F,

5′-ATGTTCGCCATGAAAACTAAGGC-3′, TSLP-R, 5′-GCGACGCCACAATCCTTGTA-3′;

GDF5-F, 5′-GCTGGGAGGTGTTCGACATC-3′, GDF5-R,

5′-CACGGTCTTATCGTCCTGGC-3′; FAS-F, 5′-AGATTGTGTGATGAAGGACATGG-3′,

FAS-R, 5′-TGTTGCTGGTGAGTGTGCATT-3′; OSMR-F,

5′-AATGTCAGTGAAGGCATGAAAGG-3′, OSMR-R, 5′-GAAGGTTGTTTAGACCACCCC-3′;

COL4A5-F, 5′-TGGACAGGATGGATTGCCAG-3′, COL4A5-R,

5′-GGGGACCTCTTTCACCCTTAAAA-3′; COL6A6-F,

5′-TTCAACATTGCTCCCCATAAGG-3′ and R, 5′-GTGTTTGTATTCCCACCCATCT-3′;

DST-F, 5′-CTACCAGCACTCGAACCAGTC-3′, DST-R,

5′-GCCGAAGCTAATGCAAGAGTTG-3′; MMP3-F, 5′-CTGGACTCCGACACTCTGGA-3′,

MMP3-R, 5′-CAGGAAAGGTTCTGAAGTGACC-3′.

Cell transfection, IFNα, IFNβ, IL-4

and/or IL-13 treatment, cell counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay, EdU Cell

Proliferation assay and cell cycle assay

Cells were cultured until they reached 70%

confluence and were then transfected with 100 nM POSTN or IL-4R

siRNAs at 37°C for 24 h using Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX

Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were

transfected with siRNAs for 24 h prior to subsequent experiments.

Cells were treated with recombinant human IFNs or IL-4/IL-13. For

IFNα and IFNβ treatment, cells were incubated with recombinant

human IFNα (cat. no. 300-02AA; 50 ng/ml) and IFNβ (cat. no.

300-02BC; 50 ng/ml) (both from PeproTech; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) at 37°C for 15 min when cells reached 90% confluence, control

cells were treated with PBS under the same conditions. For IL-4

and/or IL-13 treatment, cells were incubated with recombinant human

IL-4 (cat. no. 200-04; 50 ng/ml) and/or IL-13 (cat. no. 200-13; 50

ng/ml) (both from PeproTech; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at

37°C for 24 h when cells reaching 90% confluent, control cells were

treated with PBS under the same conditions. Following the

manufacturer's instructions, the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

(cat. no. A311-01; Vazyme) was performed to evaluate cell

proliferation rates. Cells were seeded on a 96-well plates with a

density of 1×104 KFs/well for the POSTN knockdown

experiment. After siRNA transfection for 24 h at 37°C, CCK-8

reagent was added to the KFs and incubated for 2 h at 37°C.

Finally, a microplate reader (Infinite 200PRO; Tecan Group, Ltd.)

was used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm. EdU Cell

Proliferation assay was performed using an EdU Cell Proliferation

Kit with Alexa Fluor 555 according to the manufacturer's

instruction (cat. no. MA0425-1; Dalian Meilun Biology Technology

Co., Ltd.). For nuclear staining, cells were counterstained with

Hoechst at room temperature for 10 min and confocal microscopy was

used to acquire images. The cell cycle assay was performed as

described previously (31).

Briefly, trypsinised cells were fixed in pre-cooled 70% ethanol at

4°C for 30 min. Following incubation in 50 µg/ml propidium iodide

solution in the presence of RNase for 30 min at room temperature,

the cells were analyzed using a flow cytometry instrument (FACS

Calibur; Becton Dickinson, Franklin, NJ), and the data were

processed with the MODFIT software (Verity Software House, Topsham,

ME). At least three independent experiments were carried out for

each treatment.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and data

analysis

Total RNA was extracted from si-POSTN- and

si-CTL-transfected KFs using TRI Reagent® (cat. no.

T9424; MilliporeSigma). Purified RNA was quantified and qualified,

before library quality was assessed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer

(Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The cDNA library was constructed

using a Fast RNA-seq Lib Prep kit V2 (cat. no. RK20306; ABclonal)

and the library was sequenced using Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform

(Illumina, Inc.) with the Novaseq 6000 S4 reagent Kit (cat. no.

20027466; Illumina, Inc.) by Novogene Co., Ltd. Sequencing was

carried out on the Illumina platform using paired-end sequencing

with a read length of 150 bp. The final library was quantified

using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

the final concentration was adjusted to 1.5 nM. The original

expression matrix was normalized and analyzed using HiSaT2 (v2.0.5;

daehwankimlab.github.io/hisat2/) and featureCounts (v1.5.0-p3;

subread.sourceforge.net/). DEseq2 software (v1.20.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html)

was used to detect the DEGs between the two groups; DEGs with

|log2FC|>1 and FDR<0.05 were considered significant.

Visualization of a boxplot, heatmap and volcano plot, as well as

gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and Reactome analysis were

performed using R software (v4.3.2; http://www.r-project.org/).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times

unless otherwise stated. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0

software (Dotmatics). For two-group comparisons, unpaired Student's

t-test was applied, while one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post

hoc test was employed for multiple group comparisons. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

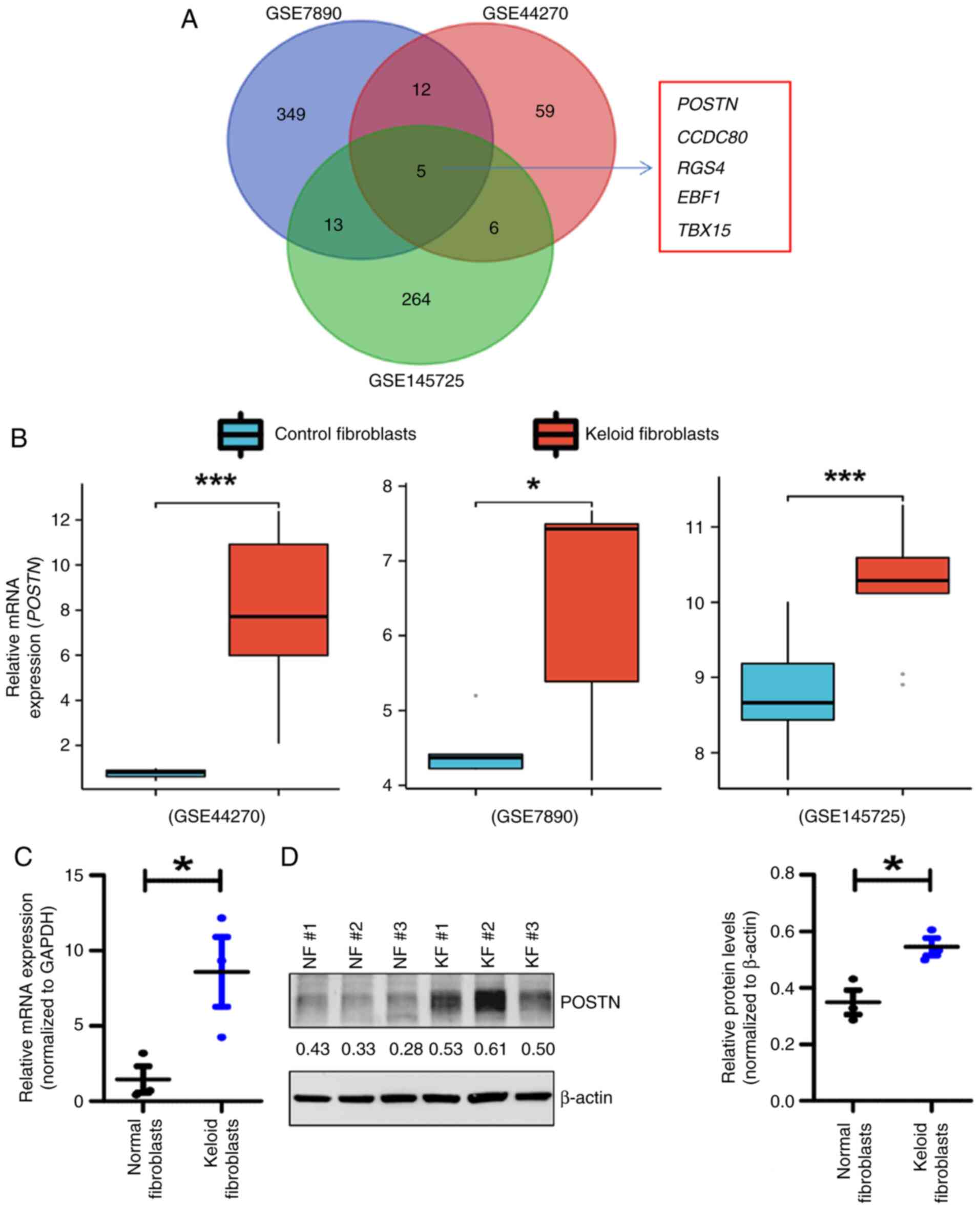

POSTN is upregulated in KFs

GSE7890, GSE44270 and GSE145725 datasets,

encompassing the expression profiles of genes in control

fibroblasts from healthy individuals and KFs from patients, were

downloaded from the GEO database. DEGs were defined as those with

significant differential expression between KFs and NFs, with

P<0.05 and |log2FC|>1. Upregulated DEGs were considered those

which were highly expressed in KFs compared with NFs. Notably, a

total of 82,379 and 288 upregulated DEGs were identified in the

GSE44270, GSE7890 and GSE145725 datasets, respectively (Fig. 1A). Additionally, a Venn diagram

revealed that five upregulated DEGs overlapped among the

aforementioned three datasets. Specifically, POSTN, CCDC80, RGS4,

EBF1 and TBX15 were upregulated in KFs compared with NFs. Among

these five genes, POSTN was more significantly upregulated in KFs

(Fig. 1B). Previous studies have

indicated that POSTN is markedly dysregulated in keloids, thus

supporting its potential role in the pathogenesis of keloid

(32,33). Therefore, POSTN was identified as a

gene that could be potentially associated with keloid development.

Subsequently, to detect the expression profile of POSTN in KFs and

NFs derived from patients recruited for the present study, RT-qPCR,

western blotting and immunofluorescence assays were performed.

Consistent with the results of bioinformatics analysis, the mRNA

expression levels of POSTN were significantly higher in KFs

compared with those in NFs (Fig.

1C). Furthermore, western blot analysis (Fig. 1D) and immunofluorescence staining

assays (Fig. S1) demonstrated

that the protein expression levels of POSTN were markedly increased

in KFs compared with those in NFs. Based on these results, it was

hypothesized that POSTN could represent a potential modulator of

keloid pathogenesis.

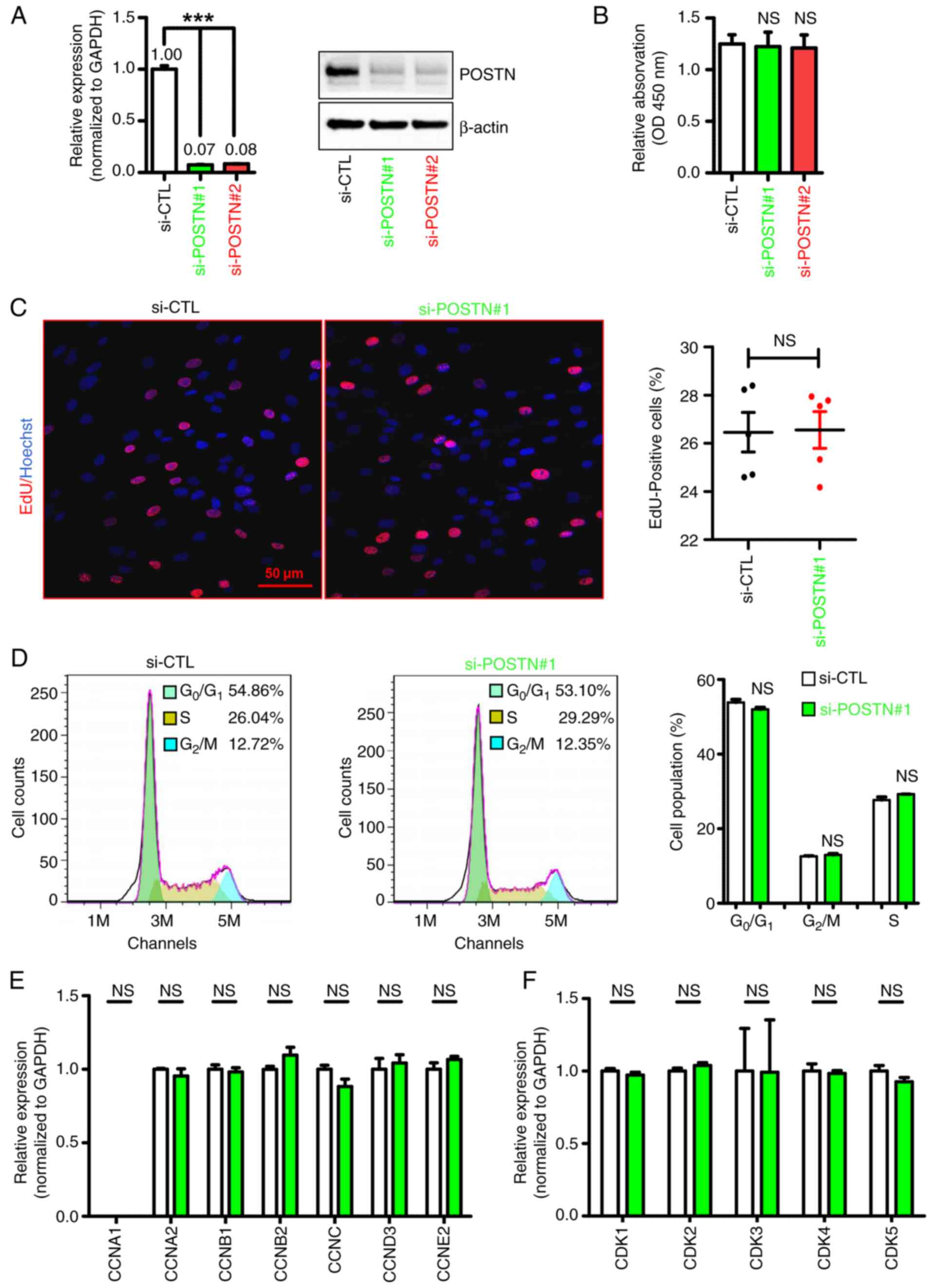

POSTN knockdown exerts limited effects

on the proliferation of KFs

To assess the regulatory role of POSTN in the

pathogenesis of keloids, the endogenous expression of POSTN was

silenced in KFs using siRNA (si-POSTN) technology. As shown in

Fig. 2A, POSTN expression was

significantly decreased in KFs transfected with si-POSTN compared

with that in the control cells; the knockdown efficiencies of

si-POSTN#1 and si-POSTN#2 were 93 and 92%, respectively (Fig. 2A). Since the knockdown efficiency

of si-POSTN#1 is higher than that of si-POSTN#2, we selected

si-POSTN#1 for subsequent experiments unless otherwise noted. The

CCK-8 assay demonstrated that POSTN silencing exerted no effect on

the proliferation of KFs (Fig.

2B). Additionally, the EdU incorporation assay revealed that

cell proliferation was comparable between KFs transfected with

si-POSTN and si-CTL (Fig. 2C),

thus suggesting that POSTN silencing had no notable effect on

fibroblast proliferation. Furthermore, flow cytometry was utilized

to examine whether POSTN knockdown could affect cell cycle

distribution in KFs. As shown in Fig.

2D, no changes were detected in the proportion of cells in the

G0/G1 or S phases of the cell cycle between

the si-POSTN and si-CTL groups, thus indicating that POSTN

knockdown did not affect the cell cycle distribution of KFs. To

further investigate the effect of POSTN on KF proliferation, the

expression levels of cell proliferation- and cell cycle-related

genes were detected in si-POSTN- and si-CTL-transfected KFs. In

line with the aforementioned results, the RT-qPCR analysis results

showed that POSTN knockdown did not alter the expression levels of

the majority of cell proliferation- and cell cycle-related genes in

KFs, since the expression levels of CCNA1/A2/B1/B2/C/D3/E2 and

CDK1/2/3/4/5 were comparable between the si-POSTN and si-CTL groups

(Fig. 2E and F). Collectively,

these findings suggested that POSTN knockdown exerted limited

effects on the proliferation of KFs.

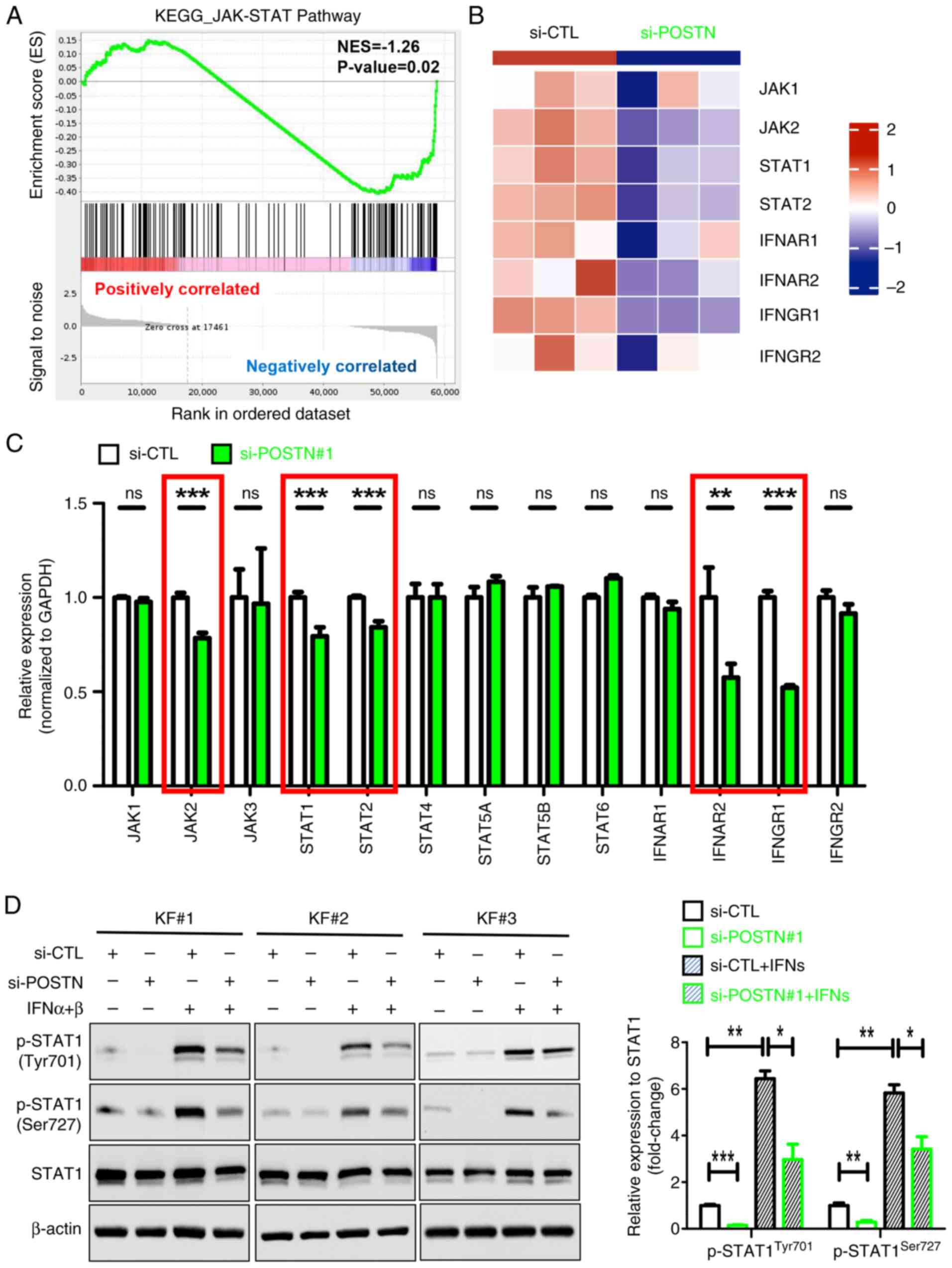

POSTN knockdown inhibits the JAK/STAT

signaling and the expression of proinflammatory factors in KFs

To further explore the role of POSTN in KFs, cells

transfected with si-POSTN and si-CTL were subjected to RNA-seq.

Notably, a total of 3,893 DEGs were identified between the two

groups, including 1,856 upregulated and 2,037 downregulated genes

(Fig. S2). Subsequently, GSEA was

performed to investigate the potential biological functions of

these DEGs, which could be involved in keloid pathogenesis. The

results showed that the majority of genes were enriched in

‘JAK/STAT signaling pathway’, ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor

interaction’, ‘NF-kappa B’, ‘natural killer cell-mediated

cytotoxicity’, ‘antigen processing’ and ‘TNF’ signaling pathways

(Fig. S3). Emerging evidence has

suggested that the JAK/STAT signaling pathway and proinflammatory

cytokines, such as CXCL12, C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)2 and

thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), serve crucial roles in the

pathogenesis of keloids (19,20,34).

Therefore, the current study mainly focused on the regulatory

effect of POSTN on the ‘JAK/STAT signaling pathway’ (Fig. 3A) and ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor

interaction’ (Fig. 4A) in KFs.

Heatmap analysis showed that the expression of the JAK/STAT

pathway-related DEGs was evidently altered in si-POSTN-transfected

KFs compared with in si-CTL-transfected KFs (Fig. 3B). In addition, the expression

levels of JAK/STAT pathway-related genes, including JAK2, STAT1/2,

IFNAR2 and IFNGR1, were significantly decreased in POSTN-depleted

KFs (Fig. 3C, marked in red

boxes). Furthermore, POSTN silencing markedly reduced the protein

expression levels of p-STAT1 (Tyr701) and p-STAT1 (Ser727) in KFs,

regardless of IFN-α/β treatment (Fig.

3D). Collectively, these results suggested that POSTN may be

involved in the activation of JAK/STAT signaling in KFs.

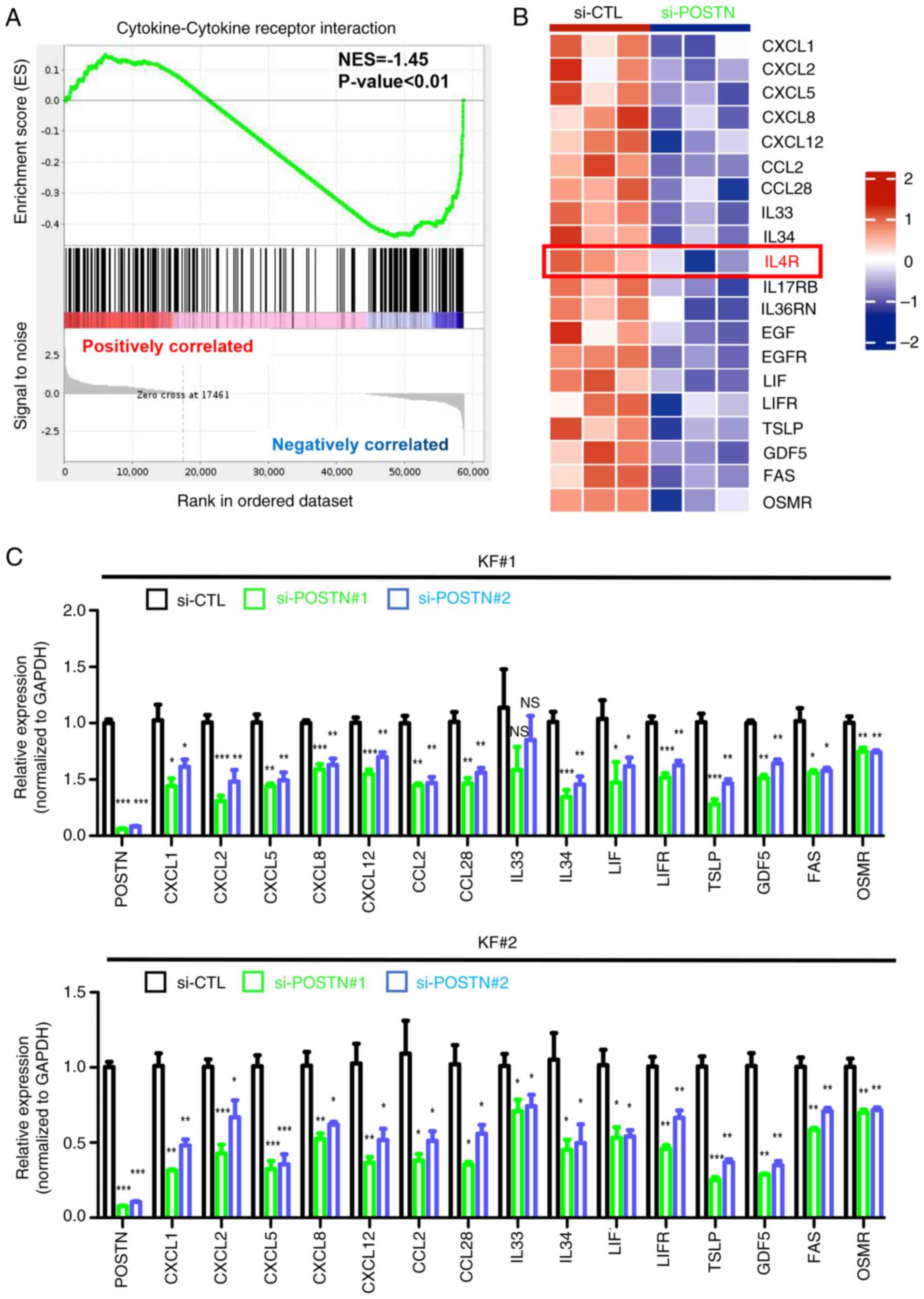

The expression pattern of DEGs associated with

‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ is presented in a heatmap

in Fig. 4B. To further validate

the significance of POSTN expression in the production of

proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines, POSTN was silenced in KFs

derived from two different patients with keloids using two sets of

specific si-POSTN constructs. RT-qPCR indicated mRNA expression

levels of keloid inflammation-related DEGs, including

CXCL1/CXCL2/CXCL5/CXCL8/CXCL12, CCL2/CCL28, IL33/IL34, LIF/LIFR,

TSLP, GDF5, FAS and OSMR, were similar between the two patients

(Fig. 4C). Notably, the majority

of DEGs were downregulated in POSTN-depleted KFs compared with in

control cells, thus indicating that POSTN could modulate the

expression of inflammatory cytokines in KFs. Taken together, the

aforementioned findings suggested that POSTN could serve a key role

in maintaining keloid inflammation.

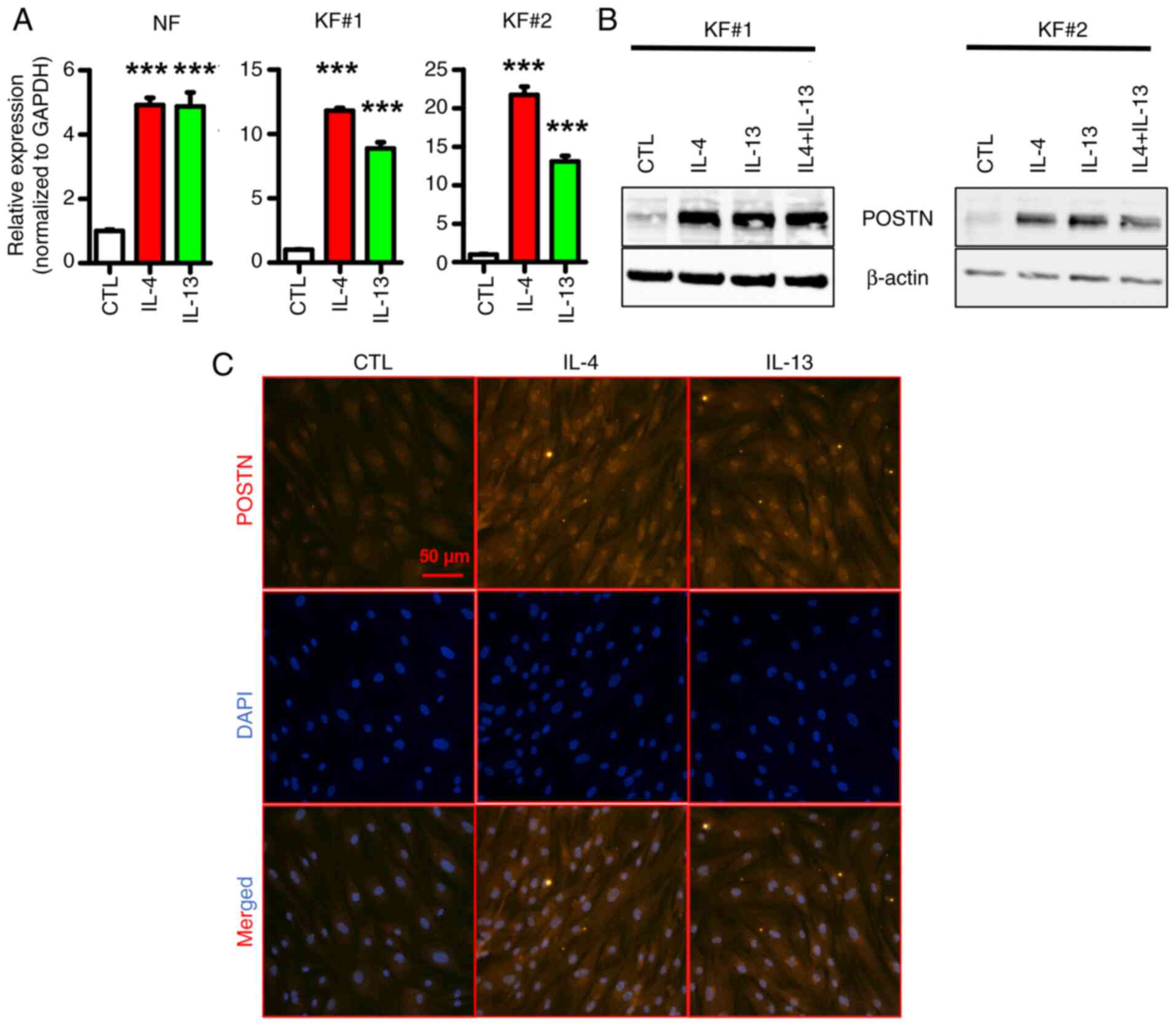

IL-4 and/or IL-13 upregulates POSTN in

KFs

Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-4 and

IL-13, two signature type 2 cytokines, can induce the expression of

POSTN in inflammation-related diseases such as atopic dermatitis

and bronchial asthma (35–37). Notably, another study showed that

Th2 markers are significantly upregulated in keloid lesions

compared with in normal skin, thus suggesting that keloid

pathogenesis could be triggered by Th2 cytokines (32). Therefore, the present study

explored whether IL-4 and/or IL-13 could induce POSTN expression in

KFs. As shown in Fig. 5A and B,

treatment of primary fibroblasts with IL-4 and/or IL-13 notably

induced POSTN expression, at both the mRNA (Fig. 5A) and protein levels (Fig. 5B). Additionally, the

immunofluorescence staining results further verified that IL-4 and

IL-13 could induce the protein expression of POSTN in KFs (Fig. 5C). These results suggested that

IL-4 and/or IL-13 could upregulate POSTN in KFs.

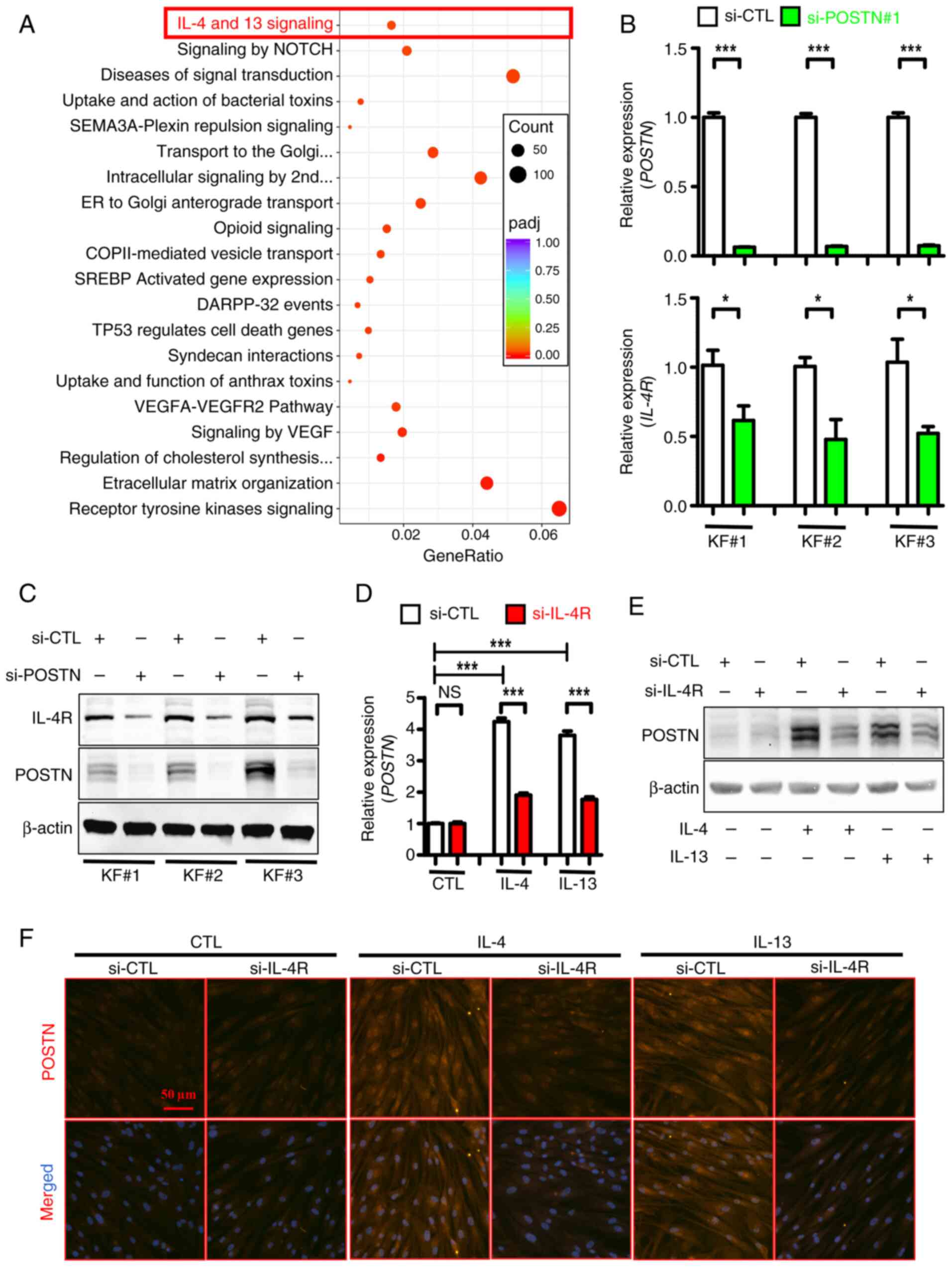

IL-4R is essential for

IL-4/IL-13-induced POSTN upregulation in KFs

Notably, Reactome enrichment analysis revealed that

the ‘IL-4 and IL-13 signaling’ pathway was significantly enriched

in DEGs between POSTN-depleted and control KFs (Fig. 6A, highlighted in red). This finding

was consistent with previous reports suggesting that POSTN is

strongly involved in Th2 cell-mediated inflammation (38,39).

Notably, the mRNA (Fig. 6B) and

protein (Fig. 6C) expression

levels of IL-4R, a cytokine receptor for both IL-4 and IL-13, were

notably inhibited in POSTN-depleted KFs derived from three patients

with keloids. Additionally, protein expression levels of IL-4R and

POSTN were higher in KFs compared with NFs, suggesting a positive

association of the expression between these two proteins in primary

fibroblasts (Fig. S4A). The

aforementioned finding indicated that POSTN could positively

regulate IL-4R expression in KFs. Subsequently, to verify the role

of Th2 signaling in inducing POSTN expression, IL-4R was silenced

in KFs using specific siRNAs (Fig.

S4B) and POSTN expression was then detected in the presence or

absence of IL-4/IL-13 treatment. As shown in Fig. 6D, treatment of KFs with human

recombinant IL-4/IL-13 upregulated POSTN, while its mRNA levels

were notably reduced in IL-4R-depleted KFs induced by IL-4/IL-13.

In line with this finding, western blot analysis showed that

stimulation of KFs with IL-4/IL-13 markedly increased the protein

levels of POSTN, which were reduced following IL-4R knockdown

(Fig. 6E). Subsequent

immunofluorescence analysis further verified that the protein

levels of POSTN were reduced in IL-4R-depleted KFs compared with

control KFs in the presence of IL-4/IL-13 stimulation (Fig. 6F). Collectively, these results

indicated that IL-4R, which could be positively regulated by POSTN,

was necessary for the IL-4/IL-13-induced upregulation of POSTN in

KFs, thus supporting the presence of a positive feedback loop

between POSTN and Th2 signaling.

POSTN knockdown inhibits the

expression of genes associated with extracellular matrix formation

in KFs

Reactome enrichment analysis also revealed

significant enrichment of extracellular matrix organization-related

signaling in DEGs between si-POSTN- and si-CTL-transfected KFs

(Fig. 6A). This was further

supported by a heatmap analysis (Fig.

S5A), which highlighted the significance of POSTN in regulating

extracellular matrix remodeling. Additionally, RT-qPCR analysis

verified that the mRNA expression levels of extracellular

matrix-related DEGs, including COL4A5, COL6A6, DST, and MMP3, were

significantly decreased in POSTN-depleted KFs (Fig. S5B). Overall, POSTN could

positively regulate extracellular matrix formation in KFs, a

process involved in the pathogenesis of keloids.

Discussion

Keloids are a chronic and inflammatory skin

condition, characterized by fibroproliferative overgrowth of the

skin (1). Keloids are considered

to result from abnormal wound healing in susceptible individuals

following trauma, inflammation, surgery and burns (2). Keloids are not life-threatening;

however, they can affect the quality of life of patients due to

pain and itching, and they can easily relapse even if surgically

removed (5,6,40).

The precise mechanism underlying keloid pathogenesis remains

unknown; therefore, identifying the pathological mechanisms of

keloids is of importance for the development of novel and efficient

therapeutic strategies.

Previous microarray analyses have identified several

genetic alterations associated with keloid pathogenesis, such as

HIF-1α (11), Wnt signaling

(22) and extracellular matrix

(23). However, the sample sizes

in the aforementioned studies were relatively small and the

heterogeneity was high, possibly resulting in biased results. To

accurately screen genes involved in keloid formation, three

datasets, namely GSE7890, GSE44270 and GSE145725, from the GEO

database were compared in the current study to identify common DEGs

between KFs and NFs. By comprehensively analyzing the gene

expression profiles of these three GEO datasets, a total of five

common DEGs overlapping between the three datasets were identified,

namely POSTN, CCDC80, RGS4, EBF1 and TBX15, which were all

upregulated in KFs compared with NFs. Among these five genes, it

has been reported that POSTN is markedly dysregulated in keloids,

thus indicating its possible role in keloid pathogenesis (32,33).

Consistently, the mRNA and protein levels of POSTN were also

elevated in KFs isolated from patients with keloids. To the best of

our knowledge, only a few studies have systematically investigated

the role of POSTN in keloid formation (32,33,41).

Therefore, POSTN, a notable candidate gene associated with keloid

development, was selected for further investigation.

POSTN, a matricellular protein that belongs to the

fasciclin family, serves key roles in skin development, skin

remodeling/repair and skin-related diseases (42–44).

A previous study demonstrated that POSTN is substantially expressed

in the dermis of patients with psoriasis, eventually leading to

epidermal hyperplasia and the pathogenesis of psoriasis (36). Another study on atopic dermatitis

also suggested that POSTN may be involved in the pathogenesis of

allergic skin inflammation by inducing TSLP production and

disrupting barrier function (37).

However, the role of POSTN in keloids has not been systematically

investigated. In the present study, RNA interference technology was

applied to evaluate the role of POSTN in KFs, which are the most

common cells involved in keloid formation. Notably, POSTN knockdown

had limited effects on the proliferation of KFs, as evidenced by

the comparable cell counts, EdU incorporation rates and cell cycle

distribution between KFs transfected with si-POSTN and those

transfected with si-CTL. Keloid is featured by unrestricted

fibroproliferative overgrowths of the skin (45). The current study revealed that

POSTN silencing could not affect the growth and proliferation of

KFs; this could be due to the limited sensitivity of the examined

fibroblasts to growth inhibition. Additionally, certain types of

fibroblasts may exert distinct biological functions. It would

therefore be of interest to investigate other functions of POSTN,

such as its involvement in fibrosis, extracellular matrix

production and inflammation, within these particular types of

KFs.

To further explore the role of POSTN in keloid

pathogenesis, KFs transfected with si-POSTN or si-CTL were

subjected to RNA-seq. The results demonstrated that the JAK/STAT

pathway, which has previously been involved in the pathogenesis of

keloids (46), was markedly

affected by POSTN knockdown in KFs. Additionally, GSEA further

revealed that the cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway

was significantly altered by POSTN silencing. These findings were

further validated using two sets of si-POSTN constructs in KFs

derived from two different patients with keloids. Specifically, the

expression levels of genes associated with keloid inflammation,

including CXCL1/CXCL2/CXCL5/CXCL8/CXCL12, CCL2/CCL28, IL33/IL34,

TSLP, GDF5 and OSMR, were markedly decreased in POSTN-deficient

KFs, when compared with control cells. Based on these observations,

it was hypothesized that POSTN could be involved in the

pathogenesis of keloids, at least in part, by regulating the

inflammatory response within KFs.

It has been well established that chronic

inflammation and immune responses serve key roles in keloid

formation (14–16). Several studies have reported the

upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines in keloid lesions,

including TSLP, IL-4, IL-13, CXCL8, CXCL12 and CCL2 (4–7,19,34,47,48).

Furthermore, Wu et al (32)

reported that keloid tissues are characterized by an inflammatory

microenvironment, including activated Th2 (IL-4R and TSLP), Th1

(CXCL10/11) and Th17/Th22 (CCL20) pathways, underscoring their

roles in keloid pathogenesis. Among the aforementioned cytokines,

CXCL12 is considered a critical mediator, and a previous study

showed that CXCL12 is upregulated in keloid scars compared with

normal skin (19). However, the

underlying mechanism remains unclear. Herein, the current study

demonstrated that POSTN knockdown could downregulate CXCL12 in KFs,

thus providing a potential explanation for its dysregulation in

keloids. Consequently, CXCL12 accumulation could be involved in

keloid pathology via the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis, thus promoting cell

chemotaxis and the recruitment of inflammatory cells into keloid

tissues, eventually sustaining chronic inflammation (20). Notably, TSLP, which was also shown

to be positively regulated by POSTN in KFs in the present study, is

known to induce the infiltration of CXCR4+ fibrocytes by

upregulating CXCL12 in keloid scars (19). A previous study also revealed the

hyperactivation of MCP-1 (CCL2) in keloid lesions (49), which is in consistent with the

findings of the current study. In addition, elevated CCL2 release

in keloid tissues could augment fibroblast proliferation, thus

initiating keloid development (49). The aforementioned findings

collectively support the role of inflammatory cytokines and

chemokines in promoting the pathogenesis of keloids.

The current study showed that POSTN expression was

increased in KFs, while the expression of inflammatory factors was

reduced in POSTN-depleted KFs, thus indicating a positive

association between POSTN and inflammatory signaling in keloid

pathogenesis. Therefore, targeting the inflammatory

microenvironment by reducing the expression of these cytokines

and/or inhibiting POSTN, could reverse the inflammatory process and

offer a potential treatment strategy for keloid therapy. However,

due to the lack of a robust in vivo model for keloids, it

remains challenging to definitively conclude that POSTN could be

directly involved in keloid formation through regulating the

inflammatory responses. Therefore, the establishment of an

effective animal model for keloids could help in addressing this

limitation. It has been reported that IL-4 and IL-13 generation is

enhanced in keloid lesions compared with in normal skin (50). However, herein, abnormal expression

of IL-4/IL-13 in POSTN-deficient KFs was not observed (data not

shown), possibly due to the fact that IL-4/IL-13 are primarily

secreted by immune cells rather than fibroblasts. In terms of scar

formation, the primary cellular sources of IL-4 and IL-13 are

CD4+ Th2 cells, basophils, mast cells, eosinophils,

natural killer T cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells (51,52).

These cytokines can promote collagen deposition, thus contributing

to the pathogenesis of scars. Additionally, IL-4 and IL-13 can

enhance POSTN expression in fibroblasts, thus facilitating scar

formation and progression (53).

Consistent with this, Nangole and Agak (54) showed that the plasma levels of IL-4

and IL-13 are significantly elevated in patients with keloids

compared with in healthy subjects, supporting the notion that

IL-4/IL-13 signaling and immune responses could serve key roles in

keloid formation.

Emerging evidence has suggested that IL-4 and/or

IL-13, two signatures of type 2 cytokines, can induce the

expression of POSTN in allergic diseases (35–37).

The present study demonstrated that IL-4 and/or IL-13 upregulated

POSTN in KFs, thus indicating that Th2 signals could upregulate

POSTN in keloids. In line with this result, a previous study showed

that POSTN is expressed in Th2-associated fibroblasts in atopic

dermatitis (55), further

confirming a crosstalk between Th2 immunity and keloid

pathogenesis. Notably, the IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathway was

significantly enriched in POSTN-related DEGs in KFs in the present

study. Additionally, POSTN knockdown could inhibit the expression

of IL-4R, a cytokine receptor for both IL-4 and IL-13, thus

suggesting that POSTN may positively regulate IL-4R expression in

KFs. Notably, IL-4R was necessary for IL-4/IL-13-induced POSTN

upregulation, underlying a positive feedback loop between POSTN and

Th2 signals in keloids. Previous studies have also revealed that

targeting IL-4Ra using dupilumab results in both atopic dermatitis

improvement and shrinkage of keloids (50,56).

Moreover, IL-4/IL-13 signaling is activated and the mRNA levels of

Th2-related factors have been shown to be increased in keloid

lesions (21,56). In addition, it has been reported

that keloids and other Th2-skewed diseases, including atopic

dermatitis (57) and asthma

(58), share several overlapped

clinical features. RNA-seq data have also linked keloids to a

Th2-skewed immune profile, thus indicating a close association

between keloid pathogenesis and Th2-related gene expression

signatures (32). Collectively,

IL-4 and/or IL-13 could induce POSTN expression, while, in turn,

the elevated POSTN expression could promote IL-4R expression, thus

suggesting a positive feedback loop and a novel mechanism that

could be involved in the pathogenesis of keloids. Due to the lack

of an effective mouse model for keloids, the regulatory effect of

IL-4/IL-13 on POSTN expression could not be investigated in

vivo. This represents a limitation of the present study.

Nonetheless, an in vivo model for keloid research should be

established in the future, potentially through an organoid-based

approach, to further explore the interaction between POSTN and

IL-4/IL-13 signaling in vivo.

In conclusion, the results of the present study

demonstrated that POSTN was upregulated by IL-4 and/or IL-13 in

KFs. Functionally, POSTN could promote inflammation in KFs without

affecting their proliferation. Furthermore, POSTN could positively

regulate IL-4R expression, which may be essential for

IL-4/IL-13-induced POSTN upregulation in KFs, thus suggesting that

a positive feedback loop between POSTN and Th2 signaling could be

involved in keloid development. However, further studies are needed

to verify the clinical relevance of POSTN in keloid pathogenesis,

and to assess the therapeutic potential of targeting POSTN and/or

Th2 signaling in keloid treatment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82103726 and

82203900), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research

Foundation (grant nos. 2023A1515010575 and 2025A1515010947), the

Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (grant nos.

JCYJ20210324110008023 and JCYJ20230807095809019), the Shenzhen

Sanming Project (grant no. SZSM202311029), the Shenzhen Key Medical

Discipline Construction Fund (grant no. SZXK040) and the Shenzhen

High-level Hospital Construction Fund and Peking University

Shenzhen Hospital Scientific Research Fund (grant no.

KYQD2024378).

Availability of data and materials

The sequencing data generated in the present study

may be found in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus under accession

number GSE307210 or at the following URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE307210.

The other data generated in the present study may be requested from

the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

BJ, FZ and CH contributed to the experimental

design, performance, data collection/analysis and manuscript

preparation. XL, KZ, JG and JW helped to perform in vitro

experiments. WZ, YZ and BY contributed to data analysis and

discussed the results. BY and CH supervised the study. WZ, BY and

CH contributed to funding acquisition. FZ and CH confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The studies involving human participants were

reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee from the Peking

University Shenzhen Hospital (protocol code 2022-070). Written

informed consent to participate in the study was provided by the

participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jiang Z, Chen Z, Xu Y, Li H, Li Y, Peng L,

Shan H, Liu X, Wu H, Wu L, et al: Low-frequency ultrasound

sensitive piezo1 channels regulate Keloid-related characteristics

of fibroblasts. Adv Sci (Weinh). 11:e23054892024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cohen AJ, Nikbakht N and Uitto J: Keloid

disorder: Genetic basis, gene expression profiles, and

immunological modulation of the fibrotic processes in the skin.

Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 15:a0412452023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wang ZC, Zhao WY, Cao Y, Liu YQ, Sun Q,

Shi P, Cai JQ, Shen XZ and Tan WQ: The roles of inflammation in

keloid and hypertrophic scars. Front Immunol. 11:6031872020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zhang M, Chen H, Qian H and Wang C:

Characterization of the skin keloid microenvironment. Cell Commun

Signal. 21:2072023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Delaleu J, Charvet E and Petit A: Keloid

disease: Review with clinical atlas. Part I: Definitions, history,

epidemiology, clinics and diagnosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol.

150:3–15. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hawash AA, Ingrasci G, Nouri K and

Yosipovitch G: Pruritus in keloid scars: Mechanisms and treatments.

Acta Derm Venereol. 101:adv005822021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Walsh LA, Wu E, Pontes D, Kwan KR, Poondru

S, Miller CH and Kundu RV: Keloid treatments: An evidence-based

systematic review of recent advances. Syst Rev. 12:422023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Naik PP: Novel targets and therapies for

keloid. Clin Exp Dermatol. 47:507–515. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ekstein SF, Wyles SP, Moran SL and Meves

A: Keloids: A review of therapeutic management. Int J Dermatol.

60:661–671. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kim J, Kim B, Kim SM, Yang CE, Song SY,

Lee WJ and Lee JH: Hypoxia-induced Epithelial-To-Mesenchymal

transition mediates fibroblast abnormalities via ERK activation in

cutaneous wound healing. Int J Mol Sci. 20:25462019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kang Y, Roh MR, Rajadurai S, Rajadurai A,

Kumar R, Njauw CN, Zheng Z and Tsao H: Hypoxia and HIF-1α regulate

collagen production in keloids. J Invest Dermatol. 140:2157–2165.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Guo C, Liang L, Zheng J, Xie Y, Qiu X, Tan

G, Huang J and Wang L: UCHL1 aggravates skin fibrosis through an

IGF-1-induced Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α pathway in keloid. FASEB J.

37:e230152023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gu JJ, Deng CC, Feng QL, Liu J, Zhu DH,

Cheng Q, Rong Z and Yang B: Relief of extracellular matrix

deposition repression by downregulation of IRF1-mediated TWEAK/Fn14

signaling in keloids. J Invest Dermatol. 143:1208–1219. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wang Y, Chen Y, Wu J and Shi X: BMP1

Promotes keloid by inducing fibroblast inflammation and

fibrogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 125:e306092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mao J, Chen L, Qian S, Wang Y, Zhao B,

Zhao Q, Lu B, Mao X, Zhai P, Zhang Y, et al: Transcriptome network

analysis of inflammation and fibrosis in keloids. J Dermatol Sci.

113:62–73. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Wang X, Wang X, Liu Z, Liu L, Zhang J,

Jiang D and Huang G: Identification of inflammation-related

biomarkers in keloids. Front Immunol. 15:13515132024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lee SY, Lee AR, Choi JW, Lee CR, Cho KH,

Lee JH and Cho ML: IL-17 induces autophagy dysfunction to promote

inflammatory cell death and fibrosis in keloid fibroblasts via the

STAT3 and HIF-1α dependent signaling pathways. Front Immunol.

13:8887192022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lee SY, Kim EK, Seo HB, Choi JW, Yoo JH,

Jung KA, Kim DS, Yang SC, Moon SJ, Lee JH and Cho ML: IL-17 induced

stromal Cell-derived Factor-1 and profibrotic factor in

Keloid-derived skin fibroblasts via the STAT3 pathway.

Inflammation. 43:664–672. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Shin JU, Kim SH, Kim H, Noh JY, Jin S,

Park CO, Lee WJ, Lee DW, Lee JH and Lee KH: TSLP Is a potential

initiator of collagen synthesis and an activator of CXCR4/SDF-1

axis in keloid pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 136:507–515. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chen Z, Gao Z, Xia L, Wang X, Lu L and Wu

X: Dysregulation of DPP4-CXCL12 balance by TGF-β1/SMAD pathway

promotes CXCR4+ inflammatory cell infiltration in keloid scars. J

Inflamm Res. 14:4169–4180. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nguyen JK, Austin E, Huang A, Mamalis A

and Jagdeo J: The IL-4/IL-13 axis in skin fibrosis and scarring:

Mechanistic concepts and therapeutic targets. Arch Dermatol Res.

312:81–92. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Smith JC, Boone BE, Opalenik SR, Williams

SM and Russell SB: Gene profiling of keloid fibroblasts shows

altered expression in multiple fibrosis-associated pathways. J

Invest Dermatol. 128:1298–1310. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hahn JM, Glaser K, McFarland KL, Aronow

BJ, Boyce ST and Supp DM: Keloid-derived keratinocytes exhibit an

abnormal gene expression profile consistent with a distinct causal

role in keloid pathology. Wound Repair Regen. 21:530–544. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Smyth GK: Limma: Linear models for

microarray data. Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions

using R and Bioconductor. Springer; New York, NY: pp. 397–420.

2005, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW,

Shi W and Smyth GK: Limma powers differential expression analyses

for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:e472015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank

MH, He Y and Xia R: TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for

interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant.

13:1194–1202. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Williams R and Thornton MJ: Isolation of

different dermal fibroblast populations from the skin and the hair

follicle. Methods Mol Biol. 2154:13–22. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Huang C, Zhong W, Ren X, Huang X, Li Z,

Chen C, Jiang B, Chen Z, Jian X, Yang L, et al: MiR-193b-3p-ERBB4

axis regulates psoriasis pathogenesis via modulating cellular

proliferation and inflammatory-mediator production of

keratinocytes. Cell Death Dis. 12:9632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang C, Lv X, Chen P, Liu J, He C, Chen

L, Wang H, Moness ML, Dong J, Rueda BR, et al: Human papillomavirus

targets the YAP1-LATS2 feedback loop to drive cervical cancer

development. Oncogene. 41:3761–3777. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Huang C, Li W, Shen C, Jiang B, Zhang K,

Li X, Zhong W, Li Z, Chen Z, Chen C, et al: YAP1 facilitates the

pathogenesis of psoriasis via modulating keratinocyte proliferation

and inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 16:1862025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wu J, Del Duca E, Espino M, Gontzes A,

Cueto I, Zhang N, Estrada YD, Pavel AB, Krueger JG and

Guttman-Yassky E: RNA sequencing keloid transcriptome associates

keloids with Th2, Th1, Th17/Th22, and JAK3-skewing. Front Immunol.

11:5977412020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Xu H, Wang Z, Yang H, Zhu J and Hu Z:

Bioinformatics analysis and identification of dysregulated POSTN in

the pathogenesis of keloid. Int Wound J. 20:1700–1711. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nangole FW, Ouyang K, Anzala O, Ogengo J

and Agak GW: Multiple cytokines elevated in patients with keloids:

Is it an indication of Auto-inflammatory disease? J Inflamm Res.

14:2465–2470. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Masuoka M, Shiraishi H, Ohta S, Suzuki S,

Arima K, Aoki S, Toda S, Inagaki N, Kurihara Y, Hayashida S, et al:

Periostin promotes chronic allergic inflammation in response to Th2

cytokines. J Clin Invest. 122:2590–2600. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Arima K, Ohta S, Takagi A, Shiraishi H,

Masuoka M, Ontsuka K, Suto H, Suzuki S, Yamamoto K, Ogawa M, et al:

Periostin contributes to epidermal hyperplasia in psoriasis common

to atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 64:41–48. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Mitamura Y, Nunomura S, Nanri Y, Ogawa M,

Yoshihara T, Masuoka M, Tsuji G, Nakahara T, Hashimoto-Hachiya A,

Conway SJ, et al: The IL-13/periostin/IL-24 pathway causes

epidermal barrier dysfunction in allergic skin inflammation.

Allergy. 73:1881–1891. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Kou K, Okawa T, Yamaguchi Y, Ono J, Inoue

Y, Kohno M, Matsukura S, Kambara T, Ohta S, Izuhara K and Aihara M:

Periostin levels correlate with disease severity and chronicity in

patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 171:283–291. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Akar-Ghibril N, Casale T, Custovic A and

Phipatanakul W: Allergic endotypes and phenotypes of asthma. J

Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 8:429–440. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Frech FS, Hernandez L, Urbonas R, Zaken

GA, Dreyfuss I and Nouri K: Hypertrophic scars and keloids:

Advances in treatment and review of established therapies. Am J

Clin Dermatol. 24:225–245. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Tian J, Liu X, Zhu D and Li J: Periostin

regulates the activity of keloid fibroblasts by activating the

JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Heliyon. 10:e388212024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yin SL, Qin ZL and Yang X: Role of

periostin in skin wound healing and pathologic scar formation. Chin

Med J (Engl). 133:2236–2238. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sonnenberg-Riethmacher E, Miehe M and

Riethmacher D: Periostin in allergy and inflammation. Front

Immunol. 12:7221702021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Crawford J, Nygard K, Gan BS and O'Gorman

DB: Wound healing and fibrosis: A contrasting role for periostin in

skin and the oral mucosa. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol.

318:C1065–C1077. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Chen L, Su Y, Yin B, Li S, Cheng X, He Y

and Jia C: LARP6 regulates keloid fibroblast proliferation,

invasion, and ability to synthesize collagen. J Invest Dermatol.

142:2395–2405. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Yin Q, Wolkerstorfer A, Lapid O, Niessen

FB, Van Zuijlen PPM and Gibbs S: The JAK-STAT pathway in keloid

pathogenesis: A systematic review with qualitative synthesis. Exp

Dermatol. 32:588–598. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Limandjaja GC, van den Broek LJ, Waaijman

T, Breetveld M, Monstrey S, Scheper RJ, Niessen FB and Gibbs S:

Reconstructed human keloid models show heterogeneity within keloid

scars. Arch Dermatol Res. 310:815–826. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Tanaka R, Umeyama Y, Hagiwara H,

Ito-Hirano R, Fujimura S, Mizuno H and Ogawa R: Keloid patients

have higher peripheral blood endothelial progenitor cell counts and

CD34+ cells with normal vasculogenic and angiogenic

function that overexpress vascular endothelial growth factor and

interleukin-8. Int J Dermatol. 58:1398–1405. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Liao WT, Yu HS, Arbiser JL, Hong CH,

Govindarajan B, Chai CY, Shan WJ, Lin YF, Chen GS and Lee CH:

Enhanced MCP-1 release by keloid CD14+ cells augments fibroblast

proliferation: Role of MCP-1 and Akt pathway in keloids. Exp

Dermatol. 19:e142–e150. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Diaz A, Tan K, He H, Xu H, Cueto I, Pavel

AB, Krueger JG and Guttman-Yassky E: Keloid lesions show increased

IL-4/IL-13 signaling and respond to Th2-targeting dupilumab

therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 34:e161–e164. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Lee CC, Tsai CH, Chen CH, Yeh YC, Chung WH

and Chen CB: An updated review of the immunological mechanisms of

keloid scars. Front Immunol. 14:11176302023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Junttila IS: Tuning the cytokine

responses: An update on interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 receptor

complexes. Front Immunol. 9:8882018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang D, Li B and Zhao M: Therapeutic

strategies by regulating interleukin family to suppress

inflammation in hypertrophic scar and keloid. Front Pharmacol.

12:6677632021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Nangole FW and Agak GW: Keloid

pathophysiology: Fibroblast or inflammatory disorders? JPRAS Open.

22:44–54. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

He H, Suryawanshi H, Morozov P,

Gay-Mimbrera J, Del Duca E, Kim HJ, Kameyama N, Estrada Y, Der E,

Krueger JG, et al: Single-cell transcriptome analysis of human skin

identifies novel fibroblast subpopulation and enrichment of immune

subsets in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol.

145:1615–1628. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Guttman-Yassky E, Bissonnette R, Ungar B,

Suárez-Fariñas M, Ardeleanu M, Esaki H, Suprun M, Estrada Y, Xu H,

Peng X, et al: Dupilumab progressively improves systemic and

cutaneous abnormalities in patients with atopic dermatitis. J

Allergy Clin Immunol. 143:155–172. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Lu YY, Lu CC, Yu WW, Zhang L, Wang QR,

Zhang CL and Wu CH: Keloid risk in patients with atopic dermatitis:

A nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. BMJ Open.

8:e0228652018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Hajdarbegovic E, Bloem A, Balak D, Thio B

and Nijsten T: The association between atopic disorders and

keloids: A Case-control study. Indian J Dermatol. 60:6352015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|