Introduction

Various musculoskeletal disorders develop with age.

In bones, the progressive increase in receptor activator of NF-κB

ligand and sclerostin levels (1,2), as

well as a decline in normal type I collagen (3), lead to a reduction in bone mass and

density that ultimately results in osteoporosis (4). In cartilage, an increase in matrix

metalloproteinases and disintegrin and metalloproteinase with

thrombospondin motifs, coupled with a reduction in normal type II

collagen, contributes to cartilage degeneration, leading to

osteoarthritis (5,6). In peripheral nerves, axonal

regenerative capacity is reported to decline with age; however, the

pathology in peripheral nerves remains to be elucidated (7).

Repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor

(REST) is a transcriptional factor that regulates neuron-specific

gene expression in the nervous system (8). Our previous studies demonstrated that

REST expression increases with age in peripheral nerves, leading to

a decline in axonal regenerative capacity (9,10).

However, the role of REST in peripheral nerve axonal regeneration

with age remains to be elucidated. Nuclear transport mechanisms are

essential for transcription factors to perform their functions

within cells (11). Under healthy

aging, REST is transported to the nucleus in brain cells, where it

provides neuroprotection against oxidative stress and apoptosis

(12,13). On the other hand, oxidative stress

has been shown to induce abnormal modifications in nuclear proteins

such as histones, leading to immune responses associated with

disease (14). Moreover, REST is

not transported to the nucleus in neurodegenerative diseases such

as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease (12,13).

Thus, understanding the role of REST in peripheral nerves requires

elucidation of its nuclear transport mechanism.

Several studies have reported that hydrogen

(H2) has neuroprotective effects. In mice, oral

administration of H2-rich water (HRW) suppresses

oxidative stress markers and provides protective effects against

cognitive impairment (15). A

previous study using a cerebral ischemia mouse model reported that

intraperitoneal administration of HRW promoted neuronal recovery

through autophagy (16).

Furthermore, using a diabetic rat model with peripheral neuropathy,

intraperitoneal administration of HRW improved axonal degeneration

(17). However, the mechanism of

neuroprotective effects of H2 administration on

peripheral nerves remains to be elucidated. This study investigated

the effects of H2 administration on the decline in

axonal regenerative capacity with aging. Additionally, to elucidate

the pathology of age-related decline in axonal regeneration, the

molecular mechanisms involved in REST nuclear transport were

analyzed.

Materials and methods

Animals

This study was approved by the Animal Care Committee

of Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan (2-1-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku,

Tokyo, 113-8421, Japan; Registration No. 1555; Approval No.

2024183, Date of Approval: March 12th, 2024).

Eighteen male C57BL/6J mice (Young group: 8-week-old

mice, n=6; Aged group: 70-week-old mice, n=6; Aged + H2

group: 70-week-old mice, n=6) for quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (qPCR) and western blotting, and 15 male C57BL6J mice

(Young group: 8-week-old mice, n=5; Aged group: 70-week-old mice,

n=5; Aged + H2 group: 70-week-old mice, n=5) for

immunofluorescence staining were purchased from JAPN SLC, Inc.

(Shizuoka, Japan). The body weight of the mice at the start of the

experiment was 40.0±6.4 g. Mice were housed in sterile cages with

five animals per cage, under controlled conditions of 22±2°C,

40–60% humidity, and a 12-h light/dark cycle. The mice were given

water that was CRF-1 gamma-ray-irradiated (15 kGy) (Oriental Yeast

Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) ad libitum. As estrogen levels are

known to influence peripheral neuropathy and naturally decrease

with age, male mice with less estrogen fluctuations and

susceptibility to estrogen were used in this study. The health

status and behavior of the animals were monitored daily throughout

the experiment period. Humane endpoints were defined as a loss of

20% of body weight, difficulty breathing, coughing, wheezing,

severe diarrhea, vomiting, flaccid or spastic paralysis,

convulsions, coupled with body temperature significantly below

normal, and continuously assessed to determine whether animals

should be euthanized before the scheduled end of the experiment. No

animals reached these humane endpoints during the study.

Hydrogen treatment

H2-containing physiological saline was

prepared using the H2 gas generator Suilive®

SS-150 (SUISO JAPAN Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The Aged +

H2 group received daily intraperitoneal injections of

H2-containing physiological saline (10 ml/kg,

H2 concentration: 800 ppb) for 2 weeks. The Aged group

received an equivalent volume of normal saline (10 ml/kg).

Analysis of REST and GAP43 expression

in young and aged mice

The Young group (n=6), the Aged group (n=6), and the

Aged + H2 group (n=6) were sacrificed by cervical

dislocation and their sciatic nerves (SN) were collected. The

expression levels of REST and growth-associated protein 43 (GAP43),

a neuronal protein known for its important role in axon

regeneration, in SN were measured by qPCR, western blotting, and

immunofluorescence staining and compared among the three

groups.

Cell culture

Mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 (Cell

line service, Eppelheim, Germany) was cultured in a humidified

incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The culture medium consisted of

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F-12 (Sigma-Aldrich),

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U/ml penicillin.

H2-containing culture medium was prepared using

Suilive® SS-150. H2 concentration was

confirmed to be 800 ppb at the start of administration and 500 ppb

after 2 h according to our preliminary experience (data not shown).

Based on the results of these preliminary experiments, the cell

culture time in the H2-containing culture medium was set

to 2 h.

Construction of REST-overexpressed

cells

Using cultured cell lines, REST-overexpressed

(REST-OE) cells were constructed (REST-OE group). REST was

overexpressed using a lentiviral vector (VectorBuilder Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA; vector ID: VB900006-3284rup), while a mock

plasmid served as the negative control (Control group). The

plasmids were amplified in Escherichia coli DH5α, and plasmid DNA

was purified from the amplified lentiviral vectors using the

QUIAGEN® Plasmid Maxi kit. To make REST-OE cells, cells

were transfected with the REST plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000

(Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. REST-OE cells were cultured in

H2-containing medium (H2 concentration: 800

ppb) for 2 h in the cells of the REST-OE + H2 group.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from SN of animal models and

from cultured cell lines using in vitro models with the

RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan), following the

manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized

using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Shiga,

Japan). Next, qPCR was performed with SYBR Green real-time PCR

assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the ΔΔCT method. The

expression levels of targets (REST and GAP43) were normalized to

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). qPCR reactions

were performed in triplicate, and the ΔΔCt method was used for

relative quantification (18). The

primer sequences used are listed in Table I.

| Table I.Primer sequences used for

quantitative PCR in the present study. |

Table I.

Primer sequences used for

quantitative PCR in the present study.

| Gene | Forward primer

sequences (5′-3′) | Reverse primer

sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|

| Rest |

ACCTGCAGCAAGTGCAACTA |

CCGCATGTGTCGCGTTAGA |

| Gap43 |

AAGGCAGGGGAAGATACCAC |

TTGTTCAATCTTTTGGTCCTCAT |

| Gapdh |

TGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCTG |

TTGCTGTTGAAGTCGCAGG |

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from SN of animal models and

from cultured cell lines using 1 × radio immunoprecipitation assay

(RIPA) buffer. Equal amounts of protein were loaded for each sample

as determined by BCA assay and separated by sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and

transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes by

Trans-Blot Turbo system (BIORAD, CA, USA). Non-specific binding

sites were blocked with PVDF Blocking Reagent (Toyobo Co. Ltd.,

Osaka, Japan) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then

washed three times with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween

20 (TBST), 10 min per wash. Subsequently, membranes were incubated

overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in Solution 1

(Toyobo Co. Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Although each target protein and its corresponding loading control

were detected on separate membranes, equal amounts of protein (20

µg) were loaded per lane as determined by BCA assay, and all

membranes were quantified based on relative band intensities using

standardized loading across samples.

The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit

polyclonal anti-REST (1:1,000, 22242-1-AP; ProteinTech), rabbit

polyclonal anti-GAP43 (1:1,000, 16971-1-AP; ProteinTech), rabbit

polyclonal anti-PRICKLE1 (RILP) (1:1,000, 22589-1-AP; ProteinTech),

rabbit monoclonal anti-Huntingtin (1:5,000, ab109115; Abcam),

rabbit monoclonal anti-DCTN1/p150Glued (1:1,000, ab246505; Abcam),

rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3 (1:1,000, 14600-1-AP; ProteinTech),

mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (1:2,000, sc-32233; Santa Cruz, CA,

USA), and rabbit polyclonal anti-Lamin B1 (1:5,000, 12987-1-AP;

ProteinTech).

After incubation, membranes were washed with TBST

and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 2 h at room

temperature. Following additional washes, signals were detected

using the Amersham Imager 680 system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences,

IL, USA). Image Lab 3.0 software was used to measure the relative

optical density of the protein bands. GAPDH was used as a loading

control for the total cell and cytoplasmic fractions, and Lamin B1

as a loading control for the nuclear fractions.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to assess

the expression of REST and GAP43 in both animal models and cultured

cell lines. SN was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature

for 72 h and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections

were prepared by slicing cutting the harvested SN into 3 µm-thick

sections. Samples were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen

retrieval by autoclaving at 121°C for 10 min. Cell lines were

cultured using the Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ II Chamber

Slide™ System to create three group. Then, the cultured

medium was discarded, and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room

temperature for 15 min. To suppress autofluorescence sections were

treated with True View™ (SP-8400, Vector, CA, USA),

followed by blocking in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 2% bovine

serum albumin (BSA) (A2153, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) for 30 min.

Sections were then incubated with primary antibodies against the

target proteins at 4°C for 15 h. After washing with TBST, a goat

anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (A11001,

Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as the secondary antibody. A

rabbit IgG monoclonal antibody was used as a negative control.

Fluorescence intensity was visualized using a fluorescence imaging

microscope (Leica, TCSSP5, Wetzlar, Germany) in photon-counting

mode. The primary antibodies were rabbit polyclonal anti-REST

(1:100, 22242-1-AP, ProteinTech, IL, USA), and rabbit polyclonal

anti-GAP43 (1:100, 16971-1-AP, ProteinTech) in this study.

Fluorescence intensity was measured at 10 randomly

selected sites within the perikaryon in the region of interest

(ROI) showing fluorescence emission. The mean fluorescence

intensity was then calculated. Fluorescence levels detected by each

antibody were compared among the groups: for the in vivo

experiment (Young group, Aged group, Aged + H2 group)

and for the in vitro experiment (Control group, REST-OE

group, and REST-OE + H2 group).

Isolation of cytoplasmic and nuclear

fractions from REST-regulated cells

To demonstrate that REST, functioning as a

transcriptional regulator, is transported to the nucleus from the

cytoplasm, we used NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic

Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the

manufacturer's instructions. Using these fractions, REST and the

proteins reported to be involved in REST nuclear transport,

including RILP, Huntingtin, and DCTN1/p150Glued, and LC3

were quantified by western blotting.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

(SD). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA), followed by Sidak's multiple comparisons test for

pairwise group comparisons, with Prism 7 software (GraphPad

Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A P-value of less than 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

Results

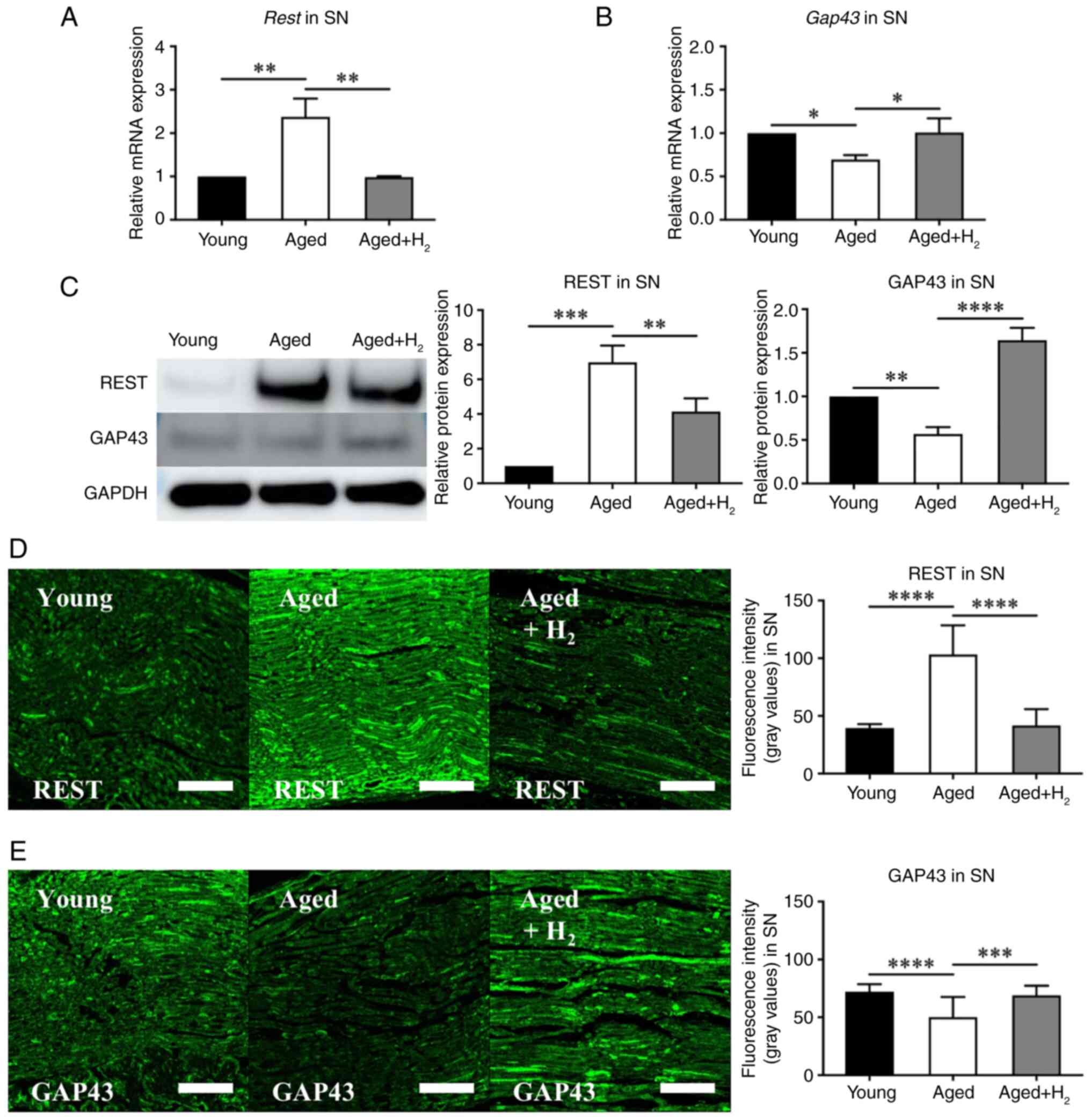

REST expression and GAP43 in SN

To examine differences in the expression of REST and

GAP43 among the Young group, the Aged group, and the Aged +

H2 group, their expression in SN were quantified by

qPCR, western blotting, and immunofluorescence staining.

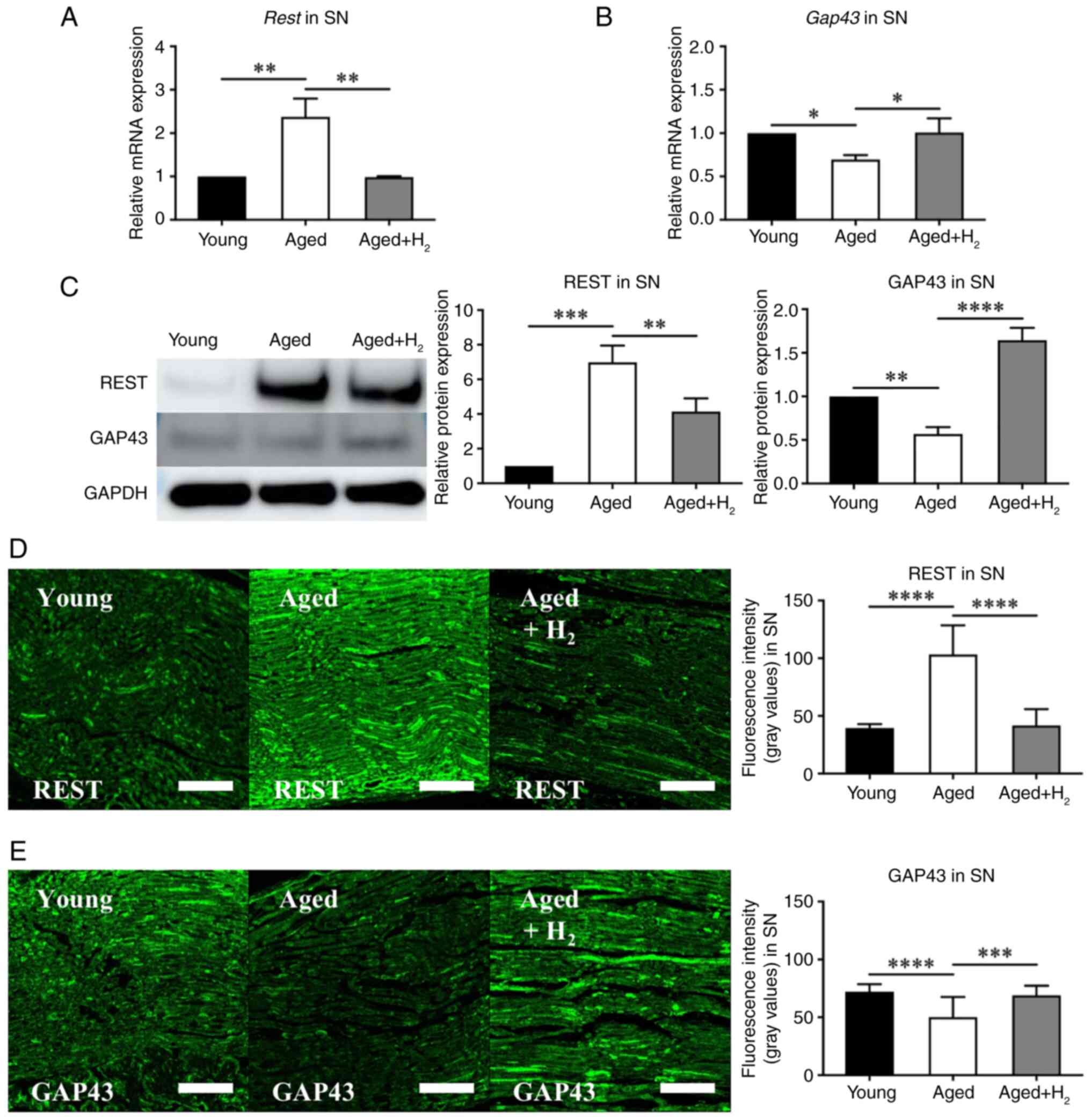

qPCR analysis revealed a significant upregulation of

REST in the Aged group compared with the Young group (Young group:

1.00±0.00-fold; Aged group: 2.37±0.35-fold, P=0.0014), whereas it

was significantly decreased in the Aged + H2 group

compared with the Aged group (Aged group: 2.37±0.35-fold; Aged +

H2 group: 0.98±0.02-fold, P=0.0013) (Fig. 1A). GAP43 expression in SN was

significantly decreased in the Aged group compared with the Young

group (Young group: 1.00±0.00-fold; Aged group: 0.70±0.04-fold,

P=0.0274), whereas it was significantly increased in the Aged +

H2 group compared with the Aged group (Aged group:

0.70±0.04-fold, P=0.0274; Aged + H2 group:

1.00±0.13-fold, P=0.0249) (Fig.

1B).

| Figure 1.REST and GAP43 expression in SN of

the young, aged and aged + H2 groups. The aged group was

compared with the young group, and the aged + H2 group

was compared with the aged group. The graphs show the

quantification of relative protein and mRNA abundance. Mean ± SD,

n=6 mice per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). (A) qPCR analysis of Rest

expression. (B) qPCR analysis of Gap43 expression. (C)

Western blot analysis of REST and GAP43 expression. (D)

Histochemical assessment of REST expression by immunofluorescence

staining. Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) Histochemical assessment of GAP43

expression by immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar, 100 µm.

GAP43, growth-associated protein 43; H2, hydrogen; qPCR,

quantitative PCR; REST, repressor element 1 silencing transcription

factor; SN, sciatic nerves. |

Western blotting further supported these results.

REST expression was markedly increased in the Aged group compared

with the Young group (Young group: 1.00±0.00-fold; Aged group:

6.98±0.79-fold, P=0.0001), whereas it was significantly decreased

in the Aged + H2 group compared with the Aged group

(Aged group: 6.98±0.79-fold; Aged + H2 group:

4.14±0.62-fold, P=0.0082) (Fig.

1C). GAP43 expression in SN was significantly decreased in the

Aged group compared with the Young group (Young group:

1.00±0.00-fold; Aged group: 0.57±0.06-fold, P=0.0040), whereas it

was significantly increased in the Aged + H2 group

compared with the Aged group (Aged group: 0.57±0.06-fold; Aged +

H2 group: 1.64±0.12-fold, P<0.0001) (Fig. 1C).

Immunofluorescence staining revealed that the

fluorescence intensity of REST in SN was significantly increased in

the Aged group compared with the Young group (Young group:

39.57±3.19; Aged group: 103.30±6.48, P<0.0001), whereas it was

significantly decreased in the Aged + H2 group compared

with the Aged group (Aged group: 103.30±6.48; Aged + H2

group: 41.75±3.64, P<0.0001) (Fig.

1D). On the other hand, the fluorescence intensity of GAP43 in

SN was significantly decreased in the Aged group compared with the

Young group (Young group: 72.15±6.26; Aged group: 50.17±4.51,

P<0.0001), whereas it was significantly increased in the Aged +

H2 group compared with the Aged group (Aged group:

50.17±4.51; Aged + H2 group: 68.96±2.17, P=0.0002)

(Fig. 1E).

These results suggest that REST is upregulated with

aging and inhibits axonal regeneration capacity; however,

H2 may have the potential to recover this reduced

capacity for axonal regeneration in mice.

REST expression and GAP43 expression

in REST-OE cells

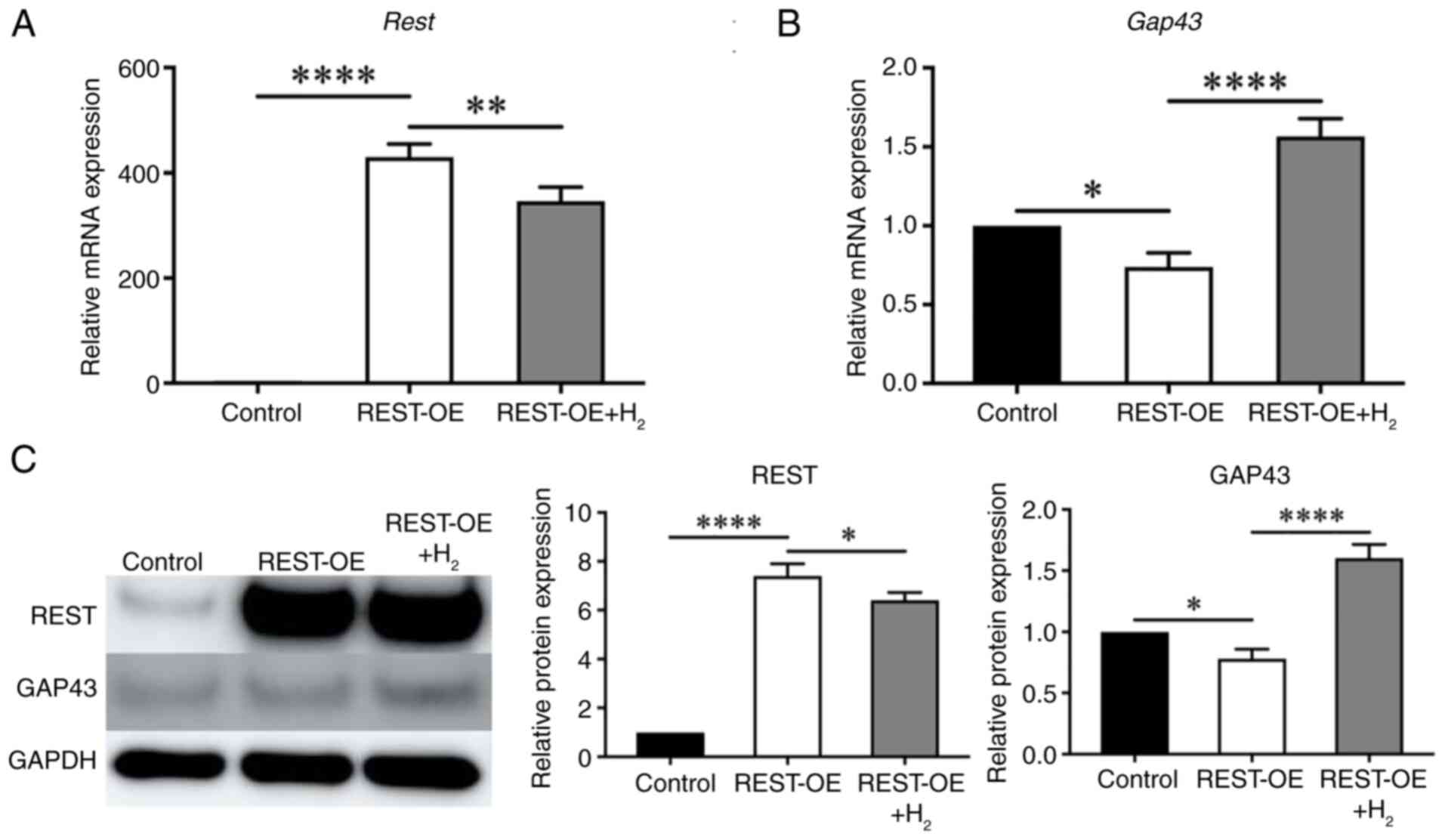

To verify whether the results obtained in SN can be

reproduced in cultured cells, REST-OE cells were constructed and

compared among the Control, REST-OE, and REST-OE + H2

groups.

qPCR showed that REST expression was markedly

increased in the REST-OE group compared with the Control group

(Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 430.0±20.51-fold,

P<0.0001), whereas it was significantly decreased in the REST-OE

+ H2 group compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE

group: 430.0±20.51-fold; REST-OE + H2 group:

346.6±21.95-fold, P=0.0059) (Fig.

2A). On the other hand, GAP43 expression was significantly

decreased in the REST-OE group compared with the Control group

(Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 0.74±0.07-fold,

P=0.0248), whereas it was significantly increased in the REST-OE +

H2 group compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group:

0.74±0.07-fold; REST-OE + H2 group: 1.60±0.09-fold,

1.57±0.09-fold, P<0.0001) (Fig.

2B).

At the protein level, REST expression followed a

similar pattern. REST expression was significantly increased in the

REST-OE group compared with the Control group (Control group:

1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 7.40±0.41-fold, P<0.0001),

whereas it was significantly decreased in the REST-OE +

H2 group compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group:

7.40±0.41-fold; REST-OE + H2 group: 6.40±0.26-fold,

P=0.0240) (Fig. 2C). On the other

hand, GAP43 expression was significantly decreased in the REST-OE

group compared with the Control group (Control group:

1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 0.78±0.06-fold, P=0.0409), whereas

it was significantly increased in the REST-OE + H2 group

compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group: 0.78±0.06-fold;

REST-OE + H2 group: 1.60±0.09-fold, P<0.0001)

(Fig. 2C).

These results are consistent with those observed in

mice, suggesting that these cells are a suitable model for

evaluating changes in SN of animal models.

Differences in the localization of

REST expression between the cytoplasm and the nucleus

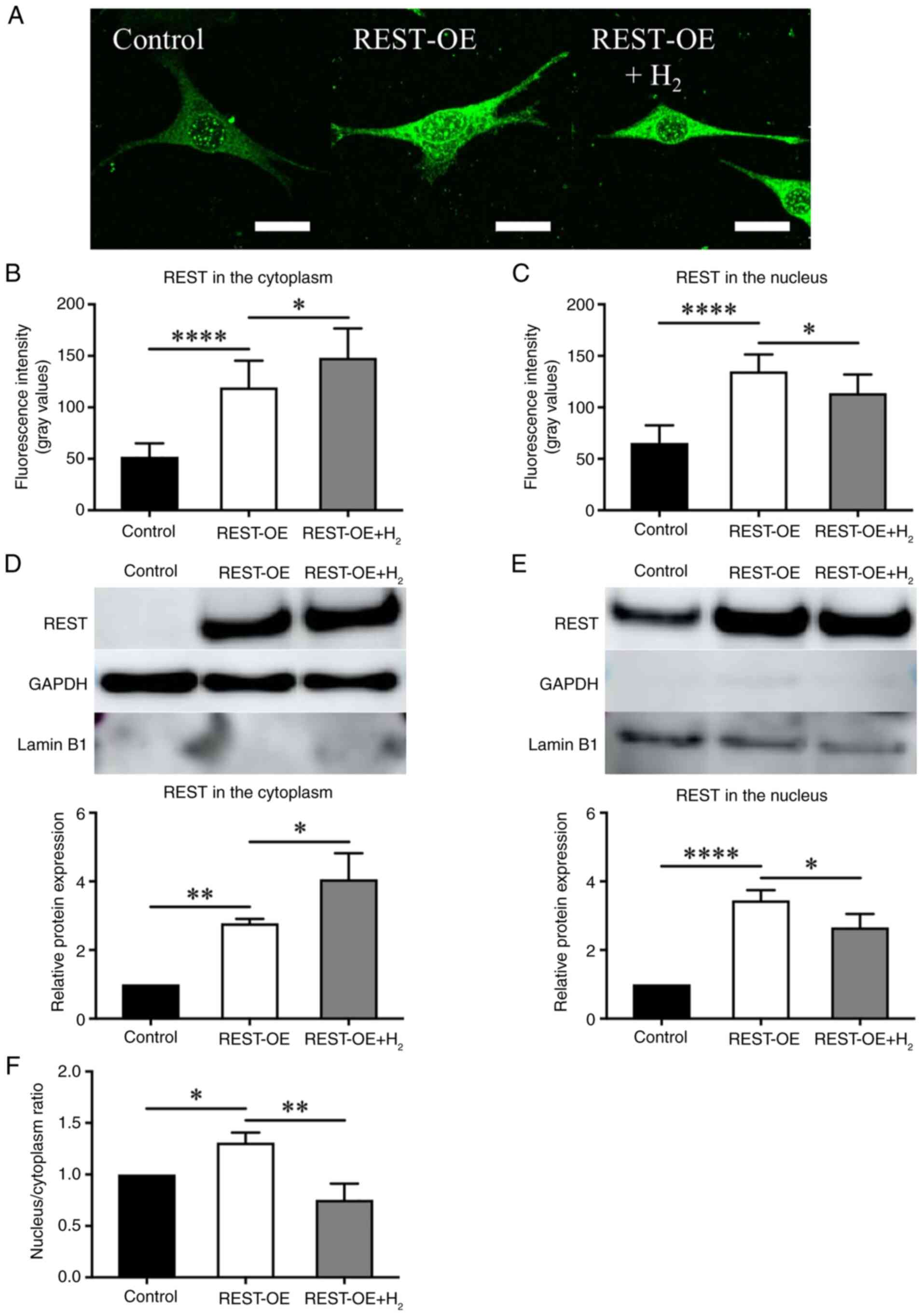

H2 reduces the intracellular expression

of REST (Fig. 2A and C);

therefore, to examine differences in the localization of REST

expression, in vitro cell lines were separated into

cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, and REST expression was

investigated by immunofluorescence staining and western

blotting.

Immunofluorescence staining revealed that the

fluorescence intensity of REST in the cytoplasm was significantly

elevated in the REST-OE group compared to controls (52.01±12.40 in

Control vs. 119.33±24.81 in REST-OE, P<0.0001), and further

increased following H2 treatment (119.33±24.81 in

REST-OE vs. 148.08±27.25 in REST-OE + H2,

P=0.0226) (Fig. 3A and B).

On the other hand, the fluorescence intensity of REST in the

nucleus was significantly increased in the REST-OE group compared

with the Control group (Control group: 65.39±16.39; REST-OE group:

135.03±15.61, P<0.0001), whereas it was significantly decreased

in the REST-OE + H2 group compared with the REST-OE

group (REST-OE group: 135.03±15.61; REST-OE + H2 group:

113.86±17.26, P=0.0144) (Fig. 3A and

C).

Western blotting supported these findings. REST

protein levels in the cytoplasm were significantly increased in the

REST-OE group compared to controls (1.00±0.00-fold in Control vs.

2.78±0.11-fold in REST-OE, P=0.0053), and further increased

with H2 treatment (2.78±0.11-fold in REST-OE vs.

4.07±0.62-fold in REST-OE + H2, P=0.0238)

(Fig. 3D). On the other hand, REST

expression in the nucleus was significantly increased in the

REST-OE group compared with the Control group (Control group:

1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 3.45±0.24-fold, P<0.0001),

whereas it was decreased in the REST-OE + H2 group

compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group: 3.45±0.24-fold;

REST-OE + H2 group: 2.66±0.32-fold, P=0.0281)

(Fig. 3E). Furthermore, the ratio

of REST expression in the nucleus to that in the cytoplasm was

calculated. As a result, the REST-OE group showed a significant

increase compared to controls (Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold;

REST-OE group: 1.31±0.08-fold, P=0.0355) (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the REST-OE +

H2 group showed a significant decrease compared to the

REST-OE group (REST-OE group: 1.31±0.08-fold; REST-OE +

H2 group: 0.75±0.13-fold, P=0.0021) (Fig. 3F).

Although H2 reduces REST expression in

the whole cell (Fig. 2A and C), it

increases REST expression in the cytoplasm and decreases it in the

nucleus in REST-OE cells. This suggests that H2 affects

the degradation within the cytoplasm and nuclear transport of

REST.

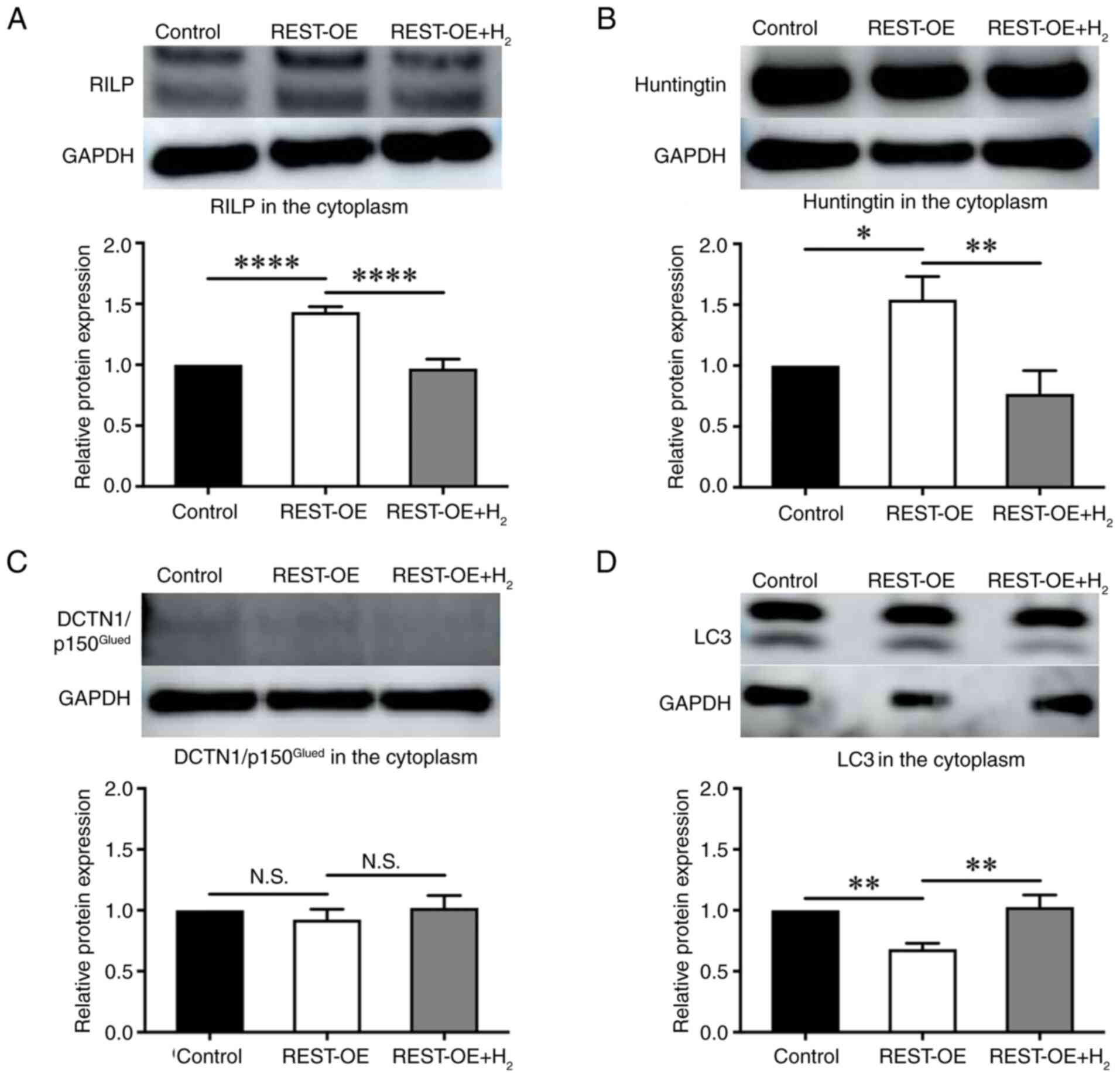

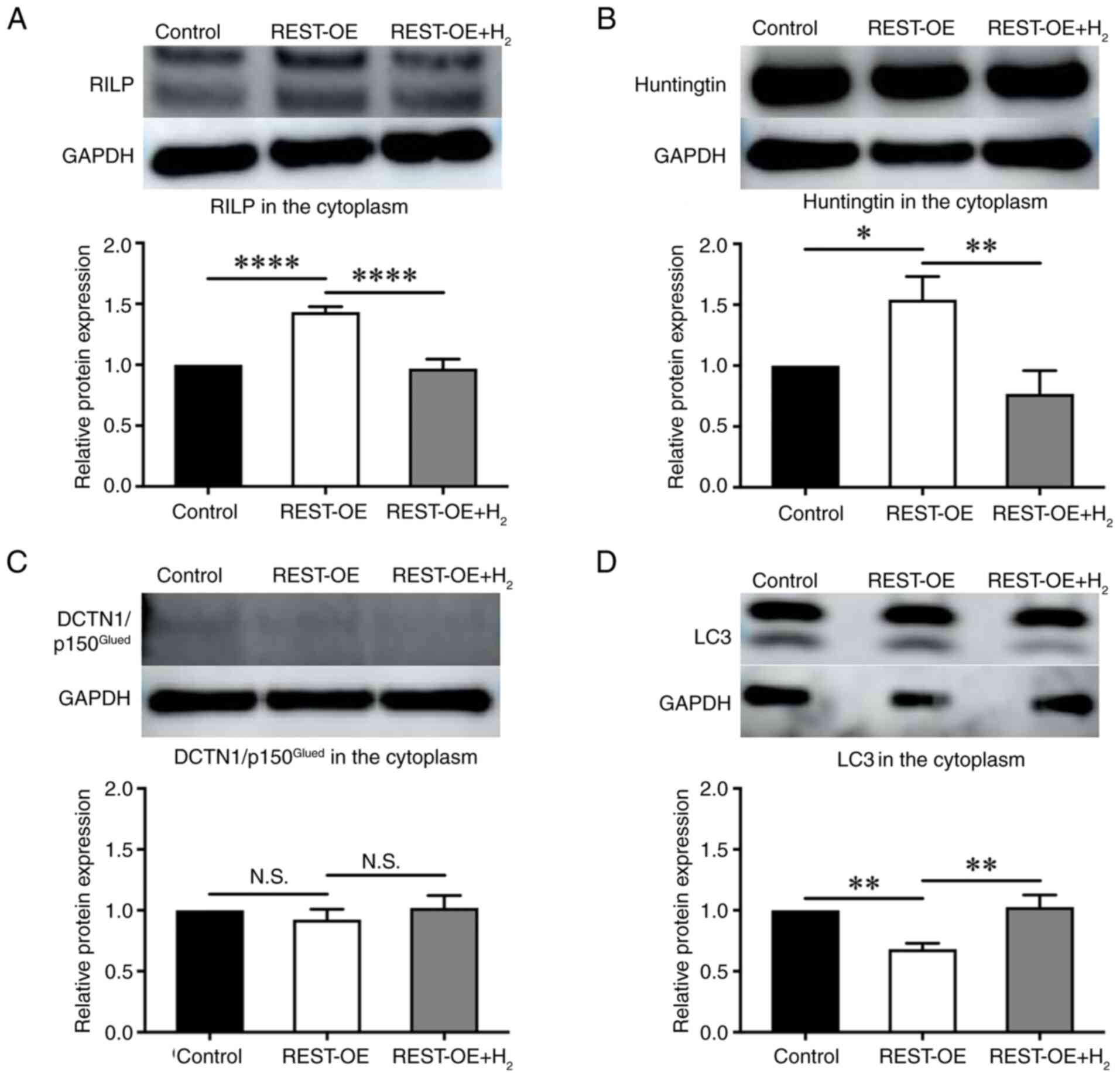

REST nuclear transport proteins and

autophagy-related protein LC3 in the cytoplasm and nucleus of

REST-OE cells

REST in the cytoplasm is either degraded by

autophagy or transported into the nucleus. To investigate these

processes, REST nuclear transport proteins, such as

REST-interacting LIM domain protein (RILP), Huntingtin, and

DCTN1/p150Glued, and the autophagy-related protein,

light chain 3 protein (LC3), were quantified by western

blotting.

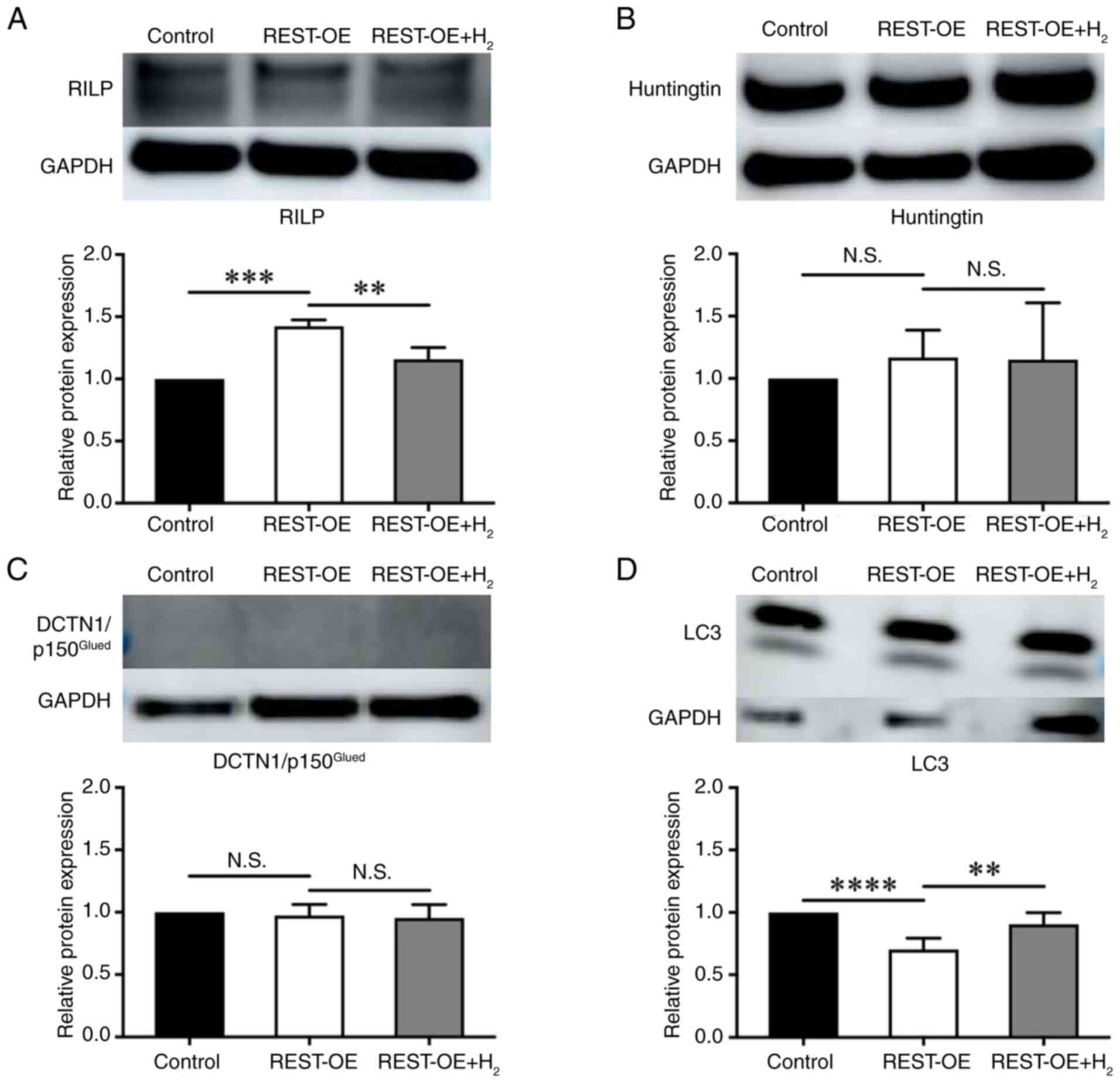

RILP levels were significantly higher in the REST-OE

group compared with the Control group (Control group:

1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 1.42±0.04-fold, P=0.0003);

however, it was significantly decreased following H2

treatment (1.42±0.04-fold in REST-OE vs. 1.16±0.08-fold in REST-OE

+ H2, P=0.0040) (Fig. 4A). In contrast, there was no

significant difference in the expression of Huntingtin between the

REST-OE group and the Control group (Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold;

REST-OE group: 1.17±0.18-fold, p=0.7587), as well as between the

REST-OE + H2 group and the REST-OE group (REST-OE group:

1.17±0.18-fold; REST-OE + H2 group: 1.15±0.37-fold, P=0.9970)

(Fig. 4B). There was no

significant difference in the expression of

DCTN1/p150Glued between the REST-OE group and the

Control group (Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group:

0.97±0.07-fold, P=0.9126), as well as between the REST-OE +

H2 group and the REST-OE group (REST-OE group:

0.97±0.07-fold; REST-OE + H2 group: 0.95±0.09-fold,

P=0.9421) (Fig. 4C). The

expression of LC3 was significantly decreased in the REST-OE group

compared with the Control group (Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold;

REST-OE group: 0.70±0.08-fold, P<0.0001), whereas it was

significantly increased in the REST-OE + H2 group

compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group: 0.70±0.08-fold;

REST-OE + H2 group: 0.91±0.08-fold, P=0.0022)

(Fig. 4D).

| Figure 4.RILP, Huntingtin,

DCTN1/p150Glued and LC3 expression in the control,

REST-OE and REST-OE + H2 groups evaluated by western

blotting. The REST-OE group was compared with the control group,

and the REST-OE + H2 group was compared with the REST-OE

group. The graphs show the semi-quantification of relative protein

expression. Mean ± SD, n=3 per group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001

and ****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). (A) RILP expression. (B)

Huntingtin expression. (C) DCTN1/p150Glued expression.

(D) LC3 expression. DCTN1, dynactin subunit 1; H2,

hydrogen; N.S., no significant difference; REST, repressor element

1 silencing transcription factor; REST-OE, REST-overexpressed;

RILP, REST-interacting LIM domain protein. |

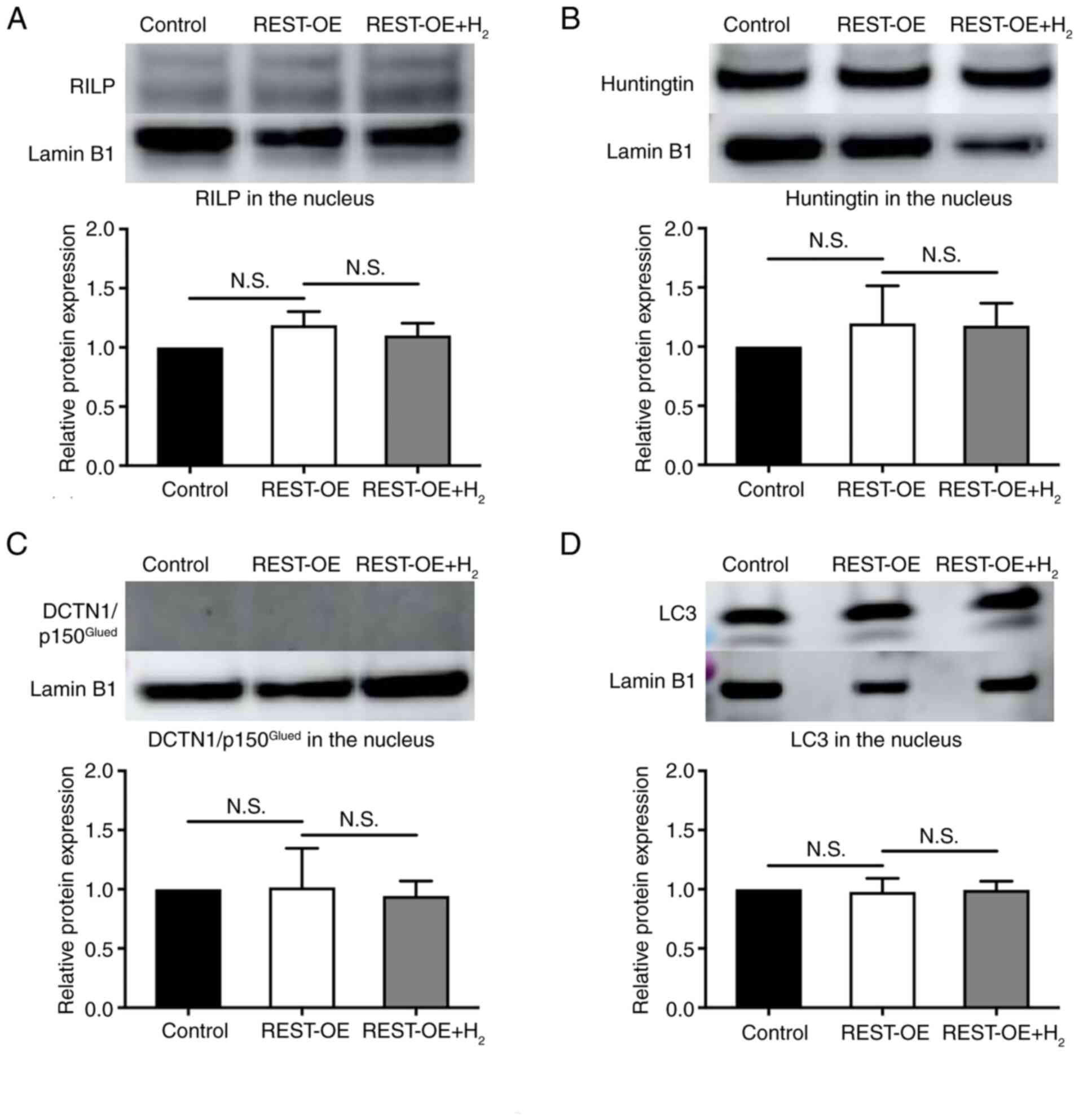

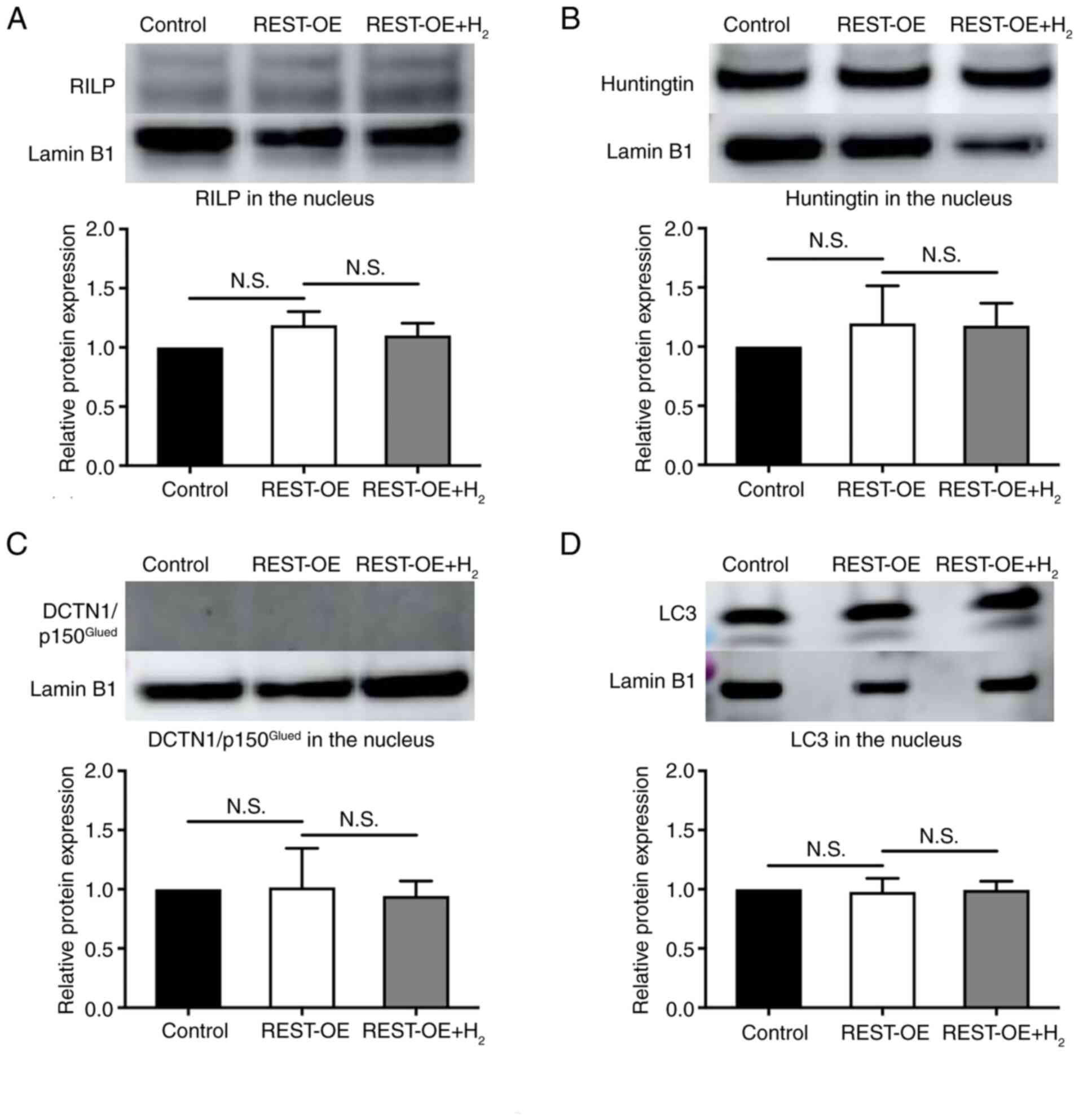

To further evaluate the effects of H2 on

REST in nuclear transport and cytoplasm degradation, the expression

of RILP, Huntingtin, DCTN1/p150Glued, and LC3 in

cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts was quantified by western

blotting. In the cytoplasm, the expression of RILP in the cytoplasm

was significantly increased in the REST-OE group compared with the

Control group (Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group:

1.43±0.04-fold, P<0.0001), whereas it was significantly

decreased in the REST-OE + H2 group compared with the

REST-OE group (REST-OE group: 1.43±0.04-fold; REST-OE +

H2 group: 0.97±0.06-fold, P<0.0001) (Fig. 5A). The expression of Huntingtin in

the cytoplasm was significantly increased in the REST-OE group

compared with the Control group (Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold;

REST-OE group: 1.54±0.16-fold, P=0.0105), whereas it was

significantly decreased in REST-OE + H2 group compared

with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group: 1.54±0.16-fold; REST-OE +

H2 group: 0.77±0.16-fold, P=0.0018) (Fig. 5B). The expression of

DCTN1/p150Glued in the cytoplasm was not significantly

different between the REST-OE group and the Control group (Control

group: 1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 0.92±0.07-fold, P=0.4667),

and between the REST-OE + H2 group and the REST-OE group

(REST-OE group: 0.92±0.07-fold; REST-OE + H2 group:

1.02±0.08-fold, P=0.3248) (Fig.

5C). The expression of LC3 in the cytoplasm was significantly

decreased in the REST-OE group compared with the Control group

(Control group: 1.00±0.00-fold; REST-OE group: 0.68±0.04-fold,

P=0.0017), whereas it was significantly increased in the REST-OE +

H2 group compared with the REST-OE group (REST-OE group:

0.68±0.04-fold; REST-OE + H2 group: 1.03±0.08-fold,

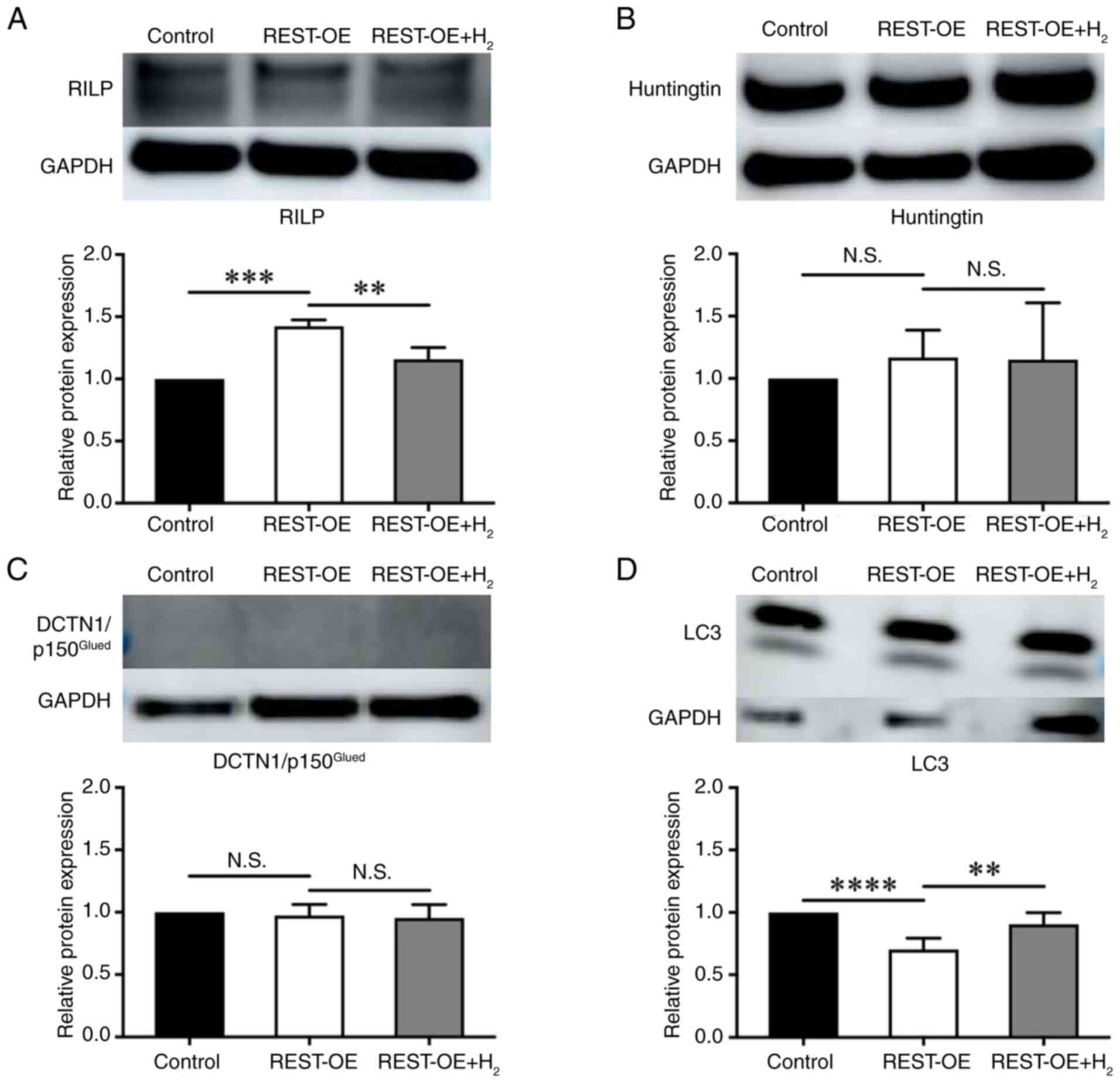

P=0.0011) (Fig. 5D). In the

nucleus, there was no significant difference between the expression

of RILP, Huntingtin, DCTN1/p150Glued, and LC3 between

the REST-OE group and the Control group (RILP: 1.19±0.09-fold,

P=0.0827; Huntingtin: 1.20±0.26-fold, P=0.5167;

DCTN1/p150Glued: 1.02±0.27-fold, p=0.9953; LC3:

0.98±0.10-fold, P=0.9079), as well as between the REST-OE +

H2 group and the REST-OE group (RILP: 1.10±0.08-fold,

P=0.4874; Huntingtin: 1.18±0.16-fold, P=0.9923;

DCTN/p150Glued: 0.94±0.10-fold, P=0.8998; LC3:

0.99±0.06-fold, P=0.9458) (Fig.

6A-D).

| Figure 5.RILP, Huntingtin,

DCTN1/p150Glued and LC3 expression in the cytoplasm of

the control, REST-OE and REST-OE + H2 groups evaluated

by western blotting. The REST-OE group was compared with the

control group, and the REST-OE + H2 group was compared

with the REST-OE group. The graphs show the semi-quantification of

relative protein expression. Mean ± SD, n=3 per group. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001 (one-way ANOVA). (A) RILP

expression. (B) Huntingtin expression. (C)

DCTN1/p150Glued expression. (D) LC3 expression. DCTN1,

dynactin subunit 1; H2, hydrogen; N.S., no significant

difference; REST, repressor element 1 silencing transcription

factor; REST-OE, REST-overexpressed; RILP, REST-interacting LIM

domain protein. |

| Figure 6.RILP, Huntingtin,

DCTN1/p150Glued and LC3 expression in the nucleus of the

control, REST-OE and REST-OE + H2 groups evaluated by

western blotting. The REST-OE group was compared with the control

group, and the REST-OE + H2 group was compared with the

REST-OE group. The graphs show the semi-quantification of relative

protein expression. Mean ± SD, n=3 per group. The data were

analyzed using one-way ANOVA. (A) RILP expression. (B) Huntingtin

expression. (C) DCTN1/p150Glued expression. (D) LC3

expression. DCTN1, dynactin subunit 1; H2, hydrogen;

N.S., no significant difference; REST, repressor element 1

silencing transcription factor; REST-OE, REST-overexpressed; RILP,

REST-interacting LIM domain protein. |

Together these results suggest that under REST-OE

conditions, REST nuclear transport proteins RILP and Huntingtin

were upregulated but autophagy was suppressed in the cytoplasm,

which promotes the nuclear transport of REST from the cytoplasm. On

the other hand, H2 inhibited the nuclear transport of

REST due to suppression of REST nuclear transport-related proteins

such as RILP and Huntingtin.

Discussion

In this study, REST expression was decreased, and

GAP43 expression was increased following H2

administration to aged animal models and REST-OE cells (Figs. 1 and 2). Next, we examined the intracellular

localization of REST expression. We found that REST expression was

increased in the cytoplasm and decreased in the nucleus following

H2 addition in REST-OE cells (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the REST expression

in the cytoplasm was investigated, focusing on nuclear transport

mechanisms and autophagy. We found that H2 addition led

to a decrease in several REST nuclear transport proteins, and

nuclear translocation of REST was suppressed (Fig. 5A-C). H2 administration

restored the impaired autophagic capacity (Fig. 5D).

Various types of stress promote nuclear transport of

proteins from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Hikeshi, which is not a

member of the importin family, is increased during heat shock

stress and promotes the nuclear transport of heat shock protein 70s

(19). On the other hand, in

vitro studies using human bronchial epithelial-like cells found

that the antioxidant vitamin E inhibits the nuclear transport of

phospho-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and

suppresses the induction of inflammatory cells (20). These findings suggest that the

nuclear transport of transcriptional factors depends on biological

stress. Previous studies reported that H2 has a

neuroprotective effect through antioxidant ability (17). Furthermore, it may affect nuclear

transport of transcriptional factors via its antioxidant ability.

Since both cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of REST were changed

by H2 administration in this study, our findings suggest

that H2 influences the nuclear transport of REST.

Moreover, H2 administration led to an increase in the

expression of axon regeneration markers through suppression of the

nuclear transport of REST. Therefore, nuclear transport of REST was

investigated through a molecular approach.

REST is transported into the nucleus by forming a

complex with RILP, Huntingtin, and DCTN1/p150Glued

(21). In this study, under high

REST expression conditions, the expression of RILP and Huntingtin

in the cytoplasm were increased, promoting the nuclear transport of

REST (Fig. 5A and B). On the other

hand, the expression of RILP and Huntingtin was decreased, and the

nuclear transport of REST was suppressed by H2 addition

(Fig. 5A and B). It is reported

that RILP is activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and

inhibited by the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (22,23).

Melatonin is an antioxidant that provides protective effects

against Huntington's disease (24). Additionally, melatonin decreases

with aging, leading to a decrease in antioxidant activity and an

increase in the expression of Huntingtin (24). It is likely that the antioxidant

ability of H2 led to a decrease in the expression of

RILP and Huntingtin. This study reveals new findings about the

regulatory roles of RILP and Huntingtin in the nuclear transport of

REST. On the other hand, among the REST nuclear transport proteins,

only DCTN1/p150Glued in the cytoplasm remained

unaffected by changes in REST expression.

DCTN1/p150Glued has other functions than the nuclear

transport of REST, such as retrograde axonal transport, and

microtubule stabilization (25,26).

Therefore, the change in the expression of

DCTN1/p150Glued in the cytoplasm was not detectable,

although the nuclear transport of REST was suppressed.

Autophagy is an important process for maintaining

cellular homeostasis (27);

however, its activity decreases with aging (28,29).

Furthermore, REST expression in neurons increases with age, leading

to decreased autophagy activity (30). On the other hand, myocardial

protective effects of H2 on sepsis-induced

cardiomyopathy via autophagy activation (31). Thus, H2 may have the

capacity to promote autophagy activity according to these reports.

In this study, the expression of LC3 in both whole-cell and

cytoplasmic fractions are increased in REST-OE cells by

H2 addition (Figs. 4D

and 5D). Therefore,

H2-induced changes in autophagy activity in the

cytoplasm may be upregulated.

This study has some limitations. First, a

comprehensive analysis of the nuclear transport proteins related to

REST, which have various functions in neurons, was not performed.

RILP, Huntingtin, and DCTN1/p150Glued were selected as

they form a complex with REST and that protein complex plays

essential roles in the nuclear transport of REST (21). Second, the optimal duration of

H2 administration and addition was not evaluated. The

primary methods of H2 administration include inhalation

of H2 gas, drinking HRW, and injection of

H2-containing physiological saline (32). In this study, the duration of

intraperitoneal injection of H2-containing physiological

saline was determined based on a study evaluating autophagy in a

rat neurodegeneration model (33).

Additionally, in the in vitro study using H9C2 cells in a

hypoxia-reoxygenation model, the H2 administration

period was set to 2 h based on a previous study that assessed cell

survival (34). Third, REST-OE

cells used in this study were generated by fibroblasts, which are

non-neuronal cells. Although Schwann cells were initially

considered due to their physiological relevance to the peripheral

nervous system, stable overexpression of REST in these cells was

not achieved. This limitation was likely attributable to a

combination of REST-induced growth inhibition and cytotoxic effects

associated with Lipofectamine 3000-based transfection.

Consequently, fibroblasts were selected as an alternative model due

to their genetic stability and widespread use in studies of

nuclear-cytoplasmic transport mechanisms. Although primary cultured

neurons can be maintained for a limited period, their application

in long-term experiments is constrained. In fact, Xue et al

(30) considered a 10-day culture

duration as ‘long-term’ in studies using neuronal cell.

Furthermore, gene delivery efficiency in primary neurons is

generally low, and specialized transfection methods are often

required (35). On the other hand,

a previous study reported the use of NIH3T3 cells, the cells used

in the present study, in peripheral nerve research (36). Furthermore, the nuclear transport

mechanism of megakaryoplastic leukemia 1 protein, a co-activator of

the transcription factor serum response factor, has been analyzed

using the NIH3T3 cell line (37).

Thus, the use of NIH3T3 cells is considered scientifically valid

for studying the nuclear transport mechanisms of cytoplasmic

proteins. Nevertheless, this approach has a limitation in

physiological relevance, as fibroblasts differ from neuronal cells

and cannot replicate neuron-specific functions or the neural

microenvironment (38).

Consequently, the current findings may not fully reflect the in

vivo role of REST. To address this limitation, future studies

are planned using peripheral nerve-specific conditional REST

knockout mice. In vivo axonal regeneration will be evaluated

using a sciatic nerve crush model, and axon regeneration will be

assessed in primary cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons. These

approaches are expected to complement the current in vitro

results and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the

physiological role of REST in peripheral nerve regeneration.

Previous studies reported that axon regenerative

capacity declines with aging, however, the underlying pathology

remains unclear. In this study, to elucidate the pathology of

age-related decline in axonal regeneration, the molecular

mechanisms involved in REST nuclear transport were analyzed. The

results of this study suggest that the regulation of nuclear

transport of REST may improves the decline in age-related axon

regeneration.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Japan Society of the

Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant no. 22K09342).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KN, DK and YU conceptualized the study. TS, TNK and

YY designed the methodology. TS performed most of the experiments.

SK, NI and KK assisted with the experiments. TS, KN, NH and MI

analyzed and interpreted the data. TS and KN prepared the original

draft, while TS, KN and MI reviewed and edited the manuscript. KN

secured funding. TS, KN, DK and NH confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Animal Care

Committee of Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan (registration no.

1555; approval no. 2024183; date of approval, March 12, 2024).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Murayama M, Hirata H, Shiraki M, Iovanna

JL, Yamaza T, Kukita T, Komori T, Moriishi T, Ueno M, Morimoto T,

et al: Nupr1 deficiency downregulates HtrA1, enhances SMAD1

signaling, and suppresses age-related bone loss in male mice. J

Cell Physiol. 238:566–581. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ke HZ, Richards WG, Li X and Ominsky MS:

Sclerostin and Dickkopf-1 as therapeutic targets in bone diseases.

Endocr Rev. 33:747–783. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Creecy A, Brown KL, Rose KL, Voziyan P and

Nyman JS: Post-translational modifications in collagen type I of

bone in a mouse model of aging. Bone. 143:1157632021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yang TL, Shen H, Liu A, Dong SS, Zhang L,

Deng FY, Zhao Q and Deng HW: A road map for understanding molecular

and genetic determinants of osteoporosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

16:91–103. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rim YA, Nam Y and Ju JH: The role of

chondrocyte hypertrophy and senescence in osteoarthritis initiation

and progression. Int J Mol Sci. 21:23582020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fujii Y, Liu L, Yagasaki L, Inotsume M,

Chiba T and Asahara H: Cartilage homeostasis and osteoarthritis.

Int J Mol Sci. 23:63162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Verdú E, Ceballos D, Vilches JJ and

Navarro X: Influence of aging on peripheral nerve function and

regeneration. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 5:191–208. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mampay M and Sheridan GK: REST: An

epigenetic regulator of neuronal stress responses in the young and

ageing brain. Front Neuroendocrinol. 53:1007442019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Goto K, Naito K, Nakamura S, Nagura N,

Sugiyama Y, Obata H, Kaneko A and Kaneko K: Protective mechanism

against age-associated changes in the peripheral nerves. Life Sci.

253:1177442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kaneko A, Naito K, Nakamura S, Miyahara K,

Goto K, Obata H, Nagura N, Sugiyama Y and Kaneko K: Influence of

aging on the peripheral nerve repair process using an artificial

nerve conduit. Exp Ther Med. 21:1682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rodriguez-Bravo V, Pippa R, Song WM,

Carceles-Cordon M, Dominguez-Andres A, Fujiwara N, Woo J, Koh AP,

Ertel A, Lokareddy RK, et al: Nuclear pores promote lethal prostate

cancer by increasing POM121-driven E2F1, MYC, and AR nuclear

import. Cell. 174:1200–1215.e20. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kawamura M, Sato S, Matsumoto G, Fukuda T,

Shiba-Fukushima K, Noda S, Takanashi M, Mori N and Hattori N: Loss

of nuclear REST/NRSF in aged-dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson's

disease patients. Neurosci Lett. 699:59–63. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lu T, Aron L, Zullo J, Pan Y, Kim H, Chen

Y, Yang TH, Kim HM, Drake D, Liu XS, et al: REST and stress

resistance in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 507:448–454.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mir AR and Moinuddin Islam S: Circulating

autoantibodies in cancer patients have high specificity for

glycoxidation modified histone H2A. Clin Chim Acta. 453:48–55.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nagata K, Nakashima-Kamimura N, Mikami T,

Ohsawa I and Ohta S: Consumption of molecular hydrogen prevents the

stress-induced impairments in hippocampus-dependent learning tasks

during chronic physical restraint in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology.

34:501–508. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wang J, Zhang XJ, Du YY, Shi G, Zhang CC

and Chen R: Hydrogen-rich saline promotes neuronal recovery in mice

with cerebral ischemia through the AMPK/mTOR signal-mediated

autophagy pathway. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars). 83:317–330. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Han XC, Ye ZH, Hu HJ, Sun Q and Fan DF:

Hydrogen exerts neuroprotective effects by inhibiting oxidative

stress in experimental diabetic peripheral neuropathy rats. Med Gas

Res. 13:72–77. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2 (−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kose S, Furuta M and Imamoto N: Hikeshi, a

nuclear import carrier for Hsp70s, protects cells from heat

shock-induced nuclear damage. Cell. 149:578–589. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zhao H, Gong J, Li L, Zhi S, Yang G, Li P,

Li R and Li J: Vitamin E relieves chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease by inhibiting COX2-mediated p-STAT3 nuclear translocation

through the EGFR/MAPK signaling pathway. Lab Invest. 102:272–280.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Shimojo M: Huntingtin regulates

RE1-silencing transcription factor/neuron-restrictive silencer

factor (REST/NRSF) nuclear trafficking indirectly through a complex

with REST/NRSF-interacting LIM domain protein (RILP) and dynactin

p150 Glued. J Biol Chem. 283:34880–34886. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Daulat AM, Wagner MS, Audebert S,

Kowalczewska M, Ariey-Bonnet J, Finetti P, Bertucci F, Camoin L and

Borg JP: The serine/threonine kinase MINK1 directly regulates the

function of promigratory proteins. J Cell Sci. 135:jcs2593472022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fu G, Xu Q, Qiu Y, Jin X, Xu T, Dong S,

Wang J, Ke Y, Hu H, Cao X, et al: Suppression of Th17 cell

differentiation by misshapen/NIK-related kinase MINK1. J Exp Med.

214:1453–1469. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kim J, Li W, Wang J, Baranov SV, Heath BE,

Jia J, Suofu Y, Baranova OV, Wang X, Larkin TM, et al: Biosynthesis

of neuroprotective melatonin is dysregulated in Huntington's

disease. J Pineal Res. 75:e129092023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Moughamian AJ and Holzbaur EL: Dynactin is

required for transport initiation from the distal axon. Neuron.

74:331–343. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lazarus JE, Moughamian AJ, Tokito MK and

Holzbaur EL: Dynactin subunit p150(Glued) is a neuron-specific

anti-catastrophe factor. PLoS Biol. 11:e10016112013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Aman Y, Schmauck-Medina T, Hansen M,

Morimoto RI, Simon AK, Bjedov I, Palikaras K, Simonsen A, Johansen

T, Tavernarakis N, et al: Autophagy in healthy aging and disease.

Nat Aging. 1:634–650. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kaushik S, Tasset I, Arias E, Pampliega O,

Wong E, Martinez-Vicente M and Cuervo AM: Autophagy and the

hallmarks of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 72:1014682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Xue WJ, He CF, Zhou RY, Xu XD, Xiang LX,

Wang JT, Wang XR, Zhou HG and Guo JC: High glucose and palmitic

acid induces neuronal senescence by NRSF/REST elevation and the

subsequent mTOR-related autophagy suppression. Mol Brain.

15:612022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cui Y, Li Y, Meng S, Song Y and Xie K:

Molecular hydrogen attenuates sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy in mice

by promoting autophagy. BMC Anesthesiol. 24:722024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Iketani M and Ohsawa I: Molecular hydrogen

as a neuroprotective agent. Curr Neuropharmacol. 15:324–331. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang H, Huo X, Chen H, Li B, Liu J, Ma W,

Wang X, Xie K, Yu Y and Shi K: Hydrogen-rich saline activated

autophagy via HIF-1α pathways in neuropathic pain model. Biomed Res

Int. 2018:46708342018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Song D, Liu X, Diao Y, Sun Y, Gao G, Zhang

T, Chen K and Pei L: Hydrogen-rich solution against myocardial

injury and aquaporin expression via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

during cardiopulmonary bypass in rats. Mol Med Rep. 18:1925–1938.

2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Palomino SM, Gabriel KA, Mwirigi JM,

Cervantes A, Horton P, Funk G, Moutal A, Martin LF, Khanna R, Price

TJ and Patwardhan A: Genetic editing of primary human dorsal root

ganglion neurons using CRISPR-Cas9. Sci Rep. 15:111162025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tanaka H, Yamashita T, Asada M, Mizutani

S, Yoshikawa H and Tohyama M: Cytoplasmic p21(Cip1/WAF1) regulates

neurite remodeling by inhibiting Rho-kinase activity. J Cell Biol.

158:321–329. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Rajakylä EK, Viita T, Kyheröinen S, Huet

G, Treisman R and Vartiainen MK: RNA export factor Ddx19 is

required for nuclear import of the SRF coactivator MKL1. Nat

Commun. 6:59782015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Vierbuchen T, Ostermeier A, Pang ZP,

Kokubu Y, Südhof TC and Wernig M: Direct conversion of fibroblasts

to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature. 463:1035–1041.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|