Introduction

In patients with glioblastoma (GB), overall survival

(OS) remains poor despite advances in diagnostic precision

(1) and targeted therapies

(2,3). Standard therapy for patients in good

clinical condition consists of tumor biopsy/resection followed by

radiotherapy with temozolomide chemotherapy yielding a median

overall survival slightly below 15 months after diagnosis (4). The predominant immune cell population

in GB comprises glioma-associated microglia and macrophages (GAM),

which can originate from brain-resident microglia (GAM-MG) or

monocyte-derived macrophages (GAM-MDM) from the periphery (5–7). The

immune polarization of GAM is complex (8–13)

and the specific role of different microglial subtypes in GB

pathogenesis still only poorly understood with conflicting

prognostic data on the role of the innate immune system (12,14–17).

Moreover, the effects of GB therapy with standard alkylating or

novel targeted treatment approaches on GAM have not been

investigated in detail, while in preclinical brain metastases

models profound effects of tumor-associated innate immune cells on

therapy efficacy have been reported (18,19).

Activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR) pathway is frequently found in GB (20). Enhanced signaling occurs through

amplified and/or mutated receptor tyrosine kinases including the

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), deletion of the tumor

suppressor PTEN and other alterations in the upstream signaling

cascade. The mTOR pathway engages a central role in the regulation

of proliferation, metabolism and other biological processes

important for cell growth proliferation and the adaptation to the

tumor microenvironment (21,22)

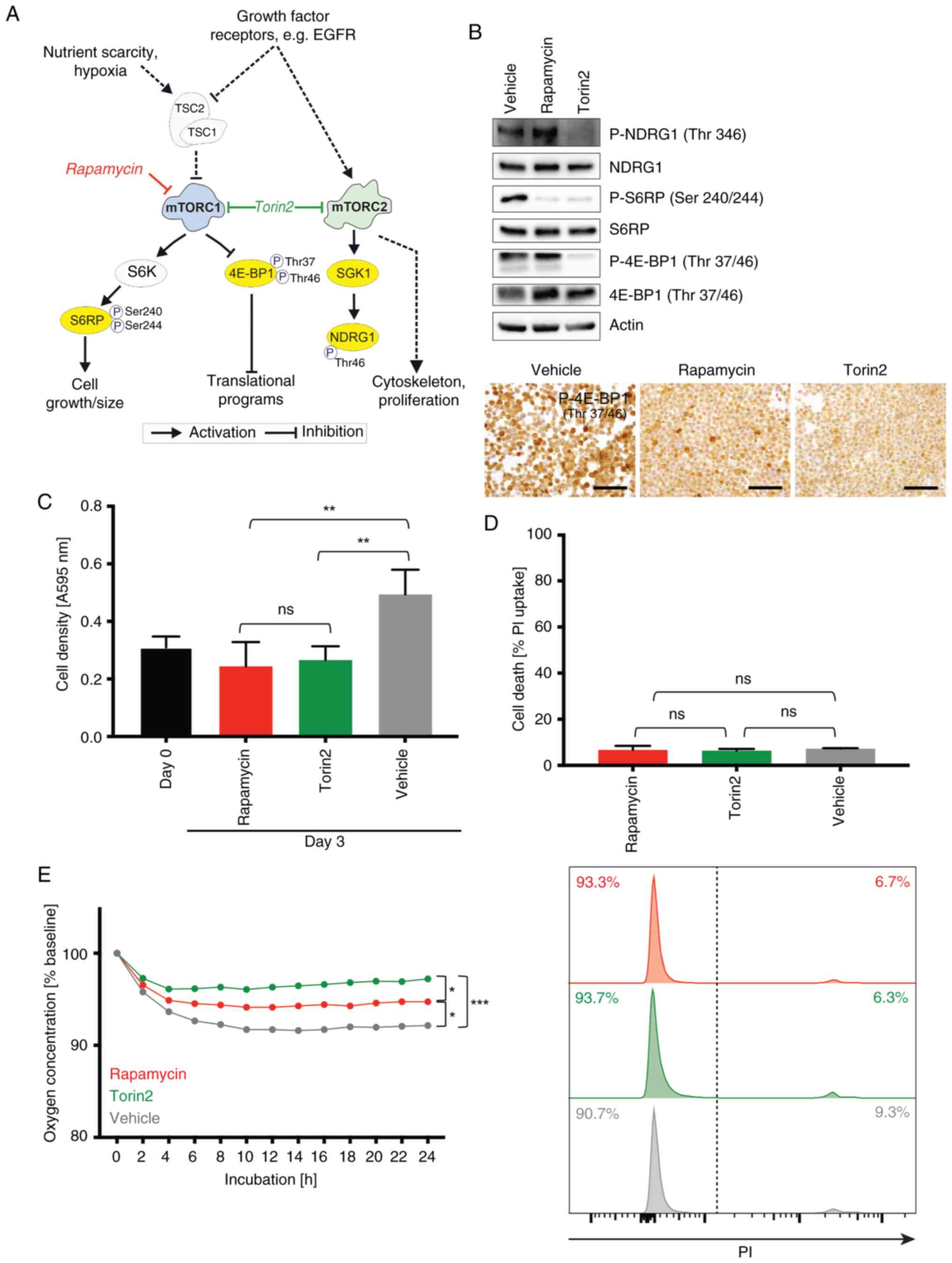

(Fig. 1A). mTOR exists as part of

2 different multiprotein complexes termed mTOR complex 1 and 2

(mTORC1 and 2) that integrate upstream signals from diverse stimuli

including growth factor receptors but also nutrient and oxygen

availability (23). Important

downstream effects of mTORC1 are mediated through targets that

regulate mRNA translation. For instance, the activation of the

mTORC1 pathway triggers phosphorylation of the eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 (4E-BP1) at the

phosphorylation sites Thr37/Thr46, as well as phosphorylation of

the S6 ribosomal protein (S6RP) at Ser240/244 via S6-kinase (S6K).

mTORC2 signaling is less well understood and plays important roles

in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton as well as regulation of

proliferation (23). mTORC2

targets include the glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1), which

in turn activates N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) through

phosphorylation of Thr346 (24).

4E-BP1 phosphorylation is to some degree resistant to

first-generation mTORC1 inhibitors such as rapamycin and its

derivatives, while second-generation mTOR inhibitors including

torin2 effectively induce dephosphorylation of 4E-BP1 (Fig. 1A) (25). Taken together, EGFR and its

downstream target mTOR are plausible targets for therapeutic

intervention that have been extensively studied in various cancers,

including GB (3,21,22,26).

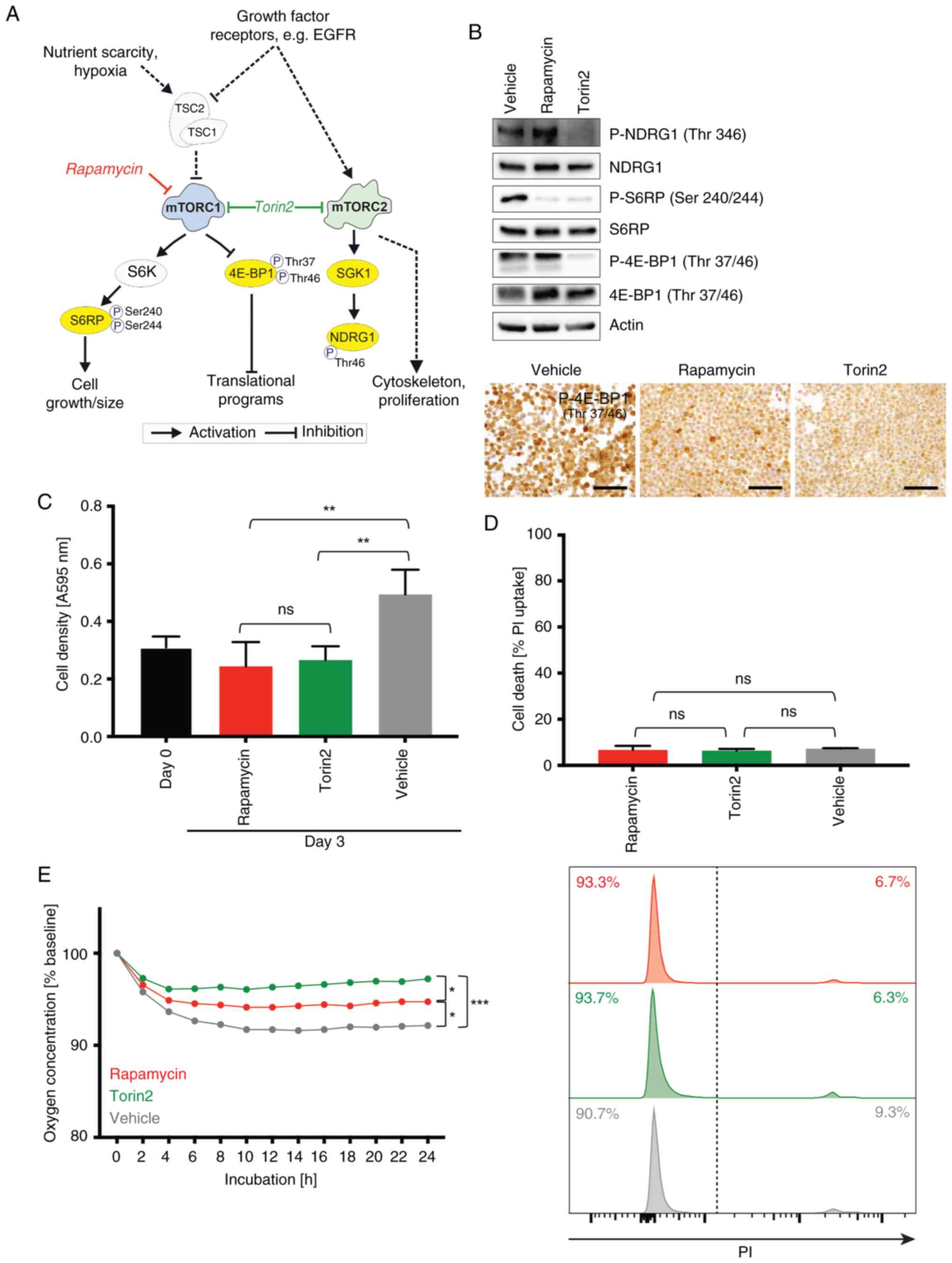

| Figure 1.Impact of pharmacological mTOR

inhibition on basal functions of human microglia cell lines. (A)

Overview of the mTOR pathway and targets of the mTOR inhibitors

investigated in this study. Scheme adapted from (33). (B) C20 cells were incubated with

100 nM rapamycin, 100 nM torin2 and vehicle control for 24 h.

Protein lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies for

NDRG1, P-NDRG1 (Thr346), S6RP, P-S6RP (Ser240/244), 4E-BP1,

P-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) and actin as well as by immunocytochemistry

stainings of P-4E-BP1 (scale bar, 100 µm) of C20 cell pellets

incubated with 100 nM rapamycin, 100 nM torin2 and vehicle control

for 24 h. (C-E) C20 microglia cells were treated with 100 nM

rapamycin (red), 100 nM, torin2 (green) or vehicle control (grey).

(C) Crystal violet staining was used to quantify cell density at

baseline (day 0, after a 24 h attachment period prior to any

treatment intervention, black) and after 72 h of exposure to the

respective treatment conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD

(n=4; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons test). (D) Cell

death was quantified by PI FACS after 72 h. Data represent mean ±

SD (n=3; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparisons test).

Histograms were depicted. (E) Quantification of oxygen by a

fluorescence-based assay was performed in C20 cells during 24 h

treatment. Oxygen consumption is shown relative to the start of the

experiment as mean (n=3) every hour; treatment groups were then

compared at timepoint 24 h (n=3; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple

comparisons test). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ns,

not significant; PI, propidium iodide; SD, standard deviation;

NDRG1, N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1; P-, phosphorylated; S6RP,

S6 ribosomal protein; 4E-BP1, 4E-binding protein 1. |

However, despite the biological rationale and

consistent activation of this pathway, clinical trials with mTOR

inhibitors in GB have so far only produced only weak and sometimes

even antagonistic signals in unselected GB patient cohorts

(3,27). Therefore, the results of biomarker

selected GB cohorts treated with mTOR inhibition (mTORi) in

multi-arm trials are eagerly awaited. The NCT Neuro Master Match

trial (N2M2, NOA-20) investigated temsirolimus-based mTORi in newly

diagnosed GB with upregulated mTOR signaling in bulk tumor tissue

(28), while the GBM AGILE trial

is testing paxalisib-based PI3K/mTORi in newly diagnosed or

recurrent tumors (29).

Additionally, several resistance mechanisms to mTORi in the complex

GB microenvironment, such as protection of tumor cells from

hypoxia-induced cell death or from temozolomide chemotherapy have

been reported (21,22,30,31).

Furthermore, biomarkers of mTOR activity could indicate a

subpopulation of GB patients more prone to benefit from mTOR

inhibitor treatment (26,32).

Interestingly, mTORC1 not only drives GB cell growth

and proliferation (21), but also

shows significant activity in GAM in vivo, as reflected by

the analysis of phosphorylation status of the mTOR target proteins

4E-BP1 and S6RP (33). The

regulation of peripheral innate immune cell functions by mTOR has

been extensively studied (34,35).

For example, the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin can enhance

pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages (35). Also, various effects of mTORi on

tumor-associated macrophages in peripheral cancers have been

identified (36). In contrast, the

role of mTOR signaling for innate immune functions in the central

nervous system (CNS) and specifically MG and GAM has not been

understood in detail, yet. In certain preclinical models, mTOR

inhibition has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects on MG

during stroke (37,38) or aging (39) and to suppress LPS-induced

proinflammatory cytokine production (40). In contrast, in the context of

glioma, mTOR inhibition showed a pro-inflammatory GAM phenotype in

a rat glioma model (41) as well

as a reduced expression of anti-inflammatory markers in cell

culture (42). Additionally, the

landmark paper of Dumas et al (43) identified mTOR regulation in GAM-MG

(as opposed to GAM-MDM) as a central mechanism for glioma

progression with a correlation of mTOR activity and effector immune

evasion in the GB microenvironment. Genetic inactivation of mTORC1

in GAM-MG had anti-tumor effects and reduced glioma growth,

suggesting a prognostic relevance of mTOR signaling specifically in

microglia (43). Furthermore, we

previously reported that GB patients with higher levels of GAM had

improved OS when EGFR/mTOR signaling was targeted (within the OSAG

101-BSA-05 trial) (26). These

findings support the hypothesis that GAM could be a promising

target for a precision mTORi approach in GB. The aim of our study

was to further investigate the properties of GAM under

pharmacological mTORi compared to standard chemotherapy in GB.

Materials and methods

Reagents, cell lines and culture

conditions

A split of passage three of the human C20 MG cell

line was kindly provided in 2017 by Dr. David Alvarez-Carbonell

from the Department of Molecular Biology and Microbiology at the

Case Western Reserve University (10900 Euclid Ave., SOM WRT 205,

Cleveland, Ohio 44106, USA). The C20 cell line has the advantage

that it was generated from primary human MG obtained from fresh CNS

cortical tissue of adult patients by magnetic cell sorting

(44). Negativity for human

viruses (including HIV, HCV, HBV) in C20 cells was confirmed. The

resulting classification as biosafety level 1 of the C20 by the

department for biological safety of the University Hospital

Frankfurt was approved by the local authority (Regierungspräsidium

Gießen, Central regional council of Hesse). The human microglial

clone 3 cell line HMC3 was purchased from the ATCC (45) and originally derives from human

embryonic MG (46). LNT-229 cells

were a kind gift of Dr. Nicolas de Tribolet from the Department of

Neurosurgery and Laboratory of Brain Tumor Biology and Genetics

(Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois and University of

Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland) (47). No passage number was available for

LN-229 cells that are amongst the most widely spread glioblastoma

cell lines. LNT-229 glioma cells differ from LN-229 cells in having

retained wild-type p53 status (48). LNT-229 cells were authenticated

using short tandem repeat analysis (Multiplexion, Heidelberg,

Germany) and the STR profile of LNT-229 cells matched with the

known profile for LN-229 (49).

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM)

containing 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Life

Technologies, Darmstadt Germany) and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)

(Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany). All reagents not specified were

purchased from Sigma/Merck.

Transwell co-cultivation of microglia

and glioma cells as an in vitro GAM model

Transwell co-cultivation of the human MG cell lines

C20 or HMC3 with the glioma cell line LNT-229 was performed using

6- or respective 24-well cell culture inserts (1 µm pore; Greiner

bio-one, Frickenhausen, Germany). 6-well inserts were used for

experiments with protein and RNA analyses and 24-well inserts for

oxygen consumption analyses. MG were seeded into the lower chamber

(6-well: 500,000/well, 24-well: 120,000/well) and glioma cells into

the inserts (6-well insert: 400,000/well, 24-well insert:

30,000/well) separately in DMEM with 10% FCS 24 h prior to

co-cultivation. To provide a MG monoculture control condition, C20

or HMC3 MG were seeded into the inserts and lower chambers.

Cultivation was performed in serum-free DMEM with a total volume of

3 ml/500 µl or 2 ml/200 µl added to the well and insert (6-/24-well

plate, respectively). Cultured cells were treated with the mTOR

inhibitors 100 nM rapamycin and 100 nM torin2 as well as 400 µM

temozolomide or corresponding vehicle controls for 24 h. Rapamycin

and torin2 concentrations were selected based on previous studies

in glioblastoma cells demonstrating effective target inhibition

without cytotoxicity (21,25). Treatment durations were designed to

allow for steady-state cellular adaptation and to model prolonged

drug exposure, approximating clinical administration schedules of

mTOR inhibitors and temozolomide over a continuous period. The

temozolomide condition was used as a control to enable comparison

between the effects of standard GB chemotherapy and mTORi

treatment. After the incubation period, C20 or HMC3 cells in the

lower chamber were harvested for further analyses (RNA sequencing,

immunoblot, human cytokine array or oxygen consumption).

Cell density and viability assays

Cell density was assessed by crystal violet staining

as previously described (50)

after treatment of C20 or HMC3 with 100 nM rapamycin and 100 nM

torin2 as well as vehicle controls for 72 h in serum-free medium or

DMEM with 10% FCS. Cell viability measurement using propidium

iodide (PI) uptake and flow cytometry was performed as previously

described (21).

Oxygen consumption

After 24 h Transwell cultivation in mono- or

co-culture condition (see above), oxygen consumption was assessed

during 24 h treatment of C20 or HMC3 with 100 nM rapamycin, 100 nM

torin2 or vehicle control. Plates with oxygen sensors (Oxo Dish

OD24, PreSens, Regensburg, Germany) were used to quantify oxygen

consumption. Airtight conditions were achieved by covering with

sterile paraffin oil as previously described (22). Fluorescence-based measurement of

oxygen consumption was performed in triplicates.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) was performed in C20 or

HMC3 cells after treatment with 100 nM rapamycin and 100 nM torin2

as well as a vehicle control. Paraffin embedded cell pellets were

prepared as previously described (33). Pellets were cut in slices of 3 µm

thickness using a microtome (Leica Microsystems, Nussloch GmbH,

Nussloch, Germany) and placed onto SuperFrost slides (Thermo

Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). mTORi was investigated according to

the phosphorylation status of the mTORC1 target protein 4E-BP1

using the phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) antibody diluted 1:1,000

(236B4; Cell Signaling). ICC was performed according to

standardized protocols of the Leica BOND-III automated stainer

(Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and stainings were analyzed using a light

microscope (BX41, Olympus, Hamburg, Germany).

Protein isolation and immunoblot

analysis

Protein lysates were prepared using lysis buffer P

followed by a determination of protein concentration by

Bradford-Assay to analyze equal amounts of protein loading of each

sample as previously described (51). Electrophoretic separation of the

denatured proteins was performed on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels

followed by a blotting process as described previously (12). Membranes were blocked in 1×

Roti-Block blocking buffer (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and then

incubated with antibodies against 4E-BP1 (Cell Signaling),

phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) (236B4; Cell Signaling), S6RP (5G10; Cell

Signaling), phospho-S6RP (Ser240/244) (D68F8; Cell Signaling),

NDRG1 (D8G9; Cell Signaling), phospho-NDRG1 (Thr346) (D98G11; Cell

Signaling) or beta-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as a loading

control. The secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson

ImmunoResearch, USA. Immunodetection was performed by HRP

enzyme-coupled secondary antibodies, which oxidize luminol

(AppliChem GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) resulting in a

chemiluminescent reaction on X-ray films (Super RX, Fujifilm Europe

GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany).

Human cytokine array

After 24 h Transwell cultivation of the MG cell

lines C20 or HMC3 with the glioma cell line LNT-229 in serum-free

DMEM, protein lysates of HMC3 or C20 cells were prepared.

Experiments were performed in biological triplicates and pooled for

a sufficient protein concentration to perform the human cytokine

array according to the manufacturer's protocol (ARY005B, R&D

Systems). The array enables a simultaneously detection of 36

different cytokines, chemokines and acute-phase proteins per sample

(CCL1/I-309, CCL2/MCP-1, MIP-1α/MIP-1β, CCL5/RANTES, CD40

Ligand/TNFSF5, Complement Component C5/C5a, CXCL1/GROα,

CXCL10/IP-10, CXCL11/I-TAC, CXCL12/SDF-1, G-CSF, GM-CSF,

ICAM-1/CD54, IFN-γ, IL-1α/IL-1F1, IL-1β/IL-1F2, IL-1ra/IL-1F3,

IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 p70, IL-13, IL-16,

IL-17A, IL-17E, IL-18/IL-1F4, IL-21, IL-27, IL-32α, MIF, Serpin

E1/PAI-1, TNF-α and TREM-1). The coordinates of the array are

available in the protocol (https://resources.rndsystems.com/pdfs/datasheets/ary005b.pdf?v=20250615).

Immunodetection was performed as described in the section

immunoblot analysis. Quantification was performed by measuring the

pixel density of scanned films using ImageJ software (NIH).

Whole transcriptome analysis

Extraction of total RNA using TRIzol and the

ExtractMe Total RNA Kit (Blirt, Danzig, Poland) was performed as

described previously (22). Paired

end, 150 base pair, sequencing was performed with an Illumina

HiSeq2500 by Genewiz (New Jersey, USA). RNA-sequencing libraries

were generated with the SMART-Seq preparation kit (CloneTech) and

fragmented with the Nextera XT kit (Illumina). The following steps

were performed as previously described (52,53).

Pre-processing of fastq-files of bulk sequenced samples including

filtering for quality scores, poly-A trimming, removal of N

containing reads, artifact removal and clearing of rRNA

contamination was achieved using a pipeline in the HUSAR platform,

provided by DKFZ (Heidelberg, Germany). Transcriptomes were mapped

to the human genome using the genecode annotations (release v. 32;

genome assembly version GRCh38.p13) and TopHat2 (v. 2.0.14)

(54). The number of reads per

gene was determined by HTSeq count. Overlaps were considered as

unique. Further analysis was performed within R (v. 4.1.2),

operating in RStudio (v. 2022.02.0) with BioMart package (v.

2.50.3) and DESeq2 (v. 1.34.0) (55).

Gene expression analyses

Gene annotation and species conversion was done

using the biomaRt R package (v. 2.38.0). For principal component

analysis (PCA) and unsupervised clustering, read counts were

normalized using variance-stabilized transformed (vst) data (‘vst’

function of DESeq2 package which equals log2 transformation),

respecting a base mean >20 and an adjusted P-value of 0.05 (=

FDR 5 %). PCAs were plotted using the ‘autoplot’ function of

ggplot2 package (v. 3.3.5). Heatmaps of the top 2,000 genes were

created with the pheatmap package (v. 1.0.12). Hierarchical

clustering of the top 100 gene loadings of the PCAs was performed

in JMP 16.2.0 by use of the complete linkage variance method. The

first PC obtained by the PCA was used as an ordering column sorting

the clusters by these values.

Gene set enrichment analysis

(GSEA)

GSEA was performed using fgsea R package (v. 1.18.0)

as reported before (53). Genes

with base mean <20 were removed and the remaining genes were

ranked ascendingly based on the log2 fold change. The ranked gene

list was compared against the MSigDB database (v. 7.4) using

‘fgseaMultilevel’ function with the default settings. Normalized

enrichment scores (NES) were used for subsequent heatmaps of the

top 50 Hallmark signatures graphed with JMP 16.2.0.

Statistical analysis and data

visualization

Statistical analyses were conducted using JMP 16.2.0

(SAS, Cary, USA), GraphPad Prism V9 or R (v. 3.5 or v. 4.2.1).

Detailed information on the respective analyses was indicated in

the corresponding figure legend or specific methods section.

Quantitative data were depicted including mean and standard

deviation (SD). Statistically significant P-values were indicated

(*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001). BioRender was used for

illustrations.

Results

Pharmacological inhibition of mTOR

signaling in microglia cell lines

To determine the sensitivity of human MG cell lines

to pharmacological mTORi, the C20 cell line (with the advantage of

having been generated by a cell sorting approach) (44) and the established HMC3 MG cell line

(45,46) were treated with the allosteric

mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin or torin2 that inhibits both mTORC1 and

mTORC2 in an ATP-competitive manner. Both MG cell lines showed a

strong expression of mTOR signaling per se and were sensitive to

treatment with rapamycin and torin2. Treatment with torin2 resulted

in a profound reduction of the phosphorylation of all investigated

target proteins, whereas rapamycin treatment mainly reduced the

signal of S6RP phosphorylation (Fig.

1B). These results are in line with the known effects of the

first generation mTORC1 inhibitors rapamycin and its derivatives in

contrast to second generation mTOR inhibitors like torin2 in glioma

cells (25,33). The assessment of basal MG cellular

functions commonly affected by mTORi with rapamycin and torin2

showed a reduced proliferation (Fig.

1C) without displaying major cytotoxicity (Fig. 1D) and a reduced oxygen consumption

in the MG cell lines (C20 in Fig.

1E, HMC3 in Fig. S1) similar

as previously reported from glioma cell lines with stronger effects

of torin2 (22,25).

Effects of pharmacological mTOR

inhibition on the GAM transcriptome

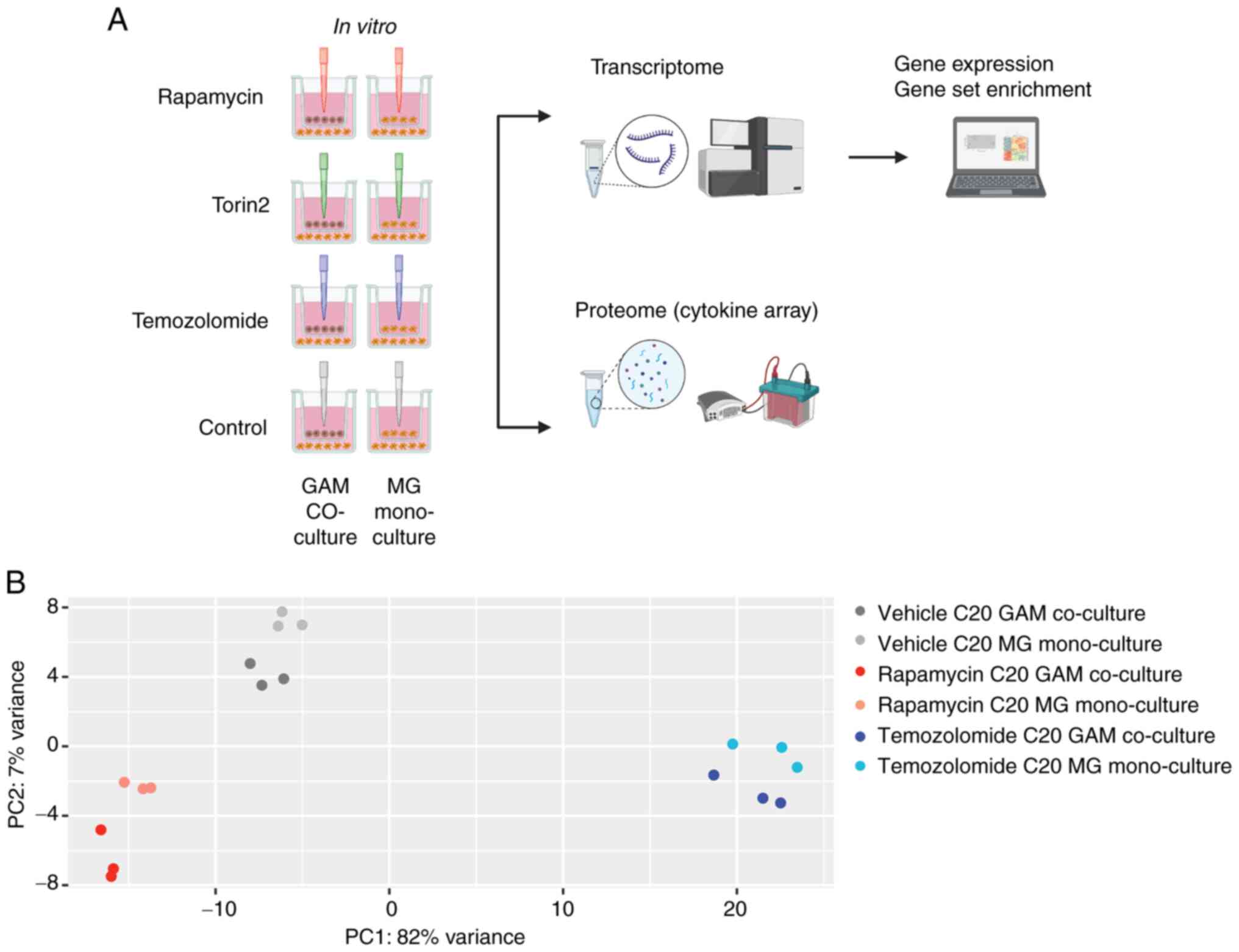

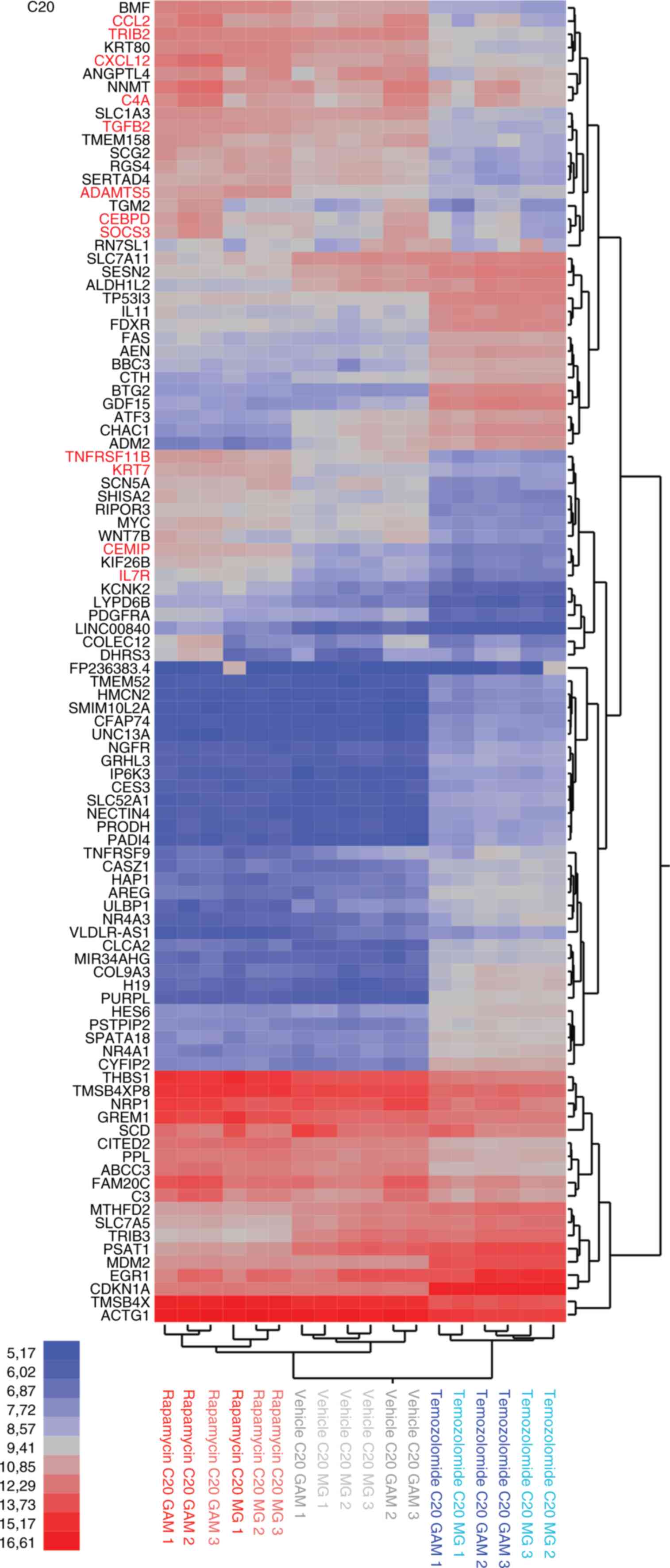

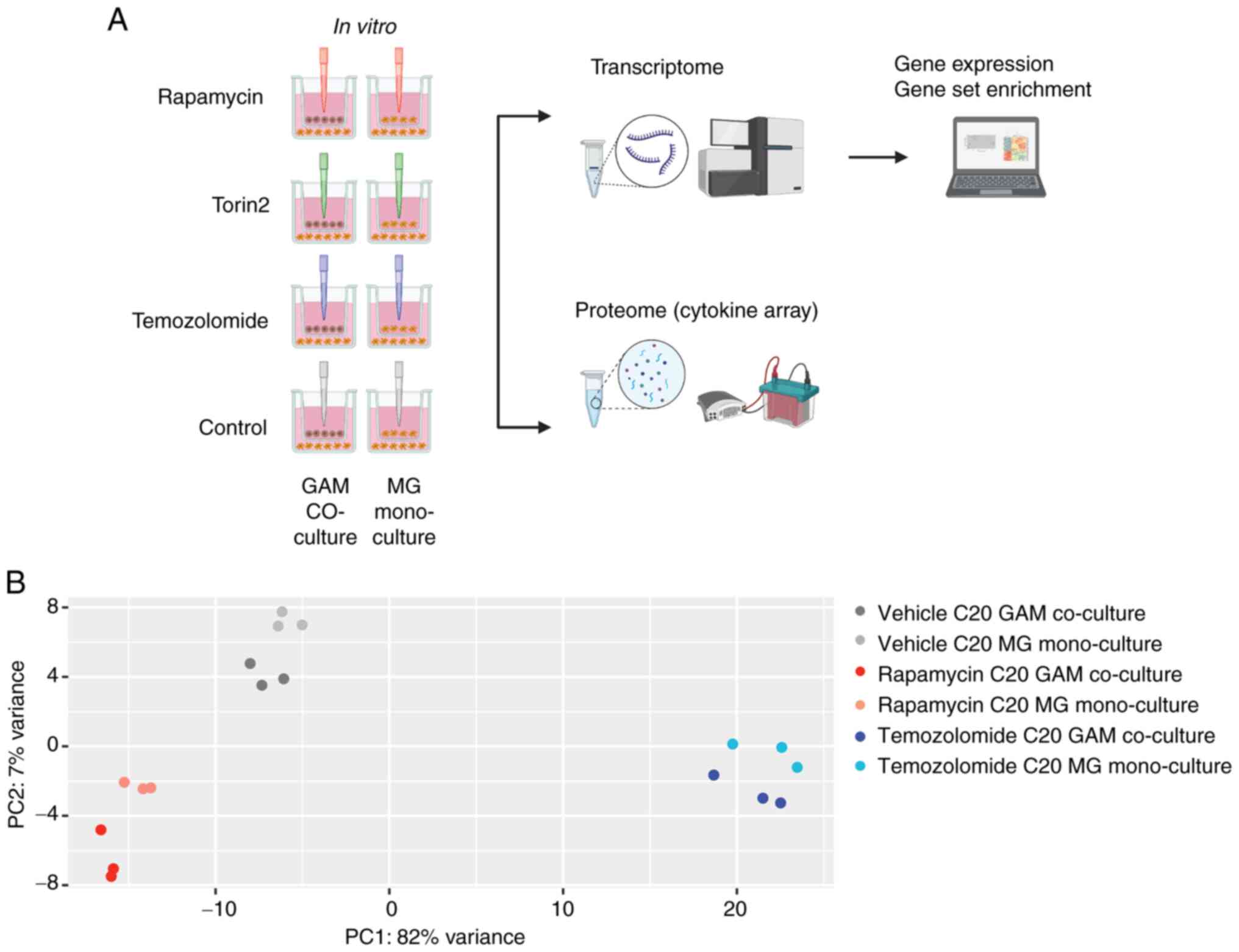

To examine effects of mTORi on the GAM phenotype we

employed a defined co-culture model (Fig. 2A). The C20 or the HMC3 cell line

was cultured either in co-cultivation with the GB cell line LNT-229

(GAM co-culture) or in a monoculture condition with the MG cell

line in both compartments of the well (MG mono-culture). The PCAs

of the entire transcriptome dataset as well as the unsupervised

clustering of the top regulated genes across all conditions

exhibited a discernible C20 or HMC3 signature induced by rapamycin,

which triggered marked differences compared to temozolomide or the

untreated condition (Figs. 2B,

S2, S3A, B). For example, in C20 cells, PC 1

of the PCA primarily differentiated the samples based on

temozolomide treatment, while PC 2 distinguished the samples based

on rapamycin treatment and the culture condition (Fig. 2B). Notably, the pharmacological

treatment with rapamycin or temozolomide had more influence on the

transcriptional phenotype than the presence or absence of glioma

cells (GAM co-culture vs. MG mono-culture condition). These effects

were observed in both the C20 and HMC3 cell lines, although they

were clearer in the C20 cell line (C20 in Figs. 2B, S2; HMC3 in Fig. S3A, B). Effects of co-culturing in

the unsupervised transcriptome-based clustering analysis were most

apparent in the rapamycin treatment condition in the C20 as

compared to the HMC3 cell system (Figs. S2, S3B). Upon analyzing the most

significantly regulated genes, we found that treatment with

rapamycin resulted in increased expression levels of genes

associated with inflammatory processes. These included

pro-inflammatory cytokines, components of the complement system,

and signaling molecules involved in migration and invasion (such as

ADAMTS5, C4A, CCL2, CEBPD, CEMIP, CXCL12, IL7R, KRT7, SOCS3,

TNFRSF11B or TRIB3). Notably, this effect was more

explicit in the GAM co-culture condition compared to the MG

mono-culture condition. In contrast to rapamycin, temozolomide

treatment had a significant impact on genes related to cell death

(such as AEN, BBC3, BTG2 or FAS) (Fig. 3). Also, there was a substantial

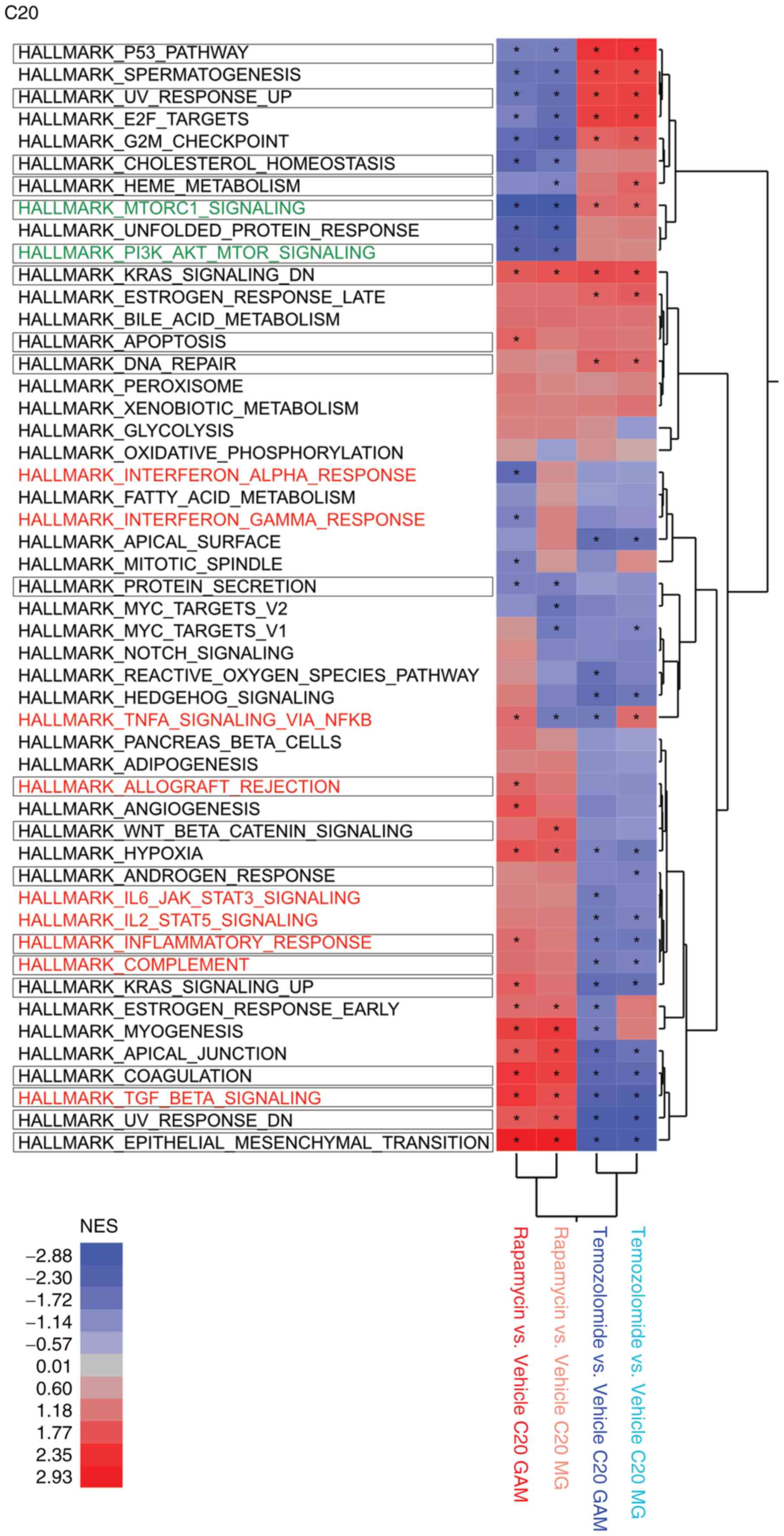

overlap in the top regulated genes of C20 and HMC3 cells (Fig. S4A, B). To gain a broader

understanding of the signaling pathways and gene programs involved,

we conducted GSEA, which corroborated that rapamycin upregulated

key immunogenic hallmark gene sets in both MG and GAM, whereas the

standard alkylating chemotherapy agent temozolomide appeared to be

associated with cell cycle related hallmark gene sets (Fig. 4). As a proof of concept, the GSEA

indicated that the rapamycin-induced phenotype in both MG and GAM

showed reduced mTORC1 signaling (Fig.

4).

| Figure 2.Impact of rapamycin compared with

temozolomide on the GAM transcriptome. (A) Overview on all

treatment conditions used throughout the experimental setup

(created in BioRender, Strecker, M. (2025); http://BioRender.com/wgg6ezp). Temozolomide effects

were only analyzed by RNA sequencing (transcriptome), torin2

co-culture experiments were only analyzed in the cytokine assay.

(B) Gene expression was analyzed in the whole transcriptome dataset

by PCA across all C20 samples including triplicates of the

different treatments (rapamycin, temozolomide and vehicle control)

in the co-culture (C20 microglia with LNT-229 glioma cells) or the

C20 mono-culture condition (bright colors, GAM co-culture of C20

with LNT-229; light colors, MG mono-culture control condition; red,

treatment with 100 nM rapamycin; blue, 400 µM temozolomide; grey,

vehicle control) (biological replicates were labelled 1 to 3). PCA,

principal component analysis; GAM, glioma-associated

microglia/macrophages; MG, microglia. |

Effects of pharmacological mTOR

inhibition on the GAM phenotype

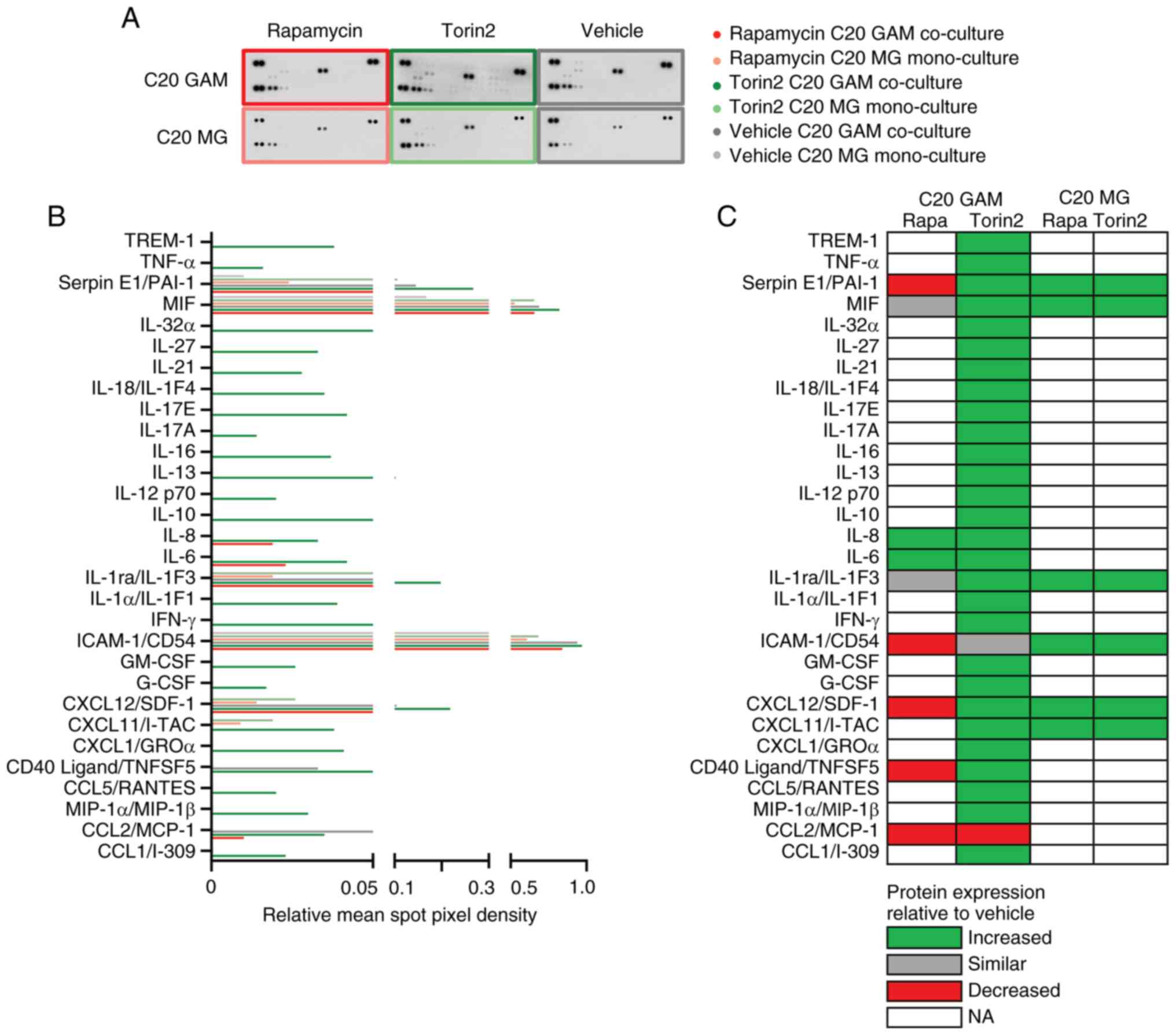

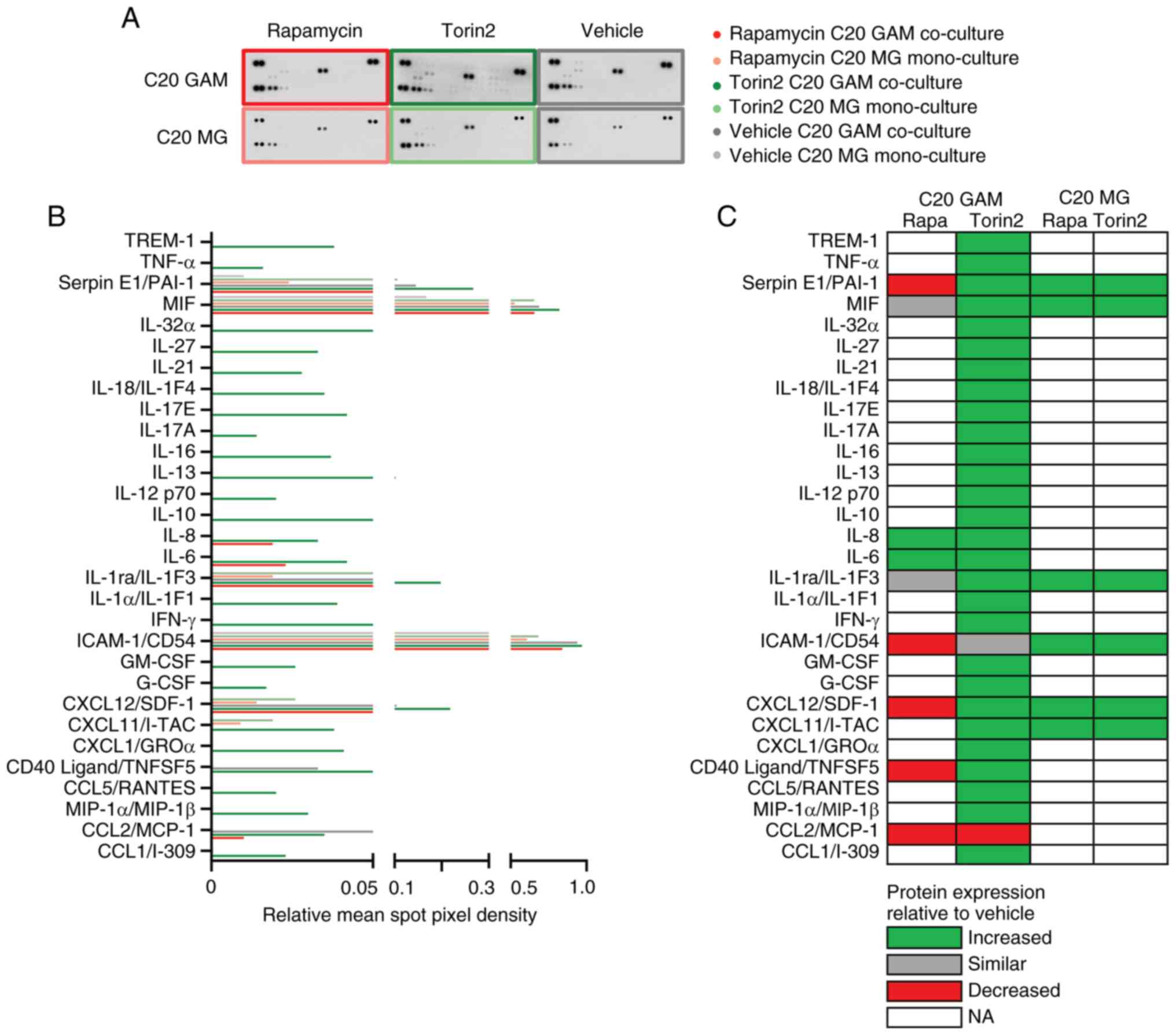

In line with the transcriptome analysis, the human

cytokine array revealed elevated protein levels of pro-inflammatory

cytokines following mTORi by rapamycin or torin2 especially under

co-culture with GB cells (GAM model). Strikingly, torin2 induced 28

whereas rapamycin only 2 out of 36 proteins of the cytokine array

in C20 GAM (Fig. 5). Comparing the

transcriptome (C20: Figs. 3,

4, HMC3: Figs. S5, S6) and cytokine array protein data (C20:

Fig. 5, HMC3: Fig. S7), rapamycin-induced enrichment

for certain gene sets including Hallmark_IL6_JAK_STAT3_signaling

(Fig. 4) could be confirmed by an

increased IL-6 cytokine protein level in the GAM condition in C20

cells (Fig. 5B, C). Comparatively

minor effects were observed in the HMC3 model (Fig. S7). Rapamycin-induced enrichment of

other inflammatory gene sets or immunogenic pathways in GAM in C20

or HMC3 was not traceable in the human cytokine array except for an

upregulation of IL-8 in C20 (Fig. 5B,

C). However, cytokines corresponding to a portion of the gene

sets regulated by rapamycin on the transcriptional level (Fig. 4) could be detected in GAM and/or MG

following treatment with torin2, e.g. TNF-α or IFN-γ signaling

(Fig. 5B, C). When comparing

effects in a microglia mono-culture (MG model) rapamycin and torin2

induced the same cytokines. Both in C20 as well as HMC3 cells these

included macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) as well as

Serpin E1/PAI-1 (Figs. 5C;

S7B).

| Figure 5.Impact of pharmacological mTOR

inhibition on cytokine expression profiles of GAM. (A)

Immunodetection of 36 different cytokines (each in duplicate) per

pooled sample (pool of n=3) incubated with rapamycin, torin2 or

vehicle. (B) Quantification by relative mean spot pixel density for

each cytokine was depicted. (A and B) Bright colors, GAM co-culture

of C20 with LNT-229; light colors, MG mono-culture control

condition; red, treatment with 100 nM rapamycin; green, 100 nM

torin2; grey, vehicle control. (C) Overview of protein expression

in the treatment conditions rapamycin and torin2 compared to

vehicle control in C20 GAM and C20 MG, respectively. Green,

increased; grey, similar; red, decreased; no color, not

analyzable/detectable. GAM, glioma-associated

microglia/macrophages; MG, microglia. |

Discussion

Our study demonstrated a regulation of key

immunogenic pathways in GAM by pharmacological mTORi with rapamycin

and torin2 in a human cell line co-culture model. These findings

are in line with the study by Dumas et al (43) and other pre-clinical glioma models

(41,42), which showed that mTORi in

GAM-microglia reshaped the GB microenvironment towards a

pro-inflammatory and anti-tumorigenic state with effects on

survival in glioma tumor models. Mechanistically, mTORi interfered

with a GB cell-mediated activation of mTOR in GAM microglia which

otherwise promoted an immunosuppressive phenotype that hampered the

anti-tumor adaptive immune response (43). Of note, mTOR inhibition has also

been reported to exert anti-inflammatory effects on MG, e.g. in the

context of stroke or aging (37–39).

Therefore, our observed pro-inflammatory effects in GAM-microglia

might depend on the cellular microenvironment or disease model

which needs to be considered when evaluating mTORi as a

therapeutic. Our previous study identified the GB immune

microenvironment as a potential factor relevant for the response to

therapies targeting EGFR/mTOR signaling in human GB patients

(26). Analyses of the GB patient

cohort of the OSAG 101-BSA-05 trial revealed that higher levels of

GAM in the initial treatment-naïve tissue were associated with

improved OS in patients treated with the anti-EGFR antibody

nimotuzumab (26), despite the

overall negative outcome of the study (of a non-biomarker selected

study population) (56). These

findings (26,43), together with our present study,

support the hypothesis that GAM could pose a co-target for

therapeutic mTORi in GB.

In our study, we investigated the effects of

pharmacological mTORi on GAM and observed overall largely similar

outcomes with both the first generation mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin

and the more potent second-generation ATP-competitive mTOR

inhibitor torin2, which targets both mTORC1 and mTORC2. Because

mTOR besides protein translation affects various other cellular

processes including autophagy and metabolism a longer incubation

period was chosen to allow cellular processes to reach their new

equilibrium. Both inhibitors had similar effects on basal cellular

functions, such as reduced proliferation and oxygen consumption,

also comparable to previous results from mTORi treatment in glioma

cells (22,25), but divergent from effects on immune

cells, like T cells that have been shown to increase oxidative

phosphorylation under rapamycin treatment (57). Our transcriptome analysis revealed

a distinct GAM phenotype triggered by rapamycin-mediated mTORi,

which differed from the profile of temozolomide that-expectably for

a chemotherapeutic agent-mainly triggered cell death and cell cycle

related alterations. Interestingly, at the transcriptional level

rapamycin treatment led to an upregulation of pro-inflammatory

genes and key immunogenic pathways in the GAM co-culture setting

(for example in C20 and HMC3 Hallmark_TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA NFKB) as

well as more general in the GAM and MG setting (for example in C20

the Hallmark_IL6_JAK_STAT3, summarizing the transcriptional

response driven by IL-6 signaling via the JAK/STAT3 pathway), but

also exclusively in the C20 MG mono-culture setting (for example

Hallmark_INTERFERON response genesets). Of note, there was a

substantial overlap in the top regulated genes of C20 and HMC3

cells as well as in the differential gene expression and GSEA

analyses of both cell lines. The overall pro-inflammatory effect of

mTOR inhibition on the GAM and MG profile was supported by protein

level data, which revealed an increase in pro-inflammatory

cytokines following mTORi treatment with rapamycin and torin2

treatment. On protein level, the strongest and most complex effects

were observed in the C20 GAM setting treated with torin2, where

many pro-inflammatory proteins were upregulated. Taken together,

the torin2-induced microglial profile in especially C20 GAM, and

less pronounced C20 MG, indicates an activated, mostly

pro-inflammatory microglial state important for immune cell

recruitment (via chemokines) and modulation of the immune

microenvironment (via for example IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, but also

IL-10, IL-1ra, Serpin E1, MIF). C20 GAM were characterized by the

expression of chemotactic chemokines (CCL1/I-309, MIP-1α (CCL3),

CCL5/RANTES, CXCL1/GROα, CXCL11/I-TAC or CXCL12/SDF-1),

co-stimulatory/immune regulation ligands (CD40 Ligand/TNFSF5,

TREM-1), colony-stimulating growth factors (G-CSF and GM-CSF), type

II cytokines/interferon (IFN-γ), pro-inflammatory interleukins

(IL-1α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12p70, IL-17A, IL-17E, IL-18, IL-21, IL-27,

IL-32α), interleukins linked to T cell differentiation (IL-13,

IL-16), regulatory or mixed interleukins (IL-1ra (IL-1F3), IL-10),

pro-inflammatory mediators linked to invasion and migration (MIF,

Serpin E1 (PAI-1) as well as TNF-α as a central mediator of

inflammation. Beyond this strong torin2-induced upregulation of

pro-inflammatory cytokines in the C20 GAM co-culture setting,

torin2 also induced several, though not all, pro-inflammatory

cytokines in the C20 MG mono-culture. In contrast, rapamycin showed

a partially divergent effect in the C20 GAM co-culture setting

compared to the C20 MG mono-culture setting: Despite a generally

pro-inflammatory signature (e.g., IL-6 and IL-8 upregulation),

rapamycin-treated C20 GAM also displayed a reduced expression of

several cytokines compared to the vehicle control, suggesting a

dampened expression of some cytokines under tumor cell influence.

This divergence between C20 MG mono- and GAM co-cultures was also

apparent in the transcriptomic data, with interferon α/γ response

genes upregulated only in mono-cultures. Notably, cytokines reduced

by rapamycin in C20 GAM, such as ICAM-1 and CD40L, are

interferon-associated, therefore supporting concordant

transcriptomic and proteomic changes. Also, the rapamycin-induced

activation of the Hallmark_IL6_JAK_STAT3_signaling pathway in C20

GAM and MG was supported by increased IL-6 and IL-8 protein levels.

However, some immunogenic pathways enriched at the transcriptomic

level did not show matching protein changes under rapamycin, while

related cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ were detected in GAM

and/or MG after torin2 treatment. Interestingly, in our in

vitro model, MIF exhibited high baseline levels in both MG and

GAM of C20 and HMC3, even under untreated (vehicle) controls and

mTOR inhibition further increased MIF expression in the HMC3 GAM

co-culture setting as well as the C20 microglia mono-culture and

GAM co-culture setting. In HMC3 GAM, rapamycin appeared to exert

even stronger effects than torin2 on the cytokines MIF and Serpin

E1/PAI-1. In contrast, in C20 GAM, torin2 led to a marked

upregulation of both cytokines compared to control conditions.

However, rapamycin treatment in C20 GAM showed lower levels of

Serpin E1 and relatively unchanged MIF expression. Notably,

elevated levels of GAM subtype expressing the MIF receptor CD74

were associated with prolonged OS in patients with IDH-wildtype GB

(12). In this regard, it is

important to mention that the dichotomic categorization of

macrophages as either pro-tumor M1 or anti-tumor M2 (58) has been challenged in microglia and

especially in the brain tumor immune microenvironment. Over the

past decade, complex GAM phenotypes with simultaneous expression of

pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines have been identified and

extensively studied (8–13). Overall, our data suggest that

torin2 more effectively modulates the inflammatory GAM and MG

phenotype than rapamycin, which may have implications for the use

of its derivatives, such as temsirolimus, currently under

investigation in the N2M2 trial (28).

Pro-inflammatory effects of mTOR inhibition in GAM

could be highly relevant, considering the increasing importance of

immunotherapeutic approaches in GB treatment (59–62)

that may be more effective in a pro-inflammatory and

anti-tumorigenic state of the innate GB microenvironment. However,

despite the intriguing findings in our GAM model that provided a

consistent and standardized experimental framework, our study is

limited by its in vitro nature and the use of immortalized

microglia cell lines. Both the C20 and the HMC3 cell line display

overall high similarities but also show distinct context-dependent

differences and therefore offer distinct advantages and limitations

for studying various aspects of microglial biology that researchers

should be aware of. For example, a recent comparative study

analyzing morphology, proteome, and secretome of HMC3 and C20

revealed both shared and distinct responses to inflammatory stimuli

(LPS or IFN-γ). While the baseline proteome of HMC3 was described

as more transcriptionally and metabolically active, the C20

proteome was interpreted as displaying a higher phagocytic

capacity. Upon inflammatory stimulation, HMC3 activated immune and

metabolic pathways, whereas C20 activated mitochondrial besides

immune pathways. Both cell lines secreted IL-6 under LPS treatment

(63). For our experimental

setting in the context of GAM, we considered the newer C20 line,

derived from adult human cortical microglia via magnetic cell

sorting, a more physiologically suitable model than the HMC3 cell

line, derived from human embryonic microglial cells and modified

via SV40-dependent immortalization. Therefore, the HMC3 cell line

was primarily used as a secondary validation model to support the

reproducibility of key findings. The C20 microglia cell line showed

a broader and more robust response to the mTOR inhibitors, whereas

the effects observed in HMC3 cells were less pronounced but

remained largely consistent with those seen in C20 cells. For

example, in the cytokine expression analysis torin2 treatment of

C20 cells (co-cultured with GB cells) yielded 30 different

cytokines while in HMC3 cells only two of the 36 covered cytokines

of the assay were regulated. Although other genetic models

(43) support our findings,

potential off-target effects of mTOR inhibitors cannot be fully

excluded and represent a limitation of our experimental setting. In

this regard, rapamycin is considered an uncommonly specific

inhibitor due to its association with the intracellular adaptor

FKBP12 which then allosterically inhibits mTORC1. Torin2 was

developed as an ATP-competitive inhibitor and off-target effects

are more likely. Torin2 has been shown to potentially interfere

also with signaling from phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) however

with an approximately 800-fold lesser selectivity than for cellular

mTOR. Additionally, torin2 can interfere with signaling from the

kinases ATM, ATR and DNA-PK, however, again with reduced

selectivity in comparison to mTOR (64). Thus, while the major effects of

torin2 observed in our study are most likely due to on-target mTOR

inhibition, some minor contribution of other kinases cannot be

ruled out. Also, treatment durations in our study were chosen to

approximate steady-state cellular adaptation and mimic continuous

exposure to the substances (21,25)

. Nonetheless, shorter or extended treatment periods, not assessed

here, may provide further mechanistic insights. Therefore, future

studies should incorporate genetic models and rescue experiments as

well as a broader variety of treatment durations to confirm the

specificity of the observed effects. Dumas et al (43) supported their preclinical models

employing an in silico analysis in which they could

demonstrate a correlation of enhanced mTOR signaling in

GAM-microglia with reduced effector immune cell infiltration.

Unfortunately, a similar approach was not feasible in our

experimental setting due to a lack of GAM-microglia specific

transcriptome data in publicly available datasets of human GB

patients as well as no in vivo datasets of human GB samples

under mTORi treatment.

Given the recent report on a potential therapeutic

activity of temsirolimus in mTOR-activated GB in the N2M2 trial

(65), human GB tissue samples of

responders vs. non-responders as well as of recurrent tumors after

mTORi treatment might become available in the near future. The

analysis of such samples with a focus on tumor-intrinsic and

microenvironmental features, particularly GAM, would represent an

ideal setting to validate both our in vitro findings and the

effects observed in animal models (43). Ideally, such analyses could be

incorporated into future prospective studies.

In conclusion, our findings support targeting of

mTOR signaling in GAM to promote a favorable state within the GB

microenvironment as a therapeutic approach. Notably, innovative

techniques for even a cell-type specific delivery of therapeutic

agents are currently under development (66). Furthermore, our results stress the

importance of a comprehensive understanding of therapy effects in

the GB microenvironment which is essential for optimizing the

design of treatment combinations and identifying specific patient

subgroups that are more likely to benefit from both established and

novel targeted therapies. Given that mTORC1 activation in bulk

tumor tissue is estimated in approximately 35% of cases (28,32),

a significant proportion of GB patients might be candidates for

mTOR inhibitor therapy. Eagerly awaited initial results of the N2M2

trial reported a benefit from treatment with mTOR inhibition in

mTOR-activated GBs (65)

emphasizing the clinical need for a deeper understanding of

mTOR-mediated effects in the GB immune microenvironment.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Tatjana

Starzetz (Institute of Neurology, Edinger-Institute, Frankfurt,

Germany), for their technical support in performing the

immunocytochemistry stainings.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Mildred Scheel Career Center

Frankfurt (German Cancer Aid Foundation) and the Goethe University

(Frankfurt Research Funding). In addition, the Dr. Senckenberg

Institute of Neurooncology is supported by the Dr. Senckenberg

Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

Bulk RNA sequencing data have been deposited to the

NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus and can be accessed via accession no.

GSE242829 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE242829).

The rest of the data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author

Authors' contributions

PSZ, JPS, PNH, MWR conceived and designed the study.

PSZ, MS, JS, JBW, NIL, BS, BR, KJW, ALL, AB, KHP, LS, JPS, MHM, PNH

and MWR acquired and analyzed the data. PSZ and MS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. PSZ, MS, JPS, MHM, PNH and MWR

drafted the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed and edited the

manuscript and approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JPS has received honoraria for lectures, advisory

board participation, consulting or travel grants from Abbvie,

Roche, Boehringer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medac, Mundipharma,

Servier and UCB. MHM is meanwhile an employee of Sanofi. MWR has

received a research grant from UCB as well as honoraria for

advisory board participation from Alexion and Servier. PSZ, MS, JS,

NIL, JBW, BS, BR, KJW, ALL, AB, KHP, LS and PNH report no

disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

Authors' information

ORCiD: Pia S. Zeiner, 0000-0001-6626-9211; Michael

W. Ronellenfitsch, 0000-0002-1402-6290.

References

|

1

|

Capper D, Jones DTW, Sill M, Hovestadt V,

Schrimpf D, Sturm D, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Chavez L, Reuss DE, et al:

DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system

tumours. Nature. 555:469–474. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Mandel JJ, Yust-Katz S, Patel AJ, Cachia

D, Liu D, Park M, Yuan Y, Kent TA and de Groot JF: Inability of

positive phase II clinical trials of investigational treatments to

subsequently predict positive phase III clinical trials in

glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 20:113–122. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ronellenfitsch MW, Steinbach JP and Wick

W: Epidermal growth factor receptor and mammalian target of

rapamycin as therapeutic targets in malignant glioma: Current

clinical status and perspectives. Target Oncol. 5:183–191. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Stupp R, Mason WP, van Den Bent MJ, Weller

M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, Belanger K, Brandes AA, Marosi C, Bogdahn

U, et al: Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide

for glioblastoma. New Engl J Med. 352:987–996. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bowman RL, Klemm F, Akkari L, Pyonteck SM,

Sevenich L, Quail DF, Dhara S, Simpson K, Gardner EE,

Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, et al: Macrophage ontogeny underlies

differences in tumor-specific education in brain malignancies. Cell

Rep. 17:2445–2459. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Klemm F, Maas RR, Bowman RL, Kornete M,

Soukup K, Nassiri S, Brouland JP, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Brennan C,

Tabar V, et al: Interrogation of the microenvironmental landscape

in brain tumors reveals disease-specific alterations of immune

cells. Cell. 181:1643–1660. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Friebel E, Kapolou K, Unger S, Núñez NG,

Utz S, Rushing EJ, Regli L, Weller M, Greter M, Tugues S, et al:

Single-cell mapping of human brain cancer reveals tumor-specific

instruction of tissue-invading leukocytes. Cell. 181:1626–1642.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gabrusiewicz K, Rodriguez B, Wei J,

Hashimoto Y, Healy LM, Maiti SN, Thomas G, Zhou S, Wang Q, Elakkad

A, et al: Glioblastoma-infiltrated innate immune cells resemble M0

macrophage phenotype. JCI Insight. 1:e858412016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Selenica MLB, Alvarez JA, Nash KR, Lee DC,

Cao C, Lin X, Reid P, Mouton PR, Morgan D and Gordon M: Diverse

activation of microglia by chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

overexpression in brain. J Neuroinflammation. 10:8562013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Stables MJ, Shah S, Camon EB, Lovering RC,

Newson J, Bystrom J, Farrow S and Gilroy DW: Transcriptomic

analyses of murine resolution-phase macrophages. Blood.

118:e192–e208. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Szulzewsky F, Pelz A, Feng X, Synowitz M,

Markovic D, Langmann T, Holtman IR, Wang X, Eggen BJ, Boddeke HW,

et al: Glioma-associated microglia/macrophages display an

expression profile different from M1 and M2 polarization and highly

express Gpnmb and Spp1. PLoS One. 10:e01166442015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Zeiner PS, Preusse C, Blank AE, Zachskorn

C, Baumgarten P, Caspary L, Braczynski AK, Weissenberger J, Bratzke

H, Reiß S, et al: MIF receptor CD74 is restricted to

microglia/macrophages, associated with a M1-polarized immune milieu

and prolonged patient survival in gliomas. Brain Pathol.

25:491–504. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Keane L, Cheray M, Blomgren K and Joseph

B: Multifaceted microglia-key players in primary brain tumour

heterogeneity. Nat Rev Neurol. 17:243–259. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Gieryng A, Pszczolkowska D, Walentynowicz

KA, Rajan WD and Kaminska B: Immune microenvironment of gliomas.

Lab Invest. 97:498–518. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kennedy BC, Showers CR, Anderson DE,

Anderson L, Canoll P, Bruce JN and Anderson RCE: Tumor-associated

macrophages in glioma: Friend or foe? J Oncol. 2013:4869122013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zeiner PS, Preusse C, Golebiewska A, Zinke

J, Iriondo A, Muller A, Kaoma T, Filipski K, Müller-Eschner M,

Bernatz S, et al: Distribution and prognostic impact of

microglia/macrophage subpopulations in gliomas. Brain Pathol.

29:513–529. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kaffes I, Szulzewsky F, Chen Z, Herting

CJ, Gabanic B, Vega JE, Shelton J, Switchenko JM, Ross JL, McSwain

LF, et al: Human mesenchymal glioblastomas are characterized by an

increased immune cell presence compared to proneural and classical

tumors. Oncoimmunology. 8:e16553602019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Klemm F, Möckl A, Salamero-Boix A,

Alekseeva T, Schäffer A, Schulz M, Niesel K, Maas RR, Groth M, Elie

BT, et al: Compensatory CSF2-driven macrophage activation promotes

adaptive resistance to CSF1R inhibition in breast-to-brain

metastasis. Nat Cancer. 2:1086–1101. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Niesel K, Schulz M, Anthes J, Alekseeva T,

Macas J, Salamero-Boix A, Möckl A, Oberwahrenbrock T, Lolies M,

Stein S, et al: The immune suppressive microenvironment affects

efficacy of radio-immunotherapy in brain metastasis. EMBO Mol Med.

13:e134122021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, .

Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma

genes and core pathways. Nature. 455:1061–1068. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ronellenfitsch MW, Brucker DP, Burger MC,

Wolking S, Tritschler F, Rieger J, Wick W, Weller M and Steinbach

JP: Antagonism of the mammalian target of rapamycin selectively

mediates metabolic effects of epidermal growth factor receptor

inhibition and protects human malignant glioma cells from

hypoxia-induced cell death. Brain. 132:1509–1522. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Thiepold AL, Lorenz NI, Foltyn M, Engel

AL, Divé I, Urban H, Heller S, Bruns I, Hofmann U, Dröse S, et al:

Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 activation sensitizes human

glioma cells to hypoxia-induced cell death. Brain. 140:2623–2638.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Liu GY and Sabatini DM: mTOR at the nexus

of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

21:183–203. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

García-Martínez JM and Alessi DR: mTOR

complex 2 (mTORC2) controls hydrophobic motif phosphorylation and

activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase 1

(SGK1). Biochem J. 416:375–385. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Heinzen D, Divé I, Lorenz NI, Luger AL,

Steinbach JP and Ronellenfitsch MW: Second generation mTOR

inhibitors as a double-edged sword in malignant glioma treatment.

Int J Mol Sci. 20:44742019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Ronellenfitsch MW, Zeiner PS, Mittelbronn

M, Urban H, Pietsch T, Reuter D, Senft C, Steinbach JP, Westphal M

and Harter PN: Akt and mTORC1 signaling as predictive biomarkers

for the EGFR antibody nimotuzumab in glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol

Commun. 6:812018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chinnaiyan P, Won M, Wen PY, Rojiani AM,

Werner-Wasik M, Shih HA, Ashby LS, Yu HH, Stieber VW, Malone SC, et

al: A randomized phase II study of everolimus in combination with

chemoradiation in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: Results of NRG

oncology RTOG 0913. Neuro Oncol. 20:666–673. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Wick W, Dettmer S, Berberich A, Kessler T,

Karapanagiotou-Schenkel I, Wick A, Winkler F, Pfaff E, Brors B,

Debus J, et al: N2M2 (NOA-20) phase I/II trial of molecularly

matched targeted therapies plus radiotherapy in patients with newly

diagnosed non-MGMT hypermethylated glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol.

21:95–105. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Alexander BM, Ba S, Berger MS, Berry DA,

Cavenee WK, Chang SM, Cloughesy TF, Jiang T, Khasraw M, Li W, et

al: Adaptive global innovative learning environment for

glioblastoma: GBM AGILE. Clin Cancer Res. 24:737–743. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Divé I, Klann K, Michaelis JB, Heinzen D,

Steinbach JP, Münch C and Ronellenfitsch MW: Inhibition of mTOR

signaling protects human glioma cells from hypoxia-induced cell

death in an autophagy-independent manner. Cell Death Discov.

8:4092022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sauer B, Lorenz NI, Divé I, Klann K, Luger

AL, Urban H, Schröder JH, Steinbach JP, Münch C and Ronellenfitsch

MW: Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition protects glioma cells

from temozolomide-induced cell death. Cell Death Discov. 10:82024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wick W, Gorlia T, Bady P, Platten M, van

den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Steuve J, Brandes AA, Hamou MF, Wick A,

et al: Phase II study of radiotherapy and temsirolimus versus

radiochemotherapy with temozolomide in patients with newly

diagnosed glioblastoma without MGMT promoter hypermethylation

(EORTC 26082). Clin Cancer Res. 22:4797–4806. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Harter PN, Jennewein L, Baumgarten P,

Ilina E, Burger MC, Thiepold AL, Tichy J, Zörnig M, Senft C,

Steinbach JP, et al: Immunohistochemical assessment of

phosphorylated mTORC1-pathway proteins in human brain tumors. PLoS

One. 10:e01271232015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Weichhart T, Hengstschläger M and Linke M:

Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat Rev Immunol.

15:599–614. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Weichhart T, Costantino G, Poglitsch M,

Rosner M, Zeyda M, Stuhlmeier KM, Kolbe T, Stulnig TM, Hörl WH,

Hengstschläger M, et al: The TSC-mTOR signaling pathway regulates

the innate inflammatory response. Immunity. 29:565–577. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Soave DF, Miguel MP, Tomé FD, de Menezes

LB, Nagib PRA and Celes MRN: The fate of the tumor in the hands of

microenvironment: Role of TAMs and mTOR pathway. Mediators Inflamm.

2016:89105202016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Li D, Wang C, Yao Y, Chen L, Liu G, Zhang

R, Liu Q, Shi FD and Hao J: mTORC1 pathway disruption ameliorates

brain inflammation following stroke via a shift in microglia

phenotype from M1 type to M2 type. FASEB J. 30:3388–3399. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Xie L, Sun F, Wang J, Mao X, Xie L, Yang

SH, Su DM, Simpkins JW, Greenberg DA and Jin K: mTOR signaling

inhibition modulates macrophage/microglia-mediated

neuroinflammation and secondary injury via regulatory T cells after

focal ischemia. J Immunol. 192:6009–6019. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Keane L, Antignano I, Riechers SP,

Zollinger R, Dumas AA, Offermann N, Bernis ME, Russ J, Graelmann F,

McCormick PN, et al: mTOR-dependent translation amplifies microglia

priming in aging mice. J Clin Invest. 131:e1327272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Hu Y, Mai W, Chen L, Cao K, Zhang B, Zhang

Z, Liu Y, Lou H, Duan S and Gao Z: mTOR-mediated metabolic

reprogramming shapes distinct microglia functions in response to

lipopolysaccharide and ATP. Glia. 68:1031–1045. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lisi L, Laudati E, Navarra P and dello

Russo C: The mTOR kinase inhibitors polarize glioma-activated

microglia to express a M1 phenotype. J Neuroinflammation.

11:1252014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lisi L, Ciotti GMP, Chiavari M,

Pizzoferrato M, Mangiola A, Kalinin S, Feinstein DL and Navarra P:

Phospho-mTOR expression in human glioblastoma microglia-macrophage

cells. Neurochem Int. 129:1044852019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Dumas AA, Pomella N, Rosser G, Guglielmi

L, Vinel C, Millner TO, Rees J, Aley N, Sheer D, Wei J, et al:

Microglia promote glioblastoma via mTOR-mediated immunosuppression

of the tumour microenvironment. EMBO J. 39:e1037902020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Garcia-Mesa Y, Jay TR, Checkley MA, Luttge

B, Dobrowolski C, Valadkhan S, Landreth GE, Karn J and

Alvarez-Carbonell D: Immortalization of primary microglia: A new

platform to study HIV regulation in the central nervous system. J

Neurovirol. 23:47–66. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Janabi N, Peudenier S, Héron B, Ng KH and

Tardieu M: Establishment of human microglial cell lines after

transfection of primary cultures of embryonic microglial cells with

the SV40 large T antigen. Neurosci Lett. 195:105–108. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Dello Russo C, Cappoli N, Coletta I,

Mezzogori D, Paciello F, Pozzoli G, Navarra P and Battaglia A: The

human microglial HMC3 cell line: Where do we stand? A systematic

literature review. J Neuroinflammation. 15:2592018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Studer A, de Tribolet N, Diserens AC,

Gaide AC, Matthieu JM, Carrel S and Stavrou D: Characterization of

four human malignant glioma cell lines. Acta Neuropathol.

66:208–217. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Wischhusen J, Naumann U, Ohgaki H,

Rastinejad F and Weller M: CP-31398, a novel p53-stabilizing agent,

induces p53-dependent and p53-independent glioma cell death.

Oncogene. 22:8233–8245. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lorenz NI, Sittig ACM, Urban H, Luger AL,

Engel AL, Münch C, Steinbach JP and Ronellenfitsch MW: Activating

transcription factor 4 mediates adaptation of human glioblastoma

cells to hypoxia and temozolomide. Sci Rep. 11:141612021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Roth W, Fontana A, Trepel M, Reed JC,

Dichgans J and Weller M: Immunochemotherapy of malignant glioma:

Synergistic activity of CD95 ligand and chemotherapeutics. Cancer

Immunol Immunother. 44:55–63. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Steinbach JP, Wolburg H, Klumpp A, Probst

H and Weller M: Hypoxia-induced cell death in human malignant

glioma cells: Energy deprivation promotes decoupling of

mitochondrial cytochrome c release from caspase processing and

necrotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 10:823–832. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Schulz M, Michels B, Niesel K, Stein S,

Farin H, Rödel F and Sevenich L: Cellular and molecular changes of

brain metastases-associated myeloid cells during disease

progression and therapeutic response. iScience. 23:1011782020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Michels BE, Mosa MH, Grebbin BM, Yepes D,

Darvishi T, Hausmann J, Urlaub H, Zeuzem S, Kvasnicka HM, Oellerich

T and Farin HF: Human colon organoids reveal distinct physiologic

and oncogenic Wnt responses. J Exp Med. 216:704–720. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H,

Kelley R and Salzberg SL: TopHat2: Accurate alignment of

transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene

fusions. Genome Biol. 14:R362013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Love MI, Huber W and Anders S: Moderated

estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with

DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:5502014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Westphal M, Heese O, Steinbach JP, Schnell

O, Schackert G, Mehdorn M, Schulz D, Simon M, Schlegel U, Senft C,

et al: A randomised, open label phase III trial with nimotuzumab,

an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody in the

treatment of newly diagnosed adult glioblastoma. Eur J Cancer.

51:522–532. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

He S, Kato K, Jiang J, Wahl DR, Mineishi

S, Fisher EM, Murasko DM, Glick GD and Zhang Y: Characterization of

the metabolic phenotype of rapamycin-treated CD8+ T cells with

augmented ability to generate long-lasting memory cells. PLoS One.

6:e201072011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ

and Hill AM: M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J

Immunol. 164:6166–6173. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Platten M, Bunse L, Wick A, Bunse T, Le

Cornet L, Harting I, Sahm F, Sanghvi K, Tan CL, Poschke I, et al: A

vaccine targeting mutant IDH1 in newly diagnosed glioma. Nature.

592:463–468. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Burger MC, Forster MT, Romanski A,

Straßheimer F, Macas J, Zeiner PS, Steidl E, Herkt S, Weber KJ,

Schupp J, et al: Intracranial injection of NK cells engineered with

a HER2-targeted chimeric antigen receptor in patients with

recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 25:2058–2071. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Omuro A, Brandes AA, Carpentier AF, Idbaih

A, Reardon DA, Cloughesy T, Sumrall A, Baehring J, van den Bent M,

Bähr O, et al: Radiotherapy combined with nivolumab or temozolomide

for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with unmethylated MGMT promoter:

An international randomized phase III trial. Neuro Oncol.

25:123–134. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Lim M, Weller M, Idbaih A, Steinbach J,

Finocchiaro G, Raval RR, Ansstas G, Baehring J, Taylor JW, Honnorat

J, et al: Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide

plus nivolumab or placebo for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with

methylated MGMT promoter. Neuro Oncol. 24:1935–1949. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Gunasegaran B, Krishnamurthy S, Chow SS,

Villanueva MD, Guller A, Ahn SB and Heng B: Comparative analysis of

HMC3 and C20 microglial cell lines reveals differential myeloid

characteristics and responses to immune stimuli. Immunology.

175:84–102. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Liu Q, Xu C, Kirubakaran S, Zhang X, Hur

W, Liu Y, Kwiatkowski NP, Wang J, Westover KD, Gao P, et al:

Characterization of Torin2, an ATP-competitive inhibitor of mTOR,

ATM, and ATR. Cancer Res. 73:2574–2586. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wick W, Lanz LM, Wick A, Harting I,

Dettmer S, Suwala AK, Ketter R, Tabatabai G, Seliger-Behme C, Glas

M, et al: N2M2/NOA-20: Phase I/IIa umbrella trial of molecularly

matched targeted therapies plus radiotherapy in patients with newly

diagnosed glioblastoma without MGMT promoter hypermethylation. J

Clin Oncol. 42:20002024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Strecker MI, Wlotzka K, Strassheimer F,

Roller B, Ludmirski G, König S, Röder J, Opitz C, Alekseeva T, Reul

J, et al: AAV-mediated gene transfer of a checkpoint inhibitor in

combination with HER2-targeted CAR-NK cells as experimental therapy

for glioblastoma. Oncoimmunology. 11:21275082022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|