Introduction

In recent years, the incidence of new global cancer

cases has been consistently increasing. As indicated in the World

Health Organization report, malignant neoplasms are among the

predominant causes of mortality worldwide, and it is estimated that

the global population of patients with cancer will reach 28.4

million by 2040 (1). The onset and

progression of malignant tumors are closely associated with the

tumor microenvironment, which comprises tumor cells, immune cells,

fibroblasts, the extracellular matrix and a variety of cytokines

that enhance the proliferation, migration and immune evasion

capabilities of tumor cells (2).

As research into the tumor microenvironment has increased, tumor

immunotherapy has emerged as a novel and promising therapeutic

modality for the management of cancer. This type of therapy

uniquely activates the immune microcirculation, thereby eliciting a

targeted immune response against tumor cells and facilitating their

destruction. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been used in

the treatment of tumors, with an emphasis on individualized patient

care (3). Throughout the course of

tumor progression, TCM has demonstrated efficacy in bolstering

immunity, thereby restoring and maintaining normal immune

functions, preventing the invasion of exogenous pathogens and

mitigating the detrimental effects of tumor cells. These principles

are consistent with the modern medical concept of tumor

immunotherapy. Astragalus polysaccharide (APS) can modulate

various immune cells, including macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs),

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), T lymphocytes and natural

killer (NK) cells, thereby altering their functional activities and

enhancing immune responsiveness. Consequently, the tumor immune

microenvironment and the cytotoxic capability of immune cells

against tumor cells are improved (4). In the present study, research on the

antitumor immune properties of APS has been comprehensively

reviewed, and its regulatory effects on immune cells and the

underlying antitumor mechanisms are discussed, thereby providing a

theoretical foundation for the development of novel

Astragalus-based antitumor pharmacological agents.

Chemical structure of APS

Huangqi (Jianqi) is the dried root of the leguminous

plant Astragalus mongholicus or Astragalus

membranaceus (5). As a common

traditional Chinese herbal medicine, Astragalus has a history of

more than 2,000 years of use in China, is used extensively in

numerous countries and has been included in the pharmacopeias of

the United States, Japan, and South Korea (6). The constituents of Astragalus

encompass a variety of compounds such as APS, triterpenoid

saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids and different mineral elements

(7–10). APS, which serves as the principal

active constituent within Astragalus, is characterized by

its copious availability, affordability, and minimal toxic or

adverse effects (11). The

categorization of polysaccharides is performed in accordance with

the structural classification principles employed for proteins and

DNA. Investigating the constituent monosaccharides, relative

molecular mass and sequential arrangement of monosaccharide

residues is necessary to elucidate the structure of APS (12). APS is classified as an acidic

complex polysaccharide, predominantly comprising glucose (Glc),

galactose (Gal), arabinose (Ara), rhamnose (Rha) and mannose (Man).

Infrared spectroscopic analysis has revealed that APS possesses the

typical infrared absorption characteristics of sugar, along with

distinct signals that are attributed to the carboxyl group,

indicating the presence of glucuronic acid. The signals

corresponding to sugar rings indicate that APS constitutes a

pyranose ring structure with α and β configurations (13). Glucose is a monosaccharide based on

a glucopyranose structure, including α-D-Glu, β-D-Glu and α,

β-D-Glu, with β-D-Glu being the most extensively investigated

monosaccharide (14).

Given the presence of numerous branched chains and a

number of hydroxyl groups, APS exhibits a high degree of structural

diversity and complexity (Table

I). APS MAPS-5 is composed of an α-D-(1–4) Glc

backbone, where, on average, approximately two out of every 15

sugar residues at the C-6 position are substituted with terminal

glucose residues, with an approximate relative molecular weight of

1.32×104 (15).

Furthermore, three distinct polysaccharides, namely APS I, II and

III, have been isolated from the aqueous extract of

Astragalus roots sourced from Inner Mongolia. APS I is a

heteropolysaccharide composed of D-Glu, D-Gal, and L-Ara in a molar

ratio of 1.75:1.63:1, with an average relative molecular mass of

approximately 3.63×104. APS II and III are predominantly

composed of D-Glu, with average relative molecular weights of

~1.23×104 and 3.46×104, respectively. Their

structure primarily comprises α-(1→6)-D-Glc condensation linkages,

with a minor fraction of α-(1→6)-D-Glc condensation bonds (16). Through complete acid hydrolysis,

four types of APS have been differentiated, including two glucans

(AG-1 and AG-2) and two heteropolysaccharides (AH-1 and AH-2)

(17). AG-1 is a water-soluble

glucan, whereas AG-2 is water insoluble and is characterized as an

α-(1→4) glucan. AH-1 is an acidic, water-soluble polysaccharide;

after hydrolysis, AH-1 contains hexuronic acids (galacturonic and

glucuronic acids), glucose, rhamnose and arabinose, as identified

through paper chromatography, with a molar ratio of

1:0.04:0.02:0.01. AH-2 is also water soluble, and the presence of

glucose and arabinose can be confirmed via paper and gas

chromatography post-hydrolysis, with a molar ratio of 1:0.15

(17).

| Table I.Chemical structure of APS. |

Table I.

Chemical structure of APS.

| First author,

year | Polysaccharide

name | Monosaccharide

composition | Relative molecular

mass | Quantity ratio of

matter | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Lin, 2009 | APS MAPS-5 | α-D-(1–4)

Glc |

1.32×104 | - | (15) |

| Fang, 1982 | APS I | D-Glu, D-Gal,

L-Ara |

3.63×104 | 1.75:1.63:1 | (16) |

| Fang, 1982 | APS II | D-Glu |

1.23×104 | - | (16) |

| Fang, 1982 | APS III | D-Glu |

3.46×104 | - | (16) |

| Huang, 1982 | AG-1 | Water-soluble

glucan | - | - | (17) |

| Huang, 1982 | AG-2 | α-(1→4) glucan | - | - | (17) |

| Huang, 1982 | AH-1 | Hexuronic acids

(Glc UA and Gal UA), | - |

1:0.04:0.02:0.01 | (17) |

|

|

| Glc, Rha and

Ara |

|

|

|

| Huang, 1982 | AH-2 | Glc and Ara | - | 1:0.15 | (17) |

| Tang, 2014 | APS-I | Man, Rha, Glc UA,

Gal UA, Glc, Gal |

1.06×104 |

29.12:1.89:4.00:1.35:1:81.97 | (18) |

| Tang, 2014 | APS-II | Man, Rha, Glc UA,

Gal UA, Glc, Gal, Xyl |

2.47×106 | 50.46:1.16:1:2.27:

2.66:15.72:7.86 | (18) |

| Cao, 2020 | APS | Rha, Gal UA, Glc,

Gal, Ara |

300-2×106 |

0.43:0.23:19.36:0.69:1 | (19) |

| Liu, 2020 | APS I | Gal, Glc | - | 1:49.76 | (20) |

| Liu, 2020 | APS II | Rha, Gal, Glc | - | 1:2.99:16.26 | (20) |

Tang et al (18) extracted and isolated

polysaccharides from Astragalus, and characterized their

physicochemical properties and structure. This previous study

revealed that the composition of monosaccharides in APS-I was

mannose (Man), rhamnose (Rha), Glc uronic acid (Glc UA), Gal UA,

Glc and Gal, with a substance amount ratio of

29.12:1.89:4.00:1.35:1:81.97, whereas the composition of

monosaccharides in APS-II was Man, Rha, Glc UA, Gal UA, Glc, Gal

and xylose, with a substance amount ratio of

50.46:1.16:1:2.27:2.66:15.72:7.86. The relative molecular mass of

APS-I was ~1.06×104, and the relative molecular mass of

APS-II was ~2.47×106. Cao et al (19) extracted from the experiment that

the total polysaccharide content of APS was 74.6%, the protein

content was 0.42%, and the relative molecular weight distribution

was 300–2×106. In addition, its monosaccharide

composition was Rha, Gal UA, Glc, Gal and Ara, with a substance

amount ratio of 0.43:0.23:19.36:0.69:1. Furthermore, a previous

study characterized the monosaccharide group of two polysaccharides

obtained from the isolation and purification of Astragalus

membranaceus from Mongolia using ion chromatography. The

results showed that APS I was composed of Gal and Glc, with a

substance amount ratio of 1:49.76, whereas APS II mainly consisted

of Rha, Gal and Glc, with a substance amount ratio of 1:2.99:16.26

(20). Although a number of

technical methods have been used to analyze APS, the specific

molecular structure of APS remains difficult to elucidate, which

results in certain obstacles in the study of the molecular

mechanism underlying APS bioactivity.

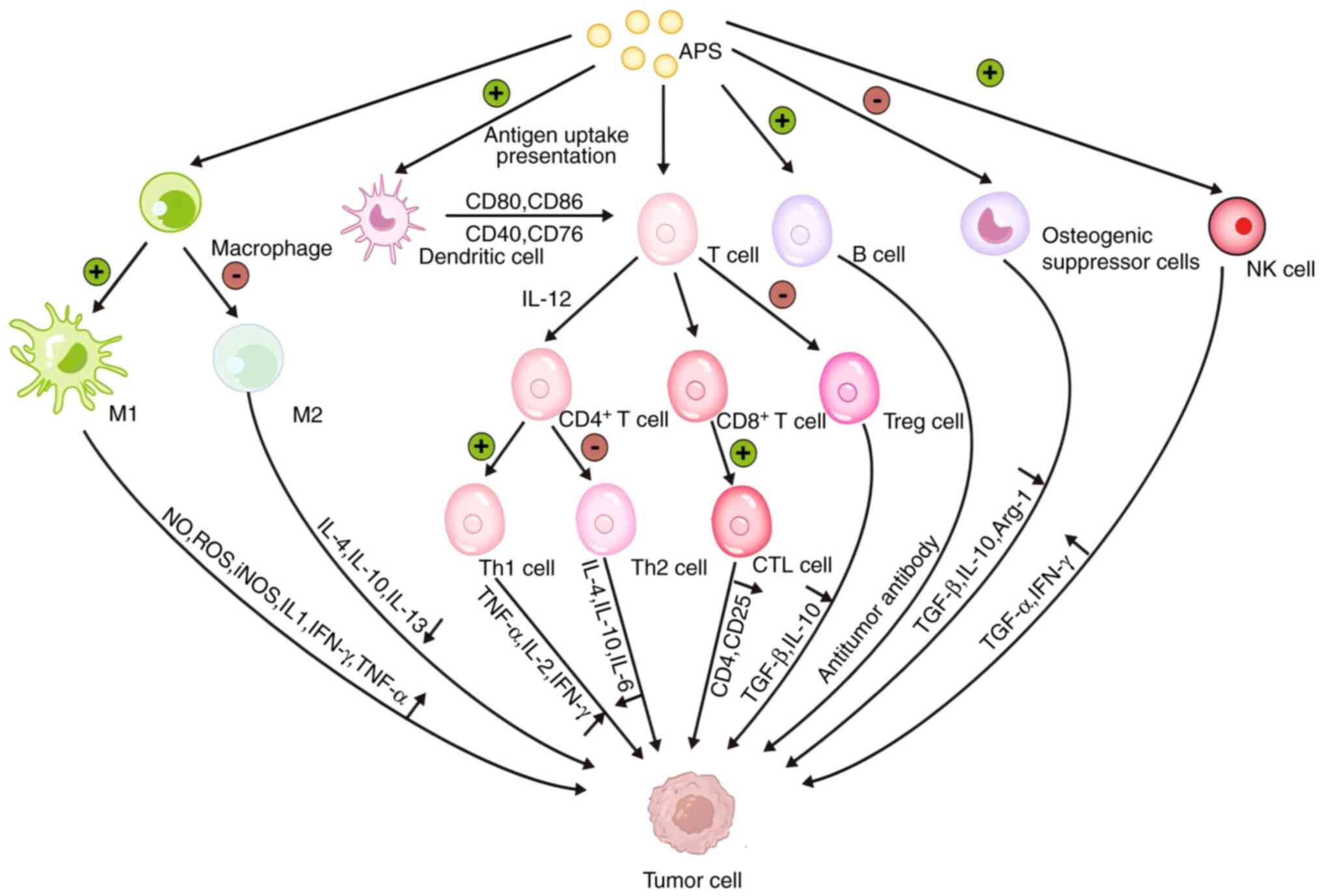

APS regulates tumor immune function

As academic research on tumor immunotherapy

continues, the successful development of immune checkpoint

inhibitors that target PD-1, CTLA-4 and PD-L1 has led to the

gradual emergence of immunotherapy as a potential method to treat

tumors (21). Body immunity is

divided into active and passive immunity. Tumor cells evade

elimination by the immune system, which not only promotes the state

of immunosuppression and the production of regulatory immune cells,

but also recruits a large number of protumor cells to establish a

tumor microenvironment (22). In

the tumor microenvironment, tumor cells inhibit the antigen

presentation function of DCs; promote the polarization of

tumor-associated macrophages from M1 type to M2 type; release the

immune-suppressive factors TGF-β, VEGF and IL-10; deliver the

abnormally expressed tumor-associated antigens to T cells; induce

T-cell apoptosis; and inhibit the function of cytotoxic T

lymphocytes, which together affect the immune system and result in

tumor immune escape and the acceleration of tumor progression

(23–26). In determining the mechanism

underlying tumor immune escape, current immunotherapeutic drugs,

including drugs that block negative regulatory signals,

immunostimulatory drugs, tumor vaccines and exogenous recombinant

cytokines, have been used (27),

among which immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti CTLA-4 and

anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies, have shown good therapeutic effects in

clinical tumor therapy. A number of active ingredients of TCM have

shown effects on regulating immune cells and improving the tumor

microenvironment, indicating their therapeutic potential in

synergistic radiotherapy and chemotherapy against tumors (28).

APS, as a main active ingredient of

Astragalus, has important pharmacological effects, including

immune-regulatory and antitumor properties, which can regulate the

microenvironment of numerous solid tumors, improve the state of

immune suppression and inhibit tumor growth. APS inhibits the

M2-type polarization of tumor-associated macrophages, increases

cytotoxic T lymphocyte infiltration, and promotes the maturation of

DCs and the function of NK cells (29). In addition, APS not only reduces

the release of the immunosuppressive factors IL-10, TGF-β and VEGF

in the tumor microenvironment, but also increases the levels of the

immune activating factors TNF-α, IL-2 and IL-12 (30). In clinical trials for patients with

cancer, APS has been shown to relieve pain, nausea and vomiting

symptoms, enhance immune function, reduce the toxic side effects of

chemotherapeutic drugs and improve quality of life (31) (Table

II; Figs. 1 and 2).

| Table II.Antitumor immune mechanism of

APS. |

Table II.

Antitumor immune mechanism of

APS.

| Pharmacological

action | Function | Intervention

model | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Regulation of

macrophage M1/M2 type polarization | Promoted the

production of cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α and inducible NO

synthase, through the Notch signaling pathway to activate M1

macrophages, while inhibiting macrophage M2-type polarization | Non-small cell lung

cancer; mouse macrophages | (36) |

|

| Influence cell-cell

interactions, specifically through modulation of macrophage M2

polarization and CD8+ | Macrophages | (37) |

|

| T-cell exhaustion,

thereby overcoming DDP resistance |

|

|

|

| Increased the

proportion of M1 macrophages in HCC tumor cell tissues and

decreased macrophage M2 type polarization | Macrophages in HCC

tumor cell tissues | (38) |

|

| Increased cellular

energy metabolism and enhanced phagocytosis of RAW 264.7 mouse

monocyte macrophages | RAW 264.7 monocyte

macrophages | (39,40) |

|

| Activated mouse

macrophages through TLR4-mediated signaling pathways, upregulated

the expression of p-p38, p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK, induced the

degradation of IκB-α and NF-κB translocation, and ultimately

produced TNF-α, IL-6 and nitric oxide | Macrophages | (41,42) |

|

| Enhanced the

proliferation and phagocytic function of mouse macrophages;

increased the content of IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ in the peripheral

blood of mice | Macrophages | (43) |

| Induces activation

of DCs | Induced the DC cell

surface molecule CD80 through the TLR2/4 receptor-mediated MyD88

signaling pathway, CD86 and IL-12 expression, increased T

lymphocyte activity and released more IL-2 | DCs | (49,50) |

|

| Activated DCs

through the TLR-mediated signaling pathway, increased the

expression of co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of DCs, and

enhanced the antigen-presenting ability of tumor cells, which led

to the rapid migration of DCs to lymph nodes, activated the initial

T lymphocytes in the lymph nodes and inhibited the growth of

secondary lymph node tumors | DCs | (51) |

|

| After APS

treatment, DCs promoted the proliferation of CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells in mice with breast cancer; DC-based

antitumor vaccine increased the expression of CD40, CD80 and CD86

molecules on the surface of DCs, and inhibited the proliferation

and metastasis of breast cancer tumor cells | DCs | (52) |

|

| APS activated BDCA1

and BDCA3 peripheral blood dendritic cells elicited proliferative

activation of autologous T cells | Monocyte-derived

DCs | (53) |

| Reduces the number

and activity of MDSCs | Suppress MDSC

generation and reduce the MDSC population in the spleens of

tumor-bearing mice. | MDSCs in the spleen

of tumor-bearing mice | (57) |

|

| Concurrently, APS

downregulates immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β) while

upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α), thereby

enhancing overall immune function |

|

|

|

| Reduced the number

of MDSCs, decreased the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs in mice

with melanoma, decreased the expression of Arg-1, IL-10 and TGF-β,

and enhanced the killing ability of CD8+ T cells on

tumor cells | MDSCs in mice with

melanoma | (58) |

|

| Reduced the level

of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the peripheral circulation

of lung cancer, continuously improve imune function, and increas

teh overall clinical treatment efficacy | MDSCs | (59) |

|

| The protein and

gene expression of S1PR1, STAT3 and p-STAT3 in the S1PR1/STAT3

signaling pathway was inhibited by APS, which interfered with the

S1PR1/STAT3 signaling pathway and inhibited the accumulation of

MDSCs in the pre-metastatic niche | MDSCs | (61) |

| Reversal of Th1 to

Th2 conversion | Increased the

expression of Th1 cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ, decreased the

expression of Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-10, regulated the ratio of

Th1/Th2 cells, reversed the conversion of Th1 to Th2 cells through

the TLR4/ MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway | Th1 cells and Th2

cells in the spleen tissue of mice with lung cancer | (62) |

|

| Not only increased

the immune organ index in mice with lung cancer, but also increased

the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ cells in mouse serum

and significantly enhanced cellular immune activity |

CD4+/CD8+ T

cells | (63,64) |

|

| Protected the

immune organs and regulated the ratio of

CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocyte subpopulations |

CD4+/CD8+ T

lymphocyte subpopulations | (65) |

|

| Increases the

number of allogeneic T lymphocytes and the expression level of

IL-12 and IFN-γ. In addition, cytotoxic T lymphocytes activated by

sensitized DCs kill tumor cells | T lymphocyte | (66) |

| Suppression of Treg

cells | Reduced the number

of Treg cells, decreased the expression of | Treg cells | (69) |

|

| splenic TGF-β and

IL-10 in mice with malignant melanoma, |

|

|

|

| and inhibited tumor

cell metastasis of malignant melanoma in |

|

|

|

| mice Repaired

cytokine imbalance, inhibited forkhead box | Treg cells | (70) |

|

| protein P3

expression, and suppressed Treg cell activity and function |

|

|

|

| Inhibited the

expression of TGF-β by activating the TLR4-mediated signaling

pathway, which reduced the number of Treg cells | Treg cells | (71) |

|

| Reduced Treg

frequency, decreased anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-10,

TGF-β, and VEGF-A, and incresaed the pro-inflammatory cytokine

IL-6 | Treg cells | (72) |

| Enhances NK cell

killing activity | Inhibited the

proliferation of leukemia cells by activating MHC class I

polypeptide-related sequence A molecules on the surface of leukemia

cells and enhanced the killing sensitivity of NK cells to HL-60

leukemia cells | NK cells | (78) |

|

| Protected immune

organs and stimulated NK cells to kill tumor cells; promoted the

proliferation of splenic lymphocytes, improved NK cell activity and

enhanced the immune response ability of rats with cancer | Lymphocytes and NK

cells | (79,80) |

| Inhibition of tumor

cell proliferation | Inhibited the

proliferation of ovarian cancer cells through the miR-27a/F-box and

WD-40 structural domain protein 7 signaling pathway | Ovarian cancer

cells | (81) |

|

| Inhibited the

proliferation and migration of NSCLC cells and its mechanism of

action was related to the regulation of the miR-195-5p signaling

pathway; improved the morphology of lung cancer cells by inhibiting

the lung cancer cell cycle | NSCLC cells | (83,84) |

|

| Inhibited

TGF-β1-induced EMT of A549/DDP cell xenografts of lung

adenocarcinoma, which was associated with the inhibition of PI3K/

Akt pathway protein activation | A549/DDP lung

adenocarcinoma cell graft tumor | (85) |

|

| APS had an

inhibitory effect on the cell proliferation of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cell lines in a time-and dose-dependent manner; the

combination of APS and cisplatin inhibited the migration and

invasion of CNE-1 cells | CNE-1

nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells | (86) |

|

| Inhibited the

proliferation of SW620 human colorectal cancer cells, which were

subjected to cyclic inhibition, with a predominant G2/M

phase block | SW620 colorectal

cancer cells | (87) |

|

| Inhibited the

proliferation and invasion of PCa cells in a time-and

dose-dependence manner; inhibited tumorigenesis and lipid

metabolism by modulating the miR-138-5p/SIRT1/SREBP1 pathway in

PCa | PCa cells | (88) |

|

| Enhanced miR-133a

expression and inhibited the JNK signaling pathway in MG63

osteosarcoma cells, which suppressed proliferation, migration and

invasion, and induced apoptosis in MG63 cells | MG63 osteosarcoma

cells | (89) |

| Induces apoptosis

in tumor cells | Promotes the

anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of cisplatin on

nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells, by regulating the expression levels

of Bax/Bcl-2, caspase-3, and caspase-9 | Nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cells | (94) |

|

| Decreased the

viability of GC cells and accelerated their apoptosis in a time-

and dose-dependent manner; MGC-803 cells treated with APS showed

typical apoptotic morphology and cell cycle arrest in S phase | GC cells | (95) |

|

| Promoted apoptosis

in NSCLC cell lines by inhibiting the expression of Notch1 and

Notch3, and upregulating tumor suppressors | NSCLC cells | (97–101) |

|

| Induced apoptosis

of tumor cells and prevented cell transformation from G1

phase to S phase of cell cycle | - | (102) |

|

| Decreased the

number of HepG2 liver cancer cells in S phase, and differentiated

the cells into G0/G1 and G2/M

phases, which blocked the cellular proliferation cycle and induceed

cancer cell apoptosis | HepG2 cells | (103,104) |

|

| Promoted the

apoptosis of HepG2 cells, increased the activity of caspase-3,

decreased the expression of ERK1/2, inhibited the ERK1/2 signaling

pathway and promoted the apoptosis of tumor cells | HepG2 cells | (105) |

|

| APS

dose-dependently promoted Dox-induced apoptosis and enhanced ER

stress; decreased O-GlcNAc transferase mRNA levels and protein

stability, and increased O-GlcNAcase expression; promoted

Dox-induced apoptosis in HCC cells by decreasing O-GlcNAcylation,

leading to increased ER stress and activation of apoptotic

pathways | HCC cells | (114) |

| Inhibits tumor cell

invasion and metastasis | Inhibited the

growth and metastasis of Lewis lung cancer in mice, improved the

function of the immune organs, and inhibited the expression of VEGF

and EGFR proteins in tumor tissues | Lewis lung

cancer | (116) |

|

| Downregulated NF-κB

transcriptional activity, and significantly inhibited the

proliferation and metastasis of A549 and NCI-H358 NSCLC cells | A549 and NCI-H358

NSCLC cells | (117,118) |

|

| Inhibited

angiogenesis of human colorectal cancer tumors and decreased VEGF

expression in tumor tissue | Colorectal cancer

tumor | (119) |

|

| Inhibited the

proliferation and invasion of HS-746T cells, suppress the

expression of miR-25 mRNA, and promote the expression of FBXW7

mRNA. It can also reverse the increase in MiR-25 and the

suppression of FBXW7 caused by transfection with miR-25 minic. APS

inhibits the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer HS-746-T

cells through the miR-25/FBXW7 signaling pathway. | Gastric cancer

HS-746T cells | (120) |

|

| Promoted

inactivation of the JNK signaling pathway through the upregulation

of miR-133a, which inhibited the proliferation, metastasis and

invasion, and induced the apoptosis of MG63 osteosarcoma cells | MG63 osteosarcoma

cells | (89,121) |

|

| Inhibited the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and reduced breast cancer cell

proliferation and EMT-mediated migration and invasion | Breast cancer

cells | (122,123) |

|

| Moesin is the

target of miR-133a-3p, miR-133a-3p negatively regulates MSN; APS

attenuated PD-L1-mediated immunosuppression through the

miR-133a-3p/MSN pathway | HCC | (124) |

| Removal and

inhibition of free radicals | Increased

superoxide dismutase activity, reduced malondialdehyde content, and

scavenged reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species

generated by intracellular oxidative stress, but also reduced free

radical generation | - | (127) |

| Reversal or escape

of MDR | Inhibited TGF-β1

overexpression-mediated EMT, and suppressed the proliferation of

cisplatin-resistant A549 cell xenograft tumors | A549-cell

transplanted tumors | (131) |

|

| Induced apoptosis

in GC cells and enhanced the pro-apoptotic effect of adriamycin on

GC cells; APS acted as a chemotherapeutic sensitizer to a certain

extent | GC cells | (95) |

|

| Induced apoptosis

in HL-60/A cells, activated the caspase cascade reaction,

significantly decreased the expression of MDR-associated protein

and increased the concentration of intracellular antitumor

drugs | HL-60/A cells | (132) |

|

| Improved the

sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, such as

apatinib, escaped MDR and strengthened the antitumor effect | - | (133) |

|

| Increased the

expression levels of IL-6 and TNF-α, and decreased the expression

of IL-10, P-glycoprotein and MDR1. | H22 hepatocellular

carcinoma mice | (134) |

|

| APS enhanced the

antitumor effect of adriamycin and the sensitization effect of

chemotherapy drugs |

|

|

|

| Activated the JNK

signaling pathway and enhanced the sensitivity of SKOV3 cells to

cisplatin | SKOV3 cells | (135) |

|

| Promoted

gefitinib-resistant cell apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation

and migration; inhibited the PD-L1/SREBP-1/EMT signaling pathway,

increased E-cadherin expression, decreased N-cadherin and vimentin

protein expression, and reversed acquired resistance to gefitinib

in lung cancer cells | Lung cancer

cells | (136) |

Regulation of M1/M2 macrophage

polarization

Macrophages develop from bone marrow precursor cells

and serve an important role in the immune system. They are present

in almost all tissues of the body, and they directly phagocytose

and kill foreign pathogens. In addition, they can activate

lymphocytes or other immune cells in the body to indirectly respond

to pathogens, and protect tissues and organs from foreign pathogens

(32). Macrophages are classified

into M1 and M2 types. M1 macrophages, as classically activated

macrophages, produce nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species

(ROS), inducible NO synthase and a large number of pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IL-1β, interferon (IFN)-γ and TNF-α, which

participate in the positive immune response. M1 macrophages also

have a role in phagocytosis and tumor cell killing (33).

By contrast, M2 macrophages, as alternatively

activated macrophages, produce a large number of anti-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13, which suppress the immune

response to a certain extent. Tumor cells selectively recruit bone

marrow-derived macrophages to differentiate into M2 macrophages,

that is, tumor-associated macrophages (34), which promote tumor cell

proliferation, neovascularization, invasion and metastasis

(35). Adjustment of M1/M2

macrophage polarization is key to improve the effectiveness of

antitumor therapy. In an experimental study in mice with non-small

cell lung cancer (NSCLC), APS modulates the Notch signaling

pathway, promotes the production of IL-6, TNF-α and iNOS cytokines,

activates M1 macrophages, inhibits macrophage M2-type polarization,

and enhances phagocytosis and tumor cell killing (36). Bioinformatics analysis indicates

that APS may remodel the tumor microenvironment (TME) and influence

cell-cell interactions, specifically through modulation of

macrophage M2 polarization and CD8+ T cell exhaustion, thereby

overcoming DDP resistance (37).

Li et al (38) reported

that APS can increase the proportion of M1 macrophages in

hepatocellular carcinoma cell-derived xenograft tumors, reduce

macrophage M2-type polarization and inhibit the proliferation of

hepatocellular carcinoma tumor cells. Furthermore, APS improves the

energy metabolism of mouse macrophages in vivo, and enhances

the phagocytic activity of RAW 264.7 monocyte macrophages and the

immune response in mice (39,40).

Mouse macrophages activated by APS are triggered through the

Toll-like receptor (TLR)4-mediated signaling pathway; this

activation event results in the upregulation of the levels of

phosphorylated (p)-p38, p-ERK1/2 and p-JNK. Concurrently, it

induces the degradation of IκB-α and the subsequent translocation

of NF-κB. Eventually, these molecular events culminate in the

production of TNF-α, IL-6 and NO, thereby exerting an inhibitory

effect on the proliferation of mouse tumor cells (41,42).

Li et al (43) demonstrated

that APS enhances the proliferation and phagocytic functions of

mouse macrophages, increases the peripheral blood levels of IL-2,

TNF-α and IFN-γ, and improves the ability of macrophages to

phagocytose tumor cells and inhibit the proliferation of tumor

cells. Therefore, APS may enhance macrophage phagocytosis and tumor

cell killing, and inhibit tumor cell proliferation and metastasis

by increasing M1 macrophage activity, regulating M1/M2-type

macrophage polarization and altering the levels of immune

cytokines.

Induced activation of DCs

DCs are derived from bone marrow CD34+

hematopoietic stem cells and are a specialized class of

antigen-presenting cells, which are divided into immature DCs

(imDCs), mature DCs (mDCs) and regulatory DCs, in accordance with

the different stages of cell differentiation (44). ImDCs capture tumor antigens and are

stimulated to differentiate into mature mDCs. The mDCs migrate to

draining lymph nodes via lymphatic vessels, where they present the

antigens to T cells. They secrete various co-stimulatory molecules

such as CD80, CD86, CD40 and CD70, which further activate effector

T cells, thereby inducing and maintaining anti-tumor immunity

(45,46). Enhancing the function of DCs and

promoting T-cell activation in patients with cancer are an

effective means of antitumor immunotherapy. APS promotes DC

maturation, enhances DC antigen-presenting ability, improves the

accuracy of tumor cell killing and inhibits tumor cell

proliferation (47). When DCs are

induced to mature further, the expression of the DC surface

co-radical molecules CD80 and CD86 are enhanced. DCs present

antigens to T lymphocytes, T lymphocytes increase IL-12 and IFN-γ

secretion, improve antitumor immunity and inhibit the proliferation

of tumor cells (48).

APS induces the DC cell surface molecule CD80, CD86

and IL-12 expression through the TLR2/4 receptor-mediated MyD88

signaling pathway, increases T lymphocyte activity, releases more

IL-2 and enhances antitumor ability (49,50).

APS nanoparticles have been shown to modulate the TLR-mediated

signaling pathway to activate DCs, to increase the expression

levels of co-stimulatory molecules on the surface of DCs and

enhance their tumor cell antigen-presenting ability. Subsequently,

DCs migrate rapidly to lymph nodes, activate the initial T

lymphocytes at lymph nodes and inhibit secondary lymph node tumor

growth (51). Furthermore, after

APS treatment, DCs have been shown to promote the proliferation of

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in mice with breast

cancer, and a DC-based antitumor vaccine can increase the

expression levels of CD40, CD80 and CD86 molecules on the surface

of DCs, and inhibit the growth and metastasis of breast cancer

cells (52). APS induces

morphological changes, the expression of activation markers and the

upregulation of inflammatory cytokines in human blood

monocyte-derived DCs. In addition, APS promotes the activation of

blood DC antigen (BDCA)1 and BDCA3 peripheral blood dendritic cells

(pBDCs), which results in the proliferative activation of T cells

(53). Therefore, APS may induce

the activation of DCs, increased the expression levels of

co-stimulatory factors on the surface of DCs, and accelerate the

maturation of DCs and antigen presentation. Subsequently, this may

enhance the proliferation and activation of CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells, and thus the activation of immune function

under the stimulation of cytokines, thereby effectively inhibiting

the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells.

Reduced activity of MDSCs

MDSCs are a group of heterogeneous cells derived

from the bone marrow; the number of MDSCs in the peripheral blood

and spleen is small, accounting for only 4% of cells (54). Under pathological conditions, these

immature myeloid-derived heterogeneous cells stop differentiating

and become immunosuppressive MDSCs (55,56).

MDSCs promote tumor cell survival, angiogenesis, and invasion and

metastasis to healthy tissues.

APS inhibit MDSC activity, promote MDSC

differentiation and reduce MDSC population. The underlying

mechanisms represent a current research hotspot in immunotherapy

(51). APS suppress MDSC

generation and reduce the MDSC population in the spleens of

tumor-bearing mice. Concurrently, APS downregulates

immunosuppressive cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β) while upregulating

pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α), thereby enhancing

overall immune function (57).

Ding et al (58) revealed

that APS exert a marked regulatory effect on gut microbiota. APS

effectively remodels the gut microbiota environment, and elevates

the levels of glutamate and creatine metabolites. Notably,

glutamate and creatine serve crucial roles in controlling tumor

growth. Simultaneously, APS contributes to the reduction in the

number of MDSCs. Furthermore, in mice with melanoma, APS has been

shown to curtail the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs, as

manifested by decreased expression levels of Arg-1, IL-10 and

TGF-β; this series of changes bolsters the cytotoxic capacity of

CD8+ T cells against tumor cells. Consequently, this

previous study demonstrated that the tumor inhibition rate in mice

with melanoma was significantly increased, highlighting the

potential of APS in antitumor regulation. APS has been reported to

effectively reduce the level of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in

the peripheral circulation of lung cancer, continuously improve

immune function, and increase the overall clinical treatment

efficacy (59). As a common

malignant tumor, lung cancer has shown an increasing trend in

morbidity and mortality in recent years (60). Multi-targeted, low-toxicity Chinese

medicines intervene in the ‘pre-metastatic niche’, a potentially

effective means of preventing and treating tumor metastasis. APS

has been reported to inhibit the formation of the lung

pre-metastatic niche and suppress the recruitment of lung MDSCs.

Mechanistically, the expression of S1PR1, STAT3 and p-STAT3 in the

S1PR1/STAT3 signaling pathway have been shown to be inhibited by

APS, which interferes with the S1PR1/STAT3 signaling pathway and

inhibits the accumulation of MDSCs in the pre-metastatic niche to

achieve antitumor effects (61).

Therefore, APS promote the rapid differentiation of MDSCs, reduce

the number and activity of MDSCs, influence the release of immune

cytokines, enhance immune functions, and inhibit the proliferation

and metastasis of tumor cells.

Reversal of Th1 to Th2 conversion

T lymphocytes develop from bone marrow pluripotent

stem cells, differentiate and mature under the induction of thymic

hormone, and become immunologically active T cells, playing

antitumor specific immunity. T lymphocytes are classified into CD4+

T and CD8+ T cells in accordance with their surface molecular

types. CD4+ and CD8+ are the two functionally different

subpopulations of T lymphocytes. CD4+ T cells are also known as

helper T cells, which play a role in assisting the induction of

body immunity. Th cells are differentiated into functional

subpopulations such as Th1 cells, Th2 cells, and Th17 cells. The

main functional subpopulation of CD8+ T cells is cytotoxic T

lymphocytes. Th1 cells secrete IL-2 and TNF-α and stimulate the

development of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. TNF-α, which stimulates the

activation of macrophages and NK cells, also secretes IFN-γ to kill

tumor cells. Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10, which assist

B lymphocytes to produce specific antibodies and participate in

humoral immunity. Under normal circumstances, the number of Th1 and

Th2 cells remains relatively balanced. However, in patients with

tumor, a transformation from Th1 cells to Th2 cells occurs, which

suppresses the body's cellular immunity. APS enhances the

expression of Th1 cytokines such as IL-2 and IFN-γ in the spleen

tissues of mice with lung cancer through the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB

signaling pathway while reducing the expression of Th2 cytokines,

including IL-4 and IL-10. It also regulates the ratio of Th1/Th2

cells, reverses the transformation from Th1 to Th2, improves the

immunity of mice with lung cancer, and inhibits the growth of tumor

cells (62). APS not only improves

the immune organ index in mice with lung cancer, but also increases

the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T cells in mouse serum and enhances cellular

immune activity (63,64). APS protects immune organs,

regulates the ratio of CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocyte subpopulations, and

inhibits the growth of mouse tumors in vivo; APS also

activates antitumor immune cells, promotes the tumor

microenvironment of anaerobic metabolism, and effectively induced

apoptosis in tumor cells (65).

APS increases the number of allogeneic T lymphocytes and the

expression level of IL-12 and IFN-γ. In addition, cytotoxic T

lymphocytes activated by sensitized DCs kill tumor cells (66). APS reverses Th1-to-Th2 conversion,

maintains Th1/Th2 cell balance, regulates CD4+/CD8+ T cell ratio

and T cell-related cytokine expression, enhances cellular immunity,

and inhibits tumor growth.

Suppression of regulatory T cells

(Tregs)

Tregs are a group of T lymphocytes that can regulate

the immune response and maintain immune tolerance. Tumor

immunotherapy reduces the number of Tregs, inhibits their cellular

activity, maintains immune function of the body and achieves the

killing effects against tumor cells. DCs are a key target for Tregs

to inhibit the tumor immune response (67), and Tregs interact with

tumor-associated CD11c+ DCs to reduce the expression of

DC co-stimulatory ligands and inhibit T-cell proliferation.

Conversely, the clearance of Tregs leads to the restoration of

CD11c+ DC immunogenicity, co-stimulatory ligand

expression and CD8+ T-cell activation, which in turn

inhibits tumor growth (68).

APS has been reported to reduce the number of Tregs,

decrease the expression levels of splenic TGF-β and IL-10, and

inhibit the proliferation and metastasis of malignant melanoma

tumor cells in mice (69). APS

also repairs cytokine imbalance, inhibits forkhead box protein P3

expression, and suppresses Treg activity and function (70). Through the CXCR4/CXCL12 signaling

pathway, APS has been shown to inhibit the recruitment of Tregs by

stromal cell-derived factor-1, and to attenuate the proliferation

and migration of Tregs. Furthermore, APS activates the

TLR4-mediated signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting the expression

of TGF-β, decreasing the number of Tregs and sustaining the killing

effect of immune cells on tumor cells (71). APS significantly enhanced the PBMC

proliferation, reduced Treg frequency, decreased anti-inflammatory

cytokines including IL-10, TGF-β, and VEGF-A, and increased the

pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 (72). Therefore, APS may inhibit Treg

activity by reducing the number of Tregs and their cytokine

secretion, thus restoring and maintaining the normal immune

function of T lymphocytes, achieving the killing effect of T cells

on tumor cells, and inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis.

Enhanced NK cell killing activity

NK cells are derived from bone marrow lymphoid stem

cells, which are important members of the lymphocyte family, and

they are not controlled by high-resolution antigen specificity. NK

cells can rapidly recognize and remove heterogeneous cells, and the

degree of attenuation in vivo is closely related to the

malignant progression of tumors (73). NK cells secrete cytokines, regulate

adaptive immunity and kill tumor cells, and they have killing and

inhibitory effects on hepatocellular carcinoma, NSCLC, breast

cancer and ovarian cancer cells (74–77).

APS has been reported to inhibit the proliferation of leukemia

cells by activating MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A

molecules on the surface of leukemia cells, and enhances the

sensitivity of HL-60 cells to NK cell killing activity and inhibit

leukemia cell growth (78).

Low-molecular-weight APS can protect the immune organs of mice with

hepatocellular carcinoma and stimulate NK cells to kill tumor

cells. In addition, APS promotes the proliferation of splenic

lymphocytes, increases the activity of NK cells and enhances the

immune response of rats with cancer (79,80).

Antitumor effects of APS

Inhibition of tumor cell

proliferation

Tumor cell proliferation primarily aggravates cancer

progression, and pharmacological intervention in tumor cell

proliferation serves an important role in tumor therapy. F-box and

WD-40 structural domain protein 7 (FBXW7) is a classical tumor

suppressor, the translation of which is inhibited by microRNA

(miR)-27a in ovarian cancer cells. APS inhibits the proliferation

of ovarian cancer cells through the miR-27a/FBXW7 signaling

pathway, revealing the therapeutic potential of APS for ovarian

cancer (81). Lung cancer is the

second most common and the deadliest type of cancer worldwide.

Clinically, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common

pathological type of lung cancer (82). APS can inhibit the proliferation

and migration of NSCLC cells, and its mechanism of action is

related to the regulation of the miR-195-5p signaling pathway; in

addition, APS inhibits the lung cancer cell cycle and improves the

morphology of lung cancer cells (83,84).

APS inhibit TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

in A549/DDP cell xenografts of lung adenocarcinoma, which is

associated with inhibition of PI3K/Akt pathway protein activation

(85). In a study exploring the

synergistic inhibitory effect of APS and cisplatin on the growth of

human carcinoma nasopharyngeal cell (CNE), APS was shown to exert

an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of nasopharyngeal

carcinoma cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner, and the

combined application of APS and cisplatin could inhibit the

migration and invasion of CNE-1 cells, which was more effective

than the use of either drug alone with regard to the antitumor

effect of either drug (86). In

addition, the study demonstrated that APS at varying concentrations

inhibited the proliferation of human colorectal cancer SW620 cells,

inducing SW620 cell cycle arrest predominantly at the G2/M phase

(87). In addition, APS can

markedly inhibit the proliferation and invasion of prostate cancer

(PCa) cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Under APS

treatment, the cellular triacylglycerol and cholesterol levels of

patients were revealed to be markedly reduced, and APS can regulate

the miR-138-5p/SIRT1/SREBP1 pathway in PCa to inhibit lipid

metabolism and tumorigenesis (88). Furthermore, APS enhances the

expression of miR-133a in MG63 osteosarcoma cells, inhibits the JNK

signaling pathway, the proliferation, migration and invasion of

MG63 cells, and induces the apoptosis of MG63 cells (89).

Inducing tumor cell apoptosis

Apoptosis is a type of programmed cell death

regulated by various genes, which serves an important role in

tumorigenesis and development (90). The occurrence of malignant tumors

is due to the uncontrolled and excessive proliferation of tumor

cells. In recent years, promoting the apoptosis of tumor cells has

become a focus of research for the treatment of tumors. There are

two main apoptotic pathways: i) The extrinsic pathway, which is

mediated by the activation of caspases through the cell membrane

death receptor; and ii) the intrinsic pathway, which is mediated by

mitochondria in the cytoplasm that release apoptotic factors and

activate caspases. These activated caspases degrade the key

proteins in the cell, causing apoptotic cell death. The genes and

proteins that have been studied include caspase-3, caspase-8,

caspase-9, the Bcl-2 family and cyclooxygenase-2 (91). In the mitochondrion-mediated

intrinsic apoptotic pathway, proteins belonging to the Bcl-2 family

alter mitochondrial membrane permeability, regulate cytochrome

c release and modulate the apoptotic process (92). Bax and Bcl-2 belong to the Bcl-2

superfamily, which are key genes in the regulation of apoptosis,

and they are in a balanced state in normal organisms. Notably,

apoptosis can be induced by a decrease in the expression levels of

the apoptosis inhibitory protein Bcl-2, or an increase in the

expression levels of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax (93).

APS markedly promotes the anti-proliferative and

apoptotic effects of cisplatin on nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells,

by regulating the expression levels of Bax/Bcl-2, caspase-3, and

caspase-9 (94). APS also markedly

decreases gastric cancer (GC) cell viability, and accelerates GC

cell apoptosis in a time- and dose-dependent manner; these effects

are associated with an increase in p-AMPK. APS-treated MGC-803

cells have been shown to exhibit the typical morphological features

of apoptosis, alongside cell cycle arrest at the S phase (95). A novel cold-water-soluble

polysaccharide (APS4) was isolated from Astragalus

membranaceus, induce mitochondria-dependent apoptosis, which is

associated with intracellular ROS accumulation, mitochondrial

membrane potential imbalance, increased

pro-apoptotic/anti-apoptotic Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and cytochrome

c release (96).

The Notch signaling has an important role in the

transformation and proliferation of human malignant tumors, and it

is readily activated in human non-small cell lung carcinoma,

whereas the inhibitors of Notch signaling can attenuate cell

proliferation and induce apoptosis in lung cancer cell lines. APS

has been shown to inhibit the expression of Notch1 and Notch3 in

NSCLC cell lines to upregulate the pro-apoptotic Bax and caspase 8,

promoting apoptosis in NSCLC cell lines (97-101). APS may also inhibit tumor cells

of A549, MC38 and B16, induce apoptosis and prevent cell

transformation from the G1 phase to the S phase of the

cell cycle, and is associated with the expression of molecules

related to immunogenic cell death and the regulation of immune

cells (102). APS has also been

reported to decrease the number of HepG2 liver cancer cells in

S-phase, and cells were arrested at the G0-G1 and G2-M phases,

block the cellular proliferation cycle and induce apoptosis in

cancer cells (103,104). Wang (105) investigated the role of ERK1/2 in

the promotion of apoptosis in HepG2 cells by APS and found that

caspase-3 activity is increased, ERK1/2 expression is decreased and

APS inhibits the ERK1/2 signaling pathway to promote apoptosis in

tumor cells.

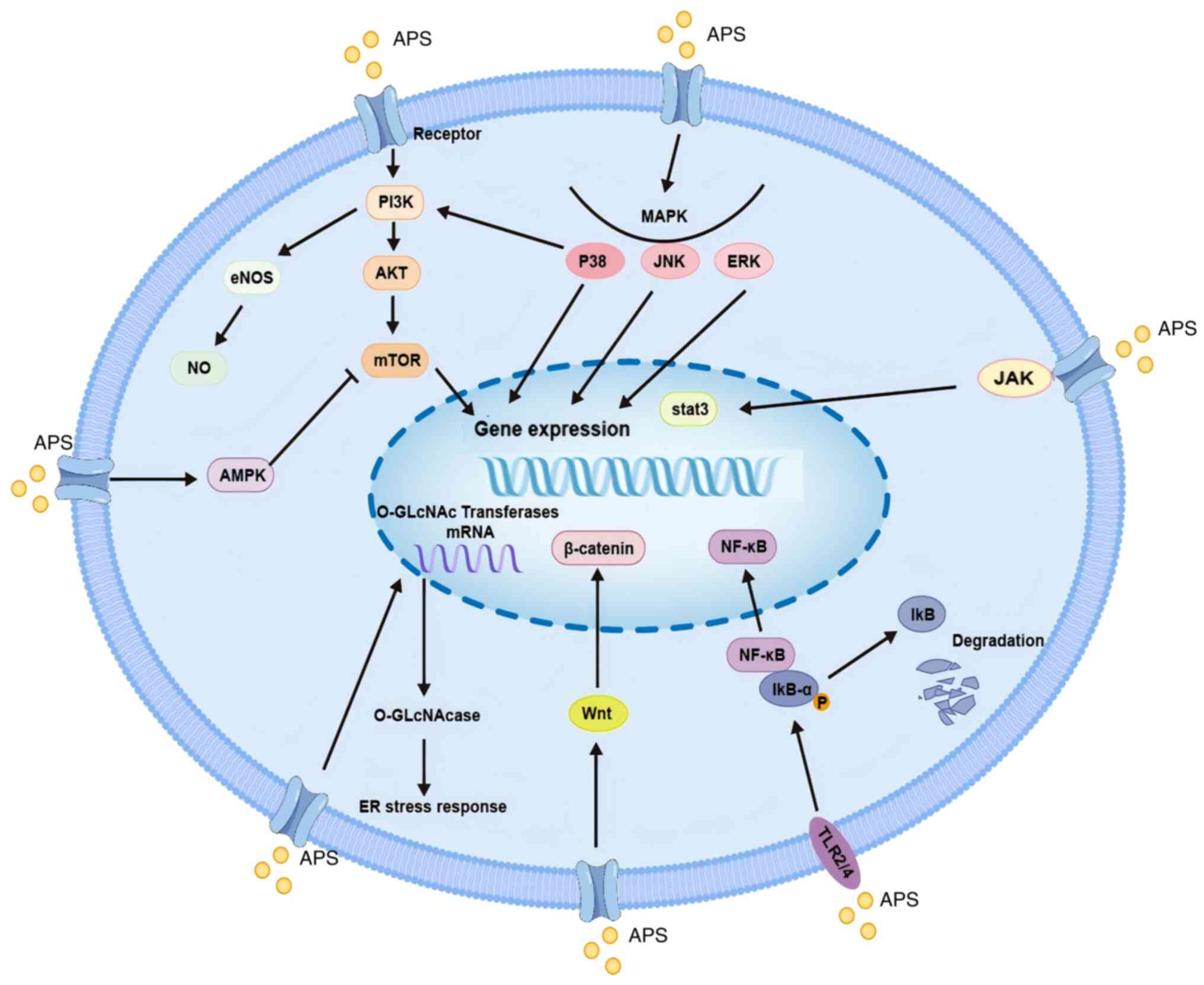

Protein O-GlcNAc modification is a unique

post-translational modification, and various nuclear and

cytoplasmic proteins can be modified by the O-GlcNAcylation

of free hydroxyl groups of selected serine and threonine residues

(106). The cell modification

cycle is mediated by O-GlcNAc transferase, which transfers

N-acetylglucosamine to the protein substrate, and the

O-GlcNAcase enzyme, which removes this modification from the

protein (107–109). O-GlcNAcylation affects a

wide range of protein functions, including transcription,

subcellular localization, protein-protein interactions and protein

stability (110). In numerous

types of cancer, O-GlcNAc modification is associated with

endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and reduced

O-GlcNAcylation leads to the activation of the ER stress

response in a variety of cancer cells (111–113). APS promotes doxorubicin

(Dox)-induced apoptosis and ER stress response in a dose-dependent

manner. In addition, APS decreases O-GlcNAc transferase mRNA

levels and protein stability. and increases O-GlcNAcase

expression level. APS thus reduces O-GlcNAcylation and

promotes Dox-induced apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells,

leading to the exacerbation of ER stress and the activation of

apoptotic pathways (114).

Suppression of tumor cell invasion and

metastasis

Invasion and metastasis are crucial biological

characteristics of malignant tumors, as well as important factors

contributing to tumor recurrence following surgery. Tumor cells

disseminate to new organs and tissues through the blood and

lymphatic systems, subsequently proliferating. Notably, tumor

vasculature serves as a conduit for metastasizing tumor cells;

therefore, inhibiting tumor cell angiogenesis can impede the

progressive deterioration of tumors and aid in the treatment of

neoplastic diseases. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is

widely recognized as a pivotal mediator of tumor angiogenesis

(115). APS effectively inhibits

tumor cell metastasis, with APS efficiently suppressing Lewis lung

cancer growth and metastasis in mice while enhancing immune organ

function. Moreover, it suppresses the protein expression levels of

VEGF and EGFR in tumor tissues, exhibiting a

concentration-dependent relationship (116). The NF-κB signaling pathway has a

critical role in lung cancer prevention and treatment; APS

significantly downregulates NF-κB transcriptional activity, thereby

inhibiting the proliferation and metastasis of A549 and NCI-H358

NSCLC cells (117,118). Furthermore, the angiogenesis of

human colorectal cancer tumors is markedly inhibited by APS, which

is closely associated with the reduction in VEGF expression within

tumor tissues (119). APS can

inhibit the proliferation and invasion of HS-746T cells, suppress

the expression of miR-25 mRNA, and promote the expression of FBXW7

mRNA. It can also reverse the increase in miR-25 and the

suppression of FBXW7 caused by transfection with miR-25 mimic. APS

can inhibit the proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer

HS-746T cells through the miR-25/FBXW7 signaling pathway (120). miR-133, which serves as a tumor

suppressor, inhibits proliferation, migration in tumor cells and

promotes their apoptosis. APS has been shown to upregulate the

expression levels of miR-133a, promote the inactivation of the JNK

signal transduction pathway, and inhibit the proliferation,

metastasis and invasion of MG63 osteosarcoma cells while inducing

apoptosis (89,121). EMT serves a crucial role in tumor

migration and invasion. APS can serve as a therapeutic agent for

breast cancer by inhibiting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to

reduce proliferation and the EMT-mediated migration and invasion of

breast cancer cells (122,123).

Moesin (MSN) serves as a potential biomarker associated with tumor

invasion and metastasis while maintaining PD-L1 stability. In

hepatocellular carcinoma, MSN is targeted by miR-133a-3p, which

negatively regulates its expression; notably, APS attenuates

PD-L1-mediated immunosuppression by modulating the miR-133a-3p/MSN

pathway (124).

Scavenging and inhibiting free

radicals

Under physiological conditions, free radicals

enhance immune function; by contrast, under pathological

conditions, free radicals cause damage to normal tissues and cells,

leading to diseases (125).

Scavenging free radicals is another important tool for tumor

prevention and treatment. The activities of free radical-scavenging

enzymes, such as catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD), are

markedly decreased in patients with tumors, whereas the content of

lipid peroxides and lipid peroxidation products such as

malondialdehyde (MDA) are elevated (126). In addition, the anti-oxidative

stress function is decreased. APS have been reported to reduce free

radical production, increase SOD activity, decrease MDA content,

and scavenge ROS and reactive nitrogen species generated by

intracellular oxidative stress (127).

Reversal or escape of multidrug

resistance (MDR)

In patients with cancer who are receiving

chemotherapy, most treatment failures or deaths are attributed to

tumor MDR (128). Modern

pharmaceutical research focuses on drugs that can reverse or escape

MDR, and the key to reversing tumor drug resistance lies in

blocking the MDR pathway, reducing drug efflux and improving the

chemosensitivity of tumor cells (129). APS markedly increases tumor

response to chemotherapeutic drugs and reverses the MDR effect,

while reducing the toxicity response induced by chemotherapeutic

drugs (130). APS can also

inhibit TGF-β1 overexpression-mediated EMT, and inhibit the

proliferation of cisplatin-resistant A549 cell xenograft tumors

(131). In vitro

experiments confirmed that APS induces apoptosis in GC cells and

enhances the pro-apoptotic effect of Adriamycin on GC cells, and

that APS serves as a chemotherapeutic sensitizer to a certain

extent (95). In addition, in the

HL-60/A cell line with high drug resistance, APS induces apoptosis,

activates the caspase cascade reaction, decreases the expression

levels of MDR-associated protein and increases the concentration of

intracellular antitumor drugs (132). Furthermore, APS increases the

sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic drugs, such as

apatinib, escapes MDR and strengthens the antitumor effect

(133). In the experimental study

using H22 hepatoma cell xenograft mouse models, the expression

levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were increased, whereas those of IL-10,

P-glycoprotein and MDR1 were decreased in the APS treatment group.

In addition, APS was shown to enhance the antitumor effect of

Adriamycin (134). APS can also

serve as a chemosensitive enhancer by activating the JNK signaling

pathway and enhancing the sensitivity of SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells

to cisplatin (135). Furthermore,

APS has been shown to enhance the sensitivity of HeLa cervical

cancer cells to cisplatin chemotherapy by upregulating the

autophagy-related protein beclin1, promoting the conversion of LC3

I to LC3 II, and downregulating the marker protein p62 to enhance

the autophagic activity of HeLa cells (133). APS promotes the apoptosis of

gefitinib-resistant cells, and reduces cell proliferation and

migration. Moreover, APS inhibits the PD-L1/SREBP-1/EMT signaling

pathway, increases the expression levels of E-cadherin, reduces the

expression levels of N-cadherin and vimentin, and reverses the

acquired resistance of lung cancer cells to gefitinib (136).

Summary and outlook

Astragalus membranaceus has a medicinal

history of >2,000 years in China. As an active ingredient with

the highest content in Astragalus membranaceus, APS has

shown great application potential in regulating the tumor

microenvironment and improving immunity. Numerous previous

experimental studies have confirmed that APS can regulate the

activation of immune cells and the release of cytokines in the

tumor microenvironment, as well as inhibit tumor immune escape. The

combination of APS and chemotherapeutic drugs may alleviate the

adverse reactions of patients after chemotherapy and improve their

quality of life, which provides great reference for the use of APS

as an adjuvant in clinical antitumor medication. APS also has

certain effects on the treatment of other diseases, such as

diabetes and inflammatory diseases (137). Therefore, the therapeutic use of

APS for the treatment of other diseases requires further

exploration.

The structure of APS is complex; thus, its

bioavailability can be further improved through chemical means,

such as structural modification, so that it can serve a better

targeted role in cancer. Although APS has been proven to have good

application potential in antitumor immunity, it still faces a

number of problems: i) The structure of APS is complex, and it

contains a large number of chemical components. Its extraction,

separation, purification and structural analysis are currently the

biggest challenges, which require further in-depth exploration. ii)

Tumor immune escape is a complex process in the tumor

microenvironment. Tumor cells can not only directly affect the

function of immune cells, but also indirectly inhibit immunity by

regulating immune checkpoints and cytokines. Although APS can

improve the function of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment,

the specific mechanism by which APS regulates immune cells remains

unclear. iii) At present, most of the studies on the antitumor

effect of APS immunotherapy are limited to cell experiments or

in vivo experiments using mice, and evidence from

clinical-related trials is lacking. Therefore, more abundant

clinical trials are needed for verification. In conclusion, the

research on the mechanism of action of APS in regulating immune

cells, improving the tumor immune microenvironment and resisting

tumors, as well as further research on the mechanism by which APS

serves a regulatory role in the immunotherapy of malignant tumors,

is of great importance to the research and development of clinical

antitumor drugs. This research may improve the treatment of

tumor-related diseases by combining traditional Chinese and Western

medicine.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82173996).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

ZQ, ZW and YW conceived and designed the study. ZQ

wrote the manuscript. YW and ZW revised the manuscript. WC and XX

conducted literature organization and proofreading Data

authentication is not applicable. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 73:17–48.

2023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liu Y, Zhao Y, Song H, Li Y, Liu Z, Ye Z,

Zhao J, Wu Y, Tang J and Yao M: Metabolic reprogramming in tumor

immune microenvironment: Impact on immune cell function and

therapeutic implications. Cancer Lett. 597:2170762024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Xie D, Wang N, Chen Z, Liu Z, Zhou Z, Zeng

J, Zhong Y and Wang Z: Medication Rules and Core Formula Analysis

of Famous National Traditional. Chinese Medicine Masters for Cancer

Treatment Based on Data Mining World Chin Med. 15:2726–2734.

2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

4

|

He Z, Liu X, Qin S, Yang Q, Na J, Xue Z

and Zhong L: Anticancer mechanism of Astragalus

polysaccharide and its application in cancer immunotherapy.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 17:6362024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

National Pharmacopoeia Commission:

Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China (Part 1).

Pharmaceutical Science and Technology Press. (Beijing, China).

3632020.(In Chinese).

|

|

6

|

Su HF, Shaker S, Kuang Y, Zhang M, Ye M

and Qiao X: Phytochemistry and cardiovascular protective effects of

Huang-Qi (Astragali Radix). Med Res Rev. 41:1999–2038. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tong X: The Pharmacology Study of Active

Constituents from Astragalus. Lishizhen Medicine and Materia

Medica Research. 22:1246–1249. 2011.(In Chinese).

|

|

8

|

Xiao M, Chen H, Shi Z and Rui W: Rapid and

reliable method for analysis of raw and honey-processed

Astragalus by UPLC/ESI-Q-TOF-MS using HSS T3 columns. Anal

Methods. 6:8045–8054. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Liao J, Huang J, Liu W, Liao S, Chen H and

Rui W: Effects of total flavonoids and astragalosides of

honey-processed Astragalus on NO secretion levels. J

Guangdong Pharm Univ. 33:162–166. 2017.(In Chinese).

|

|

10

|

Huang J, Liao J, Liu W, Liao S, Feng Y,

Chen H and Rui W: Establishment of determination method for three

main active ingredients of honey-processed Astragalus in rat urine

based on UPLC/Q-TOF-MS. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 28:2564–2567.

2017.(In Chinese).

|

|

11

|

Zhong RZ, Yu M, Liu HW, Sun HX, Cao Y and

Zhou DW: Effects of dietary Astragalus polysaccharide and

Astragalus membranaceus root supplementation on growth

performance, rumen fermentation, immune responses, and antioxidant

status of lambs. Animal Feed Sci Technol. 174:60–67. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zeng P, Li J, Chen Y and Zhang L: The

structures and biological functions of polysaccharides from

traditional Chinese herbs. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 163:423–444.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fan X, Li K, Yang Y, Li H, Li X and Qin X:

Research Progress on structural characterization of astragalus

polysaccharides. J Shanxi Coll Tradit Chin Med. 23:260–267.

2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

14

|

Synytsya A and Novák M: Structural

diversity of fungal glucans. Carbohydr Polym. 92:792–809. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lin MG, Yang YF and Xu HY: Chemical

structure of Astragalus polysaccharide MAPS-5 and its in

vitro lymphocyte proliferative activity. Chin Tradit Herbal Drugs.

40:1865–1868. 2009.(In Chinese).

|

|

16

|

Fang SD, Chen Y, Xu XY and Ye C: Studies

on the Active Principles of Astragalus Mongholicus Bunge I.

Isolation, Characterization and Biological Effect of its

Polysaccharaides. Chin J Org Chem. 2:26–31. 1982.(In Chinese).

|

|

17

|

Huang Q, Lu G, Li Y, Guo J and Wang R:

Studies on the polysaccharides of “Huang Qi” (Astragalus

Mongholicus Bunge.). Acta Pharm Sin. 17:200–206. 1982.(In

Chinese).

|

|

18

|

Tang Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhao H and Shen

Y: Isolation and Structural Feature Analysis of Astragalus

Polysaccharides. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 25:1097–1100.

2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

19

|

Cao Y, Li K, Qin X, Jiao S, Du Y, Li S and

Li X: Quality evaluation of different areas of Astragali Radix

based on carbohydrate specific chromatograms and immune cell

activities. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 54:1277–1287. 2019.(In

Chinese).

|

|

20

|

Liu W, Yu X, Xu J, et al: Isolation,

structural characterization and prebiotic activity of

polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus. Food Ferment

Ind. 46:50–56. 2020.(In Chinese).

|

|

21

|

Bergman PJ: Cancer immunotherapies. Vet

Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 49:881–902. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rui R, Zhou L and He S: Cancer

immunotherapies: Advances and bottlenecks. Front Immunol.

14:12124762023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Helmy KY, Patel SA, Nahas GR and Rameshwar

P: Cancer immunotherapy: Accomplishments to date and future

promise. Ther Deliv. 4:1307–1320. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A, Mendelsohn

RB, Shia J, Segal NH and Diaz LA Jr: Immunotherapy in colorectal

cancer: Rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 16:361–375. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Lei X, Lei Y, Li JK, Du WX, Li RG, Yang J,

Li J, Li F and Tan HB: Immune cells within the tumor

microenvironment: Biological functions and roles in cancer

immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 470:126–133. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Katz JB, Muller AJ and Prendergast GC:

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in T-cell tolerance and tumoral immune

escape. Immunol Rev. 222:206–221. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Velcheti V and Schalper K: Basic overview

of current immunotherapy approaches in cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol

Educ Book. 35:298–308. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wang Z, Li M, Bi L, Hu X and Wang Y:

Traditional Chinese medicine in regulating tumor microenvironment.

Onco Targets Ther. 17:313–325. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kong F, Chen T, Li X and Jia Y: The

current application and future prospects of Astragalus

polysaccharide combined with cancer immunotherapy: A review. Front

Pharmacol. 12:7376742021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhou L, Liu Z, Wang Z, Yu S, Long T, Zhou

X and Bao Y: Astragalus polysaccharides exerts

immunomodulatory effects via TLR4-mediated MyD88-dependent

signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 7:448222017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Huang WC, Kuo KT, Bamodu OA, Lin YK, Wang

CH, Lee KY, Wang LS, Yeh CT and Tsai JT: Astragalus

polysaccharide (PG2) ameliorates cancer symptom clusters, as well

as improves quality of life in patients with metastatic disease,

through modulation of the inflammatory cascade. Cancers (Basel).

11:10542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Bonnardel J and Guilliams M: Developmental

control of macrophage function. Curr Opin Immunol. 50:64–74. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Li M, Yang Y, Xiong L, Jiang P, Wang J and

Li C: Metabolism, metabolites, and macrophages in cancer. J Hematol

Oncol. 16:802023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi

L and Allavena P: Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment

targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:399–416. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mantovani A and Allavena P: The

interaction of anticancer therapies with tumor-associated

macrophages. J Exp Med. 212:435–445. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Wei W, Li ZP, Bian ZX and Han QB:

Astragalus polysaccharide RAP induces macrophage phenotype

polarization to M1 via the notch signaling pathway. Molecules.

24:20162019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen R, Li Y, Zuo L, Xiong H, Sun R, Song

X and Liu H: Astragalus polysaccharides inhibits tumor

proliferation and enhances cisplatin sensitivity in bladder cancer

by regulating the PI3K/AKT/FoxO1 axis. Int J Biological

Macromolecules. 311:1437392025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li C, Pan XY, Ma M, Zhao J, Zhao F and Lv

YP: Astragalus polysacharin inhibits hepatocellular

carcinoma-like phenotypes in a murine HCC model through repression

of M2 polarization of tumour-associated macrophages. Pharm Biol.

59:1531–1537. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Li SY, Li K, Qin XM, Li XR and Du YG:

Study on active constituents of Astragalus polysaccharides

for injection to regulate metabolism of macrophages based on LC-MS

metabolomics. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 51:1575–1585. 2020.(In

Chinese).

|

|

40

|

Feng S, Ding H, Liu L, Peng C, Huang Y,

Zhong F, Li W, Meng T, Li J, Wang X, et al: Astragalus

polysaccharide enhances the immune function of RAW264.7 macrophages

via the NF-κB p65/MAPK signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 21:202021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Shao BM, Xu W, Dai H, Tu P, Li Z and Gao

XM: A study on the immune receptors for polysaccharides from the

roots of Astragalus membranaceus, a Chinese medicinal herb.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 320:1103–1111. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Wei W, Xiao HT, Bao WR, Ma DL, Leung CH,

Han XQ, Ko CH, Lau CB, Wong CK, Fung KP, et al: TLR-4 may mediate

signaling pathways of Astragalus polysaccharide RAP induced

cytokine expression of RAW264.7 cells. J Ethnopharmacol.

179:243–252. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Li W, Hu X, Wang S, Jiao Z, Sun T, Liu T

and Song K: Characterization and anti-tumor bioactivity of

Astragalus polysaccharides by immunomodulation. Int J Biol

Macromol. 145:985–997. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lin W, Liu T, Wang B and Bi H: The role of

ocular dendritic cells in uveitis. Immunol Lett. 209:4–10. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Villar J and Segura E: Decoding the

heterogeneity of human dendritic cell subsets. Trends Immunol.

41:1062–1071. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chudnovskiy A, Pasqual G and Victora GD:

Studying interactions between Dendritic Cells and T cells in vivo.

Curr Opin Immunol. 58:24–30. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Bamodu OA, Kuo KT, Wang CH, Huang WC, Wu

ATH, Tsai JT, Lee KY, Yeh CT and Wang LS: Astragalus

polysaccharides (PG2) enhances the M1 polarization of macrophages,

functional maturation of dendritic cells, and T cell-mediated

anticancer immune responses inpatients with lung cancer. Nutrients.

11:22642019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Jing XN, Qiu B, Wang JF, Wu YG, Wu JB and

Chen DD: In vitro anti-tumor effect of human dendritic cells

vaccine induced by Astragalus polysacharin: An experimental

study. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 34:1103–1107. 2014.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Gu Y, Pu X, Yin N and Wan C: The study on

mechanism of the anti-tumor effect of Fufang Huangqi Oral Solution

combined chemotherapy. J Tianjin Univ Tradit Chin Med. 41:85–89.

2022.(In Chinese).

|

|

50

|

Bian Y, Zhang J, Wang L, Wang X, Zhang K,

Wang X, Meng J and Li J: Progress of research on the effect of

Astragalus polysaccharide on the morphology and function of

dendritic cells. Prog Vet Med. 37:86–89. 2016.(In Chinese).

|

|

51

|

Pang G, Chen C, Liu Y, Jiang T, Yu H, Wu

Y, Wang Y, Wang FJ, Liu Z and Zhang LW: Bioactive polysaccharide

nanoparticles improve radiation-induced abscopal effect through

manipulation of dendritic cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces.

11:42661–42670. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Chang WT, Lai TH, Chyan YJ, Yin SY, Chen

YH, Wei WC and Yang NS: Specific medicinal plant polysaccharides

effectively enhance the potency of a DC-based vaccine against mouse

mammary tumor metastasis. PLoS One. 10:e01223742015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

An EK, Zhang W, Kwak M, Lee PC and Jin JO:

Polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus elicit T cell

immunity by activation of human peripheral blood dendritic cells.

Int J Biol Macromol. 223:370–377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lasser SA, Ozbay Kurt FG, Arkhypov I,

Utikal J and Umansky V: Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer

and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 21:147–164. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Xia L, Zhao S, Wei Q and Xu X: Study on

changes of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor tissues of

tumor-bearing mice and its significance. Curr Immunol. 34:232–236.

2014.(In Chinese).

|

|

56

|

Hao WB, Xiang FF, Liu QL, Yue HK and Kang

XD: Research adances of myeloid inhibitory cells in tumor

microenvironment. Immunol J. 33:729–732. 2017.(In Chinese).

|

|

57

|

Chai W, He X, Zhu J, Lv C, Zhao H, Lv A

and Yv C: Immunoregulatory effects of astragalus polysaccharides on

myeloid derived suppressor cells in B16-F10 tumor bearing mice.

Chin J Basic Med Tradit Chin Med. 18:63–65. 2012.(In Chinese).

|

|

58

|

Ding G, Gong Q, Ma J, Liu X, Wang Y and

Cheng X: Immunosuppressive activity is attenuated by

Astragalus polysaccharides through remodeling the gut

microenvironment in melanoma mice. Cancer Sci. 112:4050–4063. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Mei Q, Zhang W, Ran R and Wang J: Effect

of astragalus polysaccharide on peripheral circulation MDSC in lung

cancer and its clinical effect. Modern Doctor. 55:10–13. 2017.(In

Chinese).

|

|

60

|

Li Y, Yan B and He S: Advances and

challenges in the treatment of lung cancer. Biomed Pharmacother.

169:1158912023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Shen M, Wang YJ, Liu ZH, Chen YW, Liang

QK, Li Y and Ming HX: Inhibitory effect of Astragalus

polysaccharide on premetastatic niche of lung cancer through the

S1PR1-STAT3 signaling pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2023:40107972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Liu Y, Yuan J, Guo M, Zhang Y, Lu J and

Cao W: Effect of astragalus polysaccharides based on

TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway on immune function of lung

cancer mice and its regulatory effect on Th1/ Th2. Chin J Immunol.

37:676–682. 2021.(In Chinese).

|

|

63

|

Li K, Li S, Wang D, Li X, Wu X, Liu X, Du

G, Li X, Qin X and Du Y: Extraction, characterization, antitumor

and immunological activities of hemicellulose polysaccharide from

Astragalus radix herb residue. Molecules. 24:36442019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|